Japanese Medical Experimentation on Chindit POW's

Every now and again during my research into the men of Operation Longcloth I have inadvertently stumbled across information which for one reason or another is difficult and unpalatable to accept as being true. The rumour and conjecture surrounding Japanese experimentation on some of the POW's from Longcloth is one such example. From the evidence (some of it first hand) shown below, there seems to be little doubt that medical experiments, mostly in the testing of malarial strains and bacterium were taken out on the already exhausted and weakened Chindit men.

It seems that at least one group of prisoners were used as guinea-pigs by Japanese Medical Officers at a POW Camp in the town of Kalaw. These experiments took place not long after the unfortunate men had been taken prisoner and well before they had the chance of reaching any camp where their own medical officers might be present. There were also rumours that similar experiments were performed at the Maymyo Concentration Camp.

Many times over the last 6 or 7 years I have wondered about the fate of my own grandfather and his comrades, and uncovering atrocities such as these can only leave you feeling uncertain and anxious about what might of really happened to these men.

Firstly, here is a large quote taken from the book 'Return via Rangoon', by Philip Stibbe. He describes what he knew of the possible experimentations and one incident that was possibly directly related to them.

"One incident in our first few months at Rangoon was particularly tragic. The Japanese Medical Officer at Maymyo had been using some of our men as human guinea pigs, injecting germs into them to see the results. One party of prisoners arrived from Maymyo in a terrible state. They told us that they had been injected with malaria germs, nearly all of them died soon after arrival. One of them went delirious and the following day he went missing at morning roll-call.

We managed to conceal his absence from the Japs, but, when a thorough search of the compound failed to reveal any trace of him, we thought it was obviously better to tell the Japs that he had gone rather than let them discover it for themselves. Somehow in his delirium, the man had got out of the compound and out of the jail. Nobody ever found out how he did this. For a white man to try to escape from Rangoon was sheer madness. The Burmans in that area were mostly so frightened of the Japs that, even if they did not betray him, they would certainly not assist him; besides, the nearest Allied territory was thousands of miles away.

As soon as the Japs were told that the man was missing they took drastic action. Our senior officer, a New Zealand Flight Lieutenant, was sick at that time, but the acting senior officer and various men who the Japs quite wrongly suspected of assisting the escape were clapped into solitary confinement. The rest of us were locked in our rooms and spent the time wondering what was going to happen. On the evening of the second day the cooks were allowed to prepare a meal for us; the following morning we were paraded in the compound in front of the Japanese Commandant.

The escaped man was brought in; the poor fellow had obviously no idea what was happening. The Commandant announced that he had been brought back to the jail by Burmans and that he would receive the severest punishment. He was then led out and none of us ever saw him again. As for the rest of us, the Commandant said that he would be lenient and that we would carry on as usual provided that we promised not to try to escape. We were all required to sign a document to this effect and, after some discussion amongst ourselves, we did so. We felt that, after all, a promise extracted by force by one's enemies is not binding and the chance of a good opportunity of escape presenting itself seemed very remote.

After a few days, those who had been sent to solitary confinement came back, considerably shaken by their ordeal. The Japanese guard commander who had failed to notice that there was a man missing at morning roll call was severely punished and he, in his turn, retaliated on the British officer who had been in charge that day. The officer came back from the cells with terrible bruises on his face where he had been beaten up. He was never the same after this incident and, many months afterwards, he died of heart trouble. During the days when we had been locked up, the sick POW's received no medical attention and this probably hastened the end in many cases."

It seems that at least one group of prisoners were used as guinea-pigs by Japanese Medical Officers at a POW Camp in the town of Kalaw. These experiments took place not long after the unfortunate men had been taken prisoner and well before they had the chance of reaching any camp where their own medical officers might be present. There were also rumours that similar experiments were performed at the Maymyo Concentration Camp.

Many times over the last 6 or 7 years I have wondered about the fate of my own grandfather and his comrades, and uncovering atrocities such as these can only leave you feeling uncertain and anxious about what might of really happened to these men.

Firstly, here is a large quote taken from the book 'Return via Rangoon', by Philip Stibbe. He describes what he knew of the possible experimentations and one incident that was possibly directly related to them.

"One incident in our first few months at Rangoon was particularly tragic. The Japanese Medical Officer at Maymyo had been using some of our men as human guinea pigs, injecting germs into them to see the results. One party of prisoners arrived from Maymyo in a terrible state. They told us that they had been injected with malaria germs, nearly all of them died soon after arrival. One of them went delirious and the following day he went missing at morning roll-call.

We managed to conceal his absence from the Japs, but, when a thorough search of the compound failed to reveal any trace of him, we thought it was obviously better to tell the Japs that he had gone rather than let them discover it for themselves. Somehow in his delirium, the man had got out of the compound and out of the jail. Nobody ever found out how he did this. For a white man to try to escape from Rangoon was sheer madness. The Burmans in that area were mostly so frightened of the Japs that, even if they did not betray him, they would certainly not assist him; besides, the nearest Allied territory was thousands of miles away.

As soon as the Japs were told that the man was missing they took drastic action. Our senior officer, a New Zealand Flight Lieutenant, was sick at that time, but the acting senior officer and various men who the Japs quite wrongly suspected of assisting the escape were clapped into solitary confinement. The rest of us were locked in our rooms and spent the time wondering what was going to happen. On the evening of the second day the cooks were allowed to prepare a meal for us; the following morning we were paraded in the compound in front of the Japanese Commandant.

The escaped man was brought in; the poor fellow had obviously no idea what was happening. The Commandant announced that he had been brought back to the jail by Burmans and that he would receive the severest punishment. He was then led out and none of us ever saw him again. As for the rest of us, the Commandant said that he would be lenient and that we would carry on as usual provided that we promised not to try to escape. We were all required to sign a document to this effect and, after some discussion amongst ourselves, we did so. We felt that, after all, a promise extracted by force by one's enemies is not binding and the chance of a good opportunity of escape presenting itself seemed very remote.

After a few days, those who had been sent to solitary confinement came back, considerably shaken by their ordeal. The Japanese guard commander who had failed to notice that there was a man missing at morning roll call was severely punished and he, in his turn, retaliated on the British officer who had been in charge that day. The officer came back from the cells with terrible bruises on his face where he had been beaten up. He was never the same after this incident and, many months afterwards, he died of heart trouble. During the days when we had been locked up, the sick POW's received no medical attention and this probably hastened the end in many cases."

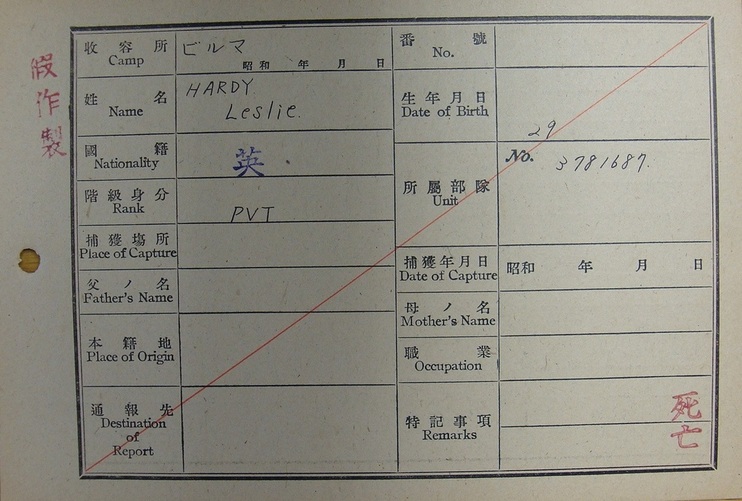

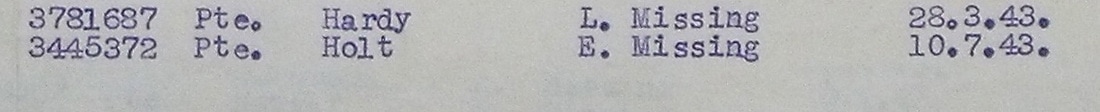

The man referred to in Lieutenant Stibbe's account was Pte. Leslie Hardy. I have been told this information from a first-hand witness to the incident, although it was agreed by the men at the time, never to relay such disturbing information back to any of the POW casualties families. The index card for Hardy (shown above) is scant in detail, both on the front and the reverse of the card. In fact, translated from the reverse the document suggests that the soldier died from 'heart failure'. This cause of death I am sure is the continuation of the promise made by the men not to unduly upset any next of kin that may be searching for information about their loved one and his death.

These types of index card I call 'Maymyo' cards. This is purely my own label for a group of cards numbering so far in my research about 30. There may well be others in the final few boxes I still need to check through at the National Archives. I use the 'Maymyo' term because these cards always belong to men who perish very soon after arriving at Rangoon Jail, typically in the months of May, June and July 1943. These men tend to belong to a party of Chindits who were the last to leave the Maymyo Concentration Camp. The information on the card is limited, both front and rear, my belief is that these cards were only collated many weeks after the soldier had perished and the information was simply what the officers present in Rangoon could recall about them at that time. The proper collation of Japanese index cards for the men of Rangoon Jail actually began in March 1944, so you can see that a period of several months had elapsed before any serious attempt to record Chindit POW details was undertaken.

As mentioned earlier, my main concern is that this final group of men to leave Maymyo could well be the men who had been used by the Japanese as guinea-pigs, or at least those who were still alive by then. I sincerely hope this is not the case as my own grandfather also has a 'Maymyo' type index card to his name.

The next piece of evidence is a letter written on March 11th 1946, by a soldier called Gerald Desmond. Pte. Desmond, from Dublin, and a member of Column 5 on Operation Longcloth was contacted by the Army Investigations Bureau after the war, in the hope that he might have valuable information about several of the Chindit casualties from 1943. Desmond was one of the very few Chindit Other Ranks to survive his time as a prisoner of war after spending nearly two years in Rangoon Jail.

Here is his response in the form of a short letter to the War Office, where he names those men who he recalls as dying at a POW Camp in the town of Kalaw.

"In answer to your letter regarding missing personnel, I can give information about the following:

Pte. Knight of the North Staffordshire Regiment before being transferred to 142 Company 13th Kings in July 1942.

I met him whilst a prisoner in a place called Kalaw, he died after being there for about two weeks, the cause of his death I could not say for sure. However, the Japanese had been experimenting on us all the time and I saw them give him about six needles and the next morning he was dead, he was called 'Rocky' Knight to his friends.

Pte. Maley. There was another lad called Maley who I believe came from Manchester and had been transferred from the Loyal Regiment in 1942. He was married I think too. Maley was also with 142 Company, the Japs gave him an injection in the arm, he died very shortly afterwards.

Sapper Low. He had transferred from the Royal Engineers into the 142 Company of the 13th Kings, he was from Dagenham in London. He also died whilst at Kalaw with the Japs. That is all I know, sorry I cannot give you any more details about these men.

Yours faithfully-G. Desmond."

The men referred to by Desmond were:

Pte. Peter Edwin Knight, or 'Rocky' to his mates.

Pte. Robert Maley

Sapper Percy Ronald Lowe

There is a suggestion that another man, Pte. Sidney Hunt was also part of this group on capture. Pte. Hunt died a little later on in Rangoon Jail.

On the 21st August 1946 Pte. Desmond signed a sworn affidavit further explaining the events from his time at the POW Camp at Kalaw and describing what actually happened to 'Rocky' Knight, Robert Maley and Percy Lowe.

The final piece of evidence that supports the claim of Japanese experimentation comes in the form of a hand-written diary scribbled on the back of a postcard by Flight Lieutenant John Kingsley Edmonds. Edmonds had been captured in late April 1943 along with his RAF Sergeant Kenneth Wyse, they had both made the tortuous journey through many of the Chindit POW Camps that year, before both finally ending up incarcerated at Rangoon. However, Wyse and Edmonds had been separated whilst at Maymyo and the Sergeant made the journey down to Rangoon a few weeks later than Edmonds.

Here is a transcription of one section of Edmonds diary:

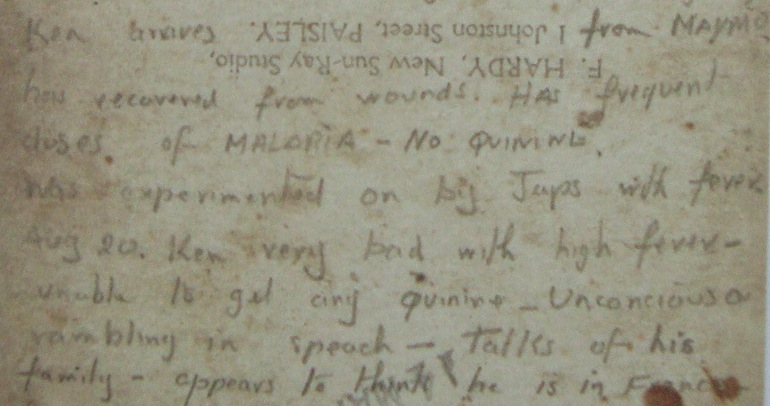

"Ken arrives from Maymyo, has recovered from wounds. Has frequent doses of malaria-no quinine. Was experimented on by Japs with fever.

(I think he means that Wyse was injected with malarial fever strains).

Aug. 20th (1943). Ken very bad with high fever-unable to get any quinine. Unconscious and rambling in speech. Talks of his family-appears to think he is in France."

Seen below is the section of Edmonds diary, as transcribed above.

In conclusion, when I sit down and think about the men from Operation Longcloth and their fate in 1943, I often wonder what would be the soldiers choice in regards to his own death. Killed instantly by a single bullet would be my guess here, but how many of them would have ever considered that they might end up being a guinea-pig at the wrong end of a Japanese doctor's syringe.

These types of index card I call 'Maymyo' cards. This is purely my own label for a group of cards numbering so far in my research about 30. There may well be others in the final few boxes I still need to check through at the National Archives. I use the 'Maymyo' term because these cards always belong to men who perish very soon after arriving at Rangoon Jail, typically in the months of May, June and July 1943. These men tend to belong to a party of Chindits who were the last to leave the Maymyo Concentration Camp. The information on the card is limited, both front and rear, my belief is that these cards were only collated many weeks after the soldier had perished and the information was simply what the officers present in Rangoon could recall about them at that time. The proper collation of Japanese index cards for the men of Rangoon Jail actually began in March 1944, so you can see that a period of several months had elapsed before any serious attempt to record Chindit POW details was undertaken.

As mentioned earlier, my main concern is that this final group of men to leave Maymyo could well be the men who had been used by the Japanese as guinea-pigs, or at least those who were still alive by then. I sincerely hope this is not the case as my own grandfather also has a 'Maymyo' type index card to his name.

The next piece of evidence is a letter written on March 11th 1946, by a soldier called Gerald Desmond. Pte. Desmond, from Dublin, and a member of Column 5 on Operation Longcloth was contacted by the Army Investigations Bureau after the war, in the hope that he might have valuable information about several of the Chindit casualties from 1943. Desmond was one of the very few Chindit Other Ranks to survive his time as a prisoner of war after spending nearly two years in Rangoon Jail.

Here is his response in the form of a short letter to the War Office, where he names those men who he recalls as dying at a POW Camp in the town of Kalaw.

"In answer to your letter regarding missing personnel, I can give information about the following:

Pte. Knight of the North Staffordshire Regiment before being transferred to 142 Company 13th Kings in July 1942.

I met him whilst a prisoner in a place called Kalaw, he died after being there for about two weeks, the cause of his death I could not say for sure. However, the Japanese had been experimenting on us all the time and I saw them give him about six needles and the next morning he was dead, he was called 'Rocky' Knight to his friends.

Pte. Maley. There was another lad called Maley who I believe came from Manchester and had been transferred from the Loyal Regiment in 1942. He was married I think too. Maley was also with 142 Company, the Japs gave him an injection in the arm, he died very shortly afterwards.

Sapper Low. He had transferred from the Royal Engineers into the 142 Company of the 13th Kings, he was from Dagenham in London. He also died whilst at Kalaw with the Japs. That is all I know, sorry I cannot give you any more details about these men.

Yours faithfully-G. Desmond."

The men referred to by Desmond were:

Pte. Peter Edwin Knight, or 'Rocky' to his mates.

Pte. Robert Maley

Sapper Percy Ronald Lowe

There is a suggestion that another man, Pte. Sidney Hunt was also part of this group on capture. Pte. Hunt died a little later on in Rangoon Jail.

On the 21st August 1946 Pte. Desmond signed a sworn affidavit further explaining the events from his time at the POW Camp at Kalaw and describing what actually happened to 'Rocky' Knight, Robert Maley and Percy Lowe.

The final piece of evidence that supports the claim of Japanese experimentation comes in the form of a hand-written diary scribbled on the back of a postcard by Flight Lieutenant John Kingsley Edmonds. Edmonds had been captured in late April 1943 along with his RAF Sergeant Kenneth Wyse, they had both made the tortuous journey through many of the Chindit POW Camps that year, before both finally ending up incarcerated at Rangoon. However, Wyse and Edmonds had been separated whilst at Maymyo and the Sergeant made the journey down to Rangoon a few weeks later than Edmonds.

Here is a transcription of one section of Edmonds diary:

"Ken arrives from Maymyo, has recovered from wounds. Has frequent doses of malaria-no quinine. Was experimented on by Japs with fever.

(I think he means that Wyse was injected with malarial fever strains).

Aug. 20th (1943). Ken very bad with high fever-unable to get any quinine. Unconscious and rambling in speech. Talks of his family-appears to think he is in France."

Seen below is the section of Edmonds diary, as transcribed above.

In conclusion, when I sit down and think about the men from Operation Longcloth and their fate in 1943, I often wonder what would be the soldiers choice in regards to his own death. Killed instantly by a single bullet would be my guess here, but how many of them would have ever considered that they might end up being a guinea-pig at the wrong end of a Japanese doctor's syringe.

Update 06/02/2013.

From the IWM sound recording made by Pte. Fred Holloman, here is a paraphrased quotation telling the story of Leslie Hardy, who Holloman refers to as Corporal. To listen to Fred Holloman's interview, please click on the link here:

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80015837

The story about Corporal Hardy can be found on Reel 3 of the audio recording.

"Then the next day a chap named Corporal Hardy well, he must have had fever of the brain, because he walked out of the main gates.

Suddenly it was Tenko (roll-call) and the officers in charge are rushing around asking where Hardy was, we were looking all over the place, but could not find him anywhere. The officer in charge said he must be in the camp somewhere, as he would be a raving lunatic to try and escape.

The officer decided to put Hardy's name down as being in the dysentery ward of the make-shift hospital, the Jap guards would never go in there, because it stank to high heaven and they were too health conscious and concerned about catching something.

After the Tenko parade had finished the search for Hardy really began in earnest. He still could not be found, so then they had no choice but to tell the Japs; they did not believe our officer was not involved, they beat him up and locked us all away for about a week I think.

The guards took all our rations that we had saved up and they joked with us that we would all be executed. One day we were being instructed by a Japanese guard who liked to try and speak English, we eventually asked him what happened to Corporal Hardy. He told us that he had cerebral malaria, a fever of the brain, so they shot him, simple as that.

Apparently Hardy had been walking along the streets, but your white you see and every bodies black around you, he was picked up by the Burmese Police. They shot him for escaping, the Japs would shoot their own soldiers for letting a prisoner get out, so they had no worries in shooting Corporal Hardy."

Update 16/02/2013.

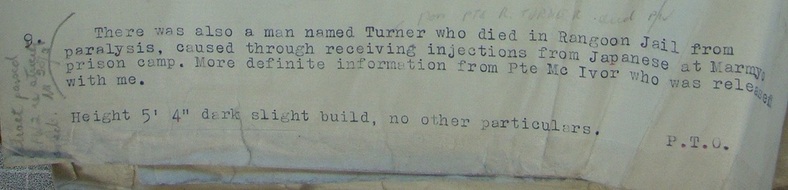

From the 13th King's missing in action reports, comes this short witness statement from Corporal. H. R. Sole, who had put together a list of all personnel he had information about, in particular those held as POW's in Rangoon Jail. Seen below is his recollection in regards to Pte. Robert Turner, formerly of the Durham Light Infantry. Apologies for the quality of the image, especially the papers creases in the corners.

From the IWM sound recording made by Pte. Fred Holloman, here is a paraphrased quotation telling the story of Leslie Hardy, who Holloman refers to as Corporal. To listen to Fred Holloman's interview, please click on the link here:

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80015837

The story about Corporal Hardy can be found on Reel 3 of the audio recording.

"Then the next day a chap named Corporal Hardy well, he must have had fever of the brain, because he walked out of the main gates.

Suddenly it was Tenko (roll-call) and the officers in charge are rushing around asking where Hardy was, we were looking all over the place, but could not find him anywhere. The officer in charge said he must be in the camp somewhere, as he would be a raving lunatic to try and escape.

The officer decided to put Hardy's name down as being in the dysentery ward of the make-shift hospital, the Jap guards would never go in there, because it stank to high heaven and they were too health conscious and concerned about catching something.

After the Tenko parade had finished the search for Hardy really began in earnest. He still could not be found, so then they had no choice but to tell the Japs; they did not believe our officer was not involved, they beat him up and locked us all away for about a week I think.

The guards took all our rations that we had saved up and they joked with us that we would all be executed. One day we were being instructed by a Japanese guard who liked to try and speak English, we eventually asked him what happened to Corporal Hardy. He told us that he had cerebral malaria, a fever of the brain, so they shot him, simple as that.

Apparently Hardy had been walking along the streets, but your white you see and every bodies black around you, he was picked up by the Burmese Police. They shot him for escaping, the Japs would shoot their own soldiers for letting a prisoner get out, so they had no worries in shooting Corporal Hardy."

Update 16/02/2013.

From the 13th King's missing in action reports, comes this short witness statement from Corporal. H. R. Sole, who had put together a list of all personnel he had information about, in particular those held as POW's in Rangoon Jail. Seen below is his recollection in regards to Pte. Robert Turner, formerly of the Durham Light Infantry. Apologies for the quality of the image, especially the papers creases in the corners.

Update 21/02/2013.

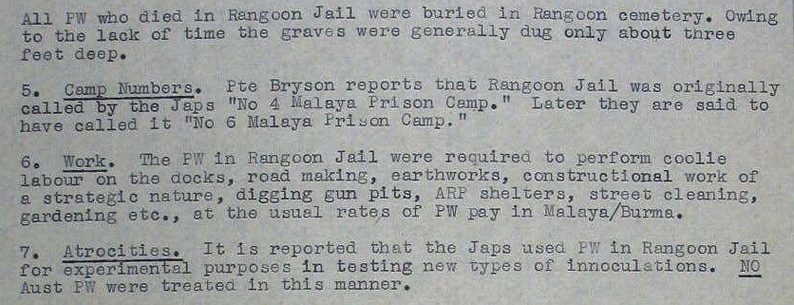

From the National Archives of Australia, a short POW liberation report about the conditions experienced in Rangoon Jail during the years 1942-45. The report is in relation to Australian personnel only, but does shed more light on the subject of medical experimentation in the camp. Thanks go to John C. for pointing me in the direction of these papers.

From the National Archives of Australia, a short POW liberation report about the conditions experienced in Rangoon Jail during the years 1942-45. The report is in relation to Australian personnel only, but does shed more light on the subject of medical experimentation in the camp. Thanks go to John C. for pointing me in the direction of these papers.

From the personal memoirs of Ted Freeman, a driver with the 2nd battalion King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, who was taken prisoner during the retreat in 1942.

"The beatings and humiliations of us all continued for two years on and off, so you can image our state of mind after three years. We learned orders ‘parrot fashion’ in Japanese, but the language was a great problem. There were notices placed around to the effect that anyone raising his hand, for whatever reason, against a Japanese soldier would be shot. There was a man with me in my little party who was crucified upside down before my eyes and left for several hours in the hot sun, simply because he did not bow to a patrolling guard, and there were two men shot in cold blood. Just two examples of the cruelty of the Japanese.

One month after being taken prisoner, whilst still in a fit condition, I was taken with 23 others to another part of the prison (Rangoon Jail) to become a guinea pig for Japanese doctors. We were subjected to 3 injections of Dengue fever, blood tests and temperature checks. These experiments lasted for a period of 4 weeks. Two men died later on, but the cause of their death was unknown. The men in the experiments were from West Yorkshires, the Inniskillings, Cameronians and the Glosters. I was the only KOYLI at that time in prison.

The food in prison consisted of rice and dahl (split peas), later to improve to rice and watery vegetable stew. This was our staple diet for three years and I worked it out at over 3000 meals of rice for each man. Incidentally, the food we were given during the guinea pigs stage was rice and jagri lumps (a form of solidified raw sugar), but day in day out, year in year out, the food was the same – steamed rice with a few vegetables. Hard labour, short on food, short on clothing and no other material things at all, except for what we could steal."

So it seems as though medical experiments were nothing new for the prisoners of Rangoon Jail.

Update 24/10/2015.

After the prisoners held at Rangoon Jail were liberated in early May 1945, they were interrogated by a team of Army and RAF investigators who took down witness statements from the men in relation to the death of fellow POW's and the treatment they had received from their Japanese captors. When questioned about attempted escapes from the jail, several men recounted the story of Leslie Hardy. Here is how the investigation team noted these accounts in their final report:

Instances of escape at Rangoon.

There is only one example of the escape of a white POW from the jail and this was the case of a British Other Rank who had been sick with malaria, and who, it is believed was delirious. Some time in June or July 1943 he walked out at night with his night clothes on and no kit. There is a prevalent belief that he had been used as a 'guinea pig' by Japanese doctors at Maymyo and that he had been subjected to a series of injections and observations, which had left him a chronic victim of malaria. There is however, no direct evidence of this.

The escaper was re-captured some 36 hours later, some twelve miles from the jail and brought back. Reprisals were taken against the POW Block Commander, against the POW sleeping next to the escaper and against prisoners in general. Reprisals in the first instance took the form of beatings. The Japanese authorities placed the escaper in solitary confinement with its attendant privations and stated that he would suffer the highest punishment. He was removed after a time and was never seen subsequently, although there is one report that the Japanese stated he had died of malaria.

The prisoners were given little water for a time, with the resultant deaths referred to elsewhere in this report. They were also warned that if such a thing happened again, very serious measures would be taken against them.

There can be no doubt that the report relates to Leslie Hardy, although no names are ever mentioned within the full document, especially when referring to uncorroborated evidence or statements given by third parties. Seen below is Hardy's entry on the missing in action listing for 5 Column during Operation Longcloth. The date given, 28th March 1943, matches up with 5 Column's main engagement with the Japanese at the village of Hintha, during which time several casualties were incurred and on withdrawal over 100 men were separated from the main column.

"The beatings and humiliations of us all continued for two years on and off, so you can image our state of mind after three years. We learned orders ‘parrot fashion’ in Japanese, but the language was a great problem. There were notices placed around to the effect that anyone raising his hand, for whatever reason, against a Japanese soldier would be shot. There was a man with me in my little party who was crucified upside down before my eyes and left for several hours in the hot sun, simply because he did not bow to a patrolling guard, and there were two men shot in cold blood. Just two examples of the cruelty of the Japanese.

One month after being taken prisoner, whilst still in a fit condition, I was taken with 23 others to another part of the prison (Rangoon Jail) to become a guinea pig for Japanese doctors. We were subjected to 3 injections of Dengue fever, blood tests and temperature checks. These experiments lasted for a period of 4 weeks. Two men died later on, but the cause of their death was unknown. The men in the experiments were from West Yorkshires, the Inniskillings, Cameronians and the Glosters. I was the only KOYLI at that time in prison.

The food in prison consisted of rice and dahl (split peas), later to improve to rice and watery vegetable stew. This was our staple diet for three years and I worked it out at over 3000 meals of rice for each man. Incidentally, the food we were given during the guinea pigs stage was rice and jagri lumps (a form of solidified raw sugar), but day in day out, year in year out, the food was the same – steamed rice with a few vegetables. Hard labour, short on food, short on clothing and no other material things at all, except for what we could steal."

So it seems as though medical experiments were nothing new for the prisoners of Rangoon Jail.

Update 24/10/2015.

After the prisoners held at Rangoon Jail were liberated in early May 1945, they were interrogated by a team of Army and RAF investigators who took down witness statements from the men in relation to the death of fellow POW's and the treatment they had received from their Japanese captors. When questioned about attempted escapes from the jail, several men recounted the story of Leslie Hardy. Here is how the investigation team noted these accounts in their final report:

Instances of escape at Rangoon.

There is only one example of the escape of a white POW from the jail and this was the case of a British Other Rank who had been sick with malaria, and who, it is believed was delirious. Some time in June or July 1943 he walked out at night with his night clothes on and no kit. There is a prevalent belief that he had been used as a 'guinea pig' by Japanese doctors at Maymyo and that he had been subjected to a series of injections and observations, which had left him a chronic victim of malaria. There is however, no direct evidence of this.

The escaper was re-captured some 36 hours later, some twelve miles from the jail and brought back. Reprisals were taken against the POW Block Commander, against the POW sleeping next to the escaper and against prisoners in general. Reprisals in the first instance took the form of beatings. The Japanese authorities placed the escaper in solitary confinement with its attendant privations and stated that he would suffer the highest punishment. He was removed after a time and was never seen subsequently, although there is one report that the Japanese stated he had died of malaria.

The prisoners were given little water for a time, with the resultant deaths referred to elsewhere in this report. They were also warned that if such a thing happened again, very serious measures would be taken against them.

There can be no doubt that the report relates to Leslie Hardy, although no names are ever mentioned within the full document, especially when referring to uncorroborated evidence or statements given by third parties. Seen below is Hardy's entry on the missing in action listing for 5 Column during Operation Longcloth. The date given, 28th March 1943, matches up with 5 Column's main engagement with the Japanese at the village of Hintha, during which time several casualties were incurred and on withdrawal over 100 men were separated from the main column.

Update 11/03/2017.

After recently re-reading the book Rats of Rangoon, by Lionel Hudson, I came across this short quote in regards to the use of experimental injections by the Japanese medics inside Rangoon Jail. The author (Hudson) was recounting the sad death of RAF Warrant Officer John William King, who had perished just a few short weeks before liberation and went on to describe:

At least King was not killed by a Japanese swan song injection; most of the chaps who have died here have been given an injection under the skin in the arm, involving a large dose of a colourless, odourless serum. Nobody has ever recovered from one. A 'waddy' shot, we call them.

After recently re-reading the book Rats of Rangoon, by Lionel Hudson, I came across this short quote in regards to the use of experimental injections by the Japanese medics inside Rangoon Jail. The author (Hudson) was recounting the sad death of RAF Warrant Officer John William King, who had perished just a few short weeks before liberation and went on to describe:

At least King was not killed by a Japanese swan song injection; most of the chaps who have died here have been given an injection under the skin in the arm, involving a large dose of a colourless, odourless serum. Nobody has ever recovered from one. A 'waddy' shot, we call them.

Copyright © Steve Fogden 2013.