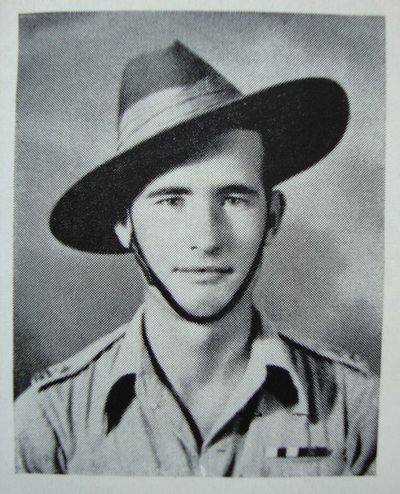

'Young Ernie' Belcher

Ernest Thomas Belcher.

Ernest Thomas Belcher.

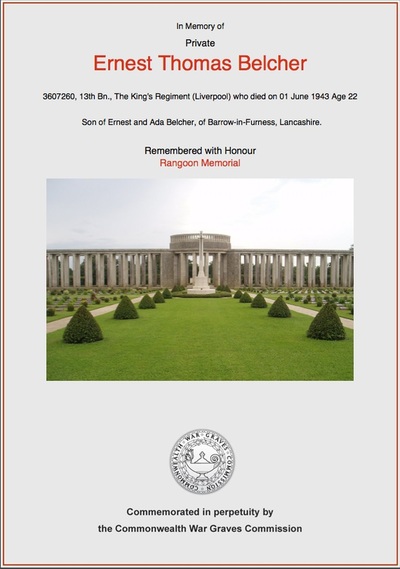

This story is dedicated to the memory of 3607260 Pte. Ernest Thomas Belcher, who died whilst serving with the 13th Battalion, The King's Regiment on the 1st June 1943.

In October this year (2014) I received an email contact from Jaqui Guise, who is Ernest's great niece, she told me that:

Ernest Belcher was my Nan's brother's son. I was raised to place a cross in memory of 'Young Ernie' each Remembrance Day and have done so all my life. I knew he served in the Chindits and died in a Japanese Prisoner of War Camp, I would appreciate any further information you may have. I have a photo of him if it would be of benefit to your research.

After reading the information you had about him on the website, it is heart breaking to realise he was so very near to escaping the horrors he must have faced. It is however better to be aware of this fact, as you feel he did not go through it alone in a way. Now we share those days with him.

I have read through the items on your site and from what I can gather Ernest most likely died in Maymyo Camp. I wish there were confirmation of this fact, but I realise this is impossible unless someone had witnessed what happened, survived and passed on the details. I dread to think what he endured there, but I know, with the manner in which he was raised, he would have endured this with courage, faith, valiant spirit, honour and retaining in his heart the love in which he was held.

Having exchanged several emails with Jaqui over the next few days, it was abundantly clear to me that we were speaking about a very special man, who was not only dearly loved and cared for by his family, but who had clearly the same compassionate and caring nature himself. Also, receiving Jaqui's email in late October seemed to be the catalyst for a sudden rush of family contacts with 142 Commando connections. There certainly seemed to be something in the air in regard to this unit at that time.

Ernest Thomas Belcher was the son of Ernest (Senior) and Ada Belcher and was born in Barrow in Furness, Cumbria and had an elder sister called Alice Maud. Ernest Senior, was born in Darlaston, West Midlands. He served on H.M.S. Revenge in the 1st World War, which was in action at the Battle of Jutland during the early summer of 1916. Ernest's mother Ada, was born in Barrow in Furness and it appears almost inevitable that the naval dock yards and shipbuilding in Barrow during the war, brought her and her husband together.

‘Young Ernie’ Belcher served in The Loyal Regiment prior to travelling to India and being posted to the 13th King's. He joined Chindit training at the Saugor Camp in the Central Provinces of India on the 30th September 1942. It is not known whether Ernest Belcher or his comrades from the Loyal Regiment had been previously employed as Commandos, but regardless of this fact, he was placed in to the 142 Commando Platoon for Chindit Column 1 and served with this unit throughout training and during the operation in Burma.

142 Commando had been created in June 1942 at Jubbulpore, India, by the former commander of No. 6 Commando, Lieutenant-Colonel Timothy Fetherstonhaugh. No. 6 Commando had previously served in Europe during WW2, most notably in Norway during late 1941. Once in India, Fetherstonhaugh took recruits from the Bush Warfare School at Maymyo and the 204 Military Mission, which had been raised in anticipation of sending groups of men into the Chinese/Burma borders to help train and equip the Chinese Army in readiness for any Japanese invasion.

With the Draft recognition code of RZGHA, the newly formed 142 Commando moved over to the Chindit training centre in Patharia and presumably the eight commando platoons were supplemented by men such as Ernest Belcher at this stage.

Chindit Column 1 was predominantly a Gurkha unit, with only a smattering of British Officers, Signalmen and Radio operators serving amongst the men from Nepal. The 142 Commando Platoon was the only unit in the column made up entirely from British personnel.

Major George Dunlop was chosen as commander of Column 1 in late 1942, replacing Gurkha Officer Vivian Weatherall at almost the last minute before entering Burma. Dunlop had worked with Mike Calvert during the British retreat from Burma the year before, performing acts of sabotage against the advancing Japanese Army. He had learned the trade of jungle warfare at the clandestine Bush Warfare School located at the hill station town of Maymyo. His arrival at Saugor had been delayed due to ill health, Dunlop had contracted cholera on the march out of Burma in April 1942 and had needed a much longer period of recuperation than was first thought necessary.

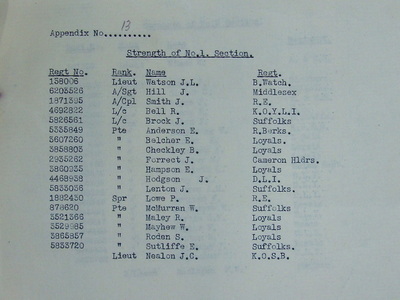

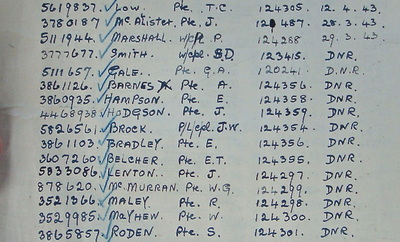

Seen below are some images in relation to Pte. Belcher and his time with 142 Commando. These include the nominal roll for the Commandos of Chindit Column 1, their unit insignia and a photograph of Major George Dunlop MC. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

In October this year (2014) I received an email contact from Jaqui Guise, who is Ernest's great niece, she told me that:

Ernest Belcher was my Nan's brother's son. I was raised to place a cross in memory of 'Young Ernie' each Remembrance Day and have done so all my life. I knew he served in the Chindits and died in a Japanese Prisoner of War Camp, I would appreciate any further information you may have. I have a photo of him if it would be of benefit to your research.

After reading the information you had about him on the website, it is heart breaking to realise he was so very near to escaping the horrors he must have faced. It is however better to be aware of this fact, as you feel he did not go through it alone in a way. Now we share those days with him.

I have read through the items on your site and from what I can gather Ernest most likely died in Maymyo Camp. I wish there were confirmation of this fact, but I realise this is impossible unless someone had witnessed what happened, survived and passed on the details. I dread to think what he endured there, but I know, with the manner in which he was raised, he would have endured this with courage, faith, valiant spirit, honour and retaining in his heart the love in which he was held.

Having exchanged several emails with Jaqui over the next few days, it was abundantly clear to me that we were speaking about a very special man, who was not only dearly loved and cared for by his family, but who had clearly the same compassionate and caring nature himself. Also, receiving Jaqui's email in late October seemed to be the catalyst for a sudden rush of family contacts with 142 Commando connections. There certainly seemed to be something in the air in regard to this unit at that time.

Ernest Thomas Belcher was the son of Ernest (Senior) and Ada Belcher and was born in Barrow in Furness, Cumbria and had an elder sister called Alice Maud. Ernest Senior, was born in Darlaston, West Midlands. He served on H.M.S. Revenge in the 1st World War, which was in action at the Battle of Jutland during the early summer of 1916. Ernest's mother Ada, was born in Barrow in Furness and it appears almost inevitable that the naval dock yards and shipbuilding in Barrow during the war, brought her and her husband together.

‘Young Ernie’ Belcher served in The Loyal Regiment prior to travelling to India and being posted to the 13th King's. He joined Chindit training at the Saugor Camp in the Central Provinces of India on the 30th September 1942. It is not known whether Ernest Belcher or his comrades from the Loyal Regiment had been previously employed as Commandos, but regardless of this fact, he was placed in to the 142 Commando Platoon for Chindit Column 1 and served with this unit throughout training and during the operation in Burma.

142 Commando had been created in June 1942 at Jubbulpore, India, by the former commander of No. 6 Commando, Lieutenant-Colonel Timothy Fetherstonhaugh. No. 6 Commando had previously served in Europe during WW2, most notably in Norway during late 1941. Once in India, Fetherstonhaugh took recruits from the Bush Warfare School at Maymyo and the 204 Military Mission, which had been raised in anticipation of sending groups of men into the Chinese/Burma borders to help train and equip the Chinese Army in readiness for any Japanese invasion.

With the Draft recognition code of RZGHA, the newly formed 142 Commando moved over to the Chindit training centre in Patharia and presumably the eight commando platoons were supplemented by men such as Ernest Belcher at this stage.

Chindit Column 1 was predominantly a Gurkha unit, with only a smattering of British Officers, Signalmen and Radio operators serving amongst the men from Nepal. The 142 Commando Platoon was the only unit in the column made up entirely from British personnel.

Major George Dunlop was chosen as commander of Column 1 in late 1942, replacing Gurkha Officer Vivian Weatherall at almost the last minute before entering Burma. Dunlop had worked with Mike Calvert during the British retreat from Burma the year before, performing acts of sabotage against the advancing Japanese Army. He had learned the trade of jungle warfare at the clandestine Bush Warfare School located at the hill station town of Maymyo. His arrival at Saugor had been delayed due to ill health, Dunlop had contracted cholera on the march out of Burma in April 1942 and had needed a much longer period of recuperation than was first thought necessary.

Seen below are some images in relation to Pte. Belcher and his time with 142 Commando. These include the nominal roll for the Commandos of Chindit Column 1, their unit insignia and a photograph of Major George Dunlop MC. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Major Dunlop's unit formed part of Southern Group on Operation Longcloth, which consisted of Gurkha Columns 1 and 2, and Southern Group Head Quarters. Southern Group was used by Wingate as a decoy on the operation, the intention being for them to draw attention away from the main Chindit columns of Northern Group whilst they crossed the Chindwin River and moved quickly east toward their targets along the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway.

Southern Group crossed the Chindwin on 15/16th February 1943 at a place called Auktang. Their orders were to march toward their own prime objective, the rail station at Kyaikthin. They marched openly along well known local trails and paths and also received a large supply drop from the air, which must have announced their presence in the area to the Japanese. The decoy group were accompanied at this time by a Company of Sikh Mountain Artillery and a section of Seaforth Highlanders. These supplementary units were to create a further diversion for Wingate by attacking the town of Pantha, alerting the enemy to the possibility that there might well be a full-scale re-invasion taking place. To all intents and purposes these tactics succeeded and Northern Group did proceed unmolested toward their objectives.

On the 2nd March Columns 1 and 2 had reached the outskirts of Kyaikthin, Dunlop was given the order to blow up the railway bridge, whilst Column 2 under the command of Major Arthur Emmett along with Group HQ were to head on towards the rail station itself. What neither group realised was that the Japanese had by now closed in on the unsuspecting Chindits and lay in wait just a short way up the tracks. To make matters worse the two Gurkha columns had also lost radio contact with each other. Column 2 and Group Head Quarters, in the black of night stumbled into an enemy ambush which straddled both sides of the railway line embankment.

The Chindits were taken by surprise during that terrible night and suffered many casualties. After dispersal was called and amongst much confusion the men disengaged from the enemy at Kyaikthin and withdrew into the surrounding jungle. Many of the surviving Chindits mistakenly turned west and set off back to India. Some of the remainder, having received the correct instructions moved on eastwards toward the Irrawaddy River. It was here that they joined up with Major Dunlop and Column 1 on about the 7-8th March.

From this moment on the two groups moved as one unit, with Dunlop sharing command with Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander, the overall commander of Southern Group. By the time full dispersal was called by Brigadier Wingate on the 29th March, Column 1 found themselves the furthest east of any of the surviving Chindit units. After eventually deciding to return to India rather than try for the Chinese Yunnan Borders, the group suffered a long a arduous journey back, including having to re-cross both the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers. Over the coming weeks the column lost many men, some through sharp engagements with the enemy, but the majority simply due to thirst, starvation and total exhaustion.

Ernest had managed to keep himself going during this time. I would imagine that the men of the Commando Platoon would have been used in the vanguard of the column as it moved slowly westward, checking the route ahead and dealing with any potential enemy interference. By early May the group had reached the approaches to the Chindwin valley and were searching for food in some of the local villages in that area.

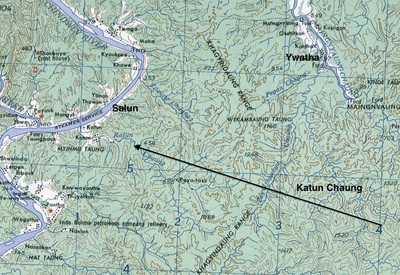

It was at this point that disaster struck Column 1 and the Commando Platoon in particular. With some of the platoon away attempting to find food in the village of Ywatha, the column was approached by some local Burmese militia. It was not long afterwards near a small stream called the Katun Chaung, that the Chindits were attacked by the Japanese. The men scattered in all directions, with the majority of the Commandos, along with Major Dunlop moving quickly away in the direction of the nearby hills.

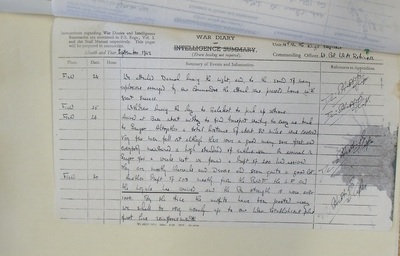

From his own diary report written after the operation, Dunlop remembered that incident:

Towards the Chindwin.

That evening Nealon (by this time the commander of the Commando Platoon) asked if he might try his luck at getting food at Ywatha, as his British troops could not go on without it. The remnants of my command being somewhat pathetic, I said yes, thinking that they might at least have a chance.

He set off with his party and an hour later we heard a fight at the village, very short and sharp.

There followed more days of hunger and climbing those infernal hills. One night all the mule Jemadar's party disappeared, leaving me with the doctor Captain Stocks, Lts. Clarke, Fowler, MacHorton, the No. 2 Guerrilla Platoon Officer, two Signallers and three or four Gurkhas, including my clerk who could speak both English and Burmese.

Eventually we killed a buffalo on the Katun Chaung. While cutting it up we were approached by a party of Burmans armed with rifles and war dahs. They told us that no Japanese were about, but, as we heard mortar fire earlier on from the direction of the Chindwin, I did not believe them. We disarmed them and they fled up a spur. The clerk wanted to go with them but we stopped him.

Much shouting followed and I guessed that their Japanese masters were up there. I gave the order to scatter from the open paddy.

Ernest Belcher was one of the men with Dunlop at the Katun Chaung. A witness statement made by Lieutenant P.W. MacLagan, an officer previously with the Commando Platoon from Column 2, stated that:

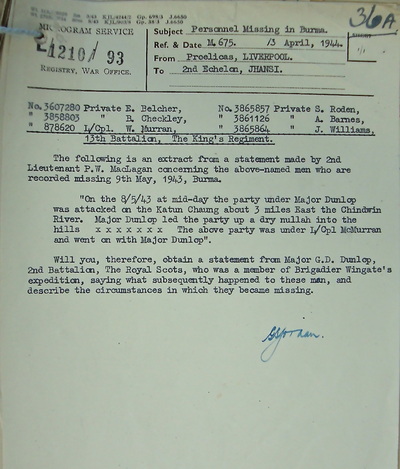

In regard to Ptes. Belcher, Checkley, Roden, Barnes and Williams and Lance Corporal W. McMurran.

"On the 8th May 1943 at mid-day, the party under Major Dunlop was attacked on the Katun Chaung about 3 miles from the Chindwin River. Major Dunlop led the party up a dry nullah into the surrounding hills. The above mentioned men were in a group led by Lance Corporal McMurran which went on with Major Dunlop."

The report then goes on to recommend that a statement is obtained from Major Dunlop in order to further clarify what happened to these men. In Dunlop's own debrief documents for 1943 he mentions that in the area close to the east banks of the Chindwin there were many Japanese and Burmese fighting patrols, all on the lookout for the Chindits attempting to escape back to India.

Seen below are some more images in relation to this incident. Firstly, a map of the Katun Chaung and the area just east of the Chindwin River, also shown is the original copy of Lieut. MacLagan's witness statement and a list of men missing in action from the 13th King's in 1943, including an entry for Pte. Ernest Belcher. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Southern Group crossed the Chindwin on 15/16th February 1943 at a place called Auktang. Their orders were to march toward their own prime objective, the rail station at Kyaikthin. They marched openly along well known local trails and paths and also received a large supply drop from the air, which must have announced their presence in the area to the Japanese. The decoy group were accompanied at this time by a Company of Sikh Mountain Artillery and a section of Seaforth Highlanders. These supplementary units were to create a further diversion for Wingate by attacking the town of Pantha, alerting the enemy to the possibility that there might well be a full-scale re-invasion taking place. To all intents and purposes these tactics succeeded and Northern Group did proceed unmolested toward their objectives.

On the 2nd March Columns 1 and 2 had reached the outskirts of Kyaikthin, Dunlop was given the order to blow up the railway bridge, whilst Column 2 under the command of Major Arthur Emmett along with Group HQ were to head on towards the rail station itself. What neither group realised was that the Japanese had by now closed in on the unsuspecting Chindits and lay in wait just a short way up the tracks. To make matters worse the two Gurkha columns had also lost radio contact with each other. Column 2 and Group Head Quarters, in the black of night stumbled into an enemy ambush which straddled both sides of the railway line embankment.

The Chindits were taken by surprise during that terrible night and suffered many casualties. After dispersal was called and amongst much confusion the men disengaged from the enemy at Kyaikthin and withdrew into the surrounding jungle. Many of the surviving Chindits mistakenly turned west and set off back to India. Some of the remainder, having received the correct instructions moved on eastwards toward the Irrawaddy River. It was here that they joined up with Major Dunlop and Column 1 on about the 7-8th March.

From this moment on the two groups moved as one unit, with Dunlop sharing command with Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander, the overall commander of Southern Group. By the time full dispersal was called by Brigadier Wingate on the 29th March, Column 1 found themselves the furthest east of any of the surviving Chindit units. After eventually deciding to return to India rather than try for the Chinese Yunnan Borders, the group suffered a long a arduous journey back, including having to re-cross both the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers. Over the coming weeks the column lost many men, some through sharp engagements with the enemy, but the majority simply due to thirst, starvation and total exhaustion.

Ernest had managed to keep himself going during this time. I would imagine that the men of the Commando Platoon would have been used in the vanguard of the column as it moved slowly westward, checking the route ahead and dealing with any potential enemy interference. By early May the group had reached the approaches to the Chindwin valley and were searching for food in some of the local villages in that area.

It was at this point that disaster struck Column 1 and the Commando Platoon in particular. With some of the platoon away attempting to find food in the village of Ywatha, the column was approached by some local Burmese militia. It was not long afterwards near a small stream called the Katun Chaung, that the Chindits were attacked by the Japanese. The men scattered in all directions, with the majority of the Commandos, along with Major Dunlop moving quickly away in the direction of the nearby hills.

From his own diary report written after the operation, Dunlop remembered that incident:

Towards the Chindwin.

That evening Nealon (by this time the commander of the Commando Platoon) asked if he might try his luck at getting food at Ywatha, as his British troops could not go on without it. The remnants of my command being somewhat pathetic, I said yes, thinking that they might at least have a chance.

He set off with his party and an hour later we heard a fight at the village, very short and sharp.

There followed more days of hunger and climbing those infernal hills. One night all the mule Jemadar's party disappeared, leaving me with the doctor Captain Stocks, Lts. Clarke, Fowler, MacHorton, the No. 2 Guerrilla Platoon Officer, two Signallers and three or four Gurkhas, including my clerk who could speak both English and Burmese.

Eventually we killed a buffalo on the Katun Chaung. While cutting it up we were approached by a party of Burmans armed with rifles and war dahs. They told us that no Japanese were about, but, as we heard mortar fire earlier on from the direction of the Chindwin, I did not believe them. We disarmed them and they fled up a spur. The clerk wanted to go with them but we stopped him.

Much shouting followed and I guessed that their Japanese masters were up there. I gave the order to scatter from the open paddy.

Ernest Belcher was one of the men with Dunlop at the Katun Chaung. A witness statement made by Lieutenant P.W. MacLagan, an officer previously with the Commando Platoon from Column 2, stated that:

In regard to Ptes. Belcher, Checkley, Roden, Barnes and Williams and Lance Corporal W. McMurran.

"On the 8th May 1943 at mid-day, the party under Major Dunlop was attacked on the Katun Chaung about 3 miles from the Chindwin River. Major Dunlop led the party up a dry nullah into the surrounding hills. The above mentioned men were in a group led by Lance Corporal McMurran which went on with Major Dunlop."

The report then goes on to recommend that a statement is obtained from Major Dunlop in order to further clarify what happened to these men. In Dunlop's own debrief documents for 1943 he mentions that in the area close to the east banks of the Chindwin there were many Japanese and Burmese fighting patrols, all on the lookout for the Chindits attempting to escape back to India.

Seen below are some more images in relation to this incident. Firstly, a map of the Katun Chaung and the area just east of the Chindwin River, also shown is the original copy of Lieut. MacLagan's witness statement and a list of men missing in action from the 13th King's in 1943, including an entry for Pte. Ernest Belcher. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Amongst the documents that I passed on to the family of Ernest Belcher was the debrief diary of George Dunlop. After reading through the diary, Jaqui, Ernest's great-niece told me:

Steve, I have read through the diary; didn't they go through so much; freezing cold, heat, hunger, thirst, dehydration, exhaustion, lice and absolute terror. You feel you want to wave a magic wand and take them all away from the pages of pain and re-write it all for them and bring them home.

Jaqui then asked me about the Burmese involvement with the Japanese and what I felt had possibly happened at the Katun Chaung on the 8th May 1943. I replied:

I would say that there was a larger party of men with Dunlop at the Katun Chaung, possibly all of the Commandos from both Column 1 and those he inherited from Column 2, men like Albert Barnes and John Williams, plus others. Many of the local Burmese villagers were helping the Japanese by keeping watch for the Chindit stragglers as they attempted to get back to India and re-cross the Chindwin River.

The report by MacLagan focuses on McMurran's section of men:

Roden and Williams, who are killed on or shortly after the 8th May. Ernest Belcher and Albert Barnes who are held as POW's, with Albert perishing at Kalewa and Ernest probably at the Maymyo Camp.

Albert Checkley and William McMurran also became prisoners, but survived their time in Rangoon Jail and returned home in mid-1945. I do know that William McMurran was captured two days later on the 10th May, so it is possible that the others were on the run with him for a time. I'm sure that other men did escape that day and made it across the Chindwin with Major Dunlop.

As mentioned above, it is possible that Ernest Belcher was taken to the Maymyo Concentration Camp after his capture. The Japanese were picking up Chindit soldiers from all over the area in-between the Chindwin and Irrawaddy Rivers during April-May 1943. They decided to hold them all initially at Maymyo. For more information about this camp and the men who it seems likely perished there, please follow the link below:

The Maymyo Camp

When I was in Burma in 2008 we visited Maymyo, but unfortunately I did not know the town's significance to the Chindit's story at that time. We did go into the Christian Cemetery at Maymyo, but there were no WW2 graves as far as I could see. I'd love to go back and spend a good amount of time in there now, possibly with the help of a knowledgeable local guide.

Ernest Belcher died according to his CWGC details on the 1st June 1943. It is impossible to confirm the exact location of his burial and no grave was recorded or at least remembered by any of the surviving Chindits from Operation Longcloth. He is therefore remembered upon the Rangoon Memorial in Taukkyan War Cemetery situated on the outskirts of the city. This memorial was created to honour all those casualties from the Burma campaign who had no known grave and there are some 26,000 names featured on its stone panels.

I was able to find on line, a copy of Ernest Belcher's Army Will. The document showed his home address and next of kin details. Also featured on the form were his chosen witnesses for the signing of the Will. One witness was Lance Corporal T. Griffin. This man was promoted to Acting Sergeant in late 1942, but did not go into Burma, he was posted to work at the Air Supply Base at Agartala, where he sorted the supplies and rations for the Chindit Columns once the operation had begun. He was originally with the Dorset Regiment.

The other witness was John Watson. This man features on the Column 1 Commando lists seen earlier in this story, and was the original commander of the platoon. He was formerly with the Black Watch Regiment before joining Chindit training at Saugor.

Lieutenant Watson led his platoon all the way up to the Chindwin River in 1943, but was seriously hurt when his horse threw him out of his saddle on the 9th February. He was transported back to India and hospitalised. Lieutenant John Nealon took over command at this point and led the Commandos for the rest of the operation. With hindsight, one might say that Watson's fall ultimately saved his life, especially when you consider the survival rate of men from Column 1 and in particular the 142 Commando Platoon.

I would like to allow Jaqui, Ernest Belcher's great-niece, to have the final word in this story. I very much enjoyed our email conversations and the she has shown great understanding and given welcome support to my aim to bring as many stories to these website pages as I possibly can.

Steve, I'm so pleased you found the photos and information I have sent of use and interest. It must be a profound emotional moment for you, after all the dedication you have devoted to the memory of the men of the 13th King's, to finally meet one of their number, who you know by name and have shared his journey, face to face via a photograph. I'm certain if Ernie were able, he would thank you in person for enabling me to 'be with him' after all this time. I'm sure he is thanking you from above.

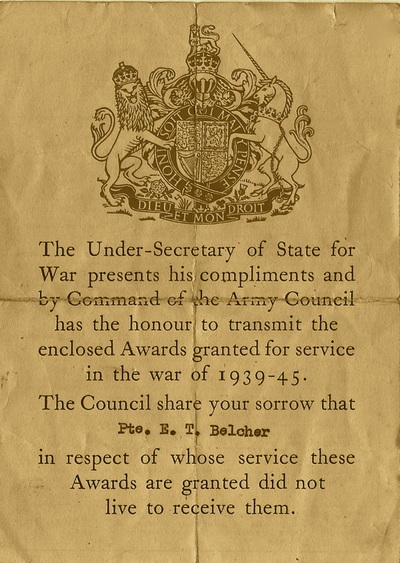

Seen below are some final images illustrating the story of Pte. Ernest Thomas Belcher. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Steve, I have read through the diary; didn't they go through so much; freezing cold, heat, hunger, thirst, dehydration, exhaustion, lice and absolute terror. You feel you want to wave a magic wand and take them all away from the pages of pain and re-write it all for them and bring them home.

Jaqui then asked me about the Burmese involvement with the Japanese and what I felt had possibly happened at the Katun Chaung on the 8th May 1943. I replied:

I would say that there was a larger party of men with Dunlop at the Katun Chaung, possibly all of the Commandos from both Column 1 and those he inherited from Column 2, men like Albert Barnes and John Williams, plus others. Many of the local Burmese villagers were helping the Japanese by keeping watch for the Chindit stragglers as they attempted to get back to India and re-cross the Chindwin River.

The report by MacLagan focuses on McMurran's section of men:

Roden and Williams, who are killed on or shortly after the 8th May. Ernest Belcher and Albert Barnes who are held as POW's, with Albert perishing at Kalewa and Ernest probably at the Maymyo Camp.

Albert Checkley and William McMurran also became prisoners, but survived their time in Rangoon Jail and returned home in mid-1945. I do know that William McMurran was captured two days later on the 10th May, so it is possible that the others were on the run with him for a time. I'm sure that other men did escape that day and made it across the Chindwin with Major Dunlop.

As mentioned above, it is possible that Ernest Belcher was taken to the Maymyo Concentration Camp after his capture. The Japanese were picking up Chindit soldiers from all over the area in-between the Chindwin and Irrawaddy Rivers during April-May 1943. They decided to hold them all initially at Maymyo. For more information about this camp and the men who it seems likely perished there, please follow the link below:

The Maymyo Camp

When I was in Burma in 2008 we visited Maymyo, but unfortunately I did not know the town's significance to the Chindit's story at that time. We did go into the Christian Cemetery at Maymyo, but there were no WW2 graves as far as I could see. I'd love to go back and spend a good amount of time in there now, possibly with the help of a knowledgeable local guide.

Ernest Belcher died according to his CWGC details on the 1st June 1943. It is impossible to confirm the exact location of his burial and no grave was recorded or at least remembered by any of the surviving Chindits from Operation Longcloth. He is therefore remembered upon the Rangoon Memorial in Taukkyan War Cemetery situated on the outskirts of the city. This memorial was created to honour all those casualties from the Burma campaign who had no known grave and there are some 26,000 names featured on its stone panels.

I was able to find on line, a copy of Ernest Belcher's Army Will. The document showed his home address and next of kin details. Also featured on the form were his chosen witnesses for the signing of the Will. One witness was Lance Corporal T. Griffin. This man was promoted to Acting Sergeant in late 1942, but did not go into Burma, he was posted to work at the Air Supply Base at Agartala, where he sorted the supplies and rations for the Chindit Columns once the operation had begun. He was originally with the Dorset Regiment.

The other witness was John Watson. This man features on the Column 1 Commando lists seen earlier in this story, and was the original commander of the platoon. He was formerly with the Black Watch Regiment before joining Chindit training at Saugor.

Lieutenant Watson led his platoon all the way up to the Chindwin River in 1943, but was seriously hurt when his horse threw him out of his saddle on the 9th February. He was transported back to India and hospitalised. Lieutenant John Nealon took over command at this point and led the Commandos for the rest of the operation. With hindsight, one might say that Watson's fall ultimately saved his life, especially when you consider the survival rate of men from Column 1 and in particular the 142 Commando Platoon.

I would like to allow Jaqui, Ernest Belcher's great-niece, to have the final word in this story. I very much enjoyed our email conversations and the she has shown great understanding and given welcome support to my aim to bring as many stories to these website pages as I possibly can.

Steve, I'm so pleased you found the photos and information I have sent of use and interest. It must be a profound emotional moment for you, after all the dedication you have devoted to the memory of the men of the 13th King's, to finally meet one of their number, who you know by name and have shared his journey, face to face via a photograph. I'm certain if Ernie were able, he would thank you in person for enabling me to 'be with him' after all this time. I'm sure he is thanking you from above.

Seen below are some final images illustrating the story of Pte. Ernest Thomas Belcher. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Lieutenant Ian MacHorton.

Lieutenant Ian MacHorton.

Update 15/07/2015.

Whilst re-reading the book 'Safer than a Known Way', the enthralling memoir of Lieutenant Ian MacHorton, a young Gurkha officer from the first Chindit operation and a member of Chindit Column 2 in 1943, I came across a description by the author of the ambush at the Katun Chaung. This passage comes towards the end of MacHorton's narrative, but adds a little more detail to the previous accounts of the incident given by Major Dunlop and Lieutenant MacLagan.

Here is an extended quote from the book describing the desperate and exhausted condition of the men present at the chaung and their reaction to the surprise arrival of some Burmese villagers, who were clearly in collaboration with the Japanese:

Suddenly some bushes farther downstream began to wave alarmingly. One after the other every firearm our little party possessed was raised to point that way. Then a great clumsy, grey-skinned water buffalo came lumbering out to slummock its way into the languid shallows at the river's edge. "This is where we eat!" exclaimed George Dunlop. "Take him, Sergeant. Just one shot is all we want."

The sergeant fired and the water buffalo keeled over and flopped into the shallow water. As fast as we could we waded across the wide chaung. Then we fell upon the carcass of the buffalo like a pack of emaciated savages, with knives, kukris and bare finger-nails. We hacked and clawed the warm meat and with horrible sounds drank the hot blood as it flowed from the carcass. We were standing there, quite oblivious of caution or of anything but our savage desire to eat, when a high-pitched shout from the other side of the chaung suddenly startled us all into turning round.

There, at the edge of the clearing, we saw a Burmese waving a white flag on a stick. The flag looked ill-omened as it fluttered there raggedly against the deep green wall of the jungle. "All of you stay where you are!" said George Dunlop. Then he stepped out into the water and waded across to where the Burmese had now been joined by two others.

The man waving the white flag was wearing the typical Burmese lungyi, but his head was crowned with a Western bowler hat. This dignified headgear no doubt signified he was the headman. "Just keep still and don't move," John Griffiths ordered. "If they are enemies and we scare them they might shoot the Major." We all stood there too obsessed by the possible danger of the situation even to chew the red meat which we still held in our hands. Then we noticed with apprehension that George Dunlop's lips, as he turned and began to wade back, showed no sign of a smile of relief. They were set in a tight, grim line.

"They are Burmese Traitor Army," he said in a low voice, as he came up. "They have just given me a surrender ultimatum. And there are Japs there behind them in the jungle. That headman with the flag told me that they had informed the Japs of our presence."

George Dunlop continued. "Apparently they heard our shot and did not even wait to come and see who we were. They had an idea that there would be British troops in the area and sent word to the Japs at once. They have armed men just behind them in the jungle. They have given us three minutes to surrender. The alternative is death."

The utter despair which we all felt at this latest turn in our fortunes showed clearly on every face. We were now so near the Chindwin and safety, and yet here we were caught in this trap with armed, traitor Burmese and Japs on one side, and more Japs undoubtedly working up the other side. Surrender or death were our alternatives, at a moment when we knew that safety was probably only a few miles farther west. "Every man has a right to decide for himself." Major Dunlop was speaking quickly and earnestly. "We have just one minute left. Those who intend to stay and surrender get down behind that buffalo. Those who do not, follow me!" And even as he finished speaking, he turned and made a dash through the shallow water towards the opposite steep bank which was thick with undergrowth right down to the water's edge.

Immediately bullets were whipping and whining about us. I heard them crash into the foliage beyond us and thud into the sand by our feet. With every ounce of strength left in me I lurched desperately towards the high bank. I never looked back. Once again it was every man for himself, and perhaps by now I was more experienced than any of them at this kind of survival.

Of the men present at the Katun Chaung, we know that several of the officers, including Dunlop and MacHorton made it back to Allied lines within the next few days, whilst other men were captured by the Japanese shortly after the ambush and began their varying periods as prisoners of war. It is still impossible to say exactly what happened to Ernest Belcher during or after the incident at the Katun Chaung, although it is likely that he fell into Japanese hands not long after this episode. I wonder now if he was wounded during the attempted evasion of the enemy that day, or that the trials and tribulations of the operation had simply caught up with him and he no longer had the energy to carry on. Regrettably, we may never find out.

Whilst re-reading the book 'Safer than a Known Way', the enthralling memoir of Lieutenant Ian MacHorton, a young Gurkha officer from the first Chindit operation and a member of Chindit Column 2 in 1943, I came across a description by the author of the ambush at the Katun Chaung. This passage comes towards the end of MacHorton's narrative, but adds a little more detail to the previous accounts of the incident given by Major Dunlop and Lieutenant MacLagan.

Here is an extended quote from the book describing the desperate and exhausted condition of the men present at the chaung and their reaction to the surprise arrival of some Burmese villagers, who were clearly in collaboration with the Japanese:

Suddenly some bushes farther downstream began to wave alarmingly. One after the other every firearm our little party possessed was raised to point that way. Then a great clumsy, grey-skinned water buffalo came lumbering out to slummock its way into the languid shallows at the river's edge. "This is where we eat!" exclaimed George Dunlop. "Take him, Sergeant. Just one shot is all we want."

The sergeant fired and the water buffalo keeled over and flopped into the shallow water. As fast as we could we waded across the wide chaung. Then we fell upon the carcass of the buffalo like a pack of emaciated savages, with knives, kukris and bare finger-nails. We hacked and clawed the warm meat and with horrible sounds drank the hot blood as it flowed from the carcass. We were standing there, quite oblivious of caution or of anything but our savage desire to eat, when a high-pitched shout from the other side of the chaung suddenly startled us all into turning round.

There, at the edge of the clearing, we saw a Burmese waving a white flag on a stick. The flag looked ill-omened as it fluttered there raggedly against the deep green wall of the jungle. "All of you stay where you are!" said George Dunlop. Then he stepped out into the water and waded across to where the Burmese had now been joined by two others.

The man waving the white flag was wearing the typical Burmese lungyi, but his head was crowned with a Western bowler hat. This dignified headgear no doubt signified he was the headman. "Just keep still and don't move," John Griffiths ordered. "If they are enemies and we scare them they might shoot the Major." We all stood there too obsessed by the possible danger of the situation even to chew the red meat which we still held in our hands. Then we noticed with apprehension that George Dunlop's lips, as he turned and began to wade back, showed no sign of a smile of relief. They were set in a tight, grim line.

"They are Burmese Traitor Army," he said in a low voice, as he came up. "They have just given me a surrender ultimatum. And there are Japs there behind them in the jungle. That headman with the flag told me that they had informed the Japs of our presence."

George Dunlop continued. "Apparently they heard our shot and did not even wait to come and see who we were. They had an idea that there would be British troops in the area and sent word to the Japs at once. They have armed men just behind them in the jungle. They have given us three minutes to surrender. The alternative is death."

The utter despair which we all felt at this latest turn in our fortunes showed clearly on every face. We were now so near the Chindwin and safety, and yet here we were caught in this trap with armed, traitor Burmese and Japs on one side, and more Japs undoubtedly working up the other side. Surrender or death were our alternatives, at a moment when we knew that safety was probably only a few miles farther west. "Every man has a right to decide for himself." Major Dunlop was speaking quickly and earnestly. "We have just one minute left. Those who intend to stay and surrender get down behind that buffalo. Those who do not, follow me!" And even as he finished speaking, he turned and made a dash through the shallow water towards the opposite steep bank which was thick with undergrowth right down to the water's edge.

Immediately bullets were whipping and whining about us. I heard them crash into the foliage beyond us and thud into the sand by our feet. With every ounce of strength left in me I lurched desperately towards the high bank. I never looked back. Once again it was every man for himself, and perhaps by now I was more experienced than any of them at this kind of survival.

Of the men present at the Katun Chaung, we know that several of the officers, including Dunlop and MacHorton made it back to Allied lines within the next few days, whilst other men were captured by the Japanese shortly after the ambush and began their varying periods as prisoners of war. It is still impossible to say exactly what happened to Ernest Belcher during or after the incident at the Katun Chaung, although it is likely that he fell into Japanese hands not long after this episode. I wonder now if he was wounded during the attempted evasion of the enemy that day, or that the trials and tribulations of the operation had simply caught up with him and he no longer had the energy to carry on. Regrettably, we may never find out.

Update 04/10/2015.

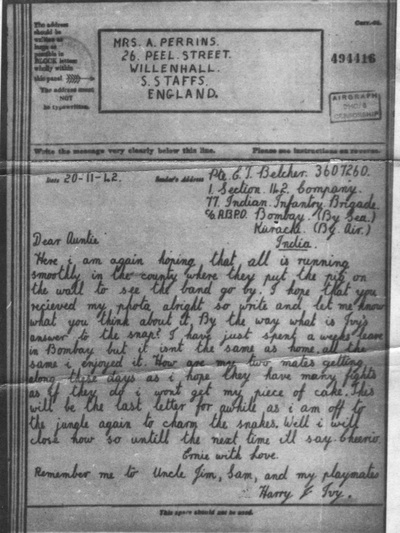

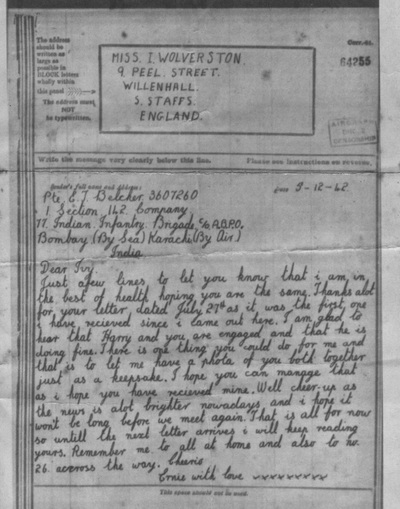

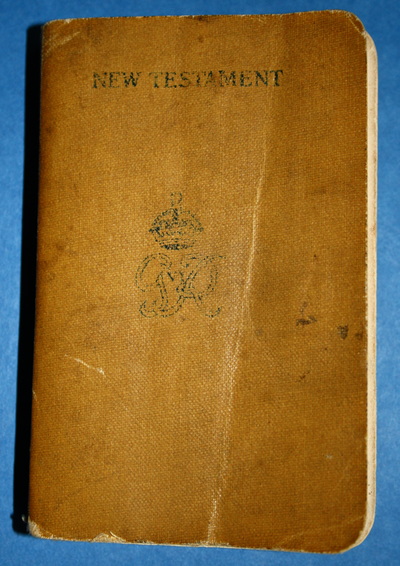

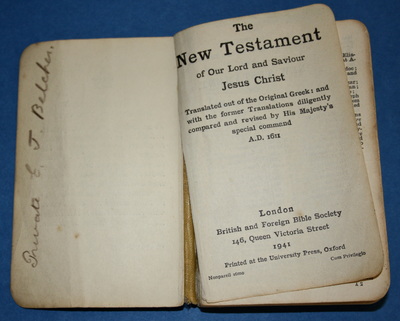

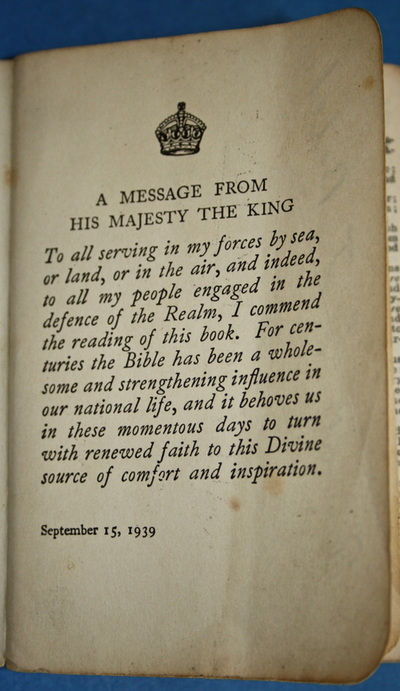

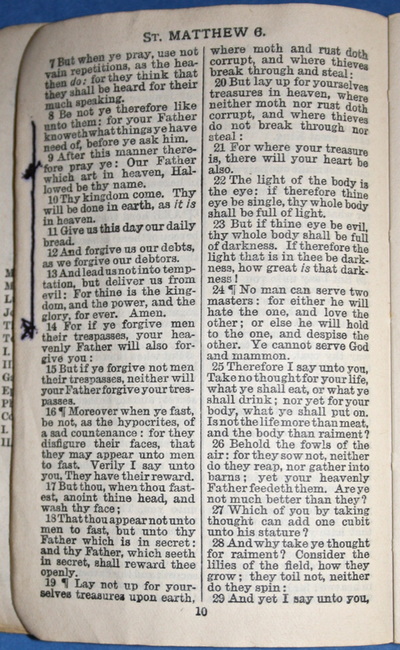

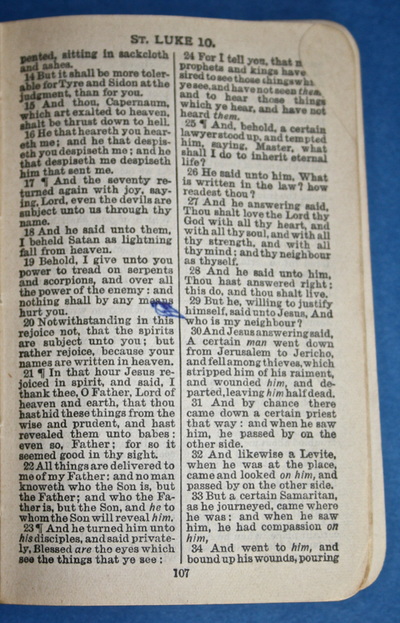

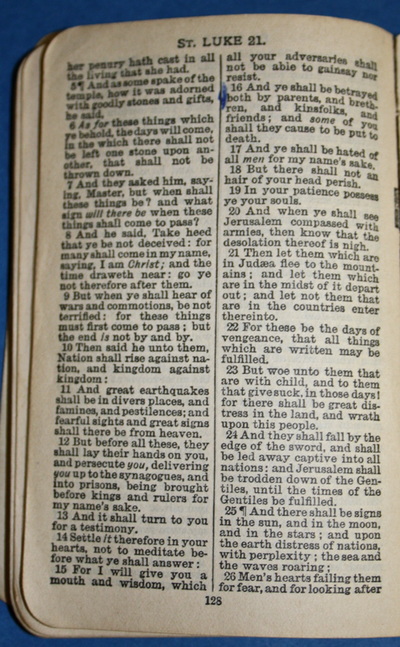

Thanks once again to the kindness of Ernest Belcher's great niece, Jaqui, seen below are some more images in relation his wartime story. These include some of his Airgram letters home and images of his Army issue Bible, including the passages he picked out during his time in Burma during 1943. This gallery, perhaps more than any other, shows something of the character of the man and reflects on his values, his faith and his true focus in life, which was always his family.

Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Thanks once again to the kindness of Ernest Belcher's great niece, Jaqui, seen below are some more images in relation his wartime story. These include some of his Airgram letters home and images of his Army issue Bible, including the passages he picked out during his time in Burma during 1943. This gallery, perhaps more than any other, shows something of the character of the man and reflects on his values, his faith and his true focus in life, which was always his family.

Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and Jaqui Guise, November 2014.