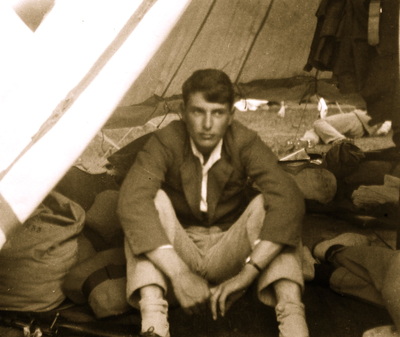

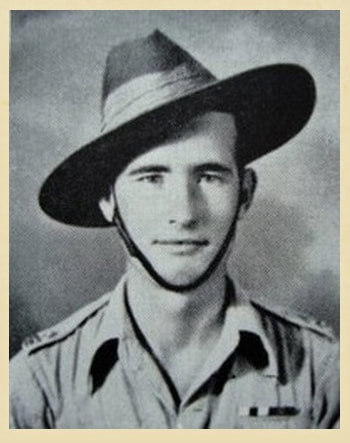

Lieutenant Victor St. George De La Rue

Lieut. Victor St. George De La Rue.

Lieut. Victor St. George De La Rue.

"The battalion left Jhansi for Imphal on the 9th January 1943. We travelled by rail, road and paddle steamer, in which the men were most interested. We finished the trip with ten consecutive night marches arriving at Imphal with the following British Officers:

Lieutenant-Colonel Alexandar

Major Conren

Captain Bertwhistle

Captain Smallwood

Lieutenant Dilarne

Major Dunlop

Captain Wetherall

Captain Emmet"

This was how Subedar-Major Siblal Thapa, the senior Gurkha Officer on Operation Longcloth, recalled the battalion's move up to the Assam/Burmese border in January 1943. The names of the British Officers held no surprises, but one name did catch my eye, that of Lieutenant Dilarne. This was a new man to my research and excitedly I attempted to trace his credentials. However, nothing was ever found.

Two years later, whilst cross-referencing a number of officers from 3/2 GR, I finally had my 'light-bulb' moment in regards to identity of Lieutenant Dilarne. Siblal Thapa had written down all the names phonetically, the way he had always heard them spoken. Dilarne was actually Lieutenant Victor St. George De La Rue.

Victor St. George de la Rue was born on the 20th August 1918 in the town of Hatfield in Hertfordshire. He was the son of Sir Evelyn and Lady Mary de la Rue, of Rusper in Sussex. St. George and his elder brother, Ian de la Rue, both studied at Eton College, before Ian left England for Southern Rhodesia in the early 1930's, eventually building a successful ranching business in the south eastern Lowveld. St. George, known affectionately as Alf by his older brother visited Rhodesia in 1936 and stayed at the family ranch called Devuli.

By this time Ian was looking to expand his empire and had planned an excursion to explore the area beyond the Bikita Mountains. Ian wrote about these experiences in his memoir entitled, 'The Early Days'. With the kind permission of Ian de la Rue's son, Anthony, there follows a short paraphrased extract from the memoir describing the expedition that Ian and St. George undertook in April 1936:

My brother St. George (he was so named as he was born within a few days of the victory in WW1) had recently left school in England, and had come out to visit me. The heavy rains of early 1936 had made all tracks into muddy bogs, and I waited to the end of April before attempting the journey from Devuli Ranch, where I had been working up until now. It would be impossible to cross the Chiredzi River for some considerable time, and I decided to try a little-used track on the east that wound through the Bikita Mountains before finally emerging into the Lowveld.

All the transport I possessed was a Chevrolet Imperial that carried 600 lbs in its back. I had my brother, my dog, Glen and everything I needed to take. This included a bag of meal for the labour, two picks, two shovels and two axes, all our cooking pots and bedding, petrol in 8 gallon cases, food, a tent, a rifle and some ammunition.

After an appalling journey we arrived early next day at the banks of the Chiredzi River. The river was in part flood, but we managed to wade through the swift current. We walked due east about twelve miles to see a good cross-section of the country, and swung around in a circle having covered some thirty miles back to our starting point. By then evening was falling and light drizzle set in.

We were alarmed at the considerable rise in the level of the flooded river, and I was nearly washed off my feet before I had started properly to try the depth and speed of the water. There was only one hope, to walk upstream four miles where there was a wider crossing. The drizzle worsened and total darkness had taken over. We could hardly follow the tracks in the road by the feel of our feet. In what seemed an eternity of time, we at last came to the crossing. There was a section of crossing that we knew would be sluggish for about 30 yards, at which point there was a flat outcrop. The river was roaring ominously ahead, so we let off two shots with our rifles to scare off any crocodiles, and I told my brother to stay on the rock while I attempted the raging waters. Somehow I traversed the 30 yards to the other bank safely, though on a number of occasions I was nearly washed down.

The awful thought was that I now must repeat the performance to return to collect my brother, who I thought must be all right. But it was worse for him waiting and not knowing what had happened, than for me who was in the thick of it. The river was roaring so much that shouting would have been useless. We did in fact make it safely across, and later, were glad to be under the roof of local area manager Mr Buchanan. As we ate an enormous meal and recounted our story, he told us our enemy was not the crocs, but the hippos. There was a big school in an enormous pool nearby, with several very crusty males who always exercised their right of way at night.

Ian and St. George succeeded in their quest for new territory and established what was to become the Ruware Ranch. Later in his memoir Ian remembered putting his brother on a train to Biera, the shipping port facing the island of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean and from there he sailed back to England. Rather poignantly, this was to be the last time he ever saw St. George.

Roughly four years later and with the coming of war, St. George was commissioned into the British Army, joining the King's Royal Rifle Corps on the 29th October 1940. He then took up a posting to India, where he transferred into the 3rd Battalion of the 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles. I have no accurate timescale for St. George joining the battalion, but by the summer of 1942 he and his Gurkhas had become one-half of the infantry complement for the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade and had begun their Chindit training at Saugor.

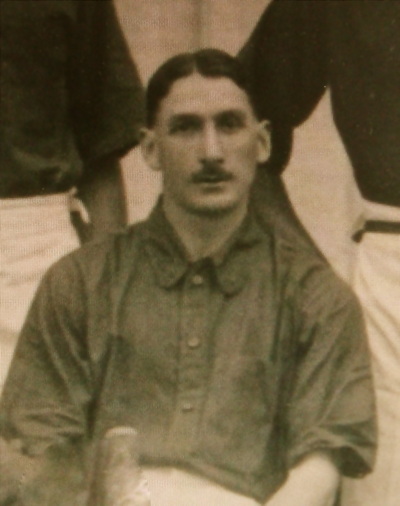

Seen below is a gallery of photographs depicting St. George's time in Rhodesia and his early life in the Army, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Lieutenant-Colonel Alexandar

Major Conren

Captain Bertwhistle

Captain Smallwood

Lieutenant Dilarne

Major Dunlop

Captain Wetherall

Captain Emmet"

This was how Subedar-Major Siblal Thapa, the senior Gurkha Officer on Operation Longcloth, recalled the battalion's move up to the Assam/Burmese border in January 1943. The names of the British Officers held no surprises, but one name did catch my eye, that of Lieutenant Dilarne. This was a new man to my research and excitedly I attempted to trace his credentials. However, nothing was ever found.

Two years later, whilst cross-referencing a number of officers from 3/2 GR, I finally had my 'light-bulb' moment in regards to identity of Lieutenant Dilarne. Siblal Thapa had written down all the names phonetically, the way he had always heard them spoken. Dilarne was actually Lieutenant Victor St. George De La Rue.

Victor St. George de la Rue was born on the 20th August 1918 in the town of Hatfield in Hertfordshire. He was the son of Sir Evelyn and Lady Mary de la Rue, of Rusper in Sussex. St. George and his elder brother, Ian de la Rue, both studied at Eton College, before Ian left England for Southern Rhodesia in the early 1930's, eventually building a successful ranching business in the south eastern Lowveld. St. George, known affectionately as Alf by his older brother visited Rhodesia in 1936 and stayed at the family ranch called Devuli.

By this time Ian was looking to expand his empire and had planned an excursion to explore the area beyond the Bikita Mountains. Ian wrote about these experiences in his memoir entitled, 'The Early Days'. With the kind permission of Ian de la Rue's son, Anthony, there follows a short paraphrased extract from the memoir describing the expedition that Ian and St. George undertook in April 1936:

My brother St. George (he was so named as he was born within a few days of the victory in WW1) had recently left school in England, and had come out to visit me. The heavy rains of early 1936 had made all tracks into muddy bogs, and I waited to the end of April before attempting the journey from Devuli Ranch, where I had been working up until now. It would be impossible to cross the Chiredzi River for some considerable time, and I decided to try a little-used track on the east that wound through the Bikita Mountains before finally emerging into the Lowveld.

All the transport I possessed was a Chevrolet Imperial that carried 600 lbs in its back. I had my brother, my dog, Glen and everything I needed to take. This included a bag of meal for the labour, two picks, two shovels and two axes, all our cooking pots and bedding, petrol in 8 gallon cases, food, a tent, a rifle and some ammunition.

After an appalling journey we arrived early next day at the banks of the Chiredzi River. The river was in part flood, but we managed to wade through the swift current. We walked due east about twelve miles to see a good cross-section of the country, and swung around in a circle having covered some thirty miles back to our starting point. By then evening was falling and light drizzle set in.

We were alarmed at the considerable rise in the level of the flooded river, and I was nearly washed off my feet before I had started properly to try the depth and speed of the water. There was only one hope, to walk upstream four miles where there was a wider crossing. The drizzle worsened and total darkness had taken over. We could hardly follow the tracks in the road by the feel of our feet. In what seemed an eternity of time, we at last came to the crossing. There was a section of crossing that we knew would be sluggish for about 30 yards, at which point there was a flat outcrop. The river was roaring ominously ahead, so we let off two shots with our rifles to scare off any crocodiles, and I told my brother to stay on the rock while I attempted the raging waters. Somehow I traversed the 30 yards to the other bank safely, though on a number of occasions I was nearly washed down.

The awful thought was that I now must repeat the performance to return to collect my brother, who I thought must be all right. But it was worse for him waiting and not knowing what had happened, than for me who was in the thick of it. The river was roaring so much that shouting would have been useless. We did in fact make it safely across, and later, were glad to be under the roof of local area manager Mr Buchanan. As we ate an enormous meal and recounted our story, he told us our enemy was not the crocs, but the hippos. There was a big school in an enormous pool nearby, with several very crusty males who always exercised their right of way at night.

Ian and St. George succeeded in their quest for new territory and established what was to become the Ruware Ranch. Later in his memoir Ian remembered putting his brother on a train to Biera, the shipping port facing the island of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean and from there he sailed back to England. Rather poignantly, this was to be the last time he ever saw St. George.

Roughly four years later and with the coming of war, St. George was commissioned into the British Army, joining the King's Royal Rifle Corps on the 29th October 1940. He then took up a posting to India, where he transferred into the 3rd Battalion of the 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles. I have no accurate timescale for St. George joining the battalion, but by the summer of 1942 he and his Gurkhas had become one-half of the infantry complement for the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade and had begun their Chindit training at Saugor.

Seen below is a gallery of photographs depicting St. George's time in Rhodesia and his early life in the Army, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

3/2 Gurkha Rifles had been based at Loralai, a town close to the Northwest Frontier of India, which today falls within the borders of Pakistan. After receiving the call from Wingate, the battalion moved across to Saugor in the Central Provinces of India and set up camp at a place called Ramna. Lieutenant de la Rue may well have had a sense of deja vu at this moment, as the river running through the camp was in spate and swept away much of the battalion's equipment, forcing many of the men to seek sanctuary in the nearby trees.

After this difficult beginning the Gurkhas soon settled into their new role as a long range penetration force. Some aspects of Wingate's philosophy did not come naturally to the men from Nepal, but they adapted quickly to these new ideas and slowly grew in confidence. The majority of the Gurkha Battalion formed Southern Group within 77th Brigade, comprising of two column units and a Brigade Head Quarters. St. George was given the role of Intelligence Officer in Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander's Brigade HQ and from that moment on they were to share an almost inseparable Chindit journey. To read more about Colonel Alexander, please click on the following link: L.A. Alexander

Southern Group was used by Wingate as a decoy on Operation Longcloth, the intention being for Alexander's men to draw attention away from the main Chindit columns of Northern Group whilst they crossed the Chindwin River and moved quickly east toward their targets along the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway.

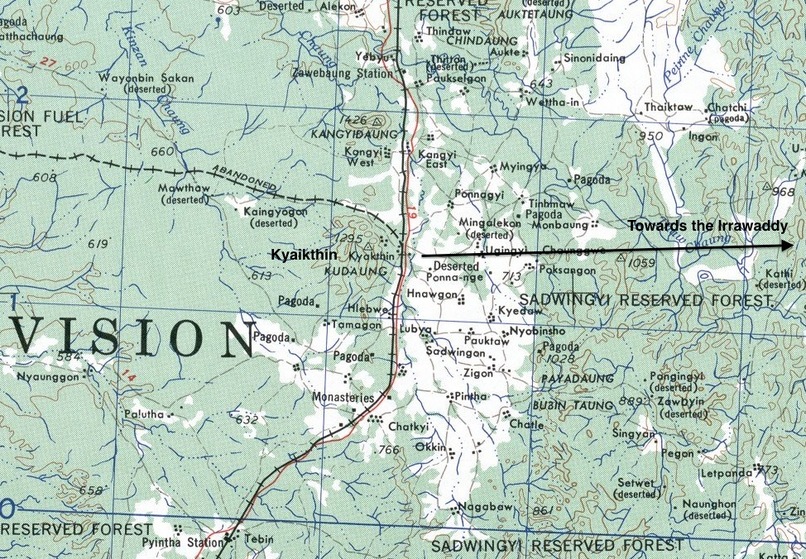

Southern Group crossed the Chindwin on 15/16th February 1943 at a place called Auktang. Their orders were to march toward their own prime objective, the rail station at Kyaikthin. They marched openly along well known local trails and paths and also received a large supply drop from the air, which must have announced their presence in the area to the Japanese. The decoy group were accompanied at this time by a Company of Sikh Mountain Artillery and a section of Seaforth Highlanders. This supplementary unit were to create a further diversion for Wingate by attacking the town of Pantha, alerting the enemy to the possibility that there might well be a full-scale re-invasion taking place. To all intents and purposes these tactics succeeded and Northern Group did proceed unmolested toward their objectives.

On the 2nd March Columns 1 and 2 had reached the outskirts of Kyaikthin, Major George Dunlop, commander of Chindit Column 1 was given the order to blow up the railway bridge, whilst Column 2 under the command of Major Arthur Emmett along with Alexander's Group HQ were to head on towards the rail station itself. What neither group realised was that the Japanese had by now closed in on the unsuspecting Chindits and lay in wait just a short way up the tracks.

To make matters worse the two Gurkha columns had also now lost radio contact. Column 2 and Group Head Quarters, in the black of night stumbled into the enemy ambush which straddled both sides of the railway embankment. Here is how Lieutenant Ian MacHorton, a young subaltern with Column 2 remembered that moment:

"We shuffled to a halt as the guides probed forward. There came the sound of just one bang up front, then an inferno of noise engulfed the world around me. There came the high-pitched staccato scream of a machine gun, then overwhelmingly many others joined in, the crash and ping of rifle bullets, the banging of grenades as the battle reached a fearful crescendo. Men and mules were lying, twisted and contorted, twitching and writhing, others were still erect, stark in the moonlight, heaving and jerking in the midst of this chaos. Then a sinister scuffling noise made by men of all kinds in close combat. The close combat of bayonet and kukri, the fanatical, personal slaughter with blood-dripping cold steel."

Colonel Alexander managed to extract the majority of his Head Quarters from the chaos and devastation at Kyaikthin, he decided to lead them away to the agreed rendezvous point a few miles further east. His decision to keep to the pre-operational plan and move on toward the Irrawaddy River clearly showed his determination to carry out Wingate's orders and to test the theories of dispersal under enemy fire. He could easily have chosen to turn around west and return to the safety of the Chindwin.

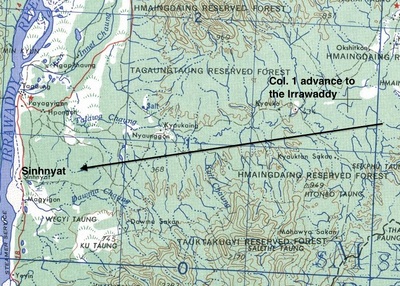

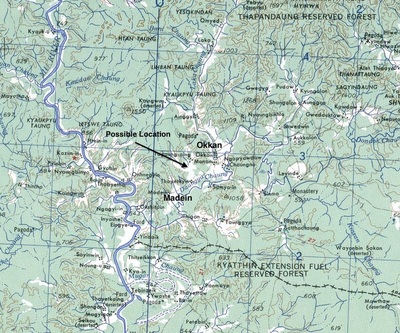

Seen below is a map of the area around the town of Kyaikthin and the direction of Alexander's march away from the Japanese ambush on the railway.

After this difficult beginning the Gurkhas soon settled into their new role as a long range penetration force. Some aspects of Wingate's philosophy did not come naturally to the men from Nepal, but they adapted quickly to these new ideas and slowly grew in confidence. The majority of the Gurkha Battalion formed Southern Group within 77th Brigade, comprising of two column units and a Brigade Head Quarters. St. George was given the role of Intelligence Officer in Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander's Brigade HQ and from that moment on they were to share an almost inseparable Chindit journey. To read more about Colonel Alexander, please click on the following link: L.A. Alexander

Southern Group was used by Wingate as a decoy on Operation Longcloth, the intention being for Alexander's men to draw attention away from the main Chindit columns of Northern Group whilst they crossed the Chindwin River and moved quickly east toward their targets along the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway.

Southern Group crossed the Chindwin on 15/16th February 1943 at a place called Auktang. Their orders were to march toward their own prime objective, the rail station at Kyaikthin. They marched openly along well known local trails and paths and also received a large supply drop from the air, which must have announced their presence in the area to the Japanese. The decoy group were accompanied at this time by a Company of Sikh Mountain Artillery and a section of Seaforth Highlanders. This supplementary unit were to create a further diversion for Wingate by attacking the town of Pantha, alerting the enemy to the possibility that there might well be a full-scale re-invasion taking place. To all intents and purposes these tactics succeeded and Northern Group did proceed unmolested toward their objectives.

On the 2nd March Columns 1 and 2 had reached the outskirts of Kyaikthin, Major George Dunlop, commander of Chindit Column 1 was given the order to blow up the railway bridge, whilst Column 2 under the command of Major Arthur Emmett along with Alexander's Group HQ were to head on towards the rail station itself. What neither group realised was that the Japanese had by now closed in on the unsuspecting Chindits and lay in wait just a short way up the tracks.

To make matters worse the two Gurkha columns had also now lost radio contact. Column 2 and Group Head Quarters, in the black of night stumbled into the enemy ambush which straddled both sides of the railway embankment. Here is how Lieutenant Ian MacHorton, a young subaltern with Column 2 remembered that moment:

"We shuffled to a halt as the guides probed forward. There came the sound of just one bang up front, then an inferno of noise engulfed the world around me. There came the high-pitched staccato scream of a machine gun, then overwhelmingly many others joined in, the crash and ping of rifle bullets, the banging of grenades as the battle reached a fearful crescendo. Men and mules were lying, twisted and contorted, twitching and writhing, others were still erect, stark in the moonlight, heaving and jerking in the midst of this chaos. Then a sinister scuffling noise made by men of all kinds in close combat. The close combat of bayonet and kukri, the fanatical, personal slaughter with blood-dripping cold steel."

Colonel Alexander managed to extract the majority of his Head Quarters from the chaos and devastation at Kyaikthin, he decided to lead them away to the agreed rendezvous point a few miles further east. His decision to keep to the pre-operational plan and move on toward the Irrawaddy River clearly showed his determination to carry out Wingate's orders and to test the theories of dispersal under enemy fire. He could easily have chosen to turn around west and return to the safety of the Chindwin.

Seen below is a map of the area around the town of Kyaikthin and the direction of Alexander's march away from the Japanese ambush on the railway.

Within a few days (about the 7th March) Group Head Quarters with the survivors from Column 2 had met up once more with George Dunlop and his men. Together they crossed the Irrawaddy River. Southern Group now found themselves the most easterly placed Chindit unit and by that nature the furthest from the safety of India. All remaining Chindit columns were now over the Irrawaddy and placed in a natural box contained on two sides by the Shweli and Irrawaddy Rivers, the force was trapped and slowly the Japanese began to close in.

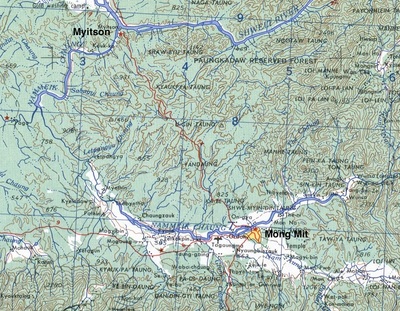

Back in India, 4 Corps HQ in conversation with Wingate decided it was time to recall the Brigade and the dispersal signal was given to all columns in late March. Alexander had a very clear vision in his mind at this point; to return his group back to India in one piece and as one unit. However, after several days attempting to avoid contact with the Japanese on the Mongmit/Myitson Road, the Colonel reluctantly agreed to jettison the majority of his mules and all of the heavy arms and equipment. The men again met with disaster on April 6th when they arrived late at a supply drop location, only to see the planes heading back to India still fully laden. Alexander held an officers conference, where the decision was made to head north and attempt to reach the Allied held outpost of Fort Hertz.

By the 10th April the group had reached the banks of the fast flowing Shweli River. Some other Chindit columns had managed to cross at various points roughly one week before, but the Gurkhas of Southern Group struggled, losing several men in two aborted attempts to reach the north bank. Amongst the casualties on April 10th was Vivian Stuart Weatherall, who had been the officer in charge of Column 1 before Major Dunlop's arrival at Saugor, he was very much loved by his Gurkha soldiers and his death was a massive blow to their morale.

Failure to cross the Shweli cost the group their chance of reaching Fort Hertz and under some considerable pressure, Colonel Alexander reluctantly agreed to change course and head directly west for India. It was during this period that the party, now numbering some 480 men began to show signs of fatigue, this of course was mainly due to the lack of decent rations and availability of good drinking water, but general discipline had fallen away quite dramatically too. The young Gurkhas were constantly on edge, reacting to any jungle noise with undue alarm and expecting an ambush around every corner.

Yet again the men faced the obstacle of the mile wide Irrawaddy River, with the help of local boats the ailing Gurkhas managed to scramble over in groups of 30 at a time near the village of Sinhnyat. Even here the tail of the column was attacked by a Japanese patrol, resulting in many casualties. Morale was now at an all time low and group decisions had become difficult and contested. Major Dunlop's influence seemed to be shaping group plans much more now and I wonder whether the strain of command and Colonel Alexander's age (45 years) became a factor at this juncture.

Seen below is a gallery containing more maps illustrating the progress of Column 1 on the return journey to India. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Back in India, 4 Corps HQ in conversation with Wingate decided it was time to recall the Brigade and the dispersal signal was given to all columns in late March. Alexander had a very clear vision in his mind at this point; to return his group back to India in one piece and as one unit. However, after several days attempting to avoid contact with the Japanese on the Mongmit/Myitson Road, the Colonel reluctantly agreed to jettison the majority of his mules and all of the heavy arms and equipment. The men again met with disaster on April 6th when they arrived late at a supply drop location, only to see the planes heading back to India still fully laden. Alexander held an officers conference, where the decision was made to head north and attempt to reach the Allied held outpost of Fort Hertz.

By the 10th April the group had reached the banks of the fast flowing Shweli River. Some other Chindit columns had managed to cross at various points roughly one week before, but the Gurkhas of Southern Group struggled, losing several men in two aborted attempts to reach the north bank. Amongst the casualties on April 10th was Vivian Stuart Weatherall, who had been the officer in charge of Column 1 before Major Dunlop's arrival at Saugor, he was very much loved by his Gurkha soldiers and his death was a massive blow to their morale.

Failure to cross the Shweli cost the group their chance of reaching Fort Hertz and under some considerable pressure, Colonel Alexander reluctantly agreed to change course and head directly west for India. It was during this period that the party, now numbering some 480 men began to show signs of fatigue, this of course was mainly due to the lack of decent rations and availability of good drinking water, but general discipline had fallen away quite dramatically too. The young Gurkhas were constantly on edge, reacting to any jungle noise with undue alarm and expecting an ambush around every corner.

Yet again the men faced the obstacle of the mile wide Irrawaddy River, with the help of local boats the ailing Gurkhas managed to scramble over in groups of 30 at a time near the village of Sinhnyat. Even here the tail of the column was attacked by a Japanese patrol, resulting in many casualties. Morale was now at an all time low and group decisions had become difficult and contested. Major Dunlop's influence seemed to be shaping group plans much more now and I wonder whether the strain of command and Colonel Alexander's age (45 years) became a factor at this juncture.

Seen below is a gallery containing more maps illustrating the progress of Column 1 on the return journey to India. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

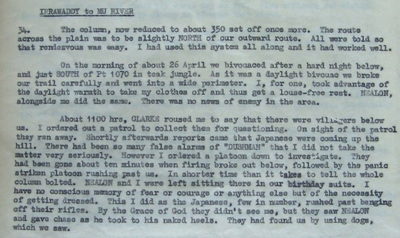

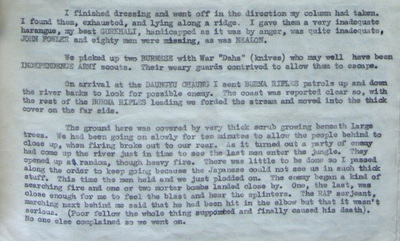

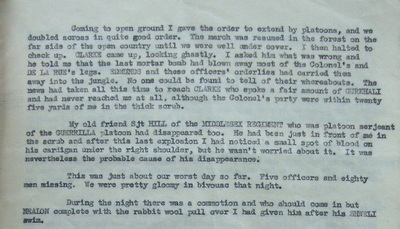

On the morning of the 26th April the party bivouacked in the teak forest south of Map Point 1070, close to the Mu River. The group were now some 350 in number and were roughly speaking re-tracing their outbound steps. George Dunlop takes up the story:

"At about 1100 hours, Lieutenant Clarke roused me to say that there were villagers below us. I ordered out a patrol to collect them for questioning. On sight of the patrol they ran away. After a short while reports came back that there were Japanese coming up the hill. I did not take this too seriously at first, but it did turn out to be true, the next thing I saw was my Gurkha patrol running past me."

In the confusion both Gurkha Rifles and enemy troops had raced past the unsuspecting commander and chaos ensued. After things had settled down somewhat, Dunlop collected what men he could find and decided to move forward toward the nearby chaung or stream. Several of his officers were now missing from the main party. With the Burma Rifle Scouts now leading, the group pushed into some thick scrub on the other side of the chaung, for ten minutes or so they moved slowly forward in the hope that the missing men might catch up, suddenly firing broke out to the rear. George Dunlop continues:

"As it turned out a party of the enemy had come up the river just in time to see the last of our men enter the jungle. They opened up at random, though with heavy fire. I gave the order for everyone to keep moving. The enemy began a sort of searching fire and several mortar bombs landed nearby. One landed so close I could feel the blast and hear the splinters, a RAF Sergeant marching next to me was hit.

Coming to open ground I gave the order to extend by platoons and we doubled across in quite good order. After reaching good cover on the other side I halted to check up on things. It was then that Clarke came up to me looking ghastly. I asked him what was wrong and he told me that the last mortar bomb had blown away most of the Colonel's and officer De La Rue's legs. Flight-Lieutenant Edmonds (RAF Liaison officer) and some orderlies had carried them away into the jungle, but that no one could now be found who knew of their whereabouts. The news had taken all this time to reach Clarke who spoke a fair amount of Gurkhali, and had never reached me at all, although the Colonel's party were within twenty five yards of me in the thick scrub.

My old friend Sergeant Hill of the Middlesex Regiment, had been hit too and had now disappeared. This was just about our worst day so far. Five officers and 80 men missing. We were pretty gloomy in bivouac that night."

An unofficial version of the above story has been muted; that suggests that Colonel Alexander was left mortally wounded by the chaung as his Gurkhas ran past, leaving only Lieutenant de la Rue and Flight-Lieutenant Edmonds to attend to the stricken commander. In any case, it is indisputable that St. George had remained with and supported Colonel Alexander at this horrific moment and that his actions had sadly resulted in his own demise.

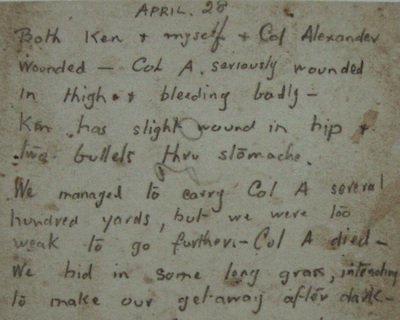

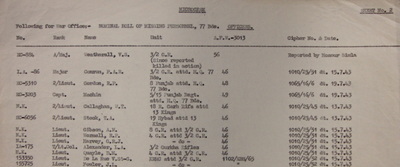

Seen below is another gallery containing the entries from Major Dunlop's Longcloth diary for the 26th April 1943. Also shown is a map of the area around Okkan village, close to where Colonel Alexander and St. George fell and a note written by Flight-Lieutenant Edmonds whilst a POW, recalling the final moments of Colonel Alexander's life. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

"At about 1100 hours, Lieutenant Clarke roused me to say that there were villagers below us. I ordered out a patrol to collect them for questioning. On sight of the patrol they ran away. After a short while reports came back that there were Japanese coming up the hill. I did not take this too seriously at first, but it did turn out to be true, the next thing I saw was my Gurkha patrol running past me."

In the confusion both Gurkha Rifles and enemy troops had raced past the unsuspecting commander and chaos ensued. After things had settled down somewhat, Dunlop collected what men he could find and decided to move forward toward the nearby chaung or stream. Several of his officers were now missing from the main party. With the Burma Rifle Scouts now leading, the group pushed into some thick scrub on the other side of the chaung, for ten minutes or so they moved slowly forward in the hope that the missing men might catch up, suddenly firing broke out to the rear. George Dunlop continues:

"As it turned out a party of the enemy had come up the river just in time to see the last of our men enter the jungle. They opened up at random, though with heavy fire. I gave the order for everyone to keep moving. The enemy began a sort of searching fire and several mortar bombs landed nearby. One landed so close I could feel the blast and hear the splinters, a RAF Sergeant marching next to me was hit.

Coming to open ground I gave the order to extend by platoons and we doubled across in quite good order. After reaching good cover on the other side I halted to check up on things. It was then that Clarke came up to me looking ghastly. I asked him what was wrong and he told me that the last mortar bomb had blown away most of the Colonel's and officer De La Rue's legs. Flight-Lieutenant Edmonds (RAF Liaison officer) and some orderlies had carried them away into the jungle, but that no one could now be found who knew of their whereabouts. The news had taken all this time to reach Clarke who spoke a fair amount of Gurkhali, and had never reached me at all, although the Colonel's party were within twenty five yards of me in the thick scrub.

My old friend Sergeant Hill of the Middlesex Regiment, had been hit too and had now disappeared. This was just about our worst day so far. Five officers and 80 men missing. We were pretty gloomy in bivouac that night."

An unofficial version of the above story has been muted; that suggests that Colonel Alexander was left mortally wounded by the chaung as his Gurkhas ran past, leaving only Lieutenant de la Rue and Flight-Lieutenant Edmonds to attend to the stricken commander. In any case, it is indisputable that St. George had remained with and supported Colonel Alexander at this horrific moment and that his actions had sadly resulted in his own demise.

Seen below is another gallery containing the entries from Major Dunlop's Longcloth diary for the 26th April 1943. Also shown is a map of the area around Okkan village, close to where Colonel Alexander and St. George fell and a note written by Flight-Lieutenant Edmonds whilst a POW, recalling the final moments of Colonel Alexander's life. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Flight-Lieutenant John Kingsley Edmonds and the other men assisting him carried the bodies of Colonel Alexander and Lieutenant de la Rue into the wooded scrubland close to the chaung. It is not really known if Edmonds had the time to bury the two casualties, or that he simply hid their bodies in the thick-set scrub. Edmonds and his RAF Sergeant, Kenneth Wyse then hid out until dark, before moving off again in a westerly direction. Both men had been wounded and sadly they soon fell into Japanese hands.

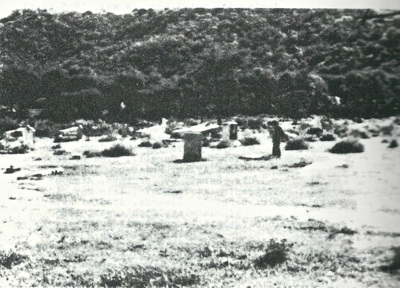

John Edmonds kept a diary during his time as a prisoner of war, he used any scrap paper he could find including some postcards belonging to Sergeant Wyse to record his experiences (see image in the gallery above). In regards to the location of Alexander and de la Rue's graves, presumably Edmonds, either saved the co-ordinates during his time in Rangoon Jail and handed over the information after his liberation in April 1945, or had passed on these details to a man who had managed to return to India after the operation in 1943. In any case, details were kept and in April 1946 the Army Graves Search Team located two graves near the village of Okkan close to the eastern banks of the Mu River.

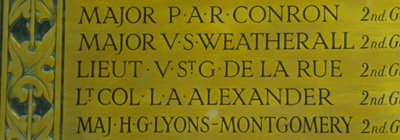

Even after their tragic death in April 1943, the two soldiers could not be separated. The intervening years made it impossible for the Graves Commission to accurately identify the remains of either man and so, just as they had been in 1943, the two comrades were re-interred in joint grave 45-46, Plot 2, Row H at the Mandalay Military Cemetery. Eventually in 1951 the Imperial War Graves Commission moved many of the burials from around Burma to the newly constructed Taukkyan War Cemetery, situated twenty or so miles north of Rangoon. St. George and Colonel Alexander were finally laid to rest at Taukkyan in joint grave 19.G.1-2.

The clandestine nature of the first Chindit Operation and the high number of casualties suffered, meant that information available to families in regards to their loved ones fate was scant and often unreliable. I know for instance, that although my own grandfather was captured by the Japanese in May 1943 and perished as a prisoner of war in Rangoon Jail four weeks later, my Nan did not receive confirmation or details about his demise until late 1945. After hearing of his disappearance St. George's mother, Lady Mary de la Rue, set out on her own personal quest to find out what had happened to her son.

After having little joy in the latter months of 1943 and failing to gather any real information from the Gurkha Regimental Centre at Dehra Dun, Lady Mary decided to post an advert in The Times asking for details about St. George and his time in Burma. From the pages of the newspaper printed on Tuesday 15th February 1944:

Missing

De la Rue--- Reported missing, April 1943 in the Far East. Lieutenant Victor St. George De La Rue, of the 60th Rifles, youngest son of Sir Evelyn and Lady de la Rue of Normans, Rusper in Sussex. Any information gratefully received by his parents.

How successful this advertisement was is not known, but Lady de la Rue did not give up her quest. Shortly after the war, another participant of Operation Longcloth made it his business to visit Lady de la Rue at her home in Rusper. Pte. Frank Holland, a soldier with 8 Column in 1943 relayed as much detail as he could about the expedition in general and any information he had concerning St. George. Lady Mary must have been very grateful for this news and repaid Frank Holland's kind gesture by offering the returning Chindit a job on her estate.

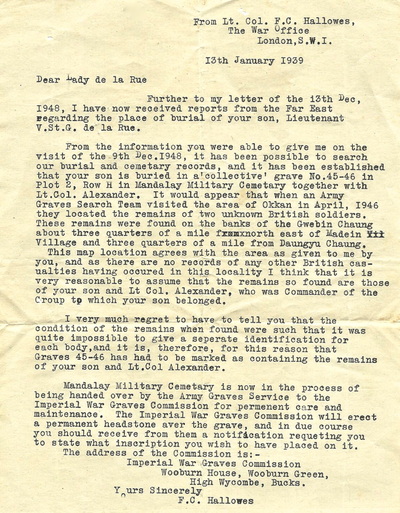

In early 1949 her persistence was finally rewarded when a letter arrived from the War Office, informing Lady de la Rue of the last known whereabouts of St. George and Colonel Alexander in 1943 and their burials at both Okkan and then Mandalay. I sincerely hope that this news, however difficult to hear, would have provided Lady Mary with some form of closure in relation to the fate of her youngest son. A few years later she was able to choose the words for St. George's epitaph, written upon his grave plaque at Taukkyan War Cemetery.

'A Hero's Death He Died To Save His Fellow Men. Loved By All Who Knew Him'

Seen below is a final gallery of images in relation to this story. These include all known memorials for St. George and the War Office letter sent to Lady de la Rue in January 1949. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

John Edmonds kept a diary during his time as a prisoner of war, he used any scrap paper he could find including some postcards belonging to Sergeant Wyse to record his experiences (see image in the gallery above). In regards to the location of Alexander and de la Rue's graves, presumably Edmonds, either saved the co-ordinates during his time in Rangoon Jail and handed over the information after his liberation in April 1945, or had passed on these details to a man who had managed to return to India after the operation in 1943. In any case, details were kept and in April 1946 the Army Graves Search Team located two graves near the village of Okkan close to the eastern banks of the Mu River.

Even after their tragic death in April 1943, the two soldiers could not be separated. The intervening years made it impossible for the Graves Commission to accurately identify the remains of either man and so, just as they had been in 1943, the two comrades were re-interred in joint grave 45-46, Plot 2, Row H at the Mandalay Military Cemetery. Eventually in 1951 the Imperial War Graves Commission moved many of the burials from around Burma to the newly constructed Taukkyan War Cemetery, situated twenty or so miles north of Rangoon. St. George and Colonel Alexander were finally laid to rest at Taukkyan in joint grave 19.G.1-2.

The clandestine nature of the first Chindit Operation and the high number of casualties suffered, meant that information available to families in regards to their loved ones fate was scant and often unreliable. I know for instance, that although my own grandfather was captured by the Japanese in May 1943 and perished as a prisoner of war in Rangoon Jail four weeks later, my Nan did not receive confirmation or details about his demise until late 1945. After hearing of his disappearance St. George's mother, Lady Mary de la Rue, set out on her own personal quest to find out what had happened to her son.

After having little joy in the latter months of 1943 and failing to gather any real information from the Gurkha Regimental Centre at Dehra Dun, Lady Mary decided to post an advert in The Times asking for details about St. George and his time in Burma. From the pages of the newspaper printed on Tuesday 15th February 1944:

Missing

De la Rue--- Reported missing, April 1943 in the Far East. Lieutenant Victor St. George De La Rue, of the 60th Rifles, youngest son of Sir Evelyn and Lady de la Rue of Normans, Rusper in Sussex. Any information gratefully received by his parents.

How successful this advertisement was is not known, but Lady de la Rue did not give up her quest. Shortly after the war, another participant of Operation Longcloth made it his business to visit Lady de la Rue at her home in Rusper. Pte. Frank Holland, a soldier with 8 Column in 1943 relayed as much detail as he could about the expedition in general and any information he had concerning St. George. Lady Mary must have been very grateful for this news and repaid Frank Holland's kind gesture by offering the returning Chindit a job on her estate.

In early 1949 her persistence was finally rewarded when a letter arrived from the War Office, informing Lady de la Rue of the last known whereabouts of St. George and Colonel Alexander in 1943 and their burials at both Okkan and then Mandalay. I sincerely hope that this news, however difficult to hear, would have provided Lady Mary with some form of closure in relation to the fate of her youngest son. A few years later she was able to choose the words for St. George's epitaph, written upon his grave plaque at Taukkyan War Cemetery.

'A Hero's Death He Died To Save His Fellow Men. Loved By All Who Knew Him'

Seen below is a final gallery of images in relation to this story. These include all known memorials for St. George and the War Office letter sent to Lady de la Rue in January 1949. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

In mid-November 2013 I had the good fortune to receive an email contact via my website from Thomas de la Rue, a great nephew of St. George.

This is what Thomas had to say:

I am Lieutenant Colonel Thomas de la Rue. My great uncle was Lt. Victor St. George de la Rue of the King's Royal Rifle Corps, who was killed alongside Lt. Col. Alexander during the first Chindit expedition in April 1943. I wondered whether you have any information that you could pass on to me about my great uncle. I notice that you have a photograph of Lt. Col. Alexander's grave stone in the Taukkyan War Cemetery, and hoped that you might also have a picture of Lt. de la Rue's headstone as they were buried in the same grave, reference 19. G. 1-2.

Interestingly, even six years after St. George’s death, his mother (Lady Mary de la Rue) was still trying to find out what had happened to him in Burma. Evidently, it was Lady de la Rue who chose the very poignant words seen upon St. George's gravestone at Taukkyan. As an aside, and a point worth pondering, I suspect that St. George’s expeditionary/pioneering activities with his older brother in Rhodesia may well have provided the catalyst and inspiration for his enthusiasm to volunteer for the First Chindit Expedition.

After replying to Tom's email and supplying him with all the information I had to hand about his great uncle; he again replied:

Dear Steve

You are very kind for having put all of this together for my father and I. We are both tremendously grateful for your efforts. St. George achieved so much in his very short life and I am very glad we now know so much more about his final moments with Colonel Alexander.

We were astounded to hear that the War Office letter could provide the Colonel's own family with a vital missing link and therefore absolutely agree that the information should be passed to them. They might also like to see a photograph of the twenty-four year old Intelligence Officer buried with his Commanding Officer. St George's time in Burma has remained a little vague for us all - until now.

Thank you again for your considerable efforts.

A short time later I was pleased to receive an email from Tom's father, Anthony de la Rue:

Dear Steve

The information you have unearthed is indeed an extraordinary story and fills so many gaps for our family history. There is so much material here that it will take some time to assimilate it all. The recording by Lieutenant Dominic Neill is extraordinary in its content and clarity.

St. George joined his older brother, my father Ian de la Rue in 1936 in Rhodesia and helped him to set up the ranch which was my home. They pioneered in true style as you can see from the photo of St. George the day they set out with their worldly belongings in the back of my father's old Chevrolet, with the attendant dog on top.

St. George was very close to my father and my regret is that my father never knew what we know today thanks largely to your efforts. All he used to tell me was that his brother was killed in Burma with the Chindits and he was aware that he had remained with his CO who had been badly wounded and they died together. I found the letter to my grandmother amongst my fathers papers, so he must have known as much as is written there, namely that they were buried together after their remains were located, but could not be distinguished from each other. It is so tragic that the calamity of war can cut short a young life of such promise.

Anyway we are all the richer for knowing these things, and I imagine it must be exciting for you when, like now, so much suddenly comes together and missing links are found which connect the whole. What I find exciting myself is that the family of Colonel Alexander will, through all this, discover some of their own long forgotten past. I will be very interested in what transpires in your communications with them. By all means put them in communication with Thomas and myself if they wish, as we now know we are forever bound by a common grave.

For your general interest, I attach a short story my father wrote of his early life in Rhodesia, in which he mentioned St. George. Also attached is a picture of my father at about that time. As Thomas surmises, it was probably the experience with my father in the wilds of the Rhodesian Lowveld, that led St. George to look for an unconventional life in the British Army.

Best wishes. Anthony

My good fortune continued in July 2014, when I received an email from another member of the wider de la Rue family. Dave Grantham, who lives in New Zealand told me:

My father's first cousin was Victor St. George de la Rue. My grandmother Sybil Grantham (nee de la Rue) was St George's Aunt. I randomly typed “de la Rue Chindit" into Google and the search came up with your website. My own father lost six relations in WW1 and WW2: three cousins, an uncle, a brother and a nephew, so a few years ago, I set out to find more about the six of them. St. George was the one I knew least about, just that he was a Chindit.

At that time, I was looking through a secondhand bookshop in Wellington and came across Bernard Fergusson’s book Beyond the Chindwin. I was delighted to see the de la Rue name in the index. When Fergusson’s son George was High Commissioner to New Zealand I wrote to him and told him of my connection and got a nice letter in reply.

I read a number of other books including Ian MacHorton’s Safer than a Known Way and came to the same conclusion that you did, that St. George was the other man killed with Leigh Alexander, particularly when I found out later they were buried in a joint grave. I’m not sure if I’ve got this right but I think the CWGC told me that after initial burial, they had been transferred to the Mandalay War Cemetery and finally to Taukkyan in Rangoon. Presumably Leigh Alexander and St. George are in a joint grave because they couldn’t identify who was who when they exhumed the bodies.

I was particularly delighted you sent over a photo of St. George’s grave which I hadn't seen and thank you for the link to the CWGC site.

I have visited three war graves of my relations, but have yet to visit Rangoon to see St. George's.

Many thanks. Dave

I would like to take this opportunity to thank all three gentlemen for their invaluable contributions to this story. Anthony mentioned in his email a recording made by Lieutenant Dominic Neill, who served with Chindit Column 8 on Operation Longcloth. In this recording Neill recalls some of the 3/2 Gurkha Officers killed during the first Chindit expedition including Lieutenant de la Rue and Colonel Alexander. Here is a very short extract from his audio memoir:

Now the 3rd battalion as a whole had taken some very heavy casualties during the first Chindit expedition. We had lost our C/O, Colonel Alex and Intelligence Officer St. George de la Rue, they had both been killed during No. 1 Column's retreat from the Irrawaddy.

Philip Conron, who had been replaced by Wingate as O/C of 4 Column had been killed or had died in some way or other re-crossing the Irrawaddy (actually it was in fact the Shweli River). I'm not sure whether he drowned or whether he was attacked by Burma Traitor Army people, but die he did. No one really knows quite how he was killed.

Another officer who was also lost, was Captain Vivian Weatherall of 1 Column. He died very gallantly on the Shweli River, trying to rescue some of his soldiers who were wounded. Some 290 plus Gurkha Other Ranks and followers were killed in action, or died as prisoners of war, or died of starvation. This was quite a heavy blow to befall a single battalion.

I would like to dedicate this story to the memory of Lady Mary de la Rue, St. George's mother, who never gave up trying to find out what had happened to her son in 1943. I for one can appreciate her stoical determination to seek out the full details of his time in Burma and the tenacious spirit this requires.

Update 19/05/2019.

After a further email communication from Thomas de la Rue, I was made aware of some new information in relation to Lady Mary's continued efforts to find out what happened to her son in Burma. From the pages of the West Sussex County Times, dated 18th February 1944:

MISSING FROM THE WINGATE EXPEDITION

Lady de la Rue Seeks News of Her Son

Sir Evelyn and Lady de la Rue, of The Normans, Rusper, are anxious for news of their son Lieutenant Victor St. George de la Rue, who has been missing from the Wingate expedition in Burma since April 1943.

Lieutenant de la Rue, after taking his degree in History at Oxford, joined the 60th Rifles in 1941. Shortly afterwards, the War Office asked for volunteers to officer Indian regiments, and, having been advised by his uncle, Lord Harris (the famous cricketer), he volunteered. On arriving in India he joined Brigadier Wingate's expedition into Burma. After indescribable difficulties, the river Irrawaddy was crossed on March 20th 1943, and immediately the expedition was attacked by the Japanese. It was in this engagement that Lieutenant de La Rue's Colonel, Colonel Alexander, was wounded in both legs.

Lieutenant de la Rue refused to leave his Colonel although Lord Wavell's instructions to the expedition had been, "every man for himself." He was joined by a New Zealand officer, Flight Lieutenant Edmonds, and between them they carried Colonel Alexander from March 20 to April 27, fighting and hiding alternatively. By this time they had reached the Mu River, and it is thought that they may have been ambushed at this point. Nothing has since been heard of them since.

This letter and other details regarding Lt. de la Rue can be viewed here: www.roll-of-honour.com/Sussex/Rusper.html

This is what Thomas had to say:

I am Lieutenant Colonel Thomas de la Rue. My great uncle was Lt. Victor St. George de la Rue of the King's Royal Rifle Corps, who was killed alongside Lt. Col. Alexander during the first Chindit expedition in April 1943. I wondered whether you have any information that you could pass on to me about my great uncle. I notice that you have a photograph of Lt. Col. Alexander's grave stone in the Taukkyan War Cemetery, and hoped that you might also have a picture of Lt. de la Rue's headstone as they were buried in the same grave, reference 19. G. 1-2.

Interestingly, even six years after St. George’s death, his mother (Lady Mary de la Rue) was still trying to find out what had happened to him in Burma. Evidently, it was Lady de la Rue who chose the very poignant words seen upon St. George's gravestone at Taukkyan. As an aside, and a point worth pondering, I suspect that St. George’s expeditionary/pioneering activities with his older brother in Rhodesia may well have provided the catalyst and inspiration for his enthusiasm to volunteer for the First Chindit Expedition.

After replying to Tom's email and supplying him with all the information I had to hand about his great uncle; he again replied:

Dear Steve

You are very kind for having put all of this together for my father and I. We are both tremendously grateful for your efforts. St. George achieved so much in his very short life and I am very glad we now know so much more about his final moments with Colonel Alexander.

We were astounded to hear that the War Office letter could provide the Colonel's own family with a vital missing link and therefore absolutely agree that the information should be passed to them. They might also like to see a photograph of the twenty-four year old Intelligence Officer buried with his Commanding Officer. St George's time in Burma has remained a little vague for us all - until now.

Thank you again for your considerable efforts.

A short time later I was pleased to receive an email from Tom's father, Anthony de la Rue:

Dear Steve

The information you have unearthed is indeed an extraordinary story and fills so many gaps for our family history. There is so much material here that it will take some time to assimilate it all. The recording by Lieutenant Dominic Neill is extraordinary in its content and clarity.

St. George joined his older brother, my father Ian de la Rue in 1936 in Rhodesia and helped him to set up the ranch which was my home. They pioneered in true style as you can see from the photo of St. George the day they set out with their worldly belongings in the back of my father's old Chevrolet, with the attendant dog on top.

St. George was very close to my father and my regret is that my father never knew what we know today thanks largely to your efforts. All he used to tell me was that his brother was killed in Burma with the Chindits and he was aware that he had remained with his CO who had been badly wounded and they died together. I found the letter to my grandmother amongst my fathers papers, so he must have known as much as is written there, namely that they were buried together after their remains were located, but could not be distinguished from each other. It is so tragic that the calamity of war can cut short a young life of such promise.

Anyway we are all the richer for knowing these things, and I imagine it must be exciting for you when, like now, so much suddenly comes together and missing links are found which connect the whole. What I find exciting myself is that the family of Colonel Alexander will, through all this, discover some of their own long forgotten past. I will be very interested in what transpires in your communications with them. By all means put them in communication with Thomas and myself if they wish, as we now know we are forever bound by a common grave.

For your general interest, I attach a short story my father wrote of his early life in Rhodesia, in which he mentioned St. George. Also attached is a picture of my father at about that time. As Thomas surmises, it was probably the experience with my father in the wilds of the Rhodesian Lowveld, that led St. George to look for an unconventional life in the British Army.

Best wishes. Anthony

My good fortune continued in July 2014, when I received an email from another member of the wider de la Rue family. Dave Grantham, who lives in New Zealand told me:

My father's first cousin was Victor St. George de la Rue. My grandmother Sybil Grantham (nee de la Rue) was St George's Aunt. I randomly typed “de la Rue Chindit" into Google and the search came up with your website. My own father lost six relations in WW1 and WW2: three cousins, an uncle, a brother and a nephew, so a few years ago, I set out to find more about the six of them. St. George was the one I knew least about, just that he was a Chindit.

At that time, I was looking through a secondhand bookshop in Wellington and came across Bernard Fergusson’s book Beyond the Chindwin. I was delighted to see the de la Rue name in the index. When Fergusson’s son George was High Commissioner to New Zealand I wrote to him and told him of my connection and got a nice letter in reply.

I read a number of other books including Ian MacHorton’s Safer than a Known Way and came to the same conclusion that you did, that St. George was the other man killed with Leigh Alexander, particularly when I found out later they were buried in a joint grave. I’m not sure if I’ve got this right but I think the CWGC told me that after initial burial, they had been transferred to the Mandalay War Cemetery and finally to Taukkyan in Rangoon. Presumably Leigh Alexander and St. George are in a joint grave because they couldn’t identify who was who when they exhumed the bodies.

I was particularly delighted you sent over a photo of St. George’s grave which I hadn't seen and thank you for the link to the CWGC site.

I have visited three war graves of my relations, but have yet to visit Rangoon to see St. George's.

Many thanks. Dave

I would like to take this opportunity to thank all three gentlemen for their invaluable contributions to this story. Anthony mentioned in his email a recording made by Lieutenant Dominic Neill, who served with Chindit Column 8 on Operation Longcloth. In this recording Neill recalls some of the 3/2 Gurkha Officers killed during the first Chindit expedition including Lieutenant de la Rue and Colonel Alexander. Here is a very short extract from his audio memoir:

Now the 3rd battalion as a whole had taken some very heavy casualties during the first Chindit expedition. We had lost our C/O, Colonel Alex and Intelligence Officer St. George de la Rue, they had both been killed during No. 1 Column's retreat from the Irrawaddy.

Philip Conron, who had been replaced by Wingate as O/C of 4 Column had been killed or had died in some way or other re-crossing the Irrawaddy (actually it was in fact the Shweli River). I'm not sure whether he drowned or whether he was attacked by Burma Traitor Army people, but die he did. No one really knows quite how he was killed.

Another officer who was also lost, was Captain Vivian Weatherall of 1 Column. He died very gallantly on the Shweli River, trying to rescue some of his soldiers who were wounded. Some 290 plus Gurkha Other Ranks and followers were killed in action, or died as prisoners of war, or died of starvation. This was quite a heavy blow to befall a single battalion.

I would like to dedicate this story to the memory of Lady Mary de la Rue, St. George's mother, who never gave up trying to find out what had happened to her son in 1943. I for one can appreciate her stoical determination to seek out the full details of his time in Burma and the tenacious spirit this requires.

Update 19/05/2019.

After a further email communication from Thomas de la Rue, I was made aware of some new information in relation to Lady Mary's continued efforts to find out what happened to her son in Burma. From the pages of the West Sussex County Times, dated 18th February 1944:

MISSING FROM THE WINGATE EXPEDITION

Lady de la Rue Seeks News of Her Son

Sir Evelyn and Lady de la Rue, of The Normans, Rusper, are anxious for news of their son Lieutenant Victor St. George de la Rue, who has been missing from the Wingate expedition in Burma since April 1943.

Lieutenant de la Rue, after taking his degree in History at Oxford, joined the 60th Rifles in 1941. Shortly afterwards, the War Office asked for volunteers to officer Indian regiments, and, having been advised by his uncle, Lord Harris (the famous cricketer), he volunteered. On arriving in India he joined Brigadier Wingate's expedition into Burma. After indescribable difficulties, the river Irrawaddy was crossed on March 20th 1943, and immediately the expedition was attacked by the Japanese. It was in this engagement that Lieutenant de La Rue's Colonel, Colonel Alexander, was wounded in both legs.

Lieutenant de la Rue refused to leave his Colonel although Lord Wavell's instructions to the expedition had been, "every man for himself." He was joined by a New Zealand officer, Flight Lieutenant Edmonds, and between them they carried Colonel Alexander from March 20 to April 27, fighting and hiding alternatively. By this time they had reached the Mu River, and it is thought that they may have been ambushed at this point. Nothing has since been heard of them since.

This letter and other details regarding Lt. de la Rue can be viewed here: www.roll-of-honour.com/Sussex/Rusper.html

Update 18/12/2020.

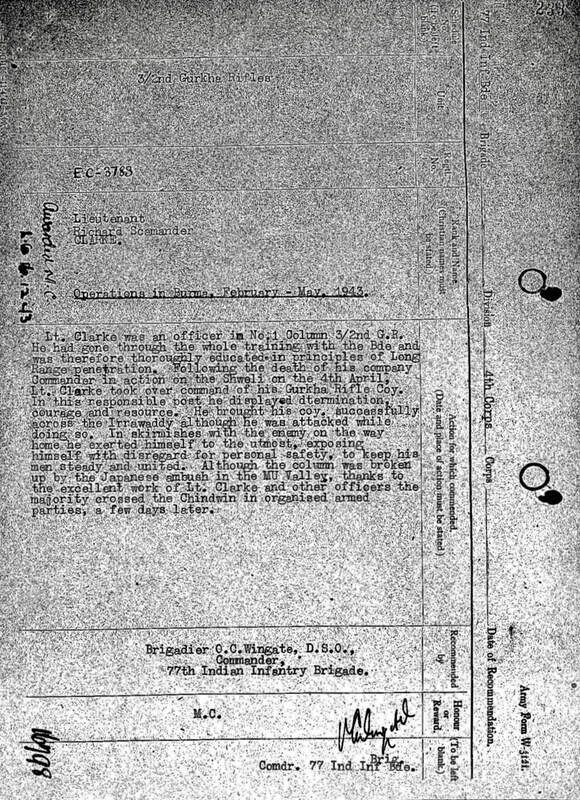

Lt. Richard Scamander Clarke

I fortunate recently to be sent a number of documents and papers in relation to some of the men that served on Operation Longcloth. This included a short memoir written by Lt. Dicky Clarke MC, who was part of No. 1 Column on the first Wingate expedition and who played a significant role during the column's return journey to India in April/May that year. I believe the narrative set out below was first published in one of the Regiment of Gurkhas annual journals, but there is no means to identify which one or when from the papers I have.

Richard Scamander Clarke was born on the 15th July 1921 and was the son of Major Percy Scamander Clarke MC and Violet Ethel Gresham Nicholson from Bexhill-on-Sea in Sussex. From the pages of the London Gazette it seems that Richard had begun his wartime service with the Royal Artillery as a Gunner, but took up an opportunity to join the Indian Army as an Officer Cadet in 1941.

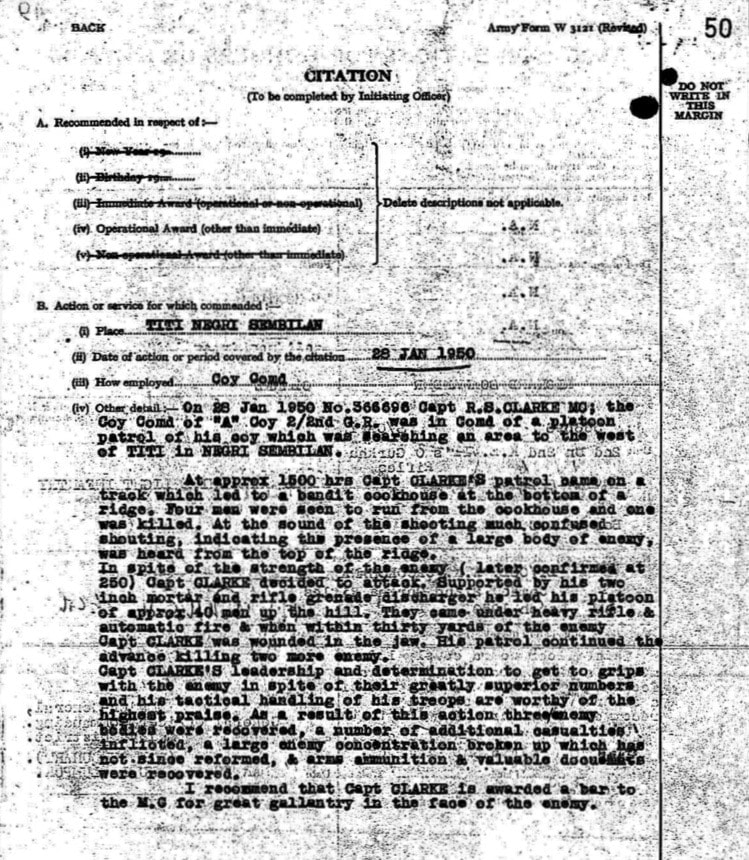

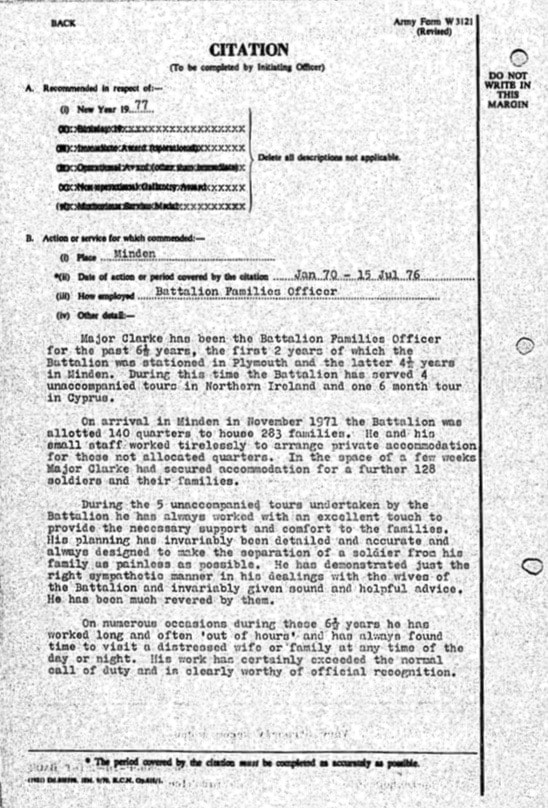

He was commissioned with the Army number, EC-3783 in September 1941 from the Officer Training School in Bangalore and posted to the 2nd Gurkha Rifles based at the time in Baluchistan. He served on Operation Longcloth in No. 1 Column under the command of Major George Dickson Dunlop MC and worked in particular with fellow Gurkha officer, Major Vivian Weatherall. The following year he remained with the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles and served as a company commander with the battalion in the Arakan region of Burma. Subsequently he served with the Gurkhas and the King's Shropshire Light Infantry in Malaya where he was also wounded, Mentioned in Despatches and awarded a bar to his MC. He joined the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry in 1950 and also served with the Durham Light Infantry in Korea, before retiring in 1976.

What I Remember, by Dicky Clarke

The last message we got from Wingate before we abandoned our mules was seek freedom in the hills. We were by then in the foothills east of the Irrawaddy.

About an hour after we left the mules we heard the Japs mortaring the position thinking we were still there. We took Wingate's advice as there was no alternative and we climbed up higher and higher in an easterly direction. We rested on the top of a wooded ridge and while we were there the Japs caught up with us but we had them pinned down on the forward slope of the hill leading to the ridge we were on. I remember Vivian Weatherell who commanded our Gurkha Company, A Company of No. 1 Column, move forward so that he could overlook the slope the Japs were on and empty his tommy gun into them, swearing appropriately in Gurkhali as he did so.

We knew it would not be long before enemy reinforcements arrived and decided we had better not dawdle but try and cross the main road before we were cut off. So we mounted our 3 inch mortar and fired off all our bombs on the slope the Japs were on and then continued our march eastwards having radioed for fighter air support before abandoning the wireless set, the mortars and the mules that had carried them.

We crossed the road safely which was a major artery between two towns occupied by the Japs and continued through mountainous country making for the Shweli River, which it was intended we would cross and make for China as we knew the Japs would be waiting for us at every turn if we tried to return the way we had come into Burma, with both the Irrawaddy and Chindwin rivers to recross before reaching home.

We had had our last supply drop a week or so ago and from now on we had to live off the country and this we did by obtaining what we could from the villages we passed through and of course, the Burmese platoon was invaluable for this end. We finally reached the Shweli River without encountering the Japs and we found that the river was only about thirty yards wide but very fast flowing and impossible to cross without help. So one or two good swimmers swam across with a line with the intention of making a rope of rifle slings. At !east this was the idea but no sooner had they crossed than the Japs arrived along the far bank and we had to abandon the idea. It was at this time Vivian Weatherell was killed by a Japanese machine gun from across the river.

There was no alternative but to give up the idea of making for China and we started on our return journey westwards instead. We reached the Irrawaddy almost intact but discovered the Japs had removed all the boats to the west bank of the river. A conference was held and it was decided to form an escape party of a few selected officers and men so that at least someone could get back to tell the tale. In the meantime two boats had been found which the villagers had sunk in order to hide them from the Japanese and that night most of the Column and Group Headquarters were paddled across the river, nearly a mile wide, in those two narrow boats which held about fifteen men each sitting jammed up behind each other. Luckily for us the Japs slept soundly that night but with the dawn they we were spotted and they shot up the last two boats leaving only a few men behind on the east bank.

So the column was not too depleted, but not long after we had set off westwards that morning we were well and truly ambushed, resulting in the death of Lt. Colonel Alexander, our Group Commander, Lieutenant George de !a Rue and others. Mortar bombs exploded all amongst us and we just made our way westwards through it all as best we could, visibility being very limited in that type of jungle country. The walking wounded had to keep up as best they could.

We seemed to wade for days down chaungs with steep vertical sides and on finally coming out into flatter country we would be ambushed and each time we got split into smaller and smaller parties. It was a fight against time as lack of food was in the end going to be the deciding factor. At one ambush site the Japanese had posted a notice describing how one could surrender and the remnants of the Commando Platoon almost to a man did exactly that. Of course, the Gurkhas survived much better on no or little rations than the British ranks.

On nearing the Chindwin River a few water buffaloes were seen grazing in paddy fields not far from a village on the river. It was decided to send a couple of Gurkhas to kill one with a kukri as to shoot would have given us away. But to our horror a shot rang out and one of the buffaloes hit the dust. It was now a question of out with the kukris and cut as much of it up and away before being spotted. Hardly had we started than a few Burmese, some armed with British .303 rifles came out of the jungle into the clearing. We parleyed with them to gain time and as we withdrew into the jungle again with some Gurkhas still on the buffalo the Japs arrived and opened up on the position with automatic weapons and mortars.

We made a detour through the jungle making for the river and lay up a few hundred yards from it. We distributed the buffalo meat as best we could amongst us, eating it raw and with relish. Our party then comprised George Dunlop who was the Column Commander, John Fowler and two other officers and about a dozen other ranks. Japs were seen patrolling the river along a track running parallel to it probably from the village that the buffaloes had belonged to. There seemed nothing for it but to try and cross the river that night, but how? It was decided that those who could swim should try and cross and those who couldn't would have to be left. John Fowler couldn't swim but he was given one of our issue water wings to make the attempt.

George Dunlop advised us not to wear our footwear but tie it round our necks which I didn't do. John Fowler got into difficulties a few yards out and one gallant officer helped him back to the bank before swimming over himself. The river was about 500 yards wide and I was surprised how easily I floated. I reached the west bank and found I was near George Dunlop whose boots had floated away with the current and for the next three days the two of us walked westwards, George bare footed. We ate raw paddy which we found in deserted huts in the fields. On the third day we to came to a river running westwards. We knew the Indian traitor army (INA) was about in those parts so we had to be careful and I was not in favour of walking along the track beside the river in case of ambush, but in the end weariness prevailed and we decided to do so come what may.

Suddenly, we heard a shout from across the river, come over this way, Sir. Oh well, I said to George at least we will get something to eat even if they are Japs. George waded across that river as if he had a new lease of life and I followed to be received not by Japs but our own side, an Indian Army unit, the Mahrattas, I think. We were safe once more!

Lt. Richard Scamander Clarke

I fortunate recently to be sent a number of documents and papers in relation to some of the men that served on Operation Longcloth. This included a short memoir written by Lt. Dicky Clarke MC, who was part of No. 1 Column on the first Wingate expedition and who played a significant role during the column's return journey to India in April/May that year. I believe the narrative set out below was first published in one of the Regiment of Gurkhas annual journals, but there is no means to identify which one or when from the papers I have.

Richard Scamander Clarke was born on the 15th July 1921 and was the son of Major Percy Scamander Clarke MC and Violet Ethel Gresham Nicholson from Bexhill-on-Sea in Sussex. From the pages of the London Gazette it seems that Richard had begun his wartime service with the Royal Artillery as a Gunner, but took up an opportunity to join the Indian Army as an Officer Cadet in 1941.

He was commissioned with the Army number, EC-3783 in September 1941 from the Officer Training School in Bangalore and posted to the 2nd Gurkha Rifles based at the time in Baluchistan. He served on Operation Longcloth in No. 1 Column under the command of Major George Dickson Dunlop MC and worked in particular with fellow Gurkha officer, Major Vivian Weatherall. The following year he remained with the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles and served as a company commander with the battalion in the Arakan region of Burma. Subsequently he served with the Gurkhas and the King's Shropshire Light Infantry in Malaya where he was also wounded, Mentioned in Despatches and awarded a bar to his MC. He joined the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry in 1950 and also served with the Durham Light Infantry in Korea, before retiring in 1976.

What I Remember, by Dicky Clarke

The last message we got from Wingate before we abandoned our mules was seek freedom in the hills. We were by then in the foothills east of the Irrawaddy.

About an hour after we left the mules we heard the Japs mortaring the position thinking we were still there. We took Wingate's advice as there was no alternative and we climbed up higher and higher in an easterly direction. We rested on the top of a wooded ridge and while we were there the Japs caught up with us but we had them pinned down on the forward slope of the hill leading to the ridge we were on. I remember Vivian Weatherell who commanded our Gurkha Company, A Company of No. 1 Column, move forward so that he could overlook the slope the Japs were on and empty his tommy gun into them, swearing appropriately in Gurkhali as he did so.

We knew it would not be long before enemy reinforcements arrived and decided we had better not dawdle but try and cross the main road before we were cut off. So we mounted our 3 inch mortar and fired off all our bombs on the slope the Japs were on and then continued our march eastwards having radioed for fighter air support before abandoning the wireless set, the mortars and the mules that had carried them.

We crossed the road safely which was a major artery between two towns occupied by the Japs and continued through mountainous country making for the Shweli River, which it was intended we would cross and make for China as we knew the Japs would be waiting for us at every turn if we tried to return the way we had come into Burma, with both the Irrawaddy and Chindwin rivers to recross before reaching home.

We had had our last supply drop a week or so ago and from now on we had to live off the country and this we did by obtaining what we could from the villages we passed through and of course, the Burmese platoon was invaluable for this end. We finally reached the Shweli River without encountering the Japs and we found that the river was only about thirty yards wide but very fast flowing and impossible to cross without help. So one or two good swimmers swam across with a line with the intention of making a rope of rifle slings. At !east this was the idea but no sooner had they crossed than the Japs arrived along the far bank and we had to abandon the idea. It was at this time Vivian Weatherell was killed by a Japanese machine gun from across the river.

There was no alternative but to give up the idea of making for China and we started on our return journey westwards instead. We reached the Irrawaddy almost intact but discovered the Japs had removed all the boats to the west bank of the river. A conference was held and it was decided to form an escape party of a few selected officers and men so that at least someone could get back to tell the tale. In the meantime two boats had been found which the villagers had sunk in order to hide them from the Japanese and that night most of the Column and Group Headquarters were paddled across the river, nearly a mile wide, in those two narrow boats which held about fifteen men each sitting jammed up behind each other. Luckily for us the Japs slept soundly that night but with the dawn they we were spotted and they shot up the last two boats leaving only a few men behind on the east bank.

So the column was not too depleted, but not long after we had set off westwards that morning we were well and truly ambushed, resulting in the death of Lt. Colonel Alexander, our Group Commander, Lieutenant George de !a Rue and others. Mortar bombs exploded all amongst us and we just made our way westwards through it all as best we could, visibility being very limited in that type of jungle country. The walking wounded had to keep up as best they could.

We seemed to wade for days down chaungs with steep vertical sides and on finally coming out into flatter country we would be ambushed and each time we got split into smaller and smaller parties. It was a fight against time as lack of food was in the end going to be the deciding factor. At one ambush site the Japanese had posted a notice describing how one could surrender and the remnants of the Commando Platoon almost to a man did exactly that. Of course, the Gurkhas survived much better on no or little rations than the British ranks.

On nearing the Chindwin River a few water buffaloes were seen grazing in paddy fields not far from a village on the river. It was decided to send a couple of Gurkhas to kill one with a kukri as to shoot would have given us away. But to our horror a shot rang out and one of the buffaloes hit the dust. It was now a question of out with the kukris and cut as much of it up and away before being spotted. Hardly had we started than a few Burmese, some armed with British .303 rifles came out of the jungle into the clearing. We parleyed with them to gain time and as we withdrew into the jungle again with some Gurkhas still on the buffalo the Japs arrived and opened up on the position with automatic weapons and mortars.

We made a detour through the jungle making for the river and lay up a few hundred yards from it. We distributed the buffalo meat as best we could amongst us, eating it raw and with relish. Our party then comprised George Dunlop who was the Column Commander, John Fowler and two other officers and about a dozen other ranks. Japs were seen patrolling the river along a track running parallel to it probably from the village that the buffaloes had belonged to. There seemed nothing for it but to try and cross the river that night, but how? It was decided that those who could swim should try and cross and those who couldn't would have to be left. John Fowler couldn't swim but he was given one of our issue water wings to make the attempt.

George Dunlop advised us not to wear our footwear but tie it round our necks which I didn't do. John Fowler got into difficulties a few yards out and one gallant officer helped him back to the bank before swimming over himself. The river was about 500 yards wide and I was surprised how easily I floated. I reached the west bank and found I was near George Dunlop whose boots had floated away with the current and for the next three days the two of us walked westwards, George bare footed. We ate raw paddy which we found in deserted huts in the fields. On the third day we to came to a river running westwards. We knew the Indian traitor army (INA) was about in those parts so we had to be careful and I was not in favour of walking along the track beside the river in case of ambush, but in the end weariness prevailed and we decided to do so come what may.

Suddenly, we heard a shout from across the river, come over this way, Sir. Oh well, I said to George at least we will get something to eat even if they are Japs. George waded across that river as if he had a new lease of life and I followed to be received not by Japs but our own side, an Indian Army unit, the Mahrattas, I think. We were safe once more!

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to Lt. Dicky Clarke, including a photograph of him and some of his colleagues from the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles in the Arakan and the official recommendations for his MC, MC and Bar and the award of the MBE in June 1976. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. Richard Scamander Clarke sadly passed away on the 30th November 2005.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, February 2015.