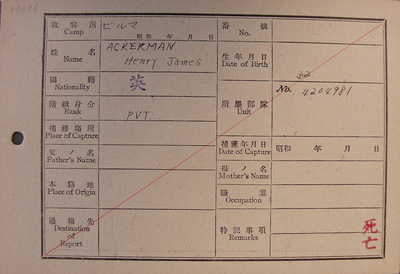

Pte. Henry James Ackerman

Royal Welch Fusiliers Cap Badge.

Royal Welch Fusiliers Cap Badge.

Henry James Ackerman, known to his friends and family as Harold was the son of George and Elizabeth Ackerman from Gendros, a suburb of Swansea in South Wales.

He began his Army Service with the Royal Welch Fusiliers, but was selected for overseas duty and became attached to the 13th Battalion of the King's Liverpool Regiment in the autumn of 1942.

Henry arrived at Bombay and passed through the famous Deolali Army Camp, before journeying to the Central Provinces of India and joining Chindit training at a place called Saugor on 30th September.

He was allocated to Column 5 which was commanded by Major Bernard Fergusson and commenced his training, learning such skills as map and compass reading, river-craft and generally how to survive in the scrub jungle of the area.

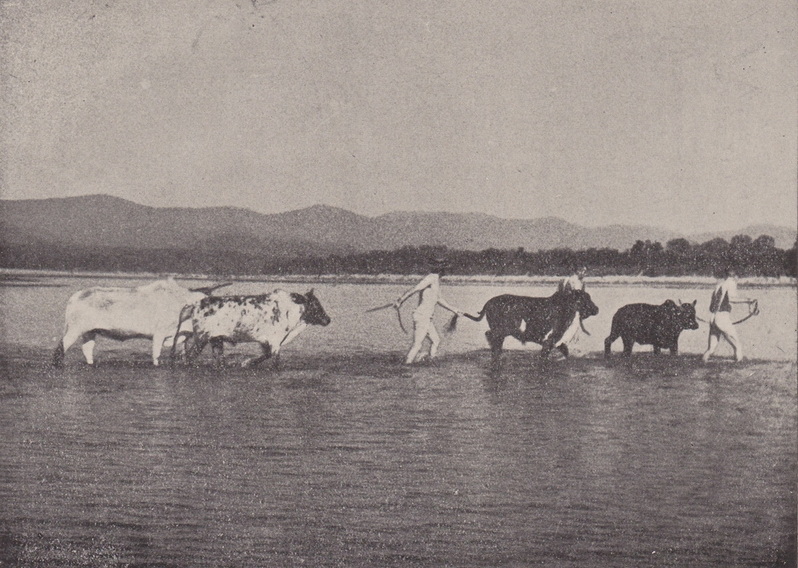

Henry was then posted to the Animal Transport section of the Column, where he took charge of one of the unit's bullocks. These cumbersome creatures were to be used in the first instance as pack animals, but eventually were to be eaten by the men when other rations began to run out.

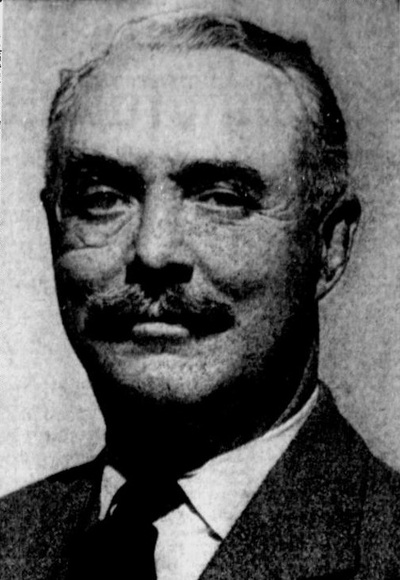

In his book, 'Beyond the Chindwin', Bernard Fergusson remembered Henry Ackerman from those early days at Saugor:

One of the bullock drivers was Akerman, a little Welshman with whom I often passed the time of day. He used to stump along with an old pipe stuck in his mouth; in accordance with the custom of my own regiment, I always allowed pipes on the line of march. Once I asked him how he was getting along with his bullock. He replied, in his sing-song Welsh voice: "Sir, I am so bewildered, I do not know which is the bullock, myself or the bullock."

Another officer from Column 5, Lieutenant Philip Stibbe also remembered Pte. Ackerman. In his book, 'Return via Rangoon', Stibbe recalls the long march from Imphal down to the banks of the Chindwin River in February 1943:

Stretched out in single file the column was over half a mile long. It was a fine sight and the men were in good heart that night. I waited until the Perimeter Platoon had gone by and then prepared to follow on a few hundred yards behind. Just at that moment I heard a musical Welsh voice indulging in a delightful flow of bad language and round the corner came Private Ackerman and his bullocks.

These bullocks were a last minute addition of Wingate's and with specially constructed carts, they proved extremely useful for carrying extra loads and eventually for eating purposes. That evening Ackerman and his band of 'bullockteers' were finding them troublesome. They never liked going up hill and later on one of them lay down and refused to budge an inch until a fire was lit under its tail. We then had difficulty in preventing the animal from overtaking the Major!

He began his Army Service with the Royal Welch Fusiliers, but was selected for overseas duty and became attached to the 13th Battalion of the King's Liverpool Regiment in the autumn of 1942.

Henry arrived at Bombay and passed through the famous Deolali Army Camp, before journeying to the Central Provinces of India and joining Chindit training at a place called Saugor on 30th September.

He was allocated to Column 5 which was commanded by Major Bernard Fergusson and commenced his training, learning such skills as map and compass reading, river-craft and generally how to survive in the scrub jungle of the area.

Henry was then posted to the Animal Transport section of the Column, where he took charge of one of the unit's bullocks. These cumbersome creatures were to be used in the first instance as pack animals, but eventually were to be eaten by the men when other rations began to run out.

In his book, 'Beyond the Chindwin', Bernard Fergusson remembered Henry Ackerman from those early days at Saugor:

One of the bullock drivers was Akerman, a little Welshman with whom I often passed the time of day. He used to stump along with an old pipe stuck in his mouth; in accordance with the custom of my own regiment, I always allowed pipes on the line of march. Once I asked him how he was getting along with his bullock. He replied, in his sing-song Welsh voice: "Sir, I am so bewildered, I do not know which is the bullock, myself or the bullock."

Another officer from Column 5, Lieutenant Philip Stibbe also remembered Pte. Ackerman. In his book, 'Return via Rangoon', Stibbe recalls the long march from Imphal down to the banks of the Chindwin River in February 1943:

Stretched out in single file the column was over half a mile long. It was a fine sight and the men were in good heart that night. I waited until the Perimeter Platoon had gone by and then prepared to follow on a few hundred yards behind. Just at that moment I heard a musical Welsh voice indulging in a delightful flow of bad language and round the corner came Private Ackerman and his bullocks.

These bullocks were a last minute addition of Wingate's and with specially constructed carts, they proved extremely useful for carrying extra loads and eventually for eating purposes. That evening Ackerman and his band of 'bullockteers' were finding them troublesome. They never liked going up hill and later on one of them lay down and refused to budge an inch until a fire was lit under its tail. We then had difficulty in preventing the animal from overtaking the Major!

As Philip Stibbe described the Chindits moved up to Imphal in Assam during January 1943, Column 5 crossed over the Chindwin River at a place called Hwematte on the 15th February that year. Henry would have had to swim his animal over the river as there were no suitably robust boats available to ferry such large beasts across.

Column 5 were one of the units designated by Wingate to demolish the Myitkhina-Mandalay Railway at a place called Bonchaung. The column moved quickly over the next few weeks to reach their objective. They succeeded in demolishing the railway line and the bridge at Bonchaung before moving on eastwards towards the Irrawaddy River. Once across this river and after three further weeks inside Burma, the Chindits were instructed to return to India and dispersal was ordered by Brigadier Wingate.

Whilst attempting this journey Column 5 had to re-cross not one, but two of the great and expansive Burmese rivers. On April 1st the unit were fording the fast flowing Shweli River. They had managed to reach what they thought was the far bank, but discovered to their horror that they were actually on a large sandbank in the middle of the river, with still some 80 yards of fast flowing water between them and their ultimate goal.

Exhausted, malnourished and starving, this proved too much for some of the men and they slumped down on to the sands to rest. Fergusson and his officers urged the men to rise up and attempt the final crossing, as, by this time a Japanese patrol had closed in on the now desperate Chindits. A section of Burma Riflemen decide to attempt the crossing, but two were quickly swept away by the foaming waters, this was the final straw for the other men and they refused to carry on.

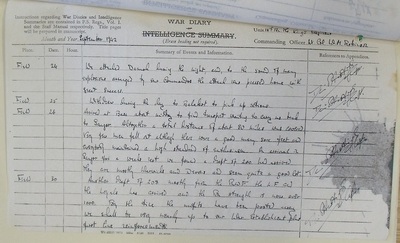

There are two witness statements given by men after the operation that describe the situation at the Shweli on the 1st April 1943. One from Lieutenant Bill Edge and the other from Pte. W. Ryan.

Bill Edge recalled:

In the small hours of the 1st April 1943, a dispersal group commanded by Major B. Fergusson crossed the Shweli River from west to east at a point near Tokkin village. Some men were ferried half-way across by boat to a sandbank, but failed to complete the crossing, which involved wading breast-high some fifty yards in a very fast current. These men did not rejoin the Column and have not been seen since.

Pte. Ryan remembered:

I was with No. 5 Column at the crossing of the River Shweli on the 1st April 1943. With Pte. Pierce, I was one of the last to leave the sandbank. On reaching the east bank we lost our way and did not finally leave the river bank until daybreak. Before leaving I saw a group of approximately 40 to 50 British Other Ranks and Gurkhas still on the sandbank. They did not seem to be attempting to cross. They had arms and ammunition.

I had not gone more than thirty yards inland, when I heard a volley of shots close at hand, but I could not tell who was firing. There were Japs in the village just two miles away. We re-joined the Column which was approximately two miles away and were the last men to do so.

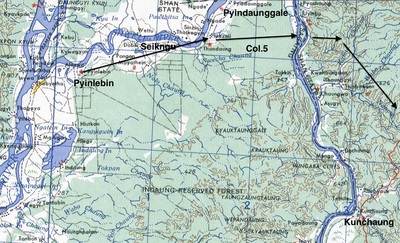

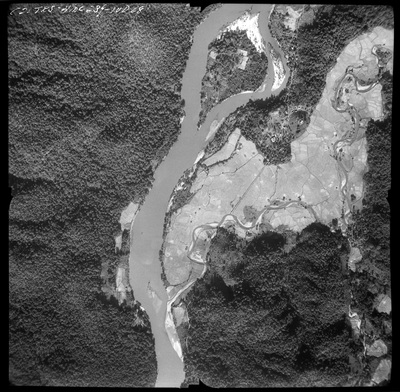

Seen below are two images in relation to the Shweli sandbank incident on April 1st 1943. Firstly, a map showing Column 5's journey during the days leading up to the Shweli crossing at Tokkin and secondly, an aerial photograph of the same general area. The sandbank shown in the photograph cannot be confirmed as being the one in question. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Column 5 were one of the units designated by Wingate to demolish the Myitkhina-Mandalay Railway at a place called Bonchaung. The column moved quickly over the next few weeks to reach their objective. They succeeded in demolishing the railway line and the bridge at Bonchaung before moving on eastwards towards the Irrawaddy River. Once across this river and after three further weeks inside Burma, the Chindits were instructed to return to India and dispersal was ordered by Brigadier Wingate.

Whilst attempting this journey Column 5 had to re-cross not one, but two of the great and expansive Burmese rivers. On April 1st the unit were fording the fast flowing Shweli River. They had managed to reach what they thought was the far bank, but discovered to their horror that they were actually on a large sandbank in the middle of the river, with still some 80 yards of fast flowing water between them and their ultimate goal.

Exhausted, malnourished and starving, this proved too much for some of the men and they slumped down on to the sands to rest. Fergusson and his officers urged the men to rise up and attempt the final crossing, as, by this time a Japanese patrol had closed in on the now desperate Chindits. A section of Burma Riflemen decide to attempt the crossing, but two were quickly swept away by the foaming waters, this was the final straw for the other men and they refused to carry on.

There are two witness statements given by men after the operation that describe the situation at the Shweli on the 1st April 1943. One from Lieutenant Bill Edge and the other from Pte. W. Ryan.

Bill Edge recalled:

In the small hours of the 1st April 1943, a dispersal group commanded by Major B. Fergusson crossed the Shweli River from west to east at a point near Tokkin village. Some men were ferried half-way across by boat to a sandbank, but failed to complete the crossing, which involved wading breast-high some fifty yards in a very fast current. These men did not rejoin the Column and have not been seen since.

Pte. Ryan remembered:

I was with No. 5 Column at the crossing of the River Shweli on the 1st April 1943. With Pte. Pierce, I was one of the last to leave the sandbank. On reaching the east bank we lost our way and did not finally leave the river bank until daybreak. Before leaving I saw a group of approximately 40 to 50 British Other Ranks and Gurkhas still on the sandbank. They did not seem to be attempting to cross. They had arms and ammunition.

I had not gone more than thirty yards inland, when I heard a volley of shots close at hand, but I could not tell who was firing. There were Japs in the village just two miles away. We re-joined the Column which was approximately two miles away and were the last men to do so.

Seen below are two images in relation to the Shweli sandbank incident on April 1st 1943. Firstly, a map showing Column 5's journey during the days leading up to the Shweli crossing at Tokkin and secondly, an aerial photograph of the same general area. The sandbank shown in the photograph cannot be confirmed as being the one in question. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

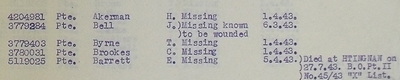

Some 40 men from Column 5 including Pte. Ackerman were captured by the enemy that day and were taken to a jungle holding camp. As the days wore on more and more exhausted Chindits were collected by the Japanese and sent on to various POW Camps in the area. Finally, it was decided to send them all down to Rangoon Central Jail and this is where Henry Ackerman sadly perished.

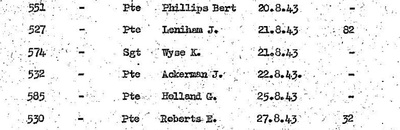

From documents held at the National Archives it is stated that he died in Block 6 of the jail on 22nd August 1943, this date differs from the CWGC website, which gives the 2nd of August as Henry's date of death. By translating his POW index card I discovered that Henry's cause of death was malaria and that his POW number was 532.

Almost all of the men captured on the sandbank on the 1st April 1943 perished inside Rangoon Jail. In fact, most of the men from Column 5 who became prisoners of war did not return home to their families.

For more information about the Chindits who became prisoners of war, please click on the following link:

Chindit POW's

Henry James Ackerman is buried in Rangoon War Cemetery along with many of his Chindit comrades. On his memorial plaque there is the inscription "Buried near this spot", this relates to the fact, that when some of the burials were transferred from the original place of internment (the English Cantonment Cemetery), the remains of each man could not be precisely identified and so they were all re-buried together.

For more information about the English Cantonment and Rangoon War Cemeteries, please click on the following link and scroll down the page to find the relevant section:

Memorials and Cemeteries

Here are Pte. Henry Ackerman's CWCG details: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2259617/ACKERMAN,%20HENRY%20JAMES

In late November 2013 I had the good fortune to receive an email contact from Stuart Hocknell, a relation by marriage of Henry Ackerman. Stuart was looking for more details about Henry and his time in Burma, in order to complete an obituary for him, which was to be published on the Fforestfach History website. After exchanging some information, Stuart has completed the obituary, which you can read here:

http://www.fforestfachhistory.com/memorial_%20HJAckerman_1939-45.html

The Ackerman family received a short letter in July 1943 from another officer who served in Column 5 on Operation Longcloth. Lieutenant Gerry Roberts, a former Welsh Guardsman had these kind words for Henry's father:

Dear Mr. Ackerman,

It is with the deepest regret that I write to inform you that your son is missing. It is quite possible that he may be a prisoner of war, but I have no evidence that this is the case. If I receive any news of your son I will let you know at once.

I know your son very well, being one from the old country myself. I took a great interest in him and was privileged to have him under my command during the recent operations. The last line of the letter is difficult to make out, but says something like, 'I found him at all times to be in the best of spirits'.

Signed

Lieutenant W. Roberts, 13th King's Liverpool.

Seen below is a gallery of images relating to the story of Pte. Henry James Ackerman. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

From documents held at the National Archives it is stated that he died in Block 6 of the jail on 22nd August 1943, this date differs from the CWGC website, which gives the 2nd of August as Henry's date of death. By translating his POW index card I discovered that Henry's cause of death was malaria and that his POW number was 532.

Almost all of the men captured on the sandbank on the 1st April 1943 perished inside Rangoon Jail. In fact, most of the men from Column 5 who became prisoners of war did not return home to their families.

For more information about the Chindits who became prisoners of war, please click on the following link:

Chindit POW's

Henry James Ackerman is buried in Rangoon War Cemetery along with many of his Chindit comrades. On his memorial plaque there is the inscription "Buried near this spot", this relates to the fact, that when some of the burials were transferred from the original place of internment (the English Cantonment Cemetery), the remains of each man could not be precisely identified and so they were all re-buried together.

For more information about the English Cantonment and Rangoon War Cemeteries, please click on the following link and scroll down the page to find the relevant section:

Memorials and Cemeteries

Here are Pte. Henry Ackerman's CWCG details: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2259617/ACKERMAN,%20HENRY%20JAMES

In late November 2013 I had the good fortune to receive an email contact from Stuart Hocknell, a relation by marriage of Henry Ackerman. Stuart was looking for more details about Henry and his time in Burma, in order to complete an obituary for him, which was to be published on the Fforestfach History website. After exchanging some information, Stuart has completed the obituary, which you can read here:

http://www.fforestfachhistory.com/memorial_%20HJAckerman_1939-45.html

The Ackerman family received a short letter in July 1943 from another officer who served in Column 5 on Operation Longcloth. Lieutenant Gerry Roberts, a former Welsh Guardsman had these kind words for Henry's father:

Dear Mr. Ackerman,

It is with the deepest regret that I write to inform you that your son is missing. It is quite possible that he may be a prisoner of war, but I have no evidence that this is the case. If I receive any news of your son I will let you know at once.

I know your son very well, being one from the old country myself. I took a great interest in him and was privileged to have him under my command during the recent operations. The last line of the letter is difficult to make out, but says something like, 'I found him at all times to be in the best of spirits'.

Signed

Lieutenant W. Roberts, 13th King's Liverpool.

Seen below is a gallery of images relating to the story of Pte. Henry James Ackerman. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

I have decided to leave the last word in this story to Bernard Fergusson. On the 1st April 1943 he agonised for many hours whether to stay longer on the east bank of the Shweli, in the hope that the men still stranded on the sandbank would find it in their hearts to attempt that final short, but dangerous crossing. In his book, 'Beyond the Chindwin' he wrote:

In the end I made the decision to come away. I have it on my conscience for as long as live; but stand by that decision and believe it to have been the correct one. Those who think otherwise may well be right. Some of my officers volunteered to stay, but I refused them permission to do so.

Nevertheless, the crossing of the Shweli River will haunt me all my life; and to my mind the decision which fell to me there, was as cruel as any which could fall on the shoulders of a junior commander.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Stuart Hocknell for his valued contribution to the story of Henry Ackerman.

Update 15/04/2015.

Seen below is an image of the bullock handlers from Chindit Column 5 driving their animals across the Chindwin River in February 1943. It is not known if Henry Ackerman is featured in the photograph.

In the end I made the decision to come away. I have it on my conscience for as long as live; but stand by that decision and believe it to have been the correct one. Those who think otherwise may well be right. Some of my officers volunteered to stay, but I refused them permission to do so.

Nevertheless, the crossing of the Shweli River will haunt me all my life; and to my mind the decision which fell to me there, was as cruel as any which could fall on the shoulders of a junior commander.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Stuart Hocknell for his valued contribution to the story of Henry Ackerman.

Update 15/04/2015.

Seen below is an image of the bullock handlers from Chindit Column 5 driving their animals across the Chindwin River in February 1943. It is not known if Henry Ackerman is featured in the photograph.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, September 2014.