Whistling Pte. Pierce

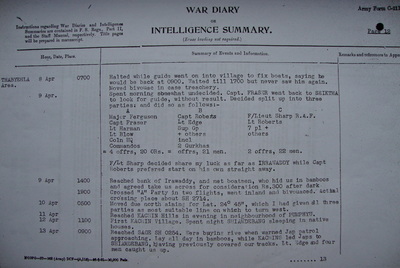

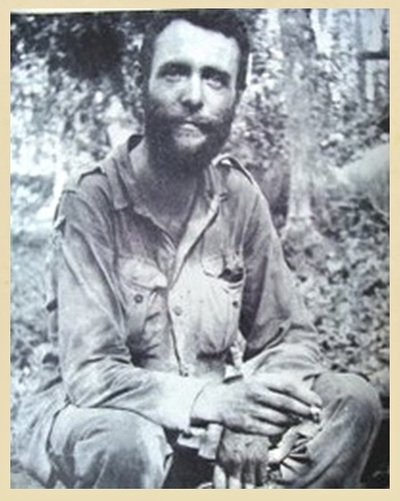

One man from 5 Column, a Pte. Pierce, had the good fortune of finding his way back to his unit, not once, but twice during Operation Longcloth after being lost overnight on both occasions. His exploits are mentioned in Bernard Fergusson's book about 5 Column's adventures in 1943, Beyond the Chindwin. We know that Pte. Pierce returned safely to India that year, but the lack of any other details about him, his christian name or Army number for instance, means that we cannot fully identify this man or his pathway to becoming a Chindit.

At the time of 5 Column's dispersal, Pte. Pierce was placed into the group to be led by Captain Tommy Roberts. It was at this point, around the 10th April 1943, that Pierce became lost to his comrades for the second time in just under ten days. It seems that he had left his precious water bottle behind at the last column halt and asked permission to return to the location to find it. He never managed to re-join Roberts' group again.

I will allow Bernard Fergusson to illustrate the story more fully:

We had broken down into three dispersal groups close to the Irrawaddy. Tommy Roberts had seen an old fishing boat on the back of the mere behind the fisherman's hut, and near it an old bullock-cart. He proposed to put the one on the other, and wheel it to the Irrawaddy. Denny Sharp wanted to come with me as far as the river, and share my luck there if I had any. I proposed to march boldly to the river in daylight, straight away, to see if there were any sign of boats.

Tommy hated hanging about as much as I did, and with the prospect of doing something he became positively jubilant. He got hold of his party, harangued them briskly, and then all together we marched back to the fisherman's hut. There I shook hands with Tommy, and wished him luck. He was full of confidence and very cheerful; before I had gone a hundred yards I looked back and saw him organising a party to haul the boat out of the water, and sending some more men to fetch the bullock-cart. That was the last time I ever saw him.

Once over the inky black river and with the coming of daylight the jungle looked less formidable, we found almost immediately a long and narrow patch of disused paddy, leading past the thick outer defences of the forest. Two incidents during the first fifteen minutes' marching cheered us up (and we were cheerful enough already, with the Irrawaddy behind us). First, out of the undergrowth darted Judy our messenger dog, she looked at us quizzically and vanished back into the trees before we could put a note in the little satchel which she still wore round her neck. She had by now become firmly attached to Gerry Roberts, so we knew that Denny Sharp was across complete, and on the move in the same general direction as ourselves.

NB. All Chindit columns had a messenger dog. Judy worked with 5 Column under her two original handlers, Pte. 3779341 William Henry Anders and Pte. 5116413 Harold Victor Cummings. Sadly, both these men perished as a result of their time on Operation Longcloth. William Anders was captured at the Shweli River on 1st April 1943 and died in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on the 14th March 1944. Harold Cummings was lost somewhere on the Chinese Borders in late April 1943, having dispersed with Lieutenant Musgrave-Wood of 7 Column. I am pleased to report that Judy did make it back to India as part of the dispersal group led by Flight-Lieutenant Denny Sharp.

Fergusson continues:

The other incident has often been publicised by journalists and others, but as it happened to us I claim the right to repeat it. We suddenly heard the unmistakable sound of a British soldier whistling, and out of the jungle emerged the jaunty figure of Private Pierce.

Private Pierce had been one of the two men who changed his mind about remaining on the Shweli sandbank on the 1st April, and had caught us up after we left. Now, allotted to Tommy Roberts' party, he had left his water bottle behind at the fisherman's hut, and had gone back a few hundred yards to retrieve it. Having done so, he had failed to find Tommy again; but, knowing the intention was to cross the Irrawaddy, he had walked in broad daylight to the riverbank, and then along it until he found a man with a boat.

This chap invited him to supper which, having no previous engagement, he accepted; and was then put across the river. All directions were much the same to him, so he decided to make for the fire which I had been at such pains to avoid. Here he found another fisherman, who also invited him, not only to supper, but to spend the night. This also he accepted, and left next morning at dawn with his pack and pockets full of dried fish, tobacco and chantaga; plus a cooking-pot and a neat knitted bag to carry it in. I feel there must be a moral to this story, but I cannot think what it is. But, as I said at the time, with luck like Private Pierce's no wonder he was whistling.

At the time of 5 Column's dispersal, Pte. Pierce was placed into the group to be led by Captain Tommy Roberts. It was at this point, around the 10th April 1943, that Pierce became lost to his comrades for the second time in just under ten days. It seems that he had left his precious water bottle behind at the last column halt and asked permission to return to the location to find it. He never managed to re-join Roberts' group again.

I will allow Bernard Fergusson to illustrate the story more fully:

We had broken down into three dispersal groups close to the Irrawaddy. Tommy Roberts had seen an old fishing boat on the back of the mere behind the fisherman's hut, and near it an old bullock-cart. He proposed to put the one on the other, and wheel it to the Irrawaddy. Denny Sharp wanted to come with me as far as the river, and share my luck there if I had any. I proposed to march boldly to the river in daylight, straight away, to see if there were any sign of boats.

Tommy hated hanging about as much as I did, and with the prospect of doing something he became positively jubilant. He got hold of his party, harangued them briskly, and then all together we marched back to the fisherman's hut. There I shook hands with Tommy, and wished him luck. He was full of confidence and very cheerful; before I had gone a hundred yards I looked back and saw him organising a party to haul the boat out of the water, and sending some more men to fetch the bullock-cart. That was the last time I ever saw him.

Once over the inky black river and with the coming of daylight the jungle looked less formidable, we found almost immediately a long and narrow patch of disused paddy, leading past the thick outer defences of the forest. Two incidents during the first fifteen minutes' marching cheered us up (and we were cheerful enough already, with the Irrawaddy behind us). First, out of the undergrowth darted Judy our messenger dog, she looked at us quizzically and vanished back into the trees before we could put a note in the little satchel which she still wore round her neck. She had by now become firmly attached to Gerry Roberts, so we knew that Denny Sharp was across complete, and on the move in the same general direction as ourselves.

NB. All Chindit columns had a messenger dog. Judy worked with 5 Column under her two original handlers, Pte. 3779341 William Henry Anders and Pte. 5116413 Harold Victor Cummings. Sadly, both these men perished as a result of their time on Operation Longcloth. William Anders was captured at the Shweli River on 1st April 1943 and died in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on the 14th March 1944. Harold Cummings was lost somewhere on the Chinese Borders in late April 1943, having dispersed with Lieutenant Musgrave-Wood of 7 Column. I am pleased to report that Judy did make it back to India as part of the dispersal group led by Flight-Lieutenant Denny Sharp.

Fergusson continues:

The other incident has often been publicised by journalists and others, but as it happened to us I claim the right to repeat it. We suddenly heard the unmistakable sound of a British soldier whistling, and out of the jungle emerged the jaunty figure of Private Pierce.

Private Pierce had been one of the two men who changed his mind about remaining on the Shweli sandbank on the 1st April, and had caught us up after we left. Now, allotted to Tommy Roberts' party, he had left his water bottle behind at the fisherman's hut, and had gone back a few hundred yards to retrieve it. Having done so, he had failed to find Tommy again; but, knowing the intention was to cross the Irrawaddy, he had walked in broad daylight to the riverbank, and then along it until he found a man with a boat.

This chap invited him to supper which, having no previous engagement, he accepted; and was then put across the river. All directions were much the same to him, so he decided to make for the fire which I had been at such pains to avoid. Here he found another fisherman, who also invited him, not only to supper, but to spend the night. This also he accepted, and left next morning at dawn with his pack and pockets full of dried fish, tobacco and chantaga; plus a cooking-pot and a neat knitted bag to carry it in. I feel there must be a moral to this story, but I cannot think what it is. But, as I said at the time, with luck like Private Pierce's no wonder he was whistling.

As mentioned by Bernard Fergusson, Pte. Pierce had almost given up the chance of escaping Burma around ten days earlier, when he was one of the fifty or so men who refused to cross the last section of the fast flowing and treacherous Shweli River. On the 1st April near the village of Tokkin, 5 Column had managed to reach what they thought was the far bank of the Shweli, but discovered to their horror that they were actually on a large sandbank in the middle of the river, with still some 80 yards of rapidly moving water between them and their ultimate goal.

Already exhausted and malnourished, this proved too much for some of the men and they slumped down on to the sands to rest. Fergusson and his officers urged the men to rise up and attempt the final crossing, as, by this time a Japanese patrol had closed in on the now desperate Chindits. A section of Burma Riflemen decide to attempt the crossing, but two were quickly swept away by the foaming waters, this was the final straw for the other men and they refused to carry on.

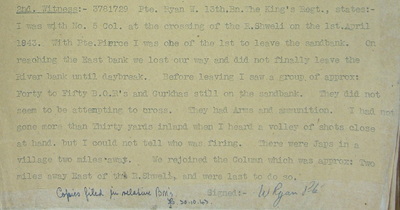

For some reason, Pte. Pierce changed his mind that day and elected, along with another soldier Pte. W. Ryan to chance their arm and cross the final section of the Shweli and continue their march out to India. Pte. Ryan gave a witness statement after the expedition was over, explaining what had happened at the Shweli and how he and Pte. Pierce had re-contacted Major Fergusson and the rest of 5 Column:

I was with No. 5 Column at the crossing of the River Shweli on the 1st April 1943. With Pte. Pierce, I was one of the last to leave the sandbank. On reaching the east bank we lost our way and did not finally leave the river bank until daybreak. Before leaving I saw a group of approximately 40 to 50 British Other Ranks and Gurkhas still on the sandbank. They did not seem to be attempting to cross. They had arms and ammunition.

I had not gone more than thirty yards inland, when I heard a volley of shots close at hand, but I could not tell who was firing. There were Japs in the village just two miles away. We re-joined the Column which was approximately two miles away and were the last men to do so.

To read more about the men lost at the Shweli River, please click on the following link: Jimmy Zorn

Pte. Pierce, Pte. Ryan and around eighty other men from 5 Column re-crossed the Chindwin River on or about the 24th April 1943. Seen below is a Gallery of images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Already exhausted and malnourished, this proved too much for some of the men and they slumped down on to the sands to rest. Fergusson and his officers urged the men to rise up and attempt the final crossing, as, by this time a Japanese patrol had closed in on the now desperate Chindits. A section of Burma Riflemen decide to attempt the crossing, but two were quickly swept away by the foaming waters, this was the final straw for the other men and they refused to carry on.

For some reason, Pte. Pierce changed his mind that day and elected, along with another soldier Pte. W. Ryan to chance their arm and cross the final section of the Shweli and continue their march out to India. Pte. Ryan gave a witness statement after the expedition was over, explaining what had happened at the Shweli and how he and Pte. Pierce had re-contacted Major Fergusson and the rest of 5 Column:

I was with No. 5 Column at the crossing of the River Shweli on the 1st April 1943. With Pte. Pierce, I was one of the last to leave the sandbank. On reaching the east bank we lost our way and did not finally leave the river bank until daybreak. Before leaving I saw a group of approximately 40 to 50 British Other Ranks and Gurkhas still on the sandbank. They did not seem to be attempting to cross. They had arms and ammunition.

I had not gone more than thirty yards inland, when I heard a volley of shots close at hand, but I could not tell who was firing. There were Japs in the village just two miles away. We re-joined the Column which was approximately two miles away and were the last men to do so.

To read more about the men lost at the Shweli River, please click on the following link: Jimmy Zorn

Pte. Pierce, Pte. Ryan and around eighty other men from 5 Column re-crossed the Chindwin River on or about the 24th April 1943. Seen below is a Gallery of images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, June 2016.