Captain George Carne MC

The Military Cross.

The Military Cross.

Before the war, Cornishman George Power Carne was the owner of a Tung Oil Plantation in the Shan States of Northern Burma. Born on the 28th December 1909 in Falmouth located on the south coastline of Cornwall, he was the youngest son of George Newby Carne and Annie Emily le Poar Carne, née Power. As war with Japan became almost inevitable, George's occupation within the plantation industry and expert knowledge of the country and its people, made him an obvious choice for a commission into the rapidly expanding Armed Forces in Burma. He was subsequently commissioned into the Burma Rifles with the Army number, ABRO 57 and took up a position in the 2nd Battalion of the Regiment.

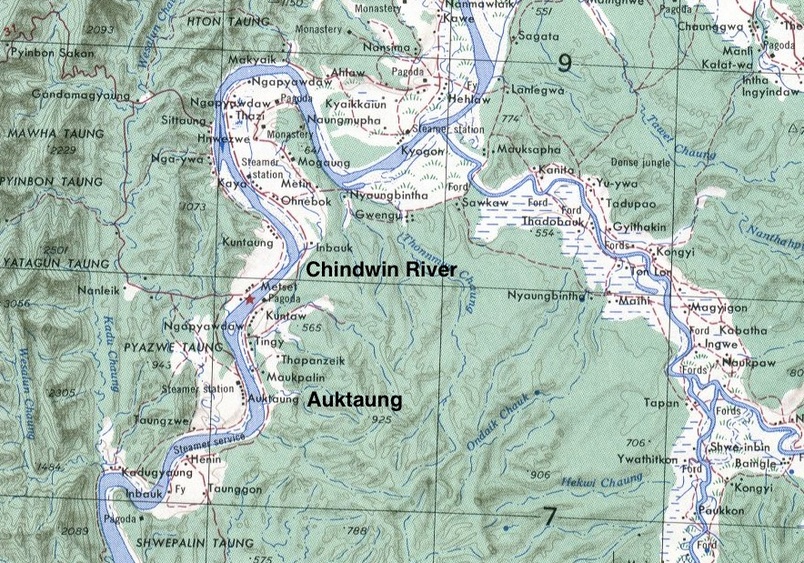

Captain Carne's time during the first Wingate expedition is intrinsically linked with another young officer from the 2nd Burma Rifles, Lieutenant James Charles Bruce; and their adventures are recorded in many of the Chindit column war diaries and subsequent books. Both men served with Southern Group Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth, with Bruce acting as Carne's second in command in the Burma Rifles, or Burrifs as they were nicknamed in 1943. Not long after Southern Group had crossed the Chindwin River at the village of Auktaung, Carne ordered Lt. Bruce to push on ahead with a platoon of Burma Riflemen and scout the intended pathway towards Southern Group's first objective.

Southern Group, commanded by Lt-Colonel L.A. Alexander of 3/2 Gurkha Rifles consisted of two Gurkha columns, numbered 1 and 2 and a Brigade Group Head Quarters. This unit was used by Wingate as a decoy on Operation Longcloth, with the intention being for Southern Group to draw attention away from the main Chindit columns of Northern Group, whilst they crossed the Chindwin River slightly to the north and moved quickly east toward their targets along the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway.

Southern Group crossed the Chindwin on 15/16th February 1943 at a place called Auktaung. Their orders were to march toward their own prime objective, the rail station at Kyaikthin. They marched openly along well known local trails and paths and also received a large supply drop from the air, which must have announced their presence in the area to the Japanese. The decoy group were accompanied at this time by a Company of Sikh Mountain Artillery and a section of Seaforth Highlanders. This supplementary unit were to create a further diversion for Wingate by attacking the town of Pantha, alerting the enemy to the possibility that there might well be a full-scale re-invasion taking place. To all intents and purposes these tactics succeeded and Northern Group did proceed unmolested toward their objectives.

George Carne was in the vanguard of Southern Group's progress, checking out villages for any enemy presence and securing intelligence from the local population. In the book, Wingate's Adventure, author W.G. Burchett describes quite admirably Captain Carne's approach when encountering the Burmese in 1943:

By February 20th the whole Wingate force is across the Chindwin with patrols out in wide sweeps ahead, checking on Jap movements. The finer details of the strategy have been decided. Southern Group is to carry on with its feint in the south, persuading the Japs that a big attack is developing against Kalewa, at the same time jockeying for position to do a job of work against the railway. Northern Group is to make diversionary attacks against two small towns to the north, Pinlebu and Pinbon, while Calvert and Fergusson with their columns break away and dash through with all speed to the railway.

Southern Group crossed the Chindwin on the night of February 15th-16th and a patrol of Burma Rifles, led by George Carne, who in civil life managed a tung oil plantation in the Shan States, slipped on ahead to spy out the land. Carne is a rugged Cornishman who had lived in Burma for ten years. He liked Burmans and spoke their language so had no hesitation in walking straight down the main street of the first village he encountered.

Although it was just after lunch-time there was only one Burmese present, a woman in the streets. Carne walked along and spoke to her in her own tongue. "Hallo, Mother. Are there any Japs around here ?" Burmese ladies are notably self-possessed, and this one showed no surprise at being approached by a British officer in full uniform. "Yes, there are," she answered. "There are one hundred and fifty camped down at the end of the village near the Dak Bungalow." Carne looked down the long deserted street, at the rows of shuttered houses and shops, and decided maybe there were Japs about.

He went back out of the village with his eight Riflemen, set an ambush on the road in case the Japs tried to follow him, and sent two runners back along the track to warn one of the columns, which was supposed to be following on behind. After dark he sent two more Riflemen, disguised in longyis, back to the village to check how many Japs were there. Just as they crept near the first house, a Jap sentry screamed at them so they had to retire.

Carne kept his ambush in position till daybreak, then moved back to contact the column under Major Emmett. The other column meanwhile had been warned, and prepared positions each side of the tracks the Japs must take if they left the village. The Japs were moving troops across to find out what was happening at Auktaung. Just before dusk on the 18th, about 30 of them came gaily along a broad path that led down to a small stream overgrown with drooping bushes. The first to reach the stream leaned their rifles against a tree and knelt to scoop up some drinking water with small bamboo cups.

Suddenly all together they pitched forward head first into the water as four rifles cracked. Then followed a crashing volley of automatic fire, and several more fell. The remainder dashed to the side of the jungle and began firing back in the general direction of the shooting. Another party following further back jumped for the jungle, and quickly brought mortars into action, pumping shells indiscriminately on both sides of the path. It was getting too dark for either side to do accurate shooting, so the engagement was soon broken off with the Japs making back towards the village.

Early next morning George Carne went back along the track to see what was happening. With six Burma Riflemen he cautiously walked along the leaf-strewn path. One of the Riflemen grabbed his arm, motioned silence and pointed. A hundred yards ahead there were some stretchers laid out on the side of the track under some young teak trees. Approaching closer Carne saw the stretchers held four Japs, but just as he bent over to make sure they were all dead, one suddenly sat up and groaned.

At the same time Carne heard movement in the bushes at the side, and he tumbled to what was going on. The Japs had come back for their dead and wounded. Determined to get a prisoner of war, he had two of his men pick up the casualty, stretcher and all, and as the rustling got closer they made off down the road. A fusillade of shots followed them after they had gone a short distance. The stretcher-bearers kept going, while the others slipped behind trees and returned fire, whereupon the Japs stopped shooting. To Carne's intense disgust, they just got the Jap back to Group Headquarters and an Interpreter, when he sat up, looked around, and seeming to understand what was going on, promptly laid down and died. "There was hardly a thing the matter with him," Carne told me afterwards. "He died just out of sheer cussedness.

Captain Carne's time during the first Wingate expedition is intrinsically linked with another young officer from the 2nd Burma Rifles, Lieutenant James Charles Bruce; and their adventures are recorded in many of the Chindit column war diaries and subsequent books. Both men served with Southern Group Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth, with Bruce acting as Carne's second in command in the Burma Rifles, or Burrifs as they were nicknamed in 1943. Not long after Southern Group had crossed the Chindwin River at the village of Auktaung, Carne ordered Lt. Bruce to push on ahead with a platoon of Burma Riflemen and scout the intended pathway towards Southern Group's first objective.

Southern Group, commanded by Lt-Colonel L.A. Alexander of 3/2 Gurkha Rifles consisted of two Gurkha columns, numbered 1 and 2 and a Brigade Group Head Quarters. This unit was used by Wingate as a decoy on Operation Longcloth, with the intention being for Southern Group to draw attention away from the main Chindit columns of Northern Group, whilst they crossed the Chindwin River slightly to the north and moved quickly east toward their targets along the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway.

Southern Group crossed the Chindwin on 15/16th February 1943 at a place called Auktaung. Their orders were to march toward their own prime objective, the rail station at Kyaikthin. They marched openly along well known local trails and paths and also received a large supply drop from the air, which must have announced their presence in the area to the Japanese. The decoy group were accompanied at this time by a Company of Sikh Mountain Artillery and a section of Seaforth Highlanders. This supplementary unit were to create a further diversion for Wingate by attacking the town of Pantha, alerting the enemy to the possibility that there might well be a full-scale re-invasion taking place. To all intents and purposes these tactics succeeded and Northern Group did proceed unmolested toward their objectives.

George Carne was in the vanguard of Southern Group's progress, checking out villages for any enemy presence and securing intelligence from the local population. In the book, Wingate's Adventure, author W.G. Burchett describes quite admirably Captain Carne's approach when encountering the Burmese in 1943:

By February 20th the whole Wingate force is across the Chindwin with patrols out in wide sweeps ahead, checking on Jap movements. The finer details of the strategy have been decided. Southern Group is to carry on with its feint in the south, persuading the Japs that a big attack is developing against Kalewa, at the same time jockeying for position to do a job of work against the railway. Northern Group is to make diversionary attacks against two small towns to the north, Pinlebu and Pinbon, while Calvert and Fergusson with their columns break away and dash through with all speed to the railway.

Southern Group crossed the Chindwin on the night of February 15th-16th and a patrol of Burma Rifles, led by George Carne, who in civil life managed a tung oil plantation in the Shan States, slipped on ahead to spy out the land. Carne is a rugged Cornishman who had lived in Burma for ten years. He liked Burmans and spoke their language so had no hesitation in walking straight down the main street of the first village he encountered.

Although it was just after lunch-time there was only one Burmese present, a woman in the streets. Carne walked along and spoke to her in her own tongue. "Hallo, Mother. Are there any Japs around here ?" Burmese ladies are notably self-possessed, and this one showed no surprise at being approached by a British officer in full uniform. "Yes, there are," she answered. "There are one hundred and fifty camped down at the end of the village near the Dak Bungalow." Carne looked down the long deserted street, at the rows of shuttered houses and shops, and decided maybe there were Japs about.

He went back out of the village with his eight Riflemen, set an ambush on the road in case the Japs tried to follow him, and sent two runners back along the track to warn one of the columns, which was supposed to be following on behind. After dark he sent two more Riflemen, disguised in longyis, back to the village to check how many Japs were there. Just as they crept near the first house, a Jap sentry screamed at them so they had to retire.

Carne kept his ambush in position till daybreak, then moved back to contact the column under Major Emmett. The other column meanwhile had been warned, and prepared positions each side of the tracks the Japs must take if they left the village. The Japs were moving troops across to find out what was happening at Auktaung. Just before dusk on the 18th, about 30 of them came gaily along a broad path that led down to a small stream overgrown with drooping bushes. The first to reach the stream leaned their rifles against a tree and knelt to scoop up some drinking water with small bamboo cups.

Suddenly all together they pitched forward head first into the water as four rifles cracked. Then followed a crashing volley of automatic fire, and several more fell. The remainder dashed to the side of the jungle and began firing back in the general direction of the shooting. Another party following further back jumped for the jungle, and quickly brought mortars into action, pumping shells indiscriminately on both sides of the path. It was getting too dark for either side to do accurate shooting, so the engagement was soon broken off with the Japs making back towards the village.

Early next morning George Carne went back along the track to see what was happening. With six Burma Riflemen he cautiously walked along the leaf-strewn path. One of the Riflemen grabbed his arm, motioned silence and pointed. A hundred yards ahead there were some stretchers laid out on the side of the track under some young teak trees. Approaching closer Carne saw the stretchers held four Japs, but just as he bent over to make sure they were all dead, one suddenly sat up and groaned.

At the same time Carne heard movement in the bushes at the side, and he tumbled to what was going on. The Japs had come back for their dead and wounded. Determined to get a prisoner of war, he had two of his men pick up the casualty, stretcher and all, and as the rustling got closer they made off down the road. A fusillade of shots followed them after they had gone a short distance. The stretcher-bearers kept going, while the others slipped behind trees and returned fire, whereupon the Japs stopped shooting. To Carne's intense disgust, they just got the Jap back to Group Headquarters and an Interpreter, when he sat up, looked around, and seeming to understand what was going on, promptly laid down and died. "There was hardly a thing the matter with him," Carne told me afterwards. "He died just out of sheer cussedness.

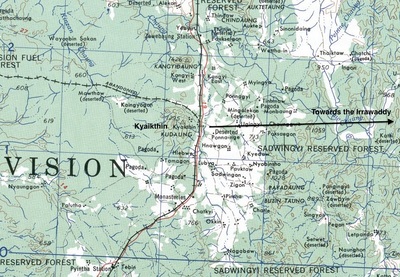

By the 2nd March, Southern Group had reached the outskirts of Kyaikthin, Major Dunlop, 1 Column's commander was given the order to blow up the railway bridge, whilst Column 2 under the command of Major Arthur Emmett along with Group HQ were to head on towards the rail station itself. What neither group realised was that the Japanese had by now closed in on the unsuspecting Chindits and lay in wait just a short way up the rail tracks. To make matters worse the two Gurkha columns had now lost radio contact with each other. Column 2 and Group Head Quarters in the black of night, stumbled into the enemy ambush which straddled both sides of the railway line embankment. Here is how Lieutenant Ian MacHorton of the Gurkha Rifles remembered that moment in his book, Safer Than a Known Way:

"We shuffled to a halt as the guides probed forward. There came the sound of just one bang up front, then an inferno of noise engulfed the world around me. There came the high-pitched staccato scream of a machine gun, then overwhelmingly many others joined in, the crash and ping of rifle bullets, the banging of grenades as the battle reached a fearful crescendo. Men and mules were lying, twisted and contorted, twitching and writhing, others were still erect, stark in the moonlight, heaving and jerking in the midst of this chaos. Then a sinister scuffling noise made by men of all kinds in close combat. The close combat of bayonet and kukri, the fanatical, personal slaughter with blood-dripping cold steel."

Southern Group and 2 Column in particular had met their Waterloo!

It cannot be verified whether George Carne was caught out at Kyaikthin alongside the other men from 2 Column, or if, which seems more likely, he had moved on ahead and joined up with Lt. Bruce at the Irrawaddy. We do know that by the 7th March, he was present at the river. This fact is confirmed by a short excerpt from 2 Column's War diary for 1943, as record by Captain Eric Stephenson of the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles:

After Kyaikthin some of my men joined together with 1 Column under Major Dunlop and proceeded to the Irrawaddy. A Platoon commanded by Jemadar Manbahadur was also led forward, but failing to make contact with other parts of the Column, went back safely to India. A small party led by myself joined up with the Burma Rifle Platoon and, after waiting at the river until March 7th, came under command of Captain Carne and operated as a reconnaissance patrol for a further five weeks.

Captain Carne and Lt. Bruce held control of this area of the Irrawaddy, preventing enemy river traffic from operating and collecting useful intelligence from the local Burmese villages. Eventually, Carne decided that their time in Burma was done and they turned west and returned to India. In his book, Beyond the Chindwin, Bernard Fergusson pays tribute to both officers:

The adventures of Captain George Carne and Lieutenant Charles Bruce, both of the Burma Rifles attached to No. 1 Group, are worth recording. Charlie Bruce had been sent on ahead, before No. 2 Column got into trouble, to seize a village on the Irrawaddy, and capture all its boats.

He occupied the village with six Burma Riflemen, and held it for some days before he heard from local gossip what had happened to No. 2 Column. During his stay in the village, he disarmed the local police, who had been armed by the Japs; sank with Tommy-gun fire a boatload of Japanese, whom he dispatched; and made a remarkable propaganda speech. He had just said, "I can call great Air Forces from India at will," and thrown his arm in the air with an extravagant gesture, when he suddenly heard, far away behind him in the west, the droning of aircraft.

He remained with his arm in the air, like Moses when he was dealing with the Amalekites; and six British bombers flew slowly over his head, in the direction of Mandalay. " What did I tell you," said Charlie, recovering himself. From then on he was a made man. Hearing at last that his column had been ambushed he joined up with Captain Carne. They crossed the Irrawaddy; it was they who occupied the Rest House at Yingwin when 5 Column was at Pegon. After many exciting adventures, they arrived, in India, early in April. Both received the Military Cross.

As already highlighted by Bernard Fergusson; for his courageous decision to continue on eastwards after Kyaikthin and for his success in bringing home his entire platoon, George Carne was recommended for the Military Cross by the senior Burma Rifles officer on Operation Longcloth, Lieutenant-Colonel P.C. Buchanan.

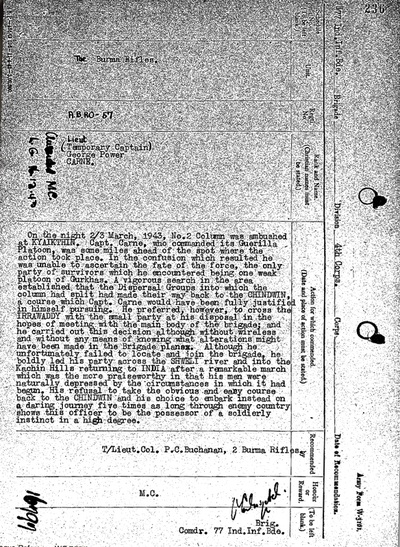

ABRO 57 Lieutenant (temporary Captain) George Power Carne

Brigade-77th Indian Infantry Brigade

Corps-4th Corps

Unit-2nd Battalion, The Burma Rifles

Action for which recommended:

On the night 2/3 March 1943, No. 2 Column was ambushed at Kyaikthin. Captain Carne, who commanded its Guerilla Platoon, was some miles ahead of the spot where the action took place. In the confusion which resulted he was unable to ascertain the fate of the force, the only party of survivors which he encountered being one weak platoon of Gurkhas. A vigorous search in the area established that the Dispersal Groups into which the column had split had made their way back to the Chindwin River, a course which Captain Carne would have been fully justified in himself pursuing.

He preferred, however, to cross the Irrawaddy with the small party at his disposal in the hopes of meeting with the main body of the Brigade; and he carried out this decision although without wireless and without any means of knowing what alterations might have been made in the Brigade plans. Although he unfortunately failed to locate and join the Brigade, he boldly led his party across the Shweli River and into the Kachin Hills returning to India after a remarkable march which was the more praiseworthy in that his men were naturally depressed by the circumstances in which it had begun. His refusal to take the obvious and easy course back to the Chindwin and his choice to embark instead on a daring journey five times as long through enemy country shows this officer to be the possessor of a soldierly instinct in a high degree.

Recommended By-Temporary Lieut-Colonel P.C.Buchanan, 2nd Burma Rifles

Honour or Reward-Military Cross

Signed By-Brigadier O.C. Wingate

Commander 77th Indian Infantry Brigde.

Gazetted 16.12.1943

It is recorded in the 2nd Burma Rifles War diary for 1943, that even after arriving safely in India with his platoon, George Carne then went back into Burma around mid-May, to a place called Fort Hertz, where he awaited and welcomed more of his returning Burma Riflemen. This seems quite remarkable in view of the energy he must have expended on the operation, but is typical of the man in regards to the care and welfare of his men. After the war and having attained the Army Rank of Major, George Carne returned to England and in later life was a valued member of the West Cornwall Branch of the Burma Star Association. George sadly died in the Kerrier District of Cornwall in September 1987, his death was acknowledged in the Summer 1988 edition of the Burma Star magazine, Dekho!

Seen below are a few more images in relation to Captain Carne's time in Burma and a photograph of his brother, James Power Carne, who was awarded the Victoria Cross for his command of the 1st Battalion, the Gloucestershire Regiment during the Korean War. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

"We shuffled to a halt as the guides probed forward. There came the sound of just one bang up front, then an inferno of noise engulfed the world around me. There came the high-pitched staccato scream of a machine gun, then overwhelmingly many others joined in, the crash and ping of rifle bullets, the banging of grenades as the battle reached a fearful crescendo. Men and mules were lying, twisted and contorted, twitching and writhing, others were still erect, stark in the moonlight, heaving and jerking in the midst of this chaos. Then a sinister scuffling noise made by men of all kinds in close combat. The close combat of bayonet and kukri, the fanatical, personal slaughter with blood-dripping cold steel."

Southern Group and 2 Column in particular had met their Waterloo!

It cannot be verified whether George Carne was caught out at Kyaikthin alongside the other men from 2 Column, or if, which seems more likely, he had moved on ahead and joined up with Lt. Bruce at the Irrawaddy. We do know that by the 7th March, he was present at the river. This fact is confirmed by a short excerpt from 2 Column's War diary for 1943, as record by Captain Eric Stephenson of the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles:

After Kyaikthin some of my men joined together with 1 Column under Major Dunlop and proceeded to the Irrawaddy. A Platoon commanded by Jemadar Manbahadur was also led forward, but failing to make contact with other parts of the Column, went back safely to India. A small party led by myself joined up with the Burma Rifle Platoon and, after waiting at the river until March 7th, came under command of Captain Carne and operated as a reconnaissance patrol for a further five weeks.

Captain Carne and Lt. Bruce held control of this area of the Irrawaddy, preventing enemy river traffic from operating and collecting useful intelligence from the local Burmese villages. Eventually, Carne decided that their time in Burma was done and they turned west and returned to India. In his book, Beyond the Chindwin, Bernard Fergusson pays tribute to both officers:

The adventures of Captain George Carne and Lieutenant Charles Bruce, both of the Burma Rifles attached to No. 1 Group, are worth recording. Charlie Bruce had been sent on ahead, before No. 2 Column got into trouble, to seize a village on the Irrawaddy, and capture all its boats.

He occupied the village with six Burma Riflemen, and held it for some days before he heard from local gossip what had happened to No. 2 Column. During his stay in the village, he disarmed the local police, who had been armed by the Japs; sank with Tommy-gun fire a boatload of Japanese, whom he dispatched; and made a remarkable propaganda speech. He had just said, "I can call great Air Forces from India at will," and thrown his arm in the air with an extravagant gesture, when he suddenly heard, far away behind him in the west, the droning of aircraft.

He remained with his arm in the air, like Moses when he was dealing with the Amalekites; and six British bombers flew slowly over his head, in the direction of Mandalay. " What did I tell you," said Charlie, recovering himself. From then on he was a made man. Hearing at last that his column had been ambushed he joined up with Captain Carne. They crossed the Irrawaddy; it was they who occupied the Rest House at Yingwin when 5 Column was at Pegon. After many exciting adventures, they arrived, in India, early in April. Both received the Military Cross.

As already highlighted by Bernard Fergusson; for his courageous decision to continue on eastwards after Kyaikthin and for his success in bringing home his entire platoon, George Carne was recommended for the Military Cross by the senior Burma Rifles officer on Operation Longcloth, Lieutenant-Colonel P.C. Buchanan.

ABRO 57 Lieutenant (temporary Captain) George Power Carne

Brigade-77th Indian Infantry Brigade

Corps-4th Corps

Unit-2nd Battalion, The Burma Rifles

Action for which recommended:

On the night 2/3 March 1943, No. 2 Column was ambushed at Kyaikthin. Captain Carne, who commanded its Guerilla Platoon, was some miles ahead of the spot where the action took place. In the confusion which resulted he was unable to ascertain the fate of the force, the only party of survivors which he encountered being one weak platoon of Gurkhas. A vigorous search in the area established that the Dispersal Groups into which the column had split had made their way back to the Chindwin River, a course which Captain Carne would have been fully justified in himself pursuing.

He preferred, however, to cross the Irrawaddy with the small party at his disposal in the hopes of meeting with the main body of the Brigade; and he carried out this decision although without wireless and without any means of knowing what alterations might have been made in the Brigade plans. Although he unfortunately failed to locate and join the Brigade, he boldly led his party across the Shweli River and into the Kachin Hills returning to India after a remarkable march which was the more praiseworthy in that his men were naturally depressed by the circumstances in which it had begun. His refusal to take the obvious and easy course back to the Chindwin and his choice to embark instead on a daring journey five times as long through enemy country shows this officer to be the possessor of a soldierly instinct in a high degree.

Recommended By-Temporary Lieut-Colonel P.C.Buchanan, 2nd Burma Rifles

Honour or Reward-Military Cross

Signed By-Brigadier O.C. Wingate

Commander 77th Indian Infantry Brigde.

Gazetted 16.12.1943

It is recorded in the 2nd Burma Rifles War diary for 1943, that even after arriving safely in India with his platoon, George Carne then went back into Burma around mid-May, to a place called Fort Hertz, where he awaited and welcomed more of his returning Burma Riflemen. This seems quite remarkable in view of the energy he must have expended on the operation, but is typical of the man in regards to the care and welfare of his men. After the war and having attained the Army Rank of Major, George Carne returned to England and in later life was a valued member of the West Cornwall Branch of the Burma Star Association. George sadly died in the Kerrier District of Cornwall in September 1987, his death was acknowledged in the Summer 1988 edition of the Burma Star magazine, Dekho!

Seen below are a few more images in relation to Captain Carne's time in Burma and a photograph of his brother, James Power Carne, who was awarded the Victoria Cross for his command of the 1st Battalion, the Gloucestershire Regiment during the Korean War. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, June 2016.