Lance Corporal George Lee

Cap badge of the King's Regiment.

Cap badge of the King's Regiment.

3781436 Lance Corporal George Lee was the son of George William and Mary Elizabeth Lee and the husband of Lily Lee from Manchester.

In 1941 he was one of the original members of the 13th Battalion, the King's Liverpool Regiment, that travelled overseas to India aboard the troopship 'Oronsay'. He was allocated to Chindit Column 5 in 1942 and trained as the column clerk in preparation for the forthcoming operation.

George is mentioned on several occasions within the pages of Bernard Fergusson's book 'Beyond the Chindwin'. This book recalls the trials and tribulations of Column 5 in 1943.

The Major remembered those long endless marches early in the expedition:

Those nights of marching seemed interminable. They were tolerable only because we were able to march in threes instead of the single file, or "Column Snake", which was our normal tactical formation and the only one possible in jungle or on jungle tracks; and because we were able to sing.

Up at the head of the column marched Duncan and I and John Fraser; behind us came Cairns, the ideal Serjeant-Major, in temperament as much as efficiency; Peter Dorans; Serjeant Rothwell, the Animal Transport Serjeant; L./Cpl. Lee the clerk; Horton the cipher operator, known throughout the column as Jimmy 'Orton; Foster and White, the two Signallers; Serjeant Skillander an Irish ex-jockey and spare Serjeant in Column Headquarters; and Brookes the bugler. They were a witty and cheerful lot, and John, Duncan and I were often in fits of laughter at what we overheard from just behind us.

George was present with the Column on the 6th March as it prepared to demolish the railway line at Bonchaung. His presence in Column HQ would have meant he had a ringside seat when the bridge went up that day. Column 5 crossed the Irrawaddy River at a place called Tigyaing and then moved off eastward awaiting further orders from Brigadier Wingate.

Wingate had taken a calculated gamble in ordering his Brigade over the Irrawaddy in 1943, he had enjoyed relative success so far on the expedition and wanted to see just how far his methods of long range penetration could be pushed. It turned out to be an error of judgement on his part, as five of his Chindit Columns now found themselves trapped within an area of land, hemmed in on two sides by the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers and to the south, a motor road patrolled heavily by the Japanese.

Back in India, 4 Corps HQ in conversation with Wingate decided it was time to recall the Brigade and general dispersal was ordered on the 29th March. Wingate and his men headed west towards the Irrawaddy at place called Inywa. At this time Column 5 had been separated from the main body for about a week, they had also been unlucky with their supply drops, having missed their share at a place called Baw on the 24th March. On top of this, the Brigadier was now asking them to act as rearguard and lead the Japanese away from the area around Inywa.

Acting as decoy and 'trailing their coat', Fergusson and Column 5 moved back south-eastwards towards the Hethin Chaung. On the evening of the 28th March they had reached the outskirts of a village named Hintha. After several hours of reconnaissance in search of an alternative, Fergusson realised that he and his men would have to move through the village as thick and impenetrable bamboo jungle prevented any route around. It was at Hintha that Column 5 met their 'Waterloo' as they soon discovered that the village was occupied by a large Japanese patrol.

Fighting platoons led by Lieutenant Stibbe and Jim Harman entered the village in an attempt to clear the road of Japanese. These were met in full force by the enemy and several casualties were taken on both sides. Stibbe, himself now wounded, returned to the base position of the column and reported to the Major that the situation was getting very hot and that the Japanese were making any forward movement extremely difficult.

From his book 'Beyond the Chindwin' Bernard Fergusson takes up the story:

"Alec Macdonald was beside me, and immediately said: "I'll have a look. Come on," and disappeared up the track. I had a feeling that, having failed on Peter Dorans' flank, the Japs would try and come in on the right, somewhere down the column; so I passed the word back to try and work a small flank guard into the jungle on that side if possible.

Then I went back to the T-junction, and made arrangements to attract all the attention we could, so as to give Alec a free run. I seemed to spend the whole action trotting up and down that seventy yards of track.

There came another burst of fire from the little track, a mixture of light machine gun, tommy-guns and grenades. The Commando Platoon alone in the column had tommy-guns, which was one of the reasons I had selected them for the role. Their cheerful rattle, however, meant that the little track was no longer clear. I hurried back to the fork, and there found Denny Sharp.

"This is going to be no good," I said. "Denny, take all the animals you can find, go back to the chaung and see if you can get down it. We'll go on playing about here to keep their attention fixed; I'll try and join you farther down the chaung, but if I don't then you know the next rendezvous point. Keep away from Chaungmido, as we don't want to get Brigade muddled up in this."

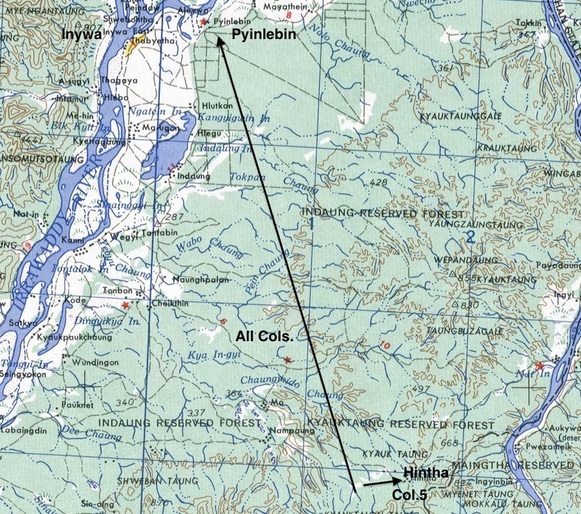

Seen below is a map of the area around Hintha and the route taken by Column 5 in leading the Japanese away from the main Brigade at Inywa. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

In 1941 he was one of the original members of the 13th Battalion, the King's Liverpool Regiment, that travelled overseas to India aboard the troopship 'Oronsay'. He was allocated to Chindit Column 5 in 1942 and trained as the column clerk in preparation for the forthcoming operation.

George is mentioned on several occasions within the pages of Bernard Fergusson's book 'Beyond the Chindwin'. This book recalls the trials and tribulations of Column 5 in 1943.

The Major remembered those long endless marches early in the expedition:

Those nights of marching seemed interminable. They were tolerable only because we were able to march in threes instead of the single file, or "Column Snake", which was our normal tactical formation and the only one possible in jungle or on jungle tracks; and because we were able to sing.

Up at the head of the column marched Duncan and I and John Fraser; behind us came Cairns, the ideal Serjeant-Major, in temperament as much as efficiency; Peter Dorans; Serjeant Rothwell, the Animal Transport Serjeant; L./Cpl. Lee the clerk; Horton the cipher operator, known throughout the column as Jimmy 'Orton; Foster and White, the two Signallers; Serjeant Skillander an Irish ex-jockey and spare Serjeant in Column Headquarters; and Brookes the bugler. They were a witty and cheerful lot, and John, Duncan and I were often in fits of laughter at what we overheard from just behind us.

George was present with the Column on the 6th March as it prepared to demolish the railway line at Bonchaung. His presence in Column HQ would have meant he had a ringside seat when the bridge went up that day. Column 5 crossed the Irrawaddy River at a place called Tigyaing and then moved off eastward awaiting further orders from Brigadier Wingate.

Wingate had taken a calculated gamble in ordering his Brigade over the Irrawaddy in 1943, he had enjoyed relative success so far on the expedition and wanted to see just how far his methods of long range penetration could be pushed. It turned out to be an error of judgement on his part, as five of his Chindit Columns now found themselves trapped within an area of land, hemmed in on two sides by the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers and to the south, a motor road patrolled heavily by the Japanese.

Back in India, 4 Corps HQ in conversation with Wingate decided it was time to recall the Brigade and general dispersal was ordered on the 29th March. Wingate and his men headed west towards the Irrawaddy at place called Inywa. At this time Column 5 had been separated from the main body for about a week, they had also been unlucky with their supply drops, having missed their share at a place called Baw on the 24th March. On top of this, the Brigadier was now asking them to act as rearguard and lead the Japanese away from the area around Inywa.

Acting as decoy and 'trailing their coat', Fergusson and Column 5 moved back south-eastwards towards the Hethin Chaung. On the evening of the 28th March they had reached the outskirts of a village named Hintha. After several hours of reconnaissance in search of an alternative, Fergusson realised that he and his men would have to move through the village as thick and impenetrable bamboo jungle prevented any route around. It was at Hintha that Column 5 met their 'Waterloo' as they soon discovered that the village was occupied by a large Japanese patrol.

Fighting platoons led by Lieutenant Stibbe and Jim Harman entered the village in an attempt to clear the road of Japanese. These were met in full force by the enemy and several casualties were taken on both sides. Stibbe, himself now wounded, returned to the base position of the column and reported to the Major that the situation was getting very hot and that the Japanese were making any forward movement extremely difficult.

From his book 'Beyond the Chindwin' Bernard Fergusson takes up the story:

"Alec Macdonald was beside me, and immediately said: "I'll have a look. Come on," and disappeared up the track. I had a feeling that, having failed on Peter Dorans' flank, the Japs would try and come in on the right, somewhere down the column; so I passed the word back to try and work a small flank guard into the jungle on that side if possible.

Then I went back to the T-junction, and made arrangements to attract all the attention we could, so as to give Alec a free run. I seemed to spend the whole action trotting up and down that seventy yards of track.

There came another burst of fire from the little track, a mixture of light machine gun, tommy-guns and grenades. The Commando Platoon alone in the column had tommy-guns, which was one of the reasons I had selected them for the role. Their cheerful rattle, however, meant that the little track was no longer clear. I hurried back to the fork, and there found Denny Sharp.

"This is going to be no good," I said. "Denny, take all the animals you can find, go back to the chaung and see if you can get down it. We'll go on playing about here to keep their attention fixed; I'll try and join you farther down the chaung, but if I don't then you know the next rendezvous point. Keep away from Chaungmido, as we don't want to get Brigade muddled up in this."

Seen below is a map of the area around Hintha and the route taken by Column 5 in leading the Japanese away from the main Brigade at Inywa. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

Column 5 suffered many casualties at Hintha, including Captain Alec MacDonald killed and Lieutenant Stibbe seriously wounded.

Flight-Lieutenant Denny Sharp, as ordered, led the majority of the column away from the village whilst Major Fergusson continued the action against the Japanese. After several more hours of fighting Bernard Fergusson called for 'second dispersal', Column bugler, Charles Brookes signalled this order and the remaining Chindits disengaged from the enemy.

The men moved away towards the pre-arranged rendezvous, this involved moving through teak forest close to a dry river bed or chaung. After a time Fergusson halted the column to take stock of the situation and to check his numbers. From his book, Beyond the Chindwin he recalls:

"With me were Duncan and John, the bulk of Column Headquarters, Tommy Blow and his platoon, Tommy Roberts and the bulk of the Support Platoon and Sergeant Thornborrow and the remnants of Philip Stibbe's Platoon. Missing were, Sergeant-Major Cairns, Pepper the runner, Lance Corporal Lee the column clerk, Foster and White the Signallers and one or two others. Cairns had last been seen helping Denny Sharp with all the animals and Foster, White and Lee were believed to have gone with the animals which carried their various bits of property."

When Bernard Fergusson at last met up with Denny Sharp at the rendezvous point, he learnt that most of the men he feared lost had been accounted for. However, in the case of George Lee, there was bad news:

"When Peter Buchanan and I reached my bivouac, I was delighted to find Denny Sharp, Jim Harman and most of his commandos, Gerry Roberts and his platoon, Bill Edge, Pepper, Foster and White, all arrived in. They had had a longer march than we, having failed to get down the chaung, and having been compelled to go back up it the way we had come in, the previous evening. Once on the hill, they got away across country; but while climbing up it, two of the most precious mules of the whole string had tumbled over the cliff into the chaung below: one carried the wireless, and the other the ciphers. Lance-Corporal Lee had gone back down to recover the ciphers, and had not been seen since."

What Bernard Fergusson did not know at that time was that the Column office box was also on one of the mules. As Column Clerk, George Lee would have felt compelled to rescue this item, as it contained the full order of battle for the unit. He would have realised that, along with the ciphers and wireless set, the office box must under no circumstances fall in to Japanese hands.

George Lee was reported as missing in action on the 28th March 1943, lost to the column on the outskirts of Hintha. It is difficult to know how long George remained alone in the jungle after failing to re-join the column that day, or the circumstances of his eventual captured by the Japanese.

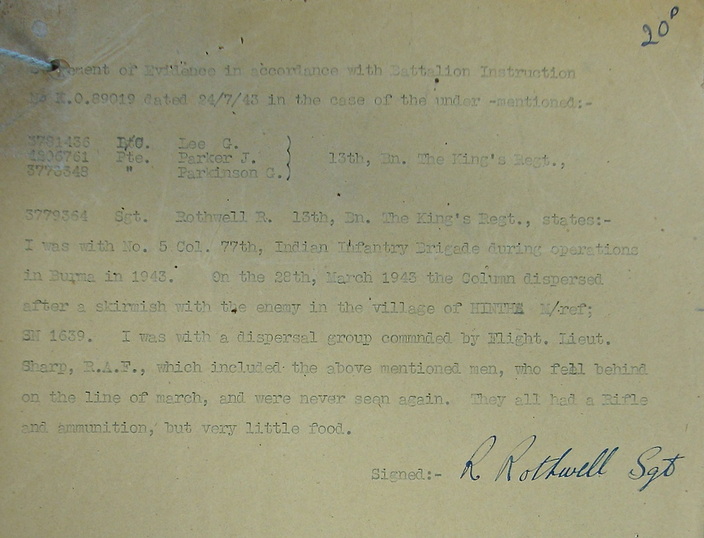

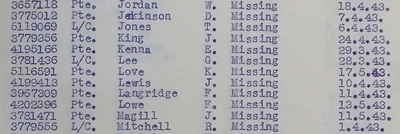

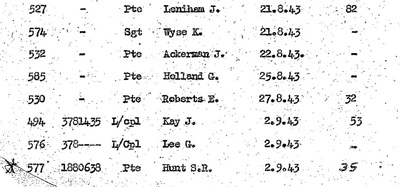

Seen below is the only witness statement given in relation to L/Cpl. Lee and his disappearance on the 28th March. It was submitted by Sergeant Rothwell, also of Column 5, on the 24th July 1943 and included information about George Lee and two other men, Ptes. J. Parker and G. Parkinson. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

Flight-Lieutenant Denny Sharp, as ordered, led the majority of the column away from the village whilst Major Fergusson continued the action against the Japanese. After several more hours of fighting Bernard Fergusson called for 'second dispersal', Column bugler, Charles Brookes signalled this order and the remaining Chindits disengaged from the enemy.

The men moved away towards the pre-arranged rendezvous, this involved moving through teak forest close to a dry river bed or chaung. After a time Fergusson halted the column to take stock of the situation and to check his numbers. From his book, Beyond the Chindwin he recalls:

"With me were Duncan and John, the bulk of Column Headquarters, Tommy Blow and his platoon, Tommy Roberts and the bulk of the Support Platoon and Sergeant Thornborrow and the remnants of Philip Stibbe's Platoon. Missing were, Sergeant-Major Cairns, Pepper the runner, Lance Corporal Lee the column clerk, Foster and White the Signallers and one or two others. Cairns had last been seen helping Denny Sharp with all the animals and Foster, White and Lee were believed to have gone with the animals which carried their various bits of property."

When Bernard Fergusson at last met up with Denny Sharp at the rendezvous point, he learnt that most of the men he feared lost had been accounted for. However, in the case of George Lee, there was bad news:

"When Peter Buchanan and I reached my bivouac, I was delighted to find Denny Sharp, Jim Harman and most of his commandos, Gerry Roberts and his platoon, Bill Edge, Pepper, Foster and White, all arrived in. They had had a longer march than we, having failed to get down the chaung, and having been compelled to go back up it the way we had come in, the previous evening. Once on the hill, they got away across country; but while climbing up it, two of the most precious mules of the whole string had tumbled over the cliff into the chaung below: one carried the wireless, and the other the ciphers. Lance-Corporal Lee had gone back down to recover the ciphers, and had not been seen since."

What Bernard Fergusson did not know at that time was that the Column office box was also on one of the mules. As Column Clerk, George Lee would have felt compelled to rescue this item, as it contained the full order of battle for the unit. He would have realised that, along with the ciphers and wireless set, the office box must under no circumstances fall in to Japanese hands.

George Lee was reported as missing in action on the 28th March 1943, lost to the column on the outskirts of Hintha. It is difficult to know how long George remained alone in the jungle after failing to re-join the column that day, or the circumstances of his eventual captured by the Japanese.

Seen below is the only witness statement given in relation to L/Cpl. Lee and his disappearance on the 28th March. It was submitted by Sergeant Rothwell, also of Column 5, on the 24th July 1943 and included information about George Lee and two other men, Ptes. J. Parker and G. Parkinson. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

Lance Corporal Lee became a prisoner of war shortly after the engagement at Hintha, nothing is known about his POW journey after this point, but we do know that he ended up, like most of the captured Chindits that year, being sent down to Rangoon Jail. No POW index card exists for George, at least none that I have found and so information about his short time in the jail is scarce. We do know however that his prisoner of war number was 576.

George Lee died inside Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on the 2nd September 1943. His body would have been taken to the English Cantonment Cemetery for burial, the cemetery was situated just a few miles from the jail, near the Royal Lakes, in the eastern sector of the city. After the war the Imperial War Graves Commission removed all the Allied burials at the Cantonment Cemetery and placed most of these at the newly constructed, Rangoon War Cemetery.

Please follow the adjoining link for to view L/Cpl. Lee's CWGC details: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2260828/LEE,%20GEORGE

In March 2008 I visited Burma along with my Mum, sister, Denise and brother, Marc. On the trip with us was Arthur Lee, the son of Lance Corporal George Lee. Arthur had decided to return to Burma for a second time, in order to donate an Army plaque representing the King's Regiment to the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Rangoon. On his previous trip he had noticed that the King's Regiment was not represented amongst the many other regimental tributes inside the Cathedral. To Arthur's great credit, this has now been corrected.

As you might imagine, to have Arthur with us on our pilgrimage in 2008 was both a great bonus and a privilege. He told us that after the war was over, Bernard Fergusson had sent his mother, Lily, a copy of the book 'Beyond the Chindwin'. I had been told by several other families who had lost men from Column 5, that Major Fegusson made a huge effort to write to all of the relevant next of kin. Arthur's recollections now confirmed this fact for me.

Arthur had also brought with him a letter, sent to his mother in mid-1943, by another Chindit soldier who was a POW in Rangoon and was also named George Lee. The letter explained the sad circumstances of Lance Corporal Lee's final few days in the prison and of his death on the 2nd September.

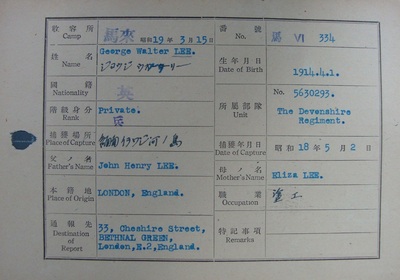

Pte. George Walter Lee, from Bethnal Green in London, was originally with the Devonshire Regiment before joining the 13th King's at the Saugor Training Camp in late September 1942. George Walter Lee had been posted to Northern Group HQ and was captured on the 2nd May 1943 after the group had begun it's return journey to India.

Frustratingly for me, although I read the letter in 2008, my research was at a very early stage and I did not realise the significance of Pte. Lee's testimony, not just in relation to George Lee, but also to my own grandfather's story. After we all returned home in 2008, Arthur and I exchanged letters and he also telephoned my Mum on at least one occasion. I also sent Arthur some general information about Column 5 and the units time in Burma, including copies of the column war diary for 1943.

I have never seen a photograph of Lance Corporal George Lee and have not been in contact with his son, Arthur, for some time. A while ago I received a photograph of the 13th King's Company Band from their tine at Secunderabad. This was sent to me by the widow of William James Livingstone the Regimental Sergeant-Major of the 13th King's in 1942. Amongst the members of the band is a soldier who bears a strong resemblance to Arthur Lee and I wondered if this might be his father, George. Hopefully one day we will know the answer.

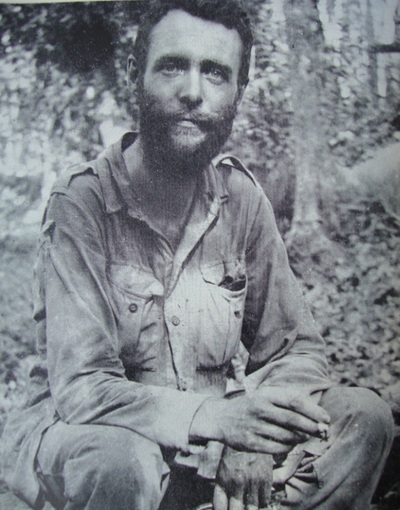

Seen below are some images relevant to the story of Lance Corporal George Lee, including the photograph of the 13th King's Company Band. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

George Lee died inside Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on the 2nd September 1943. His body would have been taken to the English Cantonment Cemetery for burial, the cemetery was situated just a few miles from the jail, near the Royal Lakes, in the eastern sector of the city. After the war the Imperial War Graves Commission removed all the Allied burials at the Cantonment Cemetery and placed most of these at the newly constructed, Rangoon War Cemetery.

Please follow the adjoining link for to view L/Cpl. Lee's CWGC details: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2260828/LEE,%20GEORGE

In March 2008 I visited Burma along with my Mum, sister, Denise and brother, Marc. On the trip with us was Arthur Lee, the son of Lance Corporal George Lee. Arthur had decided to return to Burma for a second time, in order to donate an Army plaque representing the King's Regiment to the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Rangoon. On his previous trip he had noticed that the King's Regiment was not represented amongst the many other regimental tributes inside the Cathedral. To Arthur's great credit, this has now been corrected.

As you might imagine, to have Arthur with us on our pilgrimage in 2008 was both a great bonus and a privilege. He told us that after the war was over, Bernard Fergusson had sent his mother, Lily, a copy of the book 'Beyond the Chindwin'. I had been told by several other families who had lost men from Column 5, that Major Fegusson made a huge effort to write to all of the relevant next of kin. Arthur's recollections now confirmed this fact for me.

Arthur had also brought with him a letter, sent to his mother in mid-1943, by another Chindit soldier who was a POW in Rangoon and was also named George Lee. The letter explained the sad circumstances of Lance Corporal Lee's final few days in the prison and of his death on the 2nd September.

Pte. George Walter Lee, from Bethnal Green in London, was originally with the Devonshire Regiment before joining the 13th King's at the Saugor Training Camp in late September 1942. George Walter Lee had been posted to Northern Group HQ and was captured on the 2nd May 1943 after the group had begun it's return journey to India.

Frustratingly for me, although I read the letter in 2008, my research was at a very early stage and I did not realise the significance of Pte. Lee's testimony, not just in relation to George Lee, but also to my own grandfather's story. After we all returned home in 2008, Arthur and I exchanged letters and he also telephoned my Mum on at least one occasion. I also sent Arthur some general information about Column 5 and the units time in Burma, including copies of the column war diary for 1943.

I have never seen a photograph of Lance Corporal George Lee and have not been in contact with his son, Arthur, for some time. A while ago I received a photograph of the 13th King's Company Band from their tine at Secunderabad. This was sent to me by the widow of William James Livingstone the Regimental Sergeant-Major of the 13th King's in 1942. Amongst the members of the band is a soldier who bears a strong resemblance to Arthur Lee and I wondered if this might be his father, George. Hopefully one day we will know the answer.

Seen below are some images relevant to the story of Lance Corporal George Lee, including the photograph of the 13th King's Company Band. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 03/04/2017.

From the pages of the Manchester Evening News, dated Saturday 9th June 1945, and under the simple headline Roll of Honour, are found no fewer than six family tributes to Lance Corporal George Lee. Coincidentally, the homage to George, sits directly under that of Pte. Thomas James Hazeldine, another Chindit from 1943 and also a casualty from inside Rangoon Jail.

L.Cpl. 3781436 George Lee of the King's Regiment, reported missing on March 28th 1943 in Burma, now known to have died whilst a prisoner of war in Japanese hands on 2nd September 1943. To love you and be loved by you has been an honour. From his loving wife Lily of 55 Every Street, Manchester 4. Thank you God, for the loan of a wonderful Daddy for seven years. From a loving son, Arthur.

He lives in a land of glory. From his loving Mother and Brother Sam (India) and Nellie. At the going down of the sun and in the morning, I will remember. Remembered always. From Mam.

In loving memory of George. Memories of you and us together will linger in our hearts for ever. From Doris, Steve, Jessie, Kenneth and Sylvia. A thought for today, a memory for ever. From John, Elsie, Julie and Barry.

Treasured memories of our dear brother. L.Cpl. George Lee, the King's Regiment, who died in Japanese hands. His memory to us is a golden treasure, his loss, a lifetime's regret. From Florrie and Arthur.

From the pages of the Manchester Evening News, dated Saturday 9th June 1945, and under the simple headline Roll of Honour, are found no fewer than six family tributes to Lance Corporal George Lee. Coincidentally, the homage to George, sits directly under that of Pte. Thomas James Hazeldine, another Chindit from 1943 and also a casualty from inside Rangoon Jail.

L.Cpl. 3781436 George Lee of the King's Regiment, reported missing on March 28th 1943 in Burma, now known to have died whilst a prisoner of war in Japanese hands on 2nd September 1943. To love you and be loved by you has been an honour. From his loving wife Lily of 55 Every Street, Manchester 4. Thank you God, for the loan of a wonderful Daddy for seven years. From a loving son, Arthur.

He lives in a land of glory. From his loving Mother and Brother Sam (India) and Nellie. At the going down of the sun and in the morning, I will remember. Remembered always. From Mam.

In loving memory of George. Memories of you and us together will linger in our hearts for ever. From Doris, Steve, Jessie, Kenneth and Sylvia. A thought for today, a memory for ever. From John, Elsie, Julie and Barry.

Treasured memories of our dear brother. L.Cpl. George Lee, the King's Regiment, who died in Japanese hands. His memory to us is a golden treasure, his loss, a lifetime's regret. From Florrie and Arthur.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, October 2014.