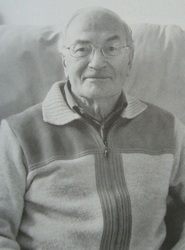

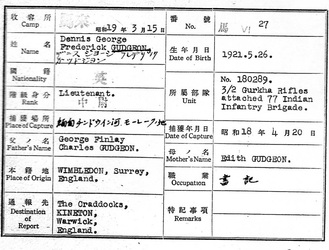

Denis George Frederick Gudgeon, or 'Gudge' to his mates.

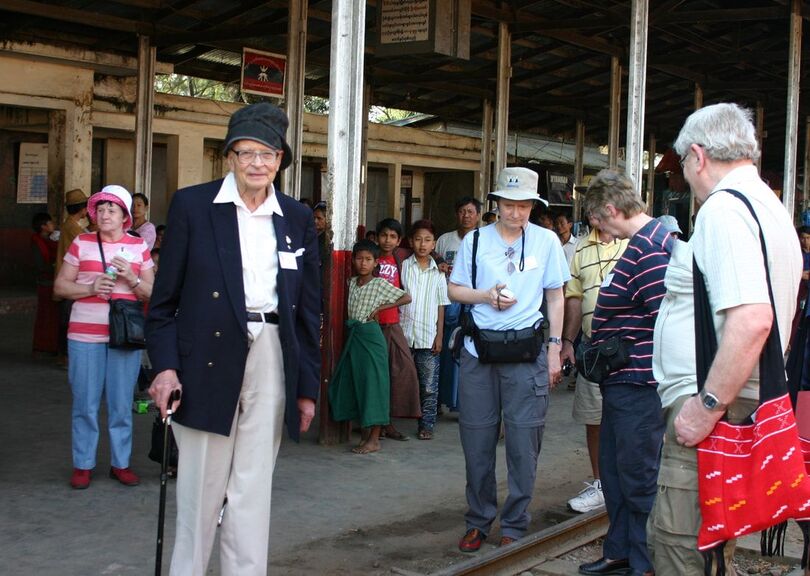

Denis Gudgeon, Burma, March 2008.

"I came into Burma on Longcloth, but I left the place wearing only a loincloth."

This was how Denis summarised his Burma Campaign experience to me in 2008. We had met on the Royal British Legion pilgrimage tour to the country in March that year and forged quite a friendship by the time the two weeks had ended.

He would prove to be an invaluable source of information, not just for me, but the group as a whole. What better value could I have hoped for on the trip, than a veteran who had not only served on Operation Longcloth, but had spent two years in Rangoon Jail as well.

He came prepared with books and papers about the expedition, but perhaps the most precious resource would turn out to be my recordings of our discussions. These were done in various different locations, but invariably the hotel bar, wherever that may have been at the time. He was always generous with his information and memories even though I sometimes I acted like an interrogator, something that he did once remark upon on a coach ride through the streets of Mandalay.

He had likened my interview technique to that of the Kempai-tai (Japanese secret police) and was not sure which had been the more formidable. Denis has been my most direct link to the men and memories of Operation Longcloth and I am so pleased I did not waste my opportunity to talk with him.

The following story will record the discussions we had, based mostly on the topics we spoke about, rather than his military career or the more well known Longcloth tales. But in order to give the reader a full understanding of what Denis's pathway was in WW2, here is a link to his Roll of honour page on the Britain at War website:

http://www.roll-of-honour.org.uk/g/html/gudgeon-denis-george-frederick.htm

Denis also left some of his memoirs and paperwork at the Imperial War Museum, this included another sound recording made in December 1991. These audios have now been placed online although the museum is still in the process of perfecting how they present them in this format. However, here is the link and hopefully his recording will soon be available to listen to in its entirety:

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80012089

This was how Denis summarised his Burma Campaign experience to me in 2008. We had met on the Royal British Legion pilgrimage tour to the country in March that year and forged quite a friendship by the time the two weeks had ended.

He would prove to be an invaluable source of information, not just for me, but the group as a whole. What better value could I have hoped for on the trip, than a veteran who had not only served on Operation Longcloth, but had spent two years in Rangoon Jail as well.

He came prepared with books and papers about the expedition, but perhaps the most precious resource would turn out to be my recordings of our discussions. These were done in various different locations, but invariably the hotel bar, wherever that may have been at the time. He was always generous with his information and memories even though I sometimes I acted like an interrogator, something that he did once remark upon on a coach ride through the streets of Mandalay.

He had likened my interview technique to that of the Kempai-tai (Japanese secret police) and was not sure which had been the more formidable. Denis has been my most direct link to the men and memories of Operation Longcloth and I am so pleased I did not waste my opportunity to talk with him.

The following story will record the discussions we had, based mostly on the topics we spoke about, rather than his military career or the more well known Longcloth tales. But in order to give the reader a full understanding of what Denis's pathway was in WW2, here is a link to his Roll of honour page on the Britain at War website:

http://www.roll-of-honour.org.uk/g/html/gudgeon-denis-george-frederick.htm

Denis also left some of his memoirs and paperwork at the Imperial War Museum, this included another sound recording made in December 1991. These audios have now been placed online although the museum is still in the process of perfecting how they present them in this format. However, here is the link and hopefully his recording will soon be available to listen to in its entirety:

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80012089

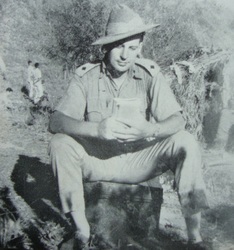

A very young Denis Gudgeon from earlier in WW2.

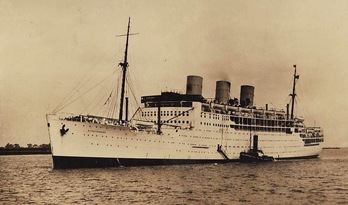

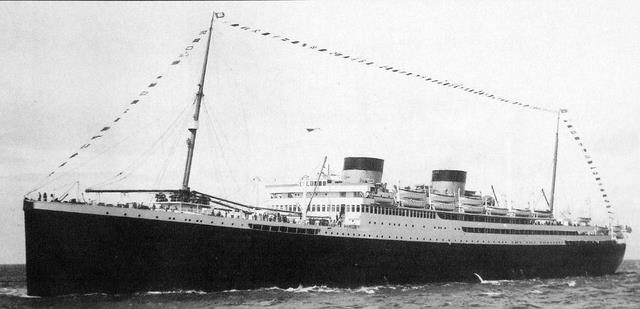

One of the first conversations I had with Denis was about his journey over to India in January 1942, originally aboard the troopship 'Strathnaver'. He had travelled on board as part of Convoy WS (Winston's Specials) 15 and the Strathnaver had taken him part of the way to the South African port of Durban.

Durban and Capetown were the regular stopping points for these convoys and many British servicemen had enjoyed the warm welcome and hospitality of their South African hosts. Durban was especially famous at this time for their 'Lady in White' or operatic soprano Perla Siedle Gibson, who would sing the new troopships in to dock with her repertoire of contemporary popular songs and arias.

Denis had a wonderful time in Durban and like many men and officers before him made a mental note to re-visit the city when the war was over. British troops, leaving their glum and war-stricken homes back in England with wives and mothers used to rationing and struggling to make ends meet, were amazed at the wealth of food and entertainment on hand in these two vibrant African cities. Capetown and Durban left an indelible mark on many men during the war years, something that they remembered with affection for the rest of their lives.

After ten days shore-leave in Durban, Denis and his fellow officers boarded the troopship 'Brittanic' and it was this ship that transported him the rest of the way to India, eventually arriving at Bombay in March 1942.

Below is an audio recording of Denis talking about his voyage and the ships he was aboard.

Durban and Capetown were the regular stopping points for these convoys and many British servicemen had enjoyed the warm welcome and hospitality of their South African hosts. Durban was especially famous at this time for their 'Lady in White' or operatic soprano Perla Siedle Gibson, who would sing the new troopships in to dock with her repertoire of contemporary popular songs and arias.

Denis had a wonderful time in Durban and like many men and officers before him made a mental note to re-visit the city when the war was over. British troops, leaving their glum and war-stricken homes back in England with wives and mothers used to rationing and struggling to make ends meet, were amazed at the wealth of food and entertainment on hand in these two vibrant African cities. Capetown and Durban left an indelible mark on many men during the war years, something that they remembered with affection for the rest of their lives.

After ten days shore-leave in Durban, Denis and his fellow officers boarded the troopship 'Brittanic' and it was this ship that transported him the rest of the way to India, eventually arriving at Bombay in March 1942.

Below is an audio recording of Denis talking about his voyage and the ships he was aboard.

Denis used to talk about his time in the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles with fondness, especially recalling his great friends and comrades from back then, people such as George Silcock, Canadian Roy MacKenzie and Harold James. He never exaggerated about his actions during Chindit training or on the operation itself, once owning up to my sister that he had not even fired his Lee Enfield rifle at the enemy during the 8 weeks he was behind their lines.

He did always stress that in his opinion the training given to him and his Gurkhas was not up to scratch, and that this left then woefully short of confidence once inside Burma. Communication was still difficult even in Mike Calvert's Column 3, with only George Silcock able to talk with the men in their native Gurkhali. In his view the Gurkha troops were far too young and inexperienced to be used in the way Wingate had planned, with some of the muleteers coming on board just days before the expedition set off in January 1943.

In 2008 Denis would become uncharacteristically quiet when wandering around the graves and memorials of his lost comrades. This was never more apparent than when he stood in front of panels 57 and 58 of the Rangoon Memorial and looked at the names of the 3/2 Gurkha Riflemen inscribed upon it. This is what he told me that day in Taukkyan War Cemetery.

"These young soldiers were at first very confused by the nature of Long range penetration, it was of course against their frank and forthright nature as fighting men. But if you took them under your wing and attempted, (and this was not easy with the language barrier), to explain the plans and theories, then they would perform the role with total commitment and many times lay down their lives doing so".

Typically of Denis, during one chat on this subject he recounted a story of how his young Gurkha company had to scramble up some nearby trees whilst on manoeuvres, when the local river had broken its banks during a sudden thunderstorm. Instead of telling me how this ended for his troops (the men had to stay up in those trees for several days) he proceeded to inform me that his precious gramophone and records had all survived the incident perched up in the branches. He had brought together quite a collection of records after some forceful bartering with the local market sellers in the town of Mhow.

Here is how Denis remembered that story:

He did always stress that in his opinion the training given to him and his Gurkhas was not up to scratch, and that this left then woefully short of confidence once inside Burma. Communication was still difficult even in Mike Calvert's Column 3, with only George Silcock able to talk with the men in their native Gurkhali. In his view the Gurkha troops were far too young and inexperienced to be used in the way Wingate had planned, with some of the muleteers coming on board just days before the expedition set off in January 1943.

In 2008 Denis would become uncharacteristically quiet when wandering around the graves and memorials of his lost comrades. This was never more apparent than when he stood in front of panels 57 and 58 of the Rangoon Memorial and looked at the names of the 3/2 Gurkha Riflemen inscribed upon it. This is what he told me that day in Taukkyan War Cemetery.

"These young soldiers were at first very confused by the nature of Long range penetration, it was of course against their frank and forthright nature as fighting men. But if you took them under your wing and attempted, (and this was not easy with the language barrier), to explain the plans and theories, then they would perform the role with total commitment and many times lay down their lives doing so".

Typically of Denis, during one chat on this subject he recounted a story of how his young Gurkha company had to scramble up some nearby trees whilst on manoeuvres, when the local river had broken its banks during a sudden thunderstorm. Instead of telling me how this ended for his troops (the men had to stay up in those trees for several days) he proceeded to inform me that his precious gramophone and records had all survived the incident perched up in the branches. He had brought together quite a collection of records after some forceful bartering with the local market sellers in the town of Mhow.

Here is how Denis remembered that story:

"So near and yet so terribly far".

Denis was part of the dispersal group led by Captain George Silcock and was happy to be so. "George had been a good friend to me in Burma and before, he filled you with confidence and of course was one of the few British Officers who could speak with our Gurkhas in their native tongue".

In the end, as it had been for many of the Chindit parties, it was the Burmese Rivers that proved the undoing for Denis and his small group of Gurkhas, I will let Denis take it from here (he then preceded to read from Harold James's book 'Across the Threshold of Battle':

"I was left on the eastern banks of the river with eleven Gurkhas and a Karen from the Burma Rifles. After an anxious search, we found a craft and bribed the boatman to take us across the Irrawaddy. I paid far too much to this man but we were desperate to catch up with George and at least this reduced my pack weight somewhat.

On the west bank there was no sign of Captain Silcock and his party who obviously could not risk waiting, and I only had maps for the Chindwin area. Fortunately, I did have a prismatic compass with which I set a course of 300 degrees. Even so, navigation was not easy as we were walking against the grain of the country, and the odd mountain range intervened."

Denis's courage and perseverance paid off, and he brought his small party to within a short distance of the Chindwin. But here the long months of marching with scarce rations and severe physical exertions demanded its price, and Denis suddenly collapsed in sheer exhaustion.

His men were anxious, but he assured them that he would soon be all right, and meanwhile to carry on while he rested. He would catch them up presently. They were rather jumpy and nervous by this stage, but made no move to leave him.

From the pages of the book, which Denis had help write he remebers: "It may seem strange now, but I do remember quite clearly telling them that it was my order that they should go on. But why I did so I cannot say. I must have been rather light-headed at the time, I suppose."

The Gurkhas eventually left him, although most reluctantly. These were not normal circumstances or they would surely have ignored his order; but they had also reached almost the last vestige of their endurance. Yet they did not go far before making camp for the night. And the next day, as Denis had not rejoined them, a search party returned to the spot where he had last been seen, but could find no trace. His Gurkhas continued to the Chindwin and eventually reached safety.

Denis had already moved on, but it would seem in the wrong direction. "I was on my own now with only my compass for guide and I realized that I must get some food urgently. Shortly afterwards I hit a track and hid beside it. I let several people pass and then selected what I thought might be a reliable person. To my surprise he spoke very good English, which, I suppose, should have made me suspicious. He was a fishmonger selling dried fish up country. I asked him how far I was to the Chindwin River and he said ten miles and that he could get me a boat."

By this time Denis was in an extremely exhausted state, but he eventually made it to a place called Tanga (phonetic pronouciation) on the east bank of the Chindwin, where he was able to rest and drink a cup of tea.

"I was drinking tea from a bone china tea cup and beginning to feel rather apprehensive when there was a commotion and I looked up to find myself staring down the muzzles of a dozen rifles."

Denis was taken to the local Japanese HQ (possibly at Mawlaik) and given a book to read. "A gentleman in a kimono came in to the room but I went on reading my book. He exploded with rage and left the room. Shortly afterwards an interpreter arrived to say, "Japanese officer very angry, you insult Emperor".

The officer returned shortly and interrogated Denis for four hours with a razor-sharp Samurai sword always pointed at his throat. "My hair stood on end, and I felt I was in an Alice in Wonderland situation, expecting at any moment the command, "Off with his head!" The whole interrogation was conducted through an interpreter, although the officer could speak and understand English perfectly well. This was just was face- saving on his part."

Denis was then taken to another basha (an improvised temporary hut) where they tried a different technique. "I was plied with saki and sweetmeats and promised this, that, and the other, but I did not fall for it. The only intelligence they got out of me was a lot of duff gen."

Please click on the audio below to listen to Denis recount these moments:

Denis was part of the dispersal group led by Captain George Silcock and was happy to be so. "George had been a good friend to me in Burma and before, he filled you with confidence and of course was one of the few British Officers who could speak with our Gurkhas in their native tongue".

In the end, as it had been for many of the Chindit parties, it was the Burmese Rivers that proved the undoing for Denis and his small group of Gurkhas, I will let Denis take it from here (he then preceded to read from Harold James's book 'Across the Threshold of Battle':

"I was left on the eastern banks of the river with eleven Gurkhas and a Karen from the Burma Rifles. After an anxious search, we found a craft and bribed the boatman to take us across the Irrawaddy. I paid far too much to this man but we were desperate to catch up with George and at least this reduced my pack weight somewhat.

On the west bank there was no sign of Captain Silcock and his party who obviously could not risk waiting, and I only had maps for the Chindwin area. Fortunately, I did have a prismatic compass with which I set a course of 300 degrees. Even so, navigation was not easy as we were walking against the grain of the country, and the odd mountain range intervened."

Denis's courage and perseverance paid off, and he brought his small party to within a short distance of the Chindwin. But here the long months of marching with scarce rations and severe physical exertions demanded its price, and Denis suddenly collapsed in sheer exhaustion.

His men were anxious, but he assured them that he would soon be all right, and meanwhile to carry on while he rested. He would catch them up presently. They were rather jumpy and nervous by this stage, but made no move to leave him.

From the pages of the book, which Denis had help write he remebers: "It may seem strange now, but I do remember quite clearly telling them that it was my order that they should go on. But why I did so I cannot say. I must have been rather light-headed at the time, I suppose."

The Gurkhas eventually left him, although most reluctantly. These were not normal circumstances or they would surely have ignored his order; but they had also reached almost the last vestige of their endurance. Yet they did not go far before making camp for the night. And the next day, as Denis had not rejoined them, a search party returned to the spot where he had last been seen, but could find no trace. His Gurkhas continued to the Chindwin and eventually reached safety.

Denis had already moved on, but it would seem in the wrong direction. "I was on my own now with only my compass for guide and I realized that I must get some food urgently. Shortly afterwards I hit a track and hid beside it. I let several people pass and then selected what I thought might be a reliable person. To my surprise he spoke very good English, which, I suppose, should have made me suspicious. He was a fishmonger selling dried fish up country. I asked him how far I was to the Chindwin River and he said ten miles and that he could get me a boat."

By this time Denis was in an extremely exhausted state, but he eventually made it to a place called Tanga (phonetic pronouciation) on the east bank of the Chindwin, where he was able to rest and drink a cup of tea.

"I was drinking tea from a bone china tea cup and beginning to feel rather apprehensive when there was a commotion and I looked up to find myself staring down the muzzles of a dozen rifles."

Denis was taken to the local Japanese HQ (possibly at Mawlaik) and given a book to read. "A gentleman in a kimono came in to the room but I went on reading my book. He exploded with rage and left the room. Shortly afterwards an interpreter arrived to say, "Japanese officer very angry, you insult Emperor".

The officer returned shortly and interrogated Denis for four hours with a razor-sharp Samurai sword always pointed at his throat. "My hair stood on end, and I felt I was in an Alice in Wonderland situation, expecting at any moment the command, "Off with his head!" The whole interrogation was conducted through an interpreter, although the officer could speak and understand English perfectly well. This was just was face- saving on his part."

Denis was then taken to another basha (an improvised temporary hut) where they tried a different technique. "I was plied with saki and sweetmeats and promised this, that, and the other, but I did not fall for it. The only intelligence they got out of me was a lot of duff gen."

Please click on the audio below to listen to Denis recount these moments:

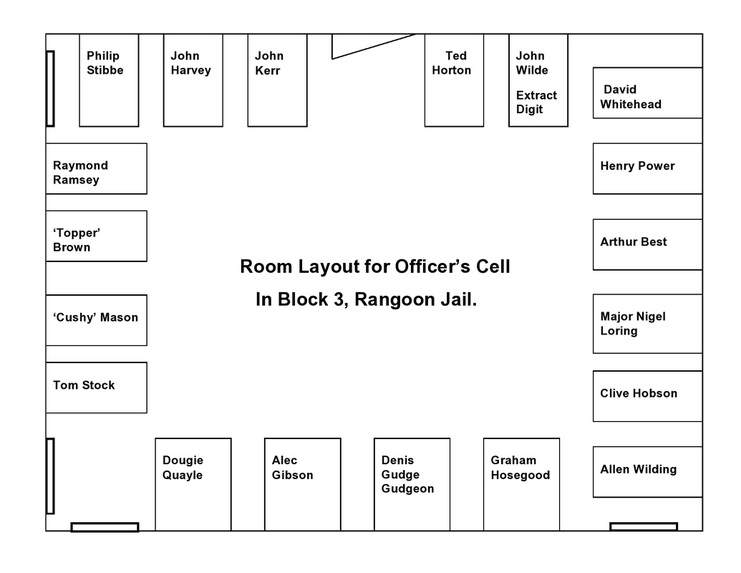

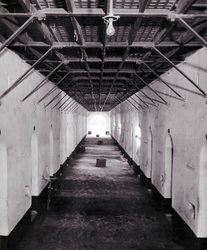

Denis continues his account with his first memories of POW life in Rangoon Jail:

"Arriving at Rangoon Central Gaol, I was thrown into solitary confinement in No. 5 Block which was the norm for all officers. We were supposed not to talk but we all did. Flight-Lieutenant MacDonald, a Beaufighter pilot from Edinburgh, used to keep watch and would whistle 'The Campbells are Coming' when the guards paid their many visits day and night, and inter-mezzo when the coast was clear."

Five weeks later, Denis was released from solitary, shortly after his twenty-second birthday, and transferred to the top floor of the two-storey communal No. 6 Block where he found himself sleeping on the floor between Graham Hosegood and Alec Gibson. "It was a comfort to have such friends from the start, and most of us were able to stay together throughout the years of captivity."

Conditions in the gaol were abysmal. The communal block had no glass windows and the monsoon rain just poured in. There was no electric lighting and the POW's simply slept on the floor, coping with bed bugs, lice, ants and mosquitoes. Washing and drinking facilities were from a long trough, but the water was frequently turned off due to the local reservoir being bombed. Sanitary conditions were very primitive, using old ammunition cases for toilet facilities within the cell and emptying these out the next day.

The POW's had no Red Cross parcels to fall back on as had those in the Western theatre of war. The staple diet was rice, and Denis was permanently hungry. What has to be remembered is that when captured he was already on a near starvation diet and so never had the opportunity to build up his strength. There was no milk or bread and the meat ration, generally of pork, was very irregular. The fresh vegetables consisted of aubergines, pumpkins, marrow and sweet potatoes. A Burmese marketeer used to come round every ten days or so and Denis was able to purchase Burmese cheroots (rough cigarettes), duck eggs, jaggery balls (a coarse brown sugar fudge) and rice toffee.

"Arriving at Rangoon Central Gaol, I was thrown into solitary confinement in No. 5 Block which was the norm for all officers. We were supposed not to talk but we all did. Flight-Lieutenant MacDonald, a Beaufighter pilot from Edinburgh, used to keep watch and would whistle 'The Campbells are Coming' when the guards paid their many visits day and night, and inter-mezzo when the coast was clear."

Five weeks later, Denis was released from solitary, shortly after his twenty-second birthday, and transferred to the top floor of the two-storey communal No. 6 Block where he found himself sleeping on the floor between Graham Hosegood and Alec Gibson. "It was a comfort to have such friends from the start, and most of us were able to stay together throughout the years of captivity."

Conditions in the gaol were abysmal. The communal block had no glass windows and the monsoon rain just poured in. There was no electric lighting and the POW's simply slept on the floor, coping with bed bugs, lice, ants and mosquitoes. Washing and drinking facilities were from a long trough, but the water was frequently turned off due to the local reservoir being bombed. Sanitary conditions were very primitive, using old ammunition cases for toilet facilities within the cell and emptying these out the next day.

The POW's had no Red Cross parcels to fall back on as had those in the Western theatre of war. The staple diet was rice, and Denis was permanently hungry. What has to be remembered is that when captured he was already on a near starvation diet and so never had the opportunity to build up his strength. There was no milk or bread and the meat ration, generally of pork, was very irregular. The fresh vegetables consisted of aubergines, pumpkins, marrow and sweet potatoes. A Burmese marketeer used to come round every ten days or so and Denis was able to purchase Burmese cheroots (rough cigarettes), duck eggs, jaggery balls (a coarse brown sugar fudge) and rice toffee.

On the tour in 2008 we all took an incredible train journey through the Burmese country and visiting places from Chindit legend. We began our sojourn in the town of Myitkhina, famous for being the obsessive focal point of 'Vinegar' Joe Stilwell's ambition back in 1945. Here we experienced our one and only thunderstorm whilst on tour. Here also a small break away group (or dispersal party if you will) formed that evening in the hotel bar.

Much whiskey flowed and our conversation centred around Denis and another member of the tour, former Cheshire Regimental RSM, David Oak. From my Burma diary pages comes this quote:

During the evening a small group of drunkards emerged as the more sober and sensible made for their beds.

This contingent was led unofficially by RSM David Oak formerly of the Cheshire’s. (From now on this man will be known purely as RSM). After dinner two bottles of Burmese whiskey appeared and one was duly dispatched by the group. A careful manoeuvring took place between RSM and his immediate superior, 2nd Lieutenant Denis Gudgeon, whereby the RSM probed to test the character of his quarry. I have to say that DG was to be no push over, and the jibes were often expertly and humorously parried.

Two anecdotes from this extremely well mannered and hilarious night stand out in my memory.

RSM. (Pretending to stab his ‘swagger stick’ into DG’s ribs). "There is an idiot on the end of this stick, sir!"

DG. "Yes sergeant, but not at this end there isn't!"

On being asked by DG what his name was, RSM replied "Smith, Sar!". DG. "How many F’s in Smiff?"

RSM. “There are no f’s in Smith, SAR!"

DG. “Well then, you must be an effing Smith then!’.

Advantage Denis I think.

I must just add here that I had throughout the evening made sure that DG did not partake of too much alcohol. I frequently watered down his drinks, but I still had to make sure that he reached the relative safety of his room on the ground floor of the hotel. And to witness his change from tourist into English gentleman at bedtime, struck in his regalia of striped pyjamas and smoking jacket.

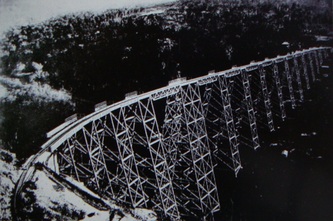

The next day I asked Denis if he had got on well with Mike Calvert, his Column Commander in 1943. He said that he never knew him that well, but obviously admired his leadership and his concern for his troops welfare. I asked specifically about Calvert’s near obsession with getting to Gokteik, and blowing the massive viaduct there, which had eluded him on the British retreat in 1942. He simply said he was just glad they (Column 3) did not have to travel any further on into Eastern Burma, as they were very hungry and totally exhausted by that time.

I noticed something in particular at our next port of call, Mogaung rail station, the entire group stepped down from the train onto the very crowded station platform. The whole place bustled with energy and it seemed as though the whole town had come out that day to welcome us. Most of us moved through the throng, smiling as we went and made our way to the awaiting transfer vehicles, Denis on the other hand sat down amongst the locals and quietly made notes in his diary. It may sound like nothing at all, but to me it showed his comfortability in an environment he had clearly experienced before.

Here are some of the other questions I asked of Denis during that train trip in 2008:

Denis, the obvious question first. What did you think of Wingate when you first met him?

DG. "It was at a TEWT session in training (Tactical Exercise Without Troops), we were all gathered around a large sand table listening to him and the other Column Commanders talk over the plans. It had been a long day and plenty of rum had been consumed. All of a sudden there was an almighty bang.....he (Wingate) had fired off his revolver to wake us all up. It certainly worked that day I can tell you. To be honest, I think he was half-mad, but these are the sorts of chaps you need at times of war. Brilliant ideas and the confidence to try them out in the field."

Denis, were you glad with hindsight to have missed the 1944 Chindit operation. Keeping in mind that most of the junior Gurkha officers on that tour did not return alive to India.

DG. "To be honest I have never thought about it in that way. I would have liked to have gone in again, especially if it was with Calvert's mob, but I could never look upon my time in Rangoon Jail as being a blessing in disguise, if that is what you mean."

Denis, on leaving Rangoon Jail in April 1945, did you ever suspect the Japanese might execute you all if things began to go wrong for them?

DG. "Not really, although they did kill anybody that fell out of that march, including my good friend Arthur Best."

I asked Denis if he remembered any of the mules from Column 3. (Calvert’s column was the only group to bring a mule back to India. Her name was Mabel).

DG. "No".

Denis, what did you think about the Burma Rifle officers and men attached to the column command?

DG."They were fantastic men, without whom the navigation through the jungle and the acquisition of food from local villages would have been impossible. They saved many lives during the dispersal."

What did you think of Mike Calvert as a leader?

DG. "Calvert always led from the front, and for that he was much admired. But we also felt that he was driven by a personal agenda. This was shown by his obsession with getting to and blowing the Gokteik viaduct."

Denis, did you ever meet the Dane Erik Petersen?

"Yes, he answered. He and some of Column 7 caught up with us when we were blowing one of the railway bridges at Nankan. Petersen may have been wounded there, but I (DG) cannot be sure."

I asked Denis if he disliked any of the officers from Column 3?

DG. "Only one, he was such a big-head and loved to make you look foolish if he could. He was a typical RAF type."

Finally, I asked DG if he was worried about meeting Her Majesty's Customs at Heathrow?

He laughed having got my joke, and said not at all. (Denis on his return to Britain after the war, landed at a RAF base in Somerset, where he duly had to pay excise duty on some silks and other presents he had brought back as gifts for the family).

Sadly for both Denis and indeed myself it was already dark when our train trundled through the areas around Nankan, the scene of Column 3's greatest triumph in March 1943. It was here that the men of 142 Commando demolished the railway line that we were now travelling upon. The train slowed down as we passed through the station with the driver giving a toot on his whistle to mark the occasion, Denis looked out of the half-opened window into the duskily lit jungle scrub and must have been many many miles away at that moment.

Much whiskey flowed and our conversation centred around Denis and another member of the tour, former Cheshire Regimental RSM, David Oak. From my Burma diary pages comes this quote:

During the evening a small group of drunkards emerged as the more sober and sensible made for their beds.

This contingent was led unofficially by RSM David Oak formerly of the Cheshire’s. (From now on this man will be known purely as RSM). After dinner two bottles of Burmese whiskey appeared and one was duly dispatched by the group. A careful manoeuvring took place between RSM and his immediate superior, 2nd Lieutenant Denis Gudgeon, whereby the RSM probed to test the character of his quarry. I have to say that DG was to be no push over, and the jibes were often expertly and humorously parried.

Two anecdotes from this extremely well mannered and hilarious night stand out in my memory.

RSM. (Pretending to stab his ‘swagger stick’ into DG’s ribs). "There is an idiot on the end of this stick, sir!"

DG. "Yes sergeant, but not at this end there isn't!"

On being asked by DG what his name was, RSM replied "Smith, Sar!". DG. "How many F’s in Smiff?"

RSM. “There are no f’s in Smith, SAR!"

DG. “Well then, you must be an effing Smith then!’.

Advantage Denis I think.

I must just add here that I had throughout the evening made sure that DG did not partake of too much alcohol. I frequently watered down his drinks, but I still had to make sure that he reached the relative safety of his room on the ground floor of the hotel. And to witness his change from tourist into English gentleman at bedtime, struck in his regalia of striped pyjamas and smoking jacket.

The next day I asked Denis if he had got on well with Mike Calvert, his Column Commander in 1943. He said that he never knew him that well, but obviously admired his leadership and his concern for his troops welfare. I asked specifically about Calvert’s near obsession with getting to Gokteik, and blowing the massive viaduct there, which had eluded him on the British retreat in 1942. He simply said he was just glad they (Column 3) did not have to travel any further on into Eastern Burma, as they were very hungry and totally exhausted by that time.

I noticed something in particular at our next port of call, Mogaung rail station, the entire group stepped down from the train onto the very crowded station platform. The whole place bustled with energy and it seemed as though the whole town had come out that day to welcome us. Most of us moved through the throng, smiling as we went and made our way to the awaiting transfer vehicles, Denis on the other hand sat down amongst the locals and quietly made notes in his diary. It may sound like nothing at all, but to me it showed his comfortability in an environment he had clearly experienced before.

Here are some of the other questions I asked of Denis during that train trip in 2008:

Denis, the obvious question first. What did you think of Wingate when you first met him?

DG. "It was at a TEWT session in training (Tactical Exercise Without Troops), we were all gathered around a large sand table listening to him and the other Column Commanders talk over the plans. It had been a long day and plenty of rum had been consumed. All of a sudden there was an almighty bang.....he (Wingate) had fired off his revolver to wake us all up. It certainly worked that day I can tell you. To be honest, I think he was half-mad, but these are the sorts of chaps you need at times of war. Brilliant ideas and the confidence to try them out in the field."

Denis, were you glad with hindsight to have missed the 1944 Chindit operation. Keeping in mind that most of the junior Gurkha officers on that tour did not return alive to India.

DG. "To be honest I have never thought about it in that way. I would have liked to have gone in again, especially if it was with Calvert's mob, but I could never look upon my time in Rangoon Jail as being a blessing in disguise, if that is what you mean."

Denis, on leaving Rangoon Jail in April 1945, did you ever suspect the Japanese might execute you all if things began to go wrong for them?

DG. "Not really, although they did kill anybody that fell out of that march, including my good friend Arthur Best."

I asked Denis if he remembered any of the mules from Column 3. (Calvert’s column was the only group to bring a mule back to India. Her name was Mabel).

DG. "No".

Denis, what did you think about the Burma Rifle officers and men attached to the column command?

DG."They were fantastic men, without whom the navigation through the jungle and the acquisition of food from local villages would have been impossible. They saved many lives during the dispersal."

What did you think of Mike Calvert as a leader?

DG. "Calvert always led from the front, and for that he was much admired. But we also felt that he was driven by a personal agenda. This was shown by his obsession with getting to and blowing the Gokteik viaduct."

Denis, did you ever meet the Dane Erik Petersen?

"Yes, he answered. He and some of Column 7 caught up with us when we were blowing one of the railway bridges at Nankan. Petersen may have been wounded there, but I (DG) cannot be sure."

I asked Denis if he disliked any of the officers from Column 3?

DG. "Only one, he was such a big-head and loved to make you look foolish if he could. He was a typical RAF type."

Finally, I asked DG if he was worried about meeting Her Majesty's Customs at Heathrow?

He laughed having got my joke, and said not at all. (Denis on his return to Britain after the war, landed at a RAF base in Somerset, where he duly had to pay excise duty on some silks and other presents he had brought back as gifts for the family).

Sadly for both Denis and indeed myself it was already dark when our train trundled through the areas around Nankan, the scene of Column 3's greatest triumph in March 1943. It was here that the men of 142 Commando demolished the railway line that we were now travelling upon. The train slowed down as we passed through the station with the driver giving a toot on his whistle to mark the occasion, Denis looked out of the half-opened window into the duskily lit jungle scrub and must have been many many miles away at that moment.

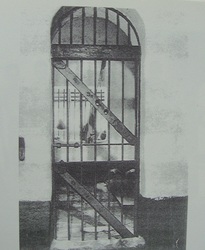

Denis outside Warehouse No. 1 in 2008.

'Rice sacks then Liberation.'

One of the most enjoyable moments on our trip in 2008 was when we all took the journey down to Rangoon Docks. All three of the veterans on the tour had spent sometime in the vicinity of the docks during their Burma campaign and all became animated on their return, none more so than Denis.

"These docks were the central hub of my working life for many months, they were an intense acreage of cranes, warehouses, ships and what seemed like thousands of 'coolie labourers', one of which was me."

While we were all at the docks he reminisced about his time there and even recognised one of the warehouses where he had placed cargo many times, this was 'Go-down No. 1' (see photograph opposite). He told us that this cargo was usually sacks of rice weighing over 200lbs. Some 25 years later Denis required extensive spinal surgery, for this he holds the rice sacks culpable.

The other story he tells about his time as a POW was that one day his work party was sent out to build an air raid shelter for their Japanese hosts. Allied bombing raids had become more and more frequent and the Japanese guards were becoming very concerned about these unwelcome aerial visits.

The prison guard with the working party carefully paced out the area to be dug, then left Denis and his team to perform the task, while he saw to more pressing matters. Denis, thinking quickly moved the markers in at either end, thus dramatically reducing the area to be excavated. Everyone set to work with pick and shovel and in a few short hours had completed the initial excavation. This back fired totally on the POW's as the guard was so elated by the speed of the group’s work that they were chosen for all such duties thereafter. Denis was not a popular man for quite a while.

Before we move on, here is how Denis remembers first entering Rangoon Jail in May 1943:

One of the most enjoyable moments on our trip in 2008 was when we all took the journey down to Rangoon Docks. All three of the veterans on the tour had spent sometime in the vicinity of the docks during their Burma campaign and all became animated on their return, none more so than Denis.

"These docks were the central hub of my working life for many months, they were an intense acreage of cranes, warehouses, ships and what seemed like thousands of 'coolie labourers', one of which was me."

While we were all at the docks he reminisced about his time there and even recognised one of the warehouses where he had placed cargo many times, this was 'Go-down No. 1' (see photograph opposite). He told us that this cargo was usually sacks of rice weighing over 200lbs. Some 25 years later Denis required extensive spinal surgery, for this he holds the rice sacks culpable.

The other story he tells about his time as a POW was that one day his work party was sent out to build an air raid shelter for their Japanese hosts. Allied bombing raids had become more and more frequent and the Japanese guards were becoming very concerned about these unwelcome aerial visits.

The prison guard with the working party carefully paced out the area to be dug, then left Denis and his team to perform the task, while he saw to more pressing matters. Denis, thinking quickly moved the markers in at either end, thus dramatically reducing the area to be excavated. Everyone set to work with pick and shovel and in a few short hours had completed the initial excavation. This back fired totally on the POW's as the guard was so elated by the speed of the group’s work that they were chosen for all such duties thereafter. Denis was not a popular man for quite a while.

Before we move on, here is how Denis remembers first entering Rangoon Jail in May 1943:

Denis went on to explain how the doctors available in Rangoon Jail had saved many lives using the scant medical supplies at their disposal. He remembered, "When I became seriously ill with dysentery, the only medicine I was given by the Medical Officer was charcoal and creosote pills."

Denis also suffered from hookworm, one of the many other diseases prevalent in Rangoon, others included malaria, jungle sores and beri beri, which caused the body to swell up with liquid to a grotesque size. An outbreak of smallpox sent the Japs into a great panic and they promptly vaccinated all the POW's which prevented an epidemic. But unfortunately an outbreak of cholera did occur in the jail, which lasted about two weeks and caused the deaths of about 10 men.

"When someone died his remains were sewn into rice sacks by our Jewish tailor, Pte. Berkovitch. We all stood to attention in the compound whilst the funeral party marched past. The body was then taken in a tonga (a two-wheeled cart) to the English Cantonment Cemetery which was next door to the Zoo. I took several services there amid the roars of the lions and tigers and trumpeting of elephants and the Jap guards telling me to hurry up all the time."

For more information about the Chindit burials and the English Cantonment Cemetery please click the link below and search down to the bottom of the page:

Memorials and Cemeteries

From Denis's own memoirs, taken from the book 'Across the Threshold of Battle' by Harold James:

"The clothing we wore was of a very scanty nature and consisted of a 'C' string and our prison number tag ( Denis's number was 27), with no footwear. I lost my number tag once, and was sentenced to thirty-six hours in solitary confinement without food or water. In Japanese eyes it was a total disgrace for us to have been taken prisoner.

The guards used to turn nasty at the slightest provocation, especially after Allied air-raids. Their favourite method of humiliation was to slap the POW's across the face as hard as they could with both hands or, on occasion, with a bamboo cane. Several men were badly beaten up with rifle butts.

Keeping in touch with the outside world was a very important part of maintaining morale. The POW's had a very efficient news-gathering service even if they did not possess a radio. The sources included a newspaper the Japs published in English called Greater Asia which was a propaganda sheet but the POW's were able to read between the lines. Once the guards rushed into my block, the day after Wingate was killed in an aircrash, waving the newspaper with its banner headlines, shouting "Wingate Shinde, Wingate Shinde!"

Information was also gleaned from friendly Burmese on working parties, indiscreet guards and recently captured POW's. All this was collated by Squadron Leader Duckenfield on a war map concealed in the false bottom of a wooden box. He used to shade in the areas which had been re-taken by Allied forces.

The POW's were made to carry out heavy work such as unloading rice sacks from barges to godowns (warehouse buildings), building air- raid shelters, gun emplacements, sweeping the streets and gardening. The working parties used to steal books from private houses and high schools and smuggle them into the jail. We had a library of over 200 books and I did a lot of reading."

Here is how Denis remembered the burials of men who sadly perished in Rangoon Jail:

Denis also suffered from hookworm, one of the many other diseases prevalent in Rangoon, others included malaria, jungle sores and beri beri, which caused the body to swell up with liquid to a grotesque size. An outbreak of smallpox sent the Japs into a great panic and they promptly vaccinated all the POW's which prevented an epidemic. But unfortunately an outbreak of cholera did occur in the jail, which lasted about two weeks and caused the deaths of about 10 men.

"When someone died his remains were sewn into rice sacks by our Jewish tailor, Pte. Berkovitch. We all stood to attention in the compound whilst the funeral party marched past. The body was then taken in a tonga (a two-wheeled cart) to the English Cantonment Cemetery which was next door to the Zoo. I took several services there amid the roars of the lions and tigers and trumpeting of elephants and the Jap guards telling me to hurry up all the time."

For more information about the Chindit burials and the English Cantonment Cemetery please click the link below and search down to the bottom of the page:

Memorials and Cemeteries

From Denis's own memoirs, taken from the book 'Across the Threshold of Battle' by Harold James:

"The clothing we wore was of a very scanty nature and consisted of a 'C' string and our prison number tag ( Denis's number was 27), with no footwear. I lost my number tag once, and was sentenced to thirty-six hours in solitary confinement without food or water. In Japanese eyes it was a total disgrace for us to have been taken prisoner.

The guards used to turn nasty at the slightest provocation, especially after Allied air-raids. Their favourite method of humiliation was to slap the POW's across the face as hard as they could with both hands or, on occasion, with a bamboo cane. Several men were badly beaten up with rifle butts.

Keeping in touch with the outside world was a very important part of maintaining morale. The POW's had a very efficient news-gathering service even if they did not possess a radio. The sources included a newspaper the Japs published in English called Greater Asia which was a propaganda sheet but the POW's were able to read between the lines. Once the guards rushed into my block, the day after Wingate was killed in an aircrash, waving the newspaper with its banner headlines, shouting "Wingate Shinde, Wingate Shinde!"

Information was also gleaned from friendly Burmese on working parties, indiscreet guards and recently captured POW's. All this was collated by Squadron Leader Duckenfield on a war map concealed in the false bottom of a wooden box. He used to shade in the areas which had been re-taken by Allied forces.

The POW's were made to carry out heavy work such as unloading rice sacks from barges to godowns (warehouse buildings), building air- raid shelters, gun emplacements, sweeping the streets and gardening. The working parties used to steal books from private houses and high schools and smuggle them into the jail. We had a library of over 200 books and I did a lot of reading."

Here is how Denis remembered the burials of men who sadly perished in Rangoon Jail:

Denis continues:

"Release from captivity came in a sudden and unexpected manner. The POW's were divided into 'fit to march' and 'unfit to march' categories. I fell into the former, and left Rangoon Central Jail for the last time on 25th April 1945. They marched us northwards towards Pegu, then we headed east along a single track railway towards Waw. The senior British Officer, Brigadier Hobson, was called out to speak with the commandant. Half an hour later the Brigadier shouted out to us all, 'We are free! We are free!' The Jap guards disappeared into the blue, never to be seen again by us. The date was 29th April, 1945.

But our troubles were by no means over as we were in no-man's-land between the advancing 14th Army and the retreating Jap forces. The members of the RAF under Duckenfield made a huge Union Jack from pieces of cloth supplied by friendly villagers and set a haystack on fire.

Suddenly all hell was let loose. I cowered behind a mango tree whilst three Indian Air Force Hurricanes strafed us from the sky. Each plane made three passes and I was lucky to escape with bullet grazes to my right ankle and knee. Brigadier Hobson was not so lucky and he was our only fatal casualty, shot through the right kidney.

Towards dusk an American POW pilot contacted the British Forces, and the POW's were officially liberated the next day by soldiers of the West Yorkshire Regiment. We were taken to an air-strip and a RAF Dakota flew us via Akyab to Comilla. But even then my flight was not without incident as Japanese ack-ack explosions puffed all around our plane, the pilot taking evasive action on many occasions."

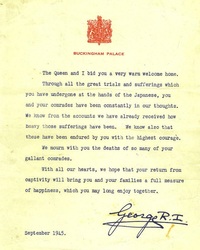

Denis finally arrived home on 31st August 1945 after periods in various hospitals in India recovering from his time as a prisoner of war.

"I had some lengths of silk as presents for my family, and had to pay duty to HM Customs and Excise at Merryfield Airfield near Taunton. I knew I must be home!"

To see some amazing footage of the liberation of the POW's at Pegu, please click on the link below:

Pegu Marchers Liberation

There now follows another of the short recordings of Denis talking about his good friend Arthur Best, who was killed by the Japanese guards during the Pegu march in April 1945. Arthur had become too weak and exhausted to walk any further, the Japanese bayoneted him and left him by the roadside to die.

This is followed by a photographic gallery of some of the people, places and other items mentioned by Denis or in the narrative above, please click on any image to enlarge:

"Release from captivity came in a sudden and unexpected manner. The POW's were divided into 'fit to march' and 'unfit to march' categories. I fell into the former, and left Rangoon Central Jail for the last time on 25th April 1945. They marched us northwards towards Pegu, then we headed east along a single track railway towards Waw. The senior British Officer, Brigadier Hobson, was called out to speak with the commandant. Half an hour later the Brigadier shouted out to us all, 'We are free! We are free!' The Jap guards disappeared into the blue, never to be seen again by us. The date was 29th April, 1945.

But our troubles were by no means over as we were in no-man's-land between the advancing 14th Army and the retreating Jap forces. The members of the RAF under Duckenfield made a huge Union Jack from pieces of cloth supplied by friendly villagers and set a haystack on fire.

Suddenly all hell was let loose. I cowered behind a mango tree whilst three Indian Air Force Hurricanes strafed us from the sky. Each plane made three passes and I was lucky to escape with bullet grazes to my right ankle and knee. Brigadier Hobson was not so lucky and he was our only fatal casualty, shot through the right kidney.

Towards dusk an American POW pilot contacted the British Forces, and the POW's were officially liberated the next day by soldiers of the West Yorkshire Regiment. We were taken to an air-strip and a RAF Dakota flew us via Akyab to Comilla. But even then my flight was not without incident as Japanese ack-ack explosions puffed all around our plane, the pilot taking evasive action on many occasions."

Denis finally arrived home on 31st August 1945 after periods in various hospitals in India recovering from his time as a prisoner of war.

"I had some lengths of silk as presents for my family, and had to pay duty to HM Customs and Excise at Merryfield Airfield near Taunton. I knew I must be home!"

To see some amazing footage of the liberation of the POW's at Pegu, please click on the link below:

Pegu Marchers Liberation

There now follows another of the short recordings of Denis talking about his good friend Arthur Best, who was killed by the Japanese guards during the Pegu march in April 1945. Arthur had become too weak and exhausted to walk any further, the Japanese bayoneted him and left him by the roadside to die.

This is followed by a photographic gallery of some of the people, places and other items mentioned by Denis or in the narrative above, please click on any image to enlarge:

WW1 Memorial Scroll for Frederick G. Gudgeon.

"There is an awful lot of coffee in Brazil."

On the 2nd March 2008 we were in an old fifty seater Mercedes bus and struggling to make the steep climb into the former British Hill station of Maymyo. This is when Denis told me all about his childhood and how on at least two occasions he had travelled over to his father's coffee plantation in Brazil, during the long summer holidays away from school. This plantation was located near the city of Santos, Denis proudly proclaimed, "You know, where Pele comes from!"

It must have been a great adventure for a boy of 7 or 8 to be placed aboard a ship at Southampton and then to cross the Atlantic and visit such places as Buenos Aires and Montevideo. Denis said it was "Wildly exciting, if a little daunting to be aboard ship and heading across the seas."

Denis' father, George had made the same journey many times himself as a boy, when he visited his father Gustavus Gudgeon, who had plied his trade as a coffee merchant in Rio de Janeiro in the early 1900's.

As you can see from the WW1 Memorial Scroll pictured to the left, Denis was named, at least in part, after his Uncle Frederick. All three Gudgeon brothers served in WW1 at some point or another and I was able to write to Denis in September 2008 with some details about their service.

Dear Denis,

I hope this letter finds you well. I have recently been looking on the Internet for some information on my Great Grandfather from WW1, where he was awarded the Military Medal for an act of bravery at Ypres in 1917. As I was looking through the lists from the London Gazette for his citation details, I came across some references to your father. I hope you do not mind but it caught my interest and I have done a little research on him for you. You are probably already aware of all the information I have found, but I thought you might like to see it anyway.

He (George F.C. Gudgeon) was posted during his time in the Hertfordshire Regiment to the Portuguese Division. My guess is that due to your family connections in Brazil he must have been seconded for his language expertise. As you may know the Portuguese Division fought at Neuve Chappelle, but were all but destroyed by the German Artillery barrage in late 1917.

I have obtained small sections of the Herts. War diary for WW1 and your father is mentioned several times (copies with this letter). He seems to have been promoted several times in quick succession during the war. It does not mention his MC (Military Cross) award here, but you will see this award mentioned in the copies of the London Gazette supplements (also with this letter). He also has a MID (Mention in Despatches) to his name recorded on the War Diary.

After some research about his Military Cross, I discovered that it was awarded for an act of bravery in the face of the enemy. It is suggested that your father was somehow captured by the Germans around 22/03/1918, and that, after some time as a POW, he had escaped with some other men and rejoined his unit. Officers were awarded MC’s for any act of escape or evasion, under Army Order 193/1919.

I have also included your father’s MIC (Medal Card), which is basically his Army details and information card. As you can see it shows his address at the time and which medals he was entitled too. It also shows he was awarded the Soldiers Wound Badge on the 12/06/1919, and that he retired from the Army on the 30/09/1921 with the rank of Captain/Adjutant.

I have included the same documents for your Uncle Frederick, who as you know, was killed in 1915 at Gallipoli. Also included are Frederick's Commonwealth Grave details for the Helles Memorial, and a copy of the WW1 scroll sent to the bereaved families after the war. Frederick has a file on his war service held at the National Archives at Kew. The reference number if you are ever able to read it is WO 339/2395. As an extra piece of information, it is noted that your father collected his brother’s medals for the family in 1921.

This brings me nicely on to your Uncle Stanley. There is a website on the Internet about Civilian POW’s in WW1, and it mentions a Stanley Gudgeon. Is this yet another Gudgeon that has spent some time as a prisoner of war Denis? Below is a short write up about him in what I think is a book about the camp at Ruhleben.

Stanley H. Gudgeon

19 year old Ruhleben inmate Stanley H. Gudgeon was noted in The Times of August 11th 1915, as being the brother of Captain F. C. Gudgeon, and of G. F. C. Gudgeon.

Gudgeon (Stanley) was noted in the second issue of In Ruhleben Camp (June 1915, p.14) as having played for the Varsities team against the Rest of Ruhleben, in the Ruhleben Cricket League. Gudgeon was further noted in the same issue (p.22) as being an injured English player during a series of friendly rugby internationals in the camp.

A postcard written by Stanley Gudgeon was addressed to Gustavus Gudgeon, Esq, c/o George E. Magan Esq, 59 Wall Street, New York. The card was dated December 19th 1916 and states that Gudegon was interned in Barrack 3, Box 16.

For more information about the Ruhleben Civlian POW Camp, please click on the link below;

http://ruhleben.tripod.com/index.html

Denis was pleased to receive this information about his father and his two Uncles. He then told me that Uncle Stanley had also been in Paris in 1940 and had only just avoided being taken prisoner by the advancing German Army. I could not resist pulling his leg about the seemingly historical need for all Gudgeons to end up as prisoners of war. He saw the humorous side of this remark and replied, "It was almost compulsory I'm afraid."

Another photographic gallery now, showing images of Denis from the Royal British Legion pilgrimage to Burma in March 2008. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

On the 2nd March 2008 we were in an old fifty seater Mercedes bus and struggling to make the steep climb into the former British Hill station of Maymyo. This is when Denis told me all about his childhood and how on at least two occasions he had travelled over to his father's coffee plantation in Brazil, during the long summer holidays away from school. This plantation was located near the city of Santos, Denis proudly proclaimed, "You know, where Pele comes from!"

It must have been a great adventure for a boy of 7 or 8 to be placed aboard a ship at Southampton and then to cross the Atlantic and visit such places as Buenos Aires and Montevideo. Denis said it was "Wildly exciting, if a little daunting to be aboard ship and heading across the seas."

Denis' father, George had made the same journey many times himself as a boy, when he visited his father Gustavus Gudgeon, who had plied his trade as a coffee merchant in Rio de Janeiro in the early 1900's.

As you can see from the WW1 Memorial Scroll pictured to the left, Denis was named, at least in part, after his Uncle Frederick. All three Gudgeon brothers served in WW1 at some point or another and I was able to write to Denis in September 2008 with some details about their service.

Dear Denis,

I hope this letter finds you well. I have recently been looking on the Internet for some information on my Great Grandfather from WW1, where he was awarded the Military Medal for an act of bravery at Ypres in 1917. As I was looking through the lists from the London Gazette for his citation details, I came across some references to your father. I hope you do not mind but it caught my interest and I have done a little research on him for you. You are probably already aware of all the information I have found, but I thought you might like to see it anyway.

He (George F.C. Gudgeon) was posted during his time in the Hertfordshire Regiment to the Portuguese Division. My guess is that due to your family connections in Brazil he must have been seconded for his language expertise. As you may know the Portuguese Division fought at Neuve Chappelle, but were all but destroyed by the German Artillery barrage in late 1917.

I have obtained small sections of the Herts. War diary for WW1 and your father is mentioned several times (copies with this letter). He seems to have been promoted several times in quick succession during the war. It does not mention his MC (Military Cross) award here, but you will see this award mentioned in the copies of the London Gazette supplements (also with this letter). He also has a MID (Mention in Despatches) to his name recorded on the War Diary.

After some research about his Military Cross, I discovered that it was awarded for an act of bravery in the face of the enemy. It is suggested that your father was somehow captured by the Germans around 22/03/1918, and that, after some time as a POW, he had escaped with some other men and rejoined his unit. Officers were awarded MC’s for any act of escape or evasion, under Army Order 193/1919.

I have also included your father’s MIC (Medal Card), which is basically his Army details and information card. As you can see it shows his address at the time and which medals he was entitled too. It also shows he was awarded the Soldiers Wound Badge on the 12/06/1919, and that he retired from the Army on the 30/09/1921 with the rank of Captain/Adjutant.

I have included the same documents for your Uncle Frederick, who as you know, was killed in 1915 at Gallipoli. Also included are Frederick's Commonwealth Grave details for the Helles Memorial, and a copy of the WW1 scroll sent to the bereaved families after the war. Frederick has a file on his war service held at the National Archives at Kew. The reference number if you are ever able to read it is WO 339/2395. As an extra piece of information, it is noted that your father collected his brother’s medals for the family in 1921.

This brings me nicely on to your Uncle Stanley. There is a website on the Internet about Civilian POW’s in WW1, and it mentions a Stanley Gudgeon. Is this yet another Gudgeon that has spent some time as a prisoner of war Denis? Below is a short write up about him in what I think is a book about the camp at Ruhleben.

Stanley H. Gudgeon

19 year old Ruhleben inmate Stanley H. Gudgeon was noted in The Times of August 11th 1915, as being the brother of Captain F. C. Gudgeon, and of G. F. C. Gudgeon.

Gudgeon (Stanley) was noted in the second issue of In Ruhleben Camp (June 1915, p.14) as having played for the Varsities team against the Rest of Ruhleben, in the Ruhleben Cricket League. Gudgeon was further noted in the same issue (p.22) as being an injured English player during a series of friendly rugby internationals in the camp.

A postcard written by Stanley Gudgeon was addressed to Gustavus Gudgeon, Esq, c/o George E. Magan Esq, 59 Wall Street, New York. The card was dated December 19th 1916 and states that Gudegon was interned in Barrack 3, Box 16.

For more information about the Ruhleben Civlian POW Camp, please click on the link below;

http://ruhleben.tripod.com/index.html

Denis was pleased to receive this information about his father and his two Uncles. He then told me that Uncle Stanley had also been in Paris in 1940 and had only just avoided being taken prisoner by the advancing German Army. I could not resist pulling his leg about the seemingly historical need for all Gudgeons to end up as prisoners of war. He saw the humorous side of this remark and replied, "It was almost compulsory I'm afraid."

Another photographic gallery now, showing images of Denis from the Royal British Legion pilgrimage to Burma in March 2008. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

"He was a lovely man, Graham Hosegood, a lovely man."

Why do WW2 veterans rarely speak of their war time experiences when they return home, and if they do, never to their nearest and dearest. What makes a man return to Burma after almost 65 years and re-visit places filled with personal torment and negativity? I witnessed the emotions of three such men in March 2008 and the answers to these questions were never obvious or clear-cut. But, from my vantage point looking in, certain themes seemed to emerge as the pilgrimage progressed. These were, a reflection and evaluation of what they actually achieved, a final chance to honour their fallen comrades and to seek out an acceptable closure on the past which would satisfy their own minds when they returned home.

During the early days of the tour Denis seemed to be taking everything in his stride, I did see glimmers of sentiment when we passed through areas he had previously frequented and an obvious disappointment when told that the former site of the now demolished Rangoon Jail would be off limits to us. But otherwise he was comfortable and content. Denis's demeanour unravelled on March 6th when we visited the two War Cemeteries based in Rangoon.

Here is a section taken from my Burma Diary from 2008, it will hopefully give you an insight into the thoughts and feelings of the group on that morning:

"The day of the cemetery visits had arrived. Everyone rose early so we could get on the road to Taukkyan Cemetery as soon as breakfast was over. The earlier start meant that the cool of the morning still remained as we boarded the coach. I remember that coolness well as we passed through the streets of Rangoon, and then out into it's suburbs. I was extremely emotional from the outset that day, and kept on thinking how Nan would have felt those 20 years previous, when she too had visited the cemetery.

The strange mix of emotions aboard the coach was apparent as little was spoken between the group on the journey to Taukkyan. All of us I guess had an internal battle with our feelings that day. As I stepped down from the coach at Taukkyan Cemetery I was totally overwhelmed by the way the strong morning sunlight caught the shape of the Rangoon Memorial, it was an awesome image, but brought home, straight away, the immense melancholy of the site as one reflected on it's significance and meaning. The cemetery was atmospheric, almost in an overpowering way.

Straight away you are impressed by the cemetery's stature and are stunned by the heat, sounds and all your eyes can take in across the beautifully kept grounds. I am really struggling to come to terms with how I felt walking amongst those soldiers and their spirits, especially those upon the Rangoon Memorial. Here are written the names of the men who have no known grave. On faces 3, 4, 5, 6, 57 and 58 were many names I had read about, whose exploits I have digested and put to memory. Now I stood before them, it was an incredible sensation and I found myself in tears."

After the short Remembrance Service was over we all walked freely about the cemetery grounds. I noticed that Denis had wandered away from the main group and was standing in front of one of the stone panels towards the outer edge of the memorial. He remained in this position for quite sometime, simply reading the names out in his mind, the names of ordinary Gurkha Riflemen, most of them, even now, not eighteen years old.

Later that day we visited Rangoon War Cemetery, this is where my own grandfather is buried along with the many other Chindit casualties who perished whilst inside Rangoon Jail. This was the moment, I believe, where Denis found his closure, standing over the grave of his friend and Chindit comrade, Graham Cowell Hosegood. He was deeply affected there can be no doubt.

Denis explained what had happened to Graham during our earlier discussions:

"Graham died in April 1945, from the effects of beri beri to his heart, I remember we were all praying for him each night. After the war I met up with his sister, who came to visit me at my parents house. I told her what had happened to him in Rangoon and it seemed to give some comfort to her and her family. He was a lovely, lovely man."

Denis told me that Graham had always tried to look after the men who he had been captured with, almost as though he blamed himself for their becoming prisoners in the first place.

"As our incarceration went on, men began to look after number one, it was the only way really, no one felt bad about it, survivial of the fittest quite literally. Graham and one or two others were different, but they all died. Once we were liberated and the war ended, you just didn't dwell on these things. We got home and tried to get on with life the best way we could, but looking back, few of us got away scott free."

On my research travels in regard the Operation Longcloth I was fortunate enough to make contact with a member of the Hosegood family. Liz Hosegood had been looking for information about Graham and his time in Burma and we had exchanged various documents with one and other. Understandably, Liz was very keen to meet with Denis and they arranged to do so in 2009. Sadly, Denis was not able to make the rendezvous with Liz due to health reasons.

To read more about Graham Hosegood, please click on the link below;

Graham Cowell Hosegood

Why do WW2 veterans rarely speak of their war time experiences when they return home, and if they do, never to their nearest and dearest. What makes a man return to Burma after almost 65 years and re-visit places filled with personal torment and negativity? I witnessed the emotions of three such men in March 2008 and the answers to these questions were never obvious or clear-cut. But, from my vantage point looking in, certain themes seemed to emerge as the pilgrimage progressed. These were, a reflection and evaluation of what they actually achieved, a final chance to honour their fallen comrades and to seek out an acceptable closure on the past which would satisfy their own minds when they returned home.

During the early days of the tour Denis seemed to be taking everything in his stride, I did see glimmers of sentiment when we passed through areas he had previously frequented and an obvious disappointment when told that the former site of the now demolished Rangoon Jail would be off limits to us. But otherwise he was comfortable and content. Denis's demeanour unravelled on March 6th when we visited the two War Cemeteries based in Rangoon.

Here is a section taken from my Burma Diary from 2008, it will hopefully give you an insight into the thoughts and feelings of the group on that morning:

"The day of the cemetery visits had arrived. Everyone rose early so we could get on the road to Taukkyan Cemetery as soon as breakfast was over. The earlier start meant that the cool of the morning still remained as we boarded the coach. I remember that coolness well as we passed through the streets of Rangoon, and then out into it's suburbs. I was extremely emotional from the outset that day, and kept on thinking how Nan would have felt those 20 years previous, when she too had visited the cemetery.

The strange mix of emotions aboard the coach was apparent as little was spoken between the group on the journey to Taukkyan. All of us I guess had an internal battle with our feelings that day. As I stepped down from the coach at Taukkyan Cemetery I was totally overwhelmed by the way the strong morning sunlight caught the shape of the Rangoon Memorial, it was an awesome image, but brought home, straight away, the immense melancholy of the site as one reflected on it's significance and meaning. The cemetery was atmospheric, almost in an overpowering way.

Straight away you are impressed by the cemetery's stature and are stunned by the heat, sounds and all your eyes can take in across the beautifully kept grounds. I am really struggling to come to terms with how I felt walking amongst those soldiers and their spirits, especially those upon the Rangoon Memorial. Here are written the names of the men who have no known grave. On faces 3, 4, 5, 6, 57 and 58 were many names I had read about, whose exploits I have digested and put to memory. Now I stood before them, it was an incredible sensation and I found myself in tears."

After the short Remembrance Service was over we all walked freely about the cemetery grounds. I noticed that Denis had wandered away from the main group and was standing in front of one of the stone panels towards the outer edge of the memorial. He remained in this position for quite sometime, simply reading the names out in his mind, the names of ordinary Gurkha Riflemen, most of them, even now, not eighteen years old.

Later that day we visited Rangoon War Cemetery, this is where my own grandfather is buried along with the many other Chindit casualties who perished whilst inside Rangoon Jail. This was the moment, I believe, where Denis found his closure, standing over the grave of his friend and Chindit comrade, Graham Cowell Hosegood. He was deeply affected there can be no doubt.

Denis explained what had happened to Graham during our earlier discussions:

"Graham died in April 1945, from the effects of beri beri to his heart, I remember we were all praying for him each night. After the war I met up with his sister, who came to visit me at my parents house. I told her what had happened to him in Rangoon and it seemed to give some comfort to her and her family. He was a lovely, lovely man."

Denis told me that Graham had always tried to look after the men who he had been captured with, almost as though he blamed himself for their becoming prisoners in the first place.

"As our incarceration went on, men began to look after number one, it was the only way really, no one felt bad about it, survivial of the fittest quite literally. Graham and one or two others were different, but they all died. Once we were liberated and the war ended, you just didn't dwell on these things. We got home and tried to get on with life the best way we could, but looking back, few of us got away scott free."

On my research travels in regard the Operation Longcloth I was fortunate enough to make contact with a member of the Hosegood family. Liz Hosegood had been looking for information about Graham and his time in Burma and we had exchanged various documents with one and other. Understandably, Liz was very keen to meet with Denis and they arranged to do so in 2009. Sadly, Denis was not able to make the rendezvous with Liz due to health reasons.

To read more about Graham Hosegood, please click on the link below;

Graham Cowell Hosegood

St. James Church, Rowledge.

"Ah Yes! You were with Denis in Burma."

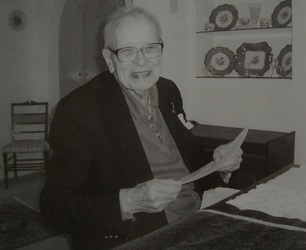

Denis Gudgeon passed away on 29th October 2010, he was 89 years old.

I was honoured to attend his funeral which took place on November 5th, firstly at Aldershot Crematorium and then back to St. James Church in Rowledge for the family service.

St. James was a small, but extremely beautiful church, founded in 1869 and situated on the edge of the Alice Holt Forest on the Hampshire/Surrey borders.

The service was full of personal tributes about Denis, but for me the most touching, was the short reading of Henry Scott-Holland's 'Death Is Nothing At All', by Denis's grandson Tom.

Being amongst the wider Gudgeon family on this day was something I will not forget. I was more than warmly welcomed and enjoyed talking with many of them about the trip to Burma in 2008. On more than one occasion I was addressed by the opening statement of "Ah! Yes! You were with Denis in Burma." Of course I replied, "Yes I was. But only the second time you understand." I think the family were pleased to learn a little more about Denis and his time during WW2, well I do hope so anyway.

To explain my own feelings, here is my Chindit Research Diary for that day:

Today I had the honour of attending the funeral of Denis Gudgeon, late 3/2 Gurkha Rifles and a 1943 Chindit.

I met Denis in Burma in 2008, where we spent many an hour discussing his time during WW2. He was a generous and understanding man, who accepted my incessant questioning and enquiries in good spirit. In fact, he told me he'd had an easier time with the Kempai-tai back in 1943, compared with his suffering under my interrogation.

It was a good day today, spending time with his family and sharing some of the details of his life. I simply felt that it was an honour to have been present at this Chindit's farewell, after never having had that opportunity with my own Grandad.

Denis Gudgeon passed away on 29th October 2010, he was 89 years old.

I was honoured to attend his funeral which took place on November 5th, firstly at Aldershot Crematorium and then back to St. James Church in Rowledge for the family service.

St. James was a small, but extremely beautiful church, founded in 1869 and situated on the edge of the Alice Holt Forest on the Hampshire/Surrey borders.

The service was full of personal tributes about Denis, but for me the most touching, was the short reading of Henry Scott-Holland's 'Death Is Nothing At All', by Denis's grandson Tom.

Being amongst the wider Gudgeon family on this day was something I will not forget. I was more than warmly welcomed and enjoyed talking with many of them about the trip to Burma in 2008. On more than one occasion I was addressed by the opening statement of "Ah! Yes! You were with Denis in Burma." Of course I replied, "Yes I was. But only the second time you understand." I think the family were pleased to learn a little more about Denis and his time during WW2, well I do hope so anyway.

To explain my own feelings, here is my Chindit Research Diary for that day: