Pte. Leonard Coffin

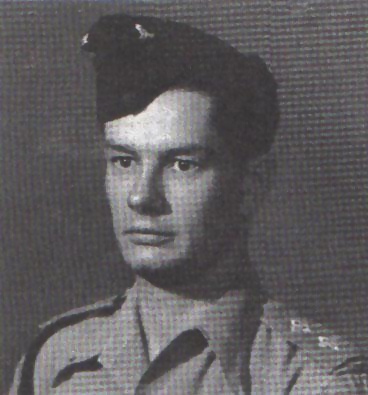

Leonard Coffin, India 1942.

Leonard Coffin, India 1942.

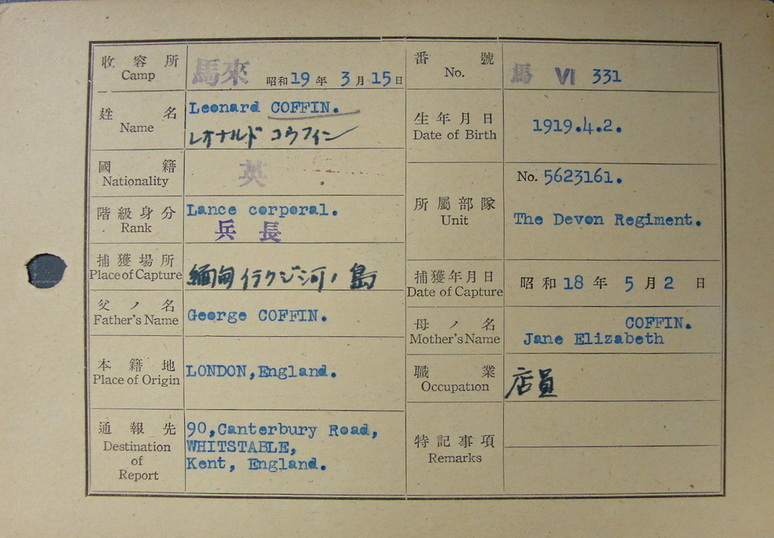

Pte. 5623161 Leonard Coffin was born on the 2nd April 1919, he was the son of George and Jane Elizabeth Coffin from London. Although London born, Leonard, much like my own grandfather was posted to the Devonshire Regiment after his initial infantry training had ended and it is possible that both men travelled to India aboard the same troopship in mid-1942.

The small draft of soldiers from the Devon's joined Chindit training at the Saugor Camp on the 26th September 1942. Leonard was placed in to the Northern Group Head Quarters commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel S.A. Cooke, formerly of the Lincolnshire Regiment.

Northern Group HQ spent most of its time in Burma in close proximity to Column 8 commanded by Major Walter Purcell Scott of the King's Regiment and were also never too far away from Wingate's own Brigade Head Quarters. On the 29th March 1943, Wingate's HQ, Chindit Columns 7 and 8 and Northern Group's Head Quarters were all gathered on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River close to the Burmese village of Inywa.

A bridgehead party was formed and began crossing the mile wide river in hired country boats, which were manned and piloted by local Burmese villagers. A Japanese patrol on the western banks opened up on the leading boats with machine gun and mortar fire and many casualties were inflicted on the Chindits attempting to cross the river. Wingate and his column commanders decided to abandon the crossing and moved back in to the scrub jungle close to the riverside.

Wingate made the decision to break up the large group of Chindits present at the river and ordered a general dispersal. Colonel Cooke decided to disperse with Column 8 and the two groups merged to form one large unit of approximately 400 personnel. This group headed east, eventually making a crossing of the less wide, but fast flowing Shweli River on the 3rd April.

After the confusion of the abandoned crossing of the Irrawaddy on the 29th March, it is very difficult to say which group Pte. Coffin dispersed with. It would be logical to assume that he continued on with Northern Group Head Quarters and Colonel Cooke, however two pieces of evidence suggest otherwise. Firstly, from the transcript of an audio memoir given by Pte. Fred Holloman, a member of Brigade HQ in 1943, it is suggested that Leonard was with a group of men who remained in the general area of the Irrawaddy close to the village of Inywa for over four weeks, desperately trying to find a way across the river.

Secondly, from the translation of some POW records for Pte. Coffin, it is stated that he was captured on an island in the Irrawaddy River on the 2nd May. This matches up perfectly with the Fred Holloman's full explanation of how his dispersal group attempted to cross the Irrawaddy that year, but were betrayed to the Japanese by some Burmese boatmen and became prisoners of war.

Fred Remembered:

There were about 25 men in my dispersal party, mostly British troops. Luckily, we had two Burmese soldiers with us, we called them 'Burrifs', which is just the title Burma Rifles squashed up into one word. Well, we would have been lost without them as none of us could speak Burmese and they would go into the villages for us and get us food and find out if there were any Japs nearby.

A couple of times there were Japs in these villages and we would have a bit of a scrap. The 'Burrifs' were very brave and got many of the 13th King's out to safety in 1943. In the end we decided to push up North into the Kachin territory, these people were always friendly towards us and still supported the British in Burma.

After moving around the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy for over four weeks the dispersal party, now led by Captain Graham Hosegood met up with some Burmese boatmen. These men promised to get the stricken Chindits over the river that night and told them to lie low for the rest of the day in the scrub-jungle nearby. The men waited nervously for several hours until darkness fell and at about midnight the boatmen returned to collect Chindits and ferry them across the river. Some of the British personnel were suspicious of these Burmese and as it turned out they were right to be so. The boatmen dropped their passengers off on the opposite bank and received their payment of 100 silver rupees.

As mentioned earlier the Burmese boatmen had in fact dropped the Chindits off, not on the western banks of the Irrawaddy, but on a large island in the middle of the river. The island was approximately a mile long and no less wide, the men spent several days moving up and down the beaches searching for a means of crossing the final section of the river. Cipher Officer Lieutenant 'Willie' Wilding was also with this group, he recalls:

The next six days are very confused in my mind. We searched the island, it was about a mile long and half a mile wide. We found a village and persuaded the villagers to sell us a meal, but this only occurred once. I had two black-outs which were alarming. When travelling in a hot country beware when the sweat getting into your eyes stops stinging as this denotes that you need salt.

On the 29th April we found a boat that floated. We decided that Second Lieutenant Pat Gordon, Lance-Corporal Purdie and Signalman Belcher, with Burma Riflemen Orlando and Tunnion as paddlers, should make the first trip. They reached the other side, then we heard Pat rallying his men and a good deal of firing and then silence. Orlando and Tunnion survived but the others were all killed. I was very sad. I thought that the first boat load would have the best chance, but I was wrong.

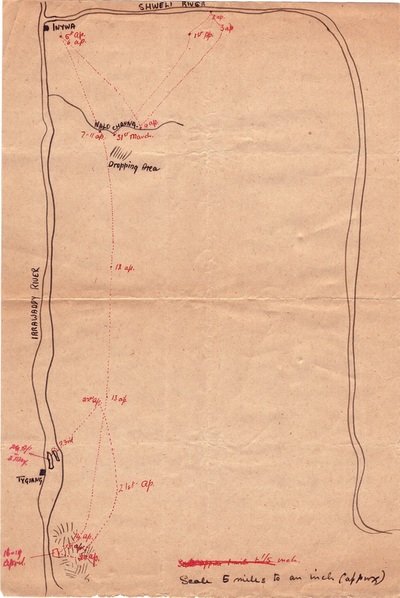

Seen below are two maps; one is of the area around the village of Tigyaing, situated on the western banks of the Irrawaddy almost directly opposite the island on which Fred Holloman and Leonard Coffin found themselves trapped in late April 1943. The other is a sketch map drawn by Lieutenant Wilding, showing the dispersal groups movements after the failed crossing of the Irrawaddy on the 29th March. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

The small draft of soldiers from the Devon's joined Chindit training at the Saugor Camp on the 26th September 1942. Leonard was placed in to the Northern Group Head Quarters commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel S.A. Cooke, formerly of the Lincolnshire Regiment.

Northern Group HQ spent most of its time in Burma in close proximity to Column 8 commanded by Major Walter Purcell Scott of the King's Regiment and were also never too far away from Wingate's own Brigade Head Quarters. On the 29th March 1943, Wingate's HQ, Chindit Columns 7 and 8 and Northern Group's Head Quarters were all gathered on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River close to the Burmese village of Inywa.

A bridgehead party was formed and began crossing the mile wide river in hired country boats, which were manned and piloted by local Burmese villagers. A Japanese patrol on the western banks opened up on the leading boats with machine gun and mortar fire and many casualties were inflicted on the Chindits attempting to cross the river. Wingate and his column commanders decided to abandon the crossing and moved back in to the scrub jungle close to the riverside.

Wingate made the decision to break up the large group of Chindits present at the river and ordered a general dispersal. Colonel Cooke decided to disperse with Column 8 and the two groups merged to form one large unit of approximately 400 personnel. This group headed east, eventually making a crossing of the less wide, but fast flowing Shweli River on the 3rd April.

After the confusion of the abandoned crossing of the Irrawaddy on the 29th March, it is very difficult to say which group Pte. Coffin dispersed with. It would be logical to assume that he continued on with Northern Group Head Quarters and Colonel Cooke, however two pieces of evidence suggest otherwise. Firstly, from the transcript of an audio memoir given by Pte. Fred Holloman, a member of Brigade HQ in 1943, it is suggested that Leonard was with a group of men who remained in the general area of the Irrawaddy close to the village of Inywa for over four weeks, desperately trying to find a way across the river.

Secondly, from the translation of some POW records for Pte. Coffin, it is stated that he was captured on an island in the Irrawaddy River on the 2nd May. This matches up perfectly with the Fred Holloman's full explanation of how his dispersal group attempted to cross the Irrawaddy that year, but were betrayed to the Japanese by some Burmese boatmen and became prisoners of war.

Fred Remembered:

There were about 25 men in my dispersal party, mostly British troops. Luckily, we had two Burmese soldiers with us, we called them 'Burrifs', which is just the title Burma Rifles squashed up into one word. Well, we would have been lost without them as none of us could speak Burmese and they would go into the villages for us and get us food and find out if there were any Japs nearby.

A couple of times there were Japs in these villages and we would have a bit of a scrap. The 'Burrifs' were very brave and got many of the 13th King's out to safety in 1943. In the end we decided to push up North into the Kachin territory, these people were always friendly towards us and still supported the British in Burma.

After moving around the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy for over four weeks the dispersal party, now led by Captain Graham Hosegood met up with some Burmese boatmen. These men promised to get the stricken Chindits over the river that night and told them to lie low for the rest of the day in the scrub-jungle nearby. The men waited nervously for several hours until darkness fell and at about midnight the boatmen returned to collect Chindits and ferry them across the river. Some of the British personnel were suspicious of these Burmese and as it turned out they were right to be so. The boatmen dropped their passengers off on the opposite bank and received their payment of 100 silver rupees.

As mentioned earlier the Burmese boatmen had in fact dropped the Chindits off, not on the western banks of the Irrawaddy, but on a large island in the middle of the river. The island was approximately a mile long and no less wide, the men spent several days moving up and down the beaches searching for a means of crossing the final section of the river. Cipher Officer Lieutenant 'Willie' Wilding was also with this group, he recalls:

The next six days are very confused in my mind. We searched the island, it was about a mile long and half a mile wide. We found a village and persuaded the villagers to sell us a meal, but this only occurred once. I had two black-outs which were alarming. When travelling in a hot country beware when the sweat getting into your eyes stops stinging as this denotes that you need salt.

On the 29th April we found a boat that floated. We decided that Second Lieutenant Pat Gordon, Lance-Corporal Purdie and Signalman Belcher, with Burma Riflemen Orlando and Tunnion as paddlers, should make the first trip. They reached the other side, then we heard Pat rallying his men and a good deal of firing and then silence. Orlando and Tunnion survived but the others were all killed. I was very sad. I thought that the first boat load would have the best chance, but I was wrong.

Seen below are two maps; one is of the area around the village of Tigyaing, situated on the western banks of the Irrawaddy almost directly opposite the island on which Fred Holloman and Leonard Coffin found themselves trapped in late April 1943. The other is a sketch map drawn by Lieutenant Wilding, showing the dispersal groups movements after the failed crossing of the Irrawaddy on the 29th March. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Leonard Coffin and Fred Holloman were to meet up with Burma Riflemen Tunnion and Orlando a few weeks later in the POW concentration camp at Maymyo. After the death of Lieutenant Gordon and the other men in his boat, the rest of the dispersal group moved back into the scrub-jungle on the island, but eventually it was decided that their position was untenable and Lieutenant Wilding decided to surrender the group to the Japanese.

To read more about Lieutenant Patrick Gordon and his time as a Chindit in 1943, please click on the following link: Robin Patrick Gordon

Before we continue on with Pte. Coffin's story and in particular his time as a prisoner of war, we need to return once more to the audio memoir of Fred Holloman. As part of his memoir Fred also recalled the moment when Brigadier Wingate had addressed the Chindits at the Irrawaddy on the 29th March, explaining to them why he believed they should break up into smaller units and attempt to get back to India in this fashion. It was within this section of his audio that he mentioned Leonard Coffin by name and what Leonard thought about Wingate's decision.

To emphasise the tone of Holloman's recollection I have recorded his words myself, rather than simply transcribe them onto the page. I have tried to be true to the recording and to Fred's accent, please forgive me if I have failed in my attempt.

To read more about Lieutenant Patrick Gordon and his time as a Chindit in 1943, please click on the following link: Robin Patrick Gordon

Before we continue on with Pte. Coffin's story and in particular his time as a prisoner of war, we need to return once more to the audio memoir of Fred Holloman. As part of his memoir Fred also recalled the moment when Brigadier Wingate had addressed the Chindits at the Irrawaddy on the 29th March, explaining to them why he believed they should break up into smaller units and attempt to get back to India in this fashion. It was within this section of his audio that he mentioned Leonard Coffin by name and what Leonard thought about Wingate's decision.

To emphasise the tone of Holloman's recollection I have recorded his words myself, rather than simply transcribe them onto the page. I have tried to be true to the recording and to Fred's accent, please forgive me if I have failed in my attempt.

Seen below are four photographs of Pte. Leonard Coffin and some of his Chindit comrades. These were taken in India before the men set out for Burma in February 1943. The first two photographs show Leonard with his pals enjoying some hard-earned leave in the bustling city of Bombay. The last two photographs are possibly from the days spent at the Saugor Camp in the Central Provinces of India. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

According to Leonard's POW records he was captured on the 2nd May 1943. As more and more of the men from Operation Longcloth became prisoners of war, the Japanese decide to move the captured Chindits to a larger camp in the hill station town of Maymyo. It was here that things really began to turn sour for the prisoners. Treatment at Maymyo Camp was severe and the guards also insisted on the POW's learning all commands and drills in the Japanese language. Failure to comply with these orders would often result in a beating and it was in Maymyo that the first Chindit POW deaths began to occur. It is suggested that the camp was located somewhere near to the railway station and quite close to the Bush Warfare School where Mike Calvert and some of the 142 Commandos had trained just a few months before.

It is difficult to say for sure how many Chindits were held at Maymyo, but by the middle of May there were probably the best part of 200 men present in the camp. Conditions and treatment at Maymyo, combined with the exhaustion and starvation of the expedition meant that men began to fall ill and ultimately die in the cramped sheds, which were no bigger than the bathing huts found at English seaside resorts. I would estimate that approximately 20 men died at Maymyo, with perhaps another 10 or so losing their fight for life when the Chindits were eventually moved down to Rangoon in late May or early June. I first thought that all 200 or so Chindits were sent by rail to Rangoon in one group, but recent documents have shown that this was not the case. Several journeys were needed to transport them all to the city jail and this took two or three weeks to complete.

To read more about the Maymyo Camp, please click on the following link: Maymyo Camp

On arrival at Rangoon the men were at first placed into the solitary confinement cells located in Block 5 of the jail. Officers could spend many weeks in these cells, as they were put through long hours of interrogation by the Japanese Kempai-tai or secret police. Other Ranks, such as Leonard Coffin and Fred Holloman were soon moved over to Block 6, which was to become home for the captured Chindit soldiers of Operation Longcloth for the next two years. Leonard was given the POW number 331 during his time as a prisoner of war; he was expected to recite this

number in Japanese to any questioning by the prison guards and also at the morning and evening roll calls, known as tenkos in the jail.

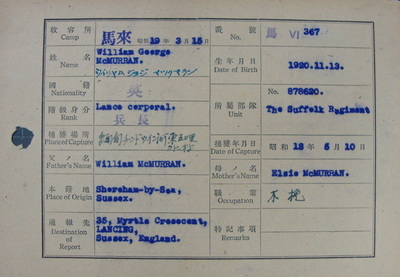

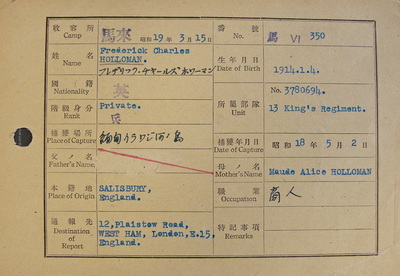

I noticed from Leonard Coffin's POW index card (shown below) that his rank is stated as Lance Corporal. It was often the case that men were promoted whilst prisoners of war, especially if they had shown some qualities of leadership during that period or had helped their fellow inmates in some way or other.

As time went by the prisoners inside Rangoon Jail noticed the tide of war was turning against their Japanese captors. News of recent British victories slowly filtered into the prison and the obvious increase in Allied aircraft overhead helped boost the morale of the men as they went about their daily rituals. Eventually in April 1945 the Japanese decided to move as many POW’s as possible back to Japan by marching them out of Burma and into Thailand.

Some 400 men were classified as fit to make this trip and on the 24th of April they marched out of the jail for the last time. After five gruelling days and having covered about 55 miles, they found themselves at a village called Waw close to the town of Pegu. The Japanese Commandant now realising that the ailing POW's were holding up his own departure from Burma released the prisoners at this point. They were effectively in 'no man's land' with firing coming from all sides, but eventually the majority of the party were found and liberated by soldiers from the West Yorkshire Regiment and sent back to the relative safety of Allied held lines.

It is difficult to say for sure how many Chindits were held at Maymyo, but by the middle of May there were probably the best part of 200 men present in the camp. Conditions and treatment at Maymyo, combined with the exhaustion and starvation of the expedition meant that men began to fall ill and ultimately die in the cramped sheds, which were no bigger than the bathing huts found at English seaside resorts. I would estimate that approximately 20 men died at Maymyo, with perhaps another 10 or so losing their fight for life when the Chindits were eventually moved down to Rangoon in late May or early June. I first thought that all 200 or so Chindits were sent by rail to Rangoon in one group, but recent documents have shown that this was not the case. Several journeys were needed to transport them all to the city jail and this took two or three weeks to complete.

To read more about the Maymyo Camp, please click on the following link: Maymyo Camp

On arrival at Rangoon the men were at first placed into the solitary confinement cells located in Block 5 of the jail. Officers could spend many weeks in these cells, as they were put through long hours of interrogation by the Japanese Kempai-tai or secret police. Other Ranks, such as Leonard Coffin and Fred Holloman were soon moved over to Block 6, which was to become home for the captured Chindit soldiers of Operation Longcloth for the next two years. Leonard was given the POW number 331 during his time as a prisoner of war; he was expected to recite this

number in Japanese to any questioning by the prison guards and also at the morning and evening roll calls, known as tenkos in the jail.

I noticed from Leonard Coffin's POW index card (shown below) that his rank is stated as Lance Corporal. It was often the case that men were promoted whilst prisoners of war, especially if they had shown some qualities of leadership during that period or had helped their fellow inmates in some way or other.

As time went by the prisoners inside Rangoon Jail noticed the tide of war was turning against their Japanese captors. News of recent British victories slowly filtered into the prison and the obvious increase in Allied aircraft overhead helped boost the morale of the men as they went about their daily rituals. Eventually in April 1945 the Japanese decided to move as many POW’s as possible back to Japan by marching them out of Burma and into Thailand.

Some 400 men were classified as fit to make this trip and on the 24th of April they marched out of the jail for the last time. After five gruelling days and having covered about 55 miles, they found themselves at a village called Waw close to the town of Pegu. The Japanese Commandant now realising that the ailing POW's were holding up his own departure from Burma released the prisoners at this point. They were effectively in 'no man's land' with firing coming from all sides, but eventually the majority of the party were found and liberated by soldiers from the West Yorkshire Regiment and sent back to the relative safety of Allied held lines.

Leonard Coffin was not one of the men liberated by the West Yorkshire Regiment at the village of Waw. Some prisoners had already decided to abscond from the march towards Pegu, fearing that if they were taken into Thailand by the Japanese, they would never get to see their homes or loved ones again. Leonard had been discussing the idea of escape with another prisoner called Denis Gavin. Denis had been with the East Surrey Regiment in Malaya during the fight for Singapore in February 1942. He and some other men from that time had made a valiant attempt to evade capture by sailing a small boat across the Bay of Bengal in the hope of reaching Ceylon or the eastern shores of India. They sadly fell short of their goal and were captured by the Japanese when their boat drifted ashore along the Burmese coastline.

In his book 'Quiet Jungle, Angry Sea', Denis Gavin tells the story of the attempted escape from Singapore and later on in the book, his and Leonard's break for freedom on the Pegu march:

We were to march north to Pegu to get to the head of the Bay and then move east away from the war towards Siam. It was generally felt that a break must be made before we passed Pegu and got too far away from our own troops.

As the miles went by and nothing was heard of the Brigadier's plans, many of us became uneasy and wondered if his talk was not just a put-off to hold us together until it was too late to attempt escape. We knew he was capable of thinking himself justified in such a move to avoid deaths or hardship, but when he was tackled about his motives he produced a plan of escape just east of Pegu. This decided me and I determined that even if I went alone I was not going past Pegu with the column, and accordingly set about forming a gang. I dare not tackle the escape alone with my poor vision and my old comrades scattered.

Lissy and Dicky were sick in Rangoon, Tiny was in a different part of the column. I seized on my remaining friend, Titch Hudson. Physically I was less than half a man now, and although my mind was still clear I needed someone else to lean on. Titch and I soon got recruits as the legend of our adventures from Singapore was impressive and Len Coffin of the Kings, Dinger Bell and Bill McMurran, both of 17th Indian Infantry Division, joined us.

NB. Lissy, Dicky, Titch Hudson and Tiny were all part of the crew aboard Denis's escape boat from Singapore.

Titch got shifted on the column and we lost him, but the remainder of us kept together by volunteering to manhandle en route one of the bullock carts which held our stores. As the miles went by we systematically looted this bullock cart during each air raid and gradually filled a sack with rice, matches, candles, water bottles, peas, tea and sugar. These air raids were real shoot-ups by questing Spitfires and Hurricanes. They became so persistent that by the 26th we were pinned down in a copse and couldn't move from it during daylight.

Even here there was no respite, and the thicket was bombed time and again during the day. These raids were really a godsend to us as the Japanese and everyone else were pinned down in ditches and trenches and we were able to make unobserved visits to our vehicle for loot. It was decided to make a break during the first raid that night. But when we were startled into activity by a roll call we found that Pete Wilson, Lofty Eastgate and two other Australians, Ron Hadden and Harvey Besley, had already made their escape and we realised that now the Japanese would be on the alert. A council of war left us resolved to watch for the first opportunity, night or day, and we sat down to wait for the next raid.

It wasn't long before a batch of Spitfires were merrily shooting up and bombing our copse. With shaking hearts we gathered our gear and started to walk away. Three years previously I would have had the confidence of fighting manhood and there would have been excitement and zest in the adventure, but now I was sick and trembling, and ready to panic if we were spotted. We got almost to the edge of the copse when we saw the nearest Japanese sentry in his ditch between us and freedom, and we almost gave up there and then at the sight of him.

However, the thought of freedom in the next few minutes against that of captivity for the next few years was too much and I could not let one Japanese soldier stand in my way. Back we went to our resting comrades and managed to get an invaluable cook's knife, long and sharp, from one of the cooks and we stealthily made our way back to the sentry. I was going to go up to the sentry, who only I knew. If he challenged my right to be away from the centre of the copse I was going to make a plea of fear of the bombs until I could get close enough to him to plunge my knife into his heart.

But something had happened to me in prison and even when I was sitting down, with him lying beside me on his stomach, I could not bring myself to do it. I had gone soft in camp and was no longer a man, and could not even bring myself to hurt him. Besides I liked this bloke, as I had grown to like many of the Japanese. The situation was only saved by the man himself getting up and going on his patrol.

In a few moments my gang were with me and racing across the open paddy field to the jungle and freedom 200 yards away. The jungle swallowed us without sound, but we continued to run, wildly and hysterically, until we had to stop and lie panting. We stayed only until our breath returned and then we were off again always to the west, and our Allies, until at last the sun went down and we had to wait for the stars to appear and guide us. Dawn, and waiting for the sun gave us our first rest and then on again until the sun high in the sky had made west indistinguishable from east, north or south. Here we cooked our first meal and rested again until the waning sun gave us our direction and on we went again.

The group continued on for five days moving bare-foot through the dense jungle, surviving only on the contents of their ration bag and help given from friendly Burmese villages along the way. At last they stumbled across Allied Forces and liberation. After exchanging their tattered clothes for new uniforms and a decent cooked meal, Leonard, Denis and the other men were flown out to India for hospitalisation, rest and recuperation. By mid-summer they were returned to their former units and presumably Leonard re-joined the King's at the Napier Barracks in Karachi, eventually he and the battalion were repatriated back to the UK.

In August 2014 I received this contact email via my website from Leonard's son Mike:

Good Morning

I have been looking for information on my father Leonard Coffin Army No. 5623161, when I came across your website. You have him as Lionel and not Leonard, so was hoping that you could change your record. I have some interesting documents of his and of course some photos that I could scan and upload if that would help with the broad picture.

Many thanks

Mike Coffin

As you can imagine I was very pleased to receive this contact from Mike and embarrassingly, only too pleased to correct my error in calling his father Lionel when mentioned on my website. In my defence, the reason for this mistake was the presence in Rangoon Jail of another prisoner named Lionel Coffin, an Amercian Airman who had been shot down over the city and imprisoned in the jail in December 1944. I duly sent over all the information and documents I possessed in relation to Leonard's story and his time in Burma and Mike kindly sent me the photographs shown throughout this article.

Mike also told me that:

I met Ron "Dinger" Bell (Indian Army) about 20 years ago and sitting in my parents' kitchen. I remember him embarrassing Dad by saying how Dad had saved his life on more than one occasion in the camp by giving him his food when Ron was ill, but also when they were "on the run". Apparently, Ron was just about to step on a booby trap when Dad spotted it and dragged him away. I can't remember many details but part of the trap was made from a tin can.

I also know that Dad kept a diary written on the back of postcards and photos that he had scrounged. He told us that he was up to about ninety cards at the time of the escape. The majority of these were traded with the villagers in exchange for food or if not traded given as thanks. He kept the first six cards as those photos were his own. At present, my sister is trying to decipher them, but the condition of the cards and his hand writing make for difficult reading. When she has finished I will send you a copy if you'd be interested.

I have found a piece of red cloth that had an interesting story attached to it. Apparently it was a badge he had to wear to show he had a job as a fly catcher whilst he was in the sick bay. To earn his food he needed to fill the jar each day with dead flies. I wondered whether you had come across this story before.

The story about the flies was known to me. According to Lieutenant Denis Gudgeon a former prisoner inside Rangoon Jail, a minimum of 30 dead flies per day was the requirement issued by the Japanese tenko officer for men on hospital, latrine or gardening duty. This rule was brought in after the cholera outbreak in the jail in June 1944.

To conclude this story, here are some details for two of the men mentioned as being part of Leonard Coffin and Denis Gavin's escape party from the Pegu march in April 1945.

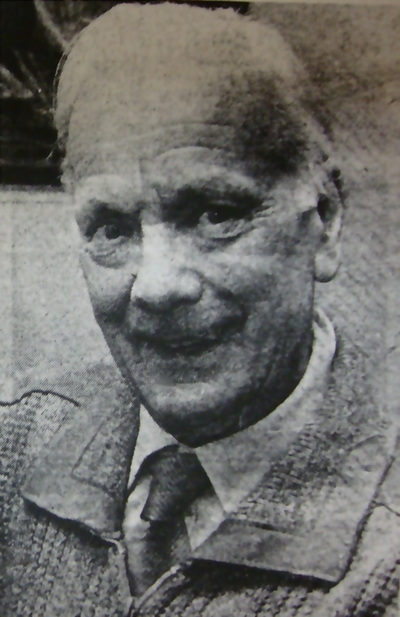

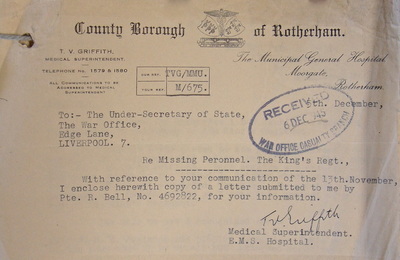

Pte. 4692822 Ronald 'Dinger' Bell, originally from Rotherham and had served on Operation Longcloth as part of the 142 Commando platoon in Chindit Column 1. He had originally been a member of the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry Regiment and had been based in India since before the war. On the 31st July 1942 Ron was transferred from the Bush Warfare School at Maymyo to the Chindit training camp at Saugor in India, here he was trained by Major Mike Calvert in the handling of explosives and the latest commando fighting methods.

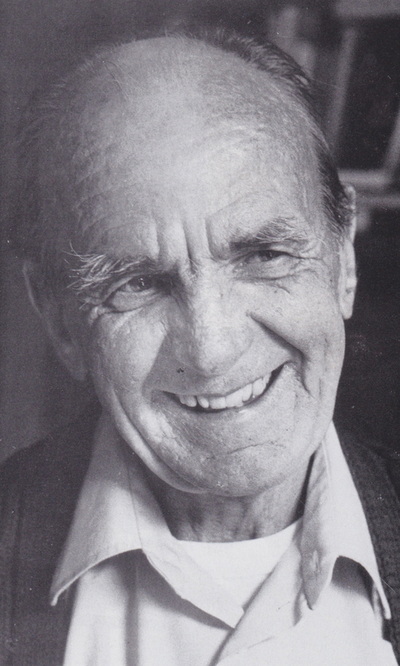

Lance Corporal 878620 William George McMurran from Shoreham in Sussex. William was originally a soldier with the Suffolk Regiment before being transferred to the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade in July 1942. He was also a Commando, serving alongside Dinger Bell in Column 1 on Operation Longcloth. William and the small dispersal group he was leading were captured on the 10th May 1943, just three miles short of the Chindwin River and the safety of Allied lines.

I would like to thank Mike Coffin for his help in bringing his father's remarkable story to these website pages. Seen below is one final gallery of images in relation to Leonard Coffin and the men he befriended during his time with the Chindits and as a prisoner of war. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

In his book 'Quiet Jungle, Angry Sea', Denis Gavin tells the story of the attempted escape from Singapore and later on in the book, his and Leonard's break for freedom on the Pegu march:

We were to march north to Pegu to get to the head of the Bay and then move east away from the war towards Siam. It was generally felt that a break must be made before we passed Pegu and got too far away from our own troops.

As the miles went by and nothing was heard of the Brigadier's plans, many of us became uneasy and wondered if his talk was not just a put-off to hold us together until it was too late to attempt escape. We knew he was capable of thinking himself justified in such a move to avoid deaths or hardship, but when he was tackled about his motives he produced a plan of escape just east of Pegu. This decided me and I determined that even if I went alone I was not going past Pegu with the column, and accordingly set about forming a gang. I dare not tackle the escape alone with my poor vision and my old comrades scattered.

Lissy and Dicky were sick in Rangoon, Tiny was in a different part of the column. I seized on my remaining friend, Titch Hudson. Physically I was less than half a man now, and although my mind was still clear I needed someone else to lean on. Titch and I soon got recruits as the legend of our adventures from Singapore was impressive and Len Coffin of the Kings, Dinger Bell and Bill McMurran, both of 17th Indian Infantry Division, joined us.

NB. Lissy, Dicky, Titch Hudson and Tiny were all part of the crew aboard Denis's escape boat from Singapore.

Titch got shifted on the column and we lost him, but the remainder of us kept together by volunteering to manhandle en route one of the bullock carts which held our stores. As the miles went by we systematically looted this bullock cart during each air raid and gradually filled a sack with rice, matches, candles, water bottles, peas, tea and sugar. These air raids were real shoot-ups by questing Spitfires and Hurricanes. They became so persistent that by the 26th we were pinned down in a copse and couldn't move from it during daylight.

Even here there was no respite, and the thicket was bombed time and again during the day. These raids were really a godsend to us as the Japanese and everyone else were pinned down in ditches and trenches and we were able to make unobserved visits to our vehicle for loot. It was decided to make a break during the first raid that night. But when we were startled into activity by a roll call we found that Pete Wilson, Lofty Eastgate and two other Australians, Ron Hadden and Harvey Besley, had already made their escape and we realised that now the Japanese would be on the alert. A council of war left us resolved to watch for the first opportunity, night or day, and we sat down to wait for the next raid.

It wasn't long before a batch of Spitfires were merrily shooting up and bombing our copse. With shaking hearts we gathered our gear and started to walk away. Three years previously I would have had the confidence of fighting manhood and there would have been excitement and zest in the adventure, but now I was sick and trembling, and ready to panic if we were spotted. We got almost to the edge of the copse when we saw the nearest Japanese sentry in his ditch between us and freedom, and we almost gave up there and then at the sight of him.

However, the thought of freedom in the next few minutes against that of captivity for the next few years was too much and I could not let one Japanese soldier stand in my way. Back we went to our resting comrades and managed to get an invaluable cook's knife, long and sharp, from one of the cooks and we stealthily made our way back to the sentry. I was going to go up to the sentry, who only I knew. If he challenged my right to be away from the centre of the copse I was going to make a plea of fear of the bombs until I could get close enough to him to plunge my knife into his heart.

But something had happened to me in prison and even when I was sitting down, with him lying beside me on his stomach, I could not bring myself to do it. I had gone soft in camp and was no longer a man, and could not even bring myself to hurt him. Besides I liked this bloke, as I had grown to like many of the Japanese. The situation was only saved by the man himself getting up and going on his patrol.

In a few moments my gang were with me and racing across the open paddy field to the jungle and freedom 200 yards away. The jungle swallowed us without sound, but we continued to run, wildly and hysterically, until we had to stop and lie panting. We stayed only until our breath returned and then we were off again always to the west, and our Allies, until at last the sun went down and we had to wait for the stars to appear and guide us. Dawn, and waiting for the sun gave us our first rest and then on again until the sun high in the sky had made west indistinguishable from east, north or south. Here we cooked our first meal and rested again until the waning sun gave us our direction and on we went again.

The group continued on for five days moving bare-foot through the dense jungle, surviving only on the contents of their ration bag and help given from friendly Burmese villages along the way. At last they stumbled across Allied Forces and liberation. After exchanging their tattered clothes for new uniforms and a decent cooked meal, Leonard, Denis and the other men were flown out to India for hospitalisation, rest and recuperation. By mid-summer they were returned to their former units and presumably Leonard re-joined the King's at the Napier Barracks in Karachi, eventually he and the battalion were repatriated back to the UK.

In August 2014 I received this contact email via my website from Leonard's son Mike:

Good Morning

I have been looking for information on my father Leonard Coffin Army No. 5623161, when I came across your website. You have him as Lionel and not Leonard, so was hoping that you could change your record. I have some interesting documents of his and of course some photos that I could scan and upload if that would help with the broad picture.

Many thanks

Mike Coffin

As you can imagine I was very pleased to receive this contact from Mike and embarrassingly, only too pleased to correct my error in calling his father Lionel when mentioned on my website. In my defence, the reason for this mistake was the presence in Rangoon Jail of another prisoner named Lionel Coffin, an Amercian Airman who had been shot down over the city and imprisoned in the jail in December 1944. I duly sent over all the information and documents I possessed in relation to Leonard's story and his time in Burma and Mike kindly sent me the photographs shown throughout this article.

Mike also told me that:

I met Ron "Dinger" Bell (Indian Army) about 20 years ago and sitting in my parents' kitchen. I remember him embarrassing Dad by saying how Dad had saved his life on more than one occasion in the camp by giving him his food when Ron was ill, but also when they were "on the run". Apparently, Ron was just about to step on a booby trap when Dad spotted it and dragged him away. I can't remember many details but part of the trap was made from a tin can.

I also know that Dad kept a diary written on the back of postcards and photos that he had scrounged. He told us that he was up to about ninety cards at the time of the escape. The majority of these were traded with the villagers in exchange for food or if not traded given as thanks. He kept the first six cards as those photos were his own. At present, my sister is trying to decipher them, but the condition of the cards and his hand writing make for difficult reading. When she has finished I will send you a copy if you'd be interested.

I have found a piece of red cloth that had an interesting story attached to it. Apparently it was a badge he had to wear to show he had a job as a fly catcher whilst he was in the sick bay. To earn his food he needed to fill the jar each day with dead flies. I wondered whether you had come across this story before.

The story about the flies was known to me. According to Lieutenant Denis Gudgeon a former prisoner inside Rangoon Jail, a minimum of 30 dead flies per day was the requirement issued by the Japanese tenko officer for men on hospital, latrine or gardening duty. This rule was brought in after the cholera outbreak in the jail in June 1944.

To conclude this story, here are some details for two of the men mentioned as being part of Leonard Coffin and Denis Gavin's escape party from the Pegu march in April 1945.

Pte. 4692822 Ronald 'Dinger' Bell, originally from Rotherham and had served on Operation Longcloth as part of the 142 Commando platoon in Chindit Column 1. He had originally been a member of the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry Regiment and had been based in India since before the war. On the 31st July 1942 Ron was transferred from the Bush Warfare School at Maymyo to the Chindit training camp at Saugor in India, here he was trained by Major Mike Calvert in the handling of explosives and the latest commando fighting methods.

Lance Corporal 878620 William George McMurran from Shoreham in Sussex. William was originally a soldier with the Suffolk Regiment before being transferred to the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade in July 1942. He was also a Commando, serving alongside Dinger Bell in Column 1 on Operation Longcloth. William and the small dispersal group he was leading were captured on the 10th May 1943, just three miles short of the Chindwin River and the safety of Allied lines.

I would like to thank Mike Coffin for his help in bringing his father's remarkable story to these website pages. Seen below is one final gallery of images in relation to Leonard Coffin and the men he befriended during his time with the Chindits and as a prisoner of war. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 31/05/2015.

As mentioned previously by Mike Coffin, his father had kept a handwritten diary of his time in Burma and as a prisoner of war, which he had scribbled down on the back of some ninety postcards. By keeping such a record, Leonard risked severe punishment from the Japanese prison guards should his diary be discovered. Very few memoirs survived the harsh conditions inside Rangoon Jail or the constant cell room searches performed regularly by the Japanese guards.

Sadly, Leonard traded the majority of these postcards with Burmese villagers during his time on the Pegu march and after he and his comrades had absconded from the main body of prisoners in late April 1945. He used them to pay for food and as a way of saying thank you to the locals for their assistance as he made his way back to Allied held lines. It is a great shame to have lost what would have been a fascinating and valuable resource to any interested researcher, however, at the time, food and success in reaching safety were far more important.

I am pleased to say that six postcards did survive, these half-dozen cards recounted the period when Leonard and his dispersal group found themselves aside the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River during the month of April 1943. Mike Coffin told me that Leonard had kept hold of these particular postcards for sentimental reasons, as they were in fact photographs of his family. The translation of the postcards seen below is the work of Mike Coffin and his sister, Jen. I have added some information in brackets and in the form of annotated notes at the end of each page or card. It is remarkable how Leonard's short diary matches up with the memoir of Lieutenant Wilding for the same period and shown earlier in this story.

Transcription of Leonard Coffin’s postcards, for the period, approximately 30th March through 19th April 1943.

Postcard 1:

Last SDA (1) with the Brigade, 30th March; dispersal same day. X? Chon (2), straightened out 23-3 (3) in party, up to Schwali (Shweli River) two days, built raft to attempt crossing on the night of 1st/2nd April, failed.

Marched south 2 miles, rested one day, Burmese three (4) recce for boats, no good, took us two days to get back to Chon, deep pool, rested one whole day and then marched on within 5 miles of the Waddi (Irrawaddy River).

Burmese went forward to locate boats, did not come back that night, we had no water, things looked black. Two came back next night with bad news; they had met opposition in the village, the gemadar (Jemadar) (5) getting shot.

Notes for postcard 1:

1. I believe SDA refers to Supply Drop Area, that is the place chosen to receive an air supply drop from Rear Base.

2. This refers to the word chaung, meaning a dry or semi-dry small riverbed, pronounced chong in Burmese. In this particular case I think Leonard is referring to the Nalo Chaung in which the dispersal group spent many unhappy hours in April 1943.

3. 23-3, I believe refers to the breakdown of personnel in the dispersal party and not a date. Twenty-three other ranks and three British officers.

4. Refers to the three Burma Rifles with the party: Jemadar Moudie and Riflemen Tunnion and Orlando.

5. A Jemadar was a rank in the Indian Army, equivalent to a junior Lieutenant.

Postcard 2:

Back to Chon, food getting low. Went back to last SDA where we found 9 tins of rations, this helped a lot, moved back 500 yards where we decide to march south, we lost Simmons (1) the next morning which messed the plans up a bit (picked up Topper in bad condition). We then moved a couple of miles down the Chon for safety reasons and about 1000 yards in. (2)

Stayed here for three days making one move a matter of 500 yards, did pretty well for rations (Mills incident). (3) We then started our trek south, luck had been with us so far it seemed.

Notes for postcard 2:

1. This refers to Pte. Simmons (Simons) who was lost whilst out searching for water.

2. This manoeuvre was standard Chindit practice for taking up a bivouac or camp at the end of each marching period.

3. Lance Corporal Cecil Mills was reportedly wounded several times during this period; perhaps this refers to one of these occasions.

Postcard 3:

We were all reasonably strong; plenty of food and our spirits were very high. It took us four days to get to our destination, which after a terrific climb turned out to be the wrong crest. However, we stayed here for a couple of days while Mr. H.+ W. (1) went to the right crest.

We also made and tested the ‘Sillick’ (2) float here and on the third day taking our bamboo, we journeyed farther up the Chon and then met Mr. H + W, who had by then found the correct crest.

Notes for postcard 3:

1. Mr. Hosegood and Mr. Wilding, the two British officers in charge of the dispersal group.

2. Refers to Corporal Clifford Sillick a commando with the group, seemingly possessing raft-building skills.

Postcard 4:

By this time food was getting low and we managed to get some fish and a turtle from the Chon. (Amos (1) and Topper (2) getting some rice from a lone hut, as it seemed reasonably safe).

Eventually we were ready for it and at about 7 o’clock just after sunset we started our descent down towards the Waddi (Irrawaddy). We knew the jungle was pretty thick, as we had sent a patrol out the day previous, but with the raft it was more than thick, and we found it bloody hard to do more than a couple of miles carrying the bamboos and we bedded down about 4 o’clock, which I think was the best thing as everybody was dead beat.

Notes for postcard 4:

1. Refers to Signalman Victor Foch Amos.

2. Although ‘Topper’ is mentioned twice in the narrative, I have no knowledge as to whom this refers. However, ‘Topper’ seems to be a popular nickname during WW2 for someone with the surname Brown.

Postcard 5:

We were aroused pretty early from our sleep, one of the party had heard voices and also bullock carts, which told us we were very near a fair sized track, so up we got and on we trod.

We finished up in the region of a natural canal, which came in very handy for cooking and washing. We stayed on this canal for 4 days, making three different camps. Also made 3 journeys to the village, we asked for volunteers and I was never so disgusted with so called Englishmen. (1)

Notes for postcard 5:

1. It is thought that Leonard was referring to the lack of volunteers from the British ranks at this juncture and how this had annoyed him.

Postcard 6:

Was on one of these expeditions that I managed to lose my way, spent half my time or the night in the jungle and the other half in the village, made up for it though as I managed to catch a chicken and I then had my finest breakfast since entering Burma, which seemed to even things up a bit.

We then decided that approaching the Waddi (Irrawaddy) from here was an impossibility. So we dumped our rafts and journeyed back the way we came up to the top of the hill and down to the Chon, and it was here that we decided to march north and hide away some place in the Kachin Hills, living in or very near a village. So off we went again.

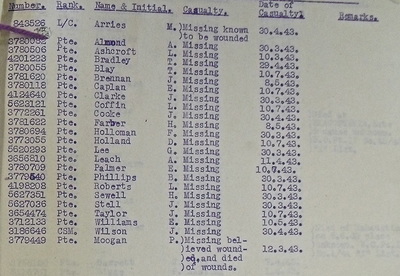

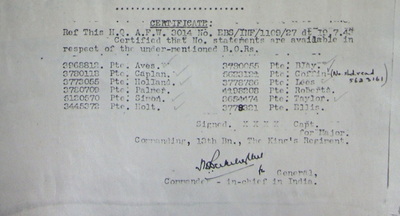

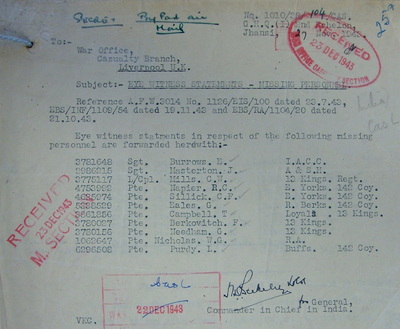

This is where Leonard's short diary ends; barely ten days later he found himself a prisoner in Japanese hands. Seen below are some images in relation to this story, including a list of men stated as missing in action during Operation Longcloth and who I strongly believe formed part of the dispersal party led by Captain Hosegood and Lieutenant Wilding. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

As mentioned previously by Mike Coffin, his father had kept a handwritten diary of his time in Burma and as a prisoner of war, which he had scribbled down on the back of some ninety postcards. By keeping such a record, Leonard risked severe punishment from the Japanese prison guards should his diary be discovered. Very few memoirs survived the harsh conditions inside Rangoon Jail or the constant cell room searches performed regularly by the Japanese guards.

Sadly, Leonard traded the majority of these postcards with Burmese villagers during his time on the Pegu march and after he and his comrades had absconded from the main body of prisoners in late April 1945. He used them to pay for food and as a way of saying thank you to the locals for their assistance as he made his way back to Allied held lines. It is a great shame to have lost what would have been a fascinating and valuable resource to any interested researcher, however, at the time, food and success in reaching safety were far more important.

I am pleased to say that six postcards did survive, these half-dozen cards recounted the period when Leonard and his dispersal group found themselves aside the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River during the month of April 1943. Mike Coffin told me that Leonard had kept hold of these particular postcards for sentimental reasons, as they were in fact photographs of his family. The translation of the postcards seen below is the work of Mike Coffin and his sister, Jen. I have added some information in brackets and in the form of annotated notes at the end of each page or card. It is remarkable how Leonard's short diary matches up with the memoir of Lieutenant Wilding for the same period and shown earlier in this story.

Transcription of Leonard Coffin’s postcards, for the period, approximately 30th March through 19th April 1943.

Postcard 1:

Last SDA (1) with the Brigade, 30th March; dispersal same day. X? Chon (2), straightened out 23-3 (3) in party, up to Schwali (Shweli River) two days, built raft to attempt crossing on the night of 1st/2nd April, failed.

Marched south 2 miles, rested one day, Burmese three (4) recce for boats, no good, took us two days to get back to Chon, deep pool, rested one whole day and then marched on within 5 miles of the Waddi (Irrawaddy River).

Burmese went forward to locate boats, did not come back that night, we had no water, things looked black. Two came back next night with bad news; they had met opposition in the village, the gemadar (Jemadar) (5) getting shot.

Notes for postcard 1:

1. I believe SDA refers to Supply Drop Area, that is the place chosen to receive an air supply drop from Rear Base.

2. This refers to the word chaung, meaning a dry or semi-dry small riverbed, pronounced chong in Burmese. In this particular case I think Leonard is referring to the Nalo Chaung in which the dispersal group spent many unhappy hours in April 1943.

3. 23-3, I believe refers to the breakdown of personnel in the dispersal party and not a date. Twenty-three other ranks and three British officers.

4. Refers to the three Burma Rifles with the party: Jemadar Moudie and Riflemen Tunnion and Orlando.

5. A Jemadar was a rank in the Indian Army, equivalent to a junior Lieutenant.

Postcard 2:

Back to Chon, food getting low. Went back to last SDA where we found 9 tins of rations, this helped a lot, moved back 500 yards where we decide to march south, we lost Simmons (1) the next morning which messed the plans up a bit (picked up Topper in bad condition). We then moved a couple of miles down the Chon for safety reasons and about 1000 yards in. (2)

Stayed here for three days making one move a matter of 500 yards, did pretty well for rations (Mills incident). (3) We then started our trek south, luck had been with us so far it seemed.

Notes for postcard 2:

1. This refers to Pte. Simmons (Simons) who was lost whilst out searching for water.

2. This manoeuvre was standard Chindit practice for taking up a bivouac or camp at the end of each marching period.

3. Lance Corporal Cecil Mills was reportedly wounded several times during this period; perhaps this refers to one of these occasions.

Postcard 3:

We were all reasonably strong; plenty of food and our spirits were very high. It took us four days to get to our destination, which after a terrific climb turned out to be the wrong crest. However, we stayed here for a couple of days while Mr. H.+ W. (1) went to the right crest.

We also made and tested the ‘Sillick’ (2) float here and on the third day taking our bamboo, we journeyed farther up the Chon and then met Mr. H + W, who had by then found the correct crest.

Notes for postcard 3:

1. Mr. Hosegood and Mr. Wilding, the two British officers in charge of the dispersal group.

2. Refers to Corporal Clifford Sillick a commando with the group, seemingly possessing raft-building skills.

Postcard 4:

By this time food was getting low and we managed to get some fish and a turtle from the Chon. (Amos (1) and Topper (2) getting some rice from a lone hut, as it seemed reasonably safe).

Eventually we were ready for it and at about 7 o’clock just after sunset we started our descent down towards the Waddi (Irrawaddy). We knew the jungle was pretty thick, as we had sent a patrol out the day previous, but with the raft it was more than thick, and we found it bloody hard to do more than a couple of miles carrying the bamboos and we bedded down about 4 o’clock, which I think was the best thing as everybody was dead beat.

Notes for postcard 4:

1. Refers to Signalman Victor Foch Amos.

2. Although ‘Topper’ is mentioned twice in the narrative, I have no knowledge as to whom this refers. However, ‘Topper’ seems to be a popular nickname during WW2 for someone with the surname Brown.

Postcard 5:

We were aroused pretty early from our sleep, one of the party had heard voices and also bullock carts, which told us we were very near a fair sized track, so up we got and on we trod.

We finished up in the region of a natural canal, which came in very handy for cooking and washing. We stayed on this canal for 4 days, making three different camps. Also made 3 journeys to the village, we asked for volunteers and I was never so disgusted with so called Englishmen. (1)

Notes for postcard 5:

1. It is thought that Leonard was referring to the lack of volunteers from the British ranks at this juncture and how this had annoyed him.

Postcard 6:

Was on one of these expeditions that I managed to lose my way, spent half my time or the night in the jungle and the other half in the village, made up for it though as I managed to catch a chicken and I then had my finest breakfast since entering Burma, which seemed to even things up a bit.

We then decided that approaching the Waddi (Irrawaddy) from here was an impossibility. So we dumped our rafts and journeyed back the way we came up to the top of the hill and down to the Chon, and it was here that we decided to march north and hide away some place in the Kachin Hills, living in or very near a village. So off we went again.

This is where Leonard's short diary ends; barely ten days later he found himself a prisoner in Japanese hands. Seen below are some images in relation to this story, including a list of men stated as missing in action during Operation Longcloth and who I strongly believe formed part of the dispersal party led by Captain Hosegood and Lieutenant Wilding. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Here is what I know about some of the men mentioned in Leonard's diary and some of the other soldiers confirmed as members of his dispersal group in April 1943.

Pte. Simons (sometimes referred to as Simmons). This man's identity has proved somewhat of a mystery. He is mentioned by both Leonard and Lieutenant Wilding as having gone missing whilst out searching for fresh water for the group in early April. He turned up again at the Maymyo POW Camp, but then drops off the radar once more. No one with the surname of Simons was held as a prisoner inside Rangoon Jail or was listed as a casualty for Operation Longcloth. There was a man named William Symons formerly with 7 Column who perished as a POW in early June 1943, but it is difficult to see how he could have joined up with Captain Hosegood's dispersal team at the Irrawaddy although his dispersal party, led by Lieutenant Rex Walker was in the vicinity on the 10th April.

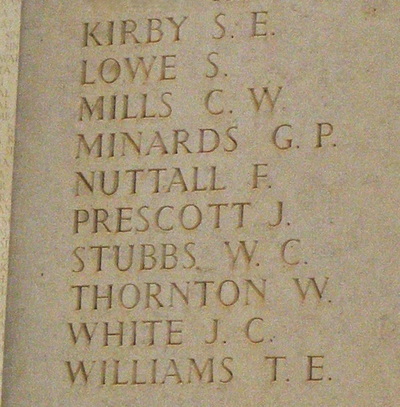

Lance Corporal 3775117 Cecil William Mills. This soldier was from Chester and originally with the 14th Battalion of the King's Regiment before joining Chindit training in the summer of 1942. He was part of the 142 Commando platoon and had been attached to the Signals section of Brigade Head Quarters during Operation Longcloth. Cecil was captured alongside Captain Hosegood at the Mynyaung Chaung in early May 1943 and is listed as being killed on the 12th May. As mentioned in Leonard Coffin's diary, Cecil had been wounded even before he became a prisoner of war, and it is suggested from witness statements given by eventual survivors of Operation Longcloth, that he was murdered by the Japanese because he was too ill or disabled to travel with the rest of the group. One report states that the Japanese told another Chindit that Cecil had been 'taken to hospital.' He was never seen or heard of again.

Here are Cecil Mills' CWGC details: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2517651/MILLS,%20CECIL%20WILLIAM

Signalman 3775126 Victor Foch Amos, was the son of William and Elizabeth Amos from Ellesmere Port in Cheshire. He was a last minute addition to Wingate's Brigade HQ in January 1943, having previously served on covert missions in the Yunnan Province of China. Victor survived his initial period as a prisoner of war, but sadly perished inside Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on the 1st February 1944. His POW number was 550 and he was originally buried at the English Cantonment Cemetery, located close to the Royal Lakes in the eastern sector of the city. His grave reference for the Cantonment Cemetery was recorded as number 148.

Here are Victor Amos' CWGC details: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2259656/AMOS,%20VICTOR%20FOCH

Pte. 4625974 Clifford W. Sillick. This man originally enlisted into the East Yorkshire Regiment at the beginning of WW2, before being posted to the 142 Commando section of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade at the Chindit training camp of Saugor on the 30th September 1942. Clifford was attached to Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth and was allocated to Captain Hosegood's dispersal group on the 30th March 1943, where as we have already heard, he was responsible for the construction of the rafts built to ferry the group across the Irrawaddy River. Clifford was reportedly an eye-witness to the death of Corporal Purdy on the 29th April, when Purdy and Lieutenant Gordon's party attempted to cross the river in a country boat. Pte. Sillick was captured on the 2nd May 1943, he survived his time as a prisoner of war and was liberated on the 29th April 1945 at the Burmese village of Waw close to the town of Pegu.

Pte. 3780694 Frederick Charles Holloman. Fred was born in the Wiltshire town of Salisbury, but grew up in the East End of London where his family ran a succession of public houses. Fred Holloman travelled to India with the original 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment aboard the troopship 'Oronsay' in December 1941. He was attached to Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters where he performed the role of muleteer, looking after his mule, Betty, who carried the Brigade wireless set. After he was captured with Lieutenant Wilding's group on the 2nd May 1943, Fred was given the POW number of 350 inside Rangoon Jail. Fred survived his time in Rangoon and was also liberated on the 29th April near the Burmese town of Pegu.

Lance Corporal 6103385 James Arthur Willis. James was the son of William and Mary Willis and the husband of Isobel Willis from Slough in Berkshire. He was also a last minute reinforcement to 77th Brigade and had also been on active service in China prior to joining Wingate's Brigade HQ in January 1943. James was the Head Quarters wireless operator on Operation Longcloth and was allocated to the dispersal group led by Captain Hosegood and Lieutenant Wilding on the 30th March.

By the time of his capture on the 2nd May, James was the only Chindit in the dispersal group still in possession of a serviceable rifle. No rifle oil had been dropped to the Chindits during their time behind enemy lines, but James with no little ingenuity had used his allocation of mosquito repellent cream to keep his weapon in good order. Alas, one rifle was never going to be enough to fend off the advancing enemy patrol and eventually Wilding decided to surrender.

James Willis died in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on the 11th September 1943 and was buried alongside his comrades at the English Cantonment Cemetery. His POW number whilst inside Rangoon was 557 and his grave reference in the Cantonment Cemetery was recorded as 73. After the war was over, all the POW burials from Rangoon Jail were removed from their original resting place and re-interred at the newly constructed Rangoon War Cemetery.

To view James' CWGC details, please click on the following link:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2261418/WILLIS,%20JAMES%20ARTHUR

Pte. 3780156 George Needham was the son of George and Alice Needham and the husband of Alice Needham from Leigh in Lancashire. Originally a cook in the 13th Battalion, George moved across to 142 Commando in the summer of 1942 and was attached to Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters. Pte. Needham was captured with Captain Hosegood at the Mynyaung Chaung in early May 1943. From witness statements given by survivors of Operation Longcloth, it would appear that George suffered a similar fate to that of Cecil Mills.

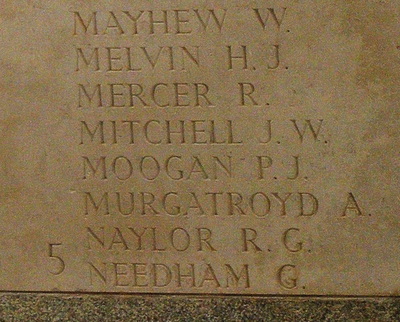

Pte. James Dixon, also of 142 Commando stated that: I think that he was shot by the Japanese because no medical facilities were available when they moved us on. George died on the 12th May. His grave was never recovered after the war and so he is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial along with Cecil Mills.

To view George's CWGC details, please click on the following link:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2520148/NEEDHAM,%20GEORGE

For information about Corporal Leslie Albert Purdy, Signalman Herbert Michael Belchier and Jemadar Moudie of the Burma Rifles, please follow the link to Lieutenant Gordon's story here: Lieutenant Gordon

I believe that the men mentioned below were also part of Captain Hosegood's dispersal party in April 1943:

Pte. 5338529 George Arthur Eales. Formerly of the Royal Berkshire Regiment, George became a member of the Brigade Head Quarters Commando platoon in September 1942. Born on the 27th August 1919, he was the son of Henry Michael and Amy Elizabeth Eales from Cricklewood in London. Captured on the 11th May 1943, George sadly perished from the effects of beri beri inside Rangoon Jail on the 26th June 1944. His POW number was 366 and his grave reference in the English Cantonment Cemetery was recorded as 189.

To view George's CWGC details, please click on the following link:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2259914/EALES,%20GEORGE%20ARTHUR

Pte. 4467646 James Dixon. Born on the 2nd December 1910 and formerly of the Durham Light Infantry, James, also a Commando, was posted to Captain Hosegood's Intelligence section in Wingate's Brigade HQ. He was captured on the 11th May 1943 at the Mynyaung Chaung and spent just under two years inside Rangoon Jail with the POW number 369. James was liberated in late April 1945 at Pegu.

Pte. 3861856 Timothy Campbell. Born on the 27th December 1912 and formerly of the Loyal Regiment, Pte. Campbell was part of Captain Hosegood's Intelligence section on Operation Longcloth. In actual fact Tim, originally from Stockport in Lancashire was Hosegood's batman and served in this capacity throughout the expedition in 1943. He was captured, presumably at the Mynyaung Chaung on the 2nd May and spent just under two years inside Rangoon Jail with the POW number 354. Pte. Campbell had the very sad duty in attending Captain Hosegood's funeral on the 9th April 1945 at the English Cantonment Cemetery. Timothy Campbell was liberated along with many of his Chindit comrades just three weeks later near the Burmese town of Pegu.

For more information about Captain Graham Hosegood, including a letter to Hosegood's parents from Pte. Campbell, please click on the following link: Graham Hosegood

To conclude this update, seen below are several images in relation to some of the men mentioned above. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Pte. Simons (sometimes referred to as Simmons). This man's identity has proved somewhat of a mystery. He is mentioned by both Leonard and Lieutenant Wilding as having gone missing whilst out searching for fresh water for the group in early April. He turned up again at the Maymyo POW Camp, but then drops off the radar once more. No one with the surname of Simons was held as a prisoner inside Rangoon Jail or was listed as a casualty for Operation Longcloth. There was a man named William Symons formerly with 7 Column who perished as a POW in early June 1943, but it is difficult to see how he could have joined up with Captain Hosegood's dispersal team at the Irrawaddy although his dispersal party, led by Lieutenant Rex Walker was in the vicinity on the 10th April.

Lance Corporal 3775117 Cecil William Mills. This soldier was from Chester and originally with the 14th Battalion of the King's Regiment before joining Chindit training in the summer of 1942. He was part of the 142 Commando platoon and had been attached to the Signals section of Brigade Head Quarters during Operation Longcloth. Cecil was captured alongside Captain Hosegood at the Mynyaung Chaung in early May 1943 and is listed as being killed on the 12th May. As mentioned in Leonard Coffin's diary, Cecil had been wounded even before he became a prisoner of war, and it is suggested from witness statements given by eventual survivors of Operation Longcloth, that he was murdered by the Japanese because he was too ill or disabled to travel with the rest of the group. One report states that the Japanese told another Chindit that Cecil had been 'taken to hospital.' He was never seen or heard of again.

Here are Cecil Mills' CWGC details: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2517651/MILLS,%20CECIL%20WILLIAM

Signalman 3775126 Victor Foch Amos, was the son of William and Elizabeth Amos from Ellesmere Port in Cheshire. He was a last minute addition to Wingate's Brigade HQ in January 1943, having previously served on covert missions in the Yunnan Province of China. Victor survived his initial period as a prisoner of war, but sadly perished inside Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on the 1st February 1944. His POW number was 550 and he was originally buried at the English Cantonment Cemetery, located close to the Royal Lakes in the eastern sector of the city. His grave reference for the Cantonment Cemetery was recorded as number 148.

Here are Victor Amos' CWGC details: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2259656/AMOS,%20VICTOR%20FOCH

Pte. 4625974 Clifford W. Sillick. This man originally enlisted into the East Yorkshire Regiment at the beginning of WW2, before being posted to the 142 Commando section of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade at the Chindit training camp of Saugor on the 30th September 1942. Clifford was attached to Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth and was allocated to Captain Hosegood's dispersal group on the 30th March 1943, where as we have already heard, he was responsible for the construction of the rafts built to ferry the group across the Irrawaddy River. Clifford was reportedly an eye-witness to the death of Corporal Purdy on the 29th April, when Purdy and Lieutenant Gordon's party attempted to cross the river in a country boat. Pte. Sillick was captured on the 2nd May 1943, he survived his time as a prisoner of war and was liberated on the 29th April 1945 at the Burmese village of Waw close to the town of Pegu.

Pte. 3780694 Frederick Charles Holloman. Fred was born in the Wiltshire town of Salisbury, but grew up in the East End of London where his family ran a succession of public houses. Fred Holloman travelled to India with the original 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment aboard the troopship 'Oronsay' in December 1941. He was attached to Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters where he performed the role of muleteer, looking after his mule, Betty, who carried the Brigade wireless set. After he was captured with Lieutenant Wilding's group on the 2nd May 1943, Fred was given the POW number of 350 inside Rangoon Jail. Fred survived his time in Rangoon and was also liberated on the 29th April near the Burmese town of Pegu.

Lance Corporal 6103385 James Arthur Willis. James was the son of William and Mary Willis and the husband of Isobel Willis from Slough in Berkshire. He was also a last minute reinforcement to 77th Brigade and had also been on active service in China prior to joining Wingate's Brigade HQ in January 1943. James was the Head Quarters wireless operator on Operation Longcloth and was allocated to the dispersal group led by Captain Hosegood and Lieutenant Wilding on the 30th March.

By the time of his capture on the 2nd May, James was the only Chindit in the dispersal group still in possession of a serviceable rifle. No rifle oil had been dropped to the Chindits during their time behind enemy lines, but James with no little ingenuity had used his allocation of mosquito repellent cream to keep his weapon in good order. Alas, one rifle was never going to be enough to fend off the advancing enemy patrol and eventually Wilding decided to surrender.

James Willis died in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on the 11th September 1943 and was buried alongside his comrades at the English Cantonment Cemetery. His POW number whilst inside Rangoon was 557 and his grave reference in the Cantonment Cemetery was recorded as 73. After the war was over, all the POW burials from Rangoon Jail were removed from their original resting place and re-interred at the newly constructed Rangoon War Cemetery.

To view James' CWGC details, please click on the following link:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2261418/WILLIS,%20JAMES%20ARTHUR

Pte. 3780156 George Needham was the son of George and Alice Needham and the husband of Alice Needham from Leigh in Lancashire. Originally a cook in the 13th Battalion, George moved across to 142 Commando in the summer of 1942 and was attached to Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters. Pte. Needham was captured with Captain Hosegood at the Mynyaung Chaung in early May 1943. From witness statements given by survivors of Operation Longcloth, it would appear that George suffered a similar fate to that of Cecil Mills.

Pte. James Dixon, also of 142 Commando stated that: I think that he was shot by the Japanese because no medical facilities were available when they moved us on. George died on the 12th May. His grave was never recovered after the war and so he is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial along with Cecil Mills.

To view George's CWGC details, please click on the following link:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2520148/NEEDHAM,%20GEORGE

For information about Corporal Leslie Albert Purdy, Signalman Herbert Michael Belchier and Jemadar Moudie of the Burma Rifles, please follow the link to Lieutenant Gordon's story here: Lieutenant Gordon

I believe that the men mentioned below were also part of Captain Hosegood's dispersal party in April 1943:

Pte. 5338529 George Arthur Eales. Formerly of the Royal Berkshire Regiment, George became a member of the Brigade Head Quarters Commando platoon in September 1942. Born on the 27th August 1919, he was the son of Henry Michael and Amy Elizabeth Eales from Cricklewood in London. Captured on the 11th May 1943, George sadly perished from the effects of beri beri inside Rangoon Jail on the 26th June 1944. His POW number was 366 and his grave reference in the English Cantonment Cemetery was recorded as 189.

To view George's CWGC details, please click on the following link:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2259914/EALES,%20GEORGE%20ARTHUR

Pte. 4467646 James Dixon. Born on the 2nd December 1910 and formerly of the Durham Light Infantry, James, also a Commando, was posted to Captain Hosegood's Intelligence section in Wingate's Brigade HQ. He was captured on the 11th May 1943 at the Mynyaung Chaung and spent just under two years inside Rangoon Jail with the POW number 369. James was liberated in late April 1945 at Pegu.

Pte. 3861856 Timothy Campbell. Born on the 27th December 1912 and formerly of the Loyal Regiment, Pte. Campbell was part of Captain Hosegood's Intelligence section on Operation Longcloth. In actual fact Tim, originally from Stockport in Lancashire was Hosegood's batman and served in this capacity throughout the expedition in 1943. He was captured, presumably at the Mynyaung Chaung on the 2nd May and spent just under two years inside Rangoon Jail with the POW number 354. Pte. Campbell had the very sad duty in attending Captain Hosegood's funeral on the 9th April 1945 at the English Cantonment Cemetery. Timothy Campbell was liberated along with many of his Chindit comrades just three weeks later near the Burmese town of Pegu.

For more information about Captain Graham Hosegood, including a letter to Hosegood's parents from Pte. Campbell, please click on the following link: Graham Hosegood

To conclude this update, seen below are several images in relation to some of the men mentioned above. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, May 2015.