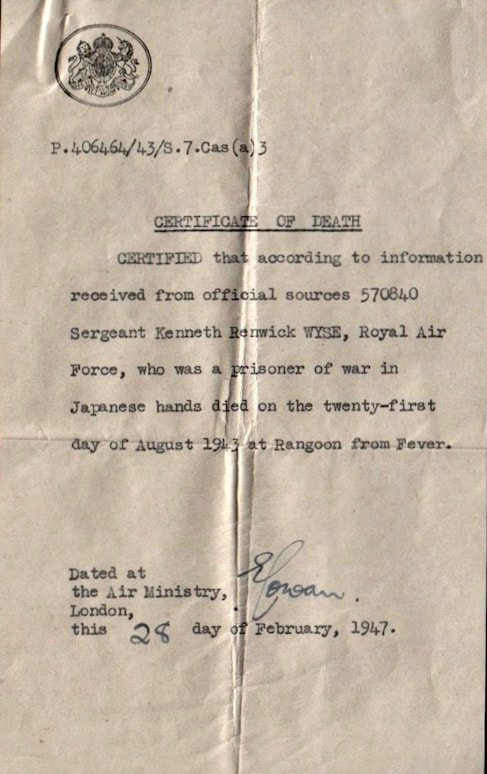

Sergeant Kenneth Renwick Wyse

Kenneth Renwick Wyse.

Kenneth Renwick Wyse.

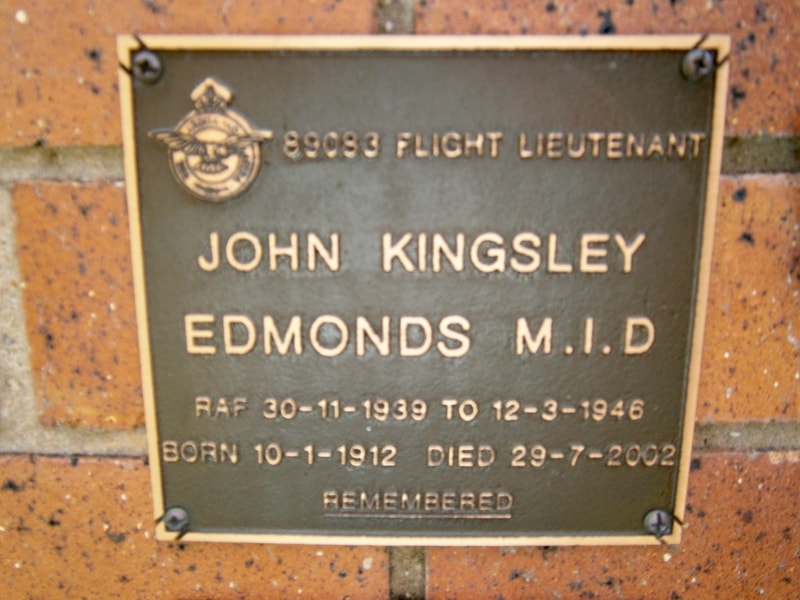

This story is dedicated to the efforts of Flight Lieutenant John Kingsley Edmonds, a truer more gallant friend you could not hope to meet.

In June 2013, I sent a letter to the niece of Kenneth Wyse in the hope of making contact with the family after reading through some documents in relation to his time in Burma during the first Chindit expedition in 1943:

Dear Mrs. Wright,

I sincerely hope this letter will find you well and not be too much of a surprise considering the reason for me contacting you in this way.

I am the grandson of a Chindit soldier who sadly also lost his life in Rangoon Jail in 1943. His name was Pte. Arthur Leslie Howney of the 13th King's Liverpool and a member of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade. I have over the last 5 years been researching these men, using mostly documents found at the National Archives in London, but also those held by the Imperial War Museum.

Last year I decided to create a website specifically to honour those men who took part in the first Chindit operation in 1943. The website address is www.chinditslongcloth1943.com

I have been successful in reaching many families with Chindit connections and also visited Burma with my mother in 2008, where we visited her father’s grave in Rangoon War Cemetery. Amongst the men I have information about are John Kingsley Edmonds and Lt.-Colonel L.A. Alexander. I have seen the material that you kindly left with the Imperial War Museum and this has helped me piece together the movements of the three men and others in April 1943.

The reason for contacting you is that I am beginning to prepare the story of Kenneth and John Kingsley Edmonds and their time together. I was hoping that you would be happy for me to use the information to help build the full story. I have already used one of the postcards to help show what happened to Colonel Alexander.

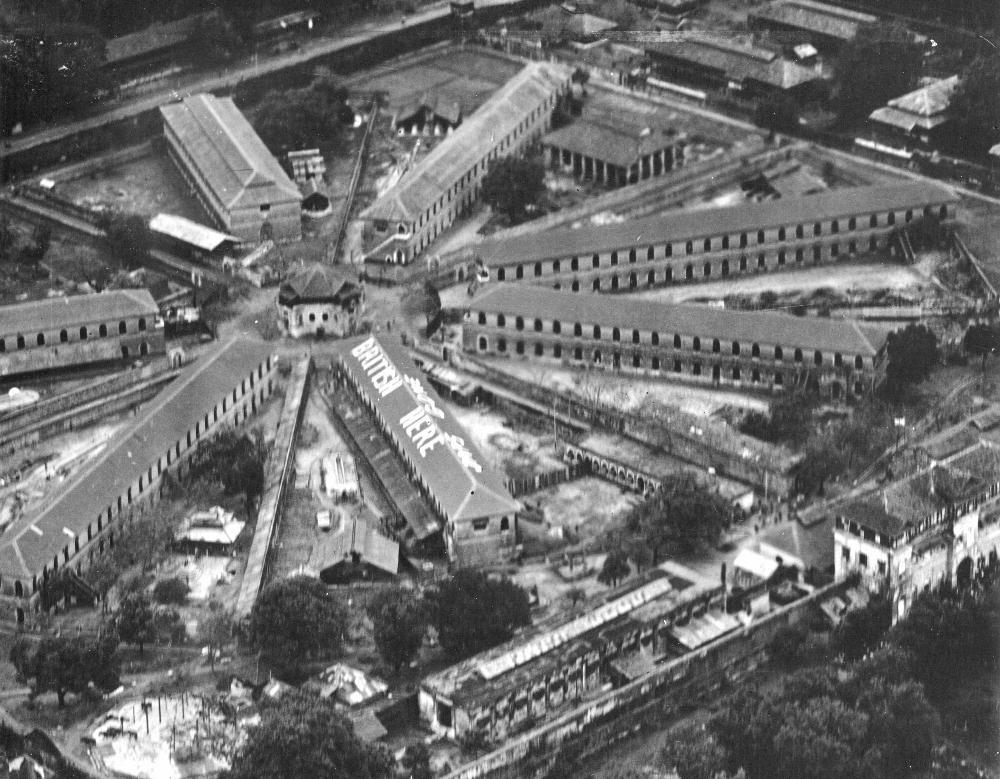

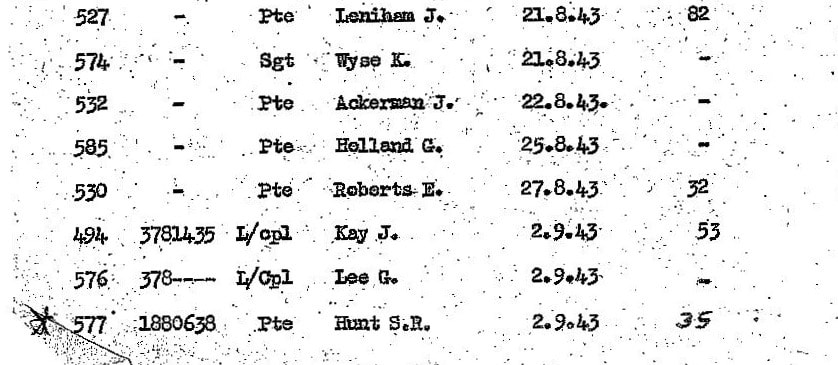

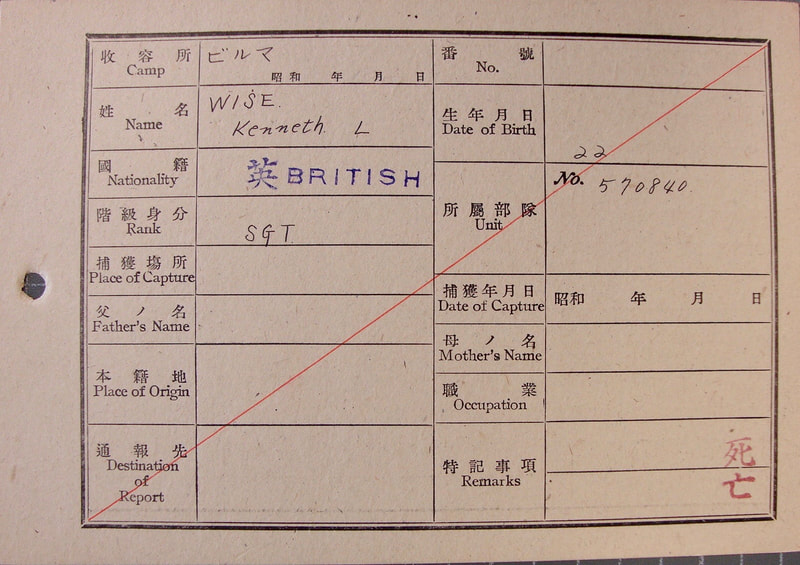

I have some documents that you may well be interested in, including Kenneth’s prisoner of war index card and his entry in the list of deaths for Block 6 of Rangoon Jail. I have also found some more evidence that the Japanese did indeed experiment with malaria drugs on the captured Chindits. Kenneth was one of the RAF Sergeants for No. 1 Column commanded by Major George Dunlop and Flight Lieutenant Edmonds was basically Kenneth’s boss in the column and they helped prepare the supply drop zones for the Dakotas and then call in the planes with ground radios. This was a vital job during the operation.

Around 240 Chindits were captured in 1943, sadly 60% of these perished, mostly in Rangoon Jail. They were originally buried in the Old Cantonment Cemetery in the city, before being moved over to Rangoon War Cemetery by the Imperial Graves Commission after the war.

Well, I am going to leave it there for now, I sincerely hope this letter has not caused you any upset or concern as this was not my intention. It would be wonderful to hear from you in the near future.

Yours faithfully, Stephen Fogden.

I was pleased to receive the following and swift reply:

Dear Mr. Fogden,

Thank you for your letter. Sgt. Kenneth Renwick Wyse was my mother's brother, technically my uncle but he died before I was born. If you have seen the archive at the imperial War Museum you will know his family history as I included a digest of this when I gave them the papers. I spent considerable time trying to trace the family of Ft. Lt. Edmonds and of Colonel Alexander but could find no one and from this distance the PRO is not accessible.

My grandfather did some research with the help of his friends in the Gordon Highlanders and the Black Watch at the end of WW2 and it was generally accepted that Orde Wingate had abandoned Alexander's Column to their fate and to the horrific loss of life and injury. I have a Penguin book that my grandfather obtained written by Charles J. Rolo titled Wingate's Raiders, it was published in 1945 but you may be able to find a copy somewhere. This may shed some light on the expedition at the time. I would send you the book, but it is in a very fragile state so I am reluctant to consign it to the Royal Mail.

I enclose a photograph of my uncle taken when he had just graduated from RAF Cranwell. I did have a picture of his grave but I suspect I gave it to the IWM as I cannot find it even on my computer. They did not give me his prisoner of war index card when I obtained his service record so it would be good to have that for our family archive. Neither do we have the records from the prisoner of war camp. I would be interested in your evidence about the Japanese experimenting with the prisoners. The fact that Kenneth had been abused in such a way caused dreadful distress to my grandparents.

My grandmother cherished the papers that we lodged with IWM and I still have the paper that she kept them in. However, although we are glad for the papers to be used for legitimate research and writing we would not like any pictures of the family published except of course those of Sergeant Wyse himself. I wish you well with your research and please do stay in touch.

Yours sincerely, Hilary Wright.

In June 2013, I sent a letter to the niece of Kenneth Wyse in the hope of making contact with the family after reading through some documents in relation to his time in Burma during the first Chindit expedition in 1943:

Dear Mrs. Wright,

I sincerely hope this letter will find you well and not be too much of a surprise considering the reason for me contacting you in this way.

I am the grandson of a Chindit soldier who sadly also lost his life in Rangoon Jail in 1943. His name was Pte. Arthur Leslie Howney of the 13th King's Liverpool and a member of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade. I have over the last 5 years been researching these men, using mostly documents found at the National Archives in London, but also those held by the Imperial War Museum.

Last year I decided to create a website specifically to honour those men who took part in the first Chindit operation in 1943. The website address is www.chinditslongcloth1943.com

I have been successful in reaching many families with Chindit connections and also visited Burma with my mother in 2008, where we visited her father’s grave in Rangoon War Cemetery. Amongst the men I have information about are John Kingsley Edmonds and Lt.-Colonel L.A. Alexander. I have seen the material that you kindly left with the Imperial War Museum and this has helped me piece together the movements of the three men and others in April 1943.

The reason for contacting you is that I am beginning to prepare the story of Kenneth and John Kingsley Edmonds and their time together. I was hoping that you would be happy for me to use the information to help build the full story. I have already used one of the postcards to help show what happened to Colonel Alexander.

I have some documents that you may well be interested in, including Kenneth’s prisoner of war index card and his entry in the list of deaths for Block 6 of Rangoon Jail. I have also found some more evidence that the Japanese did indeed experiment with malaria drugs on the captured Chindits. Kenneth was one of the RAF Sergeants for No. 1 Column commanded by Major George Dunlop and Flight Lieutenant Edmonds was basically Kenneth’s boss in the column and they helped prepare the supply drop zones for the Dakotas and then call in the planes with ground radios. This was a vital job during the operation.

Around 240 Chindits were captured in 1943, sadly 60% of these perished, mostly in Rangoon Jail. They were originally buried in the Old Cantonment Cemetery in the city, before being moved over to Rangoon War Cemetery by the Imperial Graves Commission after the war.

Well, I am going to leave it there for now, I sincerely hope this letter has not caused you any upset or concern as this was not my intention. It would be wonderful to hear from you in the near future.

Yours faithfully, Stephen Fogden.

I was pleased to receive the following and swift reply:

Dear Mr. Fogden,

Thank you for your letter. Sgt. Kenneth Renwick Wyse was my mother's brother, technically my uncle but he died before I was born. If you have seen the archive at the imperial War Museum you will know his family history as I included a digest of this when I gave them the papers. I spent considerable time trying to trace the family of Ft. Lt. Edmonds and of Colonel Alexander but could find no one and from this distance the PRO is not accessible.

My grandfather did some research with the help of his friends in the Gordon Highlanders and the Black Watch at the end of WW2 and it was generally accepted that Orde Wingate had abandoned Alexander's Column to their fate and to the horrific loss of life and injury. I have a Penguin book that my grandfather obtained written by Charles J. Rolo titled Wingate's Raiders, it was published in 1945 but you may be able to find a copy somewhere. This may shed some light on the expedition at the time. I would send you the book, but it is in a very fragile state so I am reluctant to consign it to the Royal Mail.

I enclose a photograph of my uncle taken when he had just graduated from RAF Cranwell. I did have a picture of his grave but I suspect I gave it to the IWM as I cannot find it even on my computer. They did not give me his prisoner of war index card when I obtained his service record so it would be good to have that for our family archive. Neither do we have the records from the prisoner of war camp. I would be interested in your evidence about the Japanese experimenting with the prisoners. The fact that Kenneth had been abused in such a way caused dreadful distress to my grandparents.

My grandmother cherished the papers that we lodged with IWM and I still have the paper that she kept them in. However, although we are glad for the papers to be used for legitimate research and writing we would not like any pictures of the family published except of course those of Sergeant Wyse himself. I wish you well with your research and please do stay in touch.

Yours sincerely, Hilary Wright.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Hilary for all her help and assistance in bringing the story of her uncle to these website pages.

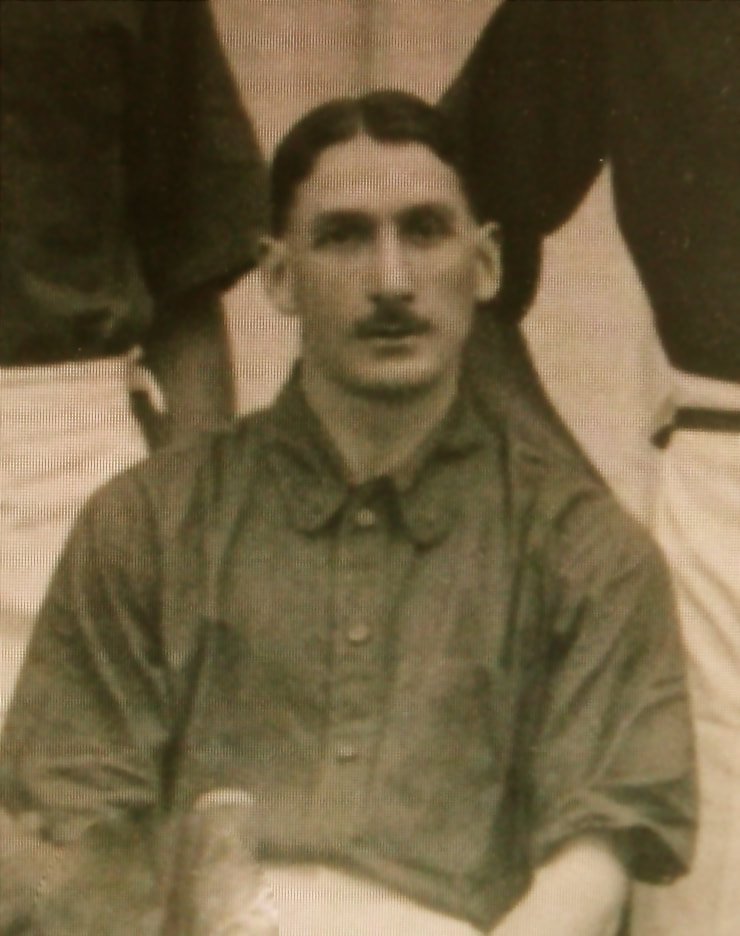

Kenneth Renwick Wyse was born on the 13th March 1921 at Kingskettle in Fife and was the son of David and Jean Stuart Wyse, eventually from Port Glasgow in Renfrewshire. On moving to Port Glasgow, David Wyse worked as an optician/chemist running his own shop and young Kenneth attended the local Greenock High School.

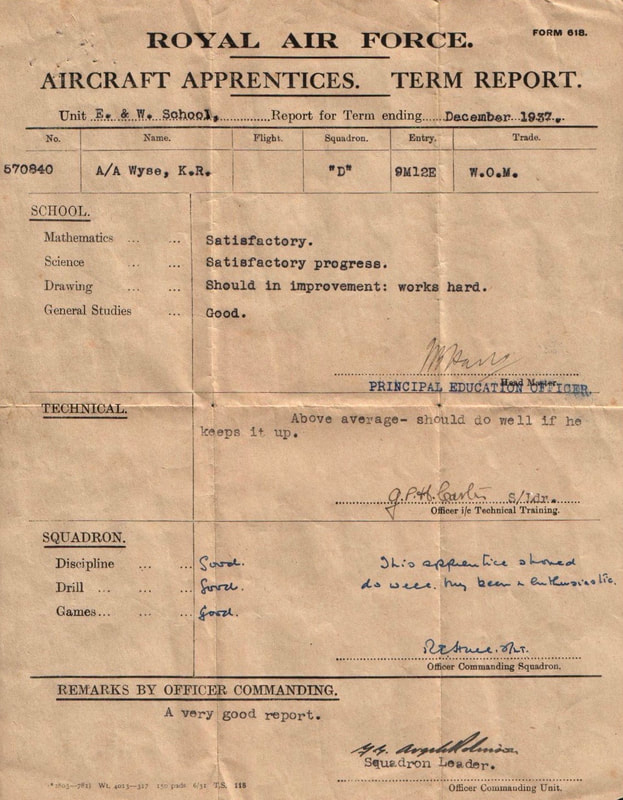

Kenneth was just 16 years old, when he enlisted into the RAF on the 12th January 1937 and began his intended 12 year service at RAF Halton in Buckinghamshire. With the RAF service number 570840, he trained as a wireless and electrical mechanic and saw action in the Middle East during WW2, before being transferred to the Head Quarters of 224 Group in India. Kenneth was a keen sportsman during his time in the RAF, winning medals in athletics, especially, in long jump, shot put and discus.

In late 1942, he volunteered for a special mission advertised at the many RAF bases and facilities and on the 17th October 1942 was posted to the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade at the Saugor training camp in the Central Provinces of India. Kenneth was promoted to Sergeant on the 31st December that same year whilst training with 77 Brigade. He was allocated as part of the RAF Air Liaison team for Southern Group HQ and came under the command of Flight Lieutenant John Kingsley Edmonds, an Australian pilot who had recently been fighting the Japanese in New Guinea.

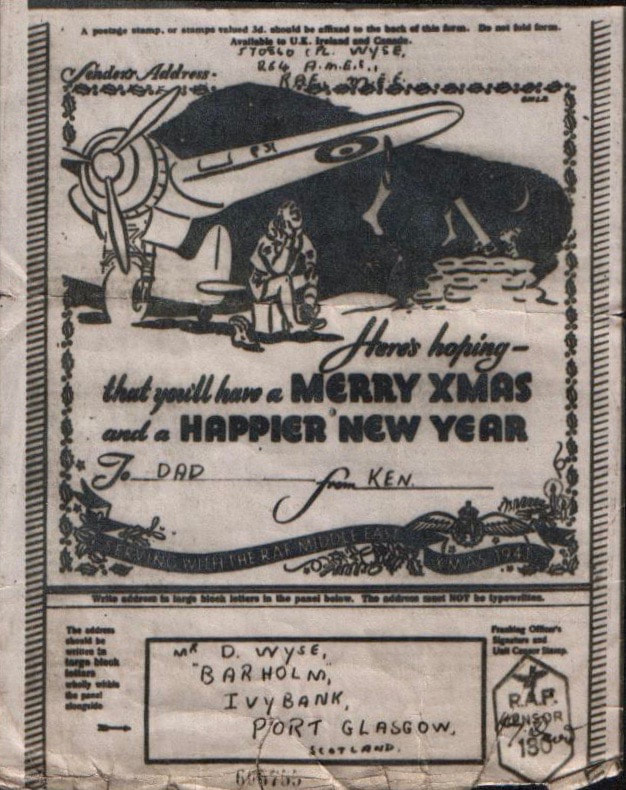

Seen below are two images from Kenneth's RAF records, his RAF apprentice record for 1937 and his official RAF identification photograph. Also shown is a Christmas Airgraph letter sent home by Kenneth to his family in 1941 whilst serving in the Middle East. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Kenneth Renwick Wyse was born on the 13th March 1921 at Kingskettle in Fife and was the son of David and Jean Stuart Wyse, eventually from Port Glasgow in Renfrewshire. On moving to Port Glasgow, David Wyse worked as an optician/chemist running his own shop and young Kenneth attended the local Greenock High School.

Kenneth was just 16 years old, when he enlisted into the RAF on the 12th January 1937 and began his intended 12 year service at RAF Halton in Buckinghamshire. With the RAF service number 570840, he trained as a wireless and electrical mechanic and saw action in the Middle East during WW2, before being transferred to the Head Quarters of 224 Group in India. Kenneth was a keen sportsman during his time in the RAF, winning medals in athletics, especially, in long jump, shot put and discus.

In late 1942, he volunteered for a special mission advertised at the many RAF bases and facilities and on the 17th October 1942 was posted to the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade at the Saugor training camp in the Central Provinces of India. Kenneth was promoted to Sergeant on the 31st December that same year whilst training with 77 Brigade. He was allocated as part of the RAF Air Liaison team for Southern Group HQ and came under the command of Flight Lieutenant John Kingsley Edmonds, an Australian pilot who had recently been fighting the Japanese in New Guinea.

Seen below are two images from Kenneth's RAF records, his RAF apprentice record for 1937 and his official RAF identification photograph. Also shown is a Christmas Airgraph letter sent home by Kenneth to his family in 1941 whilst serving in the Middle East. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

As mentioned above, Kenneth Wyse formed part of the RAF Liaison section for Southern Group on Operation Longcloth. This was a predominately Gurkha unit comprising two Chindit columns (Nos. 1 & 2) and a Group Head Quarters. Southern Group was commanded by Colonel Leigh Arbuthnot Alexander of the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles.

Southern Group were used during Operation Longcloth as a decoy unit, purposely attracting the attention of local Japanese patrols in February/March 1943, while Northern Section, operating slightly to the north managed to pass through the enemy lines unmolested. In general terms this feint and deception performed by Southern Group worked well, but came at a great cost.

Southern Group crossed the Chindwin on 15/16th February 1943 at a place called Auktang. Their orders were to march toward their own prime objective, the rail station at Kyaikthin. They marched openly along well known local trails and paths and also received a large supply drop from the air, which must have announced their presence in the area to the Japanese. The decoy group were accompanied at this time by a Company of Sikh Mountain Artillery and a section of Seaforth Highlanders. This supplementary unit were to create a further diversion for Wingate by attacking the town of Pantha, alerting the enemy to the possibility that there might well be a full-scale re-invasion taking place.

On the 2nd March Columns 1 and 2 had reached the outskirts of Kyaikthin, Major George Dunlop, commander of No. 1 Column, was given the order to blow up the railway bridge nearby, whilst No. 2 Column under the command of Major Arthur Emmett along with Group HQ were to head on towards the rail station itself. What neither group realised was that the Japanese had by now closed in on the unsuspecting Chindits and lay in wait just a short way up the tracks. To make matters worse the two Gurkha columns had also now lost radio contact. Column 2 and Group Head Quarters in the black of night stumbled into the enemy ambush which straddled both sides of the railway line embankment. Here is how a survivor of the ambush, Lieutenant Ian MacHorton recalled that moment:

"We shuffled to a halt as the guides probed forward. There came the sound of just one bang up front, then an inferno of noise engulfed the world around me. There came the high-pitched staccato scream of a machine gun, then overwhelmingly many others joined in, the crash and ping of rifle bullets, the banging of grenades as the battle reached a fearful crescendo. Men and mules were lying, twisted and contorted, twitching and writhing, others were still erect, stark in the moonlight, heaving and jerking in the midst of this chaos. Then a sinister scuffling noise made by men of all kinds in close combat. The close combat of bayonet and kukri, the fanatical, personal slaughter with blood-dripping cold steel."

From this moment on Southern Group were always struggling to regain some sense of order and although the unit did reassemble a few days later at the Irrawaddy River, their continued journey behind enemy lines in 1943 proved difficult in the extreme. To read more about Southern Group and its experiences on Operation Longcloth, please click on the following links:

Lieutenant-Colonel L.A. Alexander

Lieutenant Victor St. George De La Rue

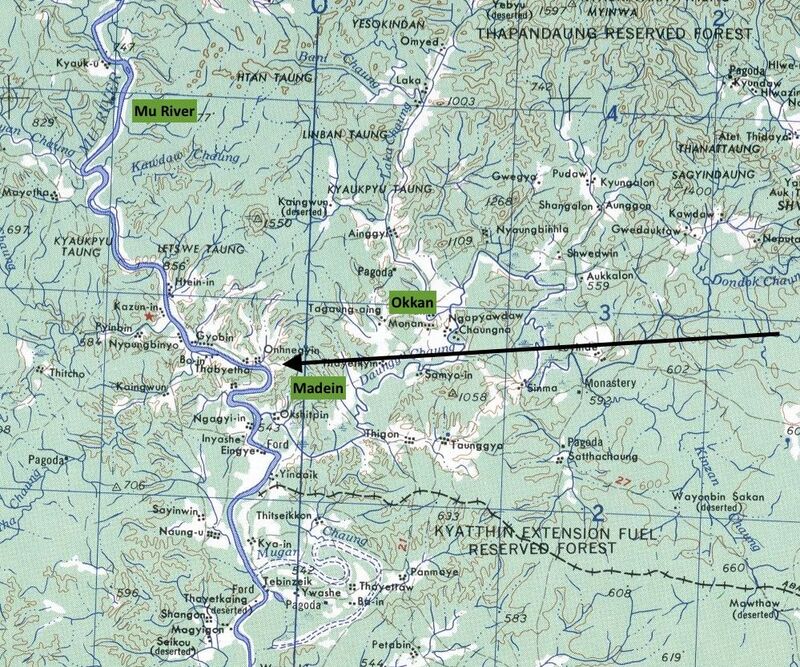

After dispersal had been called in late March, the remnants of Southern Group, now condensed into one column and commanded by Major Dunlop had managed to re-cross the Irrawaddy and were now approaching the next watery obstacle, the Mu River. On the morning of the 26th April the party bivouacked in the teak forest south of Map Point 1070, and close to the village of Okkan. The group were now some 350 in number and were roughly speaking re-tracing their outbound steps. From the diary of George Dunlop:

"At about 1100 hours, Lieutenant Clarke roused me to say that there were villagers below us. I ordered out a patrol to collect them for questioning. On sight of the patrol they ran away. After a short while reports came back that there were Japanese coming up the hill. I did not take this too seriously at first, but it did turn out to be true, the next thing I saw was my Gurkha patrol running past me."

In the confusion both Gurkha Rifles and enemy troops had raced past the unsuspecting commander and chaos ensued. After things had settled down somewhat, Dunlop collected what men he could find and decided to move forward toward the nearby chaung (stream). Several of his officers were now missing from the main party. With the Burma Rifle Scouts now leading, the group pushed into some thick scrub on the other side of the chaung, for 10 minutes or so they moved slowly forward in the hope that the missing men might catch up, suddenly firing broke out to the rear. George Dunlop continues:

"As it turned out a party of the enemy had come up the river just in time to see the last of our men enter the jungle. They opened up at random, though with heavy fire. I gave the order for everyone to keep moving. The enemy began a sort of searching fire and several mortar bombs landed nearby. One landed so close I could feel the blast and hear the splinters, a RAF Sergeant marching next to me was hit.

Coming to open ground I gave the order to extend by platoons and we doubled across in quite good order. After reaching good cover on the other side I halted to check up on things. It was then that Clarke came up to me looking ghastly. I asked him what was wrong and he told me that the last mortar bomb had blown away most of the Colonel's and officer De La Rue's legs. Edmonds, the RAF Liaison officer and some orderlies had carried them away into the jungle, but that no one could now be found who knew of their whereabouts. The news had taken all this time to reach Clarke who spoke a fair amount of Gurkhali, and had never reached me at all, although the Colonel's party were within twenty five yards of me in the thick scrub."

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this section of the story, including a map of the area around the Mu River. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Southern Group were used during Operation Longcloth as a decoy unit, purposely attracting the attention of local Japanese patrols in February/March 1943, while Northern Section, operating slightly to the north managed to pass through the enemy lines unmolested. In general terms this feint and deception performed by Southern Group worked well, but came at a great cost.

Southern Group crossed the Chindwin on 15/16th February 1943 at a place called Auktang. Their orders were to march toward their own prime objective, the rail station at Kyaikthin. They marched openly along well known local trails and paths and also received a large supply drop from the air, which must have announced their presence in the area to the Japanese. The decoy group were accompanied at this time by a Company of Sikh Mountain Artillery and a section of Seaforth Highlanders. This supplementary unit were to create a further diversion for Wingate by attacking the town of Pantha, alerting the enemy to the possibility that there might well be a full-scale re-invasion taking place.

On the 2nd March Columns 1 and 2 had reached the outskirts of Kyaikthin, Major George Dunlop, commander of No. 1 Column, was given the order to blow up the railway bridge nearby, whilst No. 2 Column under the command of Major Arthur Emmett along with Group HQ were to head on towards the rail station itself. What neither group realised was that the Japanese had by now closed in on the unsuspecting Chindits and lay in wait just a short way up the tracks. To make matters worse the two Gurkha columns had also now lost radio contact. Column 2 and Group Head Quarters in the black of night stumbled into the enemy ambush which straddled both sides of the railway line embankment. Here is how a survivor of the ambush, Lieutenant Ian MacHorton recalled that moment:

"We shuffled to a halt as the guides probed forward. There came the sound of just one bang up front, then an inferno of noise engulfed the world around me. There came the high-pitched staccato scream of a machine gun, then overwhelmingly many others joined in, the crash and ping of rifle bullets, the banging of grenades as the battle reached a fearful crescendo. Men and mules were lying, twisted and contorted, twitching and writhing, others were still erect, stark in the moonlight, heaving and jerking in the midst of this chaos. Then a sinister scuffling noise made by men of all kinds in close combat. The close combat of bayonet and kukri, the fanatical, personal slaughter with blood-dripping cold steel."

From this moment on Southern Group were always struggling to regain some sense of order and although the unit did reassemble a few days later at the Irrawaddy River, their continued journey behind enemy lines in 1943 proved difficult in the extreme. To read more about Southern Group and its experiences on Operation Longcloth, please click on the following links:

Lieutenant-Colonel L.A. Alexander

Lieutenant Victor St. George De La Rue

After dispersal had been called in late March, the remnants of Southern Group, now condensed into one column and commanded by Major Dunlop had managed to re-cross the Irrawaddy and were now approaching the next watery obstacle, the Mu River. On the morning of the 26th April the party bivouacked in the teak forest south of Map Point 1070, and close to the village of Okkan. The group were now some 350 in number and were roughly speaking re-tracing their outbound steps. From the diary of George Dunlop:

"At about 1100 hours, Lieutenant Clarke roused me to say that there were villagers below us. I ordered out a patrol to collect them for questioning. On sight of the patrol they ran away. After a short while reports came back that there were Japanese coming up the hill. I did not take this too seriously at first, but it did turn out to be true, the next thing I saw was my Gurkha patrol running past me."

In the confusion both Gurkha Rifles and enemy troops had raced past the unsuspecting commander and chaos ensued. After things had settled down somewhat, Dunlop collected what men he could find and decided to move forward toward the nearby chaung (stream). Several of his officers were now missing from the main party. With the Burma Rifle Scouts now leading, the group pushed into some thick scrub on the other side of the chaung, for 10 minutes or so they moved slowly forward in the hope that the missing men might catch up, suddenly firing broke out to the rear. George Dunlop continues:

"As it turned out a party of the enemy had come up the river just in time to see the last of our men enter the jungle. They opened up at random, though with heavy fire. I gave the order for everyone to keep moving. The enemy began a sort of searching fire and several mortar bombs landed nearby. One landed so close I could feel the blast and hear the splinters, a RAF Sergeant marching next to me was hit.

Coming to open ground I gave the order to extend by platoons and we doubled across in quite good order. After reaching good cover on the other side I halted to check up on things. It was then that Clarke came up to me looking ghastly. I asked him what was wrong and he told me that the last mortar bomb had blown away most of the Colonel's and officer De La Rue's legs. Edmonds, the RAF Liaison officer and some orderlies had carried them away into the jungle, but that no one could now be found who knew of their whereabouts. The news had taken all this time to reach Clarke who spoke a fair amount of Gurkhali, and had never reached me at all, although the Colonel's party were within twenty five yards of me in the thick scrub."

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this section of the story, including a map of the area around the Mu River. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

It is not clear if the RAF Sergeant mentioned by Dunlop in his diary was Kenneth Wyse? There was another RAF NCO present within the party, a man called Sergeant Hayes. Flight Lieutenant Edmonds had tried to lead his group across the chaung and in to the safety of the scrub-jungle on the far bank. We know he was physically carrying Colonel Alexander at this point, but it must be presumed that Kenneth was also with him alongside Lt. De la Rue and possibly some others.

Part of the information and documents placed at the Imperial War Museum by the Wyse family included a short diary, recorded by John Edmonds on four postcard type photographs belonging to Kenneth Wyse, which describes the days following the incident at the Mu River. It is the information written on these postcards that tells more or less the story and sad fate of Kenneth Wyse and his eventual demise as a prisoner of war.

In respecting the families wish, that the images on the postcard photographs not be shown on these website pages, I have taken the trouble to transcribe Flight Lieutenant Edmonds' entries instead. The time period involved covers roughly 16 weeks and perhaps by using these personal photographs of Kenneth's family, Edmonds thought the Japanese guards would be less likely to confiscate the items, not realising that they were in fact a secret diary, something that was not allowed to be kept inside Rangoon Jail.

Postcard No. 1 dated April 28:

Both Ken and myself (Edmonds) and Col. Alexander wounded- Col. A. seriously wounded in thigh and bleeding badly- Ken has a slight wound in the hip and two bullets thru stomach.

We managed to carry Col. A. several hundred yards, but we were too weak to go further- Col. A. died.

We hid in some long grass, intending to make our getaway after dark. our wounds stiffened up- neither of us could walk- very thirsty-

Japs are searching for us. Ken says his mother will know that he is wounded- Japs pass within 10ft of us- our chances look very slim.

Ken appears unconscious- have no hat- sun very hot- would give anything for a drink. Shots being fired near and a good deal…………..

(narrative ends on this postcard).

Postcard No. 2: (Some of the words on this page have worn away over time, but is now clear that they have been captured and are now being transported to Maymyo).

Japs plug our wounds and give us water and food. They are very young and fanatical- Ken is capable of walking but is in pain.

(Some of the narrative is to faint to read).

At Monya. Interrogated 3 times today………………………………………………………………..

Am P…………………………………………………………..both told more…………………….

………………………………………………………………………………………prove………….

Still…….medical treatment- 5 days in cattle truck- Japs more hostile. I am still unable to walk- Ken much better.

At Kalaw. Midnight interrogation by candle light. Threat of……….etc. Food very poor- Ken much better- still unable to walk myself- guards rough.

At Maymyo. Am being taken to Rangoon tomorrow- Ken being left here-back of…………….

Postcard No. 3: (The first three sentences are too faint to interpret but it is clear both men are now at Rangoon Jail).

Rangoon…………………………………………………………………………………..

……………………………………………………………………………………………..

…………………………………………………………………………………………….

…………………….. Am in cell No. 82- filthy conditions- somebody died last night from dysentery- unable to get any medical treatment or a wash. Guards bashed me up last night. All guards appear…….lot. Cell searched and Ken's wallet and photos taken- I made a complaint and said the photo was a picture of my wife and got it back.

Several prisoners very sick with dysentery, Ken arrives from Maymyo- has recovered from wounds. Has frequent doses of malaria- No Quinine. Was experimented on by the Japs with fever.

Aug. 20: Ken very bad with high fever-unable to get any quinine-Unconscious and rambling in speech-talks of his family-appears to think he is in France. Seems to recognise me at times then unconscious again. I do not think he will live the night. Aug. 21 Ken died-one of the bravest chaps I have seen in this war-buried in Rangoon.

Postcard No. 4:

Buried Ken today in Rangoon. Held short service, but I could not remember much of it, so had to make most of it up. Japs gave us very little time. They are frightened of RAF bombers.

Hope to be out of here by Christmas. 6 have died in the last 12 weeks and many more will die unless we get more food and some medical supplies-No Red Cross. Japs very confident of victory.

Part of the information and documents placed at the Imperial War Museum by the Wyse family included a short diary, recorded by John Edmonds on four postcard type photographs belonging to Kenneth Wyse, which describes the days following the incident at the Mu River. It is the information written on these postcards that tells more or less the story and sad fate of Kenneth Wyse and his eventual demise as a prisoner of war.

In respecting the families wish, that the images on the postcard photographs not be shown on these website pages, I have taken the trouble to transcribe Flight Lieutenant Edmonds' entries instead. The time period involved covers roughly 16 weeks and perhaps by using these personal photographs of Kenneth's family, Edmonds thought the Japanese guards would be less likely to confiscate the items, not realising that they were in fact a secret diary, something that was not allowed to be kept inside Rangoon Jail.

Postcard No. 1 dated April 28:

Both Ken and myself (Edmonds) and Col. Alexander wounded- Col. A. seriously wounded in thigh and bleeding badly- Ken has a slight wound in the hip and two bullets thru stomach.

We managed to carry Col. A. several hundred yards, but we were too weak to go further- Col. A. died.

We hid in some long grass, intending to make our getaway after dark. our wounds stiffened up- neither of us could walk- very thirsty-

Japs are searching for us. Ken says his mother will know that he is wounded- Japs pass within 10ft of us- our chances look very slim.

Ken appears unconscious- have no hat- sun very hot- would give anything for a drink. Shots being fired near and a good deal…………..

(narrative ends on this postcard).

Postcard No. 2: (Some of the words on this page have worn away over time, but is now clear that they have been captured and are now being transported to Maymyo).

Japs plug our wounds and give us water and food. They are very young and fanatical- Ken is capable of walking but is in pain.

(Some of the narrative is to faint to read).

At Monya. Interrogated 3 times today………………………………………………………………..

Am P…………………………………………………………..both told more…………………….

………………………………………………………………………………………prove………….

Still…….medical treatment- 5 days in cattle truck- Japs more hostile. I am still unable to walk- Ken much better.

At Kalaw. Midnight interrogation by candle light. Threat of……….etc. Food very poor- Ken much better- still unable to walk myself- guards rough.

At Maymyo. Am being taken to Rangoon tomorrow- Ken being left here-back of…………….

Postcard No. 3: (The first three sentences are too faint to interpret but it is clear both men are now at Rangoon Jail).

Rangoon…………………………………………………………………………………..

……………………………………………………………………………………………..

…………………………………………………………………………………………….

…………………….. Am in cell No. 82- filthy conditions- somebody died last night from dysentery- unable to get any medical treatment or a wash. Guards bashed me up last night. All guards appear…….lot. Cell searched and Ken's wallet and photos taken- I made a complaint and said the photo was a picture of my wife and got it back.

Several prisoners very sick with dysentery, Ken arrives from Maymyo- has recovered from wounds. Has frequent doses of malaria- No Quinine. Was experimented on by the Japs with fever.

Aug. 20: Ken very bad with high fever-unable to get any quinine-Unconscious and rambling in speech-talks of his family-appears to think he is in France. Seems to recognise me at times then unconscious again. I do not think he will live the night. Aug. 21 Ken died-one of the bravest chaps I have seen in this war-buried in Rangoon.

Postcard No. 4:

Buried Ken today in Rangoon. Held short service, but I could not remember much of it, so had to make most of it up. Japs gave us very little time. They are frightened of RAF bombers.

Hope to be out of here by Christmas. 6 have died in the last 12 weeks and many more will die unless we get more food and some medical supplies-No Red Cross. Japs very confident of victory.

Seen below is another gallery of images in relation to this narrative, including a photograph of Kenneth's grave at Rangoon War Cemetery. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

During his short time in Rangoon Jail, Kenneth was held alongside many of his Chindit comrades in Block 6 of the prison. He was given the POW no. 574 and was treated for his wounds and malaria at the make-shift hospital located on the veranda of the cell block building. As mentioned previously, many Chindit POWs had been used by the Japanese as medical guinea-pigs, especially at Maymyo and had been injected with various malarial strains and other diseases. As recorded by Flight-Lieutenant Edmonds, Kenneth died on the 21st August 1943 suffering from severe fever. He was buried at the English Cantonment Cemetery situated to the east of the city, close to the Royal Lakes. After the war was over, all graves at the Cantonment Cemetery were removed and re-interred at the newly constructed Rangoon War Cemetery.

To view Kenneth's details on the CWGC website, please click on the following link:

www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2261442/wyse,-kenneth-renwick/

To read more about the Japanese experiments carried out on Chindit prisoners of war, please click on the following link:

Japanese Experimentation on POW's

To view Kenneth's details on the CWGC website, please click on the following link:

www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2261442/wyse,-kenneth-renwick/

To read more about the Japanese experiments carried out on Chindit prisoners of war, please click on the following link:

Japanese Experimentation on POW's

RAF cap badge circa WW2.

RAF cap badge circa WW2.

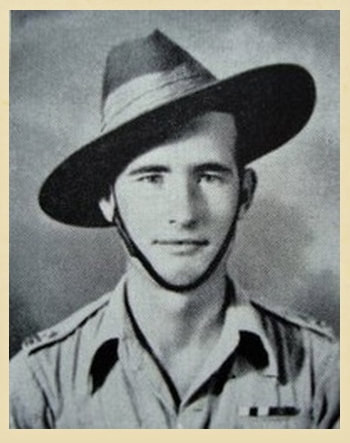

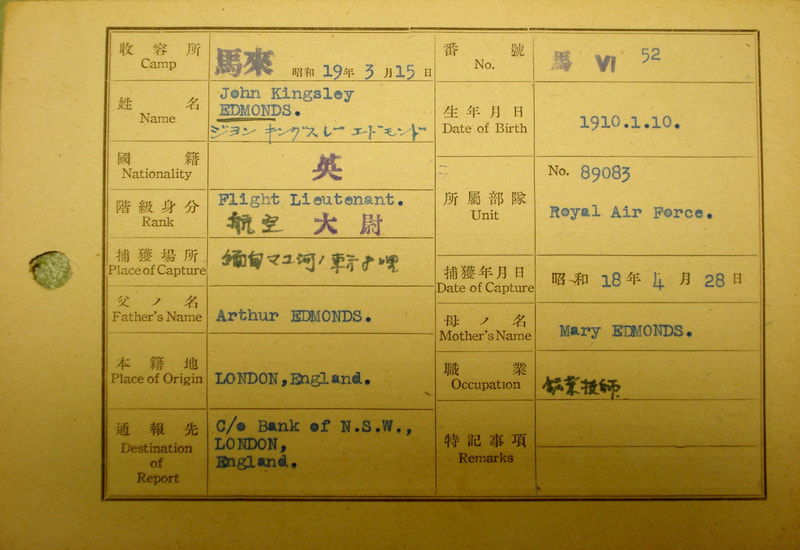

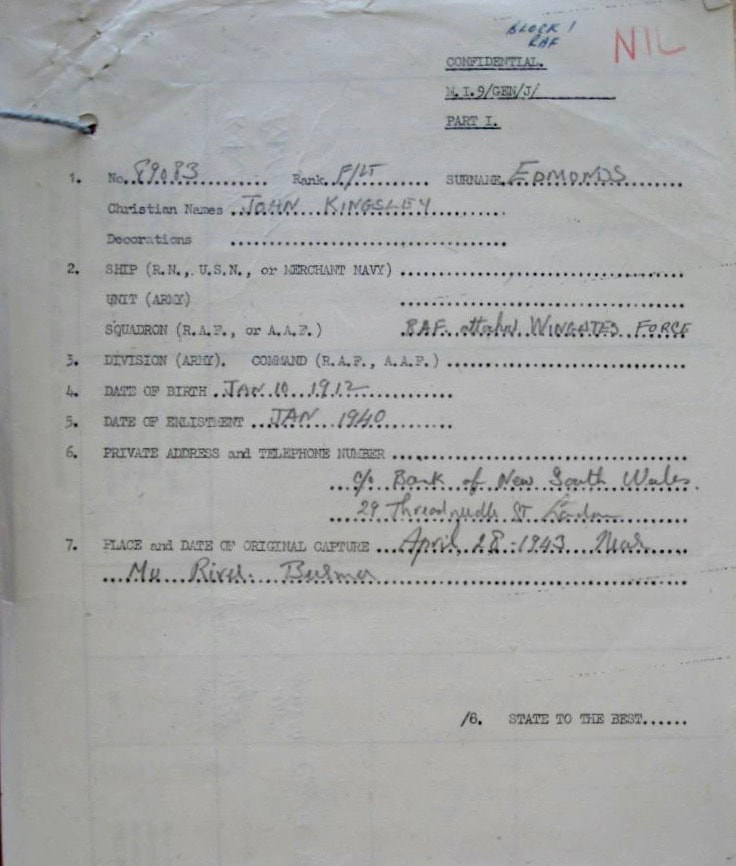

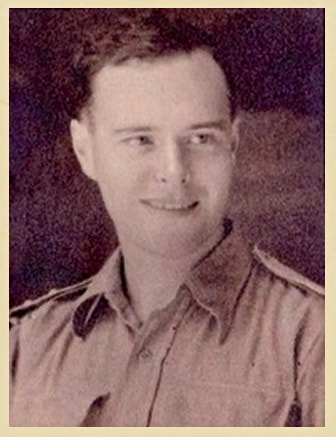

Flight Lieutenant (89083) John Kingsley Edmonds

From the pages of Beyond the Chindwin, by Bernard Fergusson:

At a quarter to six, I was over with Southern Group talking to the Colonel and watching the mules being loaded. An RAF officer was present named Edmonds, he was from New Guinea and a magnificent fighting man with a family feud against the Japanese, which he was burning to avenge.

Sadly, I know very little about John Kingsley Edmonds and what it was that brought him to 77th Brigade in the summer of 1942. Taking the lead from Bernard Fergusson's short quote above, it seems that he had perhaps lost some family members to Japanese aggression earlier in the war. I do know that he was born on the 10th January 1912, possibly in New South Wales, Australia and that he had enlisted into the RAF or RAAF in January 1940. His mother was living in the village of Ditchling, East Sussex during August 1943, from where she made enquiries through the national press in regards his whereabouts, after his disappearance in northern Burma in April that same year.

As with all RAF Liaison personnel on Operation Longcloth, Flight Lieutenant Edmonds would have volunteered for the secret assignment that was to become the first Wingate expedition from his previous posting (probably in India). He was then allocated as senior RAF Liaison Officer to Southern Section Head Quarters, where he would have trained and put together his team, which at some point was to include, Sgt. Kenneth Wyse. In one debrief report after Operation Longcloth was closed in June 1943, he was directly attributed as one of the main contributors in the development of air supply tactics on the expedition, alongside Squadron Leader Cecil Longmore, who was coincidentally also to end up as a prisoner of war.

Apart from the obvious bravery shown by Edmonds in carrying Colonel Alexander to potential safety at the Mu River and his devotion to the health and well being of Kenneth Wyse after their capture on the 28th April 1943, we also know that he displayed his compassionate nature for many other of his Chindit comrades. During the long months of incarceration at Rangoon Jail, Edmonds took great care of many individuals, especially those that had become ill or infirm. Lt. Willie Wilding, another Chindit captured on Operation Longcloth remembered Edmonds as a strong and caring man who worked hard in the make-shift hospital, assisting the medical staff in whatever way he could. He also conducted many of the Chindit funerals at the English Cantonment Cemetery, including performing the burial service for Captain Graham Hosegood, who sadly died in April 1945, just a few short weeks before the jail was liberated. It is also said that John returned to Rangoon in 1946, to take part in giving evidence at the war crimes trials of several of the Japanese guards that had ruled Rangoon Jail with such cruelty during the period 1942-45. For his efforts during WW2, John Edmonds was Mentioned in Despatches (M.I.D.).

It is of course, through his endeavours in seeking out the parents of Sgt. Kenneth Wyse after the war, that we learn most about the good character of John Kingsley Edmonds. It cannot be confirmed, but seems likely that he would have attempted to contact not just Mr. David Wyse back then, but probably the family of Colonel Alexander as well.

From the pages of the Port Glasgow Express newspaper (dated July 1943):

Mr. and Mrs. David Wyse of Barholm, Port Glasgow, whose son, Sgt. Kenneth Wyse (RAF), died in a Japanese camp in Rangoon on the 21st August 1943, have received through a New Guinea, RAF man, Flight Lieutenant J. K. Edmonds, who visited them last weekend with details of the sad end to a promising Air force career. Sgt. Wyse, who was 22 years of age is a former pupil of Greenock High School and was first in Scotland in his examinations at Cranwell, where he studied.

Both men, with an Aberdonian Colonel Alexander, who died of wounds, were with the first Wingate expedition in Burma, when they were captured on the 28th April 1943. Subsequent events were written in diary form by the Australian on the backs of photographs of Sgt. Wyse's father, mother and sister and are now in Mr. Wyse's possession, along with a pocket book. On the day of capture the excerpt reads: Can't walk wounds stiffen. Jap search party only 10 feet away. Chances thin, Ken unconscious with two bullets through stomach and a wound in the hip.

The article then goes on to reproduce much of the diary already transcribed as part of Kenneth Wyse' story above. The newspaper article concludes:

Sgt. Wyse died the next day and of him Flight Lieutenant Edmonds writes: Ken was one of the bravest chaps I have ever met in this war. He was buried in Rangoon and the late General Wingate had recommended him for a commission and decoration.

The New Guinea Airman was released from his POW camp two months ago and paid Mr. Wyse a visit to hand over the photographs. Much sympathy is felt in the town for the parents in the loss of a fine son. Mrs. Wyse has been prominent in the Women's Voluntary Service and Mr. Wyse is well known in sporting and angling circles.

From the pages of Beyond the Chindwin, by Bernard Fergusson:

At a quarter to six, I was over with Southern Group talking to the Colonel and watching the mules being loaded. An RAF officer was present named Edmonds, he was from New Guinea and a magnificent fighting man with a family feud against the Japanese, which he was burning to avenge.

Sadly, I know very little about John Kingsley Edmonds and what it was that brought him to 77th Brigade in the summer of 1942. Taking the lead from Bernard Fergusson's short quote above, it seems that he had perhaps lost some family members to Japanese aggression earlier in the war. I do know that he was born on the 10th January 1912, possibly in New South Wales, Australia and that he had enlisted into the RAF or RAAF in January 1940. His mother was living in the village of Ditchling, East Sussex during August 1943, from where she made enquiries through the national press in regards his whereabouts, after his disappearance in northern Burma in April that same year.

As with all RAF Liaison personnel on Operation Longcloth, Flight Lieutenant Edmonds would have volunteered for the secret assignment that was to become the first Wingate expedition from his previous posting (probably in India). He was then allocated as senior RAF Liaison Officer to Southern Section Head Quarters, where he would have trained and put together his team, which at some point was to include, Sgt. Kenneth Wyse. In one debrief report after Operation Longcloth was closed in June 1943, he was directly attributed as one of the main contributors in the development of air supply tactics on the expedition, alongside Squadron Leader Cecil Longmore, who was coincidentally also to end up as a prisoner of war.

Apart from the obvious bravery shown by Edmonds in carrying Colonel Alexander to potential safety at the Mu River and his devotion to the health and well being of Kenneth Wyse after their capture on the 28th April 1943, we also know that he displayed his compassionate nature for many other of his Chindit comrades. During the long months of incarceration at Rangoon Jail, Edmonds took great care of many individuals, especially those that had become ill or infirm. Lt. Willie Wilding, another Chindit captured on Operation Longcloth remembered Edmonds as a strong and caring man who worked hard in the make-shift hospital, assisting the medical staff in whatever way he could. He also conducted many of the Chindit funerals at the English Cantonment Cemetery, including performing the burial service for Captain Graham Hosegood, who sadly died in April 1945, just a few short weeks before the jail was liberated. It is also said that John returned to Rangoon in 1946, to take part in giving evidence at the war crimes trials of several of the Japanese guards that had ruled Rangoon Jail with such cruelty during the period 1942-45. For his efforts during WW2, John Edmonds was Mentioned in Despatches (M.I.D.).

It is of course, through his endeavours in seeking out the parents of Sgt. Kenneth Wyse after the war, that we learn most about the good character of John Kingsley Edmonds. It cannot be confirmed, but seems likely that he would have attempted to contact not just Mr. David Wyse back then, but probably the family of Colonel Alexander as well.

From the pages of the Port Glasgow Express newspaper (dated July 1943):

Mr. and Mrs. David Wyse of Barholm, Port Glasgow, whose son, Sgt. Kenneth Wyse (RAF), died in a Japanese camp in Rangoon on the 21st August 1943, have received through a New Guinea, RAF man, Flight Lieutenant J. K. Edmonds, who visited them last weekend with details of the sad end to a promising Air force career. Sgt. Wyse, who was 22 years of age is a former pupil of Greenock High School and was first in Scotland in his examinations at Cranwell, where he studied.

Both men, with an Aberdonian Colonel Alexander, who died of wounds, were with the first Wingate expedition in Burma, when they were captured on the 28th April 1943. Subsequent events were written in diary form by the Australian on the backs of photographs of Sgt. Wyse's father, mother and sister and are now in Mr. Wyse's possession, along with a pocket book. On the day of capture the excerpt reads: Can't walk wounds stiffen. Jap search party only 10 feet away. Chances thin, Ken unconscious with two bullets through stomach and a wound in the hip.

The article then goes on to reproduce much of the diary already transcribed as part of Kenneth Wyse' story above. The newspaper article concludes:

Sgt. Wyse died the next day and of him Flight Lieutenant Edmonds writes: Ken was one of the bravest chaps I have ever met in this war. He was buried in Rangoon and the late General Wingate had recommended him for a commission and decoration.

The New Guinea Airman was released from his POW camp two months ago and paid Mr. Wyse a visit to hand over the photographs. Much sympathy is felt in the town for the parents in the loss of a fine son. Mrs. Wyse has been prominent in the Women's Voluntary Service and Mr. Wyse is well known in sporting and angling circles.

John Kingsley Edmonds returned to Australia after the war and sadly passed away on the 29th July 2002. He is buried at Tewantin Cemetery in the town of Noosa, Queensland. Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the narrative above, including John's POW index card and liberation questionnaire. Also shown is a letter written by John in mid-1945 as part of his efforts in finding the family of Kenneth Wyse. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Willie Wilding.

Willie Wilding.

Update 04/12/2020.

From the written memoir of Lieutenant R.A. Wilding, known as Willie to his comrades and Wingate's Cipher Officer on Operation Longcloth:

When I first joined Brigade Head Quarters in India, I met many of the men I would go on to share the trials of the expedition with. Flight-Lieutenant Edmonds, who we all called Joe, was a very tough Australian who had lived in New Guinea before the war. He had done various things to make a living, including capturing wild animals for zoos and prospecting for gold, we became very good friends especially during our time in Rangoon Jail.

At one time in the jail Joe was pretty ill and was determined to die, if he had to, penniless. He spent all the money he had a soon as possible and you could see him limping around the makeshift hospital distributing eggs and cheerots to the sick and dying men. I asked him how he was going to get through the next month without any money. He replied: "By Faith, Hope and Charity, but mostly charity and chiefly yours and Spurlock's (77 Brigade Signals Officer, Lt. Kenneth Spurlock)." This was typical of the man and his humour.

From the written memoir of Lieutenant R.A. Wilding, known as Willie to his comrades and Wingate's Cipher Officer on Operation Longcloth:

When I first joined Brigade Head Quarters in India, I met many of the men I would go on to share the trials of the expedition with. Flight-Lieutenant Edmonds, who we all called Joe, was a very tough Australian who had lived in New Guinea before the war. He had done various things to make a living, including capturing wild animals for zoos and prospecting for gold, we became very good friends especially during our time in Rangoon Jail.

At one time in the jail Joe was pretty ill and was determined to die, if he had to, penniless. He spent all the money he had a soon as possible and you could see him limping around the makeshift hospital distributing eggs and cheerots to the sick and dying men. I asked him how he was going to get through the next month without any money. He replied: "By Faith, Hope and Charity, but mostly charity and chiefly yours and Spurlock's (77 Brigade Signals Officer, Lt. Kenneth Spurlock)." This was typical of the man and his humour.

Update 14/03/2022.

Back in January this year (2022), I was delighted to receive the following email contact from Susie Edmonds:

Hi, I’ve just typed my Great Uncle’s name into a search engine and your site popped up. His name was John Kingsley Edmonds. I had heard vague bits of information about him and that he was a brave man during the war, but didn’t really know much about him. Having read his story on your website I feel very proud that he was a relation of mine. This has all come about because someone quite randomly contacted me with some papers of his back in Australia and it led to me becoming interested in his life. So, I just wanted to pop on here to say thanks for writing some of his story and I’m glad that it could live on in this way. I hope that I can also help in some way to building the story further.

I replied to Susie:

Dear Susie,

Thank you for your email contact via my website. I am so very pleased that you came across the information about your great uncle, John Kingsley Edmonds. As you will have read, he was quite a man and a very brave and loyal friend to the men he served with on the first Chindit expedition.

All of the information I have about John is now up on the website, most especially on the page for Kenneth Wyse. If you can tell me more about John's life from before the war and after, then I would be very honoured to add this to his story as an update. Of course, the icing on the cake for me would be to add a photograph of him to the site at some stage. Thank you again for taking the trouble to make contact and I hope to hear from you presently.

Susie then replied:

Hi Steve, I loved reading about it all and he definitely was a relative to be proud of. I’m not sure how much we know about his early life, but I’ll talk to my Mum as she might know something. Sadly, my Dad died a few months ago and he was the direct descendant to John so may have known a bit more, but I'm afraid that will be lost now. I definitely have a photo of him and have attached a rough scan of it (shown above), but I’ll send a better quality one over when I can. I know my Mum has at least one other as she showed me it the other day. I will be in touch soon, hopefully with some more information. Thanks once again, Susie.

I would like to thank Susie for her contact and for adding the wonderful photograph of John Kingsley Edmonds to these website pages.

Back in January this year (2022), I was delighted to receive the following email contact from Susie Edmonds:

Hi, I’ve just typed my Great Uncle’s name into a search engine and your site popped up. His name was John Kingsley Edmonds. I had heard vague bits of information about him and that he was a brave man during the war, but didn’t really know much about him. Having read his story on your website I feel very proud that he was a relation of mine. This has all come about because someone quite randomly contacted me with some papers of his back in Australia and it led to me becoming interested in his life. So, I just wanted to pop on here to say thanks for writing some of his story and I’m glad that it could live on in this way. I hope that I can also help in some way to building the story further.

I replied to Susie:

Dear Susie,

Thank you for your email contact via my website. I am so very pleased that you came across the information about your great uncle, John Kingsley Edmonds. As you will have read, he was quite a man and a very brave and loyal friend to the men he served with on the first Chindit expedition.

All of the information I have about John is now up on the website, most especially on the page for Kenneth Wyse. If you can tell me more about John's life from before the war and after, then I would be very honoured to add this to his story as an update. Of course, the icing on the cake for me would be to add a photograph of him to the site at some stage. Thank you again for taking the trouble to make contact and I hope to hear from you presently.

Susie then replied:

Hi Steve, I loved reading about it all and he definitely was a relative to be proud of. I’m not sure how much we know about his early life, but I’ll talk to my Mum as she might know something. Sadly, my Dad died a few months ago and he was the direct descendant to John so may have known a bit more, but I'm afraid that will be lost now. I definitely have a photo of him and have attached a rough scan of it (shown above), but I’ll send a better quality one over when I can. I know my Mum has at least one other as she showed me it the other day. I will be in touch soon, hopefully with some more information. Thanks once again, Susie.

I would like to thank Susie for her contact and for adding the wonderful photograph of John Kingsley Edmonds to these website pages.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, September 2019.