Baby Bios

The following pages are devoted to the men of whom some detail is known in regard to their time and fate on Operation Longcloth, but not enough to form the basis of a more comprehensive biography. These short write-ups were inspired mostly on receiving a photograph of the man in question, or some firm detail from a family member or fellow researcher.

Pictured to the left is a uniform flash insignia as worn by the Chindits in 1943/44. The name Chindit was a mispronunciation of the Burmese word Chinthe (the mythical creature that stands guard outside Burmese pagodas). It is said that Captain Aung Thin of the Burma Rifles was the originator of the name, suggesting that the half griffin, half lion creature symbolised the nature of the Chindits task in Burma that year (1943). He felt the aggressive approach of the columns was represented by the lion, whilst the strength of the force was kept up from their air supply, represented by the griffin. Of course the men of Operation Longcloth knew nothing of this nickname until after their return to India in mid-1943, where many enjoyed reading about their own exploits on the expedition in the world's press.

Pictured to the left is a uniform flash insignia as worn by the Chindits in 1943/44. The name Chindit was a mispronunciation of the Burmese word Chinthe (the mythical creature that stands guard outside Burmese pagodas). It is said that Captain Aung Thin of the Burma Rifles was the originator of the name, suggesting that the half griffin, half lion creature symbolised the nature of the Chindits task in Burma that year (1943). He felt the aggressive approach of the columns was represented by the lion, whilst the strength of the force was kept up from their air supply, represented by the griffin. Of course the men of Operation Longcloth knew nothing of this nickname until after their return to India in mid-1943, where many enjoyed reading about their own exploits on the expedition in the world's press.

Signalman Eric Rostance

Eric Rostance formed part of the signals group for column 8 on Operation Longcloth. Around the beginning of April that year he became separated from the main body of the column, whilst out looking for tinder and firewood. The column were preparing to attempt to cross the Shweli River and had been experiencing very lean and difficult times, as the Japanese began to close the net on a large concentration of Wingate's force.

Thanks to some great help from Phil Jennett (a researcher of WW2 casualties from the Widnes area), I can now present a photograph of Eric, as seen to the right, and below a local newspaper announcement reporting Eric Rostance as missing in action:

Widnes Weekly News Friday August 13th 1943

REPORTED MISSING

Widnes Man’s Fate

Mrs. M. C. Rostance, of 19 Farnworth Street, Widnes, has received word that her son, Signalman Eric Rostance, is reported missing. He is 30 years of age, a native of Widnes, and was educated at Farnworth C.of E. School, before joining the Forces on June 27th 1940. He worked at Penketh Tannery. He was keen on sport, and was a familiar figure on the 'Ring-o-Bells' bowling greens, and a popular member of Derby Road Methodist Church and Farnworth A.F.C. He was attached to the India Command. His two brothers are also in the Services, Reginald Rostance and Vincent Rostance, and also a brother-in-law, William Rafferty.

Eric Rostance formed part of the signals group for column 8 on Operation Longcloth. Around the beginning of April that year he became separated from the main body of the column, whilst out looking for tinder and firewood. The column were preparing to attempt to cross the Shweli River and had been experiencing very lean and difficult times, as the Japanese began to close the net on a large concentration of Wingate's force.

Thanks to some great help from Phil Jennett (a researcher of WW2 casualties from the Widnes area), I can now present a photograph of Eric, as seen to the right, and below a local newspaper announcement reporting Eric Rostance as missing in action:

Widnes Weekly News Friday August 13th 1943

REPORTED MISSING

Widnes Man’s Fate

Mrs. M. C. Rostance, of 19 Farnworth Street, Widnes, has received word that her son, Signalman Eric Rostance, is reported missing. He is 30 years of age, a native of Widnes, and was educated at Farnworth C.of E. School, before joining the Forces on June 27th 1940. He worked at Penketh Tannery. He was keen on sport, and was a familiar figure on the 'Ring-o-Bells' bowling greens, and a popular member of Derby Road Methodist Church and Farnworth A.F.C. He was attached to the India Command. His two brothers are also in the Services, Reginald Rostance and Vincent Rostance, and also a brother-in-law, William Rafferty.

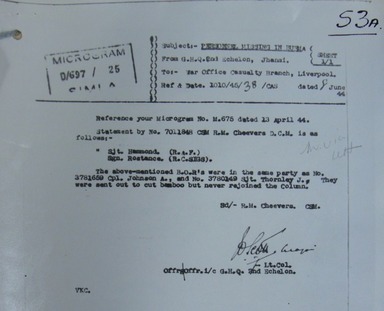

In actual fact Eric and another three men had gone out to gather firewood, acting on the orders of CSM Richard Cheevers. The group must have become lost and wandered around for a time trying to re-join the main body of column 8. Seen to the left (please click on the image to enlarge) is a report as given by CSM Cheevers on his return to India, outlining the details of the missing men, including Eric and a RAF Sergeant named David Glynn Hammond.

On another similar report, Cheevers names Corporal A. Johnson and Sergeant J. Thornley as the other two men involved in the firewood party. Cheevers gave this simple statement on the report: On the 1st April I was ordered by my column commander (Major Scott) to send out a party to cut bamboo, the four missing men were detailed.

All four men were captured in 1943 and eventually ended up in Rangoon Jail, where sadly Sgt. John Thornley and Eric died, leaving Hammond and Corporal Johnson to survive two years of incarceration before liberation in May 1945. Eric Rostance was given the POW number 456 in Rangoon Jail, but, up to now no other documents exist giving further details of his time as a prisoner of war.

On the 27th September 1943 Eric died a POW in Rangoon Jail, here is a link to the CWGC showing his casualty details:

www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2261157/eric-rostance/

Finally, here is a photograph of Eric's grave memorial as found in Rangoon War Cemetery in Burma.

On another similar report, Cheevers names Corporal A. Johnson and Sergeant J. Thornley as the other two men involved in the firewood party. Cheevers gave this simple statement on the report: On the 1st April I was ordered by my column commander (Major Scott) to send out a party to cut bamboo, the four missing men were detailed.

All four men were captured in 1943 and eventually ended up in Rangoon Jail, where sadly Sgt. John Thornley and Eric died, leaving Hammond and Corporal Johnson to survive two years of incarceration before liberation in May 1945. Eric Rostance was given the POW number 456 in Rangoon Jail, but, up to now no other documents exist giving further details of his time as a prisoner of war.

On the 27th September 1943 Eric died a POW in Rangoon Jail, here is a link to the CWGC showing his casualty details:

www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2261157/eric-rostance/

Finally, here is a photograph of Eric's grave memorial as found in Rangoon War Cemetery in Burma.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and Phil Jennett 2012.

Signalman Jack White

Signalman Jack White

One of the first family appeals for information I ever saw was made by Steve Wells on the Burma Star website concerning his Great Uncle Signalman Jack White. As with so many of these type of appeals the contact email was no longer valid and I have never been able to catch up with Steve.

Here is what he wrote about Jack White:

Dear Sir.

I am hoping you can give me some information about a great uncle of mine who served with the 77th Infantry Brigade in Burma. He was Signalman Jack White. He is mentioned in Bernard Ferguson's book about the Chindits. He was captured by the Japanese and died in Rangoon prison. I believe he was buried in Myanmar War Cemetery. Would this be Taukkyan War Cemetery by any chance?

I was also wondering if he was awarded the Burma Star when he was alive? If not, was it, or is it awarded posthumously. Any information you can give me would be so much appreciated. I am so proud of a man I of course did not know but who is remembered by my father as "his favorite uncle". If there is anyone who remembers Jack, I would be thrilled to hear from them. Thank you so very much.

One of the first family appeals for information I ever saw was made by Steve Wells on the Burma Star website concerning his Great Uncle Signalman Jack White. As with so many of these type of appeals the contact email was no longer valid and I have never been able to catch up with Steve.

Here is what he wrote about Jack White:

Dear Sir.

I am hoping you can give me some information about a great uncle of mine who served with the 77th Infantry Brigade in Burma. He was Signalman Jack White. He is mentioned in Bernard Ferguson's book about the Chindits. He was captured by the Japanese and died in Rangoon prison. I believe he was buried in Myanmar War Cemetery. Would this be Taukkyan War Cemetery by any chance?

I was also wondering if he was awarded the Burma Star when he was alive? If not, was it, or is it awarded posthumously. Any information you can give me would be so much appreciated. I am so proud of a man I of course did not know but who is remembered by my father as "his favorite uncle". If there is anyone who remembers Jack, I would be thrilled to hear from them. Thank you so very much.

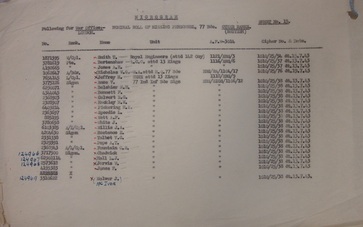

List of Signalmen from 77th Brigade.

Steve was correct in thinking that Jack White served with column 5 under the command of Major Bernard Fergusson in 1943, and that he became a prisoner of war and ended up in Rangoon Jail, where he died on 10th February 1944. Little is known about how Jack became a POW, but we do know that he was given the POW number 556 by his Japanese captors and that he died from beri beri in Block 6 of the jail.

It would seem likely that Signalman White was either lost to his unit on the line of march at some point after dispersal was called, or he was already sick or wounded and was left in some 'friendly' village and picked up by the Japanese from there. During the supply drop on 23rd March at a village called Baw, two new Signalmen were parachuted in and joined the Chindits for the last few weeks of the operation.

I have often wondered if one of these was Jack White, or if the new men were perhaps replacing him after he had become ill or been wounded. Of course, all of this is just guess work and conjecture. Steve stated that his great uncle had been mentioned in Bernard Fergusson's book 'Beyond the Chindwin', the most comprehensive written account about column 5 and their time in Burma. Unfortunately, I believe the references to Signaller White in Fergusson's book actually refer to Signaller Byron White and sadly not Steve's great uncle. It seems amazing that there would be two signalmen in one column both named White, but these type of anomalies occur frequently in Chindit 1 research. Byron White became very ill on the journey out of Burma that year, suffering with malnutrition, caused by his hatred of rice, but he did survive the operation and crossed the Chindwin on 24th April 1943.

Seen to the right is a list of the Signalmen from 77th Brigade in 1943 including Jack White and Eric Rostance. Please click on the image to enlarge. Seen below is the grave memorial of Jack White as found in Rangoon War Cemetery, Burma. It is not Taukkyan War Cemetery (as Steve wondered and is a mistake often made by families looking for information) which is situated further out from Rangoon city centre, but a much smaller plot found in the city centre. It is the final resting place of many of the Chindits from 1943 who died in Rangoon Jail as POW's.

Here are Signalman Jack White's CWGC details, please click on link to view: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2261403/jack-white/

Update 06/11/2012.

I have recently been contacted by Steve Wells, who had stumbled upon this website whilst browsing the Internet with his family. This is what Steve had to tell me:

Mr Steve Fogden.

Back in September of 2002 I had enquired about my great Uncle, Jack White. I had received some information, but not much.

My 16 year old daughter is doing a project about Remembrance Day and was asking about family members who served in the war. I told her about her great great Uncle Jack. We typed in his name on the Internet and along with my original letter to the Burma Star Association came your site with the reference to my letter. Imagine, if you can, my thrilled surprise at the information you had gained from your research. My Daughter and I were fascinated with what you had written. I wish to thank you so much for the effort you have made to obtain this information. It was unfortunate you were not able to get a hold of me through my email address as it is still the same now as it was then. Must have been a technical glitch.

Dad had told me that Jack had been allergic to rice and that may have been the reason, along with maltreatment, for Jacks death in prison.

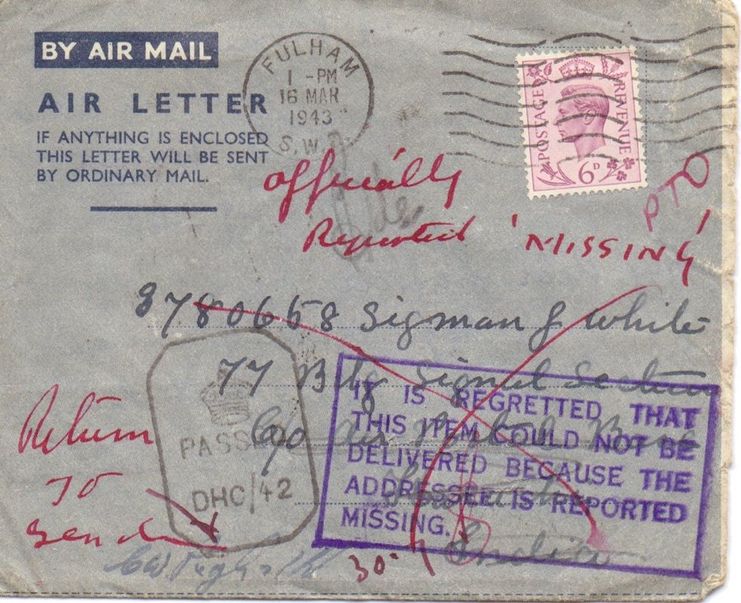

I have a number of unopened letters that were returned to his mother. I thought you might be interested in the markings of one of them. (See image below). I also have the last letter Jack sent to his mother. I imagine he didn¹t have time to post it as it was sent to her by the Army simply stating 'missing in action'.

Again, thank you so so much. This kind of information about our family history is in one word, priceless.

Kind regards

Steve Wells.

It would seem likely that Signalman White was either lost to his unit on the line of march at some point after dispersal was called, or he was already sick or wounded and was left in some 'friendly' village and picked up by the Japanese from there. During the supply drop on 23rd March at a village called Baw, two new Signalmen were parachuted in and joined the Chindits for the last few weeks of the operation.

I have often wondered if one of these was Jack White, or if the new men were perhaps replacing him after he had become ill or been wounded. Of course, all of this is just guess work and conjecture. Steve stated that his great uncle had been mentioned in Bernard Fergusson's book 'Beyond the Chindwin', the most comprehensive written account about column 5 and their time in Burma. Unfortunately, I believe the references to Signaller White in Fergusson's book actually refer to Signaller Byron White and sadly not Steve's great uncle. It seems amazing that there would be two signalmen in one column both named White, but these type of anomalies occur frequently in Chindit 1 research. Byron White became very ill on the journey out of Burma that year, suffering with malnutrition, caused by his hatred of rice, but he did survive the operation and crossed the Chindwin on 24th April 1943.

Seen to the right is a list of the Signalmen from 77th Brigade in 1943 including Jack White and Eric Rostance. Please click on the image to enlarge. Seen below is the grave memorial of Jack White as found in Rangoon War Cemetery, Burma. It is not Taukkyan War Cemetery (as Steve wondered and is a mistake often made by families looking for information) which is situated further out from Rangoon city centre, but a much smaller plot found in the city centre. It is the final resting place of many of the Chindits from 1943 who died in Rangoon Jail as POW's.

Here are Signalman Jack White's CWGC details, please click on link to view: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2261403/jack-white/

Update 06/11/2012.

I have recently been contacted by Steve Wells, who had stumbled upon this website whilst browsing the Internet with his family. This is what Steve had to tell me:

Mr Steve Fogden.

Back in September of 2002 I had enquired about my great Uncle, Jack White. I had received some information, but not much.

My 16 year old daughter is doing a project about Remembrance Day and was asking about family members who served in the war. I told her about her great great Uncle Jack. We typed in his name on the Internet and along with my original letter to the Burma Star Association came your site with the reference to my letter. Imagine, if you can, my thrilled surprise at the information you had gained from your research. My Daughter and I were fascinated with what you had written. I wish to thank you so much for the effort you have made to obtain this information. It was unfortunate you were not able to get a hold of me through my email address as it is still the same now as it was then. Must have been a technical glitch.

Dad had told me that Jack had been allergic to rice and that may have been the reason, along with maltreatment, for Jacks death in prison.

I have a number of unopened letters that were returned to his mother. I thought you might be interested in the markings of one of them. (See image below). I also have the last letter Jack sent to his mother. I imagine he didn¹t have time to post it as it was sent to her by the Army simply stating 'missing in action'.

Again, thank you so so much. This kind of information about our family history is in one word, priceless.

Kind regards

Steve Wells.

Update 22/11/2012.

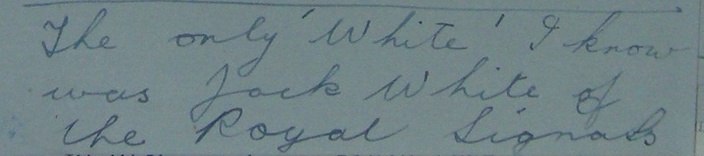

Another document has come to light in regard to Jack White and his Chindit story. From a letter found in the missing in action reports for the 13th King's (file WO361/442) held at the National Archives:

"the only 'White' I know was Jack White of the Royal Signals. Fairly tall, slim, fair, moustache, home London. He died in Rangoon Jail."

This short piece of text is taken from a handwritten letter of some 8 pages, which gives short accounts of a number of men lost on the operation in 1943.

The letter was penned by Pte. Leon Frank who was with Column 7 on Operation Longcloth and who survived nearly two years in Rangoon Jail before being liberated in early May 1945. Leon had made every effort imaginable to help identify what had happened to those men who sadly never returned from Burma, this included letters and missing reports after his release from Rangoon and even visiting some of the casualties families after the war.

To read more about Leon Frank please click on this link: The Longcloth Family (fourth story on the page).

NB. Pte. Frank was only 5' 3", so although I do not think that in todays terms Jack White was that tall, he must of seemed so to poor old Leon. Seen below are the precious few sentences written by Leon Frank in regard to Jack White.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and Steve Wells 2012.

King's Liverpool Cap Badge circa WW2.

King's Liverpool Cap Badge circa WW2.

Pte. William James Baddiley

William Baddiley found himself in column 5 on Operation Longcloth and was one of the very few other ranks from the unit to make it out of Burma alive in 1943. His story can be found on the wonderful BBC website pages, 'WW2, the People's War', an archive of people's memories from 1939-45.

Here is a transcription of Pte. Baddiley's story, as contributed by Cumbria Communities:

The Real Heroes

As a private soldier with the 13th Bn, Kings Liverpool Regiment, we crossed the River Chindwin in January 1943 with the First Wingate Expedition, later to become known as the Chindits. There were seven columns in this operation, mine being No.5 column commanded by Major Bernard Fergusson, the whole constituting the 77th Independent Brigade. (The Brigadier would get very annoyed when this was abbreviated to the 77th Ind. Brigade and so mistaken for the 77th Indian Brigade). He quite often used this Independence which, at times, made him quite unpopular with some of his superiors.

Once across the river (Chindwin) we were behind the enemy lines and had to keep on the move. We travelled east towards the River Irrawaddy, and, apart from a few minor scuffles and blowing up the Rangoon-Mandalay railway line in many different places, we arrived at the Irrawaddy and crossed at Tigyaing. Having completed the crossing the Japs arrived in the village and sent a few mortar bombs and small arms fire after us but did not attempt to cross. We were now in a small triangle formed by the confluence of the Irrawaddy and the Shweli Rivers, and they probably thought that they had us exactly where they wanted us.

After a few weeks we were ordered back to India and rendezvoused with Brigade on the banks of the Irrawaddy, but when we attempted our recrossing were met with heavy mortar and machine gun fire. Wingate decided that recrossing under the circumstances was impossible and so ordered us to break up into groups of about thirty and make our own way back to India. I was with about thirty others under the command of Captain Astell of the Burma Rifles who decided we would not attempt a recrossing of the Irrawaddy but would go east and try the Shweli. This we carried out successfully without any opposition.

After about ten days of marching my boot had broken in half and I found it impossible to keep up with the group. The Captain decided to leave me and Private Carless (Pte. 5110875 John Carless also of column 5) in a village called Sima, which had been a British garrisoned Fort before the evacuation. We thought at least we would have a roof over our heads, but the village Headman would not let us stay in it as the Japs sent regular patrols and they used it as a bivouac.

We were placed in the jungle outside the village and were joined by another B.O.R, namely Pte. 5120086 Harold Baxter. He was very sick and unfortunately died within a few days. I was officially reported missing on April 4th 1943 and Carless and I reached Paoshan in China sometime in early October. We reckoned we had walked about two thousand miles since January. (It is highly likely that William and Pte. Carless were the last of the Chindits to return to India safely and under their own steam in 1943).

We were survivors, but the real heroes of this story were the ordinary villagers of small places in the Kachin Hills who watered and fed us and harboured us in the sure knowledge that if they were caught doing this they would have been crucified to the floor of their huts.

William turned out to be somewhat of a hero himself, not only had he been one of only a handful of column 5 other ranks to survive the operation, but he, along with Pte. Carless had made a concerted effort to inform the Army investigation office of the whereabouts of many of the Chindit casualties and their last known positions in 1943. William spent a few weeks in hospital at Shillong in India, from where he gave these accounts for the men now listed as missing in action.

William Baddiley found himself in column 5 on Operation Longcloth and was one of the very few other ranks from the unit to make it out of Burma alive in 1943. His story can be found on the wonderful BBC website pages, 'WW2, the People's War', an archive of people's memories from 1939-45.

Here is a transcription of Pte. Baddiley's story, as contributed by Cumbria Communities:

The Real Heroes

As a private soldier with the 13th Bn, Kings Liverpool Regiment, we crossed the River Chindwin in January 1943 with the First Wingate Expedition, later to become known as the Chindits. There were seven columns in this operation, mine being No.5 column commanded by Major Bernard Fergusson, the whole constituting the 77th Independent Brigade. (The Brigadier would get very annoyed when this was abbreviated to the 77th Ind. Brigade and so mistaken for the 77th Indian Brigade). He quite often used this Independence which, at times, made him quite unpopular with some of his superiors.

Once across the river (Chindwin) we were behind the enemy lines and had to keep on the move. We travelled east towards the River Irrawaddy, and, apart from a few minor scuffles and blowing up the Rangoon-Mandalay railway line in many different places, we arrived at the Irrawaddy and crossed at Tigyaing. Having completed the crossing the Japs arrived in the village and sent a few mortar bombs and small arms fire after us but did not attempt to cross. We were now in a small triangle formed by the confluence of the Irrawaddy and the Shweli Rivers, and they probably thought that they had us exactly where they wanted us.

After a few weeks we were ordered back to India and rendezvoused with Brigade on the banks of the Irrawaddy, but when we attempted our recrossing were met with heavy mortar and machine gun fire. Wingate decided that recrossing under the circumstances was impossible and so ordered us to break up into groups of about thirty and make our own way back to India. I was with about thirty others under the command of Captain Astell of the Burma Rifles who decided we would not attempt a recrossing of the Irrawaddy but would go east and try the Shweli. This we carried out successfully without any opposition.

After about ten days of marching my boot had broken in half and I found it impossible to keep up with the group. The Captain decided to leave me and Private Carless (Pte. 5110875 John Carless also of column 5) in a village called Sima, which had been a British garrisoned Fort before the evacuation. We thought at least we would have a roof over our heads, but the village Headman would not let us stay in it as the Japs sent regular patrols and they used it as a bivouac.

We were placed in the jungle outside the village and were joined by another B.O.R, namely Pte. 5120086 Harold Baxter. He was very sick and unfortunately died within a few days. I was officially reported missing on April 4th 1943 and Carless and I reached Paoshan in China sometime in early October. We reckoned we had walked about two thousand miles since January. (It is highly likely that William and Pte. Carless were the last of the Chindits to return to India safely and under their own steam in 1943).

We were survivors, but the real heroes of this story were the ordinary villagers of small places in the Kachin Hills who watered and fed us and harboured us in the sure knowledge that if they were caught doing this they would have been crucified to the floor of their huts.

William turned out to be somewhat of a hero himself, not only had he been one of only a handful of column 5 other ranks to survive the operation, but he, along with Pte. Carless had made a concerted effort to inform the Army investigation office of the whereabouts of many of the Chindit casualties and their last known positions in 1943. William spent a few weeks in hospital at Shillong in India, from where he gave these accounts for the men now listed as missing in action.

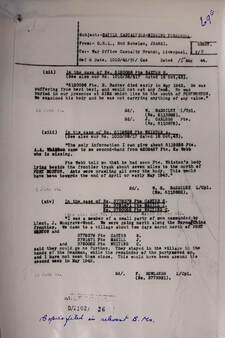

Missing in Action Report

Seen left, is one of the reports given by William and Pte. Carless, including the fate of Harold Baxter, who as you will read died from the effects of beri beri and loss of appetite in the village of Sima. Please click on the image to enlarge.

Here are Harold Baxter's CWGC details:

www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2505023/harold-baxter/

Pte. Baddiley also gave a second report in regard to Harold Baxter and another soldier, Pte. A. Whiston, here is a transcription of that document:

It is understood that Pte. 5113882 W. Baddiley, the Kings Regiment, was admitted to the British Military Hospital at Shillong, India, on 30th August 1943. It was here that he informed Pte. Rowlands, also of the Kings Regiment, of the deaths of the above named (Baxter and Whiston) and the location of their respected graves. Could you therefore obtain from Pte. Rowlands a statement in regard to the mentioned other ranks and confirm the details he was given by W. Baddiley, especially concerning the grave location.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and Cumbria Communities 2012.

Here are Harold Baxter's CWGC details:

www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2505023/harold-baxter/

Pte. Baddiley also gave a second report in regard to Harold Baxter and another soldier, Pte. A. Whiston, here is a transcription of that document:

It is understood that Pte. 5113882 W. Baddiley, the Kings Regiment, was admitted to the British Military Hospital at Shillong, India, on 30th August 1943. It was here that he informed Pte. Rowlands, also of the Kings Regiment, of the deaths of the above named (Baxter and Whiston) and the location of their respected graves. Could you therefore obtain from Pte. Rowlands a statement in regard to the mentioned other ranks and confirm the details he was given by W. Baddiley, especially concerning the grave location.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and Cumbria Communities 2012.

Sergeant John Thornborrow MM

Formerly with the Border Regiment in WW2 John Thornborrow had found himself in the Central Provinces of India by June 1942, training to become part of Wingate's new Chindit Army. As time moved on at the Saugor training camp he was seconded to column 5 and placed as lead NCO in platoon 7 under the overall command of Lieutenant Philip Stibbe. John had replaced the previous platoon sergeant Robert Marchbank, who had been poached away by Northern Section's HQ and became their Quartermaster Sergeant in late summer that year.

Lieutenant Stibbe was not amused to lose such a well respected NCO, but soon realised what a fine replacement he had acquired in John Thornborrow:

I lost Sgt. Marchbank to battalion HQ, I was most put out, but before long I was given Sgt. Thornborrow to console me. He was a good natured giant of a man from Kendal. He used to work as a 'bottler' in a brewery and was certainly a good advertisement for beer. I sometimes wondered if he wasn't too good natured and that the men might take advantage, but in the end they seemed to respect him all the more for it. Thornborrow was the best of sergeants, patient, unperturbed in a crisis and unswervingly loyal.

The image of John Thornborrow shown above, was painted by the War Artist, Harry Sheldon and was presented to John's mother by Philip Stibbe after the war.

NB. Harry Sheldon, born in Cheshire was a Lieutenant with the 8th Gurkha Rifles during the war and had studied art under the mentorship of LS. Lowry. By the end of the war, Sheldon, then only 28, had left behind a formidable artistic legacy in the fading light of the British Raj. He had painted most of the famous Indian Army commanders: the future Admiral of the Fleet, Earl Mountbatten of Burma; Field-Marshall Lord Wavell, Viceroy of India; Auchinleck; Lt-General Sir Frederick Browning; Field Marshal Viscount Slim and all the Indian Army Victoria Cross recipients. Today, Sheldon’s works are scattered throughout the sub-continent mostly in museums.

Formerly with the Border Regiment in WW2 John Thornborrow had found himself in the Central Provinces of India by June 1942, training to become part of Wingate's new Chindit Army. As time moved on at the Saugor training camp he was seconded to column 5 and placed as lead NCO in platoon 7 under the overall command of Lieutenant Philip Stibbe. John had replaced the previous platoon sergeant Robert Marchbank, who had been poached away by Northern Section's HQ and became their Quartermaster Sergeant in late summer that year.

Lieutenant Stibbe was not amused to lose such a well respected NCO, but soon realised what a fine replacement he had acquired in John Thornborrow:

I lost Sgt. Marchbank to battalion HQ, I was most put out, but before long I was given Sgt. Thornborrow to console me. He was a good natured giant of a man from Kendal. He used to work as a 'bottler' in a brewery and was certainly a good advertisement for beer. I sometimes wondered if he wasn't too good natured and that the men might take advantage, but in the end they seemed to respect him all the more for it. Thornborrow was the best of sergeants, patient, unperturbed in a crisis and unswervingly loyal.

The image of John Thornborrow shown above, was painted by the War Artist, Harry Sheldon and was presented to John's mother by Philip Stibbe after the war.

NB. Harry Sheldon, born in Cheshire was a Lieutenant with the 8th Gurkha Rifles during the war and had studied art under the mentorship of LS. Lowry. By the end of the war, Sheldon, then only 28, had left behind a formidable artistic legacy in the fading light of the British Raj. He had painted most of the famous Indian Army commanders: the future Admiral of the Fleet, Earl Mountbatten of Burma; Field-Marshall Lord Wavell, Viceroy of India; Auchinleck; Lt-General Sir Frederick Browning; Field Marshal Viscount Slim and all the Indian Army Victoria Cross recipients. Today, Sheldon’s works are scattered throughout the sub-continent mostly in museums.

John Thornborrow always led from the front, both in training and then on the expedition itself. In late March 1943 column 5 were engaged in a heavy fire fight with a Japanese patrol in a village called Hintha. They had been acting as rear guard for Northern Section and Fergusson was attempting to run a decoy trail for the Japanese pursuers to follow. Platoon 7 were used as the spearhead in the action at Hintha and suffered many casualties on the evening of 28th March, including platoon commander Philip Stibbe. As the wounded Lieutenant was led away, it fell to Thornborrow to take command of the platoon and ensure the enemy was effectively dealt with. This he achieved, and when dispersal was finally called, he was there to gather his men, tend to their wounds and move them quickly away to rejoin the column at the previously agreed rendezvous.

The story of what became of Philip Stibbe and the other men of platoon 7 can be seen here: Stibbe's Platoon.

After successfully rejoining with the main body of column 5, John spent the next few days marching at the head of the column in the company of Major Bernard Fergusson. In his book 'Beyond the Chindwin', Fergusson tells the story of how Sgt. Thornborrow willingly tore his own thermal blanket in half and handed a section to his Major, this helped keep him warm during the cold and damp nights on the march back to India. By the end of the expedition John was part of Flight Lieutenant Denny Sharpe's dispersal group and re-crossed the Chindwin sometime around the 18th of April with approximately 25 other men.

The photograph shown to the right is of Sergeant John Thornborrow MM, pictured having just received his gallantry award from Viscount Archibald Wavell no less. From the pages of the Lancashire Daily Post, dated 14th March 1944, and under the headline:

Oxenholme Man Decorated by Viceroy

Sergeant John Thornborrow, 13th King's Regiment of 11 Helmside Road, Oxenholme, who distinguished himself during the famous Wingate Expedition (1943) in Burma, was decorated with the Miltary Medal today by Lord Wavell, the Viceroy of India.

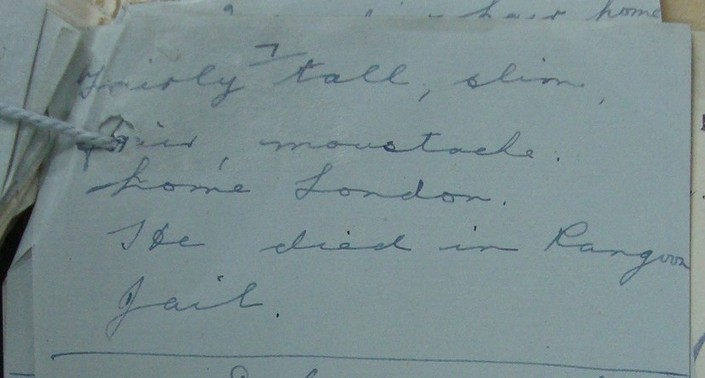

Seen below is a photograph of his Military Medal citation, stating the reason for the award. Apologies for the poor quality of the text.

The story of what became of Philip Stibbe and the other men of platoon 7 can be seen here: Stibbe's Platoon.

After successfully rejoining with the main body of column 5, John spent the next few days marching at the head of the column in the company of Major Bernard Fergusson. In his book 'Beyond the Chindwin', Fergusson tells the story of how Sgt. Thornborrow willingly tore his own thermal blanket in half and handed a section to his Major, this helped keep him warm during the cold and damp nights on the march back to India. By the end of the expedition John was part of Flight Lieutenant Denny Sharpe's dispersal group and re-crossed the Chindwin sometime around the 18th of April with approximately 25 other men.

The photograph shown to the right is of Sergeant John Thornborrow MM, pictured having just received his gallantry award from Viscount Archibald Wavell no less. From the pages of the Lancashire Daily Post, dated 14th March 1944, and under the headline:

Oxenholme Man Decorated by Viceroy

Sergeant John Thornborrow, 13th King's Regiment of 11 Helmside Road, Oxenholme, who distinguished himself during the famous Wingate Expedition (1943) in Burma, was decorated with the Miltary Medal today by Lord Wavell, the Viceroy of India.

Seen below is a photograph of his Military Medal citation, stating the reason for the award. Apologies for the poor quality of the text.

John Thornborrow remained with the 13th Kings for the rest of the war, serving with them for the most part at the Napier Barracks in Karachi. Here the battalion performed various internal security duties, but also occasionally provided drafts of men for special duties, including the proposed third Chindit force in late 1944. After the last few stragglers from Operation Longcloth had returned to India in 1943, the task of recording what had happened to the numerous casualties began. Sergeant Thornborrow was asked to account for the lost members of platoon 7, especially in regard to the action at Hintha. Here is a transcription of one of his reports dealing with the case of Corporal Handley and Lance Corporal Berry:

Statement of evidence in accordance with Battalion instruction K.O. 89019, dated 24/07/1943, in the case of the under-mentioned:

3769092 Corporal R. Handley and

3779430 L/Corporal A. Berry.

3599442 Sgt. J. Thornborrow states: I was platoon Sergeant of Platoon 7, column 5 of 77th Indian Infantry Brigade. We engaged the enemy in the village of Hintha (map reference SN 1739) on the 28th March 1943. Corp. Handley and L/Corp. Berry were last seen with the platoon leading towards the village; on reaching the village the platoon were ordered to perform a full bayonet charge. After the engagement was over neither of the NCO's were seen again.

Here are the CWGC details for Robert William Handley and Albert Berry (please click on the links to view their pages):

www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2510670/robert-william-handley/

www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2505152/albert-berry/

Sadly, John Thornborrow passed away on the 14th September 1995, after a short but sudden illness.

Copyright © Steve Fogden 2012.

Statement of evidence in accordance with Battalion instruction K.O. 89019, dated 24/07/1943, in the case of the under-mentioned:

3769092 Corporal R. Handley and

3779430 L/Corporal A. Berry.

3599442 Sgt. J. Thornborrow states: I was platoon Sergeant of Platoon 7, column 5 of 77th Indian Infantry Brigade. We engaged the enemy in the village of Hintha (map reference SN 1739) on the 28th March 1943. Corp. Handley and L/Corp. Berry were last seen with the platoon leading towards the village; on reaching the village the platoon were ordered to perform a full bayonet charge. After the engagement was over neither of the NCO's were seen again.

Here are the CWGC details for Robert William Handley and Albert Berry (please click on the links to view their pages):

www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2510670/robert-william-handley/

www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2505152/albert-berry/

Sadly, John Thornborrow passed away on the 14th September 1995, after a short but sudden illness.

Copyright © Steve Fogden 2012.

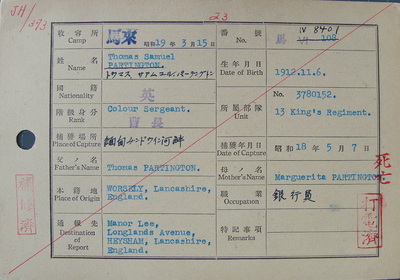

Thomas Partington.

CQMS. Thomas Samuel Partington

Thomas Samuel Partington was born in Manchester in 1912, the son of Thomas (senior) and Marguerita Partington of Manor House, 1 Longlands Avenue, Heysham, Morecambe in Lancashire. In civilian life young Thomas was employed at the district bank in Egremont, Cumbria. He had followed in his father's footsteps in this respect as Thomas senior was a former bank clerk in the Lancashire town of Eccles according to the 1911 Census records. CQMS Partington is remembered on the Morecambe Town War Memorial.

Thomas was one of the more experienced NCO's within the original 13th Kings battalion which travelled to India in late 1941. He was Quartermaster Sergeant during Chindit training, a rank which required such personal characteristics as sound judgement and a trustworthy nature. He was attached to Column 7 on Operation Longcloth and on dispersal in April 1943, he was part of Lieutenant Walker's party. This group was made up of four officers, Partington as leading NCO and around 20 other ranks, all of which were already either seriously ill or had received a wound whilst on the expedition. The chances of this particular dispersal party returning to India successfully were extremely slim.

To read about the fate of this group, please click on the link: Rex Walker's Dispersal Group 4

The group was ambushed very shortly after the initial dispersal and suffered many casualties. Thomas managed to evade the Japanese for several weeks before being taken prisoner on 7th May. He was captured on the eastern banks of the Chindwin River, frustratingly close to the safety of Allied held lines. Once inside Rangoon Jail, he was given the difficult task of keeping the captured Kingsmen in some sort of order whilst they were all squeezed into Block 6 of the prison. Thomas was given the POW number 108 in Rangoon.

As the early weeks and months went by he would have seen many of his comrades lose their fight for survival in Block 6, often dying in small clusters of two or three on a daily basis. He would have undoubtedly been involved in their burials at the English Cantonment Cemetery, located a few short miles from the jail. In late 1943 Thomas himself contracted beri beri and dysentery, a slow and painful decline finally ended on the 15th January 1945, when he too perished in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail. He was buried in the Cantonment Cemetery alongside his fallen comrades and his grave was recorded by the attending officers as number 230.

Here are Thomas Partington's CWGC details: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2261066/thomas-samuel-partington/

Thomas is not mentioned in any of the books or diaries written about Operation Longcloth, however, in the personal memoirs of Lieutenant 'Willie' Wilding (an officer attached to Wingate's HQ in 1943) the Company Quartermaster Sergeant is remembered thus:

For some time he had the thankless task of being the senior NCO in the turbulent and ramshackle Block 6 of Rangoon Jail. He did his best, and it was a very good best. Poor chap died quite early on of dysentery.

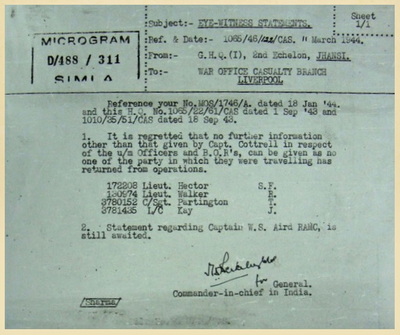

To finish the story of Thomas Partington please see below a note showing the 'missing in action' status of some of the officers and NCO's (including Thomas) of Rex Walker's dispersal group from April 1943. No further information was possible at the time of the debrief sessions because the only men to survive from the group were still locked up inside Rangoon Jail. Also shown is the obverse of his POW index card.

Thomas Samuel Partington was born in Manchester in 1912, the son of Thomas (senior) and Marguerita Partington of Manor House, 1 Longlands Avenue, Heysham, Morecambe in Lancashire. In civilian life young Thomas was employed at the district bank in Egremont, Cumbria. He had followed in his father's footsteps in this respect as Thomas senior was a former bank clerk in the Lancashire town of Eccles according to the 1911 Census records. CQMS Partington is remembered on the Morecambe Town War Memorial.

Thomas was one of the more experienced NCO's within the original 13th Kings battalion which travelled to India in late 1941. He was Quartermaster Sergeant during Chindit training, a rank which required such personal characteristics as sound judgement and a trustworthy nature. He was attached to Column 7 on Operation Longcloth and on dispersal in April 1943, he was part of Lieutenant Walker's party. This group was made up of four officers, Partington as leading NCO and around 20 other ranks, all of which were already either seriously ill or had received a wound whilst on the expedition. The chances of this particular dispersal party returning to India successfully were extremely slim.

To read about the fate of this group, please click on the link: Rex Walker's Dispersal Group 4

The group was ambushed very shortly after the initial dispersal and suffered many casualties. Thomas managed to evade the Japanese for several weeks before being taken prisoner on 7th May. He was captured on the eastern banks of the Chindwin River, frustratingly close to the safety of Allied held lines. Once inside Rangoon Jail, he was given the difficult task of keeping the captured Kingsmen in some sort of order whilst they were all squeezed into Block 6 of the prison. Thomas was given the POW number 108 in Rangoon.

As the early weeks and months went by he would have seen many of his comrades lose their fight for survival in Block 6, often dying in small clusters of two or three on a daily basis. He would have undoubtedly been involved in their burials at the English Cantonment Cemetery, located a few short miles from the jail. In late 1943 Thomas himself contracted beri beri and dysentery, a slow and painful decline finally ended on the 15th January 1945, when he too perished in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail. He was buried in the Cantonment Cemetery alongside his fallen comrades and his grave was recorded by the attending officers as number 230.

Here are Thomas Partington's CWGC details: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2261066/thomas-samuel-partington/

Thomas is not mentioned in any of the books or diaries written about Operation Longcloth, however, in the personal memoirs of Lieutenant 'Willie' Wilding (an officer attached to Wingate's HQ in 1943) the Company Quartermaster Sergeant is remembered thus:

For some time he had the thankless task of being the senior NCO in the turbulent and ramshackle Block 6 of Rangoon Jail. He did his best, and it was a very good best. Poor chap died quite early on of dysentery.

To finish the story of Thomas Partington please see below a note showing the 'missing in action' status of some of the officers and NCO's (including Thomas) of Rex Walker's dispersal group from April 1943. No further information was possible at the time of the debrief sessions because the only men to survive from the group were still locked up inside Rangoon Jail. Also shown is the obverse of his POW index card.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and John Robertson (photograph of Thomas Partington) 2012.

Pte. Robert Hamer, Karachi 1944.

Pte. Robert Hamer

Pte. Robert Hamer of the 13th Kings was in column 8 on Operation Longcloth and remained with his column commander Major Walter Scott for almost all of the expedition. He has not been mentioned very much in the books or documents that I have read, but his photograph (seen to the left) was first featured in Philip Chinnery's book March or Die in 1996.

Robert served as a range finder in the column's Support Group Platoon, comprising of Vicker's machine guns and 3" mortars. He carried for his own protection a service revolver and a shot gun, two rather unusual weapons for a Private soldier to possess.

In 1996 he told Philip Chinnery that he had stayed with his column for the vast majority of the expedition, only finding himself in a smaller dispersal party very late on in April 1943. This group was ambushed by the Japanese whilst in bivouac by a small river and in the confusion to escape, twenty-two men were left with just two rifles between them.

Pte. Hamer's journey with column 8 in 1943 would have seen him in close proximity to Wingate's HQ during the early weeks of the expedition. He would have experienced the trauma of getting over the Shweli River in early April, where the column lost contact with one of it's lead platoons commanded by Captain Bill Williams, the long periods of starvation as the air supply drops became few and far between and the disastrous enemy ambush at the Kaukkwe Chaung.

He would have also watched with slightly envious eyes as the Dakota supply plane lifted off from the impromptu jungle runway at Sonpu (Piccadilly rescue), taking with it 17 of his sick and wounded Chindit comrades. Re-fitted with new boots and uniforms and with eight days rations in their packs, the rest of column 8 marched on in good spirits towards India. After many more days of hard and arduous marching the dispersal groups of the column began to re-cross the River Chindwin and with one of these groups came Pte. Robert Hamer. He and the rest of the surviving Chindits enjoyed some royal treatment at the 19th Casualty Clearing Station in Imphal, run by the very able and compassionate Matron Agnes McGeary.

After the action at the Kaukkwe Chaung on the 30th April, Robert and 21 other men were separated from the column for the very first time. It was during this engagement that he lost both his revolver (handed over to an officer) and his shot gun (lost whilst crossing the river).

In a letter written in 1996, Robert recalled his return journey to India in May 1943:

After the ambush some of the men were re-grouping on the far bank and Captain Carroll was giving orders. I collected up a spare rifle and we all set off with Captain Carroll in a north easterly direction. We set off into the dense jungle, it was so dark that each man held on to the rifle of the man in front to keep in contact with each other. I was tail-end Charlie behind my mate, Con O’Leary. After several hours we discovered that up at the front contact had been lost with the main group and that around twenty of us were now on our own. Fortunately, I had a compass and passed this to the senior NCO, Sgt. Puckett of the Signals section who had previously worked in covert operations in China.

On our first night away from the column we slept in elephant grass. All throughout the night we could hear trains, so we must have been quite close to the railway. We soon found that to be true in the morning as we were spotted immediately by a Burmese villager who raised the alarm. We ran for it and were soon on the rail tracks just thirty yards from the station. Luck was with us that day and we crossed the tracks and got away into the scrub on the other side.

The next three days we avoided villages and kept moving even though we were very hungry by this time. We passed by a herd of bison and killed one, eating the raw flesh as we marched on, but our stomachs paid a heavy penalty from eating the raw meat. A few days later we used a grenade in a small stream to stun the fish which then floated to the surface. I also ate some plum-like fruit that was full of ants or midges, I don’t know how many of these insects I devoured that day. That afternoon we bumped a Japanese patrol on a dirt track and came under fire. We used the detour tactics we had been taught back in India and it paid off as we managed to lose the enemy in the nearby jungle scrub.

From then on, we decided to march by night and rest up during the day. Thankfully, it was not long before we reached the Chindwin and were taken across by some British soldiers who were posted on the river to collect us stragglers back in. We were given some much-needed food and a new pack to put all our possessions in, not that we had much by then. We were taken to the next camp up in the hills behind the river and camped down there.

All of my party got back. Each man knew what he had to do, with Sgt. Puckett leading the way. Later on, Sgt. Puckett asked if he could keep my compass as a reminder of our successful escape back to India. As he had led us out so successfully, I agreed.

In later life Robert Hamer lived in Frenchwood near Preston and was an active member of the Burma Star Association.

Copyright © Steve Fogden 2011.

Pte. Robert Hamer of the 13th Kings was in column 8 on Operation Longcloth and remained with his column commander Major Walter Scott for almost all of the expedition. He has not been mentioned very much in the books or documents that I have read, but his photograph (seen to the left) was first featured in Philip Chinnery's book March or Die in 1996.

Robert served as a range finder in the column's Support Group Platoon, comprising of Vicker's machine guns and 3" mortars. He carried for his own protection a service revolver and a shot gun, two rather unusual weapons for a Private soldier to possess.

In 1996 he told Philip Chinnery that he had stayed with his column for the vast majority of the expedition, only finding himself in a smaller dispersal party very late on in April 1943. This group was ambushed by the Japanese whilst in bivouac by a small river and in the confusion to escape, twenty-two men were left with just two rifles between them.

Pte. Hamer's journey with column 8 in 1943 would have seen him in close proximity to Wingate's HQ during the early weeks of the expedition. He would have experienced the trauma of getting over the Shweli River in early April, where the column lost contact with one of it's lead platoons commanded by Captain Bill Williams, the long periods of starvation as the air supply drops became few and far between and the disastrous enemy ambush at the Kaukkwe Chaung.

He would have also watched with slightly envious eyes as the Dakota supply plane lifted off from the impromptu jungle runway at Sonpu (Piccadilly rescue), taking with it 17 of his sick and wounded Chindit comrades. Re-fitted with new boots and uniforms and with eight days rations in their packs, the rest of column 8 marched on in good spirits towards India. After many more days of hard and arduous marching the dispersal groups of the column began to re-cross the River Chindwin and with one of these groups came Pte. Robert Hamer. He and the rest of the surviving Chindits enjoyed some royal treatment at the 19th Casualty Clearing Station in Imphal, run by the very able and compassionate Matron Agnes McGeary.

After the action at the Kaukkwe Chaung on the 30th April, Robert and 21 other men were separated from the column for the very first time. It was during this engagement that he lost both his revolver (handed over to an officer) and his shot gun (lost whilst crossing the river).

In a letter written in 1996, Robert recalled his return journey to India in May 1943:

After the ambush some of the men were re-grouping on the far bank and Captain Carroll was giving orders. I collected up a spare rifle and we all set off with Captain Carroll in a north easterly direction. We set off into the dense jungle, it was so dark that each man held on to the rifle of the man in front to keep in contact with each other. I was tail-end Charlie behind my mate, Con O’Leary. After several hours we discovered that up at the front contact had been lost with the main group and that around twenty of us were now on our own. Fortunately, I had a compass and passed this to the senior NCO, Sgt. Puckett of the Signals section who had previously worked in covert operations in China.

On our first night away from the column we slept in elephant grass. All throughout the night we could hear trains, so we must have been quite close to the railway. We soon found that to be true in the morning as we were spotted immediately by a Burmese villager who raised the alarm. We ran for it and were soon on the rail tracks just thirty yards from the station. Luck was with us that day and we crossed the tracks and got away into the scrub on the other side.

The next three days we avoided villages and kept moving even though we were very hungry by this time. We passed by a herd of bison and killed one, eating the raw flesh as we marched on, but our stomachs paid a heavy penalty from eating the raw meat. A few days later we used a grenade in a small stream to stun the fish which then floated to the surface. I also ate some plum-like fruit that was full of ants or midges, I don’t know how many of these insects I devoured that day. That afternoon we bumped a Japanese patrol on a dirt track and came under fire. We used the detour tactics we had been taught back in India and it paid off as we managed to lose the enemy in the nearby jungle scrub.

From then on, we decided to march by night and rest up during the day. Thankfully, it was not long before we reached the Chindwin and were taken across by some British soldiers who were posted on the river to collect us stragglers back in. We were given some much-needed food and a new pack to put all our possessions in, not that we had much by then. We were taken to the next camp up in the hills behind the river and camped down there.

All of my party got back. Each man knew what he had to do, with Sgt. Puckett leading the way. Later on, Sgt. Puckett asked if he could keep my compass as a reminder of our successful escape back to India. As he had led us out so successfully, I agreed.

In later life Robert Hamer lived in Frenchwood near Preston and was an active member of the Burma Star Association.

Copyright © Steve Fogden 2011.

Lance Corporal James Rogerson

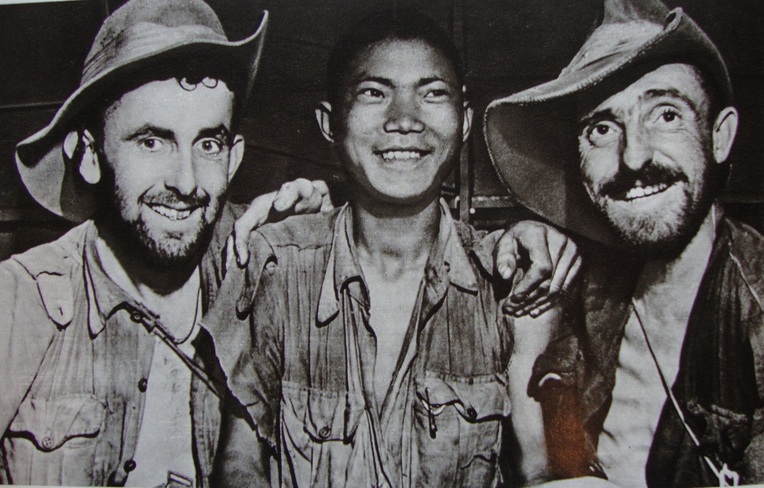

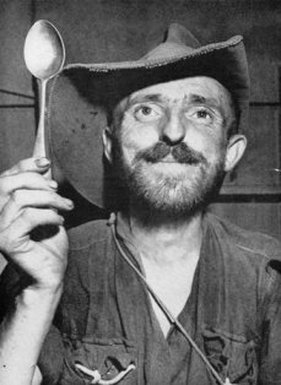

This image (seen left) has become an iconic photograph from the Burma Campaign of WW2, and yet for the majority of the time since then the soldier featured has never been named. It is a photo of Jim Rogerson of the 13th Kings holding his beloved spoon (which had not seen much food toward the latter days of the 1943 Chindit operation) and about to fly out of the Burmese jungle in a Dakota transport plane.

Jim, originally from Blackburn, was a member of column 8 on Operation Longcloth in 1943 and had been marching with his unit for over 8 weeks when he suddenly began to feel very ill in late April that year.

The odds were stacked against him and several other sick and wounded men from column 8, as food became scarce and the ravages of the climate and terrain began to take it's toll. Men had already disappeared from the line of march, as starvation and sickness caused them to drop out and the column commander Major Scott was contemplating leaving the rest of the stragglers in the next 'friendly' Burmese village.

For once luck seemed to be on the side of the Chindits, as their commander now explains:

We were nearly out of rations and in a poor physical state, when suddenly hope returned to bolster our flagging spirits. As we marched through the dense and dark jungle the track ahead began to grow a little lighter, within a few minutes we were standing on the edge of a large open field, possibly the largest patch of open ground in this part of northern Burma.

Reacting quickly the column secured the perimeter and set about catching the eye of any passing Allied aircraft. They did this by tearing up old parachute cloth and the white maps they had been issued, and presenting the words 'Plane Land Here Now' on the clearing floor. Soon enough some planes came over and began dropping the much needed supplies to the column, one plane did attempt to land, but being unsure about the condition of the ground had to abort at the last minute. However, after some fraught communication between Major Scott and the RAF, another Dakota attempted a landing two days later. Flying Officer Michael Vlasto landed his C-47 successfully and 18 sick and wounded men were put aboard and evacuated out to India within the hour. Jim Rogerson took his place on the aircraft knowing that the actions of the Indian born pilot had almost certainly saved his life. On the list of evacuated personnel found in the War Diary for column 8, it simply says 'sick' against the name of Jim Rogerson, the whole episode became a propaganda coup for the Allies, as journalists in the region wrote up the miraculous story of the daring airlift.

Back on the ground, the hope was that the rest of the column might be able to exit Burma in the same fashion. Sadly, this was not to be. Major Scott received this communique from RAF HQ:

After very careful consideration I have reluctantly decided not to allow the pilot to take the risk of landing his plane again. Apart from the actual landing risks there is considerable danger of interference from Japanese land and air forces. This must, I realise, be a very great disappointment to you and your men. Signed, Major-General G. Scoones Corps HQ.

The remaining men from column 8 were dropped new boots and supplies and continued their march out of Burma, which for the eventual survivors took another three to four weeks. The jungle clearing where Vlasto's Dakota landed was earmarked to be used again in 1944, this time as a Chindit air base code named 'Piccadilly', Wingate hoped to land half his Waco gliders on the site, but this never materialized due to unforeseen circumstances. I will no doubt write about the 'Piccadilly' airlift in greater detail elsewhere on these website pages.

In January 2010 I managed to make contact with Lee Rogerson, Jim's grandson. This is what he had to say:

Hello Steve, you are correct my grandad is the man on the right of the picture with the darker beard, but thats the only thing I know about him, my Mum has told me also this week that he remarried and has a second family, who are also my uncles, aunts cousins etc. This story is opening up into a bigger picture now. Please can yon foward the pictures you have of him and any other information and I will carry on tracing this issue and get back to you with any new material. By the way, we have just recently had a new baby, who we are naming Freddie James after his grandfather and great grandfather respectively.

The photo that Lee was referring to can be seen below and shows James Rogerson (right as we look) with two of his fellow Dakota passengers, Rifleman Kalabahdur of 3/2 Gurkha Rifles(centre) and Pte. Jack Wilson of the 13th Kings, from Preston.

This image (seen left) has become an iconic photograph from the Burma Campaign of WW2, and yet for the majority of the time since then the soldier featured has never been named. It is a photo of Jim Rogerson of the 13th Kings holding his beloved spoon (which had not seen much food toward the latter days of the 1943 Chindit operation) and about to fly out of the Burmese jungle in a Dakota transport plane.

Jim, originally from Blackburn, was a member of column 8 on Operation Longcloth in 1943 and had been marching with his unit for over 8 weeks when he suddenly began to feel very ill in late April that year.

The odds were stacked against him and several other sick and wounded men from column 8, as food became scarce and the ravages of the climate and terrain began to take it's toll. Men had already disappeared from the line of march, as starvation and sickness caused them to drop out and the column commander Major Scott was contemplating leaving the rest of the stragglers in the next 'friendly' Burmese village.

For once luck seemed to be on the side of the Chindits, as their commander now explains:

We were nearly out of rations and in a poor physical state, when suddenly hope returned to bolster our flagging spirits. As we marched through the dense and dark jungle the track ahead began to grow a little lighter, within a few minutes we were standing on the edge of a large open field, possibly the largest patch of open ground in this part of northern Burma.

Reacting quickly the column secured the perimeter and set about catching the eye of any passing Allied aircraft. They did this by tearing up old parachute cloth and the white maps they had been issued, and presenting the words 'Plane Land Here Now' on the clearing floor. Soon enough some planes came over and began dropping the much needed supplies to the column, one plane did attempt to land, but being unsure about the condition of the ground had to abort at the last minute. However, after some fraught communication between Major Scott and the RAF, another Dakota attempted a landing two days later. Flying Officer Michael Vlasto landed his C-47 successfully and 18 sick and wounded men were put aboard and evacuated out to India within the hour. Jim Rogerson took his place on the aircraft knowing that the actions of the Indian born pilot had almost certainly saved his life. On the list of evacuated personnel found in the War Diary for column 8, it simply says 'sick' against the name of Jim Rogerson, the whole episode became a propaganda coup for the Allies, as journalists in the region wrote up the miraculous story of the daring airlift.

Back on the ground, the hope was that the rest of the column might be able to exit Burma in the same fashion. Sadly, this was not to be. Major Scott received this communique from RAF HQ:

After very careful consideration I have reluctantly decided not to allow the pilot to take the risk of landing his plane again. Apart from the actual landing risks there is considerable danger of interference from Japanese land and air forces. This must, I realise, be a very great disappointment to you and your men. Signed, Major-General G. Scoones Corps HQ.

The remaining men from column 8 were dropped new boots and supplies and continued their march out of Burma, which for the eventual survivors took another three to four weeks. The jungle clearing where Vlasto's Dakota landed was earmarked to be used again in 1944, this time as a Chindit air base code named 'Piccadilly', Wingate hoped to land half his Waco gliders on the site, but this never materialized due to unforeseen circumstances. I will no doubt write about the 'Piccadilly' airlift in greater detail elsewhere on these website pages.

In January 2010 I managed to make contact with Lee Rogerson, Jim's grandson. This is what he had to say:

Hello Steve, you are correct my grandad is the man on the right of the picture with the darker beard, but thats the only thing I know about him, my Mum has told me also this week that he remarried and has a second family, who are also my uncles, aunts cousins etc. This story is opening up into a bigger picture now. Please can yon foward the pictures you have of him and any other information and I will carry on tracing this issue and get back to you with any new material. By the way, we have just recently had a new baby, who we are naming Freddie James after his grandfather and great grandfather respectively.

The photo that Lee was referring to can be seen below and shows James Rogerson (right as we look) with two of his fellow Dakota passengers, Rifleman Kalabahdur of 3/2 Gurkha Rifles(centre) and Pte. Jack Wilson of the 13th Kings, from Preston.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and Lee Rogerson 2012.

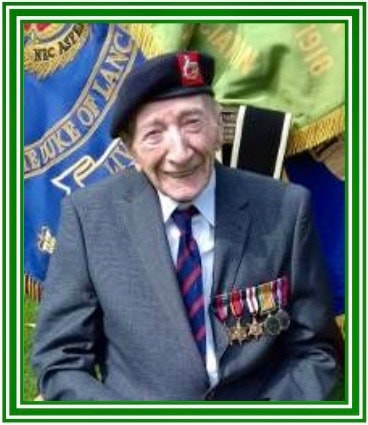

Tom Gilzean receives the Edinburgh Award.

Tom Gilzean receives the Edinburgh Award.

Thomas Gilzean

A good friend of mine recently moved home up to Scotland. On one of his first visits to Edinburgh he bumped into Tom Gilzean. Tom told him that he had served in Burma, including on the first Chindit operation where he served in Chindit Column 1 as an engineer attachment. This news was of great interest to me, as up till then I had not been aware of Tom's involvement on Operation Longcloth.

1 Column was in the majority a Gurkha unit, with only a small handful of British soldiers present within its ranks. These would have included men from the Royal Corps of Signals, 142 Commando and the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, Tom's probable unit.

Chindit Column 1 was led by Major George Dunlop MC, formerly of the Royal Scots. This column was part of Southern Section in 1943 and acted as a decoy for Northern Group which included Brigadier Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters and columns 3, 4, 5, 7 and 8. Dunlop's unit was to have a torrid time inside Burma that year and found itself the furthest from the safety of Allied held territory when dispersal was called in late March. For more information about 1 Column and their journey back to India in 1943, please use the search box found in the top right hand corner of every page on this website, using such terminology as 1 Column or Major Dunlop.

Tom Gilzean is a well loved character on the streets of Edinburgh and is perhaps best known for his relentless fundraising for various charities. In March 2015 his efforts were again recognised and he was awarded the coveted 'Edinburgh Award' from the people of his hometown.

From the Edinburgh Evening News, dated 17th March 2015 and written by journalist John Connell:

Fundraising war veteran Tom Gilzean has become the eighth person to be honoured with the coveted Edinburgh Award.

The 94-year-old stalwart was presented with an engraved Loving Cup by the Lord Provost at the City Chambers to mark his outstanding contribution to charity. He follows in the footsteps of the likes of Ian Rankin, J.K. Rowling and Sir Chris Hoy – but is the first recipient to be honoured for charity work and philanthropy.

The retired bus driver, who started collecting for charity to stave off depression following the death of his wife of 55 years, said he had raised more than £300,000 – three times as much as previously thought. Every day he can be found in his signature tartan trousers on the Royal Mile or Princes Street in rain or shine collecting for his chosen charities, including the Sick Kids.

He has been awarded several honours, including the British Empire Medal by the Queen in 2013. But Tom insisted that receiving the Edinburgh Award was his “proudest moment” because it was given to him by the people of his home city.

“Edinburgh and surrounding parts are very good to me, they look after me in every way,” he said during last night’s ceremony.

“Don’t think I’m not grateful. Edinburgh people are the salt of the earth when it comes to collecting for charities."

“Believe me, they give with their heart as I call out for their pennies.”

An impression of Tom’s handprints has been immortalised on a flagstone outside the City Chambers alongside those of previous Edinburgh Award recipients, including Richard Demarco, George Kerr, Professor Peter Higgs and Elizabeth Blackadder.

“I am in good company and it makes me feel very humble to be included alongside them,” said Tom.

Among the highlights of the night was Rachel McKenzie, head of voluntary fundraising at the Sick Kids Friends Foundation, telling the assembled guests if it was possible to “bottle Tom and sell him” they could fully fund his favourite charities for many years to come.

Christine De Luca, the Edinburgh Makar (poet), recited a poem composed especially for the occasion in which she said Tom was still on parade tirelessly collecting for charity. Councillor Donald Wilson, the Lord Provost, said: “Tom Gilzean is a familiar face on the High Street and is well known for being out in all weathers, come rain or shine. His sense of service and dedication to others make him a fantastic role model and a tremendous recipient of the Edinburgh Award."

Tom’s daughter Maureen, who travelled from Spain especially for the ceremony, said the whole family were very proud of him. His charities include the Sick Kids Friends Foundation, the Armed Forces Personnel Recovery Centre and the Edinburgh Taxi Trade Children’s Outing.

Tom was a former soldier with the Royal Engineers in WW2 where he faced Rommel’s Afrika Korps in the North African Desert, the Imperial Japanese Army in Burma and Hitler’s Wehrmacht in France.

For more information about his presentation of the Edinburgh Award and Tom's views on receiving this well deserved prize, please click on the link below:

http://www.edinburghnews.scotsman.com/news/tom-gilzean-presented-with-edinburgh-award-1-3720268

Copyright © Steve Fogden and John Connell, November 2015.

A good friend of mine recently moved home up to Scotland. On one of his first visits to Edinburgh he bumped into Tom Gilzean. Tom told him that he had served in Burma, including on the first Chindit operation where he served in Chindit Column 1 as an engineer attachment. This news was of great interest to me, as up till then I had not been aware of Tom's involvement on Operation Longcloth.

1 Column was in the majority a Gurkha unit, with only a small handful of British soldiers present within its ranks. These would have included men from the Royal Corps of Signals, 142 Commando and the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, Tom's probable unit.

Chindit Column 1 was led by Major George Dunlop MC, formerly of the Royal Scots. This column was part of Southern Section in 1943 and acted as a decoy for Northern Group which included Brigadier Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters and columns 3, 4, 5, 7 and 8. Dunlop's unit was to have a torrid time inside Burma that year and found itself the furthest from the safety of Allied held territory when dispersal was called in late March. For more information about 1 Column and their journey back to India in 1943, please use the search box found in the top right hand corner of every page on this website, using such terminology as 1 Column or Major Dunlop.

Tom Gilzean is a well loved character on the streets of Edinburgh and is perhaps best known for his relentless fundraising for various charities. In March 2015 his efforts were again recognised and he was awarded the coveted 'Edinburgh Award' from the people of his hometown.

From the Edinburgh Evening News, dated 17th March 2015 and written by journalist John Connell:

Fundraising war veteran Tom Gilzean has become the eighth person to be honoured with the coveted Edinburgh Award.

The 94-year-old stalwart was presented with an engraved Loving Cup by the Lord Provost at the City Chambers to mark his outstanding contribution to charity. He follows in the footsteps of the likes of Ian Rankin, J.K. Rowling and Sir Chris Hoy – but is the first recipient to be honoured for charity work and philanthropy.

The retired bus driver, who started collecting for charity to stave off depression following the death of his wife of 55 years, said he had raised more than £300,000 – three times as much as previously thought. Every day he can be found in his signature tartan trousers on the Royal Mile or Princes Street in rain or shine collecting for his chosen charities, including the Sick Kids.

He has been awarded several honours, including the British Empire Medal by the Queen in 2013. But Tom insisted that receiving the Edinburgh Award was his “proudest moment” because it was given to him by the people of his home city.

“Edinburgh and surrounding parts are very good to me, they look after me in every way,” he said during last night’s ceremony.

“Don’t think I’m not grateful. Edinburgh people are the salt of the earth when it comes to collecting for charities."

“Believe me, they give with their heart as I call out for their pennies.”

An impression of Tom’s handprints has been immortalised on a flagstone outside the City Chambers alongside those of previous Edinburgh Award recipients, including Richard Demarco, George Kerr, Professor Peter Higgs and Elizabeth Blackadder.

“I am in good company and it makes me feel very humble to be included alongside them,” said Tom.

Among the highlights of the night was Rachel McKenzie, head of voluntary fundraising at the Sick Kids Friends Foundation, telling the assembled guests if it was possible to “bottle Tom and sell him” they could fully fund his favourite charities for many years to come.

Christine De Luca, the Edinburgh Makar (poet), recited a poem composed especially for the occasion in which she said Tom was still on parade tirelessly collecting for charity. Councillor Donald Wilson, the Lord Provost, said: “Tom Gilzean is a familiar face on the High Street and is well known for being out in all weathers, come rain or shine. His sense of service and dedication to others make him a fantastic role model and a tremendous recipient of the Edinburgh Award."

Tom’s daughter Maureen, who travelled from Spain especially for the ceremony, said the whole family were very proud of him. His charities include the Sick Kids Friends Foundation, the Armed Forces Personnel Recovery Centre and the Edinburgh Taxi Trade Children’s Outing.

Tom was a former soldier with the Royal Engineers in WW2 where he faced Rommel’s Afrika Korps in the North African Desert, the Imperial Japanese Army in Burma and Hitler’s Wehrmacht in France.

For more information about his presentation of the Edinburgh Award and Tom's views on receiving this well deserved prize, please click on the link below:

http://www.edinburghnews.scotsman.com/news/tom-gilzean-presented-with-edinburgh-award-1-3720268

Copyright © Steve Fogden and John Connell, November 2015.

Cyril Askew.

Cyril Askew.

Cyril Askew

Cyril Askew is 98 years old (August 2015) and is the oldest living veteran of the King's Liverpool Regiment. Although he did technically serve with the 13th Battalion whilst in India during WW2 and as such qualifies to be mentioned on this website, it is unlikely that he took part on Operation Longcloth. He joined up in 1935 for the normal service period of 7 years and was originally allocated to the 1st King's. However, after his initial basic training was over, Cyril was posted to the 2nd Battalion who were then based overseas in India.

The 2 KLR were serving on the North West Frontier of the country, nowadays this area forms the border of Pakistan and Afghanistan. The battalion were part of a peace-keeping force in this rugged and mountainous terrain, checking up on the movements of the local Pathan tribesmen who were notorious for their incursions into British territory and for their raids on passing trade caravans.

By 1942, Cyril had moved over to the 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment who had recently arrived from the United Kingdom. It is possible that he joined the 13th King's at their new home at Secunderabad. From his own personal memoirs, Cyril describes the arrival of Major-General Wingate and the preparations for the second Chindit operation in 1944. He then describes being placed under the command of Brigadier Mike Calvert and learning that his unit were to be dropped into Burma by glider.

As fate would have it, Cyril never flew into Burma that year. Amazingly he was told that his seven years service was up and that he was now due to be sent home. His troopship sailed from Bombay and fortunately was able to use the newly re-opened Suez Canal, arriving home at Liverpool in early 1944. He was sent to join the 9th King's at their base in the Mountains of Mourne in Ireland. Within a few short weeks, Cyril was posted to the 2nd Battalion of the Lincolnshire Regiment which became part of the 3rd British Division that landed on Sword Beach as part of the D-Day Allied invasion of France.

To read more about Cyril Askew and his long period in the British Army, please click on the following link: http://d-dayrevisited.co.uk/veterans/cyril-askew.html