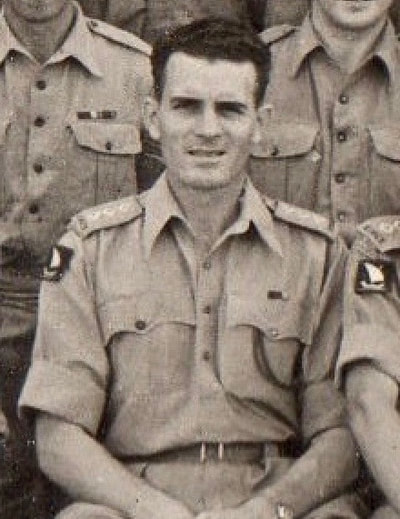

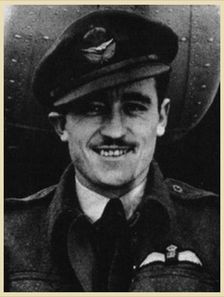

Lieutenant Gerry Roberts

Cap badge of the Welsh Guards.

Cap badge of the Welsh Guards.

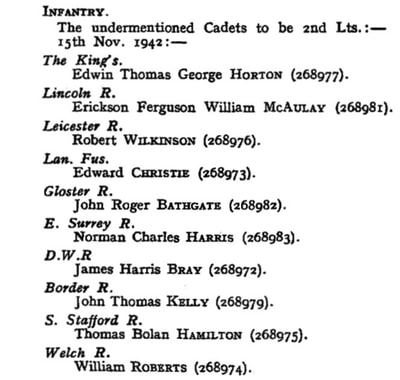

William Roberts, from Dowlais, a village in the county borough of Merthyr Tydfil, South Wales, was commissioned from Officer Cadet (Welsh Guards) to 2nd Lieutenant (Welch Regiment) on the 15th November 1942. Previously, William, known to his friends and comrades as Gerry, was a Transport Corporal in the Welsh Guards and presumably had been put forward by the Regiment as officer material whilst serving back in Britain.

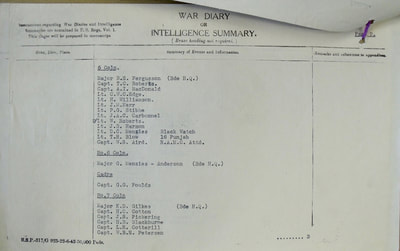

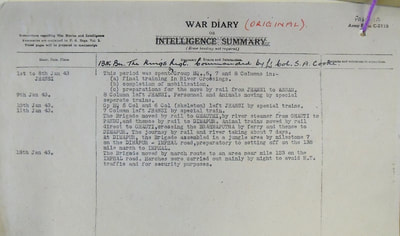

268974 2nd Lieutenant Roberts then travelled to India and on the 20th December 1942, he, along with ten other officer recruits, was transferred to the 13th King's training camp at Jhansi located in the state of Uttar Pradesh. Arriving so late in the day so to speak, Gerry and the other young officers had little time to assimilate into the Chindit training regime, or even acclimatise to sub-continental conditions. In his usual stoical and positive way, the newly promoted Lt. Roberts took all these challenges in his stride.

Gerry was posted to 5 Column, under the overall command of Major Bernard Fergusson, formerly of the Black Watch Regiment. In his book about the first Chindit expedition entitled Beyond the Chindwin, Fergusson remembered taking on board several new officers in the lead up to Christmas 1942:

My newcomers were Jim Harman, who had been with Mike Calvert’s Jungle Warfare School in Maymyo and had come out through China the year before; Willy Williamson, ex-regular from the King’s, who went in as longstop to Tommy Roberts’ Support Platoon; and Gerry Roberts, ex-transport Corporal in the Welsh Guards, and since then a professional footballer. He was officially a first reinforcement, but I attached him to Bill Smyly as assistant ATO (Animal Transport Officer). Eventually in Burma he led the third rifle platoon, No. 9.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this first short section of the story. Included amongst these images is the London Gazette announcement for Gerry's commission dated 7th May 1943. This page from the Gazette also lists other men who became 2nd Lieutenants on the same date and in the case of Lts. Robert Wilkinson, Edwin Horton and John Thomas Kelly, went on to serve on the first Wingate operation and became close friends with Gerry. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

268974 2nd Lieutenant Roberts then travelled to India and on the 20th December 1942, he, along with ten other officer recruits, was transferred to the 13th King's training camp at Jhansi located in the state of Uttar Pradesh. Arriving so late in the day so to speak, Gerry and the other young officers had little time to assimilate into the Chindit training regime, or even acclimatise to sub-continental conditions. In his usual stoical and positive way, the newly promoted Lt. Roberts took all these challenges in his stride.

Gerry was posted to 5 Column, under the overall command of Major Bernard Fergusson, formerly of the Black Watch Regiment. In his book about the first Chindit expedition entitled Beyond the Chindwin, Fergusson remembered taking on board several new officers in the lead up to Christmas 1942:

My newcomers were Jim Harman, who had been with Mike Calvert’s Jungle Warfare School in Maymyo and had come out through China the year before; Willy Williamson, ex-regular from the King’s, who went in as longstop to Tommy Roberts’ Support Platoon; and Gerry Roberts, ex-transport Corporal in the Welsh Guards, and since then a professional footballer. He was officially a first reinforcement, but I attached him to Bill Smyly as assistant ATO (Animal Transport Officer). Eventually in Burma he led the third rifle platoon, No. 9.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this first short section of the story. Included amongst these images is the London Gazette announcement for Gerry's commission dated 7th May 1943. This page from the Gazette also lists other men who became 2nd Lieutenants on the same date and in the case of Lts. Robert Wilkinson, Edwin Horton and John Thomas Kelly, went on to serve on the first Wingate operation and became close friends with Gerry. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

As already mentioned by Bernard Fergusson, Gerry's first role in 5 Column was to support Animal Transport Officer, Lt. Bill Smyly in the care of the units mules and horses. As an officer in the Chindit Brigade, Gerry was given his own horse to ride, which he named Patsy. He was heavily involved in the transportation of these animals to the operational starting point at Imphal in Assam during the first week of January 1943. This was partly achieved by train, starting from the column's base at Jhansi and ending at the rail station at Dimapur (see War diary entry in next gallery). The animals were transported aboard Cattle Wagons with two mule leaders allocated to each wagon. Fourteen days water and forage were carried for the animals, with the addition of heavy blankets for the latter part of the journey which would be at altitude in the mountains of Assam.

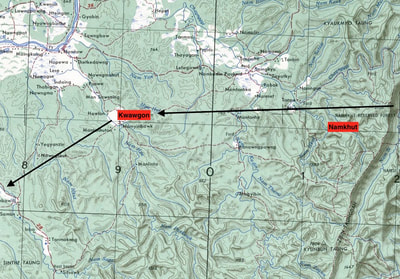

It was whilst working as column A.T.O. that Gerry first came into contact with Sgt. Ronald Rothwell of the King's Regiment. The two men would share the majority of the expedition together and secure a strong friendship during this time. One of the first real tests for Lt. Roberts on Operation Longcloth was getting his charges over the Chindwin River. On the 15th February 1943, 5 Column began their crossing close to the Burmese village of Hwematte and Lt. Roberts, with considerable assistance from Sgt. Rothwell, eventually made the east banks of the river, with all his animals intact the following day.

With the Chindwin behind them, the column began their journey along the Myene Valley, where night marches were miserable affairs through the cold and persistent rain. On the 22nd February they reached the village of Tonmakeng, the location chosen by Brigadier Wingate for the first planned supply drop. Gerry was given the role of Supply Drop Security Officer at Tonmakeng, which involved him securing the perimeter of the dropping zone against potential enemy interference. There is a photograph of him in the next gallery, watching over the supply drop whilst sitting astride his horse, Patsy.

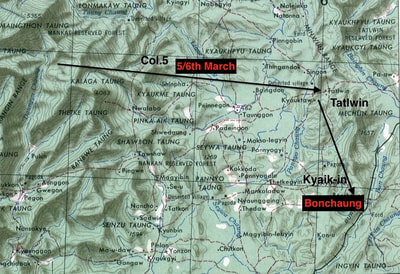

Not long afterwards on the 3rd March, Gerry was asked by Bernard Fergusson to take over the command of No. 9 Rifle Platoon, one of three such platoons in 5 Column on Operation Longcloth. He asked Major Fergusson if he might take Sgt. Rothwell as his second for No. 9 Platoon and this request was granted. From that moment on, the fate of the two soldiers would be intrinsically linked. Gerry Roberts' unit often worked ahead of the main body of the column, scouting out new tracks and trails, and testing the trustworthiness of the villages encountered along the way. They were heavily involved in 5 Column's first skirmish with the Japanese at the hamlet of Kyaik-in, close to where Fergusson's men were to deliver their demolition of the Myitkhina-Mandalay railway at Bonchaung.

Column 5 were given one specific task by Orde Wingate in 1943; this was to destroy the railway bridge at the Bonchaung Gorge. It was on their journey to Bonchaung in early March, that Lt. John Kerr and his platoon were caught up in a brief, but extremely fierce fire-fight with a Japanese patrol.

To help set the scene, here is how Bernard Fergusson remembered the incident in his book, Beyond the Chindwin:

On the morning of the 6th of March, everybody got off to time; but before I had marched four hundred yards along the road, Fitzpatrick, Tommy Roberts' groom, came up at a gallop, somewhat flustered. He had been up and down the road for fifteen minutes, unable to spot the point in the jungle where our bivouac had been. (I never bivouacked within five hundred yards of a track). Tommy was engaged in Kyaik-in village with some Japanese; he had sent Jim Harman back and round to go straight for the gorge, and was fighting it out himself. I asked Fitzpatrick (in civil life a buttons in a Liverpool hotel) for details, but all he knew was that there was a lot of shooting going on, and a lot of bangs, and Tommy had sent him back to warn me.

I hastily decided to send the main body straight off across country to Bonchaung. I sent the remaining rifle platoon, now commanded by Gerry Roberts, down the motor-road to the village as fast as it could go, to back up Tommy, while I gave Alec and Duncan their orders. When I had finished, I took Peter Dorans, and followed Gerry. As I drew near the village, I could hear light machine-guns in action, and the occasional burst of a grenade. The jungle was continuous on the right of the road, but there was a small strip of disused paddy, with some scrubby bushes, on the left; and by the time I arrived (for it took a minute or two to give out the orders to the main body) Gerry's leading Bren section was already in position, and had fired on a small party of Japs.

Obsessed with the importance of avoiding a fight with our own troops, I begged him to be careful, and to work gradually along the track. I saw two men of the original party in the bushes on the right, one of whom was Bill Edge's servant, who had been with Tommy: he told me that Bill Edge had been hit, had gone off with Bill Aird to get his wound dressed, and told him to stay by his pack. By this time all was quiet, except for one light machine-gun firing at us from the south-eastern end of the paddy; but its fire soon ceased, and somebody found the gunner dead by his gun half an hour later. I pushed gingerly forward with a section, and found a fork in the road; one branch, which seemed to be the main road, ran over the hill, and the other went into the village. In the point of the wood at the fork, I saw Private Fairhurst, who called to me that John Kerr was there and wounded.

I crossed the road, noticing as I did so two dead Japs, and found John with a painful wound in the calf of the leg, right in the muscle. Beside him were half a dozen Japanese dead and two or three other British dead or wounded: among them was poor Lancaster, the boy who had been one of my swimming instructors, unconscious and almost out. I offered John some morphia, but he refused it until he had told me his story, in case his brain got muddled, very typical of his devotion to duty. They had walked head-on into a lorry-load of Japs standing in the village: he thought they had just climbed into it after cross-examining the villagers.

They had killed several of them at once, but the driver had driven off immediately, with at least two bodies in the back, to the south. They thought they had killed everybody, for the loss of two killed and Bill Edge and one or two others wounded; and Tommy Roberts had gone on. John was waiting only to collect his platoon, when suddenly a new light machine-gun had opened up, and hit him and several more. While he was telling me this, there was a sudden report just beside my ear, and I spun round to find Peter Dorans with a smoking rifle, and one of the two "dead" Japs in the road writhing. He had suddenly flung himself up on his elbow and pointed his rifle at me. Peter shot him again and finally dispatched him.

With Gerry Roberts’ platoon, and with the much saddened platoon of John Kerr, I sought the track to Bonchaung, but could find no trace of it. To the south we heard explosions; we knew it could not be Jim Harman and rightly guessed that it was Mike Calvert celebrating his thirtieth birthday at Nankan. I became more and more anxious to hurry to Bonchaung, and so I told Gerry to come on with men and animals as fast as he could, while I pushed on ahead with Peter Dorans.

Seen below is another gallery of images to illustrate this narrative. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

It was whilst working as column A.T.O. that Gerry first came into contact with Sgt. Ronald Rothwell of the King's Regiment. The two men would share the majority of the expedition together and secure a strong friendship during this time. One of the first real tests for Lt. Roberts on Operation Longcloth was getting his charges over the Chindwin River. On the 15th February 1943, 5 Column began their crossing close to the Burmese village of Hwematte and Lt. Roberts, with considerable assistance from Sgt. Rothwell, eventually made the east banks of the river, with all his animals intact the following day.

With the Chindwin behind them, the column began their journey along the Myene Valley, where night marches were miserable affairs through the cold and persistent rain. On the 22nd February they reached the village of Tonmakeng, the location chosen by Brigadier Wingate for the first planned supply drop. Gerry was given the role of Supply Drop Security Officer at Tonmakeng, which involved him securing the perimeter of the dropping zone against potential enemy interference. There is a photograph of him in the next gallery, watching over the supply drop whilst sitting astride his horse, Patsy.

Not long afterwards on the 3rd March, Gerry was asked by Bernard Fergusson to take over the command of No. 9 Rifle Platoon, one of three such platoons in 5 Column on Operation Longcloth. He asked Major Fergusson if he might take Sgt. Rothwell as his second for No. 9 Platoon and this request was granted. From that moment on, the fate of the two soldiers would be intrinsically linked. Gerry Roberts' unit often worked ahead of the main body of the column, scouting out new tracks and trails, and testing the trustworthiness of the villages encountered along the way. They were heavily involved in 5 Column's first skirmish with the Japanese at the hamlet of Kyaik-in, close to where Fergusson's men were to deliver their demolition of the Myitkhina-Mandalay railway at Bonchaung.

Column 5 were given one specific task by Orde Wingate in 1943; this was to destroy the railway bridge at the Bonchaung Gorge. It was on their journey to Bonchaung in early March, that Lt. John Kerr and his platoon were caught up in a brief, but extremely fierce fire-fight with a Japanese patrol.

To help set the scene, here is how Bernard Fergusson remembered the incident in his book, Beyond the Chindwin:

On the morning of the 6th of March, everybody got off to time; but before I had marched four hundred yards along the road, Fitzpatrick, Tommy Roberts' groom, came up at a gallop, somewhat flustered. He had been up and down the road for fifteen minutes, unable to spot the point in the jungle where our bivouac had been. (I never bivouacked within five hundred yards of a track). Tommy was engaged in Kyaik-in village with some Japanese; he had sent Jim Harman back and round to go straight for the gorge, and was fighting it out himself. I asked Fitzpatrick (in civil life a buttons in a Liverpool hotel) for details, but all he knew was that there was a lot of shooting going on, and a lot of bangs, and Tommy had sent him back to warn me.

I hastily decided to send the main body straight off across country to Bonchaung. I sent the remaining rifle platoon, now commanded by Gerry Roberts, down the motor-road to the village as fast as it could go, to back up Tommy, while I gave Alec and Duncan their orders. When I had finished, I took Peter Dorans, and followed Gerry. As I drew near the village, I could hear light machine-guns in action, and the occasional burst of a grenade. The jungle was continuous on the right of the road, but there was a small strip of disused paddy, with some scrubby bushes, on the left; and by the time I arrived (for it took a minute or two to give out the orders to the main body) Gerry's leading Bren section was already in position, and had fired on a small party of Japs.

Obsessed with the importance of avoiding a fight with our own troops, I begged him to be careful, and to work gradually along the track. I saw two men of the original party in the bushes on the right, one of whom was Bill Edge's servant, who had been with Tommy: he told me that Bill Edge had been hit, had gone off with Bill Aird to get his wound dressed, and told him to stay by his pack. By this time all was quiet, except for one light machine-gun firing at us from the south-eastern end of the paddy; but its fire soon ceased, and somebody found the gunner dead by his gun half an hour later. I pushed gingerly forward with a section, and found a fork in the road; one branch, which seemed to be the main road, ran over the hill, and the other went into the village. In the point of the wood at the fork, I saw Private Fairhurst, who called to me that John Kerr was there and wounded.

I crossed the road, noticing as I did so two dead Japs, and found John with a painful wound in the calf of the leg, right in the muscle. Beside him were half a dozen Japanese dead and two or three other British dead or wounded: among them was poor Lancaster, the boy who had been one of my swimming instructors, unconscious and almost out. I offered John some morphia, but he refused it until he had told me his story, in case his brain got muddled, very typical of his devotion to duty. They had walked head-on into a lorry-load of Japs standing in the village: he thought they had just climbed into it after cross-examining the villagers.

They had killed several of them at once, but the driver had driven off immediately, with at least two bodies in the back, to the south. They thought they had killed everybody, for the loss of two killed and Bill Edge and one or two others wounded; and Tommy Roberts had gone on. John was waiting only to collect his platoon, when suddenly a new light machine-gun had opened up, and hit him and several more. While he was telling me this, there was a sudden report just beside my ear, and I spun round to find Peter Dorans with a smoking rifle, and one of the two "dead" Japs in the road writhing. He had suddenly flung himself up on his elbow and pointed his rifle at me. Peter shot him again and finally dispatched him.

With Gerry Roberts’ platoon, and with the much saddened platoon of John Kerr, I sought the track to Bonchaung, but could find no trace of it. To the south we heard explosions; we knew it could not be Jim Harman and rightly guessed that it was Mike Calvert celebrating his thirtieth birthday at Nankan. I became more and more anxious to hurry to Bonchaung, and so I told Gerry to come on with men and animals as fast as he could, while I pushed on ahead with Peter Dorans.

Seen below is another gallery of images to illustrate this narrative. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

After successfully completing the demolitions at Bonchaung Gorge, 5 Column continued their journey east towards the Irrawaddy River. Wingate had debated with his column commanders whether it was worthwhile, or indeed sensible to continue the expedition across the Irrawaddy on Operation Longcloth. In the end he decided it was, and the individual columns made their way across at varying places along the west bank.

5 Column crossed the mile-wide river at a place called Tigyaing, from where, after a most welcoming reception from the local villagers, which included stocking up with some much needed food supplies, the column made the trip over. By early evening the last boat, containing the Major and his bodyguard had just begun their journey across, when a Japanese patrol entered Tigyaing and optimistically fired upon Fergusson's craft, but thankfully with no effect.

Previously that day, Lt. Roberts had been ordered by Major Fergusson to destroy an old paddle-steamer which was moored slightly to the north of Tigyaing and was suspected as being used by the Japanese to transport troops and supplies across the Irrawaddy.

Gerry Roberts recalled the incident at Tigyaing in the pages of his own personnel diary:

10th March 1943: Am holding a position on a crest in the area of the temple at Tigyaing on the Irrawaddy. The people are so grateful to see us. Had the most wonderful meal of rice cooked by the villagers; sent a boy to buy bananas and Sgt. Rothwell to buy sugar. Sliced half dozen bananas on a plate of rice and covered it with sugar, a wonderful treat. Looking through my field glasses, I can’t see any movement on this side of the river. We shall cross as soon as possible.

The crossing was good on the whole, but I felt most uncomfortable in the little boat I was in. I am sent down stream with a part of my group to blow up a River Steamer. We had a hot reception on landing at the East Bank. Japs opened up with 4" inch mortars and machine guns from their position on the beach. Got over this ok and marched on about four miles to where Captain MacDonald had recce’d a bivouac area.

After waiting in this bivouac for 24 hours in the hope that the enemy would be thrown off their trail, 5 Column pushed on eastwards into the dry and waterless country beyond the Irrawaddy.

Seen below is a magnificent photograph of the village of Tigyaing taken from the east banks of the Irrawaddy River in 2013, by the daughter of Captain Tommy Roberts, 5 Column's Support Platoon commander on Operation Longcloth.

5 Column crossed the mile-wide river at a place called Tigyaing, from where, after a most welcoming reception from the local villagers, which included stocking up with some much needed food supplies, the column made the trip over. By early evening the last boat, containing the Major and his bodyguard had just begun their journey across, when a Japanese patrol entered Tigyaing and optimistically fired upon Fergusson's craft, but thankfully with no effect.

Previously that day, Lt. Roberts had been ordered by Major Fergusson to destroy an old paddle-steamer which was moored slightly to the north of Tigyaing and was suspected as being used by the Japanese to transport troops and supplies across the Irrawaddy.

Gerry Roberts recalled the incident at Tigyaing in the pages of his own personnel diary:

10th March 1943: Am holding a position on a crest in the area of the temple at Tigyaing on the Irrawaddy. The people are so grateful to see us. Had the most wonderful meal of rice cooked by the villagers; sent a boy to buy bananas and Sgt. Rothwell to buy sugar. Sliced half dozen bananas on a plate of rice and covered it with sugar, a wonderful treat. Looking through my field glasses, I can’t see any movement on this side of the river. We shall cross as soon as possible.

The crossing was good on the whole, but I felt most uncomfortable in the little boat I was in. I am sent down stream with a part of my group to blow up a River Steamer. We had a hot reception on landing at the East Bank. Japs opened up with 4" inch mortars and machine guns from their position on the beach. Got over this ok and marched on about four miles to where Captain MacDonald had recce’d a bivouac area.

After waiting in this bivouac for 24 hours in the hope that the enemy would be thrown off their trail, 5 Column pushed on eastwards into the dry and waterless country beyond the Irrawaddy.

Seen below is a magnificent photograph of the village of Tigyaing taken from the east banks of the Irrawaddy River in 2013, by the daughter of Captain Tommy Roberts, 5 Column's Support Platoon commander on Operation Longcloth.

Wingate's decision to take the majority of his Brigade over the Irrawaddy River proved with the benefit of hindsight to be a mistake. During the third week of March and with a return to India in mind, 5 Column were given orders to create a diversion for the rest of the Brigade, which now found itself trapped in a three-sided bag between the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers to the west and north and the Mongmit-Myitson motor road to the south. Wingate instructed Fergusson to "trail his coat" and lead the Japanese pursuers away from the general direction of the Irrawaddy and in particular the area around the town of Inywa, where Wingate now hoped to re-cross the river.

By March 28th, 5 Column had reached the village of Hintha which was situated in an area of thick and tight-set bamboo scrub. Any attempt to navigate around the settlement proved impossible, and so rather reluctantly Fergusson decided to enter the village by the main track and check for the presence of enemy patrols. He unluckily stumbled upon such a patrol and a fire-fight ensued. The battle at Hintha proved to be 5 Column's Waterloo and many men were killed or wounded during the engagement at the village. To read more about Hintha and the men who perished there, please click on the following link: Pte. John Henry Cobb

After a battle lasting several hours, Major Fergusson withdrew his men from Hintha and led them away towards a pre-arranged rendezvous point some two miles or so to the northeast. Here he met up with the rest of his unit, who under the command of Flight-Lieutenant Denny Sharp, the column's RAF Liaison officer, were waiting for their commander's return in a dried up river bed, known in Burma as a chaung. In the confusion at Hintha, many groups of soldiers had become separated from the main body of the column. On reaching the rendezvous point at the chaung, Fergusson was relieved to discover that most of these men had been accounted for:

When Peter Buchanan and I reached my bivouac, I was delighted to find Denny Sharp, Jim Harman and most of his commandos; Gerry Roberts and his platoon, Bill Edge, Pepper, Foster and White, then all arrived in. They had had a longer march than we, having failed to get down the chaung, and having been compelled to go back up it the way we had come in, the previous evening. Once on the hill, they got away across country; but while climbing up it, two of the most precious mules of the whole string had tumbled over the cliff into the chaung below: one carried the wireless, and the other the ciphers. Lance-Corporal Lee had gone back down to recover the ciphers, and had not been seen since.

Disastrously, as the reacquainted column marched away from the chaung it was once again attacked, this time by a large Japanese patrol which had been tracking Fergusson's men since their withdrawal from Hintha village. Over one hundred men were cut adrift from 5 Column at this juncture. In one witness statement provided by a survivor of Operation Longcloth, Sgt. Rothwell was rumoured to be amongst those lost at the second ambush. However, further mentions in both Bernard Fergusson's book, Beyond the Chindwin and the diary of Gerry Roberts, prove this rumour to be untrue.

Within two days, the remainder of 5 Column were marching parallel to the west banks of the treacherous and fast flowing Shweli River, looking for a suitable place to cross. On the 31st March, Fergusson sent out a patrol under the command of Gerry Roberts to locate the river and any likely crossing points. By this time the men were not only weak with hunger and exhausted, but also, very much on edge and exceedingly suspicious in their mindset. During his time out on patrol, Gerry Roberts came upon two Burmese villagers, who in his mind were acting in a rather doubtful manner. From the book, Beyond the Chindwin:

I (Major Fergusson) sent out a patrol under Gerry Roberts to find the river. Gerry was back at noon, with him were two frightened Burmese, whom he wanted to shoot. He had found the river by following the track, but on his way back he found these two lighting a fire on the path.

Fergusson chose not to shoot the two Burmese, whom Lt. Roberts suspected were trying to alert the Japanese of 5 Column's presence in the area by lighting a signal fire. After finding a crossing point near the village of Tokkin and two local fishermen to ferry them over, 5 Column, during the early hours of April 1st began to ford the river. Unfortunately, they were inexplicably landed upon a large sandbank in the middle of the river instead of the far bank and this left them another 80 yards of foaming and perilous water to navigate before they reached the eastern shores.

The Japanese were now hot on their heels, and treachery seemed all around the exhausted and desperate group. Whether the two Burmese arrested by Gerry the previous afternoon had been instrumental in the column's current predicament cannot be known for sure, but nevertheless, over forty Chindits never made it off the sandbank on April 1st, with most of these men being captured by the Japanese and perishing as prisoners of war inside Rangoon Jail over the following weeks and months.

To read more about the incident at the Shweli, please click on the following link: The Men of the Shweli Sandbank

Upset and saddened by their losses at the Shweli, Major Fergusson and the remnants of 5 Column trudged wearily away. Some nine days later the column, now numbering just ninety or so men, began their second approach to the Irrawaddy, this time close to the rivers second defile near Zinbon. It was here on the 10th April that Major Fergusson decided to break his unit up into three separate dispersal groups, led by himself, Flight Lieutenant Denny Sharp and Captain Tommy Roberts of the King's. Gerry Roberts and Sgt. Rothwell were allocated to Denny Sharp's party to bolster the RAF officer's command.

From the pages of Beyond the Chindwin:

We had broken down into three dispersal groups close to the Irrawaddy. Tommy Roberts had seen an old fishing boat on the back of the mere behind the fisherman's hut, and near it an old bullock-cart. He proposed to put the one on the other, and wheel it to the Irrawaddy. Denny Sharp, with Gerry Roberts as his second wanted to come with me as far as the river, and share my luck there if I had any. I proposed to march boldly to the river in daylight, straight away, to see if there were any sign of boats.

Tommy hated hanging about as much as I did, and with the prospect of doing something he became positively jubilant. He got hold of his party, harangued them briskly, and then all together we marched back to the fisherman's hut. There I shook hands with Tommy, and wished him luck. He was full of confidence and very cheerful; before I had gone a hundred yards I looked back and saw him organising a party to haul the boat out of the water, and sending some more men to fetch the bullock-cart. That was the last time I ever saw him.

Once over the inky black river and with the coming of daylight the jungle looked less formidable, we found almost immediately a long and narrow patch of disused paddy, leading past the thick outer defences of the forest. Two incidents during the first fifteen minutes' marching cheered us up (and we were cheerful enough already, with the Irrawaddy behind us). First, out of the undergrowth darted Judy our messenger dog, she looked at us quizzically and vanished back into the trees before we could put a note in the little satchel which she still wore round her neck. She had by now become firmly attached to Gerry Roberts, so we knew that Denny Sharp was across complete, and on the move in the same general direction as ourselves.

NB. To read more about the fate of Tommy Roberts and his men, please click on the following link: Tommy Roberts Platoon

By March 28th, 5 Column had reached the village of Hintha which was situated in an area of thick and tight-set bamboo scrub. Any attempt to navigate around the settlement proved impossible, and so rather reluctantly Fergusson decided to enter the village by the main track and check for the presence of enemy patrols. He unluckily stumbled upon such a patrol and a fire-fight ensued. The battle at Hintha proved to be 5 Column's Waterloo and many men were killed or wounded during the engagement at the village. To read more about Hintha and the men who perished there, please click on the following link: Pte. John Henry Cobb

After a battle lasting several hours, Major Fergusson withdrew his men from Hintha and led them away towards a pre-arranged rendezvous point some two miles or so to the northeast. Here he met up with the rest of his unit, who under the command of Flight-Lieutenant Denny Sharp, the column's RAF Liaison officer, were waiting for their commander's return in a dried up river bed, known in Burma as a chaung. In the confusion at Hintha, many groups of soldiers had become separated from the main body of the column. On reaching the rendezvous point at the chaung, Fergusson was relieved to discover that most of these men had been accounted for:

When Peter Buchanan and I reached my bivouac, I was delighted to find Denny Sharp, Jim Harman and most of his commandos; Gerry Roberts and his platoon, Bill Edge, Pepper, Foster and White, then all arrived in. They had had a longer march than we, having failed to get down the chaung, and having been compelled to go back up it the way we had come in, the previous evening. Once on the hill, they got away across country; but while climbing up it, two of the most precious mules of the whole string had tumbled over the cliff into the chaung below: one carried the wireless, and the other the ciphers. Lance-Corporal Lee had gone back down to recover the ciphers, and had not been seen since.

Disastrously, as the reacquainted column marched away from the chaung it was once again attacked, this time by a large Japanese patrol which had been tracking Fergusson's men since their withdrawal from Hintha village. Over one hundred men were cut adrift from 5 Column at this juncture. In one witness statement provided by a survivor of Operation Longcloth, Sgt. Rothwell was rumoured to be amongst those lost at the second ambush. However, further mentions in both Bernard Fergusson's book, Beyond the Chindwin and the diary of Gerry Roberts, prove this rumour to be untrue.

Within two days, the remainder of 5 Column were marching parallel to the west banks of the treacherous and fast flowing Shweli River, looking for a suitable place to cross. On the 31st March, Fergusson sent out a patrol under the command of Gerry Roberts to locate the river and any likely crossing points. By this time the men were not only weak with hunger and exhausted, but also, very much on edge and exceedingly suspicious in their mindset. During his time out on patrol, Gerry Roberts came upon two Burmese villagers, who in his mind were acting in a rather doubtful manner. From the book, Beyond the Chindwin:

I (Major Fergusson) sent out a patrol under Gerry Roberts to find the river. Gerry was back at noon, with him were two frightened Burmese, whom he wanted to shoot. He had found the river by following the track, but on his way back he found these two lighting a fire on the path.

Fergusson chose not to shoot the two Burmese, whom Lt. Roberts suspected were trying to alert the Japanese of 5 Column's presence in the area by lighting a signal fire. After finding a crossing point near the village of Tokkin and two local fishermen to ferry them over, 5 Column, during the early hours of April 1st began to ford the river. Unfortunately, they were inexplicably landed upon a large sandbank in the middle of the river instead of the far bank and this left them another 80 yards of foaming and perilous water to navigate before they reached the eastern shores.

The Japanese were now hot on their heels, and treachery seemed all around the exhausted and desperate group. Whether the two Burmese arrested by Gerry the previous afternoon had been instrumental in the column's current predicament cannot be known for sure, but nevertheless, over forty Chindits never made it off the sandbank on April 1st, with most of these men being captured by the Japanese and perishing as prisoners of war inside Rangoon Jail over the following weeks and months.

To read more about the incident at the Shweli, please click on the following link: The Men of the Shweli Sandbank

Upset and saddened by their losses at the Shweli, Major Fergusson and the remnants of 5 Column trudged wearily away. Some nine days later the column, now numbering just ninety or so men, began their second approach to the Irrawaddy, this time close to the rivers second defile near Zinbon. It was here on the 10th April that Major Fergusson decided to break his unit up into three separate dispersal groups, led by himself, Flight Lieutenant Denny Sharp and Captain Tommy Roberts of the King's. Gerry Roberts and Sgt. Rothwell were allocated to Denny Sharp's party to bolster the RAF officer's command.

From the pages of Beyond the Chindwin:

We had broken down into three dispersal groups close to the Irrawaddy. Tommy Roberts had seen an old fishing boat on the back of the mere behind the fisherman's hut, and near it an old bullock-cart. He proposed to put the one on the other, and wheel it to the Irrawaddy. Denny Sharp, with Gerry Roberts as his second wanted to come with me as far as the river, and share my luck there if I had any. I proposed to march boldly to the river in daylight, straight away, to see if there were any sign of boats.

Tommy hated hanging about as much as I did, and with the prospect of doing something he became positively jubilant. He got hold of his party, harangued them briskly, and then all together we marched back to the fisherman's hut. There I shook hands with Tommy, and wished him luck. He was full of confidence and very cheerful; before I had gone a hundred yards I looked back and saw him organising a party to haul the boat out of the water, and sending some more men to fetch the bullock-cart. That was the last time I ever saw him.

Once over the inky black river and with the coming of daylight the jungle looked less formidable, we found almost immediately a long and narrow patch of disused paddy, leading past the thick outer defences of the forest. Two incidents during the first fifteen minutes' marching cheered us up (and we were cheerful enough already, with the Irrawaddy behind us). First, out of the undergrowth darted Judy our messenger dog, she looked at us quizzically and vanished back into the trees before we could put a note in the little satchel which she still wore round her neck. She had by now become firmly attached to Gerry Roberts, so we knew that Denny Sharp was across complete, and on the move in the same general direction as ourselves.

NB. To read more about the fate of Tommy Roberts and his men, please click on the following link: Tommy Roberts Platoon

Flight-Lieutenant Denis Sharp DFC.

Flight-Lieutenant Denis Sharp DFC.

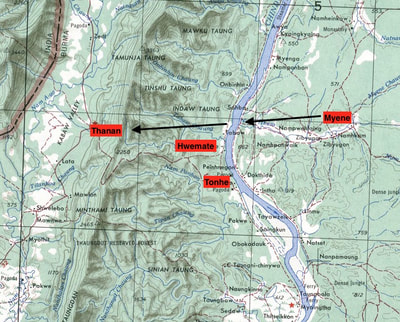

On the 10th April 1943, Denny Sharp, Gerry Roberts and Sgt. Rothwell, along with the rest of their party succeeded in getting over the river. It would take these Chindits another two weeks to make the journey back to India, often going without food or water for days on end and having to risk entering unfriendly villages in the hope of supplementing their meagre rations.

On the 17th April, Major Fergusson and Denny Sharp's parties met up by chance at the village of Pakaw. Fergusson remembered:

We had a great reunion with them and all ranks mingled to swap adventures. They had a clean run across the railway, although like us they had nearly run into a Japanese patrol about two stations down the line from Kadu. Otherwise, they had no scares and Denny, splendid fellow that he was, had the whole business under control. I talked to his men and found them cheerful enough. Serjeant Rothwell was in the middle of a bad go of malaria, but characteristically made light of it. There was a general wish to merge both parties at this point, but both from the point of view of foraging and from confusing the issue of any troops trying to intercept us, I preferred to remain separate.

Denny Sharp's dispersal party re-crossed the Chindwin on the 24th April after bumping into a patrol of Seaforth Highlanders on the east bank. The Scots took them under their wing, feeding them bully beef and handing out cigarettes, before sending them on to Thanan for a wash, shave and much needed change of clothing. Most returning Chindits spent at least a few days at the 19th Casualty Clearing Station near Imphal, where Matron Agnes McGearey took care of their pains and ailments. After a period of rest and recuperation all men were sent back to their various regiments, with Gerry Roberts and Sgt. Rothwell rejoining the 13th King's, who were now stationed at the Napier Barracks in Karachi.

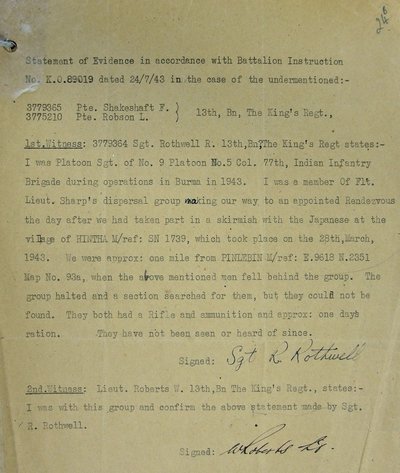

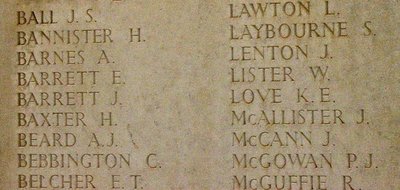

After Operation Longcloth had officially closed on 10th July 1943, many officers and men gave witness statements in relation to those soldiers who had been lost or killed in Burma. Gerry Roberts was asked in particular about a soldier named Harold Baxter, who had been a Rifleman in Lt. Philip Stibbe's No. 7 Platoon from within 5 Column. He also gave evidence in conjunction with Sgt. Rothwell about two other men from 5 Column: 3779365 Pte. F. Shakeshaft and 3775210 Pte. L. Robson.

On the 24th July 1943, they gave the following statements to the Army Investigation Bureau:

Statement of evidence in accordance with Battalion instruction, in the case of the undermentioned:

3779365 Pte. F. Shakeshaft

3775210 Pte. L. Robson

1st Witness: 3779364 Sgt. R. Rothwell, 13th King's Regiment states:

I was Platoon Sgt. of No. 9 Platoon, 5 Column, 77th Indian Infantry Brigade during operations in Burma in 1943. I was a member of Flight Lieutenant Sharp's dispersal group, making our way to an appointed rendezvous the day after we had taken part in a skirmish with the Japanese at the village of Hintha, (map ref. SN 1739), which took place on the 28th March 1943. We were approximately one mile from Pinlebin (map ref. E 9618 N 2351), when the above mentioned men fell behind the group. The group halted and a section searched for them, but they could not be found. They both had rifles and ammunition and one days rations. They have not been seen or heard of since.

2nd Witness: Lt. W. Roberts, 13th King's Regiment states:

I was with this group and confirm the above statement made by Sgt. R.A. Rothwell.

For the record, this is what actually happened to the above mentioned Kingsmen:

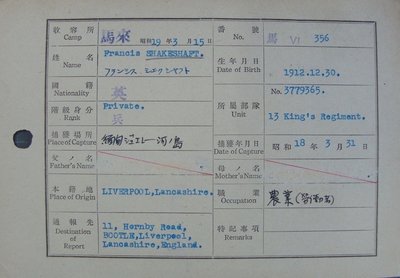

3779365 Pte. Francis Shakeshaft from Bootle in Liverpool, was captured on the 31st March 1943. He was given the POW number 356 and survived just over two years as a prisoner of war in Rangoon Jail, before being liberated in April 1945 near the Burmese town of Pegu.

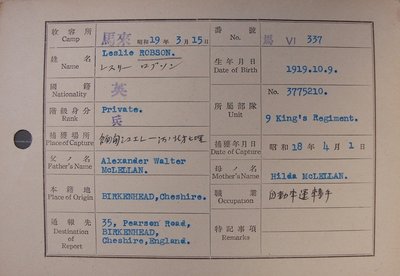

3775210 Pte. Leslie Robson, formerly with the 9th Battalion of the King's Regiment and from Birkenhead in Cheshire, was captured by the Japanese on the 1st April 1943. He was given the POW number 337 and much like Francis Shakeshaft was liberated by Allied forces in late April 1945 at Pegu.

5120086 Pte. Harold Baxter formerly of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, was transferred to the 13th King's on the 26th September 1942 and took up his place in No. 7 Platoon of 5 Column which was commanded by Lt. Philip Stibbe. He had caused consternation, and some amusement, when he lost his Bren gun and the mule carrying it, down a large water well at the village of Saugor during training. After the second ambush at Hintha, Pte. Baxter joined up with 7 Column at the Shweli River and was allocated to the dispersal party led by Lt. Musgrave -Wood. Official records state that Harold died on the 29th April 1943, although the following witness statement from Ptes. Baddiley and Carless of the King's Regiment suggest it was slightly later:

“Pte. H. Baxter died early in May. He was suffering from beri beri and would no longer eat. He was buried in our presence at the village of Sima, which lies to the south of Fort Morton."

Pte. Baxter's body was never recovered after the war and for this reason he is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery.

During the same month (July 1943), Gerry took the trouble to write to the father of another casualty from Operation Longcloth. The soldier in question was Pte. Henry James Ackerman from Gendros, a suburb of Swansea in South Wales. Henry, formerly of the Royal Welch Fusiliers had served with the Animal Transport section of 5 Column, where he took charge of one of the unit's bullocks. These cumbersome creatures were to be used in the first instance as transport pack animals, but were eventually eaten by the men when other rations began to run out.

Dear Mr. Ackerman,

It is with the deepest regret that I write to inform you that your son is missing. It is quite possible that he may be a prisoner of war, but I have no evidence that this is the case. If I receive any news of your son I will let you know at once.

I know your son very well, being one from the old country myself. I took a great interest in him and was privileged to have him under my command during the recent operations. The last line of the letter is difficult to make out, but says something like, 'I found him at all times to be in the best of spirits.'

Signed

Lieutenant W. Roberts, 13th King's Liverpool.

Gerry Roberts had been correct in predicting that Pte. Ackerman had fallen into Japanese hands during Operation Longcloth. Sadly, Henry Ackerman perished as a prisoner of war inside Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on the 2nd August 1943. To read more about his story, please click on the following link: Pte. Henry James Ackerman

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the men mentioned above and includes the original witness statement as given by Sgt. Rothwell and Gerry Roberts on the 24th July 1943. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

On the 17th April, Major Fergusson and Denny Sharp's parties met up by chance at the village of Pakaw. Fergusson remembered:

We had a great reunion with them and all ranks mingled to swap adventures. They had a clean run across the railway, although like us they had nearly run into a Japanese patrol about two stations down the line from Kadu. Otherwise, they had no scares and Denny, splendid fellow that he was, had the whole business under control. I talked to his men and found them cheerful enough. Serjeant Rothwell was in the middle of a bad go of malaria, but characteristically made light of it. There was a general wish to merge both parties at this point, but both from the point of view of foraging and from confusing the issue of any troops trying to intercept us, I preferred to remain separate.

Denny Sharp's dispersal party re-crossed the Chindwin on the 24th April after bumping into a patrol of Seaforth Highlanders on the east bank. The Scots took them under their wing, feeding them bully beef and handing out cigarettes, before sending them on to Thanan for a wash, shave and much needed change of clothing. Most returning Chindits spent at least a few days at the 19th Casualty Clearing Station near Imphal, where Matron Agnes McGearey took care of their pains and ailments. After a period of rest and recuperation all men were sent back to their various regiments, with Gerry Roberts and Sgt. Rothwell rejoining the 13th King's, who were now stationed at the Napier Barracks in Karachi.

After Operation Longcloth had officially closed on 10th July 1943, many officers and men gave witness statements in relation to those soldiers who had been lost or killed in Burma. Gerry Roberts was asked in particular about a soldier named Harold Baxter, who had been a Rifleman in Lt. Philip Stibbe's No. 7 Platoon from within 5 Column. He also gave evidence in conjunction with Sgt. Rothwell about two other men from 5 Column: 3779365 Pte. F. Shakeshaft and 3775210 Pte. L. Robson.

On the 24th July 1943, they gave the following statements to the Army Investigation Bureau:

Statement of evidence in accordance with Battalion instruction, in the case of the undermentioned:

3779365 Pte. F. Shakeshaft

3775210 Pte. L. Robson

1st Witness: 3779364 Sgt. R. Rothwell, 13th King's Regiment states:

I was Platoon Sgt. of No. 9 Platoon, 5 Column, 77th Indian Infantry Brigade during operations in Burma in 1943. I was a member of Flight Lieutenant Sharp's dispersal group, making our way to an appointed rendezvous the day after we had taken part in a skirmish with the Japanese at the village of Hintha, (map ref. SN 1739), which took place on the 28th March 1943. We were approximately one mile from Pinlebin (map ref. E 9618 N 2351), when the above mentioned men fell behind the group. The group halted and a section searched for them, but they could not be found. They both had rifles and ammunition and one days rations. They have not been seen or heard of since.

2nd Witness: Lt. W. Roberts, 13th King's Regiment states:

I was with this group and confirm the above statement made by Sgt. R.A. Rothwell.

For the record, this is what actually happened to the above mentioned Kingsmen:

3779365 Pte. Francis Shakeshaft from Bootle in Liverpool, was captured on the 31st March 1943. He was given the POW number 356 and survived just over two years as a prisoner of war in Rangoon Jail, before being liberated in April 1945 near the Burmese town of Pegu.

3775210 Pte. Leslie Robson, formerly with the 9th Battalion of the King's Regiment and from Birkenhead in Cheshire, was captured by the Japanese on the 1st April 1943. He was given the POW number 337 and much like Francis Shakeshaft was liberated by Allied forces in late April 1945 at Pegu.

5120086 Pte. Harold Baxter formerly of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, was transferred to the 13th King's on the 26th September 1942 and took up his place in No. 7 Platoon of 5 Column which was commanded by Lt. Philip Stibbe. He had caused consternation, and some amusement, when he lost his Bren gun and the mule carrying it, down a large water well at the village of Saugor during training. After the second ambush at Hintha, Pte. Baxter joined up with 7 Column at the Shweli River and was allocated to the dispersal party led by Lt. Musgrave -Wood. Official records state that Harold died on the 29th April 1943, although the following witness statement from Ptes. Baddiley and Carless of the King's Regiment suggest it was slightly later:

“Pte. H. Baxter died early in May. He was suffering from beri beri and would no longer eat. He was buried in our presence at the village of Sima, which lies to the south of Fort Morton."

Pte. Baxter's body was never recovered after the war and for this reason he is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery.

During the same month (July 1943), Gerry took the trouble to write to the father of another casualty from Operation Longcloth. The soldier in question was Pte. Henry James Ackerman from Gendros, a suburb of Swansea in South Wales. Henry, formerly of the Royal Welch Fusiliers had served with the Animal Transport section of 5 Column, where he took charge of one of the unit's bullocks. These cumbersome creatures were to be used in the first instance as transport pack animals, but were eventually eaten by the men when other rations began to run out.

Dear Mr. Ackerman,

It is with the deepest regret that I write to inform you that your son is missing. It is quite possible that he may be a prisoner of war, but I have no evidence that this is the case. If I receive any news of your son I will let you know at once.

I know your son very well, being one from the old country myself. I took a great interest in him and was privileged to have him under my command during the recent operations. The last line of the letter is difficult to make out, but says something like, 'I found him at all times to be in the best of spirits.'

Signed

Lieutenant W. Roberts, 13th King's Liverpool.

Gerry Roberts had been correct in predicting that Pte. Ackerman had fallen into Japanese hands during Operation Longcloth. Sadly, Henry Ackerman perished as a prisoner of war inside Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on the 2nd August 1943. To read more about his story, please click on the following link: Pte. Henry James Ackerman

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the men mentioned above and includes the original witness statement as given by Sgt. Rothwell and Gerry Roberts on the 24th July 1943. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

In March this year (2017) I received an email contact from Chris Prichard, who was able to help me with some more personal details about Gerry Roberts. Over the intervening period we have worked together in building up a fuller picture of his war-time service, based mostly upon the information written down in Lt. Roberts' own handwritten diary. It has been a privilege to read this diary which was recorded in Gerry's own Army 152 Correspondence Field Service Book. Browsing through the pages of his diary, really brought out Gerry's personality and character, especially his great sense of humour, his stoical, but positive nature and obvious pride in his Welsh heritage.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Chris Prichard and Mr. Teg Phillips (Lt. Roberts nephew) for their invaluable contribution in bringing this story to these website pages. From email conversations with Chris, it is believed that Gerry Roberts passed away in 2006 or 2007.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Chris Prichard and Mr. Teg Phillips (Lt. Roberts nephew) for their invaluable contribution in bringing this story to these website pages. From email conversations with Chris, it is believed that Gerry Roberts passed away in 2006 or 2007.

Gerry Roberts And His Return Journey to India

From the pages to Lt. Gerry Roberts' own handwritten diary, there now follows a transcription of the entries for the days directly after 5 Column split into three separate dispersal groups at the Irrawaddy River on the 9/10th April 1943.

9th April 1943

A patrol led by Captain Fraser goes back to the village to try and get further guides, returns three hours later having made no headway. The Column Commander calls an officers conference, where he decides to split up into three parties and try (to disperse) this way, this being easier for concealed movement.

We set off, Flight Lieutenant Sharp and myself with twenty-three men in my party, the Major (Fergusson) with another and Captain Roberts with the third group. Captain Roberts decides to strike out on his own. I decide to go to the river with the Major, this is my life saver. On approaching the river we contact some villagers, this is luck, no not luck, God has provided for us by leading us to honest villagers. We met these people about 2.30pm and Captain Fraser spoke to them in Burmese, they agree to provide boats and row us across after dark, meantime we conceal ourselves about 200 yards off the bank.

I collect 150 rupees from my group, another 150 is collected from the Major’s group, this we shall pay these grand people when the last man is across on the west bank. Waiting for zero hour is nerve racking. At last it comes and we move to the water’s edge. There are two boats, each one holding six men. The river is very wide and trip takes three quarters of an hour. The crossing is completed by 11.30pm. The men are excited, so am I, to think death stared us in the face a few hours ago, it isn’t over by any means, but the biggest obstacle has been negotiated. We gladly pay the natives the 300 rupees, it was well worth it! Leaving the beach we strike very thick jungle and can’t move through in the dark, so we cook a meal and have a couple of hours sleep.

10th April 1943

Morning finds us a very weary bunch, having slept on wet ground without anything to keep us warm except for the fact that we are now on the west bank of the Irrawaddy and are very grateful to have left behind one more death trap. Hundreds of our people are still somewhere on the other side and many miles away. Speeding on now, on the long journey to Assam and twelve miles in such a state of weakness, was a good feat for the day.

11th April 1943

We are in more friendly country now and food is not so scarce. Had bananas, rice and a little chicken stew today. Things are certainly brighter now and the possibility of getting out alive is very good. I got some guides to lead us through their country area and have gone a fairish distance, covering fourteen and a half miles approximately including a climb of 1000 feet.

12th April 1943

Next problem we have to encounter is the crossing of the Burma Railway and this is strongly held at every point. We arrive at a Ku-chin (Kachin) village, these are 100% British. We buy food from them and pay them well. Had two meals of chicken and rice which were excellent. We advance towards the railway, led from village to village by guides. The railway is negotiated without incident and we marched on until dawn. Marched twenty-three miles since morning including a great deal of climbing. The guides worked perfectly; don’t know what we should have done without them.

13th April 1943

Arrived at a little stream up in the mountains and have rested here until 4.30pm, having marched all last night. We move off and march six miles before dark, then have a good sleep, as tomorrow is going to be tough day of climbing.

14th April 1943

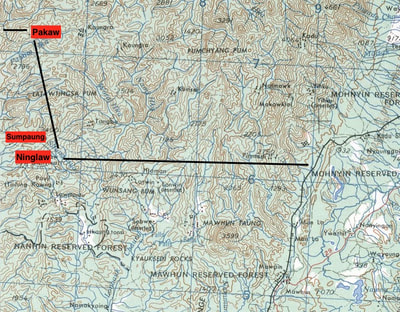

Moved off at 6am, purchase a little food from a village and halted at 8am to the cook the same. Arrived at Ninglaw and had a roaring welcome from the villagers. We camp on the outskirts of the village, people flock in to our area with all kinds of food and drink, the men are delighted and so am I. These are Ku-chins again, what grand folk they are, undoubtedly we owe our lives to these people, because without their help we could not have carried on.

15th April 1943

We move on again our next call being Sumpaung, had a little necklace from a native woman as a keepsake. Arrived at Namkadet at 4pm. I go into the village to buy more food. Stayed the night as everyone is dog tired after the long mountain climb. Foremost in my mind today is the memory of a rehearsal at Bethania (Chapel) in Dowlais, where I first heard the tune YR HWN A DDEL. This has haunted me all day.

Seen below is a photograph of the RAF wireless mules used by 5 Column on Operation Longcloth. These animals did not make it back to India in 1943 and were in fact let loose a short while before the column reached the Irrawaddy on the return journey.

From the pages to Lt. Gerry Roberts' own handwritten diary, there now follows a transcription of the entries for the days directly after 5 Column split into three separate dispersal groups at the Irrawaddy River on the 9/10th April 1943.

9th April 1943

A patrol led by Captain Fraser goes back to the village to try and get further guides, returns three hours later having made no headway. The Column Commander calls an officers conference, where he decides to split up into three parties and try (to disperse) this way, this being easier for concealed movement.

We set off, Flight Lieutenant Sharp and myself with twenty-three men in my party, the Major (Fergusson) with another and Captain Roberts with the third group. Captain Roberts decides to strike out on his own. I decide to go to the river with the Major, this is my life saver. On approaching the river we contact some villagers, this is luck, no not luck, God has provided for us by leading us to honest villagers. We met these people about 2.30pm and Captain Fraser spoke to them in Burmese, they agree to provide boats and row us across after dark, meantime we conceal ourselves about 200 yards off the bank.

I collect 150 rupees from my group, another 150 is collected from the Major’s group, this we shall pay these grand people when the last man is across on the west bank. Waiting for zero hour is nerve racking. At last it comes and we move to the water’s edge. There are two boats, each one holding six men. The river is very wide and trip takes three quarters of an hour. The crossing is completed by 11.30pm. The men are excited, so am I, to think death stared us in the face a few hours ago, it isn’t over by any means, but the biggest obstacle has been negotiated. We gladly pay the natives the 300 rupees, it was well worth it! Leaving the beach we strike very thick jungle and can’t move through in the dark, so we cook a meal and have a couple of hours sleep.

10th April 1943

Morning finds us a very weary bunch, having slept on wet ground without anything to keep us warm except for the fact that we are now on the west bank of the Irrawaddy and are very grateful to have left behind one more death trap. Hundreds of our people are still somewhere on the other side and many miles away. Speeding on now, on the long journey to Assam and twelve miles in such a state of weakness, was a good feat for the day.

11th April 1943

We are in more friendly country now and food is not so scarce. Had bananas, rice and a little chicken stew today. Things are certainly brighter now and the possibility of getting out alive is very good. I got some guides to lead us through their country area and have gone a fairish distance, covering fourteen and a half miles approximately including a climb of 1000 feet.

12th April 1943

Next problem we have to encounter is the crossing of the Burma Railway and this is strongly held at every point. We arrive at a Ku-chin (Kachin) village, these are 100% British. We buy food from them and pay them well. Had two meals of chicken and rice which were excellent. We advance towards the railway, led from village to village by guides. The railway is negotiated without incident and we marched on until dawn. Marched twenty-three miles since morning including a great deal of climbing. The guides worked perfectly; don’t know what we should have done without them.

13th April 1943

Arrived at a little stream up in the mountains and have rested here until 4.30pm, having marched all last night. We move off and march six miles before dark, then have a good sleep, as tomorrow is going to be tough day of climbing.

14th April 1943

Moved off at 6am, purchase a little food from a village and halted at 8am to the cook the same. Arrived at Ninglaw and had a roaring welcome from the villagers. We camp on the outskirts of the village, people flock in to our area with all kinds of food and drink, the men are delighted and so am I. These are Ku-chins again, what grand folk they are, undoubtedly we owe our lives to these people, because without their help we could not have carried on.

15th April 1943

We move on again our next call being Sumpaung, had a little necklace from a native woman as a keepsake. Arrived at Namkadet at 4pm. I go into the village to buy more food. Stayed the night as everyone is dog tired after the long mountain climb. Foremost in my mind today is the memory of a rehearsal at Bethania (Chapel) in Dowlais, where I first heard the tune YR HWN A DDEL. This has haunted me all day.

Seen below is a photograph of the RAF wireless mules used by 5 Column on Operation Longcloth. These animals did not make it back to India in 1943 and were in fact let loose a short while before the column reached the Irrawaddy on the return journey.

16th April 1943

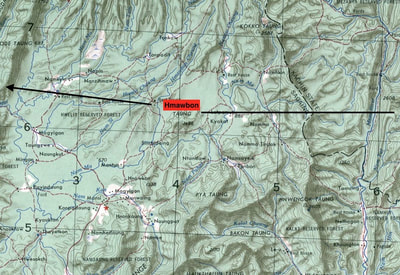

Met the Column Commander and his party in a village (Pakaw), where a meal of pork was being prepared for them by the villagers. I am not so fortunate, as Captain Fraser in his (Fergusson) group speaks Burmese fluently, where I am stuck with just a few phrases. I push on and arrange to link up with the column Commander later in the day. One of my men drops out completely exhausted, so I halt for ten minutes on a track two miles east of Hmawbon. During this halt we were attacked by an enemy patrol, caught napping whilst studying my map. Whew! What a near miss, don’t quite know how I got out of it? Lost two men killed and we killed the Jap Patrol leader.

NB. The soldier that dropped out was, Pte. 3779444 Thomas Alfred James who was killed near the village of Hmawbon.

17th April 1943

Sitting now on top of the world overlooking miles of country we have come through. Climbed up here on all fours, sheer slope at times and making footholds with a bayonet, should we have missed, there was a drop of 2500 feet below waiting to claim the unlucky. The climb was terrific and was only made with the will to get out in our minds. We have shaken off the Jap patrol by coming this way, they are probably waiting for us below, not thinking we would try this climb, but they are outwitted once more.

18th April 1943

Today again has been a terrific ordeal in the mountains, climbing on hands and knees up precipitous slopes of 2000 feet and then down again, then up once more on the other side. Where our strength comes from I don’t know as all we eat is boiled rice and that in very small quantities. We are now about six days march from the Chindwin River. Very short of rice and resting for the night in the Namkut Chaung.

19th April 1943

Had great luck in getting food, first at Namkhat, here we met natives who brought us rice and a few eggs. Didn’t have a scrap in my pack, but God looked down on us and saw our sad plight. Later at Kwangon where I am now, we had some little chicks and an abundance of rice, salt and tobacco etc. I am writing this by moonlight, while my chicken soup is being prepared by my servant. How very lucky we have been. Marched twenty miles today.

20th April 1943

Things are looking up, things are getting better and better every day, as we are getting nearer the Chindwin and safety. I am blessed with an attack of dysentery and am almost too weak to walk, but I am pushing on, not giving up now. Am not eating rice as this is the cause of my illness. Am foraging food very well, having had as much as I would for us all during the last two days. Now three days march from the Chindwin, we covered fifteen miles today.

21st April 1943

Foraging food at Naungbamu today had bananas, eggs, chickens, vegetables and native tobacco. Am very fortunate to have had so many letters dropped, as they have been so very useful and made a good substitute for cigarette papers. I had eight eggs yesterday and I needed them very badly. Am getting much better now, still weak (but aren’t we all) but going well. Covered sixteen miles today.

22nd April 1943

We have talked so much and longed for so long this Chindwin River. Now we are about twelve miles away from it, but can’t make it tonight, decided to stay the night here at Mene (Myene). No hope of sleep, thousands of mosquitos and ants, so here’s to the cooking pot. Marched fifteen miles today.

NB. It is quite remarkable that the group were able to march such distances at this point in time, when you consider their state of health, acute malnutrition and obvious exhaustion. You may also have noticed that Gerry records the miles made each day over the last period of the journey. This shows the mental countdown taking place in the men’s minds as they near their ultimate goal of the Chindwin River.

Seen below is a gallery of maps, tracing the dispersal party's journey from the moment they crossed the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway on the 12th April, until their re-crossing of the Chindwin River on the 24th April. The maps include the names of the various villages mentioned by Lt. Roberts in his diary. Please click on any map to bring it forward on the page.

Met the Column Commander and his party in a village (Pakaw), where a meal of pork was being prepared for them by the villagers. I am not so fortunate, as Captain Fraser in his (Fergusson) group speaks Burmese fluently, where I am stuck with just a few phrases. I push on and arrange to link up with the column Commander later in the day. One of my men drops out completely exhausted, so I halt for ten minutes on a track two miles east of Hmawbon. During this halt we were attacked by an enemy patrol, caught napping whilst studying my map. Whew! What a near miss, don’t quite know how I got out of it? Lost two men killed and we killed the Jap Patrol leader.

NB. The soldier that dropped out was, Pte. 3779444 Thomas Alfred James who was killed near the village of Hmawbon.

17th April 1943

Sitting now on top of the world overlooking miles of country we have come through. Climbed up here on all fours, sheer slope at times and making footholds with a bayonet, should we have missed, there was a drop of 2500 feet below waiting to claim the unlucky. The climb was terrific and was only made with the will to get out in our minds. We have shaken off the Jap patrol by coming this way, they are probably waiting for us below, not thinking we would try this climb, but they are outwitted once more.

18th April 1943

Today again has been a terrific ordeal in the mountains, climbing on hands and knees up precipitous slopes of 2000 feet and then down again, then up once more on the other side. Where our strength comes from I don’t know as all we eat is boiled rice and that in very small quantities. We are now about six days march from the Chindwin River. Very short of rice and resting for the night in the Namkut Chaung.

19th April 1943

Had great luck in getting food, first at Namkhat, here we met natives who brought us rice and a few eggs. Didn’t have a scrap in my pack, but God looked down on us and saw our sad plight. Later at Kwangon where I am now, we had some little chicks and an abundance of rice, salt and tobacco etc. I am writing this by moonlight, while my chicken soup is being prepared by my servant. How very lucky we have been. Marched twenty miles today.

20th April 1943

Things are looking up, things are getting better and better every day, as we are getting nearer the Chindwin and safety. I am blessed with an attack of dysentery and am almost too weak to walk, but I am pushing on, not giving up now. Am not eating rice as this is the cause of my illness. Am foraging food very well, having had as much as I would for us all during the last two days. Now three days march from the Chindwin, we covered fifteen miles today.

21st April 1943

Foraging food at Naungbamu today had bananas, eggs, chickens, vegetables and native tobacco. Am very fortunate to have had so many letters dropped, as they have been so very useful and made a good substitute for cigarette papers. I had eight eggs yesterday and I needed them very badly. Am getting much better now, still weak (but aren’t we all) but going well. Covered sixteen miles today.

22nd April 1943

We have talked so much and longed for so long this Chindwin River. Now we are about twelve miles away from it, but can’t make it tonight, decided to stay the night here at Mene (Myene). No hope of sleep, thousands of mosquitos and ants, so here’s to the cooking pot. Marched fifteen miles today.

NB. It is quite remarkable that the group were able to march such distances at this point in time, when you consider their state of health, acute malnutrition and obvious exhaustion. You may also have noticed that Gerry records the miles made each day over the last period of the journey. This shows the mental countdown taking place in the men’s minds as they near their ultimate goal of the Chindwin River.

Seen below is a gallery of maps, tracing the dispersal party's journey from the moment they crossed the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway on the 12th April, until their re-crossing of the Chindwin River on the 24th April. The maps include the names of the various villages mentioned by Lt. Roberts in his diary. Please click on any map to bring it forward on the page.

Gerry Roberts' diary concludes:

24th April 1943

I have missed a day way back somewhere, no wonder really. The great Chindwin is within a stone’s throw from where I am sitting out the time and entering this (into the diary) and at last we are on the home bank. Crossed at noon and was greeted by the Seaforth Highlanders; a cigarette, a kind word and friendly troops, after what appears to be years cut away from everything and everybody, it almost doesn’t seem real.

The RAF came over to bomb certain targets thirty minutes after we crossed, (including) the place where we were sitting waiting for boats to take us across. They had mistaken the target, as I am told that my party had been reported by a Gurkha patrol to be a party of Japs, hence the bombing. Grand chaps these Seaforth’s, they have shared their rations with the men and the officer in charge shared his with me. Have made arrangements by field telephone for rations and transport after crossing the Chin Hills. I spoke to Divisional HQ who were thrilled that we were safe and were glad to do anything for us. They all think that we are great heroes. All my time is occupied answering questions. Am staying here until the 26th for a rest, even though it is only twelve miles to Thanan, where the road starts.

NB. Gerry’s diary reads slightly in advance of the other resource for 5 Column’s dispersal back to India in 1943, Bernard Fergusson’s book, Beyond the Chindwin. For example, the chance meeting with Fergusson’s party at Pakaw; Gerry has this down as the 16th April, whilst Fergusson remembers it as the 18th.

25th April 1943

Have filled my tummy to capacity. Been to the villages on the river bank to get bananas and coconuts for the men, that’s if they can find room for any more food! V Force sent me rations last night consisting of sugar, tinned fruit, tea, milk, bully, canned peas, salt and cigarettes; grand show. Been down to river to bathe, forgot about the Japs being somewhere on the other bank, but I had to get clean and rid myself of this detritus.

26th April 1943

Left Tonhe on the Chindwin at 2am to march to Thanan. Over the hills again but so different now to when we crossed these hills to go into Burma. No mules or horses now, no loads and so many absent faces. We halt at a stream between the hills for a meal. We arrived at Thanan at 10am. What a performance, cameramen, pressmen, film photographers, treating us as the world’s greatest heroes.

To conclude this story, seen below is a photograph of Flight-Lieutenant Denny Sharp's dispersal party, having safely crossed the Chindwin River on the 24th April 1943. Presumably, Gerry Roberts is present amongst these men who look more like a group of pirates than soldiers from the King’s Regiment. I believe that the man kneeling in the centre of the front row, with his bush hat folded on one side and looking over to the left, is Denny Sharp. I am fairly certain that next to Lt. Sharp, and also with one hand on Judy the dog, is none other than Sgt. Ronald Rothwell. This identification is based solely on the resemblance of this man to the newspaper cutting photograph of Rothwell in the second gallery of images featured as part of this narrative.

24th April 1943

I have missed a day way back somewhere, no wonder really. The great Chindwin is within a stone’s throw from where I am sitting out the time and entering this (into the diary) and at last we are on the home bank. Crossed at noon and was greeted by the Seaforth Highlanders; a cigarette, a kind word and friendly troops, after what appears to be years cut away from everything and everybody, it almost doesn’t seem real.

The RAF came over to bomb certain targets thirty minutes after we crossed, (including) the place where we were sitting waiting for boats to take us across. They had mistaken the target, as I am told that my party had been reported by a Gurkha patrol to be a party of Japs, hence the bombing. Grand chaps these Seaforth’s, they have shared their rations with the men and the officer in charge shared his with me. Have made arrangements by field telephone for rations and transport after crossing the Chin Hills. I spoke to Divisional HQ who were thrilled that we were safe and were glad to do anything for us. They all think that we are great heroes. All my time is occupied answering questions. Am staying here until the 26th for a rest, even though it is only twelve miles to Thanan, where the road starts.

NB. Gerry’s diary reads slightly in advance of the other resource for 5 Column’s dispersal back to India in 1943, Bernard Fergusson’s book, Beyond the Chindwin. For example, the chance meeting with Fergusson’s party at Pakaw; Gerry has this down as the 16th April, whilst Fergusson remembers it as the 18th.

25th April 1943

Have filled my tummy to capacity. Been to the villages on the river bank to get bananas and coconuts for the men, that’s if they can find room for any more food! V Force sent me rations last night consisting of sugar, tinned fruit, tea, milk, bully, canned peas, salt and cigarettes; grand show. Been down to river to bathe, forgot about the Japs being somewhere on the other bank, but I had to get clean and rid myself of this detritus.

26th April 1943

Left Tonhe on the Chindwin at 2am to march to Thanan. Over the hills again but so different now to when we crossed these hills to go into Burma. No mules or horses now, no loads and so many absent faces. We halt at a stream between the hills for a meal. We arrived at Thanan at 10am. What a performance, cameramen, pressmen, film photographers, treating us as the world’s greatest heroes.

To conclude this story, seen below is a photograph of Flight-Lieutenant Denny Sharp's dispersal party, having safely crossed the Chindwin River on the 24th April 1943. Presumably, Gerry Roberts is present amongst these men who look more like a group of pirates than soldiers from the King’s Regiment. I believe that the man kneeling in the centre of the front row, with his bush hat folded on one side and looking over to the left, is Denny Sharp. I am fairly certain that next to Lt. Sharp, and also with one hand on Judy the dog, is none other than Sgt. Ronald Rothwell. This identification is based solely on the resemblance of this man to the newspaper cutting photograph of Rothwell in the second gallery of images featured as part of this narrative.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, October 2017.