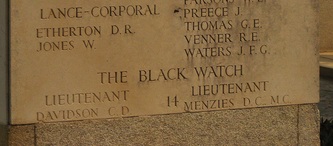

Duncan Campbell Menzies

"I recognised him instantly as Duncan Menzies, a young Australian who had been at Oxford as a Rhodes scholar on the outbreak of war, and had joined my regiment the Black Watch. This chance but fateful meeting was the more extraordinary since I had been racking my brains for a suitable column adjutant, and had decided on Duncan as the best man for the job."

He certainly was the best man for the job and Bernard Fergusson leant heavily on Menzies for almost the whole of the operation in 1943. Duncan Campbell Menzies (pictured left in his full Black Watch regalia) was one of the most revered and well loved soldiers to take part in the operation. He used his down to earth attitude to soldiering to keep morale high when things were looking quite bleak for column five and always, always led right from the front. Bernard Fergusson was fully aware that at times he as column commander had relied on Duncan not only for support, but to make vital decisions on behalf of his Major. I often wonder if Duncan's initials, that being DCM, were an accident of naming by his father, or had some kind of fateful foretelling of his life to come? There is no doubt in my mind that a DCM (Distinguished Conduct Medal) was the very least this man deserved for his WW2 service. However, Duncan himself would have been the last man to ever claim such an award. Wingate had another acronym for DCM.........."died chasing mules!"

Whatever Duncan (known to his closest friends and family as Campbell) put his mind to he excelled in, whether that be soldiering or academic achievement, those who he met along the way all remember him fondly. It was no surprise for me to learn only recently that there is a street named after him (Menzies Crescent) in his families home town of Prospect, South Australia. I have also learned during my research that one Chindit colleague (Peter Dorans) even named one of his sons after Duncan. So these examples should leave you in no doubt as to the kind of man we are honouring here in these few short paragraphs.

He certainly was the best man for the job and Bernard Fergusson leant heavily on Menzies for almost the whole of the operation in 1943. Duncan Campbell Menzies (pictured left in his full Black Watch regalia) was one of the most revered and well loved soldiers to take part in the operation. He used his down to earth attitude to soldiering to keep morale high when things were looking quite bleak for column five and always, always led right from the front. Bernard Fergusson was fully aware that at times he as column commander had relied on Duncan not only for support, but to make vital decisions on behalf of his Major. I often wonder if Duncan's initials, that being DCM, were an accident of naming by his father, or had some kind of fateful foretelling of his life to come? There is no doubt in my mind that a DCM (Distinguished Conduct Medal) was the very least this man deserved for his WW2 service. However, Duncan himself would have been the last man to ever claim such an award. Wingate had another acronym for DCM.........."died chasing mules!"

Whatever Duncan (known to his closest friends and family as Campbell) put his mind to he excelled in, whether that be soldiering or academic achievement, those who he met along the way all remember him fondly. It was no surprise for me to learn only recently that there is a street named after him (Menzies Crescent) in his families home town of Prospect, South Australia. I have also learned during my research that one Chindit colleague (Peter Dorans) even named one of his sons after Duncan. So these examples should leave you in no doubt as to the kind of man we are honouring here in these few short paragraphs.

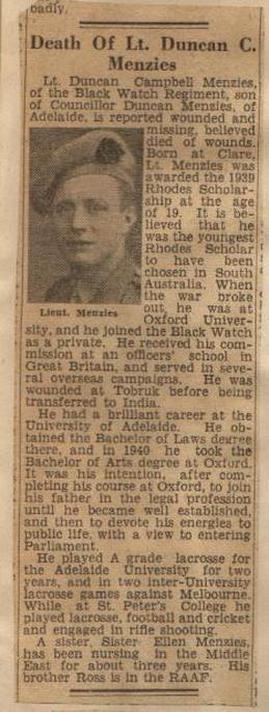

The newspaper cutting (left, courtesy of Bob Warn) gives a detailed account of the sort of person Duncan really was. Although on this website it is my intention to give the reader those small personal details that will show you the real nature of the men who served on Longcloth, I think in Duncan's case a fuller biography is deserved. I will leave you in the much more capable hands of Alasdair Sutherland and his biography of Duncan Campbell Menzies, which can be read here:

www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/68/a2639568.shtml

In Fergusson's book 'Beyond the Chindwin' there is a note describing the death of Duncan Campbell Menzies. I have paraphrased it here. To set the scene, column five had been severely short of food for some time and Duncan and another soldier Lance Corporal Charles Gilmartin (possibly Menzies's batman) had been part of a group sent into the village of Zibyugin to obtain supplies. The two men never returned to the column and it was not until after Fergusson had got back to India and met up with some of the senior Burma Rifle officers that Duncan's fate was learned.

"On April 4th, the day after Duncan had failed to return, a section of Burma Rifles entered the village of Zibyugin. A small number of Japanese were seen off and the village was checked. Jemadar Lader found Duncan and Gilmartin tied to a tree. Gilmartin was already dead, but Duncan was still just alive. Colonel Wheeler (Senior Burma Rifle officer in 1943) and Peter Buchanan tended to Duncan giving him some morphine to relieve his pain from a gunshot wound to the stomach. Menzies briefed Wheeler on what had happened to him and of column fives poor state of health."

"He then asked Wheeler if he would take his wristwatch and return it to his family in Australia if he had the chance. With that Duncan died. No sooner had Wheeler stepped away from this sad scene, he too was killed instantly by a stray Japanese bullet. It has always seemed to me (Fergusson) the saddest and strangest fate that Wheeler and Duncan, two of the finest men in the force, should both meet their end in this small and hitherto unknown village."

It is not really known what had happened to Duncan in the 24 or so hours he was held prisoner in the village of Zibyugin. We do know he had been shot and he would almost certainly have been interrogated by his captors, but perhaps even the Japanese had come to realise his great character and bravery in that short period. They had begun to prepare him for burial, including shaving his head, something only customary in the Japanese Army for the honourable and revered.

Pte. Charles Gilmartin's story can be found alphabetically listed on the Longcloth Roll Call pages by following the link here: Roll Call F-J

www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/68/a2639568.shtml

In Fergusson's book 'Beyond the Chindwin' there is a note describing the death of Duncan Campbell Menzies. I have paraphrased it here. To set the scene, column five had been severely short of food for some time and Duncan and another soldier Lance Corporal Charles Gilmartin (possibly Menzies's batman) had been part of a group sent into the village of Zibyugin to obtain supplies. The two men never returned to the column and it was not until after Fergusson had got back to India and met up with some of the senior Burma Rifle officers that Duncan's fate was learned.

"On April 4th, the day after Duncan had failed to return, a section of Burma Rifles entered the village of Zibyugin. A small number of Japanese were seen off and the village was checked. Jemadar Lader found Duncan and Gilmartin tied to a tree. Gilmartin was already dead, but Duncan was still just alive. Colonel Wheeler (Senior Burma Rifle officer in 1943) and Peter Buchanan tended to Duncan giving him some morphine to relieve his pain from a gunshot wound to the stomach. Menzies briefed Wheeler on what had happened to him and of column fives poor state of health."

"He then asked Wheeler if he would take his wristwatch and return it to his family in Australia if he had the chance. With that Duncan died. No sooner had Wheeler stepped away from this sad scene, he too was killed instantly by a stray Japanese bullet. It has always seemed to me (Fergusson) the saddest and strangest fate that Wheeler and Duncan, two of the finest men in the force, should both meet their end in this small and hitherto unknown village."

It is not really known what had happened to Duncan in the 24 or so hours he was held prisoner in the village of Zibyugin. We do know he had been shot and he would almost certainly have been interrogated by his captors, but perhaps even the Japanese had come to realise his great character and bravery in that short period. They had begun to prepare him for burial, including shaving his head, something only customary in the Japanese Army for the honourable and revered.

Pte. Charles Gilmartin's story can be found alphabetically listed on the Longcloth Roll Call pages by following the link here: Roll Call F-J

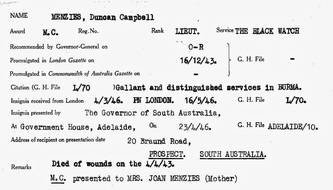

An example of a Military Cross.

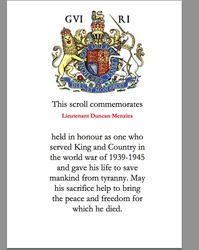

Bernard Fergusson was determined that Duncan would not be forgotten in regard to his supreme efforts for column five during Longcloth and pressed the powers that be to award him a posthumous Military Cross (see right). After some persuasion the Army council in India granted the award, the medal was eventually presented to Duncan's mother Joan, on 23rd April 1946 by the Governor of South Australia.

Here is a transcription of his MC citation, taken from the original recommendation certificate held at the National Archives, Kew, London.

Lieut. MENZIES was Adjutant of No. 5 Column. At the cutting of the railway at and south of BONCHAUNG on 6th March 1943, he was in charge of the main demolition at BONCHAUNG railway station for the first hour of the work, while his Column Commander was involved in a skirmish elsewhere. Owing to enemy activity, he had had to lead the Column by a difficult route across mountains, a journey accomplished in a very short space of time.

At HINTHA on 28th March 43, he remained for half an hour in an exposed position by himself, keeping the enemy off with grenades and calling back with accurate information about their movements with a fine disregard of danger.

Throughout the campaign he set a high example of efficiency, cheerfulness and devotion to duty. Of great physical powers of endurance his energy never flagged; and at the end of the most trying march he was tireless and possessed of extraordinary reserves of strength. He was easily the most skilful jungle navigator in the Column, which he would lead for hours without relief cutting a track as he went. Utterly fearless in action and an unbending disciplinarian who exacted his own high standards from everybody, he commanded the confidence and affection of every man in the column. He has since been killed in action on 04.04.1943.

Recommended By

Major B.E. Fergusson, D.S.O., The Black Watch

Column Commander

77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

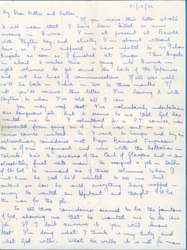

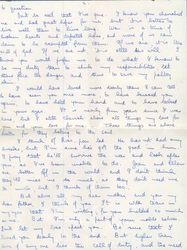

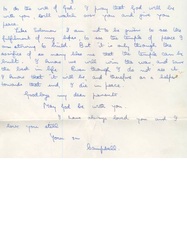

Duncan spent his last leave period before going into Burma with Phyllis Brookman, a long standing family friend, and it was to her that he entrusted delivery of his final letter home. In this letter dated 21/12/1942 he explains to his parents how he managed to end up as part of operation Longcloth, how he is very glad to be serving with Bernard Fergusson once more and how he believes the operation would be the beginning of the Allies eventual triumph over the enemy. In this very touching letter he says goodbye to each member of his family individually and tries hard to convince his parents that God is with him and will help him through whatever may confront him along the way. Here is how he ends the letter:

"I pray that God will be with you, will watch over you and give you peace. Like Soloman, I am not to be given to see the fulfillment of my hopes, to see the temple of peace I am striving to build. But it is only through the sacrifice of so many like me, that the temple can be built. I know we will win the war and save the best in life. Even though I do not see it, I know that it will be, and therefore as a helper towards that end, I die in peace.

Goodbye my dear parents. May God be with you. I have always loved you and love you still. Your son, Campbell."

It is clear to me that Menzies knew that the odds were fairly well stacked against him surviving and perhaps he had a sense that he would not return home from the jungles of Burma. It is to his credit that he made such a massive effort to console his family, although this was a difficult letter to write and to read, it would mean much more to the loved ones he left as time went by.

I need to thank several people, who over the last few years have helped trace this story and have provided me with so much information and knowledge. They are:

Fiona Speirs

Andrew Menzies

Geordie Fergusson

Bob Warn

John and Val Eastwood

Ian Grimwood

Andrea McKinnon-Matthews

Michael Whiteman

Win Hatherly

Robert Fisher

Phil Crawley

Sian Powell

all at the Prospect Local History Collection, especially Lianne Gould.

Update 28/06/2012

Since completing these pages I have been contacted by Campbell's niece Fiona Speirs and she has shared some more letters and information with me and a fellow researcher from the website WW2Talk, Geoff or Spidge as he is known online. Below is a link to the website where Geoff has uploaded some personal letters written by and to the Menzies family concerning the life and sad death of Duncan Campbell Menzies. It is amazingly kind of the family and especially Campbell's sister Jean (now in her nineties) to allow such personal documents to feature on this and the WW2Talk website.

Here is the link to the discussion page on WW2Talk in relation to Campbell's story:

www.ww2talk.com/index.php?threads/info-australian-allied-unit-lt-duncan-campbell-menzies-182309-black-watch-royal-highlanders-attd.34971/

I have also now included in full the letter Campbell wrote in late December 1942 and placed in the safe care of Phyllis Brookman, to be sent home to his parents only in the event of him not returning from Burma in 1943. Please click on a page to enlarge.

Here is a transcription of his MC citation, taken from the original recommendation certificate held at the National Archives, Kew, London.

Lieut. MENZIES was Adjutant of No. 5 Column. At the cutting of the railway at and south of BONCHAUNG on 6th March 1943, he was in charge of the main demolition at BONCHAUNG railway station for the first hour of the work, while his Column Commander was involved in a skirmish elsewhere. Owing to enemy activity, he had had to lead the Column by a difficult route across mountains, a journey accomplished in a very short space of time.

At HINTHA on 28th March 43, he remained for half an hour in an exposed position by himself, keeping the enemy off with grenades and calling back with accurate information about their movements with a fine disregard of danger.

Throughout the campaign he set a high example of efficiency, cheerfulness and devotion to duty. Of great physical powers of endurance his energy never flagged; and at the end of the most trying march he was tireless and possessed of extraordinary reserves of strength. He was easily the most skilful jungle navigator in the Column, which he would lead for hours without relief cutting a track as he went. Utterly fearless in action and an unbending disciplinarian who exacted his own high standards from everybody, he commanded the confidence and affection of every man in the column. He has since been killed in action on 04.04.1943.

Recommended By

Major B.E. Fergusson, D.S.O., The Black Watch

Column Commander

77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

Duncan spent his last leave period before going into Burma with Phyllis Brookman, a long standing family friend, and it was to her that he entrusted delivery of his final letter home. In this letter dated 21/12/1942 he explains to his parents how he managed to end up as part of operation Longcloth, how he is very glad to be serving with Bernard Fergusson once more and how he believes the operation would be the beginning of the Allies eventual triumph over the enemy. In this very touching letter he says goodbye to each member of his family individually and tries hard to convince his parents that God is with him and will help him through whatever may confront him along the way. Here is how he ends the letter:

"I pray that God will be with you, will watch over you and give you peace. Like Soloman, I am not to be given to see the fulfillment of my hopes, to see the temple of peace I am striving to build. But it is only through the sacrifice of so many like me, that the temple can be built. I know we will win the war and save the best in life. Even though I do not see it, I know that it will be, and therefore as a helper towards that end, I die in peace.

Goodbye my dear parents. May God be with you. I have always loved you and love you still. Your son, Campbell."

It is clear to me that Menzies knew that the odds were fairly well stacked against him surviving and perhaps he had a sense that he would not return home from the jungles of Burma. It is to his credit that he made such a massive effort to console his family, although this was a difficult letter to write and to read, it would mean much more to the loved ones he left as time went by.

I need to thank several people, who over the last few years have helped trace this story and have provided me with so much information and knowledge. They are:

Fiona Speirs

Andrew Menzies

Geordie Fergusson

Bob Warn

John and Val Eastwood

Ian Grimwood

Andrea McKinnon-Matthews

Michael Whiteman

Win Hatherly

Robert Fisher

Phil Crawley

Sian Powell

all at the Prospect Local History Collection, especially Lianne Gould.

Update 28/06/2012

Since completing these pages I have been contacted by Campbell's niece Fiona Speirs and she has shared some more letters and information with me and a fellow researcher from the website WW2Talk, Geoff or Spidge as he is known online. Below is a link to the website where Geoff has uploaded some personal letters written by and to the Menzies family concerning the life and sad death of Duncan Campbell Menzies. It is amazingly kind of the family and especially Campbell's sister Jean (now in her nineties) to allow such personal documents to feature on this and the WW2Talk website.

Here is the link to the discussion page on WW2Talk in relation to Campbell's story:

www.ww2talk.com/index.php?threads/info-australian-allied-unit-lt-duncan-campbell-menzies-182309-black-watch-royal-highlanders-attd.34971/

I have also now included in full the letter Campbell wrote in late December 1942 and placed in the safe care of Phyllis Brookman, to be sent home to his parents only in the event of him not returning from Burma in 1943. Please click on a page to enlarge.

Update 11/08/2012

I recently received an email from Win Hatherly of Melbourne, Australia. He had seen my post in the Burma Star magazine, Dekho, asking for photos and information about the Duncan Campbell Menzies Memorial. It has been extremely heart warming to have received so much help from so many families over in Australia and I thank them all once again.

Here is what Win had to tell me:

I saw an article in the Spring 2011 issue of Dekho that you were interested in the Menzies Memorial. My father, who recently passed away at the age of 99, was a member of the South Australia Branch of the Burma Star Association. As you may be aware, the SA Branch closed because of a lack of members. In the early 1990's my father, Herbert Charles (Peter) Hatherly was instrumental in having a Burma Star placed on the Menzies Memorial in Prospect.

Since that time Dad has always placed a wreath on the memorial at the dawn service on ANZAC Day each year, including this year. In recent years my wife and I have travelled to Adelaide from Melbourne to assist Dad in placing the wreath. As he recently passed away, we will undertake the task from now on. I have attached a photo (see below) of my Dad and I at the Menzies Memorial this ANZAC Day. Note that some low life has broken a point off the star. This is the second star to be adhered to the memorial as the first star (bronze) was stolen.

Herbert Charles Hatherly was a member of the RAF in WW2, Win went on to tell me that:

My father and his crew were attached to 45 Sqn. RAF and were stationed briefly in Magwe, Burma, from early March 1942. Soon after his arrival as a Wireless Air Gunner in Blenheim aircraft, the evacuation of Magwe commenced and 45 Sqn. ended up in Lashio in the north of Burma. Whilst in Lashio my father was amongst a group of volunteers given the task of bomb retrieval from a place called He Ho. A convoy of several trucks left Lashio for He Ho, some 400 miles away in the direction of Japanese lines.

At the time of their departure from Lashio, the convoy was unaware that He Ho had been captured by the Japanese. Fortunately, as it turned out, the truck my father was driving received a puncture, leaving he and friend, Bill Wilson, separated from the main convoy that had continued towards He Ho. Within several miles of the town a British doctor, who was from the local area, advised my father and Bill of the Japanese occupation, so they returned to Lashio. Dad was never sure of the fate of the main convoy, but was thankful of the warning received from the doctor. 45 Sqn. left Lashio for India in late April 1942.

I recently received an email from Win Hatherly of Melbourne, Australia. He had seen my post in the Burma Star magazine, Dekho, asking for photos and information about the Duncan Campbell Menzies Memorial. It has been extremely heart warming to have received so much help from so many families over in Australia and I thank them all once again.

Here is what Win had to tell me:

I saw an article in the Spring 2011 issue of Dekho that you were interested in the Menzies Memorial. My father, who recently passed away at the age of 99, was a member of the South Australia Branch of the Burma Star Association. As you may be aware, the SA Branch closed because of a lack of members. In the early 1990's my father, Herbert Charles (Peter) Hatherly was instrumental in having a Burma Star placed on the Menzies Memorial in Prospect.

Since that time Dad has always placed a wreath on the memorial at the dawn service on ANZAC Day each year, including this year. In recent years my wife and I have travelled to Adelaide from Melbourne to assist Dad in placing the wreath. As he recently passed away, we will undertake the task from now on. I have attached a photo (see below) of my Dad and I at the Menzies Memorial this ANZAC Day. Note that some low life has broken a point off the star. This is the second star to be adhered to the memorial as the first star (bronze) was stolen.

Herbert Charles Hatherly was a member of the RAF in WW2, Win went on to tell me that:

My father and his crew were attached to 45 Sqn. RAF and were stationed briefly in Magwe, Burma, from early March 1942. Soon after his arrival as a Wireless Air Gunner in Blenheim aircraft, the evacuation of Magwe commenced and 45 Sqn. ended up in Lashio in the north of Burma. Whilst in Lashio my father was amongst a group of volunteers given the task of bomb retrieval from a place called He Ho. A convoy of several trucks left Lashio for He Ho, some 400 miles away in the direction of Japanese lines.

At the time of their departure from Lashio, the convoy was unaware that He Ho had been captured by the Japanese. Fortunately, as it turned out, the truck my father was driving received a puncture, leaving he and friend, Bill Wilson, separated from the main convoy that had continued towards He Ho. Within several miles of the town a British doctor, who was from the local area, advised my father and Bill of the Japanese occupation, so they returned to Lashio. Dad was never sure of the fate of the main convoy, but was thankful of the warning received from the doctor. 45 Sqn. left Lashio for India in late April 1942.

Update 06/09/2012.

From Bernard Fergusson's book 'The Black Watch and the King's Enemies' comes the following information concerning Campbell's WW2 experiences before Operation Longcloth. Campbell had performed admirably at and done well indeed to survive the battalions involvement in the action in and around Tobruk during the second half of 1941.

After Tobruk the battalion went to Syria and prepared to face Rommel once more at Anatolia. This confrontation did not materialize and the unit found itself aboard the troopship Mauretania and bound for the Far East. On board the officers attempted to learn as much as they could about the conditions they might face in South East Asia. As the Mauretania passed the port of Aden the news that Rangoon had fallen to the Japanese changed all previous plans and the battalion was diverted to Bombay. After several weeks moving through various Indian towns the 2nd Black Watch found itself in Ranchi and soon to undertake training in the art of jungle warfare.

By October 1942 the battalion was stationed in and around the town of Contai. It was here on the 16th October that a cyclone hit the area and both B and C Companies of the unit were caught out and some men became stranded by the rapidly rising waters. The platoons of C company found themselves separated by the raging torrent that was once the local river. One commander decided to attempt to reach the relative safety of the sea wall, but all efforts were in vain. The battalion's diary describes these events thus:

"Second-Lieutenant Duncan Menzies who had been isolated on a small hillock, and who was a powerful swimmer, swam in at 1 pm, and in the course of the afternoon led two more attempts, both of which failed, to reach the sea wall.

17 October 0600 hours: A scene of desolation, no houses standing, tents covered by a foot of mud and slit, trucks emptied of their loads, ships swept a quarter of a mile inland, dead bodies and carcasses of cattle, fish, snakes and pi-dogs wherever the eye can reach. 0700 hours: Company commander swam the river to see how 13 platoon are, finds them hungry, thirsty and exhausted: they have been clinging to a strip of road which was the only ground not under water for 24 hours. A party of five under Sergeant Winter is still missing."

Thankfully Winter's party eventually turned up safe and sound. However, D Company were not so fortunate that day and lost over 15 men to the cyclone when a bridge they were on collapsed and was swept away. Campbell was commended by the King and several others by the Viceroy for their conduct during the ordeal. Shortly after the events of October 16th Campbell left the battalion and transferred to the 13th Kings, where he joined Bernard Fergusson and column 5 at Saugor. Just over a year later the 2nd Black Watch were also converted to a Chindit battalion, forming part of the 14th British Infantry Brigade under Brigadier Tom Brodie.

From Bernard Fergusson's book 'The Black Watch and the King's Enemies' comes the following information concerning Campbell's WW2 experiences before Operation Longcloth. Campbell had performed admirably at and done well indeed to survive the battalions involvement in the action in and around Tobruk during the second half of 1941.

After Tobruk the battalion went to Syria and prepared to face Rommel once more at Anatolia. This confrontation did not materialize and the unit found itself aboard the troopship Mauretania and bound for the Far East. On board the officers attempted to learn as much as they could about the conditions they might face in South East Asia. As the Mauretania passed the port of Aden the news that Rangoon had fallen to the Japanese changed all previous plans and the battalion was diverted to Bombay. After several weeks moving through various Indian towns the 2nd Black Watch found itself in Ranchi and soon to undertake training in the art of jungle warfare.

By October 1942 the battalion was stationed in and around the town of Contai. It was here on the 16th October that a cyclone hit the area and both B and C Companies of the unit were caught out and some men became stranded by the rapidly rising waters. The platoons of C company found themselves separated by the raging torrent that was once the local river. One commander decided to attempt to reach the relative safety of the sea wall, but all efforts were in vain. The battalion's diary describes these events thus:

"Second-Lieutenant Duncan Menzies who had been isolated on a small hillock, and who was a powerful swimmer, swam in at 1 pm, and in the course of the afternoon led two more attempts, both of which failed, to reach the sea wall.

17 October 0600 hours: A scene of desolation, no houses standing, tents covered by a foot of mud and slit, trucks emptied of their loads, ships swept a quarter of a mile inland, dead bodies and carcasses of cattle, fish, snakes and pi-dogs wherever the eye can reach. 0700 hours: Company commander swam the river to see how 13 platoon are, finds them hungry, thirsty and exhausted: they have been clinging to a strip of road which was the only ground not under water for 24 hours. A party of five under Sergeant Winter is still missing."

Thankfully Winter's party eventually turned up safe and sound. However, D Company were not so fortunate that day and lost over 15 men to the cyclone when a bridge they were on collapsed and was swept away. Campbell was commended by the King and several others by the Viceroy for their conduct during the ordeal. Shortly after the events of October 16th Campbell left the battalion and transferred to the 13th Kings, where he joined Bernard Fergusson and column 5 at Saugor. Just over a year later the 2nd Black Watch were also converted to a Chindit battalion, forming part of the 14th British Infantry Brigade under Brigadier Tom Brodie.

Below is a photo gallery in regards to Campbell's life, his war and his memorials. He was undoubtedly a very special man. The image of Campbell's WW2 medal entitlement was a donation to St Peter's College S.A. archives, the original source of this image and location of the medals are unknown.

Update 09/02/2014

Following on from an enquiry by journalist Sian Powell, please see below her article in reference to an expedition back into Burma by a relative of Duncan Campbell Menzies. Hugh Menzies travelled to Burma in order to seek out the village of Zibyugin and discover new information about the last resting place of his uncle.

Following on from an enquiry by journalist Sian Powell, please see below her article in reference to an expedition back into Burma by a relative of Duncan Campbell Menzies. Hugh Menzies travelled to Burma in order to seek out the village of Zibyugin and discover new information about the last resting place of his uncle.

| in_the_footsteps_of_a_hero_the_advertiser_31_jan_2014_copy.pdf | |

| File Size: | 208 kb |

| File Type: | |

Update 28/04/2014.

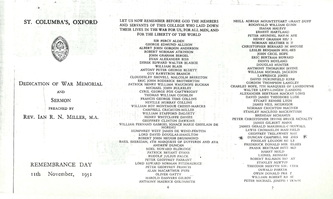

Whilst checking through my files I discovered two more photographs of Campbell Menzies and his time before WW2. Both images are in relation to his time at University and his selection as a Rhodes Scholar in 1939 and come from articles published by a local newspaper from that time. The first image shows Campbell receiving the congratulations of his friends and piers on the announcement of his Rhodes Scholarship, the second features Campbell in his University gown and mortar board at the University Commemoration Day in December 1938.

Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Whilst checking through my files I discovered two more photographs of Campbell Menzies and his time before WW2. Both images are in relation to his time at University and his selection as a Rhodes Scholar in 1939 and come from articles published by a local newspaper from that time. The first image shows Campbell receiving the congratulations of his friends and piers on the announcement of his Rhodes Scholarship, the second features Campbell in his University gown and mortar board at the University Commemoration Day in December 1938.

Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 31/03/2017.

An article from the Scotsman Newspaper dated 22nd January 1944:

Lieut. Duncan Menzies, Black Watch

Lt. Duncan Campbell Menzies, Black Watch, who has been posthumously awarded the Military Cross in recognition of gallant and distinguished service in Burma and on the Eastern Frontier of India, was one of the few Australians with the heroic Wingate Expedition (1943) which for three months, harassed the Japanese and destroyed their communications in Burma.

He died in a Burmese village after having been captured by the Japanese, who mortally wounded him just before they were driven out of the place by a party of his comrades from the Wingate force. Lt. Menzies, who came from Prospect, South Australia, was at Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar when the war began, and enlisted in the Black Watch. He was commended for bravery in the floods in India during 1942. An account of his death, written by Major Bernard Fergusson, was quoted in A Scotsman's Log, in our issue of August 25th last, having been taken from Blackwood's Magazine.

An article from the Scotsman Newspaper dated 22nd January 1944:

Lieut. Duncan Menzies, Black Watch

Lt. Duncan Campbell Menzies, Black Watch, who has been posthumously awarded the Military Cross in recognition of gallant and distinguished service in Burma and on the Eastern Frontier of India, was one of the few Australians with the heroic Wingate Expedition (1943) which for three months, harassed the Japanese and destroyed their communications in Burma.

He died in a Burmese village after having been captured by the Japanese, who mortally wounded him just before they were driven out of the place by a party of his comrades from the Wingate force. Lt. Menzies, who came from Prospect, South Australia, was at Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar when the war began, and enlisted in the Black Watch. He was commended for bravery in the floods in India during 1942. An account of his death, written by Major Bernard Fergusson, was quoted in A Scotsman's Log, in our issue of August 25th last, having been taken from Blackwood's Magazine.

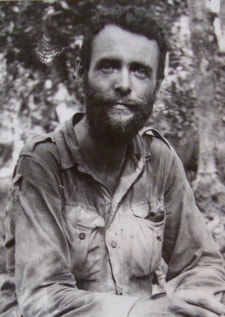

Major Bernard Fergusson, April 1943.

Major Bernard Fergusson, April 1943.

Update 02/10/2019.

The following update to this story was prompted by an email I received from Andrew Menzies, a great-nephew of Duncan Campbell Menzies. Andrew's email thanked me for my efforts in bringing Duncan's story to a wider audience and to inform me that the family still had possession of his medals, both the Military Cross and WW2 service medals. I replied to Andrew in mid-September and hope to hear from him again in the future.

Transcribed below is a letter sent to Duncan's father in July 1943, from Bernard Fergusson, No. 5 Column's commanding officer on Operation Longcloth:

Dear Mr. Menzies,

The announcement about Duncan will have been made by now and I hasten to write to you all that I can. I have never had a sadder task. First, I must break it to you that he is undoubtedly dead, and although he did suffer it was only for inside an hour at most. The circumstances were as follows:

On the 3rd April, my party of 9 officers and 70 men, which had been without food for three days, reached unexpectedly a small village called Zibyugin, not marked on any maps and about 50 miles south, south-west of Bhamo. We entered it and were told that 300 Japs had been in the village the previous evening and were expected back to collect supplies of rice which they had ordered. The villagers gave us some of the rice and we were waiting for more when the Japs came back.

We were in no physical state to fight and there was reason to hope that they did not know of our presence in the area at all, and so I withdrew. We still needed more food and a guide and so I resolved to wait and make another attempt at the the village later. This was approximately 7 am. At 1pm I sent Duncan with a small patrol to see if there were still signs of the Japs near the village. He said that if he got into any trouble he would fire his rifle. At 2pm we were shocked to hear five shots in quick succession. At 5pm two of the patrol returned and described how they had been spotted near the outskirts of the village. Duncan and Lance Corporal Gilmartin had sent the other two back and waited a while to be sure they were not followed. I waited for them until 5am the next morning and then sadly marched away.

After reaching India two months later, I met Peter Buchanan, Adjutant of the Burma Rifles on the operation. He told me how on the following day his Colonel, (L.G. Wheeler) and his party of 100 Riflemen came across the same village which was lightly held by the Japanese. Wheeler's men captured the village and here they found Duncan dressed in Japanese uniform with his beard and head shaved. He was lying on the ground grievously wounded and by his side lay the dead Lance Corporal. Duncan explained what had happened to Wheeler even though he was now in great pain. The Japs had taken him prisoner and had treated him well; although why they had dressed him in Jap uniform he could not make out. They had not shot him until the Burma Rifles attack came in. He then informed Wheeler that the Japs had left a small section of men to guard him and the village while the main party of Japs set off in pursuit of me and the remnants of my column.

Colonel Wheeler then gave Duncan some morphia and he was just falling asleep when Wheeler himself was shot through the head by a Japanese sniper and was killed instantly. Peter Buchanan told me that Duncan could not have survived many minutes and he had enough morphia to keep him asleep until everything was over. Before he fell asleep, Duncan had given Wheeler his watch to send back home to you. Peter then took it off Wheeler when he was killed and brought it out. I would have sent it by the bearer of this letter (M.I. Standish), but it had already been sent back to 2nd Echelon for forwarding to you with any other personal effects.

Yours, Major Bernard Fergusson (DSO), The Black Watch, GHQ New Delhi, India.

The following update to this story was prompted by an email I received from Andrew Menzies, a great-nephew of Duncan Campbell Menzies. Andrew's email thanked me for my efforts in bringing Duncan's story to a wider audience and to inform me that the family still had possession of his medals, both the Military Cross and WW2 service medals. I replied to Andrew in mid-September and hope to hear from him again in the future.

Transcribed below is a letter sent to Duncan's father in July 1943, from Bernard Fergusson, No. 5 Column's commanding officer on Operation Longcloth:

Dear Mr. Menzies,

The announcement about Duncan will have been made by now and I hasten to write to you all that I can. I have never had a sadder task. First, I must break it to you that he is undoubtedly dead, and although he did suffer it was only for inside an hour at most. The circumstances were as follows:

On the 3rd April, my party of 9 officers and 70 men, which had been without food for three days, reached unexpectedly a small village called Zibyugin, not marked on any maps and about 50 miles south, south-west of Bhamo. We entered it and were told that 300 Japs had been in the village the previous evening and were expected back to collect supplies of rice which they had ordered. The villagers gave us some of the rice and we were waiting for more when the Japs came back.

We were in no physical state to fight and there was reason to hope that they did not know of our presence in the area at all, and so I withdrew. We still needed more food and a guide and so I resolved to wait and make another attempt at the the village later. This was approximately 7 am. At 1pm I sent Duncan with a small patrol to see if there were still signs of the Japs near the village. He said that if he got into any trouble he would fire his rifle. At 2pm we were shocked to hear five shots in quick succession. At 5pm two of the patrol returned and described how they had been spotted near the outskirts of the village. Duncan and Lance Corporal Gilmartin had sent the other two back and waited a while to be sure they were not followed. I waited for them until 5am the next morning and then sadly marched away.

After reaching India two months later, I met Peter Buchanan, Adjutant of the Burma Rifles on the operation. He told me how on the following day his Colonel, (L.G. Wheeler) and his party of 100 Riflemen came across the same village which was lightly held by the Japanese. Wheeler's men captured the village and here they found Duncan dressed in Japanese uniform with his beard and head shaved. He was lying on the ground grievously wounded and by his side lay the dead Lance Corporal. Duncan explained what had happened to Wheeler even though he was now in great pain. The Japs had taken him prisoner and had treated him well; although why they had dressed him in Jap uniform he could not make out. They had not shot him until the Burma Rifles attack came in. He then informed Wheeler that the Japs had left a small section of men to guard him and the village while the main party of Japs set off in pursuit of me and the remnants of my column.

Colonel Wheeler then gave Duncan some morphia and he was just falling asleep when Wheeler himself was shot through the head by a Japanese sniper and was killed instantly. Peter Buchanan told me that Duncan could not have survived many minutes and he had enough morphia to keep him asleep until everything was over. Before he fell asleep, Duncan had given Wheeler his watch to send back home to you. Peter then took it off Wheeler when he was killed and brought it out. I would have sent it by the bearer of this letter (M.I. Standish), but it had already been sent back to 2nd Echelon for forwarding to you with any other personal effects.

Yours, Major Bernard Fergusson (DSO), The Black Watch, GHQ New Delhi, India.

Cap badge of the Black Watch Regiment.

Cap badge of the Black Watch Regiment.

Bernard Fergusson remembered his beloved comrade many times in his post-war writings, but perhaps the most poignant of these comes in the latter pages of Beyond the Chindwin:

I had lost many friends already in the war, but Duncan was the first to fall so near to me and the only one to go to his death at my instance. The lucky meeting at Saugor had led him to his death at Zibyugin, and I felt the responsibility acutely, far more than if, for instance, he had been killed with our own battalion of the (Black Watch) regiment.

We had learned so much of each other's homes and families, that I felt an almost criminal responsibility towards his. Other members of the expedition would have been on it anyhow, but the presence of him and of Peter Dorans only was directly due to me.

His was far more than a family loss, for he had a brilliant future before him. His entry into Australian politics was certain and his career both at Oxford and at home in Adelaide had already been remarkable. He combined in his character all that was best in his Australian upbringing and his pure Highland descent.

He had the physique, the confidence, the matter-or-factness of the Australian and the vision, the gentleness, the inspiration of the Highlander. All the way back to India, I seemed to see his broad shoulders, his powerful arm slashing at the jungle, his bush hat tilted back on his head and at halts to hear his talk, the infectious laugh which wrinkled his face and the absurd bamboo pipe which he had made with his Kukri. And in moments of stress, I seemed almost aware of his sage counsel.

I had lost many friends already in the war, but Duncan was the first to fall so near to me and the only one to go to his death at my instance. The lucky meeting at Saugor had led him to his death at Zibyugin, and I felt the responsibility acutely, far more than if, for instance, he had been killed with our own battalion of the (Black Watch) regiment.

We had learned so much of each other's homes and families, that I felt an almost criminal responsibility towards his. Other members of the expedition would have been on it anyhow, but the presence of him and of Peter Dorans only was directly due to me.

His was far more than a family loss, for he had a brilliant future before him. His entry into Australian politics was certain and his career both at Oxford and at home in Adelaide had already been remarkable. He combined in his character all that was best in his Australian upbringing and his pure Highland descent.

He had the physique, the confidence, the matter-or-factness of the Australian and the vision, the gentleness, the inspiration of the Highlander. All the way back to India, I seemed to see his broad shoulders, his powerful arm slashing at the jungle, his bush hat tilted back on his head and at halts to hear his talk, the infectious laugh which wrinkled his face and the absurd bamboo pipe which he had made with his Kukri. And in moments of stress, I seemed almost aware of his sage counsel.

More brave for this, that he hath much love.

Copyright © Steve Fogden 2011/2014.