The Longcloth Roll Call

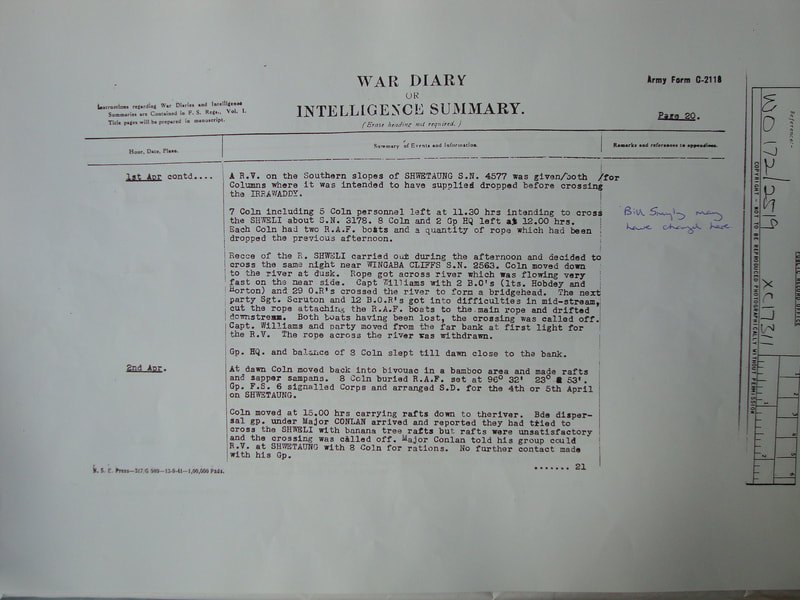

Surname F-J

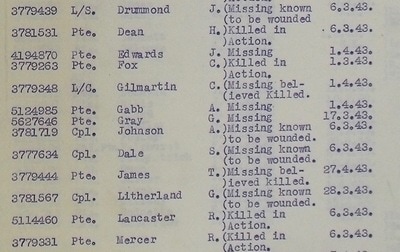

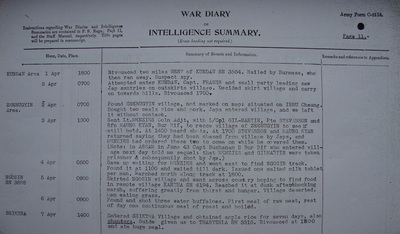

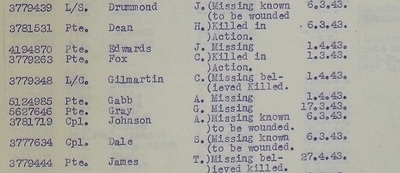

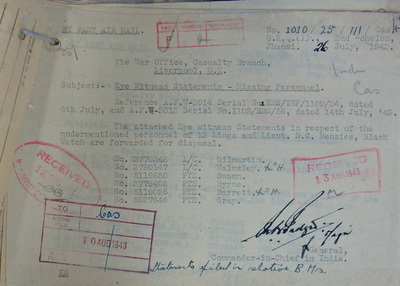

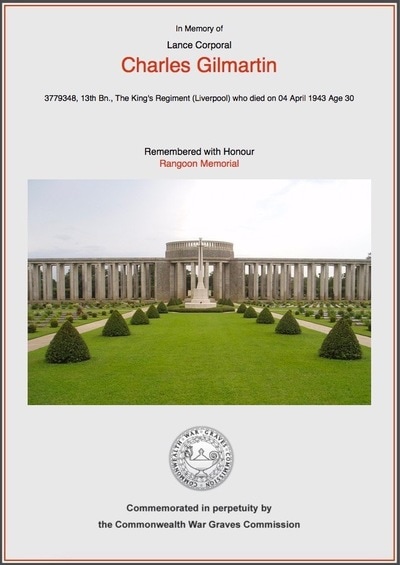

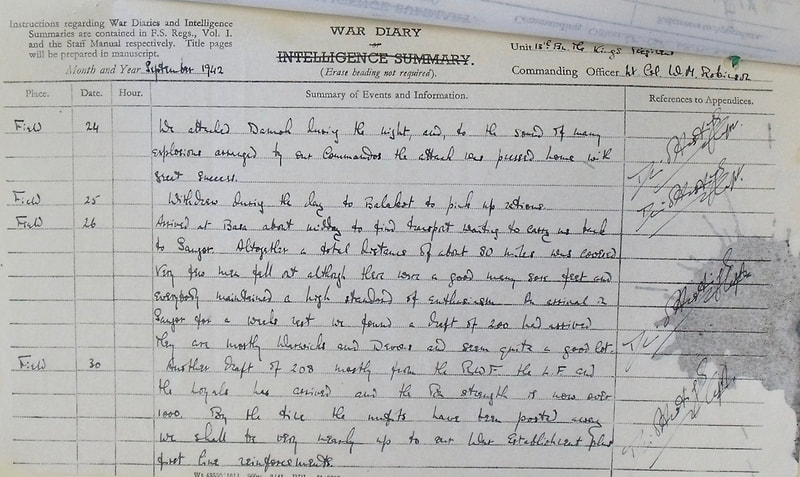

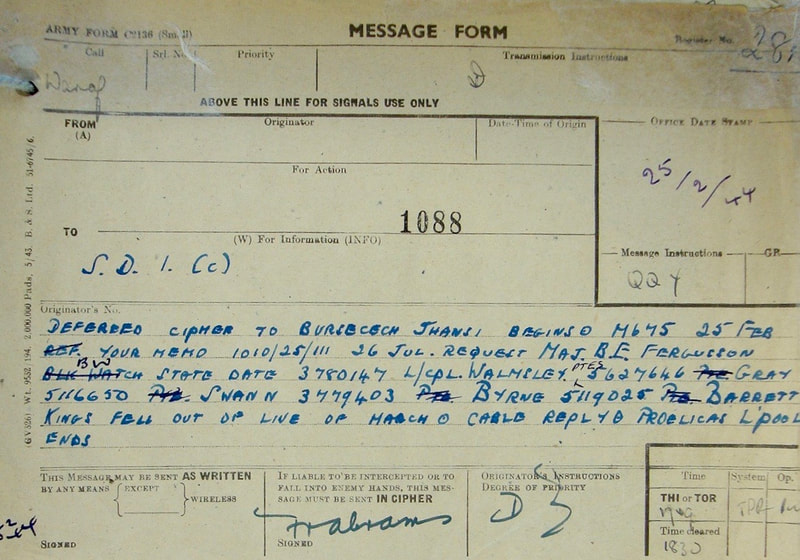

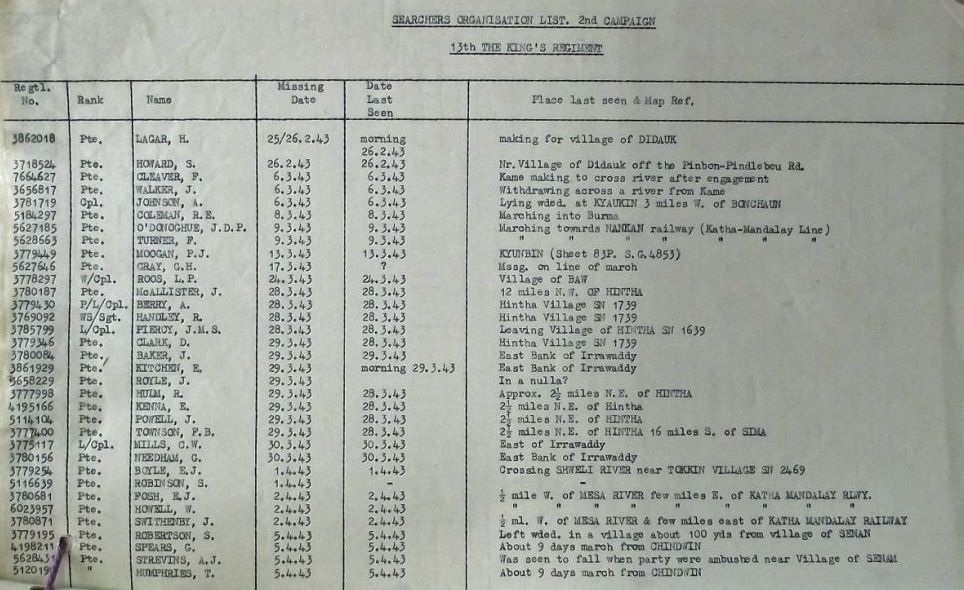

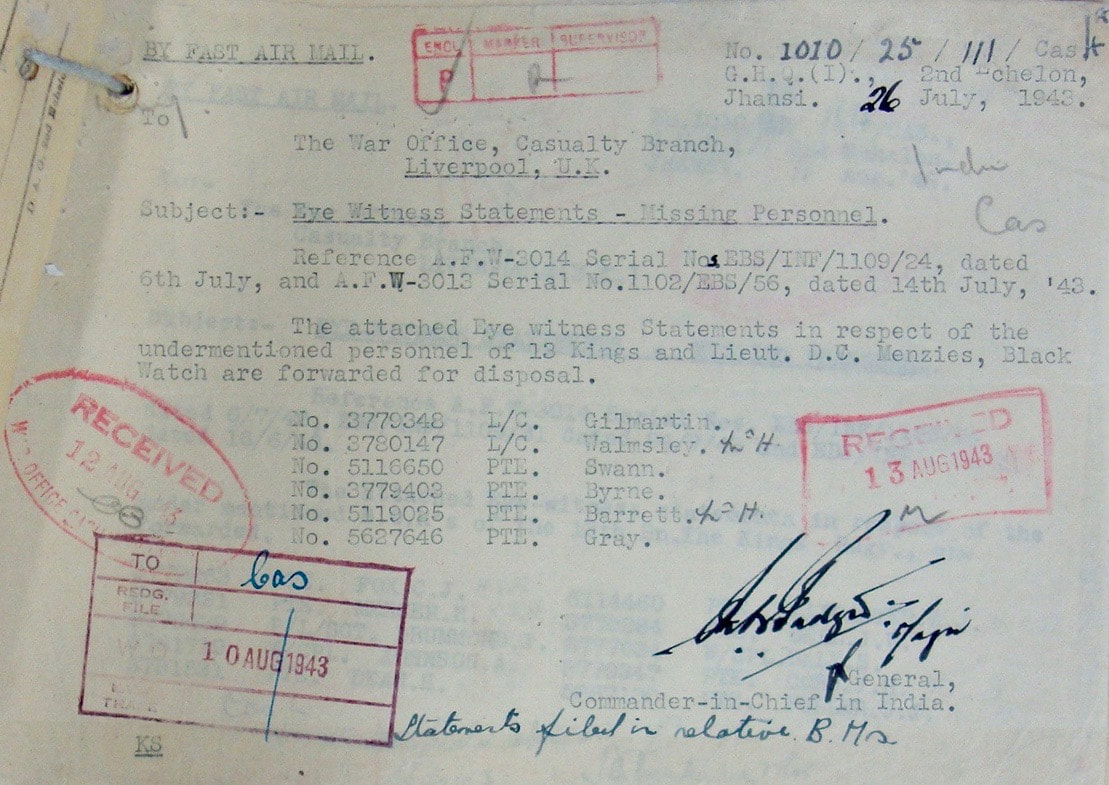

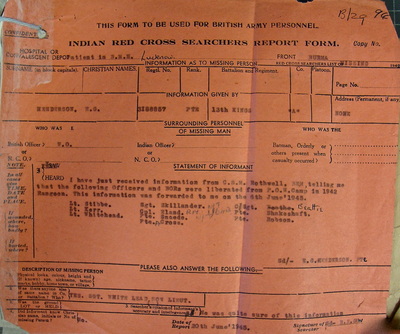

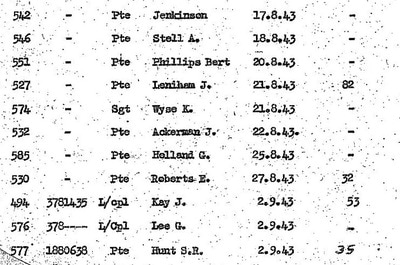

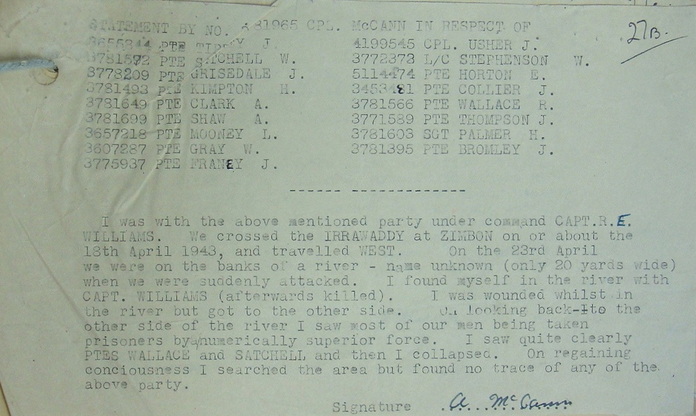

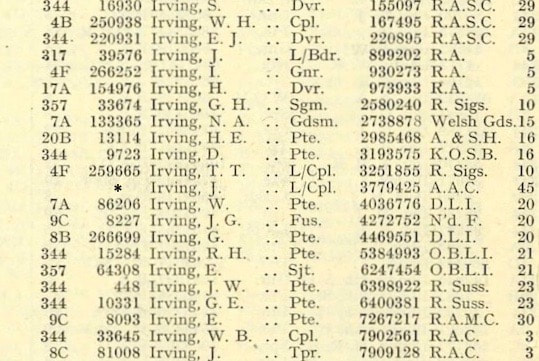

This section is an alphabetical roll of the men from Operation Longcloth. It takes its inspiration from other such formats available on the Internet, websites such as Special Forces Roll of Honour and of course the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC). The information shown comes from various different documents related to the first Chindit Operation in 1943. Apart from more obvious data, such as the serviceman's rank, number and regimental unit, other detail has been taken from associated war diaries, missing in action files and casualty witness statements. The vast majority of this type of information has been located at the National Archives and the relevant file references can be found in the section Sources and Knowledge on this website.

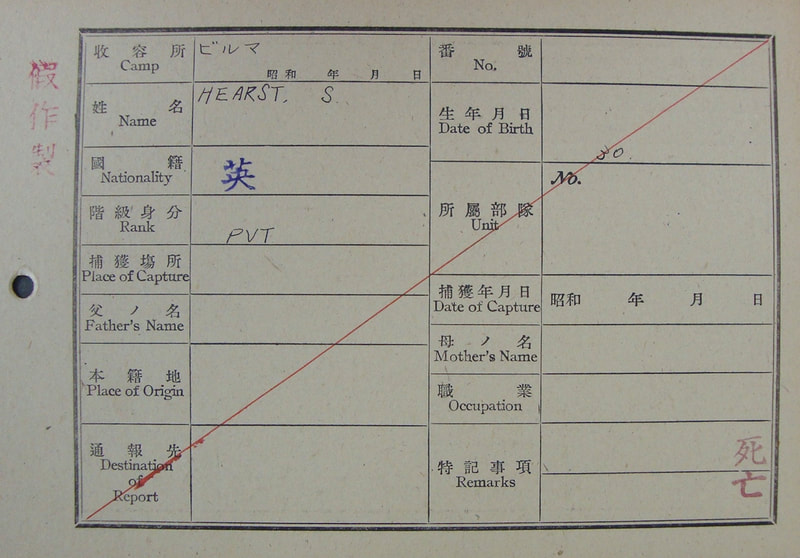

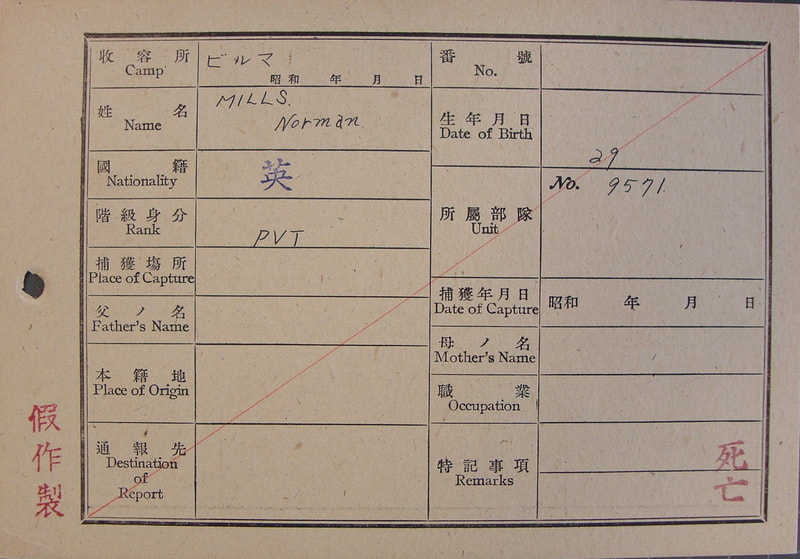

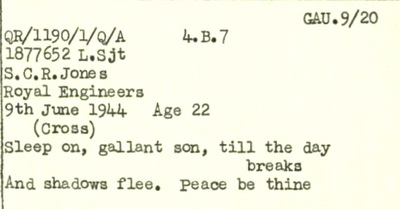

Sometimes, if the man in question became a prisoner of war more detail can be displayed showing his time whilst in Japanese hands. Other avenues for additional information are: books, personal diaries, veteran audio accounts and subsequent family input via letter, email and phone call.

The idea behind this page, is to include as many Longcloth participants as possible, even if there is only a small amount of information about their contribution to hand. Please click on any of the images to hopefully bring them forward on the page.

All information contained on this page is Copyright © Steve Fogden April 2014.

Sometimes, if the man in question became a prisoner of war more detail can be displayed showing his time whilst in Japanese hands. Other avenues for additional information are: books, personal diaries, veteran audio accounts and subsequent family input via letter, email and phone call.

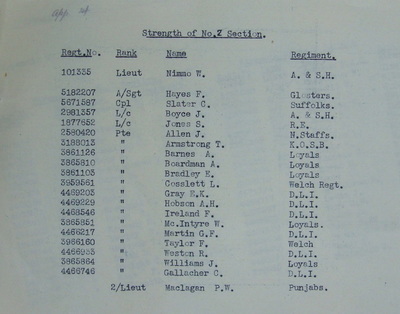

The idea behind this page, is to include as many Longcloth participants as possible, even if there is only a small amount of information about their contribution to hand. Please click on any of the images to hopefully bring them forward on the page.

All information contained on this page is Copyright © Steve Fogden April 2014.

Cap badge of the King's Regiment.

Cap badge of the King's Regiment.

FAIRFIELD, W.J.

Rank: Private

Service No: 3778233

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 1st Bn.

Chindit Column: 81 or 82 Operation Thursday 1944.

Other details:

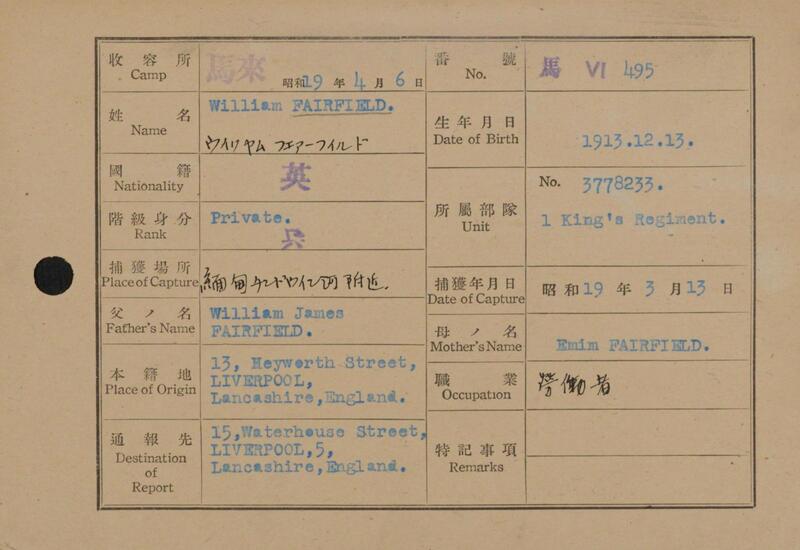

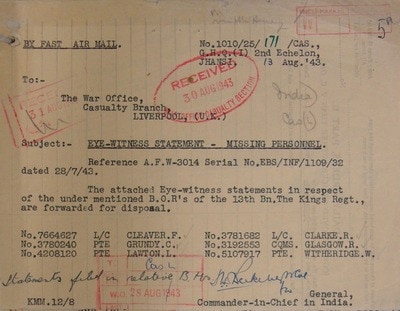

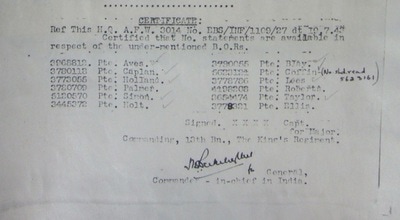

William James Fairfield was born on the 13th December 1913 and was the son of William and Emim Fairfield from Liverpool in Lancashire. He later married his wife Dorothy and together they had three children. From records on line, we know that Dorothy passed away in 1985 and William, still living in Liverpool at the time died in 1991. Due to his inclusion as a contributor to the missing files (WO361/442) for the 13th King's on Operation Longcloth, I at first believed that William had taken part on the first Wingate expedition in 1943. However, this has turned out to be incorrect and I now know that he took part in the second Chindit expedition in 1944, serving with the 1st Battalion of the King's Regiment.

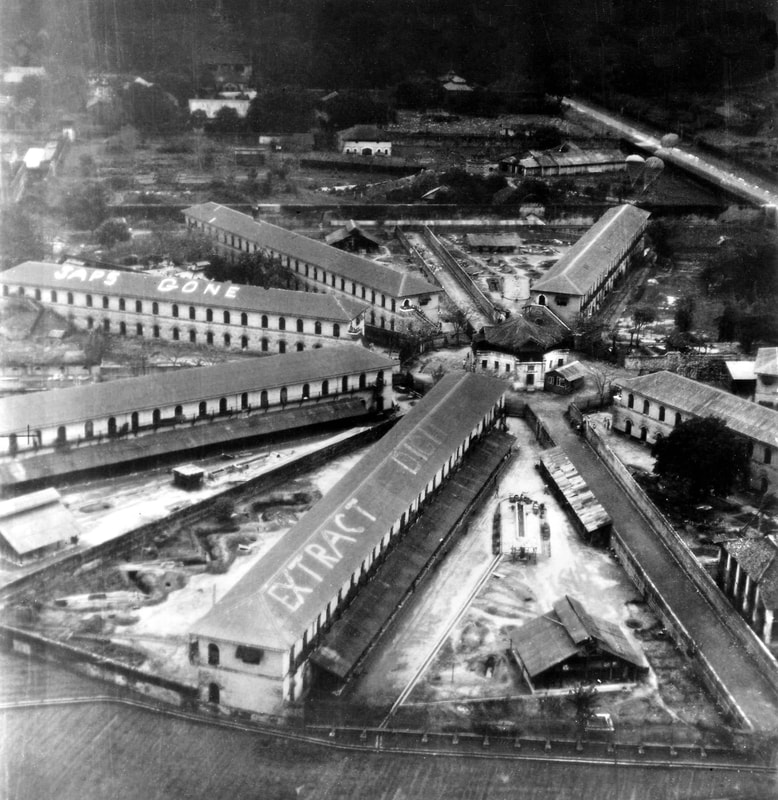

William flew in to Burma as part of the glider assault formation on the 5th March 1944, but his glider (No. 19B) did not reach the Broadway landing ground that night and crashed landed in the jungle. He was eventually taken prisoner on the 13th March. He survived his time as a POW, and after just over a year in Rangoon Jail was liberated in early May 1945. It was probably for his knowledge of other Chindit soldiers held at Rangoon, that William was asked to supply witness statements to the Army Investigation Bureau after the war.

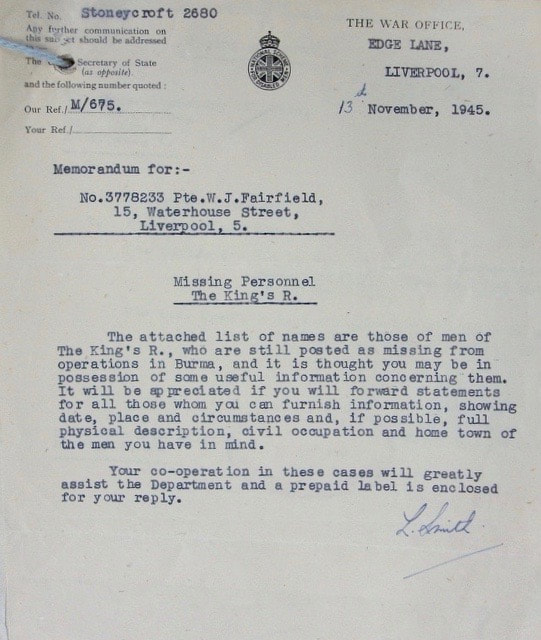

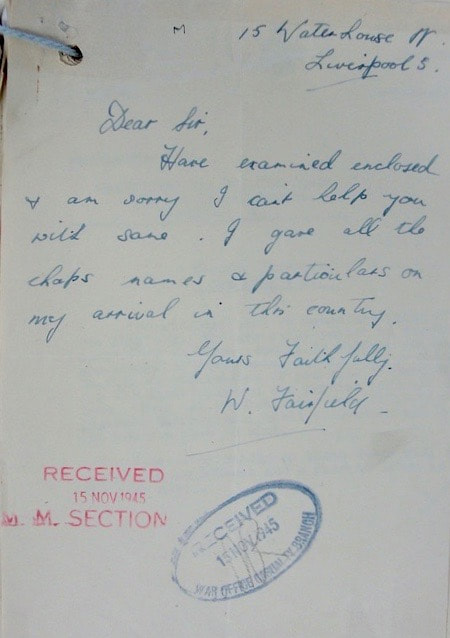

On the 13th November 1945, William, was officially asked by the Army Casualty Investigation Bureau to assist them as part of their ongoing enquiries into the missing and lost from the first Wingate expedition. Sadly, he was unable to help them in this matter, although on his immediate return to the United Kingdom from India he had already given some information to the bureau in regards to the men who shared his flight in Glider 19B on the 5th March 1944.

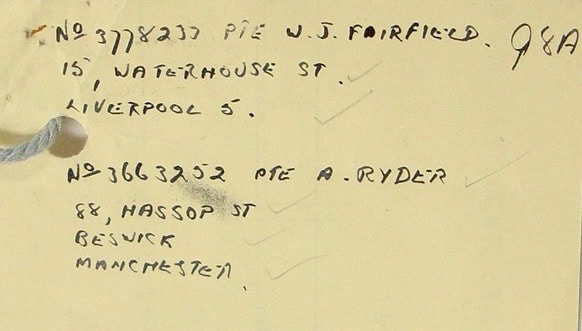

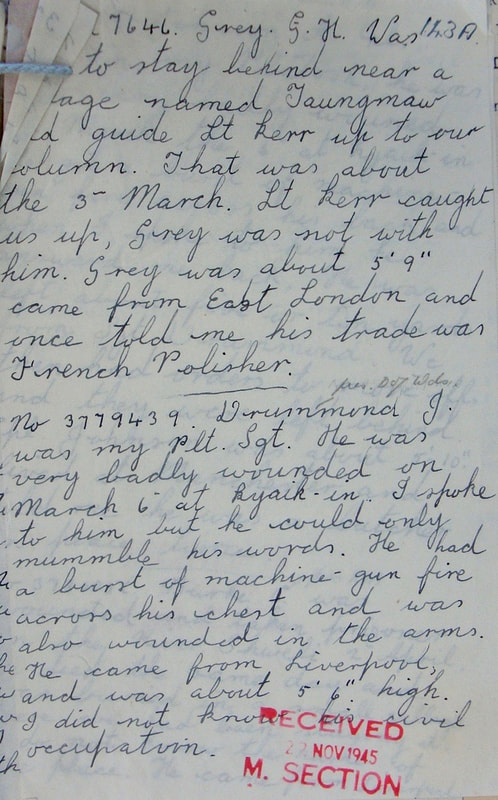

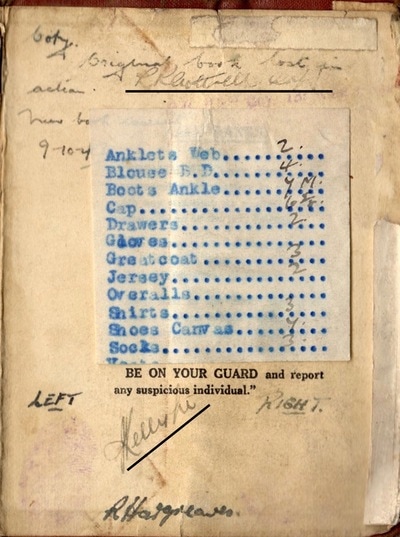

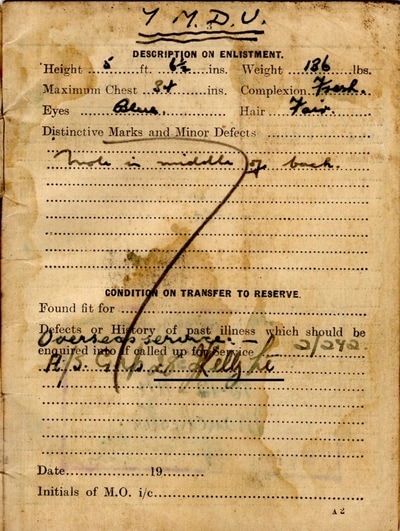

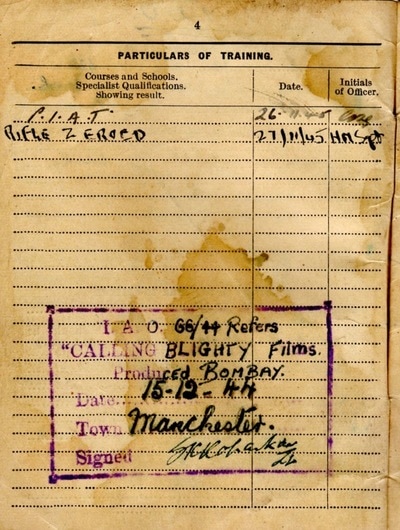

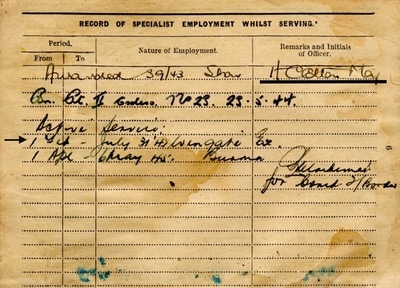

Seen below are some images in relation to this short narrative, including Pte. Fairfield's home address and his letter of reply to the War Office enquiry. Also shown is a narrative of what happened on the night of the 5th March as recalled by fellow 1st King's soldier, Arthur House and a copy of William's POW index card. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Rank: Private

Service No: 3778233

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 1st Bn.

Chindit Column: 81 or 82 Operation Thursday 1944.

Other details:

William James Fairfield was born on the 13th December 1913 and was the son of William and Emim Fairfield from Liverpool in Lancashire. He later married his wife Dorothy and together they had three children. From records on line, we know that Dorothy passed away in 1985 and William, still living in Liverpool at the time died in 1991. Due to his inclusion as a contributor to the missing files (WO361/442) for the 13th King's on Operation Longcloth, I at first believed that William had taken part on the first Wingate expedition in 1943. However, this has turned out to be incorrect and I now know that he took part in the second Chindit expedition in 1944, serving with the 1st Battalion of the King's Regiment.

William flew in to Burma as part of the glider assault formation on the 5th March 1944, but his glider (No. 19B) did not reach the Broadway landing ground that night and crashed landed in the jungle. He was eventually taken prisoner on the 13th March. He survived his time as a POW, and after just over a year in Rangoon Jail was liberated in early May 1945. It was probably for his knowledge of other Chindit soldiers held at Rangoon, that William was asked to supply witness statements to the Army Investigation Bureau after the war.

On the 13th November 1945, William, was officially asked by the Army Casualty Investigation Bureau to assist them as part of their ongoing enquiries into the missing and lost from the first Wingate expedition. Sadly, he was unable to help them in this matter, although on his immediate return to the United Kingdom from India he had already given some information to the bureau in regards to the men who shared his flight in Glider 19B on the 5th March 1944.

Seen below are some images in relation to this short narrative, including Pte. Fairfield's home address and his letter of reply to the War Office enquiry. Also shown is a narrative of what happened on the night of the 5th March as recalled by fellow 1st King's soldier, Arthur House and a copy of William's POW index card. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Cap badge of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles.

Cap badge of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles.

FALLOW, LT.

Rank: Lieutenant

Service No: Not known

Regiment/Service: 3rd Battalion, the 2nd Gurkha Regiment.

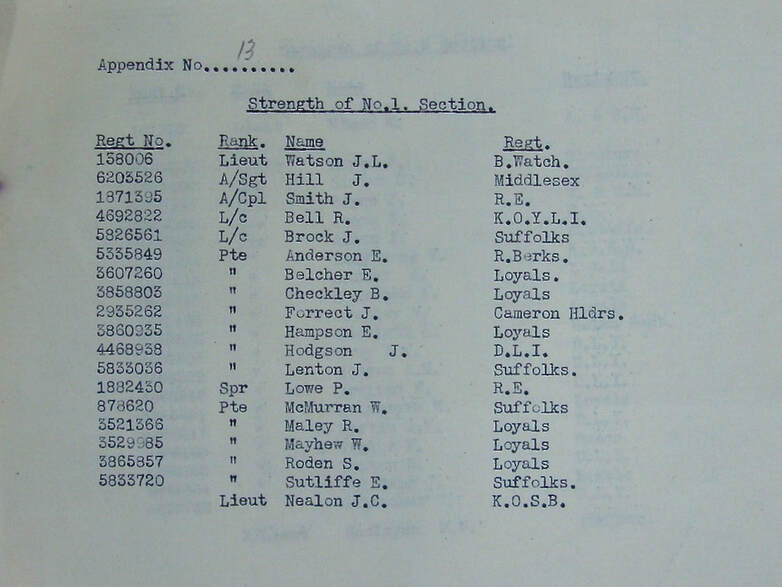

Chindit Column: 1

Other details:

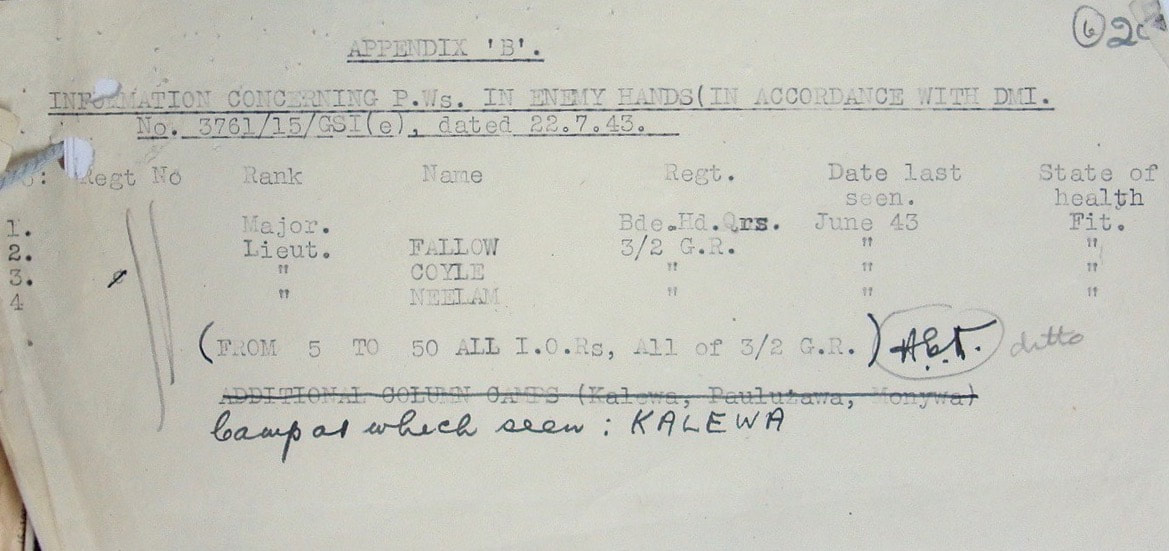

Lt. Fallow is mentioned in the missing in action files for the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade in 1943. However, no one of that name has ever been reported as a member of the first Chindit expedition and I wonder if this soldier's name has been incorrectly spelled or mispronounced by a Gurkha Riflemen upon interrogation after the operation was concluded?

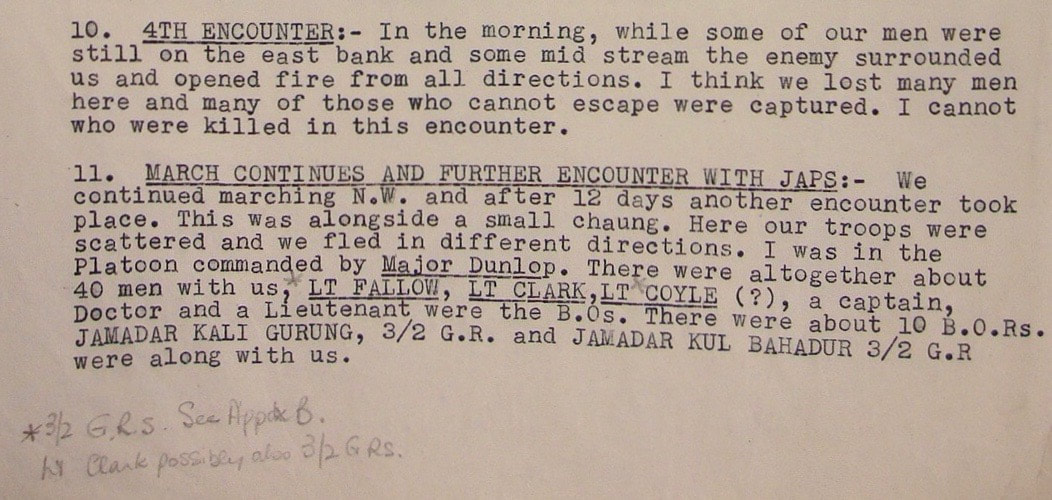

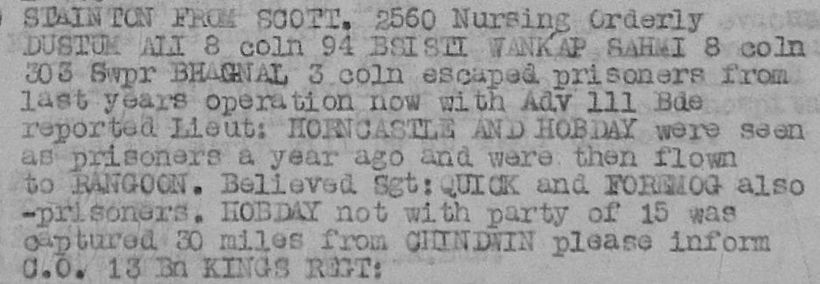

Fallow is attributed to No. 1 Column on Operation Longcloth, commanded by Major George Dunlop MC, formerly of the Black Watch Regiment. He is listed, alongside another mysterious and unaccounted for officer, as part of a witness statement given by the Gurkha Rifleman 27039 Aita Sing Gurung.

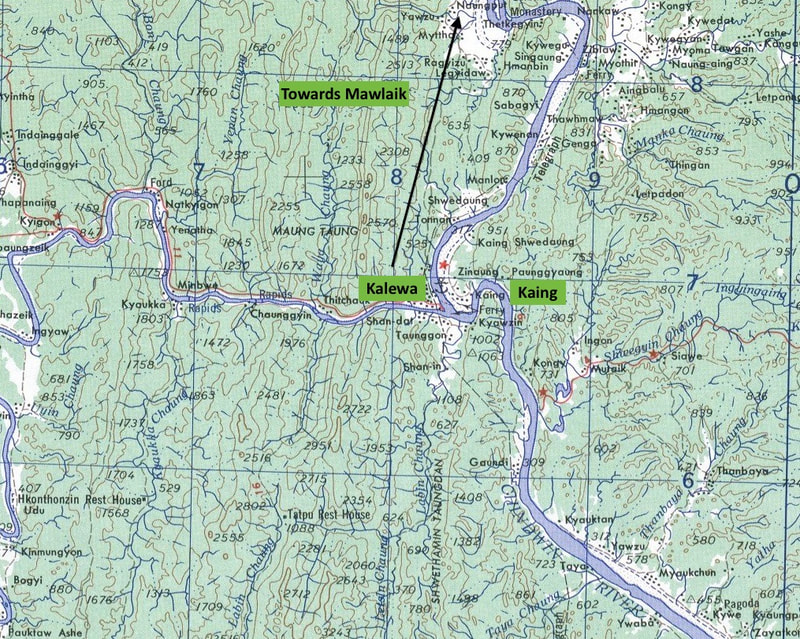

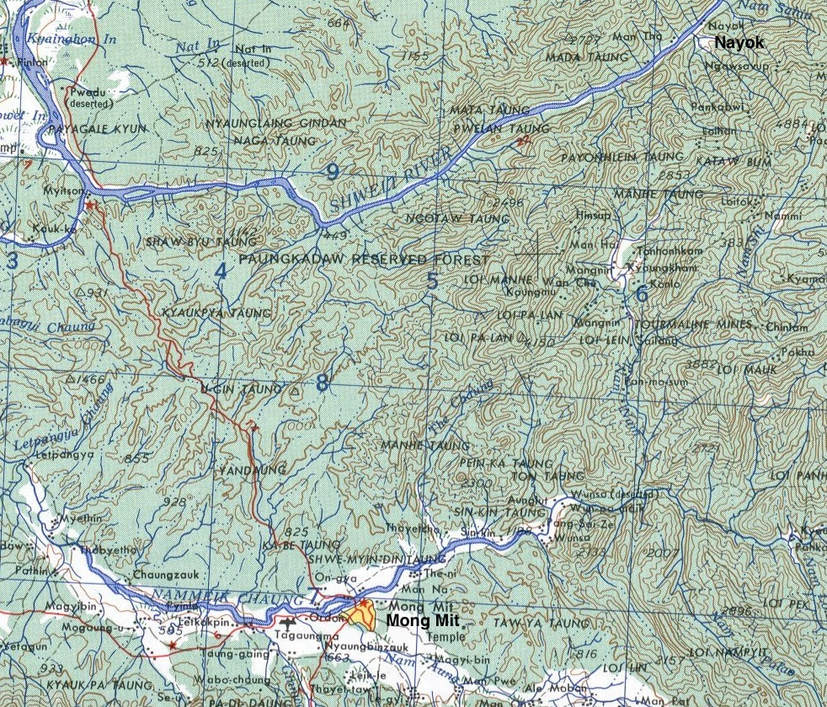

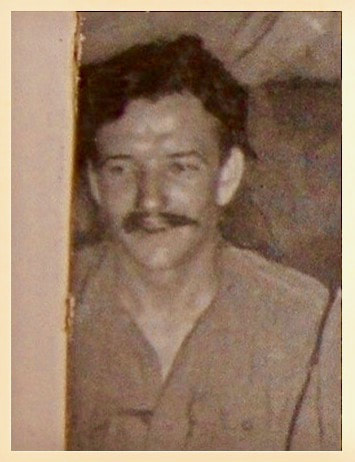

This Gurkha remembers these two officers as being part of a small dispersal party who had marched from the Irrawaddy in the company of Major Dunlop and who had been disturbed by a Japanese patrol close to the Chindwin River in early May 1943. The report goes on to describe how Lts. Fallow and Coyle (?) were subsequently taken prisoner after this incident and were held initially in a POW camp at Kalewa, before ending up at Rangoon Jail. No officers by these names have ever been recorded as being prisoners of war in Rangoon or at any of the other camps used by the Japanese in relation to Chindit detainees.

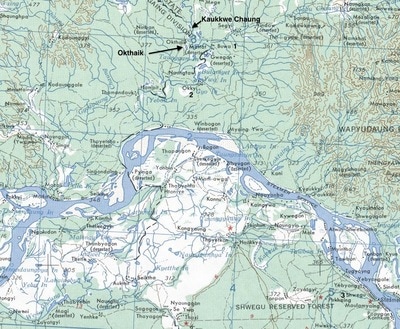

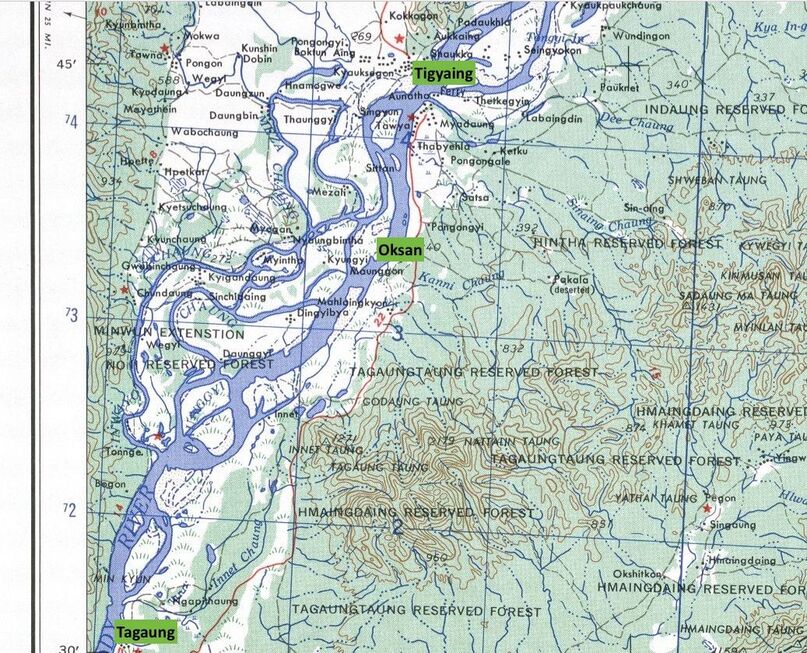

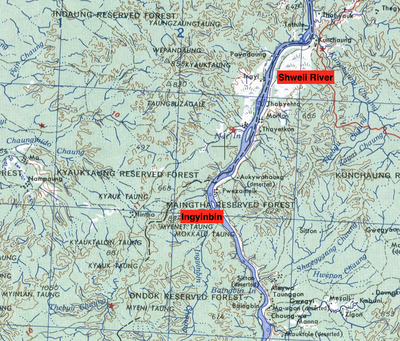

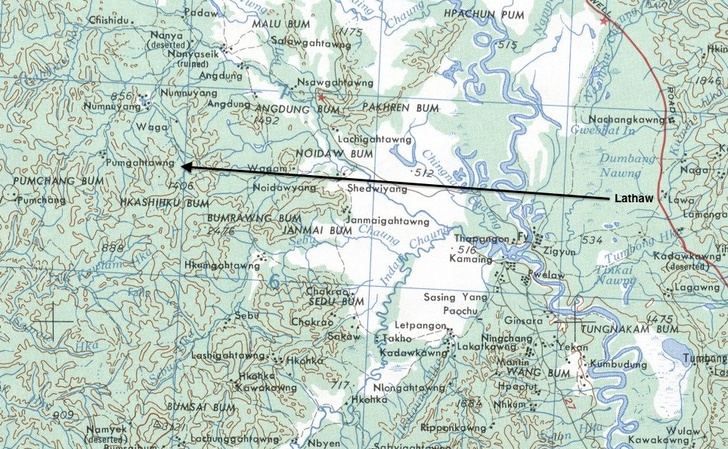

As mentioned earlier, it is my belief that the name Fallow is a mispronunciation of another Gurkha officer from Operation Longcloth, possibly Lt. John Fowler, whose story is featured alphabetically on this website page. Shown below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including Rifleman Aita Sing Gurung's statement and a map of the area around Kalewa on the Chindwin River. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Rank: Lieutenant

Service No: Not known

Regiment/Service: 3rd Battalion, the 2nd Gurkha Regiment.

Chindit Column: 1

Other details:

Lt. Fallow is mentioned in the missing in action files for the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade in 1943. However, no one of that name has ever been reported as a member of the first Chindit expedition and I wonder if this soldier's name has been incorrectly spelled or mispronounced by a Gurkha Riflemen upon interrogation after the operation was concluded?

Fallow is attributed to No. 1 Column on Operation Longcloth, commanded by Major George Dunlop MC, formerly of the Black Watch Regiment. He is listed, alongside another mysterious and unaccounted for officer, as part of a witness statement given by the Gurkha Rifleman 27039 Aita Sing Gurung.

This Gurkha remembers these two officers as being part of a small dispersal party who had marched from the Irrawaddy in the company of Major Dunlop and who had been disturbed by a Japanese patrol close to the Chindwin River in early May 1943. The report goes on to describe how Lts. Fallow and Coyle (?) were subsequently taken prisoner after this incident and were held initially in a POW camp at Kalewa, before ending up at Rangoon Jail. No officers by these names have ever been recorded as being prisoners of war in Rangoon or at any of the other camps used by the Japanese in relation to Chindit detainees.

As mentioned earlier, it is my belief that the name Fallow is a mispronunciation of another Gurkha officer from Operation Longcloth, possibly Lt. John Fowler, whose story is featured alphabetically on this website page. Shown below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including Rifleman Aita Sing Gurung's statement and a map of the area around Kalewa on the Chindwin River. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

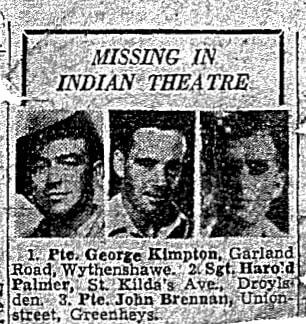

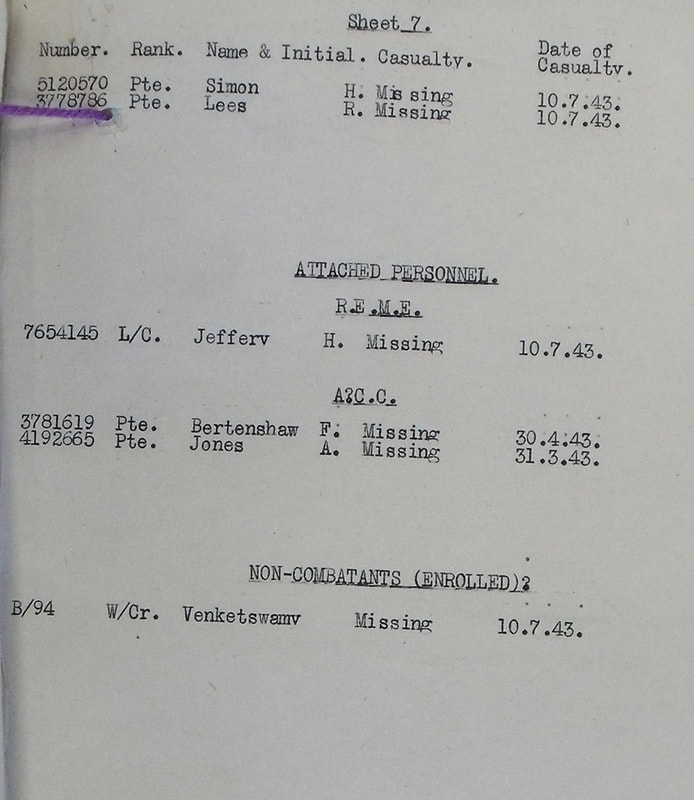

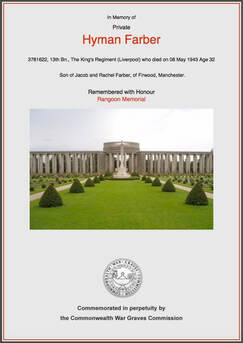

FARBER, HYMAN

Rank: Private

Service No: 3781622

Date of Death: 08/05/1943

Age: 32

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

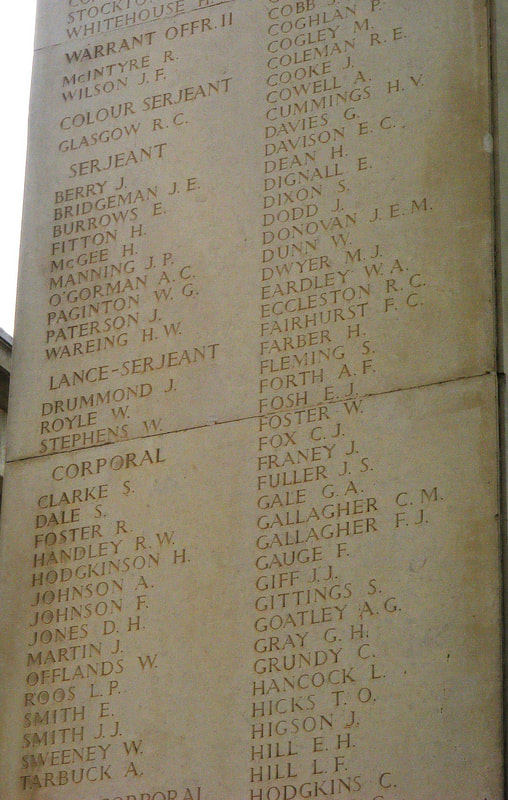

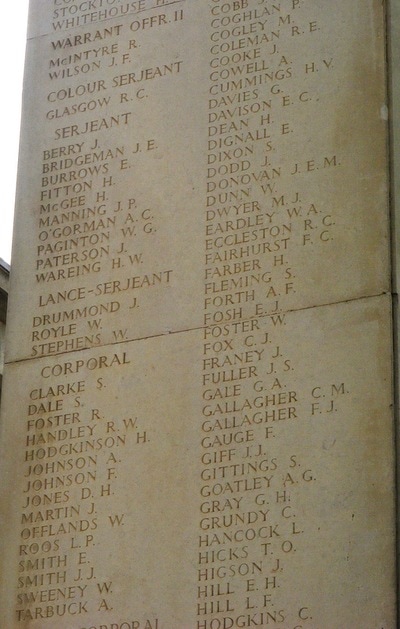

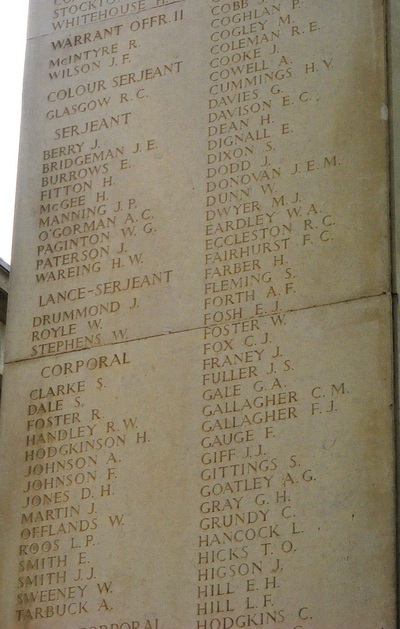

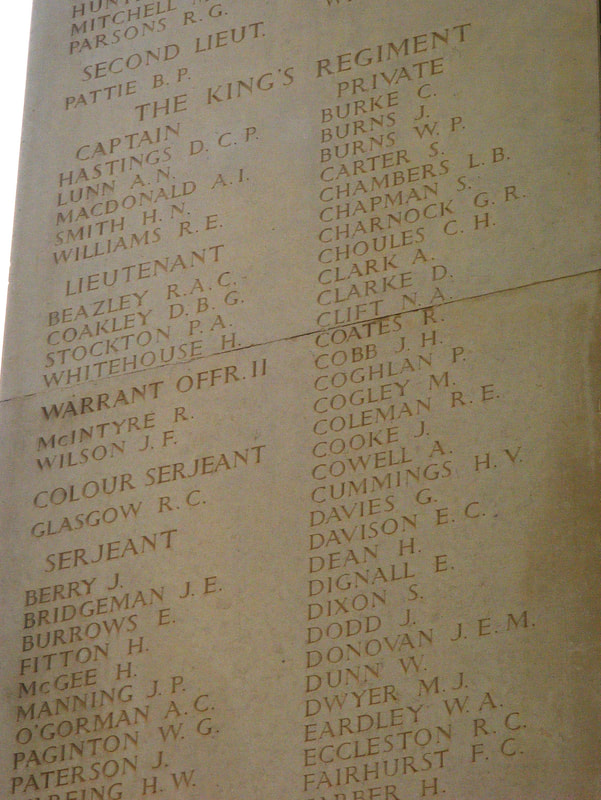

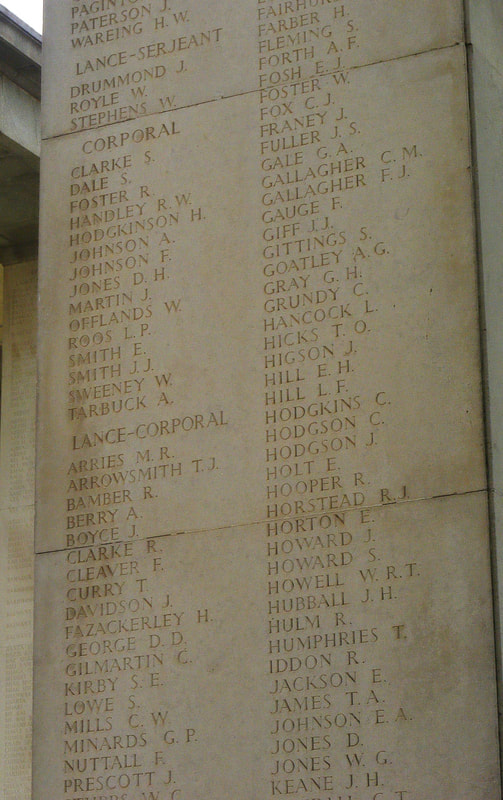

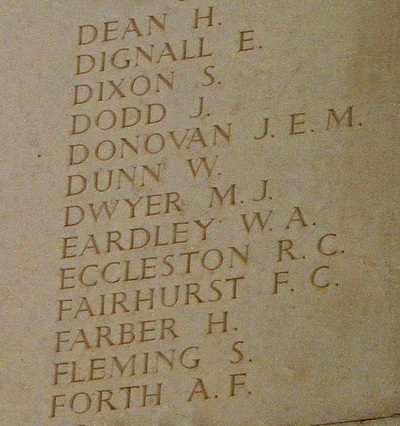

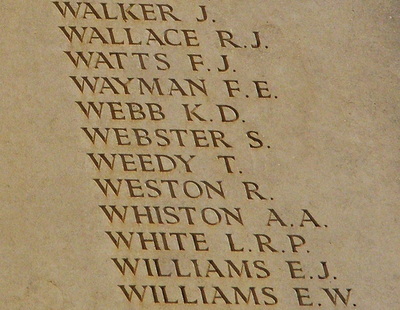

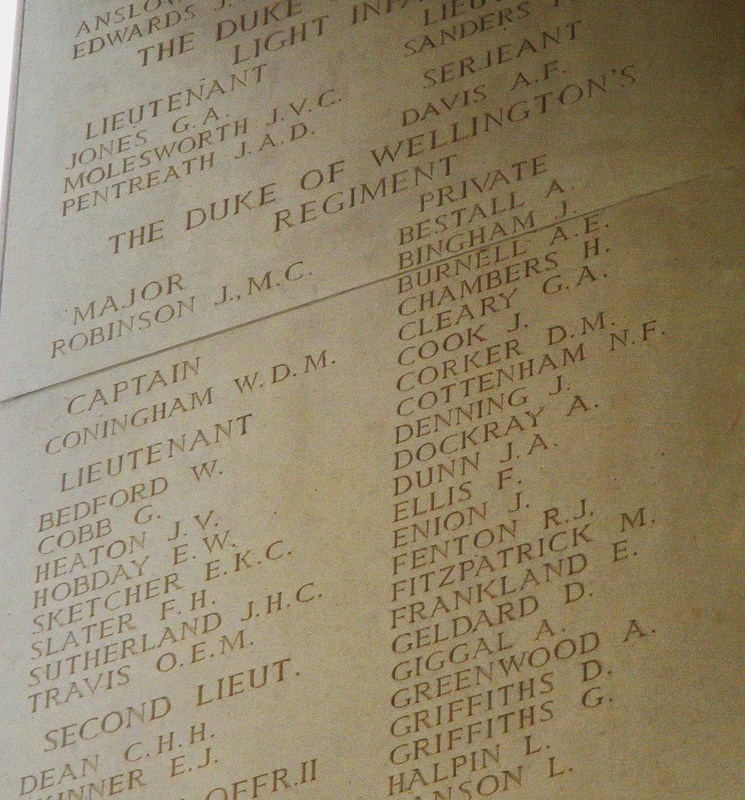

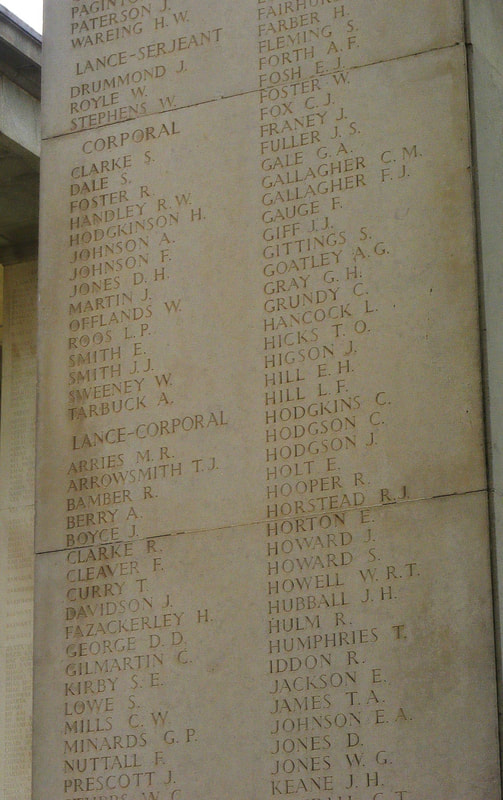

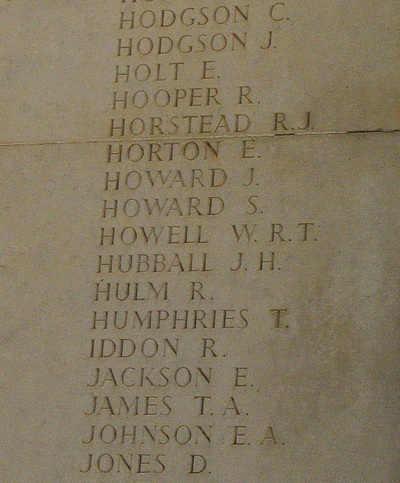

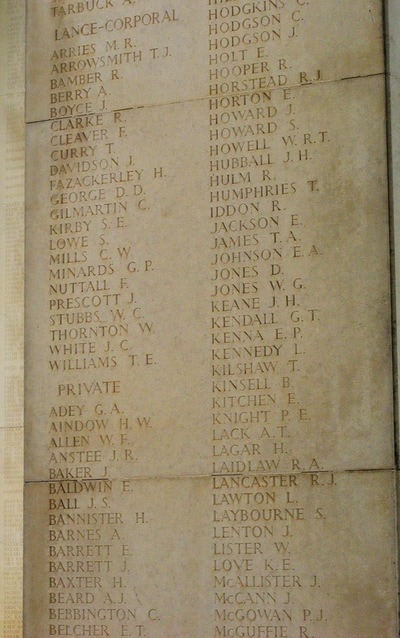

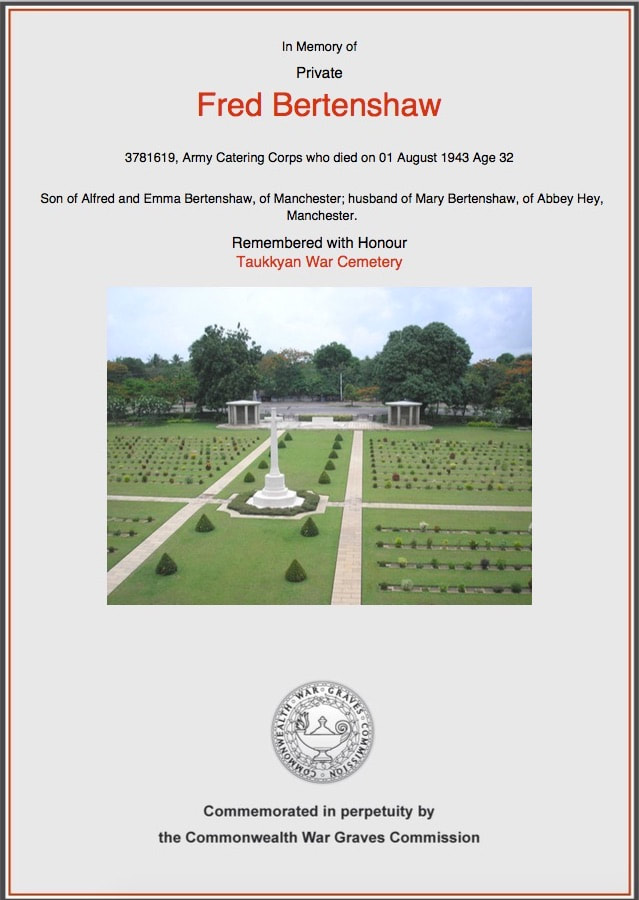

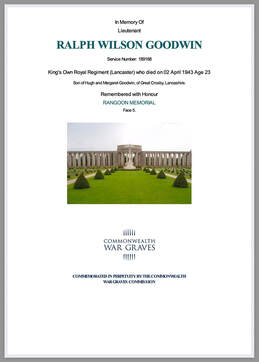

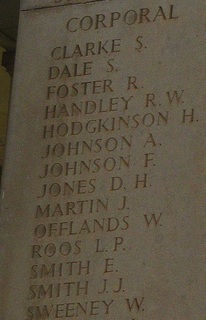

Memorial: Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial, Taukkyan War Cemetery

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/1292294/farber,-hyman/

Chindit Column: Northern Group Head Quarters

Other details:

Hyman Farber was born on the 22nd November 1910 and was the son of Jacob and Rachel Farber, former Russian immigrants from Firwood in Manchester. Hyman worked as a raincoat machinist at home alongside his brother and other family members, whilst his father's occupation is recorded as a paper hanger.

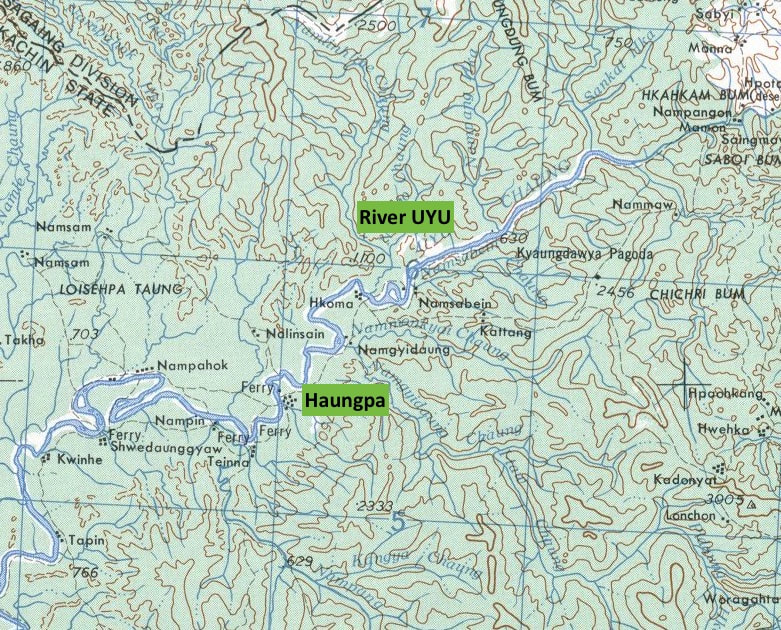

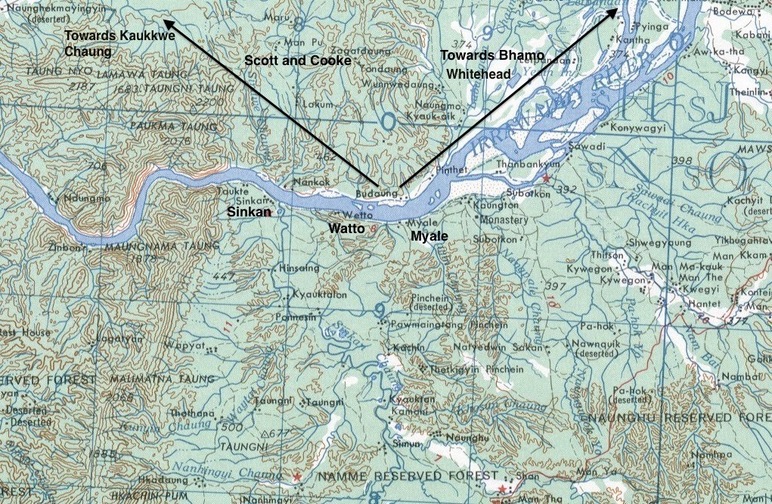

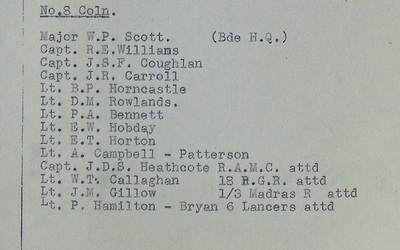

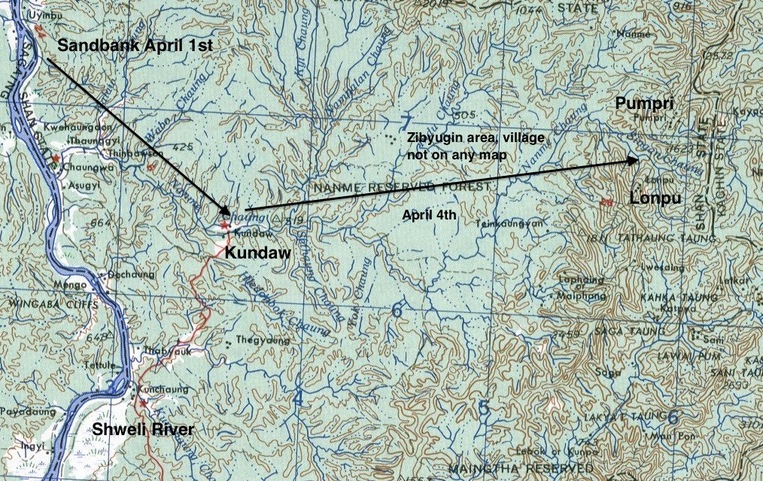

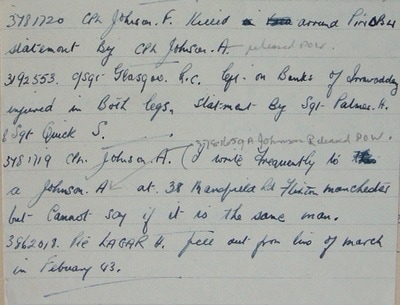

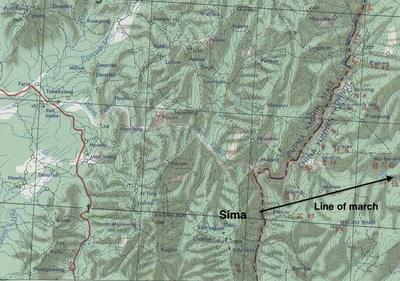

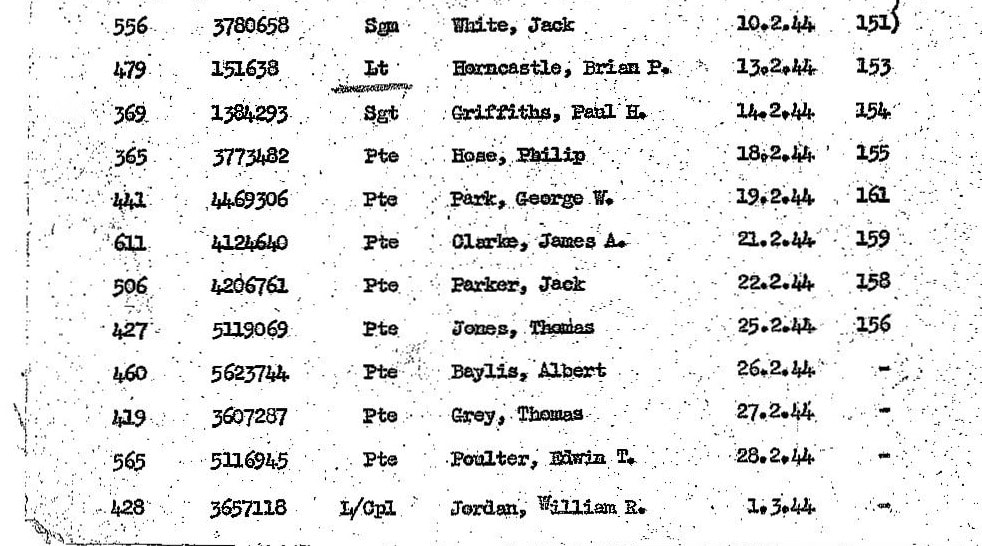

Northern Group Head Quarters commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel S.A. Cooke, was the central command centre for Chindit columns 4, 5, 7 and 8 during Operation Longcloth. This HQ worked in close proximity to No. 8 Column for almost the entire expedition and it was with this column, commanded by Major Walter Purcell Scott of the King's Regiment, that the Head Quarters returned to India. It was during the return journey to India that Pte. Farber was lost to his unit on the 8th May 1943. The missing in action listings for the group simply state that Pte. Farber alongside Pte. J. Brennan were missing from the line of march on the above date approximately two miles from the Burmese village of Haungpa, located close to the Uyu River.

One of the officers present with the unit, Lt. Peter Bennett gave the following witness statement:

In regards: 3781620 J. Brennan and 3781622 H. Farber.

The above mentioned men were last seen on the afternoon of May 8th 1943, about two miles from the village of Haungpa (SB. 7054) on the River Uyu. The column had proceeded about half a mile along the side track off the main Kamaing-Haungpa Road, two miles east of the village (Haungpa), when it was reported that the two missing men were not with the party.

A section returned to the main track and searched half a mile in each direction for about an hour without success. It is possible that the two missing men did not see the column turn off and walked on down the main track towards the village which was occupied by the Japanese.

This statement is certified as true by Lt. George Henry Borrow, 2/IC Northern Group Head Quarters.

No further information was ever gained about these two men and for this reason, they are remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery. The memorial was constructed to remember the 26,000 casualties who perished during the Burma Campaign, but who have no known grave or resting place. From research on line I have learned that Hyman Farber is also remembered at the Blackley Jewish Cemetery in Greater Manchester.

NB. I noticed whilst collating this short story, that the Army service numbers of Hyman Farber and John Brennan are only two digits apart. This makes me wonder whether these two men were already long-time friends from their original enlistment into the King's Regiment in 1941 and that it is no coincidence that they served together in Burma during Operation Longcloth and became lost together on the 8th May 1943.

I suppose this is something that we will never really know.

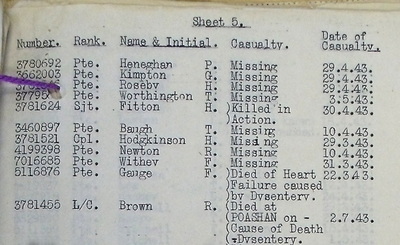

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including a map of the area around Haungpa on the Uyu River and a photograph of Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial showing Hyman Farber's name. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Rank: Private

Service No: 3781622

Date of Death: 08/05/1943

Age: 32

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial, Taukkyan War Cemetery

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/1292294/farber,-hyman/

Chindit Column: Northern Group Head Quarters

Other details:

Hyman Farber was born on the 22nd November 1910 and was the son of Jacob and Rachel Farber, former Russian immigrants from Firwood in Manchester. Hyman worked as a raincoat machinist at home alongside his brother and other family members, whilst his father's occupation is recorded as a paper hanger.

Northern Group Head Quarters commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel S.A. Cooke, was the central command centre for Chindit columns 4, 5, 7 and 8 during Operation Longcloth. This HQ worked in close proximity to No. 8 Column for almost the entire expedition and it was with this column, commanded by Major Walter Purcell Scott of the King's Regiment, that the Head Quarters returned to India. It was during the return journey to India that Pte. Farber was lost to his unit on the 8th May 1943. The missing in action listings for the group simply state that Pte. Farber alongside Pte. J. Brennan were missing from the line of march on the above date approximately two miles from the Burmese village of Haungpa, located close to the Uyu River.

One of the officers present with the unit, Lt. Peter Bennett gave the following witness statement:

In regards: 3781620 J. Brennan and 3781622 H. Farber.

The above mentioned men were last seen on the afternoon of May 8th 1943, about two miles from the village of Haungpa (SB. 7054) on the River Uyu. The column had proceeded about half a mile along the side track off the main Kamaing-Haungpa Road, two miles east of the village (Haungpa), when it was reported that the two missing men were not with the party.

A section returned to the main track and searched half a mile in each direction for about an hour without success. It is possible that the two missing men did not see the column turn off and walked on down the main track towards the village which was occupied by the Japanese.

This statement is certified as true by Lt. George Henry Borrow, 2/IC Northern Group Head Quarters.

No further information was ever gained about these two men and for this reason, they are remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery. The memorial was constructed to remember the 26,000 casualties who perished during the Burma Campaign, but who have no known grave or resting place. From research on line I have learned that Hyman Farber is also remembered at the Blackley Jewish Cemetery in Greater Manchester.

NB. I noticed whilst collating this short story, that the Army service numbers of Hyman Farber and John Brennan are only two digits apart. This makes me wonder whether these two men were already long-time friends from their original enlistment into the King's Regiment in 1941 and that it is no coincidence that they served together in Burma during Operation Longcloth and became lost together on the 8th May 1943.

I suppose this is something that we will never really know.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including a map of the area around Haungpa on the Uyu River and a photograph of Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial showing Hyman Farber's name. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

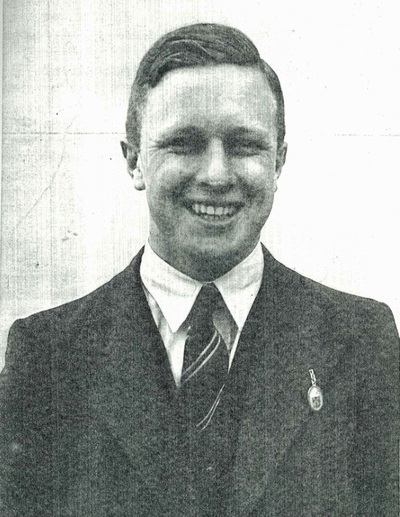

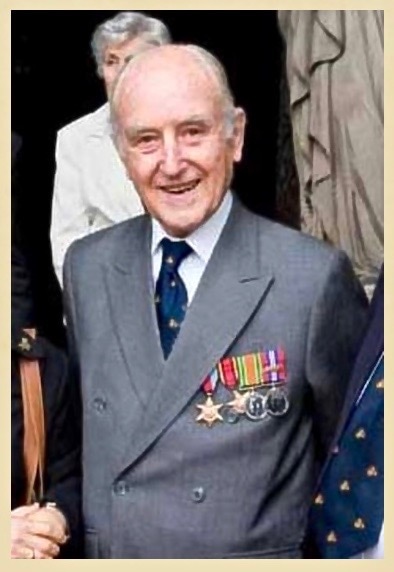

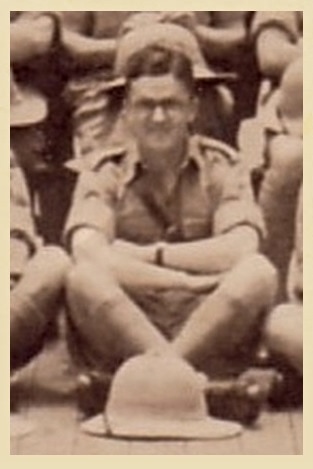

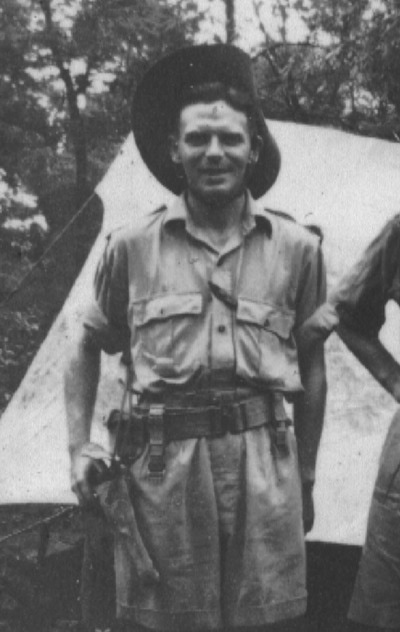

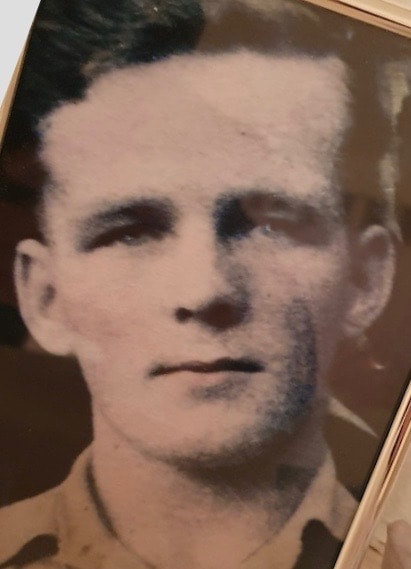

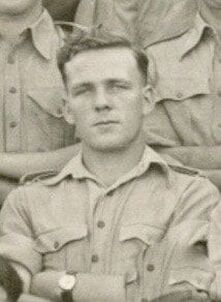

George Bell.

George Bell.

Update 12/12/2020.

From the Chindit memoirs of Lance Corporal George Bell, comes a more detailed explanation of where and when John Brennan and Hyman Farber were lost to their column on Operation Longcloth:

After recrossing the Irrawaddy, we marched sometimes 20 miles in a day, crossing the railway and two more minor rivers. One day we came across a Burmese man who could speak English, his story did not ring true to us and so we kept him with us under guard. After collecting more rice in the next village the headman warned us that this man had recently been in the company of a Jap patrol. It was decide that it was too dangerous to let him go and that he should be shot. My section took him away from the main group and one of the Burma Rifle soldiers shot him through the head. This left us with the feeling of being judge, jury and executioner.

We slogged on for a few more days, by which time our food supplies had completely run out. I brewed up with a tea bag that must have been used at least twenty times before. Around midday we were walking along a dried-up river bed when we saw some parachutes caught up in a group of trees. We approached them carefully concerned it might be a Jap ambush or booby trap, but it was a definite ration dropping, presumably for another of our parties. The packs gave us eight days rations per man, exactly eight days later we were in a small village when a British plane came over and spotted us on the ground. They dropped a message canister asking if we needed supplies, we answered them using cut parachute strips to mark out our numbers and needs. We waited for almost two days hoping they would return, but reluctantly we moved on, worried about the dangers of staying put in one place for too long.

Not long after that incident two of our lads whose feet were in an awful state needed time to rest and bathe their feet in a stream. The order was given to move off, but the two men said they wanted to remain for a short while longer and would attempt to catch us up later. They never returned to the main group and we heard later that they had been killed by the Japanese.

From the Chindit memoirs of Lance Corporal George Bell, comes a more detailed explanation of where and when John Brennan and Hyman Farber were lost to their column on Operation Longcloth:

After recrossing the Irrawaddy, we marched sometimes 20 miles in a day, crossing the railway and two more minor rivers. One day we came across a Burmese man who could speak English, his story did not ring true to us and so we kept him with us under guard. After collecting more rice in the next village the headman warned us that this man had recently been in the company of a Jap patrol. It was decide that it was too dangerous to let him go and that he should be shot. My section took him away from the main group and one of the Burma Rifle soldiers shot him through the head. This left us with the feeling of being judge, jury and executioner.

We slogged on for a few more days, by which time our food supplies had completely run out. I brewed up with a tea bag that must have been used at least twenty times before. Around midday we were walking along a dried-up river bed when we saw some parachutes caught up in a group of trees. We approached them carefully concerned it might be a Jap ambush or booby trap, but it was a definite ration dropping, presumably for another of our parties. The packs gave us eight days rations per man, exactly eight days later we were in a small village when a British plane came over and spotted us on the ground. They dropped a message canister asking if we needed supplies, we answered them using cut parachute strips to mark out our numbers and needs. We waited for almost two days hoping they would return, but reluctantly we moved on, worried about the dangers of staying put in one place for too long.

Not long after that incident two of our lads whose feet were in an awful state needed time to rest and bathe their feet in a stream. The order was given to move off, but the two men said they wanted to remain for a short while longer and would attempt to catch us up later. They never returned to the main group and we heard later that they had been killed by the Japanese.

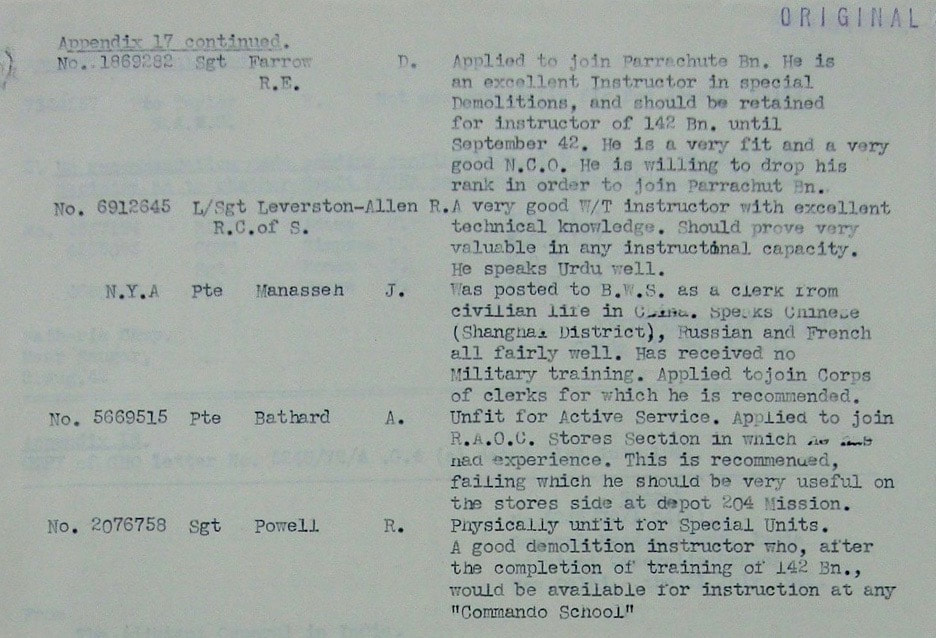

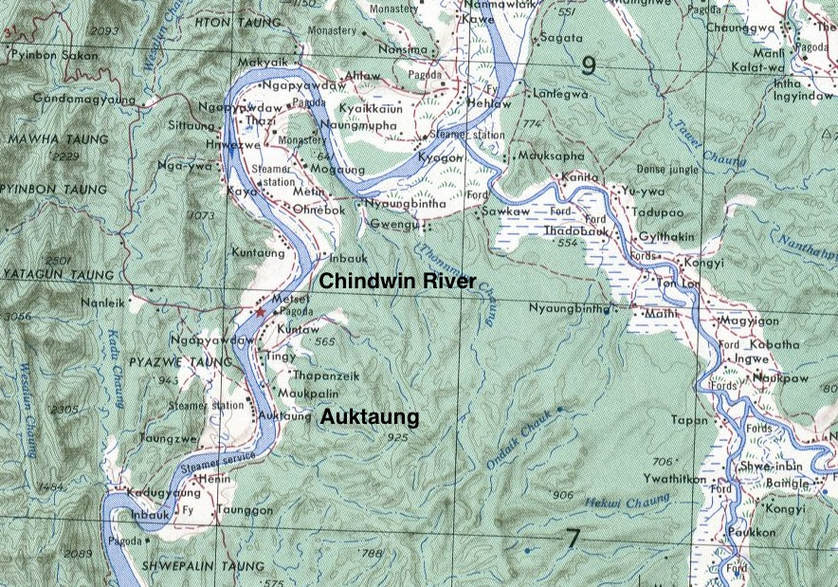

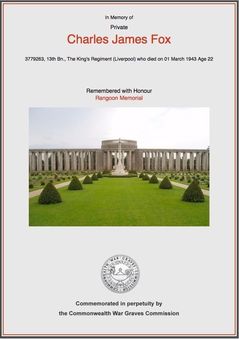

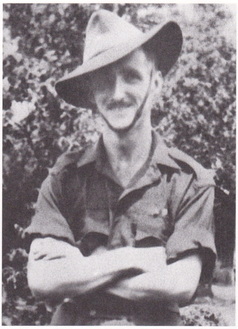

FARROW, DENNIS

Rank: Sergeant

Service No: 1869282

Age: 32

Regiment/Service: Royal Engineers, attached The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

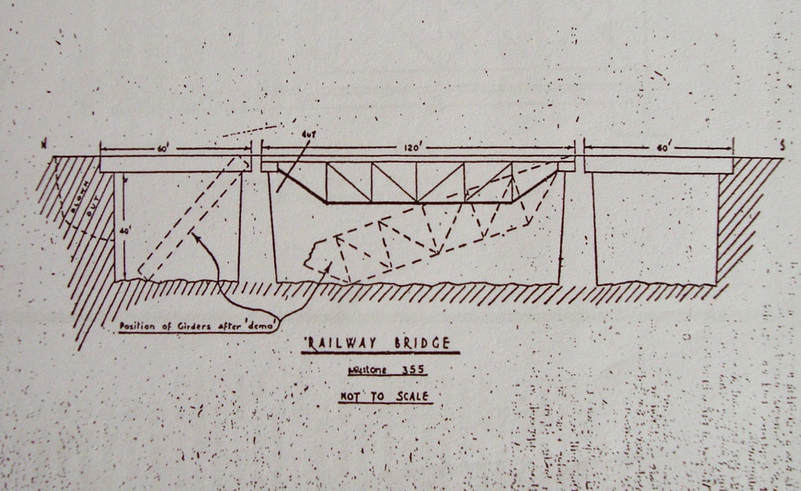

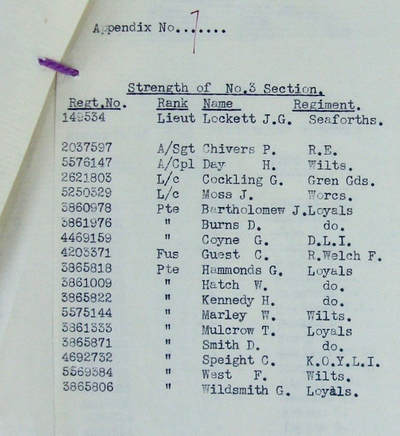

Chindit Column: Demolitions Instructor (Col. 1).

Other details:

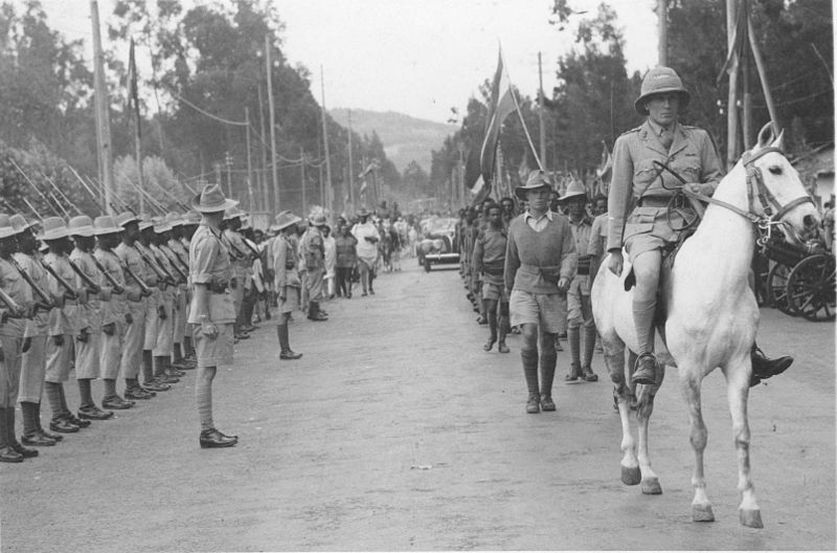

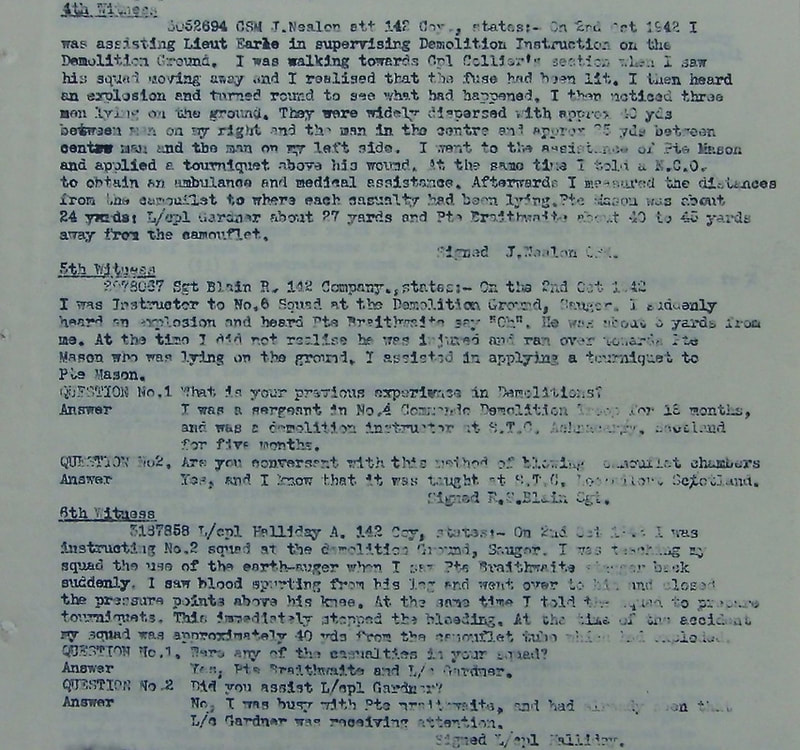

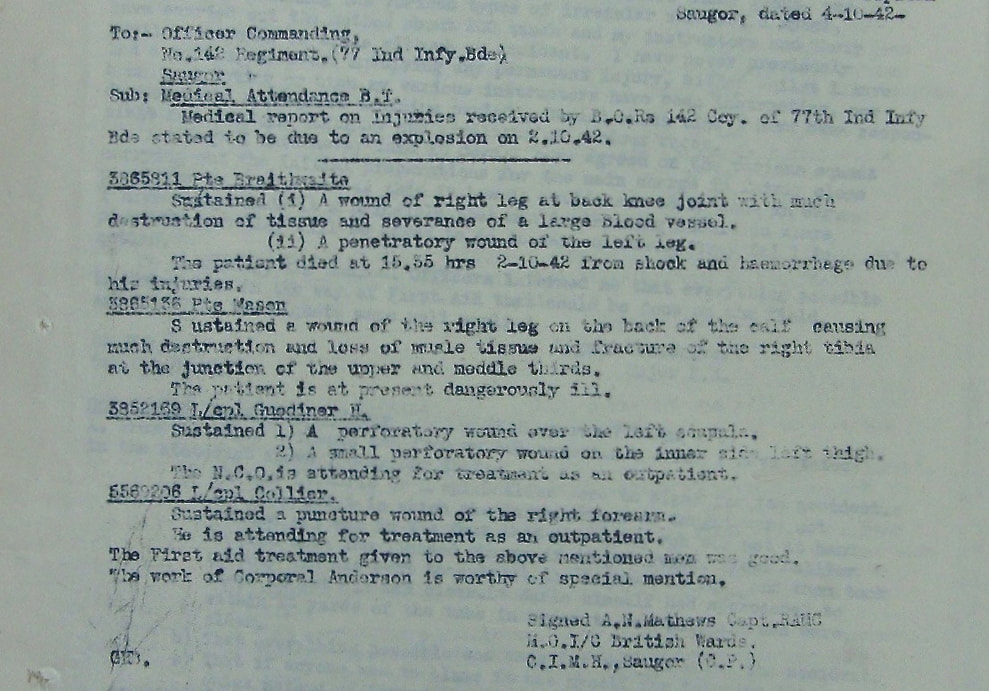

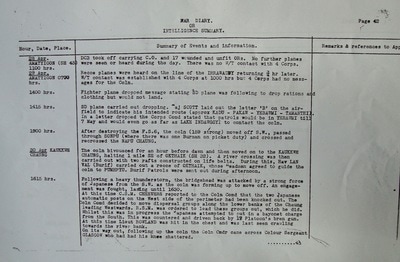

Dennis 'Dinky' Farrow served alongside the 204 Military Mission into China, having previously teamed up with Mike Calvert at the Bush Warfare School in Maymyo. He also served with Calvert during the retreat from Burma in early 1942 as the Japanese first advanced across the country. His team of commandos, led by Major Calvert were involved in several ambushes upon the Japanese, including using a paddle-steamer on the Irrawaddy to attack the enemy as they moved adjacent to the river. He was also given the task of blowing the Goktiek Viaduct and had laid many explosive charges in readiness for the demolition, only to be told that the Chinese had ordered that the structure be left unmolested in case they might need to use it.

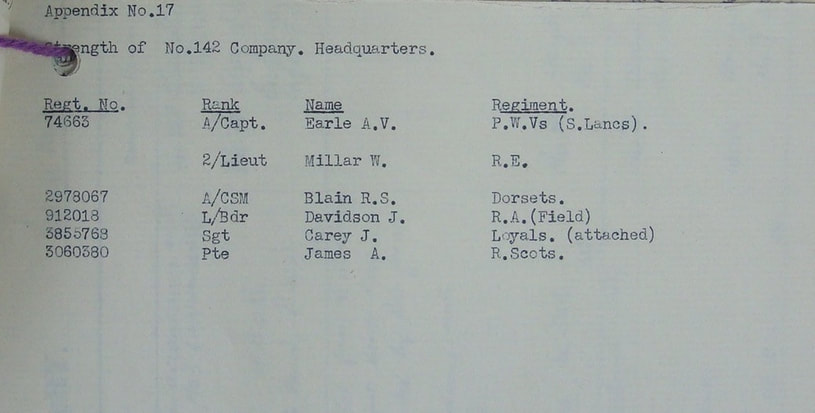

Having survived all this excitement in the first half of 1942, Farrow then followed Mike Calvert to the Chindit training camp at Saugor and became a demolitions instructor for 142 Commando. It is anecdotally suggested that he taught the commando sections of No. 1 & 2 Column in the art of demolition, before they took their newly attained skills into Burma on Operation Longcloth. It is known that Sergeant Farrow did not actually take part on the first Wingate expedition in 1943 and went on from Saugor to join one of the Parachute units already based in India.

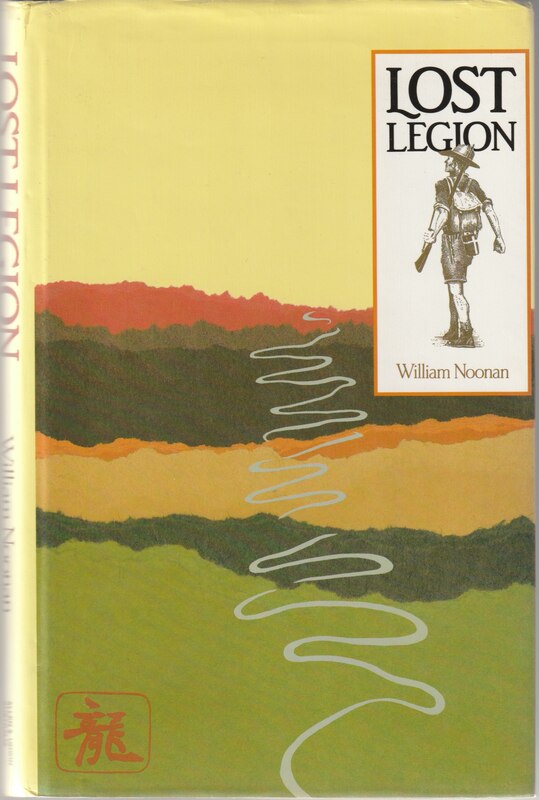

Dennis Farrow is mentioned in the book The Lost Legion, by William Noonan. The book describes the adventures of the Australian Contingent who made up one-third of the 204 Military Mission in 1942. One quote from the book recounts Farrow's time with Mike Calvert during the Japanese advance into Burma and the loss of a comrade named Bob Ward:

Japanese infiltration techniques aided by treacherous Burmese guides were to account for Bob Ward, the only English-born member of the AIF Contingent. Dennis "Dinky' Farrow, an explosives expert at the Bush Warfare School, had been out with Ward on a recce of the western bank of the Irrawaddy at Padaung. He recalled that they had sighted no enemy and had returned across the river at dusk and slept alongside a large group of Marines and Mike Calvert's men in a Police compound.

"I remember waking at a noise (stated Farrow) and looking out of the window and seeing a great flock of Japanese pouring through the entrance door. Almost in a a reflex I was out the window with my Tommy gun and crouched down in the darkness beneath the hut and lay for a while hoping others would join me. There was no sign of Bob Ward and all hell had broken loose in the compound. I got off a few bursts with my gun, but couldn't be certain I was firing at the enemy only. I finally got away with Cush Carey from the Malaya Contingent and had gone about three miles across stoney fields before I realised I was still in bare feet. Another fellow we picked up the next day said he had escaped from a line-up of British prisoners on whom the Japs were practising with bayonets, and these he said included Bob Ward and Hugo Calthorp."

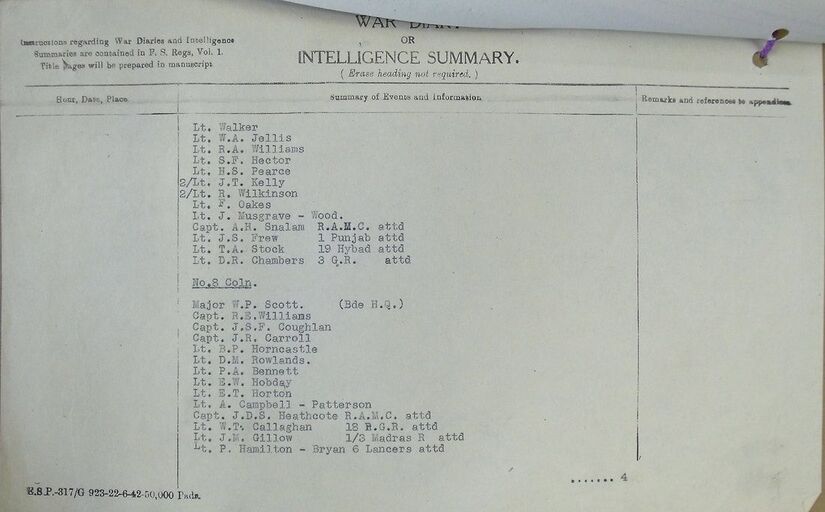

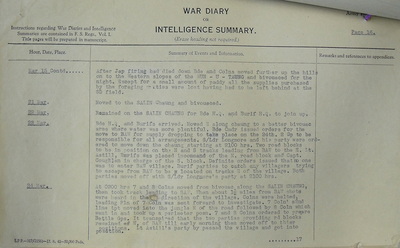

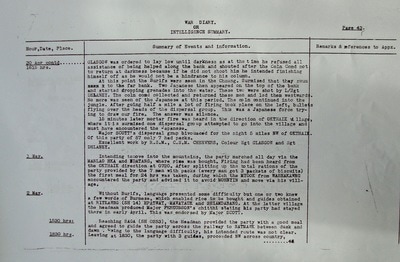

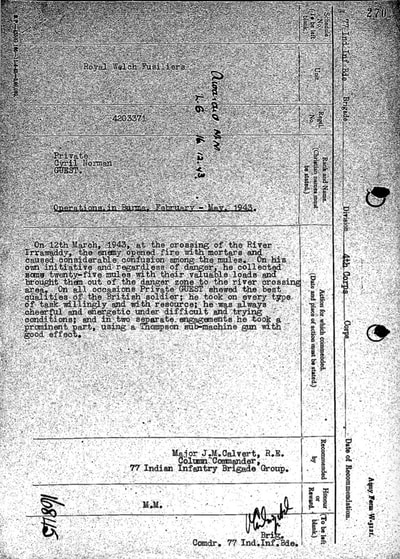

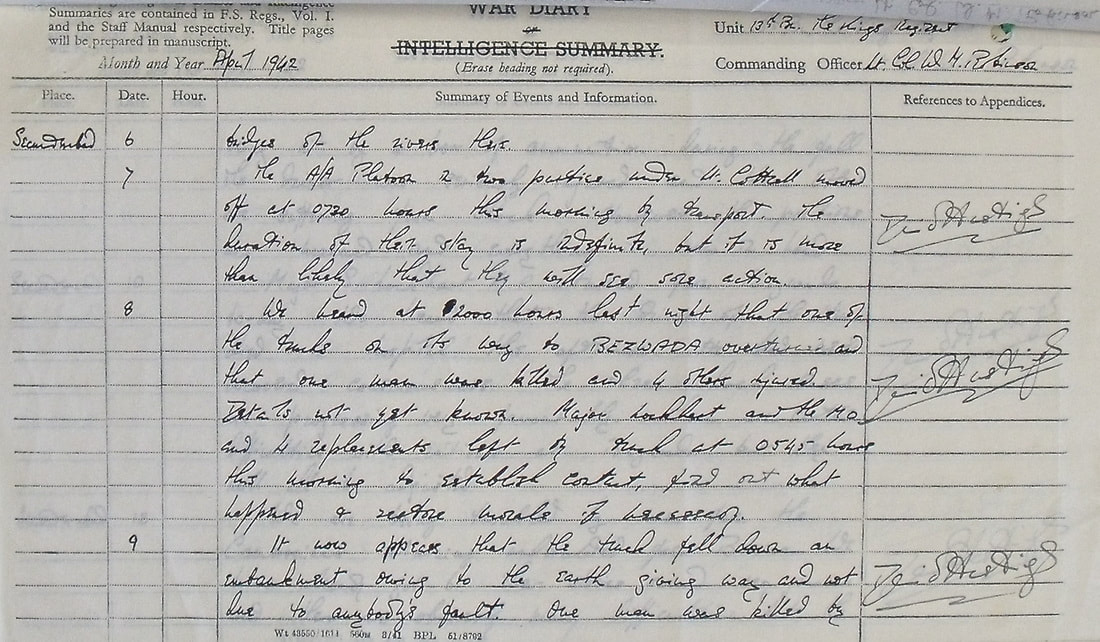

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including a page from the 142 Commando war diary describing Dennis Farrow's attributes and his desire to move on to a Parachute Battalion. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

To view the CWGC details for Pte. Robert Ward and Captain Hugo Calthorp, who are both remembered upon the Rangoon War Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery, please click on the following links:

www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2528279/robert-ward/

www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2506718/everard-hugh-dion-calthrop/

Rank: Sergeant

Service No: 1869282

Age: 32

Regiment/Service: Royal Engineers, attached The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Chindit Column: Demolitions Instructor (Col. 1).

Other details:

Dennis 'Dinky' Farrow served alongside the 204 Military Mission into China, having previously teamed up with Mike Calvert at the Bush Warfare School in Maymyo. He also served with Calvert during the retreat from Burma in early 1942 as the Japanese first advanced across the country. His team of commandos, led by Major Calvert were involved in several ambushes upon the Japanese, including using a paddle-steamer on the Irrawaddy to attack the enemy as they moved adjacent to the river. He was also given the task of blowing the Goktiek Viaduct and had laid many explosive charges in readiness for the demolition, only to be told that the Chinese had ordered that the structure be left unmolested in case they might need to use it.

Having survived all this excitement in the first half of 1942, Farrow then followed Mike Calvert to the Chindit training camp at Saugor and became a demolitions instructor for 142 Commando. It is anecdotally suggested that he taught the commando sections of No. 1 & 2 Column in the art of demolition, before they took their newly attained skills into Burma on Operation Longcloth. It is known that Sergeant Farrow did not actually take part on the first Wingate expedition in 1943 and went on from Saugor to join one of the Parachute units already based in India.

Dennis Farrow is mentioned in the book The Lost Legion, by William Noonan. The book describes the adventures of the Australian Contingent who made up one-third of the 204 Military Mission in 1942. One quote from the book recounts Farrow's time with Mike Calvert during the Japanese advance into Burma and the loss of a comrade named Bob Ward:

Japanese infiltration techniques aided by treacherous Burmese guides were to account for Bob Ward, the only English-born member of the AIF Contingent. Dennis "Dinky' Farrow, an explosives expert at the Bush Warfare School, had been out with Ward on a recce of the western bank of the Irrawaddy at Padaung. He recalled that they had sighted no enemy and had returned across the river at dusk and slept alongside a large group of Marines and Mike Calvert's men in a Police compound.

"I remember waking at a noise (stated Farrow) and looking out of the window and seeing a great flock of Japanese pouring through the entrance door. Almost in a a reflex I was out the window with my Tommy gun and crouched down in the darkness beneath the hut and lay for a while hoping others would join me. There was no sign of Bob Ward and all hell had broken loose in the compound. I got off a few bursts with my gun, but couldn't be certain I was firing at the enemy only. I finally got away with Cush Carey from the Malaya Contingent and had gone about three miles across stoney fields before I realised I was still in bare feet. Another fellow we picked up the next day said he had escaped from a line-up of British prisoners on whom the Japs were practising with bayonets, and these he said included Bob Ward and Hugo Calthorp."

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including a page from the 142 Commando war diary describing Dennis Farrow's attributes and his desire to move on to a Parachute Battalion. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

To view the CWGC details for Pte. Robert Ward and Captain Hugo Calthorp, who are both remembered upon the Rangoon War Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery, please click on the following links:

www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2528279/robert-ward/

www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2506718/everard-hugh-dion-calthrop/

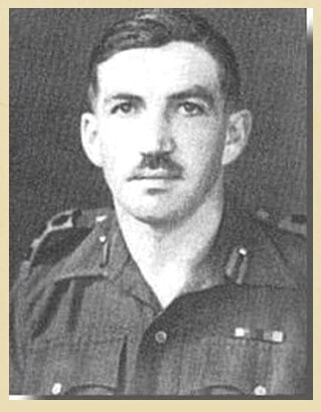

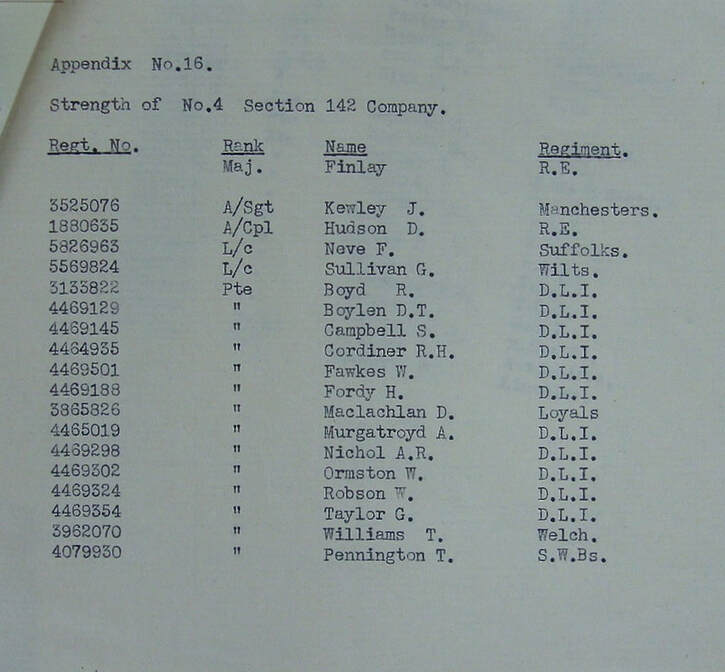

FINLAY, DAVID JOHN

Rank: Major

Service No: 223260

Regiment/Service: Royal Engineers (142 Commando) attached 3/2 Gurkha Rifles.

Chindit Column: 4

Other details:

Major David John Finlay, from Kogarah (Sydney) in Australia, was the commanding officer for the Commando Section of No. 4 Column on Operation Longcloth. A mining engineer in Malaya before the war, he had previously served with the Malayan Volunteer Forces in Singapore, doing spectacular sabotage work in the face of the advancing Japanese forces in February 1942. After successfully evading capture from Singapore, Finlay journeyed by sea via Phuket Island and Ceylon to India, where he took up a position with the Royal Engineers, eventually joining the Chindit training camp at Saugor in the early autumn of 1942. No. 4 Column were made up predominately by Gurkha Rifle troops, with the Commando Section one of the few units of the column to be made up of solely British soldiers.

Major Finlay (sometimes spelled Findlay) is only mentioned once from amongst the writings in relation to the first Wingate expedition and this comes from a debrief paper penned by one of his colleagues from 4 Column, Lt. J. H. Stewart-Jones:

I have read with interest the account in the recent issue of the Regimental News; of the part played by the 3rd Battalion during the operations of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade in Burma. Erroneous impressions are liable to be formed by people unconnected with the battalion who may have or read the official report on operations of the above mentioned Brigade.

I therefore feel it incumbent upon me to ask that this account of the conduct of four Rifleman be placed on the Regimental record. These four were members of No. 4 Column, commanded until March 1st 1943 by Major Conron, 2nd KEO Gurkha Rifles. On March 1st, Major Bromhead, (Royal Berks) took over command and the column ordered to provide the diversion, by road blocks and other means necessary to allow the other elements of the Brigade (cols. 3, 5, 7 and 8) to proceed to their objectives.

The Burma Rifles section commanded by Lt. FW. Burn was ordered to recce the village of Pinbon and surrounding areas. This party was ambushed and Lt. Burn wounded and the reconnaissance abandoned. Myself and the four Riflemen volunteered to locate the patrol and wounded officer and bring them back into column. During this time we encountered the enemy, which we defeated at no cost to ourselves. All advantage had been with the enemy, but the intelligence and obedience of these Gurkhas to all commands, wrestled this away and we forced a successful conclusion. The discipline of these men under fire was of the highest order and in keeping with Gurkha traditions.

The following day No. 4 Column proceeded south under Major Bromhead and halted in column snake, half a mile of Pinbon. The last two groups of our men and animals were still in the process of crossing a small river which bounded Pinbon, when the first Japanese grenades and mortars fell upon the column. The enemy attempted to cut the line in four places, attacking our flanks.

No orders for any definite plan of action came from HQ, and with visibility down to just 30 yards, I ordered Subedar Tikajit Pun to withdraw our section of the column north over the river. After the action had lasted around twenty minutes and withdrawing through various engagements with the enemy, we collected 150 men and 30 animals. I ordered Lt. Green (2nd KEO Gurkha Rifles) to lead the column one mile to the north while we held the river with a platoon.

That same evening we caught Lt. Green up and headed south through primary jungle. Two days later we were down to 137 all ranks. I handed command of the column to the most senior officer present, Captain Findlay of the Royal Engineers and we decided to bivouac in the jungle and send out a patrol to contact Brigade HQ (Wingate). Our wireless was useless, food non-existent apart from our bullocks, which of course the Gurkhas could not very well eat and the men were in all opinion too weak to continue.

In the end Lt. Stewart-Jones and his small party set off in search of 77 Brigade Head Quarters and did eventually bump into No. 8 Column, with whom they remained for the next six weeks. Major Finlay and the rest of the separated men headed west and successfully re-crossed the Chindwin River a few days later. In late 1945, Finlay was awarded the MBE (London Gazette 1st January 1946) for his efforts against the Japanese, before relinquishing his commission (8th March 1946) with the honorary rank of Major. NB: Many thanks to Dr. Andrew Kilsby for his assistance with this narrative.

To read more about the adventures of Lt. Stewart-Jones, please click on the following link: Lt. Jock Stewart-Jones

To read more about some of the men who made up Major Finlay's Commando Section on Operation Longcloth in 1943, please click on the following link: The Bricklayers of Column 4 Commando

Rank: Major

Service No: 223260

Regiment/Service: Royal Engineers (142 Commando) attached 3/2 Gurkha Rifles.

Chindit Column: 4

Other details:

Major David John Finlay, from Kogarah (Sydney) in Australia, was the commanding officer for the Commando Section of No. 4 Column on Operation Longcloth. A mining engineer in Malaya before the war, he had previously served with the Malayan Volunteer Forces in Singapore, doing spectacular sabotage work in the face of the advancing Japanese forces in February 1942. After successfully evading capture from Singapore, Finlay journeyed by sea via Phuket Island and Ceylon to India, where he took up a position with the Royal Engineers, eventually joining the Chindit training camp at Saugor in the early autumn of 1942. No. 4 Column were made up predominately by Gurkha Rifle troops, with the Commando Section one of the few units of the column to be made up of solely British soldiers.

Major Finlay (sometimes spelled Findlay) is only mentioned once from amongst the writings in relation to the first Wingate expedition and this comes from a debrief paper penned by one of his colleagues from 4 Column, Lt. J. H. Stewart-Jones:

I have read with interest the account in the recent issue of the Regimental News; of the part played by the 3rd Battalion during the operations of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade in Burma. Erroneous impressions are liable to be formed by people unconnected with the battalion who may have or read the official report on operations of the above mentioned Brigade.

I therefore feel it incumbent upon me to ask that this account of the conduct of four Rifleman be placed on the Regimental record. These four were members of No. 4 Column, commanded until March 1st 1943 by Major Conron, 2nd KEO Gurkha Rifles. On March 1st, Major Bromhead, (Royal Berks) took over command and the column ordered to provide the diversion, by road blocks and other means necessary to allow the other elements of the Brigade (cols. 3, 5, 7 and 8) to proceed to their objectives.

The Burma Rifles section commanded by Lt. FW. Burn was ordered to recce the village of Pinbon and surrounding areas. This party was ambushed and Lt. Burn wounded and the reconnaissance abandoned. Myself and the four Riflemen volunteered to locate the patrol and wounded officer and bring them back into column. During this time we encountered the enemy, which we defeated at no cost to ourselves. All advantage had been with the enemy, but the intelligence and obedience of these Gurkhas to all commands, wrestled this away and we forced a successful conclusion. The discipline of these men under fire was of the highest order and in keeping with Gurkha traditions.

The following day No. 4 Column proceeded south under Major Bromhead and halted in column snake, half a mile of Pinbon. The last two groups of our men and animals were still in the process of crossing a small river which bounded Pinbon, when the first Japanese grenades and mortars fell upon the column. The enemy attempted to cut the line in four places, attacking our flanks.

No orders for any definite plan of action came from HQ, and with visibility down to just 30 yards, I ordered Subedar Tikajit Pun to withdraw our section of the column north over the river. After the action had lasted around twenty minutes and withdrawing through various engagements with the enemy, we collected 150 men and 30 animals. I ordered Lt. Green (2nd KEO Gurkha Rifles) to lead the column one mile to the north while we held the river with a platoon.

That same evening we caught Lt. Green up and headed south through primary jungle. Two days later we were down to 137 all ranks. I handed command of the column to the most senior officer present, Captain Findlay of the Royal Engineers and we decided to bivouac in the jungle and send out a patrol to contact Brigade HQ (Wingate). Our wireless was useless, food non-existent apart from our bullocks, which of course the Gurkhas could not very well eat and the men were in all opinion too weak to continue.

In the end Lt. Stewart-Jones and his small party set off in search of 77 Brigade Head Quarters and did eventually bump into No. 8 Column, with whom they remained for the next six weeks. Major Finlay and the rest of the separated men headed west and successfully re-crossed the Chindwin River a few days later. In late 1945, Finlay was awarded the MBE (London Gazette 1st January 1946) for his efforts against the Japanese, before relinquishing his commission (8th March 1946) with the honorary rank of Major. NB: Many thanks to Dr. Andrew Kilsby for his assistance with this narrative.

To read more about the adventures of Lt. Stewart-Jones, please click on the following link: Lt. Jock Stewart-Jones

To read more about some of the men who made up Major Finlay's Commando Section on Operation Longcloth in 1943, please click on the following link: The Bricklayers of Column 4 Commando

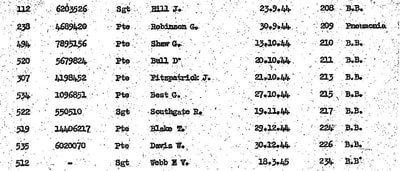

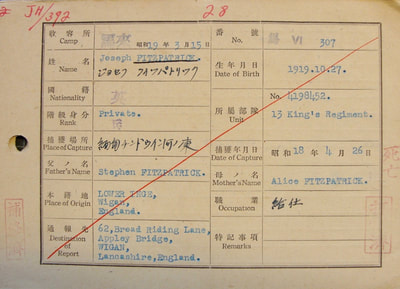

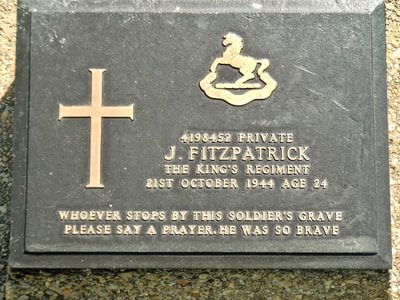

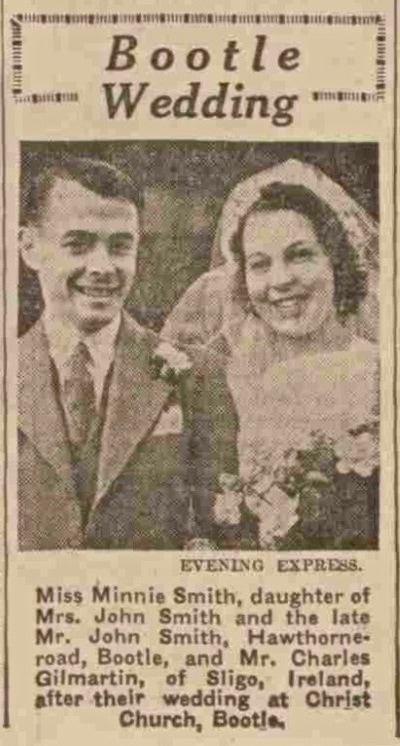

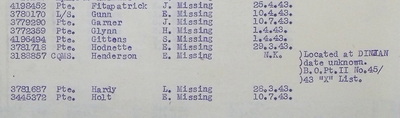

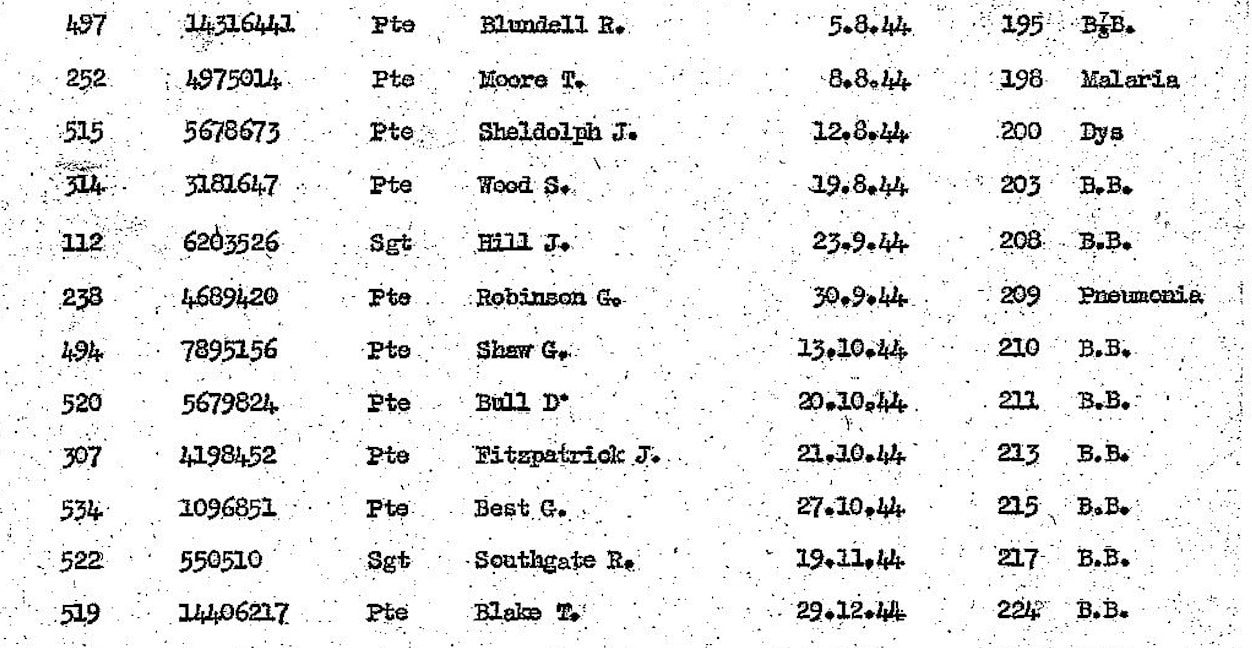

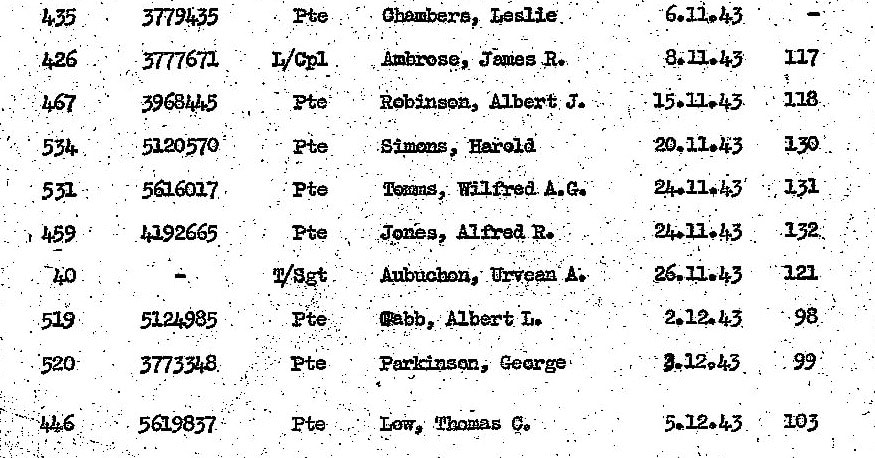

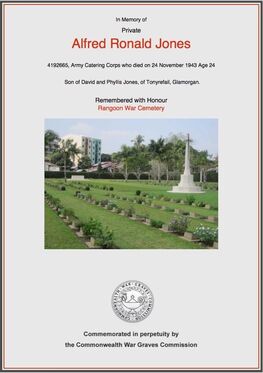

FITZPATRICK, JOSEPH

Rank: Private

Service No: 4198452

Date of Death: 21/10/1944

Age: 24

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Grave Reference 5. D. 1. Rangoon War Cemetery.

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2259957/fitzpatrick,-joseph/

Chindit Column: 5

Other details:

Joseph Fitzpatrick was born on the 27th October 1919 and was the son of Stephen and Alice Fitzpatrick from Appley Bridge in Lancashire. In the years before WW2, Joseph worked both as a waiter in the catering industry and as a doorman for a large Liverpool Hotel. He enlisted into the Army and was originally posted to the Royal Welch Fusiliers, with the Army No. 4198452. Later, whilst in India, Pte. Fitzpatrick was transferred to the 13th Battalion of the King's Liverpool Regiment and was allocated to Chindit Column No. 5 at their training camp located in the jungle scrubland close to the town of Saugor in the Central Provinces of the country.

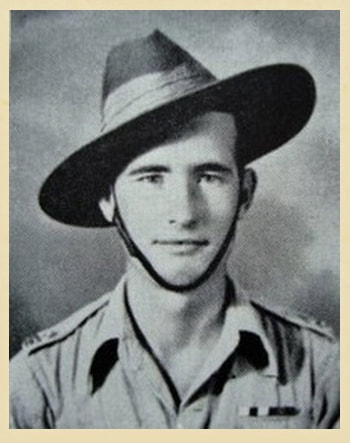

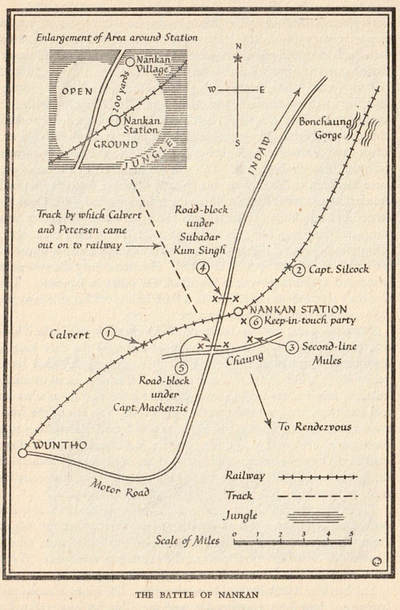

During his time in Burma on Operation Longcloth, Joseph took on the role of groom to Captain Tommy Roberts who commanded the Support Platoon within 5 Column. Apart from the obvious duties in looking after Captain Roberts' horse, Pte. Fitzpatrick was also used as a runner in Burma, delivering messages to Major Fergusson and the other officers from 5 Column. Bernard Fergusson mentions one such occasion in his book, Beyond the Chindwin, when the column were marching towards Bonchaung in early March 1943 and suffered an ambush by a Japanese patrol at a village called Kyaik-in:

On the morning of the 6th of March, everybody got off to time; but before I had marched four hundred yards along the road, Fitzpatrick, Tommy Roberts' groom, came up at a gallop, somewhat flustered. He had been up and down the road for fifteen minutes, unable to spot the point in the jungle where our bivouac had been. (I never bivouacked within five hundred yards of a track).

Tommy was engaged in Kyaik-in village with some Japanese; he had sent Jim Harman back and round to go straight for the gorge, and was fighting it out himself. I asked Fitzpatrick (in civil life a buttons in a Liverpool hotel) for details, but all he knew was that there was a lot of shooting going on, and a lot of bangs, and Tommy had sent him back to warn me. I hastily decided to send the main body straight off across country to Bonchaung. I sent the remaining rifle platoon, now commanded by Gerry Roberts, down the motor-road to the village as fast as it could go, to back up Tommy, while I gave Alec and Duncan their orders. When I had finished, I took Peter Dorans, and followed Gerry.

As I drew near the village, I could hear light machine-guns in action, and the occasional burst of a grenade. The jungle was continuous on the right of the road, but there was a small strip of disused paddy, with some scrubby bushes, on the left; and by the time I arrived (for it took a minute or two to give out the orders to the main body) Gerry's leading Bren section was already in position, and had fired on a small party of Japs.

Obsessed with the importance of avoiding a fight with our own troops, I begged him to be careful, and to work gradually along the track. I saw two men of the original party in the bushes on the right, one of whom was Bill Edge's servant, who had been with Tommy: he told me that Bill Edge had been hit, had gone off with Bill Aird to get his wound dressed, and told him to stay by his pack. By this time all was quiet, except for one light machine-gun firing at us from the south-eastern end of the paddy; but its fire soon ceased, and somebody found the gunner dead by his gun half an hour later.

To read more about the ambush at Kyaik-in, please click on the following link: Lieutenant John Kerr and the Fighting Men of Kyaik-in

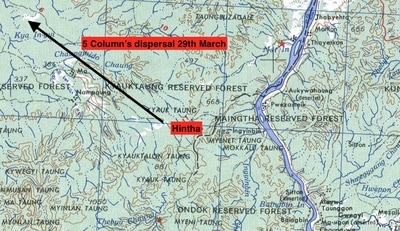

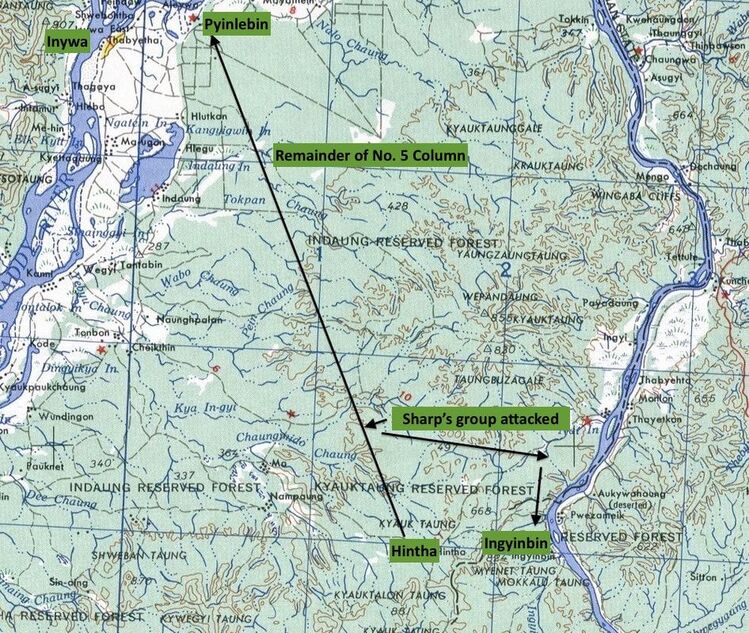

After completing the demolition of the railway line and gorge at Bonchaung, 5 Column pushed further east towards the Irrawaddy River, crossing at a place named Tigyaing. At this time Pte. Fitzpatrick would have still been with Captain Roberts' unit and would have continued to tend his commander's horse. Just a few weeks later, on the 28th March, 5 Column were engaged in a fierce battle with the enemy at a village called Hintha. After the withdrawal from Hintha, the column were again ambushed by the Japanese as they marched northeast in an attempt to join up with the rest of 77 Brigade. It was at this juncture that Pte. Fitzpatrick became separated from the main body of the column and his commanding officer, Tommy Roberts.

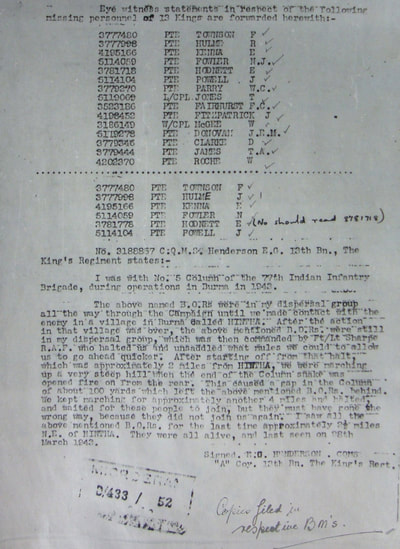

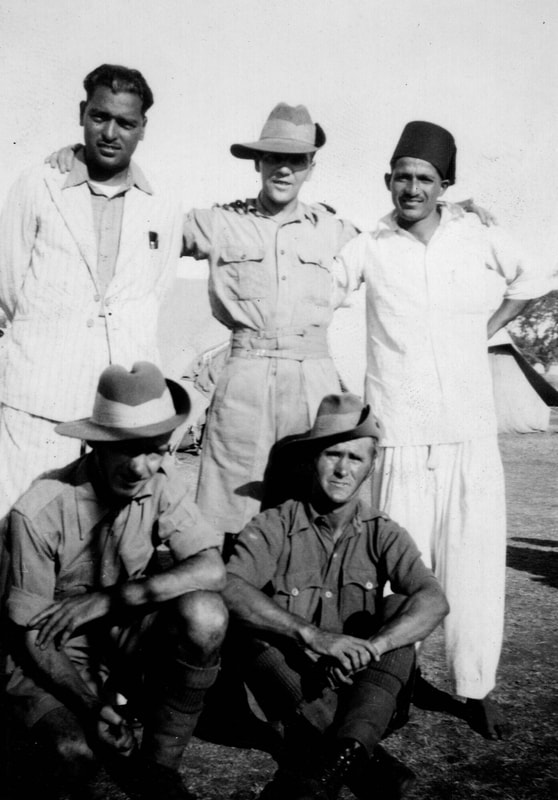

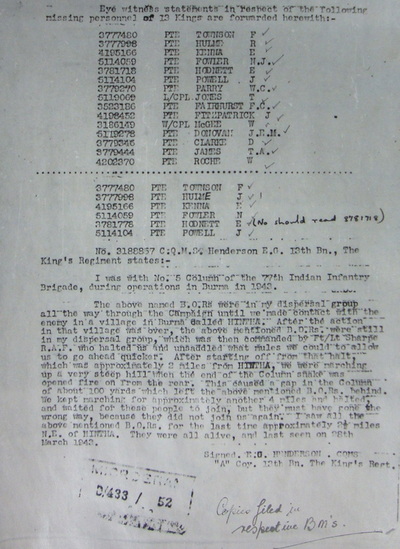

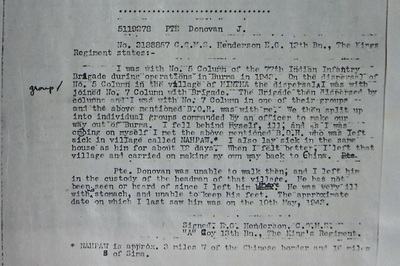

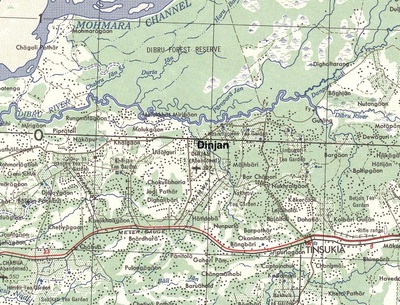

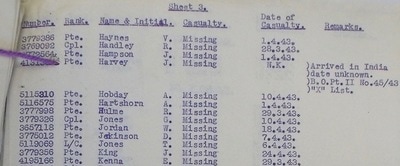

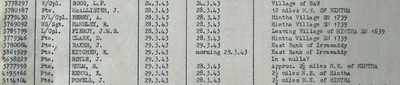

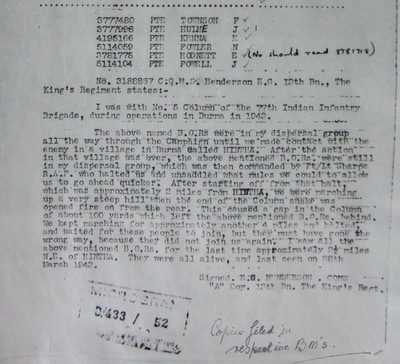

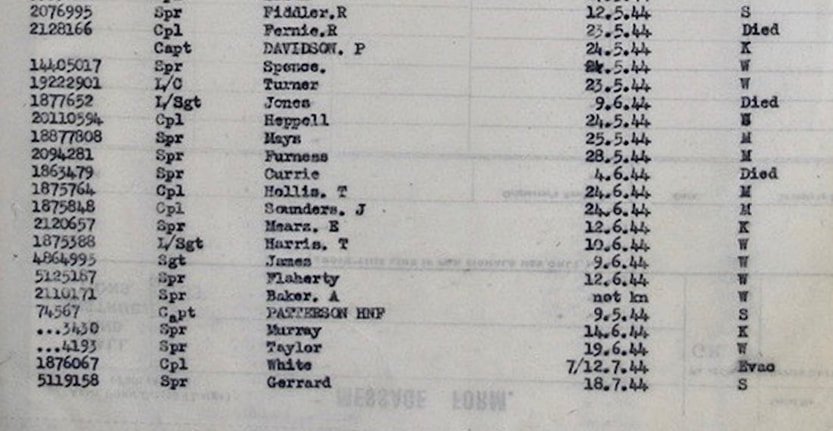

Quartermaster Sergeant Ernest Henderson described this incident in a witness statement given in February 1944, as part of the investigation into the fate of those missing from the first Wingate expedition. He stated that a group of some twenty soldiers including Pte. Fitzpatrick were part of his dispersal party after the battle at Hintha:

I was with No. 5 Column of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, during operations in Burma in 1943. The above named British Other Ranks were in my dispersal group all the way through the campaign until we made contact with the enemy in a village called Hintha. After the action in that village was over, the above mentioned BOR's were still in my dispersal group, which was commanded by Flight Lieutenant Sharp RAF, who halted us and unsaddled what mules we could to allow us to go ahead quicker. After starting off from that halt which was approximately 2 miles from Hintha, we were marching up a steep hill, when the end of the column snake was opened fire on from the rear. This caused a gap in the Column of about 100 yards which left the above mentioned BOR's behind. We kept marching for another 4 miles and halted and waited for these people to re-join, but they must have gone the wrong way, because they did not join us again. I saw all the above mentioned for last time approximately two and a half miles N.E. of Hintha. They were all alive, and last seen on the 28th March.

To read more about 5 Column's engagement with the Japanese at Hintha, please click on the following link: Pte. John Henry Cobb

Shown below is a gallery of images in relation to this story including the witness statement made by CQMS Henderson. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Rank: Private

Service No: 4198452

Date of Death: 21/10/1944

Age: 24

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Grave Reference 5. D. 1. Rangoon War Cemetery.

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2259957/fitzpatrick,-joseph/

Chindit Column: 5

Other details:

Joseph Fitzpatrick was born on the 27th October 1919 and was the son of Stephen and Alice Fitzpatrick from Appley Bridge in Lancashire. In the years before WW2, Joseph worked both as a waiter in the catering industry and as a doorman for a large Liverpool Hotel. He enlisted into the Army and was originally posted to the Royal Welch Fusiliers, with the Army No. 4198452. Later, whilst in India, Pte. Fitzpatrick was transferred to the 13th Battalion of the King's Liverpool Regiment and was allocated to Chindit Column No. 5 at their training camp located in the jungle scrubland close to the town of Saugor in the Central Provinces of the country.

During his time in Burma on Operation Longcloth, Joseph took on the role of groom to Captain Tommy Roberts who commanded the Support Platoon within 5 Column. Apart from the obvious duties in looking after Captain Roberts' horse, Pte. Fitzpatrick was also used as a runner in Burma, delivering messages to Major Fergusson and the other officers from 5 Column. Bernard Fergusson mentions one such occasion in his book, Beyond the Chindwin, when the column were marching towards Bonchaung in early March 1943 and suffered an ambush by a Japanese patrol at a village called Kyaik-in:

On the morning of the 6th of March, everybody got off to time; but before I had marched four hundred yards along the road, Fitzpatrick, Tommy Roberts' groom, came up at a gallop, somewhat flustered. He had been up and down the road for fifteen minutes, unable to spot the point in the jungle where our bivouac had been. (I never bivouacked within five hundred yards of a track).

Tommy was engaged in Kyaik-in village with some Japanese; he had sent Jim Harman back and round to go straight for the gorge, and was fighting it out himself. I asked Fitzpatrick (in civil life a buttons in a Liverpool hotel) for details, but all he knew was that there was a lot of shooting going on, and a lot of bangs, and Tommy had sent him back to warn me. I hastily decided to send the main body straight off across country to Bonchaung. I sent the remaining rifle platoon, now commanded by Gerry Roberts, down the motor-road to the village as fast as it could go, to back up Tommy, while I gave Alec and Duncan their orders. When I had finished, I took Peter Dorans, and followed Gerry.

As I drew near the village, I could hear light machine-guns in action, and the occasional burst of a grenade. The jungle was continuous on the right of the road, but there was a small strip of disused paddy, with some scrubby bushes, on the left; and by the time I arrived (for it took a minute or two to give out the orders to the main body) Gerry's leading Bren section was already in position, and had fired on a small party of Japs.

Obsessed with the importance of avoiding a fight with our own troops, I begged him to be careful, and to work gradually along the track. I saw two men of the original party in the bushes on the right, one of whom was Bill Edge's servant, who had been with Tommy: he told me that Bill Edge had been hit, had gone off with Bill Aird to get his wound dressed, and told him to stay by his pack. By this time all was quiet, except for one light machine-gun firing at us from the south-eastern end of the paddy; but its fire soon ceased, and somebody found the gunner dead by his gun half an hour later.

To read more about the ambush at Kyaik-in, please click on the following link: Lieutenant John Kerr and the Fighting Men of Kyaik-in

After completing the demolition of the railway line and gorge at Bonchaung, 5 Column pushed further east towards the Irrawaddy River, crossing at a place named Tigyaing. At this time Pte. Fitzpatrick would have still been with Captain Roberts' unit and would have continued to tend his commander's horse. Just a few weeks later, on the 28th March, 5 Column were engaged in a fierce battle with the enemy at a village called Hintha. After the withdrawal from Hintha, the column were again ambushed by the Japanese as they marched northeast in an attempt to join up with the rest of 77 Brigade. It was at this juncture that Pte. Fitzpatrick became separated from the main body of the column and his commanding officer, Tommy Roberts.

Quartermaster Sergeant Ernest Henderson described this incident in a witness statement given in February 1944, as part of the investigation into the fate of those missing from the first Wingate expedition. He stated that a group of some twenty soldiers including Pte. Fitzpatrick were part of his dispersal party after the battle at Hintha:

I was with No. 5 Column of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, during operations in Burma in 1943. The above named British Other Ranks were in my dispersal group all the way through the campaign until we made contact with the enemy in a village called Hintha. After the action in that village was over, the above mentioned BOR's were still in my dispersal group, which was commanded by Flight Lieutenant Sharp RAF, who halted us and unsaddled what mules we could to allow us to go ahead quicker. After starting off from that halt which was approximately 2 miles from Hintha, we were marching up a steep hill, when the end of the column snake was opened fire on from the rear. This caused a gap in the Column of about 100 yards which left the above mentioned BOR's behind. We kept marching for another 4 miles and halted and waited for these people to re-join, but they must have gone the wrong way, because they did not join us again. I saw all the above mentioned for last time approximately two and a half miles N.E. of Hintha. They were all alive, and last seen on the 28th March.

To read more about 5 Column's engagement with the Japanese at Hintha, please click on the following link: Pte. John Henry Cobb

Shown below is a gallery of images in relation to this story including the witness statement made by CQMS Henderson. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

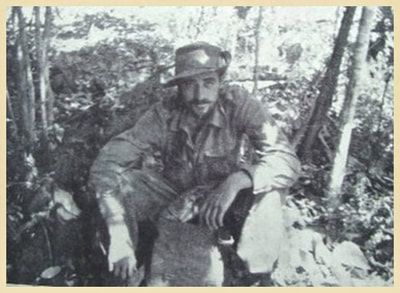

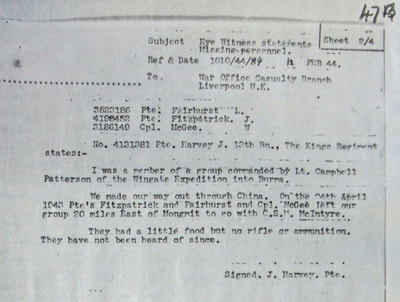

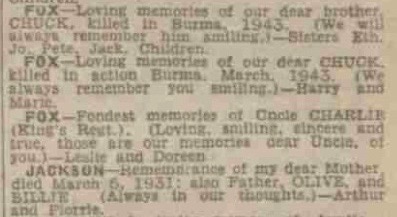

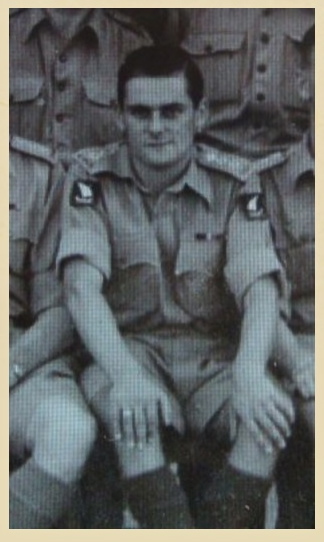

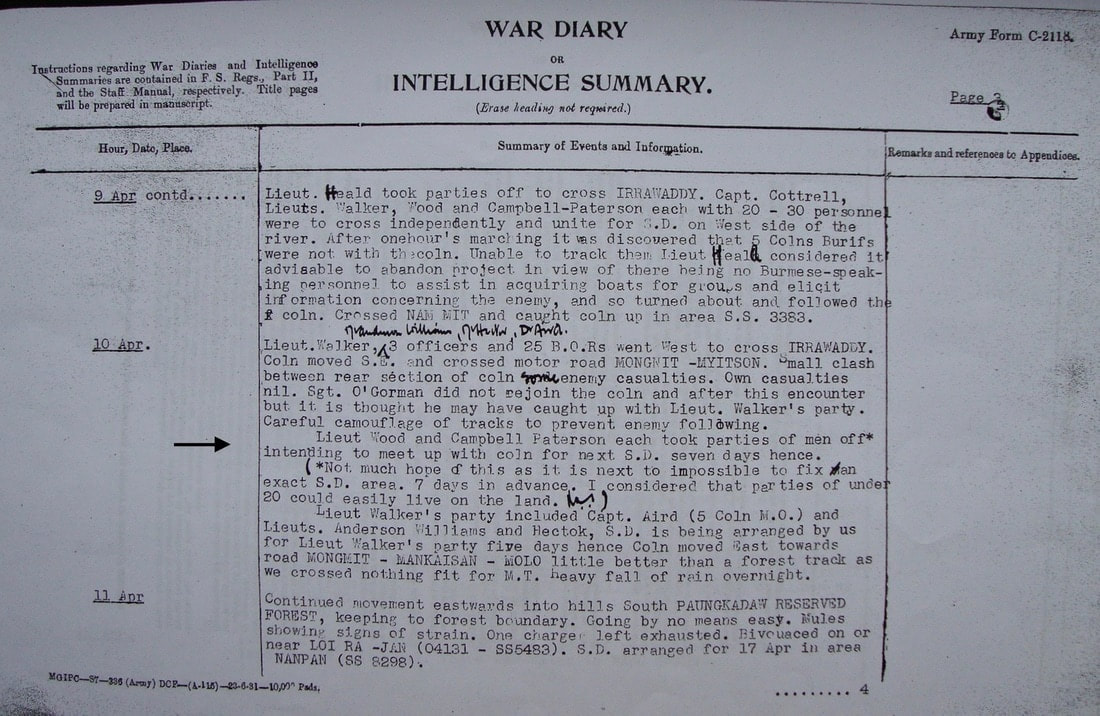

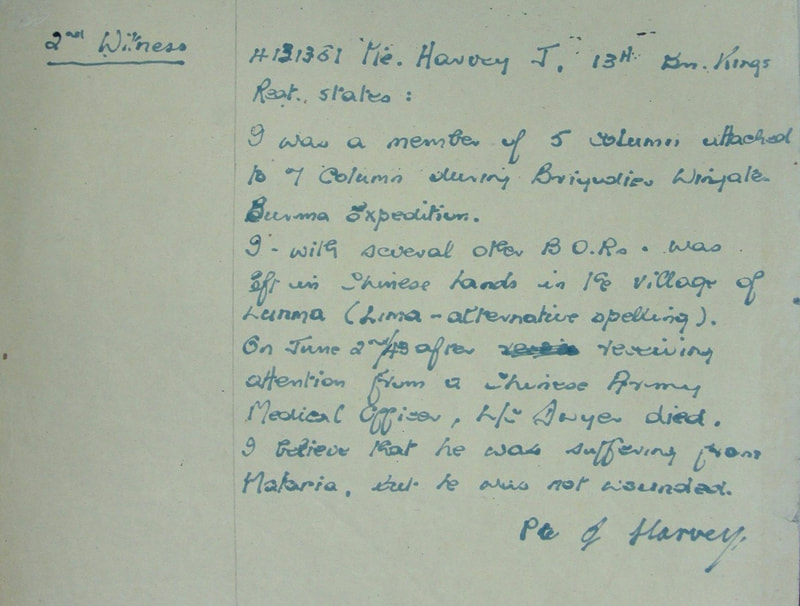

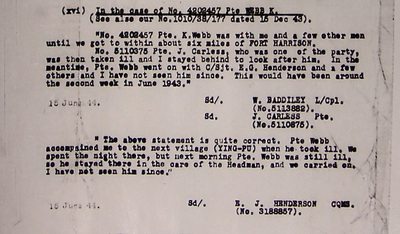

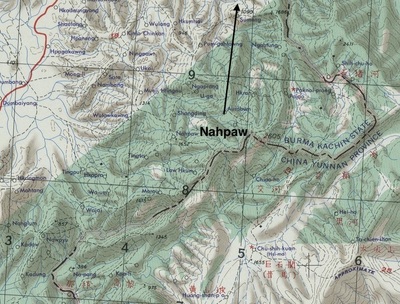

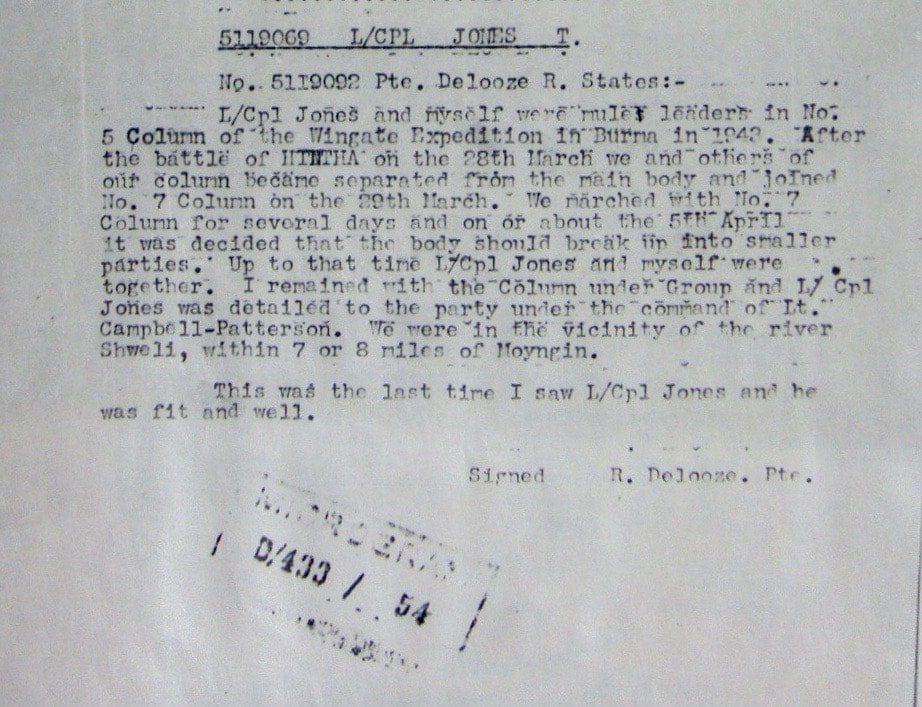

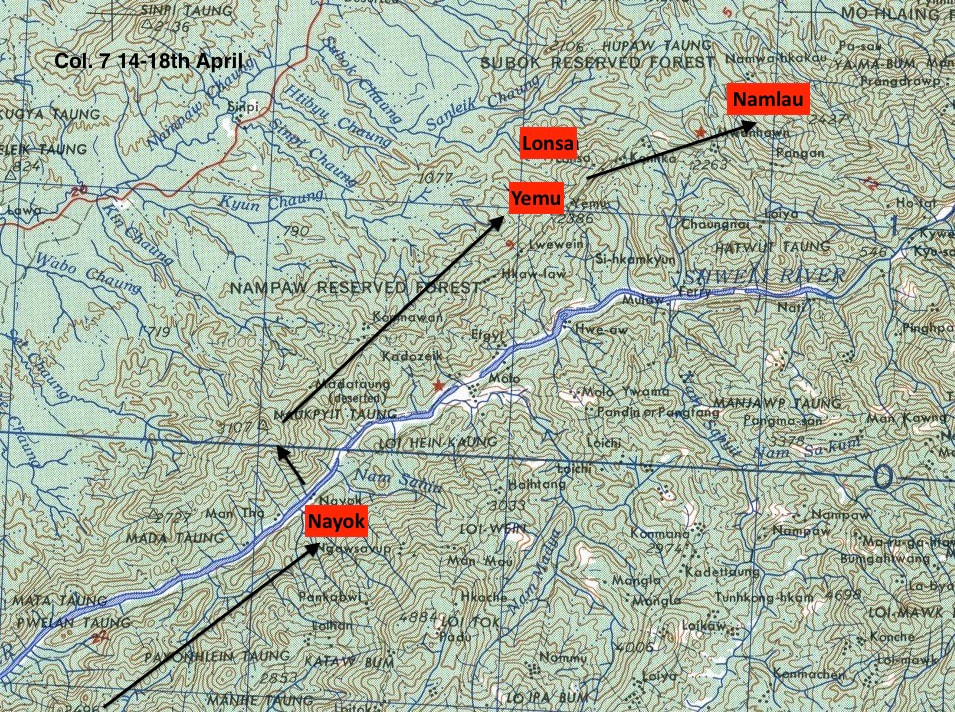

One hundred men from 5 Column were separated at the second ambush on the outskirts of Hintha and the majority of these were fortunate to bump into 7 Column three days later, as Major Gilkes' men prepared to cross the Shweli River. Major Gilkes took the stragglers from 5 Column under his wing. He allocated these men into his already pre-arranged dispersal groups and the men headed towards the Yunnan Borders of China in order to exit Burma. Joseph Fitzpatrick was allocated to the group led by Lieutenant Campbell-Paterson formerly of the Royal Scots.

After successfully crossing the fast flowing Shweli River on the 14th April near the Burmese village of Nayok, Campbell-Paterson's group were caught for a period in an area of hills which were being heavily patrolled by the Japanese. Having made little progress for the best part of a week, some of the British NCO's lost confidence in the original plan to exit Burma via the Yunnan Borders and asked if they might be allowed to break away from the dispersal group and return westwards to India.

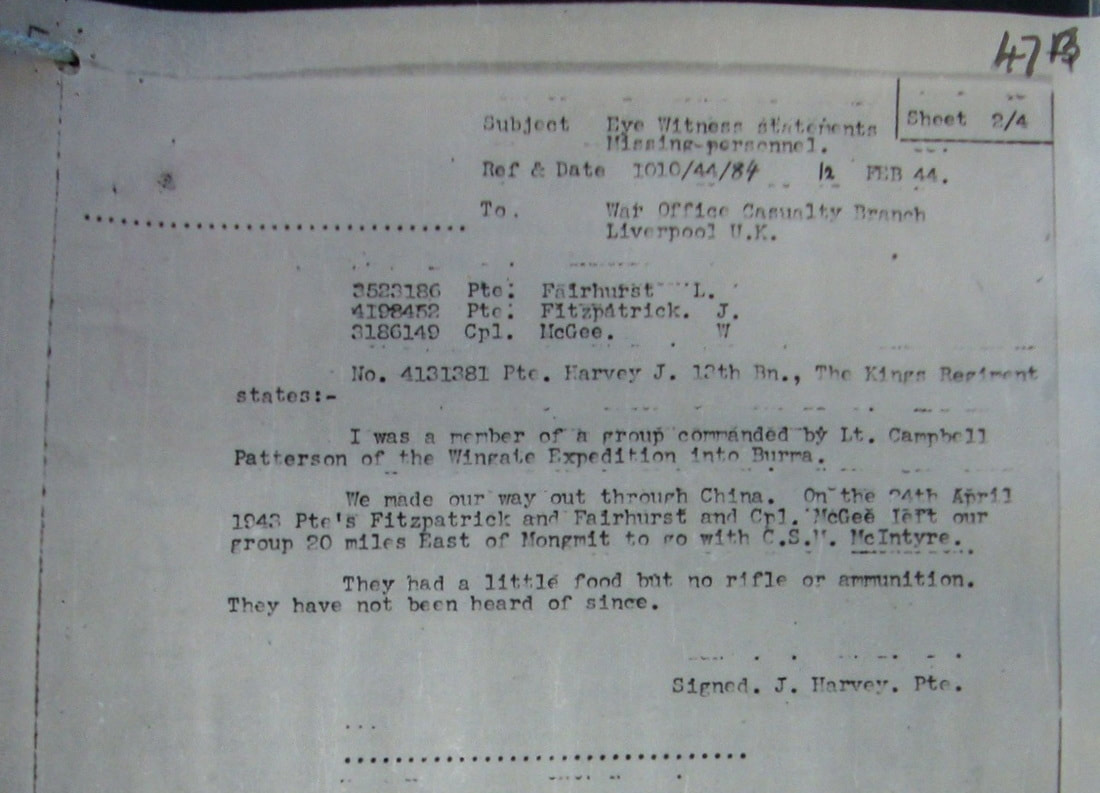

A witness statement report given after the operation by a Pte. J. Harvey (shown in the above gallery), explains how four men led by CSM Robert McIntyre chose this option and separated from Lieutenant Campbell-Paterson's group in late April 1943. Pte. J. Harvey's short report confirms CSM McIntyre and three other men, Joseph Fitzpatrick, Corporal William McGee and Francis Fairhurst (all former members of 5 Column) decided to leave the dispersal party when the group were in the vicinity of Mong Mit.

On several occasions after 7 Column's dispersal from the banks of the Shweli River; small splinter groups were formed, often led by British NCO's who respectfully disagreed with the order to march north-east towards and exit Burma via the Chinese borders. In my experience this was mainly due to the lack of British rations available to the men at that time and their dislike of surviving on a diet of rice obtained from local villages en route. Pte. Harvey states that McIntyre's party were last seen on the 24th April and that they had a little food with them, but no weapons. Over the next few days, Robert McIntyre and all the members of his break-away party were captured by the Japanese. To read more about CSM McIntyre and the other men with him, please click on the following link and scroll down alphabetically on the page: Roll Call K-O

After successfully crossing the fast flowing Shweli River on the 14th April near the Burmese village of Nayok, Campbell-Paterson's group were caught for a period in an area of hills which were being heavily patrolled by the Japanese. Having made little progress for the best part of a week, some of the British NCO's lost confidence in the original plan to exit Burma via the Yunnan Borders and asked if they might be allowed to break away from the dispersal group and return westwards to India.

A witness statement report given after the operation by a Pte. J. Harvey (shown in the above gallery), explains how four men led by CSM Robert McIntyre chose this option and separated from Lieutenant Campbell-Paterson's group in late April 1943. Pte. J. Harvey's short report confirms CSM McIntyre and three other men, Joseph Fitzpatrick, Corporal William McGee and Francis Fairhurst (all former members of 5 Column) decided to leave the dispersal party when the group were in the vicinity of Mong Mit.

On several occasions after 7 Column's dispersal from the banks of the Shweli River; small splinter groups were formed, often led by British NCO's who respectfully disagreed with the order to march north-east towards and exit Burma via the Chinese borders. In my experience this was mainly due to the lack of British rations available to the men at that time and their dislike of surviving on a diet of rice obtained from local villages en route. Pte. Harvey states that McIntyre's party were last seen on the 24th April and that they had a little food with them, but no weapons. Over the next few days, Robert McIntyre and all the members of his break-away party were captured by the Japanese. To read more about CSM McIntyre and the other men with him, please click on the following link and scroll down alphabetically on the page: Roll Call K-O

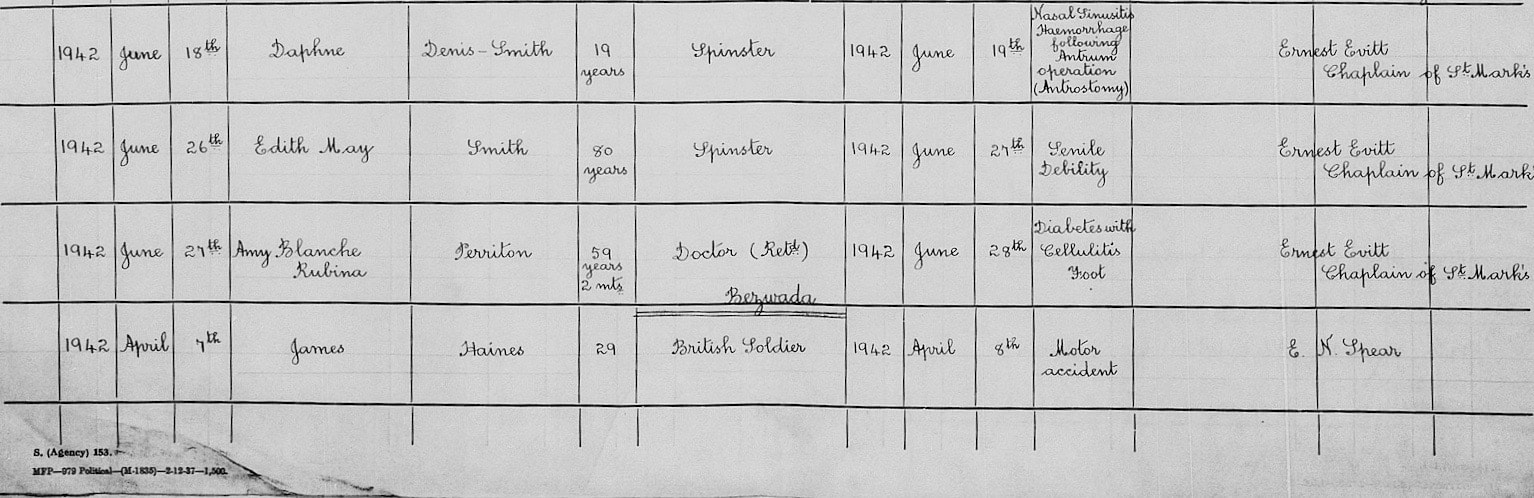

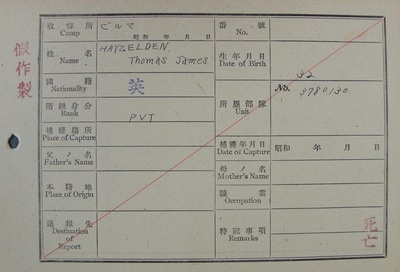

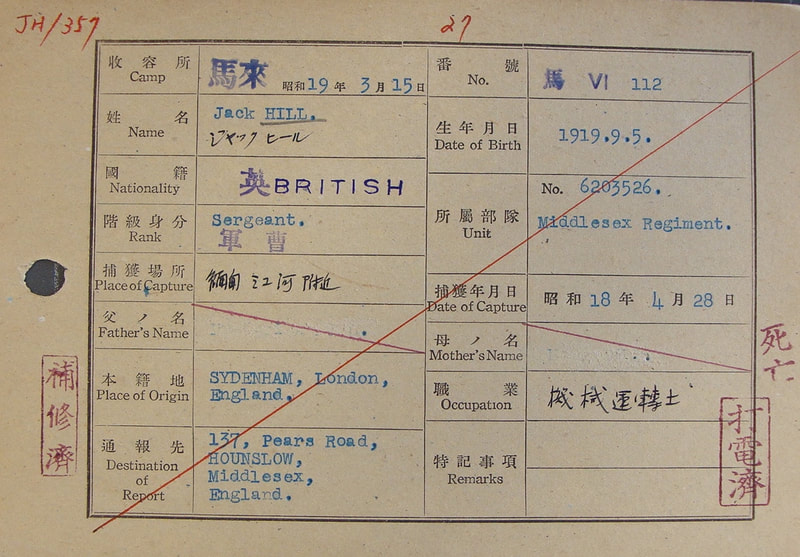

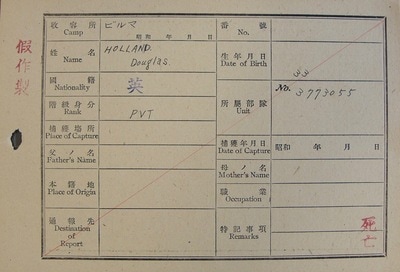

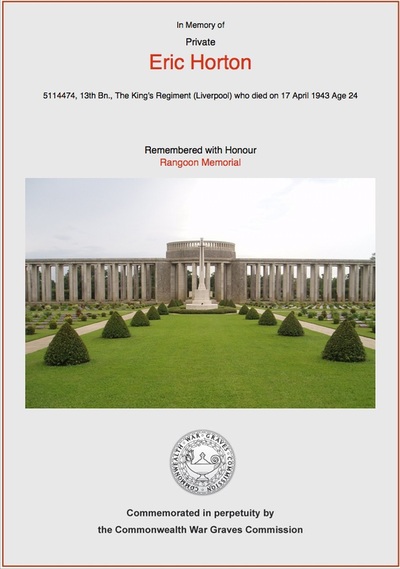

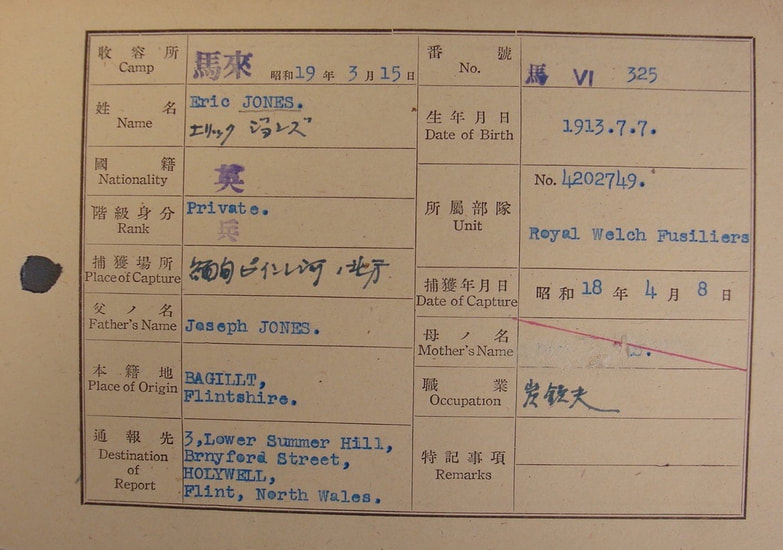

Joseph Fitzpatrick was captured on the 26th April 1943 and according to his POW index card the location of capture was somewhere east of the Chindwin River. I believe that this description of the location, is simply a statement implying that he had not managed to reach the river which formed the unofficial boundary between Burma on the east and Assam on the west and proved to be such an insurmountable barrier to many a Chindit in 1943. Joseph spent 18 months as a prisoner of war inside Block 6 of Rangoon Jail, where he was allocated the POW number of 307.

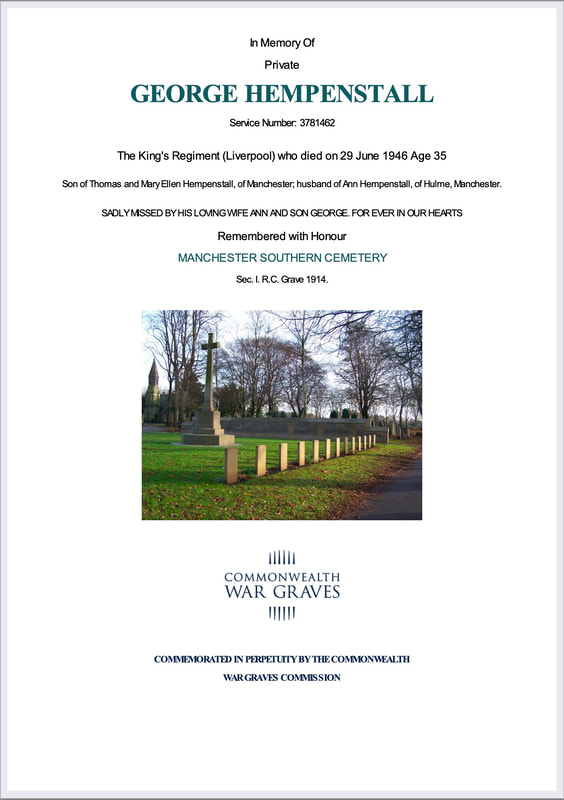

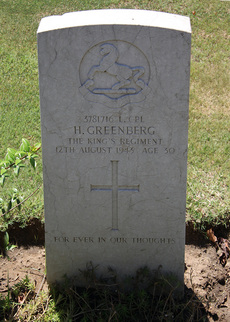

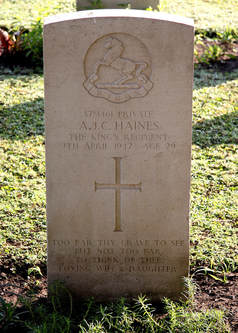

Sadly, Joseph Fitzpatrick died on the 21st October 1944, suffering from the ravages of exhaustion, malnutrition and beri beri. His POW card states that he had become ill around mid-August and that his official cause of death was the disease beri beri. He was buried in the first instance at the English Cantonment Cemetery located in the eastern sector of the city, close to the Royal Lakes. In June 1946, Joseph's remains, along with the other Chindit burials at the Cantonment Cemetery were re-interred at the newly constructed Rangoon War Cemetery which is situated close to the dockland area of the city.

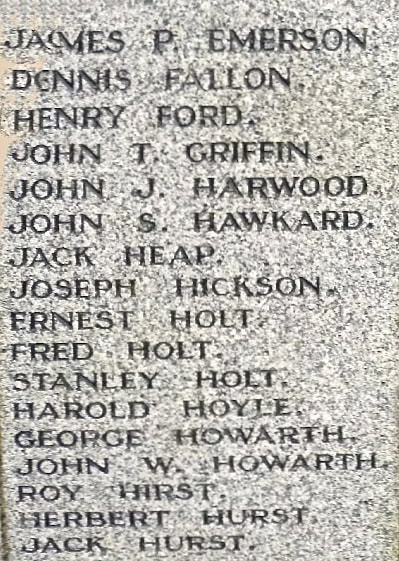

In his home county of Lancashire, Joseph is remembered upon both the Appley Bridge and Shevington War Memorials. For his epitaph back at Rangoon War Cemetery, his family chose the following rhyming couplet to be placed onto his grave plaque:

Sadly, Joseph Fitzpatrick died on the 21st October 1944, suffering from the ravages of exhaustion, malnutrition and beri beri. His POW card states that he had become ill around mid-August and that his official cause of death was the disease beri beri. He was buried in the first instance at the English Cantonment Cemetery located in the eastern sector of the city, close to the Royal Lakes. In June 1946, Joseph's remains, along with the other Chindit burials at the Cantonment Cemetery were re-interred at the newly constructed Rangoon War Cemetery which is situated close to the dockland area of the city.

In his home county of Lancashire, Joseph is remembered upon both the Appley Bridge and Shevington War Memorials. For his epitaph back at Rangoon War Cemetery, his family chose the following rhyming couplet to be placed onto his grave plaque:

Whoever stops by this soldier's grave

Please say a prayer, he was so brave.

Please say a prayer, he was so brave.

Seen below is a final gallery of images in relation to this story, including Joseph's memorial plaque at Rangoon War Cemetery and his inscription upon the Shevington War Memorial. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Cap badge of the RAF.

Cap badge of the RAF.

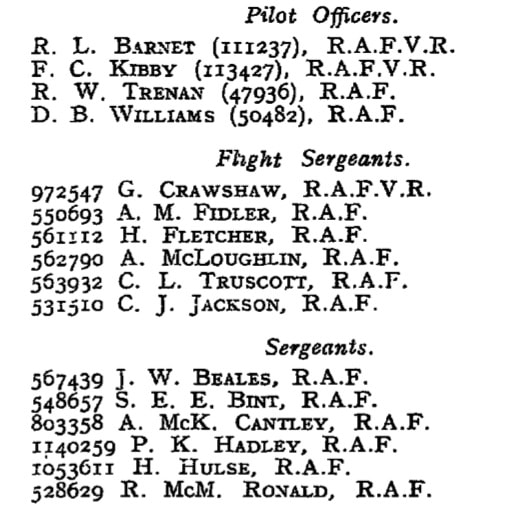

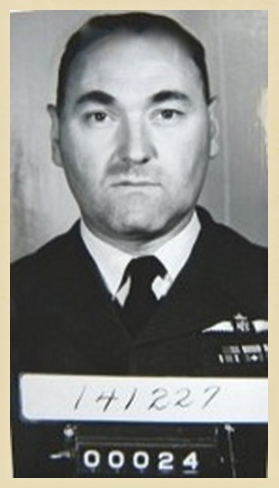

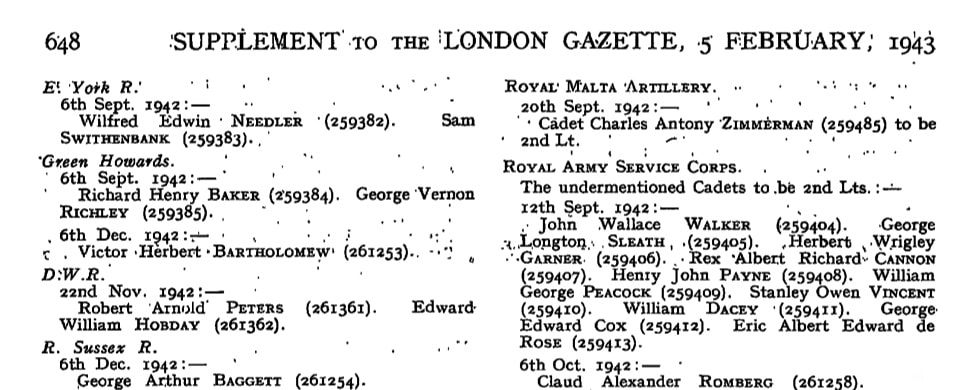

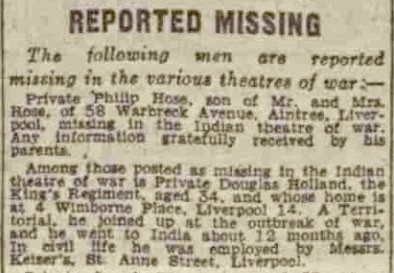

FLETCHER H.

Rank: Flight Sergeant

Service No: 561112

Age: Unknown

Regiment/Service: RAF attached 77 Indian Infantry Brigade.

Chindit Column: 3

Other details:

In March 2008, my family and I travelled to Burma to visit some of the places frequented by the Chindits during WW2. On this trip was a Burma veteran named Denis Gudgeon who was full of stories and anecdotes about his involvement on Operation Longcloth in 1943. One of these accounts, given by the poolside bar at the Mandalay Hill Hotel, mentioned a RAF Sergeant named Fletcher, who was part of the RAF Liaison section in No. 3 Column that year. I have never been able to find out any more information about Sergeant Fletcher, other than he was awarded a Mentioned in Despatches for his services in Burma, as gazetted on the 16th December 1943.

The RAF Liaison team for No. 3 Column was commanded by Flight Lieutenant Robert Thompson who was awarded the Military Cross for his efforts on Operation Longcloth. Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story including the entry in the London Gazette recording Fletcher's MID. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Rank: Flight Sergeant

Service No: 561112

Age: Unknown

Regiment/Service: RAF attached 77 Indian Infantry Brigade.

Chindit Column: 3

Other details:

In March 2008, my family and I travelled to Burma to visit some of the places frequented by the Chindits during WW2. On this trip was a Burma veteran named Denis Gudgeon who was full of stories and anecdotes about his involvement on Operation Longcloth in 1943. One of these accounts, given by the poolside bar at the Mandalay Hill Hotel, mentioned a RAF Sergeant named Fletcher, who was part of the RAF Liaison section in No. 3 Column that year. I have never been able to find out any more information about Sergeant Fletcher, other than he was awarded a Mentioned in Despatches for his services in Burma, as gazetted on the 16th December 1943.

The RAF Liaison team for No. 3 Column was commanded by Flight Lieutenant Robert Thompson who was awarded the Military Cross for his efforts on Operation Longcloth. Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story including the entry in the London Gazette recording Fletcher's MID. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

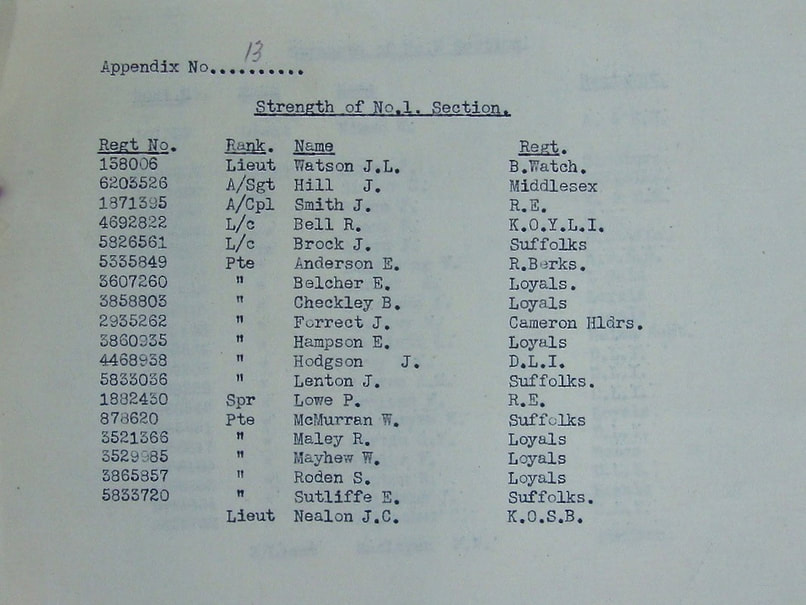

FORREST J.

Rank: Private

Service No: 2935262

Age: Unknown

Regiment/Service: 142 Commando attached 13th Battalion The King's (Liverpool) Regiment.

Chindit Column: 1

Other details:

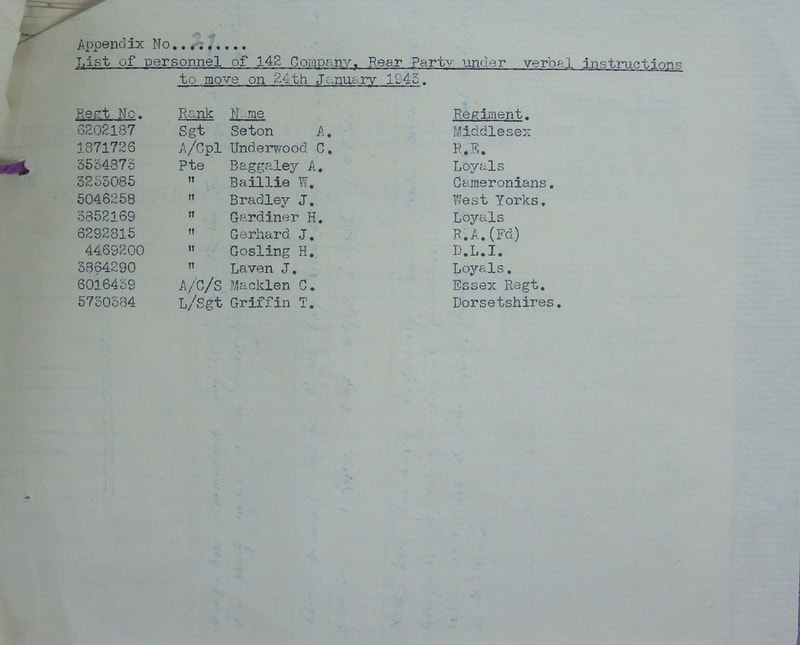

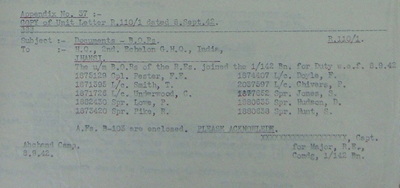

Pte. Forrest joined 142 Commando at their training camp at Saugor on the 25th September 1942, having previously served with the Cameron Highlanders earlier in the war. He was allocated to the Commando section for No. 1 Column under the command of Lt. J.L. Watson formerly of the Black Watch. No. 1 Column were predominately a Gurkha Rifles unit on Operation Longcloth, with the Commando Platoon providing some of the British element alongside the Signals and RAF Liaison sections. To read more about the Commandos of No. 1 Column, please click on the following link: Pte. Ernest Belcher

Rank: Private

Service No: 2935262

Age: Unknown

Regiment/Service: 142 Commando attached 13th Battalion The King's (Liverpool) Regiment.

Chindit Column: 1

Other details:

Pte. Forrest joined 142 Commando at their training camp at Saugor on the 25th September 1942, having previously served with the Cameron Highlanders earlier in the war. He was allocated to the Commando section for No. 1 Column under the command of Lt. J.L. Watson formerly of the Black Watch. No. 1 Column were predominately a Gurkha Rifles unit on Operation Longcloth, with the Commando Platoon providing some of the British element alongside the Signals and RAF Liaison sections. To read more about the Commandos of No. 1 Column, please click on the following link: Pte. Ernest Belcher

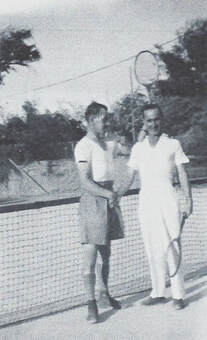

FOULDS, GORDON GEORGE

Rank: Lieutenant

Service No: 153118

Age: Not known

Regiment/Service: 13th Battalion, the King's (Liverpool) Regiment.

Chindit Column: 5

Other details:

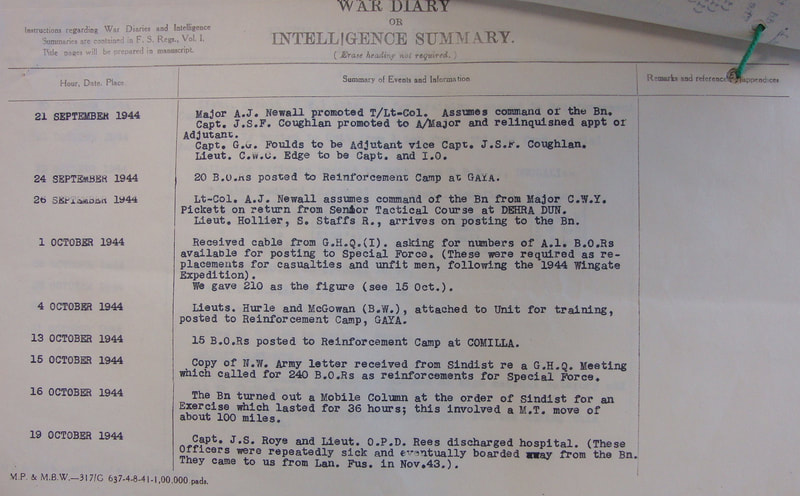

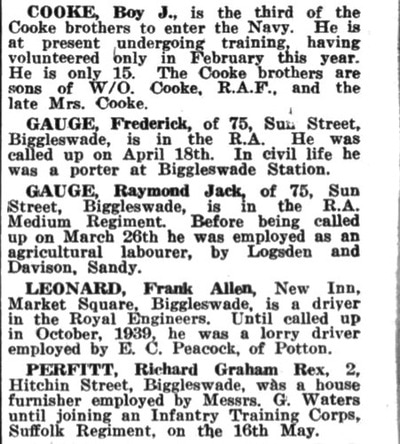

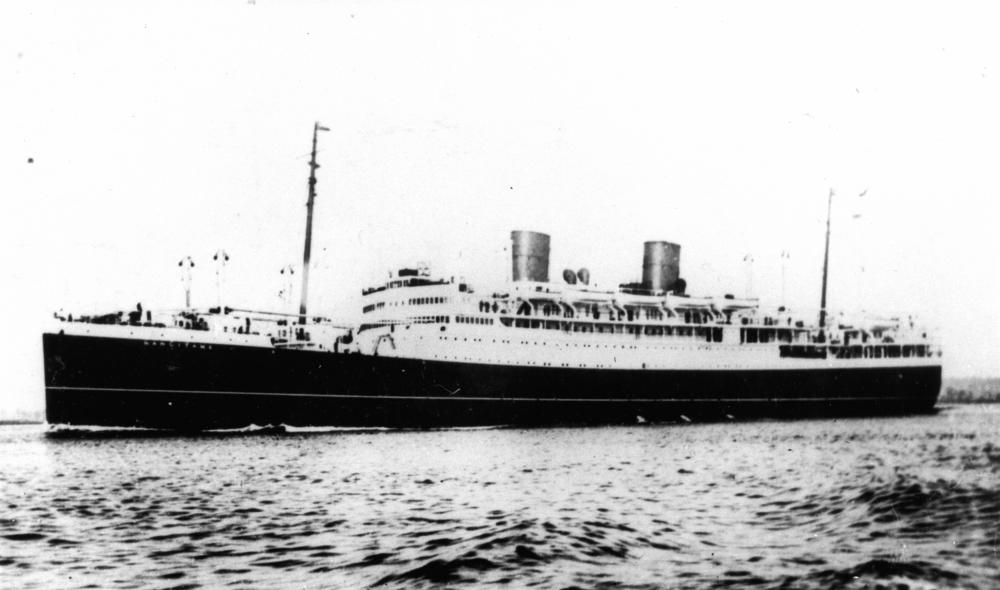

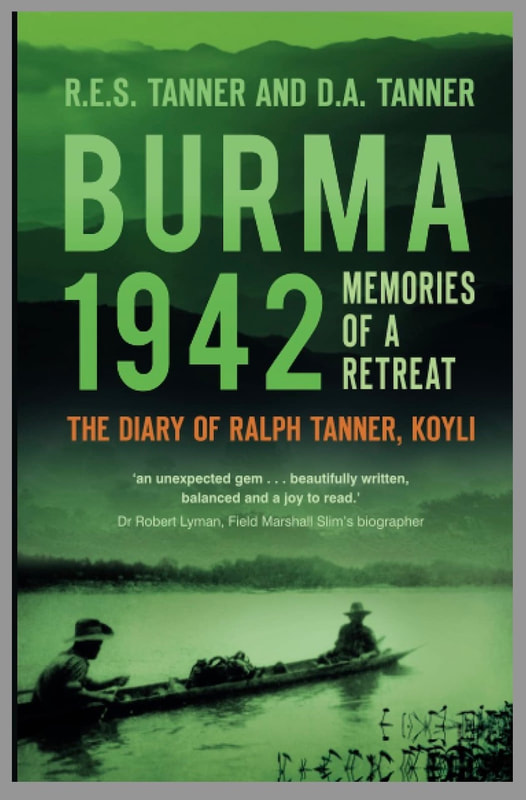

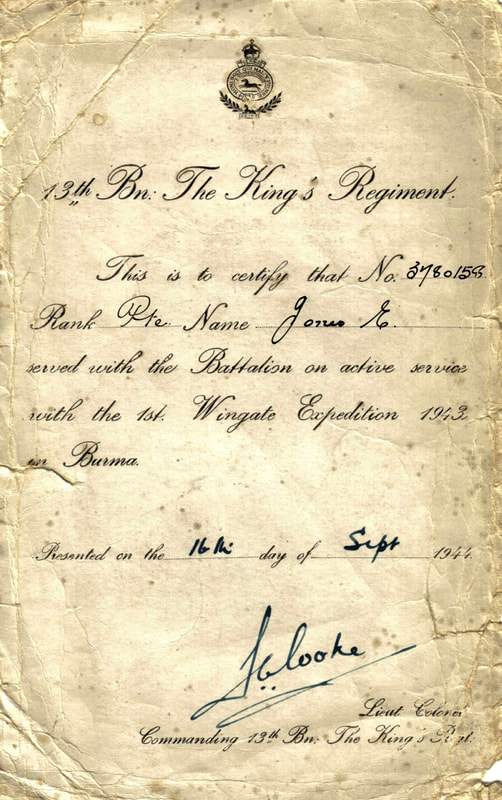

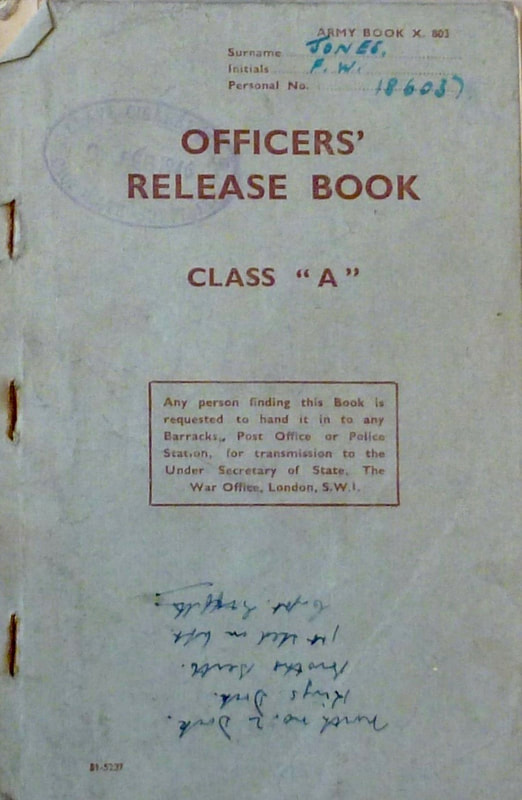

Gordon Foulds was posted to the 13th King's in October 1940 whilst the battalion had been performing coastal defence duties at Felixstowe in Suffolk. Just over one year later, he was part of the battalion as it prepared to voyage overseas to India aboard the troopship Oronsay on the 8th December 1941. It is known that Lt. Foulds was part of the leadership structure for No. 5 Column during the training period at Patharia and Saugor, but it is not known whether he actually took part on Operation Longcloth itself.

Lt. Foulds' involvement during Chindit training was mentioned in the book, Return via Rangoon, by Philip Stibbe. The transcription below is in relation to an incident where the whole training regime had been severely effected by the unexpected arrival of the monsoon season in the Central Provinces of India:

Gordon Foulds, who was temporarily attached to our column, was in charge of our little party as we squelched our way forward rather hopefully, but whichever direction we went in, after about half a mile we found we were faced with raging flood waters. It was rapidly getting dark and we began to think we must be on an island with the floods rising all around us. One of the officers was washed away trying to cross the stream, but he managed to seize an overhanging branch and drag himself to the bank.

When night fell we found that our torches would not work properly owing to the damp and Gordon decided that the only thing to do was to stay where we were and hope that the water would not rise to our level before morning. We had all taken off our clothes as usual when it first started to rain, but it had been impossible to keep them dry. We had nothing to eat, we were soaked to the marrow, and it was now extremely cold. We could not make a fire as there was nothing dry to burn, so we huddled together under the scanty leaves of a tree and prepared for a sleepless night. Somebody jokingly remarked that at any rate we were not suffering from thirst.

Gordon and I spent the night clinging together for warmth under a sopping blanket. We derived a certain amount of amusement from recalling how as children at home we used to be popped into a hot mustard bath if we came home with wet feet. At first light we moved off stiff and tired and hungry. It had stopped raining and the floods were beginning to subside as rapidly as they had risen, so that we did not have much difficulty in reaching the camp and safety.

As mentioned earlier, it is not known if Gordon Foulds actually took part on the the first Wingate expedition into Burma in 1943. It is likely that he had taken a more administrative role in the battalion and became part of the Rear Base set up at Saugor and then Agartala. He remained with the battalion through 1944, becoming the battalion Adjutant for a period on the 21st September whilst the King's were stationed at Karachi. Previous to this he had been D Company commander at the Napier Barracks in Karachi. On the 22nd March 1945, Gordon Foulds, now holding the rank of Major was transferred from the 13th King's to the Base Reinforcement Camp at Comilla in readiness for an active service posting.

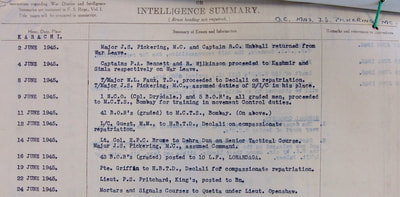

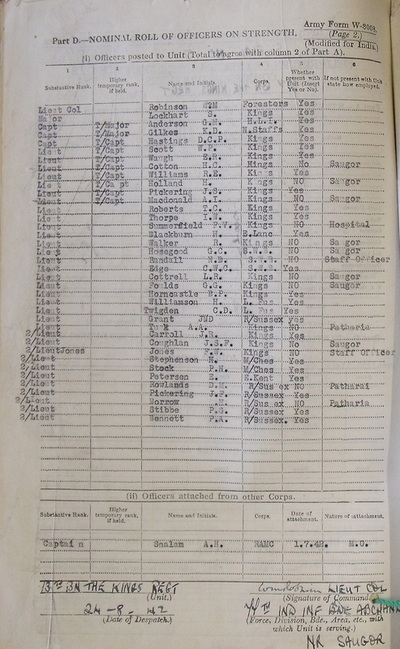

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including the war diary extract describing Gordon Foulds' promotion to battalion Adjutant in September 1944. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Rank: Lieutenant

Service No: 153118

Age: Not known

Regiment/Service: 13th Battalion, the King's (Liverpool) Regiment.

Chindit Column: 5

Other details:

Gordon Foulds was posted to the 13th King's in October 1940 whilst the battalion had been performing coastal defence duties at Felixstowe in Suffolk. Just over one year later, he was part of the battalion as it prepared to voyage overseas to India aboard the troopship Oronsay on the 8th December 1941. It is known that Lt. Foulds was part of the leadership structure for No. 5 Column during the training period at Patharia and Saugor, but it is not known whether he actually took part on Operation Longcloth itself.

Lt. Foulds' involvement during Chindit training was mentioned in the book, Return via Rangoon, by Philip Stibbe. The transcription below is in relation to an incident where the whole training regime had been severely effected by the unexpected arrival of the monsoon season in the Central Provinces of India:

Gordon Foulds, who was temporarily attached to our column, was in charge of our little party as we squelched our way forward rather hopefully, but whichever direction we went in, after about half a mile we found we were faced with raging flood waters. It was rapidly getting dark and we began to think we must be on an island with the floods rising all around us. One of the officers was washed away trying to cross the stream, but he managed to seize an overhanging branch and drag himself to the bank.

When night fell we found that our torches would not work properly owing to the damp and Gordon decided that the only thing to do was to stay where we were and hope that the water would not rise to our level before morning. We had all taken off our clothes as usual when it first started to rain, but it had been impossible to keep them dry. We had nothing to eat, we were soaked to the marrow, and it was now extremely cold. We could not make a fire as there was nothing dry to burn, so we huddled together under the scanty leaves of a tree and prepared for a sleepless night. Somebody jokingly remarked that at any rate we were not suffering from thirst.

Gordon and I spent the night clinging together for warmth under a sopping blanket. We derived a certain amount of amusement from recalling how as children at home we used to be popped into a hot mustard bath if we came home with wet feet. At first light we moved off stiff and tired and hungry. It had stopped raining and the floods were beginning to subside as rapidly as they had risen, so that we did not have much difficulty in reaching the camp and safety.

As mentioned earlier, it is not known if Gordon Foulds actually took part on the the first Wingate expedition into Burma in 1943. It is likely that he had taken a more administrative role in the battalion and became part of the Rear Base set up at Saugor and then Agartala. He remained with the battalion through 1944, becoming the battalion Adjutant for a period on the 21st September whilst the King's were stationed at Karachi. Previous to this he had been D Company commander at the Napier Barracks in Karachi. On the 22nd March 1945, Gordon Foulds, now holding the rank of Major was transferred from the 13th King's to the Base Reinforcement Camp at Comilla in readiness for an active service posting.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including the war diary extract describing Gordon Foulds' promotion to battalion Adjutant in September 1944. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Cap badge of the King's Own Shropshire Light Infantry.

Cap badge of the King's Own Shropshire Light Infantry.

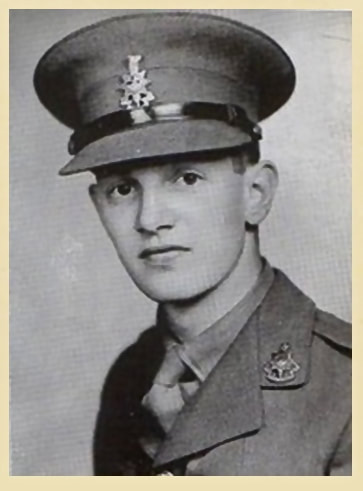

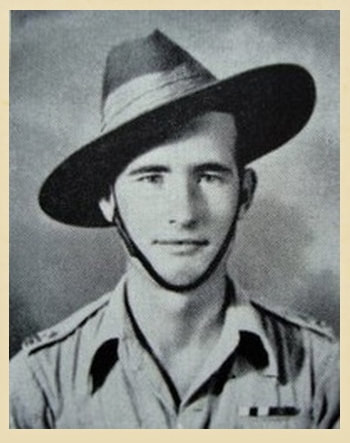

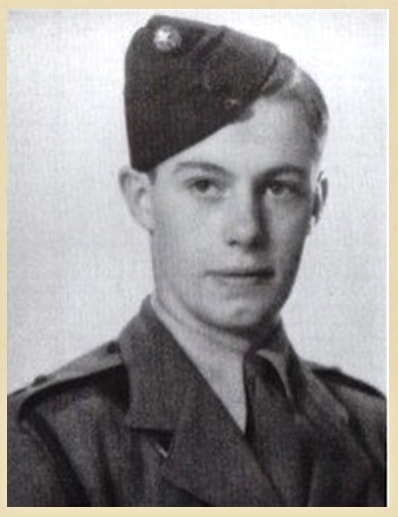

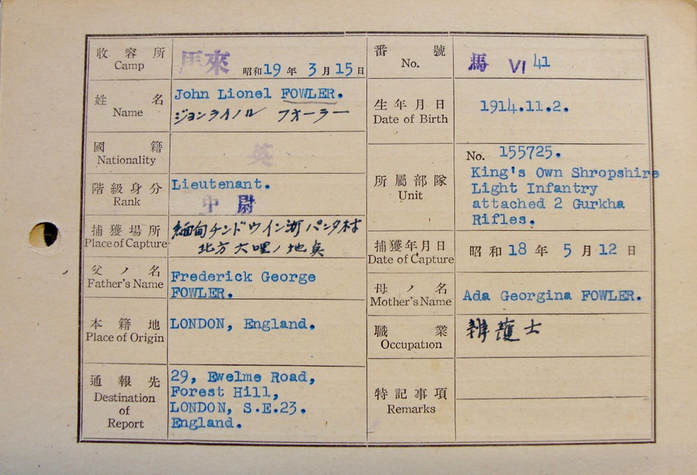

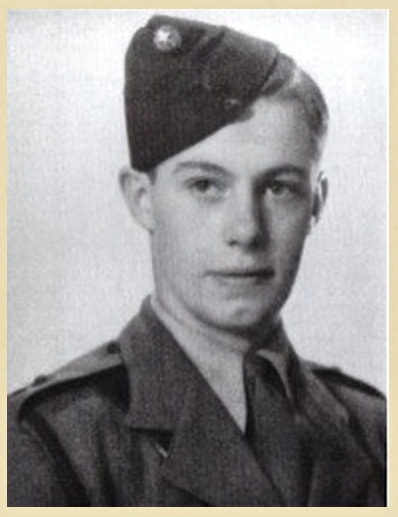

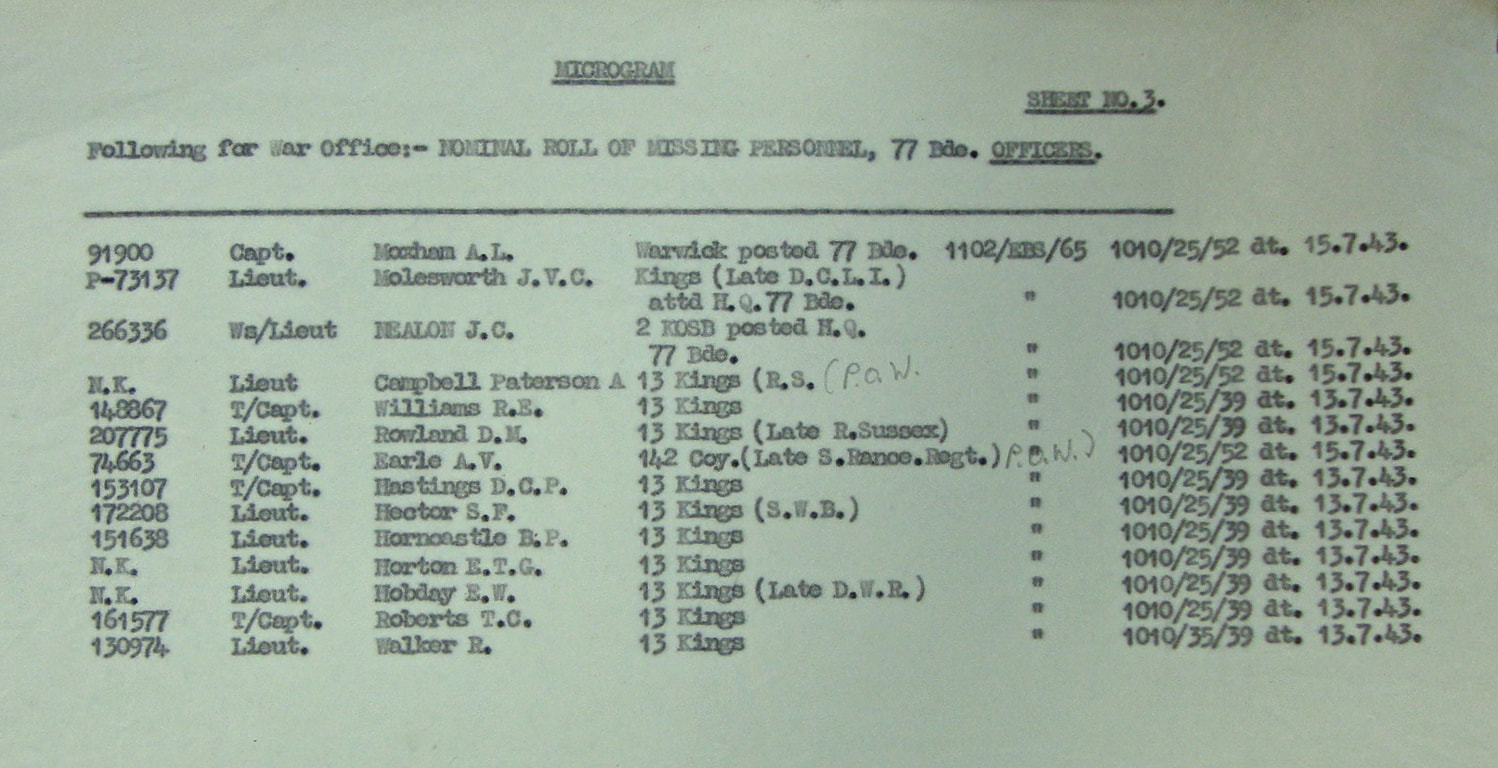

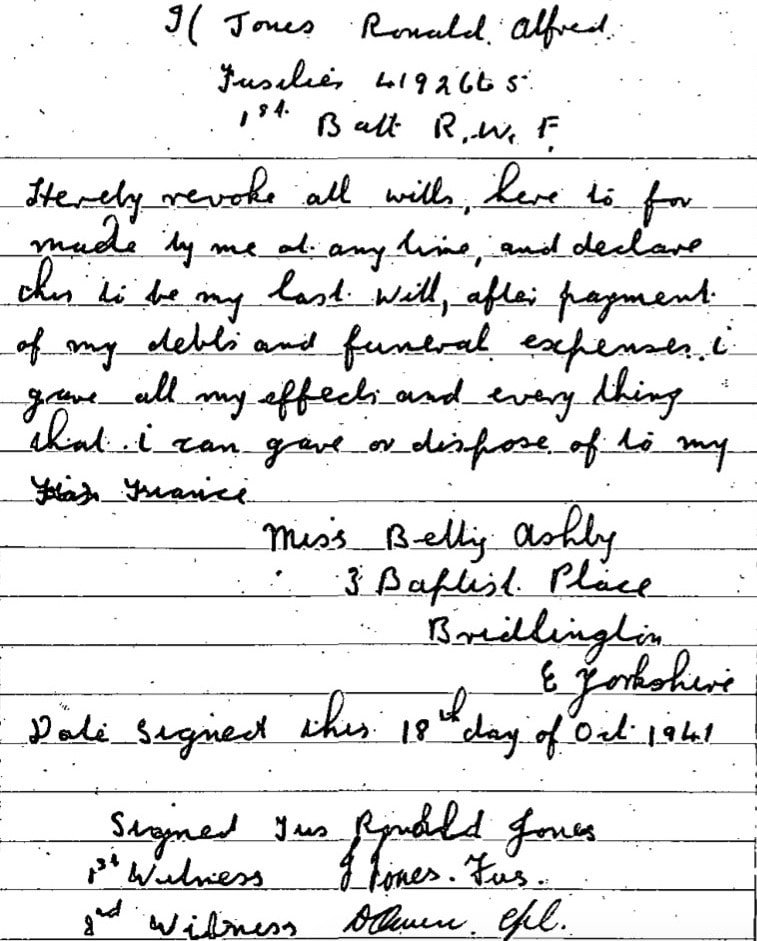

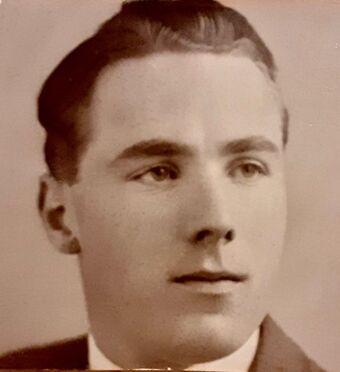

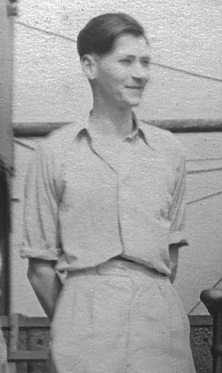

FOWLER, JOHN LIONEL

Rank: Lieutenant

Service No: 155725

Age: 29

Regiment/Service: 3/2 Gurkha Rifles.

Chindit Column: 1

Other details:

John Lionel Fowler was born on the 2nd November 1914 and was the son of Frederick and Ada Georgina Fowler from Forest Hill in southeast London. Originally enlisted into the King's Own Shropshire Light Infantry, John was posted overseas and was transferred to the 3rd Battalion of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles in India during late 1942.

Having been selected alongside, Bill Smyly, Alec Irving and Dominic Neill to perform the roll of Animal Transport, all four young officers were placed into D' company of the battalion and commenced training for Operation Longcloth at Saugor in the Central Provinces of India. Eventually the four subalterns were allocated to their Chindit columns and John Fowler was sent to join No. 1 Column under the overall command of Major George Dunlop formerly of the Royal Scots.

To read more about these early days as an Animal Transport officer, please click on the pages in the gallery below, taken from Lt. Dominic Neill's Chindit memoir entitled, One More River.

Rank: Lieutenant

Service No: 155725

Age: 29

Regiment/Service: 3/2 Gurkha Rifles.

Chindit Column: 1

Other details:

John Lionel Fowler was born on the 2nd November 1914 and was the son of Frederick and Ada Georgina Fowler from Forest Hill in southeast London. Originally enlisted into the King's Own Shropshire Light Infantry, John was posted overseas and was transferred to the 3rd Battalion of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles in India during late 1942.

Having been selected alongside, Bill Smyly, Alec Irving and Dominic Neill to perform the roll of Animal Transport, all four young officers were placed into D' company of the battalion and commenced training for Operation Longcloth at Saugor in the Central Provinces of India. Eventually the four subalterns were allocated to their Chindit columns and John Fowler was sent to join No. 1 Column under the overall command of Major George Dunlop formerly of the Royal Scots.

To read more about these early days as an Animal Transport officer, please click on the pages in the gallery below, taken from Lt. Dominic Neill's Chindit memoir entitled, One More River.

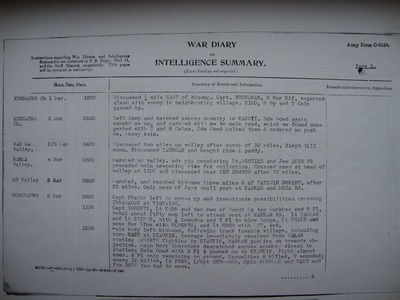

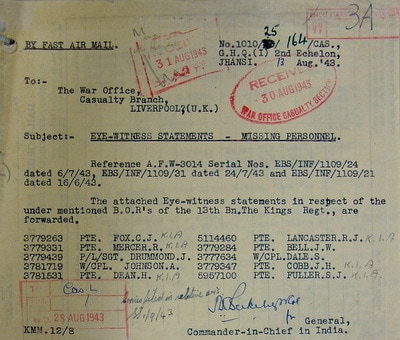

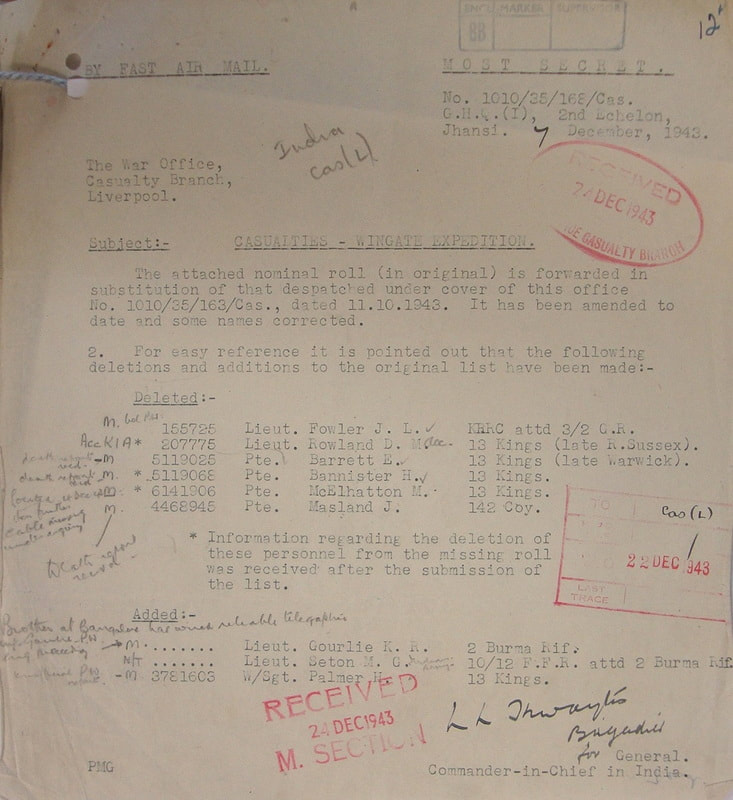

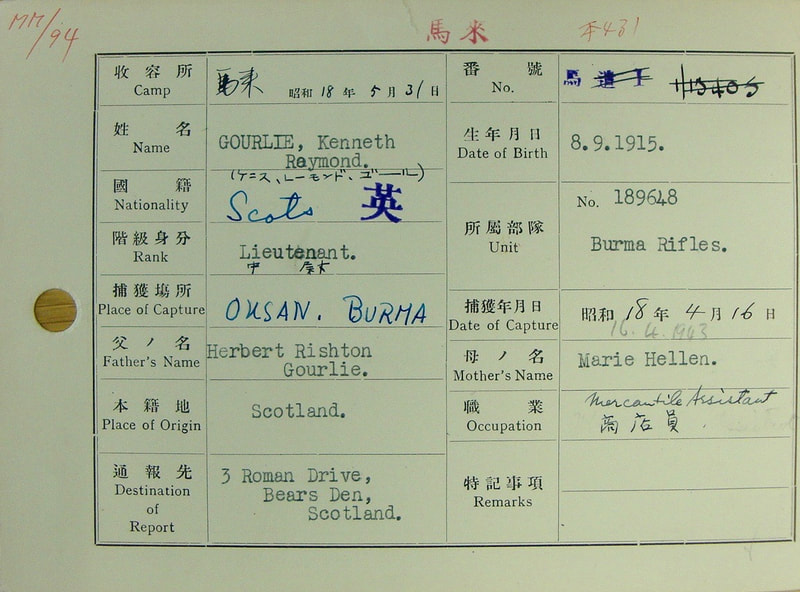

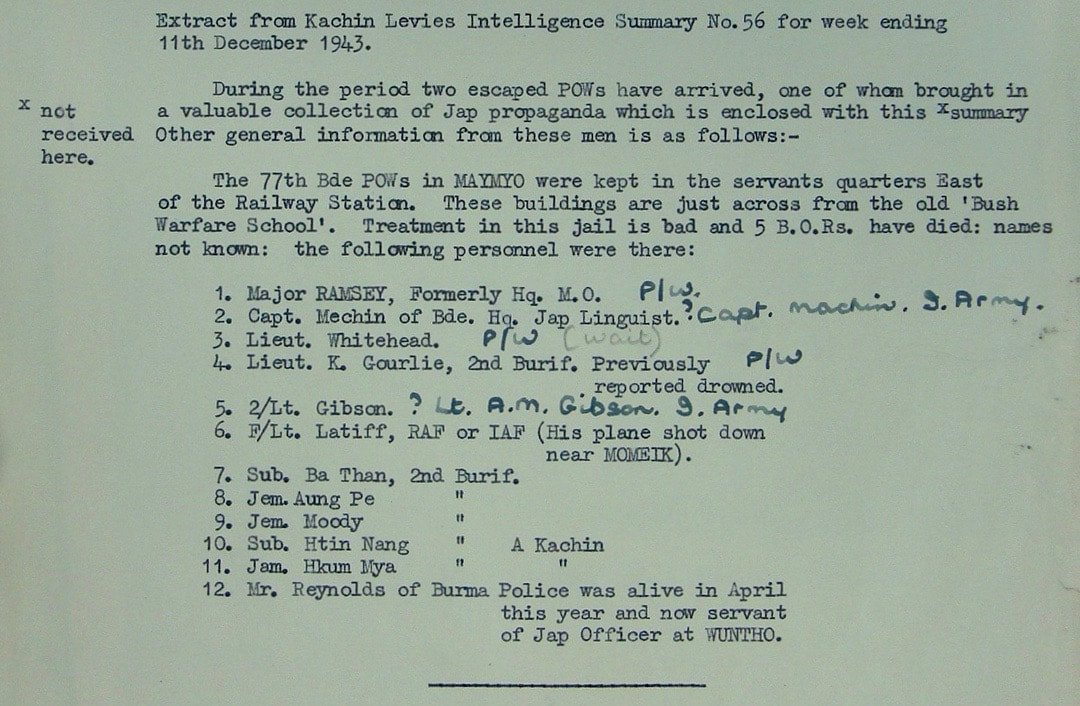

From the book, Wingate's Lost Brigade, by author Philip Chinnery:

As the year (1942) came to an end, 1 Column was brought up to strength with the arrival of some new blood, in the shape of Medical Officer Captain Norman Stocks, RAF Liaison Officer John Redman, the Animal Transport Officer Lt. John Fowler with the rest of the mules, and two young subalterns, 2nd Lieutenants Harvey and Wormell. They had to learn quickly as there were two river-crossing exercises planned and wireless training to be carried out by the newly arrived Signal Section.

Major Dunlop and his officers were called to Brigade Headquarters at Imphal and given their instructions by Wingate, which were short and very much to the point:

a) Together with 2 Column, they were to create a diversion to the south of the main objectives to be performed by Columns 3,4,5,7 and 8 (Northern Group). Their orders were to operate openly in the area to the east of Auktaung in order to draw off as many Japanese patrols as possible.

b) To then meet Brigadier Wingate, in the low ground beyond Tagaung on the east side of the Irrawaddy River in early March.

c) Or, having failed to make this meeting, to travel to Mongmit and encourage a rebellion amongst the Burmese against the Japanese occupation.

On the 6th January 1943, the Chindit Brigade boarded a succession of special trains at Jhansi in preparation for their journey up to Dimapur in Assam. Some personnel from 1 Column under the temporary command of Brigade-Major G. Menzies-Anderson were loaded on to train SA 5 at Jhansi, included amongst the passengers on this train were Medical Officer Captain Norman Stocks and Lieutenant John Fowler. In a rather amusing movement order written for the transfer of the Brigade, it was stated that officers must be prepared to travel in 2nd or even 3rd Class carriages for the duration of the journey, as there was a severe shortage of 1st Class accommodation available.

From Dimapur, the Brigade marched along the Manipur Road towards Imphal. They marched only at night in order to allow normal Army traffic to use the road during daylight hours, but also to keep their presence and direction of travel as secretive as they possibly could. After reaching Imphal 77th Brigade assembled for the very last time as one unit, before setting off for the Chindwin River by column formation and crossing into Burma.

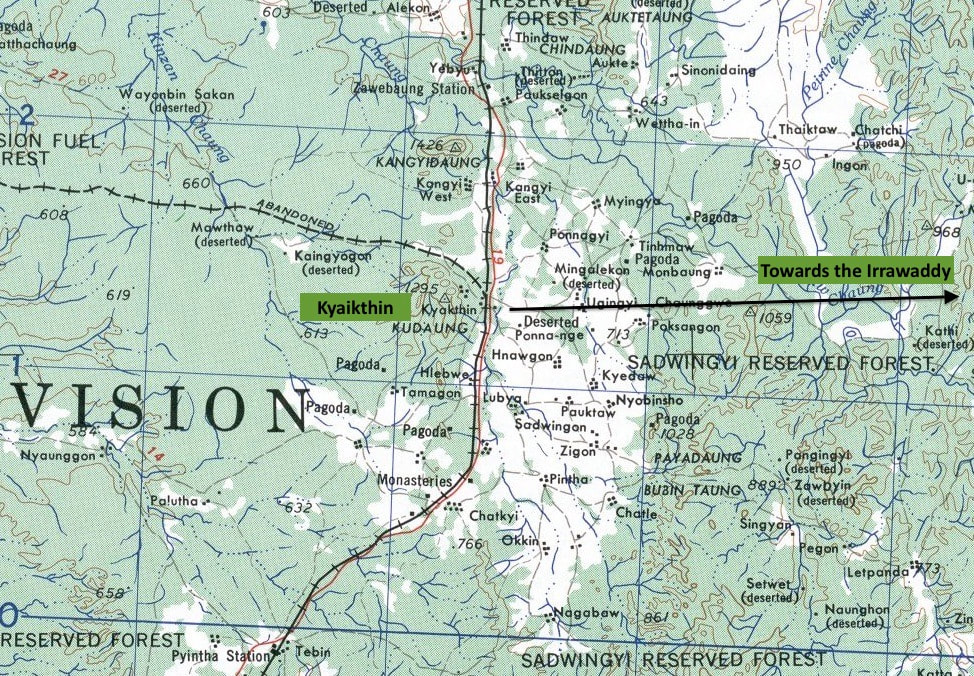

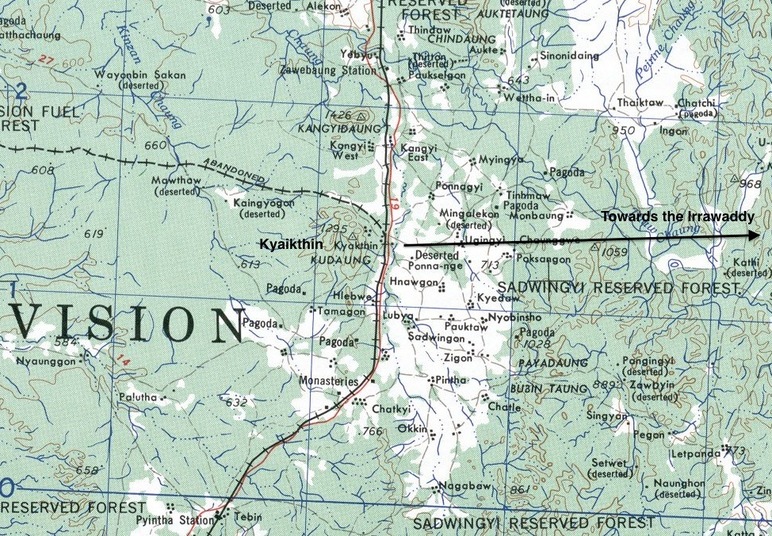

Southern Group crossed the Chindwin on 15/16th February 1943 at a place called Auktaung. Their orders were to march toward their prime objective, the rail station at Kyaikthin. They marched openly along well known local trails and paths and also received a large supply drop from the air, which must have announced their presence in the area to the Japanese. The decoy group were accompanied at this time by a Company of Sikh Mountain Artillery and a section of Seaforth Highlanders. These supplementary units were to create a further diversion for Wingate by attacking the town of Pantha, alerting the enemy to the possibility that there might well be a full-scale re-invasion taking place. To all intents and purposes these decoy tactics succeeded and Northern Group did proceed unmolested toward their own specific objectives.

As the year (1942) came to an end, 1 Column was brought up to strength with the arrival of some new blood, in the shape of Medical Officer Captain Norman Stocks, RAF Liaison Officer John Redman, the Animal Transport Officer Lt. John Fowler with the rest of the mules, and two young subalterns, 2nd Lieutenants Harvey and Wormell. They had to learn quickly as there were two river-crossing exercises planned and wireless training to be carried out by the newly arrived Signal Section.

Major Dunlop and his officers were called to Brigade Headquarters at Imphal and given their instructions by Wingate, which were short and very much to the point:

a) Together with 2 Column, they were to create a diversion to the south of the main objectives to be performed by Columns 3,4,5,7 and 8 (Northern Group). Their orders were to operate openly in the area to the east of Auktaung in order to draw off as many Japanese patrols as possible.

b) To then meet Brigadier Wingate, in the low ground beyond Tagaung on the east side of the Irrawaddy River in early March.

c) Or, having failed to make this meeting, to travel to Mongmit and encourage a rebellion amongst the Burmese against the Japanese occupation.

On the 6th January 1943, the Chindit Brigade boarded a succession of special trains at Jhansi in preparation for their journey up to Dimapur in Assam. Some personnel from 1 Column under the temporary command of Brigade-Major G. Menzies-Anderson were loaded on to train SA 5 at Jhansi, included amongst the passengers on this train were Medical Officer Captain Norman Stocks and Lieutenant John Fowler. In a rather amusing movement order written for the transfer of the Brigade, it was stated that officers must be prepared to travel in 2nd or even 3rd Class carriages for the duration of the journey, as there was a severe shortage of 1st Class accommodation available.

From Dimapur, the Brigade marched along the Manipur Road towards Imphal. They marched only at night in order to allow normal Army traffic to use the road during daylight hours, but also to keep their presence and direction of travel as secretive as they possibly could. After reaching Imphal 77th Brigade assembled for the very last time as one unit, before setting off for the Chindwin River by column formation and crossing into Burma.

Southern Group crossed the Chindwin on 15/16th February 1943 at a place called Auktaung. Their orders were to march toward their prime objective, the rail station at Kyaikthin. They marched openly along well known local trails and paths and also received a large supply drop from the air, which must have announced their presence in the area to the Japanese. The decoy group were accompanied at this time by a Company of Sikh Mountain Artillery and a section of Seaforth Highlanders. These supplementary units were to create a further diversion for Wingate by attacking the town of Pantha, alerting the enemy to the possibility that there might well be a full-scale re-invasion taking place. To all intents and purposes these decoy tactics succeeded and Northern Group did proceed unmolested toward their own specific objectives.

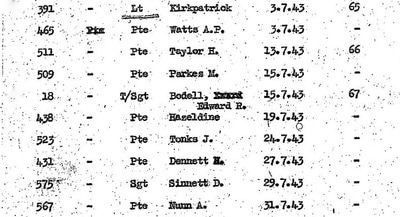

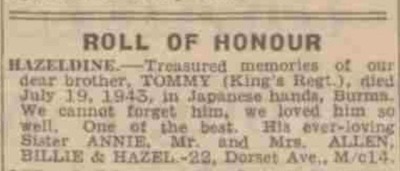

From the personal diary of Lt. Robert Peter Wormell, assistant Animal Transport officer for No. 1 Column: