Graham Cowell Hosegood

Graham Cowell Hosegood was born in October 1920 in Penarth, South Wales. It seems to me that during his sadly short life of 24 years, he never failed to impress all those he walked amongst.

He received his call-up papers on 03/09/1939 and whilst attending his first Officer Cadet Training his C/O had this to say about him: “ Very Good. He (Hosegood) has a definite love of leadership, with a strong and refreshing layer of common sense."

He was commissioned into the South Wales Borderer’s with the service number 134273 in June 1940, but his time with this regiment was to be short. Less than one month later he was transferred into the newly formed 13th battalion of the King’s Liverpool Regiment at the Jordan Hill barracks in Glasgow.

After performing the role of coastal defence, along the shores of Eastern England, in late 1941 the battalion were given orders to prepare for overseas duties in India. Graham and the battalion boarded the troopship ‘Oronsay' at Liverpool and began their 6 week voyage to the sub-continent.

The destiny of all the men of the 13th King’s changed in early summer 1942 when they became the British Infantry section of Wingate’s newly formed Long Range Penetration Brigade. Here is how one fellow Chindit described Graham to me in June 2009:

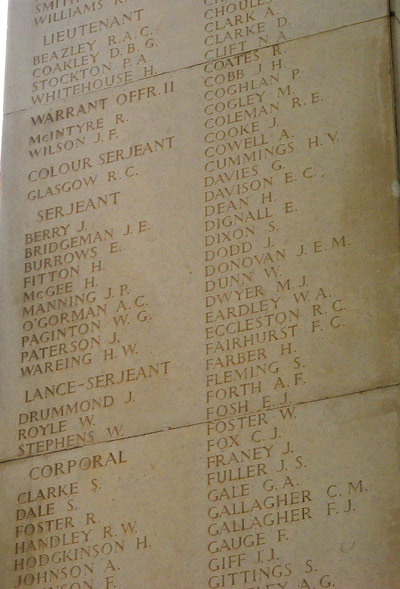

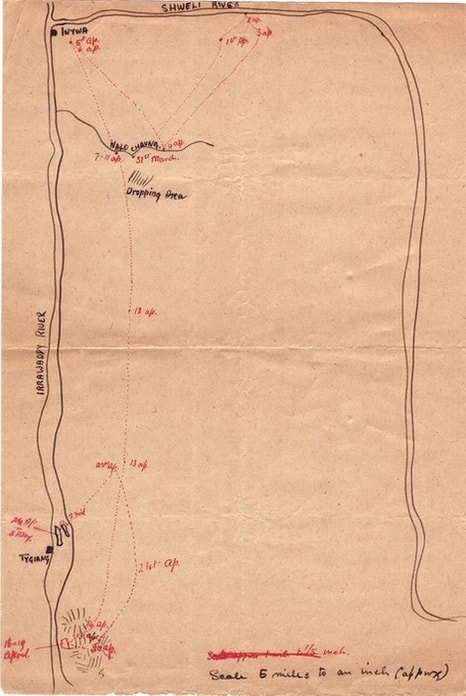

“Captain Graham Hosegood was Wingate’s Intelligence officer on ‘Longcloth’. A massively popular and well-loved man, he impressed all who knew him. Wingate relied heavily on Hosegood for instruction in planning, map work and logistical analysis. Caught close to the Irrawaddy in April 1943 along with men from Brigade HQ, he went to Rangoon Jail. Here, he continued to look out for his men until his sad death in April 1945, only weeks before the jail was liberated.”

I am going to let Graham tell his own story in this section in the form of his letters and correspondence home during WW2. My thanks must go here to Liz Hosegood and her family for allowing me to reproduce Graham's Chindit story in this unique way.

We begin with the Oronsay voyage to India, and a letter dated 19/12/1941:

My very Dear Mummy, Daddy, Joy & Sam

It does seem funny not getting your letters regularly and of course so far I have had none from home, although I expect several are on the way by now. I do hope that this will be a nice surprise for you all when it arrives, which I hope will not be too far hence. I can imagine you going to the door one morning and finding it there and there will be great excitement. I hope Joy won’t miss any trains to hear any news. I am afraid I have got rather on the ramble already and I do hope you will excuse me.

I will start by describing my surroundings; it is just 8.15 pm and I have just come up from the dining room where I have had an excellent meal and am now at a little desk in my cabin. The doors out into the corridors are all open, the porthole is open (we have special blackout covers for the portholes so that we can get some air in) and the fan is going just up above my head. I have my tropical shorts and shirt on and no tie.

I hope you got my last few letters from England all right and found them not too dull!!

We started off in a nasty misty, wet day and all looked most uninviting. We spent several nights in our clothes just in case anything happened, but so far we have had a very uneventful voyage. The first 4 or 5 days have all the stewards in their nice white jackets, small tables for about 5 or 6, all the best cutlery & table clothes etc., etc. Each meal we have a menu, dated and beautifully typed. There are always 3 or 4 choices for each course, and just to let you know something what the food is like here is an example of what I have.

Breakfast:

An orange or grapefruit,

Porridge, shredded wheat or corn flakes,

Bacon, egg & sausage or haddock, herring or kipper, toast, BUTTER, marmalade and rolls and tea.

Lunch:

Soup

Fish AND THEN steak mince or some such thing,

A pudding, cheese & coffee.

Tea is very light, a few cakes & bread & butter.

Dinner.

1, Soup.

2, Fish

3, Duck, chicken, beef, lamb or sweetbreads & 3 vegetables.

4, Sweet.

5, Desert.

6, Coffee.

Not too bad I think you will agree. We have oranges, apples, butter, cheese, fish & meat everyday. I can assure you we are all thoroughly enjoying ourselves.

I mentioned before we left that there were 4 of us in this cabin; it is a real beauty and we are extremely lucky having our own bathroom as we don’t have to queue up every time we want a bath. The cabin is on the port side, D Deck and in the centre. As I said before it is one of the best suites on board.

The last few days have been really wonderful. The sea is as calm as a millpond and as blue as can be, just like in 1937. The sunsets are a magnificent sight; the sky is always a lovely red and it reminds me of being on the farm in summer looking out over the wheat fields. It is hard to believe that you will be in the middle of winter with rain, mist, and dark nights beginning at 4 o’clock and going on till 8 in the morning. I do not hope it is not too cold at home and that you aren’t getting any air raids. It is funny but here most of us have lost touch almost completely with what is happening all over the world. There are quite a number of loudspeakers all over the ship and they broadcast the overseas news from London 3 or 4 times everyday. Sometimes we don’t. It all depends if we can be bothered to be there at the right time. From what I gather though the Russians are doing well & we seem to have bucked up again in Libya. I wonder what you all think of having America & Japan in the war?

We are having a very easy time and are all thoroughly enjoying ourselves. Bill & I were only saying yesterday we wouldn’t mind doing this until the end of the war, as it was so pleasant. We get up at about 7, soon after the steward had brought us our early cup of tea and then we go up onto the top deck in the sun, and just stroll up and down until breakfast at 8.45. There are a lot of officers & our batch is the second sitting at all meals. After breakfast we wonder out to our parade deck where all the men are at about 9.45. We wait about there for half an hour or so while the inspection is going on down in the men's deck by the captain & then perhaps do a little PT. The men have there dinner at 12 so we are then free until 1.30 when we have our lunch. After that nothing else happens and we either go to sleep or go & sit up in the sun until tea at 4.30. We have our dinner at 7.30.

Actually this week I have been what is called Men's Deck Officer, and you have to see that the men get their meals all right, and be there when the captain inspects the coys sleeping area. The men are not as well off as us; they sleep, eat & live generally all in one place; they are very cramped as well & have hammocks which at first they found very strange. However, they are thoroughly enjoying themselves as well and have never had such good food before.

We have to go very carefully with our fresh water as we are not the only ones here & it has got to go round a long way. The baths are salt water ones. Unfortunately we have no swimming baths onboard. This last week all the officers have been very busy censoring letters. We get 40 or 50 each to do most days and it takes several hours at a time.

Now that the hot weather has come on we are drinking a lot of lime juice and orangeade and I suppose most of us are drinking 5 or 6 Pints everyday!!

I do hope you are all well and although this won’t reach you in time for Xmas I will again send you all the very best and hope you will have had a very happy one. I am keeping very well and am getting brown already, but I am making certain I don’t get too much of this hot sun. Do look after yourselves very well and I am longing for your letters. I hope to be able to send another one off myself fairly soon.

There are some Hindustani classes being given on board and several of us are going along too them. We get about 3 lessons a week but so far we have only had 1 lesson. We have got a very good concert party on board form amongst the troops and they give us some good entertainment. The ship also plays gramophone records, which are relayed by the loudspeakers so we have some music as well.

Joan will be quite a big girl when I get back and John will be at school I suppose. I wonder how long it will be until it is all over.

Well there is not much more now, as I have exhausted all my news. Again all the very best, and I only wish you could be enjoying the sunshine here too.

Hope little Sam's itching is quite better. Am off to bed now, so God bless & all the best.

With ever & ever so much love to all.

From Graham.

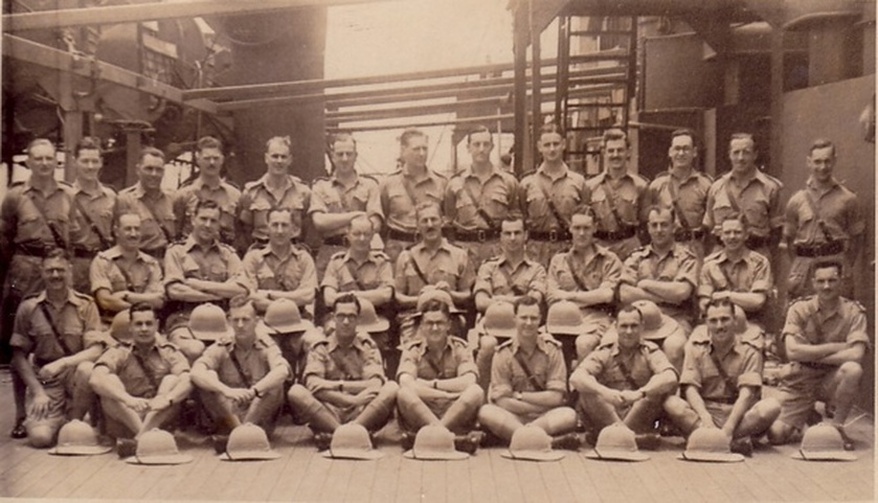

Below is a photograph of the 13th King's officers aboard the troopship Oronsay taken in early 1942. Graham is front row fourth from the right as we look.

He received his call-up papers on 03/09/1939 and whilst attending his first Officer Cadet Training his C/O had this to say about him: “ Very Good. He (Hosegood) has a definite love of leadership, with a strong and refreshing layer of common sense."

He was commissioned into the South Wales Borderer’s with the service number 134273 in June 1940, but his time with this regiment was to be short. Less than one month later he was transferred into the newly formed 13th battalion of the King’s Liverpool Regiment at the Jordan Hill barracks in Glasgow.

After performing the role of coastal defence, along the shores of Eastern England, in late 1941 the battalion were given orders to prepare for overseas duties in India. Graham and the battalion boarded the troopship ‘Oronsay' at Liverpool and began their 6 week voyage to the sub-continent.

The destiny of all the men of the 13th King’s changed in early summer 1942 when they became the British Infantry section of Wingate’s newly formed Long Range Penetration Brigade. Here is how one fellow Chindit described Graham to me in June 2009:

“Captain Graham Hosegood was Wingate’s Intelligence officer on ‘Longcloth’. A massively popular and well-loved man, he impressed all who knew him. Wingate relied heavily on Hosegood for instruction in planning, map work and logistical analysis. Caught close to the Irrawaddy in April 1943 along with men from Brigade HQ, he went to Rangoon Jail. Here, he continued to look out for his men until his sad death in April 1945, only weeks before the jail was liberated.”

I am going to let Graham tell his own story in this section in the form of his letters and correspondence home during WW2. My thanks must go here to Liz Hosegood and her family for allowing me to reproduce Graham's Chindit story in this unique way.

We begin with the Oronsay voyage to India, and a letter dated 19/12/1941:

My very Dear Mummy, Daddy, Joy & Sam

It does seem funny not getting your letters regularly and of course so far I have had none from home, although I expect several are on the way by now. I do hope that this will be a nice surprise for you all when it arrives, which I hope will not be too far hence. I can imagine you going to the door one morning and finding it there and there will be great excitement. I hope Joy won’t miss any trains to hear any news. I am afraid I have got rather on the ramble already and I do hope you will excuse me.

I will start by describing my surroundings; it is just 8.15 pm and I have just come up from the dining room where I have had an excellent meal and am now at a little desk in my cabin. The doors out into the corridors are all open, the porthole is open (we have special blackout covers for the portholes so that we can get some air in) and the fan is going just up above my head. I have my tropical shorts and shirt on and no tie.

I hope you got my last few letters from England all right and found them not too dull!!

We started off in a nasty misty, wet day and all looked most uninviting. We spent several nights in our clothes just in case anything happened, but so far we have had a very uneventful voyage. The first 4 or 5 days have all the stewards in their nice white jackets, small tables for about 5 or 6, all the best cutlery & table clothes etc., etc. Each meal we have a menu, dated and beautifully typed. There are always 3 or 4 choices for each course, and just to let you know something what the food is like here is an example of what I have.

Breakfast:

An orange or grapefruit,

Porridge, shredded wheat or corn flakes,

Bacon, egg & sausage or haddock, herring or kipper, toast, BUTTER, marmalade and rolls and tea.

Lunch:

Soup

Fish AND THEN steak mince or some such thing,

A pudding, cheese & coffee.

Tea is very light, a few cakes & bread & butter.

Dinner.

1, Soup.

2, Fish

3, Duck, chicken, beef, lamb or sweetbreads & 3 vegetables.

4, Sweet.

5, Desert.

6, Coffee.

Not too bad I think you will agree. We have oranges, apples, butter, cheese, fish & meat everyday. I can assure you we are all thoroughly enjoying ourselves.

I mentioned before we left that there were 4 of us in this cabin; it is a real beauty and we are extremely lucky having our own bathroom as we don’t have to queue up every time we want a bath. The cabin is on the port side, D Deck and in the centre. As I said before it is one of the best suites on board.

The last few days have been really wonderful. The sea is as calm as a millpond and as blue as can be, just like in 1937. The sunsets are a magnificent sight; the sky is always a lovely red and it reminds me of being on the farm in summer looking out over the wheat fields. It is hard to believe that you will be in the middle of winter with rain, mist, and dark nights beginning at 4 o’clock and going on till 8 in the morning. I do not hope it is not too cold at home and that you aren’t getting any air raids. It is funny but here most of us have lost touch almost completely with what is happening all over the world. There are quite a number of loudspeakers all over the ship and they broadcast the overseas news from London 3 or 4 times everyday. Sometimes we don’t. It all depends if we can be bothered to be there at the right time. From what I gather though the Russians are doing well & we seem to have bucked up again in Libya. I wonder what you all think of having America & Japan in the war?

We are having a very easy time and are all thoroughly enjoying ourselves. Bill & I were only saying yesterday we wouldn’t mind doing this until the end of the war, as it was so pleasant. We get up at about 7, soon after the steward had brought us our early cup of tea and then we go up onto the top deck in the sun, and just stroll up and down until breakfast at 8.45. There are a lot of officers & our batch is the second sitting at all meals. After breakfast we wonder out to our parade deck where all the men are at about 9.45. We wait about there for half an hour or so while the inspection is going on down in the men's deck by the captain & then perhaps do a little PT. The men have there dinner at 12 so we are then free until 1.30 when we have our lunch. After that nothing else happens and we either go to sleep or go & sit up in the sun until tea at 4.30. We have our dinner at 7.30.

Actually this week I have been what is called Men's Deck Officer, and you have to see that the men get their meals all right, and be there when the captain inspects the coys sleeping area. The men are not as well off as us; they sleep, eat & live generally all in one place; they are very cramped as well & have hammocks which at first they found very strange. However, they are thoroughly enjoying themselves as well and have never had such good food before.

We have to go very carefully with our fresh water as we are not the only ones here & it has got to go round a long way. The baths are salt water ones. Unfortunately we have no swimming baths onboard. This last week all the officers have been very busy censoring letters. We get 40 or 50 each to do most days and it takes several hours at a time.

Now that the hot weather has come on we are drinking a lot of lime juice and orangeade and I suppose most of us are drinking 5 or 6 Pints everyday!!

I do hope you are all well and although this won’t reach you in time for Xmas I will again send you all the very best and hope you will have had a very happy one. I am keeping very well and am getting brown already, but I am making certain I don’t get too much of this hot sun. Do look after yourselves very well and I am longing for your letters. I hope to be able to send another one off myself fairly soon.

There are some Hindustani classes being given on board and several of us are going along too them. We get about 3 lessons a week but so far we have only had 1 lesson. We have got a very good concert party on board form amongst the troops and they give us some good entertainment. The ship also plays gramophone records, which are relayed by the loudspeakers so we have some music as well.

Joan will be quite a big girl when I get back and John will be at school I suppose. I wonder how long it will be until it is all over.

Well there is not much more now, as I have exhausted all my news. Again all the very best, and I only wish you could be enjoying the sunshine here too.

Hope little Sam's itching is quite better. Am off to bed now, so God bless & all the best.

With ever & ever so much love to all.

From Graham.

Below is a photograph of the 13th King's officers aboard the troopship Oronsay taken in early 1942. Graham is front row fourth from the right as we look.

The next letter is dated 24/01/1942 and describes amongst other things the battalion's stay over in Durban and how well treated they were by the locals. As with all the letters used, I have left the narrative exactly as it was written at the time. You may notice that the name Durban does not actually feature in the letter, this I would presume is down to Army censorship of sensitive information.

My very Dear Mummy, Daddy, Joy & Sam

Well here I am starting my third letter to you and we are still on the sea. I am writing this, at the moment at any rate, up on one of the top decks in the sunshine. We are back once more in what in this part of the world is winter but to all of us it is still much warmer than we ever get at home. During the hours of between about 9-4 you daren’t get out too much in the open without your topee on. As I think I have said in one of my letters before we don’t generally write our letters much before we get into port and this will be my last letter from on board.

We have had quite a lot of experiences since my last letter and have had a very, very good time. We spent several very good days ashore and saw all kinds of interesting things. We arrived soon after 7a.m and the town from the sea looked wonderful, the sun was shining and a morning mist was just rising. We could see all kinds of big white skyscrapers near the sea front while a little way behind on small hills, something like those surrounding Cardiff were all the residential houses. After we had docked we at last got off our ship and were put into trains, which took us out to a rest camp a few miles away. It was wonderful to be on land again and the few nights ashore were grand. I had a tent to myself and we were provided with beds, sheets, mattresses & blankets etc. To get into the town there were two methods. The first was by train and the second by taxi. We went by the taxi the whole time as the trains were so frightfully packed and it was a case of fighting for a place & then most likely having to stand. The taxi used to cost about 7/6 - 10/- a time but with the 4 or 5 of us in at a time it didn’t come to very much each. At night time it was lovely getting back to the camp and getting into bed with a little hurricane lamp. This wasn’t really necessary as there were hundreds of electric lights outside which lit the whole place up beautifully. The noise of the crickets was terrific and reminded me of the noise they used to make at night when we were at the Warren.

The town itself was magnificent very modern with these skyscrapers, big wide streets and huge shops. The majority of the people were white but there were a lot of natives as well. Really it seemed extremely English in the ways and manners of the people, but it looked like one of the lovely American towns you see on the films. The white people never mixed with the black, each having their own shopping areas, their own part of the beach to bathe on, their own public lavatories and the blacks never entering the hotels.

The people were extremely kind to us all and our men were well looked after. Our ‘little bunch’ were also lucky as on of Brian’s aunts lived there and gave us a very good time. One afternoon she took us out in her car to a little bathing beach about 15 miles away. We had a grand bathe and then a good tea of ice cream, scones, cream, jam, cakes and tea. We had several meals at her house and from her balcony you looked right out over the town and across the bay and the lights were so wonderful I can’t describe how grand it was. We were not with her the whole time and did a lot of wandering on our own. We had several dinners at a hotel right on the front; the food was not rationed in any way and you got a full 9-course meal for 6/6. The fruit we had was delicious. There were peaches, bananas, oranges and about 6 varieties of their own fruit the names of which I am afraid I don’t remember.

Sunday In the hotels all the waiters were black and we found out from Brian’s aunt that instead of having white maids, nearly everyone used to keep 2 black boys; one as the cook, the other for the housework. I must say I didn’t fancy it very much although we would get used to it after a time.

We were allowed to travel on the buses and trams for nothing and all the cinema and theatre tickets were reduced for us. Actually I wasn’t at one cinema!! I would like to have seen a bit more of the surrounding country but unfortunately there wasn’t time. I have got quite a lot of photographs of the place, that I bought, but am unable to send them on yet at any rate, on account of censorship.

At last it was time to pack up and get back to the ship. I don’t know why but we had to change our ship and this time we got onto one which in peace time is a lovely ship, but which had been knocked about so much as a trooper that inside she was almost disgusting. We were packed very tight. However, we set sail and had more or less made up our minds to make the best of things. When suddenly after only a few hours out we turned round and headed straight back into port. We were all delighted and thought we would get a few more days leave as we found that something had gone wrong with one of the engines. However, next morning we were put onto another ship and we left the same evening. This one is a real beauty: very modern and extremely comfortable. I think the Broomfields would be interested. The cabins are really huge and although there are 7 of us in my cabin we are very well off. There is Bill, Brian, Leslie, Blackburne, Neville & another boy called Freddie Jones. The food is I think a bit better even than our original ship. We have plenty of deck space where we can lounge about in deck chairs and play deck games, and there is also a wonderful open air swimming pool where we all spend as much time as we can. We only get certain times to go in as there are so many that want to use it. The water is changed twice every day and when we get it, it is always just fresh.

I do hope that you will have received the cablegram; please excuse the rather weird wording but you had to choose a few phrases that were laid down. It was done with groups of figures, and what I sent was 3 groups which cost me 2/6. I also hope that the stockings I sent Joy will have reached you by the time you get this. I only hope they will fit one of you. You may be able to swank off to Joan & Maureen with some real silk stockings!! I also sent 3 prs to Mary and a cablegram too. I shall send another cable as soon as we get settled in. The first one I sent would be delayed a couple of weeks I expect, so that we should be well away from the place & the enemy get no chance to find us. I don’t know but I rather expect that sometime or other you will get a letter from Brian’s aunt, just letting you know that she saw us.

We are still getting most perfect weather and all of us are extremely well. I have got very brown but am not letting the sun get on my body. By gradual stages my arms and legs are now lovely & brown.

I thought of Joy a lot last Friday and do hope she had a lovely birthday. I do so wonder what you all did? I am also going to wish Daddy a very, very happy birthday as well. I hope it will reach you in time. I think it will.

We get overseas news regularly form London and I hope the raids in the S.W. Have not been anywhere near you. It is no good asking you anything about what you think of the war, because by the time this reaches you, the present day news will be so out of date. At the moment, however, just to give the latest news I will mention that during the week the Russians retook the town of Mozjaisk on the Moscow front.

I can’t say yet whether I shall have a chance of seeing Maureen’s people, but if I do I will let them know that she is still about’!!

We have had no rough weather except for those first few days out from England, and the last few weeks you couldn’t tell you were moving unless you are actually watching the sea. There is no vibration or anything like that. We have seen some lovely sunsets as well and I only wish I could have taken some photos of them. A lot of the people are getting tired of seeing nothing but water and as I said before I should love to see some nice grass fields and all the big oak trees down Westbourne Road.

I do so wonder if you have had any snow; it seems incredible to think of such a thing. I hope little Sam is very well & I suppose he still sits on the backdoor step barking furiously at the balloons.

I don’t know whether I shall, but I am hoping to learn to ride a horse & play tennis reasonably well while I am away. I have some idea of bridge but won’t join any bridge clubs. Some people have done nothing but play bridge ever since we left home.

I am sorry but I haven’t been able to get the snaps I was hoping to send you developed yet, so they will have to wait a bit longer.

We have had no letters from home yet but are hoping it won’t be long now until we get something I am longing to hear how you all are and all the news. Once we get settled in I shall write every week.

Please give my love to all the necessaries including Mrs Caryl. There is no more news now so shall have to close. Take no notice of the 'On Active Service' on the front. I honestly don’t know why it is there, but it is a rule & there we are.

Well look after all your little selves and God bless you all, ever, ever so much. I expect it will interest you to know I don’t forget my prayers.

So for this time goodbye.

With tons & tons & tons & tons of love to all. From Graham.

P.S Of course I have written to Mary, but any special news will you let her know.

A letter dated 08/02/1942 tells us of the battalion settling down in barracks at Secunderabad:

My very dear Mummy, Daddy, Joy & Sam,

Here I am at long last in India and we have now settled down and are all very comfy. We have been here just a week now having arrived about 11p.m a week yesterday. We got off the ship on the Friday morning. 30th of Jan, and left Bombay the same evening in the train. We spent the one night in the train and altogether we were 26 hours travelling. We came over miles and miles of plain that all seemed to be the same but it was very interesting at the little stations seeing all the Indians; the train was nothing like as comfy as those at home but they were a lot better than we imagined. The stations were nothing like as large as most at home and for most of the way there was only one line. However, for the first 100 miles or so the line was all electric so they are well advanced. The steam engine, after the electric, brought us along at about 50 for most of the way so we were not going very slowly; as fast as a lot of English trains in fact.

Here we are in what is called a cantonment; it is really just a big military camp a few miles out of Secunderabad, actually 1½ I think. We have one area with our barracks covering an area of a couple of square miles & then other units have barracks similar to us. The men have lovely big buildings in which to live, and the officers are well provided for as well. All the subalterns have a large building to themselves, a bungalow it is called, as there is no upstairs in India, at any rate in this part, and this is split up so that 2 of us have 2 rooms between us. I am in with Blackie and one room is our bedroom, the other our lounge. We have a third which is our bathroom & lavatory as well. Just a rough birds eye view of the bungalow.

The rooms are provided with big electric fans and we have good electric lights. The washing arrangements are very primitive; we bath in a big bath like you use at home in the wash house and wash in little bowls like you wash up in. However, there is an ample supply of hot water so we are all right. The water is heated on little fires out in the open just behind our bungalow. Then the lavatory is just a pan affair which the sweepers empty every time. These sweepers do very little else and are all women. Each officer has a bearer. He is the equivalent of the batman and does all the housework side of things. We are all getting very spoilt, as they won’t even let us take our boots off ourselves. They also wait on their own masters at meals. We have all had to buy a little tea set for our early morning tea as they would never dream of us having it just out of an ordinary mug. Our clothes are sent to be washed as soon as we take them off. There is a special man who does that and we are all wondering how long our clothes are going to last as the washing is done by hitting the clothes on stones and not rubbing in the ordinary way.

NB: From other documents in relation to Graham Hosegood's time in India, we know that his Bearer at Secunderabad was called Rajana.

We are feeding extremely well in the mess and I am only so sorry you can’t all be here as well. Life is extremely pleasant; at the moment I am working in the Orderly Room with the Adjutant, as there is very little Intelligence work. We work till about 4 p.m and then go back to our rooms where our bearers have a cup of tea waiting for us. After that we go down to the club and play tennis, swim, or squash. We have all joined the club as it has all sports facilities and without it we should get little or no exercise. This is a real peacetime India and no one seems to be working on a wartime basis. We are here from what we can see on garrison duties which entails nothing special.

At this time of year the weather is very pleasant. Just like a nice hot summers day at home, but the end of March, April & May are really hot I believe. Then in June & July we get the monsoons. There is no blackout here and it is glorious to see all the lights twinkling away in the distance. Hyderabad is only about 4 miles away and we can see the lights from there very easily.

We all like the Indian people round here. They are kind and very willing. We get all kinds of men up on the veranda selling all kinds of things. I bought a tennis racket from one and am hoping to be quite good at it when I return.

Down in Secunderabad there are some quite good shops 3 or 4 cinemas an banks, post offices etc: We have all hired push bikes and go round everywhere on them. I have a good one and pay 8 rupees a month for it. 1 rupee is worth about 1/6 in English money. We are gradually getting used to rupees and annas but the first few days were very awkward. Our bearer is an ordinary civilian whom we take on like a maid, & he is our own, the army having no ruling over him. We all pay our bearers 30 rupees a month. Things are apt to be a bit expensive sometimes, but I shall manage very nicely. The married subalterns are going to find it a bit hard I think.

I am very well and have been swimming every evening for the last week. I haven’t found it a bit too hot yet. I do so wonder how you all are. You seem to be having a very cold winter; I do hope it is not affecting any of you. I also hope you are getting nice peaceful nights and are not getting any raids.

We had a very enjoyable journey out here and I am glad to say that as far as I know it was without incident. We are all quite pleased to be on land again and have a bit more room to move about in, and also I find it lovely to have all my cases unpacked and be able to find my clothes easily.

I shall write a letter every week and send it by the ordinary way; they have just began Airgraph letters, and shall do my best to get one of those off every week as well.

We are all longing to get our first batch of letters; I expect it will be about another month before we get any. I do hope you have had some of mine already. I forgot exactly what number my last letter was. I believe it was no.4, so shall call this 5.

Once more I hope Daddy will have a lovely birthday and very, very, many happy returns. I hope it won’t be many birthdays till we are all together again.

With tons & tons & tons & tons of love to all, from Graham.

Then on the 21/06/1942, Chindit training begins:

My very Dear Mum, Dad, Joy & Sam,

My airgraph went off to you yesterday saying that I had had your first. It was a lovely surprise too, but I hope you will write just as many letters as I expect you fell that there is nothing quite like a real letter. The airmail P.C’s are just about as quick evidently as the airgraphs because yours of the 20th May got here in just about three weeks.

I can’t tell you how glad we are to have this cooler weather and to see clouds and rain. I do wonder what kind of a summer you are having; I hope it will be a nice fine one like this time last year. We are having to take macs everywhere with us and for the time being our topees have been put away and our English hats have been brought out. Looking back, though, over the hot months it really wasn’t too bad and it hadn’t troubled me in any way. Some of the Bn, though, have had what is called prickly heat. They are little spots which prickle terribly and you can get covered with them. I have been very lucky and only get it a bit on my forehead but Brian and several other officers alone have had on awful time with it, all over them.

We think we are off to our new station sometime at the end of the week and there is all the bother of packing again. We can’t take nearly all our stuff, only 135lbs. The rest is going to be locked up where no body will be able to touch it until after the war. It will stay here, while we with our little bit may go anywhere. I am taking my valise and one tin trunk with me, while, I shall have to leave here my other tin trunk, my suitcase, golf clubs and one other tin trunk that I have bought out here. It’s a nuisance getting you belongings all in different places but still we can only hope we shall see it again.

We are beginning to get a little bit separated at the moment. Leslie Cottrell has been told that he has got to be ready to move overseas, as they call it, at anytime. He hasn’t the slightest idea where he will be going or what he will be doing. Neville Randall and on other officer are staying here because they aren’t very strong and won’t be able to stand our new training & two other officers are away to other jobs. That means that two of our little gang are going. Now we only have Brian, Bill and myself. Then there is still Blackie but he is a lot older than the rest of us.

On Friday night Bill, Neville & I were down at Mr Groves for dinner. We had a very good meal and then sat and listened to some lovely gramophone records. It was a very quiet but thoroughly enjoyable evening. These last few evenings, since the rain started, we have had hundreds and hundreds of flying ants, I suppose you would call them, but much bigger than an ordinary ant. They are more the size of flies but with very much bigger wings. At any rate these things flutter round and round the lights and then their wings come off and you have all these horrid things crawling about the place. They have been a beastly nuisance, but we are told they are only about for 3 or 4 evenings and then you don’t see them again. I expect Pop used to get such things in W. Africa.

We haven’t had any letters this last week, and there is very little news. You will already have heard the Duke of Gloucester had been here for a short time. You may have heard on the news he was in Hyderabad. He hasn’t been up to the barracks here, but we saw his plane go over us yesterday on its way to the aerodrome.

I have been out on a couple of route marches this week and the other morning I took the company 12 miles. Fancy me doing that a few years ago! I wasn’t tired or anything after it either!

Last Monday evening we had a final guest night in the mess. It was quite a noisy business but I thoroughly enjoyed it. We had a good dinner, then we had some sing songs and finally ended up by throwing all the furniture out of the windows. I don’t suppose we shall have another party like that for sometime now as we shall be in tents and not eating nearly as well.

There seems to be a lot of talk about opening a second front at the moment. I wonder if anything will come of it? Out here things are getting very much stringer. We had our church parade this morning. It will be the last one here, and sometime within the next few days we shall have tog o round & say goodbye to the few people we know.

I do hope you are all very, very, very well. I am fine. Give my love to Mrs Davidson, Caryl, Morel etc. & I hope all are well. Has Malcolm Newton got here already? If you can get their addresses please let me have them & it might be poss to see them sometime.

We hope to have some leave in about 3 months time, after some of our training.

This is a very uninteresting letter I’m afraid, but there is no real news. Am off for my lunch now, so for the time being God bless. May not have time to write next Sunday.

Very much love to Auntie Mary & all. With tons & tons & tons & tons of love from Graham.

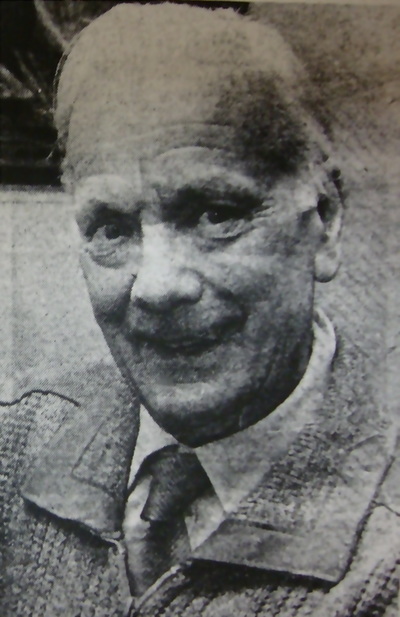

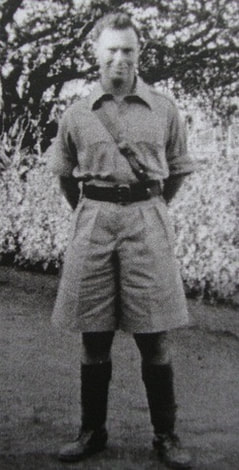

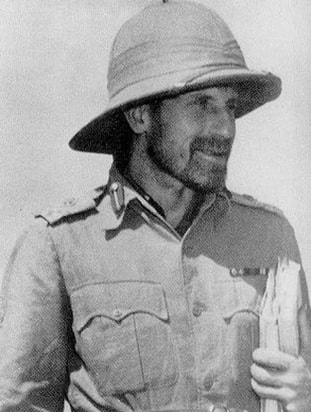

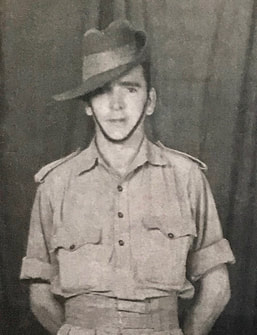

Pictured here on the left is a photo of Graham in India, probably Secunderabad. The next correspondence is an Airgraph that continues his explanation of Chindit training.

13th Bn, The King’s Regt.

C/O Patharia Camp Post Office, Patharia. India.

8.7.42

Lieut. G.C. Hosegood

My very Dear Mum, Dad, Joy & Sam.

It is I’m afraid a fortnight since I wrote to you last, but we have been so busy there has been no time for writing until today. We left Secunderabad on the 25th and got here 3 days later. The train journey was really lovely as we came through all kinds of country, wooded, sand and some parts just like home. We are now at Patharia in the Central Provinces and are living a new but very interesting life in the jungle. We training fairly hard and get one day off a week (Thursday), today is our free day. Several of us were out hunting the other day and we got a deer. My word we did have a good meal! Your letters, airgraphs & P.C’s are arriving frequently. I can't tell you how lovely it is to get them. I’m rather afraid that now we are so busy I shall only be able to get off an airgraph a week with only an occasional letter. Do hope you won’t mind, but hope to get back to the usual fairly soon. Sent a cable off yesterday from here hope it will reach you safely. I am extremely well and getting very fit. Do hope you are all very, very well. Lets hope that by next July we shall all be together again. So until next Wednesday God bless. With tons & tons love from Graham x x

On the 14th August Graham writes home and mentions in his letter the terrible drownings of CSM Bateman and Privates McKibben and Marsh, the full story of this tragic incident can be found on the Voyage and Training pages.

My very dear Mum, Dad, Joy, and Sam.

It is a long time since I have been able to write you a letter but I hope you have been getting my weekly airgraphs and I know you will understand the difficulties we have had for letter writing. We are in Saugor, a small town about 30 miles from our actual camp, doing one stage of our training. It is heavenly to have a proper roof over our heads once more and to be able to get a hot bath in the evening. We have got a proper mess going here; in the jungle we live in company messes and very rarely see officers not in our own companies (columns - crossed out). However, we are all together here and are very comfy. We have a wireless and what a change it is to hear some music and get some news. In camp we never know what is happening in the outside world, as there is no wireless and only an occasional paper. We came to Saugor last Friday and since then we have had a comparative rest and it has done us all good. Here the mess is in a bungalow and about 20 of us live here too. The rest of the officers sleep in another bungalow just across the road. The men are in a hutted camp about ¼ hr ride away on a cycle.

You will no doubt have had my airgraph saying a little about the flood. Well since then we have a new camp site in the jungle and it is much more pleasant. Nice and dry and well away from the river and danger. That night, Sunday 26th July, is one I shall never forget. On the Saturday afternoon we lost our C.S.M in what was on an ordinary day is a mere stream, but which on that day was a raging torrent, the current being so strong that it simply swept you off your feet. We had a big thick rope right across the river so we could hold on to it and thus save ourselves from being carried away. Unfortunately the C.S.M’s feet did go from under him and he was unable to hold on long enough to the rope, for us to get to him. The current then took him away at such a speed that we couldn’t find him as the water rushed away. We found his body 3 days later after the flood had subsided.

That same evening after we had had our supper two of us, another officer and I, found we had to swim about 170 yds back to our platoon area where the tents were. We plunged into the water and got over all right. We now had the main river on one side of us which was a raging river about 300 yds across and this quite still water between the rest of the company and our area, on the other side. All night the water rose and about 3.30am we had to leave our tents and go to some higher ground very near us. By 5.30 it was light and two of us, a sergeant & myself, went off to find a way, if possible, back to the company. There was only one way there was any chance and by a miracle we found that there was still a part that was not covered by water and thus that we were not quite on an island. We got the rest of the men away safely, and weren’t we glad to be away. We discovered after the water had gone down that it had been right up over our tents and unfortunately all the small things which had been lying loosely about in my tent were washed away. Luckily my tin trunk & valise were still there, but everything was soaked with dirty muddy water and a few clothes are completely ruined. But still I was lucky because the other officer lost all his kit & he had only just arrived from England.

Saturday

I have managed to buy myself another pen today from our canteen. I was very sorry to loose my other one, as I was very attached to it. Do you remember the day we went out and found it nearly in the water when we were down at Bigbury? Let’s hope it won’t be too long until we can have another lovely holiday together.

I expect you will be back from Edinburgh again now. You will have loved seeing Auntie Mary and the rest of them I know, and I am sure the little change did you good. How did the interview go? I wonder if you saw Mary at all. I don’t suppose you did because it is quite a distance between Edinburgh and Glasgow. I was surprised to hear that Joy and Mary sometimes write to each other. I wonder what she has said in her letters to make you think she is fond of me?!!

Thank you very much for forwarding the two church membership cards. Please thank Mr Gibson and tell him I hope he and his family are all well. I wonder how many people you get at church these days, but we do occasionally get a “wandering padre” to visit us, and when this happens a lot of us go along.

Our food is decidedly plain these days. The days of Secunderabad are over. We get plenty of good plain food, quite well cooked by the army cooks over little open fires. We get exactly the same kind of food as at home. We were all rather surprised we didn’t get Indian food when we got here first, but now we all say “ No thanks”!!

I am in the mess writing this, it is nearly 10pm and it is just about time for bed. There are several of us here, writing, reading and listening to the wireless. Very pleasant. Never before have we realised how little things count. A wireless, electric light, comfy chair, nice white table cloth, they all are wonderful things when you can’t get them.

Shall finish this tomorrow now as am very sleepy, do for tonight, “ God bless” and sleep well.

Sunday

I forgot to mention earlier on that we no longer have our topees but look like real Bushmen these days in hats exactly like the Australians. We look a tough lot of I don’t quite know whats!! They are very comfy and much more suitable than the topee. I hope we still have them when we return home.

Out here we get no long evenings neither any very short ones. These days it is dark by about 7.30 pm and in the winter, Jan & Feb, about 6.30 pm. We get very, very dark here, much blacker than at home.

So far I haven’t come into contact with any Penarth fellows. There must be quite a number here now. Wouldn’t it be funny if some day I bumped into John. Do let me have his address sometime as I would love to get in touch with him. Has he come out here with his battalion or was he with a draft?

You will be at Porthcawl I expect by now: How does little Sam enjoy it? He will love all the new smells I know.

Well for now I don’t think there is any more I can say, except I am very well and remarkably fit. I rather fancy I have grown a bit too, but am not sure. I do hope you all are very well and that you are getting a really nice summer. The seasons out here are all a bit strange, the nicest time being the winter between December and the end of February.

So for the time being cheerio and all the best. With tons & tons & tons & tons of love from Graham.

13th Bn, The King’s Regt.

C/O Patharia Camp Post Office, Patharia. India.

8.7.42

Lieut. G.C. Hosegood

My very Dear Mum, Dad, Joy & Sam.

It is I’m afraid a fortnight since I wrote to you last, but we have been so busy there has been no time for writing until today. We left Secunderabad on the 25th and got here 3 days later. The train journey was really lovely as we came through all kinds of country, wooded, sand and some parts just like home. We are now at Patharia in the Central Provinces and are living a new but very interesting life in the jungle. We training fairly hard and get one day off a week (Thursday), today is our free day. Several of us were out hunting the other day and we got a deer. My word we did have a good meal! Your letters, airgraphs & P.C’s are arriving frequently. I can't tell you how lovely it is to get them. I’m rather afraid that now we are so busy I shall only be able to get off an airgraph a week with only an occasional letter. Do hope you won’t mind, but hope to get back to the usual fairly soon. Sent a cable off yesterday from here hope it will reach you safely. I am extremely well and getting very fit. Do hope you are all very, very well. Lets hope that by next July we shall all be together again. So until next Wednesday God bless. With tons & tons love from Graham x x

On the 14th August Graham writes home and mentions in his letter the terrible drownings of CSM Bateman and Privates McKibben and Marsh, the full story of this tragic incident can be found on the Voyage and Training pages.

My very dear Mum, Dad, Joy, and Sam.

It is a long time since I have been able to write you a letter but I hope you have been getting my weekly airgraphs and I know you will understand the difficulties we have had for letter writing. We are in Saugor, a small town about 30 miles from our actual camp, doing one stage of our training. It is heavenly to have a proper roof over our heads once more and to be able to get a hot bath in the evening. We have got a proper mess going here; in the jungle we live in company messes and very rarely see officers not in our own companies (columns - crossed out). However, we are all together here and are very comfy. We have a wireless and what a change it is to hear some music and get some news. In camp we never know what is happening in the outside world, as there is no wireless and only an occasional paper. We came to Saugor last Friday and since then we have had a comparative rest and it has done us all good. Here the mess is in a bungalow and about 20 of us live here too. The rest of the officers sleep in another bungalow just across the road. The men are in a hutted camp about ¼ hr ride away on a cycle.

You will no doubt have had my airgraph saying a little about the flood. Well since then we have a new camp site in the jungle and it is much more pleasant. Nice and dry and well away from the river and danger. That night, Sunday 26th July, is one I shall never forget. On the Saturday afternoon we lost our C.S.M in what was on an ordinary day is a mere stream, but which on that day was a raging torrent, the current being so strong that it simply swept you off your feet. We had a big thick rope right across the river so we could hold on to it and thus save ourselves from being carried away. Unfortunately the C.S.M’s feet did go from under him and he was unable to hold on long enough to the rope, for us to get to him. The current then took him away at such a speed that we couldn’t find him as the water rushed away. We found his body 3 days later after the flood had subsided.

That same evening after we had had our supper two of us, another officer and I, found we had to swim about 170 yds back to our platoon area where the tents were. We plunged into the water and got over all right. We now had the main river on one side of us which was a raging river about 300 yds across and this quite still water between the rest of the company and our area, on the other side. All night the water rose and about 3.30am we had to leave our tents and go to some higher ground very near us. By 5.30 it was light and two of us, a sergeant & myself, went off to find a way, if possible, back to the company. There was only one way there was any chance and by a miracle we found that there was still a part that was not covered by water and thus that we were not quite on an island. We got the rest of the men away safely, and weren’t we glad to be away. We discovered after the water had gone down that it had been right up over our tents and unfortunately all the small things which had been lying loosely about in my tent were washed away. Luckily my tin trunk & valise were still there, but everything was soaked with dirty muddy water and a few clothes are completely ruined. But still I was lucky because the other officer lost all his kit & he had only just arrived from England.

Saturday

I have managed to buy myself another pen today from our canteen. I was very sorry to loose my other one, as I was very attached to it. Do you remember the day we went out and found it nearly in the water when we were down at Bigbury? Let’s hope it won’t be too long until we can have another lovely holiday together.

I expect you will be back from Edinburgh again now. You will have loved seeing Auntie Mary and the rest of them I know, and I am sure the little change did you good. How did the interview go? I wonder if you saw Mary at all. I don’t suppose you did because it is quite a distance between Edinburgh and Glasgow. I was surprised to hear that Joy and Mary sometimes write to each other. I wonder what she has said in her letters to make you think she is fond of me?!!

Thank you very much for forwarding the two church membership cards. Please thank Mr Gibson and tell him I hope he and his family are all well. I wonder how many people you get at church these days, but we do occasionally get a “wandering padre” to visit us, and when this happens a lot of us go along.

Our food is decidedly plain these days. The days of Secunderabad are over. We get plenty of good plain food, quite well cooked by the army cooks over little open fires. We get exactly the same kind of food as at home. We were all rather surprised we didn’t get Indian food when we got here first, but now we all say “ No thanks”!!

I am in the mess writing this, it is nearly 10pm and it is just about time for bed. There are several of us here, writing, reading and listening to the wireless. Very pleasant. Never before have we realised how little things count. A wireless, electric light, comfy chair, nice white table cloth, they all are wonderful things when you can’t get them.

Shall finish this tomorrow now as am very sleepy, do for tonight, “ God bless” and sleep well.

Sunday

I forgot to mention earlier on that we no longer have our topees but look like real Bushmen these days in hats exactly like the Australians. We look a tough lot of I don’t quite know whats!! They are very comfy and much more suitable than the topee. I hope we still have them when we return home.

Out here we get no long evenings neither any very short ones. These days it is dark by about 7.30 pm and in the winter, Jan & Feb, about 6.30 pm. We get very, very dark here, much blacker than at home.

So far I haven’t come into contact with any Penarth fellows. There must be quite a number here now. Wouldn’t it be funny if some day I bumped into John. Do let me have his address sometime as I would love to get in touch with him. Has he come out here with his battalion or was he with a draft?

You will be at Porthcawl I expect by now: How does little Sam enjoy it? He will love all the new smells I know.

Well for now I don’t think there is any more I can say, except I am very well and remarkably fit. I rather fancy I have grown a bit too, but am not sure. I do hope you all are very well and that you are getting a really nice summer. The seasons out here are all a bit strange, the nicest time being the winter between December and the end of February.

So for the time being cheerio and all the best. With tons & tons & tons & tons of love from Graham.

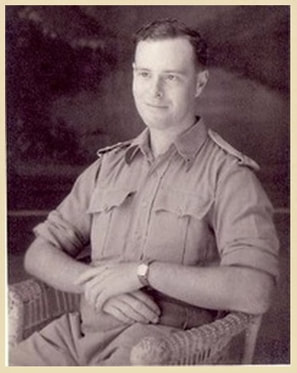

Pictured right is a photo of Wingate and his then Brigade Major 'George' Bromhead. They are talking over tactics in the map room at the Imphal Golf Club, Graham Hosegood became Wingate's Brigade Intelligence officer for operation Longcloth and would undoubtedly have spent many hours in this room.

(Picture taken from 'Wingate's Raiders', by Charles Rolo).

Here are two more pages, one a post card, the other an Airgraph, explaining his close involvement with the Brigadier.

13 Kings.

Saugor,

C.P

1.11.42

My very dear Mum, Dad, Joy & Sam,

I have had a lovely lot of letters this week from you including Dads & the other birthday letters, also a delightful little snap of Mum & Sam. Thank you so much. I have written a letter in reply to them. Yesterday I had another letter from Joy and an airgraph from Mum. So glad that a letter got home in 6 weeks. How long do these P.C’s take? We are still in the jungle but it is a very different place now that there is no rain. It is thoroughly enjoyable and our food is excellent. I only wish you could be having bacon & egg each morning, butter cream, marmalade. So you see we do all right and there is nothing to worry about. I am now up at Brigade HQ doing Bde Intelligence officer. The other fellow has a new job. I am enjoying my work immensely and at long last can use some of my Matlock experience. I have been here just a week and have settled in nicely now. There’s a lot to do but it makes the time go very quickly and I’m perfectly happy. It’s like old days when I was at Bde at Colchester. The weather is heavenly now; just like an English summer only fine every day. It’s cooler by a long way than it was 10 days ago. We don’t get the long evenings though as its dark at 7pm and not light till 7am. Do hope you all are very well. I am fine. My love to all the neighbours & when you see David next congratulate him for me. There’s a chance of a few days leave this month but nothing definite yet. Tons & tons of love from Gra.

Airgraph

Captain G.C Hosegood

15th Jan .43.

My very Dear Mum, Dad, Joy and Sam,

I haven’t been able to get a line off to you for a fortnight as things once more have been very busy. I have been away with the Brigadier and seen a lot of interesting places. We left Jhansi on New Years Eve and went first of all to Delhi where we spent 24 hrs. We stayed at a first class hotel called Maidens Hotel which is in Old Delhi but did our work out at New Delhi, which is about 5 miles away. Then, don’t get alarmed; I had my first trip in an aeroplane when we flew from Delhi to Calcutta. I thoroughly enjoyed it and feel quite an old hand in the air already. That trip took us about 8 hrs and it was wonderful to see the Ganges from the air. We spent one night in Calcutta and them flew up to Assam the next day. We spent 5 days there at places I can’t mention, and then went back to Calcutta last Sunday where we stayed until this morning. We had a lot of work to do there but it was lovely to be in a nice big city again and see all the people. I saw three films there and the food was excellent. We went back to Calcutta by train and at one spot we had to cross the Bamaputra River by a ferry. The boat was just like the old stem wheelers you see on the films going up and down the Mississippi. Today we flew back Assam where I am at present. Hope you got my cable that I sent off yesterday. Am very well do hope you all are.

Tons love Graham.

P.S Shall be writing a letter in next few days.

The final two pieces of correspondence from Graham, are a postcard and telegram sent home from just inside the Burmese jungle, during and shortly after the crossing of the Chindwin River:

13/02/1943

My very dear Mum, Dad, Joy,

Once again we are camping with just the sky for a roof. The weather is just nice and we don’t think we are likely to get drenched especially now that the dry weather period is here until May.

Letters for a bit are going to be a bit short as there is going to be no time for writing, but you will be getting a card or airgraph once a month from someone who will be writing for me. I am very well and all of us are in great spirits. Do hope you are all very well. Spring will be just about with you again when you get this. Hope I shall be home for next spring. Very many happy returns for you birthday Dad, So for now, tons & tons of love from Graham.

Telegram

18th Feb 1943.

Very fit and well. Will write wherever possible much love Hosegood.

Outlined below is a blank version of the monthly postcard, that was sent out to all the families of Longcloth personnel during the operation. These were standardized correspondence and were sent out to the next of kin, regardless of the status of their loved one. Only after the majority of the men had returned to India (roughly by early July) were families informed that their man had been killed or was missing in action.

Copy of Annexure D, ‘Airgraph’ Form for Next of Kin of B.O’s and B.O.R’s

Taken from Wingate’s Report on Operations of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade 1943.

Headquarters, 77 Ind. Inf. Bde.

India Command Dated…………………

Dear ……………

Owing to the particular nature of the operations in which your (Husband, Son, Brother etc.),

No…………….. Rk……………… Name …………………………………………………………………. is taking part, it is regretted that he is unable to communicate with you himself. It is desired, however, to notify you that he is fit and well and will write to you as soon as circumstances permit.

You are requested to continue to correspond with him and to ask his relatives and friends to write to him as usual.

Arrangements exist whereby all such letters will be delivered to him. The change of address as above, should be noted.

Until such times as he can communicate again with you himself, a notification similar to this will be sent to you once a month.

Captain H.J. Lord

Staff Captain 77 Indian Infantry Brigade.

(Picture taken from 'Wingate's Raiders', by Charles Rolo).

Here are two more pages, one a post card, the other an Airgraph, explaining his close involvement with the Brigadier.

13 Kings.

Saugor,

C.P

1.11.42

My very dear Mum, Dad, Joy & Sam,

I have had a lovely lot of letters this week from you including Dads & the other birthday letters, also a delightful little snap of Mum & Sam. Thank you so much. I have written a letter in reply to them. Yesterday I had another letter from Joy and an airgraph from Mum. So glad that a letter got home in 6 weeks. How long do these P.C’s take? We are still in the jungle but it is a very different place now that there is no rain. It is thoroughly enjoyable and our food is excellent. I only wish you could be having bacon & egg each morning, butter cream, marmalade. So you see we do all right and there is nothing to worry about. I am now up at Brigade HQ doing Bde Intelligence officer. The other fellow has a new job. I am enjoying my work immensely and at long last can use some of my Matlock experience. I have been here just a week and have settled in nicely now. There’s a lot to do but it makes the time go very quickly and I’m perfectly happy. It’s like old days when I was at Bde at Colchester. The weather is heavenly now; just like an English summer only fine every day. It’s cooler by a long way than it was 10 days ago. We don’t get the long evenings though as its dark at 7pm and not light till 7am. Do hope you all are very well. I am fine. My love to all the neighbours & when you see David next congratulate him for me. There’s a chance of a few days leave this month but nothing definite yet. Tons & tons of love from Gra.

Airgraph

Captain G.C Hosegood

15th Jan .43.

My very Dear Mum, Dad, Joy and Sam,

I haven’t been able to get a line off to you for a fortnight as things once more have been very busy. I have been away with the Brigadier and seen a lot of interesting places. We left Jhansi on New Years Eve and went first of all to Delhi where we spent 24 hrs. We stayed at a first class hotel called Maidens Hotel which is in Old Delhi but did our work out at New Delhi, which is about 5 miles away. Then, don’t get alarmed; I had my first trip in an aeroplane when we flew from Delhi to Calcutta. I thoroughly enjoyed it and feel quite an old hand in the air already. That trip took us about 8 hrs and it was wonderful to see the Ganges from the air. We spent one night in Calcutta and them flew up to Assam the next day. We spent 5 days there at places I can’t mention, and then went back to Calcutta last Sunday where we stayed until this morning. We had a lot of work to do there but it was lovely to be in a nice big city again and see all the people. I saw three films there and the food was excellent. We went back to Calcutta by train and at one spot we had to cross the Bamaputra River by a ferry. The boat was just like the old stem wheelers you see on the films going up and down the Mississippi. Today we flew back Assam where I am at present. Hope you got my cable that I sent off yesterday. Am very well do hope you all are.

Tons love Graham.

P.S Shall be writing a letter in next few days.

The final two pieces of correspondence from Graham, are a postcard and telegram sent home from just inside the Burmese jungle, during and shortly after the crossing of the Chindwin River:

13/02/1943

My very dear Mum, Dad, Joy,

Once again we are camping with just the sky for a roof. The weather is just nice and we don’t think we are likely to get drenched especially now that the dry weather period is here until May.

Letters for a bit are going to be a bit short as there is going to be no time for writing, but you will be getting a card or airgraph once a month from someone who will be writing for me. I am very well and all of us are in great spirits. Do hope you are all very well. Spring will be just about with you again when you get this. Hope I shall be home for next spring. Very many happy returns for you birthday Dad, So for now, tons & tons of love from Graham.

Telegram

18th Feb 1943.

Very fit and well. Will write wherever possible much love Hosegood.

Outlined below is a blank version of the monthly postcard, that was sent out to all the families of Longcloth personnel during the operation. These were standardized correspondence and were sent out to the next of kin, regardless of the status of their loved one. Only after the majority of the men had returned to India (roughly by early July) were families informed that their man had been killed or was missing in action.

Copy of Annexure D, ‘Airgraph’ Form for Next of Kin of B.O’s and B.O.R’s

Taken from Wingate’s Report on Operations of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade 1943.

Headquarters, 77 Ind. Inf. Bde.

India Command Dated…………………

Dear ……………

Owing to the particular nature of the operations in which your (Husband, Son, Brother etc.),

No…………….. Rk……………… Name …………………………………………………………………. is taking part, it is regretted that he is unable to communicate with you himself. It is desired, however, to notify you that he is fit and well and will write to you as soon as circumstances permit.

You are requested to continue to correspond with him and to ask his relatives and friends to write to him as usual.

Arrangements exist whereby all such letters will be delivered to him. The change of address as above, should be noted.

Until such times as he can communicate again with you himself, a notification similar to this will be sent to you once a month.

Captain H.J. Lord

Staff Captain 77 Indian Infantry Brigade.

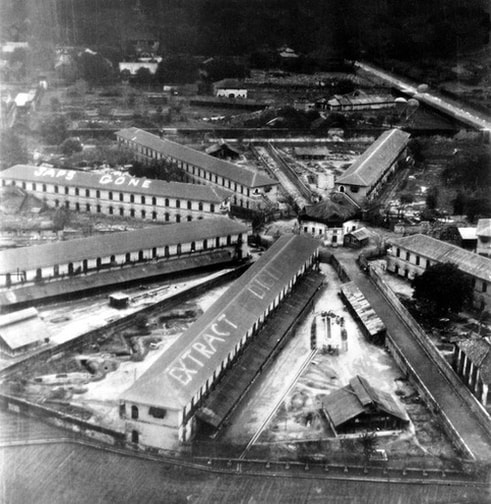

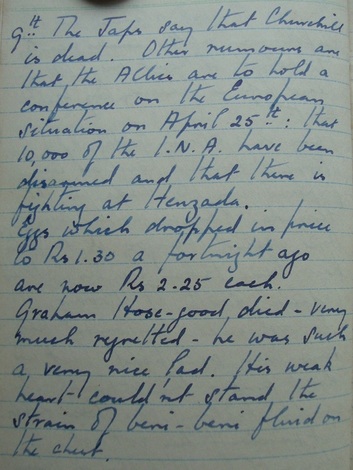

The next set of letters are from men who served with Graham on operation Longcloth, or came to know him in Rangoon Jail. The jail (pictured left in April 1945 and courtesy of the N.A.R.A) was to be home for the Chindit POW's for about two years.

The first letter was sent to Graham's parents from Sergeant James Beattie of the 13th King's and is dated 20/07/1945:

Dear Mr & Mrs Hosegood

May I take this opportunity in expressing to you both my deepest sympathy at the death of your son Captain Graham Cowell Hosegood who died in Rangoon prison on the 9-4-45 of this year. I knew Cap Hosegood from Gordon Hill days, when the 13th Bn. the Kings Reg was first formed. He was then of course first Lieut. on gas, he had an outstanding personality and was loved by all who came under him. I had the pleasure of serving him at various times throughout the Burma Campaign with Wingate who I know thought much of him.

Being a prisoner myself in Rangoon I had the privilege of being some help to him when ill with jungle sores early in 1944. Naturally a firm friendship sprung up between us, and it was a great blow to me when he died. I sat with him for some time, he did not ask me to write, although I asked him if there was anything I could do, I would gladly do it, But he only smiled and shuck his head. I feel however, he would not be all together displeased with me if I wrote to his family of whom he loved dearly, explaining the circumstances of his passing.

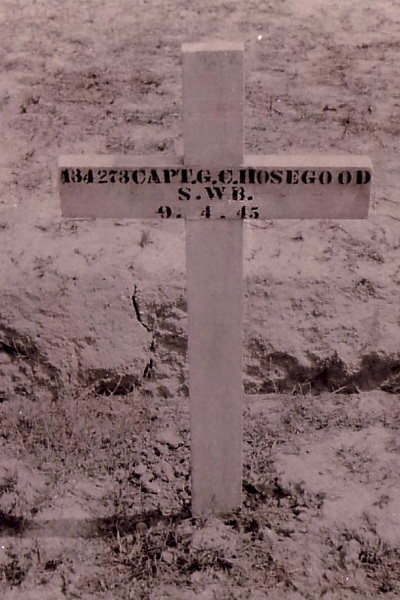

Six weeks before Xmas, your son complained of shortness of breath, but he was not alarmed. He was of course sent to hospital where once more I was of some help to him. Just before Xmas he received from the Red Cross the first batch of mail from home, some 33 postcard in all. He was over joyed with them, he showed me the photo of his Mother Sister and Dad and of course the dog. Some of the postcards were from his girl friend from Glasgow who he intended to marry. He was overjoyed with the photo, and it wasn’t long before I knew how much his family meant to him, his plans of the future after the war. His health seemed to improve and he looked forward to being sent to his own compound again fit and very happy that he had news from home and his girl friend. Then on the 6th April 45, he went down with fever he was given quinine which unfortunately weakened his heart. Although Dr Ramsey did everything in his power, and everything that could possible be done by his friends and orderlies, he passed away as I say on the 9th April 45. He was given a decent burial in Rangoon Civil Cemetery.

In conclusion, I do hope that I have not added to your deep distress. Once more I convey my deepest sympathy at your great lose. He was a fine fellow, and it is so dreadful to think that he was so near to being saved.

Yours sincerely

James Beattie

P.S I have been ill, and only now able to write.

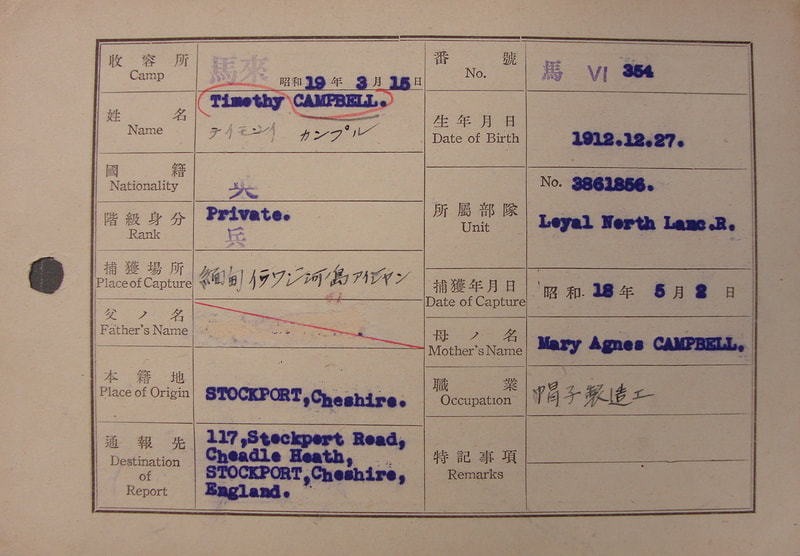

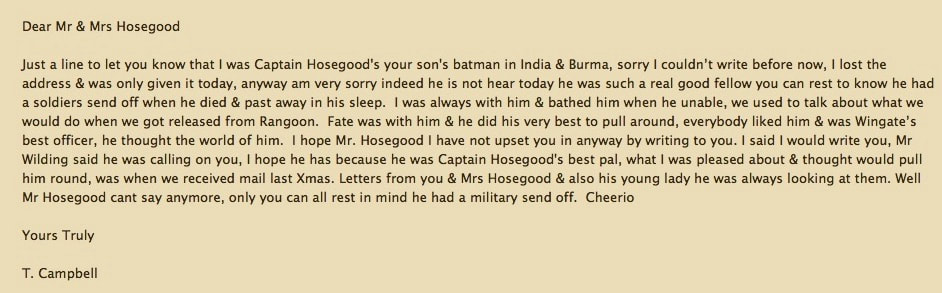

The next letter was from Graham's batman on operation Longcloth, Pte. Tim Campbell and was posted on 10/09/1945:

Dear Mr & Mrs Hosegood

Just a line to let you know that I was Captain Hosegood's your son's batman in India & Burma, sorry I couldn’t write before now, I lost the address & was only given it today, anyway am very sorry indeed he is not hear today he was such a real good fellow you can rest to know he had a soldiers send off when he died & past away in his sleep. I was always with him & bathed him when he unable, we used to talk about what we would do when we got released from Rangoon. Fate was with him & he did his very best to pull around, everybody liked him & was Wingate’s best officer, he thought the world of him. I hope Mr. Hosegood I have not upset you in anyway by writing to you. I said I would write you, Mr Wilding said he was calling on you, I hope he has because he was Captain Hosegood's best pal, what I was pleased about & thought would pull him round, was when we received mail last Xmas. Letters from you & Mrs Hosegood & also his young lady he was always looking at them. Well Mr Hosegood cant say anymore, only you can all rest in mind he had a military send off. Cheerio

Yours Truly

T. Campbell

The first letter was sent to Graham's parents from Sergeant James Beattie of the 13th King's and is dated 20/07/1945:

Dear Mr & Mrs Hosegood

May I take this opportunity in expressing to you both my deepest sympathy at the death of your son Captain Graham Cowell Hosegood who died in Rangoon prison on the 9-4-45 of this year. I knew Cap Hosegood from Gordon Hill days, when the 13th Bn. the Kings Reg was first formed. He was then of course first Lieut. on gas, he had an outstanding personality and was loved by all who came under him. I had the pleasure of serving him at various times throughout the Burma Campaign with Wingate who I know thought much of him.

Being a prisoner myself in Rangoon I had the privilege of being some help to him when ill with jungle sores early in 1944. Naturally a firm friendship sprung up between us, and it was a great blow to me when he died. I sat with him for some time, he did not ask me to write, although I asked him if there was anything I could do, I would gladly do it, But he only smiled and shuck his head. I feel however, he would not be all together displeased with me if I wrote to his family of whom he loved dearly, explaining the circumstances of his passing.

Six weeks before Xmas, your son complained of shortness of breath, but he was not alarmed. He was of course sent to hospital where once more I was of some help to him. Just before Xmas he received from the Red Cross the first batch of mail from home, some 33 postcard in all. He was over joyed with them, he showed me the photo of his Mother Sister and Dad and of course the dog. Some of the postcards were from his girl friend from Glasgow who he intended to marry. He was overjoyed with the photo, and it wasn’t long before I knew how much his family meant to him, his plans of the future after the war. His health seemed to improve and he looked forward to being sent to his own compound again fit and very happy that he had news from home and his girl friend. Then on the 6th April 45, he went down with fever he was given quinine which unfortunately weakened his heart. Although Dr Ramsey did everything in his power, and everything that could possible be done by his friends and orderlies, he passed away as I say on the 9th April 45. He was given a decent burial in Rangoon Civil Cemetery.

In conclusion, I do hope that I have not added to your deep distress. Once more I convey my deepest sympathy at your great lose. He was a fine fellow, and it is so dreadful to think that he was so near to being saved.

Yours sincerely

James Beattie

P.S I have been ill, and only now able to write.

The next letter was from Graham's batman on operation Longcloth, Pte. Tim Campbell and was posted on 10/09/1945:

Dear Mr & Mrs Hosegood

Just a line to let you know that I was Captain Hosegood's your son's batman in India & Burma, sorry I couldn’t write before now, I lost the address & was only given it today, anyway am very sorry indeed he is not hear today he was such a real good fellow you can rest to know he had a soldiers send off when he died & past away in his sleep. I was always with him & bathed him when he unable, we used to talk about what we would do when we got released from Rangoon. Fate was with him & he did his very best to pull around, everybody liked him & was Wingate’s best officer, he thought the world of him. I hope Mr. Hosegood I have not upset you in anyway by writing to you. I said I would write you, Mr Wilding said he was calling on you, I hope he has because he was Captain Hosegood's best pal, what I was pleased about & thought would pull him round, was when we received mail last Xmas. Letters from you & Mrs Hosegood & also his young lady he was always looking at them. Well Mr Hosegood cant say anymore, only you can all rest in mind he had a military send off. Cheerio

Yours Truly

T. Campbell

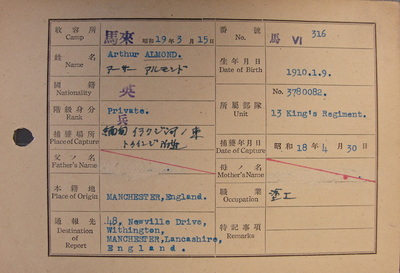

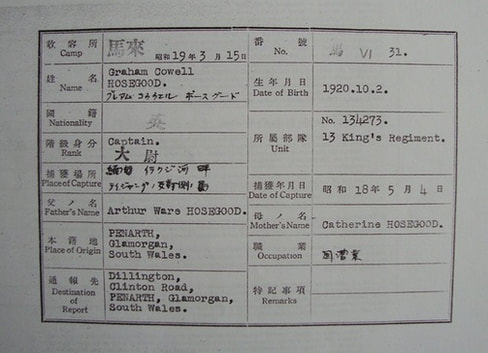

Pictured right is the front side of Graham's Japanese index card, showing all the usual details, including his date of capture 04/05/1943. The last letter in this section comes from a RAF Hurricane pilot who found himself a prisoner in Rangoon, having been shot down earlier in the war. Guy Underwood wrote to the Hosegood family in February 1947:

Dear Mr & Mrs Hosegood

It is with very mixed feelings that I am writing this letter, as I do not know if I am wise to open up a subject, which must have such sad memories for you and your daughter.

It concerns your son Graham with whom I was a prisoner of War in Burma and with whom I became very friendly. It is news which you will not have heard from the Authorities but which should make you proud and I hope, happier than perhaps you have felt up to the present.

I had been a Prisoner of War for sometime (having been shot down in flames by ach ach fire on 26th Feb 1942) when a new party of Prisoners arrived at Rangoon jail where we were kept in captivity. This new party were members of Wingate’s Brigade of which you son was Intelligence Officer.

That was my first meeting with Graham but our real friendship did not really develop for sometime, until he was transferred to the compound in which I was kept. From that time onwards we were very great friends and spent most of our spare moments together.

A number of Grahams fellow officers were prisoners in the same camp and I personally never heard a word said against him - in fact, I heard of nothing but good both from the officers and men.

As it was before being captured, so it was afterwards. He was generally liked and even during those times when things were pretty grim, he was one of those who made you feel proud to be British.

Graham and I naturally talked a lot of ‘home’ and our ‘folks’ until we almost felt that we really knew each other’s families. One thing worried us in fact, it was a worry of the whole camp - and that was whether we had been posted as Prisoners of War or not. No Red Cross System was in operation and it was not until, I believe January 1945 that we received some letters from England. Many of us were terribly depressed by having no post from home and in my own case it was not altogether surprising as I had never been reported as being a Prisoner and had been given up for lost a long time previously. However, Graham received quite a number of letters and Post Cards and was a fine friend to me in letting me share most of your news.

That is the news which I hope will make you feel happier because believe me, he was delighted and particularly so with a photograph of you which was enclosed in one of the letters. From that day onwards, Graham was one of the happiest men in the P.O.W Camp and he never gave up or lost hope until he died. It was a sad day for many of us when Graham passed away but a day of which you should be proud now that the shock of the news has worn away. He died a true Britisher and Soldier, unafraid of the future, liked by all and above all, having done his duty nobly. Perhaps you may think I am being too sentimental in which case you must forgive me - But I was his friend.

I was unable to attend the funeral but I understand that he was buried in the same portion of an English Cemetery in Rangoon where other members of our camp were buried. I have been there and it looks like a piece of England - quiet, peaceful and untouched by Japanese hands.

One more point I must tell you before I close. Graham spoke to me many times of someone called ‘Mary’ of whom he was very fond and from whom he received some mail at the same time as receiving yours. It may please her to hear of this although I of course, leave it entirely to you as to whether it might cause unnecessary unhappiness by so doing.

Well that just about completes my story and so I must close. I do hope that this letter might bring you a little happiness and possibly give you a little inside - entirely unofficial - news from one who is proud to think that he was a friend of your son.

Yours very sincerely

Guy W. Underwood. (Ex Ser/Lieut RAF).

Dear Mr & Mrs Hosegood