Captain Vivian Earle

A young Lieutenant Earle in 1939.

A young Lieutenant Earle in 1939.

In January 2010 I was part of a discussion concerning the South Lancashire Regiment and it's involvement in the British raids in Norway during 1940/41. This discussion then expanded deep into the Special Forces arena and the commandos in particular, but still with the emphasis on the South Lancashire Regiment. The name A.V. Earle cropped up in both conversations.

Three years later, in January 2013, a new dialogue began in relation to Lieutenant Earle and his WW2 pathway, this time on the WW2Talk internet forum. My real interest in this soldier revolved around his Chindit pedigree and that he had eventually become a prisoner of war, being held by the Japanese initially at Rangoon Jail. It was through the discussion on the WW2Talk forum that contact was made by the extended Earle family in the form of daughter-in-law Mary Earle.

Mary posted:

Good morning,

My name is Mary Earle, my husband is Clive Vivian Earle, the son of Albert Vivian. Clive found your forum while Googling for information about his father while we were watching the Remembrance Service. We were so interested to read all your input.

Sadly Vivian died in 1982 at home in Zimbabwe where the family had lived for years. We still have all his medals and also some of his other war time souvenirs including two ceremonial swords. It was also very interesting to see his index card from being a POW. We will put our heads together to see if we can come up with some more details for you.

With Mary's information and some extra input from Vivian's daughter, Rowena, I was able to put together a brief résumé of Lieutenant Earle's Army career and WW2 service.

Major A. V. Earle

Information as shown in the Army Lists held at the British National Archives at Kew, London.

Albert Vivian Earle. Born 1st April 1918. Son of Albert and Annie Augusta Earle of 26 Stokewood Road, Bournemouth, Hampshire.

South Lancashire Regiment (The Prince of Wales's Volunteers). Army number 74662.

2nd Lieutenant Commission on the 27th January 1938.

Army List for July 1940. To be Lieutenant.

Army List for April 1946. To be Captain.

Army List for April 1947. Rank of Temporary Major.

Army List for April 1951. To be Major.

Army List for August 1953. Qualified Japanese interpreter 1st Class.

Also awarded the MBE, gazetted on the 21st April 1953.

Army List for April 1956. Officer I/C Cadet Company at Eaton Hall Officer Cadet School, Chester.

Major Earle disappears from the Army Lists September 1958.

As mentioned previously, Vivian Earle first came to my attention in relation to his activities with the South Lancashire Regiment and their involvement with Special Forces work in Norway in 1941. In April that year the British 164th Brigade, made up of the 9th Battalion the King's Regiment, and the 1/4th and 2/4th South Lancashire's were chosen to form part of No. 4 Independent Company Commandos. It is not one hundred per cent definite, but it is possible that Lieutenant Earle was a member of this new company and that he took part in the raids against the Germans on the Lofoten Islands off the coast of Norway.

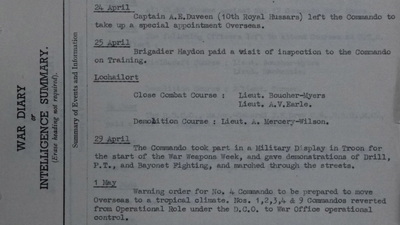

In the 1941 War diary for No. 4 Commando, there is an entry dated 25th April, which confirms Vivian's presence at the Special Forces HQ at Lochailort in Scotland. He is stated as attending a 'close combat' course, along with another officer, Lieutenant Boucher-Myers. A few days later the unit are warned to prepare for overseas duty to a tropical climate. It is highly likely that this posting referred to India as the destination, but it is also possible that it might have been Malaya or Singapore.

Seen below are two images in relation to this story. Firstly, an extract from the No. 4 Commando War diary, showing Vivian's presence at Lochailort and secondly a photograph of him with Lieutenant Bill Nimmo of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. I strongly believe that this photograph was taken in Scotland during 1941. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

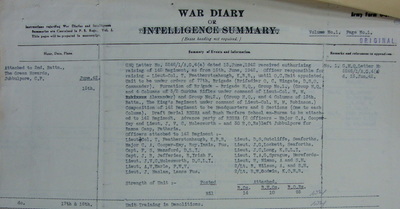

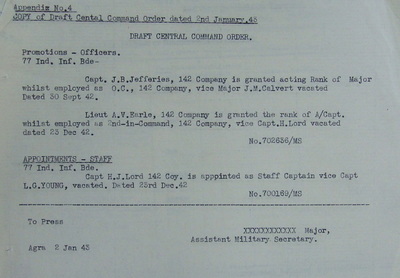

By the middle of 1942 Lieutenant Earle is present in India and is attached to the 2nd Battalion, the Green Howard's and part of the fledgling 142 Commando, based at Jubbulpore. 142 Commando were originally commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel T. Featherstonehaugh, formerly of the King's Royal Rifles and No. 6 Commando.

On the 13th July 1942, command of 142 Commando was given over to Major Mike Calvert of the Royal Engineers, who was by then under the auspices of Brigadier Orde Charles Wingate. The unit was then supplemented by soldiers from the Bush Warfare School based at Maymyo and the 204 Chinese Military Mission. Both these units had experience in Special Forces operations behind enemy lines and had only recently returned from expeditions in Burma and the Yunnan Provinces of China. It was at this time that 142 Commando moved to their new Chindit training camp at Saugor in the Central Provinces of India.

Coincidently, also present with 142 Commando at this time was Lieutenant William Nimmo. This young officer had already served on clandestine missions in China before joining Wingate's Chindit Brigade in mid-1942 and went on to work with numerous SOE Forces in Burma throughout the war. Both officers formed part of the original command structure for 142 Commando prior to the units handover to the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, Vivian Earle continued to prosper within the ranks, and on 2nd January 1943 was promoted to second in command by Wingate.

This promotion occurred just six weeks before the first Chindit expedition entered Burma. Each Chindit Column had one platoon of Commandos, usually made up of:

1 Commanding Officer, usually a Lieutenant promoted to Acting/Captain.

1 2nd Lieutenant

1 Sergeant

1 Corporal

2 Lance Corporals

1 Sapper from the Royal Engineers

12-14 Privates

Vivian, now with the rank of Acting-Captain was integral in many aspects of the units training regime, and actually taught classes himself in subjects such as handling explosives and unarmed combat. His Adjutant duties also included writing up the units War diary for some of the months at Saugor. I was never absolutely certain if Captain Earle had actually gone into Burma with the Chindits in 1943, or had simply been involved in their training. Confirmation of his participation on Operation Longcloth came when I discovered his prisoner of war details at the National Archives in London.

It seems likely to me (but cannot be confimed) that he served with Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters whilst in Burma. Captain Earle is not mentioned in any of the 13th King's war diaries, or any other official papers concerning the operation itself. Bernard Fergusson, in his book 'Beyond the Chindwin' does recount meeting Vivian and another junior officer, Lieutenant William Millar on the 23rd March close to the village of Baw. This village was the location of the final combined supply drop for the Brigade inside Burma, just before they dispersed into smaller parties and attempted the return journey to India.

Fergusson remembered Vivian and William Millar being present at the rendezvous with another officer, Major John Jeffries formerly of the Royal Irish Fusiliers. Jeffries had begun the expedition with 1 Column and had masqueraded as Wingate in the first few weeks in Burma, as part of the decoy group, ordered to march openly to the south of where the main Chindit Columns were operating. By early March and after crossing the Irrawaddy River, Jeffries had left 1 Column and joined up with Wingate's Brigade HQ. This is really the only written evidence that Captain Earle was part of Wingate's Head Quarters section on Operation Longcloth. Of course, it is quite possible that he had also travelled with Major Jeffries from 1 Column and had spent the first four weeks of the campaign with that unit.

Another clue to Vivian's membership of Wingate's HQ, at least post 23rd March, is the place where he was reportedly captured by the Japanese on the 15th April. The Chindits had troubled the Japanese lines of communication in February and March 1943, demolishing various pieces of the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway. In late March Wingate called an officers meeting and with the added advice of India General Command, decided to call it a day and return to India. On the 29th March his group attempted to re-cross the Irrawaddy at a place called Inywa, however, this crossing was abandoned due to enemy interference from the western banks. Wingate took his Head Quarters back into the jungle and waited for over a week before trying again. The men, having now split up into smaller groups at Inywa, struggled to find boats to get them across the river and this led to some of the parties trying their luck further south.

Vivian Earle was captured on the 15th April 1943 at the riverside village of Taugaung. This village is some thirty-five miles south of Inywa and was one of the more obvious crossing places in the locality. Another pointer to his membership of Brigade HQ is that several other men from that group were captured all along this particular stretch of the Irrawaddy during the month of April. To read more about one such dispersal party, please click on the following link: Pte. Leonard Coffin

Seen below are some more images in relation to Captain Vivian Earle and his time as a Chindit, including a map of the area around Taugaung on the Irrawaddy River. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

In the book Marxism and Resistance in Burma 1942-1945, written by Thakin Thein Pe Myint, the town of Taugaung is described thus:

Taugaung is situated on a small hill that rests its chin on the Irrawaddy riverside. Although famous as a historical site from which all Burma is supposed to originate, it is more like a country village. There are no ancient buildings of any significance. The former town wall appears as an old rampart, with what was once the moat now just a dry bed. The government archaeology department had shown an interest, but no excavations had been completed. The ruined stupas are said to be from the reign of Abi Raza, the King of Taugaung and a descendant of the Sakya Kings of India. The Japanese seemed to hold the town in some reverence and we heard no bad reports about the Japanese from the townsfolk.

On the 13th July 1942, command of 142 Commando was given over to Major Mike Calvert of the Royal Engineers, who was by then under the auspices of Brigadier Orde Charles Wingate. The unit was then supplemented by soldiers from the Bush Warfare School based at Maymyo and the 204 Chinese Military Mission. Both these units had experience in Special Forces operations behind enemy lines and had only recently returned from expeditions in Burma and the Yunnan Provinces of China. It was at this time that 142 Commando moved to their new Chindit training camp at Saugor in the Central Provinces of India.

Coincidently, also present with 142 Commando at this time was Lieutenant William Nimmo. This young officer had already served on clandestine missions in China before joining Wingate's Chindit Brigade in mid-1942 and went on to work with numerous SOE Forces in Burma throughout the war. Both officers formed part of the original command structure for 142 Commando prior to the units handover to the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, Vivian Earle continued to prosper within the ranks, and on 2nd January 1943 was promoted to second in command by Wingate.

This promotion occurred just six weeks before the first Chindit expedition entered Burma. Each Chindit Column had one platoon of Commandos, usually made up of:

1 Commanding Officer, usually a Lieutenant promoted to Acting/Captain.

1 2nd Lieutenant

1 Sergeant

1 Corporal

2 Lance Corporals

1 Sapper from the Royal Engineers

12-14 Privates

Vivian, now with the rank of Acting-Captain was integral in many aspects of the units training regime, and actually taught classes himself in subjects such as handling explosives and unarmed combat. His Adjutant duties also included writing up the units War diary for some of the months at Saugor. I was never absolutely certain if Captain Earle had actually gone into Burma with the Chindits in 1943, or had simply been involved in their training. Confirmation of his participation on Operation Longcloth came when I discovered his prisoner of war details at the National Archives in London.

It seems likely to me (but cannot be confimed) that he served with Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters whilst in Burma. Captain Earle is not mentioned in any of the 13th King's war diaries, or any other official papers concerning the operation itself. Bernard Fergusson, in his book 'Beyond the Chindwin' does recount meeting Vivian and another junior officer, Lieutenant William Millar on the 23rd March close to the village of Baw. This village was the location of the final combined supply drop for the Brigade inside Burma, just before they dispersed into smaller parties and attempted the return journey to India.

Fergusson remembered Vivian and William Millar being present at the rendezvous with another officer, Major John Jeffries formerly of the Royal Irish Fusiliers. Jeffries had begun the expedition with 1 Column and had masqueraded as Wingate in the first few weeks in Burma, as part of the decoy group, ordered to march openly to the south of where the main Chindit Columns were operating. By early March and after crossing the Irrawaddy River, Jeffries had left 1 Column and joined up with Wingate's Brigade HQ. This is really the only written evidence that Captain Earle was part of Wingate's Head Quarters section on Operation Longcloth. Of course, it is quite possible that he had also travelled with Major Jeffries from 1 Column and had spent the first four weeks of the campaign with that unit.

Another clue to Vivian's membership of Wingate's HQ, at least post 23rd March, is the place where he was reportedly captured by the Japanese on the 15th April. The Chindits had troubled the Japanese lines of communication in February and March 1943, demolishing various pieces of the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway. In late March Wingate called an officers meeting and with the added advice of India General Command, decided to call it a day and return to India. On the 29th March his group attempted to re-cross the Irrawaddy at a place called Inywa, however, this crossing was abandoned due to enemy interference from the western banks. Wingate took his Head Quarters back into the jungle and waited for over a week before trying again. The men, having now split up into smaller groups at Inywa, struggled to find boats to get them across the river and this led to some of the parties trying their luck further south.

Vivian Earle was captured on the 15th April 1943 at the riverside village of Taugaung. This village is some thirty-five miles south of Inywa and was one of the more obvious crossing places in the locality. Another pointer to his membership of Brigade HQ is that several other men from that group were captured all along this particular stretch of the Irrawaddy during the month of April. To read more about one such dispersal party, please click on the following link: Pte. Leonard Coffin

Seen below are some more images in relation to Captain Vivian Earle and his time as a Chindit, including a map of the area around Taugaung on the Irrawaddy River. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

In the book Marxism and Resistance in Burma 1942-1945, written by Thakin Thein Pe Myint, the town of Taugaung is described thus:

Taugaung is situated on a small hill that rests its chin on the Irrawaddy riverside. Although famous as a historical site from which all Burma is supposed to originate, it is more like a country village. There are no ancient buildings of any significance. The former town wall appears as an old rampart, with what was once the moat now just a dry bed. The government archaeology department had shown an interest, but no excavations had been completed. The ruined stupas are said to be from the reign of Abi Raza, the King of Taugaung and a descendant of the Sakya Kings of India. The Japanese seemed to hold the town in some reverence and we heard no bad reports about the Japanese from the townsfolk.

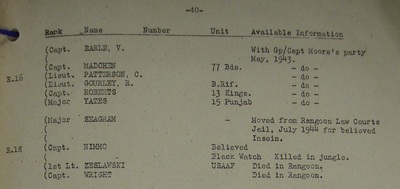

Many of the Chindit prisoners captured along the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy in April 1943 were collected together at the village of Tigyaing, located a few miles north of Tauguang. This group spent a few days at Tigyaing and generally speaking were treated decently by their captors. Eventually all the POW's were sent to the main concentration camp at Maymyo and it was here that they began to experience much harsher treatment from the Japanese. Around the end of May 1943, over 230 Chindit prisoners were sent down to Rangoon by train and took up residence in Block 6 of the city jail. Most of the officers with this group were immediately placed into solitary confinement.

In late May 1943 a group of Chindit officers were removed from Rangoon Central Jail and flown down to the Changi POW Camp in Singapore. My belief is that these men were recognised by the Japanese secret police, the Kempai-tai, as being of special interest and in need of further interrogation. All of these men survived their imprisonment in Singapore and would return home in early 1946. Sadly, many of the Chindits held at Rangoon Jail did not fare so well, including my own grandfather who died in Block 6 of the prison in June 1943. To read more about the Chindits who became prisoners of war, please click on the following link: Chindit POW's

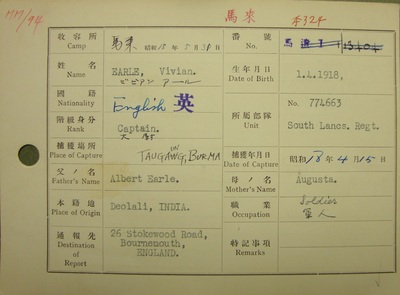

Several documents exist for Captain Earle that give some details about his time in Japanese hands. Amongst these is his POW index card. This document was compiled by British Administrators at Changi Jail in Singapore. It was an attempt to record the whereabouts and movements of all Allied personnel held by the Japanese in WW2, especially in relation to those who were sent to work on the infamous Death Railway or in the heavy industries of mainland Japan. Seen in the gallery below, it shows all the next of kin and Army service details for the soldier as well as his recorded date of capture. The top right hand corner of the card shows the various POW numbers which were allocated to Vivian Earle during his time as a prisoner of war.

The reverse of the index card shows what I believe to be Vivian's official date of release or liberation; the 2nd November 1945. It is written in Kanji script stating the year first, then the month followed by the day. The Japanese Showa calendar began again at the coronation of each new Emperor. So, the number 20 on the card equates to the 20th year of Hirohito's reign, that being 1945. I'm afraid I do not have a full translation for the sentence written on the reverse of the card.

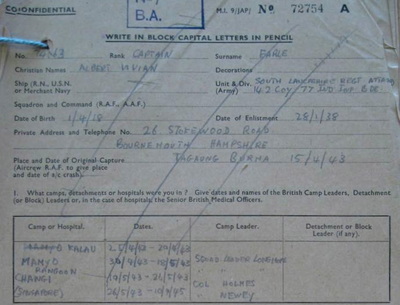

Vivian also completed a liberation questionnaire (seen below) after his release from captivity at Changi. The information shown on this form states that he was held for a short time at another POW camp in Burma, prior to his arrival at Maymyo. This was at the town of Kalaw, where he spent four days in late April. The liberation questionnaire also confirms his next of kin details and the senior British officer present in each of the camps in which he was held.

Seen below are the three pieces of paperwork that document Vivian's time as a prisoner of war. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

In late May 1943 a group of Chindit officers were removed from Rangoon Central Jail and flown down to the Changi POW Camp in Singapore. My belief is that these men were recognised by the Japanese secret police, the Kempai-tai, as being of special interest and in need of further interrogation. All of these men survived their imprisonment in Singapore and would return home in early 1946. Sadly, many of the Chindits held at Rangoon Jail did not fare so well, including my own grandfather who died in Block 6 of the prison in June 1943. To read more about the Chindits who became prisoners of war, please click on the following link: Chindit POW's

Several documents exist for Captain Earle that give some details about his time in Japanese hands. Amongst these is his POW index card. This document was compiled by British Administrators at Changi Jail in Singapore. It was an attempt to record the whereabouts and movements of all Allied personnel held by the Japanese in WW2, especially in relation to those who were sent to work on the infamous Death Railway or in the heavy industries of mainland Japan. Seen in the gallery below, it shows all the next of kin and Army service details for the soldier as well as his recorded date of capture. The top right hand corner of the card shows the various POW numbers which were allocated to Vivian Earle during his time as a prisoner of war.

The reverse of the index card shows what I believe to be Vivian's official date of release or liberation; the 2nd November 1945. It is written in Kanji script stating the year first, then the month followed by the day. The Japanese Showa calendar began again at the coronation of each new Emperor. So, the number 20 on the card equates to the 20th year of Hirohito's reign, that being 1945. I'm afraid I do not have a full translation for the sentence written on the reverse of the card.

Vivian also completed a liberation questionnaire (seen below) after his release from captivity at Changi. The information shown on this form states that he was held for a short time at another POW camp in Burma, prior to his arrival at Maymyo. This was at the town of Kalaw, where he spent four days in late April. The liberation questionnaire also confirms his next of kin details and the senior British officer present in each of the camps in which he was held.

Seen below are the three pieces of paperwork that document Vivian's time as a prisoner of war. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

The city of Rangoon was liberated in early May 1945, this meant that the surviving Chindit prisoners in the jail gained their freedom before any of the other camps in South East Asia. Changi wasn't liberated until after the Atomic bombs were dropped on mainland Japan in August 1945. This is why it took until November before the prisoners here could be repatriated to secure locations. The Chindits liberated from Rangoon were taken back to hospitals in India, with some travelling by air and others by hospital ship, I am not sure if those held at Changi went back to India, or remained for a time in Singapore.

At the time of his liberation Vivian Earle had obtained the temporary rank of Major, it was common practice for men to be promoted during their time as prisoners of war, this was usually agreed and administered by the British hierarchy present within the camp. Vivian would also have been automatically promoted from Lieutenant to Captain once he entered Burmese territory in February 1943. This was an idiosyncrasy of the Chindits, where every officer received a one rank promotion from Wingate in recognition of the unusual nature of the operation they were about to undertake. You will notice from the Army listings shown above, that it took quite a while for the official recognition of these promotions to come through on Vivian's service records.

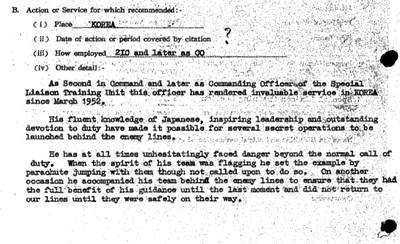

This is all I know about Major Earle's time in India and Burma. After the war he returned to the United Kingdom and in the first quarter of 1947, he married Patricia Harvey, with the wedding taking place in Patricia's home town of Bromley in Kent. In 1951 Vivian obtained the fully recognised rank of Major, two years later on the 4th February 1953 he was recommended for the award of MBE in recognition for his services during the Korean War. Vivian had commanded a 'Special Liaison Training Section' based at the British Administrative Centre at Kure in Japan. His citation reads:

As Second in Command and later as Commanding Officer of the Special Liaison Training Unit, this officer has rendered invaluable service in Korea since March 1952. His fluent knowledge of Japanese, inspiring leadership and outstanding devotion to duty have made it possible for several secret operations to be launched behind enemy lines.

He has at all times unhesitatingly faced danger beyond the normal call of duty. When the spirit of his team was flagging, he set the example by parachute jumping with them though not called to do so. On another occasion he accompanied his team behind the enemy lines to ensure that they had the full benefit of his guidance until the last moment and did not return to our lines until they were safely on their way.

So, it would appear that his time spent as a Chindit some ten years previous had not gone to waste, and is it too much of a coincidence to believe that during his two years as a prisoner of war in Singapore, he endeavoured to learn the Japanese language which would then serve both himself and his country so well in Korea.

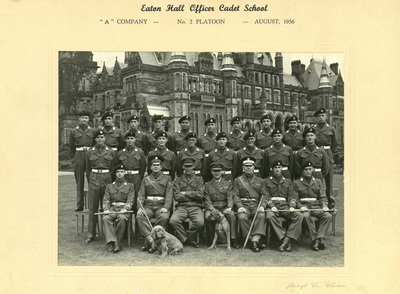

By the spring of 1956, Vivian was amongst the officers in charge of the Eaton Hall Officer Cadet Training Centre in Cheshire. He was a Company Commander and took charge of one of the four groups of Cadets that entered the establishment each year. For more information about the training centre at Eaton Hall, please click on the following link: www.cheshiremilitarymuseum.co.uk/eaton-hall/

As mentioned at the very beginning of this story, Vivian Earle and his young family emigrated to Zimbabwe and this is where he sadly died in February 1982. He had enjoyed a full and active career in the British Army during WW2 and beyond and had been involved in some of the most audacious Special Forces operations during those tumultuous years. Like so many of his contemporaries, Vivian did not speak too often about his wartime experiences.

I would like to thank, Mary, Rowena, Vanessa and Clive for their help in bringing this story to these website pages and for allowing me to include some of their family photographs to illustrate the text. Seen below is one final gallery of images, including a photograph of Vivian at Eaton Hall and an image showing the citation for his MBE. Please click on any particular image to bring it forward on the page.

At the time of his liberation Vivian Earle had obtained the temporary rank of Major, it was common practice for men to be promoted during their time as prisoners of war, this was usually agreed and administered by the British hierarchy present within the camp. Vivian would also have been automatically promoted from Lieutenant to Captain once he entered Burmese territory in February 1943. This was an idiosyncrasy of the Chindits, where every officer received a one rank promotion from Wingate in recognition of the unusual nature of the operation they were about to undertake. You will notice from the Army listings shown above, that it took quite a while for the official recognition of these promotions to come through on Vivian's service records.

This is all I know about Major Earle's time in India and Burma. After the war he returned to the United Kingdom and in the first quarter of 1947, he married Patricia Harvey, with the wedding taking place in Patricia's home town of Bromley in Kent. In 1951 Vivian obtained the fully recognised rank of Major, two years later on the 4th February 1953 he was recommended for the award of MBE in recognition for his services during the Korean War. Vivian had commanded a 'Special Liaison Training Section' based at the British Administrative Centre at Kure in Japan. His citation reads:

As Second in Command and later as Commanding Officer of the Special Liaison Training Unit, this officer has rendered invaluable service in Korea since March 1952. His fluent knowledge of Japanese, inspiring leadership and outstanding devotion to duty have made it possible for several secret operations to be launched behind enemy lines.

He has at all times unhesitatingly faced danger beyond the normal call of duty. When the spirit of his team was flagging, he set the example by parachute jumping with them though not called to do so. On another occasion he accompanied his team behind the enemy lines to ensure that they had the full benefit of his guidance until the last moment and did not return to our lines until they were safely on their way.

So, it would appear that his time spent as a Chindit some ten years previous had not gone to waste, and is it too much of a coincidence to believe that during his two years as a prisoner of war in Singapore, he endeavoured to learn the Japanese language which would then serve both himself and his country so well in Korea.

By the spring of 1956, Vivian was amongst the officers in charge of the Eaton Hall Officer Cadet Training Centre in Cheshire. He was a Company Commander and took charge of one of the four groups of Cadets that entered the establishment each year. For more information about the training centre at Eaton Hall, please click on the following link: www.cheshiremilitarymuseum.co.uk/eaton-hall/

As mentioned at the very beginning of this story, Vivian Earle and his young family emigrated to Zimbabwe and this is where he sadly died in February 1982. He had enjoyed a full and active career in the British Army during WW2 and beyond and had been involved in some of the most audacious Special Forces operations during those tumultuous years. Like so many of his contemporaries, Vivian did not speak too often about his wartime experiences.

I would like to thank, Mary, Rowena, Vanessa and Clive for their help in bringing this story to these website pages and for allowing me to include some of their family photographs to illustrate the text. Seen below is one final gallery of images, including a photograph of Vivian at Eaton Hall and an image showing the citation for his MBE. Please click on any particular image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 23/08/2015.

Vivian Earle's column placement has always been somewhat of a quandary. As mentioned previously, he is not referenced in any of the 13th King's war diaries for Operation Longcloth and is only mentioned once in any book on the subject.

Bernard Fergusson, in his book 'Beyond the Chindwin' places him at the village of Baw on the 23rd March 1943. This was where the Chindits took their final full Brigade supply drop over the 23-24th March. The supply drop was compromised early on the second day, when a Japanese patrol bumped into a platoon from 8 Column on the Mabein-Baw Road.

Directly after the incident at Baw, Wingate and his Brigade Head Quarters and Columns 5, 7 and 8 moved off in a northwesterly direction towards the Irrawaddy River. After a few days Wingate asked Major Fergusson and his column to act as decoy and lead the Japanese pursuers away to the north east. Wingate and the other two Chindit columns continued on to the Irrawaddy, aiming to reach the river close to the town of Inywa.

If Vivian remained with Major Jefferies, who Fergusson states he was with at Baw, then he would now be travelling with Wingate's Brigade HQ, accompanied by 7 & 8 Columns. On the 29th March this large group of Chindits attempted to cross the Irrawaddy just south of Inywa. 7 Column sent across the first boats to form a secure bridgehead on the western banks, but were attacked by a large Japanese patrol and many Chindits were killed.

Wingate abandoned the crossing and after ordering 7 & 8 Columns to march away in a easterly direction, took his HQ into the jungle close to Inywa and waited. His group spent seven days in this area, taking the opportunity to rest, dispose of and then consume their remaining mules and build up their strength for another attempt at crossing the river.

In relation to Vivian Earle, this would mean that on about the 8th April he would have set out with his allocated dispersal group to find a way across the river. All of the dispersal parties struggled to achieve this goal and many meandered around in the vicinity for many days. We know from his POW details that Vivian was captured at a place called Taugaung on the 15th April 1943. This location and date matches well with the pathway of some of the other dispersal parties from Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters.

The other possibility is that Captain Earle somehow re-joined 1 Column after his sojourn at Baw. This Chindit unit were positioned a fair way to the south, close to the town of Mong Mit, where the Shweli River turns east towards the Chinese Borders.

Vivian would have had enough time to make the distance between Baw and Mong Mit. However, 1 Column did not attempt to make for the Irrawaddy straight away in April 1943. Column commander, Major George Dunlop was intent on heading east and exiting Burma via the Yunnan Provinces and on the 10th April the column attempted a crossing of the Shweli.

Once again disaster struck and the Chindits were caught in mid-stream by a Japanese patrol, with high rates of casualties inflicted on the British side. Dunlop led the remainder of his column, some 350 men, away from the river and headed south west. After a time he struck directly west for the Irrawaddy and after a long and arduous journey, reached the eastern banks of this major obstacle on the 20th April.

Some of 1 Column crossed the Irrawaddy in two decrepit country boats from a launching point at the village of Taugaung. Although the location is correct, the date of this crossing, stated as between the 20-23rd April is over a week later than Vivian's date of capture on the 15th and so it seems unlikely that he was with this group.

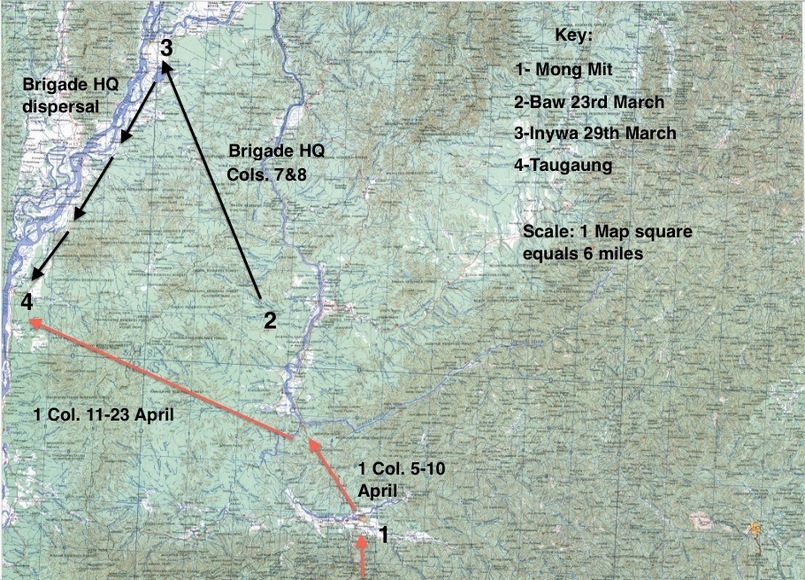

Seen below is a map of the area between the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers, this area became known as the 'bag' by the men of 77th Brigade in 1943. This was due to the feeling of being hemmed in, firstly by the two rivers on the north, west and eastern sides and secondly, the main motor road artery to the south near Mong Mit. The map shows the places mentioned in Vivian's story and the routes taken by the Chindit columns after dispersal was called. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

Vivian Earle's column placement has always been somewhat of a quandary. As mentioned previously, he is not referenced in any of the 13th King's war diaries for Operation Longcloth and is only mentioned once in any book on the subject.

Bernard Fergusson, in his book 'Beyond the Chindwin' places him at the village of Baw on the 23rd March 1943. This was where the Chindits took their final full Brigade supply drop over the 23-24th March. The supply drop was compromised early on the second day, when a Japanese patrol bumped into a platoon from 8 Column on the Mabein-Baw Road.

Directly after the incident at Baw, Wingate and his Brigade Head Quarters and Columns 5, 7 and 8 moved off in a northwesterly direction towards the Irrawaddy River. After a few days Wingate asked Major Fergusson and his column to act as decoy and lead the Japanese pursuers away to the north east. Wingate and the other two Chindit columns continued on to the Irrawaddy, aiming to reach the river close to the town of Inywa.

If Vivian remained with Major Jefferies, who Fergusson states he was with at Baw, then he would now be travelling with Wingate's Brigade HQ, accompanied by 7 & 8 Columns. On the 29th March this large group of Chindits attempted to cross the Irrawaddy just south of Inywa. 7 Column sent across the first boats to form a secure bridgehead on the western banks, but were attacked by a large Japanese patrol and many Chindits were killed.

Wingate abandoned the crossing and after ordering 7 & 8 Columns to march away in a easterly direction, took his HQ into the jungle close to Inywa and waited. His group spent seven days in this area, taking the opportunity to rest, dispose of and then consume their remaining mules and build up their strength for another attempt at crossing the river.

In relation to Vivian Earle, this would mean that on about the 8th April he would have set out with his allocated dispersal group to find a way across the river. All of the dispersal parties struggled to achieve this goal and many meandered around in the vicinity for many days. We know from his POW details that Vivian was captured at a place called Taugaung on the 15th April 1943. This location and date matches well with the pathway of some of the other dispersal parties from Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters.

The other possibility is that Captain Earle somehow re-joined 1 Column after his sojourn at Baw. This Chindit unit were positioned a fair way to the south, close to the town of Mong Mit, where the Shweli River turns east towards the Chinese Borders.

Vivian would have had enough time to make the distance between Baw and Mong Mit. However, 1 Column did not attempt to make for the Irrawaddy straight away in April 1943. Column commander, Major George Dunlop was intent on heading east and exiting Burma via the Yunnan Provinces and on the 10th April the column attempted a crossing of the Shweli.

Once again disaster struck and the Chindits were caught in mid-stream by a Japanese patrol, with high rates of casualties inflicted on the British side. Dunlop led the remainder of his column, some 350 men, away from the river and headed south west. After a time he struck directly west for the Irrawaddy and after a long and arduous journey, reached the eastern banks of this major obstacle on the 20th April.

Some of 1 Column crossed the Irrawaddy in two decrepit country boats from a launching point at the village of Taugaung. Although the location is correct, the date of this crossing, stated as between the 20-23rd April is over a week later than Vivian's date of capture on the 15th and so it seems unlikely that he was with this group.

Seen below is a map of the area between the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers, this area became known as the 'bag' by the men of 77th Brigade in 1943. This was due to the feeling of being hemmed in, firstly by the two rivers on the north, west and eastern sides and secondly, the main motor road artery to the south near Mong Mit. The map shows the places mentioned in Vivian's story and the routes taken by the Chindit columns after dispersal was called. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, July 2015.