Flight-Lieutenant John Redman

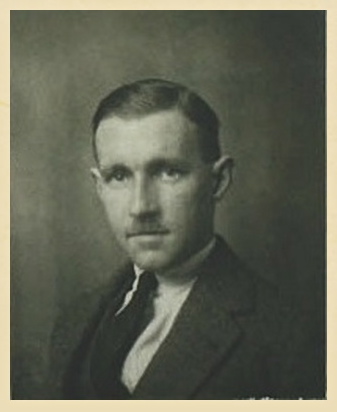

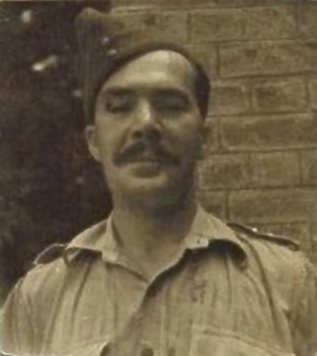

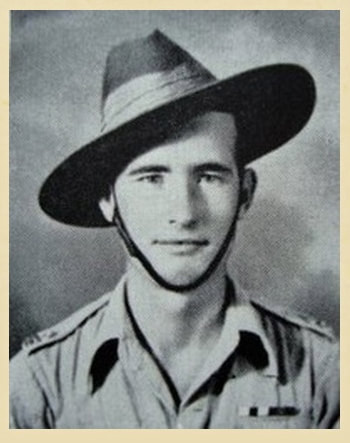

John Redman, circa June 1940.

John Redman, circa June 1940.

John Redman, the son of Samuel and Anna Redman was born on the 1st February 1915 in West Derby, a northern suburb of Liverpool. He became a Pilot-Officer in the RAF taking up a Short Service Commission in February 1939 and was posted to 245 Squadron at Leconfield in Yorkshire on 6th November the same year. P/O 41952 Redman was involved in the aerial protection of the evacuating British Forces from the beaches of Dunkirk, shooting down a ME109 over the town on the 1st June 1940.

On 16th September 1940, he was posted to 43 Squadron at Usworth near Sunderland and then moved to 257 Squadron at Martlesham Heath in Suffolk on 22nd September. After clashing with a number of ME109’s over Deal on 12th October, John crash-landed at Saffrey Farm, near Selling in Kent, but thankfully was unhurt. John then took a posting overseas. Initially serving with convoys, as a pilot flying the Sea Hurricane MK1A launched from the bows of merchant ships by catapult. It is possible that the ship that John was serving aboard was torpedoed in the late summer of 1941.

In 1942 it is known the he was posted to Gibraltar, the British Overseas Territory located at the foot of the Iberian Peninsula, but the nature of this part of his service is unclear. What we can be sure of, is that by the end of 1942, John was stationed in India and subsequently volunteered for a special mission, acting as Air Liaison for the first Wingate expedition in 1943 and codenamed Operation Longcloth.

Before we continue with this story, I would like to include some other information about John Redman, as compiled by his nephew Robert Hunter. I was interested to read what Robert had to say about his uncle, which he included in response to a question on the RAF Commands Forum in September 2008.

As I type this I am watched over by a 1941 portrait of John beside my computer, he is in his RAF uniform. John was born in Liverpool on the 1st February 1915 and died in Burma on or about 20th April 1943. Prior to this he served with 245 Squadron from 6/11/39; 43 Squadron from 16/9/40; and then 257 Squadron from 22/9/40. He married Catherine Audrey Kelly on the 26th October 1940 at Fenham, which is a suburb of Newcastle-upon-Tyne. The service was conducted by his own father, Canon Samuel Redman at St James' and St Basil's Church, Fenham.

John took a posting overseas. Initially, I understand, he served with convoys, as a pilot flying Sea Hurricanes, I believe he may have been serving on the SS Empire Hudson, which was part of convoy SC42 and was torpedoed at 09:57 hours on the 10th September 1941 off the coast of Greenland, by U-82. Survivors were rescued by SS Baron Ramsay. The next information I have jumps to his posting as a RAF Liaison Officer in Orde Wingate's 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, preparing for their first campaign into Burma in 1943. This was a disastrous campaign, and John was last seen allegedly helping a wounded man under Japanese attack on the 20th April. He has no known grave.

I never knew John, but am immensely proud that he is commemorated on the Battle of Britain Memorial by the Thames, as well as on the Singapore Memorial at Kranji War Cemetery. He was remembered by my late mother as full of life and adventure. I hope this is of interest to you. I have never found anyone who could tell me anything about John, other than family, and some of the above I've dug up via internet research. I have one or two of his possessions, and I try and keep his memory alive, remembering him each Armistice Day as someone I wish I could have met.

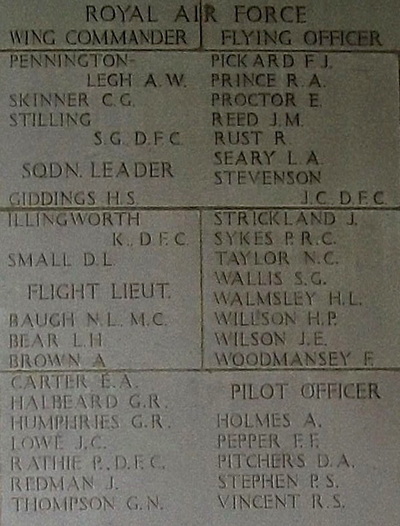

Seen below is a wonderful photograph of a group of officers, including John Redman, from 245 Squadron, taken in June 1940. This image can be found, along with other information about Flight-Lieutenant Redman on the Battle of Britain London Monument website. My thanks go to Edward McManus for allowing me to reproduce the image on these website pages.

On 16th September 1940, he was posted to 43 Squadron at Usworth near Sunderland and then moved to 257 Squadron at Martlesham Heath in Suffolk on 22nd September. After clashing with a number of ME109’s over Deal on 12th October, John crash-landed at Saffrey Farm, near Selling in Kent, but thankfully was unhurt. John then took a posting overseas. Initially serving with convoys, as a pilot flying the Sea Hurricane MK1A launched from the bows of merchant ships by catapult. It is possible that the ship that John was serving aboard was torpedoed in the late summer of 1941.

In 1942 it is known the he was posted to Gibraltar, the British Overseas Territory located at the foot of the Iberian Peninsula, but the nature of this part of his service is unclear. What we can be sure of, is that by the end of 1942, John was stationed in India and subsequently volunteered for a special mission, acting as Air Liaison for the first Wingate expedition in 1943 and codenamed Operation Longcloth.

Before we continue with this story, I would like to include some other information about John Redman, as compiled by his nephew Robert Hunter. I was interested to read what Robert had to say about his uncle, which he included in response to a question on the RAF Commands Forum in September 2008.

As I type this I am watched over by a 1941 portrait of John beside my computer, he is in his RAF uniform. John was born in Liverpool on the 1st February 1915 and died in Burma on or about 20th April 1943. Prior to this he served with 245 Squadron from 6/11/39; 43 Squadron from 16/9/40; and then 257 Squadron from 22/9/40. He married Catherine Audrey Kelly on the 26th October 1940 at Fenham, which is a suburb of Newcastle-upon-Tyne. The service was conducted by his own father, Canon Samuel Redman at St James' and St Basil's Church, Fenham.

John took a posting overseas. Initially, I understand, he served with convoys, as a pilot flying Sea Hurricanes, I believe he may have been serving on the SS Empire Hudson, which was part of convoy SC42 and was torpedoed at 09:57 hours on the 10th September 1941 off the coast of Greenland, by U-82. Survivors were rescued by SS Baron Ramsay. The next information I have jumps to his posting as a RAF Liaison Officer in Orde Wingate's 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, preparing for their first campaign into Burma in 1943. This was a disastrous campaign, and John was last seen allegedly helping a wounded man under Japanese attack on the 20th April. He has no known grave.

I never knew John, but am immensely proud that he is commemorated on the Battle of Britain Memorial by the Thames, as well as on the Singapore Memorial at Kranji War Cemetery. He was remembered by my late mother as full of life and adventure. I hope this is of interest to you. I have never found anyone who could tell me anything about John, other than family, and some of the above I've dug up via internet research. I have one or two of his possessions, and I try and keep his memory alive, remembering him each Armistice Day as someone I wish I could have met.

Seen below is a wonderful photograph of a group of officers, including John Redman, from 245 Squadron, taken in June 1940. This image can be found, along with other information about Flight-Lieutenant Redman on the Battle of Britain London Monument website. My thanks go to Edward McManus for allowing me to reproduce the image on these website pages.

John Redman was posted to 77th Indian Infantry Brigade sometime in November 1942 and joined Chindit training at the Bharon Camp, located in the Central Provinces of India, with around 4 or 5 other RAF officers. All these men had volunteered to perform Air Liaison duties for the newly formed Special Force, which entailed radio communications with Air Supply at Rear Base, ground to air signalling during supply drops in the Burmese jungle and the selection and preparation of all supply drop locations, known as DZ's.

After his arrival at the Bharon Camp, John and the other men were met by the senior RAF Officer in 77th Brigade, Squadron Leader Cecil J. Longmore. After an initial debrief about the forthcoming operation, John was posted to Chindit Column no. 1, part of Southern Group and commanded by Major George Dunlop of the Royal Scots. 1 Column was made up of mostly Gurkha troops, with only a smattering of British personnel, including John as RAF Officer, his assistant, Sergeant Hayes, some Signalmen and a platoon of Commandos.

From the book, Wingate's Lost Brigade, by author Philip Chinnery:

As the year (1942) came to an end, 1 Column was brought up to strength with the arrival of some new blood, in the shape of Medical Officer Captain Norman Stocks, RAF Liaison Officer John Redman, the Animal Transport Officer Lt. John Fowler with the rest of the mules, and two young subalterns, 2nd Lieutenants Harvey and Wormald. They had to learn quickly as there were two river-crossing exercises planned and wireless training to be carried out by the newly arrived Signal Section.

Major Dunlop and his officers were called to Brigade Headquarters at Imphal and given their instructions by Wingate, which were short and very much to the point:

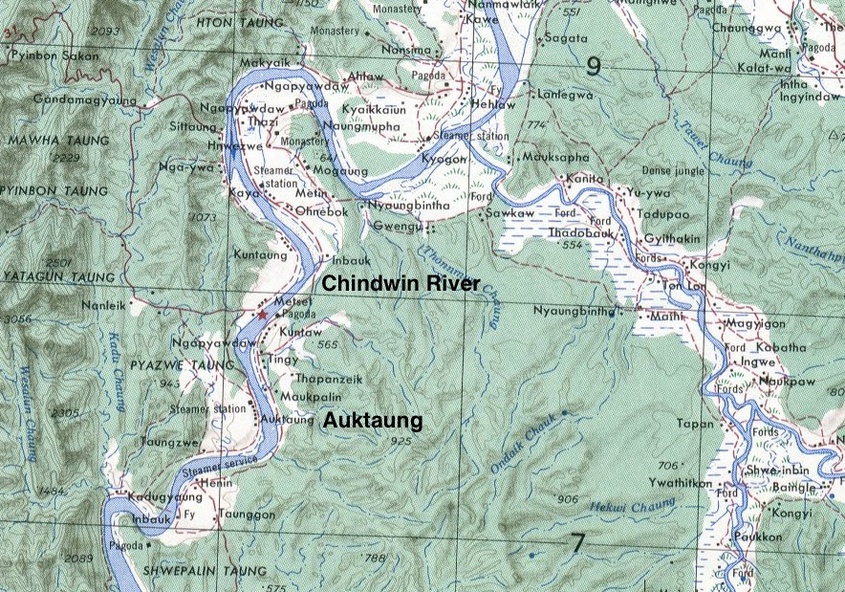

a) Together with 2 Column, they were to create a diversion to the south of the main objectives to be performed by Columns 3,4,5,7 and 8 (Northern Group). Their orders were to operate openly in the area to the east of Auktaung in order to draw off as many Japanese patrols as possible.

b) To then meet Brigadier Wingate, in the low ground beyond Tagaung on the east side of the Irrawaddy River in early March.

c) Or, having failed to make this meeting, to travel to Mongmit and encourage a rebellion amongst the Burmese against the Japanese occupation.

Southern Group crossed the Chindwin on 15/16th February 1943 at a place called Auktaung. Their orders were to march toward their prime objective, the rail station at Kyaikthin. They marched openly along well known local trails and paths and also received a large supply drop from the air, which must have announced their presence in the area to the Japanese. The decoy group were accompanied at this time by a Company of Sikh Mountain Artillery and a section of Seaforth Highlanders. This supplementary unit were to create a further diversion for Wingate by attacking the town of Pantha, alerting the enemy to the possibility that there might well be a full-scale re-invasion taking place. To all intents and purposes these decoy tactics succeeded and Northern Group did proceed unmolested toward their own specific objectives.

After his arrival at the Bharon Camp, John and the other men were met by the senior RAF Officer in 77th Brigade, Squadron Leader Cecil J. Longmore. After an initial debrief about the forthcoming operation, John was posted to Chindit Column no. 1, part of Southern Group and commanded by Major George Dunlop of the Royal Scots. 1 Column was made up of mostly Gurkha troops, with only a smattering of British personnel, including John as RAF Officer, his assistant, Sergeant Hayes, some Signalmen and a platoon of Commandos.

From the book, Wingate's Lost Brigade, by author Philip Chinnery:

As the year (1942) came to an end, 1 Column was brought up to strength with the arrival of some new blood, in the shape of Medical Officer Captain Norman Stocks, RAF Liaison Officer John Redman, the Animal Transport Officer Lt. John Fowler with the rest of the mules, and two young subalterns, 2nd Lieutenants Harvey and Wormald. They had to learn quickly as there were two river-crossing exercises planned and wireless training to be carried out by the newly arrived Signal Section.

Major Dunlop and his officers were called to Brigade Headquarters at Imphal and given their instructions by Wingate, which were short and very much to the point:

a) Together with 2 Column, they were to create a diversion to the south of the main objectives to be performed by Columns 3,4,5,7 and 8 (Northern Group). Their orders were to operate openly in the area to the east of Auktaung in order to draw off as many Japanese patrols as possible.

b) To then meet Brigadier Wingate, in the low ground beyond Tagaung on the east side of the Irrawaddy River in early March.

c) Or, having failed to make this meeting, to travel to Mongmit and encourage a rebellion amongst the Burmese against the Japanese occupation.

Southern Group crossed the Chindwin on 15/16th February 1943 at a place called Auktaung. Their orders were to march toward their prime objective, the rail station at Kyaikthin. They marched openly along well known local trails and paths and also received a large supply drop from the air, which must have announced their presence in the area to the Japanese. The decoy group were accompanied at this time by a Company of Sikh Mountain Artillery and a section of Seaforth Highlanders. This supplementary unit were to create a further diversion for Wingate by attacking the town of Pantha, alerting the enemy to the possibility that there might well be a full-scale re-invasion taking place. To all intents and purposes these decoy tactics succeeded and Northern Group did proceed unmolested toward their own specific objectives.

On the 2nd March Columns 1 and 2 had reached the outskirts of Kyaikthin, Major George Dunlop was given the order to blow up the railway bridge, whilst 2 Column under the command of Major Arthur Emmett along with Southern Group Headquarters led by Lt-Colonel Alexander, were to head on towards the rail station itself. What neither group realised was that the Japanese had by now closed in on the unsuspecting Chindits and lay in wait just a short way up the tracks.

To make matters worse the two Gurkha columns had also now lost radio contact with each other. 2 Column and Group Head Quarters, in the black of night stumbled into an enemy ambush which straddled both sides of the railway embankment. Here is how Lieutenant Ian MacHorton, a young subaltern with 2 Column remembered that moment:

We shuffled to a halt as the guides probed forward. There came the sound of just one bang up front, then an inferno of noise engulfed the world around me. There came the high-pitched staccato scream of a machine gun, then overwhelmingly many others joined in, the crash and ping of rifle bullets, the banging of grenades as the battle reached a fearful crescendo. Men and mules were lying, twisted and contorted, twitching and writhing, others were still erect, stark in the moonlight, heaving and jerking in the midst of this chaos. Then a sinister scuffling noise made by men of all kinds in close combat. The close combat of bayonet and kukri, the fanatical, personal slaughter with blood-dripping cold steel.

Colonel Alexander managed to extract the majority of his Head Quarters from the chaos and devastation at Kyaikthin and decided to lead them away to the agreed rendezvous point a few miles further east. Within a few days (about the 7th March) Group Head Quarters with the survivors from 2 Column had met up once more with George Dunlop and his men. Together they crossed the Irrawaddy River. Southern Group now found themselves the most easterly placed Chindit unit and by that nature the furthest from the safety of India. All remaining Chindit columns were now over the Irrawaddy and caught in an area of country contained on three sides by the Shweli and Irrawaddy Rivers, the force was trapped and slowly the Japanese began to close in.

After a further two weeks operating in this area and achieving little of value, 4 Corps in conjunction with Wingate decided to bring 77 Brigade home and the dispersal signal was given to all columns in late March. Alexander had a very clear vision in his mind at this point; to return Southern Group back to India in one piece and as one unit. However, after several days attempting to avoid contact with the Japanese on the Mongmit/Myitson Road, the Colonel reluctantly agreed to jettison the majority of his mules and all of the heavy arms and equipment. The men again met with disaster on April 6th when they arrived late at a supply drop location, only to see the planes heading back to India still fully laden. Alexander held an officers conference, where the decision was made to head north-east and attempt to reach the Allied held outpost of Fort Hertz.

By the 10th April, the group had reached the banks of the fast flowing Shweli River. Some other Chindit columns had managed to cross the river at various points roughly one week before, but the Gurkhas of Southern Group struggled, losing several men in two aborted attempts to reach the north bank. Amongst the casualties on April 10th was Vivian Stuart Weatherall, who had been the officer in charge of 1 Column before Major Dunlop's arrival at the Saugor Camp, he was very much loved by his Gurkha soldiers and his death was a massive blow to their morale.

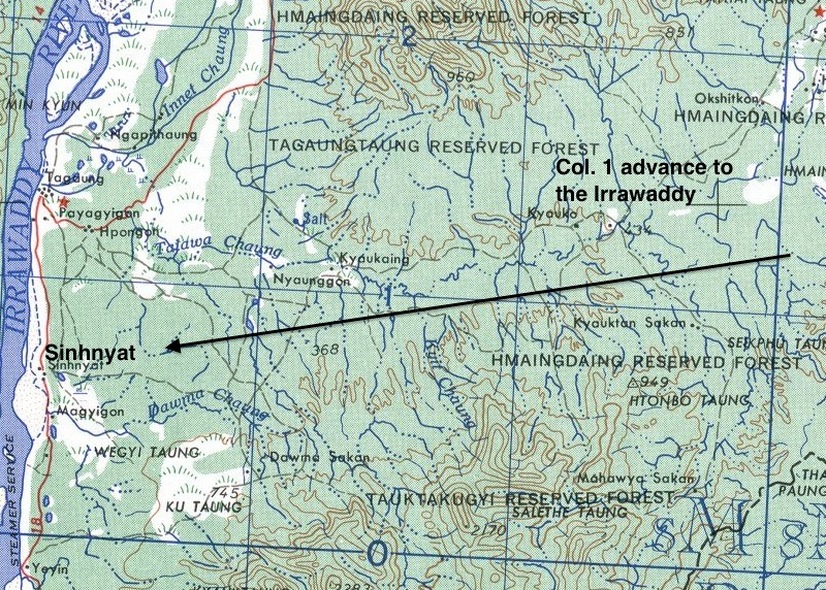

Failure to cross the Shweli cost the group their chance of reaching Fort Hertz and under some considerable pressure, Colonel Alexander reluctantly agreed to change course and head directly west for India. It was during this period that the party, now numbering some 480 men began to show signs of fatigue, this of course was mainly due to the lack of decent rations and availability of good drinking water, but general discipline had fallen away quite dramatically too. The young Gurkhas were constantly on edge, reacting to any jungle noise with undue alarm and expecting an ambush around every corner. On the 20th April, the men of 1 Column again faced the obstacle of the mile wide Irrawaddy River, this time near the village of Sinhnyat.

To make matters worse the two Gurkha columns had also now lost radio contact with each other. 2 Column and Group Head Quarters, in the black of night stumbled into an enemy ambush which straddled both sides of the railway embankment. Here is how Lieutenant Ian MacHorton, a young subaltern with 2 Column remembered that moment:

We shuffled to a halt as the guides probed forward. There came the sound of just one bang up front, then an inferno of noise engulfed the world around me. There came the high-pitched staccato scream of a machine gun, then overwhelmingly many others joined in, the crash and ping of rifle bullets, the banging of grenades as the battle reached a fearful crescendo. Men and mules were lying, twisted and contorted, twitching and writhing, others were still erect, stark in the moonlight, heaving and jerking in the midst of this chaos. Then a sinister scuffling noise made by men of all kinds in close combat. The close combat of bayonet and kukri, the fanatical, personal slaughter with blood-dripping cold steel.

Colonel Alexander managed to extract the majority of his Head Quarters from the chaos and devastation at Kyaikthin and decided to lead them away to the agreed rendezvous point a few miles further east. Within a few days (about the 7th March) Group Head Quarters with the survivors from 2 Column had met up once more with George Dunlop and his men. Together they crossed the Irrawaddy River. Southern Group now found themselves the most easterly placed Chindit unit and by that nature the furthest from the safety of India. All remaining Chindit columns were now over the Irrawaddy and caught in an area of country contained on three sides by the Shweli and Irrawaddy Rivers, the force was trapped and slowly the Japanese began to close in.

After a further two weeks operating in this area and achieving little of value, 4 Corps in conjunction with Wingate decided to bring 77 Brigade home and the dispersal signal was given to all columns in late March. Alexander had a very clear vision in his mind at this point; to return Southern Group back to India in one piece and as one unit. However, after several days attempting to avoid contact with the Japanese on the Mongmit/Myitson Road, the Colonel reluctantly agreed to jettison the majority of his mules and all of the heavy arms and equipment. The men again met with disaster on April 6th when they arrived late at a supply drop location, only to see the planes heading back to India still fully laden. Alexander held an officers conference, where the decision was made to head north-east and attempt to reach the Allied held outpost of Fort Hertz.

By the 10th April, the group had reached the banks of the fast flowing Shweli River. Some other Chindit columns had managed to cross the river at various points roughly one week before, but the Gurkhas of Southern Group struggled, losing several men in two aborted attempts to reach the north bank. Amongst the casualties on April 10th was Vivian Stuart Weatherall, who had been the officer in charge of 1 Column before Major Dunlop's arrival at the Saugor Camp, he was very much loved by his Gurkha soldiers and his death was a massive blow to their morale.

Failure to cross the Shweli cost the group their chance of reaching Fort Hertz and under some considerable pressure, Colonel Alexander reluctantly agreed to change course and head directly west for India. It was during this period that the party, now numbering some 480 men began to show signs of fatigue, this of course was mainly due to the lack of decent rations and availability of good drinking water, but general discipline had fallen away quite dramatically too. The young Gurkhas were constantly on edge, reacting to any jungle noise with undue alarm and expecting an ambush around every corner. On the 20th April, the men of 1 Column again faced the obstacle of the mile wide Irrawaddy River, this time near the village of Sinhnyat.

After some consultation with the Headman of Sinhnyat, Major Dunlop procured some small country boats and sent a scouting patrol across the river under the command of Lieutenant Wormald. Shown below are a number of first-hand accounts describing what happened next, firstly from the book Wingate's Lost Brigade:

At Sinhnyat the villagers produced some food for the ravenous men, but they were so desperate that proper distribution broke down. When the chaos subsided Dunlop managed to lay in some stocks for the next stage of the journey. Lieutenant Chet Kin of the Burma Rifles located two native boats that could carry about thirty men between them. A patrol under Lieutenant Wormald was sent across in the smaller boat and half an hour passed while they scouted the far bank.

Suddenly firing broke out and for five minutes they could hear the sound of enemy weapons before silence descended. Later the boat returned, empty except for the native boatman. At dusk on 20th April, they tried again and all night long the boats plied back and forth. During the evening Subedar Padanbahadur Rai with fifty-nine men joined the queue on the riverbank. Previously attached to Wingate's Headquarters as Defence Platoon, they had been left behind when the Brigadier recrossed the river further to the north near the town of Inywa.

The crossing continued throughout the night and as the men reached the west bank they quickly took cover and moved on in their dispersal groups. As dawn broke, the covering platoon under Naik Devsur Ale began to cross. As the last men began to climb into the two boats who should appear but Ian MacHorton (2 Column), who had been left behind at Mongmit. He had avoided capture by the Japanese and, limping badly, had set off towards the west. He had been assisted on the way by friendly natives who fed him and tended his wound. Doc Lusk, the Irish Medical Officer from 2 Column, slapped him on the back and propelled him towards the waiting boats. There were eleven men in the leaky craft already, but they made room for him and then pushed off. Doc Lusk and the rest of the rearguard followed 30 yards astern.

The first boat was a hundred yards from the safety of the far bank when the Japanese arrived. Running along the west bank, they opened fire on the boats —some of the men in MacHorton's boat were hit and collapsed against their comrades. Then the boat capsized, the water swirling around the desperate men. MacHorton clung to the upturned boat as it floated downstream and struggled ashore. He could hear the sound of British and Japanese weapons in the distance, and saw that Doc Lusk's boat had turned around and was making its way back to the relative safety of the far shore. The occupants of the boat, including Second Lieutenant Harvey, Redman of the RAF and Doc Lusk were later captured by the Japanese. The genial Irishman would die in captivity.

Lt. Ian MacHorton ably and graphically described the same moment in his own book, Safer Than a Known Way. The account below begins with the approach of his boat to the western bank of the Irrawaddy:

A Jap machine-gun fired at us so close that it seemed almost on top of me. The water all around frothed as the bullets poured in. Some ploughed down into the depths leaving streams of bubbles, and others ricocheted to whine away across the river. Of all this I was vividly conscious in a moment of fear timeless and terrible in its detail. In their sudden attack men became frantic animals. A young British soldier was slumped limply over the side, his long hair floating on the water. Blood gushed from his mouth.

Another man, up forward, his body riddled with bullets, had been hurled backwards by the force of their impact and had collapsed on to his comrades. Blood was spurting from his wounds. Then the boat capsized. The water was suddenly full of desperate men. Frantically I clung on to the upturned hulk, into which bullets were thudding within inches of my head. Providentially the boat began to swing round, so that I was completely shielded from the enemy guns by its bulk. The safest thing to do was to stay where I was.

The boat was drifting downstream, and I noticed the current was steadily taking it in towards the shore. I held on with all the strength I had, seeking to fight against the swift stream. The weight of my water-logged boots was becoming greater. They threatened to drag me under. Then bullets ceased to whip and whine around me. I was invisible from the west bank, and no doubt by now the Japs believed all in the river to have been killed.

A confused battle was raging along the shore within the screen of the jungle. Bren and tommy-guns were barking their answers to the screaming of the Japanese automatics. I saw three men crawl out from the undergrowth on to a mudbank farther upstream to help drag survivors from our boat into the cover of the darkening jungle. The mudbank itself was stained red, but not with the blood of the men. The redness came from the last rays of the setting sun. The men still on the mudbank seemed to be immune from the Japanese fire, which was directed at them. Somehow all struggled clear and clambered up to merge with the black shadows of the jungle.

Doc Lusk's boat I now saw, turning my head as I drifted on, it had been little more than half-way across when the shooting started. They had obviously turned round straight away and were now well on the way back to the east bank. They, at least, would get out of this safely, I told myself. I was not to know that I should never see gallant Doc Lusk again. He was to die as a prisoner of the Japs.

The final narrative in recollection of the opposed crossing at the Irrawaddy River, comes from Major Dunlop. In his debrief report, written on his return to India he recalled:

At dusk on what must have been the 20th April, we crossed the river. All night boats plied back and forth, until by dawn only one flight of about twenty men remained. Just as the second boat of this last flight was coming in to shore the Japanese, up the river on our side opened up with machine guns and mortars and the boat was sunk. A general stamped followed with the officers running hither and thither, trying to stop the men.

It took about an hour to sort this lot out and when we had done, I found that around one hundred men were missing. Most of these, as it turned out, were collected together by the Subedar-Major (Siblal Thapa) who led them back to India. Our losses on the crossing had been those in the sunken boat and the rear party under Lt. George Harvey. This young officer had rather gallantly volunteered to for the job. Redman of the RAF and the Irish Doctor of No. 2 Column (George Lusk) had also stayed behind, the former to arrange the Dakota landings and the latter to look after the sick. When we did get back I asked General Scoones of 4 Corps, to have planes sent to the location. This was done, but constant searching revealed nothing.

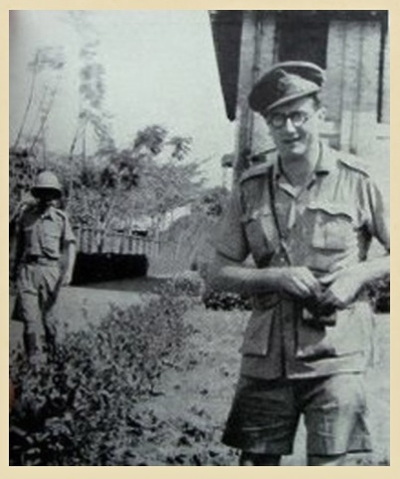

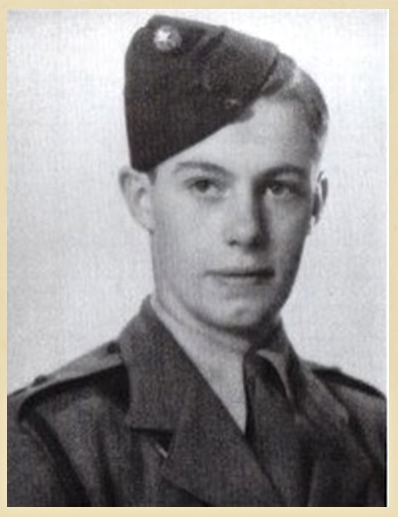

Seen below is a gallery of photographs showing some of the men mentioned in the story so far. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

At Sinhnyat the villagers produced some food for the ravenous men, but they were so desperate that proper distribution broke down. When the chaos subsided Dunlop managed to lay in some stocks for the next stage of the journey. Lieutenant Chet Kin of the Burma Rifles located two native boats that could carry about thirty men between them. A patrol under Lieutenant Wormald was sent across in the smaller boat and half an hour passed while they scouted the far bank.

Suddenly firing broke out and for five minutes they could hear the sound of enemy weapons before silence descended. Later the boat returned, empty except for the native boatman. At dusk on 20th April, they tried again and all night long the boats plied back and forth. During the evening Subedar Padanbahadur Rai with fifty-nine men joined the queue on the riverbank. Previously attached to Wingate's Headquarters as Defence Platoon, they had been left behind when the Brigadier recrossed the river further to the north near the town of Inywa.

The crossing continued throughout the night and as the men reached the west bank they quickly took cover and moved on in their dispersal groups. As dawn broke, the covering platoon under Naik Devsur Ale began to cross. As the last men began to climb into the two boats who should appear but Ian MacHorton (2 Column), who had been left behind at Mongmit. He had avoided capture by the Japanese and, limping badly, had set off towards the west. He had been assisted on the way by friendly natives who fed him and tended his wound. Doc Lusk, the Irish Medical Officer from 2 Column, slapped him on the back and propelled him towards the waiting boats. There were eleven men in the leaky craft already, but they made room for him and then pushed off. Doc Lusk and the rest of the rearguard followed 30 yards astern.

The first boat was a hundred yards from the safety of the far bank when the Japanese arrived. Running along the west bank, they opened fire on the boats —some of the men in MacHorton's boat were hit and collapsed against their comrades. Then the boat capsized, the water swirling around the desperate men. MacHorton clung to the upturned boat as it floated downstream and struggled ashore. He could hear the sound of British and Japanese weapons in the distance, and saw that Doc Lusk's boat had turned around and was making its way back to the relative safety of the far shore. The occupants of the boat, including Second Lieutenant Harvey, Redman of the RAF and Doc Lusk were later captured by the Japanese. The genial Irishman would die in captivity.

Lt. Ian MacHorton ably and graphically described the same moment in his own book, Safer Than a Known Way. The account below begins with the approach of his boat to the western bank of the Irrawaddy:

A Jap machine-gun fired at us so close that it seemed almost on top of me. The water all around frothed as the bullets poured in. Some ploughed down into the depths leaving streams of bubbles, and others ricocheted to whine away across the river. Of all this I was vividly conscious in a moment of fear timeless and terrible in its detail. In their sudden attack men became frantic animals. A young British soldier was slumped limply over the side, his long hair floating on the water. Blood gushed from his mouth.

Another man, up forward, his body riddled with bullets, had been hurled backwards by the force of their impact and had collapsed on to his comrades. Blood was spurting from his wounds. Then the boat capsized. The water was suddenly full of desperate men. Frantically I clung on to the upturned hulk, into which bullets were thudding within inches of my head. Providentially the boat began to swing round, so that I was completely shielded from the enemy guns by its bulk. The safest thing to do was to stay where I was.

The boat was drifting downstream, and I noticed the current was steadily taking it in towards the shore. I held on with all the strength I had, seeking to fight against the swift stream. The weight of my water-logged boots was becoming greater. They threatened to drag me under. Then bullets ceased to whip and whine around me. I was invisible from the west bank, and no doubt by now the Japs believed all in the river to have been killed.

A confused battle was raging along the shore within the screen of the jungle. Bren and tommy-guns were barking their answers to the screaming of the Japanese automatics. I saw three men crawl out from the undergrowth on to a mudbank farther upstream to help drag survivors from our boat into the cover of the darkening jungle. The mudbank itself was stained red, but not with the blood of the men. The redness came from the last rays of the setting sun. The men still on the mudbank seemed to be immune from the Japanese fire, which was directed at them. Somehow all struggled clear and clambered up to merge with the black shadows of the jungle.

Doc Lusk's boat I now saw, turning my head as I drifted on, it had been little more than half-way across when the shooting started. They had obviously turned round straight away and were now well on the way back to the east bank. They, at least, would get out of this safely, I told myself. I was not to know that I should never see gallant Doc Lusk again. He was to die as a prisoner of the Japs.

The final narrative in recollection of the opposed crossing at the Irrawaddy River, comes from Major Dunlop. In his debrief report, written on his return to India he recalled:

At dusk on what must have been the 20th April, we crossed the river. All night boats plied back and forth, until by dawn only one flight of about twenty men remained. Just as the second boat of this last flight was coming in to shore the Japanese, up the river on our side opened up with machine guns and mortars and the boat was sunk. A general stamped followed with the officers running hither and thither, trying to stop the men.

It took about an hour to sort this lot out and when we had done, I found that around one hundred men were missing. Most of these, as it turned out, were collected together by the Subedar-Major (Siblal Thapa) who led them back to India. Our losses on the crossing had been those in the sunken boat and the rear party under Lt. George Harvey. This young officer had rather gallantly volunteered to for the job. Redman of the RAF and the Irish Doctor of No. 2 Column (George Lusk) had also stayed behind, the former to arrange the Dakota landings and the latter to look after the sick. When we did get back I asked General Scoones of 4 Corps, to have planes sent to the location. This was done, but constant searching revealed nothing.

Seen below is a gallery of photographs showing some of the men mentioned in the story so far. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

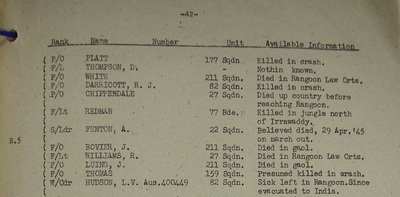

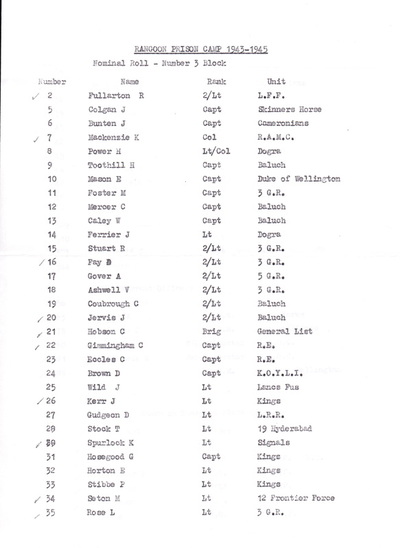

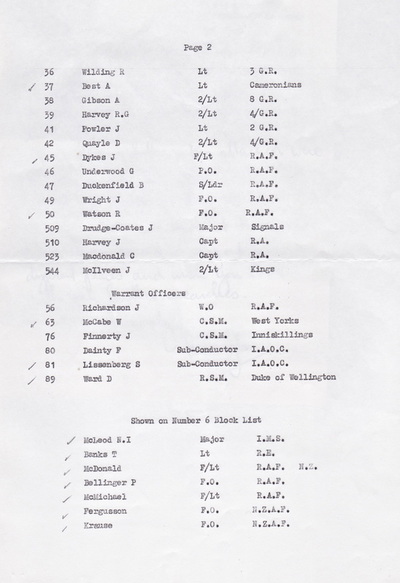

From the witness statements given, it seems likely that last group of Chindits, acting as rearguard at the Irrawaddy also came under enemy fire. It is possible that after returning to the eastern banks of the river, Lt. Harvey's group were ambushed by a Japanese patrol that had caught up with events at Sinhnyat. It also seems likely that most, if not all of the men involved were wounded or killed during this surprise attack. John Redman was killed at or very near the village of Sinhnyat on the 20th April 1943. In the RAF Investigatory Report AIR38/80, a document concerning the fate of personnel know to have fallen into enemy hands during the Burma Campaign and especially those who were eventually held at Rangoon Jail, there is a simple one line entry in relation to John Redman on page 42:

F/Lt. Redman, 77th Brigade-Killed in the jungle north of the Irrawaddy.

In March 2008, I was extremely fortunate to meet Denis Gudgeon, a veteran of the first Chindit expedition and a survivor of two years imprisonment at the hands of the Japanese inside Rangoon Jail. Denis was a Gurkha Officer and a member of Chindit Column 3 under the command of Major Mike Calvert. He told me that during his time in Rangoon Jail he had shared a cell in Block 3 with, amongst others, Lt. Harvey of 1 Column.

Harvey told Denis that he was the only British survivor from the enemy ambush at Sinhnyat and that both John Redman and Doc Lusk had been wounded in the original skirmish and had been 'dealt with' by the Japanese when it became obvious that they could not continue to march unaided. Harvey recalled that Redman had barely lasted 24 hours and that George Lusk had died a few days later as the party marched north-east. This anecdotal account of the fate that befell John Redman, recounted some 65 years after the actual event, is probably as close as we are ever likely to get, in knowing the full truth of what happened to the young Flight-Lieutenant in April 1943. John was certainly not the only Chindit to suffer such a brutal and murderous demise at the hands of the Japanese that year.

No grave or remains were ever found after the war, and for this reason John Redman is remembered upon the Singapore Memorial at Kranji War Cemetery. The Singapore Memorial bears the names of over 24,000 casualties of the Commonwealth Forces who have no known grave. Many of these have no known date of death and so are accorded the date or period from when they were known to be missing or captured. The land forces commemorated by the memorial died during the campaigns in Malaya and Indonesia or in subsequent captivity, many of them during the construction of the Burma-Thailand railway, or at sea while being transported into imprisonment elsewhere. The memorial also commemorates airmen who died during operations over the whole of southern and eastern Asia and the surrounding seas and oceans.

Two other soldiers serving with 1 Column on Operation Longcloth; Jemadar Gyanbir Thapa and Rifleman Mangalbahadur Gurung also died at the Irrawaddy on the 20th April 1943. It is not known whether these men were on the eastern or western banks when they were killed.

Shown below is the final gallery of images in relation to this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

F/Lt. Redman, 77th Brigade-Killed in the jungle north of the Irrawaddy.

In March 2008, I was extremely fortunate to meet Denis Gudgeon, a veteran of the first Chindit expedition and a survivor of two years imprisonment at the hands of the Japanese inside Rangoon Jail. Denis was a Gurkha Officer and a member of Chindit Column 3 under the command of Major Mike Calvert. He told me that during his time in Rangoon Jail he had shared a cell in Block 3 with, amongst others, Lt. Harvey of 1 Column.

Harvey told Denis that he was the only British survivor from the enemy ambush at Sinhnyat and that both John Redman and Doc Lusk had been wounded in the original skirmish and had been 'dealt with' by the Japanese when it became obvious that they could not continue to march unaided. Harvey recalled that Redman had barely lasted 24 hours and that George Lusk had died a few days later as the party marched north-east. This anecdotal account of the fate that befell John Redman, recounted some 65 years after the actual event, is probably as close as we are ever likely to get, in knowing the full truth of what happened to the young Flight-Lieutenant in April 1943. John was certainly not the only Chindit to suffer such a brutal and murderous demise at the hands of the Japanese that year.

No grave or remains were ever found after the war, and for this reason John Redman is remembered upon the Singapore Memorial at Kranji War Cemetery. The Singapore Memorial bears the names of over 24,000 casualties of the Commonwealth Forces who have no known grave. Many of these have no known date of death and so are accorded the date or period from when they were known to be missing or captured. The land forces commemorated by the memorial died during the campaigns in Malaya and Indonesia or in subsequent captivity, many of them during the construction of the Burma-Thailand railway, or at sea while being transported into imprisonment elsewhere. The memorial also commemorates airmen who died during operations over the whole of southern and eastern Asia and the surrounding seas and oceans.

Two other soldiers serving with 1 Column on Operation Longcloth; Jemadar Gyanbir Thapa and Rifleman Mangalbahadur Gurung also died at the Irrawaddy on the 20th April 1943. It is not known whether these men were on the eastern or western banks when they were killed.

Shown below is the final gallery of images in relation to this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank the gentlemen of the RAF Commands Forum for their assistance, albeit unbeknown, in bringing this story to these website pages. My thanks go once again to Edward McManus for allowing me to use the photographs and information about John Redman on the Battle of Britain London Monument website. Special appreciation must go to John's nephew, Robert Hunter, who I have so far struggled to contact, for his valuable contribution to the above narrative.

Finally, I would like to dedicate this story to all the RAF Air Liaison personnel from both Chindit expeditions, who in 1943 and 1944 were persuaded to give up their wings and trust in their feet.

Finally, I would like to dedicate this story to all the RAF Air Liaison personnel from both Chindit expeditions, who in 1943 and 1944 were persuaded to give up their wings and trust in their feet.

Update 0/03/2023.

In February this year (2023), I was delighted to receive the following email contact from Vincent Wratten:

Hi Steve,

My late father was AC2 Albert Thomas Wratten, service number CE 924484. He joined the Merchant Ship Fighter Unit (MSFU) as a catapult operative on the 13th June 1941 and was aboard the Empire Hudson on the 25th July the same year. I therefore presume he was part of John Redman's crew. The Empire Hudson left Sydney, Nova Scotia as part of convoy SC42 on the 30th August 1941. Early on the morning of the 10th September at 4 minutes past 0500 hours, the ship was hit by torpedoes fired from the German submarine U-82 off the coast of Greenland. My father was asleep at the time and was woken up to be told they were sinking. As you might imagine, there was a bit of a panic and they were told to leave the ship at once, but in the lifeboat it could be seen that the ship was still afloat. My father wanted to go back to collect some items, but was not allowed to return to the ship.

The survivors (4 seamen were sadly killed in the engine room) were in the lifeboats for four hours before being picked up. Naval records show my father was landed at Aultbea in Scotland on the 18th September and was then sent on to DEMS (Defensively Equipped Merchant Ships) at Glasgow. He later served again with the MSFU, the 60 OTU and then the 124 RSU (Repair & Salvage) in Burma.

Dad never really talked much about the war, but did mention the sinking so it must have made a fair impression on him. I have checked with various sources available to verify the above information as being accurate.

I'd like to thank Vincent for the above information, which gives some valuable details about the sinking of the Empire Hudson in August 1941, an incident that almost certainly deflected John Redman's wartime pathway and resulted in his joining 77 Brigade in Burma.

In February this year (2023), I was delighted to receive the following email contact from Vincent Wratten:

Hi Steve,

My late father was AC2 Albert Thomas Wratten, service number CE 924484. He joined the Merchant Ship Fighter Unit (MSFU) as a catapult operative on the 13th June 1941 and was aboard the Empire Hudson on the 25th July the same year. I therefore presume he was part of John Redman's crew. The Empire Hudson left Sydney, Nova Scotia as part of convoy SC42 on the 30th August 1941. Early on the morning of the 10th September at 4 minutes past 0500 hours, the ship was hit by torpedoes fired from the German submarine U-82 off the coast of Greenland. My father was asleep at the time and was woken up to be told they were sinking. As you might imagine, there was a bit of a panic and they were told to leave the ship at once, but in the lifeboat it could be seen that the ship was still afloat. My father wanted to go back to collect some items, but was not allowed to return to the ship.

The survivors (4 seamen were sadly killed in the engine room) were in the lifeboats for four hours before being picked up. Naval records show my father was landed at Aultbea in Scotland on the 18th September and was then sent on to DEMS (Defensively Equipped Merchant Ships) at Glasgow. He later served again with the MSFU, the 60 OTU and then the 124 RSU (Repair & Salvage) in Burma.

Dad never really talked much about the war, but did mention the sinking so it must have made a fair impression on him. I have checked with various sources available to verify the above information as being accurate.

I'd like to thank Vincent for the above information, which gives some valuable details about the sinking of the Empire Hudson in August 1941, an incident that almost certainly deflected John Redman's wartime pathway and resulted in his joining 77 Brigade in Burma.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, September 2016.