Pte. 3968404 Frank Holland, a 'Dorset Chindit'

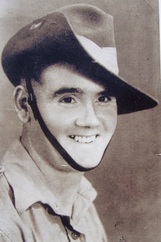

School Boy Frank Holland.

School Boy Frank Holland.

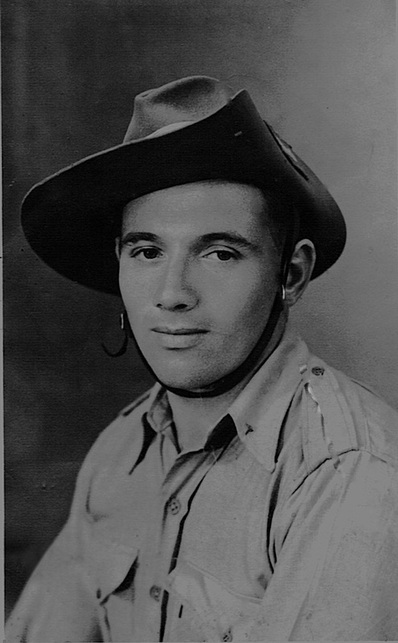

Frank Holland was a Chindit survivor from Operation Longcloth in 1943. He was part of Column 8 that year, led by its popular commander, Major Walter Purcell Scott. Although he had gone through great hardship in Burma, Frank always believed that it had been his privilege and honour to serve his country during World War Two. The story that follows tells of his life leading up to his enlistment into the British Army and comes from his own personal journal, which has now been published by his son Gerry Holland.

To read Gerry's full account of his father's life, please click on the following link:

http://store.blurb.com/ebooks/398291-a-dorset-chindit

Frank Holland was born during the years of the First World War, he grew up and worked on the farmlands of Somerset and Dorset, often working alongside his own father in the fields and cowsheds. He adored the outdoor life and took part in all the activities you would expect a young boy from a rural environment to partake of and relish. As a young man living in the Bolney area of Sussex, Frank joined the 'Sussex Walking and Athletic Club' and was soon winning various running and track medals.

As the war years moved in, he became desperately keen to join up and do his duty for King and Country. However, because Frank worked on the land, he was unable to do so. Farming was one of the countries 'reserved occupations' and those working within these industries were deemed exempt from serving in the Armed Forces.

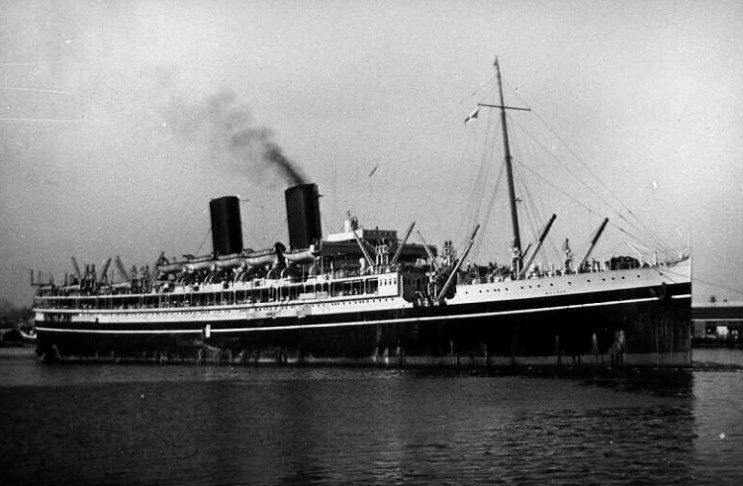

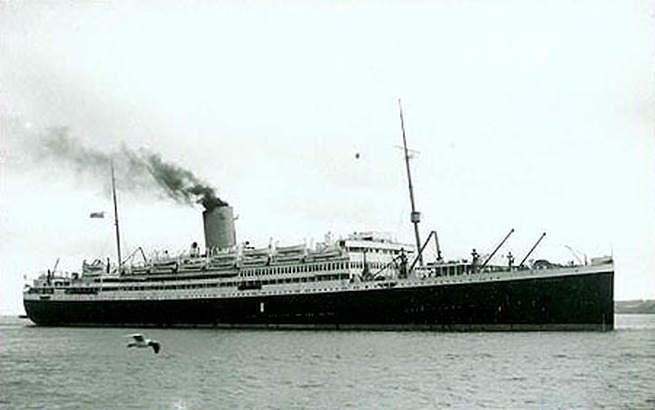

True to his character, Frank Holland was not to be denied. He left his job on the land and changed occupation for a short time before enlisting in to the British Army and was posted to the Infantry Training Centre at Verne Citadel, Portland. On the 18th April 1940, he was posted to Signals within the 1st Royal Welch Fusiliers, a few short weeks later he found himself with the 8th Warwick's and based at Hereford. Here he enjoyed all the experiences of Army training and communal life within the barrack room. The Warwick's moved once more, this time to Tavistock in Devon. It was at this location that Frank volunteered for overseas service and soon, he and some other volunteers from the 8th Warwick's joined Convoy WS 18 at Liverpool Docks and embarked aboard the SS Maloja for destinations then unknown.

Men were never told exactly where they were being posted for obvious security reasons, but it did not take much working out as the vessels of Convoy 18 entered more tropical waters and solar topees were being issued for use on deck. For Frank and his fellow shipmates, being on an Upper Deck at any time during the long voyage was a relief and blessing, allowing the men to escape the cramped and stifling conditions of their quarters in the bowels of the ship. Frank was billeted well below on F Deck during his time aboard the Maloja.

The voyage was an eventful one, with the ships pushing out westward, well into the Atlantic, before turning on a more southerly course which would eventually see them docking at Freetown, Sierra Leone for refitting and refuelling. This route was well travelled and of course there was always the danger of both German and Italian submarine activity. The SS Maloja was part of the convoy section which stopped at Cape Town, South Africa in mid-May 1942, the other half moved further round the Cape and docked at Durban. The men were allowed to disembark at these two ports and enjoyed the renowned hospitality of their South African hosts, often being taken into their homes for meals, or being driven around the local areas on sightseeing tours.

To read Gerry's full account of his father's life, please click on the following link:

http://store.blurb.com/ebooks/398291-a-dorset-chindit

Frank Holland was born during the years of the First World War, he grew up and worked on the farmlands of Somerset and Dorset, often working alongside his own father in the fields and cowsheds. He adored the outdoor life and took part in all the activities you would expect a young boy from a rural environment to partake of and relish. As a young man living in the Bolney area of Sussex, Frank joined the 'Sussex Walking and Athletic Club' and was soon winning various running and track medals.

As the war years moved in, he became desperately keen to join up and do his duty for King and Country. However, because Frank worked on the land, he was unable to do so. Farming was one of the countries 'reserved occupations' and those working within these industries were deemed exempt from serving in the Armed Forces.

True to his character, Frank Holland was not to be denied. He left his job on the land and changed occupation for a short time before enlisting in to the British Army and was posted to the Infantry Training Centre at Verne Citadel, Portland. On the 18th April 1940, he was posted to Signals within the 1st Royal Welch Fusiliers, a few short weeks later he found himself with the 8th Warwick's and based at Hereford. Here he enjoyed all the experiences of Army training and communal life within the barrack room. The Warwick's moved once more, this time to Tavistock in Devon. It was at this location that Frank volunteered for overseas service and soon, he and some other volunteers from the 8th Warwick's joined Convoy WS 18 at Liverpool Docks and embarked aboard the SS Maloja for destinations then unknown.

Men were never told exactly where they were being posted for obvious security reasons, but it did not take much working out as the vessels of Convoy 18 entered more tropical waters and solar topees were being issued for use on deck. For Frank and his fellow shipmates, being on an Upper Deck at any time during the long voyage was a relief and blessing, allowing the men to escape the cramped and stifling conditions of their quarters in the bowels of the ship. Frank was billeted well below on F Deck during his time aboard the Maloja.

The voyage was an eventful one, with the ships pushing out westward, well into the Atlantic, before turning on a more southerly course which would eventually see them docking at Freetown, Sierra Leone for refitting and refuelling. This route was well travelled and of course there was always the danger of both German and Italian submarine activity. The SS Maloja was part of the convoy section which stopped at Cape Town, South Africa in mid-May 1942, the other half moved further round the Cape and docked at Durban. The men were allowed to disembark at these two ports and enjoyed the renowned hospitality of their South African hosts, often being taken into their homes for meals, or being driven around the local areas on sightseeing tours.

On 7th June 1942 the SS Maloja docked at Bombay, the 'Gateway to India'. Almost all Allied Convoy ships drew up alongside the Ballard Pier extension of the docks and the men and supplies were off-loaded and made their way to the railway terminus. Frank remembers being totally spellbound by the sights and sounds of Indian life, for all men from the British Isles it must have been like another world, which of course in some respects it was.

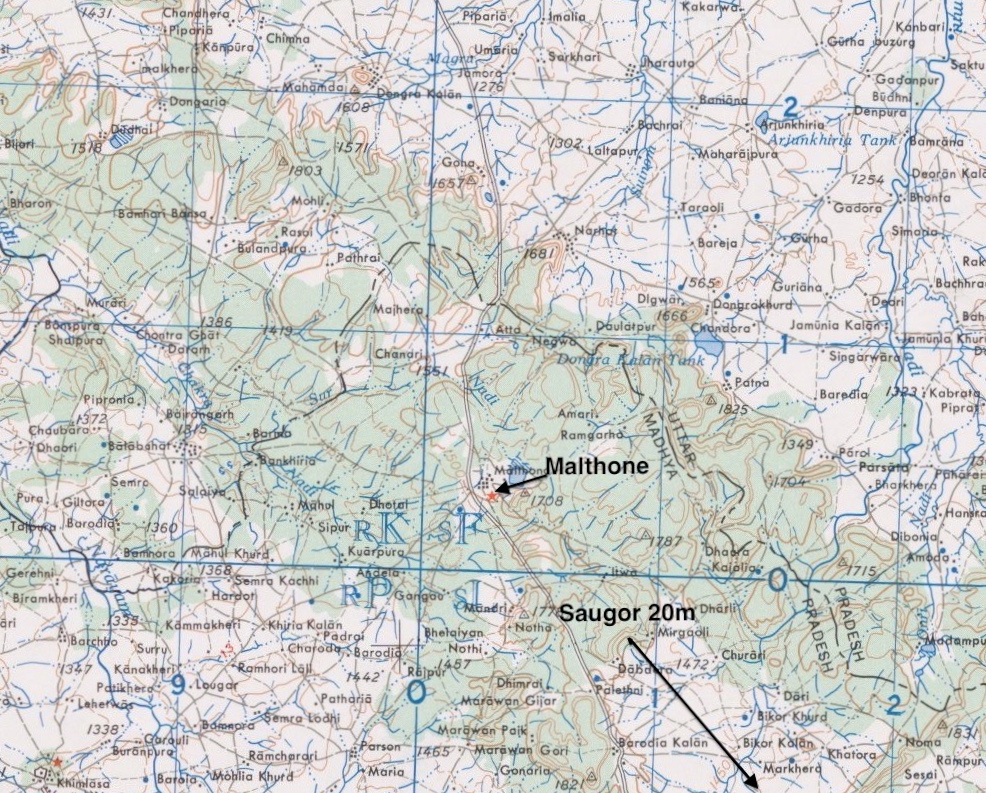

Frank was almost immediately posted to Saugor in the Central Provinces of India. He remembers; "our topees were taken away and replaced with Australian bush hats". He was posted to the Malthone Camp which was situated 20 miles northwest of the Saugor town. Here, he and the other reinforcement units from regiments such as the Warwicks, Devons, South Lancs and Sherwood Foresters came to make up the depleted numbers of the 13th Kings Liverpool's for Chindit training. The Kings had suffered badly from illness and disease and their original number of 850 had been reduced by well over 250 men by the late summer of 1942. Wingate drew reinforcements from wherever he could locate them.

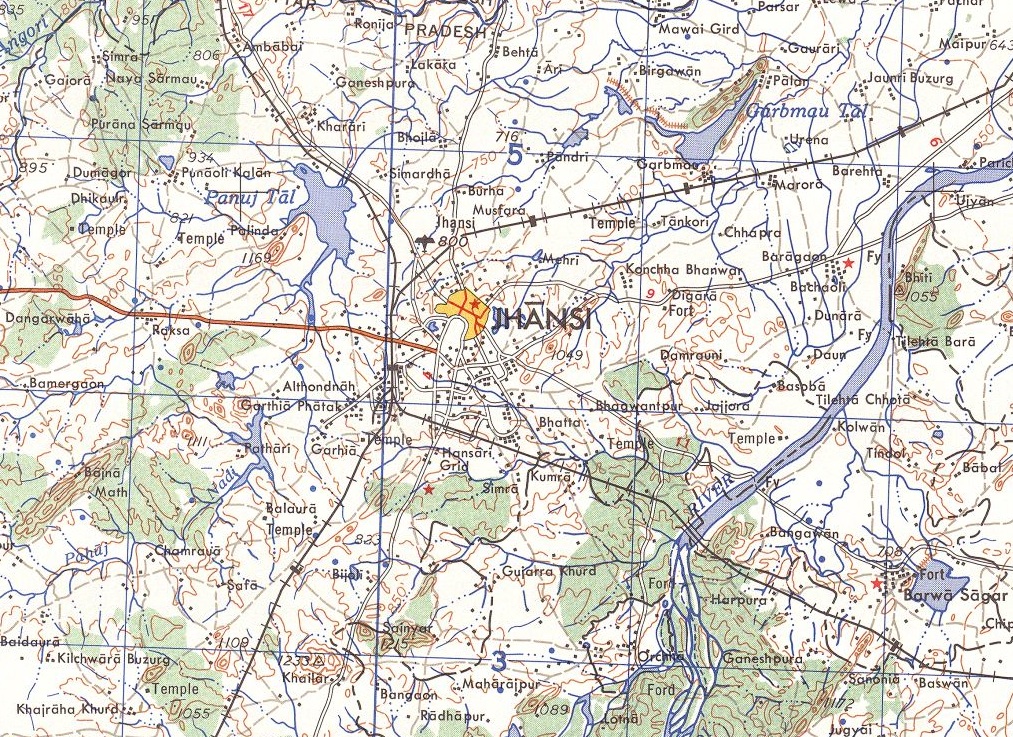

Chindit training included map reading, orienteering (something in which Frank excelled) and the ubiquitous river craft and jungle survival tactics. Soon the mules and their drivers arrived and the expedition numbers were finalised before setting off on a long march to the Indian railway town of Jhansi. Here the Chindit Columns took part in the last full training exercise involving all troops, before they prepared for the journey to the Assam/Burmese border and the Chindwin River.

Frank remembered the long route taken to the border, the rail journey to Dimapur, the paddle steamer voyage up the Brahmaputra River and the long a winding march through to Imphal and beyond. It was whilst waiting at Imphal that Frank sent his last airgraph home.

We will leave the story there for now, other than to say that after the Chindit expedition was over and Frank had recuperated back in India, his next posting was to the 15th (Kings) Parachute Battalion and their training base at Bilaspur. Coincidently the Para Battalion's Head Quarters were back at Malthone, so Frank had come full circle. For more information on this unit please follow the link below: www.paradata.org.uk/unit/15th-kings-parachute-battalion

Frank was almost immediately posted to Saugor in the Central Provinces of India. He remembers; "our topees were taken away and replaced with Australian bush hats". He was posted to the Malthone Camp which was situated 20 miles northwest of the Saugor town. Here, he and the other reinforcement units from regiments such as the Warwicks, Devons, South Lancs and Sherwood Foresters came to make up the depleted numbers of the 13th Kings Liverpool's for Chindit training. The Kings had suffered badly from illness and disease and their original number of 850 had been reduced by well over 250 men by the late summer of 1942. Wingate drew reinforcements from wherever he could locate them.

Chindit training included map reading, orienteering (something in which Frank excelled) and the ubiquitous river craft and jungle survival tactics. Soon the mules and their drivers arrived and the expedition numbers were finalised before setting off on a long march to the Indian railway town of Jhansi. Here the Chindit Columns took part in the last full training exercise involving all troops, before they prepared for the journey to the Assam/Burmese border and the Chindwin River.

Frank remembered the long route taken to the border, the rail journey to Dimapur, the paddle steamer voyage up the Brahmaputra River and the long a winding march through to Imphal and beyond. It was whilst waiting at Imphal that Frank sent his last airgraph home.

We will leave the story there for now, other than to say that after the Chindit expedition was over and Frank had recuperated back in India, his next posting was to the 15th (Kings) Parachute Battalion and their training base at Bilaspur. Coincidently the Para Battalion's Head Quarters were back at Malthone, so Frank had come full circle. For more information on this unit please follow the link below: www.paradata.org.uk/unit/15th-kings-parachute-battalion

On the 25th August 2012 I received this email contact from the template form on my website:

Hi Steve,

I'm in the middle of writing a book based on the journal kept by my father up until he died in April 2000. He was a Chindit in 8th Column with Major Scott. I was getting some information verified when I came upon your website. My father's journal has a lot of information on the KIngs Liverpool's and prior to that the Warwick's. One of his three friends who went in with him was Teddy Gale who I think is one of the names you have listed. The journal covers operation 'Longcloth' with names and details. I'm actually at the point involving Saugor at the moment and entering these details in the book I'm writing.

Any help I can give, or information revealed in the journal, I will send as soon as possible. The first draft of the Book will be complete in October. On another point. The photo of the lads at Saugor. My Father is in the front row sat cross legged, two from the right. We will never see the likes of these people again. Only the generation before them, the First Wold War Veterans can match them.

Regards

Gerry Holland.

So as you can see, it was only good fortune that Gerry stumbled across the Saugor photograph (seen above) and then my website. We have kept in touch over the last year or so and he has sent me some very interesting material and of course photographs. One topic of conversation was the men's adoration for the Column 8 Commander, Major Scott, or 'Scottie' as he was affectionately known. Gerry told me that;

"In regards to Major Scott, it seems he was universally liked by all the men in 8th Column. My father mentions him in relation to the original crossing of the Chindwin River."

We also discussed the existence of original certificates of participation for the men of Operation Longcloth. Gerry still had Frank's certificate, which was the fourth such example I had seen, all of which belonging to men from Column 8. The awards are signed by Lieut. Col. S.A. Cooke, who was the senior officer from the 13th King's on Operation Longcloth and technically the commander of Northern Group, even though this section included Brigadier Wingate. Cooke dispersed with Column 8 in late April 1943 and I wonder if this is the reason why only men from that unit seem to possess these certificates.

Gerry had served previously in the RAF and still flies today, in fact one of his aircraft carried the Chindit flash insignia on its fuselage and provoked many a question and admiring glance from passers by.

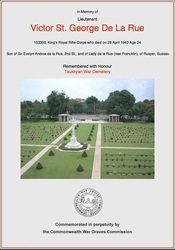

There was also to be another Chindit related connection to the Holland family from after the war was over. Gerry told me that, "I have one mystery to work out involving my father. After the war he visited Lady De La Rue at Rusper in Sussex, in regard to her son, Victor St. George, who was killed on Operation Longcloth. She offered Dad his first job after demob on her Estate and that is where I was born in 1947. I'm not sure if her son was in 8th Column or not."

In fact, Lieutenant Victor St. George De La Rue served in the Gurkha section of the operation as a member of Chindit Column 1, he was killed during the Column's long journey back to India on the 28th April 1943. To read more about this journey and Lieutenant De La Rue's untimely death please read the story linked here: Lieut. Col. LA Alexander

Update 19/02/2015. The full story of St. George de la Rue and his life before Operation Longcloth can now be found within these website pages, please follow the link here: Lieutenant Victor St. George de la Rue

I will leave the final thought in this section to Gerry Holland:

"Reading back over my father's time during the war the underlying feeling is of great comradeship and acceptance of doing what is right. In fact the whole Armed Services scene in the main has that at its core. I'm in the middle of getting together as many of my old entry in the RAF for a 50th reunion next year. Most of them I haven't been in contact for 45 years, but still that kinship rises to the fore on meeting. It's the good side of human nature I think."

Seen below are some images and photographs relating to the story so far, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Hi Steve,

I'm in the middle of writing a book based on the journal kept by my father up until he died in April 2000. He was a Chindit in 8th Column with Major Scott. I was getting some information verified when I came upon your website. My father's journal has a lot of information on the KIngs Liverpool's and prior to that the Warwick's. One of his three friends who went in with him was Teddy Gale who I think is one of the names you have listed. The journal covers operation 'Longcloth' with names and details. I'm actually at the point involving Saugor at the moment and entering these details in the book I'm writing.

Any help I can give, or information revealed in the journal, I will send as soon as possible. The first draft of the Book will be complete in October. On another point. The photo of the lads at Saugor. My Father is in the front row sat cross legged, two from the right. We will never see the likes of these people again. Only the generation before them, the First Wold War Veterans can match them.

Regards

Gerry Holland.

So as you can see, it was only good fortune that Gerry stumbled across the Saugor photograph (seen above) and then my website. We have kept in touch over the last year or so and he has sent me some very interesting material and of course photographs. One topic of conversation was the men's adoration for the Column 8 Commander, Major Scott, or 'Scottie' as he was affectionately known. Gerry told me that;

"In regards to Major Scott, it seems he was universally liked by all the men in 8th Column. My father mentions him in relation to the original crossing of the Chindwin River."

We also discussed the existence of original certificates of participation for the men of Operation Longcloth. Gerry still had Frank's certificate, which was the fourth such example I had seen, all of which belonging to men from Column 8. The awards are signed by Lieut. Col. S.A. Cooke, who was the senior officer from the 13th King's on Operation Longcloth and technically the commander of Northern Group, even though this section included Brigadier Wingate. Cooke dispersed with Column 8 in late April 1943 and I wonder if this is the reason why only men from that unit seem to possess these certificates.

Gerry had served previously in the RAF and still flies today, in fact one of his aircraft carried the Chindit flash insignia on its fuselage and provoked many a question and admiring glance from passers by.

There was also to be another Chindit related connection to the Holland family from after the war was over. Gerry told me that, "I have one mystery to work out involving my father. After the war he visited Lady De La Rue at Rusper in Sussex, in regard to her son, Victor St. George, who was killed on Operation Longcloth. She offered Dad his first job after demob on her Estate and that is where I was born in 1947. I'm not sure if her son was in 8th Column or not."

In fact, Lieutenant Victor St. George De La Rue served in the Gurkha section of the operation as a member of Chindit Column 1, he was killed during the Column's long journey back to India on the 28th April 1943. To read more about this journey and Lieutenant De La Rue's untimely death please read the story linked here: Lieut. Col. LA Alexander

Update 19/02/2015. The full story of St. George de la Rue and his life before Operation Longcloth can now be found within these website pages, please follow the link here: Lieutenant Victor St. George de la Rue

I will leave the final thought in this section to Gerry Holland:

"Reading back over my father's time during the war the underlying feeling is of great comradeship and acceptance of doing what is right. In fact the whole Armed Services scene in the main has that at its core. I'm in the middle of getting together as many of my old entry in the RAF for a 50th reunion next year. Most of them I haven't been in contact for 45 years, but still that kinship rises to the fore on meeting. It's the good side of human nature I think."

Seen below are some images and photographs relating to the story so far, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

I have been given permission by Gerry to reproduce some of his father's memoirs in regard to his time on Operation Longcloth within these website pages. We begin his Chindit story at Christmas 1942, the 13th Kings have moved up to the Indian rail terminus at Jhansi, they have completed their final training exercise and are now enjoying the festive season the best way they can. Some of the officers from Column 5 improvised with their own 'home brewed' whiskey, whilst the Other ranked soldiers from the Brigade made do with whatever the local Indian population could provide.

Frank Holland recalls:

At Jhansi we had all the usual Christmas fare and a church parade. All the canteen staff turned out to hang garlands of flowers around everybody’s neck, this was no mean feat when you think we numbered over one thousand. We saw New Year in then we entrained for our journey across India. It was a very big task with such a number as by then we had dogs, bullocks with carts plus mules and chargers.

NB: The entire Brigade needed nine locomotives to transfer all the men, livestock and supplies from Jhansi.

The journey was very interesting but uncomfortable. As India has two different gauge railways we had to off load and entrain again, after more than a week our train journey finished. We then went by paddle steamer up the river Braumaputra it was very hot and crowded. The Braumaputra is a vast waterway with islands and sandbanks. The paddle steamer kept going day and night for two days and then we docked, entrained for Dimapur and that was the end of our rail travel. We went to various camps and then we were on our way for real.

The powers that be then decided as I came from a farm I had better take charge of the bullocks. There was twenty seven of them some with carts the rest with packs and they were only partly broken in to cart and pack work, so much swearing and pushing was needed to get them up the big hills. The country side changed all the time, paddy fields (rice), thickly clad mountains with bamboo and scrub. Some of the hills had hanging tea gardens. It was a job to take it all in as we were marching between fifteen and thirty miles each day. These various distances were the staging camps where you got fed and rested.

We arrived at Imphal and rested up for a while. This was a chance to wash clothes and bath in the river. We were given some new bullocks to break in, fine beasts used to the Nago Hills, but no desire to loose their freedom and work. It took a while to get them tamed down and working but their fight for freedom was foremost in their minds. Whilst at Imphal I met up with some of the Royal Engineers from the ship we had sailed to India in. They asked us into their mess to have a good meal and a few beers which was a nice change for us.

One day General Wavell arrived to inspect the troops, very informal, a lot was made of the words of his, 'the 13th King’s Liverpool I salute you.' Next day we were given air mail letters to write free of post, these we were told would not be censored and very true they were, on returning from Burma we learned they were all burnt. One other thing made known before we moved off was that they would send an air mail home once each month, which they did. It read: 'owing to military operations your son (or what ever relation) is both safe and well, but he is unable to write to you, but please write to him as he is able to receive your mail.'

Next day we were off for real.

The first stage across the plains of Sabel was very hot and then we started the long climb up into the saddle, very steep and winding with long hair bends where you could see the road below and above you. We passed hundreds of Nago men and women working on the road, cracking down rocks into various sizes, right down to chippings. There were two reasons for this, one to help build the road, the other to keep them out of the pay of the Japs.

Frank Holland recalls:

At Jhansi we had all the usual Christmas fare and a church parade. All the canteen staff turned out to hang garlands of flowers around everybody’s neck, this was no mean feat when you think we numbered over one thousand. We saw New Year in then we entrained for our journey across India. It was a very big task with such a number as by then we had dogs, bullocks with carts plus mules and chargers.

NB: The entire Brigade needed nine locomotives to transfer all the men, livestock and supplies from Jhansi.

The journey was very interesting but uncomfortable. As India has two different gauge railways we had to off load and entrain again, after more than a week our train journey finished. We then went by paddle steamer up the river Braumaputra it was very hot and crowded. The Braumaputra is a vast waterway with islands and sandbanks. The paddle steamer kept going day and night for two days and then we docked, entrained for Dimapur and that was the end of our rail travel. We went to various camps and then we were on our way for real.

The powers that be then decided as I came from a farm I had better take charge of the bullocks. There was twenty seven of them some with carts the rest with packs and they were only partly broken in to cart and pack work, so much swearing and pushing was needed to get them up the big hills. The country side changed all the time, paddy fields (rice), thickly clad mountains with bamboo and scrub. Some of the hills had hanging tea gardens. It was a job to take it all in as we were marching between fifteen and thirty miles each day. These various distances were the staging camps where you got fed and rested.

We arrived at Imphal and rested up for a while. This was a chance to wash clothes and bath in the river. We were given some new bullocks to break in, fine beasts used to the Nago Hills, but no desire to loose their freedom and work. It took a while to get them tamed down and working but their fight for freedom was foremost in their minds. Whilst at Imphal I met up with some of the Royal Engineers from the ship we had sailed to India in. They asked us into their mess to have a good meal and a few beers which was a nice change for us.

One day General Wavell arrived to inspect the troops, very informal, a lot was made of the words of his, 'the 13th King’s Liverpool I salute you.' Next day we were given air mail letters to write free of post, these we were told would not be censored and very true they were, on returning from Burma we learned they were all burnt. One other thing made known before we moved off was that they would send an air mail home once each month, which they did. It read: 'owing to military operations your son (or what ever relation) is both safe and well, but he is unable to write to you, but please write to him as he is able to receive your mail.'

Next day we were off for real.

The first stage across the plains of Sabel was very hot and then we started the long climb up into the saddle, very steep and winding with long hair bends where you could see the road below and above you. We passed hundreds of Nago men and women working on the road, cracking down rocks into various sizes, right down to chippings. There were two reasons for this, one to help build the road, the other to keep them out of the pay of the Japs.

Frank continues:

I’ve forgotten many of the stages, but one stands out very vividly, the night of the thunderstorm, the torrential rain and lightening were unbelievable, many different colours a wonderful but almost frightening sight in its intensity. We heard and saw many baboon during the day but at night it was the croak of frogs and the click of cicadas. We followed on to Tamu and then left the dirt road and took to tracks. The bullocks were slower than the mules so we had got a long way behind the column by now, so we had to sacrifice sleep to try and catch up.

We were now joined by four elephants and their drivers, I learned something from them that night when we stopped for a break. To boil water for tea they cut a length of bamboo, filled it with water and stood it in the fire to boil and it works. That night was very hard, very dark and some very narrow paths along a ravine. Several times I was asked to go down and shoot horses and mules that had fallen over. It sounds strange but the lads just didn’t really know how to destroy an animal as big as a horse, but it had to be done to save it from suffering. When daylight came the track improved and we saw huts now and then. We were getting into real bamboo country. The day was easier, but the night again was bad, very dark and bad narrow paths.

To make things worse a message had been past back, to press on hard and try to catch up ready to cross the Chindwin River. But it didn’t work out because things became so bad we had to call a halt and rest. We had to dump some of our loads which included rum, we over indulged and when morning came we suffered, but no rest. We set off very early and arrived at the river by four a.m. The crossing had started but the chargers and mules were refusing to cross. Major Scott our Column Commander came along and asked us to try the bullocks and elephants as soon as we had eaten.

The scene was beautiful, big sandy stretches like the seaside, but the thought of what might be waiting on the other side took some of the shine away. We stripped naked and set off to cross, the bullock liked the water so we waded out with them for about thirty yards and then the current took over, it was frightening it swept your legs away and you could only go with it. The bullocks could swim like fish so we hung on to their tails, my mate Teddy Gale was swept away but after a while was picked up by a Burman in a dugout canoe.

The whole of that day was spent dragging mules into the water and then climbing into a dugout and been paddled across with a string of four mules swimming behind. We had got everything across by seven at night, twelve hours behind time. During the crossing one of the elephants was turned upside down by the weight of its load a Burman swam out and cut its load free and the elephant swam ashore.

I’ve forgotten many of the stages, but one stands out very vividly, the night of the thunderstorm, the torrential rain and lightening were unbelievable, many different colours a wonderful but almost frightening sight in its intensity. We heard and saw many baboon during the day but at night it was the croak of frogs and the click of cicadas. We followed on to Tamu and then left the dirt road and took to tracks. The bullocks were slower than the mules so we had got a long way behind the column by now, so we had to sacrifice sleep to try and catch up.

We were now joined by four elephants and their drivers, I learned something from them that night when we stopped for a break. To boil water for tea they cut a length of bamboo, filled it with water and stood it in the fire to boil and it works. That night was very hard, very dark and some very narrow paths along a ravine. Several times I was asked to go down and shoot horses and mules that had fallen over. It sounds strange but the lads just didn’t really know how to destroy an animal as big as a horse, but it had to be done to save it from suffering. When daylight came the track improved and we saw huts now and then. We were getting into real bamboo country. The day was easier, but the night again was bad, very dark and bad narrow paths.

To make things worse a message had been past back, to press on hard and try to catch up ready to cross the Chindwin River. But it didn’t work out because things became so bad we had to call a halt and rest. We had to dump some of our loads which included rum, we over indulged and when morning came we suffered, but no rest. We set off very early and arrived at the river by four a.m. The crossing had started but the chargers and mules were refusing to cross. Major Scott our Column Commander came along and asked us to try the bullocks and elephants as soon as we had eaten.

The scene was beautiful, big sandy stretches like the seaside, but the thought of what might be waiting on the other side took some of the shine away. We stripped naked and set off to cross, the bullock liked the water so we waded out with them for about thirty yards and then the current took over, it was frightening it swept your legs away and you could only go with it. The bullocks could swim like fish so we hung on to their tails, my mate Teddy Gale was swept away but after a while was picked up by a Burman in a dugout canoe.

The whole of that day was spent dragging mules into the water and then climbing into a dugout and been paddled across with a string of four mules swimming behind. We had got everything across by seven at night, twelve hours behind time. During the crossing one of the elephants was turned upside down by the weight of its load a Burman swam out and cut its load free and the elephant swam ashore.

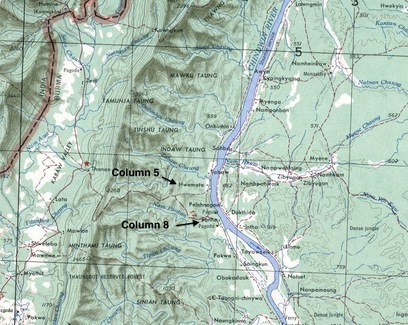

We moved off from Tonhe to Tonmakeng to await a ration drop. It was a night drop, so fires had to be lit to mark the dropping zone. The drop was successful except one load was dropped astray and the Japs got there first, as it was our mail it gave our strength away, but misled them as it landed well south of our intended route.

Whilst we were at Tonmakeng news came in of a Jap working party twenty five miles away at Linglamong. I was in the party sent down to attack them. It was a very hard march through elephant grass at times and waterless country. We arrived very tired and keyed up for our first encounter, but on arrival found they had gone. We had to dig deep into a dry river bed to get water and it takes a long time to seep in. Having brewed up and fed man and mule we marched back to Tonmakeng only to be told we were off again.

It was a game trail over the escarpment in waterless country. Hard work all the way and much clearing of bamboo to be done. The Burmese were able to get some water for themselves from some of the bamboo, but its knowing what type to look for. You need to be born there to learn the jungle. Firelighting was another art of theirs with flint and tinder.

The lie of the land was very deceiving, as you have to walk up and down the contours, steep up and steep down hence thirty six miles was only about twenty miles forward. When we did reach the flatter area we came to the Yu Yu River which was bad for the mules as no way can you stop a thirsty mule from drinking especially in the dark and everybody physically exhausted. The result was mules with colic. Once again the old story, you come from a farm Pte. Holland and know about animals, you help treat them, so hours spent sticking medicine balls down their throats and keeping them moving till daylight. We took a few days rest in this area as the river came in handy for bathing and washing clothes.

We heard gunfire from time to time which took some of the picnic atmosphere out of the stay. Tension was rising now as we were due to attack Indawgy aerodrome and take it, but after the Burmese recce it was called off as we were out numbered forty to one. We moved off again on our weary way, river crossing cropping up too often. We then hit a dirt road. It was a beautiful day to start with and then a clap of thunder and torrential rain. The road turned into mud and small previously dry river beds turned into raging torrents and wading fords became treacherous.

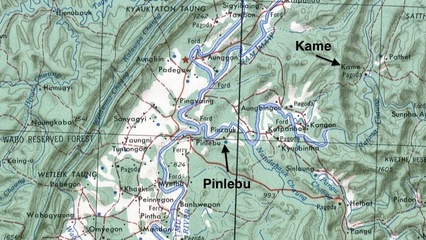

By dark it had stopped and so did we. We were very wet and miserable, but tea had to be made somehow, and all the wood was saturated. The gelignite we carried came in handy as it burns very fiercely but does not explode without a detonator, so we got the wet bamboo alight. Having had a feed of biscuits and raisins and almonds, plus a mess tin of tea, we set off again. We were still heavy legged and under fed as we were mostly on rice and water awaiting a ration drop which was some days off. We had a definite target this day, Pinlebu. Our job was to engage the Japs and keep them occupied whilst the demolition squad blew up the bridges in the valley. We moved in close and asked the R.A.F. to drop some bombs which they did with limited success, but it upset the Japs and things became unpleasant for us.

Having to cook rice was a handicap as you were fixed in one place too long which gave the Japs time to move in on us. At one stage they moved right in on us and we suffered some casualties. For cooking we worked in pairs one tending the fire and cooking and the other doing look out or cutting bamboo for mule fodder.

All of a sudden bullets were flying all around us, so the bugle was sounded to disperse which was normal procedure, so it was pack up and load mules with great speed and disappear in small groups to re-group at a prearranged rendezvous. On our way we past through a leper village which caused some alarm to them as they were isolated. After much hard marching we reformed near the village of Kame.

Whilst we were at Tonmakeng news came in of a Jap working party twenty five miles away at Linglamong. I was in the party sent down to attack them. It was a very hard march through elephant grass at times and waterless country. We arrived very tired and keyed up for our first encounter, but on arrival found they had gone. We had to dig deep into a dry river bed to get water and it takes a long time to seep in. Having brewed up and fed man and mule we marched back to Tonmakeng only to be told we were off again.

It was a game trail over the escarpment in waterless country. Hard work all the way and much clearing of bamboo to be done. The Burmese were able to get some water for themselves from some of the bamboo, but its knowing what type to look for. You need to be born there to learn the jungle. Firelighting was another art of theirs with flint and tinder.

The lie of the land was very deceiving, as you have to walk up and down the contours, steep up and steep down hence thirty six miles was only about twenty miles forward. When we did reach the flatter area we came to the Yu Yu River which was bad for the mules as no way can you stop a thirsty mule from drinking especially in the dark and everybody physically exhausted. The result was mules with colic. Once again the old story, you come from a farm Pte. Holland and know about animals, you help treat them, so hours spent sticking medicine balls down their throats and keeping them moving till daylight. We took a few days rest in this area as the river came in handy for bathing and washing clothes.

We heard gunfire from time to time which took some of the picnic atmosphere out of the stay. Tension was rising now as we were due to attack Indawgy aerodrome and take it, but after the Burmese recce it was called off as we were out numbered forty to one. We moved off again on our weary way, river crossing cropping up too often. We then hit a dirt road. It was a beautiful day to start with and then a clap of thunder and torrential rain. The road turned into mud and small previously dry river beds turned into raging torrents and wading fords became treacherous.

By dark it had stopped and so did we. We were very wet and miserable, but tea had to be made somehow, and all the wood was saturated. The gelignite we carried came in handy as it burns very fiercely but does not explode without a detonator, so we got the wet bamboo alight. Having had a feed of biscuits and raisins and almonds, plus a mess tin of tea, we set off again. We were still heavy legged and under fed as we were mostly on rice and water awaiting a ration drop which was some days off. We had a definite target this day, Pinlebu. Our job was to engage the Japs and keep them occupied whilst the demolition squad blew up the bridges in the valley. We moved in close and asked the R.A.F. to drop some bombs which they did with limited success, but it upset the Japs and things became unpleasant for us.

Having to cook rice was a handicap as you were fixed in one place too long which gave the Japs time to move in on us. At one stage they moved right in on us and we suffered some casualties. For cooking we worked in pairs one tending the fire and cooking and the other doing look out or cutting bamboo for mule fodder.

All of a sudden bullets were flying all around us, so the bugle was sounded to disperse which was normal procedure, so it was pack up and load mules with great speed and disappear in small groups to re-group at a prearranged rendezvous. On our way we past through a leper village which caused some alarm to them as they were isolated. After much hard marching we reformed near the village of Kame.

Frank's memoir continues:

These people (the villagers of Kame) were Burmans as opposed to Chins and Karens and they were quite hostile towards us. Perhaps it was fear of the Japs as they were quite unkind to any villages they thought maybe helping us. That night we set up ambushes on the paths leading into the village. We had to send a party back into the area we were forced to leave as some mules and equipment was left behind, this was a very nerve racking experience as you knew the Japs could be waiting for such an event, but all went well.

During the night the Japs came into Kame but they must have been warned by the villagers of our whereabouts and withdrew again.

In the morning we were left behind to put down a road block whilst the Column went east to collect a ration drop. We put out listening posts for two hours and then got ready to withdraw, as we moved onto the path all hell broke loose. The Japs had formed an ambush near the village which we had to pass through. The officer we had with us said it was our own fire, fix bayonets and advance which we did only to run into the Japs at point blank range.

The officer and my mate Teddy Gale went down immediately in front of me. I was lucky and able to get off the path into the jungle where I met several of my platoon. The Japs now roughly knew where we were and opened up with two machine guns and made life very unpleasant for us. Our only chance was to move deeper into the jungle which we did and got away. Our next job was to try and find the Column, which we did for two days. We saw several Jap patrols out looking for us but our luck held. The decision was then made to head back to India which was a pre-arranged plan if things went wrong. With no food left and no map or compass it was quite a daunting prospect.

NB. The officer mentioned by Frank was Lieutenant William Thomas Callaghan, please click on the link below to see this man's CWGC details:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2506717/CALLAGHAN,%20WILLIAM%20THOMAS

For more information about the battle at Kame and the fate of Pte. Gale, please click on the following link and scroll down to the second story on that page: Pte. G. Gale

I thought it would be of some interest to this story to read Wingate's own account and view of the action around Pinlebu in early March 1943. Here is a condensed, paraphrased summary of his appraisal:

"I sent Column 8 off to Pinlebu to make the enemy believe that this was our main objective. In this we were successful. Intelligence had told us that the Japanese Garrison in the town was at double Company strength, with two more stationed at Wuntho. Allied bombing called in by our RAF Officers on the 4th March had been effective and the Japanese dispersed widely in organised defences covering several square miles.

Column 8 succeeded in attracting a good deal of attention and at one point even carried out a dispersal manoeuvre. The re-forming afterwards was also successful but for the loss of some of our Other Ranks. I ordered the continued ambush of tracks leading both North and East of Pinlebu to cover our main objective, a large Supply Drop planned for the 6th.

It was clear to me from these engagements with the enemy, that Column 8 had much to learn in the way of ordinary Infantry tactics and positioning, in this respect they were inferior to the Japanese. Nevertheless, they were superior to the enemy in handling their nerve, movement through the jungle and the power of surprise.

Lieut. Colonel Cooke took charge of the supply dropping on the 6th. While it was proceeding, the sounds of Mortar and Machine Gun fire could be heard from the direction of Pinlebu as Column 8 went about their business. Their action had confused the Japanese and the enemies fear of engaging the column in the surrounding jungle had left the Supply Drop unmolested."

Frank Holland continues his account:

We were a party of nine but one chap was very ill with dysentery and you felt his days were over, but he made India his will power to live was unbelievable. Our first big task was to find a village to get some food. On the second day we saw one across a paddy field which was full of golden pheasants, but we couldn't shoot any as the Japs were all around. So we very nervously walked across to the village and the people were friendly. With sign language we ask for food. They took us into their hut which meant walking up a sloping pole with notches for footholds, not easy in Army boots. Their huts are built on poles about eight feet off the ground. They gave us a meal of cooked rice and sold us some uncooked rice to take with us, but we got a bit alarmed when they insisted on cleaning it as we had seen two youths slip out of the village and we wondered if they had gone to tell the Japs we were there.

They later returned with two chickens and some eggs for us and we were very soon on our way again.

We moved along a stream into nice country. Teak forest and nearly free of bamboo. The same old story of north Burma up and down hills. We were getting quite confident by afternoon, when suddenly we saw rifles levelled at us from all around, but as luck would have it they turned out to be Gurkhas from Column 4. They, like us had been caught in an ambush at Pinbon. We had a chat with their Commander, Major Bromhead and he told us they were badly split up, as during the ambush they had shot one another up by mistake. So he had decided to take them back to India as they lacked experience in our kind or warfare, but he was waiting to see if anymore would come in.

I was asked to kill a bullock for them to eat. I agreed but was quite taken back when told I must not shoot it as the Japs were too near, so I had to poll axe it and skin it. Before we could eat any of the meat we were asked if we would help keep look out on the road, as they had very few British troops in the Column. We said we put down a road block and look out for Gurkha stragglers and come back and join them at first light. Just after dark we heard movement across the road in the jungle, so half of us went to intercept. It was a very uncomfortable as we could hear talking but not English. We got in close and recognized them as Gurkhas. We showed them back into their Column and were asked if we would stay out there till morning. We moved back in the morning but they had all gone so we got none of the meat.

So back to our original plan, west towards India. We plodded on till near dark and then brewed up tea and boiled rice. Rice and water does not do a lot for you. It fills you up but leaves you starving and by now the longing for sugar was haunting us. As soon as we had fed we lay down to sleep just as we were, no beds to make and there was no point in putting out guards as the Japs didn’t move off the tracks, or not very far and we were too worn out to make any noise. At first light we lit fires and made tea, by now tea was getting very short, so it was a pinch of tea leaves to a pint of water. Our next consideration was to find water and fill our bottles. At that time of year there was a lot of waterless country.

The few days that followed took much the same pattern. Our sick chap was very weak by now and was in need of a lot of water and help to get started, but he had a lot of guts to even get off the ground, to face another days marching would have seen many men off.

We eventually came down to a river which was very pleasant but very dangerous for us as the Japs patrolled these areas frequently. But we had to go into a village soon as the rice was nearly gone. Some of the Daks (houses) were worth seeing all carved teak real works of art. The village we went into turned out to be very friendly and helpful. They supplied us with plenty of rice so we left with heavy loads. They also gave us two guides to take us to the escarpment. We paid them well in silver rupees, money given to us by the Army before leaving India with the express purpose to keep the Burmese on our side.

These two guides started off at a brisk pace which we found hard to follow with a sick bloke to help along. I think they were eager to get away from their village as they would suffer badly at the hands of the Japs for helping us. They soon realized our problem and were very helpful. I wish they could have stayed longer as we could have learned a lot from them. They know which bamboo holds water fit to drink also various things to eat. They left us on a path which led west into the escarpment. We paid them and said our farewell. This is the time you wished you could speak their language.

We didn’t do many miles before we started to climb and care of water became vital as we knew it was waterless ground ahead from the lessons we learned on the way in. As you get higher you feel that you ought to be able to see out, but no way, the trees and bamboo still surrounds you. Once, we saw the Dakotas fly overhead going to drop supplies on some column, it made us feel even more isolated and forgotten.

The days past as routine, more walking, sleep and hunger. The loss of weight and energy was obvious and tempers were short at times. But one thing stood out, the will to live and get back to India.

NB. Below are two images, a map of the Pinlebu/Kame Road area and the other a photograph of Pte. George Gale. Please click on any of the images to enlarge.

These people (the villagers of Kame) were Burmans as opposed to Chins and Karens and they were quite hostile towards us. Perhaps it was fear of the Japs as they were quite unkind to any villages they thought maybe helping us. That night we set up ambushes on the paths leading into the village. We had to send a party back into the area we were forced to leave as some mules and equipment was left behind, this was a very nerve racking experience as you knew the Japs could be waiting for such an event, but all went well.

During the night the Japs came into Kame but they must have been warned by the villagers of our whereabouts and withdrew again.

In the morning we were left behind to put down a road block whilst the Column went east to collect a ration drop. We put out listening posts for two hours and then got ready to withdraw, as we moved onto the path all hell broke loose. The Japs had formed an ambush near the village which we had to pass through. The officer we had with us said it was our own fire, fix bayonets and advance which we did only to run into the Japs at point blank range.

The officer and my mate Teddy Gale went down immediately in front of me. I was lucky and able to get off the path into the jungle where I met several of my platoon. The Japs now roughly knew where we were and opened up with two machine guns and made life very unpleasant for us. Our only chance was to move deeper into the jungle which we did and got away. Our next job was to try and find the Column, which we did for two days. We saw several Jap patrols out looking for us but our luck held. The decision was then made to head back to India which was a pre-arranged plan if things went wrong. With no food left and no map or compass it was quite a daunting prospect.

NB. The officer mentioned by Frank was Lieutenant William Thomas Callaghan, please click on the link below to see this man's CWGC details:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2506717/CALLAGHAN,%20WILLIAM%20THOMAS

For more information about the battle at Kame and the fate of Pte. Gale, please click on the following link and scroll down to the second story on that page: Pte. G. Gale

I thought it would be of some interest to this story to read Wingate's own account and view of the action around Pinlebu in early March 1943. Here is a condensed, paraphrased summary of his appraisal:

"I sent Column 8 off to Pinlebu to make the enemy believe that this was our main objective. In this we were successful. Intelligence had told us that the Japanese Garrison in the town was at double Company strength, with two more stationed at Wuntho. Allied bombing called in by our RAF Officers on the 4th March had been effective and the Japanese dispersed widely in organised defences covering several square miles.

Column 8 succeeded in attracting a good deal of attention and at one point even carried out a dispersal manoeuvre. The re-forming afterwards was also successful but for the loss of some of our Other Ranks. I ordered the continued ambush of tracks leading both North and East of Pinlebu to cover our main objective, a large Supply Drop planned for the 6th.

It was clear to me from these engagements with the enemy, that Column 8 had much to learn in the way of ordinary Infantry tactics and positioning, in this respect they were inferior to the Japanese. Nevertheless, they were superior to the enemy in handling their nerve, movement through the jungle and the power of surprise.

Lieut. Colonel Cooke took charge of the supply dropping on the 6th. While it was proceeding, the sounds of Mortar and Machine Gun fire could be heard from the direction of Pinlebu as Column 8 went about their business. Their action had confused the Japanese and the enemies fear of engaging the column in the surrounding jungle had left the Supply Drop unmolested."

Frank Holland continues his account:

We were a party of nine but one chap was very ill with dysentery and you felt his days were over, but he made India his will power to live was unbelievable. Our first big task was to find a village to get some food. On the second day we saw one across a paddy field which was full of golden pheasants, but we couldn't shoot any as the Japs were all around. So we very nervously walked across to the village and the people were friendly. With sign language we ask for food. They took us into their hut which meant walking up a sloping pole with notches for footholds, not easy in Army boots. Their huts are built on poles about eight feet off the ground. They gave us a meal of cooked rice and sold us some uncooked rice to take with us, but we got a bit alarmed when they insisted on cleaning it as we had seen two youths slip out of the village and we wondered if they had gone to tell the Japs we were there.

They later returned with two chickens and some eggs for us and we were very soon on our way again.

We moved along a stream into nice country. Teak forest and nearly free of bamboo. The same old story of north Burma up and down hills. We were getting quite confident by afternoon, when suddenly we saw rifles levelled at us from all around, but as luck would have it they turned out to be Gurkhas from Column 4. They, like us had been caught in an ambush at Pinbon. We had a chat with their Commander, Major Bromhead and he told us they were badly split up, as during the ambush they had shot one another up by mistake. So he had decided to take them back to India as they lacked experience in our kind or warfare, but he was waiting to see if anymore would come in.

I was asked to kill a bullock for them to eat. I agreed but was quite taken back when told I must not shoot it as the Japs were too near, so I had to poll axe it and skin it. Before we could eat any of the meat we were asked if we would help keep look out on the road, as they had very few British troops in the Column. We said we put down a road block and look out for Gurkha stragglers and come back and join them at first light. Just after dark we heard movement across the road in the jungle, so half of us went to intercept. It was a very uncomfortable as we could hear talking but not English. We got in close and recognized them as Gurkhas. We showed them back into their Column and were asked if we would stay out there till morning. We moved back in the morning but they had all gone so we got none of the meat.

So back to our original plan, west towards India. We plodded on till near dark and then brewed up tea and boiled rice. Rice and water does not do a lot for you. It fills you up but leaves you starving and by now the longing for sugar was haunting us. As soon as we had fed we lay down to sleep just as we were, no beds to make and there was no point in putting out guards as the Japs didn’t move off the tracks, or not very far and we were too worn out to make any noise. At first light we lit fires and made tea, by now tea was getting very short, so it was a pinch of tea leaves to a pint of water. Our next consideration was to find water and fill our bottles. At that time of year there was a lot of waterless country.

The few days that followed took much the same pattern. Our sick chap was very weak by now and was in need of a lot of water and help to get started, but he had a lot of guts to even get off the ground, to face another days marching would have seen many men off.

We eventually came down to a river which was very pleasant but very dangerous for us as the Japs patrolled these areas frequently. But we had to go into a village soon as the rice was nearly gone. Some of the Daks (houses) were worth seeing all carved teak real works of art. The village we went into turned out to be very friendly and helpful. They supplied us with plenty of rice so we left with heavy loads. They also gave us two guides to take us to the escarpment. We paid them well in silver rupees, money given to us by the Army before leaving India with the express purpose to keep the Burmese on our side.

These two guides started off at a brisk pace which we found hard to follow with a sick bloke to help along. I think they were eager to get away from their village as they would suffer badly at the hands of the Japs for helping us. They soon realized our problem and were very helpful. I wish they could have stayed longer as we could have learned a lot from them. They know which bamboo holds water fit to drink also various things to eat. They left us on a path which led west into the escarpment. We paid them and said our farewell. This is the time you wished you could speak their language.

We didn’t do many miles before we started to climb and care of water became vital as we knew it was waterless ground ahead from the lessons we learned on the way in. As you get higher you feel that you ought to be able to see out, but no way, the trees and bamboo still surrounds you. Once, we saw the Dakotas fly overhead going to drop supplies on some column, it made us feel even more isolated and forgotten.

The days past as routine, more walking, sleep and hunger. The loss of weight and energy was obvious and tempers were short at times. But one thing stood out, the will to live and get back to India.

NB. Below are two images, a map of the Pinlebu/Kame Road area and the other a photograph of Pte. George Gale. Please click on any of the images to enlarge.

Frank's story continues:

One day we came across elephant droppings on the path which didn’t mean much to us then. But after getting back to India we learned from others this was quite often a sign of a Jap patrol.

Our sick chap by now was very weak and ill, he needed help to get along, all we could do to help him was give him lots of water, which meant more for us to carry, but less for us to drink ourselves. But nobody complained about that. We kept climbing up and down, but our westward progress was slow. The same old annoying thing no matter how high up you got you couldn’t see out over the landscape. The climb was over five thousand feet and then we started down again to find some very nice streams but no food. We found some very green bananas and tomatoes, but even stewed they were very poor eating.

Our next delaying thing was swamps. Very long detours had to be made to get around them, we are talking of miles and with no maps we had no idea which was the quickest route. Just to stay alive and get out of Burma was the driving force.

We plodded along day after day same old routine. Then one morning we saw rifles levelled at us again which was very alarming. The first thought was, 'not this and be taken prisoner now.' But they recognized we were British as they had been warned to expect some returning troops, which was the last thing we looked like, with our long beards we were ragged wrecks. It turned out to be a patrol of the Seaforth Highlanders patrolling the banks of the Chindwin.

NB. The Seaforth Highlanders had escorted the Chindit Columns to the Chindwin River on the outward journey in February and now patrolled the river banks looking for lost Chindits and stragglers from the expedition.

They showed us the path to the river bank where Burmese boatmen took us across in wooden dugouts. We were near Sittang about twenty five miles south of Tonhe the place where we crossed on the way in. The Seaforths gave us some sugar and tinned milk to go in our tea. It was heaven. We tried blasting (using grenades) the Chindwin for fish but the current was so strong that the stunned fish were a long way down stream before reaching the surface.

We settled down that night most relieved as we were safe, but we knew we had two more days marching before we reached Tamu. If it had been two weeks we wouldn’t have cared.

That night we couldn’t sleep as we itched all over, but when we could get advice we were told it was the sudden intake of sugar in the blood. We carried on over very rough tracks till we reached Divisional Headquarters at Tamu. This was when our troubles started and all through kindness. They gave us heaps of food including new baked bread at the field kitchen, lots of tinned fruit and stews and our shrunken stomachs rebelled. We spent much time on the toilet. Our first task after food was to shave off our beards and bath. We found ticks had taken full advantage of us and got very fat at our expense. We had to stay there till we were fit to travel down the road by lorry. We said we would rather walk, but the powers that be decided we maybe needed back in Burma. Eventually we set off, but the journey wasn’t exciting as we had seen it all before.

We did get one big surprise one morning, a party of our column were sitting beside the road and it turned out to be Peter Bennett my Platoon Commander and what was left of the platoon. He was more surprised than me, as he had posted us missing or dead.

We moved on and eventually arrived at Imphal. We were put in Bashers (usually a bamboo structure with a thatched roof) quite luxury after nearly a year living without a roof over our head. We had a temple in the middle of the village still used by the Indians.

We were visited by Generals downward and asked many questions on what we had learned about the Japs and what we thought of the rations, also the equipment, as we used Everest type packs not Army standard equipment.

From now on we were given all the food we could eat. I took on the cooking as it was boring doing nothing. Meals were quite a social gathering. Breakfast as and when anyone arrived. Sometimes we cooked in the middle of the night as various small parties arrived. One day Joe Coughlan walked in, he was a Captain in my Column, but was brought down to a Private by Wingate for getting fourteen of his patrol killed in an ambush, not his fault just bad maps. He was transferred to 5 Column where Ferguson made him a Sergeant. Much later he became our Adjutant and his rank of Captain was restored.

NB: Captain Coughlan had missed a rendezvous point during the large supply drop at the village of Baw, he was demoted by Wingate for failing to secure the road leading to the village against the Japanese.

While we were at Imphal Jap aircraft came in one day and bombed us using anti-personnel bombs, not very pleasant but we escaped injury. The villagers suffered badly as they wouldn’t go into the trenches or get down. As soon as the last bomb dropped we rushed to the hospital as they had caught the full impact. Fires and unexploded bombs were a problem there.

The Life Magazine camera man was still there photographing, he never did take cover. They are a breed on their own. He died in 1944 with Wingate in the plane crash.

NB: This was possibly the News Chronicle war correspondent, Stuart Emeny, who did indeed die with Wingate in that fateful plane crash on March 24th 1944.

We were allowed to send a telegram home from Imphal to say we had survived. This was via field post office and free. I was quite surprised how quick it was. I got a reply in 48 hours which is an amazing fact, thinking of the distance and a war on.

After a while we left Imphal and went back to Jhansi our original embarkation place. There we were issued new clothes and equipment. We all had an interview and asked to go back in again with a new unit, promotion would be automatic and we would help train the new unit. I’m afraid there were not many volunteers as our health wasn’t too special. Officers had no choice they had to go.

One day we came across elephant droppings on the path which didn’t mean much to us then. But after getting back to India we learned from others this was quite often a sign of a Jap patrol.

Our sick chap by now was very weak and ill, he needed help to get along, all we could do to help him was give him lots of water, which meant more for us to carry, but less for us to drink ourselves. But nobody complained about that. We kept climbing up and down, but our westward progress was slow. The same old annoying thing no matter how high up you got you couldn’t see out over the landscape. The climb was over five thousand feet and then we started down again to find some very nice streams but no food. We found some very green bananas and tomatoes, but even stewed they were very poor eating.

Our next delaying thing was swamps. Very long detours had to be made to get around them, we are talking of miles and with no maps we had no idea which was the quickest route. Just to stay alive and get out of Burma was the driving force.

We plodded along day after day same old routine. Then one morning we saw rifles levelled at us again which was very alarming. The first thought was, 'not this and be taken prisoner now.' But they recognized we were British as they had been warned to expect some returning troops, which was the last thing we looked like, with our long beards we were ragged wrecks. It turned out to be a patrol of the Seaforth Highlanders patrolling the banks of the Chindwin.

NB. The Seaforth Highlanders had escorted the Chindit Columns to the Chindwin River on the outward journey in February and now patrolled the river banks looking for lost Chindits and stragglers from the expedition.

They showed us the path to the river bank where Burmese boatmen took us across in wooden dugouts. We were near Sittang about twenty five miles south of Tonhe the place where we crossed on the way in. The Seaforths gave us some sugar and tinned milk to go in our tea. It was heaven. We tried blasting (using grenades) the Chindwin for fish but the current was so strong that the stunned fish were a long way down stream before reaching the surface.

We settled down that night most relieved as we were safe, but we knew we had two more days marching before we reached Tamu. If it had been two weeks we wouldn’t have cared.

That night we couldn’t sleep as we itched all over, but when we could get advice we were told it was the sudden intake of sugar in the blood. We carried on over very rough tracks till we reached Divisional Headquarters at Tamu. This was when our troubles started and all through kindness. They gave us heaps of food including new baked bread at the field kitchen, lots of tinned fruit and stews and our shrunken stomachs rebelled. We spent much time on the toilet. Our first task after food was to shave off our beards and bath. We found ticks had taken full advantage of us and got very fat at our expense. We had to stay there till we were fit to travel down the road by lorry. We said we would rather walk, but the powers that be decided we maybe needed back in Burma. Eventually we set off, but the journey wasn’t exciting as we had seen it all before.

We did get one big surprise one morning, a party of our column were sitting beside the road and it turned out to be Peter Bennett my Platoon Commander and what was left of the platoon. He was more surprised than me, as he had posted us missing or dead.

We moved on and eventually arrived at Imphal. We were put in Bashers (usually a bamboo structure with a thatched roof) quite luxury after nearly a year living without a roof over our head. We had a temple in the middle of the village still used by the Indians.

We were visited by Generals downward and asked many questions on what we had learned about the Japs and what we thought of the rations, also the equipment, as we used Everest type packs not Army standard equipment.

From now on we were given all the food we could eat. I took on the cooking as it was boring doing nothing. Meals were quite a social gathering. Breakfast as and when anyone arrived. Sometimes we cooked in the middle of the night as various small parties arrived. One day Joe Coughlan walked in, he was a Captain in my Column, but was brought down to a Private by Wingate for getting fourteen of his patrol killed in an ambush, not his fault just bad maps. He was transferred to 5 Column where Ferguson made him a Sergeant. Much later he became our Adjutant and his rank of Captain was restored.

NB: Captain Coughlan had missed a rendezvous point during the large supply drop at the village of Baw, he was demoted by Wingate for failing to secure the road leading to the village against the Japanese.

While we were at Imphal Jap aircraft came in one day and bombed us using anti-personnel bombs, not very pleasant but we escaped injury. The villagers suffered badly as they wouldn’t go into the trenches or get down. As soon as the last bomb dropped we rushed to the hospital as they had caught the full impact. Fires and unexploded bombs were a problem there.

The Life Magazine camera man was still there photographing, he never did take cover. They are a breed on their own. He died in 1944 with Wingate in the plane crash.

NB: This was possibly the News Chronicle war correspondent, Stuart Emeny, who did indeed die with Wingate in that fateful plane crash on March 24th 1944.

We were allowed to send a telegram home from Imphal to say we had survived. This was via field post office and free. I was quite surprised how quick it was. I got a reply in 48 hours which is an amazing fact, thinking of the distance and a war on.

After a while we left Imphal and went back to Jhansi our original embarkation place. There we were issued new clothes and equipment. We all had an interview and asked to go back in again with a new unit, promotion would be automatic and we would help train the new unit. I’m afraid there were not many volunteers as our health wasn’t too special. Officers had no choice they had to go.

The journal goes on:

Before too long we were sent to Bombay on leave. During which time we sorted dead members kit and sent personal effects home to their families, very depressing and the numbers very very many. We sent parcels home to our own families when we could get parcel permits, tea was the favourite. We were only allowed a few permits. A lot of time was spent swimming at Beach Candy Pool, an indoor and outdoor sea water swimming pool. They laid on various tours, one included a tour of Sunlight soap factory.

After a month we set off for Karachi. During the journey I developed malaria and by the time we arrived I was an ambulance case and went to hospital. Your first dose of malaria really puts you down, temperatures you’ve never heard of, deliriums and the quinine playing havoc with everything. The hospital in Karachi was a nice place and they did some important operations in the main building. Malaria, jaundice, typhoid and dysentery cases were kept in detached huts, but not isolated from one another.

If you could walk with malaria you had to fetch your bedding and mattress from the store and make the bed. There was one bright thing to it, malaria cases were given one bottle of beer each day for free. Back in barracks you were allowed one bottle per month on a coupon which you paid for. Napier Barracks were old regular Army barracks. They were two storey brick buildings with verandahs upstairs and down to draw the air in so we had no fans or punkhas.

Life was pretty good there as we so called convalescents had been built up to full fitness. There was great deal of regimentation as we did Government House guard duties and escorts for visiting notabilities. I was approached to become a cook after my spell of cooking at Imphal but I declined and went into Intelligence. The best move I could have made. We were given a lot of freedom. We did days away off into the Sind Desert on reconnaissance work, a vast deserted and arid place, but some very interesting bits. We used to go hundreds of miles sometimes, over near the Afganistan border. We managed a lot of swimming in the Arabian Sea. Sometimes went to Pir Mango a temple village with a hot water spring. They had a big Leper Colony there. They also had a big crocodile pool at the temple where it was said they used to feed them on human sacrifices, but they were making money, because when we went there, they wanted money to let you see them eat and it was a dead goat.

One of our roles was to train officers just out from England all about long range penetration ready for Burma. They had to imagine they were in the jungle and we dumped food and water for them in various places and they had to get through our defences. It didn’t teach them much about jungle warfare but it got them fit after a few hundred miles walking.

Then for a change we went to Hyderabad Sind for three months, a very hot and arid place. We found an area of plum trees covered green, it was a small depression, wonderful to come back to after hours out in rock covered desert. But it was too good to last, one night a few claps of thunder and torrential rain and in no time we were in five feet of water. We had to get out fast and in first light moved to high ground. I enjoyed the three months there.

When you got down to the banks of the Indus, they grew wonderful crops of wheat, oats, barley and millet. The fields were hand weeded and irrigated, with the water being lifted by a wooden wheel turned by camels. We eventually returned to Karachi and did a various bits of training, such as river crossing in Chinna Creek, a sea channel and mango swamp. Some weekends we hired a dhow and sailed across to Manora Island for a day, a beautiful sandy beach, swimming is a bit dangerous during the monsoon. The monsoon is very short in Karachi with rainfall of about three inches per year and all over in a week.

Before too long we were sent to Bombay on leave. During which time we sorted dead members kit and sent personal effects home to their families, very depressing and the numbers very very many. We sent parcels home to our own families when we could get parcel permits, tea was the favourite. We were only allowed a few permits. A lot of time was spent swimming at Beach Candy Pool, an indoor and outdoor sea water swimming pool. They laid on various tours, one included a tour of Sunlight soap factory.

After a month we set off for Karachi. During the journey I developed malaria and by the time we arrived I was an ambulance case and went to hospital. Your first dose of malaria really puts you down, temperatures you’ve never heard of, deliriums and the quinine playing havoc with everything. The hospital in Karachi was a nice place and they did some important operations in the main building. Malaria, jaundice, typhoid and dysentery cases were kept in detached huts, but not isolated from one another.

If you could walk with malaria you had to fetch your bedding and mattress from the store and make the bed. There was one bright thing to it, malaria cases were given one bottle of beer each day for free. Back in barracks you were allowed one bottle per month on a coupon which you paid for. Napier Barracks were old regular Army barracks. They were two storey brick buildings with verandahs upstairs and down to draw the air in so we had no fans or punkhas.

Life was pretty good there as we so called convalescents had been built up to full fitness. There was great deal of regimentation as we did Government House guard duties and escorts for visiting notabilities. I was approached to become a cook after my spell of cooking at Imphal but I declined and went into Intelligence. The best move I could have made. We were given a lot of freedom. We did days away off into the Sind Desert on reconnaissance work, a vast deserted and arid place, but some very interesting bits. We used to go hundreds of miles sometimes, over near the Afganistan border. We managed a lot of swimming in the Arabian Sea. Sometimes went to Pir Mango a temple village with a hot water spring. They had a big Leper Colony there. They also had a big crocodile pool at the temple where it was said they used to feed them on human sacrifices, but they were making money, because when we went there, they wanted money to let you see them eat and it was a dead goat.

One of our roles was to train officers just out from England all about long range penetration ready for Burma. They had to imagine they were in the jungle and we dumped food and water for them in various places and they had to get through our defences. It didn’t teach them much about jungle warfare but it got them fit after a few hundred miles walking.

Then for a change we went to Hyderabad Sind for three months, a very hot and arid place. We found an area of plum trees covered green, it was a small depression, wonderful to come back to after hours out in rock covered desert. But it was too good to last, one night a few claps of thunder and torrential rain and in no time we were in five feet of water. We had to get out fast and in first light moved to high ground. I enjoyed the three months there.

When you got down to the banks of the Indus, they grew wonderful crops of wheat, oats, barley and millet. The fields were hand weeded and irrigated, with the water being lifted by a wooden wheel turned by camels. We eventually returned to Karachi and did a various bits of training, such as river crossing in Chinna Creek, a sea channel and mango swamp. Some weekends we hired a dhow and sailed across to Manora Island for a day, a beautiful sandy beach, swimming is a bit dangerous during the monsoon. The monsoon is very short in Karachi with rainfall of about three inches per year and all over in a week.

Malaria was still pestering me, in and out of hospital quite regular. We buried a few of our lads as a result of it. We agreed to have photos taken of the graves and sent back to relatives, small comfort but we always got letters of thanks back.

NB: By matching up the date of death and with location of burial in Karachi War Cemetery, I believe the following men all died from malaria as Frank described:

George Francis Alcock

Francis Ball

Thomas Charles Grigg

William George Jones

George Thomas Puckett