Lieutenant Robin Patrick Gordon

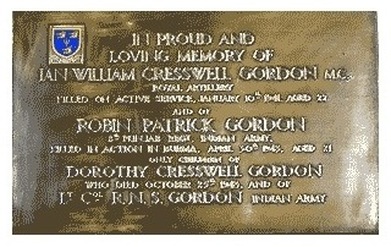

The Gordon Family Memorial inside the Dover College Chapel.

The Gordon Family Memorial inside the Dover College Chapel.

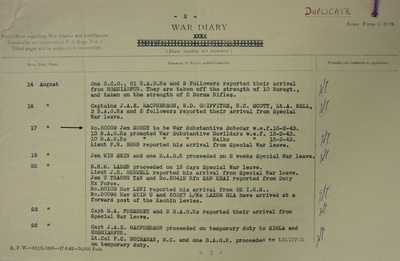

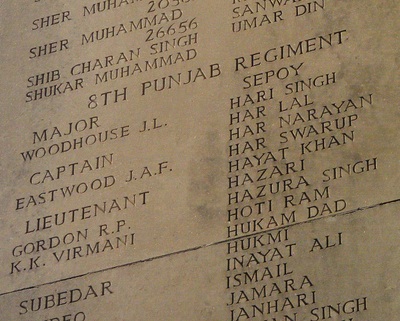

EC/5310 Robin Patrick Gordon was the youngest son of Lieutenant-Colonel R.N.S. and Dorothy Cresswell Gordon and was originally an officer with the 8th Punjab Regiment, before joining Chindit training almost at the last minute in January 1943.

Lieutenant Gordon was posted to Brigadier Wingate's own Brigade Head Quarters and acted as Animal Transport Officer for the unit in Burma. On the 7th January 1943 he was the officer in charge of all animals aboard train SA.1, as the Chindit Brigade moved off from Jhansi rail station on their journey down to Imphal in Assam.

To view Robin Gordon's CWGC details, please click on the following link:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2510024/GORDON,%20ROBIN%20PATRICK

The Gordon family suffered greatly during WW2, not only loosing youngest son Robin in Burma, but also earlier in the war their eldest son Ian William Cresswell Gordon MC, who was killed whilst serving with the Royal Artillery on January 10th 1941. Their mother, Dorothy died in October 1943, it seems quite possible that she died of a broken heart. The family have a collective memorial plaque, located in the Chapel at Dover College. To read more about the memorial at Dover College, please click on the following link:

http://www.doverwarmemorialproject.org.uk/Casualties/MoreMemorials/Schools/Dover%20College/Dover%20College%202.htm

In late March 1943 Brigadier Wingate called general dispersal and ordered all the Chindit columns to make their way back to India. He broke up his own Head Quarters into five dispersal groups, Robin found himself with Intelligence Officer, Graham Hosegood and Cipher Officer, Willie Wilding. Like so many, this group struggled to cross the Irrawaddy River in the first few days after dispersal and became trapped in the area of land between the confluence of the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers.

From the pages of his memoirs, Lieutenant Wilding remembered this time:

We spent the next couple of weeks resting and preparing for another attempt to cross the Irrawaddy. One of the Burmese Jemadars was wounded and captured during a recce to Inywa (the nearest large town) and a British Private got lost while out searching for water and was presumed captured.

Our party made some more rafts and set out for the Irrawaddy. However we found ourselves in a mangrove swamp and could not get through. We then decided to try to go east, cross the Shweli where it was but a stream, swing north and go into the Kachin Hills and there sweat out the monsoon.

Burma Riflemen Orlando and Tunnion were from this part of Burma and hoped to lead the dispersal group to their own village in the Kachin Hills and remain there until the monsoon had ended. It was only eighty miles, but we had hardly any supplies left, so we decided to find a village and obtain some food. There was not much food to be found, but the Headman offered to put us over the river for a consideration, a very considerable consideration.

Wilding remembered : "That evening, the 21st April, the Headman and his "brother" took us at racing speed to the river. It was night and we were not exactly sure where we were. We embarked, paddled round one island and disembarked, handed over nearly all of our money and set out for the hills to the west. Alas we found a wide stretch of water between us and the hills; it was the main river, we had literally been sold up the river.

The next six days are very confused in my mind. We searched the island, it was about a mile long and half a mile wide. We found a village and persuaded the villagers to sell us a meal, but this only occurred once. I had two black-outs which were alarming. When travelling in a hot country beware when the sweat getting into your eyes stops stinging as this denotes that you need salt.

On the 29th April we found a boat that floated. We decided that Second Lieutenant Pat Gordon, Lance-Corporal Purdie and Signalman Belcher, with Burma Riflemen Orlando and Tunnion as paddlers, should make the first trip. They reached the other side, then we heard Pat rallying his men and a good deal of firing and then silence. Orlando and Tunnion survived but the others were all killed. I was very sad. I thought that the first boat load would have the best chance, but I was wrong.

NB. Lieutenant Wilding is slightly out with his dates and how he spells the surnames of Lance Corporal Purdy and Signalman Belchier. Exhausted and confused as he was by this point in time, this is more than understandable.

According to his CWGC details, Signalman Herbert Michael Belchier was lost on the 30th March 1943, three days after main dispersal was called, this is almost exactly one month earlier than the incident on the Irrawaddy. It is possible that his details have been incorrectly recorded reading March instead of April. We will probably never know for sure. Lance Corporal Leslie Albert Purdy is recorded by the CWGC as having perished on the 14th April 1943, this date is much closer to the time recorded by Lieutenant Wilding in his memoirs.

To view the CWGC details for Herbert Belchier and Leslie Purdy, please click on the links below:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2505088/BELCHIER,%20HERBERT%20MICHAEL

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2521993/PURDY,%20LESLIE%20ALBERT

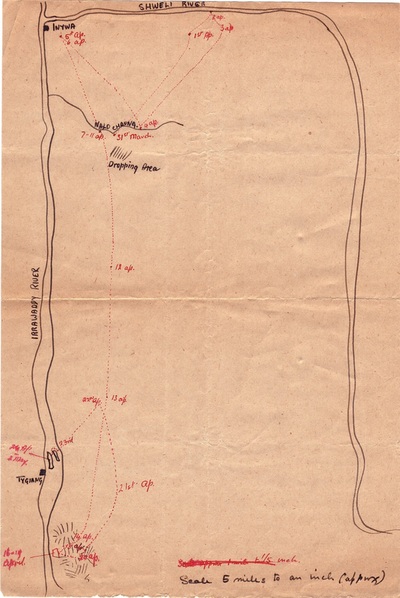

Seen below are two maps of the area where Captain Hosegood, Lieutenant Wilding and their dispersal group attempted to gain a crossing of the Irrawaddy River. The first is a contemporary map for that time, the second is Wilding's own sketch map presumably drawn during his time as a prisoner of war, or after his liberation in May 1945. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Lieutenant Gordon was posted to Brigadier Wingate's own Brigade Head Quarters and acted as Animal Transport Officer for the unit in Burma. On the 7th January 1943 he was the officer in charge of all animals aboard train SA.1, as the Chindit Brigade moved off from Jhansi rail station on their journey down to Imphal in Assam.

To view Robin Gordon's CWGC details, please click on the following link:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2510024/GORDON,%20ROBIN%20PATRICK

The Gordon family suffered greatly during WW2, not only loosing youngest son Robin in Burma, but also earlier in the war their eldest son Ian William Cresswell Gordon MC, who was killed whilst serving with the Royal Artillery on January 10th 1941. Their mother, Dorothy died in October 1943, it seems quite possible that she died of a broken heart. The family have a collective memorial plaque, located in the Chapel at Dover College. To read more about the memorial at Dover College, please click on the following link:

http://www.doverwarmemorialproject.org.uk/Casualties/MoreMemorials/Schools/Dover%20College/Dover%20College%202.htm

In late March 1943 Brigadier Wingate called general dispersal and ordered all the Chindit columns to make their way back to India. He broke up his own Head Quarters into five dispersal groups, Robin found himself with Intelligence Officer, Graham Hosegood and Cipher Officer, Willie Wilding. Like so many, this group struggled to cross the Irrawaddy River in the first few days after dispersal and became trapped in the area of land between the confluence of the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers.

From the pages of his memoirs, Lieutenant Wilding remembered this time:

We spent the next couple of weeks resting and preparing for another attempt to cross the Irrawaddy. One of the Burmese Jemadars was wounded and captured during a recce to Inywa (the nearest large town) and a British Private got lost while out searching for water and was presumed captured.

Our party made some more rafts and set out for the Irrawaddy. However we found ourselves in a mangrove swamp and could not get through. We then decided to try to go east, cross the Shweli where it was but a stream, swing north and go into the Kachin Hills and there sweat out the monsoon.

Burma Riflemen Orlando and Tunnion were from this part of Burma and hoped to lead the dispersal group to their own village in the Kachin Hills and remain there until the monsoon had ended. It was only eighty miles, but we had hardly any supplies left, so we decided to find a village and obtain some food. There was not much food to be found, but the Headman offered to put us over the river for a consideration, a very considerable consideration.

Wilding remembered : "That evening, the 21st April, the Headman and his "brother" took us at racing speed to the river. It was night and we were not exactly sure where we were. We embarked, paddled round one island and disembarked, handed over nearly all of our money and set out for the hills to the west. Alas we found a wide stretch of water between us and the hills; it was the main river, we had literally been sold up the river.

The next six days are very confused in my mind. We searched the island, it was about a mile long and half a mile wide. We found a village and persuaded the villagers to sell us a meal, but this only occurred once. I had two black-outs which were alarming. When travelling in a hot country beware when the sweat getting into your eyes stops stinging as this denotes that you need salt.

On the 29th April we found a boat that floated. We decided that Second Lieutenant Pat Gordon, Lance-Corporal Purdie and Signalman Belcher, with Burma Riflemen Orlando and Tunnion as paddlers, should make the first trip. They reached the other side, then we heard Pat rallying his men and a good deal of firing and then silence. Orlando and Tunnion survived but the others were all killed. I was very sad. I thought that the first boat load would have the best chance, but I was wrong.

NB. Lieutenant Wilding is slightly out with his dates and how he spells the surnames of Lance Corporal Purdy and Signalman Belchier. Exhausted and confused as he was by this point in time, this is more than understandable.

According to his CWGC details, Signalman Herbert Michael Belchier was lost on the 30th March 1943, three days after main dispersal was called, this is almost exactly one month earlier than the incident on the Irrawaddy. It is possible that his details have been incorrectly recorded reading March instead of April. We will probably never know for sure. Lance Corporal Leslie Albert Purdy is recorded by the CWGC as having perished on the 14th April 1943, this date is much closer to the time recorded by Lieutenant Wilding in his memoirs.

To view the CWGC details for Herbert Belchier and Leslie Purdy, please click on the links below:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2505088/BELCHIER,%20HERBERT%20MICHAEL

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2521993/PURDY,%20LESLIE%20ALBERT

Seen below are two maps of the area where Captain Hosegood, Lieutenant Wilding and their dispersal group attempted to gain a crossing of the Irrawaddy River. The first is a contemporary map for that time, the second is Wilding's own sketch map presumably drawn during his time as a prisoner of war, or after his liberation in May 1945. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

In August 1947, Lieutenant Willie Wilding was kind enough to write a letter to the father of Graham Hosegood. In this letter he describes the time after the immediate dispersal in late March 1943 and the circumstances of Lieutenant Gordon's death as he led the first boat over the Irrawaddy on the 29th April. This letter is part of the diary and papers of Captain Graham Cowell Hosegood and is reproduced here by kind permission of Liz Hosegood and Graham's family.

Dear Mr Hosegood,

Thank you for your letter and good wishes. I only wish I could have done more for Graham.

In the following story I want you to believe that I am sticking to the whole truth. I am not trying to increase your pride in Graham in order to relieve your sorrow. He did his duty and more than his duty.

Our adventures while the Brigade was still a fighting force have been described by many, sometimes distorted and exaggerated, but they are public property and you must know them well. Our private adventure started on 31st March 1943 when Brigade H.Q. split up and Graham led his small command away to try and escape back to India. The party consisted of Graham, myself, Pat Gordon (The Brigade H.Q. Animal Transport Officer), Jemadar Moudie, Riflemen Orlando & Tunnion (all three of them Burma Rifles) and twenty two British Other Ranks.

We were all desperately tired and rather hungry, but we had just received a supply drop and had five days rations each. We all had rifles except Graham and I who had revolvers, and we had fifty rounds per rifle. We were two hundred miles behind the enemy lines and had no prospect of help from anyone; moreover we had been stirring the Japs up for some six weeks. The men were all specialists. That was the debit side. In our favour we had in Graham a leader in whom we all reposed the greatest confidence; he had shown himself brave and cool in action, and uncannily efficient at map reading and compass marching. Two accomplishments worth rubies in the jungle.

So Graham set out at the head of his little party with high hopes and thank heavens full packs. That night we marched to and bivouacked at the Nalo Chaung (see maps). This was a most friendly watercourse, wherever you dig you would find water. There Graham and I shared a tin of beans and one of bully beef. This was a great extravagance, but as we had marched fifty miles in the last 48 hours on a packet of biscuits between us, we felt we deserved it.

Next day we started out North to the Shweli, we did not like it, water was scarce on both sides and we had to have water. But the Brigadier had given his orders and he was obeyed. So we marched north from dawn to about 3pm. It was very dull, the only remarkable thing was that we (or rather Graham) made a perfect ‘landfall’ (you must understand that the jungle is as featureless as the sea) and we halted at the stagnant pool which we had aimed at, after a ten mile march, a piece of navigation which spoke well for our chances. We spent the night there, and were distorted by mosquitoes. That was April 1st. The morning of the second ushered in a much more exciting day as we moved up to the river - sent Moudie out to look-see, but he found no boats - we made a bamboo raft and launched it at about 11pm. But bamboo is treacherous stuff and very noisy, no sooner had we got it into the river than the Japs opened up from the other bank with everything they had.

Our rifles made a poor reply- however we fired a few rounds - probably uselessly - and withdrew without loss into the jungle - and slept solidly until mid-day. The jungle was terribly thick here and an Army Corps would have lain hid easily so we were safe as in church. Graham woke at mid-day and got us going at once, he knew morale had slumped and we must not be allowed time to think. At this time the whole weight of responsibility was on Graham’s shoulders. Pat was a most gallant fellow, brave to a fault, but plans were not his forte - I had been overworked as Brigade Cipher Officer and could scarcely keep going for the first week or so, poor Graham knew ‘The loneliness of High Command’ as keenly as any Admiral or General. Well, we marched until dusk - cutting our way, as we dare not use tracks, through creepers three inches thick until we could go no further and we ate sparingly and slept exhausted. That was the third of April.

Next morning we were off again, we had to find water so we shaped our course for the Nalo Chaung. We arrived there feeling quite done up by 4pm. Then we found water - the first since the Shweli. We drank pints, made tea and felt much better. Graham announced that next day, the fifth of April, we would march to Inywa - at the confluence of the Shweli and Irrawaddy where we had tried to cross as a Brigade on 30th March. The Japs would never suspect a second attempt there so soon and we knew that there were boats. So off we set again, spirits high and halted about two miles from the river. Moudie and his men went forward to scout while we impounded the water bottles and issued sparing rations of water. Dusk fell but Moudie had not returned.

Next morning patrols went out but we had no luck, we must wait until next morning. Graham and I spent some time cutting each others hair and trimming our beards. Graham had a beauty, red and curly, but mine was no good. At dusk Orlando and Tunnion arrived - Moudie had been fired on and killed they had returned as soon as they could - Inywa was full of Japs. Poor Moudie, we had lost a friend and faithful ally. I should say now that in fact Moudie was not killed as we met him again at Maymyo POW Camp and I believe that he gave the information of our capture to the authorities when he made his escape later on. We were in trouble again; two days in a very hot jungle with one water bottle per man is unpleasant. We must have water so on the seventh of April we returned once more to our haven at Nalo Chaung. Of course we went to a different point each time but we had to have water - our rations were concentrated and sustained without filling - also tea was our stand by and in adversity we just had to have tea.

By now rations were getting short and Graham had a brain wave. He sent a party under Pat to the dropping area to get any rations they could find that Brigade had left. They brought back six days worth per man which was all we could carry. It looked as if Heaven was on our side. Graham made yet another plan - one which I still think was the best possible for us. We were to march due south for about 30 miles to where the hills rose out of the jungle near the river. There each man was to make a small bamboo raft - to carry his boots and rifle and pack. Then with this as a life belt we were each in our own time to swim the ¾ mile wide Irrawaddy. Graham called the men and told them the plan. Spirits soared again and we were to start next day, the eigth April.

Then our troubles began, a man failed to return from the water party sent to fill bottles. He was a difficult man and probably light headed with fear - anyway he would probably blunder into a village - and be captured - under pressure he would give away our plan (and I for one would not blame him). There was nothing for it but to wait for a few days to see what would happen, perhaps he would return and if the worst should happen - the Japs would be out in there time table and we could get through. In any event a rest would do us all good. So off I went to the dropping area taking an unarmed section so we could carry more, found another six days per man and returned in triumph only to get a wigging from Graham for risking it. He was quite right of course, it was an unjustifiable risk but one which, in the same circumstances I should take again.

On the ninth, tenth and eleventh of April we rested and stuffed two days rations each. Don’t blame us, we could carry no more than six days and this we had safely in our packs - we were awfully hungry and anyway the rations weren't much. Those were good days. We could not wash - water was too scarce but an early monsoon shower blew up and we all danced naked in the rain. Then we realised for the first time how terribly thin we all were. Most of the time we lay on our backs and yarned away. Graham told me about you all, of the lights of the ships in the channel, of the wash basin you had fitted in his room, of his hopes and ambitions for his career in the shipping trade. It was then that I learnt how devoted he was to you all. On the twelfth we set out again this time south. Ten miles a day was our limit then we should need a couple of days to get across the river and we should still have a days ration in hand to carry us a safe distance from the river.

We marched for three plodding dull dusty days - then we were in the hills. The only excitement being on our second day we found a running stream - our first since the Shweli. We were loath to leave it. So we reached the hills by the evening of the fourteenth. On the 15th I took a patrol to the river, but the jungle was too thick and I had to return. Graham sent a Sergeant to try further south - he returned reporting success. So on the night of the fifteenth we were to start. A re-entrant easily visible was fixed as a rendezvous point and all should have been well, Graham and I went forward and Pat was to join us at dusk. Then came another set back - the rafts were too big and could not possibly be carried through the jungle. So we had to wait a day while the men remade them. I was furious but Graham, as calm as ever just switched his plan to a day later.

Seen below are photographs of Captain Graham Hosegood and Lieutenant R. A. 'Willie' Wilding. Please click on each image to bring them forward on the page.

Dear Mr Hosegood,

Thank you for your letter and good wishes. I only wish I could have done more for Graham.

In the following story I want you to believe that I am sticking to the whole truth. I am not trying to increase your pride in Graham in order to relieve your sorrow. He did his duty and more than his duty.

Our adventures while the Brigade was still a fighting force have been described by many, sometimes distorted and exaggerated, but they are public property and you must know them well. Our private adventure started on 31st March 1943 when Brigade H.Q. split up and Graham led his small command away to try and escape back to India. The party consisted of Graham, myself, Pat Gordon (The Brigade H.Q. Animal Transport Officer), Jemadar Moudie, Riflemen Orlando & Tunnion (all three of them Burma Rifles) and twenty two British Other Ranks.

We were all desperately tired and rather hungry, but we had just received a supply drop and had five days rations each. We all had rifles except Graham and I who had revolvers, and we had fifty rounds per rifle. We were two hundred miles behind the enemy lines and had no prospect of help from anyone; moreover we had been stirring the Japs up for some six weeks. The men were all specialists. That was the debit side. In our favour we had in Graham a leader in whom we all reposed the greatest confidence; he had shown himself brave and cool in action, and uncannily efficient at map reading and compass marching. Two accomplishments worth rubies in the jungle.

So Graham set out at the head of his little party with high hopes and thank heavens full packs. That night we marched to and bivouacked at the Nalo Chaung (see maps). This was a most friendly watercourse, wherever you dig you would find water. There Graham and I shared a tin of beans and one of bully beef. This was a great extravagance, but as we had marched fifty miles in the last 48 hours on a packet of biscuits between us, we felt we deserved it.

Next day we started out North to the Shweli, we did not like it, water was scarce on both sides and we had to have water. But the Brigadier had given his orders and he was obeyed. So we marched north from dawn to about 3pm. It was very dull, the only remarkable thing was that we (or rather Graham) made a perfect ‘landfall’ (you must understand that the jungle is as featureless as the sea) and we halted at the stagnant pool which we had aimed at, after a ten mile march, a piece of navigation which spoke well for our chances. We spent the night there, and were distorted by mosquitoes. That was April 1st. The morning of the second ushered in a much more exciting day as we moved up to the river - sent Moudie out to look-see, but he found no boats - we made a bamboo raft and launched it at about 11pm. But bamboo is treacherous stuff and very noisy, no sooner had we got it into the river than the Japs opened up from the other bank with everything they had.

Our rifles made a poor reply- however we fired a few rounds - probably uselessly - and withdrew without loss into the jungle - and slept solidly until mid-day. The jungle was terribly thick here and an Army Corps would have lain hid easily so we were safe as in church. Graham woke at mid-day and got us going at once, he knew morale had slumped and we must not be allowed time to think. At this time the whole weight of responsibility was on Graham’s shoulders. Pat was a most gallant fellow, brave to a fault, but plans were not his forte - I had been overworked as Brigade Cipher Officer and could scarcely keep going for the first week or so, poor Graham knew ‘The loneliness of High Command’ as keenly as any Admiral or General. Well, we marched until dusk - cutting our way, as we dare not use tracks, through creepers three inches thick until we could go no further and we ate sparingly and slept exhausted. That was the third of April.

Next morning we were off again, we had to find water so we shaped our course for the Nalo Chaung. We arrived there feeling quite done up by 4pm. Then we found water - the first since the Shweli. We drank pints, made tea and felt much better. Graham announced that next day, the fifth of April, we would march to Inywa - at the confluence of the Shweli and Irrawaddy where we had tried to cross as a Brigade on 30th March. The Japs would never suspect a second attempt there so soon and we knew that there were boats. So off we set again, spirits high and halted about two miles from the river. Moudie and his men went forward to scout while we impounded the water bottles and issued sparing rations of water. Dusk fell but Moudie had not returned.

Next morning patrols went out but we had no luck, we must wait until next morning. Graham and I spent some time cutting each others hair and trimming our beards. Graham had a beauty, red and curly, but mine was no good. At dusk Orlando and Tunnion arrived - Moudie had been fired on and killed they had returned as soon as they could - Inywa was full of Japs. Poor Moudie, we had lost a friend and faithful ally. I should say now that in fact Moudie was not killed as we met him again at Maymyo POW Camp and I believe that he gave the information of our capture to the authorities when he made his escape later on. We were in trouble again; two days in a very hot jungle with one water bottle per man is unpleasant. We must have water so on the seventh of April we returned once more to our haven at Nalo Chaung. Of course we went to a different point each time but we had to have water - our rations were concentrated and sustained without filling - also tea was our stand by and in adversity we just had to have tea.

By now rations were getting short and Graham had a brain wave. He sent a party under Pat to the dropping area to get any rations they could find that Brigade had left. They brought back six days worth per man which was all we could carry. It looked as if Heaven was on our side. Graham made yet another plan - one which I still think was the best possible for us. We were to march due south for about 30 miles to where the hills rose out of the jungle near the river. There each man was to make a small bamboo raft - to carry his boots and rifle and pack. Then with this as a life belt we were each in our own time to swim the ¾ mile wide Irrawaddy. Graham called the men and told them the plan. Spirits soared again and we were to start next day, the eigth April.

Then our troubles began, a man failed to return from the water party sent to fill bottles. He was a difficult man and probably light headed with fear - anyway he would probably blunder into a village - and be captured - under pressure he would give away our plan (and I for one would not blame him). There was nothing for it but to wait for a few days to see what would happen, perhaps he would return and if the worst should happen - the Japs would be out in there time table and we could get through. In any event a rest would do us all good. So off I went to the dropping area taking an unarmed section so we could carry more, found another six days per man and returned in triumph only to get a wigging from Graham for risking it. He was quite right of course, it was an unjustifiable risk but one which, in the same circumstances I should take again.

On the ninth, tenth and eleventh of April we rested and stuffed two days rations each. Don’t blame us, we could carry no more than six days and this we had safely in our packs - we were awfully hungry and anyway the rations weren't much. Those were good days. We could not wash - water was too scarce but an early monsoon shower blew up and we all danced naked in the rain. Then we realised for the first time how terribly thin we all were. Most of the time we lay on our backs and yarned away. Graham told me about you all, of the lights of the ships in the channel, of the wash basin you had fitted in his room, of his hopes and ambitions for his career in the shipping trade. It was then that I learnt how devoted he was to you all. On the twelfth we set out again this time south. Ten miles a day was our limit then we should need a couple of days to get across the river and we should still have a days ration in hand to carry us a safe distance from the river.

We marched for three plodding dull dusty days - then we were in the hills. The only excitement being on our second day we found a running stream - our first since the Shweli. We were loath to leave it. So we reached the hills by the evening of the fourteenth. On the 15th I took a patrol to the river, but the jungle was too thick and I had to return. Graham sent a Sergeant to try further south - he returned reporting success. So on the night of the fifteenth we were to start. A re-entrant easily visible was fixed as a rendezvous point and all should have been well, Graham and I went forward and Pat was to join us at dusk. Then came another set back - the rafts were too big and could not possibly be carried through the jungle. So we had to wait a day while the men remade them. I was furious but Graham, as calm as ever just switched his plan to a day later.

Seen below are photographs of Captain Graham Hosegood and Lieutenant R. A. 'Willie' Wilding. Please click on each image to bring them forward on the page.

Wilding's letter continues:

On the sixteenth then, we did set out going carefully down the almost sheer west flank of the hills and reached the jungle just as it was dark. The going was frightful. We cut our way and made a few hundred yards by midnight then the moon sank and Graham gave the order to bivouac. I am afraid that the Sergeant's patrol was not truthful. For two days we fought and struggled through the jungle - one man almost went mad, but recovered later - the Jungle got even thicker - rations had run out and our reserves of strength had been used up by this hectic cutting. Graham had the high courage to face the fact that even if the river was at our feet we could none of us have swam it. Then we found a track running east and then north - we halted about 100 yards away from it and Pat went off with a section to find a village and bring back food by force if necessary. In a couple of hours he was back with dried fish, salt, rice, tomatoes and jaggery (a sort of crude fudge) and, more welcome than any, a promise of a boat. So on the night of the eighteenth we slept with a full stomach and light hearts once more.

On the nineteenth and twentieth we moved round in the jungle as a precaution against treachery and kept in touch with the village. I think they were honest enough but they could not keep their word. The Japs pinched their boats. So on the evening of the twentieth I took a section to forage - our friendly village was by now full of Japs so we had to find another. We met a hostile reception, but we showed fight and got away with some rice and fish, then rejoining Graham in the hills. This was on the 21st April in the morning. Graham had to make another decision - this time we would swing east - cross the Shweli where it was not so formidable - then north into the Kachin Hills where we would be sure of a welcome. We would spread out our force and live in villages until an opportunity presented itself for a return home to India. So on the morning of the 21st after a short rest we set out, left the friendly hills, and went east by north.

By midday on 23rd we were back at our old bivouac by the running stream. This time we could not tear ourselves away so we all bathed and slept there. Another foraging raid was essential as we had a couple of days march before we reached the Shweli and we dare not be seen marching east. It was Pat’s turn, Graham wanted to go but he was too valuable to risk, so we would not let him and as usual Pat came back with food and the offer of a boat. This time he kidnapped the Headman as a guide and a hostage. That night we were guided down to the river. We did not like it a bit, but it was clearly our duty to take every chance to get home, so we felt we must risk it. Graham’s chief worry was that he could not tell from what point we should cross; there was an island and just after the moon rose we set sail - round the island and then ashore we marched westward, found our way barred by an arm of water, we then made north and passed the barrier. We came to another and found a way round once more, then we found a stretch of water which we could find no way round. It was peaceful looking under the moon so I, as the shortest started to wade in. Soon it was up to my neck and then I was swept away. I am a strong swimmer, but had my work cut out to make the shore. Clearly we had been sold out to the Japs. We were on a second island not marked on the map. We sadly retraced our steps - got into the cover of some elephant grass and prepared to fight it out.

This was the 23rd of April and for seven days we lived on that island straining every nerve and planning how to get off. Our food ran out but there was all too much water so we could live. On the seventh day Graham came back from an early morning swim with news of a boat; a wreck but, perhaps! We worked all day on it with our Kukris and made it seaworthy. It would carry five so Graham ordered that Pat should go across first - he felt that Pat, whose parents had lost their other son already in the war, must have the best chance. This was very typical of Graham’s thoughtfulness. Alas, before they could land the Japs opened fire. Poor Pat never had a chance, but he got his two B.O.R’s (British Other Ranks) and his two boatmen (Orlando and Tunnion) ashore and after a short fight there was silence. We never saw Pat again, nor either of the British soldiers. Orlando and Tunnion were captured. Of course all this took place at night and it its difficult to say what really happened.

On Graham’s orders, we were to split up in twos and threes and spread ourselves all over the island to make it more difficult for the Japs to find us. I found myself alone looking west across the river to Tigyang from whence we expected the Japs and soon they came. I need not stress the loneliness of those three days. On the third day - one hour after darkness fell we went to rendezvous at a given spot. We all met there, but not Graham; he and two men had been hunted and could not get to the appointed place. I had to make the decision. We must fight, but we had no bayonets and our rifles had seized up having got wet and we had no oil. We could not put up any sort of show against some two hundred Japs and Burmese - fighting was useless- we must surrender. It was a bitter pill, we thought perhaps the Japs would be content with just us and forget about Graham and his men, but their intelligence service was too good and they collected him next day.

That was the end of our freedom.

I should like to add one thing - please put away from your thoughts the question of torture during interrogation. Graham and I were able to co-ordinate a story which the Japs did not shake. I need not say that it was not the truth. Graham was true to his duty and gave nothing away but he did not suffer torture please believe that. It is absolutely true.

Other people will have written to tell you of Graham’s great patience and courage in Rangoon, he never complained or groused he was always cheerful and he was kind to everyone, you may be very proud of him. He was buried on the 9th April 1945 in the Rangoon Cemetery.

The funeral party consisted of Flight-Lieutenant Edmonds, Lieuts. Horton, Gudgeon, Gibson, Quale and myself. We were as well turned out as borrowing could make us. His coffin was carried out on our shoulders through two ranks of his comrades to the salute. Then through the guardroom with the Jap Guard at the present. Then, and forgive us as we could carry him no further, had to use a hand cart through the streets of Rangoon to the cemetery. A grave was dug - we said what prayers we could - saluted - took back the Union Jack we had used for nearly three hundred friends and returned sadly. I had lost a great friend.

This is a long story but it is quite true, you should be proud of Graham, he never forgot any of you and he never forgot his religion. Please let me know if there are any further questions you would like me to answer.

Yours sincerely

R.A. Wilding

This is all the information to hand, that describes the last few days of Lieutenant Gordon's life. It is clear that he played a large part in keeping this stricken group of men together and had supported Captain Hosegood in a resolute manner. It also seems to be the case, that when the group needed to gather food, water or help from the various Burmese villages in the area, Lieutenant Gordon was the man they turned to.

Willie Wilding's letter describes the great hardship of those last fateful few weeks in and around the Nalo Chaung; hunger, thirst and at times sheer exhaustion harried the isolated Chindits as they tried in vain to cross the Irrawaddy. Not much is known about what happened to the men in Pat Gordon's boat on the 29th April. It seems likely that Lieutenant Gordon was killed outright during the crossing and that the same fate befell both Signalman Belchier and Lance Corporal Purdy. Burma Riflemen, Tunnion and Orlando tried to evade the Japanese after the ambush, but were captured and became prisoners of war, joining their comrade Jemadar Moody who was being held at Tigyaing at the time.

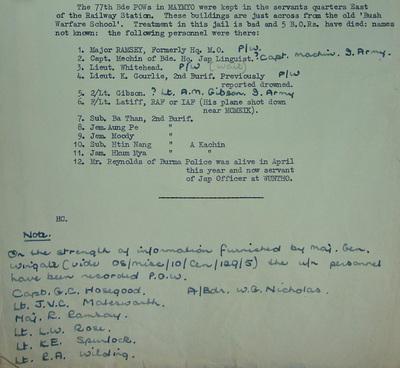

Moody, as mentioned by Lieutenant Wilding in his letter to Graham Hosegood's father, escaped later on after the Chindit POW's had been collected together and sent on to a concentration camp in the Burmese hill station town of Maymyo. He successfully rejoined his unit at Karachi in India, where they were enjoying a period of rest and recuperation, he later became involved in the preparations for Operation Thursday. Please see the report on those held at the Maymyo Camp in the final gallery of images below.

The eventual fate of Riflemen Tunnion and Orlando is not known, however, their names do not appear in any Longcloth casualty listings and to that end, I believe that they survived their time as prisoners of war and returned home to the Kachin Hills after liberation. Captain Hosegood and Lieutenant Wilding along with all the surviving Chindit POW's were taken down to Rangoon Central Jail during the latter weeks of May and the early weeks of June 1943. Willie Wilding was liberated from his Japanese captors close to the Burmese town of Pegu on the 29th April 1945, excruciatingly Graham Hosegood perished just a few short weeks before liberation, suffering from general ill health and exhaustion.

For more information about Captain Hosegood and the experiences of men who became prisoners of war in 1943, please click on the following links:

Graham Hosegood

Chindit POW's

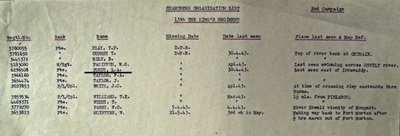

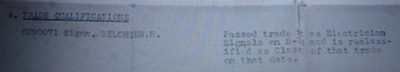

6290071 Signalman Herbert Michael Belchier was the son of Thomas and Mary Belchier from Enfield in Middlesex. He had been a last minute reinforcement for Operation Longcloth, joining the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade on the 19th January 1943 as the unit moved down to Imphal in Assam. Herbert and around thirty other Signalmen were attached to Wingate's Brigade from their temporary base at Jhansi and had previously taken part in clandestine operations in the Yunnan Provinces of China, possibly as part of the 204 Military Mission.

6296508 Lance Corporal Leslie Albert Purdy was the son of Violet May Purdy from Walthamstow in Essex. Leslie, originally a soldier in the Buffs (East Kent Regiment) had joined 142 Commando on the 30th September 1942 at the Chindit training camp in Saugor. He was posted to Wingate's Head Quarters later that year. The CWGC have Leslie's date of death recorded as the 14th April 1943, however, all documents in relation to his disappearance on Operation Longcloth show his missing in action date as the 30th April. Fellow Commando, Pte. James Dixon gave a witness statement after his liberation from Rangoon Jail, stating that he last saw Lance Corporal Purdy on the 30th April attempting to cross the Irrawaddy, this backs up the information contained in Lieutenant Wilding's letter and almost certainly places James Dixon with Captain Hosegood's dispersal party.

Another member of Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters, Pte. George Walter Lee, gave a short witness statement in regards to Lance-Corporal Purdy and his last known movements in 1943. In a letter dated 6th November 1945, written to the Army Investigation Bureau for missing persons in Burma, he wrote:

6296508 Lance-Corporal L.A. Purdy

Sir, a Purdy was attached to my party of 26 when Brigadier Wingate split us up into small party's, but I do not know if it is the same one you mention. This man was in the 142 Commandos and was in Brigade Head Quarters. He was killed whilst trying to re-cross the Irrawaddy River with me. He is one of a few names I know here, the others died in Rangoon Jail, but I do not know all their numbers or regiment details.

Pte. Lee, was also a surviving POW from Rangoon Jail and went on to give many similar witness statements to the Investigation Bureau after his liberation in 1945.

Seen below are some final images in relation to the story of Lieutenant Robin Patrick Gordon. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

On the sixteenth then, we did set out going carefully down the almost sheer west flank of the hills and reached the jungle just as it was dark. The going was frightful. We cut our way and made a few hundred yards by midnight then the moon sank and Graham gave the order to bivouac. I am afraid that the Sergeant's patrol was not truthful. For two days we fought and struggled through the jungle - one man almost went mad, but recovered later - the Jungle got even thicker - rations had run out and our reserves of strength had been used up by this hectic cutting. Graham had the high courage to face the fact that even if the river was at our feet we could none of us have swam it. Then we found a track running east and then north - we halted about 100 yards away from it and Pat went off with a section to find a village and bring back food by force if necessary. In a couple of hours he was back with dried fish, salt, rice, tomatoes and jaggery (a sort of crude fudge) and, more welcome than any, a promise of a boat. So on the night of the eighteenth we slept with a full stomach and light hearts once more.

On the nineteenth and twentieth we moved round in the jungle as a precaution against treachery and kept in touch with the village. I think they were honest enough but they could not keep their word. The Japs pinched their boats. So on the evening of the twentieth I took a section to forage - our friendly village was by now full of Japs so we had to find another. We met a hostile reception, but we showed fight and got away with some rice and fish, then rejoining Graham in the hills. This was on the 21st April in the morning. Graham had to make another decision - this time we would swing east - cross the Shweli where it was not so formidable - then north into the Kachin Hills where we would be sure of a welcome. We would spread out our force and live in villages until an opportunity presented itself for a return home to India. So on the morning of the 21st after a short rest we set out, left the friendly hills, and went east by north.

By midday on 23rd we were back at our old bivouac by the running stream. This time we could not tear ourselves away so we all bathed and slept there. Another foraging raid was essential as we had a couple of days march before we reached the Shweli and we dare not be seen marching east. It was Pat’s turn, Graham wanted to go but he was too valuable to risk, so we would not let him and as usual Pat came back with food and the offer of a boat. This time he kidnapped the Headman as a guide and a hostage. That night we were guided down to the river. We did not like it a bit, but it was clearly our duty to take every chance to get home, so we felt we must risk it. Graham’s chief worry was that he could not tell from what point we should cross; there was an island and just after the moon rose we set sail - round the island and then ashore we marched westward, found our way barred by an arm of water, we then made north and passed the barrier. We came to another and found a way round once more, then we found a stretch of water which we could find no way round. It was peaceful looking under the moon so I, as the shortest started to wade in. Soon it was up to my neck and then I was swept away. I am a strong swimmer, but had my work cut out to make the shore. Clearly we had been sold out to the Japs. We were on a second island not marked on the map. We sadly retraced our steps - got into the cover of some elephant grass and prepared to fight it out.

This was the 23rd of April and for seven days we lived on that island straining every nerve and planning how to get off. Our food ran out but there was all too much water so we could live. On the seventh day Graham came back from an early morning swim with news of a boat; a wreck but, perhaps! We worked all day on it with our Kukris and made it seaworthy. It would carry five so Graham ordered that Pat should go across first - he felt that Pat, whose parents had lost their other son already in the war, must have the best chance. This was very typical of Graham’s thoughtfulness. Alas, before they could land the Japs opened fire. Poor Pat never had a chance, but he got his two B.O.R’s (British Other Ranks) and his two boatmen (Orlando and Tunnion) ashore and after a short fight there was silence. We never saw Pat again, nor either of the British soldiers. Orlando and Tunnion were captured. Of course all this took place at night and it its difficult to say what really happened.

On Graham’s orders, we were to split up in twos and threes and spread ourselves all over the island to make it more difficult for the Japs to find us. I found myself alone looking west across the river to Tigyang from whence we expected the Japs and soon they came. I need not stress the loneliness of those three days. On the third day - one hour after darkness fell we went to rendezvous at a given spot. We all met there, but not Graham; he and two men had been hunted and could not get to the appointed place. I had to make the decision. We must fight, but we had no bayonets and our rifles had seized up having got wet and we had no oil. We could not put up any sort of show against some two hundred Japs and Burmese - fighting was useless- we must surrender. It was a bitter pill, we thought perhaps the Japs would be content with just us and forget about Graham and his men, but their intelligence service was too good and they collected him next day.

That was the end of our freedom.

I should like to add one thing - please put away from your thoughts the question of torture during interrogation. Graham and I were able to co-ordinate a story which the Japs did not shake. I need not say that it was not the truth. Graham was true to his duty and gave nothing away but he did not suffer torture please believe that. It is absolutely true.

Other people will have written to tell you of Graham’s great patience and courage in Rangoon, he never complained or groused he was always cheerful and he was kind to everyone, you may be very proud of him. He was buried on the 9th April 1945 in the Rangoon Cemetery.

The funeral party consisted of Flight-Lieutenant Edmonds, Lieuts. Horton, Gudgeon, Gibson, Quale and myself. We were as well turned out as borrowing could make us. His coffin was carried out on our shoulders through two ranks of his comrades to the salute. Then through the guardroom with the Jap Guard at the present. Then, and forgive us as we could carry him no further, had to use a hand cart through the streets of Rangoon to the cemetery. A grave was dug - we said what prayers we could - saluted - took back the Union Jack we had used for nearly three hundred friends and returned sadly. I had lost a great friend.

This is a long story but it is quite true, you should be proud of Graham, he never forgot any of you and he never forgot his religion. Please let me know if there are any further questions you would like me to answer.

Yours sincerely

R.A. Wilding

This is all the information to hand, that describes the last few days of Lieutenant Gordon's life. It is clear that he played a large part in keeping this stricken group of men together and had supported Captain Hosegood in a resolute manner. It also seems to be the case, that when the group needed to gather food, water or help from the various Burmese villages in the area, Lieutenant Gordon was the man they turned to.

Willie Wilding's letter describes the great hardship of those last fateful few weeks in and around the Nalo Chaung; hunger, thirst and at times sheer exhaustion harried the isolated Chindits as they tried in vain to cross the Irrawaddy. Not much is known about what happened to the men in Pat Gordon's boat on the 29th April. It seems likely that Lieutenant Gordon was killed outright during the crossing and that the same fate befell both Signalman Belchier and Lance Corporal Purdy. Burma Riflemen, Tunnion and Orlando tried to evade the Japanese after the ambush, but were captured and became prisoners of war, joining their comrade Jemadar Moody who was being held at Tigyaing at the time.

Moody, as mentioned by Lieutenant Wilding in his letter to Graham Hosegood's father, escaped later on after the Chindit POW's had been collected together and sent on to a concentration camp in the Burmese hill station town of Maymyo. He successfully rejoined his unit at Karachi in India, where they were enjoying a period of rest and recuperation, he later became involved in the preparations for Operation Thursday. Please see the report on those held at the Maymyo Camp in the final gallery of images below.

The eventual fate of Riflemen Tunnion and Orlando is not known, however, their names do not appear in any Longcloth casualty listings and to that end, I believe that they survived their time as prisoners of war and returned home to the Kachin Hills after liberation. Captain Hosegood and Lieutenant Wilding along with all the surviving Chindit POW's were taken down to Rangoon Central Jail during the latter weeks of May and the early weeks of June 1943. Willie Wilding was liberated from his Japanese captors close to the Burmese town of Pegu on the 29th April 1945, excruciatingly Graham Hosegood perished just a few short weeks before liberation, suffering from general ill health and exhaustion.

For more information about Captain Hosegood and the experiences of men who became prisoners of war in 1943, please click on the following links:

Graham Hosegood

Chindit POW's

6290071 Signalman Herbert Michael Belchier was the son of Thomas and Mary Belchier from Enfield in Middlesex. He had been a last minute reinforcement for Operation Longcloth, joining the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade on the 19th January 1943 as the unit moved down to Imphal in Assam. Herbert and around thirty other Signalmen were attached to Wingate's Brigade from their temporary base at Jhansi and had previously taken part in clandestine operations in the Yunnan Provinces of China, possibly as part of the 204 Military Mission.

6296508 Lance Corporal Leslie Albert Purdy was the son of Violet May Purdy from Walthamstow in Essex. Leslie, originally a soldier in the Buffs (East Kent Regiment) had joined 142 Commando on the 30th September 1942 at the Chindit training camp in Saugor. He was posted to Wingate's Head Quarters later that year. The CWGC have Leslie's date of death recorded as the 14th April 1943, however, all documents in relation to his disappearance on Operation Longcloth show his missing in action date as the 30th April. Fellow Commando, Pte. James Dixon gave a witness statement after his liberation from Rangoon Jail, stating that he last saw Lance Corporal Purdy on the 30th April attempting to cross the Irrawaddy, this backs up the information contained in Lieutenant Wilding's letter and almost certainly places James Dixon with Captain Hosegood's dispersal party.

Another member of Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters, Pte. George Walter Lee, gave a short witness statement in regards to Lance-Corporal Purdy and his last known movements in 1943. In a letter dated 6th November 1945, written to the Army Investigation Bureau for missing persons in Burma, he wrote:

6296508 Lance-Corporal L.A. Purdy

Sir, a Purdy was attached to my party of 26 when Brigadier Wingate split us up into small party's, but I do not know if it is the same one you mention. This man was in the 142 Commandos and was in Brigade Head Quarters. He was killed whilst trying to re-cross the Irrawaddy River with me. He is one of a few names I know here, the others died in Rangoon Jail, but I do not know all their numbers or regiment details.

Pte. Lee, was also a surviving POW from Rangoon Jail and went on to give many similar witness statements to the Investigation Bureau after his liberation in 1945.

Seen below are some final images in relation to the story of Lieutenant Robin Patrick Gordon. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, January 2015.