Pte. Eric Allen and the Lost Boat on the Shweli

Within one week of this website being published I had received two brand new Longcloth family contacts. Here is the written memoir of Pte. Eric Allen, a soldier with column 8 in 1943. Eric (seen in the photograph to the left and courtesy of the Hale family) had been with the unit since entering Burma in February 1943, now six weeks later the column faced yet another of those formidable Burmese obstacles, the River Shweli.

I have left the following account as the author presented it in 1943. This is to ensure authenticity and retain the full context of his words as and when he wrote them. I would like to thank Eric's granddaughter Clare Hale and her family for allowing me to reproduce his story.

Firstly, I will let Sergeant Tony Aubrey, also in column 8 that year set the scene:

"We reached the River Shweli shortly after nightfall, and received orders to have a meal and rest for a couple of hours before attempting a crossing at moonrise".

“The Shweli at this point was about 180 yards across. The first fifty yards of water from the southern bank are very deep and flow at about four knots. Then comes a sandbank which stands several feet clear of the water”.

"We first needed someone to swim the river in order to set the power ropes on the far bank, this way all the party could make their way over by pulling the RAF dinghies hand over hand across the water".

"Captain Williams was given the honour of taking his platoon across first. At moonrise the first twelve with the Captain included, took their places in the dinghies and the crossing began. At first all went well………………….."

I have left the following account as the author presented it in 1943. This is to ensure authenticity and retain the full context of his words as and when he wrote them. I would like to thank Eric's granddaughter Clare Hale and her family for allowing me to reproduce his story.

Firstly, I will let Sergeant Tony Aubrey, also in column 8 that year set the scene:

"We reached the River Shweli shortly after nightfall, and received orders to have a meal and rest for a couple of hours before attempting a crossing at moonrise".

“The Shweli at this point was about 180 yards across. The first fifty yards of water from the southern bank are very deep and flow at about four knots. Then comes a sandbank which stands several feet clear of the water”.

"We first needed someone to swim the river in order to set the power ropes on the far bank, this way all the party could make their way over by pulling the RAF dinghies hand over hand across the water".

"Captain Williams was given the honour of taking his platoon across first. At moonrise the first twelve with the Captain included, took their places in the dinghies and the crossing began. At first all went well………………….."

By Guess and by God, a true story of Wingate’s original Chindits, and their first expedition into Burma.

“We came to a river and we couldn’t get across”………………………the only difference was, we were not singing. We had walked, hacked and sweated our way across the hundreds of miles of Jap-infested country, that sweat box, the bamboo dark, malarial fever stricken country that called itself Burma. It is on the banks of the Irrawaddy that my story begins.

I was part of a body of men, English, Burmese and Gurkha who formed that suicidal squad known as a ‘long range penetration group’ under the command of the world’s most eccentric leader, Major-General Orde Wingate.

We were the first troops back into Burma after the Japanese conquest of the country; a country where there is enough teak to pay the National Debt, where salt is far more valuable than diamonds, yet where hard roads are practically non-existent. Therefore our lines of communication with our base in India were nil.

It was originally planned to supply us from the air, a scheme that never worked out, so we just had to live on what we could forage. This, in the main, meant rice supplemented by the meat of our dead mules, and once or twice by steaks of python, by the way a delicacy I can recommend to anybody.

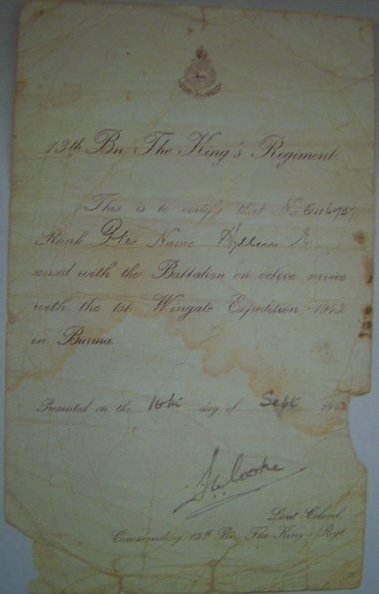

The brigade consisted of about a thousand men; the only British battalion being the 13th King’s Liverpool’s. I must place this on record here and now – these were the men that gave the world a new name- “The Chindits”. So many came after, so many claimed this doubtful honour, but let me say, if only in remembrance of the hundreds of men we lost, that the name “Chindit” belongs only to those who can produce a replica of the signed certificate. My own enclosed. (Eric's certificate can be seen pictured to your right, signed correctly by Lieutenant Colonel Sam Cooke).

One aircraft had managed to reach us before we were to cross the Irrawaddy, and had dropped us some large RAF type rubber dinghys.

The river ran along the valleys like a great rolling giant. Its width would compare with the Thames at Tilbury.

“We came to a river and we couldn’t get across”………………………the only difference was, we were not singing. We had walked, hacked and sweated our way across the hundreds of miles of Jap-infested country, that sweat box, the bamboo dark, malarial fever stricken country that called itself Burma. It is on the banks of the Irrawaddy that my story begins.

I was part of a body of men, English, Burmese and Gurkha who formed that suicidal squad known as a ‘long range penetration group’ under the command of the world’s most eccentric leader, Major-General Orde Wingate.

We were the first troops back into Burma after the Japanese conquest of the country; a country where there is enough teak to pay the National Debt, where salt is far more valuable than diamonds, yet where hard roads are practically non-existent. Therefore our lines of communication with our base in India were nil.

It was originally planned to supply us from the air, a scheme that never worked out, so we just had to live on what we could forage. This, in the main, meant rice supplemented by the meat of our dead mules, and once or twice by steaks of python, by the way a delicacy I can recommend to anybody.

The brigade consisted of about a thousand men; the only British battalion being the 13th King’s Liverpool’s. I must place this on record here and now – these were the men that gave the world a new name- “The Chindits”. So many came after, so many claimed this doubtful honour, but let me say, if only in remembrance of the hundreds of men we lost, that the name “Chindit” belongs only to those who can produce a replica of the signed certificate. My own enclosed. (Eric's certificate can be seen pictured to your right, signed correctly by Lieutenant Colonel Sam Cooke).

One aircraft had managed to reach us before we were to cross the Irrawaddy, and had dropped us some large RAF type rubber dinghys.

The river ran along the valleys like a great rolling giant. Its width would compare with the Thames at Tilbury.

We had started from Imphal with horses, mules, elephants and dogs. The hard cruel march had killed all these, and our number of men had been reduced by the enemy, by fever and by just not being able to go on. No sooner had we formed up on the river banks in the cool grey dawn, than the enemy on the opposite bank opened up with everything. Mortars, artillery and rifle fire plastered us.

In retaliation our heaviest weapon was the Bren, and it was just ammunition wasted as we pumped it into the thick jungle vegetation in which the Japs were dug in. The Japs are the world’s cleverest people in the art of camouflage, being small of stature so that every bamboo could hide a sniper or a nest of mortars. Our columns were spread out along the banks of the river, but whenever they showed themselves, firing immediately started from the enemy.

It was three months now since we had eaten a solid meal, since we had shaved or changed our clothes. Our bodies were swollen with malnutrition and we were being eaten alive by lice and other vermin. Our eyes and our foreheads were about the only parts of our faces that were not covered by thick, filthy hair. My original khaki slacks were reduced to tattered shorts, and my legs were covered in angry looking jungle sores. These formed after the slightest scratch.

Orders were in confusion along that river bank that morning. What confidence we had had in Wingate was now shattered. We knew our epitaph had been written by Delhi before we started. Even Lord Wavell had saluted us: the traditional eyes right or left salute of the British Army had been dispensed with and Wavell stood smartly to attention, his hand raised in salute until every man and animal had gone by. A message in his eyes seemed to say “Goodbye, god bless you, but please don’t blame me”.

Wingate now realised that to carry on as a fighting force was useless. His hard, cruel mind could no longer conceive the idea that we could cross that river and fight on.

He took the line of least resistance here, and bade us a soldier’s farewell as he ordered every column to find it’s own independent way back to India. My column commander was Major Scott. He gave us a pep talk and tried to boost our morale as we turned around to make our retreat.

Each column had been given a rubber dinghy to assist them in any more river crossings that might be encountered. Our line of retreat was not to retrace our footsteps, and so after a short conference with the few officers we had left, our commander decided his route. We knew, we had been told, that should we run into a large concentration of the enemy we were to run away. To get out alive was our target.

Once again we had to hack our way though virgin jungle, only this time we had no mules to hamper us. Days and dates were things of the past: not one of us knew what month it was. During the whole of the campaign we could not send letters home, nor could we receive any.

Several days after leaving Wingate, we ran into another water barrier, the River Seweli (Shweli), not as big as the Irrawaddy, but a very fast flowing river with treacherous currents, and dangerous steep banks almost as straight as a brick wall. It was decided to cross this using the dinghy as a ferry. A volunteer offered to swim this river with a rope which was to be fastened to a tree on the opposite bank, and then back to our side so as to form a hand rail to enable the dinghy to be manhandled across and back again. Not really a feat of endurance to a fit man, but what of us, the walking dead?

I was destined to be in the first boat, along with eleven other men and what kit we had. I was picked to stand up and pull the rope across. We twelve men consisted of ten British privates, one NCO and one of the Burmese troops who could speak English. The weight of the loaded dinghy held by one man to the taut rope, against the fierce current was burning and cutting my hands, and I was on the point of collapse when the NCO took over.

Calamity once again overtook us here. The sergeant soon found it physically impossible to manhandle that boat. He collapsed to the deck of the dinghy. It happened so quickly that not one of us could grab that rope again, and the dinghy swept on with the current. We tried to paddle it with our hands, our feet, even our rifles, but to no avail. On we went. The speed of that river is hard to believe, but it must have been miles downstream before a sandbank slowed us down long enough for a couple of us to drop overboard, and after a long, exhausting struggle, get it to the other bank. One man, waist deep in water, held the dinghy against the bank, which again was very steep, and made of dried mud. The tow rope of the dinghy was held by another man who had a foothold on the bank, and the rest of the men scrambled and climbed out.

In retaliation our heaviest weapon was the Bren, and it was just ammunition wasted as we pumped it into the thick jungle vegetation in which the Japs were dug in. The Japs are the world’s cleverest people in the art of camouflage, being small of stature so that every bamboo could hide a sniper or a nest of mortars. Our columns were spread out along the banks of the river, but whenever they showed themselves, firing immediately started from the enemy.

It was three months now since we had eaten a solid meal, since we had shaved or changed our clothes. Our bodies were swollen with malnutrition and we were being eaten alive by lice and other vermin. Our eyes and our foreheads were about the only parts of our faces that were not covered by thick, filthy hair. My original khaki slacks were reduced to tattered shorts, and my legs were covered in angry looking jungle sores. These formed after the slightest scratch.

Orders were in confusion along that river bank that morning. What confidence we had had in Wingate was now shattered. We knew our epitaph had been written by Delhi before we started. Even Lord Wavell had saluted us: the traditional eyes right or left salute of the British Army had been dispensed with and Wavell stood smartly to attention, his hand raised in salute until every man and animal had gone by. A message in his eyes seemed to say “Goodbye, god bless you, but please don’t blame me”.

Wingate now realised that to carry on as a fighting force was useless. His hard, cruel mind could no longer conceive the idea that we could cross that river and fight on.

He took the line of least resistance here, and bade us a soldier’s farewell as he ordered every column to find it’s own independent way back to India. My column commander was Major Scott. He gave us a pep talk and tried to boost our morale as we turned around to make our retreat.

Each column had been given a rubber dinghy to assist them in any more river crossings that might be encountered. Our line of retreat was not to retrace our footsteps, and so after a short conference with the few officers we had left, our commander decided his route. We knew, we had been told, that should we run into a large concentration of the enemy we were to run away. To get out alive was our target.

Once again we had to hack our way though virgin jungle, only this time we had no mules to hamper us. Days and dates were things of the past: not one of us knew what month it was. During the whole of the campaign we could not send letters home, nor could we receive any.

Several days after leaving Wingate, we ran into another water barrier, the River Seweli (Shweli), not as big as the Irrawaddy, but a very fast flowing river with treacherous currents, and dangerous steep banks almost as straight as a brick wall. It was decided to cross this using the dinghy as a ferry. A volunteer offered to swim this river with a rope which was to be fastened to a tree on the opposite bank, and then back to our side so as to form a hand rail to enable the dinghy to be manhandled across and back again. Not really a feat of endurance to a fit man, but what of us, the walking dead?

I was destined to be in the first boat, along with eleven other men and what kit we had. I was picked to stand up and pull the rope across. We twelve men consisted of ten British privates, one NCO and one of the Burmese troops who could speak English. The weight of the loaded dinghy held by one man to the taut rope, against the fierce current was burning and cutting my hands, and I was on the point of collapse when the NCO took over.

Calamity once again overtook us here. The sergeant soon found it physically impossible to manhandle that boat. He collapsed to the deck of the dinghy. It happened so quickly that not one of us could grab that rope again, and the dinghy swept on with the current. We tried to paddle it with our hands, our feet, even our rifles, but to no avail. On we went. The speed of that river is hard to believe, but it must have been miles downstream before a sandbank slowed us down long enough for a couple of us to drop overboard, and after a long, exhausting struggle, get it to the other bank. One man, waist deep in water, held the dinghy against the bank, which again was very steep, and made of dried mud. The tow rope of the dinghy was held by another man who had a foothold on the bank, and the rest of the men scrambled and climbed out.

I will pause at this point in Eric's account in order to give the reader the official War Diary version of this incident, as given in 1943 by the commander of column 8 Major Walter P. Scott (seen pictured left).

Entry dated 1st April 1943:

"Recce of the River Shweli carried out this afternoon, decided to attempt a crossing tonight at point 2563, Wingba Cliffs. Column moved down to the riverbanks at dusk. Rope was got across the fast flowing near side. Captain Williams, Lieutenants Hobday and Horton and 29 Other Ranks crossed to form a protective bridgehead ".

"The next group led by Sergeant Scruton immediately got into difficulties mid-stream and had to cut the rope away from the main line. This boat drifted away downstream. The crossing was subsequently called off. Captain Williams’s party was ordered to move off west under his leadership".

Entry dated 1st April 1943:

"Recce of the River Shweli carried out this afternoon, decided to attempt a crossing tonight at point 2563, Wingba Cliffs. Column moved down to the riverbanks at dusk. Rope was got across the fast flowing near side. Captain Williams, Lieutenants Hobday and Horton and 29 Other Ranks crossed to form a protective bridgehead ".

"The next group led by Sergeant Scruton immediately got into difficulties mid-stream and had to cut the rope away from the main line. This boat drifted away downstream. The crossing was subsequently called off. Captain Williams’s party was ordered to move off west under his leadership".

Eric's account now continues:

Our plan here was to walk back up the bank of the river to where we had crossed and get the dinghy back to the rest of the column. I should say we had drifted about eight miles. But once again we reckoned without nature, because before we could get one rifle or piece of equipment out, the man holding the dinghy lost his foothold, and the little craft, swiftly claimed by the current was soon lost to view with every single thing we possessed on board. So, the clothes we stood up in and our guts were all we had left. This story likens to the “Ten Little Nigger Boys”: first a brigade, then a column, now twelve men alone in enemy held country, a thousand miles from India with no map, no compass, no food, not even a match.

From now on this story can only be written by three men in this world today (that is assuming the other two are still alive). Apart form all the names, the story is imprinted on my mind like a scar from any bodily wound, and to this day still gives me nightmares.

All I can remember of the names are Pte. Joe Hoyle from somewhere near Manchester. Pte. R. Johnson, Sergeant Scrutton and an Anglo-Burmese who I believe was named ‘Stanley’ by us.

The Sergeant now took complete command, and rightly or wrongly his decisions must be obeyed. It was to be twelve men against the enemy infested green hell of the jungle with only the sun and God to guide us. Without a compass, to follow the sun was a simple decision. But to follow the sun out east is a difficult job; it is immediately overhead for much of the day, but anyhow we were glad of that welcome rest, as two or three hours marching was all that we could stand.

This following the sun business was taken very seriously by our sergeant who steered a dead straight course by it, a course that took every natural hazard in turn, mountains, paddy fields, bamboo thickets and knee deep gulleys of stagnant water. All of us were now barefoot. I did not know feet could get so hard so quickly, because the country we walked over was no turfy loam. With the exception of a few jungle bananas, Burma could offer us nothing in the way of natural food. Stanley, the Burmese, proved a very great asset by being able to talk to the villagers in their native tongue. We realised that this was a terrible risk as there were no friendly villagers, and we might be betrayed to the Japs at any time. But it was a risk we had to take, our stomachs dictated that.

Every time we stopped for a rest the main topic of conversation was home, our wives, our children. I had one son who had been just a few hours old when I sailed from England. Was this Devil’s own country going to rob me of ever seeing him?

Depression was with all of us now; our morale was low as it could be: days came and went punctuated only by the hours of darkness, and darkness brought the fear of wild animals. We only slept fitfully; what sleep we did have was from sheer exhaustion. Our bodies were feeling the strains of the lack of salt for we were not replacing our sweat. Water, green and muddy we drank from animal waterholes.

Once or twice we had picked up the tracks of a Japanese motorised column or the tyre marks of a bicycle patrol on some of the cart track roads leading to villages. These caused us to go miles out of our way again. We were ourselves getting very careless at times, the thought of getting to India, over-ruling the thought of the enemy. Our awakening from this dream came out of the blue, as suddenly as a car collision.

We were climbing a grassy slope, the sun declining behind us and we could count on marching another hour before it was lost to sight. Sergeant Scruton reached the top of the slope, when we heard him shout, “there’s Japs…run”. The familiar denim peaked caps of the enemy came into view, and we all stood motionless like rabbits hypnotised by a car’s lamps, until the quick crack of their guns sent us running.

I ran for what seemed miles and dived into the thickest clump of bamboo I could find and lay there motionless, my heart hammering against the bones of my chest like a tap drummer’s serenade. Joe and Stanley (Burma Rifle) had followed me and we lay there not daring to move or speak. The Japs were searching the surrounding country, we could hear them, and once saw them just a few feet away. Darkness gave us more confidence and the Japs went. So we lay there until dawn.

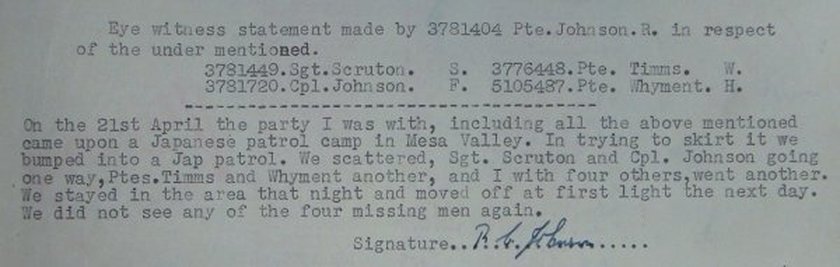

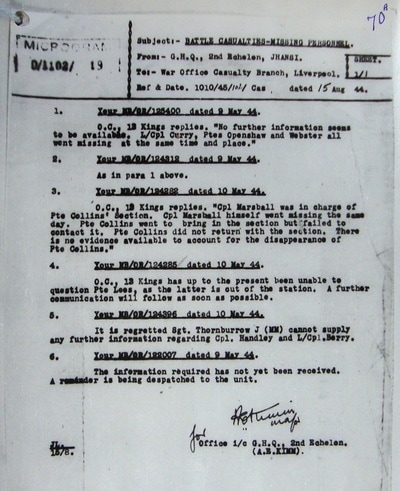

Again I will pause Eric's account to show the reader a witness statement given by Pte. Ronald Johnson also of the 13th Kings that fateful year. He too was in column 8, and in the boat that had been swept away on April Fool's Day in 1943. shown below is his account of the moment the group stumbled into that Japanese patrol. From his report you will see that according to Pte. Johnson this was about the 21st April.

Our plan here was to walk back up the bank of the river to where we had crossed and get the dinghy back to the rest of the column. I should say we had drifted about eight miles. But once again we reckoned without nature, because before we could get one rifle or piece of equipment out, the man holding the dinghy lost his foothold, and the little craft, swiftly claimed by the current was soon lost to view with every single thing we possessed on board. So, the clothes we stood up in and our guts were all we had left. This story likens to the “Ten Little Nigger Boys”: first a brigade, then a column, now twelve men alone in enemy held country, a thousand miles from India with no map, no compass, no food, not even a match.

From now on this story can only be written by three men in this world today (that is assuming the other two are still alive). Apart form all the names, the story is imprinted on my mind like a scar from any bodily wound, and to this day still gives me nightmares.

All I can remember of the names are Pte. Joe Hoyle from somewhere near Manchester. Pte. R. Johnson, Sergeant Scrutton and an Anglo-Burmese who I believe was named ‘Stanley’ by us.

The Sergeant now took complete command, and rightly or wrongly his decisions must be obeyed. It was to be twelve men against the enemy infested green hell of the jungle with only the sun and God to guide us. Without a compass, to follow the sun was a simple decision. But to follow the sun out east is a difficult job; it is immediately overhead for much of the day, but anyhow we were glad of that welcome rest, as two or three hours marching was all that we could stand.

This following the sun business was taken very seriously by our sergeant who steered a dead straight course by it, a course that took every natural hazard in turn, mountains, paddy fields, bamboo thickets and knee deep gulleys of stagnant water. All of us were now barefoot. I did not know feet could get so hard so quickly, because the country we walked over was no turfy loam. With the exception of a few jungle bananas, Burma could offer us nothing in the way of natural food. Stanley, the Burmese, proved a very great asset by being able to talk to the villagers in their native tongue. We realised that this was a terrible risk as there were no friendly villagers, and we might be betrayed to the Japs at any time. But it was a risk we had to take, our stomachs dictated that.

Every time we stopped for a rest the main topic of conversation was home, our wives, our children. I had one son who had been just a few hours old when I sailed from England. Was this Devil’s own country going to rob me of ever seeing him?

Depression was with all of us now; our morale was low as it could be: days came and went punctuated only by the hours of darkness, and darkness brought the fear of wild animals. We only slept fitfully; what sleep we did have was from sheer exhaustion. Our bodies were feeling the strains of the lack of salt for we were not replacing our sweat. Water, green and muddy we drank from animal waterholes.

Once or twice we had picked up the tracks of a Japanese motorised column or the tyre marks of a bicycle patrol on some of the cart track roads leading to villages. These caused us to go miles out of our way again. We were ourselves getting very careless at times, the thought of getting to India, over-ruling the thought of the enemy. Our awakening from this dream came out of the blue, as suddenly as a car collision.

We were climbing a grassy slope, the sun declining behind us and we could count on marching another hour before it was lost to sight. Sergeant Scruton reached the top of the slope, when we heard him shout, “there’s Japs…run”. The familiar denim peaked caps of the enemy came into view, and we all stood motionless like rabbits hypnotised by a car’s lamps, until the quick crack of their guns sent us running.

I ran for what seemed miles and dived into the thickest clump of bamboo I could find and lay there motionless, my heart hammering against the bones of my chest like a tap drummer’s serenade. Joe and Stanley (Burma Rifle) had followed me and we lay there not daring to move or speak. The Japs were searching the surrounding country, we could hear them, and once saw them just a few feet away. Darkness gave us more confidence and the Japs went. So we lay there until dawn.

Again I will pause Eric's account to show the reader a witness statement given by Pte. Ronald Johnson also of the 13th Kings that fateful year. He too was in column 8, and in the boat that had been swept away on April Fool's Day in 1943. shown below is his account of the moment the group stumbled into that Japanese patrol. From his report you will see that according to Pte. Johnson this was about the 21st April.

Eric's story continues to it's conclusion:

I have previously remarked on the comparison between this story and the “ Ten Little Nigger Boys”..well, now there were three. Although we never spoke of it until long afterwards, the thought uppermost in our minds was “whose turn next?”

The story of our trek from here on was much the same as before, but Joe now took command. I will not bore you with repetition but will only pick out the really interesting happenings on the rest of this journey.

Villages were now becoming few and far between. Our main diet, when we could find a village, was still rice, and more rice. Just cooked in muddy water without flavouring of any kind. I used to burn mine black to give it a different taste. I was having vivid hallucinations about food. I longed not for anything sweet, just a big plate of roast beef and all the trimmings. Was I going out of my mind? My burnt rice pudding tasted just like roast beef. I used to carve the black solid mass with a sharp piece of bamboo just as one would carve a juicy sirloin with a knife. I really believed my burnt mess was roast beef.

Joe’s chest was now giving him great trouble, and it was only with the greatest of fortitude that he carried on. He could not walk and talk at the same time, and even collapsed at times when fighting for his breath. Burma, with its hot, steamy climate is not ideal for people with chest complaints.

I cannot write this story without giving praise to the English-speaking Burmese lady who befriended us in one village we came across. It was now a great necessity for us to eat some proper food, to sleep for a whole night and to attend to our cuts and sores. We were ready to give ourselves up to any fate now; our endurance was at breaking point. So into the village of the English-speaking lady we marched. As always, we left Stanley to do the introductions in his native tongue, but this time he quickly passed it over to me when he learned of our benefactor.

No time was wasted on introductions. We sat on the floor of her “Basha” hut and she feasted us on curried dried fish, coconuts and water melons. In our hands we ate her greatest treasure…a tin of corned beef, whose fragrance when it was opened was out of this world.

She was obviously in complete control of this village, and was as English as a London bus. She posted look-outs all round to warn us of any enemy. The villagers brought us offerings of rice toddy, a potent drink like whisky, and we smoked again, not cigarettes but Burmese cheroots. And at the end of it all we were gloriously sick.

We slept in state that night, and stayed the next day as well. In fact it was all we could do to convince our hostess that we could not stay until the war was over. She said she had not seen any Japs there at all. She had been educated in an English College, and was a travelling teacher of English in Burma. Her father was a wealthy Rangoon merchant. We wanted her to come with us, but she would not dessert her friends in the village. As near as she could make out it was Good Friday.

She told us that the black wisps of cloud in an otherwise clear sky were signs of the coming monsoon, and out target, the Chindwin was about a weeks walk away. We left her early the next morning after spending two nights there and she sent us off with food tied up in great big leaves, and two guides to take us to the River Chindwin.

As the river came into sight our guides took their leave. We could only thank them with words; we had nothing to reward them with.

Stanley quickly commandeered a village boat complete with a villager to row us across to Assam and safety. We bribed him to row us across by a cruel hoax, the promise of a thousand rupees. Of course we could not fulfil it, but Joe promised to contact the War Office so that it could be included in the National Debt.

Once the Chindwin was crossed we were again on friendly soil, we had escaped a living death. The scene on the banks of the river as we three scarecrows stood there, needs a professional writer’s skill to describe. I will do my humble best.

Picture three men, two white, one black, kneeling on the damp sand, heads bent in prayer, a prayer of thanksgiving that came from our hearts. Tears streamed down my face through the thick hair covering my cheeks, their salt taste entering my mouth. As Joe wheezed and coughed his way through a prayer of his childhood, Stanley recited something from his religion and I croaked through “Praise God from whom all blessing flow”. So ended our simple service but there was more Faith and Belief in that simple service than in any pomp and ceremony to be found in an English Church.

The tracks we had made on our entry into Burma were soon picked up and we shortly found ourselves back on the Imphal Road. Even now we could find nobody who wanted to know us; no British troops were here, only the Indians. Our objective now was that haven of rest, to us, that British Military Hospital, "The Imphal Hospital” (Casualty Clearing Station number 19, where most of the returning Chindits were treated in 1943).

It was pitch dark when we at last arrived at its bundle of straw-roofed buildings. Our wanderings were over at last. Three empty beds on a verandah welcomed us in, and although it was sacrilege to throw our stinking, lice-ridden bodies on to those clean white sheets, we did just that. The hospital looked deserted, but we were happy and sleep was soon overcoming all three of us. Suddenly a blazing light was switched on, and a prim little English nurse walked on to the verandah. She stopped, she screamed and she ran. Her scream was an alarm. It seemed the entire hospital staff gathered at our beds, and questions were fired at us far quicker than we could answer. Even an official photographer was sent for. A new chapter in the story of the war against the Jap would break in the world’s newspapers.

We three had made it, against the odds of millions to one, and thanks be to God, I can say, “I was there”.

I have previously remarked on the comparison between this story and the “ Ten Little Nigger Boys”..well, now there were three. Although we never spoke of it until long afterwards, the thought uppermost in our minds was “whose turn next?”

The story of our trek from here on was much the same as before, but Joe now took command. I will not bore you with repetition but will only pick out the really interesting happenings on the rest of this journey.

Villages were now becoming few and far between. Our main diet, when we could find a village, was still rice, and more rice. Just cooked in muddy water without flavouring of any kind. I used to burn mine black to give it a different taste. I was having vivid hallucinations about food. I longed not for anything sweet, just a big plate of roast beef and all the trimmings. Was I going out of my mind? My burnt rice pudding tasted just like roast beef. I used to carve the black solid mass with a sharp piece of bamboo just as one would carve a juicy sirloin with a knife. I really believed my burnt mess was roast beef.

Joe’s chest was now giving him great trouble, and it was only with the greatest of fortitude that he carried on. He could not walk and talk at the same time, and even collapsed at times when fighting for his breath. Burma, with its hot, steamy climate is not ideal for people with chest complaints.

I cannot write this story without giving praise to the English-speaking Burmese lady who befriended us in one village we came across. It was now a great necessity for us to eat some proper food, to sleep for a whole night and to attend to our cuts and sores. We were ready to give ourselves up to any fate now; our endurance was at breaking point. So into the village of the English-speaking lady we marched. As always, we left Stanley to do the introductions in his native tongue, but this time he quickly passed it over to me when he learned of our benefactor.

No time was wasted on introductions. We sat on the floor of her “Basha” hut and she feasted us on curried dried fish, coconuts and water melons. In our hands we ate her greatest treasure…a tin of corned beef, whose fragrance when it was opened was out of this world.

She was obviously in complete control of this village, and was as English as a London bus. She posted look-outs all round to warn us of any enemy. The villagers brought us offerings of rice toddy, a potent drink like whisky, and we smoked again, not cigarettes but Burmese cheroots. And at the end of it all we were gloriously sick.

We slept in state that night, and stayed the next day as well. In fact it was all we could do to convince our hostess that we could not stay until the war was over. She said she had not seen any Japs there at all. She had been educated in an English College, and was a travelling teacher of English in Burma. Her father was a wealthy Rangoon merchant. We wanted her to come with us, but she would not dessert her friends in the village. As near as she could make out it was Good Friday.

She told us that the black wisps of cloud in an otherwise clear sky were signs of the coming monsoon, and out target, the Chindwin was about a weeks walk away. We left her early the next morning after spending two nights there and she sent us off with food tied up in great big leaves, and two guides to take us to the River Chindwin.

As the river came into sight our guides took their leave. We could only thank them with words; we had nothing to reward them with.

Stanley quickly commandeered a village boat complete with a villager to row us across to Assam and safety. We bribed him to row us across by a cruel hoax, the promise of a thousand rupees. Of course we could not fulfil it, but Joe promised to contact the War Office so that it could be included in the National Debt.

Once the Chindwin was crossed we were again on friendly soil, we had escaped a living death. The scene on the banks of the river as we three scarecrows stood there, needs a professional writer’s skill to describe. I will do my humble best.

Picture three men, two white, one black, kneeling on the damp sand, heads bent in prayer, a prayer of thanksgiving that came from our hearts. Tears streamed down my face through the thick hair covering my cheeks, their salt taste entering my mouth. As Joe wheezed and coughed his way through a prayer of his childhood, Stanley recited something from his religion and I croaked through “Praise God from whom all blessing flow”. So ended our simple service but there was more Faith and Belief in that simple service than in any pomp and ceremony to be found in an English Church.

The tracks we had made on our entry into Burma were soon picked up and we shortly found ourselves back on the Imphal Road. Even now we could find nobody who wanted to know us; no British troops were here, only the Indians. Our objective now was that haven of rest, to us, that British Military Hospital, "The Imphal Hospital” (Casualty Clearing Station number 19, where most of the returning Chindits were treated in 1943).

It was pitch dark when we at last arrived at its bundle of straw-roofed buildings. Our wanderings were over at last. Three empty beds on a verandah welcomed us in, and although it was sacrilege to throw our stinking, lice-ridden bodies on to those clean white sheets, we did just that. The hospital looked deserted, but we were happy and sleep was soon overcoming all three of us. Suddenly a blazing light was switched on, and a prim little English nurse walked on to the verandah. She stopped, she screamed and she ran. Her scream was an alarm. It seemed the entire hospital staff gathered at our beds, and questions were fired at us far quicker than we could answer. Even an official photographer was sent for. A new chapter in the story of the war against the Jap would break in the world’s newspapers.

We three had made it, against the odds of millions to one, and thanks be to God, I can say, “I was there”.

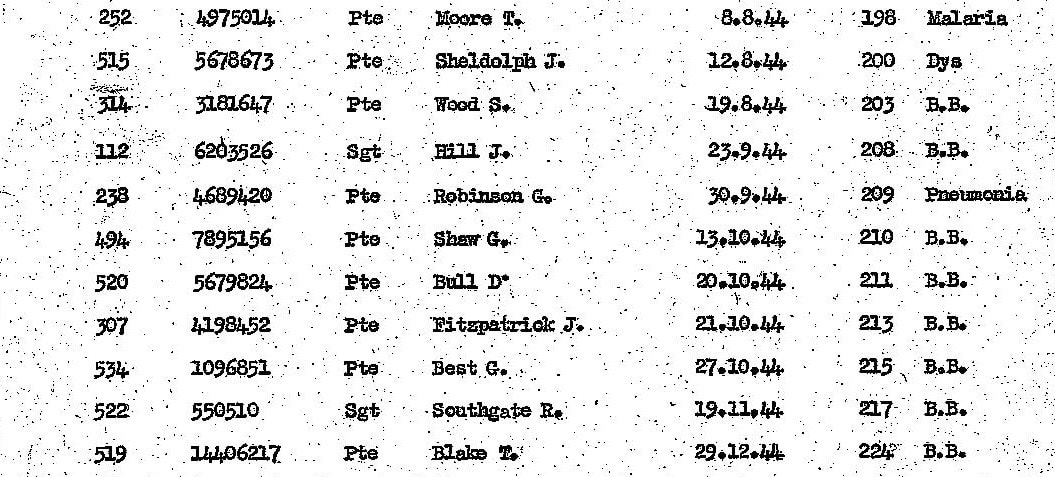

Sergeant Stanley Scruton.

After the disaster of the Shweli crossing, Stanley Scruton, devastated by his part in the debacle took control of the small group of men. In his own mind he felt he was responsible for the men becoming adrift from the main section on that terrible day. Even after eventual capture by the Japanese he worked tirelessly in the makeshift hospital in Rangoon Jail, almost as though this was his way of making amends.

For a long time in the jail he was the senior ranked man in the so-called hospital whilst all the actual Medical officers were being held in solitary confinement. Stanley died of exhaustion complicated with beri beri on 13th May 1944. Pictured right, is his memorial plaque, as found in Rangoon War Cemetery in Burma.

Here is what Lieutenant “Willie’ Wilding, also a captured Chindit that year, had to say about Sergeant Scruton:

"He was a jewel, although he knew nothing about medicine he possessed great common sense. A bricklayer's labourer by trade, I am sure that his (Scruton's) death was at least in part, due to frustration because he could do so little for his charges. He was a splendid chap".

After the disaster of the Shweli crossing, Stanley Scruton, devastated by his part in the debacle took control of the small group of men. In his own mind he felt he was responsible for the men becoming adrift from the main section on that terrible day. Even after eventual capture by the Japanese he worked tirelessly in the makeshift hospital in Rangoon Jail, almost as though this was his way of making amends.

For a long time in the jail he was the senior ranked man in the so-called hospital whilst all the actual Medical officers were being held in solitary confinement. Stanley died of exhaustion complicated with beri beri on 13th May 1944. Pictured right, is his memorial plaque, as found in Rangoon War Cemetery in Burma.

Here is what Lieutenant “Willie’ Wilding, also a captured Chindit that year, had to say about Sergeant Scruton:

"He was a jewel, although he knew nothing about medicine he possessed great common sense. A bricklayer's labourer by trade, I am sure that his (Scruton's) death was at least in part, due to frustration because he could do so little for his charges. He was a splendid chap".

Of the original twelve men in the dinghy only five made it back that year. Of the six POW's that Sergeant Scruton so tenderly cared for, only one survived to see liberation. One man, Corporal Frederick Johnson was killed in action on the day the group met the Japanese patrol.

Stanley Scruton and the other five POW casualties were all originally buried in the English Cantonment Cemetery, located near the famous Rangoon Royal Lakes and not far from the city zoo.

After the war the Imperial War Graves Commission moved all these men to the then new Rangoon War Cemetery, where they now rest in peace. The cemetery can be seen pictured left, the majority of the Chindits in the cemetery lie at the far end close to the Stone of Remembrance.

(Photo courtesy of Tony B).

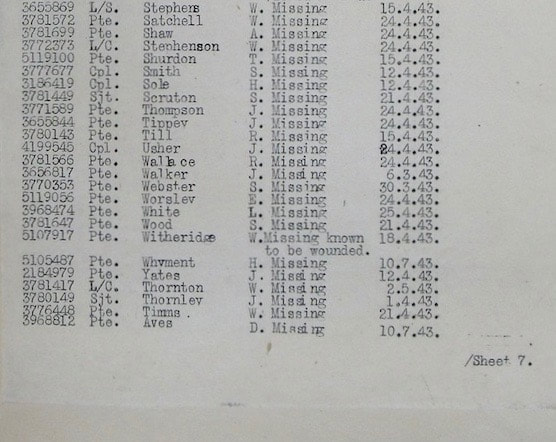

Here I believe, are the names from the "Lost Boat on the Shweli".

These include the names confirmed from the Eric Allen diary, the names on Ronald Johnson's eye witness report and subsequent paperwork leading from these documents.

This leaves Sidney Wood, verified by the same missing in action date as the others, of 21/04/1943, and therefore almost a definite member of the group.

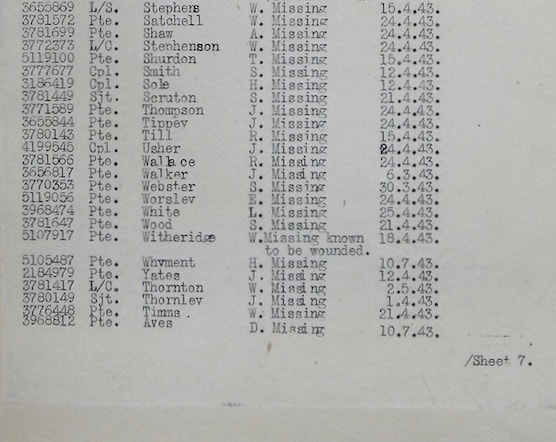

Aves, Simon and Lees all have the secondary missing date of 10/07/1943. This is the same date as Harry Whyment. Although not totally conclusive, I believe these 4 men were caught later on and separately from the others. It's too much of a coincidence that these men from column 8 all have the same missing date, with Whyment confirmed by Ron Johnson's report. The Missing in Action dates come from lists found in the 1943 War Diary of the 13th Kings, this diary can be found at the National Archives, Kew, London.

NB. Update 18/12/2015. The subsequent information found within the memoir of Henry Taylor (see link at the foot of this page), has shed further light on the personnel from the boat. This detail has helped rubber-stamp the presence of many of the men listed below, but has also called in to question whether some of the others were actually involved. I have adjusted the list accordingly.

Confirmed by one or both memoirs:

Pte. 5116737 Eric Allen.

Pte. 3714445 Henry Taylor.

Pte. J. Hoyle (who sadly died in Salford in 1989).

Pte. 3781404 Ronald Johnson (from Manchester).

Burma Rifleman 'Stanley' (ID unknown). Remembered by Henry Taylor as 'Sammy.'

Indian Orderly/Guide 'Peter.'

Sergeant 3781449 Stanley Scruton (died Rangoon Jail of beri beri).

Corporal 3781720 Frederick Johnson (killed in action Meza valley 21/04/1943).

Pte. 3776448 William Timms (died Rangoon Jail of beri beri).

Pte. 5105487 Harry Whyment (died Rangoon Jail).

Probable:

Pte. 3778786 Robert William Lees (survived Rangoon Jail). Robert's place of capture, Pinlebu, suggests that he was with the dispersal party up until the final skirmish with the Japanese in late April 1943.

Possible, but cannot be confirmed:

Pte. 5120570 Harold Simon (died Rangoon Jail of beri beri).

Pte. 3781647 Sidney Wood (died Rangoon Jail of beri beri).

Pte. 3968812 Donald Aves (died Rangoon Jail of beri beri).

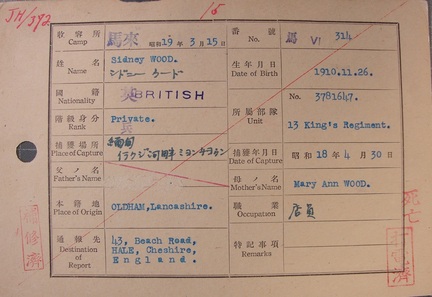

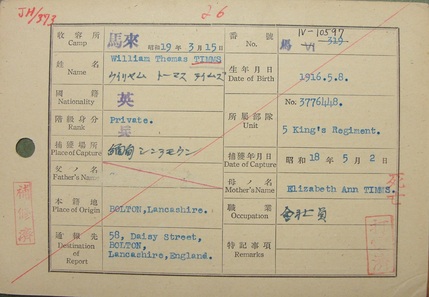

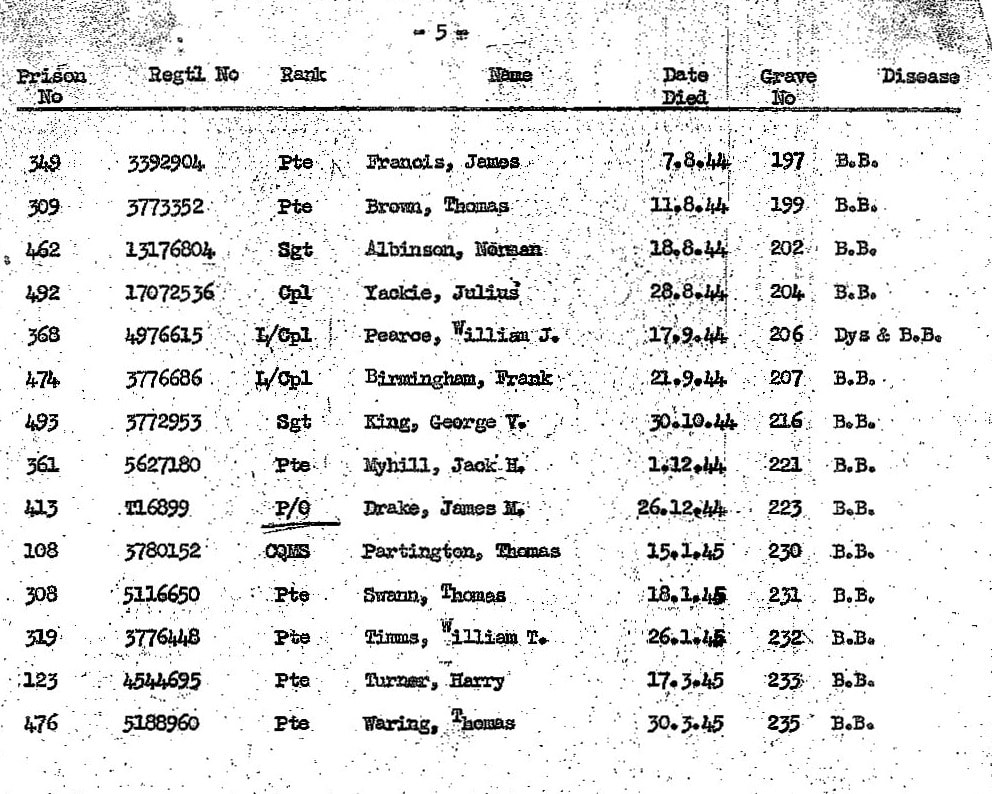

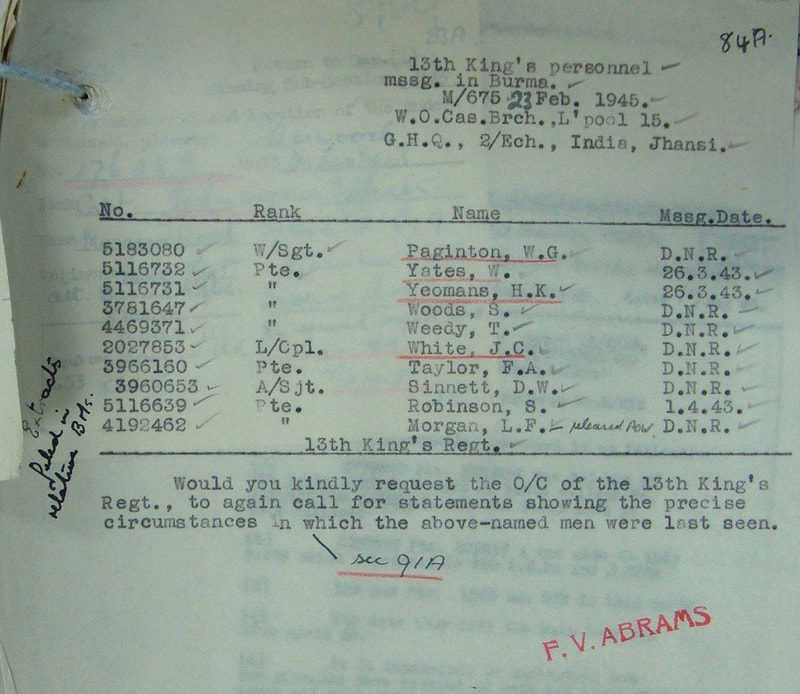

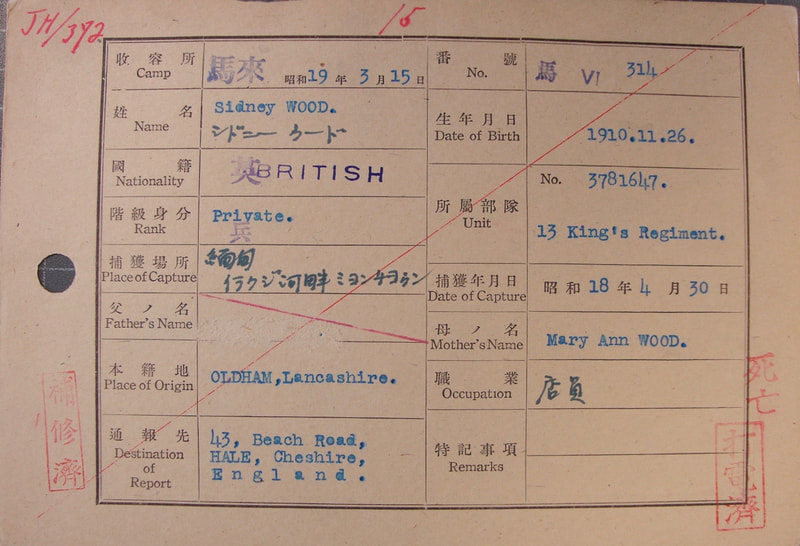

To conclude this story, see below the front images of two Japanese POW Index cards relating to Sidney Wood and William Timms. Both men seem to be captured in the same general location and with only two days separating their loss of freedom. Timms card confirms the witness report of Ronald Johnson as he (Timms) shares the same capture date as Stanley Scruton, 2nd May 1943. (Scruton's card can be seen in the Chindit POW page toward the end of the account by Alec Gibson). Nothing relating to the men of operation Longcloth can ever be assumed as being definite, but I do believe that with fair judgment and my instinctive knowledge, these were the men of the fated craft that year.

Stanley Scruton and the other five POW casualties were all originally buried in the English Cantonment Cemetery, located near the famous Rangoon Royal Lakes and not far from the city zoo.

After the war the Imperial War Graves Commission moved all these men to the then new Rangoon War Cemetery, where they now rest in peace. The cemetery can be seen pictured left, the majority of the Chindits in the cemetery lie at the far end close to the Stone of Remembrance.

(Photo courtesy of Tony B).

Here I believe, are the names from the "Lost Boat on the Shweli".

These include the names confirmed from the Eric Allen diary, the names on Ronald Johnson's eye witness report and subsequent paperwork leading from these documents.

This leaves Sidney Wood, verified by the same missing in action date as the others, of 21/04/1943, and therefore almost a definite member of the group.

Aves, Simon and Lees all have the secondary missing date of 10/07/1943. This is the same date as Harry Whyment. Although not totally conclusive, I believe these 4 men were caught later on and separately from the others. It's too much of a coincidence that these men from column 8 all have the same missing date, with Whyment confirmed by Ron Johnson's report. The Missing in Action dates come from lists found in the 1943 War Diary of the 13th Kings, this diary can be found at the National Archives, Kew, London.

NB. Update 18/12/2015. The subsequent information found within the memoir of Henry Taylor (see link at the foot of this page), has shed further light on the personnel from the boat. This detail has helped rubber-stamp the presence of many of the men listed below, but has also called in to question whether some of the others were actually involved. I have adjusted the list accordingly.

Confirmed by one or both memoirs:

Pte. 5116737 Eric Allen.

Pte. 3714445 Henry Taylor.

Pte. J. Hoyle (who sadly died in Salford in 1989).

Pte. 3781404 Ronald Johnson (from Manchester).

Burma Rifleman 'Stanley' (ID unknown). Remembered by Henry Taylor as 'Sammy.'

Indian Orderly/Guide 'Peter.'

Sergeant 3781449 Stanley Scruton (died Rangoon Jail of beri beri).

Corporal 3781720 Frederick Johnson (killed in action Meza valley 21/04/1943).

Pte. 3776448 William Timms (died Rangoon Jail of beri beri).

Pte. 5105487 Harry Whyment (died Rangoon Jail).

Probable:

Pte. 3778786 Robert William Lees (survived Rangoon Jail). Robert's place of capture, Pinlebu, suggests that he was with the dispersal party up until the final skirmish with the Japanese in late April 1943.

Possible, but cannot be confirmed:

Pte. 5120570 Harold Simon (died Rangoon Jail of beri beri).

Pte. 3781647 Sidney Wood (died Rangoon Jail of beri beri).

Pte. 3968812 Donald Aves (died Rangoon Jail of beri beri).

To conclude this story, see below the front images of two Japanese POW Index cards relating to Sidney Wood and William Timms. Both men seem to be captured in the same general location and with only two days separating their loss of freedom. Timms card confirms the witness report of Ronald Johnson as he (Timms) shares the same capture date as Stanley Scruton, 2nd May 1943. (Scruton's card can be seen in the Chindit POW page toward the end of the account by Alec Gibson). Nothing relating to the men of operation Longcloth can ever be assumed as being definite, but I do believe that with fair judgment and my instinctive knowledge, these were the men of the fated craft that year.

Update 18/12/2015.

Henry Taylor

I recently received an email via my website contact page from the son of Pte. 3714445 Henry Taylor, formerly of the 13th Battalion, the King's Liverpool Regiment and a survivor of Operation Longcloth. Kim Taylor told me:

In regards to the lost boat incident on the Shweli River; my late father was one of the occupants of this boat and walked out with another four men. These were: Pte. R. Johnson, Pte. Joseph Hoyle, Pte. E. Allen and an Indian who did all the interpreting for the party named Peter. We made an audio interview with Dad around 1999. It covers the period from him being transferred from the Lancashire Fusiliers to the King's, the voyage to India, training at Saugor and all their subsequent adventures up until the Shweli crossing. He has written all the names of his party in the fly leaf of his copy of 'Wingate's Phantom Army', by W.G. Burchett.

Kim has sent me some wonderful photographs of Henry depicting his time in India before Operation Longcloth and has been helpful in identifying several of the men from the lost boat on the Shweli. I hope soon to prepare the story of Pte. 3714445 Henry Taylor for these website pages.

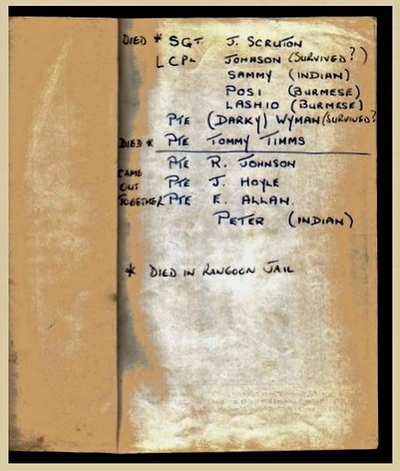

Seen below is a photograph of Henry, known to his friends as 'Harry'. Also shown is the fly leaf from Wingate's Phantom Army, listing the names of the men from the boat and their fate if known. I was pleased to see that my educated guesswork in naming the men from the boat, which I recorded at the end of Eric Allen's story, includes all of the British soldiers named by Henry on his list. Please click on either image to bring forward on the page.

Henry Taylor

I recently received an email via my website contact page from the son of Pte. 3714445 Henry Taylor, formerly of the 13th Battalion, the King's Liverpool Regiment and a survivor of Operation Longcloth. Kim Taylor told me:

In regards to the lost boat incident on the Shweli River; my late father was one of the occupants of this boat and walked out with another four men. These were: Pte. R. Johnson, Pte. Joseph Hoyle, Pte. E. Allen and an Indian who did all the interpreting for the party named Peter. We made an audio interview with Dad around 1999. It covers the period from him being transferred from the Lancashire Fusiliers to the King's, the voyage to India, training at Saugor and all their subsequent adventures up until the Shweli crossing. He has written all the names of his party in the fly leaf of his copy of 'Wingate's Phantom Army', by W.G. Burchett.

Kim has sent me some wonderful photographs of Henry depicting his time in India before Operation Longcloth and has been helpful in identifying several of the men from the lost boat on the Shweli. I hope soon to prepare the story of Pte. 3714445 Henry Taylor for these website pages.

Seen below is a photograph of Henry, known to his friends as 'Harry'. Also shown is the fly leaf from Wingate's Phantom Army, listing the names of the men from the boat and their fate if known. I was pleased to see that my educated guesswork in naming the men from the boat, which I recorded at the end of Eric Allen's story, includes all of the British soldiers named by Henry on his list. Please click on either image to bring forward on the page.

Update 27/03/2016.

As promised, here is the full story of Pte. Henry Taylor, illustrating his experiences during the first Wingate expedition and beyond:

Pte. Henry Taylor

Update 12/05/2016.

Seen below are some general images of the Shweli River and the landscape slightly north of the Wingaba Cliffs, close to where 8 Column attempted their first crossing on 1st April 1943. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

As promised, here is the full story of Pte. Henry Taylor, illustrating his experiences during the first Wingate expedition and beyond:

Pte. Henry Taylor

Update 12/05/2016.

Seen below are some general images of the Shweli River and the landscape slightly north of the Wingaba Cliffs, close to where 8 Column attempted their first crossing on 1st April 1943. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 21/05/2017.

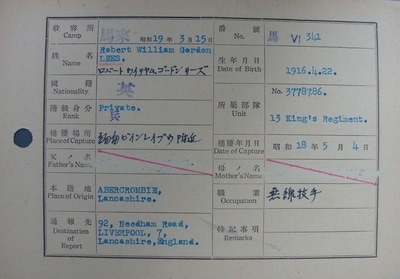

Robert William Lees

Robert William Gordon Lees was born on the 22nd April 1916 and lived at 92 Needham Road in Liverpool. Robert had been a pupil at St. Margaret's School on Aigburth Road, before enlisting into the British Army in 1940. Pte. Lees was posted to 8 Column during Chindit training in July 1942 and served with this unit in Burma. Very little is known about his time on Operation Longcloth, but his date and place of capture have always leant themselves to Robert being one of the men with Stanley Scruton, Eric Allen and the other men swept away on the Shweli on the 1st April 1943.

According to his POW index card details, Robert was captured on the 4th May 1943, close to the Burmese village of Pinlebu. This was the same village in which 8 Column had experienced their first skirmish with the Japanese back in early March and was located on the only obvious track which led back towards the Chindwin River. Pte. Lees spent just under two years as a prisoner of war in Rangoon Jail, before being liberated on the 29th April 1945 at the village of Waw on the Pegu Road. After returning to India, he spent a short period recovering from the trials of his internment in hospital at Calcutta. He then re-joined the 13th King's who were now stationed at the Napier Barracks in Karachi, before being repatriated to the UK in late 1945.

After returning to Allied territory, Robert assisted the Army investigation into the missing and lost from the first Wingate expedition, giving invaluable information about several soldiers and their last know whereabouts. Back home in Liverpool, his family had placed an announcement into the Liverpool Echo newspaper on the 30th July 1943, hoping to learn more about his disappearance in Burma. Under the headline,

Reported Missing:

Private Robert William Lees, aged 27, whose wife is living at 92 Needham Road, Liverpool 7, is missing in the Indian theatre of war. He is an old boy of St. Margaret's School in Aigburth Road and has been in the Army for three years.

Seen below is a Gallery of images in relation to this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Robert William Lees

Robert William Gordon Lees was born on the 22nd April 1916 and lived at 92 Needham Road in Liverpool. Robert had been a pupil at St. Margaret's School on Aigburth Road, before enlisting into the British Army in 1940. Pte. Lees was posted to 8 Column during Chindit training in July 1942 and served with this unit in Burma. Very little is known about his time on Operation Longcloth, but his date and place of capture have always leant themselves to Robert being one of the men with Stanley Scruton, Eric Allen and the other men swept away on the Shweli on the 1st April 1943.

According to his POW index card details, Robert was captured on the 4th May 1943, close to the Burmese village of Pinlebu. This was the same village in which 8 Column had experienced their first skirmish with the Japanese back in early March and was located on the only obvious track which led back towards the Chindwin River. Pte. Lees spent just under two years as a prisoner of war in Rangoon Jail, before being liberated on the 29th April 1945 at the village of Waw on the Pegu Road. After returning to India, he spent a short period recovering from the trials of his internment in hospital at Calcutta. He then re-joined the 13th King's who were now stationed at the Napier Barracks in Karachi, before being repatriated to the UK in late 1945.

After returning to Allied territory, Robert assisted the Army investigation into the missing and lost from the first Wingate expedition, giving invaluable information about several soldiers and their last know whereabouts. Back home in Liverpool, his family had placed an announcement into the Liverpool Echo newspaper on the 30th July 1943, hoping to learn more about his disappearance in Burma. Under the headline,

Reported Missing:

Private Robert William Lees, aged 27, whose wife is living at 92 Needham Road, Liverpool 7, is missing in the Indian theatre of war. He is an old boy of St. Margaret's School in Aigburth Road and has been in the Army for three years.

Seen below is a Gallery of images in relation to this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 21/02/2021.

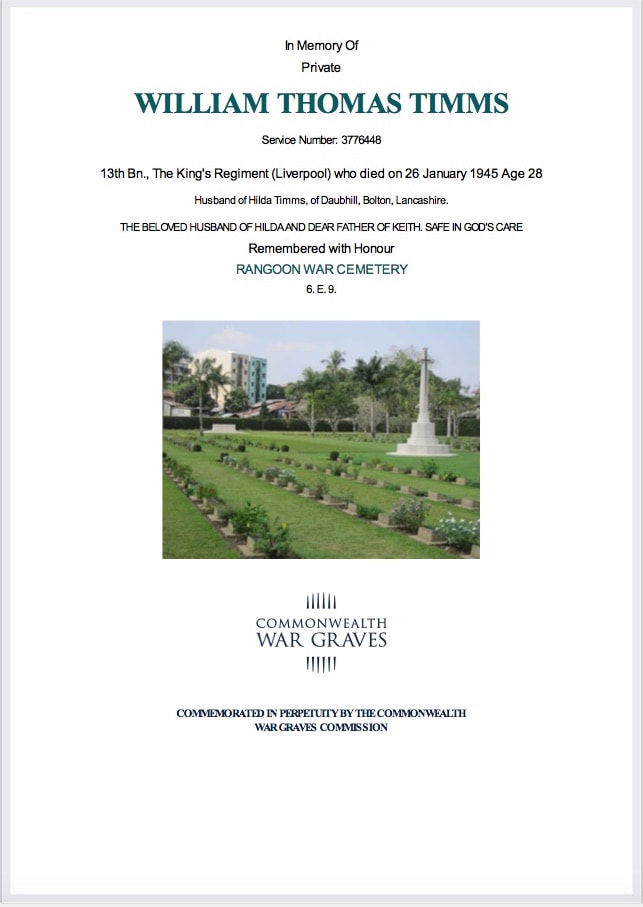

William Thomas Timms

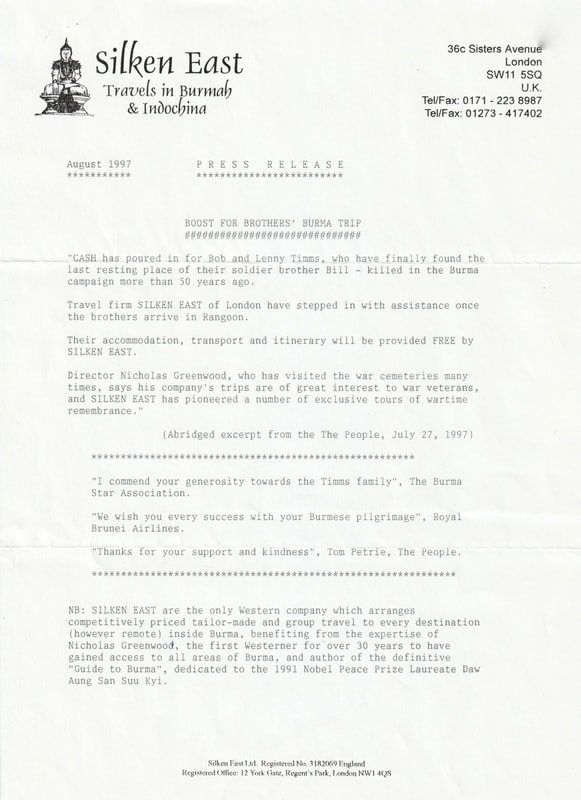

I recently received some information about the family of William Timms, in the form of an old newsletter page from a tour company called Silken East. The company, based in London no longer exists, but in 1997 they covered a story about two brothers, Robert and Leonard Timms, who had travelled to Burma to visit the grave of their other brother, William (Bill) Timms, who had been lost during the Burma campaign. The story had also been covered in the Sunday People newspaper, dated 27th July 1997.

Searching through the Commonwealth Graves website, there are in fact two men named William Timms who perished during the war in Burma and are buried in cemeteries in Rangoon. The other soldier is Pte. William Timms of the Queen's Own Royal West Kent Regiment, who died on the 10th January 1944 whilst fighting close to the Burmese town of Akyab. To read more about this soldier, please click on the link to his CWGC details here: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2088141/WILLIAM%20TIMMS/

However, I believe that the soldier referred to in the newsletter and newspaper articles is, Pte. William Thomas Timms of the 13th King's Regiment and the same man mentioned previously on these website pages.

According to documents held on line, William was born on the 8th May 1916 and was the son of Elizabeth Ann Timms and possibly, Charles Timms, a colliery worker formerly from Birmingham (1911 Census). The family lived in the Bolton area of Lancashire and in the early months of 1939, William married Hilda Davenport and the couple set up home at 58 Daisy Street, Daubhill, Bolton.

Some of William's details have already been mentioned in the main narrative above, including an image of his prisoner of war index card, which explains what happened to him during his incarceration at Rangoon Central Jail. He was given the POW number 319 at the jail and spent 20 months as a prisoner of war before his sad death on the 26th January 1945. From other documents held, we know that William perished from the effects of beri beri in Block 6 of the jail and was buried in the first instance at the English Cantonment Cemetery on the eastern outskirts of the city. Later, after the war was over, the Imperial War Graves Commission brought all of the Allied burials from this cemetery over to the newly constructed Rangoon War Cemetery and this is where William lies today.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to William Thomas Timms, including a copy of the newsletter article produced by the tour company, Silken East in August 1997. Of course, the accuracy of whether or not this does refer to Pte. William Thomas Timms of the 13th King's, balances entirely on Robert and Leonard Timms being his brothers. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

William Thomas Timms

I recently received some information about the family of William Timms, in the form of an old newsletter page from a tour company called Silken East. The company, based in London no longer exists, but in 1997 they covered a story about two brothers, Robert and Leonard Timms, who had travelled to Burma to visit the grave of their other brother, William (Bill) Timms, who had been lost during the Burma campaign. The story had also been covered in the Sunday People newspaper, dated 27th July 1997.

Searching through the Commonwealth Graves website, there are in fact two men named William Timms who perished during the war in Burma and are buried in cemeteries in Rangoon. The other soldier is Pte. William Timms of the Queen's Own Royal West Kent Regiment, who died on the 10th January 1944 whilst fighting close to the Burmese town of Akyab. To read more about this soldier, please click on the link to his CWGC details here: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2088141/WILLIAM%20TIMMS/

However, I believe that the soldier referred to in the newsletter and newspaper articles is, Pte. William Thomas Timms of the 13th King's Regiment and the same man mentioned previously on these website pages.

According to documents held on line, William was born on the 8th May 1916 and was the son of Elizabeth Ann Timms and possibly, Charles Timms, a colliery worker formerly from Birmingham (1911 Census). The family lived in the Bolton area of Lancashire and in the early months of 1939, William married Hilda Davenport and the couple set up home at 58 Daisy Street, Daubhill, Bolton.

Some of William's details have already been mentioned in the main narrative above, including an image of his prisoner of war index card, which explains what happened to him during his incarceration at Rangoon Central Jail. He was given the POW number 319 at the jail and spent 20 months as a prisoner of war before his sad death on the 26th January 1945. From other documents held, we know that William perished from the effects of beri beri in Block 6 of the jail and was buried in the first instance at the English Cantonment Cemetery on the eastern outskirts of the city. Later, after the war was over, the Imperial War Graves Commission brought all of the Allied burials from this cemetery over to the newly constructed Rangoon War Cemetery and this is where William lies today.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to William Thomas Timms, including a copy of the newsletter article produced by the tour company, Silken East in August 1997. Of course, the accuracy of whether or not this does refer to Pte. William Thomas Timms of the 13th King's, balances entirely on Robert and Leonard Timms being his brothers. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 07/11/2021.

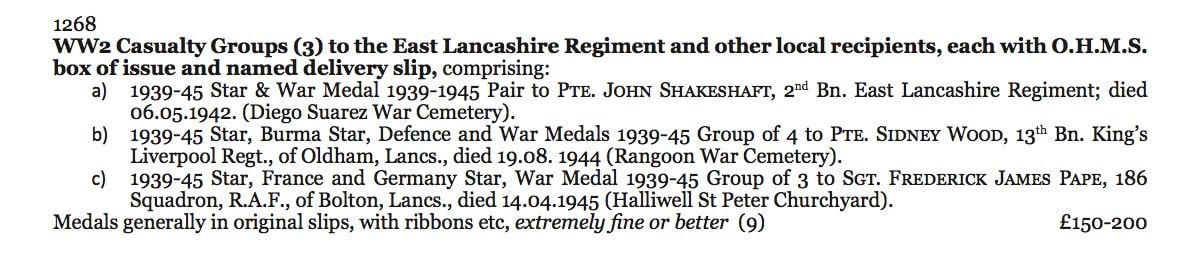

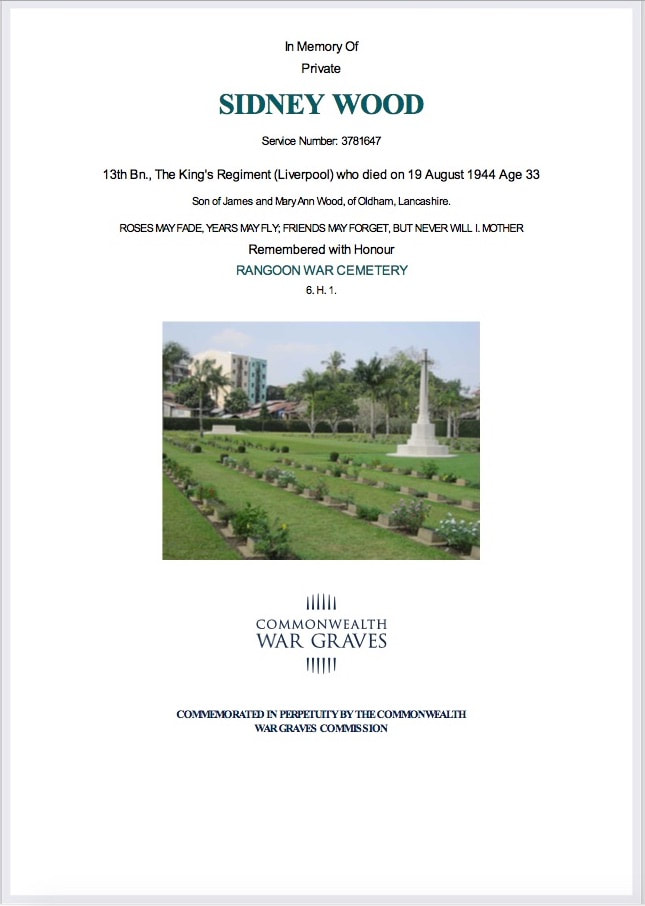

Sidney Wood

In the Morton & Eden auction catalogue, Medals, Orders and Decorations November 2021, I found listed the WW2 entitlement of Pte. Sidney Wood, 13th Battalion, the King's Regiment. In normal circumstances I would have thought seriously about bidding for the medals, but unfortunately they were listed as a three part lot which included the medals of two other casualties from WW2. However, the emergence of Sidney's medals in this way, provoked me to update his story on my website, as far as it is known.

Sidney Wood

In the Morton & Eden auction catalogue, Medals, Orders and Decorations November 2021, I found listed the WW2 entitlement of Pte. Sidney Wood, 13th Battalion, the King's Regiment. In normal circumstances I would have thought seriously about bidding for the medals, but unfortunately they were listed as a three part lot which included the medals of two other casualties from WW2. However, the emergence of Sidney's medals in this way, provoked me to update his story on my website, as far as it is known.

Pte. 3781647 Sidney Wood was born on the 26th November 1910 and was the son of James and Mary Ann Wood from Oldham in Lancashire. It is likely that he travelled to India with the 13th battalion aboard the troopship Oronsay, leaving British shores on the 8th December 1941. Sidney was posted to No. 8 Column during the Chindit training period at Saugor in the Central Provinces of India and entered Burma with this unit in February 1943.

Very little is known about his time behind Japanese lines, but it seems likely that he was part of the group who were lost crossing the Shweli River on the 1st April 1943 as described in the main story above. Sidney was listed as officially missing on the 21st April and then captured by the Japanese on the 30th April at a village on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River. He was eventually sent to Rangoon Central Jail where he resided with the other Chindit prisoners in Block 6 of the jail. Whilst at Rangoon, Sidney was allocated the POW number 314.

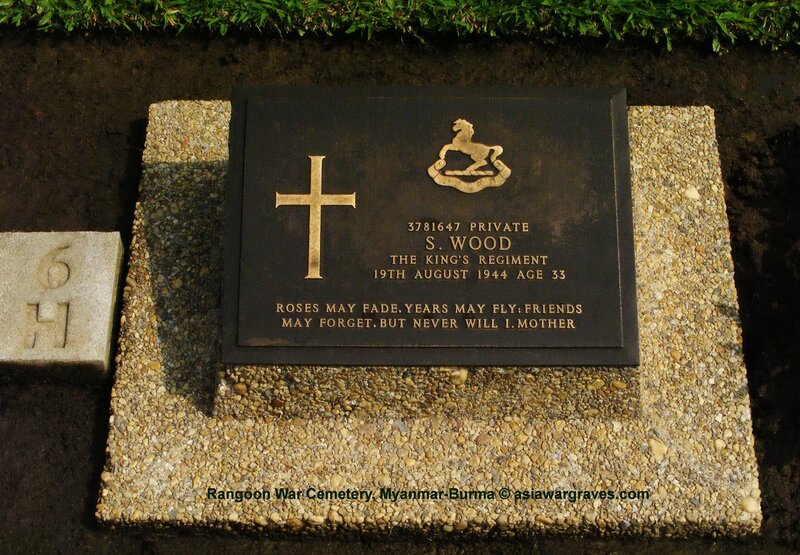

Sadly, Sidney died in Rangoon Jail on the 19th August 1944 from the effects of the disease, beri beri. He was buried in the first instance at the English Cantonment Cemetery (grave no. 203) located on the eastern side of the city, close to the Royal Lakes. After the war was over, the Imperial War Graves Commission moved all burials from the Cantonment Cemetery to the newly constructed Rangoon War Cemetery, with Sidney's remains making this journey on the 22nd January 1947.

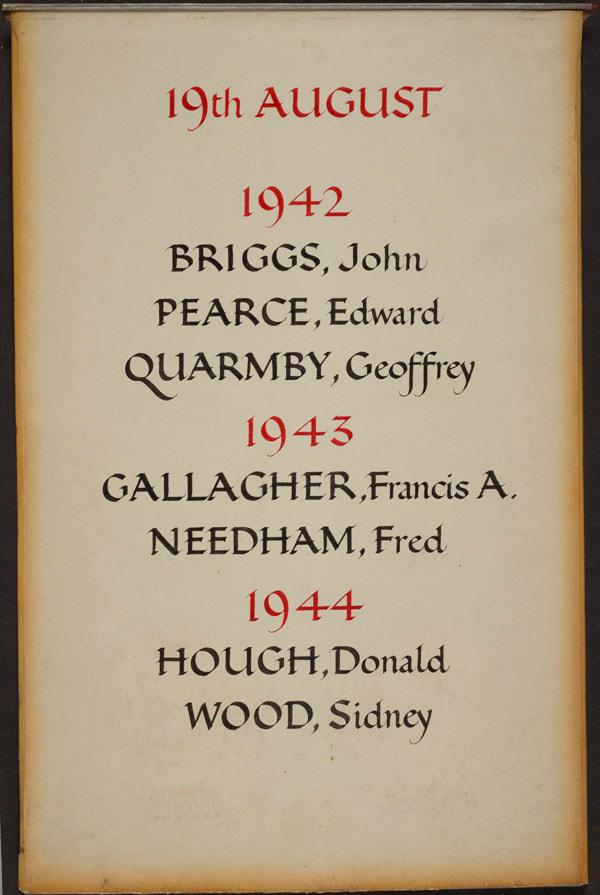

Sidney lies at Rangoon War Cemetery to this day in grave no. 6.H.1 and alongside many of his Chindit comrades. He is also remembered back home in Oldham, on the town's WW2 Roll of Honour. This comes in the form of an ornate book which is displayed in the town's main War Memorial located close to St. Mary's Church and the old town hall building. The book is contained within the memorial behind a glass window, with each page being turned chronologically during the year.

To view Sidney's details on the Commonwealth Graves website, please click on the following link:

www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2261427/sidney-wood/

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this short update, including an image of Sidney's POW index card and a photograph of his grave at Rangoon War Cemetery. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Very little is known about his time behind Japanese lines, but it seems likely that he was part of the group who were lost crossing the Shweli River on the 1st April 1943 as described in the main story above. Sidney was listed as officially missing on the 21st April and then captured by the Japanese on the 30th April at a village on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River. He was eventually sent to Rangoon Central Jail where he resided with the other Chindit prisoners in Block 6 of the jail. Whilst at Rangoon, Sidney was allocated the POW number 314.

Sadly, Sidney died in Rangoon Jail on the 19th August 1944 from the effects of the disease, beri beri. He was buried in the first instance at the English Cantonment Cemetery (grave no. 203) located on the eastern side of the city, close to the Royal Lakes. After the war was over, the Imperial War Graves Commission moved all burials from the Cantonment Cemetery to the newly constructed Rangoon War Cemetery, with Sidney's remains making this journey on the 22nd January 1947.

Sidney lies at Rangoon War Cemetery to this day in grave no. 6.H.1 and alongside many of his Chindit comrades. He is also remembered back home in Oldham, on the town's WW2 Roll of Honour. This comes in the form of an ornate book which is displayed in the town's main War Memorial located close to St. Mary's Church and the old town hall building. The book is contained within the memorial behind a glass window, with each page being turned chronologically during the year.

To view Sidney's details on the Commonwealth Graves website, please click on the following link:

www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2261427/sidney-wood/

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this short update, including an image of Sidney's POW index card and a photograph of his grave at Rangoon War Cemetery. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 14/01/2023.

Ronald Johnson

In the act of re-reading some of my books about the first Wingate expedition, I stumbled across the following passage in regards Pte. Ronald Johnson, one of the soldiers mentioned as being with Eric Allen on the return journey back to India. From the pages of Wingate's Adventure by war correspondent, Wilfred Burchett:

After attempting to cross the fast-flowing Irrawaddy at this point, the first RAF dinghy went out into the river. The men pulled the boat hand-over-hand fighting the strong current, when suddenly there was a cry from mid-stream, the end of the rope hung loose and the helpless dinghy went slipping away downstream. There was nothing that could be done. The rope had broken and Major Scott had no way of rescuing the men.

In actual fact the lost dinghy was eventually swept onto the opposite bank, but many miles away from the desired landing point. A Manchester lad, Ronald Johnson, took charge of the party of twelve men. He tried to catch up with the other group but failed. With a training compass to guide him and a Burma Rifles Medical Sergeant to interrupt and scrounge for food at villages along the way, Johnson steered a course due west fro India. When they lost their compass after a brush with the Japs, he steered by the sun. At first they had to lay up on cloudy days, but later Johnson learned to line distant hills and tree tops at each sunset and was able to set a course for the next day come sunshine or rain. In the end, he brought most of his party safely through to India.

Ronald Johnson

In the act of re-reading some of my books about the first Wingate expedition, I stumbled across the following passage in regards Pte. Ronald Johnson, one of the soldiers mentioned as being with Eric Allen on the return journey back to India. From the pages of Wingate's Adventure by war correspondent, Wilfred Burchett:

After attempting to cross the fast-flowing Irrawaddy at this point, the first RAF dinghy went out into the river. The men pulled the boat hand-over-hand fighting the strong current, when suddenly there was a cry from mid-stream, the end of the rope hung loose and the helpless dinghy went slipping away downstream. There was nothing that could be done. The rope had broken and Major Scott had no way of rescuing the men.

In actual fact the lost dinghy was eventually swept onto the opposite bank, but many miles away from the desired landing point. A Manchester lad, Ronald Johnson, took charge of the party of twelve men. He tried to catch up with the other group but failed. With a training compass to guide him and a Burma Rifles Medical Sergeant to interrupt and scrounge for food at villages along the way, Johnson steered a course due west fro India. When they lost their compass after a brush with the Japs, he steered by the sun. At first they had to lay up on cloudy days, but later Johnson learned to line distant hills and tree tops at each sunset and was able to set a course for the next day come sunshine or rain. In the end, he brought most of his party safely through to India.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and Peter and Clare Hale 2011.