Captain Williams and Platoon 18

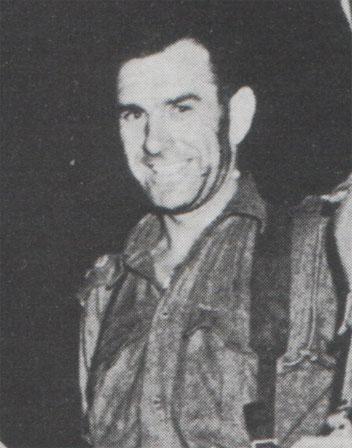

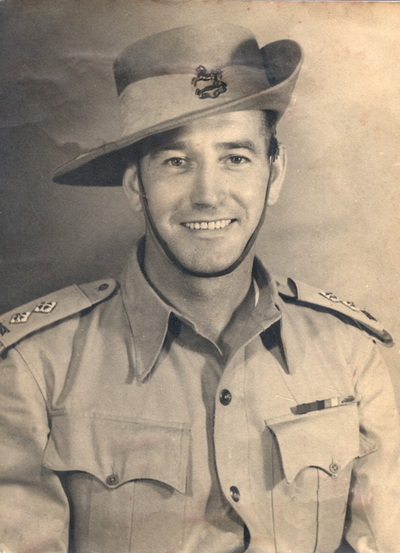

Raymond Edward Williams, Colchester 1941.

Raymond Edward Williams, Colchester 1941.

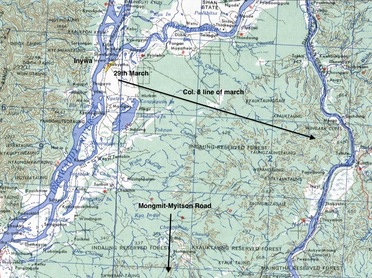

On the 29th March 1943 three Chindit Columns massed on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River near the town of Inywa. The idea was to get across this wide expanse of water as quickly as possible and then, once over, move off westwards and return to India.

Unfortunately, the crossing was contested by a large patrol of Japanese soldiers positioned on the opposite banks of the river. The men in the leading boats soon came under severe machine gun and mortar fire, resulting in many casualties. Wingate, after a speedy consultation with his column commanders, decided to call off the crossing and the dispirited Chindits melted away into the jungle.

Major Scott, the commander of Column 8 led his men away from Inywa that day and for the most part headed in a south-easterly direction. The Chindits now found themselves back in what they called the 'Irrawaddy/Shweli Bag'. This was basically an area of country surrounded on three sides by the two fast flowing Burmese Rivers, with the Mong Mit-Myitson motor road forming the southern entrance of the bag.

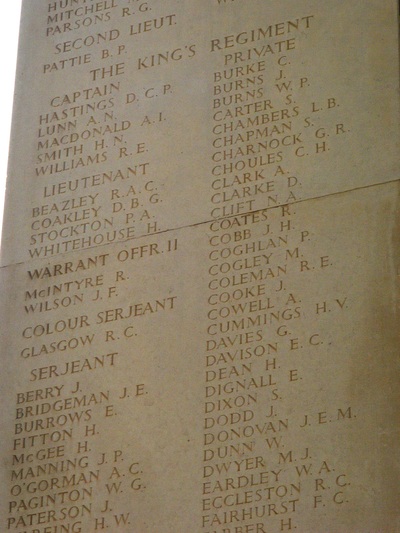

This is the chronological story of one group of men from Column 8, who would suffer greatly from the failure to cross the Irrawaddy on the 29th. The unit was Platoon 18 commanded by Captain Raymond Edward Williams of the 13th King's and the second officer in Column 8 under Major Scott.

Before we move on to describe the events that befell the ill-fated platoon in April 1943, we should perhaps learn more about the man who led them.

Raymond Edward Williams was born in the town of Bridgnorth, Shropshire in 1910, the youngest child of Joseph and Louise Williams. After excelling at school, he took a job at the Lever Brother's Soap factory in 'Port Sunlight' Birkenhead, near Liverpool. Raymond lived in Heath Hey, Puddington, Cheshire, in a home he shared with his wife, Ingrid Matilda.

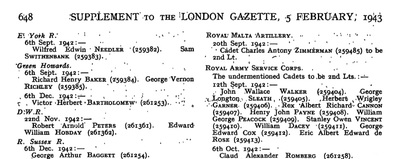

Raymond, although an original member of the 13th King's battalion that journeyed to India aboard the troopship 'Oronsay' in December 1941, was formerly with the Royal Artillery and had been posted to the 13th King's at Felixstowe in December 1940. He soon proved his worth and leadership qualities, and also formed a strong friendship with Walter Purcell Scott, who was to become his Column Commander in Burma. In preparation for the battalion's move to Liverpool Docks and embarkation aboard the 'Oronsay', Captain Williams was placed in charge of the advance party and sent to make the arrangements for the voyage.

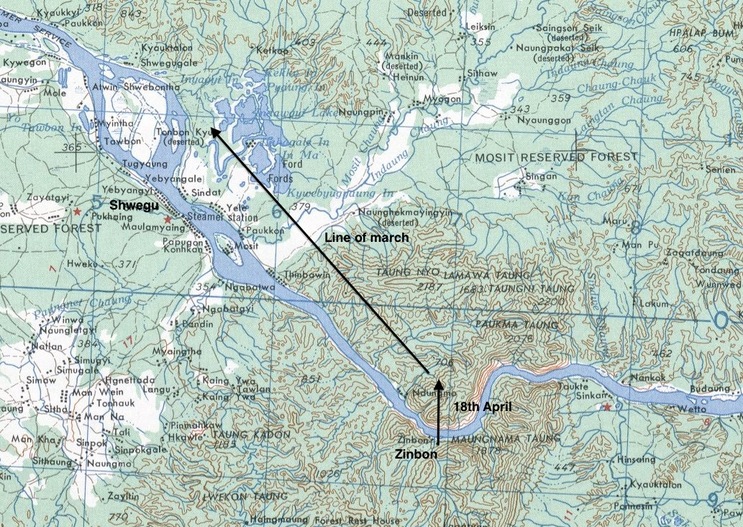

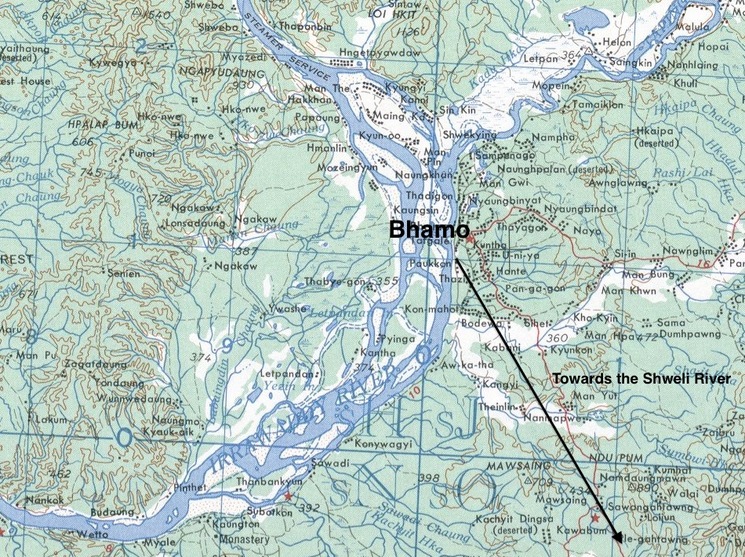

Seen below are two maps showing Column 8's movements after the compromised crossing of the Irrawaddy River on 29th March 1943. Please click on each image to bring them forward on the page.

Unfortunately, the crossing was contested by a large patrol of Japanese soldiers positioned on the opposite banks of the river. The men in the leading boats soon came under severe machine gun and mortar fire, resulting in many casualties. Wingate, after a speedy consultation with his column commanders, decided to call off the crossing and the dispirited Chindits melted away into the jungle.

Major Scott, the commander of Column 8 led his men away from Inywa that day and for the most part headed in a south-easterly direction. The Chindits now found themselves back in what they called the 'Irrawaddy/Shweli Bag'. This was basically an area of country surrounded on three sides by the two fast flowing Burmese Rivers, with the Mong Mit-Myitson motor road forming the southern entrance of the bag.

This is the chronological story of one group of men from Column 8, who would suffer greatly from the failure to cross the Irrawaddy on the 29th. The unit was Platoon 18 commanded by Captain Raymond Edward Williams of the 13th King's and the second officer in Column 8 under Major Scott.

Before we move on to describe the events that befell the ill-fated platoon in April 1943, we should perhaps learn more about the man who led them.

Raymond Edward Williams was born in the town of Bridgnorth, Shropshire in 1910, the youngest child of Joseph and Louise Williams. After excelling at school, he took a job at the Lever Brother's Soap factory in 'Port Sunlight' Birkenhead, near Liverpool. Raymond lived in Heath Hey, Puddington, Cheshire, in a home he shared with his wife, Ingrid Matilda.

Raymond, although an original member of the 13th King's battalion that journeyed to India aboard the troopship 'Oronsay' in December 1941, was formerly with the Royal Artillery and had been posted to the 13th King's at Felixstowe in December 1940. He soon proved his worth and leadership qualities, and also formed a strong friendship with Walter Purcell Scott, who was to become his Column Commander in Burma. In preparation for the battalion's move to Liverpool Docks and embarkation aboard the 'Oronsay', Captain Williams was placed in charge of the advance party and sent to make the arrangements for the voyage.

Seen below are two maps showing Column 8's movements after the compromised crossing of the Irrawaddy River on 29th March 1943. Please click on each image to bring them forward on the page.

"God speed and fewer better fare."

This was the cryptic message received by Major Scott on the 1st April from Brigadier Wingate. It was simply advising the Chindit Column Commanders to break their units up into small dispersal parties, as, in Wingate's view, these stood a far greater chance of dodging the numerous Japanese patrols in the immediate area and successfully returning to India.

Scott's most heartfelt wish was to keep his Column together and return to India as one unit. As the next few weeks passed by, this proved to be an impossibility. It should also be noted that from this point on, Northern Group Head Quarters under the overall command of Lieutenant-Colonel Cooke effectively became part of Column 8 and travelled with Major Scott.

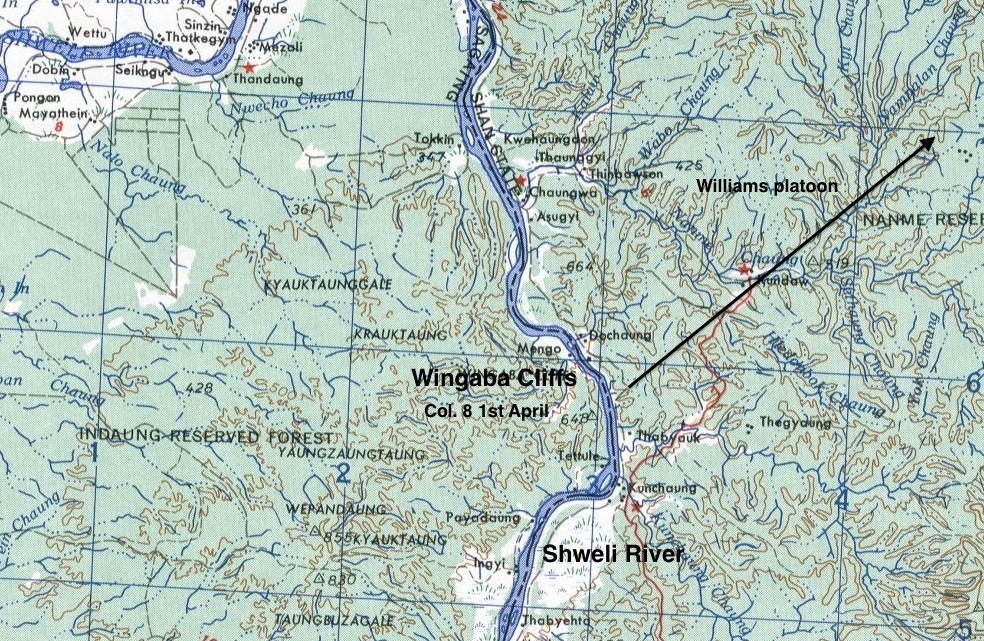

Columns 7 and 8 were ordered to march south-easterly towards the Shweli River and to attempt a crossing in the area around the Wingba Cliffs.

From the War diary of Column 8 dated 1st April 1943:

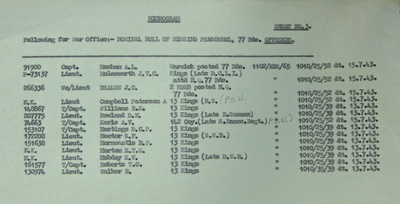

"Recce of the River Shweli carried out during the afternoon and we have decided to cross this evening near the Wingaba Cliffs, S.N. 2563. Column moved down to the river at dusk. Rope got across the river which was flowing very fast on the near side. Captain Williams with two other officers, Lieutenants Hobday and Horton and 29 British Other Ranks crossed the river to form a bridgehead. The next party under Sgt. Scruton got in to difficulties and drifted away down-stream. Both boats having been lost, the crossing was called off. Captain Williams and his party moved from the far bank at first light for the next agreed rendezvous. The rope across the river was withdrawn."

To read more about what happened to Sgt. Stanley Scruton and his group, please click on the following link:

Eric Allen and the Lost Boat on the Shweli

In the book 'With Wingate in Burma', by David Halley, there is a first hand account describing the moment the RAF dinghies were lost on the 1st April. The incident was remembered by Sgt. Tony Aubrey, also a member of Column 8 in 1943. Aubrey recalled:

"We reached the Shweli River shortly after nightfall, and received orders to have a meal and rest for a couple of hours, preparatory to making the crossing at moonrise.

The Shweli River here is about 180 yards across. The banks are of soft sand, gently sloping. The first fifty yards of water from the southern bank (on which, of course, we were) are very deep and the current is fast, flowing at a good four knots. Then comes a sandbank, several feet clear of the water, and beyond that the remaining hundred yards is only waist deep, and quite fordable.

Before the crossing started, there were one or two preliminary jobs to be done. First, the deep part of the river must be swum, with pegs and a rope, in order to make an endless pulley-rope on which our rubber dinghies could be operated. We had, I should mention, only four of these with us, but that number should be easily sufficient though the crossing would be fairly slow, each dinghy only carrying six men.

I hoped to be allowed to take my part in the swimming, but my shoulder, though healing rapidly, was not altogether well yet, and I was forced to be a spectator. As always when volunteers were wanted, the difficulty was, not to get sufficient but to choose the number you wanted without giving too much offence to those you refused. However, those chosen stripped to the skin, and succeeded in safely ferrying the rope and the stakes out to the sandbar, which was as far as it would be necessary for us to use the dinghies.

These men were some of our strongest swimmers, and it was quite clear from the comparatively heavy weather they made of the trip that the ordinary man, laden with rifle and pack, would not have a hope in hell of getting over. Without our rubber dinghies we should have been, quite literally, sunk.

The rope was duly passed on pulleys round the stakes, the dinghies were attached by smaller ropes and a running noose to the parent rope, and the ropeway was ready.

To Captain Williams was given the task of taking his platoon across first. At moonrise the first twelve men, the Captain included, took their places in the dinghies, and the crossing began. At first all went well. They pulled themselves across hand over hand, and as they went over, the empty dinghies on the other reach of the ropeway came back, received their complement of men, and were in turn handed across. The only pauses were occasioned as each dinghy reached a spot where there was a large knot in the rope. Over this the slip-knot of the tie-ropes had to be lifted and eased every time, an annoying but unavoidable delay.

My mother used to tell me a tale of an old man who was her father's gardener. This amiable old gentleman was alleged to have been given the task of cutting a large branch from one of his employer's apple trees. He duly climbed the tree, sat himself down upon the end of the branch in question, and proceeded to saw it clean off between himself and the trunk. Not unnaturally, he fell, and broke both his venerable legs. I had always been inclined to look upon this tale as a flight of fancy. But in view of what I saw happen next, I am now inclined to think that there may have been some truth in it after all.

About thirty-five men had made the sandbank in safety, and there appeared to be no reason why the rest of us should not follow them as per schedule, when one of the dinghies, manned by a sergeant and six privates, reached the point where was the aforementioned knot. As usual, the noose refused to pass over it. This particular sergeant evidently considered he knew a thing or two more than those who had gone before. Why waste time fiddling about when there was a much more direct method available for dealing with this obtrusive knot. He raised his dha, and before anyone could stop him had struck the knot off the rope with one fell sweep.

Into the water fell the rope. Down stream at a hearty four knots disappeared one sergeant and eleven other ranks and what was at this moment more important, our only four rubber dinghies, worth to us at this juncture considerably more than their weight in any precious metal you care to mention.

For a minute or two there was a stupefied silence. It was the sort of disaster which leaves you utterly speechless. Then the dams broke, and I think it was as well for that sergeant, poor fellow, that he was at that moment being carried away to an extremely uncertain fate on the inhospitable waters of the river, rather than here with his mates.

The flood of fury was soon over. What can't be cured must be endured. Our boats were gone, and that was the end of that. Major Scott gave Captain Williams, gibbering with fury on the sandbank, instructions to treat the men he had with him as a separate command and be on his way. We shouted good wishes across the stream, and they went. And that was the last we saw of them."

This was the cryptic message received by Major Scott on the 1st April from Brigadier Wingate. It was simply advising the Chindit Column Commanders to break their units up into small dispersal parties, as, in Wingate's view, these stood a far greater chance of dodging the numerous Japanese patrols in the immediate area and successfully returning to India.

Scott's most heartfelt wish was to keep his Column together and return to India as one unit. As the next few weeks passed by, this proved to be an impossibility. It should also be noted that from this point on, Northern Group Head Quarters under the overall command of Lieutenant-Colonel Cooke effectively became part of Column 8 and travelled with Major Scott.

Columns 7 and 8 were ordered to march south-easterly towards the Shweli River and to attempt a crossing in the area around the Wingba Cliffs.

From the War diary of Column 8 dated 1st April 1943:

"Recce of the River Shweli carried out during the afternoon and we have decided to cross this evening near the Wingaba Cliffs, S.N. 2563. Column moved down to the river at dusk. Rope got across the river which was flowing very fast on the near side. Captain Williams with two other officers, Lieutenants Hobday and Horton and 29 British Other Ranks crossed the river to form a bridgehead. The next party under Sgt. Scruton got in to difficulties and drifted away down-stream. Both boats having been lost, the crossing was called off. Captain Williams and his party moved from the far bank at first light for the next agreed rendezvous. The rope across the river was withdrawn."

To read more about what happened to Sgt. Stanley Scruton and his group, please click on the following link:

Eric Allen and the Lost Boat on the Shweli

In the book 'With Wingate in Burma', by David Halley, there is a first hand account describing the moment the RAF dinghies were lost on the 1st April. The incident was remembered by Sgt. Tony Aubrey, also a member of Column 8 in 1943. Aubrey recalled:

"We reached the Shweli River shortly after nightfall, and received orders to have a meal and rest for a couple of hours, preparatory to making the crossing at moonrise.

The Shweli River here is about 180 yards across. The banks are of soft sand, gently sloping. The first fifty yards of water from the southern bank (on which, of course, we were) are very deep and the current is fast, flowing at a good four knots. Then comes a sandbank, several feet clear of the water, and beyond that the remaining hundred yards is only waist deep, and quite fordable.

Before the crossing started, there were one or two preliminary jobs to be done. First, the deep part of the river must be swum, with pegs and a rope, in order to make an endless pulley-rope on which our rubber dinghies could be operated. We had, I should mention, only four of these with us, but that number should be easily sufficient though the crossing would be fairly slow, each dinghy only carrying six men.

I hoped to be allowed to take my part in the swimming, but my shoulder, though healing rapidly, was not altogether well yet, and I was forced to be a spectator. As always when volunteers were wanted, the difficulty was, not to get sufficient but to choose the number you wanted without giving too much offence to those you refused. However, those chosen stripped to the skin, and succeeded in safely ferrying the rope and the stakes out to the sandbar, which was as far as it would be necessary for us to use the dinghies.

These men were some of our strongest swimmers, and it was quite clear from the comparatively heavy weather they made of the trip that the ordinary man, laden with rifle and pack, would not have a hope in hell of getting over. Without our rubber dinghies we should have been, quite literally, sunk.

The rope was duly passed on pulleys round the stakes, the dinghies were attached by smaller ropes and a running noose to the parent rope, and the ropeway was ready.

To Captain Williams was given the task of taking his platoon across first. At moonrise the first twelve men, the Captain included, took their places in the dinghies, and the crossing began. At first all went well. They pulled themselves across hand over hand, and as they went over, the empty dinghies on the other reach of the ropeway came back, received their complement of men, and were in turn handed across. The only pauses were occasioned as each dinghy reached a spot where there was a large knot in the rope. Over this the slip-knot of the tie-ropes had to be lifted and eased every time, an annoying but unavoidable delay.

My mother used to tell me a tale of an old man who was her father's gardener. This amiable old gentleman was alleged to have been given the task of cutting a large branch from one of his employer's apple trees. He duly climbed the tree, sat himself down upon the end of the branch in question, and proceeded to saw it clean off between himself and the trunk. Not unnaturally, he fell, and broke both his venerable legs. I had always been inclined to look upon this tale as a flight of fancy. But in view of what I saw happen next, I am now inclined to think that there may have been some truth in it after all.

About thirty-five men had made the sandbank in safety, and there appeared to be no reason why the rest of us should not follow them as per schedule, when one of the dinghies, manned by a sergeant and six privates, reached the point where was the aforementioned knot. As usual, the noose refused to pass over it. This particular sergeant evidently considered he knew a thing or two more than those who had gone before. Why waste time fiddling about when there was a much more direct method available for dealing with this obtrusive knot. He raised his dha, and before anyone could stop him had struck the knot off the rope with one fell sweep.

Into the water fell the rope. Down stream at a hearty four knots disappeared one sergeant and eleven other ranks and what was at this moment more important, our only four rubber dinghies, worth to us at this juncture considerably more than their weight in any precious metal you care to mention.

For a minute or two there was a stupefied silence. It was the sort of disaster which leaves you utterly speechless. Then the dams broke, and I think it was as well for that sergeant, poor fellow, that he was at that moment being carried away to an extremely uncertain fate on the inhospitable waters of the river, rather than here with his mates.

The flood of fury was soon over. What can't be cured must be endured. Our boats were gone, and that was the end of that. Major Scott gave Captain Williams, gibbering with fury on the sandbank, instructions to treat the men he had with him as a separate command and be on his way. We shouted good wishes across the stream, and they went. And that was the last we saw of them."

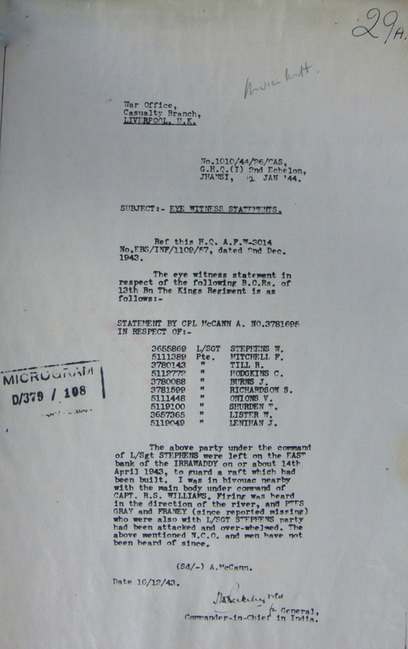

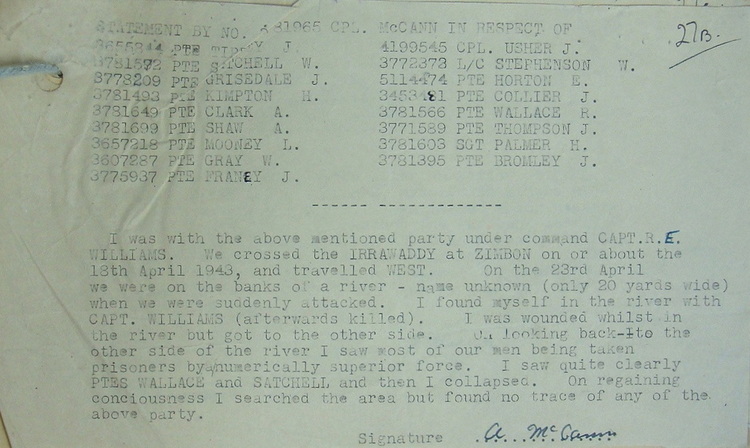

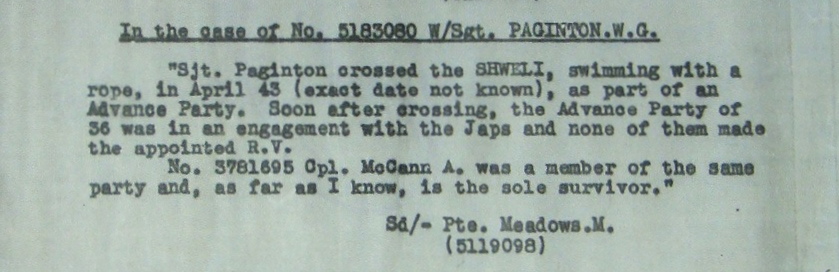

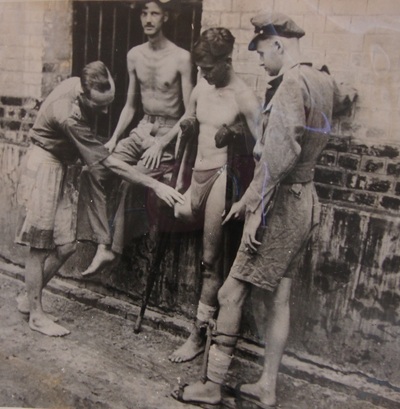

Apart from the memoirs of Sgt. Aubrey found within the pages of Halley's book, very little else exists in the way of information in regard to the fate of Captain Williams and Platoon 18. There are in fact only three short witness statements to work with in this regard, these were provided by the only member of the platoon to make the journey back to India that year; Corporal 3781695 A. McCann.

McCann's statements tell the story of the platoon's journey after the Shweli debacle and their march north-east towards the Irrawaddy for a second time. They also describe at least two engagements with the Japanese along the way, although at times his accounts to seem to contradict each other. Corporal McCann also features in Halley's book, where he describes the final moments of the platoon as a cohesive unit and the fate of their leader Captain Williams.

Using Corporal McCann's witness statements and the relevant sections from 'With Wingate in Burma', I hope to trace the platoon's steps in April 1943 and using considered and hopefully educated evaluation deliver a possible scenario of what happened.

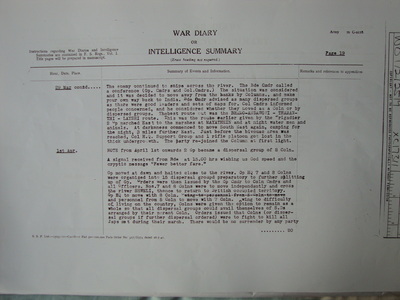

The first statement (seen above, please click on the image to enlarge) was given by McCann to the investigation bureau set up to collate and identify the missing men of Operation Longcloth. The statement, given on the 16th December 1943, deals with an incident on the 14th April when part of the platoon were attacked by the enemy on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy. He lists the men involved who were under the command of Lance Sergeant William Stephens. McCann stated:

"The above party under the command of L/Sgt. Stephens were left on the east bank of the Irrawaddy on about the 14th April 1943, to guard a raft that had been built. I was in bivouac with the main body, under the command of Captain R. Williams. Firing was heard in the direction of the river, and Ptes. Gray and Franey (since reported missing) who were also with Stephens party had been attacked and overwhelmed. The above NCO and men have not been heard of since."

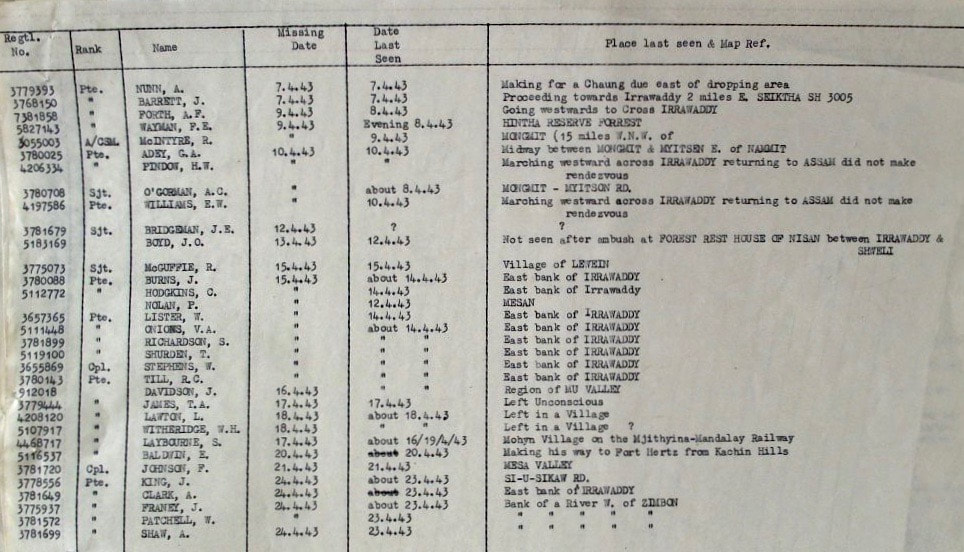

Listed in the order on McCann's statement, here is the fate of each member of Lance Sergeant Stephen's party:

McCann's statements tell the story of the platoon's journey after the Shweli debacle and their march north-east towards the Irrawaddy for a second time. They also describe at least two engagements with the Japanese along the way, although at times his accounts to seem to contradict each other. Corporal McCann also features in Halley's book, where he describes the final moments of the platoon as a cohesive unit and the fate of their leader Captain Williams.

Using Corporal McCann's witness statements and the relevant sections from 'With Wingate in Burma', I hope to trace the platoon's steps in April 1943 and using considered and hopefully educated evaluation deliver a possible scenario of what happened.

The first statement (seen above, please click on the image to enlarge) was given by McCann to the investigation bureau set up to collate and identify the missing men of Operation Longcloth. The statement, given on the 16th December 1943, deals with an incident on the 14th April when part of the platoon were attacked by the enemy on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy. He lists the men involved who were under the command of Lance Sergeant William Stephens. McCann stated:

"The above party under the command of L/Sgt. Stephens were left on the east bank of the Irrawaddy on about the 14th April 1943, to guard a raft that had been built. I was in bivouac with the main body, under the command of Captain R. Williams. Firing was heard in the direction of the river, and Ptes. Gray and Franey (since reported missing) who were also with Stephens party had been attacked and overwhelmed. The above NCO and men have not been heard of since."

Listed in the order on McCann's statement, here is the fate of each member of Lance Sergeant Stephen's party:

William Stephens.

William Stephens.

Lance Sergeant William Stephens. Possibly captured after the ambush on the 14th April, recorded as having died on the 1st August 1943. William may well have perished in one of the POW camps such as Maymyo, before the main body of Chindit prisoners were moved down to Rangoon.

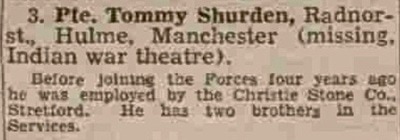

From the pages of the Liverpool Evening Express dated Thursday 26th August 1943 and under the headline, Roll of Honour:

Sergeant William Stephens, aged 24, of Gee Street in Warrington is reported missing in an overseas theatre of war. He has played for Warrington and Rochdale Hornets rugby league clubs and was Captain of an Army divisional team which won a shield and medals at Aldershot.

Pte. Frank Mitchell. Son of Rhoda Mitchell; foster-son of Sarah Jane Tysall, of Erdington, Birmingham. Frank was captured on the 14th and ended up a prisoner in Rangoon Jail. He sadly died, possibly suffering from beri beri and dysentery, on the 31st August 1943 in Block 6 of the jail, he was given the POW number 583 and was buried in the English Cantonment Cemetery.

Pte. Richard Cookson Till. The son of Thomas and Ellen Till from Preesall in Lancashire. Richard was killed in action during the Japanese attack on the 14th, although the CWGC record his death as the 15th April.

From the pages of the Liverpool Evening Express dated Thursday 26th August 1943 and under the headline, Roll of Honour:

Sergeant William Stephens, aged 24, of Gee Street in Warrington is reported missing in an overseas theatre of war. He has played for Warrington and Rochdale Hornets rugby league clubs and was Captain of an Army divisional team which won a shield and medals at Aldershot.

Pte. Frank Mitchell. Son of Rhoda Mitchell; foster-son of Sarah Jane Tysall, of Erdington, Birmingham. Frank was captured on the 14th and ended up a prisoner in Rangoon Jail. He sadly died, possibly suffering from beri beri and dysentery, on the 31st August 1943 in Block 6 of the jail, he was given the POW number 583 and was buried in the English Cantonment Cemetery.

Pte. Richard Cookson Till. The son of Thomas and Ellen Till from Preesall in Lancashire. Richard was killed in action during the Japanese attack on the 14th, although the CWGC record his death as the 15th April.

Pte. Cyril Hodgkins. The son of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Hodgkins, from Short Heath in Birmingham. Cyril was also killed in action during the Japanese attack on the 14th, the CWGC also record his death as being on the 15th April.

Pte. James Burns. The son of John and Kathrine Burns, and husband of Doris Burns from Moss Side in Manchester. James was killed in action during the ambush on the Irrawaddy, the CWGC record his date of death as the 15th April 1943.

Pte. Samuel Richardson. The son of John William and Alice Richardson, husband of G.S. Richardson of Droylsden in Lancashire. Samuel also died on the 14th April according to McCann's witness statement, although, like all the other casualties listed, the CWGC record the date of death as the 15th.

Pte. James Burns. The son of John and Kathrine Burns, and husband of Doris Burns from Moss Side in Manchester. James was killed in action during the ambush on the Irrawaddy, the CWGC record his date of death as the 15th April 1943.

Pte. Samuel Richardson. The son of John William and Alice Richardson, husband of G.S. Richardson of Droylsden in Lancashire. Samuel also died on the 14th April according to McCann's witness statement, although, like all the other casualties listed, the CWGC record the date of death as the 15th.

A young Vincent Onions.

A young Vincent Onions.

Pte. Vincent Alfred Onions. The son of Mr. and Mrs. W. Onions from Hartshill in Warwickshire. Vincent was recorded as missing after the ambush on the 14th, he is not mentioned as being held prisoner in any documents relating to the Chindits in 1943, but it is my guess that he was a POW for a short while, before possibly dying of wounds suffered during the action at the Irrawaddy.

From the Hartshill Herald newspaper dated April 20th 1946 and under the headline, Atherstone Roll of Honour:

The committee of the Atherstone Ex-Servicemen's Club have announced their intention of placing a memorial in the club building to those who fell in the 1939-45 war. The memorial will follow the same design as the 1914-18 tribute. A Roll of honour has been compiled and it includes the following names: (the article then goes on to list around 40 local casualties to all three services who were lost during WW2, this listing includes Vincent Onions' name).

The image of Vincent as a young man was found in a collection of papers and photographs purchased by fellow WW2 researcher, Simon Jervis in early May 2021.

From the Hartshill Herald newspaper dated April 20th 1946 and under the headline, Atherstone Roll of Honour:

The committee of the Atherstone Ex-Servicemen's Club have announced their intention of placing a memorial in the club building to those who fell in the 1939-45 war. The memorial will follow the same design as the 1914-18 tribute. A Roll of honour has been compiled and it includes the following names: (the article then goes on to list around 40 local casualties to all three services who were lost during WW2, this listing includes Vincent Onions' name).

The image of Vincent as a young man was found in a collection of papers and photographs purchased by fellow WW2 researcher, Simon Jervis in early May 2021.

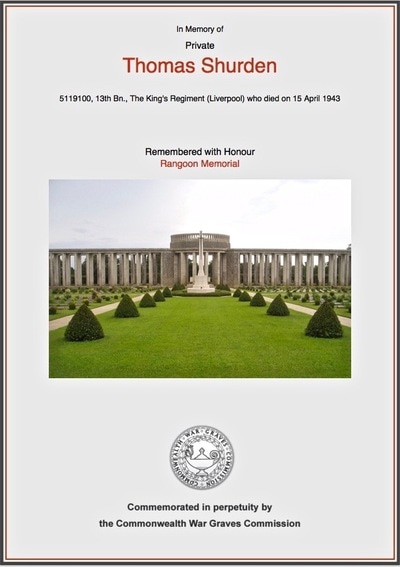

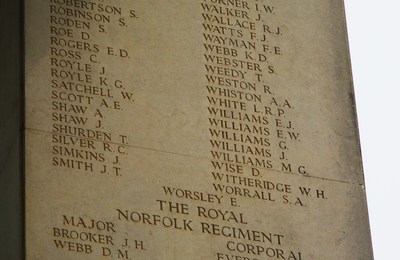

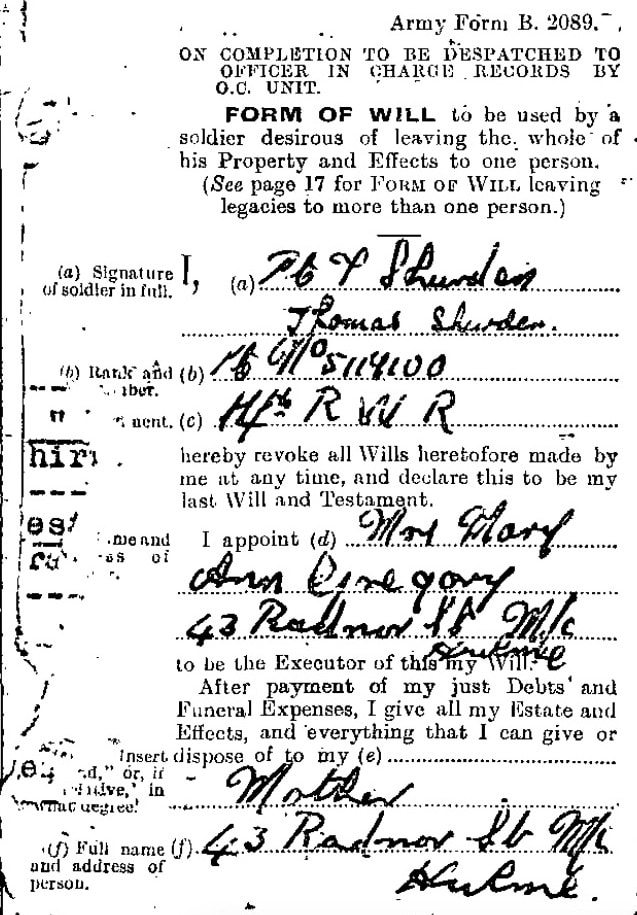

Pte. Thomas Shurden. Thomas also died on the 14th April according to McCann's witness statement, although, like all the other casualties listed by McCann, the CWGC record the date of death as the 15th. Please see the update about Thomas further down this page.

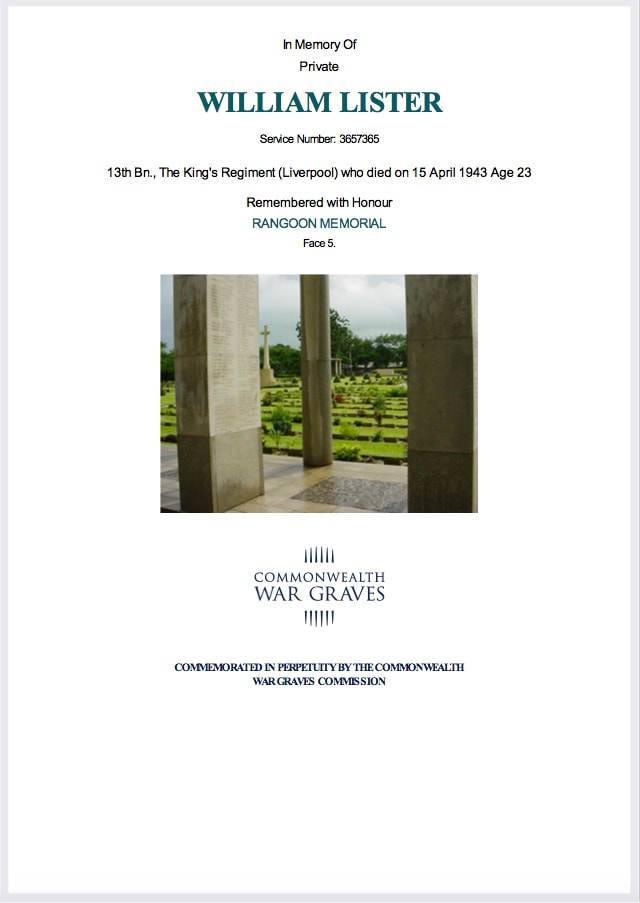

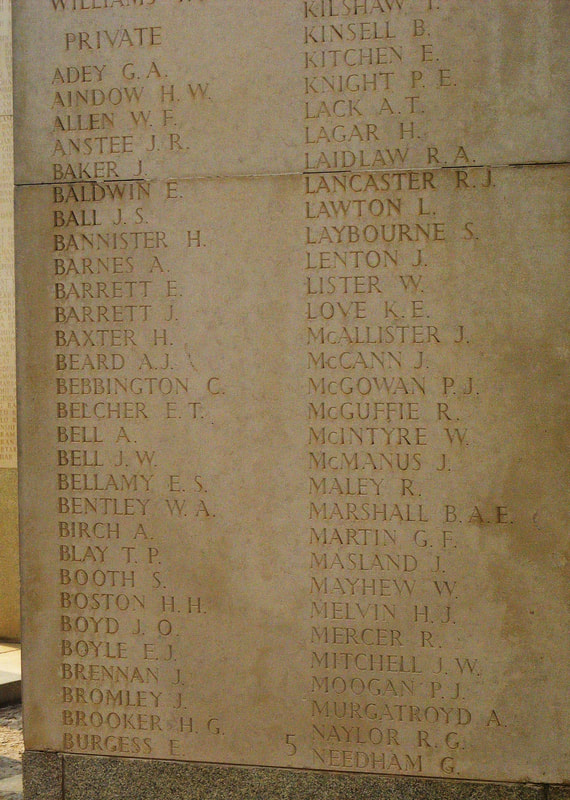

Pte. William Lister. William was killed in action during the ambush on the Irrawaddy, the CWGC record his date of death as the 15th April 1943.

Update 12/04/2021.

I was pleased to receive the following email contact in relation to William Lister from his niece, Marylyn Walton:

I am looking for information regarding my uncle William Lister, Army number 3657365, who was killed on the 25th April 1943 in Burma. He was a soldier in the King's Regiment. He was the brother of my mother May Finnegan nee Lister. Our family have no information on how he died. I have been researching for years, but there have been no published facts on his death, not even a record of any medals issued or if he had friends in his battalion. My brother Bill was named after my uncle and he has visited the cemetery in Rangoon which shows just his name. We have no stories about his time in the Army or in Burma. Is there any information that you could forward to me to enable me to share with my family? Kind regards, Marylyn.

I replied:

Dear Marylyn,

Thank you for your recent email contact via my website in relation to William Lister. I do have some information about William and how he died in Burma in April 1943. This is what I can tell you about his time with the Chindits.

His Army service number comes from the allocation for the Prince of Wales' Volunteers, the South Lancashire Regiment and it is likely that he was with this regiment at the beginning of his WW2 service. He would have been in India by mid-1942 at the latest and after his transfer to the 13th Battalion, the King's Regiment, William was posted to No. 8 (Chindit) Column, under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott. This was the unit he went into Burma with in February 1943.

According to the official lists for the 13th King's, William was reported as missing in action on the 14th April 1943 and last seen on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River. According to a witness report from a Corporal McCann, William was part of a group of men last seen building a raft with which to cross the Irrawaddy on the 14th April, but was then never seen again. It seems likely that he was killed/lost soon afterwards, as his official date of death is recorded on the Commonwealth Graves website as 15th April 1943.

It is interesting that you have a slightly later date on your records (25th April). This is not uncommon with the casualties from the first Chindit expedition, where eye witness accounts are few and survivors recollections sometimes confused. I do know that William was part of a dispersal group led by Captain Williams. In early April, Captain Williams group managed to cross the fast flowing Shweli River as a bridgehead unit for No. 8 Column. As the second group of men began to cross, the boats used were washed away down river and never recovered. This left Captain Williams men on there own on the far bank and they set out to return to India alone.

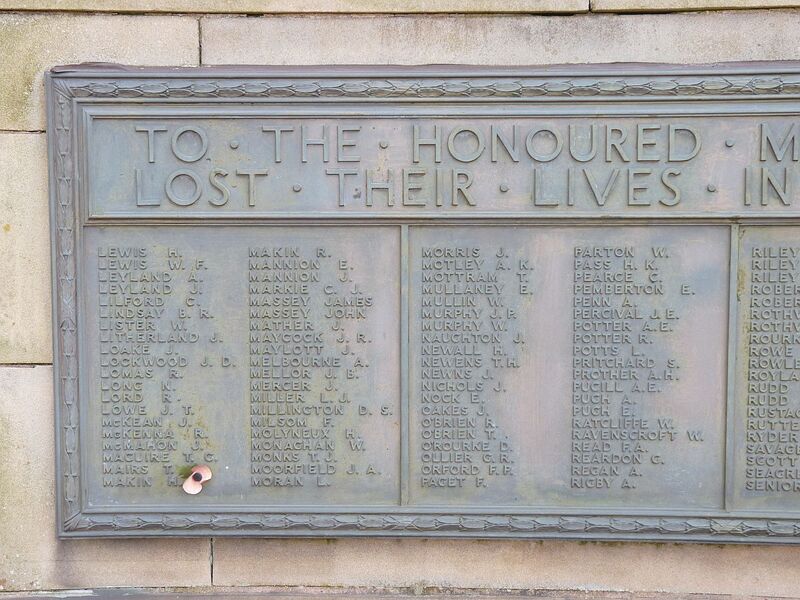

As you already know, William is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery. This memorial contains the names of almost 27,000 casualties from the Burma campaign who have no known grave and whose remains were never found. I do believe that William is also remembered on the Warrington Cenotaph memorial.

This is all I can really tell you about William. I would like to know more about his life before the war and if you have any details about his family life, work etc. it would be great to add these to his few lines on my website. As always it would be wonderful to add a photograph of him to this page if the family possess one that can be scanned. I look forward to hearing from you again presently when I can send you the papers I have showing some of the above information. Best wishes, Steve.

Marylyn replied:

Dear Steve,

Thank you so much for your quick reply which I and my family are so grateful for. I have been in touch with my brother Bill, as it was he that travelled to Rangoon Memorial a couple of years ago and sent him your information. You mentioned that my uncle William Lister is on the War Memorial in Warrington, which I can confirm. What you probably don't know is that William's name was missed off the War Memorial in Warrington for many years until my eldest brother, Edward decided to do something about when he was a Warrington Borough Councillor and later became the Mayor of Warrington. William's name was added to the Cenotaph about 20 years ago, but to ensure a correct date I will have to speak to Edward.

I couldn’t explain how moved I felt when I found the information on the internet about the period of war that Uncle Bill served in. Also, finding the link to your website. It was the closest information found in my many years of research. I telephoned my brother Bill to let him know and forwarded the internet link to him. It’s been amazing just to know that there is now a story to pass on to all of my family and relatives. A story of William Lister that will be with us forever.

What you are doing means so much to us as a family. I was born in 1953 and I remember my mum May could never watch war movies as it brought sad memories back to her. She would be so moved that we have finally found information about Uncle Bill that can be passed on for future generations. Also, to collate any family memories or provide photos of William I will have to make contact with family cousins, as William's brothers Kenneth, Reginald and John and sisters May, Annie and Gertrude are all now deceased. So a big thank you for all your good work providing this historic information for my family and relatives. I will be in touch as soon as I have further information for you.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to William Lister and his service with the Chindits, including photographs of his inscriptions on both the Rangoon and Warrington War Memorials. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 12/04/2021.

I was pleased to receive the following email contact in relation to William Lister from his niece, Marylyn Walton:

I am looking for information regarding my uncle William Lister, Army number 3657365, who was killed on the 25th April 1943 in Burma. He was a soldier in the King's Regiment. He was the brother of my mother May Finnegan nee Lister. Our family have no information on how he died. I have been researching for years, but there have been no published facts on his death, not even a record of any medals issued or if he had friends in his battalion. My brother Bill was named after my uncle and he has visited the cemetery in Rangoon which shows just his name. We have no stories about his time in the Army or in Burma. Is there any information that you could forward to me to enable me to share with my family? Kind regards, Marylyn.

I replied:

Dear Marylyn,

Thank you for your recent email contact via my website in relation to William Lister. I do have some information about William and how he died in Burma in April 1943. This is what I can tell you about his time with the Chindits.

His Army service number comes from the allocation for the Prince of Wales' Volunteers, the South Lancashire Regiment and it is likely that he was with this regiment at the beginning of his WW2 service. He would have been in India by mid-1942 at the latest and after his transfer to the 13th Battalion, the King's Regiment, William was posted to No. 8 (Chindit) Column, under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott. This was the unit he went into Burma with in February 1943.

According to the official lists for the 13th King's, William was reported as missing in action on the 14th April 1943 and last seen on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River. According to a witness report from a Corporal McCann, William was part of a group of men last seen building a raft with which to cross the Irrawaddy on the 14th April, but was then never seen again. It seems likely that he was killed/lost soon afterwards, as his official date of death is recorded on the Commonwealth Graves website as 15th April 1943.

It is interesting that you have a slightly later date on your records (25th April). This is not uncommon with the casualties from the first Chindit expedition, where eye witness accounts are few and survivors recollections sometimes confused. I do know that William was part of a dispersal group led by Captain Williams. In early April, Captain Williams group managed to cross the fast flowing Shweli River as a bridgehead unit for No. 8 Column. As the second group of men began to cross, the boats used were washed away down river and never recovered. This left Captain Williams men on there own on the far bank and they set out to return to India alone.

As you already know, William is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery. This memorial contains the names of almost 27,000 casualties from the Burma campaign who have no known grave and whose remains were never found. I do believe that William is also remembered on the Warrington Cenotaph memorial.

This is all I can really tell you about William. I would like to know more about his life before the war and if you have any details about his family life, work etc. it would be great to add these to his few lines on my website. As always it would be wonderful to add a photograph of him to this page if the family possess one that can be scanned. I look forward to hearing from you again presently when I can send you the papers I have showing some of the above information. Best wishes, Steve.

Marylyn replied:

Dear Steve,

Thank you so much for your quick reply which I and my family are so grateful for. I have been in touch with my brother Bill, as it was he that travelled to Rangoon Memorial a couple of years ago and sent him your information. You mentioned that my uncle William Lister is on the War Memorial in Warrington, which I can confirm. What you probably don't know is that William's name was missed off the War Memorial in Warrington for many years until my eldest brother, Edward decided to do something about when he was a Warrington Borough Councillor and later became the Mayor of Warrington. William's name was added to the Cenotaph about 20 years ago, but to ensure a correct date I will have to speak to Edward.

I couldn’t explain how moved I felt when I found the information on the internet about the period of war that Uncle Bill served in. Also, finding the link to your website. It was the closest information found in my many years of research. I telephoned my brother Bill to let him know and forwarded the internet link to him. It’s been amazing just to know that there is now a story to pass on to all of my family and relatives. A story of William Lister that will be with us forever.

What you are doing means so much to us as a family. I was born in 1953 and I remember my mum May could never watch war movies as it brought sad memories back to her. She would be so moved that we have finally found information about Uncle Bill that can be passed on for future generations. Also, to collate any family memories or provide photos of William I will have to make contact with family cousins, as William's brothers Kenneth, Reginald and John and sisters May, Annie and Gertrude are all now deceased. So a big thank you for all your good work providing this historic information for my family and relatives. I will be in touch as soon as I have further information for you.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to William Lister and his service with the Chindits, including photographs of his inscriptions on both the Rangoon and Warrington War Memorials. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

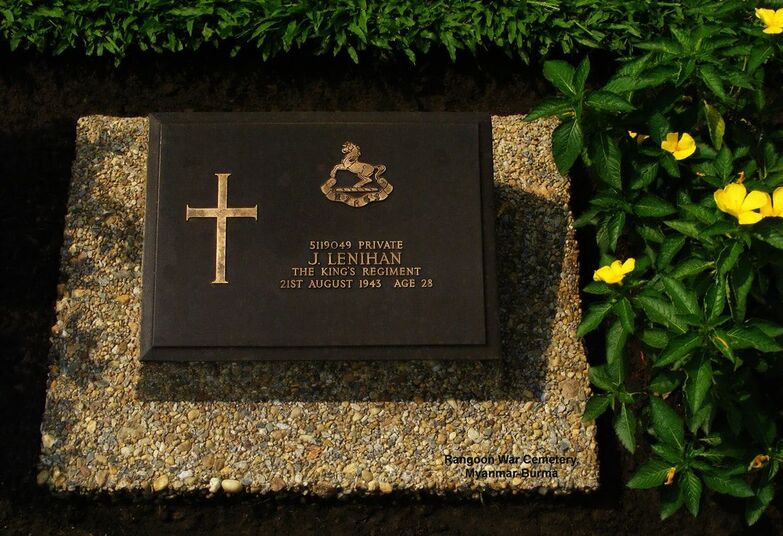

John Lenihan.

John Lenihan.

Pte. John Lenihan. Formerly with the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, John was captured by the Japanese on the 14th April and ended up a prisoner in Rangoon Jail. He sadly died on the 21st August 1943 in Block 6 of the jail, suffering from beri beri and dysentery. John was given the POW number 527 by the Japanese and was buried in the English Cantonment Cemetery. From the pages of the Manchester Evening News, dated 11th June 1945 and under the headline, Roll of Honour:

John Lenihan (King's Regiment, Wingate Expedition), dear husband of Kathleen and darling Daddy to Sheelagh, posted missing on April 15th 1943, now reported as having died on August 21st 1943, whilst in Japanese hands. No details of the camp are available, but any information gratefully received at 1 Tanners Lane, Salford 6.

Update 21/11/2019.

On the 18th August this year, I received an email from Claire McHenry, the granddaughter of Sgt. Harold Palmer:

Hello Steve, I hope this email finds you well. I've copied in a friend from work, Kate Knowles, as whilst chatting during lunch one day, we found out that our grandfathers had both been Chindits and prisoners of war in Rangoon Jail. We're both working in Wiltshire now, but our grandfather's were both from the Manchester area.

I wondered if you can help with any information regarding Kate's grandfather, John Lenihan, who is also featured on your website. Kate doesn't have much information about him and so was really pleased to see him mentioned on your site. Your website mentions Block 6 of Rangoon Jail in relation to their stories - is that where they would both have been placed? We wondered whether they knew each other and I guess that if they were in the same block, that they possibly did. If you do have any information or could offer any advice to Kate regarding how to get more information, that would be very much appreciated.

I replied:

Hi Claire and Kate,

What an incredible coincidence between the two of you, it is almost unbelievable. I'm so pleased that I do have something about John and his sad demise in Burma in August 1943, in fact as I write I notice that it is nearly 76 years to the day since he died. Like Harold, John was also in No. 8 Column commanded by Major Walter Purcell Scott on Operation Longcloth. He was also with Harold as part of Captain Williams' platoon which became separated from the main column on the 1st April 1943 at the Shweli River.

According to his Army number, John must have enlisted into the Royal Warwickshire Regiment at the outset of the war. This might seem unusual if the soldier in question was not from that area of the country, but it was very common at the time. My own grandfather was born and raised in North London, but was posted to the Devonshire Regiment upon enlistment.

His official missing in action date was the 15th April 1943, which would have been the last time an officer from No. 8 Column saw him alive. Of course we know that he became a prisoner of war and died later on the 21st August 1943 in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail. According to his POW details he perished from the diseases beri beri and dysentery, but he would have been extremely malnourished and already exhausted from his experiences with the Chindits even before he arrived at the jail.

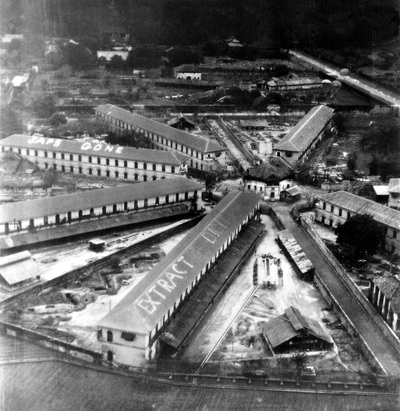

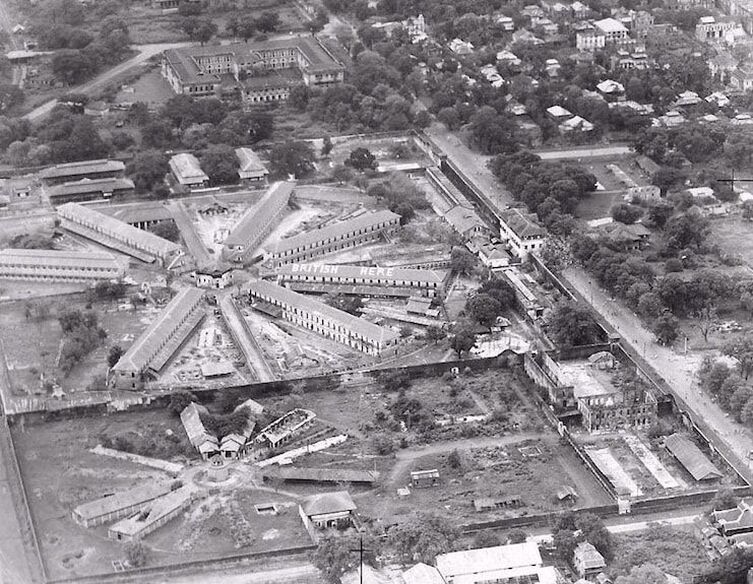

His POW number was 527 and he was buried in the first instance at the English Cantonment Cemetery near the Royal Lakes in the eastern sector of Rangoon. His grave number was recorded as No. 82. Later, after the war was over, all the POW graves at this cemetery were moved over to the newly built Rangoon War Cemetery, which was closer to the city docks and this is where he lies today.

Kate then told me:

Dear Steve, Thank you so, so much. I have tried to find out information about my grandfather before but I haven't done so much in recent years. It was amazing to see both the names (John and Harold) on the same missing list, Claire and I have not stopped talking about it at work. My mum, Sheelagh, died a number of years ago now. As you know, her dad, (my grandfather) John died in August 1943, two years after she was born. Her mum, my grandmother Kathleen, died around ten years later. So mum had very little information about her father.

John had a sister, Vee, and a brother Matthew. They lived in Urmston, now in Greater Manchester, but I don't know if that was where the family came from originally. I do have a very few number of photographs which I would be delighted to send to you. They are in a wooden box in my attic. I can't thank you enough for all you have done for these men and for keeping their memory alive - it is very humbling.

Seen below is a photograph of John Lenihan's grave plaque at Rangoon War Cemetery. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

John Lenihan (King's Regiment, Wingate Expedition), dear husband of Kathleen and darling Daddy to Sheelagh, posted missing on April 15th 1943, now reported as having died on August 21st 1943, whilst in Japanese hands. No details of the camp are available, but any information gratefully received at 1 Tanners Lane, Salford 6.

Update 21/11/2019.

On the 18th August this year, I received an email from Claire McHenry, the granddaughter of Sgt. Harold Palmer:

Hello Steve, I hope this email finds you well. I've copied in a friend from work, Kate Knowles, as whilst chatting during lunch one day, we found out that our grandfathers had both been Chindits and prisoners of war in Rangoon Jail. We're both working in Wiltshire now, but our grandfather's were both from the Manchester area.

I wondered if you can help with any information regarding Kate's grandfather, John Lenihan, who is also featured on your website. Kate doesn't have much information about him and so was really pleased to see him mentioned on your site. Your website mentions Block 6 of Rangoon Jail in relation to their stories - is that where they would both have been placed? We wondered whether they knew each other and I guess that if they were in the same block, that they possibly did. If you do have any information or could offer any advice to Kate regarding how to get more information, that would be very much appreciated.

I replied:

Hi Claire and Kate,

What an incredible coincidence between the two of you, it is almost unbelievable. I'm so pleased that I do have something about John and his sad demise in Burma in August 1943, in fact as I write I notice that it is nearly 76 years to the day since he died. Like Harold, John was also in No. 8 Column commanded by Major Walter Purcell Scott on Operation Longcloth. He was also with Harold as part of Captain Williams' platoon which became separated from the main column on the 1st April 1943 at the Shweli River.

According to his Army number, John must have enlisted into the Royal Warwickshire Regiment at the outset of the war. This might seem unusual if the soldier in question was not from that area of the country, but it was very common at the time. My own grandfather was born and raised in North London, but was posted to the Devonshire Regiment upon enlistment.

His official missing in action date was the 15th April 1943, which would have been the last time an officer from No. 8 Column saw him alive. Of course we know that he became a prisoner of war and died later on the 21st August 1943 in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail. According to his POW details he perished from the diseases beri beri and dysentery, but he would have been extremely malnourished and already exhausted from his experiences with the Chindits even before he arrived at the jail.

His POW number was 527 and he was buried in the first instance at the English Cantonment Cemetery near the Royal Lakes in the eastern sector of Rangoon. His grave number was recorded as No. 82. Later, after the war was over, all the POW graves at this cemetery were moved over to the newly built Rangoon War Cemetery, which was closer to the city docks and this is where he lies today.

Kate then told me:

Dear Steve, Thank you so, so much. I have tried to find out information about my grandfather before but I haven't done so much in recent years. It was amazing to see both the names (John and Harold) on the same missing list, Claire and I have not stopped talking about it at work. My mum, Sheelagh, died a number of years ago now. As you know, her dad, (my grandfather) John died in August 1943, two years after she was born. Her mum, my grandmother Kathleen, died around ten years later. So mum had very little information about her father.

John had a sister, Vee, and a brother Matthew. They lived in Urmston, now in Greater Manchester, but I don't know if that was where the family came from originally. I do have a very few number of photographs which I would be delighted to send to you. They are in a wooden box in my attic. I can't thank you enough for all you have done for these men and for keeping their memory alive - it is very humbling.

Seen below is a photograph of John Lenihan's grave plaque at Rangoon War Cemetery. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

Pte. William Thomas Gray. William was the son of Mr. and Mrs. J. W. Gray and grandson of Mrs. M. J. Mark, of Seaton Delaval in Northumberland. Pte. Gray was captured on the 14th April after the ambush near the Irrawaddy River. He sadly died on the 27th February 1944 in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail and was buried at the Englsih Cantonment Cemetery. William's POW number was 419.

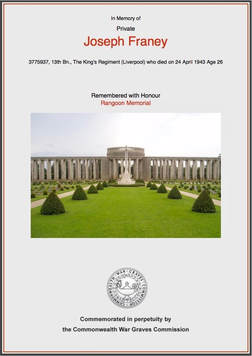

CWGC certificate for Joseph Franey.

CWGC certificate for Joseph Franey.

Pte. Joseph Franey. According to the witness statement given by Corporal McCann, Joseph was reported as missing after the Japanese attack on the 14th April. He was later killed in action on the 24th April, it could well be possible that Joseph somehow managed to re-join Captain Williams party after the earlier ambush, only to be killed in a similar event ten days later. Alternatively, he may have been left on his own during this period and unfortunately stumbled upon another enemy patrol.

Update 01/12/2017.

I was pleased recently, to receive the following email contact from Peter Carton who lives in Perth, Western Australia:

Like you, I seek to tell a largely untold story and to honour my two great uncles. One who fought and died in the first Chindit campaign in 1943 and a second, who went seeking his lost brother and whom as a child I remember and respected greatly.

Like so many of that era, Uncle John talked little of his war experiences. His lament was always I'll tell you some time. The family story was that my Chindit uncle, Joseph Franey (service no. 3775937) of 13th Battalion The King's Regiment, was listed as MIA in 1943 whilst serving with Chindits inside Burma.

His brother John Franey, somehow got to transfer to Burma and attempted to search for his brother. He never of course found him, the apparent last sighting of Joseph was leaving a church. It was some time before he was confirmed dead as of the 24th April 1943 and recorded as buried in Rangoon Memorial within Taukkyan War Cemetery in what is now Myanmar. John himself spent six months in hospital with malaria, possibly in Burma, before being sent back to the UK. It would be great to fully understand the journey my uncles went on; the love and bond of two brothers, who, like so many others, were separated forever by war. Thanks for putting this all on record. Their stories needed to be told and their memories and sacrifice honoured.

Warmest regards Peter Carton

Although I have replied to Peter, sadly, there has been no further email contact between us. I do hope that he will read this new addition about his uncle and get back in touch.

Update 01/12/2017.

I was pleased recently, to receive the following email contact from Peter Carton who lives in Perth, Western Australia:

Like you, I seek to tell a largely untold story and to honour my two great uncles. One who fought and died in the first Chindit campaign in 1943 and a second, who went seeking his lost brother and whom as a child I remember and respected greatly.

Like so many of that era, Uncle John talked little of his war experiences. His lament was always I'll tell you some time. The family story was that my Chindit uncle, Joseph Franey (service no. 3775937) of 13th Battalion The King's Regiment, was listed as MIA in 1943 whilst serving with Chindits inside Burma.

His brother John Franey, somehow got to transfer to Burma and attempted to search for his brother. He never of course found him, the apparent last sighting of Joseph was leaving a church. It was some time before he was confirmed dead as of the 24th April 1943 and recorded as buried in Rangoon Memorial within Taukkyan War Cemetery in what is now Myanmar. John himself spent six months in hospital with malaria, possibly in Burma, before being sent back to the UK. It would be great to fully understand the journey my uncles went on; the love and bond of two brothers, who, like so many others, were separated forever by war. Thanks for putting this all on record. Their stories needed to be told and their memories and sacrifice honoured.

Warmest regards Peter Carton

Although I have replied to Peter, sadly, there has been no further email contact between us. I do hope that he will read this new addition about his uncle and get back in touch.

The above map shows the general location of Captain Williams platoon around the 18th April 1943 and then the subsequent line of march planned by the commander once across the river. I believe that Williams was in this general area for at least one week before crossing the river at Zinbon. It is possible that he and his men were searching for a suitable place to cross for several days, hiding away from the numerous Japanese patrols, or looking desperately for a friendly Burmese villager with access to a boat.

It is at this juncture that some confusion arises between the witness statements and subsequent book accounts given by Corporal McCann for the period. In the book 'With Wingate in Burma' McCann describes the moment the platoon was finally destroyed as being before they had crossed the Irrawaddy, in a smaller tributary of the main river. Whereas, in his main witness statement (transcribed later in this story) he states that the party was ambushed for the final time after they had crossed the Irrawaddy at Zinbon.

Looking through the relevant dates for the members of the platoon, another sub-group appears with the date of death, 17th April 1943, also some men from the unit end up as POW's in Rangoon and have capture dates matching this period, that being, before the final ambush on Williams platoon on the 23rd April.

I believe that there was in fact another attack on the platoon around the 17-18th April, close to the town of Zinbon, but before the men had crossed the Irrawaddy. Before I list the men who were involved in this possible ambush, here is Corporal McCann's account found in the book 'With Wingate in Burma' and recounted by Sgt. Tony Aubrey:

"We (Aubrey and his dispersal group) had come out of the sixth basha, and were on the point of calling the search off as useless and leaving the place, when suddenly, from a house right up at the far end of the village, a man came running out, waving his hands, and doing what seemed to be some sort of step dance.

He was more fair-skinned than Burmans usually are, and he was wearing nothing but a sarong wound round his waist. He was shouting as he came towards us, and to our complete astonishment, what he was shouting turned out to be "I'm English! I'm English!"

We put down our rifles, which had instinctively gone to the ready on his appearance, and gathered round him. He couldn't have enough of shaking our hands, and putting his arm round our shoulders. He seemed to want to make sure we were real. Just at first, we had our doubts about his reality, too, but we soon recognized him. He was a corporal who had been with Captain Williams at the crossing of the Shweli, on the occasion when the rope had parted, and they had been safely over the river, while we were left on the far bank.

He told us the story of that ill-fated party. They had gone, as arranged with Major Scott, to the rendezvous on the mountain top, and had waited there forty-eight hours for is to arrive. When we hadn't come by then, they made up their minds that either the Shweli had been too much for us, or the Japs had got us, and they decided to proceed independently.

We must have reached the rendezvous only a short time after they had pulled out. They proceeded northwards for two days, and then struck west, towards the Irrawaddy. They were, you will remember, about thirty-five strong, and at that time they were well off for food. They made good time, and they found no traces of the enemy.

On the fourth day after leaving the mountain top, they struck a deep river-bed, with rocky and precipitous sides and still a fair-sized body of water flowing along it. This cut their path at right angles, and as they were anxious to keep as straight a path to the Irrawaddy as they could, they decided to cross it, there and then. They tied their packs on their heads, slung their rifles, hung their boots round their necks, and proceeded to ford the river. It was not very deep, they found, and the current, though strong, was not strong enough to make their foothold insecure.

Everything went merrily as a marriage-bell, until they were in mid-stream. Then the Japs opened fire on them from cover on the opposite bank. Machine guns and rifles blazed at them, and about half of them were killed by the first burst. They were absolutely helpless. The only cover available to them was the water, and if they made use of that, they would drown. Their rifles were slung. Before they could get at them, they would all be massacred.

The position was utterly hopeless. Captain Williams did the only possible thing, he surrendered. The Japs held their fire, and the party or what was left of it moved dejectedly across the stream to give itself up. But apparently one or two men on one of the flanks thought they saw a chance of making a break. Probably they thought that anything was to be preferred to a Japanese prison camp, or Japanese playfulness.

They never thought what their attempt might mean to the rest. They made a sudden dash for freedom. At the first move, the enemy opened fire again on the whole party, and in a few seconds it was all over. There was not a single survivor, except this Corporal, who had been the last man into the river-bed, and had managed to regain the shelter of the jungle on his own side. He saw the whole thing happen, before making his own getaway, with a bullet hole through both cheeks."

Here are the men who have the dates 17-18th April against their name, or who were captured shortly after the incident just short of the Irrawaddy at Zinbon:

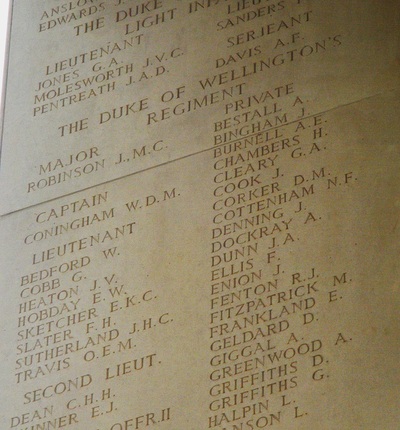

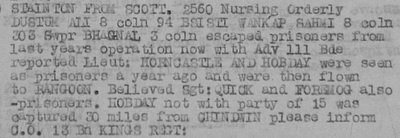

Lieutenant Edward William Hobday. Lieutenant Hobday was the son of Edward and Lillian Hobday and husband of Eva Hobday from Reading in Berkshire. He had joined the 13th King's almost at the very last minute during Chindit training in December 1942 from his former regiment, the Duke of Wellington's. The CWGC state that he was killed in action on the 17th April 1943, however, there is documentary evidence in the form of a witness statement given in 1944 (see the large gallery of 16 images towards the foot of this page) that he was in fact a prisoner of war for a period of time.

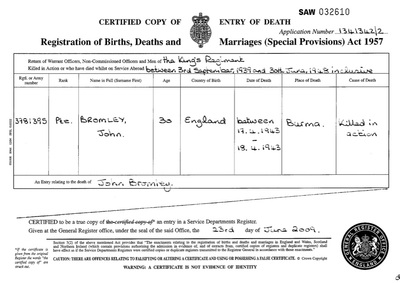

Pte. John Bromley. John Bromley was the husband of Sara Elizabeth Bromley, of Chorley, Lancashire. Pte. Bromley is stated as being killed in action on the 17th April 1943.

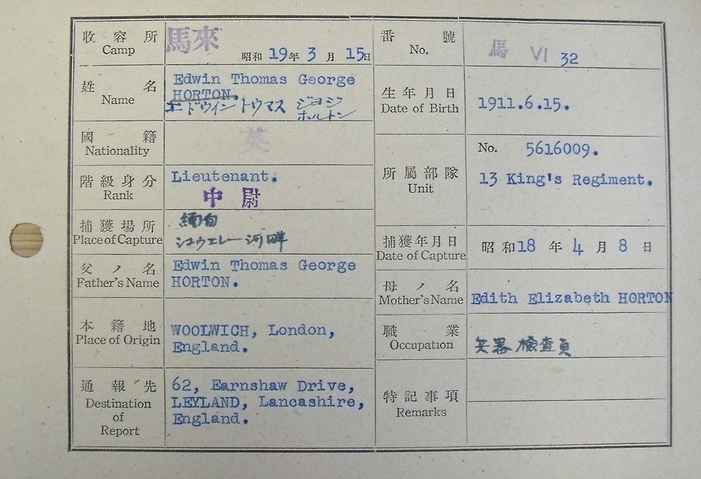

Pte. Eric Horton. Eric Horton was born in the county of Warwickshire in 1919 and had originally seen service with the Royal Warwickshire Regiment during the early part of WW2. He was posted to the 13th King's shortly after his arrival in India, joining the battalion on the 26th September 1942 at the training camp of Saugor. Eric was attached to D' Company of the King's and eventually became part of Chindit Column 8 under the overall command of Major Walter Purcell Scott. Eric is stated as having been killed in action on the 17th April 1943.

All three of the above casualties have other information written about them within these website pages. Simply enter their names in to the search engine panel at the top right hand corner of this page to access this material.

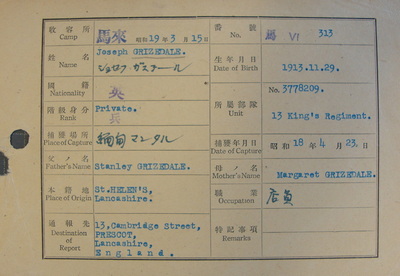

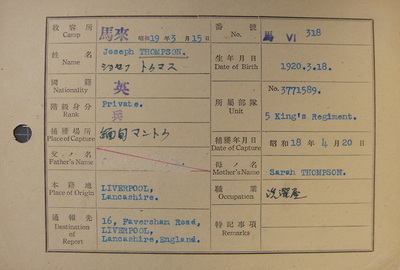

Pte. Joseph Thompson. Liverpudlian Joseph Thompson was an original member of the 13th King's battalion which left Liverpool Docks in December 1941. He too was reported captured by the Japanese on the 20th April 1943, his POW number was 318, he also survived his time in Rangoon Jail and was liberated in late April 1945.

Corporal John Albert Usher. From Wrexham and a former soldier with the Royal Welch Fusiliers, John Usher, was reported captured by the Japanese on the 17th April 1943. He was given the POW number 105 whilst in Rangoon Jail, where he survived his two years of imprisonment, but not before losing a leg to the ravages of infected jungle sores which developed into large and incurable ulcerations. To read more about Corporal Usher, please click on the following link: Roll Call U-Z

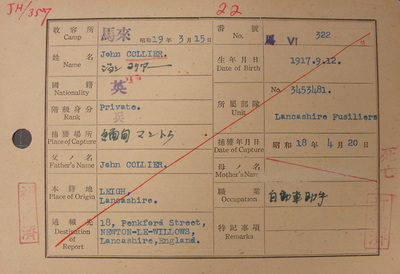

Pte. John Collier. John was the son of John and Maria Collier and husband of Evelyn Collier of Newton-le-Willows in Lancashire. He was captured on the 20th April 1943 and given the POW number 322 whilst in Rangoon Jail. Pte. Collier died in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on the 2nd July 1944 suffering from dysentery, he was buried in the English Cantonment Cemetery.

It is at this juncture that some confusion arises between the witness statements and subsequent book accounts given by Corporal McCann for the period. In the book 'With Wingate in Burma' McCann describes the moment the platoon was finally destroyed as being before they had crossed the Irrawaddy, in a smaller tributary of the main river. Whereas, in his main witness statement (transcribed later in this story) he states that the party was ambushed for the final time after they had crossed the Irrawaddy at Zinbon.

Looking through the relevant dates for the members of the platoon, another sub-group appears with the date of death, 17th April 1943, also some men from the unit end up as POW's in Rangoon and have capture dates matching this period, that being, before the final ambush on Williams platoon on the 23rd April.

I believe that there was in fact another attack on the platoon around the 17-18th April, close to the town of Zinbon, but before the men had crossed the Irrawaddy. Before I list the men who were involved in this possible ambush, here is Corporal McCann's account found in the book 'With Wingate in Burma' and recounted by Sgt. Tony Aubrey:

"We (Aubrey and his dispersal group) had come out of the sixth basha, and were on the point of calling the search off as useless and leaving the place, when suddenly, from a house right up at the far end of the village, a man came running out, waving his hands, and doing what seemed to be some sort of step dance.

He was more fair-skinned than Burmans usually are, and he was wearing nothing but a sarong wound round his waist. He was shouting as he came towards us, and to our complete astonishment, what he was shouting turned out to be "I'm English! I'm English!"

We put down our rifles, which had instinctively gone to the ready on his appearance, and gathered round him. He couldn't have enough of shaking our hands, and putting his arm round our shoulders. He seemed to want to make sure we were real. Just at first, we had our doubts about his reality, too, but we soon recognized him. He was a corporal who had been with Captain Williams at the crossing of the Shweli, on the occasion when the rope had parted, and they had been safely over the river, while we were left on the far bank.

He told us the story of that ill-fated party. They had gone, as arranged with Major Scott, to the rendezvous on the mountain top, and had waited there forty-eight hours for is to arrive. When we hadn't come by then, they made up their minds that either the Shweli had been too much for us, or the Japs had got us, and they decided to proceed independently.

We must have reached the rendezvous only a short time after they had pulled out. They proceeded northwards for two days, and then struck west, towards the Irrawaddy. They were, you will remember, about thirty-five strong, and at that time they were well off for food. They made good time, and they found no traces of the enemy.

On the fourth day after leaving the mountain top, they struck a deep river-bed, with rocky and precipitous sides and still a fair-sized body of water flowing along it. This cut their path at right angles, and as they were anxious to keep as straight a path to the Irrawaddy as they could, they decided to cross it, there and then. They tied their packs on their heads, slung their rifles, hung their boots round their necks, and proceeded to ford the river. It was not very deep, they found, and the current, though strong, was not strong enough to make their foothold insecure.

Everything went merrily as a marriage-bell, until they were in mid-stream. Then the Japs opened fire on them from cover on the opposite bank. Machine guns and rifles blazed at them, and about half of them were killed by the first burst. They were absolutely helpless. The only cover available to them was the water, and if they made use of that, they would drown. Their rifles were slung. Before they could get at them, they would all be massacred.

The position was utterly hopeless. Captain Williams did the only possible thing, he surrendered. The Japs held their fire, and the party or what was left of it moved dejectedly across the stream to give itself up. But apparently one or two men on one of the flanks thought they saw a chance of making a break. Probably they thought that anything was to be preferred to a Japanese prison camp, or Japanese playfulness.

They never thought what their attempt might mean to the rest. They made a sudden dash for freedom. At the first move, the enemy opened fire again on the whole party, and in a few seconds it was all over. There was not a single survivor, except this Corporal, who had been the last man into the river-bed, and had managed to regain the shelter of the jungle on his own side. He saw the whole thing happen, before making his own getaway, with a bullet hole through both cheeks."

Here are the men who have the dates 17-18th April against their name, or who were captured shortly after the incident just short of the Irrawaddy at Zinbon:

Lieutenant Edward William Hobday. Lieutenant Hobday was the son of Edward and Lillian Hobday and husband of Eva Hobday from Reading in Berkshire. He had joined the 13th King's almost at the very last minute during Chindit training in December 1942 from his former regiment, the Duke of Wellington's. The CWGC state that he was killed in action on the 17th April 1943, however, there is documentary evidence in the form of a witness statement given in 1944 (see the large gallery of 16 images towards the foot of this page) that he was in fact a prisoner of war for a period of time.

Pte. John Bromley. John Bromley was the husband of Sara Elizabeth Bromley, of Chorley, Lancashire. Pte. Bromley is stated as being killed in action on the 17th April 1943.

Pte. Eric Horton. Eric Horton was born in the county of Warwickshire in 1919 and had originally seen service with the Royal Warwickshire Regiment during the early part of WW2. He was posted to the 13th King's shortly after his arrival in India, joining the battalion on the 26th September 1942 at the training camp of Saugor. Eric was attached to D' Company of the King's and eventually became part of Chindit Column 8 under the overall command of Major Walter Purcell Scott. Eric is stated as having been killed in action on the 17th April 1943.

All three of the above casualties have other information written about them within these website pages. Simply enter their names in to the search engine panel at the top right hand corner of this page to access this material.

Pte. Joseph Thompson. Liverpudlian Joseph Thompson was an original member of the 13th King's battalion which left Liverpool Docks in December 1941. He too was reported captured by the Japanese on the 20th April 1943, his POW number was 318, he also survived his time in Rangoon Jail and was liberated in late April 1945.

Corporal John Albert Usher. From Wrexham and a former soldier with the Royal Welch Fusiliers, John Usher, was reported captured by the Japanese on the 17th April 1943. He was given the POW number 105 whilst in Rangoon Jail, where he survived his two years of imprisonment, but not before losing a leg to the ravages of infected jungle sores which developed into large and incurable ulcerations. To read more about Corporal Usher, please click on the following link: Roll Call U-Z

Pte. John Collier. John was the son of John and Maria Collier and husband of Evelyn Collier of Newton-le-Willows in Lancashire. He was captured on the 20th April 1943 and given the POW number 322 whilst in Rangoon Jail. Pte. Collier died in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on the 2nd July 1944 suffering from dysentery, he was buried in the English Cantonment Cemetery.

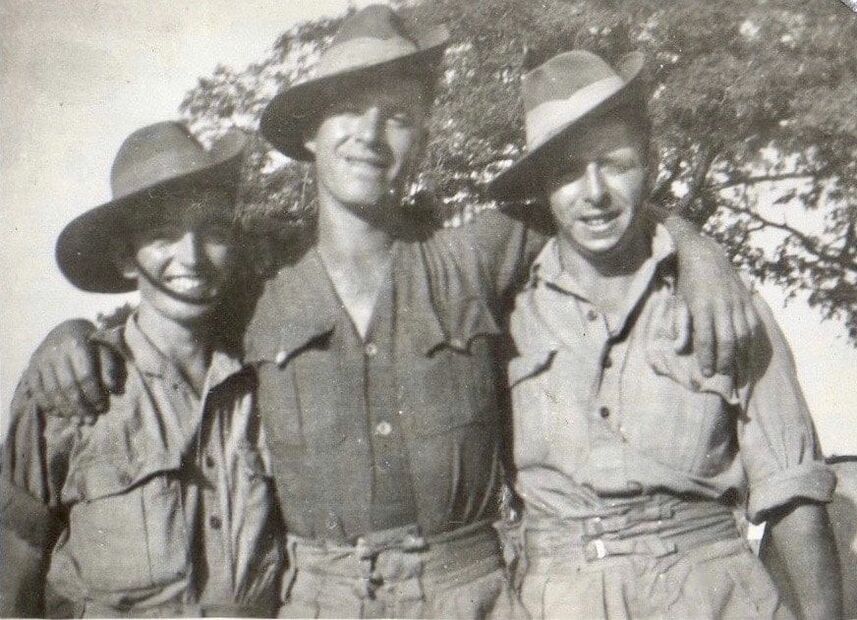

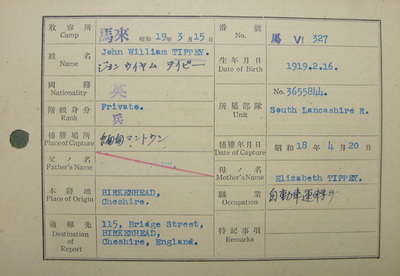

Pte. John William Tippey.

Pte. John William Tippey.

Pte. John William Tippey. John was the son of Elizabeth Tippey from Bridge Street in Birkenhead near Liverpool. He was reported captured by the Japanese on the 20th April 1943, his POW number was 327, he survived his time as a prisoner of war in Rangoon Jail and was liberated in late April 1945. In late July 1943 his family placed the following notice in the pages of the Liverpool Echo newspaper:

Private John William Tippey, husband of Mrs. J.W. Tippey of 115 Bridge Street, Birkenhead, is missing in the Indian theatre of war. Any news of him gratefully received.

Update 27/01/2019.

On the 29th December 2018, I was delighted to receive the following email contact from Laurence Tippey:

Just to put a name to the picture of three soldiers in your Gallery ID pages (shown below). My father, John Tippey is the man on the right. He was from Birkenhead in Cheshire and passed away in 1997. In the larger picture of the the group he is second from the right in the back row. I hope this helps your research and adds further information for your records. After demobilisation, my father went back to work for British Railways as a driver at the local distribution depot until the early 1960's. He then worked for B.O.C. (British Oxygen Company) as a HGV driver delivering oxygen to hospitals. His final job was with R Whites the lemonade company until his retirement in 1984.

My mother and father had seven children, five of whom are still alive. At the last count there are over twenty grandchildren and already fifteen great grandchildren. Dad was very strict with us all when we were growing up, but would support and defend us to the hilt if we were in any trouble. I was with him when he died at home and suffering from cancer, in his last words to his family he told us how proud he was of us all and thanked me for looking after him in the years since mum passed away.

He never spoke or burdened us with what had happened during his time in Burma. We were all brought up in local council housing, but we have all been able to purchase our own homes and bring up our children to have respect for others and to stand up for themselves. All this is thanks to Private John William Tippey and of course our Mum. I hope this gives you a good reflection of my father's life and I would like to dedicate this short biography to all the mates he lost and to the ones who returned home safely, but who probably have suffered quietly throughout the rest of their lives. Thank you, Laurence N. Tippey.

Private John William Tippey, husband of Mrs. J.W. Tippey of 115 Bridge Street, Birkenhead, is missing in the Indian theatre of war. Any news of him gratefully received.

Update 27/01/2019.

On the 29th December 2018, I was delighted to receive the following email contact from Laurence Tippey:

Just to put a name to the picture of three soldiers in your Gallery ID pages (shown below). My father, John Tippey is the man on the right. He was from Birkenhead in Cheshire and passed away in 1997. In the larger picture of the the group he is second from the right in the back row. I hope this helps your research and adds further information for your records. After demobilisation, my father went back to work for British Railways as a driver at the local distribution depot until the early 1960's. He then worked for B.O.C. (British Oxygen Company) as a HGV driver delivering oxygen to hospitals. His final job was with R Whites the lemonade company until his retirement in 1984.

My mother and father had seven children, five of whom are still alive. At the last count there are over twenty grandchildren and already fifteen great grandchildren. Dad was very strict with us all when we were growing up, but would support and defend us to the hilt if we were in any trouble. I was with him when he died at home and suffering from cancer, in his last words to his family he told us how proud he was of us all and thanked me for looking after him in the years since mum passed away.

He never spoke or burdened us with what had happened during his time in Burma. We were all brought up in local council housing, but we have all been able to purchase our own homes and bring up our children to have respect for others and to stand up for themselves. All this is thanks to Private John William Tippey and of course our Mum. I hope this gives you a good reflection of my father's life and I would like to dedicate this short biography to all the mates he lost and to the ones who returned home safely, but who probably have suffered quietly throughout the rest of their lives. Thank you, Laurence N. Tippey.

Harold Palmer in early 1942.

Harold Palmer in early 1942.

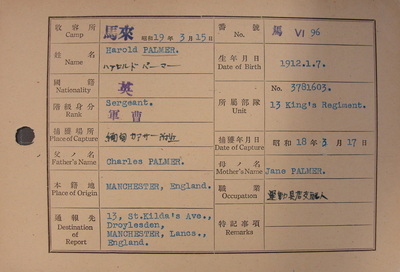

Sergeant Harold Palmer. From Droylesden in Manchester, Harold was captured on the 17th April 1943. He was given the POW number 96 in Rangoon Jail where he spent two years as a prisoner in Japanese hands, before being liberated in late April 1945.

Update 14/03/2016.

Just recently I was extremely pleased to receive an email contact from Claire McHenry, the granddaughter of Harold Palmer. Claire has shared a number of photographs with me and provided some interesting information about her grandfather's time in India and Burma. From the information she has given, I have been able to update several other stories on this website, including those of Raymond Ramsay and Gurkha Officer Lieutenant William Kirkpatrick.

I have also added one of the new photographs, showing Harold and a large group of officers and men aboard the troopship Oronsay to the Gallery ID Parade page: ID Parade

To read the full story in regards to Harold Palmer, please click on the following link: Sergeant Harold Palmer

Update 14/03/2016.

Just recently I was extremely pleased to receive an email contact from Claire McHenry, the granddaughter of Harold Palmer. Claire has shared a number of photographs with me and provided some interesting information about her grandfather's time in India and Burma. From the information she has given, I have been able to update several other stories on this website, including those of Raymond Ramsay and Gurkha Officer Lieutenant William Kirkpatrick.

I have also added one of the new photographs, showing Harold and a large group of officers and men aboard the troopship Oronsay to the Gallery ID Parade page: ID Parade

To read the full story in regards to Harold Palmer, please click on the following link: Sergeant Harold Palmer

Ambush on the 23rd April

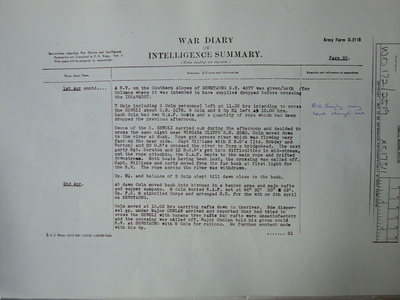

"I was with the above mentioned party under the command of Captain R.E. Williams. We crossed the Irrawaddy at Zinbon on or about the 18th April 1943 and travelled west. On the 23rd April we were on the banks of a river, name unknown (only 20 yards wide) when we were suddenly attacked.

I found myself in the river with Captain Williams (afterwards killed). I was wounded whilst in the river but got to the other side. On looking back to the other side of the river I saw most of our men being taken prisoner by a numerically superior force. I saw quite clearly Ptes. Wallace and Satchell and then I collapsed. On regaining consciousness I searched the area but found no trace of any of the above party."

This is how Corporal A. McCann described the last moments of Platoon 18's existence in April 1943. The actual witness statement can be seen above. Listed below are the men lost or captured on the 23rd April.

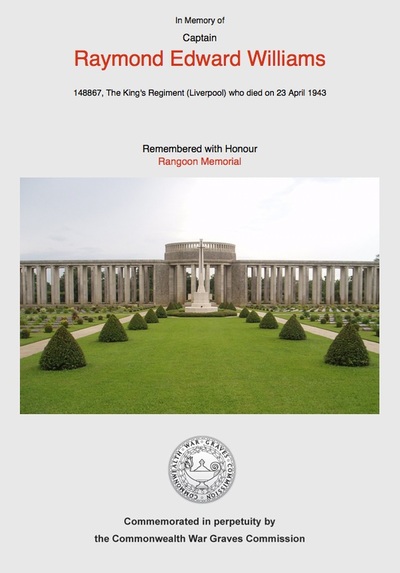

Captain Raymond Edward Williams. The commander of Platoon 18, Raymond Williams was killed in action on the 23rd April at the ambush after crossing the Irrawaddy River. He is remembered upon the Rangoon Memorial in Taukkyan War Cemetery, this memorial was created for the many casualties of the Burma campaign who have no known grave.

"I was with the above mentioned party under the command of Captain R.E. Williams. We crossed the Irrawaddy at Zinbon on or about the 18th April 1943 and travelled west. On the 23rd April we were on the banks of a river, name unknown (only 20 yards wide) when we were suddenly attacked.

I found myself in the river with Captain Williams (afterwards killed). I was wounded whilst in the river but got to the other side. On looking back to the other side of the river I saw most of our men being taken prisoner by a numerically superior force. I saw quite clearly Ptes. Wallace and Satchell and then I collapsed. On regaining consciousness I searched the area but found no trace of any of the above party."

This is how Corporal A. McCann described the last moments of Platoon 18's existence in April 1943. The actual witness statement can be seen above. Listed below are the men lost or captured on the 23rd April.

Captain Raymond Edward Williams. The commander of Platoon 18, Raymond Williams was killed in action on the 23rd April at the ambush after crossing the Irrawaddy River. He is remembered upon the Rangoon Memorial in Taukkyan War Cemetery, this memorial was created for the many casualties of the Burma campaign who have no known grave.

William Satchell.

William Satchell.