Captain Joseph Sidney Francis Coughlan

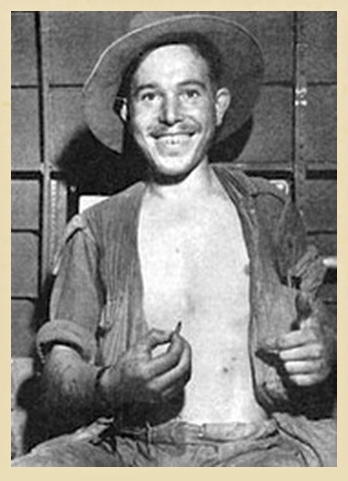

Lt. Joseph Coughlan, Colchester 1941.

Lt. Joseph Coughlan, Colchester 1941.

In the aftermath of the supply drop at the village of Baw on the 24th March, Bernard Fergusson, fresh from an officers conference in the presence of Brigadier Wingate, considered his new orders and the well-being of his own men from 5 Column. On the whole he was satisfied with their overall performance. There was however, one area of concern. From the pages of Bernard Fergusson's book, Beyond the Chindwin:

An officer whom I will call Donnelly, had been sent before the supply drop at Baw to seal off part of the area from possible enemy interference. He had failed to reach his allotted position by nightfall, and had bivouacked short of it. When he moved on at dawn, he found the Japs already in the village between him and the supply dropping area. He was adjudged guilty of having failed to carry out his orders through negligence and summarily reduced to the ranks by the Brigadier.

It was obviously impossible for him to stay in his own column, where he had been a Captain; so he came to me as a Private soldier. I did not know him well, having come so recently to the Brigade; but others, like Bill Edge and Tommy Roberts and Alec MacDonald, had served in the same battalion with him for three years and knew him very well indeed.

I talked to him for five minutes and to my relief found that he had taken this shattering blow most creditably, though he felt he had been hardly done by. I brought him into Column Headquarters, ostensibly as an intelligence private; and warned him that he was to be treated as a private soldier in every way. I mention this incident for several reasons, but chiefly because it shows how one had, in the matter of discipline as in many other matters, to make decisions not normal in the Army; and also because I want to pay tribute to Donnelly, both for the fashion in which he took his degradation and for his extreme usefulness to me in the weeks that followed.

After publishing his book just before war's end in April 1945, Bernard Fergusson by using the pseudonym of Donnelly, was clearly attempting to keep the true identity of the demoted officer from the public domain. With the full passage of time and in the light of a more rounded view of the circumstances of this incident, I feel that there is no real reason not reveal that the officer in question was Captain Joseph Sidney Francis Coughlan of the King's Regiment.

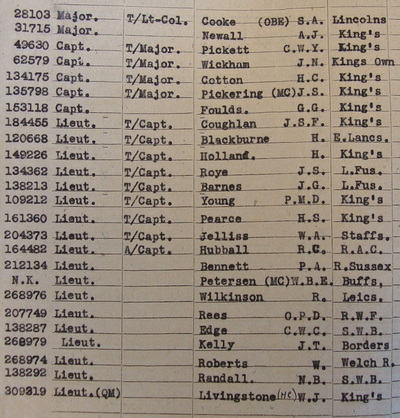

Joseph was born in 1912 and worked in civilian life for the Liverpool Department Store Lewis'. He enlisted in to the British Army in early 1941, receiving an Emergency Commission as an Officer Cadet on the 26th April the same year. This was confirmed by the London Gazette on the 9th May and 2nd Lieutenant 184455 J.S.F. Coughlan was posted over to the King's Regiment, joining the 13th Battalion at their temporary encampment in Abberton, near Colchester in Essex on the 21st May 1941. The battalion had already spent a number of months in the south of England, performing coastal defence duties mostly in the counties of Essex and Suffolk.

The battalion War diary for 1941, penned by the then Adjutant Kenneth Gilkes, rather underwhelmingly announced the arrival of Joseph Couglan on the 21st May: 2nd Lieutenant Coughlan and 2nd Lieutenant Whatmough joined from the I.T.C. and are posted to D and B Coys respectively.

By the end of the year and with the confirmation of an overseas posting, the battalion moved up to Blackburn and awaited further orders. On the 8th December 1941, the 13th King's boarded the troopship Oronsay at Liverpool Docks and their journey into Wingate's arms began. During the period of Chindit training Joseph Coughlan, being an original officer with D' Company from the 13th Battalion, was posted to Chindit Column No. 8 under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott. His original placement was in 8 Column Head Quarters, where he performed the role of Intelligence Officer. Once inside Burma on Operation Longcloth, Joseph was handed command of 17 Platoon, taking over from Lt. Campbell-Paterson on the 27th February 1943 and with Lt. David Rowland, formerly of the Royal Sussex Regiment appointed as his junior officer.

An officer whom I will call Donnelly, had been sent before the supply drop at Baw to seal off part of the area from possible enemy interference. He had failed to reach his allotted position by nightfall, and had bivouacked short of it. When he moved on at dawn, he found the Japs already in the village between him and the supply dropping area. He was adjudged guilty of having failed to carry out his orders through negligence and summarily reduced to the ranks by the Brigadier.

It was obviously impossible for him to stay in his own column, where he had been a Captain; so he came to me as a Private soldier. I did not know him well, having come so recently to the Brigade; but others, like Bill Edge and Tommy Roberts and Alec MacDonald, had served in the same battalion with him for three years and knew him very well indeed.

I talked to him for five minutes and to my relief found that he had taken this shattering blow most creditably, though he felt he had been hardly done by. I brought him into Column Headquarters, ostensibly as an intelligence private; and warned him that he was to be treated as a private soldier in every way. I mention this incident for several reasons, but chiefly because it shows how one had, in the matter of discipline as in many other matters, to make decisions not normal in the Army; and also because I want to pay tribute to Donnelly, both for the fashion in which he took his degradation and for his extreme usefulness to me in the weeks that followed.

After publishing his book just before war's end in April 1945, Bernard Fergusson by using the pseudonym of Donnelly, was clearly attempting to keep the true identity of the demoted officer from the public domain. With the full passage of time and in the light of a more rounded view of the circumstances of this incident, I feel that there is no real reason not reveal that the officer in question was Captain Joseph Sidney Francis Coughlan of the King's Regiment.

Joseph was born in 1912 and worked in civilian life for the Liverpool Department Store Lewis'. He enlisted in to the British Army in early 1941, receiving an Emergency Commission as an Officer Cadet on the 26th April the same year. This was confirmed by the London Gazette on the 9th May and 2nd Lieutenant 184455 J.S.F. Coughlan was posted over to the King's Regiment, joining the 13th Battalion at their temporary encampment in Abberton, near Colchester in Essex on the 21st May 1941. The battalion had already spent a number of months in the south of England, performing coastal defence duties mostly in the counties of Essex and Suffolk.

The battalion War diary for 1941, penned by the then Adjutant Kenneth Gilkes, rather underwhelmingly announced the arrival of Joseph Couglan on the 21st May: 2nd Lieutenant Coughlan and 2nd Lieutenant Whatmough joined from the I.T.C. and are posted to D and B Coys respectively.

By the end of the year and with the confirmation of an overseas posting, the battalion moved up to Blackburn and awaited further orders. On the 8th December 1941, the 13th King's boarded the troopship Oronsay at Liverpool Docks and their journey into Wingate's arms began. During the period of Chindit training Joseph Coughlan, being an original officer with D' Company from the 13th Battalion, was posted to Chindit Column No. 8 under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott. His original placement was in 8 Column Head Quarters, where he performed the role of Intelligence Officer. Once inside Burma on Operation Longcloth, Joseph was handed command of 17 Platoon, taking over from Lt. Campbell-Paterson on the 27th February 1943 and with Lt. David Rowland, formerly of the Royal Sussex Regiment appointed as his junior officer.

As already mentioned, Captain Coughlan was deemed to have failed in his duty at the village of Baw and was downgraded by Wingate to the rank of Private. In the interests of fairplay and hopefully without any prejudice, here are several different witness accounts of the incident at Baw, which resulted in Joseph Coughlan's demotion and enforced move over to 5 Column.

Firstly, from Coughlan's platoon Sergeant, Tony Aubrey:

The supply drop at Baw was planned for the 23/24 of March and was to be an extremely large affair, re-supplying around 1300 men from Northern Section. Wingate and his column commanders surveyed maps of the area and chose the drop zone, a succession of dry paddy fields on the outskirts of the village; orders were given for two units to secure the main road leading in and out of the village, one of the road blocks was to be manned by my platoon.

We set off to secure the tracks to the east of the village and were supposed to be in place before first light the following morning. We encountered some dense bamboo jungle during the journey to the agreed location and in the end Captain Coughlan called a halt to proceedings and told us to bed down for a few hours until there was enough light to complete the march in comfort. This decision would prove costly. At first light the platoon pushed on, but immediately we ran into Japanese sentries, our Burma Rifleman shot one of the enemy; disastrously this brought out the entire Japanese garrison from the village and all element of surprise was lost. We were soon pinned down by Japanese mortar fire and snipers in the nearby trees took pot shots at us as we scrambled for cover.

We took up a defensive position on the crest of a small rise on the edge of the woodland. Visibility was barely 10 yards forwards as the enemy opened fire on us. Our unit soon suffered casualties, Pte. Birch was killed, with no fewer than 17 bullets finding him out. Lambert was shot in the chest, Yates in the hand and shoulder and Suddery received a bullet which went through his right bicep, punctured his ribs and exited through his stomach. In spite of his wounds Suddery continued to fire his Bren from the hip as we attempted to retreat into the woods.

The men of 17 Platoon found themselves pinned down by the enemy mortar and machine gun fire and for quite a time were cut adrift from the rest of the Chindit Brigade. As the battle at Baw grew in its intensity, it would fall to Captain Erik Petersen, a Danish officer from 7 Column to extricate 17 Platoon from their predicament. From the book Burma Peter, by Knud Rasmussen, comes this paraphrased account of the situation at Baw:

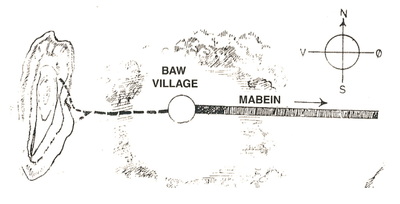

On the 22nd of March, Wingate called the various columns in to bivouac on a hillside to the west of a village called Baw. It was decided to call rear base and order the largest supply drop yet. A plan was laid down to secure the local paths and tracks against enemy interference, especially the road to the east of the village which led to the town of Mabein, where the Japanese had a large garrison.

Wingate gave the task of securing the Mabien Road to Captain Coughlan of 8 Column, whilst platoons from 7 Column including Petersen's were placed to secure the drop zone area. Unfortunately, having to move through more dense jungle than anticipated, Coughlan's party failed to secure the road before morning and stumbled into a Japanese patrol. The enemy opened fire on the ailing platoon and they were forced back to the north. Petersen and Gilkes' men soon came under enemy fire themselves and the supply drop zone seemed compromised and would surely have to be abandoned. Captain Petersen drove his men forward and successfully cleared the Japanese from his sector. He then encountered a soldier from Coughlan's Platoon who had made it through to the nearby First Aid Station.

Petersen recalled:

I came across some wounded men from the force that was in battle at the village. An officer among them had a message from Captain Coughlan, asking if I would send reinforcements to him as he was hard pressed by the enemy. He had been thrown out of the village by the Japanese and was now in a difficult position in the jungle north of this and in a fierce firefight with the enemy. At first, I could see no reason to send reinforcements, due to the hopeless position he found himself in.

I decided to send a patrol up to him and suggest that he retreated back to our position instead. Shortly afterwards, Coughlan, who was slightly wounded, came back to me and said that it was impossible to disengage his unit without suffering major losses, as the terrain was unfavourable and the distance to the Japanese position was very short. I decided to attack the enemy on his flank with my right front platoon supported by our mortars. I explained my plan to Captain Coughlan, with which he seemed satisfied and he went back to his unit.

Captain Petersen, in the company of Lt. Pearce and Lt. Chambers used his mortar section to cover his advance and employed a flanking manoeuvre led by Lieutenant Jelliss on the Japanese positions. He then had his Bren gun team concentrate their fire on the tree tops where enemy snipers were positioned, eventually Captain Coughlan's platoon managed to escape their predicament and came through Petersen's position to safety.

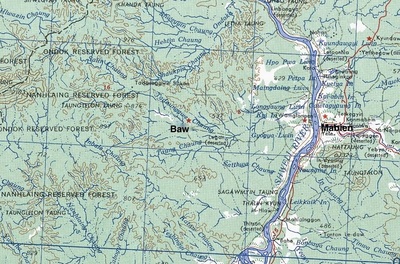

Seen below are some images in relation to this story, including two maps of the area around the village of Baw. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Firstly, from Coughlan's platoon Sergeant, Tony Aubrey:

The supply drop at Baw was planned for the 23/24 of March and was to be an extremely large affair, re-supplying around 1300 men from Northern Section. Wingate and his column commanders surveyed maps of the area and chose the drop zone, a succession of dry paddy fields on the outskirts of the village; orders were given for two units to secure the main road leading in and out of the village, one of the road blocks was to be manned by my platoon.

We set off to secure the tracks to the east of the village and were supposed to be in place before first light the following morning. We encountered some dense bamboo jungle during the journey to the agreed location and in the end Captain Coughlan called a halt to proceedings and told us to bed down for a few hours until there was enough light to complete the march in comfort. This decision would prove costly. At first light the platoon pushed on, but immediately we ran into Japanese sentries, our Burma Rifleman shot one of the enemy; disastrously this brought out the entire Japanese garrison from the village and all element of surprise was lost. We were soon pinned down by Japanese mortar fire and snipers in the nearby trees took pot shots at us as we scrambled for cover.

We took up a defensive position on the crest of a small rise on the edge of the woodland. Visibility was barely 10 yards forwards as the enemy opened fire on us. Our unit soon suffered casualties, Pte. Birch was killed, with no fewer than 17 bullets finding him out. Lambert was shot in the chest, Yates in the hand and shoulder and Suddery received a bullet which went through his right bicep, punctured his ribs and exited through his stomach. In spite of his wounds Suddery continued to fire his Bren from the hip as we attempted to retreat into the woods.

The men of 17 Platoon found themselves pinned down by the enemy mortar and machine gun fire and for quite a time were cut adrift from the rest of the Chindit Brigade. As the battle at Baw grew in its intensity, it would fall to Captain Erik Petersen, a Danish officer from 7 Column to extricate 17 Platoon from their predicament. From the book Burma Peter, by Knud Rasmussen, comes this paraphrased account of the situation at Baw:

On the 22nd of March, Wingate called the various columns in to bivouac on a hillside to the west of a village called Baw. It was decided to call rear base and order the largest supply drop yet. A plan was laid down to secure the local paths and tracks against enemy interference, especially the road to the east of the village which led to the town of Mabein, where the Japanese had a large garrison.

Wingate gave the task of securing the Mabien Road to Captain Coughlan of 8 Column, whilst platoons from 7 Column including Petersen's were placed to secure the drop zone area. Unfortunately, having to move through more dense jungle than anticipated, Coughlan's party failed to secure the road before morning and stumbled into a Japanese patrol. The enemy opened fire on the ailing platoon and they were forced back to the north. Petersen and Gilkes' men soon came under enemy fire themselves and the supply drop zone seemed compromised and would surely have to be abandoned. Captain Petersen drove his men forward and successfully cleared the Japanese from his sector. He then encountered a soldier from Coughlan's Platoon who had made it through to the nearby First Aid Station.

Petersen recalled:

I came across some wounded men from the force that was in battle at the village. An officer among them had a message from Captain Coughlan, asking if I would send reinforcements to him as he was hard pressed by the enemy. He had been thrown out of the village by the Japanese and was now in a difficult position in the jungle north of this and in a fierce firefight with the enemy. At first, I could see no reason to send reinforcements, due to the hopeless position he found himself in.

I decided to send a patrol up to him and suggest that he retreated back to our position instead. Shortly afterwards, Coughlan, who was slightly wounded, came back to me and said that it was impossible to disengage his unit without suffering major losses, as the terrain was unfavourable and the distance to the Japanese position was very short. I decided to attack the enemy on his flank with my right front platoon supported by our mortars. I explained my plan to Captain Coughlan, with which he seemed satisfied and he went back to his unit.

Captain Petersen, in the company of Lt. Pearce and Lt. Chambers used his mortar section to cover his advance and employed a flanking manoeuvre led by Lieutenant Jelliss on the Japanese positions. He then had his Bren gun team concentrate their fire on the tree tops where enemy snipers were positioned, eventually Captain Coughlan's platoon managed to escape their predicament and came through Petersen's position to safety.

Seen below are some images in relation to this story, including two maps of the area around the village of Baw. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

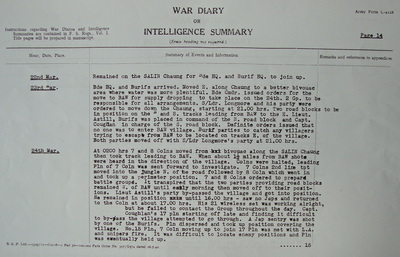

The next version of events comes from the book, Wingate's Lost Brigade by Phil Chinnery, and refers to the official account of the incident at Baw, as found in the pages of 8 Column's War diary (shown in the gallery above):

On 23rd March the Brigadier ordered the group to move toward the village of Baw for a large SD (Supply drop). Two road blocks were to be set up on the tracks leading north and south of the village. Lieutenant Astell of the Burma Rifles to set the northern block and Captain Coughlan the southern block. Coughlan's platoon started off late and did not secure their block until first light. They had to go through the village itself where they were contacted by the Japanese. Tied down by enemy sniper fire and mortars the platoon became isolated from the main body. It took several hours of fierce fighting to extricate Coughlan from his position and relieve his unit. Good work here from Platoon 15, Column 7, led by Captain Petersen. The supply drop continued, but enemy interference hindered proceedings greatly.

Another officer from the King's Regiment on Operation Longcloth, Captain Leslie Cottrell of 7 Column, had known Joseph Coughlan since the 13th Battalion's coastal defence duties in early 1941. He remembered the incident at Baw in his personal memoir, written on his return to England after the war:

On the 23/24th March, the Brigadier ordered 7 and 8 Columns to attack a village, in which it was known there were Japanese soldiers. So that these soldiers could not escape from the village when the attack went in, Captain Joe Coughlan of 8 Column, was instructed to take a section of men and put a block on the only track leading out of the village, on the opposite side from which the attack would go in. On no account were the Japanese to learn of the presence of Joe and his men.

Unfortunately, the ambush party encountered on the track, a lone Japanese sentry who, about to shoot a member of Joe's party, was himself shot dead. The Brigadier was furious at this loss of surprise and claiming that Joe had disobeyed his orders, demoted him on the spot to the rank of Private. A few days later, his new column commander (Fergusson) promoted him to the rank of Sergeant. Back in India, the Brigadier made him up to Captain again.

The final contribution to this thread of statements in relation to Captain Joseph Coughlan, comes from Pte. Frank Holland of the 13th King's and another member of 8 Column on Operation Longcloth. In May 1943, Frank was back in India and recuperating from his exertions on the Chindit expedition whilst in hospital at Imphal. He remembered:

In hospital we were given all the food we could eat. I took on the cooking as it was boring doing nothing. Meals were quite a social gathering. Breakfast as and when anyone arrived. Sometimes we cooked in the middle of the night as various small parties arrived. One day Joe Coughlan walked in, he was a Captain in my Column, but was brought down to a Private by Wingate for getting fourteen of his patrol killed in an ambush, not his fault just bad maps. He was transferred to 5 Column where Fergusson made him a Sergeant. Much later he became our Adjutant and his rank of Captain was restored.

I think that it is Frank Holland's almost casual remark; not his fault just bad maps, that for me, sums up the general sentiment towards Joseph Coughlan. All of the above statements and memories of the incident at Baw, firstly understand and recognise the failure of 17 Platoon to achieve their initial objective. This is then followed, with the possible exception of Captain Petersen's account, by an empathetic appreciation by each writer of the difficulties and hazards of moving through thick-set and uncharted Burmese jungle. There is also a feeling generated in each report that Wingate had over-reacted in demoting Coughlan in such a speedy and public manner and that Captain Coughlan had tried gainfully to rectify his mistake and extricate his men as quickly as possible.

I will leave the final word, as I often do on these website pages, to Bernard Fergusson. Once again from the pages of his book Beyond the Chindwin:

This quote is taken from the period in early April 1943, when 5 Column were approaching the fast flowing Shweli River in search of a suitable crossing point.

I had come to the conclusion that to keep Donnelly as a private soldier was a waste of time. An officer by instinct, experience and training, he could not be usefully employed as he was; and although we had a high proportion of officers, nine out of the seventy-four in our group, three were wounded, and another would in any case be handy.

So I promoted him to Sergeant ; and it is a tribute to the spirit of the men of the column as much as to himself, when I say that this interesting appointment was universally popular. One manifestation of this was when two men came up and said shyly: "Excuse me, sir, but we just want to say 'ow all of us in the column is delighted at Mr. Donnelly being made a Sergeant." Long afterwards Donnelly told me that in spite of every protest on his part, all the troops had insisted on calling him " Mr." throughout his week as a private soldier.

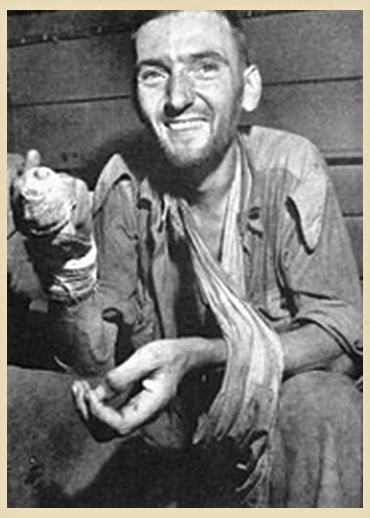

Seen below are some more images in relation to this story, including some of the men from 17 Platoon who survived their time on the first Chindit expedition. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

On 23rd March the Brigadier ordered the group to move toward the village of Baw for a large SD (Supply drop). Two road blocks were to be set up on the tracks leading north and south of the village. Lieutenant Astell of the Burma Rifles to set the northern block and Captain Coughlan the southern block. Coughlan's platoon started off late and did not secure their block until first light. They had to go through the village itself where they were contacted by the Japanese. Tied down by enemy sniper fire and mortars the platoon became isolated from the main body. It took several hours of fierce fighting to extricate Coughlan from his position and relieve his unit. Good work here from Platoon 15, Column 7, led by Captain Petersen. The supply drop continued, but enemy interference hindered proceedings greatly.

Another officer from the King's Regiment on Operation Longcloth, Captain Leslie Cottrell of 7 Column, had known Joseph Coughlan since the 13th Battalion's coastal defence duties in early 1941. He remembered the incident at Baw in his personal memoir, written on his return to England after the war:

On the 23/24th March, the Brigadier ordered 7 and 8 Columns to attack a village, in which it was known there were Japanese soldiers. So that these soldiers could not escape from the village when the attack went in, Captain Joe Coughlan of 8 Column, was instructed to take a section of men and put a block on the only track leading out of the village, on the opposite side from which the attack would go in. On no account were the Japanese to learn of the presence of Joe and his men.

Unfortunately, the ambush party encountered on the track, a lone Japanese sentry who, about to shoot a member of Joe's party, was himself shot dead. The Brigadier was furious at this loss of surprise and claiming that Joe had disobeyed his orders, demoted him on the spot to the rank of Private. A few days later, his new column commander (Fergusson) promoted him to the rank of Sergeant. Back in India, the Brigadier made him up to Captain again.

The final contribution to this thread of statements in relation to Captain Joseph Coughlan, comes from Pte. Frank Holland of the 13th King's and another member of 8 Column on Operation Longcloth. In May 1943, Frank was back in India and recuperating from his exertions on the Chindit expedition whilst in hospital at Imphal. He remembered:

In hospital we were given all the food we could eat. I took on the cooking as it was boring doing nothing. Meals were quite a social gathering. Breakfast as and when anyone arrived. Sometimes we cooked in the middle of the night as various small parties arrived. One day Joe Coughlan walked in, he was a Captain in my Column, but was brought down to a Private by Wingate for getting fourteen of his patrol killed in an ambush, not his fault just bad maps. He was transferred to 5 Column where Fergusson made him a Sergeant. Much later he became our Adjutant and his rank of Captain was restored.

I think that it is Frank Holland's almost casual remark; not his fault just bad maps, that for me, sums up the general sentiment towards Joseph Coughlan. All of the above statements and memories of the incident at Baw, firstly understand and recognise the failure of 17 Platoon to achieve their initial objective. This is then followed, with the possible exception of Captain Petersen's account, by an empathetic appreciation by each writer of the difficulties and hazards of moving through thick-set and uncharted Burmese jungle. There is also a feeling generated in each report that Wingate had over-reacted in demoting Coughlan in such a speedy and public manner and that Captain Coughlan had tried gainfully to rectify his mistake and extricate his men as quickly as possible.

I will leave the final word, as I often do on these website pages, to Bernard Fergusson. Once again from the pages of his book Beyond the Chindwin:

This quote is taken from the period in early April 1943, when 5 Column were approaching the fast flowing Shweli River in search of a suitable crossing point.

I had come to the conclusion that to keep Donnelly as a private soldier was a waste of time. An officer by instinct, experience and training, he could not be usefully employed as he was; and although we had a high proportion of officers, nine out of the seventy-four in our group, three were wounded, and another would in any case be handy.

So I promoted him to Sergeant ; and it is a tribute to the spirit of the men of the column as much as to himself, when I say that this interesting appointment was universally popular. One manifestation of this was when two men came up and said shyly: "Excuse me, sir, but we just want to say 'ow all of us in the column is delighted at Mr. Donnelly being made a Sergeant." Long afterwards Donnelly told me that in spite of every protest on his part, all the troops had insisted on calling him " Mr." throughout his week as a private soldier.

Seen below are some more images in relation to this story, including some of the men from 17 Platoon who survived their time on the first Chindit expedition. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

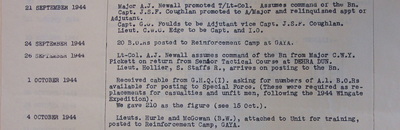

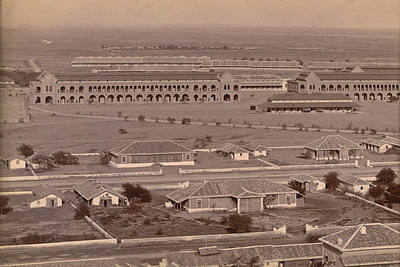

After a fairly lengthy stay in hospital after Operation Longcloth, Joseph Coughlan returned to his duties with the 13th Battalion, the King's Regiment, now stationed at the Napier Barracks in Karachi. As already stated by Frank Holland, he had been reinstated as Captain by late November 1943 and was by August 1944 the Battalion Adjutant. According to the Battalion War diary (see image in gallery above), Joseph was made up to the rank of Acting Major on the 21st September 1944. It seems clear, that the unfortunate incident at Baw on the first Wingate expedition had not in any way sullied his good reputation as an officer, nor had it prevented his continued promotion within the Battalion.

The Battalion War diary also recorded his continued leadership of D' Company, which included organising the company on a two week training exercise at Quetta in May 1945. By June that year, the Battalion was in a continual state of flux, with some men being moved to the 1st Battalion of the King's Regiment at Dehra Dun, as new reinforcements came into the Napier Barracks from the Deolali Base Camp, to reinstate the 13th King's numerical strength. There was also a significant exodus of officers and men from the Battalion, sent to bolster the numbers of a newly constructed Special Force, based at Comilla.

Major Joseph Coughlan left the 13th King's for repatriation to the United Kingdom on the 10th July 1945. On the 5th December 1945, the 13th Battalion was disbanded at Karachi and the remaining personnel where transferred over to the 1st Battalion at their base in Dehra Dun. I have not been able to find out much about Joseph's time after the war, but I do know that he lived for a time at 34 St. Bernards Road in Sutton Coldfield, Warwickshire. Sadly, Joseph died on the 3rd November 1965 whilst living at the above address, he was just 53 years old.

The Battalion War diary also recorded his continued leadership of D' Company, which included organising the company on a two week training exercise at Quetta in May 1945. By June that year, the Battalion was in a continual state of flux, with some men being moved to the 1st Battalion of the King's Regiment at Dehra Dun, as new reinforcements came into the Napier Barracks from the Deolali Base Camp, to reinstate the 13th King's numerical strength. There was also a significant exodus of officers and men from the Battalion, sent to bolster the numbers of a newly constructed Special Force, based at Comilla.

Major Joseph Coughlan left the 13th King's for repatriation to the United Kingdom on the 10th July 1945. On the 5th December 1945, the 13th Battalion was disbanded at Karachi and the remaining personnel where transferred over to the 1st Battalion at their base in Dehra Dun. I have not been able to find out much about Joseph's time after the war, but I do know that he lived for a time at 34 St. Bernards Road in Sutton Coldfield, Warwickshire. Sadly, Joseph died on the 3rd November 1965 whilst living at the above address, he was just 53 years old.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, October 2016.