Lt.-Colonel Leigh Arbuthnot Alexander

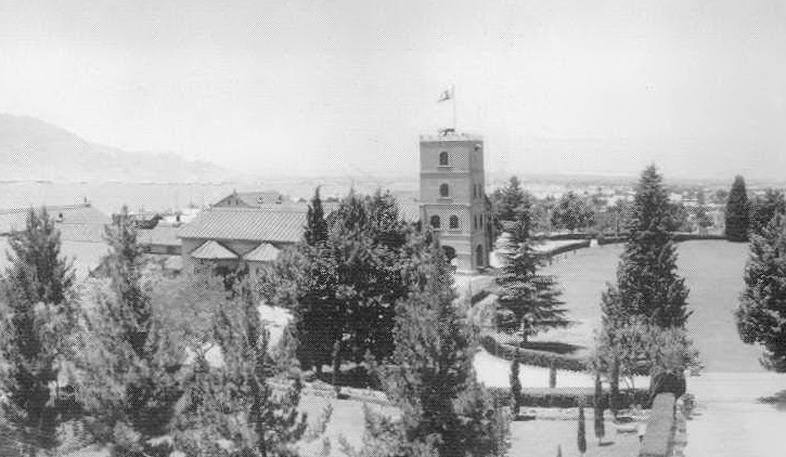

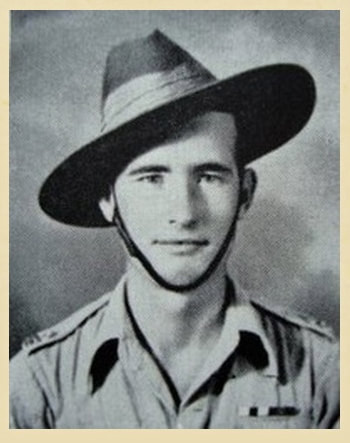

Leigh Arbuthnot Alexander pre-WW2.

Many people, including myself have wondered why so little has ever been written about Leigh Arbuthnot Alexander and his fateful time in Burma during the first Chindit operation of 1943. He was the senior Gurkha officer on the mission and the C/O of Southern Group, and yet the story of this well respected career soldier has always been shrouded in mystery and conjecture.

Within the books and diaries written, he is rarely mentioned and this has left us unsure about his time on the operation, his experiences and of course his untimely death whilst attempting to bring his beloved Gurkhas back to the safety of Allied held territory. With the help of some lesser known papers, recently discovered, and the invaluable help of his family, I think a better picture of his time on Operation Longcloth can now be shown.

Leigh was born on the 4th July 1898 in Umzinto, a town some 70km or so from Durban in the Kwazulu/Natal province of South Africa. He was the son of Major William Alexander and Ethel Rubina Arbuthnot and the younger brother of Gilbert William. Both Leigh and Gilbert were keen sportsmen and played cricket and hockey for several representative sides at school and later on in colonial India. It is probably true to say that Gilbert was the better cricketer of the two, but that Leigh had the upper hand at tennis.

NB: In the early 1930s, Gilbert also had the honour of captaining Scotland at cricket which included playing first-class matches against touring sides from Australia, New Zealand and India. (Information courtesy of Tim Coppin).

Both brothers decided upon a military career and early on in their soldiering found themselves serving during the horrors of WW1. Gilbert found himself in Belgium with the Gordon Highlanders Regiment, whilst Leigh was serving with the 2/5 Royal Gurkha Rifles Frontier Force on the Indian/Afghanistan border, or Northwest Frontier as it was known back then. According to official records he joined the 2/5 Gurkhas on the 11th May 1917.

Leigh was commissioned into the Indian Army on the 27th October 1917, he was aged 19. He had studied at the Officers Cadet College in Quetta and was gazetted to 2nd Lieutenant on the above mentioned date, eventually taking up his commission in the 2/5 Royal Gurkha Rifles at their regimental centre in Abbottabad. The Staff College at Quetta had been founded in 1907 and was the main training centre for young officer cadets destined for service in the Indian Army. Leigh's Army career progressed steadily with promotion to Captain in 1922 and again to Major in 1935.

Shown below are the Medal entitlement cards for the two Alexander brothers and their service in WW1, with Gilbert's card, showing his entry into the war in the Belgium theatre on 25th December 1914 with the 1st Battalion Gordon Highlanders. He was stated as being entitled to the standard WW1 issue of 1914/15 Star, British War and Victory medals. His card also shows that he was awarded the Military Cross (alongside a further Mention in Despatches) for his efforts with the 1st Battalion of the Gordon Highlanders in France & Flanders. Gilbert had a long and very distinguished military career with the Gordon Highlanders Regiment across both wars and reaching the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel.

Leigh's card is scant in detail, however, for his service on the Northwest Frontier, he may have been entitled to the Indian General Service medal and probably the British War medal, or, it is also possible that he too would have been awarded the same trio of medals as his brother, plus the IGS. Please click on the cards to bring them forward on the page.

Within the books and diaries written, he is rarely mentioned and this has left us unsure about his time on the operation, his experiences and of course his untimely death whilst attempting to bring his beloved Gurkhas back to the safety of Allied held territory. With the help of some lesser known papers, recently discovered, and the invaluable help of his family, I think a better picture of his time on Operation Longcloth can now be shown.

Leigh was born on the 4th July 1898 in Umzinto, a town some 70km or so from Durban in the Kwazulu/Natal province of South Africa. He was the son of Major William Alexander and Ethel Rubina Arbuthnot and the younger brother of Gilbert William. Both Leigh and Gilbert were keen sportsmen and played cricket and hockey for several representative sides at school and later on in colonial India. It is probably true to say that Gilbert was the better cricketer of the two, but that Leigh had the upper hand at tennis.

NB: In the early 1930s, Gilbert also had the honour of captaining Scotland at cricket which included playing first-class matches against touring sides from Australia, New Zealand and India. (Information courtesy of Tim Coppin).

Both brothers decided upon a military career and early on in their soldiering found themselves serving during the horrors of WW1. Gilbert found himself in Belgium with the Gordon Highlanders Regiment, whilst Leigh was serving with the 2/5 Royal Gurkha Rifles Frontier Force on the Indian/Afghanistan border, or Northwest Frontier as it was known back then. According to official records he joined the 2/5 Gurkhas on the 11th May 1917.

Leigh was commissioned into the Indian Army on the 27th October 1917, he was aged 19. He had studied at the Officers Cadet College in Quetta and was gazetted to 2nd Lieutenant on the above mentioned date, eventually taking up his commission in the 2/5 Royal Gurkha Rifles at their regimental centre in Abbottabad. The Staff College at Quetta had been founded in 1907 and was the main training centre for young officer cadets destined for service in the Indian Army. Leigh's Army career progressed steadily with promotion to Captain in 1922 and again to Major in 1935.

Shown below are the Medal entitlement cards for the two Alexander brothers and their service in WW1, with Gilbert's card, showing his entry into the war in the Belgium theatre on 25th December 1914 with the 1st Battalion Gordon Highlanders. He was stated as being entitled to the standard WW1 issue of 1914/15 Star, British War and Victory medals. His card also shows that he was awarded the Military Cross (alongside a further Mention in Despatches) for his efforts with the 1st Battalion of the Gordon Highlanders in France & Flanders. Gilbert had a long and very distinguished military career with the Gordon Highlanders Regiment across both wars and reaching the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel.

Leigh's card is scant in detail, however, for his service on the Northwest Frontier, he may have been entitled to the Indian General Service medal and probably the British War medal, or, it is also possible that he too would have been awarded the same trio of medals as his brother, plus the IGS. Please click on the cards to bring them forward on the page.

In mid-1942 Wingate was drawing together the resources for his planned expedition into occupied Burma, these included the 13th Battalion, the Kings Regiment, an overly mature group of men mostly from Northwest England and the young and very green 3/2 Gurkha Rifles. The youthful Gurkhas (whose average age was only 17/18) had hardly any combat experience within their ranks and no knowledge of jungle warfare whatsoever. They made the move from their base at Loralai, a town close to the Northwest Frontier of India, now current day Pakistan, to the Chindit training camp at Saugor.

The 2nd Gurkha Rifle Regimental Newsletter for Summer 1942 stated that:

Alexander's Battalion.

News from this Battalion is very scarce. They live in the backwoods and are immersed in the toughest possible training. A route march of 200 miles is a fairly normal occurrence for them. They have no comforts, no homes, no paper and probably no time for writing letters.

During the recent rains they were overtaken by serious floods and the battalion lost a good deal of its property. This occurred at night and I understand the battalion had to take shelter in the nearby trees. Some of the men did useful rescue work.

After months spent on mechanisation they suddenly lost their vehicles and had to adopt mules. A vast mob of untrained mules, which took some handling and breaking-in. This proved to be a complete reversal of their previous training, but the battalion has got down to it and before long we should be getting some interesting news from them.

Those who cast a gloomy eye on the present physique of Goorkha recruits, should get some comfort from the way the recruits in this battalion are standing up to what is probably the toughest training any battalion has undergone.

General MacDonald who recently saw them at work, was full of praise for these men.

As training for Operation Longcloth began both the above battalions struggled to come to terms with the basic premise of Long Range Penetration. Lt.-Colonel Alexander and his Gurkhas suffered further, when their original company commanders were replaced by Wingate with British Officers experienced in jungle warfare, but with no knowledge of commanding Indian troops. One of the new officers, George Dunlop, who took command of Column 1 stated, "3/2 lacked consistent leadership at Column level, it was a grave mistake to replace or supercede their original commanders with British Officers who could not speak Gurkhali". He went on to remark that, "A Gurkha Rifleman changes his loyalty slowly, if at all".

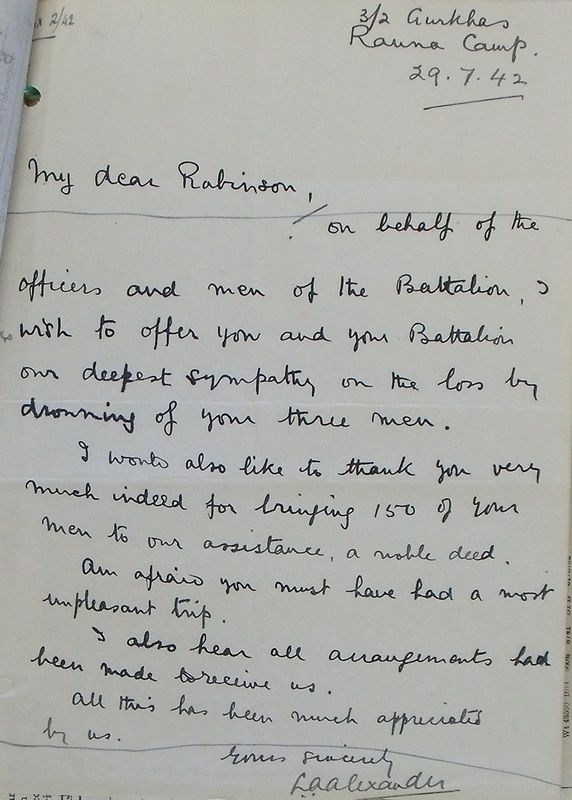

In the meantime Alexander stuck to the task at hand with determination and stoicism, but many Gurkha recruits came and went before the column numbers finalised and some semblance of structure was achieved. He had shown his qualities as a leader and his compassion as a man when a small group of British Other Ranks were lost during a rivercraft exercise in training. Three men had drowned in the incident which took place in late July (1942), when the river had burst it's banks in a sudden spate. Although it was only the 13th Kings that suffered casualties that day, many Gurkhas had to climb up into trees to avoid the rapidly rising waters, these men had eventually been led to safety by the Kings later on in the day. Alexander, grateful of the help, sent the letter shown below to his opposite number Lieutenant-Colonel W.M. Robinson of the Kings Regiment.

Lt. Colonel Alexander's story in 1943 was consistently inter-twined with that of Major George Dunlop, commander of Column 1 that year. Dunlop had worked with Mike Calvert during the British retreat from Burma the year before, performing acts of sabotage against the advancing Japanese Army. He had learned the trade of jungle warfare at the clandestine Bush Warfare School located at the hill station town of Maymyo. His arrival at Saugor had been delayed due to ill health (Dunlop had contracted cholera on the march out of Burma in 1942).

As mentioned earlier Alexander was the commander of the Southern Group on Operation Longcloth, this consisted of two Gurkha columns, numbered 1 and 2 and his own Group Head Quarters. This unit was used by Wingate as a decoy on the operation, the intention being for Southern Group to draw attention away from the main Chindit columns of Northern Group whilst they crossed the Chindwin River and moved quickly east toward their targets along the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway.

Southern Group crossed the Chindwin on 15/16 February 1943 at a place called Auktang. Their orders were to march toward their own prime target, the rail station at Kyaikthin. They marched openly along well known local trails and paths and also received a large supply drop from the air, which must have announced their presence in the area to the Japanese. The decoy group were accompanied at this time by a Company of Sikh Mountain Artillery and a section of Seaforth Highlanders. This supplementary unit were to create a further diversion for Wingate by attacking the town of Pantha, alerting the enemy to the possibility that there might well be a full-scale re-invasion taking place. To all intents and purposes these tactics succeeded and Northern Group did proceed unmolested toward their objectives.

On the 2nd March Columns 1 and 2 had reached the outskirts of Kyaikthin, Dunlop was given the order to blow up the railway bridge, whilst Column 2 under the command of Major Arthur Emmett along with Group HQ were to head on towards the rail station itself. What neither group realised was that the Japanese had by now closed in on the unsuspecting Chindits and lay in wait just a short way up the tracks. To make matters worse the two Gurkha columns had also now lost radio contact. Column 2 and Group Head Quarters in the black of night stumbled into the enemy ambush which straddled both sides of the railway line embankment. Here is how Lieutenant Ian MacHorton recalls that moment:

"We shuffled to a halt as the guides probed forward. There came the sound of just one bang up front, then an inferno of noise engulfed the world around me. There came the high-pitched staccato scream of a machine gun, then overwhelmingly many others joined in, the crash and ping of rifle bullets, the banging of grenades as the battle reached a fearful crescendo. Men and mules were lying, twisted and contorted, twitching and writhing, others were still erect, stark in the moonlight, heaving and jerking in the midst of this chaos. Then a sinister scuffling noise made by men of all kinds in close combat. The close combat of bayonet and kukri, the fanatical, personal slaughter with blood-dripping cold steel".

Later on during the operation MacHorton was injured by mortar shrapnel and the Colonel had to make the agonising decision to leave him by the track side and certain death or capture at the hands of the Japanese. All men knew that this was the ultimate reality of the operation as no casualty evacuation was possible. MacHorton recalls how the Colonel dealt with this situation with compassion and understanding, but that he (Alexander) looked worn down by the pressures of command and responsibility.

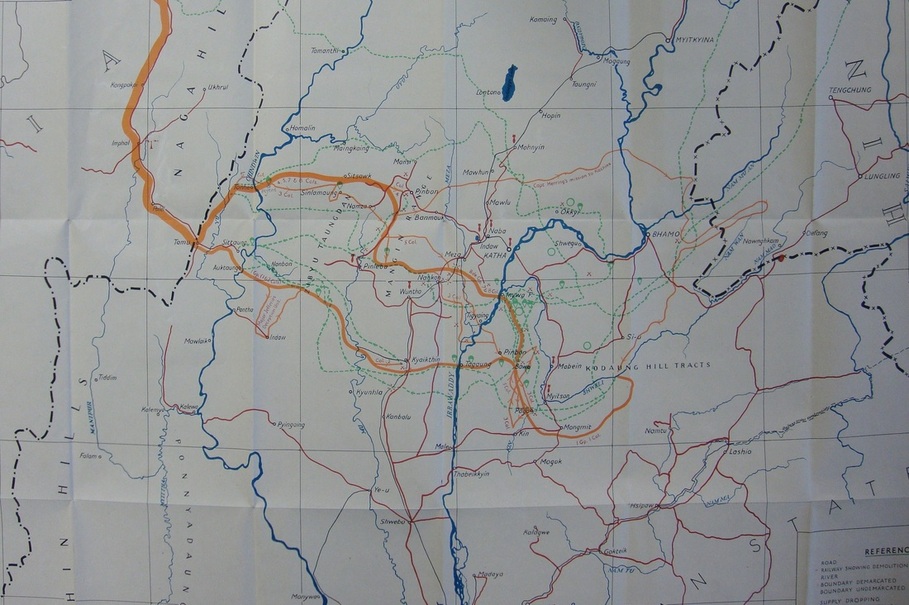

Below is a map showing the journey routes of the Chindit columns in 1943. The lower orange line traces the Southern Group from their crossing of the Chindwin at Auktang, onward to Kyaikthin, then over the Irrawaddy until they take their southerly detour towards Mongmit. It then shows their failure to cross the Shweli River, then as the still thinner line turns to green, how they basically retrace their steps in an attempt to reach the safety of India once more. The upper orange line shows the route taken by Northern Section.

Colonel Alexander managed to extract the majority of his Head Quarters from the chaos and devastation at Kyaikthin, he decided to lead them away to the agreed rendezvous point a few miles further east. His decision to keep to the pre-operational plan and move on toward the Irrawaddy River clearly showed his determination to carry out Wingate's orders and to test the theories of dispersal under enemy fire. He could easily have chosen to turn around west and head for the safety of the Chindwin. (Something that Major Emmett and a large number of Column 2 chose to do, and who could really blame them).

NB. Nothing much has ever been written about what happened to Arthur Emmett after his return to India in March 1943. An amiable former tea planter from North Bengal, he was described by his men "as a kindly man with a quiet smile that instantly put one at ease". (Source, Ian MacHorton).

Within a few days (about the 7th March) Group Head Quarters with the survivors from Column 2 had met up once more with George Dunlop and his men. Together they crossed the Irrawaddy River. Southern Group now found themselves the most easterly placed Chindit unit and by that very nature the furthest from the safety of India. All remaining Chindit columns were now over the Irrawaddy and placed in a natural box contained on two sides by the Shweli and Irrawaddy Rivers, the force was trapped and slowly the Japanese began to close in.

Back in India, 4 Corps HQ in conversation with Wingate agreed it was time to recall the Brigade and the dispersal signal was given to all columns in late March. Alexander had a very clear vision in his mind at this point; to return his group back to India in one piece and as one unit. However, after several days attempting to avoid contact with the Japanese on the Mongmit/Mogok Road, the Colonel reluctantly agreed to jettison the majority of his mules and all of the heavy arms and equipment. The men again met with disaster on April 6th when they arrived, just too late, at a Supply Drop location, to see the planes heading home still fully laden. Alexander held an officers conference, where the decision was made (with the Colonel's full support) to head north to the Allied held outpost of Fort Hertz.

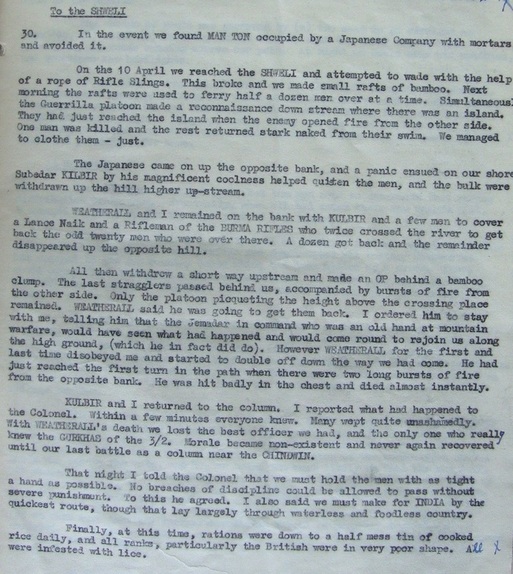

By the 10th April the group had reached the banks of the fast flowing Shweli River. Some other Chindit columns had managed to cross at various points roughly one week before, but the Gurkhas of Southern Group struggled, losing several men in two aborted attempts to reach the north bank. Amongst the casualties on April 10th was Vivian Stuart Weatherall, who had been the original Gurkha Rifle officer in charge of Column 1 before Major Dunlop's arrival at Saugor, he was very much loved by his Gurkha soldiers and his death was a massive blow to their morale. Here is how George Dunlop remembers that day:

Failure to cross the Shweli cost the group their chance of reaching Fort Hertz and under some considerable pressure, Colonel Alexander reluctantly agreed to change course and head directly west for India. It was during this period that the party, now numbering some 480 men began to show signs of fatigue, this of course was mainly due to the lack of decent rations and availability of good drinking water, but general discipline had fallen away quite dramatically too. The young Gurkhas were constantly on edge, reacting to any jungle noise with undue alarm and expecting an ambush around every corner.

Once again the men faced the obstacle of the mile wide Irrawaddy River, this time with the help of local boats the ailing Gurkhas managed to scramble over in groups of 30 at a time. Morale was now at an all time low and group decisions had become difficult and contested. Major Dunlop's influence seemed to be shaping group plans much more now and I wonder whether the strain of command and the Colonel's age (45 years) became a factor at this juncture.

On the morning of the 26th April the party bivouacked in the teak forest south of Map Point 1070, close to the Mu River. The group were now some 350 in number and were roughly speaking re-tracing their outbound steps. George Dunlop takes up the story once more:

"At about 1100 hours, Lieutenant Clarke roused me to say that there were villagers below us. I ordered out a patrol to collect them for questioning. On sight of the patrol they ran away. After a short while reports came back that there were Japanese coming up the hill. I did not take this too seriously at first, but it did turn out to be true, the next thing I saw was my Gurkha patrol running past me".

In the confusion both Gurkha Rifles and enemy troops had raced past the unsuspecting commander and chaos ensued. After things had settled down somewhat, Dunlop collected what men he could find and decided to move forward toward the nearby chaung (stream). Several of his officers were now missing from the main party. With the Burma Rifle Scouts now leading, the group pushed into some thick scrub on the other side of the chaung, for 10 minutes or so they moved slowly forward in the hope that the missing men might catch up, suddenly firing broke out to the rear. George Dunlop continues:

"As it turned out a party of the enemy had come up the river just in time to see the last of our men enter the jungle. They opened up at random, though with heavy fire. I gave the order for everyone to keep moving. The enemy began a sort of searching fire and several mortar bombs landed nearby. One landed so close I could feel the blast and hear the splinters, a RAF sergeant marching next to me was hit.

Coming to open ground I gave the order to extend by platoons and we doubled across in quite good order. After reaching good cover on the other side I halted to check up on things. It was then that Clarke came up to me looking ghastly. I asked him what was wrong and he told me that the last mortar bomb had blown away most of the Colonel's and officer De La Rue's legs. Edmonds (Column 1 RAF Liaison officer) and some orderlies had carried them away into the jungle, but that no one could now be found who knew of their whereabouts. The news had taken all this time to reach Clarke who spoke a fair amount of Gurkhali, and had never reached me at all, although the Colonel's party were within twenty five yards of me in the thick scrub.

My old friend Sergeant Hill of the Middlesex Regiment, had been hit too and had now disappeared. This was just about our worst day so far. Five officers and 80 men missing. We were pretty gloomy in bivouac that night".

NB. Two weeks later and after several more brushes with the Japanese and Burmese National Army the remainder of the group re-crossed the Chindwin River and reached the safety of British lines.

So now we have a much clearer picture of what happened to Lt.-Colonel Alexander in 1943, the two major points in question seem to have been answered amongst the information provided by George Dunlop's debrief notes. It shows clearly that the Commander was present at Kyaikthin with Column 2 on March 2nd, that he went forward with his HQ Section after the ambush and that he joined up with Dunlop and Column 1 shortly afterwards. The circumstances and details of his death are starkly explained in the quotations above.

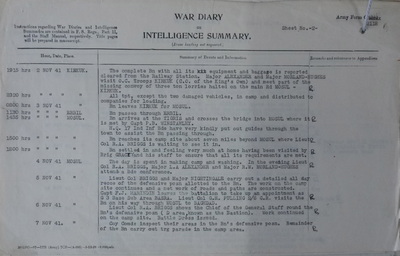

Alexander was buried in Taukkyan War Cemetery after the war had ended. It is to be presumed that he and Lieutenant De La Rue were buried by Edmonds and the other men present at the time, and that somebody kept a record of the precise location. It is very rare indeed for men lost in the Burmese jungle in 1943 to be given an actual grave memorial, usually these casualties are remembered on the Rangoon Memorial, also found in the grounds of Taukkyan War Cemetery. To illustrate this point still further, Vivian Weatherall, who perished just a few weeks earlier at the aborted Shweli River crossing, has no known grave and his name is to be found on Face 57 of the Rangoon Memorial.

To learn more about Lieutenant de la Rue and his life before Operation Longcloth, please click on the following link: St. George de la Rue

Flight Lieutenant John Kingsley Edmonds (an Australian member of the New Guinea Air Force before Operation Longcloth) was captured two days later on the 28th April, he spent the next two years in Rangoon Jail. Here he was central in keeping detailed records of the Chindit POW's from 1943, including holding letters and photographs given to him by men who sadly perished in the jail. On more than one occasion after the war he travelled to the families of these men and returned the mementos he had so carefully looked after. He was undoubtedly the sort of man who would ensure that the location of any original burial site be recorded and delivered to the powers that be back in India.

Of the other men mentioned in the narrative, Major Dunlop and Lieutenant Richard S. Clarke both swam the Chindwin River to safety. Ian MacHorton also made it back to India eventually, but not before being held prisoner by the Japanese for a short time. His amazing story is recorded in his book, Safer than a Known Way. Sergeant Jack Hill was indeed wounded at the river engagement and he too was taken prisoner, sadly dying of beri beri in Rangoon Jail later in the year.

Here are the CWGC details for L.A. Alexander, Victor St. George de la Rue and Vivian Weatherall (please click on the links to view the information):

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2083924/ALEXANDER,%20LEIGH%20ARBUTHNOT

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2085175/De La Rue

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2528356/WEATHERALL,%20VIVIAN%20STUART

Official viewpoints and personal tributes

It is probably true to say that Brigadier Wingate was not overly impressed by the performance of the Gurkha troops on Operation Longcloth, perhaps with the exception of those led by Major Calvert in Column 3. The vast majority of Gurkha Columns 2 and 4 had returned to India after meeting the Japanese in combat, deciding on dispersal to the rear, rather than following the Brigadier's instruction to always move forward. He had also planned for Southern Group in it's entirety to liaise with a special scouting mission in the Kachin Hills led by Captain 'Fish' Herring. The rendezvous date of 29th March was missed by Colonel Alexander, but presumably this was only due to the unexpected action at Kyaikthin.

I feel that the criticism aimed at 3/2 Gurkha was extremely harsh, they were after all a very young and inexperienced battalion, who had endured many 'last minute' changes to both leadership and command. I do wonder if Wingate was sub-consciously venting his obvious frustrations against the Indian General Command and their overt lack of support for his Chindit program and theories. Did he take these out on the commanders of Gurkha columns in 1943?

For the record, here is a transcription from Brigadier Wingate's operational report in regard to the performance of Southern Group and in particular Column 2 in 1943.

During the 26/27th of February, Southern Group had had a supply drop near Yeshin village and then continued it's march towards the railway. On the 2nd March the Commander of Southern Group who was marching with number 2 Column decided to use the branch line running due west from Kyaikthin as the quickest and easiest means of approaching the main railway line.

Failing, apparently, to realise how quickly the Japanese would learn of his movement down the railway line, he marched in broad daylight from the 6th milestone to within three miles of Kyaikthin where he bivouacked in the afternoon only 200 yards from the railway line. The Japanese brought up an infantry company and ambushed the column when it started to file out at 21.30 hours. A good deal of confusion ensued during this encounter.

Towards the end of the fight the Column Commander (Emmett) erred in changing his operational rendezvous to the rear, an order that reached very few of his men. The parties that went forward to the original renezvous found no Column Commander and so continued on the Irrawaddy River. The majority straggled back to the Chindwin whither the Column Commander also marched. The Officer Commanding Southern Group (Alexander) with the bulk of the British troops continued to the Irrawaddy River where they joined Number One Column and the whole group crossed at Tagaung.

All ciphers of Southern Group and Column 2 were lost at the ambush, also Wingate's insignia of Brigadier which later made the Japanese believe that they had destroyed the main force and they took the trouble to drop a printed broadsheet announcing this fact on Column 5 as it too crossed the Irrawaddy at Tigyaing a week later. (Wingate had given his Brigadier insignia to Major J.B.Jefferies who impersonated the commander as part of the decoy plans for Southern Group, he later re-joined Wingate in late March and returned to India with the Brigadier in mid-April).

Column 1 had reached the railway at Kyaikhtn undetected, blew a bridge and laid a number of mines, before marching on to the Irrawaddy.

It is probably true to say that Brigadier Wingate was not overly impressed by the performance of the Gurkha troops on Operation Longcloth, perhaps with the exception of those led by Major Calvert in Column 3. The vast majority of Gurkha Columns 2 and 4 had returned to India after meeting the Japanese in combat, deciding on dispersal to the rear, rather than following the Brigadier's instruction to always move forward. He had also planned for Southern Group in it's entirety to liaise with a special scouting mission in the Kachin Hills led by Captain 'Fish' Herring. The rendezvous date of 29th March was missed by Colonel Alexander, but presumably this was only due to the unexpected action at Kyaikthin.

I feel that the criticism aimed at 3/2 Gurkha was extremely harsh, they were after all a very young and inexperienced battalion, who had endured many 'last minute' changes to both leadership and command. I do wonder if Wingate was sub-consciously venting his obvious frustrations against the Indian General Command and their overt lack of support for his Chindit program and theories. Did he take these out on the commanders of Gurkha columns in 1943?

For the record, here is a transcription from Brigadier Wingate's operational report in regard to the performance of Southern Group and in particular Column 2 in 1943.

During the 26/27th of February, Southern Group had had a supply drop near Yeshin village and then continued it's march towards the railway. On the 2nd March the Commander of Southern Group who was marching with number 2 Column decided to use the branch line running due west from Kyaikthin as the quickest and easiest means of approaching the main railway line.

Failing, apparently, to realise how quickly the Japanese would learn of his movement down the railway line, he marched in broad daylight from the 6th milestone to within three miles of Kyaikthin where he bivouacked in the afternoon only 200 yards from the railway line. The Japanese brought up an infantry company and ambushed the column when it started to file out at 21.30 hours. A good deal of confusion ensued during this encounter.

Towards the end of the fight the Column Commander (Emmett) erred in changing his operational rendezvous to the rear, an order that reached very few of his men. The parties that went forward to the original renezvous found no Column Commander and so continued on the Irrawaddy River. The majority straggled back to the Chindwin whither the Column Commander also marched. The Officer Commanding Southern Group (Alexander) with the bulk of the British troops continued to the Irrawaddy River where they joined Number One Column and the whole group crossed at Tagaung.

All ciphers of Southern Group and Column 2 were lost at the ambush, also Wingate's insignia of Brigadier which later made the Japanese believe that they had destroyed the main force and they took the trouble to drop a printed broadsheet announcing this fact on Column 5 as it too crossed the Irrawaddy at Tigyaing a week later. (Wingate had given his Brigadier insignia to Major J.B.Jefferies who impersonated the commander as part of the decoy plans for Southern Group, he later re-joined Wingate in late March and returned to India with the Brigadier in mid-April).

Column 1 had reached the railway at Kyaikhtn undetected, blew a bridge and laid a number of mines, before marching on to the Irrawaddy.

Wingate was clearly unhappy with the decision made by Major Emmett to return to India after the clash at Kyaikthin and the fact that the unit had marched so blatantly up the railway line on March 2nd. There is an inference within the report that he lays the blame for this at Colonel Alexander's door. Judging from what I have read on this matter, three things come to mind in answering this question:

Firstly, it is quite clear that, although Alexander was ultimately in charge of Southern Group, he had consistently allowed his Column Commanders to lead and make their own decisions, something all good managers must learn to do to create trust within his team. Secondly, it may well be true that Column 2 decided to return to India, but the Colonel himself took his men forward in the agreed manner and stuck firmly to the immediate plan. The complaint that the column had marched openly along the railway that fateful day puzzles me somewhat, was it not true that the whole essence of Southern Group had been to act as decoy in 1943, perhaps the men were merely continuing this trend as they approached Kyaikthin. Sadly, it is unlikely we shall ever know.

The views of Major George Dunlop are of some considerable interest, especially as the Longcloth pathway of Colonel Alexander was so closely intertwined with this officer. After the operation was over Dunlop and Wingate met, more by accident than design and a heated discussion took place which ended with Wingate telling the Major, "well we don't want to wash our dirty linen in public, do we". Dunlop had always felt that Wingate had sent Southern Group into Burma as a sacrificial lamb and the decision to send the unit further on and over the Irrawaddy tantamount to a "death sentence".

One thing mentioned by Dunlop in his debrief notes was that there had been a cine-film taken of Southern Group as they moved over the Chindwin River in February 1943 and more filming of column activities took place as the days went by. This footage was lost somewhere along the way, possibly at Kyaikthin, it is a great shame that we will never have the chance to view such a priceless visual resource.

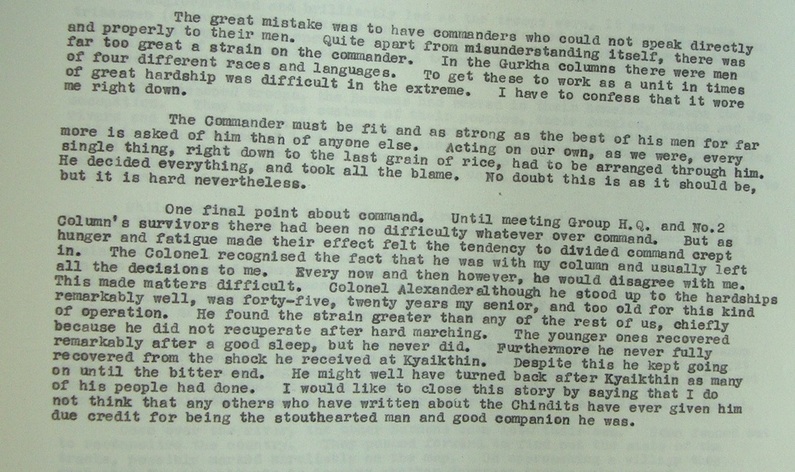

Below is a very interesting comment made by George Dunlop on debrief in regard to his experiences as a Column Commander, including views on the difficulties in communicating with Gurkha troops and a compassionate appraisal of Leigh Artbuthnot Alexander.

Firstly, it is quite clear that, although Alexander was ultimately in charge of Southern Group, he had consistently allowed his Column Commanders to lead and make their own decisions, something all good managers must learn to do to create trust within his team. Secondly, it may well be true that Column 2 decided to return to India, but the Colonel himself took his men forward in the agreed manner and stuck firmly to the immediate plan. The complaint that the column had marched openly along the railway that fateful day puzzles me somewhat, was it not true that the whole essence of Southern Group had been to act as decoy in 1943, perhaps the men were merely continuing this trend as they approached Kyaikthin. Sadly, it is unlikely we shall ever know.

The views of Major George Dunlop are of some considerable interest, especially as the Longcloth pathway of Colonel Alexander was so closely intertwined with this officer. After the operation was over Dunlop and Wingate met, more by accident than design and a heated discussion took place which ended with Wingate telling the Major, "well we don't want to wash our dirty linen in public, do we". Dunlop had always felt that Wingate had sent Southern Group into Burma as a sacrificial lamb and the decision to send the unit further on and over the Irrawaddy tantamount to a "death sentence".

One thing mentioned by Dunlop in his debrief notes was that there had been a cine-film taken of Southern Group as they moved over the Chindwin River in February 1943 and more filming of column activities took place as the days went by. This footage was lost somewhere along the way, possibly at Kyaikthin, it is a great shame that we will never have the chance to view such a priceless visual resource.

Below is a very interesting comment made by George Dunlop on debrief in regard to his experiences as a Column Commander, including views on the difficulties in communicating with Gurkha troops and a compassionate appraisal of Leigh Artbuthnot Alexander.

On the 29th March when Wingate ordered his columns to withdraw to India, Column 1 were six miles west of Mongmit. In the morning Lt.-Colonel Alexander ordered all but seven mules to be set free and all heavy equipment to be hidden or destroyed. Wingate had sent the unit a message which read, 'remember Lot's wife, return not whence you came. Seek salvation in the mountains'. He was pointing Southern Group in the direction of the Kachin Hills on the Chinese Yunnan Province borders. Flight Lieutenant John K. Edmonds said of the Colonel, "he (Alexander) used to look bemused by the 'old man's' (Wingate) biblical references, but he always attempted to carry out whatever they inferred". (This is a paraphrased quote from something Denis Gudgeon once told me in 2008).

From 'Safer than a Known Way', written by Lieutenant Ian MacHorton: "My particular job was that of commander of the Support Platoon in number 2 Column. With number 1 Column we were the lucky fellows chosen as the decoys! Looking back, I fail to see how we in those two columns so confidently, even light-heartedly, took on the task of literally inviting the vicious and cock-a-hoop Japanese to attack us and test their mettle against ours. Put it down, if you like, to the magic of Wingate and the complete trust he inspired in men".

Also from MacHorton's book comes this description of when Colonel Alexander had to make the difficult decision to leave behind the recently wounded young officer: "As I looked up again at Colonel Alexander I realised that he knew the answer even better than my conscience did. Firmly he rested his hand on my shoulder. I knew that what he was about to do could not have come easily to him. "I know what you're thinking my boy", said the Colonel, his voice soft with compassion. "Do you think you can possibly keep up?" (MacHorton had been badly injured in the hip area and there was no chance of him being able to carry on the column march). Wanting to answer his commanders question MacHorton remembers, "I saw nothing but pity and a deep understanding in the Colonel's eyes. Also behind the pity there was exhaustion, the unutterable tiredness and frayed-nerves look which told of the great burden of responsibility weighing down upon him and which had been on him for many weeks now in the midst of the jungle".

Here is how Ian MacHorton recalls the last moments of Colonel Alexander's life in the confusion of the Mu River crossing: "There was no deep cover immediately around us. We were in open teak forest with low bushes dotting the sandy soil. We raced on. Through the trees I caught a glimpse of Eddie Edmonds dashing across a clearing with the inert figure of Colonel Alexander hanging limply over his shoulder. The Colonel was mottled red with his own blood and flopped about lifelessly over the powerful frame of Edmonds. Another figure, who it was I never made out clearly, running desperately behind him, suddenly slumped down in his tracks and rolled over and over". (This man could well have been Victor De La Rue).

Another author to mention L.A. Alexander in writing was Robin Painter, a Signals Officer who found himself part of Southern Group as a last minute addition to the unit in mid-February 1943. He remembers Alexander (or Alex to those who truly got to know him) as a man with a pleasant but business-like manner, who had acted as his mentor during those early weeks in the Burmese jungle. He states in his book 'A Signal Honour': "Colonel Alex received me with courtesy but some surprise, for he was not expecting a young Second Lieutenant from Royal Signals to join him as a reinforcement, especially at this late stage. As we marched along he questioned me about my background, he told me that he would be glad to have me provided I made myself useful, he also said it was too late to send me back anyway and that the experiences of the weeks to come would no doubt do me a lot of good".

Denis Gudgeon remembered Colonel Alexander along with George Silcock (second officer to Mike Calvert in Column 3) as: "two of the most honourable and charming gentlemen I have ever met in Army uniform, always, always putting their Gurkhas first, foremost and above everything else".

Something else that Denis had been told by George Silcock, was that the Colonel had always insisted that the officers were not to sit down to eat before knowing that the men were comfortable and had their food first. This rule had been adhered to not just in barracks, but in Chindit training and as far as was possible even in Burma. Silcock had mentioned that Alexander was often the last man to receive his food on column halts and in evening bivouac. He (Alexander) was also extremely insistent that the Gurkhas never left their rifles unattended at any point during training or on the operation, this was a Regimental obsession that had been born out of their time on the Northwest Frontier in the years between the wars. Local frontier tribesmen had always looked upon the British Lee Enfield Rifle as the best weapon of it's kind and would go to great lengths to acquire one, usually by robbing the unsuspecting Gurkha of his arm. This would then bring great disgrace upon the regiment in question and the soldier in particular.

Another story from these website pages which touches on the participation of Colonel Alexander in 1943 can be seen here:

The Interrogation of Jagbahadur Gurung

L.A. Alexander pre-WW2.

I have been fortunate to receive no fewer than three contact enquiries looking for information about Colonel Alexander. The first of these came in early 2011, when grandson Bruce Luxmoore got in touch:

Hi Steve,

I was surfing around trying to learn more about my grandfather's exploits in Burma and found your very informed responses on the Burma Star Association Forum. My grandfather was Lt. Col. L.A. Alexander and he led the Southern Group in the 1943 Operation Longcloth. My brothers and I have learned a bit about his involvement in this campaign from books; 'Safer than a Known Way' and 'A Signal Honour'. We would be really interested in learning more, accessing pictures etc. I am thinking of paying a few dollars to get his military records, I am not sure if you have an opinion on that process. Anyway, any info would be greatly appreciated."

Bruce and I have shared one or two more emails over the last 18 months or so, including him sending me some of the photos of his grandfather used to illustrate this story. On discovering the debrief notes of Major Dunlop (in the late summer of 2012) which are held at the National Archives, the full story of what happened to Colonel Alexander finally came to light. This is how Bruce responded to hearing the details of his grandfather's last moments:

Steve, thank you. I am interested in all details related to my grandfather's experience, I see the pain involved as a blessing to ensure I don't take his (and so many others) sacrifice for granted.

This year (2013), I was contacted by another of the grandchildren, Bruce's cousin Jane. This what she had to tell me about her grandfather:

There must be so many people like us that never got the chance to know their Grandparents, strange when you think that Leigh was killed only 15 years before I was born, I wish I had the chance to know him but am finding it very interesting to know these bits now. Thank you for all your hard work towards it too, I very much appreciate it. Strange, feeling really proud and sad at the same time. Leigh had three children, my father Nigel, Bruce's mum Verity and their brother Vernon. Dad never really spoke about his father, and of course Gran emigrated to Canada.

Jane also told me that she had recently visited the Gurkha Museum at Winchester, where she was able to find out more information about her grandfather, we are hoping to meet one day soon to discuss matters further. The Gurkha Museum is somewhere that I have been looking to visit for a good while now, but annoyingly the chance just hasn't arisen as yet. Jane did have one small anecdote about her grandfather and his time in India before the war:

When Leigh was a Captain in India, someone broke in to his residence and tried to kill him, my Gran threw bed clothes over the intruder, Leigh grappled with him and then turned him over to the police. Amazing! I wonder if this might have happened over on the Northwest Frontier, as it sounds like something that a Pathan Hill tribesmen would attempt to do in the days before WW2.

The final contact came just before I began to write this story, it was from Kevin Hills who is a friend of James Luxmoore (Bruce's brother). Kevin has been searching for information about L.A. Alexander for several years and had come across my website just recently:

My interest in the Chindits, specifically the First Expedition, came by chance when visiting a friend who showed me his Grandfather's medals. The Grandfather is Lt. Col. LA Alexander, 3/2 Gurkhas, and killed during Longcloth. I trawled the internet 8 to 10 years ago and only came up with a small amount of information. From the reading I did it looked like Wingate's 'Report on Operations' would be a good reference, however, there appear to only be edited copies out there. Have you seen a full version? I hoped it would show Alexander's path and possibly illuminate how he was killed.

I look forward to following your excellent website and learning more about Operation Longcloth and especially Colonel Alexander. I am a light weight military researcher for friends and family, and enjoy the multitude of persons and places a bit of modest research can bring me to. I just found Alexander to be a mystery given his rank and position in the operation. As a career officer who was put into the role of second in command, then killed in action, he seems to have been abandoned by history. I will stand by patiently and await your article on Alexander.

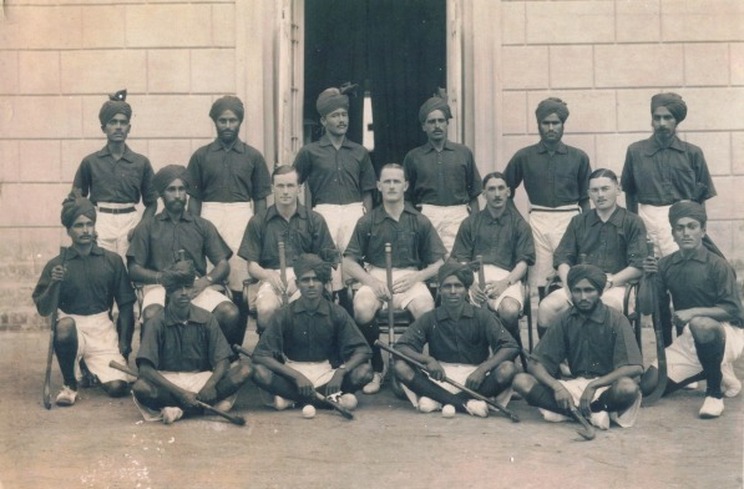

My thanks go to everyone who has helped me put together this account of Lt. Colonel Leigh Arbuthnot Alexander and his time as a Chindit in 1942/43. Special thanks must go to his grandchildren Bruce, Jane and James for their contributions, sadly they never had the chance to meet this loyal, steadfast and courageous man. The final image seen below shows the then Captain Alexander as part of an inter-regimental hockey team in the years before World War Two, I include this image not simply for interests sake, but as a visual example of his strong team mentality and to remind us of how hard he tried to keep his team together in the jungles of Burma.

My final thanks must go to my good friend Enes, whose help in regard to Gurkha Regimental information and history has been invaluable.

Hi Steve,

I was surfing around trying to learn more about my grandfather's exploits in Burma and found your very informed responses on the Burma Star Association Forum. My grandfather was Lt. Col. L.A. Alexander and he led the Southern Group in the 1943 Operation Longcloth. My brothers and I have learned a bit about his involvement in this campaign from books; 'Safer than a Known Way' and 'A Signal Honour'. We would be really interested in learning more, accessing pictures etc. I am thinking of paying a few dollars to get his military records, I am not sure if you have an opinion on that process. Anyway, any info would be greatly appreciated."

Bruce and I have shared one or two more emails over the last 18 months or so, including him sending me some of the photos of his grandfather used to illustrate this story. On discovering the debrief notes of Major Dunlop (in the late summer of 2012) which are held at the National Archives, the full story of what happened to Colonel Alexander finally came to light. This is how Bruce responded to hearing the details of his grandfather's last moments:

Steve, thank you. I am interested in all details related to my grandfather's experience, I see the pain involved as a blessing to ensure I don't take his (and so many others) sacrifice for granted.

This year (2013), I was contacted by another of the grandchildren, Bruce's cousin Jane. This what she had to tell me about her grandfather:

There must be so many people like us that never got the chance to know their Grandparents, strange when you think that Leigh was killed only 15 years before I was born, I wish I had the chance to know him but am finding it very interesting to know these bits now. Thank you for all your hard work towards it too, I very much appreciate it. Strange, feeling really proud and sad at the same time. Leigh had three children, my father Nigel, Bruce's mum Verity and their brother Vernon. Dad never really spoke about his father, and of course Gran emigrated to Canada.

Jane also told me that she had recently visited the Gurkha Museum at Winchester, where she was able to find out more information about her grandfather, we are hoping to meet one day soon to discuss matters further. The Gurkha Museum is somewhere that I have been looking to visit for a good while now, but annoyingly the chance just hasn't arisen as yet. Jane did have one small anecdote about her grandfather and his time in India before the war:

When Leigh was a Captain in India, someone broke in to his residence and tried to kill him, my Gran threw bed clothes over the intruder, Leigh grappled with him and then turned him over to the police. Amazing! I wonder if this might have happened over on the Northwest Frontier, as it sounds like something that a Pathan Hill tribesmen would attempt to do in the days before WW2.

The final contact came just before I began to write this story, it was from Kevin Hills who is a friend of James Luxmoore (Bruce's brother). Kevin has been searching for information about L.A. Alexander for several years and had come across my website just recently:

My interest in the Chindits, specifically the First Expedition, came by chance when visiting a friend who showed me his Grandfather's medals. The Grandfather is Lt. Col. LA Alexander, 3/2 Gurkhas, and killed during Longcloth. I trawled the internet 8 to 10 years ago and only came up with a small amount of information. From the reading I did it looked like Wingate's 'Report on Operations' would be a good reference, however, there appear to only be edited copies out there. Have you seen a full version? I hoped it would show Alexander's path and possibly illuminate how he was killed.

I look forward to following your excellent website and learning more about Operation Longcloth and especially Colonel Alexander. I am a light weight military researcher for friends and family, and enjoy the multitude of persons and places a bit of modest research can bring me to. I just found Alexander to be a mystery given his rank and position in the operation. As a career officer who was put into the role of second in command, then killed in action, he seems to have been abandoned by history. I will stand by patiently and await your article on Alexander.

My thanks go to everyone who has helped me put together this account of Lt. Colonel Leigh Arbuthnot Alexander and his time as a Chindit in 1942/43. Special thanks must go to his grandchildren Bruce, Jane and James for their contributions, sadly they never had the chance to meet this loyal, steadfast and courageous man. The final image seen below shows the then Captain Alexander as part of an inter-regimental hockey team in the years before World War Two, I include this image not simply for interests sake, but as a visual example of his strong team mentality and to remind us of how hard he tried to keep his team together in the jungles of Burma.

My final thanks must go to my good friend Enes, whose help in regard to Gurkha Regimental information and history has been invaluable.

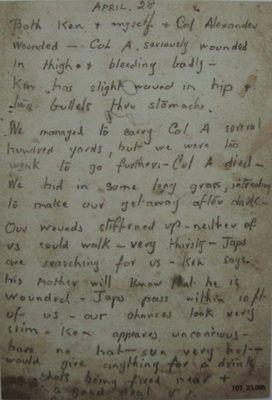

Reverse of the postcard used by Edmonds in 1943.

Update 19/01/2013.

As mentioned earlier in this story Flight Lieutenant John Kingsley Edmonds was centrally placed at the time of Colonel Alexander's death. He was close by when the Commander was wounded and with the help of others around him carried the now dying officer into the cover of some nearby woods. One of those other men turned out to be Flight Sergeant Kenneth Wyse, who like Edmonds, was part of the Air Liaison section of Column 1 on Operation Longcloth.

Edmonds and Wyse had built up a strong friendship during their time in Burma, and this would help them through the arduous weeks to come after their capture by the Japanese on the 28th April 1943. The image seen opposite (left) is the reverse of a postcard which belonged to Ken Wyse, this, along with three other cards was used by Edmonds to record the time line from their initial capture near the Mu River, right up until Ken's death in Rangoon Jail on the 21st August.

At one point in Rangoon the guards actually confiscated these cards, but remarkably they were returned to Edmonds after he had made an official complaint to the commandant of the jail.

Here is the transcription from the card, which understandibly gives only a brief outline of the circumstances which took place on the 28th April 1943:

Both Ken and myself (Edmonds) and Col. Alexander wounded. Col. A. seriously wounded in thigh and bleeding badly. Ken has a slight wound in the hip and two bullets thru stomach.

We managed to carry Col. A. several hundred yards, but we were too weak to go further, Col. A. died. We hid in some long grass, intending to make our getaway after dark. Our wounds stiffened up, neither of us could walk, very thirsty, Japs are searching for us. Ken says his mother will know that he is wounded. Japs pass within 10ft of us, our chances look very slim. Ken appears unconscious, have no hat, sun very hot, would give anything for a drink. Shots being fired near and a good deal……..

I have replaced the dash marks used by Edmonds on the page, with commas or full stops in order for the sentences to make more grammatical sense, otherwise it is a true transcription of the postcard. The end line frustratingly peters out mid-sentence.

As an epitaph to this update; Flight Lieutenant Edmonds kept these postcards safely hidden away during his two years as a POW in Rangoon Jail, after the war ended he took the trouble of paying the family of Kenneth Wyse a personal visit, where he handed back the cards and told them what had happened to their brave son in 1943.

Update 08/12/2013.

Subedar-Major Siblal Thapa was with Colonel Alexander for the vast majority of his time in Burma during 1943. After returning to India in mid-May the Gurkha Officer wrote down his experiences in the form of a narrative diary which was published in the Regimental Newsletter some months later. Siblal was originally in Chindit Column 2 and had collected together the remnants of this unit after their disastrous contact with the enemy at Kyaikthin. He had taken this group, comprising of about 100 men, eastward toward the formally agreed rendezvous point, but had found no one else present, eventually he met up with Colonel Alexander's small party and later on this combined group joined Major Dunlop and Column1.

Here is an extract from Siblal's narrative which describes the confused time just before the Column reached the Irrawaddy River at a place called Singyat.

After securing some more rice at a small village we marched on towards the Irrawaddy. We reached the village of Singyat, where the locals told us that there was a company of Japs 5 miles to the north and another 5 miles to the south of the village. They said they could give us no boats as these had been confiscated by the enemy.

The Colonel held a conference and it was decided that he and Major Dunlop would attempt to cross the river and push on to India, leaving Lt. Clarke in charge of the remainder of the Column. Forty strong swimmers were selected and formed into two parties, one under the Colonel, the other under the command of Major Dunlop.

At that point Lt. Chit Khin of the Burma Rifles arrived and reported that he had secured two small fishing boats which might carry as many as 30 men over at a time. The Colonel decided to continue with his plan and at 1830 hrs. moved down to the river bank.

Barely a half-hour later Subedar Padanbahadur Rai and his party of 59 men re-joined us. This group had been lost to us a few days earlier and had previously made up the Defence Platoon for Southern Group Brigade HQ.

Subedar Padanbahadur Rai leading his Defence Platoon during expedition was effectively Colonel Alexander's bodyguard at the outset of Operation Longcloth. Each Column Commander also had a selected band of Gurkhas to be their ultimate protection should the enemy ever come near. I wonder how Padan had ever got separated from his commander in the first instance?

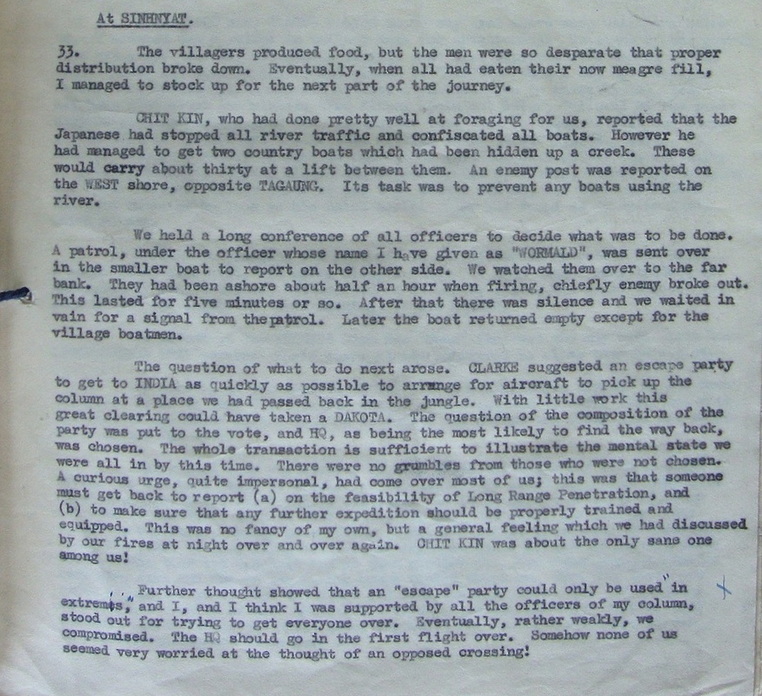

Whether Colonel Alexander and George Dunlop actually swam the Irrawaddy at this time is unclear, however Dunlop did write about this discussion in his debrief notes. Shown below is a section of these notes, which explains both the thoughts and the mental state of the command group at that time.

As mentioned earlier in this story Flight Lieutenant John Kingsley Edmonds was centrally placed at the time of Colonel Alexander's death. He was close by when the Commander was wounded and with the help of others around him carried the now dying officer into the cover of some nearby woods. One of those other men turned out to be Flight Sergeant Kenneth Wyse, who like Edmonds, was part of the Air Liaison section of Column 1 on Operation Longcloth.

Edmonds and Wyse had built up a strong friendship during their time in Burma, and this would help them through the arduous weeks to come after their capture by the Japanese on the 28th April 1943. The image seen opposite (left) is the reverse of a postcard which belonged to Ken Wyse, this, along with three other cards was used by Edmonds to record the time line from their initial capture near the Mu River, right up until Ken's death in Rangoon Jail on the 21st August.

At one point in Rangoon the guards actually confiscated these cards, but remarkably they were returned to Edmonds after he had made an official complaint to the commandant of the jail.

Here is the transcription from the card, which understandibly gives only a brief outline of the circumstances which took place on the 28th April 1943:

Both Ken and myself (Edmonds) and Col. Alexander wounded. Col. A. seriously wounded in thigh and bleeding badly. Ken has a slight wound in the hip and two bullets thru stomach.

We managed to carry Col. A. several hundred yards, but we were too weak to go further, Col. A. died. We hid in some long grass, intending to make our getaway after dark. Our wounds stiffened up, neither of us could walk, very thirsty, Japs are searching for us. Ken says his mother will know that he is wounded. Japs pass within 10ft of us, our chances look very slim. Ken appears unconscious, have no hat, sun very hot, would give anything for a drink. Shots being fired near and a good deal……..

I have replaced the dash marks used by Edmonds on the page, with commas or full stops in order for the sentences to make more grammatical sense, otherwise it is a true transcription of the postcard. The end line frustratingly peters out mid-sentence.

As an epitaph to this update; Flight Lieutenant Edmonds kept these postcards safely hidden away during his two years as a POW in Rangoon Jail, after the war ended he took the trouble of paying the family of Kenneth Wyse a personal visit, where he handed back the cards and told them what had happened to their brave son in 1943.

Update 08/12/2013.

Subedar-Major Siblal Thapa was with Colonel Alexander for the vast majority of his time in Burma during 1943. After returning to India in mid-May the Gurkha Officer wrote down his experiences in the form of a narrative diary which was published in the Regimental Newsletter some months later. Siblal was originally in Chindit Column 2 and had collected together the remnants of this unit after their disastrous contact with the enemy at Kyaikthin. He had taken this group, comprising of about 100 men, eastward toward the formally agreed rendezvous point, but had found no one else present, eventually he met up with Colonel Alexander's small party and later on this combined group joined Major Dunlop and Column1.

Here is an extract from Siblal's narrative which describes the confused time just before the Column reached the Irrawaddy River at a place called Singyat.

After securing some more rice at a small village we marched on towards the Irrawaddy. We reached the village of Singyat, where the locals told us that there was a company of Japs 5 miles to the north and another 5 miles to the south of the village. They said they could give us no boats as these had been confiscated by the enemy.

The Colonel held a conference and it was decided that he and Major Dunlop would attempt to cross the river and push on to India, leaving Lt. Clarke in charge of the remainder of the Column. Forty strong swimmers were selected and formed into two parties, one under the Colonel, the other under the command of Major Dunlop.

At that point Lt. Chit Khin of the Burma Rifles arrived and reported that he had secured two small fishing boats which might carry as many as 30 men over at a time. The Colonel decided to continue with his plan and at 1830 hrs. moved down to the river bank.

Barely a half-hour later Subedar Padanbahadur Rai and his party of 59 men re-joined us. This group had been lost to us a few days earlier and had previously made up the Defence Platoon for Southern Group Brigade HQ.

Subedar Padanbahadur Rai leading his Defence Platoon during expedition was effectively Colonel Alexander's bodyguard at the outset of Operation Longcloth. Each Column Commander also had a selected band of Gurkhas to be their ultimate protection should the enemy ever come near. I wonder how Padan had ever got separated from his commander in the first instance?

Whether Colonel Alexander and George Dunlop actually swam the Irrawaddy at this time is unclear, however Dunlop did write about this discussion in his debrief notes. Shown below is a section of these notes, which explains both the thoughts and the mental state of the command group at that time.

So, as you can plainly see the situation was difficult and very confused and was not helped by the poor state of health, both physically and mentally of the men in charge. Having ultimately succeeded in crossing the Irrawaddy at this point, it was not very long before events turned catastrophic for the leadership of Southern Group. My thanks must go to the Gurkha Museum at Winchester for their help and co-operation in regards to this update.

Update 21/08/2014.

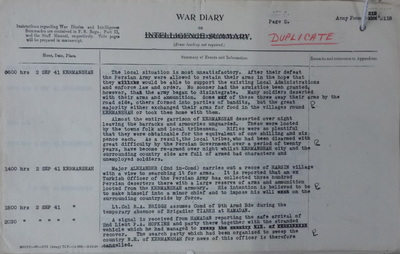

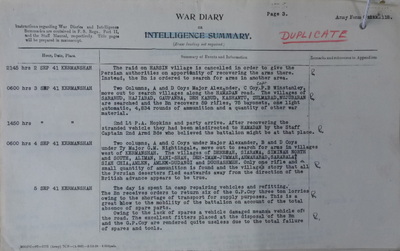

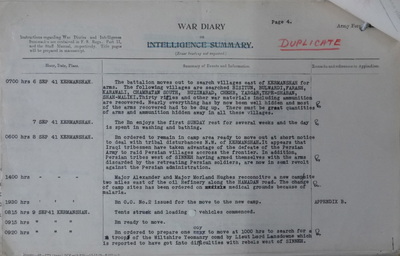

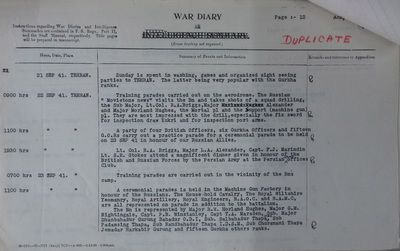

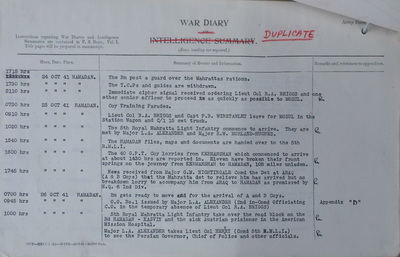

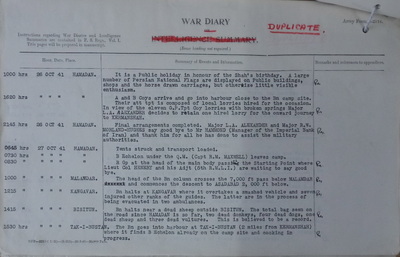

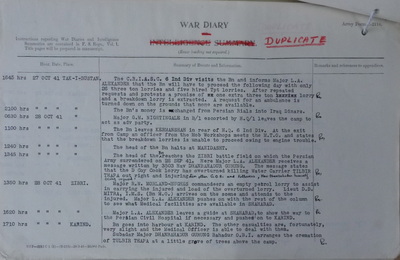

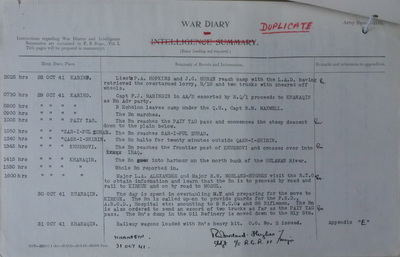

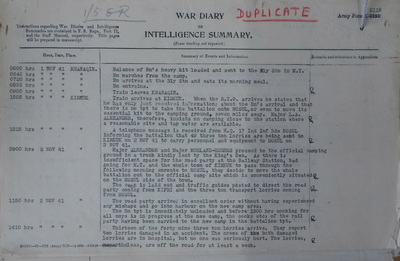

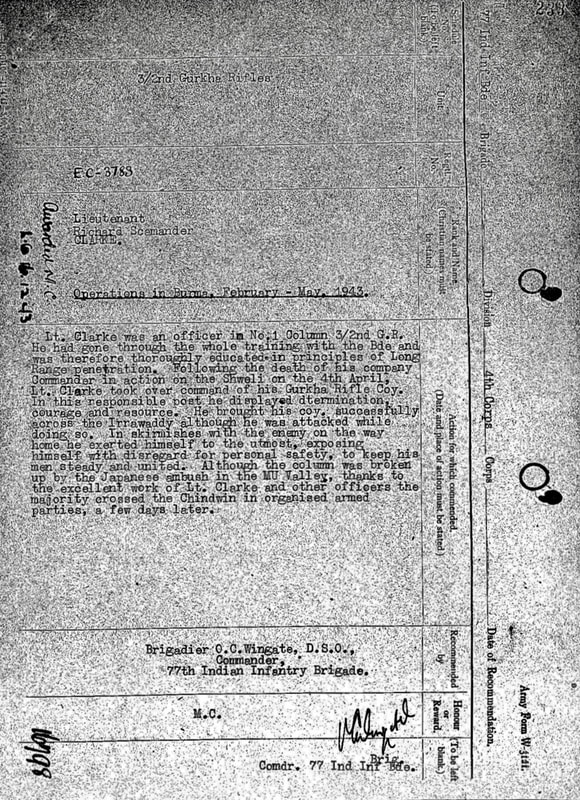

Before moving over to command the third battalion of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles, Colonel Alexander, then holding the rank of Major, was part of the upper command structure for the first battalion of the 5th Royal Gurkha Rifles (Frontier Force). By September 1941 the battalion were stationed in Persia (present day Iran) at a place called Kermanshah.

During the course of the next few weeks the unit moved around the Middle East theatre, finally ending up at Mosul in Iraq in the early part of November. Political manoeuvrings by the Germans attempting to destabilise the region at this time had failed to bear fruit, but the British decided to deploy Army units such as the 1/5 GR to ensure the security of the area and of course the protection of the crucial oilfields.

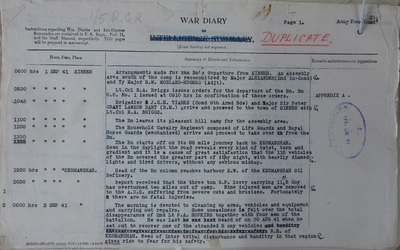

Featured below are some of the pages from the 1/5 Gurkha Rifles War diary for the period, showing Major Alexander's involvement at that time. Please click on any of the images to bring them forward on the page.

Update 10/05/2016.

I recently received an email contact from Rory Luxmoore, grandson of Lieutenant Colonel Leigh Alexander. Rory told me that he and his family had just visited Burma, which included a pilgrimage to Taukkyan War Cemetery to pay their respects at the grave of his grandfather. As part of their visit, the family left beside the grave a short biography of Colonel Alexander's life and some photographs.

Rory told me:

Steve, here are some photographs from our trip on the 23rd March 2016, to the grave of my grandfather at Taukkyan War Cemetery in Yangon, Myanmar. It was an emotional moment for us all and I believe an important experience for my two children.

Shown below is the most recent photograph of Colonel Alexander's grave plaque at Taukkyan, which was taken by Rory during his visit to the cemetery.

I recently received an email contact from Rory Luxmoore, grandson of Lieutenant Colonel Leigh Alexander. Rory told me that he and his family had just visited Burma, which included a pilgrimage to Taukkyan War Cemetery to pay their respects at the grave of his grandfather. As part of their visit, the family left beside the grave a short biography of Colonel Alexander's life and some photographs.

Rory told me:

Steve, here are some photographs from our trip on the 23rd March 2016, to the grave of my grandfather at Taukkyan War Cemetery in Yangon, Myanmar. It was an emotional moment for us all and I believe an important experience for my two children.

Shown below is the most recent photograph of Colonel Alexander's grave plaque at Taukkyan, which was taken by Rory during his visit to the cemetery.

Update 30/04/2024.

Tim Coppin

In May 2023, I was delighted to receive an email contact from Tim Coppin, the grandson of Gilbert William Arbuthnot Alexander, elder brother of Leigh Arbuthnot Alexander. Tim, who lives in Australia has undertaken to write the Alexander family history and was keen to include some of the information I had collected together in regards Lt. Colonel Leigh Alexander and his unfortunate demise on the first Chindit expedition in 1943.

Over the past year, Tim and I have exchanged numerous emails to this end and I am very pleased and honoured that some of my research work has been included in the new family narrative. I would like to thank Tim for his initial contact and for allowing me to contribute to and learn more about his family and in particular Gilbert and Leigh Alexander. It is incredible to think that over the past 12 years or so, no fewer than four direct descendants of the Alexander family have been in contact with me in relation to my website pages.

The photograph to the left, shows 2nd Lieutenant Gilbert William Arbuthnot Alexander dressed in the uniform of the Gordon Highlanders (circa 1914). Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

Tim Coppin

In May 2023, I was delighted to receive an email contact from Tim Coppin, the grandson of Gilbert William Arbuthnot Alexander, elder brother of Leigh Arbuthnot Alexander. Tim, who lives in Australia has undertaken to write the Alexander family history and was keen to include some of the information I had collected together in regards Lt. Colonel Leigh Alexander and his unfortunate demise on the first Chindit expedition in 1943.

Over the past year, Tim and I have exchanged numerous emails to this end and I am very pleased and honoured that some of my research work has been included in the new family narrative. I would like to thank Tim for his initial contact and for allowing me to contribute to and learn more about his family and in particular Gilbert and Leigh Alexander. It is incredible to think that over the past 12 years or so, no fewer than four direct descendants of the Alexander family have been in contact with me in relation to my website pages.

The photograph to the left, shows 2nd Lieutenant Gilbert William Arbuthnot Alexander dressed in the uniform of the Gordon Highlanders (circa 1914). Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 18/12/2020.

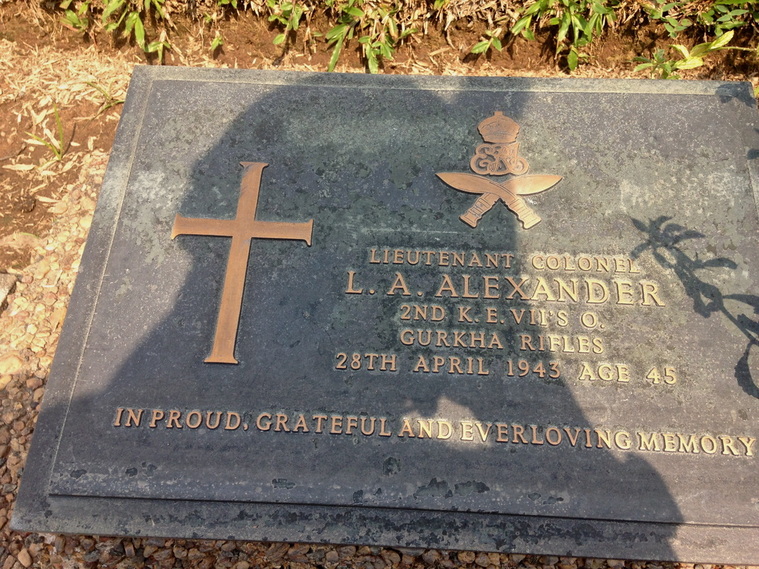

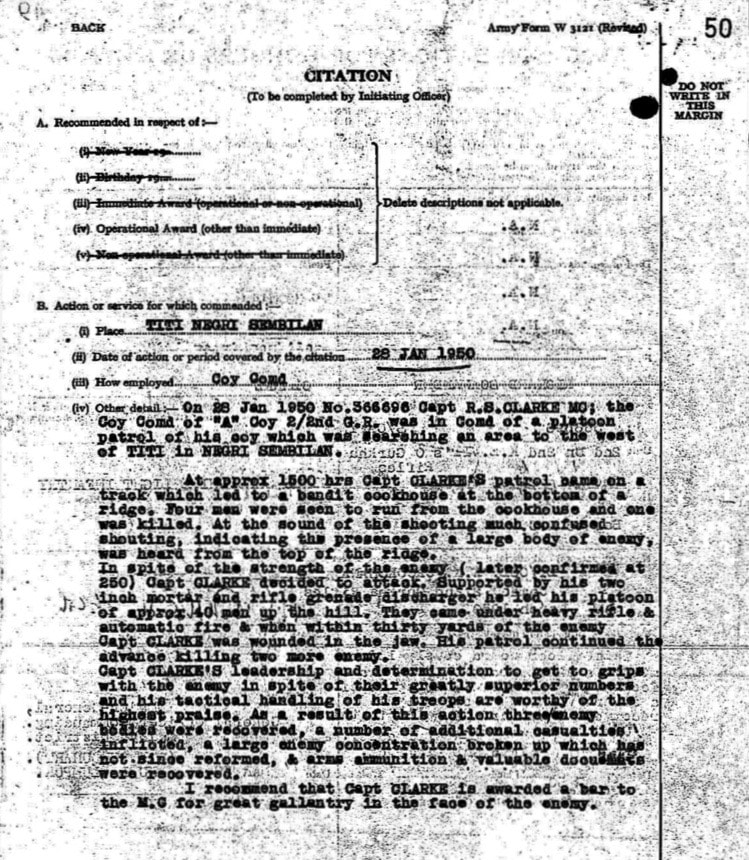

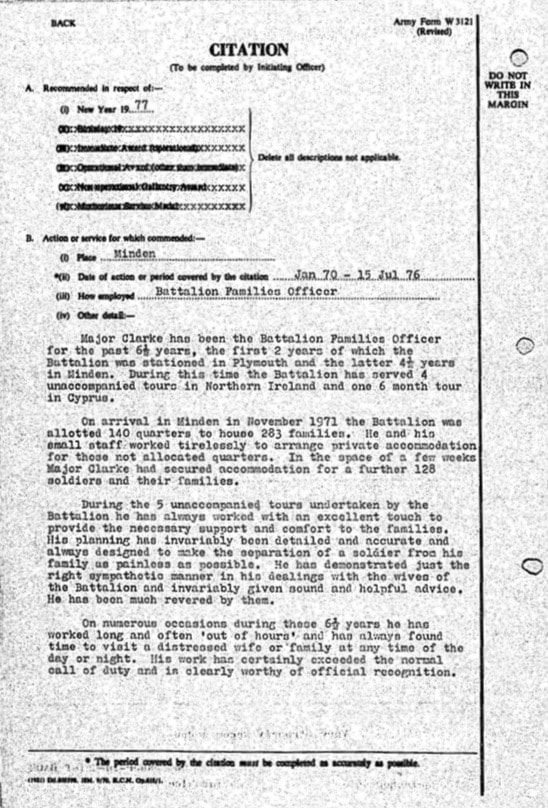

Lt. Richard Scamander Clarke

I fortunate recently to be sent a number of documents and papers in relation to some of the men that served on Operation Longcloth. This included a short memoir written by Lt. Dicky Clarke MC, who was part of No. 1 Column on the first Wingate expedition and who played a significant role during the column's return journey to India in April/May that year. I believe the narrative set out below was first published in one of the Regiment of Gurkhas annual journals, but there is no means to identify which one or when from the papers I have.

Richard Scamander Clarke was born on the 15th July 1921 and was the son of Major Percy Scamander Clarke MC and Violet Ethel Gresham Nicholson from Bexhill-on-Sea in Sussex. From the pages of the London Gazette it seems that Richard had begun his wartime service with the Royal Artillery as a Gunner, but took up an opportunity to join the Indian Army as an Officer Cadet in 1941.

He was commissioned with the Army number, EC-3783 in September 1941 from the Officer Training School in Bangalore and posted to the 2nd Gurkha Rifles based at the time in Baluchistan. He served on Operation Longcloth in No. 1 Column under the command of Major George Dickson Dunlop MC and worked in particular with fellow Gurkha officer, Major Vivian Weatherall. The following year he remained with the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles and served as a company commander with the battalion in the Arakan region of Burma. Subsequently he served with the Gurkhas and the King's Shropshire Light Infantry in Malaya where he was also wounded, Mentioned in Despatches and awarded a bar to his MC. He joined the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry in 1950 and also served with the Durham Light Infantry in Korea, before retiring in 1976.

What I Remember, by Dicky Clarke

The last message we got from Wingate before we abandoned our mules was seek freedom in the hills. We were by then in the foothills east of the Irrawaddy.

About an hour after we left the mules we heard the Japs mortaring the position thinking we were still there. We took Wingate's advice as there was no alternative and we climbed up higher and higher in an easterly direction. We rested on the top of a wooded ridge and while we were there the Japs caught up with us but we had them pinned down on the forward slope of the hill leading to the ridge we were on. I remember Vivian Weatherell who commanded our Gurkha Company, A Company of No. 1 Column, move forward so that he could overlook the slope the Japs were on and empty his tommy gun into them, swearing appropriately in Gurkhali as he did so.

We knew it would not be long before enemy reinforcements arrived and decided we had better not dawdle but try and cross the main road before we were cut off. So we mounted our 3 inch mortar and fired off all our bombs on the slope the Japs were on and then continued our march eastwards having radioed for fighter air support before abandoning the wireless set, the mortars and the mules that had carried them.

We crossed the road safely which was a major artery between two towns occupied by the Japs and continued through mountainous country making for the Shweli River, which it was intended we would cross and make for China as we knew the Japs would be waiting for us at every turn if we tried to return the way we had come into Burma, with both the Irrawaddy and Chindwin rivers to recross before reaching home.

We had had our last supply drop a week or so ago and from now on we had to live off the country and this we did by obtaining what we could from the villages we passed through and of course, the Burmese platoon was invaluable for this end. We finally reached the Shweli River without encountering the Japs and we found that the river was only about thirty yards wide but very fast flowing and impossible to cross without help. So one or two good swimmers swam across with a line with the intention of making a rope of rifle slings. At !east this was the idea but no sooner had they crossed than the Japs arrived along the far bank and we had to abandon the idea. It was at this time Vivian Weatherell was killed by a Japanese machine gun from across the river.

There was no alternative but to give up the idea of making for China and we started on our return journey westwards instead. We reached the Irrawaddy almost intact but discovered the Japs had removed all the boats to the west bank of the river. A conference was held and it was decided to form an escape party of a few selected officers and men so that at least someone could get back to tell the tale. In the meantime two boats had been found which the villagers had sunk in order to hide them from the Japanese and that night most of the Column and Group Headquarters were paddled across the river, nearly a mile wide, in those two narrow boats which held about fifteen men each sitting jammed up behind each other. Luckily for us the Japs slept soundly that night but with the dawn they we were spotted and they shot up the last two boats leaving only a few men behind on the east bank.

So the column was not too depleted, but not long after we had set off westwards that morning we were well and truly ambushed, resulting in the death of Lt. Colonel Alexander, our Group Commander, Lieutenant George de !a Rue and others. Mortar bombs exploded all amongst us and we just made our way westwards through it all as best we could, visibility being very limited in that type of jungle country. The walking wounded had to keep up as best they could.

We seemed to wade for days down chaungs with steep vertical sides and on finally coming out into flatter country we would be ambushed and each time we got split into smaller and smaller parties. It was a fight against time as lack of food was in the end going to be the deciding factor. At one ambush site the Japanese had posted a notice describing how one could surrender and the remnants of the Commando Platoon almost to a man did exactly that. Of course, the Gurkhas survived much better on no or little rations than the British ranks.

On nearing the Chindwin River a few water buffaloes were seen grazing in paddy fields not far from a village on the river. It was decided to send a couple of Gurkhas to kill one with a kukri as to shoot would have given us away. But to our horror a shot rang out and one of the buffaloes hit the dust. It was now a question of out with the kukris and cut as much of it up and away before being spotted. Hardly had we started than a few Burmese, some armed with British .303 rifles came out of the jungle into the clearing. We parleyed with them to gain time and as we withdrew into the jungle again with some Gurkhas still on the buffalo the Japs arrived and opened up on the position with automatic weapons and mortars.

We made a detour through the jungle making for the river and lay up a few hundred yards from it. We distributed the buffalo meat as best we could amongst us, eating it raw and with relish. Our party then comprised George Dunlop who was the Column Commander, John Fowler and two other officers and about a dozen other ranks. Japs were seen patrolling the river along a track running parallel to it probably from the village that the buffaloes had belonged to. There seemed nothing for it but to try and cross the river that night, but how? It was decided that those who could swim should try and cross and those who couldn't would have to be left. John Fowler couldn't swim but he was given one of our issue water wings to make the attempt.

George Dunlop advised us not to wear our footwear but tie it round our necks which I didn't do. John Fowler got into difficulties a few yards out and one gallant officer helped him back to the bank before swimming over himself. The river was about 500 yards wide and I was surprised how easily I floated. I reached the west bank and found I was near George Dunlop whose boots had floated away with the current and for the next three days the two of us walked westwards, George bare footed. We ate raw paddy which we found in deserted huts in the fields. On the third day we to came to a river running westwards. We knew the Indian traitor army (INA) was about in those parts so we had to be careful and I was not in favour of walking along the track beside the river in case of ambush, but in the end weariness prevailed and we decided to do so come what may.

Suddenly, we heard a shout from across the river, come over this way, Sir. Oh well, I said to George at least we will get something to eat even if they are Japs. George waded across that river as if he had a new lease of life and I followed to be received not by Japs but our own side, an Indian Army unit, the Mahrattas, I think. We were safe once more!

Lt. Richard Scamander Clarke

I fortunate recently to be sent a number of documents and papers in relation to some of the men that served on Operation Longcloth. This included a short memoir written by Lt. Dicky Clarke MC, who was part of No. 1 Column on the first Wingate expedition and who played a significant role during the column's return journey to India in April/May that year. I believe the narrative set out below was first published in one of the Regiment of Gurkhas annual journals, but there is no means to identify which one or when from the papers I have.

Richard Scamander Clarke was born on the 15th July 1921 and was the son of Major Percy Scamander Clarke MC and Violet Ethel Gresham Nicholson from Bexhill-on-Sea in Sussex. From the pages of the London Gazette it seems that Richard had begun his wartime service with the Royal Artillery as a Gunner, but took up an opportunity to join the Indian Army as an Officer Cadet in 1941.

He was commissioned with the Army number, EC-3783 in September 1941 from the Officer Training School in Bangalore and posted to the 2nd Gurkha Rifles based at the time in Baluchistan. He served on Operation Longcloth in No. 1 Column under the command of Major George Dickson Dunlop MC and worked in particular with fellow Gurkha officer, Major Vivian Weatherall. The following year he remained with the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles and served as a company commander with the battalion in the Arakan region of Burma. Subsequently he served with the Gurkhas and the King's Shropshire Light Infantry in Malaya where he was also wounded, Mentioned in Despatches and awarded a bar to his MC. He joined the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry in 1950 and also served with the Durham Light Infantry in Korea, before retiring in 1976.

What I Remember, by Dicky Clarke

The last message we got from Wingate before we abandoned our mules was seek freedom in the hills. We were by then in the foothills east of the Irrawaddy.

About an hour after we left the mules we heard the Japs mortaring the position thinking we were still there. We took Wingate's advice as there was no alternative and we climbed up higher and higher in an easterly direction. We rested on the top of a wooded ridge and while we were there the Japs caught up with us but we had them pinned down on the forward slope of the hill leading to the ridge we were on. I remember Vivian Weatherell who commanded our Gurkha Company, A Company of No. 1 Column, move forward so that he could overlook the slope the Japs were on and empty his tommy gun into them, swearing appropriately in Gurkhali as he did so.

We knew it would not be long before enemy reinforcements arrived and decided we had better not dawdle but try and cross the main road before we were cut off. So we mounted our 3 inch mortar and fired off all our bombs on the slope the Japs were on and then continued our march eastwards having radioed for fighter air support before abandoning the wireless set, the mortars and the mules that had carried them.