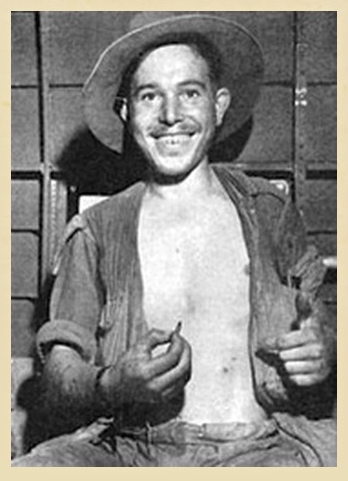

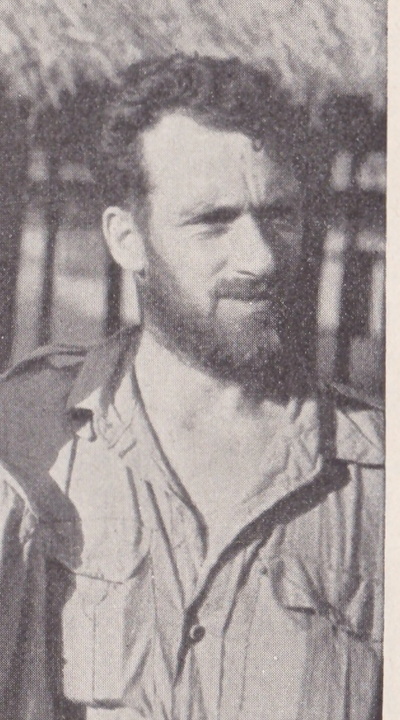

Pte. Henry Taylor, a survivor from the Lost Boat on the Shweli

Cap badge of the King's Own Royal Regiment.

Cap badge of the King's Own Royal Regiment.

In November 2015, I received an email via my website contact page from the son of Pte. 3714445 Henry Taylor, formerly of the 13th Battalion, the King's Liverpool Regiment and a survivor of Operation Longcloth. Kim Taylor told me:

In regards to the lost boat incident on the Shweli River; my late father was one of the occupants of this boat and walked out with another four men. These were: Pte. R. Johnson, Pte. Joseph Hoyle, Pte. E. Allen and an Indian who did all the interpreting for the party named Peter. We made an audio interview with Dad around 1999. It covers the period from him being transferred from the Lancashire Fusiliers to the King's, the voyage to India, training at Saugor and all their subsequent adventures up until the Shweli crossing. He has written all the names of his party in the fly leaf of his copy of 'Wingate's Phantom Army', by W.G. Burchett.

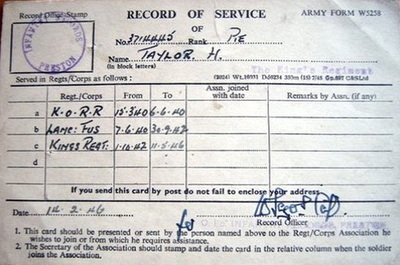

After his enlistment into the British Army, Henry Taylor was posted to the King's Own Royal Regiment in March 1940, before being transferred to the Lancashire Fusiliers just three months later in June that same year. In the late summer of 1942, Henry was sent overseas to India, where he was once again transferred, this time to the 13th Battalion of the King's Liverpool Regiment. He spent the rest of the war with the King's Regiment, which included taking part on Operation Longcloth as part of No. 18 Platoon in Major Scott's 8 Column.

As mentioned in Kim Taylor's email, Henry was with the group of men washed away downstream, when a boat was cut loose whilst crossing the Shweli River in April 1943. This story has already featured within these website pages and can be read here: Eric Allen and the Lost Boat on the Shweli

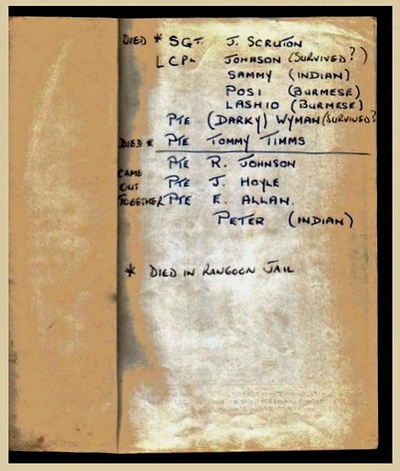

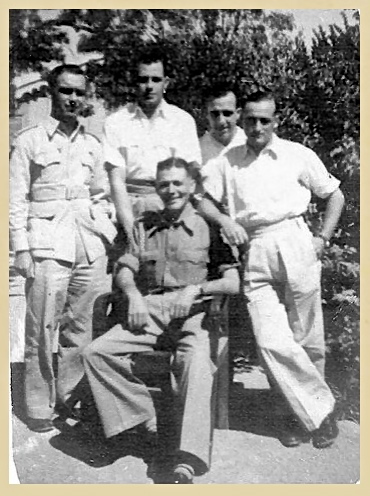

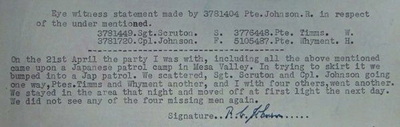

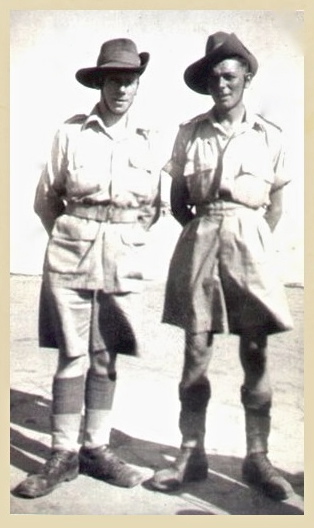

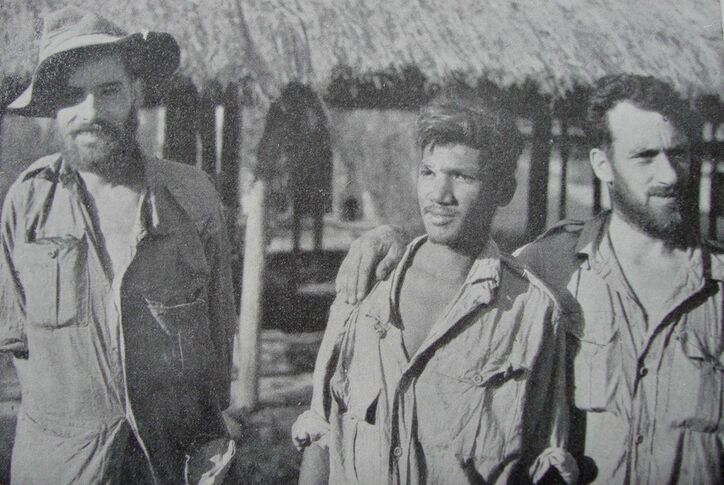

Seen below is a photograph of Henry, known to his friends, family and from now on within these pages as 'Harry'. Also shown is the fly leaf from his copy of Wingate's Phantom Army, listing the names of the men from the boat and their fate as Harry remembered it. I was pleased to see that my educated guesswork in naming the men from the boat, which I recorded at the end of Eric Allen's story, included all of the British soldiers named by Harry on his list. It was extremely interesting to read the names of the Indian and Burmese members of the group, as soldiers from the Burma Rifles and Indian Service Corps are rarely mentioned in books or official paperwork. Please click on either image to bring forward on the page.

In regards to the lost boat incident on the Shweli River; my late father was one of the occupants of this boat and walked out with another four men. These were: Pte. R. Johnson, Pte. Joseph Hoyle, Pte. E. Allen and an Indian who did all the interpreting for the party named Peter. We made an audio interview with Dad around 1999. It covers the period from him being transferred from the Lancashire Fusiliers to the King's, the voyage to India, training at Saugor and all their subsequent adventures up until the Shweli crossing. He has written all the names of his party in the fly leaf of his copy of 'Wingate's Phantom Army', by W.G. Burchett.

After his enlistment into the British Army, Henry Taylor was posted to the King's Own Royal Regiment in March 1940, before being transferred to the Lancashire Fusiliers just three months later in June that same year. In the late summer of 1942, Henry was sent overseas to India, where he was once again transferred, this time to the 13th Battalion of the King's Liverpool Regiment. He spent the rest of the war with the King's Regiment, which included taking part on Operation Longcloth as part of No. 18 Platoon in Major Scott's 8 Column.

As mentioned in Kim Taylor's email, Henry was with the group of men washed away downstream, when a boat was cut loose whilst crossing the Shweli River in April 1943. This story has already featured within these website pages and can be read here: Eric Allen and the Lost Boat on the Shweli

Seen below is a photograph of Henry, known to his friends, family and from now on within these pages as 'Harry'. Also shown is the fly leaf from his copy of Wingate's Phantom Army, listing the names of the men from the boat and their fate as Harry remembered it. I was pleased to see that my educated guesswork in naming the men from the boat, which I recorded at the end of Eric Allen's story, included all of the British soldiers named by Harry on his list. It was extremely interesting to read the names of the Indian and Burmese members of the group, as soldiers from the Burma Rifles and Indian Service Corps are rarely mentioned in books or official paperwork. Please click on either image to bring forward on the page.

I am very grateful to Kim, for allowing me to include a transcription of his father's audio memoir as part of this story. I have made some minor changes to the script where appropriate and have added some annotated notes, which I hope will supplement the information found within Harry's narrative, otherwise, it is presented just as he described.

Update 19/01/2019

Whilst searching through the Imperial War Museum website, I was delighted to stumble upon Harry Taylor's audio memoir which is the basis for the narrative below. If you would like to listen to the audio then simply click on the link below:

www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80027143

The WW2 Diary of Pte. Harry Taylor

We were up near Hull at Hornsea, a little seaside place and we were billeted in a schoolroom when they first started taking drafts; Harold Hall was on one of the first ones to leave and I volunteered to go with him because we’d been mates for such a long time, but they wouldn’t let me go with being the company barber and they kept me till the last. I was on one of the last drafts to come from Hornsea and we went to Liverpool, the Formby Barracks, I always remember there were guards on the gates so we couldn’t get out and everybody was confined to barrack’s.

I think it was Thursday or Friday afternoon and we were all waiting to join the convoy to go abroad. Not being so far from Preston, I thought, well if I can get out for a couple of days, they wouldn’t have let me go out officially, so I thought well I’ll try and get out on my own. I always remember it was Sunday morning and there was what looked like to me an oldish bloke, he’d only be about forty, an old soldier dishing slices of bread out, and after I’d had my breakfast he came round clearing tables, so I said, “can you tell me if there’s a way out?” He said “what for” and I said, “well I want to get home” and he said, “wait while I’ve finished and I’ll be over in that corner waiting for you.”

So that’s what happened, he took me outside and there was a built in thing like a shelter, full of timber and at the back of this timber there was a stone wall about fifteen foot high. He said, “if you can climb up there and down the other side, then there’s a row of houses and they’ve been bombed and there all empty, walk along the alleyway and you’ll find there’s an entrance onto the main road and from there happen you’ll get a bus or thumb a lift, and don’t forget I haven’t told you. If you’re coming back you’ll have to come that way too because the gates are locked.”

So I climbed up this wall and down the other side, and made my way to the main road like he said and put my thumb up because there were a van coming, a little navy blue van and they always stopped in them days for anybody in uniform and it were a milk fella, he said “were do you want to go,” I said, Preston and he said “I’m not going there but I can take you as far as the Golden Ball at Longton.” I said, “that’ll do me, from Longton I’ll get another lift,” so that’s were he dropped me off and I got a lift off another bloke and he dropped me off at the bottom of Fishergate Hill.

So when I reached home Mummy said, “how long have you got” and I said, “well two or three days” and I think it was Thursday when I set off back. I didn’t go to the bus station; I caught the bus at the bottom of Fishergate Hill because the Railway station and Bus station were always full of Redcaps[1].

I got on this Liverpool bus and it was a woman conductor and I said, “I want Formby Barracks but I don’t know where to get off.” She said, “Oh do you,” I think see twigged it that I was on the run. She said, “well when the bus gets there I’ll come and tell you,” I was giving her the money and she winked at me and gave me a ticket and I thought “what a kind soul.”

So, where she dropped me off, it was only five minutes walk and I was back in the bombed houses. I got over the wall and down the other side and there was nobody knocking about, I thought, “where the hell have they all gone”. I’d only been there from the week before and I couldn’t find anything I recognised, every hut looked like another and I didn’t know which one I was in, all the huts were empty, no kit and nobody in them at all.

I’d looked in two or three more huts and I came out of one and saw an officer coming up. He said, “and what do you want,” I said, “I’m looking for such and such a platoon.” He said “Oh, I think your one of this group, you’d better go to the guard room, there’s twenty odd of you there.”

So I went to the guardroom and there they were, and I made the number up to twenty-three. That’s where I met Bill Davis, the one who was wounded in the arm[2].

The morning after, a coach came and there was a Brigadier there, a little fat fella getting on in years and two MPs and only one way on and one way off, no back door or anything like that. They formed the twenty three of us up and stood us to attention and the Brigadier said, “lets see, you’ve been away three days I know that” he said, “did you enjoy it.” Well nobody moved did they and he said, “I’ll ask you again, answer me, did you enjoy it?” And they all said “aye” then he said, “look, think yourselves lucky, your going to get away with it, we aren’t charging you because the convoy is forming up now and the boat your going on is still in dock, now get on that bloody bus and don’t get any more fresh ideas and good luck to you.”

So off we go on the coach with the two Redcaps on the door so nobody could get off, down to, I think it was Albert Dock but I’m not sure. As we were going on board they gave us a ticket with a cabin number on it with four to a cabin, when we got in it was lovely, four bunks, a porthole and nice, thick white fluffy blankets. I think we’d been on board about two days when a Sergeant came and said, “what lot are you in” and I said he Lancashire Fusiliers. He said, “pack away your gear, don’t leave anything behind and go down to C Deck, they’ll show you were to go from there."

So, we all went out and the blokes who were taking over from us were stood there waiting and guess what Regiment they were in, the bloody Pay Corps and as we marched out they marched in and took our beds off us, we ended up in hammocks, and when I say hammocks there was about a foot of space between each one and not only hammocks, some slept on the floor and some slept on the dining room tables which were about twelve foot long, so you could get two on top.

When we got to the tropical climate it was too warm, so I slept on deck near the steam winches, but there was a bit of a snag, because at four in the morning they came round and hosed the decks down, I suppose it was to stop the timbers from shrinking. They didn’t warn you, they probably thought, “if we give them a good soaking they won’t come again.”

The toilets were up on deck for everyone, they were cabins. It was dark when you walked in there, with no lights, they were forbidden; inside there was a line of toilets down one wall and showers down the other. When you had a shower you pulled a chain and as the water came out it was phosphorescent and lit everything up with a green light and when you looked out to sea all the tips of the waves were green. About two days out if I remember it right, one of the cooks died. The ship sailed a zigzag course which you could follow on a map, but only the previous days progress. The first port we called at was Freetown[3] to take on water and fresh fruit and vegetables and the local youngsters, some as young as four or five would dive for pennies, they’d come up with them in their teeth to show you.

[1] The soldiers nickname for the British Military Police.

[2] Harry is referring to Pte. William Davis from Croston near Preston, who was wounded in the arm whilst with 8 Column in Burma.

[3] This was Freetown, Sierra Leone, very often the first stop on a voyage to the Far East. Here the troopships would re-stock with fresh supplies, but no shore leave was permitted for the men.

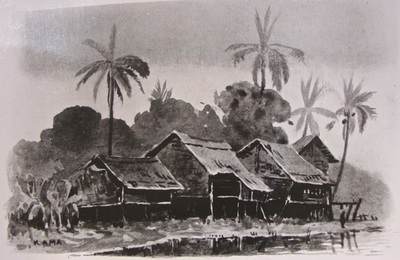

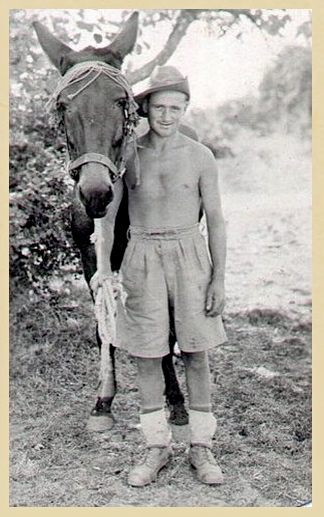

Seen below are some photographs in relation to the first part of Harry Taylor's story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 19/01/2019

Whilst searching through the Imperial War Museum website, I was delighted to stumble upon Harry Taylor's audio memoir which is the basis for the narrative below. If you would like to listen to the audio then simply click on the link below:

www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80027143

The WW2 Diary of Pte. Harry Taylor

We were up near Hull at Hornsea, a little seaside place and we were billeted in a schoolroom when they first started taking drafts; Harold Hall was on one of the first ones to leave and I volunteered to go with him because we’d been mates for such a long time, but they wouldn’t let me go with being the company barber and they kept me till the last. I was on one of the last drafts to come from Hornsea and we went to Liverpool, the Formby Barracks, I always remember there were guards on the gates so we couldn’t get out and everybody was confined to barrack’s.

I think it was Thursday or Friday afternoon and we were all waiting to join the convoy to go abroad. Not being so far from Preston, I thought, well if I can get out for a couple of days, they wouldn’t have let me go out officially, so I thought well I’ll try and get out on my own. I always remember it was Sunday morning and there was what looked like to me an oldish bloke, he’d only be about forty, an old soldier dishing slices of bread out, and after I’d had my breakfast he came round clearing tables, so I said, “can you tell me if there’s a way out?” He said “what for” and I said, “well I want to get home” and he said, “wait while I’ve finished and I’ll be over in that corner waiting for you.”

So that’s what happened, he took me outside and there was a built in thing like a shelter, full of timber and at the back of this timber there was a stone wall about fifteen foot high. He said, “if you can climb up there and down the other side, then there’s a row of houses and they’ve been bombed and there all empty, walk along the alleyway and you’ll find there’s an entrance onto the main road and from there happen you’ll get a bus or thumb a lift, and don’t forget I haven’t told you. If you’re coming back you’ll have to come that way too because the gates are locked.”

So I climbed up this wall and down the other side, and made my way to the main road like he said and put my thumb up because there were a van coming, a little navy blue van and they always stopped in them days for anybody in uniform and it were a milk fella, he said “were do you want to go,” I said, Preston and he said “I’m not going there but I can take you as far as the Golden Ball at Longton.” I said, “that’ll do me, from Longton I’ll get another lift,” so that’s were he dropped me off and I got a lift off another bloke and he dropped me off at the bottom of Fishergate Hill.

So when I reached home Mummy said, “how long have you got” and I said, “well two or three days” and I think it was Thursday when I set off back. I didn’t go to the bus station; I caught the bus at the bottom of Fishergate Hill because the Railway station and Bus station were always full of Redcaps[1].

I got on this Liverpool bus and it was a woman conductor and I said, “I want Formby Barracks but I don’t know where to get off.” She said, “Oh do you,” I think see twigged it that I was on the run. She said, “well when the bus gets there I’ll come and tell you,” I was giving her the money and she winked at me and gave me a ticket and I thought “what a kind soul.”

So, where she dropped me off, it was only five minutes walk and I was back in the bombed houses. I got over the wall and down the other side and there was nobody knocking about, I thought, “where the hell have they all gone”. I’d only been there from the week before and I couldn’t find anything I recognised, every hut looked like another and I didn’t know which one I was in, all the huts were empty, no kit and nobody in them at all.

I’d looked in two or three more huts and I came out of one and saw an officer coming up. He said, “and what do you want,” I said, “I’m looking for such and such a platoon.” He said “Oh, I think your one of this group, you’d better go to the guard room, there’s twenty odd of you there.”

So I went to the guardroom and there they were, and I made the number up to twenty-three. That’s where I met Bill Davis, the one who was wounded in the arm[2].

The morning after, a coach came and there was a Brigadier there, a little fat fella getting on in years and two MPs and only one way on and one way off, no back door or anything like that. They formed the twenty three of us up and stood us to attention and the Brigadier said, “lets see, you’ve been away three days I know that” he said, “did you enjoy it.” Well nobody moved did they and he said, “I’ll ask you again, answer me, did you enjoy it?” And they all said “aye” then he said, “look, think yourselves lucky, your going to get away with it, we aren’t charging you because the convoy is forming up now and the boat your going on is still in dock, now get on that bloody bus and don’t get any more fresh ideas and good luck to you.”

So off we go on the coach with the two Redcaps on the door so nobody could get off, down to, I think it was Albert Dock but I’m not sure. As we were going on board they gave us a ticket with a cabin number on it with four to a cabin, when we got in it was lovely, four bunks, a porthole and nice, thick white fluffy blankets. I think we’d been on board about two days when a Sergeant came and said, “what lot are you in” and I said he Lancashire Fusiliers. He said, “pack away your gear, don’t leave anything behind and go down to C Deck, they’ll show you were to go from there."

So, we all went out and the blokes who were taking over from us were stood there waiting and guess what Regiment they were in, the bloody Pay Corps and as we marched out they marched in and took our beds off us, we ended up in hammocks, and when I say hammocks there was about a foot of space between each one and not only hammocks, some slept on the floor and some slept on the dining room tables which were about twelve foot long, so you could get two on top.

When we got to the tropical climate it was too warm, so I slept on deck near the steam winches, but there was a bit of a snag, because at four in the morning they came round and hosed the decks down, I suppose it was to stop the timbers from shrinking. They didn’t warn you, they probably thought, “if we give them a good soaking they won’t come again.”

The toilets were up on deck for everyone, they were cabins. It was dark when you walked in there, with no lights, they were forbidden; inside there was a line of toilets down one wall and showers down the other. When you had a shower you pulled a chain and as the water came out it was phosphorescent and lit everything up with a green light and when you looked out to sea all the tips of the waves were green. About two days out if I remember it right, one of the cooks died. The ship sailed a zigzag course which you could follow on a map, but only the previous days progress. The first port we called at was Freetown[3] to take on water and fresh fruit and vegetables and the local youngsters, some as young as four or five would dive for pennies, they’d come up with them in their teeth to show you.

[1] The soldiers nickname for the British Military Police.

[2] Harry is referring to Pte. William Davis from Croston near Preston, who was wounded in the arm whilst with 8 Column in Burma.

[3] This was Freetown, Sierra Leone, very often the first stop on a voyage to the Far East. Here the troopships would re-stock with fresh supplies, but no shore leave was permitted for the men.

Seen below are some photographs in relation to the first part of Harry Taylor's story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Harry continues with his diary:

I think we were only there (Freetown) one day before we sailed for Cape Town[1], now that was well organised; the day after we docked, there were coaches and private cars to pick us up and run us about, they took us up Table Mountain and we went to the Beach Hotel, which was all laid out with tables full of stuff which was rationed at home, so we all had a right good feast.

Then the bar opened for a free half-hour, well some of them but not me, were on the short stuff weren’t they and had a right good time. Anyhow after about three or four days we left Cape Town and we hadn’t been at sea very long when a terrible storm came on, we daren’t go on deck for about three days, one chap was scalded badly when going down a ladder with a bucket of tea. Then we docked at Bombay and we were straight off and on a train down to Deolali[2] and I think we were there about a couple of weeks. There were no parades or anything, I think they were letting us get acclimatised, we were just eating and lying down, I think we stayed there about two weeks and then we went back on the train to Bombay and from Bombay to Saugor in the Central Provinces.

We got off the train and a bloke met us on a charger, it was night-time, we didn’t know where we were going and after a forced march with dust flying everywhere we came to Saugor village. Now Saugor village wasn’t a big place, but there was a cinema there and we used to go the few days we were at Saugor and they were all cowboy pictures, nowt but cowboys, Tom Mix and that lot. I cant remember how long we stayed there before we marched off into the jungle and that’s when our training started which mainly consisted of map and compass use, moving silently and mostly forced marches to harden us up, we hadn’t got mules then so it was mostly marching.

It was while we were at Saugor[3] and coming back after a march, that the Sergeant Major got down on one knee and fired and killed a deer as big as a mule, it took four blokes to carry it, they didn’t get back to camp until the next day, he wasn’t very popular. The grub we got was mostly deer or goat meat, but whatever we got there were always onions with it, apparently Wingate loved his onions, he always had some with him I think he thought they kept disease away, whether it did or not I don’t know. For breakfast it was always porridge, I know it wasn’t egg and bacon, I didn’t put any weight on, I was still my usual just over nine stone.

From Saugor we went to a place called Jhansi[4] where we were under canvas and we were finishing training and that’s when the mules came, it must have been December just coming up to Christmas. We went down to the railway station to get these mules and it was just like a rodeo with their back legs flying all over the place, we had a terrible day. Now with mules, even when they’d quietened down you could never trust them, you’d be walking along and they’d try and sit down. I had one I called Mollie for about a month, I’d unloaded it and put a halter on it and as I turned round it must have smelt water because it shot off and I had to let the halter go because it was burning my hand, when I finally caught it up, it was stood there having a drink.

The chargers were lovely horses, the officers used them for going to meetings, but they didn’t last as long as the mules. One day (whilst in Burma) I was following Bill Satchell[5] who was a groom and was leading one which was getting over a tree trunk when it gave a groan and dropped dead. At the beginning of the day it took about five of us to get the load on and when you were loading a mule you always got the girth strap, pulled it tight and brought your knee up into its stomach and then, as they gasped for breath got an extra couple of holes, then the load wouldn’t slip round.

I remember on one supply drop, I went out to collect some stuff and after the third trip I turned round and the rest had gone into the jungle and I was alone when the saddle slipped round and I weren’t half in it. Lucky for me Mollie was pretty quiet by now and just stood there and didn’t try to run away, so I’d no trouble with it, but I couldn’t get the load back up on my own. As I’m trying, a Ghurka came up, his mule was loaded up and he could see what had happened so he helped me take the load off, put the saddle back on and load up again. He couldn’t speak English, but he beckoned me to follow him, and by this time it was going dark and we’d no idea were the rest had gone.

We used to tie a piece of parachute cloth to the mule’s tail so you could see it bobbing up and down in the dark. So I’m following this thing and I don’t know how he knew where he were going, whether he could smell them or not, but we walked for a long, long way and eventually caught up with the column. By this time they’d stopped and were bedding down for the night and the Sergeant said, unload the mules, get down and get some sleep and pointed to a bit of a clearing. Anyway I tied the mule up and got down, I used to sleep with my head under the saddle and it wasn’t long before it was coming light again and as I woke and looked about I could see some skeletons around me. There must have been fourteen or fifteen altogether, one was sat up against a tree had a bullet hole through the forehead, they’d all been shot, quite a few of the lads came to look at them, we thought they might have been evacuees fleeing from the Japs the year before.

Picking loads up on a supply drop, you had to be quick and get back in because you were always out in the open. What they used to do for these drops was light four bonfires in a box formation and as the planes came over they’d see the smoke and come in once to make sure everything was ok, then come round again and make the first drop which was ammunition with red parachutes; rations were always the last. When you got your rations, which were for ten days of course, not knowing when you were going to get the next lot you made them last longer than ten days.

It was at Jhansi we got our new equipment, the best thing was a frame with a pack they were called Everest frames. You could put your big pack on it and your small one as well, on the side your water bottle and your Dah[6], the frame kept it all off your back by a couple of inches so the air could circulate. They were really comfortable to have on, especially as you were carrying all that weight[7], and when you sat down it was grand, we just undid the belt buckle and it was just like sitting in a chair, there were also a couple of loops to put your thumbs in.

The boots were standard Army boots, but we were also issued with what they called patrol boots, which were like a suede material, they came up the calf about eight inches and had a rubber pad on the ankle bone. They were comfortable, but not for long walks as the heels were pretty flat, we just used them for going out on patrol. We also had lovely white woollen socks; I think all these things were made in Australia. We had Bush hats with a mosquito net attached to the brim and tied around the neck, but not many used them, as it was too hard to breathe with the heat. I didn’t wear mine at all.

We had canvas water wings as well, which we wet before blowing them up it was supposed to seal them. The canvas water bottles were the same, wet before they were filled and hooked onto the mule because they dripped all the time. Everybody had a six-foot toggle rope[8], which had a loop at one end and a peg at the other, so we could be looped together to make a long rope if we needed one; they were also knotted about every foot.

We had a dah, a jacknife and escape money, I cant remember whether it was twenty or twenty five silver rupees; sixty rounds of ammunition, a couple of grenades, Bren magazines and ten days rations. These consisted of milk powder, dates, nuts, acid drops to keep your mouth moist, big square biscuits, tea, and sugar lumps. I can’t remember anything else. I know there was no bully beef and we were always hungry, we never got a square meal.

Early on in the expedition we used to line up in the morning and the officer used to shout “come and get your eggs and bacon,” it was a little tablet and we got more out of that tablet than the rations, we always felt better after we had taken it.

The time came at Jhansi for us to move off to Burma and everything went on the train, we went straight across India to the north east and after that we were on a narrow gauge railway for a couple of days and that was the end of our riding, it was on foot all the way from then on. We were marching towards Imphal and went through a little state called Manipur and I remember the natives building roads and they all had brass armlets on they looked like proper tribesmen, through the Naga Hills and down to Imphal, I think it took us around six days but might have been a bit longer.

[1] Most convoys transporting troops to the Far East, stopped over at either Cape Town or Durban, this usually involved a period of shore leave for the men.

[2] Deolali was a large British Reinforcement Centre located just northeast of Bombay. Most, if not all British soldiers passed through the cantonment at one point or other during their stay on the sub-continent.

[3] Harry Taylor and the draft of Lancashire Fusiliers arrived at the Saugor Camp on 30th September 1942.

[4] Jhansi was a large railway intersection town. 77th Brigade held it’s final large-scale training exercise at Jhansi, just before Christmas 1942.

[5] 3781572 Pte. William Satchell. Killed in action on the 24th April 1943 whilst attempting to cross the Irrawaddy River on a makeshift raft.

[6] A Dah was a large machete styled knife.

[7] A typical Chindit pack with a full compliment of rations could weigh as much as 70lbs.

[8] For convenience and easy access, soldiers used to wrap this toggle rope around their Bush hat.

I think we were only there (Freetown) one day before we sailed for Cape Town[1], now that was well organised; the day after we docked, there were coaches and private cars to pick us up and run us about, they took us up Table Mountain and we went to the Beach Hotel, which was all laid out with tables full of stuff which was rationed at home, so we all had a right good feast.

Then the bar opened for a free half-hour, well some of them but not me, were on the short stuff weren’t they and had a right good time. Anyhow after about three or four days we left Cape Town and we hadn’t been at sea very long when a terrible storm came on, we daren’t go on deck for about three days, one chap was scalded badly when going down a ladder with a bucket of tea. Then we docked at Bombay and we were straight off and on a train down to Deolali[2] and I think we were there about a couple of weeks. There were no parades or anything, I think they were letting us get acclimatised, we were just eating and lying down, I think we stayed there about two weeks and then we went back on the train to Bombay and from Bombay to Saugor in the Central Provinces.

We got off the train and a bloke met us on a charger, it was night-time, we didn’t know where we were going and after a forced march with dust flying everywhere we came to Saugor village. Now Saugor village wasn’t a big place, but there was a cinema there and we used to go the few days we were at Saugor and they were all cowboy pictures, nowt but cowboys, Tom Mix and that lot. I cant remember how long we stayed there before we marched off into the jungle and that’s when our training started which mainly consisted of map and compass use, moving silently and mostly forced marches to harden us up, we hadn’t got mules then so it was mostly marching.

It was while we were at Saugor[3] and coming back after a march, that the Sergeant Major got down on one knee and fired and killed a deer as big as a mule, it took four blokes to carry it, they didn’t get back to camp until the next day, he wasn’t very popular. The grub we got was mostly deer or goat meat, but whatever we got there were always onions with it, apparently Wingate loved his onions, he always had some with him I think he thought they kept disease away, whether it did or not I don’t know. For breakfast it was always porridge, I know it wasn’t egg and bacon, I didn’t put any weight on, I was still my usual just over nine stone.

From Saugor we went to a place called Jhansi[4] where we were under canvas and we were finishing training and that’s when the mules came, it must have been December just coming up to Christmas. We went down to the railway station to get these mules and it was just like a rodeo with their back legs flying all over the place, we had a terrible day. Now with mules, even when they’d quietened down you could never trust them, you’d be walking along and they’d try and sit down. I had one I called Mollie for about a month, I’d unloaded it and put a halter on it and as I turned round it must have smelt water because it shot off and I had to let the halter go because it was burning my hand, when I finally caught it up, it was stood there having a drink.

The chargers were lovely horses, the officers used them for going to meetings, but they didn’t last as long as the mules. One day (whilst in Burma) I was following Bill Satchell[5] who was a groom and was leading one which was getting over a tree trunk when it gave a groan and dropped dead. At the beginning of the day it took about five of us to get the load on and when you were loading a mule you always got the girth strap, pulled it tight and brought your knee up into its stomach and then, as they gasped for breath got an extra couple of holes, then the load wouldn’t slip round.

I remember on one supply drop, I went out to collect some stuff and after the third trip I turned round and the rest had gone into the jungle and I was alone when the saddle slipped round and I weren’t half in it. Lucky for me Mollie was pretty quiet by now and just stood there and didn’t try to run away, so I’d no trouble with it, but I couldn’t get the load back up on my own. As I’m trying, a Ghurka came up, his mule was loaded up and he could see what had happened so he helped me take the load off, put the saddle back on and load up again. He couldn’t speak English, but he beckoned me to follow him, and by this time it was going dark and we’d no idea were the rest had gone.

We used to tie a piece of parachute cloth to the mule’s tail so you could see it bobbing up and down in the dark. So I’m following this thing and I don’t know how he knew where he were going, whether he could smell them or not, but we walked for a long, long way and eventually caught up with the column. By this time they’d stopped and were bedding down for the night and the Sergeant said, unload the mules, get down and get some sleep and pointed to a bit of a clearing. Anyway I tied the mule up and got down, I used to sleep with my head under the saddle and it wasn’t long before it was coming light again and as I woke and looked about I could see some skeletons around me. There must have been fourteen or fifteen altogether, one was sat up against a tree had a bullet hole through the forehead, they’d all been shot, quite a few of the lads came to look at them, we thought they might have been evacuees fleeing from the Japs the year before.

Picking loads up on a supply drop, you had to be quick and get back in because you were always out in the open. What they used to do for these drops was light four bonfires in a box formation and as the planes came over they’d see the smoke and come in once to make sure everything was ok, then come round again and make the first drop which was ammunition with red parachutes; rations were always the last. When you got your rations, which were for ten days of course, not knowing when you were going to get the next lot you made them last longer than ten days.

It was at Jhansi we got our new equipment, the best thing was a frame with a pack they were called Everest frames. You could put your big pack on it and your small one as well, on the side your water bottle and your Dah[6], the frame kept it all off your back by a couple of inches so the air could circulate. They were really comfortable to have on, especially as you were carrying all that weight[7], and when you sat down it was grand, we just undid the belt buckle and it was just like sitting in a chair, there were also a couple of loops to put your thumbs in.

The boots were standard Army boots, but we were also issued with what they called patrol boots, which were like a suede material, they came up the calf about eight inches and had a rubber pad on the ankle bone. They were comfortable, but not for long walks as the heels were pretty flat, we just used them for going out on patrol. We also had lovely white woollen socks; I think all these things were made in Australia. We had Bush hats with a mosquito net attached to the brim and tied around the neck, but not many used them, as it was too hard to breathe with the heat. I didn’t wear mine at all.

We had canvas water wings as well, which we wet before blowing them up it was supposed to seal them. The canvas water bottles were the same, wet before they were filled and hooked onto the mule because they dripped all the time. Everybody had a six-foot toggle rope[8], which had a loop at one end and a peg at the other, so we could be looped together to make a long rope if we needed one; they were also knotted about every foot.

We had a dah, a jacknife and escape money, I cant remember whether it was twenty or twenty five silver rupees; sixty rounds of ammunition, a couple of grenades, Bren magazines and ten days rations. These consisted of milk powder, dates, nuts, acid drops to keep your mouth moist, big square biscuits, tea, and sugar lumps. I can’t remember anything else. I know there was no bully beef and we were always hungry, we never got a square meal.

Early on in the expedition we used to line up in the morning and the officer used to shout “come and get your eggs and bacon,” it was a little tablet and we got more out of that tablet than the rations, we always felt better after we had taken it.

The time came at Jhansi for us to move off to Burma and everything went on the train, we went straight across India to the north east and after that we were on a narrow gauge railway for a couple of days and that was the end of our riding, it was on foot all the way from then on. We were marching towards Imphal and went through a little state called Manipur and I remember the natives building roads and they all had brass armlets on they looked like proper tribesmen, through the Naga Hills and down to Imphal, I think it took us around six days but might have been a bit longer.

[1] Most convoys transporting troops to the Far East, stopped over at either Cape Town or Durban, this usually involved a period of shore leave for the men.

[2] Deolali was a large British Reinforcement Centre located just northeast of Bombay. Most, if not all British soldiers passed through the cantonment at one point or other during their stay on the sub-continent.

[3] Harry Taylor and the draft of Lancashire Fusiliers arrived at the Saugor Camp on 30th September 1942.

[4] Jhansi was a large railway intersection town. 77th Brigade held it’s final large-scale training exercise at Jhansi, just before Christmas 1942.

[5] 3781572 Pte. William Satchell. Killed in action on the 24th April 1943 whilst attempting to cross the Irrawaddy River on a makeshift raft.

[6] A Dah was a large machete styled knife.

[7] A typical Chindit pack with a full compliment of rations could weigh as much as 70lbs.

[8] For convenience and easy access, soldiers used to wrap this toggle rope around their Bush hat.

Harry Taylor recalled:

We were at Imphal about three days, it rained all the time we were there, we had groundsheets and propped them up and got underneath to shelter. While we were waiting there it was decision time as to whether we were going in or not, there was a bit of a confrontation about it, I think it was going to be cancelled, I think that’s why we were waiting.[1]

Then we were off through the Naga Hills, one of the roads they called the ‘chocolate staircase’ and I think it took us about four weeks to get to the Burma front. When we marched through the mountains, there were some caves which had been tunnelled into the mountainside which were full of stores. I went with a mule one time and picked up a load of Bartlett pears, something that was on ration back home and one of the blokes said “do you like onions,” I said, "I love onions" and he said, “put this in your pack and keep it to yourself,” it was a block about an inch thick and a foot square of dried onions. He said “break about a spoonful off, mix it in some hot water and it’ll fill your mess tin.” Of course when I started cooking they could all smell them and wanted to know where they’d come from, I gave some away but not all.

Eventually we crossed the border into Burma and reached the Chindwin. We crossed in canoes[2] which held about five or six men, the mules had to be unloaded, the loads taken across in the canoes, then the mules swam across and we then had to load them up again and take them into the jungle out of sight. All this took us that day and part of the next day as well, it was quite a big job. The bullocks swam across, they had panniers on and carried the ammunition and were to supply us with food on the hoof so to speak once we got in, I don’t know how often we killed them, but I remember seeing one that had been shot strung up on a tree and a chap who must have been a butcher was cutting it up.

I was picked out of the section one day, to go for our meat and came back with a damn big piece, plenty for ten men and we dry cooked it in the embers of our fire and put it in our packs and just cut a piece off when we wanted it. I don’t know how many bullocks we had, but there were quite a few and when the jungle got too dense for them to get through, that’s when we started to kill them. On the second day after we crossed my section was picked to go with an Intelligence officer (possibly Lt. George Henry Borrow), I can’t remember his name but I’d never seen him before, and we went though villages telling them that British troops would be returning to Burma shortly.

I remember he had all sorts of gadgets on him, escape stuff. I remember him showing us a neckerchief which when you held it up to the light revealed an escape map of Burma. He also showed us a button on the bottom of his slacks with a mark on it, which when suspended on a thread pointed north, he also said he had a wire saw hidden in the seam of his trousers, there were other things as well but I cant remember them.

After we left the officer we marched around with only the odd halt for an hour or so and then off again. We’d cross the same stream ten or twelve times, to put the Japanese off our tracks. Burma was a funny country, there were places with loads of streams and other places where the streams had dried up and we had to dig for water, sometimes as much as two or three feet down, then we had to wait while it cleared, fill the water bottles and wait again then put the purification tablet in and wait again before drinking any. Drinking unpurified water caused a lot of dysentery.

We didn’t stop for long in any one place, we’d bed down for the night, then get up, light our fires so the smoke couldn’t be seen for the mist in the trees, have a brew and then off. Bamboo jungle was hard going, we used to chop in relays of three or four, someone once said we’d only travelled about a mile one day. Teak trees were hard going as well, they grew so close together we had to unload the mules, take the loads through, then the mules and load them up again.

We got to a place called Pinlebu and we’d stopped on a hill, a nice secluded spot, everybody was lousy by this time and when I say lousy I mean lousy, we were all absolutely full of them, we never got rid of them. So when we got the chance we used to take our pants and shirts off and run down the seams with a match to burn the eggs out.

All of a sudden, without any warning there was all this automatic fire, the bark on the tree in front of me was flying all over the place, it was there that three men were wounded. One bloke had the top of his leg taken off, I don’t know what with, I suppose it could have been a mortar round, another lad was wounded in the shoulder and the other one was Bill Davis; now Bill had that bullet in his arm till the day he died, I think it was near a nerve and they wouldn’t touch it for fear of losing his arm.

Of course there was a lot of confusion and one of our men, I think he was a full Corporal, led us round the back to where the firing had come from, but there was nothing there. After this we got to the Irrawaddy River where there was more automatic firing, it seemed to come from a long way off, but it must have hit somebody because they were asking for a field dressing on the bank where I was, in fact I passed it up to them. There were days when we went out with 142 Sabotage Section (Commandos) but we never had any trouble at that time. Then we got to Baw[3], and something had gone wrong, the timing or something like that and they were waiting for us when we got there.

I’d started suffering with malaria by that time and I remember being laid down behind a tree. While I was there behind the tree, they brought in this bloke who’d been shot, I think through the lower chest, his officer had killed this Japanese, I think he was going to bayonet him. They dragged Suddery (Pte. James Suddery) out and put him behind the tree where I was and while he was sat against the tree the bullet just plopped out of his belly. I’m not sure, but I think while he was on the plane[4] he had the bullet in his hand showing everybody and he had it when we were in Karachi.

During all this time, Wingate just strolled about with all this lead flying around as though nothing was happening, he didn’t give a toss. He never bothered, he just walked up to the front, I don’t know who he was talking to, then he just walked back. After that, they had me on a mule for about five days. Every time we stopped for a brew or whatever I didn’t eat anything, I was just drinking water, but they looked after me, at night they made sure I was bedded down.

When we got to the Shwelli River I’d had my big pack and rifle taken off me and left with my small pack with whatever rations I had left; I was travelling light. When we were waiting to cross the river it was pitch black and we’d a big round dinghy, some had already crossed and then it was our turn. There were twelve of us altogether, but it didn’t hold all twelve, one or two were holding on to the ropes on the side and we set off. We hadn’t gone very far when the current tipped the dinghy and we were nearly tipped out and suddenly it stopped, I don’t know why and a voice said, “cut the rope.”

It sounded as though someone was chopping it against a tree and as soon as they had cut it off we went down the river. I don’t know how far we went, but it must have been five or six miles before we managed to get to the other bank. We dragged the dinghy onto the bank and as it was dark the only thing we could do was get down to sleep. In the morning Sgt. Scruton (Stanley Scruton from Stockport in Greater Manchester) said we’ll let the dinghy down and drag it back to where the column should be, that’s if they were still there.

So before we set off he had us tip out what rations we had and divided them equally between us, I did a little bit better with cigarettes and matches. Then we set off back dragging the dinghy which was a fair old weight, we dragged it with the ropes that were round the sides taking it in turns and it must have been around mid-afternoon by the time we got back to the crossing, we could see were in the right place because the rope was hanging from the tree where they’d chopped it.

There was nobody around so Sgt. Scruton got us in to the undergrowth and as it was nearly dark we got down to sleep. In the morning Sgt. Scruton said we had to get to the railway, as that’s where the column was heading. Now, before we started off he had his map and compass out and dropped the compass on the ground on this bit of banking, we searched for it for ages but didn’t find it.

So after a lot of messing about we got on our way and ended up in some elephant grass, now elephant grass is about twelve to fifteen feet high and we couldn’t find our way out, we must have been walking around in circles. We were in it all day and night and the next day we saw a dead tree which one of the lads climbed and he said he could see a village not far away, so by walking in that direction we managed to get out. I seem to remember getting a little rice from there, but not much and Sgt Scruton said, even if we had plenty in our packs if we got the chance for more we should always take it. Later we hit another village and asked them for guides to take us to the railway and two young lads, about twelve years old said they would but only for one day. I always remember one of them had a thin piece of bamboo sharpened at both ends with some fruit which looked something like a grapefruit stuck on it and when we were walking they kept bobbing up and down, I think they must have been their haversack rations for the trip.

Anyway they led us to the railway, but it was dark when we got there, but we could see the railway about ten feet away, there was a fire a short distance down the track and one of the boys said “Japany” and they both disappeared. When we looked to our left, about thirty yards away was a bonfire and what looked like a Japanese patrol, we stayed where we were and one of the Jap’s came towards us collecting firewood. We were under some bushes and could see his hand picking pieces of wood up, then he vanished back to the fire. Sgt. Scruton told us to take our boots off, tie the laces together and hang them around our necks so we wouldn’t make a noise on the lines as we crossed, so one after the other we got across safely.

I cannot say how many villages we passed through, but there were quite a few and we had enough rice and after a few days we were near the Irrawaddy, when we met a chap who said he was a fisherman and when we asked him if he would take us across he said yes, but not just then. He told us to get into the undergrowth there on the riverbank and he would come back tomorrow and bring us some food, so we did but he didn’t show up, so we waited all the next day and he turned up with a basket full of fish and boiled rice, I don’t like fish but I was glad of it then.

Anyway he said he couldn’t take twelve of us in one go, but he’d take us six at a time, so that’s what he did and I went with the last lot. We’d been going two or three more days and came to a village at the bottom of some mountains and got some rice there, but not much and just after we left Sgt. Scruton saw a lemon tree and said “just what we want, if we squeeze some lemon juice on our rice it’ll make a nice change.” The trouble was they were wild lemons and were so bitter it burnt our lips and we had to throw all the rice away.

We kept hitting villages, some were better than others, then we went into one and this bloke, he looked a right shifty type, he wanted us to go, he looked scared, anyway we got some bananas and off we went and Peter (an Indian participant on Operation Longcloth) who spoke Burmese said he didn’t like the look of him he couldn’t be trusted. Anyway, in what looked just like a small orchard we shared the bananas out and ate them and we’d been there a while when all of a sudden they started mortaring us, they were falling short quite a way off us, but they were coming in the right direction. I think they dropped about five, one after another; anyway we got away as quick as we could and it was going dark by then.

There was a big fallen tree trunk that we were leaning on when we heard an engine and looking back we saw a scout car with a searchlight on it. It turned left as if it’s coming towards us with the searchlight going from right to left. Sergeant Scruton said, “get down and whatever you do don’t move or we’ve had it,” so we bent down behind the trunk and after a while they started to back out and moved away, we could still see it a long way away with the light shining in the trees.

I’ll tell you the names of the party now, I forgot before. In the party, which was actually a sick party, well I say a sick party, two had rifles I think the Sergeant had a Tommy Gun and the Corporal had something. Well there was Sergeant Scruton who was one of my platoon Sergeants, Lance Corporal Johnson (Frederick Johnson) who was attached to the mules, there was me, Ronnie Johnson from Manchester, Eric Allen from London, Joe Hoyle, now I think Joe came from around Birmingham way, but I’m not sure, then there was Peter an Indian soldier who spoke fluent Burmese and Sammy another Indian, there were two Burmese from the Burma Rifles which were attached to the Brigade, Tommy Timms and another chap, called darkie Whyment[5], I never knew his first name.

[1] The Chindit operation of 1943 was to be one component of a three-phased incursion into Burma. Both the other elements, including a Chinese Army advance from the northeast had been postponed. Brigadier Wingate and General Wavell took the decision to continue with the Chindit expedition whilst the Brigade were based at Imphal.

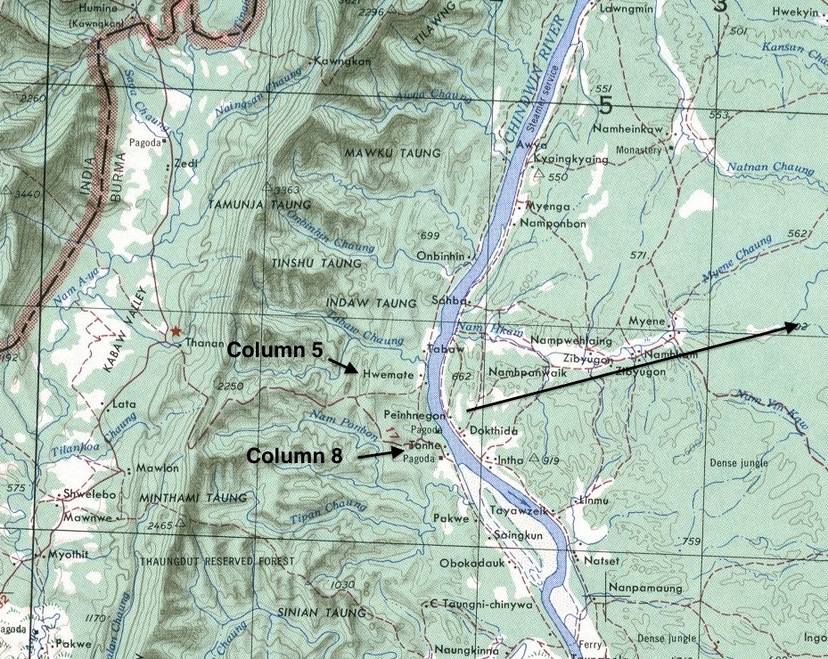

[2] 8 Column crossed the Chindwin River at a place called Tonhe, pronounced Tun-Hey, see above map.

[3] The Chindits had organized a large supply drop at the village of Baw on 24th March 1943. The area around the village was not secured properly and the supply drop was compromised with the Japanese infiltrating the drop zone. A minor battle ensued, with heavy involvement from 8 Column.

[4] This is a reference to the Dakota rescue plane, which picked up 18 members of 8 Column in late April 1943.

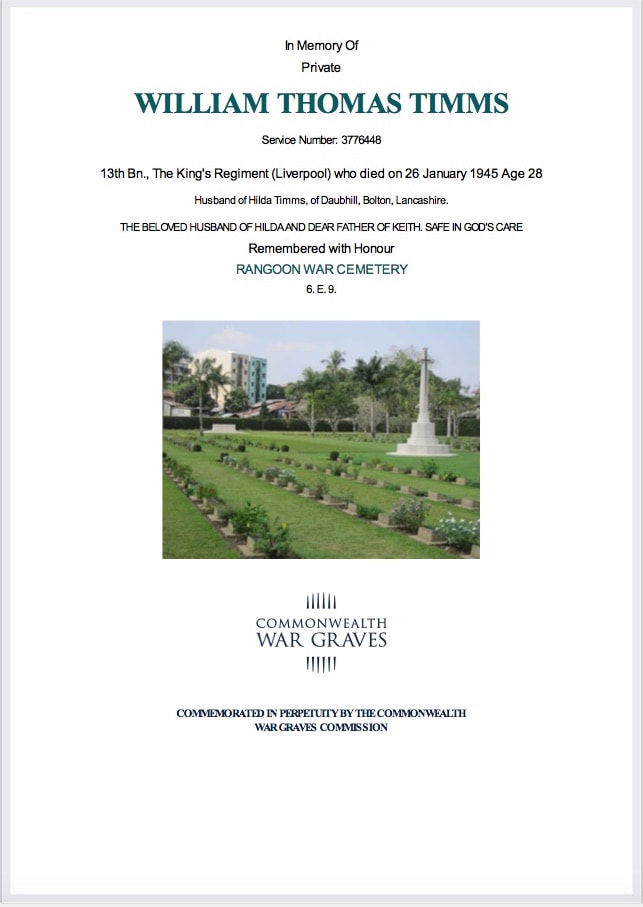

[5] This was 5105487 Pte. Harry Leonard Whyment from Newbold-on-Avon in Warwickshire. Harry was captured on the journey back to India and died inside Rangoon Jail on the 26th June 1943.

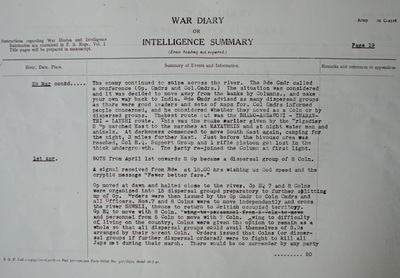

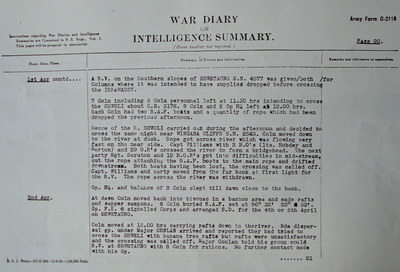

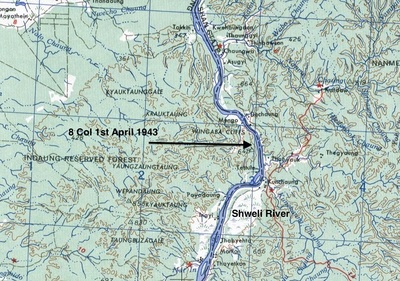

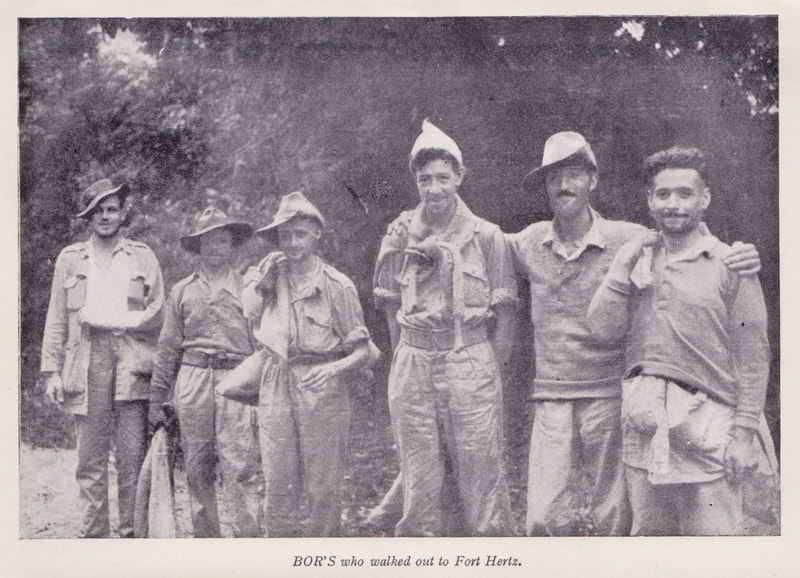

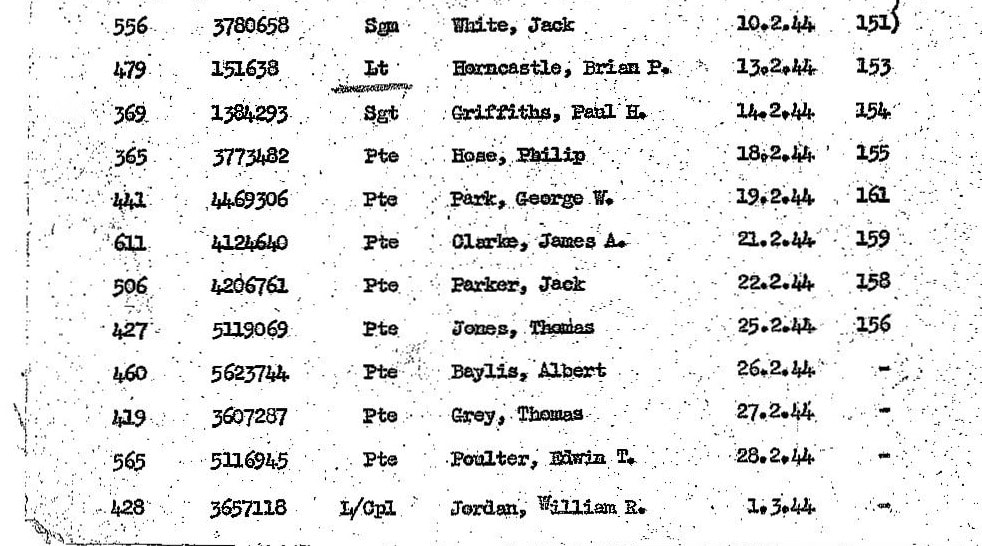

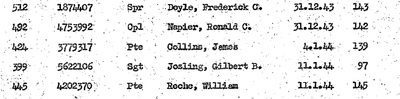

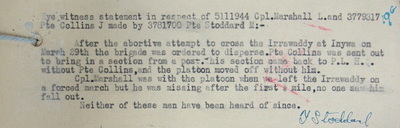

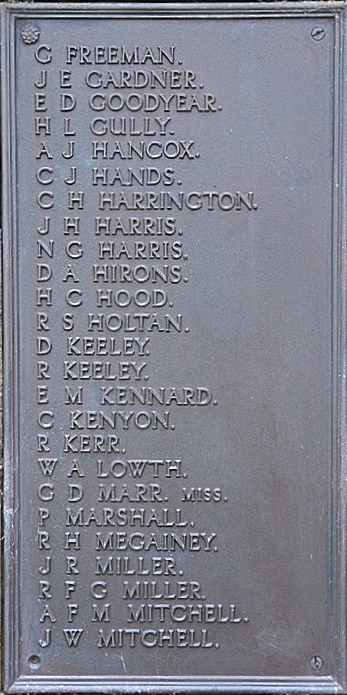

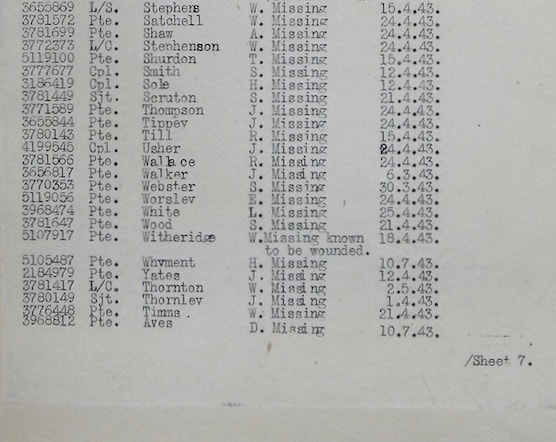

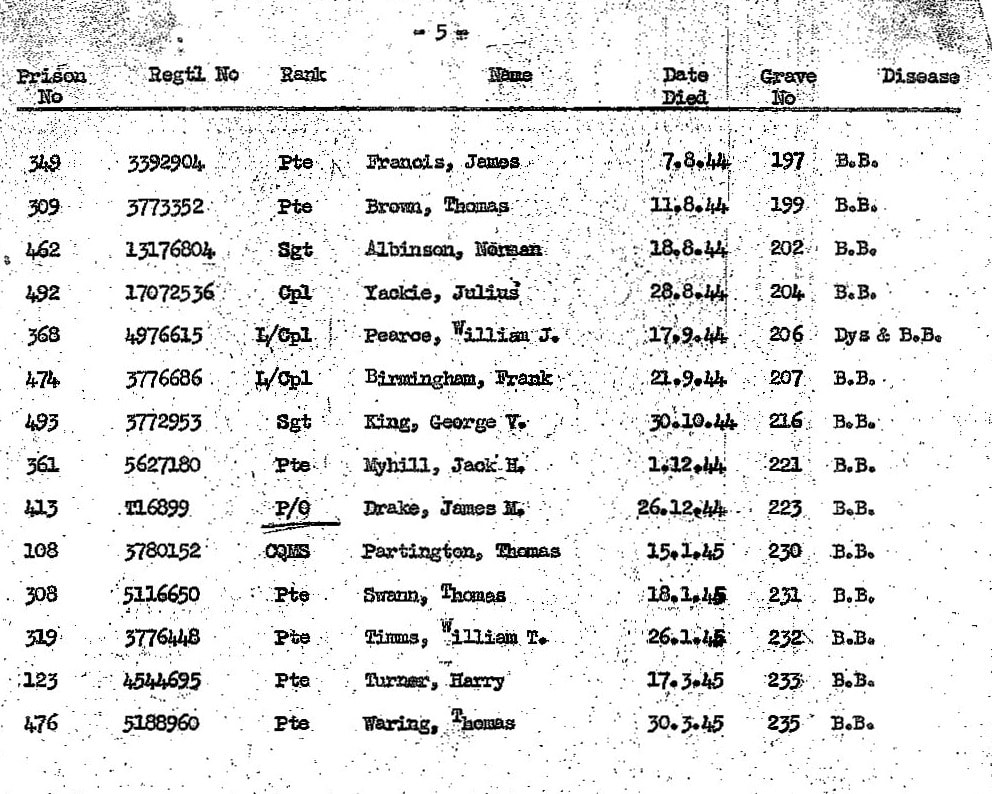

Shown below is another gallery of images in relation to this story, including pages from the official War diary of 8 Column from Operation Longcloth and a map of the general location around the Shweli River, where Harry and the other men were washed away in the RAF dinghy on the 1st April 1943. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

We were at Imphal about three days, it rained all the time we were there, we had groundsheets and propped them up and got underneath to shelter. While we were waiting there it was decision time as to whether we were going in or not, there was a bit of a confrontation about it, I think it was going to be cancelled, I think that’s why we were waiting.[1]

Then we were off through the Naga Hills, one of the roads they called the ‘chocolate staircase’ and I think it took us about four weeks to get to the Burma front. When we marched through the mountains, there were some caves which had been tunnelled into the mountainside which were full of stores. I went with a mule one time and picked up a load of Bartlett pears, something that was on ration back home and one of the blokes said “do you like onions,” I said, "I love onions" and he said, “put this in your pack and keep it to yourself,” it was a block about an inch thick and a foot square of dried onions. He said “break about a spoonful off, mix it in some hot water and it’ll fill your mess tin.” Of course when I started cooking they could all smell them and wanted to know where they’d come from, I gave some away but not all.

Eventually we crossed the border into Burma and reached the Chindwin. We crossed in canoes[2] which held about five or six men, the mules had to be unloaded, the loads taken across in the canoes, then the mules swam across and we then had to load them up again and take them into the jungle out of sight. All this took us that day and part of the next day as well, it was quite a big job. The bullocks swam across, they had panniers on and carried the ammunition and were to supply us with food on the hoof so to speak once we got in, I don’t know how often we killed them, but I remember seeing one that had been shot strung up on a tree and a chap who must have been a butcher was cutting it up.

I was picked out of the section one day, to go for our meat and came back with a damn big piece, plenty for ten men and we dry cooked it in the embers of our fire and put it in our packs and just cut a piece off when we wanted it. I don’t know how many bullocks we had, but there were quite a few and when the jungle got too dense for them to get through, that’s when we started to kill them. On the second day after we crossed my section was picked to go with an Intelligence officer (possibly Lt. George Henry Borrow), I can’t remember his name but I’d never seen him before, and we went though villages telling them that British troops would be returning to Burma shortly.

I remember he had all sorts of gadgets on him, escape stuff. I remember him showing us a neckerchief which when you held it up to the light revealed an escape map of Burma. He also showed us a button on the bottom of his slacks with a mark on it, which when suspended on a thread pointed north, he also said he had a wire saw hidden in the seam of his trousers, there were other things as well but I cant remember them.

After we left the officer we marched around with only the odd halt for an hour or so and then off again. We’d cross the same stream ten or twelve times, to put the Japanese off our tracks. Burma was a funny country, there were places with loads of streams and other places where the streams had dried up and we had to dig for water, sometimes as much as two or three feet down, then we had to wait while it cleared, fill the water bottles and wait again then put the purification tablet in and wait again before drinking any. Drinking unpurified water caused a lot of dysentery.

We didn’t stop for long in any one place, we’d bed down for the night, then get up, light our fires so the smoke couldn’t be seen for the mist in the trees, have a brew and then off. Bamboo jungle was hard going, we used to chop in relays of three or four, someone once said we’d only travelled about a mile one day. Teak trees were hard going as well, they grew so close together we had to unload the mules, take the loads through, then the mules and load them up again.

We got to a place called Pinlebu and we’d stopped on a hill, a nice secluded spot, everybody was lousy by this time and when I say lousy I mean lousy, we were all absolutely full of them, we never got rid of them. So when we got the chance we used to take our pants and shirts off and run down the seams with a match to burn the eggs out.

All of a sudden, without any warning there was all this automatic fire, the bark on the tree in front of me was flying all over the place, it was there that three men were wounded. One bloke had the top of his leg taken off, I don’t know what with, I suppose it could have been a mortar round, another lad was wounded in the shoulder and the other one was Bill Davis; now Bill had that bullet in his arm till the day he died, I think it was near a nerve and they wouldn’t touch it for fear of losing his arm.

Of course there was a lot of confusion and one of our men, I think he was a full Corporal, led us round the back to where the firing had come from, but there was nothing there. After this we got to the Irrawaddy River where there was more automatic firing, it seemed to come from a long way off, but it must have hit somebody because they were asking for a field dressing on the bank where I was, in fact I passed it up to them. There were days when we went out with 142 Sabotage Section (Commandos) but we never had any trouble at that time. Then we got to Baw[3], and something had gone wrong, the timing or something like that and they were waiting for us when we got there.

I’d started suffering with malaria by that time and I remember being laid down behind a tree. While I was there behind the tree, they brought in this bloke who’d been shot, I think through the lower chest, his officer had killed this Japanese, I think he was going to bayonet him. They dragged Suddery (Pte. James Suddery) out and put him behind the tree where I was and while he was sat against the tree the bullet just plopped out of his belly. I’m not sure, but I think while he was on the plane[4] he had the bullet in his hand showing everybody and he had it when we were in Karachi.

During all this time, Wingate just strolled about with all this lead flying around as though nothing was happening, he didn’t give a toss. He never bothered, he just walked up to the front, I don’t know who he was talking to, then he just walked back. After that, they had me on a mule for about five days. Every time we stopped for a brew or whatever I didn’t eat anything, I was just drinking water, but they looked after me, at night they made sure I was bedded down.

When we got to the Shwelli River I’d had my big pack and rifle taken off me and left with my small pack with whatever rations I had left; I was travelling light. When we were waiting to cross the river it was pitch black and we’d a big round dinghy, some had already crossed and then it was our turn. There were twelve of us altogether, but it didn’t hold all twelve, one or two were holding on to the ropes on the side and we set off. We hadn’t gone very far when the current tipped the dinghy and we were nearly tipped out and suddenly it stopped, I don’t know why and a voice said, “cut the rope.”

It sounded as though someone was chopping it against a tree and as soon as they had cut it off we went down the river. I don’t know how far we went, but it must have been five or six miles before we managed to get to the other bank. We dragged the dinghy onto the bank and as it was dark the only thing we could do was get down to sleep. In the morning Sgt. Scruton (Stanley Scruton from Stockport in Greater Manchester) said we’ll let the dinghy down and drag it back to where the column should be, that’s if they were still there.

So before we set off he had us tip out what rations we had and divided them equally between us, I did a little bit better with cigarettes and matches. Then we set off back dragging the dinghy which was a fair old weight, we dragged it with the ropes that were round the sides taking it in turns and it must have been around mid-afternoon by the time we got back to the crossing, we could see were in the right place because the rope was hanging from the tree where they’d chopped it.

There was nobody around so Sgt. Scruton got us in to the undergrowth and as it was nearly dark we got down to sleep. In the morning Sgt. Scruton said we had to get to the railway, as that’s where the column was heading. Now, before we started off he had his map and compass out and dropped the compass on the ground on this bit of banking, we searched for it for ages but didn’t find it.

So after a lot of messing about we got on our way and ended up in some elephant grass, now elephant grass is about twelve to fifteen feet high and we couldn’t find our way out, we must have been walking around in circles. We were in it all day and night and the next day we saw a dead tree which one of the lads climbed and he said he could see a village not far away, so by walking in that direction we managed to get out. I seem to remember getting a little rice from there, but not much and Sgt Scruton said, even if we had plenty in our packs if we got the chance for more we should always take it. Later we hit another village and asked them for guides to take us to the railway and two young lads, about twelve years old said they would but only for one day. I always remember one of them had a thin piece of bamboo sharpened at both ends with some fruit which looked something like a grapefruit stuck on it and when we were walking they kept bobbing up and down, I think they must have been their haversack rations for the trip.

Anyway they led us to the railway, but it was dark when we got there, but we could see the railway about ten feet away, there was a fire a short distance down the track and one of the boys said “Japany” and they both disappeared. When we looked to our left, about thirty yards away was a bonfire and what looked like a Japanese patrol, we stayed where we were and one of the Jap’s came towards us collecting firewood. We were under some bushes and could see his hand picking pieces of wood up, then he vanished back to the fire. Sgt. Scruton told us to take our boots off, tie the laces together and hang them around our necks so we wouldn’t make a noise on the lines as we crossed, so one after the other we got across safely.

I cannot say how many villages we passed through, but there were quite a few and we had enough rice and after a few days we were near the Irrawaddy, when we met a chap who said he was a fisherman and when we asked him if he would take us across he said yes, but not just then. He told us to get into the undergrowth there on the riverbank and he would come back tomorrow and bring us some food, so we did but he didn’t show up, so we waited all the next day and he turned up with a basket full of fish and boiled rice, I don’t like fish but I was glad of it then.

Anyway he said he couldn’t take twelve of us in one go, but he’d take us six at a time, so that’s what he did and I went with the last lot. We’d been going two or three more days and came to a village at the bottom of some mountains and got some rice there, but not much and just after we left Sgt. Scruton saw a lemon tree and said “just what we want, if we squeeze some lemon juice on our rice it’ll make a nice change.” The trouble was they were wild lemons and were so bitter it burnt our lips and we had to throw all the rice away.

We kept hitting villages, some were better than others, then we went into one and this bloke, he looked a right shifty type, he wanted us to go, he looked scared, anyway we got some bananas and off we went and Peter (an Indian participant on Operation Longcloth) who spoke Burmese said he didn’t like the look of him he couldn’t be trusted. Anyway, in what looked just like a small orchard we shared the bananas out and ate them and we’d been there a while when all of a sudden they started mortaring us, they were falling short quite a way off us, but they were coming in the right direction. I think they dropped about five, one after another; anyway we got away as quick as we could and it was going dark by then.

There was a big fallen tree trunk that we were leaning on when we heard an engine and looking back we saw a scout car with a searchlight on it. It turned left as if it’s coming towards us with the searchlight going from right to left. Sergeant Scruton said, “get down and whatever you do don’t move or we’ve had it,” so we bent down behind the trunk and after a while they started to back out and moved away, we could still see it a long way away with the light shining in the trees.

I’ll tell you the names of the party now, I forgot before. In the party, which was actually a sick party, well I say a sick party, two had rifles I think the Sergeant had a Tommy Gun and the Corporal had something. Well there was Sergeant Scruton who was one of my platoon Sergeants, Lance Corporal Johnson (Frederick Johnson) who was attached to the mules, there was me, Ronnie Johnson from Manchester, Eric Allen from London, Joe Hoyle, now I think Joe came from around Birmingham way, but I’m not sure, then there was Peter an Indian soldier who spoke fluent Burmese and Sammy another Indian, there were two Burmese from the Burma Rifles which were attached to the Brigade, Tommy Timms and another chap, called darkie Whyment[5], I never knew his first name.

[1] The Chindit operation of 1943 was to be one component of a three-phased incursion into Burma. Both the other elements, including a Chinese Army advance from the northeast had been postponed. Brigadier Wingate and General Wavell took the decision to continue with the Chindit expedition whilst the Brigade were based at Imphal.

[2] 8 Column crossed the Chindwin River at a place called Tonhe, pronounced Tun-Hey, see above map.

[3] The Chindits had organized a large supply drop at the village of Baw on 24th March 1943. The area around the village was not secured properly and the supply drop was compromised with the Japanese infiltrating the drop zone. A minor battle ensued, with heavy involvement from 8 Column.

[4] This is a reference to the Dakota rescue plane, which picked up 18 members of 8 Column in late April 1943.

[5] This was 5105487 Pte. Harry Leonard Whyment from Newbold-on-Avon in Warwickshire. Harry was captured on the journey back to India and died inside Rangoon Jail on the 26th June 1943.

Shown below is another gallery of images in relation to this story, including pages from the official War diary of 8 Column from Operation Longcloth and a map of the general location around the Shweli River, where Harry and the other men were washed away in the RAF dinghy on the 1st April 1943. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Harry Taylor's diary concludes:

So, that made up the twelve in the party. Well we came to a village and as we usually did stopped outside watching for quite a while to make sure it was safe and Sgt. Scruton said, "we’ll see if we can get some rice," so we went towards it, but it was up a slight incline and as we were going up and had just reached the top, a Japanese patrol with a couple of Burmese guides at the front appeared and started firing. I turned left and ran back down the hill and the rest seemed to disperse in different directions. Well I don’t know how they missed hitting me, I was running across open ground and then up a hill and as I’m trying to get up I could see two or three of the others running along a ridge at the top towards me, so I ran towards them and caught them up.

There were then five of us, me, Ronnie Johnson, Eric Allen, Joe Hoyle and Peter, we didn’t know where the other seven had gone, we just got down under some thick bushes and stayed there. Then there was lots of shouting and some automatic firing which went on for about an hour.

Well we decided we’d have to get back on our own, as far as rations went we were ok for a day or two and kept getting bits of rice from the odd village. In some of the villages we passed through, the name Homelin[1] kept cropping up. Outside one village Peter spoke to a chap who told us to stay were we were and he’d go and make arrangements to get us some food, we stayed there about an hour and where in two minds whether to move on, when a different chap came and said they wouldn’t be long and that they were still preparing it for us. Well by that time it was dark and all of a sudden a row of flaming torches appeared, quite a few of them and we couldn’t tell who they were really, but when they got to us we could see they where Burmese and they had chicken, fruit, and plenty of rice, loads of stuff and we had a really good meal at that place.

Most of the villages had something like a summer house, I don’t know what they were called but we were in one in a village and were lying down. We were exhausted and a chap who I think must have been a Burmese monk by the colour of his robe and headdress came and gave us some V cigarettes, I think he probably got them from one of our supply drops and as we were smoking them, a Burmese woman came and wanted to know if we wanted something to eat, she said, “I wont be long I’ll go and get you some rice.” She’d no sooner gone when the priest came and said she was an informer and we’d better be on our way, so we left there and not long after came to a small village of about ten huts and the Headman invited us to stay overnight.

The houses were on stilts so we climbed up into one and when we got in he offered us these Burmese cheroots, well to smoke a cheroot you’d to more or less lie down, or else the tobacco tended to fall out, they seemed to be full of tobacco and what looked like small chips of bamboo wrapped in a leaf. I didn’t sleep at all, the weather was stifling and I could hardly breathe, I was glad to get out of there.

We were near the Chindwin by this time and came across a chap who lived near by and said he’d take us across, but it was a bit dangerous because there were informers keeping their eyes open on anyone crossing the river. He told us to “stay where you are” like they always did and he’d come back for us; he did come back, but I was in a state by then, where I could hardly walk so he carried me on his back to his boat. We sailed down the river, you couldn’t sail straight across and we passed a boat with a couple of chaps in it who were shouting across asking who we were, we’d been told to keep down so they must not have seen us and they carried on by.

Anyway, we got across and slept on the other side of the Chindwin that night. Sometime later we bumped into a party of Ghurkas carrying rations on a bamboo pole and Peter asked them where their camp was. They got a boat and sailed us down another river which flowed into the Chindwin, I don’t know what it was called and landed us at a place which was a kind of hilltop stronghold manned by Scottish troops, me and Ronnie Johnson stayed there a couple of nights because he had started with malaria at this time and Eric Allen, Joe Hoyle and Peter carried on.

Some Naga tribesmen carried Ronnie and me on bamboo litters for two days to a bell tented camp and we slept in one of the tents, then to a nearby road where an ambulance picked us up and took us to Imphal. I’ll never forget, Ronnie was in the front and I was in the back and the Indian driver was speeding round the bends and Ronnie was playing hell with him.

Eventually we got to Imphal, I cant remember how long we were there, but I’d lost four stone and was down to five stone two and Ronnie had lost quite a bit as well. I don’t remember the date we got to Imphal, but it was the second week in June when we were taken to a deserted village with plenty of huts called bashas, were everyone who came out from Burma were being collected. I knew I was the only one to come back from 18 Platoon except a Sergeant (Tony Aubrey) who came out on the plane, and when I was going home on leave from Cark in Cartmel Camp back in the UK, I was in a carriage with a Corporal McCann[2], who had been shot through both cheeks and lost some teeth and had come out on his own.

After this place, I remember being on a train going to Karachi and I had started with malaria and dysentery again and they took me off the train with another bloke who’s name was also Taylor. They took us on stretchers to a Red Cross marquee not far away and I was there overnight. The day after I went to a place called Ghoati (possibly Gauhati), now the other chap called Taylor I didn’t see again and I never saw him when I got back to battalion either.

When I got to Ghoati, I was admitted to the American Baptist Mission Hospital which wasn’t a military hospital but was full of Americans who were building the Ledo Road. I’d probably been there about six weeks when one of the doctors and a sister were going to a place called Shelong (Shillong) and they took me with them. I was in the military hospital there, had malaria again and when I recovered went to a holding camp still in Shelong full of people waiting to rejoin their battalions. From there I went to Karachi[3] and recall, having to wait for three days at Calcutta for the train and when I got to Karachi there were none of 18 Platoon there, it would probably have been about a month before Christmas, something like that and I ended up spending Christmas in hospital again.

Eventually I was back on duty, but the weight I’d put on in those few months I lost again and was back down to five stone. After a lot of tests they diagnosed me with tropical sprue and if you had that and passed a board, it meant a ticket home to the UK. So off I went to Poona, passed the board inspection and was shipped home and landed at Liverpool. I then went to Whittingham Hospital (near Preston) for about two weeks and got back home on VE Day morning, I was then in the Liverpool Hospital of Tropical Medicine for supervision and stayed there till about September, after that Scarisbrick Hall near Southport, then Seighton Camp near Chester, which was a military recuperation camp and finished up at Cark in Cartmel waiting for demob and that was that!

[1] The Burmese town of Homalin was an important Japanese garrison town located in the Chindwin Valley.

[2] Corporal A. McCann was the only soldier from 18 Platoon to make it back to India after the disaster at the Shweli River on the 1st April 1943.

[3] The Napier Barracks at Karachi was the new base for the 13th King’s after Operation Longcloth.

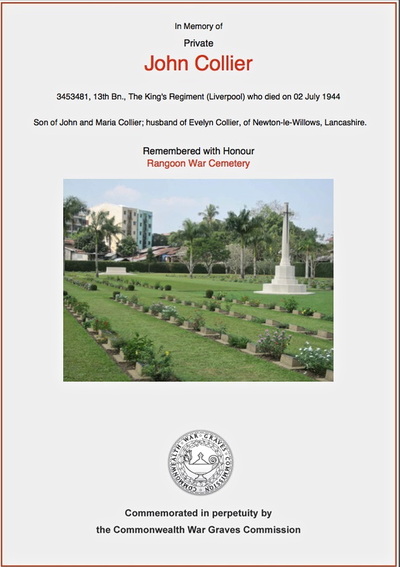

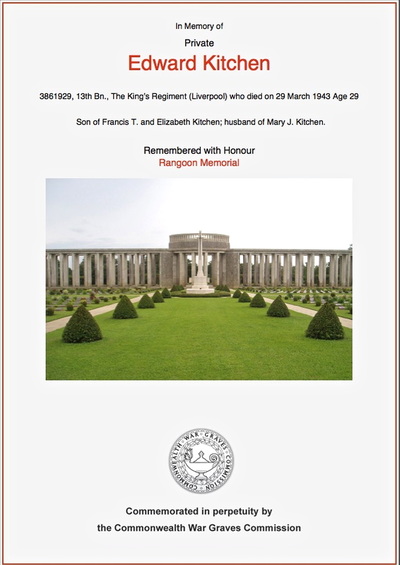

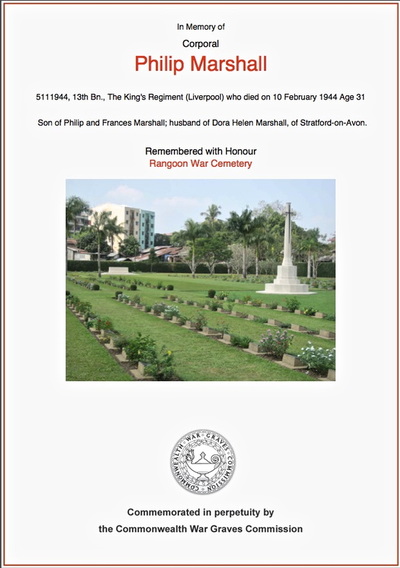

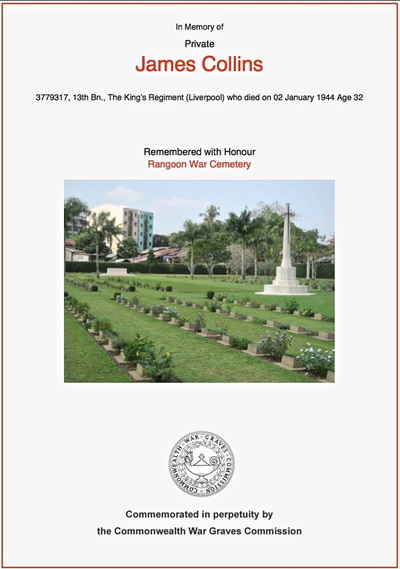

Seen below is the final gallery of photographs in relation to the war time story of Pte. Harry Taylor. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

So, that made up the twelve in the party. Well we came to a village and as we usually did stopped outside watching for quite a while to make sure it was safe and Sgt. Scruton said, "we’ll see if we can get some rice," so we went towards it, but it was up a slight incline and as we were going up and had just reached the top, a Japanese patrol with a couple of Burmese guides at the front appeared and started firing. I turned left and ran back down the hill and the rest seemed to disperse in different directions. Well I don’t know how they missed hitting me, I was running across open ground and then up a hill and as I’m trying to get up I could see two or three of the others running along a ridge at the top towards me, so I ran towards them and caught them up.