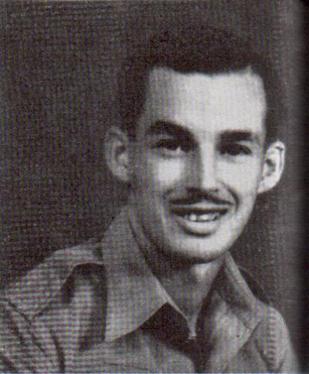

Lance Corporal George Bell

Lance Corporal George Bell.

Most of what I have written is from memory, but some of it I scribbled down after we got back to India and when everything was still fresh in my mind. I have only written about incidents that I was involved in and can vouch for being accurate. Maybe some of the other Chindits will remember other and more exciting stories. When recalling all these stories I must say it brought back some very pleasant memories from that period of my life, but also some rather sad ones too. (George Bell 1995).

George Bell found himself in Northern Group HQ in 1943 and for a time acted as bodyguard to the HQ commander, Lieutenant-Colonel S.A. Cooke formerly of the Lincolnshire Regiment, but now the most senior officer attached to the 13th King's on the operation. George had served previously with the Royal Ulster Rifles, before being posted overseas to India and was originally part of No. 6 Column during Chindit training at Saugor.

Here is what George remembers about the early days of Operation Longcloth:

"All regimental and battalion flashes were removed, and we walked only by night and in silence; secrecy was he order of the day. I do however, remember the glorious sunrises as we moved steadily down the Imphal plain. Our mules arrived after a few days, but there were insufficient Gurkhas to act as muleteers. By the usual Army style of volunteering, 'You, you and you', I was given a mule to look after. As a townie, I hadn't a clue, but after a few errors of judgement initially, I really enjoyed the experience. The mules were obstinate, awkward, occasionally playful, but I soon found that, as with most animals, if you were kind to them they reciprocated. I was rather sorry to lose 'Daisy Bell' when the remaining Gurkhas finally arrived. We stayed at Imphal for a while, and on 7th February we were inspected by General Wavell. My mule did not appreciate the occasion and was very awkward as he approached.

All columns set off, the first hazard being the crossing of the Chindwin River. On the way we crossed the Burmese border, which is to the west of the river. We were told to throw away any unnecessary articles to reduce the load we had to carry. My first error of judgement was discarding one half of my mess tin. It caused me great inconvenience during the next few months. I threw away all of my shaving kit and eventually sported quite a beard, a Victorian style 'mutton-chop' affair. An officer had thrown away a copy of 'For Whom the Bell Tolls' and I read it over the next few days and then slung it.

Our last minute instructions were, 'Do not stray away from the main party. You are in Nagaland and some of the natives are head-hunters!'. Actually, they were very friendly people. The order of the day was 'The River Chindwin is your Jordan. Once over, there is no return except via Rangoon.' I wonder if Wingate really meant that as it seemed a long way to walk.

Most of the lads had no idea what the purpose of the expedition was, other than some vague ideas like: 'To overcome the fallacies that the British troops were inferior to the Japs in jungle fighting', and so on. We were excited about where we were going, but what would happen when we arrived there was a mystery. I am not sure if the top brass even knew."

George Bell found himself in Northern Group HQ in 1943 and for a time acted as bodyguard to the HQ commander, Lieutenant-Colonel S.A. Cooke formerly of the Lincolnshire Regiment, but now the most senior officer attached to the 13th King's on the operation. George had served previously with the Royal Ulster Rifles, before being posted overseas to India and was originally part of No. 6 Column during Chindit training at Saugor.

Here is what George remembers about the early days of Operation Longcloth:

"All regimental and battalion flashes were removed, and we walked only by night and in silence; secrecy was he order of the day. I do however, remember the glorious sunrises as we moved steadily down the Imphal plain. Our mules arrived after a few days, but there were insufficient Gurkhas to act as muleteers. By the usual Army style of volunteering, 'You, you and you', I was given a mule to look after. As a townie, I hadn't a clue, but after a few errors of judgement initially, I really enjoyed the experience. The mules were obstinate, awkward, occasionally playful, but I soon found that, as with most animals, if you were kind to them they reciprocated. I was rather sorry to lose 'Daisy Bell' when the remaining Gurkhas finally arrived. We stayed at Imphal for a while, and on 7th February we were inspected by General Wavell. My mule did not appreciate the occasion and was very awkward as he approached.

All columns set off, the first hazard being the crossing of the Chindwin River. On the way we crossed the Burmese border, which is to the west of the river. We were told to throw away any unnecessary articles to reduce the load we had to carry. My first error of judgement was discarding one half of my mess tin. It caused me great inconvenience during the next few months. I threw away all of my shaving kit and eventually sported quite a beard, a Victorian style 'mutton-chop' affair. An officer had thrown away a copy of 'For Whom the Bell Tolls' and I read it over the next few days and then slung it.

Our last minute instructions were, 'Do not stray away from the main party. You are in Nagaland and some of the natives are head-hunters!'. Actually, they were very friendly people. The order of the day was 'The River Chindwin is your Jordan. Once over, there is no return except via Rangoon.' I wonder if Wingate really meant that as it seemed a long way to walk.

Most of the lads had no idea what the purpose of the expedition was, other than some vague ideas like: 'To overcome the fallacies that the British troops were inferior to the Japs in jungle fighting', and so on. We were excited about where we were going, but what would happen when we arrived there was a mystery. I am not sure if the top brass even knew."

General Wavell inspects the newly formed Chindits at Imphal on the 7th February 1943.

"I eventually crossed the Chindwin late one afternoon on a large raft carrying about ten other men. We had no real problems apart from some awkward mules who insisted on returning to the western shore of the river every time we reached halfway. On guard that first night I was concerned the Japs might attack and realised how noisy the jungle was.

There had been a supply drop before we got there, enough for five days' rations per man. Our first mail drop had gone astray, the rumour was that it had fallen into enemy hands and despite out attempts at secrecy, they already knew the make up of our columns. (In actual fact the Japanese had captured the mail intended for Column 5, and now did know the names of the personnel for that unit).

One day's rations consisted of three packets of hard biscuits, one tin of cheese, milk powder, raisins and nuts, tea bags, one bar of chocolate or acid drops, sugar, 20 cigarettes and one box of matches. Our menu for the next few weeks consisted of one packet of biscuits for each meal, broken up and boiled in the mess tin, mixed with cheese, chocolate or nuts and raisins (this concoction became known as 'chocolate lob'). As we had limited time to prepare these delicacies, my loss of half my mess tin as mentioned earlier, meant that at times I had to forgo the tea. If the Japs were around, fires were not allowed and the biscuits had to eaten cold. They were almost as hard as dog biscuits. In retrospect, this was a serious error in judgement by Wingate. As time went on we began to fade in health, some supply droppings were missed and we began to rely on getting rice from villages to supplement our diet. Bear in mind we used to march 20 miles or more in a day with temperatures of 100 degrees plus, this along with the poor rations took great toll on the men, some of whom were well into their thirties.

In one village a girl complained about the behaviour of one of our lads and we were given a strict warning direct from the top that if anyone interfered with a Burmese girl, Wingate would personally shoot him in front of the assembled villagers. As he went on to point out, our lives were dependent on these villagers being on our side. At one point we thought we were going to see action around the village of Sinlamaung, but the Japanese patrol had left the area before we arrived. We then crossed the Zibyu Taungdan Range by a little known path (Casten's Track, named after the officer who discovered the trail in 1942, Major Bertie Castens) which had been used by British troops the year before during the retreat. We saw many skeletons at the side of the track from people who did not make it out."

There had been a supply drop before we got there, enough for five days' rations per man. Our first mail drop had gone astray, the rumour was that it had fallen into enemy hands and despite out attempts at secrecy, they already knew the make up of our columns. (In actual fact the Japanese had captured the mail intended for Column 5, and now did know the names of the personnel for that unit).

One day's rations consisted of three packets of hard biscuits, one tin of cheese, milk powder, raisins and nuts, tea bags, one bar of chocolate or acid drops, sugar, 20 cigarettes and one box of matches. Our menu for the next few weeks consisted of one packet of biscuits for each meal, broken up and boiled in the mess tin, mixed with cheese, chocolate or nuts and raisins (this concoction became known as 'chocolate lob'). As we had limited time to prepare these delicacies, my loss of half my mess tin as mentioned earlier, meant that at times I had to forgo the tea. If the Japs were around, fires were not allowed and the biscuits had to eaten cold. They were almost as hard as dog biscuits. In retrospect, this was a serious error in judgement by Wingate. As time went on we began to fade in health, some supply droppings were missed and we began to rely on getting rice from villages to supplement our diet. Bear in mind we used to march 20 miles or more in a day with temperatures of 100 degrees plus, this along with the poor rations took great toll on the men, some of whom were well into their thirties.

In one village a girl complained about the behaviour of one of our lads and we were given a strict warning direct from the top that if anyone interfered with a Burmese girl, Wingate would personally shoot him in front of the assembled villagers. As he went on to point out, our lives were dependent on these villagers being on our side. At one point we thought we were going to see action around the village of Sinlamaung, but the Japanese patrol had left the area before we arrived. We then crossed the Zibyu Taungdan Range by a little known path (Casten's Track, named after the officer who discovered the trail in 1942, Major Bertie Castens) which had been used by British troops the year before during the retreat. We saw many skeletons at the side of the track from people who did not make it out."

Lieutenant Colonel S.A. 'Sam' Cooke.

"We had several skirmishes as we eventually crossed the railway and reached the Irrawaddy River. We hid in the hills overlooking Wuntho for five days as Wingate contemplated attacking the Japanese garrison there, but he decided against it. We crossed the Irrawaddy by boat late in the afternoon with the C/O, Lieutenant-Colonel Cooke."

NB. S.A. Cooke was the senior officer commanding the 13th Kings on Operation Longcloth, a former Lincolnshire regiment soldier, he had assumed command of the battalion from the previous, but older C/O, Lieutenant-Colonel W. M. Robinson, who Wingate had deemed too old to take part in the expedition. Cooke went on to become commander of the Arab Legion in the 1950's, this was the regular Army of Transjordan and was trained to a very high standard. The force was used in several military actions against Israel.

George continues:

"At the time several officers still had bedding rolls carried on their chargers. Most of the men by that time had nothing and kipped down on the ground. This began to annoy some of the lads and when we reached the eastern banks of the river the CO's bedding had disappeared. Lieutenant-Colonel Cooke was very annoyed and ordered his batman and me to try and find the bedding roll. The lads told me that it had been thrown into the Irrawaddy because they did not see why he should have such a privilege and they not. I daren't tell the CO.

For some time I had been what can only be described as the CO's bodyguard. On occasions either Wingate or the column commander wished to rendezvous with the CO. I would walk ahead of him down the tracks towards the agreed RV with my rifle cocked, on the assumption that if the Japs pounced on us, I would be expendable, rather than the CO. Luckily that never happened. Remarkably it never crossed my mind either then or later that I might be killed, others might, but me, never! We continued marching eastwards, our casualties were beginning to increase in number and dealing with the sick and wounded became a problem. I recall leaving about 10 men in a village, we all shook hands and tried to make the best of it. We knew that they hadn't a cat in hell's chance of surviving, and what made matters worse was that they knew too. Most of the lads thought it was better to be killed outright than to be badly wounded.

We marched on, but things went from bad to worse and supply drops became less frequent. We crossed the Shweli River and headed northeast, at one stage I believe we were completely lost as we moved through a dry river bed, which I was positive we had walked down the day before. On March 26th we received the news that we were going back to India. 'Thank Goodness' was the general reaction. We received a large ration drop at a place called Baw, but the Japs were waiting for us and many of the lads were killed. An officer who had been instructed to attack the Japs from the far side went in from the wrong side, resulting in several men killed, Wingate demoted him on the spot to Private and transferred him to Column 5."

NB. The officer in question was Captain J.S.F. Coughlan, commander of platoon 17 in Column 8. He reacted well to his punishment and was soon promoted back through the ranks, exiting Burma in 1943 as a Sergeant and reaching battalion Adjutant by the end of the war.

NB. S.A. Cooke was the senior officer commanding the 13th Kings on Operation Longcloth, a former Lincolnshire regiment soldier, he had assumed command of the battalion from the previous, but older C/O, Lieutenant-Colonel W. M. Robinson, who Wingate had deemed too old to take part in the expedition. Cooke went on to become commander of the Arab Legion in the 1950's, this was the regular Army of Transjordan and was trained to a very high standard. The force was used in several military actions against Israel.

George continues:

"At the time several officers still had bedding rolls carried on their chargers. Most of the men by that time had nothing and kipped down on the ground. This began to annoy some of the lads and when we reached the eastern banks of the river the CO's bedding had disappeared. Lieutenant-Colonel Cooke was very annoyed and ordered his batman and me to try and find the bedding roll. The lads told me that it had been thrown into the Irrawaddy because they did not see why he should have such a privilege and they not. I daren't tell the CO.

For some time I had been what can only be described as the CO's bodyguard. On occasions either Wingate or the column commander wished to rendezvous with the CO. I would walk ahead of him down the tracks towards the agreed RV with my rifle cocked, on the assumption that if the Japs pounced on us, I would be expendable, rather than the CO. Luckily that never happened. Remarkably it never crossed my mind either then or later that I might be killed, others might, but me, never! We continued marching eastwards, our casualties were beginning to increase in number and dealing with the sick and wounded became a problem. I recall leaving about 10 men in a village, we all shook hands and tried to make the best of it. We knew that they hadn't a cat in hell's chance of surviving, and what made matters worse was that they knew too. Most of the lads thought it was better to be killed outright than to be badly wounded.

We marched on, but things went from bad to worse and supply drops became less frequent. We crossed the Shweli River and headed northeast, at one stage I believe we were completely lost as we moved through a dry river bed, which I was positive we had walked down the day before. On March 26th we received the news that we were going back to India. 'Thank Goodness' was the general reaction. We received a large ration drop at a place called Baw, but the Japs were waiting for us and many of the lads were killed. An officer who had been instructed to attack the Japs from the far side went in from the wrong side, resulting in several men killed, Wingate demoted him on the spot to Private and transferred him to Column 5."

NB. The officer in question was Captain J.S.F. Coughlan, commander of platoon 17 in Column 8. He reacted well to his punishment and was soon promoted back through the ranks, exiting Burma in 1943 as a Sergeant and reaching battalion Adjutant by the end of the war.

A Chindit Column from 1943 led by a Bren Gunner.

George continues with his story:

"After taking another supply drop, the decision was made to split up into smaller dispersal parties. Some headed for China, while others stayed together and marched due west. Our party under Lieutenant Pearce, about fifty strong, went north-north-west. Before splitting up we shook hands with all our pals in the other groups, several of them we would never see again. Our party included three officers and two Burmese who were in the Burma Rifles and could speak both English and Burmese. They saved our lives, as they were able to enter villages and obtain information about the whereabouts of the Japs. Apart from the one occasion when they got drunk as newts in one village on rice wine.

After leaving the other groups we made for a small village on the Irrawaddy, only to find as we arrived there that the village had been moved to the other bank a few years before. It was then that we realised that our maps had been drawn up in 1912 and were extremely out of date. We made off for another village further towards the north, but got bogged down in thick jungle and so decided to halt and sleep for a few hours. This turned out to be a stroke of good luck, as it transpired that a Jap patrol had spent the night in the village and had only just moved out. From that moment on I always felt that someone above was looking out for us.

As soon as it was dark we started to cross over in a boat with a villager rowing, the water came right up to the top of the sides, I couldn't swim and so was pleased to reach the other side still afloat. Throughout the night the boat crossed and re-crossed the river until everyone was over. By that time we had no way of contacting our air base and had to rely on local villages for food, boiled rice with no salt for breakfast, lunch and dinner! We had also become lousy and our clothes were disgusting. Leeches became a real problem, they got everywhere and I mean everywhere. We were told to use a lighted cigarette to burn them off, but this advice presumed we had cigarettes, which by then we did not. At one stage the heavy smokers amongst our group bought local tobacco from a village and used one of the lads bible for roll-up papers.

We marched sometimes 20 miles in a day, re-crossing the railway and two more minor rivers. One day we came across a Burmese man who could speak English, his story did not ring true to us and so we kept him with us under guard. After collecting more rice in the next village the headman warned us that this man had recently been in the company of a Jap patrol. It was decide that it was too dangerous to let him go and that he should be shot. My section took him away from the main group and one of the Burma Rifle soldiers shot him through the head. This left us with the feeling of being judge, jury and executioner.

We slogged on for a few more days, by which time our food supplies had completely run out. I brewed up with a tea bag that must have been used at least twenty times before. Around midday we were walking along a dried-up river bed when we saw some parachutes caught up in a group of trees. We approached them carefully concerned it might be a Jap ambush or booby trap, but it was a definite ration dropping, presumably for another of our parties. The packs gave us eight days rations per man, exactly eight days later we were in a small village when a British plane came over and spotted us on the ground. They dropped a message canister asking if we needed supplies, we answered them using cut parachute strips to mark out our numbers and needs. We waited for almost two days hoping they would return, but reluctantly we moved on, worried about the dangers of staying put in one place for too long.

Not long after that incident two of our lads whose feet were in an awful state needed time to rest and bathe their feet in a stream. The order was given to move off, but the two men said they wanted to remain for a short while longer and would attempt to catch us up later. They never returned to the main group and we heard later that they had been killed by the Japanese."

NB: The two men were Pte. John Brennan and Pte. Hyman Farber, both from Manchester and recorded as lost on the 8th May 1943. Their individual stories can be found on this website by entering their names into the search box found in the top right hand corner of any page.

George Bell's narrative continues:

"We pushed on again and eventually reached the Chindwin River. Some Burmese boatmen ferried us across near Tamanthi which was occupied by the enemy at that time. We marched quickly westward and came to an Assam Rifles outpost. Here we shaved off our beards which showed us how thin we had become, losing two or three stones in weight. After a few days rest in the camp we set off again, this time knowing we were safe. Remarkably this seemed to make matters worse for some of the men. Our incentive to keep going was no longer there, physiologically we were in a poorer state and many of the lads health began to go down hill. Eventually we hit the road and were transported to the hospital at Kohima. It was here that Lieutenant Pickering and Private Sullivan sadly died, after all we had been through it was heartbreaking."

(Lieutenant John Francis Pickering died on 15th June 1943 from the operations exertions combined with malaria. Pte. 5119801 George Sullivan died on 22nd June 1943 in Kohima Hospital presumably totally exhausted from his time in Burma that year).

George Bell concludes his story:

"When we came back from Burma we were treated as heroes by the other soldiers we met. But this hero-worship soon faded. We were brought back down to earth with a bump when we went to Bombay on a month’s leave. When we tried to enter the main hotel in Bombay at the time, The Raj, we were told quite clearly it was for officers only. Other hotels were slightly more forgiving but still told us to use the back entrance, to leave by 8pm and that we must not go into the main bar area at any time. In the end we decided to stay at the Y.M.C.A. As Kipling might have said: It was ever thus!

Looking back at the age of 77, I am glad I was in the 1943 expedition. It taught me self-confidence, not to take ordinary things in life for granted, and the enjoyment of a comradeship which is sadly lacking in our society today."

Below are photographs of the two grave memorials for John Francis Pickering and George Sullivan, both men were buried at Kohima War Cemetery after the war. Photographs courtesy of the website: asiawargraves.com

"After taking another supply drop, the decision was made to split up into smaller dispersal parties. Some headed for China, while others stayed together and marched due west. Our party under Lieutenant Pearce, about fifty strong, went north-north-west. Before splitting up we shook hands with all our pals in the other groups, several of them we would never see again. Our party included three officers and two Burmese who were in the Burma Rifles and could speak both English and Burmese. They saved our lives, as they were able to enter villages and obtain information about the whereabouts of the Japs. Apart from the one occasion when they got drunk as newts in one village on rice wine.

After leaving the other groups we made for a small village on the Irrawaddy, only to find as we arrived there that the village had been moved to the other bank a few years before. It was then that we realised that our maps had been drawn up in 1912 and were extremely out of date. We made off for another village further towards the north, but got bogged down in thick jungle and so decided to halt and sleep for a few hours. This turned out to be a stroke of good luck, as it transpired that a Jap patrol had spent the night in the village and had only just moved out. From that moment on I always felt that someone above was looking out for us.

As soon as it was dark we started to cross over in a boat with a villager rowing, the water came right up to the top of the sides, I couldn't swim and so was pleased to reach the other side still afloat. Throughout the night the boat crossed and re-crossed the river until everyone was over. By that time we had no way of contacting our air base and had to rely on local villages for food, boiled rice with no salt for breakfast, lunch and dinner! We had also become lousy and our clothes were disgusting. Leeches became a real problem, they got everywhere and I mean everywhere. We were told to use a lighted cigarette to burn them off, but this advice presumed we had cigarettes, which by then we did not. At one stage the heavy smokers amongst our group bought local tobacco from a village and used one of the lads bible for roll-up papers.

We marched sometimes 20 miles in a day, re-crossing the railway and two more minor rivers. One day we came across a Burmese man who could speak English, his story did not ring true to us and so we kept him with us under guard. After collecting more rice in the next village the headman warned us that this man had recently been in the company of a Jap patrol. It was decide that it was too dangerous to let him go and that he should be shot. My section took him away from the main group and one of the Burma Rifle soldiers shot him through the head. This left us with the feeling of being judge, jury and executioner.

We slogged on for a few more days, by which time our food supplies had completely run out. I brewed up with a tea bag that must have been used at least twenty times before. Around midday we were walking along a dried-up river bed when we saw some parachutes caught up in a group of trees. We approached them carefully concerned it might be a Jap ambush or booby trap, but it was a definite ration dropping, presumably for another of our parties. The packs gave us eight days rations per man, exactly eight days later we were in a small village when a British plane came over and spotted us on the ground. They dropped a message canister asking if we needed supplies, we answered them using cut parachute strips to mark out our numbers and needs. We waited for almost two days hoping they would return, but reluctantly we moved on, worried about the dangers of staying put in one place for too long.

Not long after that incident two of our lads whose feet were in an awful state needed time to rest and bathe their feet in a stream. The order was given to move off, but the two men said they wanted to remain for a short while longer and would attempt to catch us up later. They never returned to the main group and we heard later that they had been killed by the Japanese."

NB: The two men were Pte. John Brennan and Pte. Hyman Farber, both from Manchester and recorded as lost on the 8th May 1943. Their individual stories can be found on this website by entering their names into the search box found in the top right hand corner of any page.

George Bell's narrative continues:

"We pushed on again and eventually reached the Chindwin River. Some Burmese boatmen ferried us across near Tamanthi which was occupied by the enemy at that time. We marched quickly westward and came to an Assam Rifles outpost. Here we shaved off our beards which showed us how thin we had become, losing two or three stones in weight. After a few days rest in the camp we set off again, this time knowing we were safe. Remarkably this seemed to make matters worse for some of the men. Our incentive to keep going was no longer there, physiologically we were in a poorer state and many of the lads health began to go down hill. Eventually we hit the road and were transported to the hospital at Kohima. It was here that Lieutenant Pickering and Private Sullivan sadly died, after all we had been through it was heartbreaking."

(Lieutenant John Francis Pickering died on 15th June 1943 from the operations exertions combined with malaria. Pte. 5119801 George Sullivan died on 22nd June 1943 in Kohima Hospital presumably totally exhausted from his time in Burma that year).

George Bell concludes his story:

"When we came back from Burma we were treated as heroes by the other soldiers we met. But this hero-worship soon faded. We were brought back down to earth with a bump when we went to Bombay on a month’s leave. When we tried to enter the main hotel in Bombay at the time, The Raj, we were told quite clearly it was for officers only. Other hotels were slightly more forgiving but still told us to use the back entrance, to leave by 8pm and that we must not go into the main bar area at any time. In the end we decided to stay at the Y.M.C.A. As Kipling might have said: It was ever thus!

Looking back at the age of 77, I am glad I was in the 1943 expedition. It taught me self-confidence, not to take ordinary things in life for granted, and the enjoyment of a comradeship which is sadly lacking in our society today."

Below are photographs of the two grave memorials for John Francis Pickering and George Sullivan, both men were buried at Kohima War Cemetery after the war. Photographs courtesy of the website: asiawargraves.com

Copyright © Steve Fogden and Phil Chinnery 2011/2012.