The Gurkhas Performance and Morale on Operation Longcloth

From the book, Across the Threshold of Battle, written by Harold James, a young Gurkha Subaltern who served with No. 3 Column on Operation Longcloth:

When the Chindits were given the order to withdraw in March 1943, Wingate had stressed the importance of bringing back men who were valuable because of the experience they had gained in Long Range Penetration operations. But a very small proportion of these men continued in that type of operation.

The battered 3/2nd Gurkha Rifles had to rebuild. Its morale was understandably very low and the British and Gurkha Officers faced a difficult rehabilitation task. The battalion had lost some 400 men, including 74 POWs. But many of the Gurkhas had displayed great courage and physical endurance in an action which was quite foreign to a battalion under active service conditions, and there was still an abundance of excellent officer material to build on, with at least three eventually becoming Gurkha Majors.

There were also some splendid British Officers who rallied round. When Brigadier Reggie Hutton heard that the 3/2nd Gurkhas needed a new CO, he immediately volunteered to drop from his rank as Brigadier to Lieutenant-Colonel, and with him came Philip Panton as second-in-command. From the moment of their arrival, the battalions fortunes never looked back. Both men were of the Regiment and the men took to them at once. The old kaida (customs or traditions) was restored and the Gurkhas were once again commanded completely by British Officers of the Regiment. Morale soared, training became practical and realistic again, and every man knew that when we went back to war with the Japanese again, we would kick them from here to eternity. From the ashes of the Chindit expedition a superb front line battalion arose, the ultimate Jap-killing machine in 25th Indian Division, fighting with great distinction in the Arakan, with one of the Gurkhas winning the Victoria Cross.

Much has been written, both at the time and since about the performance of the Gurkhas on Operation Longcloth and their struggles to grasp and come to terms with Wingate's ideas on Long Range Penetration and jungle warfare. After returning to India in April 1943, Mike Calvert, a commander of Gurkha troops during the first Chindit expedition, gave an appraisal of the their performance in the form of a confidential four page report. It will come as no surprise that Calvert's debrief pulls no punches when it comes to the Gurkhas failings in the jungles of Burma that year, but I do believe it was written as an objective, honest and sympathetic assessment by the Chindit commander.

When the Chindits were given the order to withdraw in March 1943, Wingate had stressed the importance of bringing back men who were valuable because of the experience they had gained in Long Range Penetration operations. But a very small proportion of these men continued in that type of operation.

The battered 3/2nd Gurkha Rifles had to rebuild. Its morale was understandably very low and the British and Gurkha Officers faced a difficult rehabilitation task. The battalion had lost some 400 men, including 74 POWs. But many of the Gurkhas had displayed great courage and physical endurance in an action which was quite foreign to a battalion under active service conditions, and there was still an abundance of excellent officer material to build on, with at least three eventually becoming Gurkha Majors.

There were also some splendid British Officers who rallied round. When Brigadier Reggie Hutton heard that the 3/2nd Gurkhas needed a new CO, he immediately volunteered to drop from his rank as Brigadier to Lieutenant-Colonel, and with him came Philip Panton as second-in-command. From the moment of their arrival, the battalions fortunes never looked back. Both men were of the Regiment and the men took to them at once. The old kaida (customs or traditions) was restored and the Gurkhas were once again commanded completely by British Officers of the Regiment. Morale soared, training became practical and realistic again, and every man knew that when we went back to war with the Japanese again, we would kick them from here to eternity. From the ashes of the Chindit expedition a superb front line battalion arose, the ultimate Jap-killing machine in 25th Indian Division, fighting with great distinction in the Arakan, with one of the Gurkhas winning the Victoria Cross.

Much has been written, both at the time and since about the performance of the Gurkhas on Operation Longcloth and their struggles to grasp and come to terms with Wingate's ideas on Long Range Penetration and jungle warfare. After returning to India in April 1943, Mike Calvert, a commander of Gurkha troops during the first Chindit expedition, gave an appraisal of the their performance in the form of a confidential four page report. It will come as no surprise that Calvert's debrief pulls no punches when it comes to the Gurkhas failings in the jungles of Burma that year, but I do believe it was written as an objective, honest and sympathetic assessment by the Chindit commander.

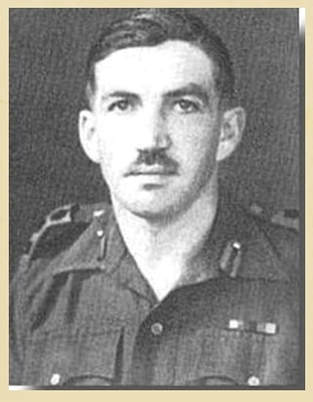

Mike Calvert, Chindit Commander.

Mike Calvert, Chindit Commander.

Morale of Gurkha Ranks on Operation Longcloth (Confidential).

From the foregoing war diary (3 Column) it will be seen that all ranks, British, Gurkha and Burma Rifles, on the whole fought well under difficult conditions, carried out their continuous duties in the column with zest and remained a powerful striking force which was feared by the enemy. However, it would be wrong to state that all was well throughout the Brigade in the way of behaviour in action and morale.

Statements have already been made about the breakdown in morale amongst Gurkhas in other Columns. Starting from the beginning the following is I hope, a fair statement glossing over no details in regards the state of morale during the period in which I had the honour to command the officers and men of No. 3 Column.

I was ordered to take up the appointment of Officer Commanding No. 3 column on the 1st December 1942. Realising the difficulty and appreciating the honour of being asked to command a column consisting mainly of Gurkha troops, I called all officers together and explained that I considered myself in command of a mixed formation, and would unless it was necessary in the field, only issue orders through the commanders of the various units. All matters of promotion, discipline etc. would be dealt with by the local commander, but once in Burma, I would be the supreme arbiter in all points of discipline and would be held responsible for my actions on my return.

Throughout the period of training and in Burma, I have been most loyally supported by my officers an all occasions. I made a similar speech to the Burma Rifles and 142 Commando, stating that having served with Gurkhas and Burmese in the last campaign, I knew their worth.

I have reason to believe that certain officers of the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles disapprove strongly with the decision to place non-Gurkha officers in charge of Gurkha columns. They also were ill-advised enough to express these concerns within the hearing of other officers and this may have sowed the seeds of distrust amongst the men. Thankfully, this did not affect No. 3 Column and I found I was loyally supported by my officers at all times. Only on a few occasions did I have to intervene, when no action was taken in regards such things as: water discipline, smoking on the march and the purchase of food from local villagers.

On meeting Colonel Alexander at the Shweli River, I had a long talk with him about it and he said that No. 1 Column were beginning to have the same difficulty. I told him frankly that I did not in any way consider that there was a serious decline in discipline, but that I knew from experience in this type of work, that once things begin to deteriorate it becomes impossible to keep such a force in the field and I was determined to stop this rot in its tracks. He agreed and spoke to Captain Silcock who was also in complete agreement and subsequently gave over all discipline requirements to Subedar Kumba Sing Gurung. From then on there was a great improvement on all the matters mentioned.

Captain Silcock, a month or two before going into action stated to me that the morale and discipline of his battalion had declined since they had come over from Fort Sandeman. He blamed the influx of badly trained muleteers from other Gurkha units who committed all sorts of crimes and had not welded to the 3/2 way of things. He also bemoaned the mixing up of various Gurkha units when the Brigade was brought up to strength just before entering Burma. He believed the drafts arriving from elsewhere were of a low standard. Captain Silcock also told me that the 3/2 believed that more facilities had been given to the British troops during training, especially in the way of leave periods and recreation. They also felt they had been used much more for labour and they referred to themselves as the Coolie Battalion.

I took his views seriously and we tried together to re-build a firm foundation of morale in the column. Later on, during the march down to Imphal, we had a high proportion of stragglers, which surprised us as it went against all previous experiences. This worried Wingate considerably, especially when Lt-Colonel Wheeler of the Burma Rifles stated that in his view these were not the Gurkhas he remembered from last year’s fighting during the retreat. Wingate feared for the operation ahead, but I convinced him that everything would be alright when the men got into action.

In the campaign all went well at first. In our first action against the Japanese at Nanakan, Subedar Kumba Singh Gurung with his section did outstanding work. When I took a platoon into action myself, the men behaved very well, even though it was the first time they had seen action against an enemy. Our training idiom, of not exposing your position to the enemy by wild firing, did on occasion prevent the Gurkhas from engaging the enemy quickly enough and encouraged them in keeping their heads down for too long. In the end I made an order telling all ranks to always engage, shoot and kill the enemy whenever they were seen. In my view the Gurkhas did well under fire, perhaps even better than the British soldiers under my command.

After this first victory morale could not have been higher. Then the period came when we got into the wake of Nos. 1 and 5 Columns and were chased by various Japanese formations which hung thereafter on our tail. This became very trying and the men had little sleep and continuous hard marching.

In the action against the Japanese on the Irrawaddy island, we were all tired from the exertions the day before. I had made the mistake of not getting my second line out of range and it was whilst moving to do this that we were attacked. Later we had to leave much of our equipment and stores behind and this made the Gurkhas feel we had suffered a heavy defeat. Whereas in reality, we had inflicted many more casualties upon the enemy and had crossed the river almost without loss to ourselves. I did have two reduce two Havildars to the ranks afterwards; one for leaving his mortar behind and the other for taking his section out from the action without orders to do so.

Once again this reaction was a defect from the training program, where we had consistently told the men to avoid contact with the enemy and to disperse at the first alarm after shots were fired. This emphasis on safety and retreat proved a hinderance in the field and I changed things quickly, only giving the order for dispersal on my command through the officers of each unit. At Pago (23rd March) the majority of the men fought well, but one Gurkha officer did abandon his British officer and returned with two Gurkha sections without orders. When our bivouac was attacked, some of muleteers and followers panicked and ran straight to where we had previously buried some rations. We found them there two days later, when we returned to collect the rations. At the next engagement near Nyaungbintha, practically the whole column performed poorly and did not shine.

Generally, I felt that the Gurkha Officers were too cautious in what was after all a bold operation and that this cautious nature often spelt disaster. As the old rugby saying goes: if you tackle hard then you don’t get hurt.

Summary

1. The Gurkhas went into the campaign without any of the exhilaration of the British troops. This I believe was down to their over-long training period (6 months) and lack of leave periods to recharge their batteries. Only one officer in No. 3 Column could speak Gurkhali and this proved a hinderance in Burma.

2. The Gurkha soldier is excellent when he understands his objective, but is not as adaptable as his British counterpart. The vast majority of regimental centres had trained Gurkhas for fighting in the Western Desert and jungle fighting and the unknown nature of Long Range Penetration had the men confused.

3. The 3/2 had to expand rapidly during training, with some NCOs receiving quick promotions, chosen mostly by length of service rather than ability. An excellent case in point was that of Support Havildar Dhurbu Sing Thapa. His commander had strongly recommended his promotion to Jemadar, but this was turned down in favour of a more senior man, who was in the end of little use. In Burma these promoted men were conspicuous by the absence during engagements with the enemy and it required a young British Officer (probably Harold James) to rescue and lead the platoon.

4. The mixing up of Gurkhas from other regiments had a bad effect on morale. The Gurkha soldiers loyalty is very much to his own Regiment and to see his unit split up and others join reduced the espirit de corps within the 3/2.

5. There is no doubt that if I could have spoken directly to my men in Gurkhali then morale would have been twice as good. My only Gurkhali speaker (George Silcock) did well giving out my orders, but could not express to the men, abstract ideas, conceptions and ideals which form a strong part of this type of warfare. On a similar note, I think some of the religious scrupples and worries suffered by the men in Burma may well have been allayed if Gurkhali speakers were more prevalent.

6. The Gurkha Brigade was given too many dates by which to be ready. The result was that although it had completed its collective operational training, some basic and elementary aspects were overlooked. This was made even worse by the last minute influx of new recruits from other regiments.

7. With hindsight, it was madness to bring followers into battle. I take the blame for having them in my column, thinking that it was an Indian Army custom and that they would prove useful in established or permanent camps, which they did not.

8. Of my Gurkha British Officers, I judge them by very high standards and although there were examples of definite courage, some were lacking in both knowledge and maturity.

9. The muleteers came from several different Regimental Centres. They became efficient in animal management in the end, but discipline remained poor in spite of all efforts. When, after losing the majority of our mules they were formed into fighting platoons, barely half proved to be good fighting soldiers.

10. Considering the new and unusual aspects of the campaign and the young age of the Gurkha soldiers, their performance overall was good. It must be remembered that the British troops in other columns, although having a much higher proportion of officers to men started to crack before we did. In this type of warfare, as explained in lectures beforehand, battle casualties are normally light, but casualties due to loss of nerve or separation from they unit are heavy. And so it proved to be.

When the weak are weeded out and promotions of the good performers made, I would be perfectly happy in taking these men back into action and they would do well. I strongly recommend that the 3/2 is sent back to it’s Regimental Centre at Dehra Dun, where these changes can be made and the men can undergo the various religious ceremonies necessary to cleanse and reaffirm them after this campaign.

Major J.M. Calvert (Imphal 10th April 1943).

From the foregoing war diary (3 Column) it will be seen that all ranks, British, Gurkha and Burma Rifles, on the whole fought well under difficult conditions, carried out their continuous duties in the column with zest and remained a powerful striking force which was feared by the enemy. However, it would be wrong to state that all was well throughout the Brigade in the way of behaviour in action and morale.

Statements have already been made about the breakdown in morale amongst Gurkhas in other Columns. Starting from the beginning the following is I hope, a fair statement glossing over no details in regards the state of morale during the period in which I had the honour to command the officers and men of No. 3 Column.

I was ordered to take up the appointment of Officer Commanding No. 3 column on the 1st December 1942. Realising the difficulty and appreciating the honour of being asked to command a column consisting mainly of Gurkha troops, I called all officers together and explained that I considered myself in command of a mixed formation, and would unless it was necessary in the field, only issue orders through the commanders of the various units. All matters of promotion, discipline etc. would be dealt with by the local commander, but once in Burma, I would be the supreme arbiter in all points of discipline and would be held responsible for my actions on my return.

Throughout the period of training and in Burma, I have been most loyally supported by my officers an all occasions. I made a similar speech to the Burma Rifles and 142 Commando, stating that having served with Gurkhas and Burmese in the last campaign, I knew their worth.

I have reason to believe that certain officers of the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles disapprove strongly with the decision to place non-Gurkha officers in charge of Gurkha columns. They also were ill-advised enough to express these concerns within the hearing of other officers and this may have sowed the seeds of distrust amongst the men. Thankfully, this did not affect No. 3 Column and I found I was loyally supported by my officers at all times. Only on a few occasions did I have to intervene, when no action was taken in regards such things as: water discipline, smoking on the march and the purchase of food from local villagers.

On meeting Colonel Alexander at the Shweli River, I had a long talk with him about it and he said that No. 1 Column were beginning to have the same difficulty. I told him frankly that I did not in any way consider that there was a serious decline in discipline, but that I knew from experience in this type of work, that once things begin to deteriorate it becomes impossible to keep such a force in the field and I was determined to stop this rot in its tracks. He agreed and spoke to Captain Silcock who was also in complete agreement and subsequently gave over all discipline requirements to Subedar Kumba Sing Gurung. From then on there was a great improvement on all the matters mentioned.

Captain Silcock, a month or two before going into action stated to me that the morale and discipline of his battalion had declined since they had come over from Fort Sandeman. He blamed the influx of badly trained muleteers from other Gurkha units who committed all sorts of crimes and had not welded to the 3/2 way of things. He also bemoaned the mixing up of various Gurkha units when the Brigade was brought up to strength just before entering Burma. He believed the drafts arriving from elsewhere were of a low standard. Captain Silcock also told me that the 3/2 believed that more facilities had been given to the British troops during training, especially in the way of leave periods and recreation. They also felt they had been used much more for labour and they referred to themselves as the Coolie Battalion.

I took his views seriously and we tried together to re-build a firm foundation of morale in the column. Later on, during the march down to Imphal, we had a high proportion of stragglers, which surprised us as it went against all previous experiences. This worried Wingate considerably, especially when Lt-Colonel Wheeler of the Burma Rifles stated that in his view these were not the Gurkhas he remembered from last year’s fighting during the retreat. Wingate feared for the operation ahead, but I convinced him that everything would be alright when the men got into action.

In the campaign all went well at first. In our first action against the Japanese at Nanakan, Subedar Kumba Singh Gurung with his section did outstanding work. When I took a platoon into action myself, the men behaved very well, even though it was the first time they had seen action against an enemy. Our training idiom, of not exposing your position to the enemy by wild firing, did on occasion prevent the Gurkhas from engaging the enemy quickly enough and encouraged them in keeping their heads down for too long. In the end I made an order telling all ranks to always engage, shoot and kill the enemy whenever they were seen. In my view the Gurkhas did well under fire, perhaps even better than the British soldiers under my command.

After this first victory morale could not have been higher. Then the period came when we got into the wake of Nos. 1 and 5 Columns and were chased by various Japanese formations which hung thereafter on our tail. This became very trying and the men had little sleep and continuous hard marching.

In the action against the Japanese on the Irrawaddy island, we were all tired from the exertions the day before. I had made the mistake of not getting my second line out of range and it was whilst moving to do this that we were attacked. Later we had to leave much of our equipment and stores behind and this made the Gurkhas feel we had suffered a heavy defeat. Whereas in reality, we had inflicted many more casualties upon the enemy and had crossed the river almost without loss to ourselves. I did have two reduce two Havildars to the ranks afterwards; one for leaving his mortar behind and the other for taking his section out from the action without orders to do so.

Once again this reaction was a defect from the training program, where we had consistently told the men to avoid contact with the enemy and to disperse at the first alarm after shots were fired. This emphasis on safety and retreat proved a hinderance in the field and I changed things quickly, only giving the order for dispersal on my command through the officers of each unit. At Pago (23rd March) the majority of the men fought well, but one Gurkha officer did abandon his British officer and returned with two Gurkha sections without orders. When our bivouac was attacked, some of muleteers and followers panicked and ran straight to where we had previously buried some rations. We found them there two days later, when we returned to collect the rations. At the next engagement near Nyaungbintha, practically the whole column performed poorly and did not shine.

Generally, I felt that the Gurkha Officers were too cautious in what was after all a bold operation and that this cautious nature often spelt disaster. As the old rugby saying goes: if you tackle hard then you don’t get hurt.

Summary

1. The Gurkhas went into the campaign without any of the exhilaration of the British troops. This I believe was down to their over-long training period (6 months) and lack of leave periods to recharge their batteries. Only one officer in No. 3 Column could speak Gurkhali and this proved a hinderance in Burma.

2. The Gurkha soldier is excellent when he understands his objective, but is not as adaptable as his British counterpart. The vast majority of regimental centres had trained Gurkhas for fighting in the Western Desert and jungle fighting and the unknown nature of Long Range Penetration had the men confused.

3. The 3/2 had to expand rapidly during training, with some NCOs receiving quick promotions, chosen mostly by length of service rather than ability. An excellent case in point was that of Support Havildar Dhurbu Sing Thapa. His commander had strongly recommended his promotion to Jemadar, but this was turned down in favour of a more senior man, who was in the end of little use. In Burma these promoted men were conspicuous by the absence during engagements with the enemy and it required a young British Officer (probably Harold James) to rescue and lead the platoon.

4. The mixing up of Gurkhas from other regiments had a bad effect on morale. The Gurkha soldiers loyalty is very much to his own Regiment and to see his unit split up and others join reduced the espirit de corps within the 3/2.

5. There is no doubt that if I could have spoken directly to my men in Gurkhali then morale would have been twice as good. My only Gurkhali speaker (George Silcock) did well giving out my orders, but could not express to the men, abstract ideas, conceptions and ideals which form a strong part of this type of warfare. On a similar note, I think some of the religious scrupples and worries suffered by the men in Burma may well have been allayed if Gurkhali speakers were more prevalent.

6. The Gurkha Brigade was given too many dates by which to be ready. The result was that although it had completed its collective operational training, some basic and elementary aspects were overlooked. This was made even worse by the last minute influx of new recruits from other regiments.

7. With hindsight, it was madness to bring followers into battle. I take the blame for having them in my column, thinking that it was an Indian Army custom and that they would prove useful in established or permanent camps, which they did not.

8. Of my Gurkha British Officers, I judge them by very high standards and although there were examples of definite courage, some were lacking in both knowledge and maturity.

9. The muleteers came from several different Regimental Centres. They became efficient in animal management in the end, but discipline remained poor in spite of all efforts. When, after losing the majority of our mules they were formed into fighting platoons, barely half proved to be good fighting soldiers.

10. Considering the new and unusual aspects of the campaign and the young age of the Gurkha soldiers, their performance overall was good. It must be remembered that the British troops in other columns, although having a much higher proportion of officers to men started to crack before we did. In this type of warfare, as explained in lectures beforehand, battle casualties are normally light, but casualties due to loss of nerve or separation from they unit are heavy. And so it proved to be.

When the weak are weeded out and promotions of the good performers made, I would be perfectly happy in taking these men back into action and they would do well. I strongly recommend that the 3/2 is sent back to it’s Regimental Centre at Dehra Dun, where these changes can be made and the men can undergo the various religious ceremonies necessary to cleanse and reaffirm them after this campaign.

Major J.M. Calvert (Imphal 10th April 1943).

Copyright © Steve Fogden, January 2019.