Matron Agnes McGearey

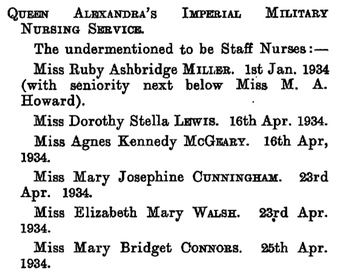

Promotion to Staff Nurse 1934.

Promotion to Staff Nurse 1934.

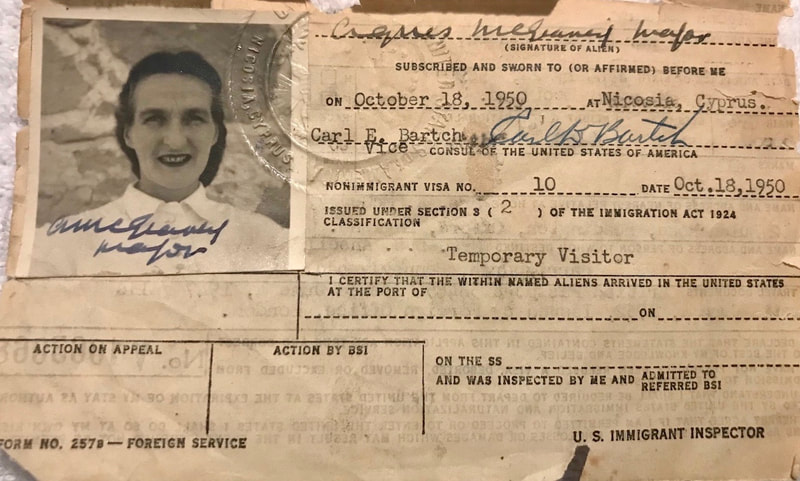

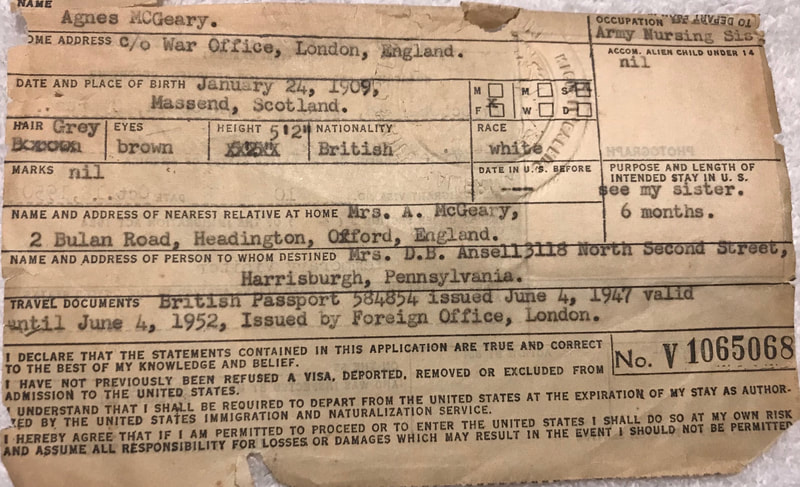

Agnes Kennedy McGearey was born in 1909 at Mossend, a small town in North Lanarkshire, Scotland. By the end of WW2, her name would become synonymous with that of the Chindits and her efforts to rebuild the strength of those who survived these campaigns would become stuff of legend.

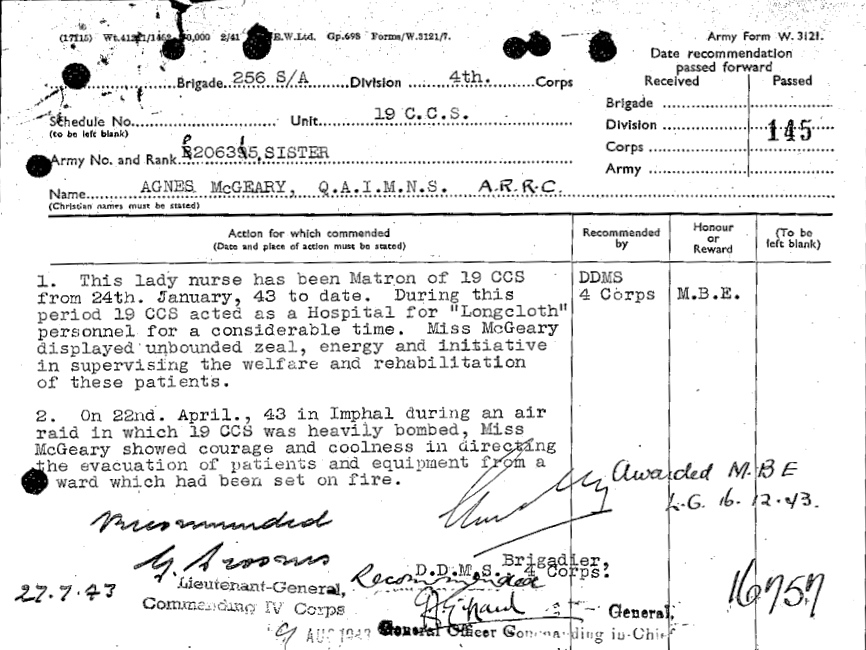

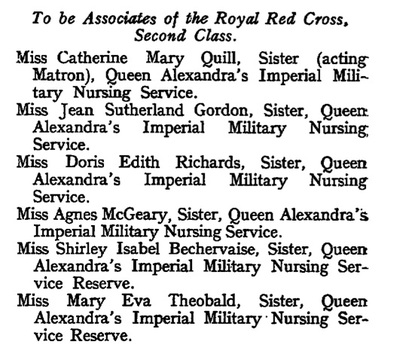

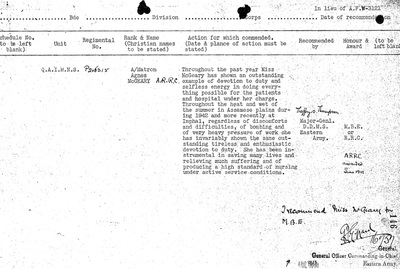

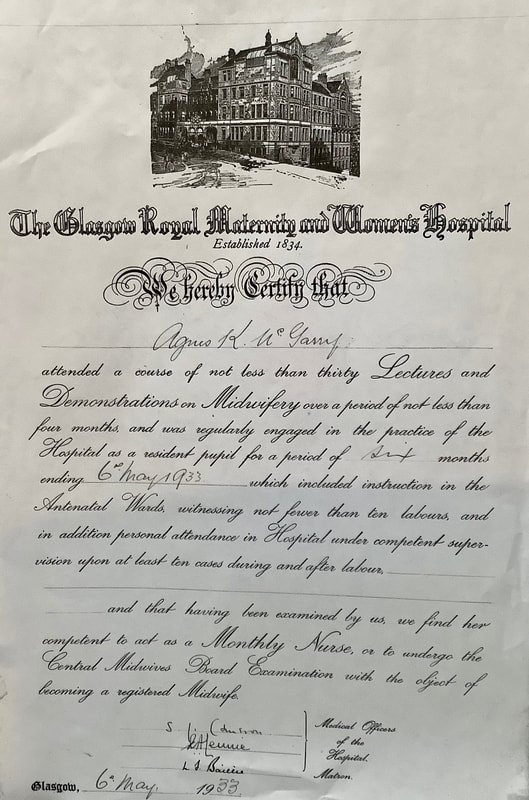

Agnes, known to her nursing colleagues as Aggie, became a Staff Nurse within the Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS) on the 16th April 1934. After her early service with the unit, including a posting to Malta in 1937 and promotion to Acting Matron, she was awarded the Associate of the Royal Red Cross Medal which was announced in the London Gazette in July 1941.

"A Mother to Them All" (a quote attributed to Major-General Derek Tulloch, Wingate's Chief of Staff in 1944). This was how the sick and wounded from the two Chindit campaigns remembered Matron McGearey and her almost super-human endeavours in returning these stricken men back to health.

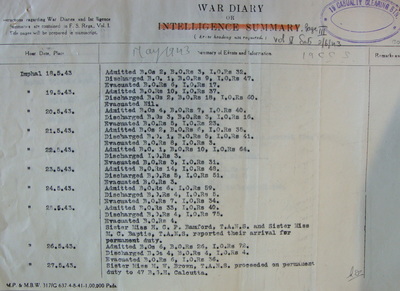

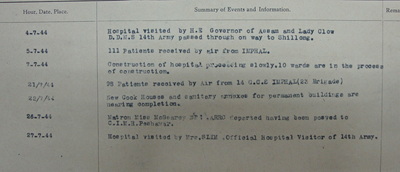

Agnes McGearey was working in India at the 19th Casualty Clearing Station, based at Imphal at the time of the first Wingate expedition. The small hospital, under the command of Temporary Lt. Colonel G.G. Smith was really only a collection of roughly constructed basha type huts made from bamboo and grass. The station had previously been based in Meerut, but had moved closer to the Assam/Burmese border presumably in readiness for the returning Chindits of Operation Longcloth.

Matron McGearey is not surprisingly mentioned in many books on the subject of the Chindits. Here are some examples, which I think help explain her character and describe the valiant work she undertook on their behalf. The first quote is taken from the extensive biography of Orde Wingate written by Christopher Sykes. If nothing else, this narrative brings home the incredibly special relationship between McGearey and the Chindit commander. Please note the different spelling of her surname, which occurs almost consistently in regards to mentions of Agnes in books and most official documents:

By the 5th June (1943) the exodus was over. While all these lesser miseries of victory were going forward, Wingate felt the need, as perhaps he had never felt it before, to express the ideas and experience within him. He wanted to write a memorandum. He also wanted rest.

At this moment of his life he made a deep and curious friendship. The 19th Military Clearing Station at Imphal was under the direction of Matron Agnes McGeary. She was a small, vigorous, efficient and altruistic Scotswoman. Her kindly nature was an eminently practical one, and she had found her vocation in nursing. Descriptions of Agnes McGeary by people who knew her put one in mind of Florence Nightingale.

She ran the hospital at Imphal with medical thoroughness and a natural power of leadership. She was a stern humanitarian, and like most proficient people in this sphere was without the sentimental sensitivity which often masquerades as the angel of charity. No military commander enjoyed a surer authority over men than this imperious woman. She needed to show sternness rather than indulgence in most cases, and for a strange reason.

A danger which confronted many Chindits on their return to civilised life was of sinking into a fatal torpor when surrounded with the luxuries of cleanliness, a soft bed, and white cool sheets. One may think it a pleasant way to leave this life, but a description in Calvert's book of what happened under such circumstances makes one think again. A less expert nurse might have lost lives through kindly pampering.

"Matron McGeary sometimes seemed cruel when she forced exhausted men out of bed, made them dress and walk about, and fairly threw them on their own resources. But she never seems to have made a false diagnosis or prescribed wrong treatment." (Mike Calvert).

In the course of looking after the invalids of 77 Brigade she learned what they had done. She was filled with admiration, and identified herself with these men. When their commander came back to Imphal at the end of May and called at the hospital to inquire after the patients from his Brigade, Agnes McGeary saw that he was endangering himself by excessive activity. He told her that he intended to settle down to work on his report. There were two empty rooms in a wing of the hospital. She ordered Wingate to install himself in these rooms and write his report while undergoing a regime of rest supervised by herself. He obeyed.

The next quotation comes from the book, Wingate, in Peace and War, written by Major-General Derek Tulloch. This quote was relayed to the author by several of the Column Commanders who had served on the first Chindit expedition in 1943:

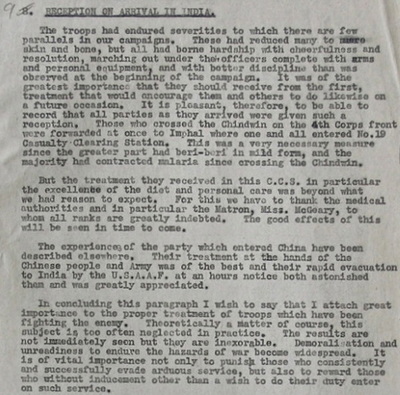

"Upon arrival at Imphal we were told that everybody had to go into hospital. Those who were fit would be examined and discharged in a couple of days, and those who were not would be detained. On arrival we were admitted by the Matron, Agnes McGeary, ARRC, who on that evening seemed just like any other Matron. She gave us a smiling welcome and packed us off to bed. During the next few days, however, we came to know her true worth; she was not only a very efficient Matron, she was mother to us all."

Agnes, known to her nursing colleagues as Aggie, became a Staff Nurse within the Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS) on the 16th April 1934. After her early service with the unit, including a posting to Malta in 1937 and promotion to Acting Matron, she was awarded the Associate of the Royal Red Cross Medal which was announced in the London Gazette in July 1941.

"A Mother to Them All" (a quote attributed to Major-General Derek Tulloch, Wingate's Chief of Staff in 1944). This was how the sick and wounded from the two Chindit campaigns remembered Matron McGearey and her almost super-human endeavours in returning these stricken men back to health.

Agnes McGearey was working in India at the 19th Casualty Clearing Station, based at Imphal at the time of the first Wingate expedition. The small hospital, under the command of Temporary Lt. Colonel G.G. Smith was really only a collection of roughly constructed basha type huts made from bamboo and grass. The station had previously been based in Meerut, but had moved closer to the Assam/Burmese border presumably in readiness for the returning Chindits of Operation Longcloth.

Matron McGearey is not surprisingly mentioned in many books on the subject of the Chindits. Here are some examples, which I think help explain her character and describe the valiant work she undertook on their behalf. The first quote is taken from the extensive biography of Orde Wingate written by Christopher Sykes. If nothing else, this narrative brings home the incredibly special relationship between McGearey and the Chindit commander. Please note the different spelling of her surname, which occurs almost consistently in regards to mentions of Agnes in books and most official documents:

By the 5th June (1943) the exodus was over. While all these lesser miseries of victory were going forward, Wingate felt the need, as perhaps he had never felt it before, to express the ideas and experience within him. He wanted to write a memorandum. He also wanted rest.

At this moment of his life he made a deep and curious friendship. The 19th Military Clearing Station at Imphal was under the direction of Matron Agnes McGeary. She was a small, vigorous, efficient and altruistic Scotswoman. Her kindly nature was an eminently practical one, and she had found her vocation in nursing. Descriptions of Agnes McGeary by people who knew her put one in mind of Florence Nightingale.

She ran the hospital at Imphal with medical thoroughness and a natural power of leadership. She was a stern humanitarian, and like most proficient people in this sphere was without the sentimental sensitivity which often masquerades as the angel of charity. No military commander enjoyed a surer authority over men than this imperious woman. She needed to show sternness rather than indulgence in most cases, and for a strange reason.

A danger which confronted many Chindits on their return to civilised life was of sinking into a fatal torpor when surrounded with the luxuries of cleanliness, a soft bed, and white cool sheets. One may think it a pleasant way to leave this life, but a description in Calvert's book of what happened under such circumstances makes one think again. A less expert nurse might have lost lives through kindly pampering.

"Matron McGeary sometimes seemed cruel when she forced exhausted men out of bed, made them dress and walk about, and fairly threw them on their own resources. But she never seems to have made a false diagnosis or prescribed wrong treatment." (Mike Calvert).

In the course of looking after the invalids of 77 Brigade she learned what they had done. She was filled with admiration, and identified herself with these men. When their commander came back to Imphal at the end of May and called at the hospital to inquire after the patients from his Brigade, Agnes McGeary saw that he was endangering himself by excessive activity. He told her that he intended to settle down to work on his report. There were two empty rooms in a wing of the hospital. She ordered Wingate to install himself in these rooms and write his report while undergoing a regime of rest supervised by herself. He obeyed.

The next quotation comes from the book, Wingate, in Peace and War, written by Major-General Derek Tulloch. This quote was relayed to the author by several of the Column Commanders who had served on the first Chindit expedition in 1943:

"Upon arrival at Imphal we were told that everybody had to go into hospital. Those who were fit would be examined and discharged in a couple of days, and those who were not would be detained. On arrival we were admitted by the Matron, Agnes McGeary, ARRC, who on that evening seemed just like any other Matron. She gave us a smiling welcome and packed us off to bed. During the next few days, however, we came to know her true worth; she was not only a very efficient Matron, she was mother to us all."

The next quotation comes from the book 'Quiet Heroines' by Brenda McBryde. This deals with the medical treatment of men from the second Chindit expedition in 1944 and mentions for the first time, Matron McGearey's involvement in nursing Orde Wingate back to health after he had contracted typhoid by drinking foul water during a plane journey back to India via North Africa.

The Chindits carried no wounded. If a man could no longer walk, his friends dispatched him humanely rather than leave him for the Japanese to torture. The first medical unit to receive the survivors was the CCS at Sylhet near Imphal where Aggie McGeary was Matron at the special request of Orde Wingate himself.

She had nursed him through a bad bout of typhoid during the previous year (October 1943) and he believed that he owed her his life. She was the kind of woman he wanted to look after his men, and his request was duly granted. His judgement proved to be impeccable. She took on wholeheartedly the care of the Chindits and became their staunch champion.

When they were brought to her, usually late at night, in a state of exhaustion and starvation, some weighing no more than four stones, she put them to bed and spoiled them with every indulgence that was possible to obtain and occasionally some that were impossible. Nothing was too much trouble for her if it could recompense these brave men for the hardships they had suffered. Nurse Maureen Ferris remembered:

"They were scarecrows, starving, mentally and physically exhausted, but simply great men."

Matron McGeary caused more than a flutter of discontent amongst the more regimentally minded Matrons of the QAIMNS by dispensing summarily with all red tape. Usual channels were not for her. She went straight to General Wingate with her requests and was given everything she wanted. Her deceptively fragile appearance hid a woman of iron. Small and dainty, she was dynamite in a lace doyle.

But the final word on Aggie McGeary must come from the late Brigadier Bernard Fergusson in his book The Wild Green Earth:

I must mention the famous, the impish, the kindly, the mutinous, the saintly, the wicked, the beloved, the Glasgow-Irish, the always-on-the-verge-of-court-martial, Matron Agnes McGeary, MBE.

She cheeked the Generals, scolded the doctors, she bullied me. She saved Wingate's life when he was dying of typhoid. She stole for the wounded. She brought back to health many who would otherwise have died. She raided the Ordnance Stores. She embezzled creature comforts. She vamped Brigadiers. She cheered the dying. She wrote letters to the bereaved and when she got answers from them, she wrote again, and again, and still again.

She sent me a clipper for my beard whilst in Burma and a live goose by Dakota for my dinner. She was a darling who possessed all our hearts, and in whatever row with authority she is involved in today, she has all our wishes for a happy issue out of all the afflictions she so lightheartedly brings upon herself for the sake of others. I only hope that I am never under her command. Indeed, I have but one hope more fervent than that, that she is never under mine.

The Chindits carried no wounded. If a man could no longer walk, his friends dispatched him humanely rather than leave him for the Japanese to torture. The first medical unit to receive the survivors was the CCS at Sylhet near Imphal where Aggie McGeary was Matron at the special request of Orde Wingate himself.

She had nursed him through a bad bout of typhoid during the previous year (October 1943) and he believed that he owed her his life. She was the kind of woman he wanted to look after his men, and his request was duly granted. His judgement proved to be impeccable. She took on wholeheartedly the care of the Chindits and became their staunch champion.

When they were brought to her, usually late at night, in a state of exhaustion and starvation, some weighing no more than four stones, she put them to bed and spoiled them with every indulgence that was possible to obtain and occasionally some that were impossible. Nothing was too much trouble for her if it could recompense these brave men for the hardships they had suffered. Nurse Maureen Ferris remembered:

"They were scarecrows, starving, mentally and physically exhausted, but simply great men."

Matron McGeary caused more than a flutter of discontent amongst the more regimentally minded Matrons of the QAIMNS by dispensing summarily with all red tape. Usual channels were not for her. She went straight to General Wingate with her requests and was given everything she wanted. Her deceptively fragile appearance hid a woman of iron. Small and dainty, she was dynamite in a lace doyle.

But the final word on Aggie McGeary must come from the late Brigadier Bernard Fergusson in his book The Wild Green Earth:

I must mention the famous, the impish, the kindly, the mutinous, the saintly, the wicked, the beloved, the Glasgow-Irish, the always-on-the-verge-of-court-martial, Matron Agnes McGeary, MBE.

She cheeked the Generals, scolded the doctors, she bullied me. She saved Wingate's life when he was dying of typhoid. She stole for the wounded. She brought back to health many who would otherwise have died. She raided the Ordnance Stores. She embezzled creature comforts. She vamped Brigadiers. She cheered the dying. She wrote letters to the bereaved and when she got answers from them, she wrote again, and again, and still again.

She sent me a clipper for my beard whilst in Burma and a live goose by Dakota for my dinner. She was a darling who possessed all our hearts, and in whatever row with authority she is involved in today, she has all our wishes for a happy issue out of all the afflictions she so lightheartedly brings upon herself for the sake of others. I only hope that I am never under her command. Indeed, I have but one hope more fervent than that, that she is never under mine.

Returning to Derek Tulloch's book, Wingate, In Peace and War, here is more detail regarding Wingate's almost fatal encounter with typhoid in October 1943:

Lord Louis (Mountbatten) was then genuinely determined to fulfil the tasks given to him at Quadrant, in which Wingate played so important a role. But to return to Wingate's illness. A few days after he arrived in hospital it was diagnosed as typhoid; and as he had delayed for so long before giving way to it, his powers of resistance had been weakened. Soon I learned that he was in serious danger of losing his life. Though this could not be proved, there was strong evidence that he had infected himself by drinking water from a flower vase at Castel Benito Airport in Tripoli, Libya.

The official medical historians have tried to make matters more sinister than they were, declaring that Wingate refused to be vaccinated or inoculated, considering himself immune from disease. These allegations at least I can personally disprove and indeed, had he not already had a typhoid inoculation, he would undoubtedly have died in hospital.

For the first few days Wingate was a difficult patient. He told me, but with more humour than malice, that he had little faith either in the desire or the ability of the hospital authorities to cure him. As a result of a cable to me from his wife Lorna, we were able to contact Agnes McGeary the Matron at Imphal, who had nursed Wingate and his men after Operation Longcloth.

As soon as Matron McGeary arrived from Delhi, Wingate settled down and ceased to worry about his condition. He had complete faith in her and obeyed her instructions implicitly. Undoubtedly her presence and authority with him determined the issue of his recovery. While he was under her care Wingate appeared to accept this quirk of fate with considerable equanimity. I visited him frequently and was able to assure him that his force and his headquarters were taking shape, carefully avoiding any mention of difficulties.

Churchill sent him a long personal telegram of sympathy and in addition gave orders that a daily bulletin on Wingate's condition should be sent to him until he was completely out of danger. Wingate's illness may have had a profound effect on Churchill's mind when he was considering the implications of the Quadrant Conference, before moving on to the next major discussion on strategy which was to take place at Cairo in November. Wingate's convalescence could be measured from the 10th November to the 1st December and during this period Matron McGeary had been in charge of him. But no part of this convalescence period could be deemed a complete rest from his work since he was discussing plans and writing letters in relation to the next Chindit campaign almost continuously.

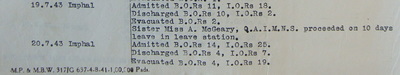

It is rumoured, but cannot be confirmed, that Agnes McGearey also tended to Lord Louis Mountbatten in March 1944, after he had injured his eye whilst travelling in an Army Jeep. What we do know for sure, is that after the casualties from the first Chindit operation had begun to settle down in July 1943, Agnes was able to take ten days leave from her duties at Imphal. On her return, the Casualty Station then moved just a few miles west, setting up at Sylhet prior to the commencement of Operation Thursday. It is recorded that she became known as Sister Saf Karo (translated as 'make it clean') by the men from the second Wingate expedition. On the 26th July 1944, Agnes transferred from 19 CCS to the Military Hospital at Peshawar, which was located in what is present day Pakistan, close to the famous Khyber Pass.

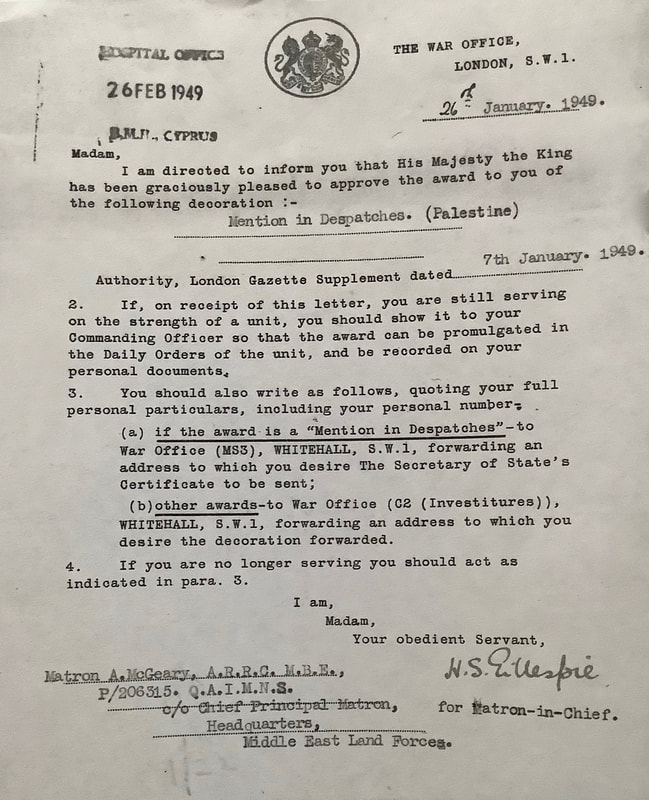

After the war, Agnes McGearey became Deputy Matron of the Cambridge Military Hospital at Aldershot, then continued her military service during the Korean War, before moving on to Malaysia in May 1953, where she took control of the hospital at Taiping in the State of Perak. It was whilst working at Taiping that Agnes began to feel unwell. Sadly, Agnes McGearey died in Oxford on the 9th December 1954, she was suffering from cancer. Here is how the sorrowful news was reported back in Malaysia.

From The Straits Times Newspaper, dated 15th December 1954:

London: Major Agnes McGeary MBE, formerly of the Queen Alexandra's Royal Army Nursing Corps, who was flown home seriously ill from Malaya in August, has died in England. Major McGeary came to Malaya in May 1953 to take charge of the hospital at Taiping.

Shown below is a gallery of images in relation to the nursing career of Agnes McGearey, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Lord Louis (Mountbatten) was then genuinely determined to fulfil the tasks given to him at Quadrant, in which Wingate played so important a role. But to return to Wingate's illness. A few days after he arrived in hospital it was diagnosed as typhoid; and as he had delayed for so long before giving way to it, his powers of resistance had been weakened. Soon I learned that he was in serious danger of losing his life. Though this could not be proved, there was strong evidence that he had infected himself by drinking water from a flower vase at Castel Benito Airport in Tripoli, Libya.

The official medical historians have tried to make matters more sinister than they were, declaring that Wingate refused to be vaccinated or inoculated, considering himself immune from disease. These allegations at least I can personally disprove and indeed, had he not already had a typhoid inoculation, he would undoubtedly have died in hospital.

For the first few days Wingate was a difficult patient. He told me, but with more humour than malice, that he had little faith either in the desire or the ability of the hospital authorities to cure him. As a result of a cable to me from his wife Lorna, we were able to contact Agnes McGeary the Matron at Imphal, who had nursed Wingate and his men after Operation Longcloth.

As soon as Matron McGeary arrived from Delhi, Wingate settled down and ceased to worry about his condition. He had complete faith in her and obeyed her instructions implicitly. Undoubtedly her presence and authority with him determined the issue of his recovery. While he was under her care Wingate appeared to accept this quirk of fate with considerable equanimity. I visited him frequently and was able to assure him that his force and his headquarters were taking shape, carefully avoiding any mention of difficulties.

Churchill sent him a long personal telegram of sympathy and in addition gave orders that a daily bulletin on Wingate's condition should be sent to him until he was completely out of danger. Wingate's illness may have had a profound effect on Churchill's mind when he was considering the implications of the Quadrant Conference, before moving on to the next major discussion on strategy which was to take place at Cairo in November. Wingate's convalescence could be measured from the 10th November to the 1st December and during this period Matron McGeary had been in charge of him. But no part of this convalescence period could be deemed a complete rest from his work since he was discussing plans and writing letters in relation to the next Chindit campaign almost continuously.

It is rumoured, but cannot be confirmed, that Agnes McGearey also tended to Lord Louis Mountbatten in March 1944, after he had injured his eye whilst travelling in an Army Jeep. What we do know for sure, is that after the casualties from the first Chindit operation had begun to settle down in July 1943, Agnes was able to take ten days leave from her duties at Imphal. On her return, the Casualty Station then moved just a few miles west, setting up at Sylhet prior to the commencement of Operation Thursday. It is recorded that she became known as Sister Saf Karo (translated as 'make it clean') by the men from the second Wingate expedition. On the 26th July 1944, Agnes transferred from 19 CCS to the Military Hospital at Peshawar, which was located in what is present day Pakistan, close to the famous Khyber Pass.

After the war, Agnes McGearey became Deputy Matron of the Cambridge Military Hospital at Aldershot, then continued her military service during the Korean War, before moving on to Malaysia in May 1953, where she took control of the hospital at Taiping in the State of Perak. It was whilst working at Taiping that Agnes began to feel unwell. Sadly, Agnes McGearey died in Oxford on the 9th December 1954, she was suffering from cancer. Here is how the sorrowful news was reported back in Malaysia.

From The Straits Times Newspaper, dated 15th December 1954:

London: Major Agnes McGeary MBE, formerly of the Queen Alexandra's Royal Army Nursing Corps, who was flown home seriously ill from Malaya in August, has died in England. Major McGeary came to Malaya in May 1953 to take charge of the hospital at Taiping.

Shown below is a gallery of images in relation to the nursing career of Agnes McGearey, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Back in 2012, I managed to find on line, a note about an American nurse called Kathy Kelly, who is the great niece of Agnes McGearey. Sadly, the web page cannot be accessed anymore, but it stated:

Kathy Kelly, RN, is a Staff Nurse 3, whose personal experience with diabetic family members resulted in a research project at Kaiser Permanente Medical Centre in Walnut Creek, (California) that found 28.9% of patients undergoing scheduled surgery had the disease but didn't know it.

Staff Nurse Kelly, a post-op surgery nurse for 15 years, says she attended a strategy conference where an endocrinologist presented research on the high number of surgery patients who are unaware that they have diabetes. This inspired Kelly, whose young son, Joe, and both of her parents, have forms of diabetes, to apply for a grant to identify and assist surgery patients with the disease.

Using an innovation grant from Kaiser, Kelly was able to launch a program last year to test the blood glucose of patients both before and after surgical procedures. She states, "My goal is to find patients who unknowingly have diabetes and have them follow through with a primary care physician. Almost 100% of these patients have done the follow-up, which is phenomenal. They're stepping up and taking an active role in their health care."

Kelly says the project is the first of its kind for Kaiser and is being viewed as a best-practice program that may be extended to other Kaiser facilities. She believes her passion for nursing comes from the spirit of her great aunt, Agnes McGearey, who was one of the highest-decorated nurses in England during World War II.

In late 2011, I received an email contact from Mac MacGearey, who was then serving in the British Army. He was also looking for information about his Great Aunt Agnes:

Hello, we are also researching Agnes McGearey. She is my Great Great Aunt. We understand she nursed Wingate and Mountbatten in India and is indeed Godmother to General Wingate's son. I would be genuinely appreciative if we could further discuss her career in nursing and during WW2.

Unfortunately and possibly because of his Army commitments, Mac never replied to my subsequent correspondence. I sincerely hope that both Kathy and Mac eventually come round to reading my article about their Great Aunt on these website pages.

If you would like to listen to a Nurse's memories of working in India and tending to battle casualties from the Burma campaign, please click on the following link: www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80020595

To bring this story to a close, I thought I would use a quote from another of the surviving soldiers from the first Wingate Expedition in 1943. Captain Willy Børge Erik Petersen MC was a Danish soldier fighting in the British Army at the time and was a member of 7 Column on Operation Longcloth. He was wounded on two occasions in Burma and was fortunate to survive an arduous six week march out of the country via the Chinese Borders. The following quotation was taken from a book about Petersen's life called Burma Peter; even in translation, the feeling of warmth shown towards Agnes is clear:

Wingate was so shocked by the high number of casualties in 1943 that he was convinced that he would be tried by court martial. That so many other men survived was due primarily to the excellent care they received at the 19th Casualty Clearing Station, headed by the famous over-nurse, Agnes McGeary. She and her nurses used a mix of affectionate care and strict discipline so successfully that they not only got sick and wounded Chindit soldiers back to life, but also for the most affected men, had instilled in them the will to live on with their disability.

Kathy Kelly, RN, is a Staff Nurse 3, whose personal experience with diabetic family members resulted in a research project at Kaiser Permanente Medical Centre in Walnut Creek, (California) that found 28.9% of patients undergoing scheduled surgery had the disease but didn't know it.

Staff Nurse Kelly, a post-op surgery nurse for 15 years, says she attended a strategy conference where an endocrinologist presented research on the high number of surgery patients who are unaware that they have diabetes. This inspired Kelly, whose young son, Joe, and both of her parents, have forms of diabetes, to apply for a grant to identify and assist surgery patients with the disease.

Using an innovation grant from Kaiser, Kelly was able to launch a program last year to test the blood glucose of patients both before and after surgical procedures. She states, "My goal is to find patients who unknowingly have diabetes and have them follow through with a primary care physician. Almost 100% of these patients have done the follow-up, which is phenomenal. They're stepping up and taking an active role in their health care."

Kelly says the project is the first of its kind for Kaiser and is being viewed as a best-practice program that may be extended to other Kaiser facilities. She believes her passion for nursing comes from the spirit of her great aunt, Agnes McGearey, who was one of the highest-decorated nurses in England during World War II.

In late 2011, I received an email contact from Mac MacGearey, who was then serving in the British Army. He was also looking for information about his Great Aunt Agnes:

Hello, we are also researching Agnes McGearey. She is my Great Great Aunt. We understand she nursed Wingate and Mountbatten in India and is indeed Godmother to General Wingate's son. I would be genuinely appreciative if we could further discuss her career in nursing and during WW2.

Unfortunately and possibly because of his Army commitments, Mac never replied to my subsequent correspondence. I sincerely hope that both Kathy and Mac eventually come round to reading my article about their Great Aunt on these website pages.

If you would like to listen to a Nurse's memories of working in India and tending to battle casualties from the Burma campaign, please click on the following link: www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80020595

To bring this story to a close, I thought I would use a quote from another of the surviving soldiers from the first Wingate Expedition in 1943. Captain Willy Børge Erik Petersen MC was a Danish soldier fighting in the British Army at the time and was a member of 7 Column on Operation Longcloth. He was wounded on two occasions in Burma and was fortunate to survive an arduous six week march out of the country via the Chinese Borders. The following quotation was taken from a book about Petersen's life called Burma Peter; even in translation, the feeling of warmth shown towards Agnes is clear:

Wingate was so shocked by the high number of casualties in 1943 that he was convinced that he would be tried by court martial. That so many other men survived was due primarily to the excellent care they received at the 19th Casualty Clearing Station, headed by the famous over-nurse, Agnes McGeary. She and her nurses used a mix of affectionate care and strict discipline so successfully that they not only got sick and wounded Chindit soldiers back to life, but also for the most affected men, had instilled in them the will to live on with their disability.

Update 06/04/2017.

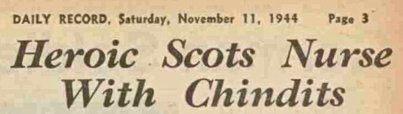

From the pages of the Daily Record newspaper, dated Saturday November 11th 1944 and with the headline:

Heroic Scots Nurse With Chindits

The heroism of a Scots nurse in the Burma jungle, Matron Agnes McGearey, who belongs to Mossend in Lanarkshire was revealed yesterday. Major-General W.D.A. Lentaigne, leader of the Chindits in succession to the late General Orde Wingate, told the story at a Press conference in London. Sickness and disease said the General, were the biggest problem in the jungle. When the rains came I was scared stiff. The flooded ground became nothing but marshes and bogs, and they had to devise new methods for airstrips to get their supplies through. Men would be wringing wet for days on end, with mud and water filtering into their boots. I have seen men with their feet absolutely raw, but they still carried on with marvellous spirit.

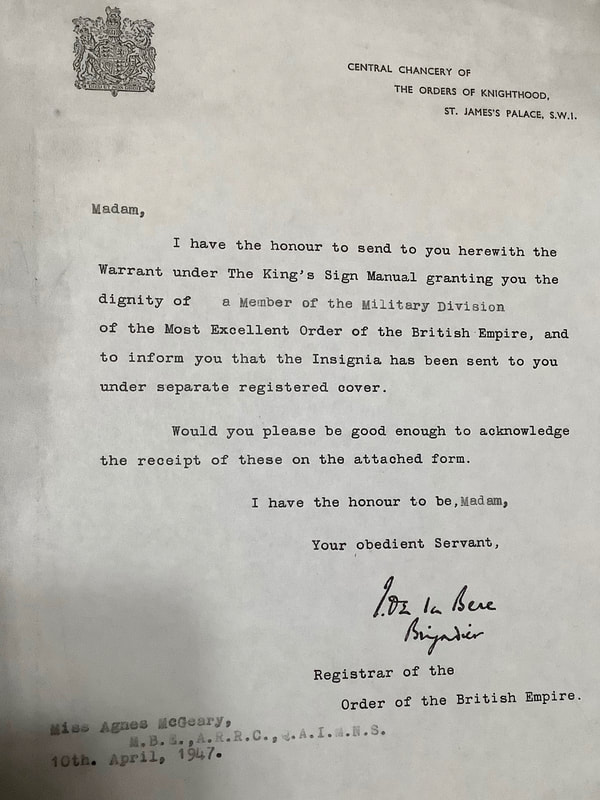

One of the heroines of the troops was Matron McGearey. She had nursed General Wingate the year before and when the wounded came out of the jungle to Imphal, she was there waiting for them. All our men worshiped her. She receives letters from them when they get back to their units and has the biggest fan mail of anyone around. Matron McGearey, who undertook the task of running the hospital at Imphal after a personal request from General Wingate, was last December awarded the MBE for gallant and distinguished services in Burma and on the eastern front of India.

The Daily Record now learns that Matron McGearey's family no longer live in Mossend. Apparently, six years ago they went to England and now reside somewhere in Oxford.

From the pages of the Motherwell Times newspaper, dated 13th August 1948 and with the headline:

Matron Stays Till Last

In charge of the last five Q.A.I.M.N.S. Nursing officers to leave Haifa at the end of the Mandate Period, was the Matron of the British Military Hospital, Miss A. McGearey. On board the hospital ship Oxfordshire, the sisters could relax for the first time for many weeks, free from the sound of bombs, machine gun and mortar fire. Miss McGearey, who live at Thistlebeck, Mossend, has been with the hospital since November 1947, and during that time has had many exciting experiences.

Before coming to Palestine she was in Burma. Her three years in Burma, most of the time with General Wingate's Chindits in the jungle, where all medical supplies were dropped by parachute and the ordinary amenities of civilisation did not exist, will never be forgotten. Interviewed by a Military Observer just before she sailed from Haifa, she remarked: I have enjoyed every minute of it, though it has been a little trying at times.

From the pages of the Daily Record newspaper, dated Saturday November 11th 1944 and with the headline:

Heroic Scots Nurse With Chindits

The heroism of a Scots nurse in the Burma jungle, Matron Agnes McGearey, who belongs to Mossend in Lanarkshire was revealed yesterday. Major-General W.D.A. Lentaigne, leader of the Chindits in succession to the late General Orde Wingate, told the story at a Press conference in London. Sickness and disease said the General, were the biggest problem in the jungle. When the rains came I was scared stiff. The flooded ground became nothing but marshes and bogs, and they had to devise new methods for airstrips to get their supplies through. Men would be wringing wet for days on end, with mud and water filtering into their boots. I have seen men with their feet absolutely raw, but they still carried on with marvellous spirit.

One of the heroines of the troops was Matron McGearey. She had nursed General Wingate the year before and when the wounded came out of the jungle to Imphal, she was there waiting for them. All our men worshiped her. She receives letters from them when they get back to their units and has the biggest fan mail of anyone around. Matron McGearey, who undertook the task of running the hospital at Imphal after a personal request from General Wingate, was last December awarded the MBE for gallant and distinguished services in Burma and on the eastern front of India.

The Daily Record now learns that Matron McGearey's family no longer live in Mossend. Apparently, six years ago they went to England and now reside somewhere in Oxford.

From the pages of the Motherwell Times newspaper, dated 13th August 1948 and with the headline:

Matron Stays Till Last

In charge of the last five Q.A.I.M.N.S. Nursing officers to leave Haifa at the end of the Mandate Period, was the Matron of the British Military Hospital, Miss A. McGearey. On board the hospital ship Oxfordshire, the sisters could relax for the first time for many weeks, free from the sound of bombs, machine gun and mortar fire. Miss McGearey, who live at Thistlebeck, Mossend, has been with the hospital since November 1947, and during that time has had many exciting experiences.

Before coming to Palestine she was in Burma. Her three years in Burma, most of the time with General Wingate's Chindits in the jungle, where all medical supplies were dropped by parachute and the ordinary amenities of civilisation did not exist, will never be forgotten. Interviewed by a Military Observer just before she sailed from Haifa, she remarked: I have enjoyed every minute of it, though it has been a little trying at times.

Nursing Sister Margaret Prout.

Nursing Sister Margaret Prout.

Update 16/12/2017.

From the pages of the Aberdeen Press Journal dated September 14th 1963:

Woman Who Helped Nurse the Chindits Drops in on Burma Veterans

Any doubts about starting an Aberdeen branch of the Burma Star Association were quickly dispelled by an unexpected guest at the Gloucester Hotel last night. She was, Mrs. Margaret Prout of 22 St. Swithin Street, Aberdeen, a former Nursing Sister in the QAIMNS, who had been working in a Colchester Hospital when the remaining Chindits were being flown back to this country.

Mrs. Prout went along to wish the new branch good luck. With her she took her scrap book which contained many messages of thanks from the men of General Wingate's amazing Army.

"They were the most wonderful patients I ever had." Margaret told the gathering. It was emphasised at the meeting that the new branch will include veterans from the whole of the Aberdeenshire area, with the inaugural meeting attended by twenty-five men, plus of course Mrs. Prout. All those who served in the three Services during the Burma Campaign, women as well as men, are warmly invited to join the branch.

Though the appointment of other officials was left for another meeting, Mr. A. Kennedy of Stonehaven was appointed Branch Secretary and Mr. J. McGregor of Jopp's Street, Aberdeen was appointed Welfare Officer. A feature of the organisation is that it will provide emergency help for any Burma veteran who may be in difficulties through no fault of his or her own.

From the pages of the Aberdeen Press Journal dated September 14th 1963:

Woman Who Helped Nurse the Chindits Drops in on Burma Veterans

Any doubts about starting an Aberdeen branch of the Burma Star Association were quickly dispelled by an unexpected guest at the Gloucester Hotel last night. She was, Mrs. Margaret Prout of 22 St. Swithin Street, Aberdeen, a former Nursing Sister in the QAIMNS, who had been working in a Colchester Hospital when the remaining Chindits were being flown back to this country.

Mrs. Prout went along to wish the new branch good luck. With her she took her scrap book which contained many messages of thanks from the men of General Wingate's amazing Army.

"They were the most wonderful patients I ever had." Margaret told the gathering. It was emphasised at the meeting that the new branch will include veterans from the whole of the Aberdeenshire area, with the inaugural meeting attended by twenty-five men, plus of course Mrs. Prout. All those who served in the three Services during the Burma Campaign, women as well as men, are warmly invited to join the branch.

Though the appointment of other officials was left for another meeting, Mr. A. Kennedy of Stonehaven was appointed Branch Secretary and Mr. J. McGregor of Jopp's Street, Aberdeen was appointed Welfare Officer. A feature of the organisation is that it will provide emergency help for any Burma veteran who may be in difficulties through no fault of his or her own.

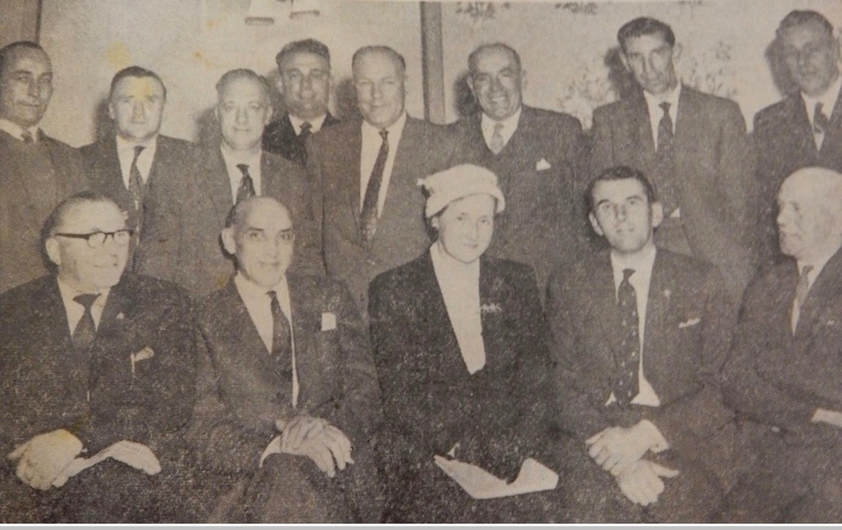

NB. There is no mention of Nursing Sister Prout in the war diary for the 19th Casualty Clearing Station in 1943. It therefore must be presumed that she was involved in tending Chindits at one of the various hospitals throughout India during the second Wingate expedition in 1944. The photograph seen below shows Margaret Prout (centre) with some of the founding members of the Aberdeenshire Branch of the Burma Star Association. Image taken on the 13th September 1963.

Update 17/10/2018.

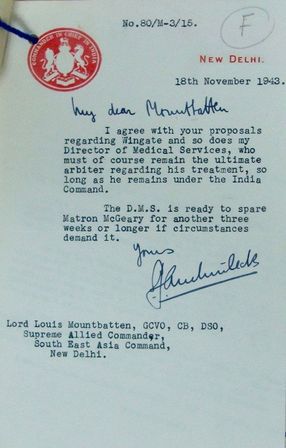

From India Command, dated 18th November 1943.

My Dear Mountbatten,

I agree with your proposals regarding Wingate and so does my Director of Medical Services, who must of course remain the ultimate arbiter regarding his treatment, so long as he remains under India Command.

The DMS is ready to spare Matron McGearey for another three weeks or longer if circumstances demand it.

Signed: General, Sir Claude Auchinleck.

This letter was sent in regards to Major-General Wingate's hospitalisation, having contracted typhoid on his return journey to India after meeting the Allied leadership at the Quebec Conference in August 1943.

In a previous letter dated 15th November 1943, General Auchinleck rather unsympathetically wrote:

My Dear General,

I enclose copies of telegrams which have been exchanged between the Prime Minister's secretary and my own. The Viceroy took me to see Wingate today and we had a talk with Sister McGearey and I also spoke to his doctor, Colonel Cobban, and subject to your agreement, we have all decided on the following programme for him:

On the 17th November, the Viceroy wants him to leave Government House, as he requires his room for the various Governors who will be staying with the Viceroy shortly. Wingate will move to Faridkot House with Sister McGearey until the 22nd November. On this day, three weeks will have passed since his final drop in temperature and in the opinion of Cobban, there will be no more risk of him having a relapse.

He has been invited to stay with friends, the Trevelyans, in the Central Provinces, which is next door to a hospital. Miss McGearey will accompany him. He will not resume full duties until he is quite fit again, which they think will probably be about mid-December.

Yours sincerely

His Excellency, General Sir Claude Auchinleck, Commander-in-Chief, India.

From India Command, dated 18th November 1943.

My Dear Mountbatten,

I agree with your proposals regarding Wingate and so does my Director of Medical Services, who must of course remain the ultimate arbiter regarding his treatment, so long as he remains under India Command.

The DMS is ready to spare Matron McGearey for another three weeks or longer if circumstances demand it.

Signed: General, Sir Claude Auchinleck.

This letter was sent in regards to Major-General Wingate's hospitalisation, having contracted typhoid on his return journey to India after meeting the Allied leadership at the Quebec Conference in August 1943.

In a previous letter dated 15th November 1943, General Auchinleck rather unsympathetically wrote:

My Dear General,

I enclose copies of telegrams which have been exchanged between the Prime Minister's secretary and my own. The Viceroy took me to see Wingate today and we had a talk with Sister McGearey and I also spoke to his doctor, Colonel Cobban, and subject to your agreement, we have all decided on the following programme for him:

On the 17th November, the Viceroy wants him to leave Government House, as he requires his room for the various Governors who will be staying with the Viceroy shortly. Wingate will move to Faridkot House with Sister McGearey until the 22nd November. On this day, three weeks will have passed since his final drop in temperature and in the opinion of Cobban, there will be no more risk of him having a relapse.

He has been invited to stay with friends, the Trevelyans, in the Central Provinces, which is next door to a hospital. Miss McGearey will accompany him. He will not resume full duties until he is quite fit again, which they think will probably be about mid-December.

Yours sincerely

His Excellency, General Sir Claude Auchinleck, Commander-in-Chief, India.

Update 19/01/2019.

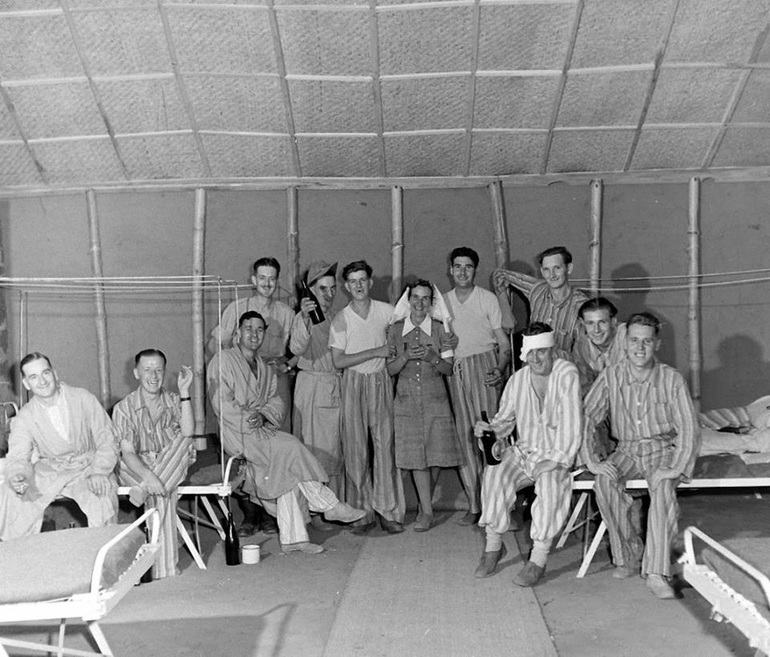

I was delighted recently to be sent some rather hazy still photographs of some Chindit soldiers who survived Operation Longcloth and were treated at the 19th Casualty Clearing Station at Imphal. Amongst the images shown below, there is another wonderful photograph of Agnes McGearey enjoying some fun and games with her Chindit patients. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

I was delighted recently to be sent some rather hazy still photographs of some Chindit soldiers who survived Operation Longcloth and were treated at the 19th Casualty Clearing Station at Imphal. Amongst the images shown below, there is another wonderful photograph of Agnes McGearey enjoying some fun and games with her Chindit patients. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Agnes Kennedy McGearey.

Agnes Kennedy McGearey.

Update 27/03/2021.

Kathy Kelly.

Over the last few years, I have been in contact with the Kathy Kelly, the great niece of Agnes McGearey. In the spring of 2021 Kathy and I shared much of the information we each possessed in relation to the nursing history of her Great Aunt.

Kathy confirmed that Agnes had served at Dunkirk in 1940 and then in Malta, Burma, India and Palestine during WW2, before serving during the Korean War (1950-53) and then in Malaya for a short period before she sadly fell ill with cancer.

From Kathy’s various emails to me over the past few years:

Steve, I was doing a wee search this evening on our Great Aunt Agnes, a Matron during WW2 - and came across the bounty of your research. Surreal and serendipitous is that my quest to really begin researching Agnes was due to start in little while, but I take finding your website as a sign that now is the time.

I’m looking forward to see where all of this will all go. Your research is impeccable and much of it reads just as my mother Agnes Letitia English Henry who was a grand historian, told me when I was growing up! I should tell you that my mother's mother, Annie English Adams (my Scottish Granny) was Agnes’ sister.

I really want to dig deeper into her short but immensely purposeful life. I do know she was one of the last nurses to leave Dunkirk in May 1940. Later in the war, she was on a ship nursing Holocaust survivors. She was the Godmother to General Wingate’s only son, Orde Jonathan, who passed away in 2000 aged just 53.

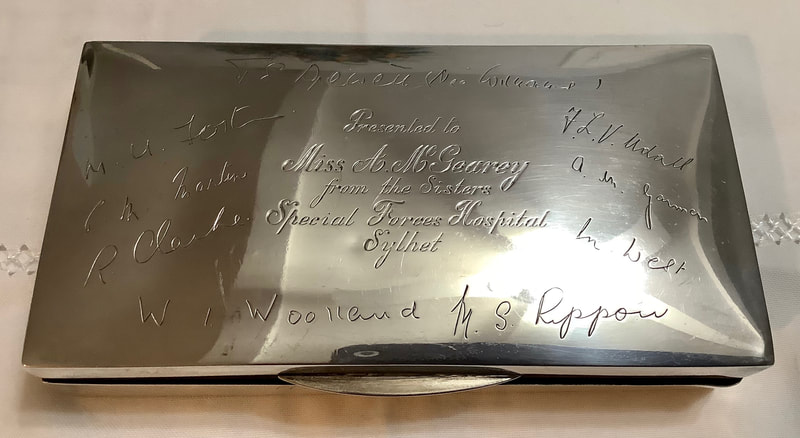

I have her M.B.E. medal at home as well as several others. We have some personal letters and an engraved silver cigarette case presented to her by her fellow nurses in India. My desire to become a nurse many years ago was strong and unwavering. I feel that Great Aunt Agnes has been a loyal spirit guiding me from the start in helping others in anyway I possibly could.

Steve, I have no words to ideally express my heartfelt thanks to you. It’s so much of what you have learned and shared about our Dear Agnes that gives me the motivation and hope that enables me to feel like I know her so much more. The beauty of history are the historians, like you, bringing life to timeless events, individuals and community. Precious moments have transpired over the past weeks because of you and me having someone to share her treasures and story’s with. I feel an even deeper connection to Agnes now and that is down to your help in bringing her story to life. I send you an unwavering thank you, Kathy.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the life of Agnes McGearey as sent to me by Kathy. These include photographs of her medal entitlement and an image of the silver cigarette case presented to Agnes by her nursing colleagues at Sylhet in India. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Kathy Kelly.

Over the last few years, I have been in contact with the Kathy Kelly, the great niece of Agnes McGearey. In the spring of 2021 Kathy and I shared much of the information we each possessed in relation to the nursing history of her Great Aunt.

Kathy confirmed that Agnes had served at Dunkirk in 1940 and then in Malta, Burma, India and Palestine during WW2, before serving during the Korean War (1950-53) and then in Malaya for a short period before she sadly fell ill with cancer.

From Kathy’s various emails to me over the past few years:

Steve, I was doing a wee search this evening on our Great Aunt Agnes, a Matron during WW2 - and came across the bounty of your research. Surreal and serendipitous is that my quest to really begin researching Agnes was due to start in little while, but I take finding your website as a sign that now is the time.

I’m looking forward to see where all of this will all go. Your research is impeccable and much of it reads just as my mother Agnes Letitia English Henry who was a grand historian, told me when I was growing up! I should tell you that my mother's mother, Annie English Adams (my Scottish Granny) was Agnes’ sister.

I really want to dig deeper into her short but immensely purposeful life. I do know she was one of the last nurses to leave Dunkirk in May 1940. Later in the war, she was on a ship nursing Holocaust survivors. She was the Godmother to General Wingate’s only son, Orde Jonathan, who passed away in 2000 aged just 53.

I have her M.B.E. medal at home as well as several others. We have some personal letters and an engraved silver cigarette case presented to her by her fellow nurses in India. My desire to become a nurse many years ago was strong and unwavering. I feel that Great Aunt Agnes has been a loyal spirit guiding me from the start in helping others in anyway I possibly could.

Steve, I have no words to ideally express my heartfelt thanks to you. It’s so much of what you have learned and shared about our Dear Agnes that gives me the motivation and hope that enables me to feel like I know her so much more. The beauty of history are the historians, like you, bringing life to timeless events, individuals and community. Precious moments have transpired over the past weeks because of you and me having someone to share her treasures and story’s with. I feel an even deeper connection to Agnes now and that is down to your help in bringing her story to life. I send you an unwavering thank you, Kathy.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the life of Agnes McGearey as sent to me by Kathy. These include photographs of her medal entitlement and an image of the silver cigarette case presented to Agnes by her nursing colleagues at Sylhet in India. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Agnes McGearey lived at 2 Bulan Road in Headington, an eastern suburb of Oxford after returning home from Malaya in 1953. She died aged 45, on the 9th December 1954 in Oxford and is buried at Rose Hill Cemetery located less than 2 miles from the above address.

Epitaph for Agnes

Another of the items sent to me by Kathy recently, was a short personal message written by one of Agnes' former colleagues, whose identity is sadly unknown. I thought that this heartfelt commemoration might be a fitting way to end this rather special update:

I learnt from people who looked after Agnes, that her courage and fortitude shown throughout her illness was an inspiration to them and filled them all with the greatest admiration, which she rightly deserved.

Aggie had a keen sense of humour and many are the the laughs we have had together. She was a wonderful companion and friend and loved beautiful things; books, art, paintings and music. Her verbal descriptions of places she had seen, operas she had been to, art galleries she had visited, were so vivid one almost felt these joys had been shared with her.

I am sure there are many who will be paying tributes to her, and I feel mine are very inadequate, but as I have lost a dear friend I would like to add them. There are many who will feel the same, and in her passing the Corps has lost a most vital member. Whilst tributes are sad, and I know they must be, I felt proud to read the obituary notice in the The Times, written by someone who admired her life and work as much as many of us have done.

Epitaph for Agnes

Another of the items sent to me by Kathy recently, was a short personal message written by one of Agnes' former colleagues, whose identity is sadly unknown. I thought that this heartfelt commemoration might be a fitting way to end this rather special update:

I learnt from people who looked after Agnes, that her courage and fortitude shown throughout her illness was an inspiration to them and filled them all with the greatest admiration, which she rightly deserved.

Aggie had a keen sense of humour and many are the the laughs we have had together. She was a wonderful companion and friend and loved beautiful things; books, art, paintings and music. Her verbal descriptions of places she had seen, operas she had been to, art galleries she had visited, were so vivid one almost felt these joys had been shared with her.

I am sure there are many who will be paying tributes to her, and I feel mine are very inadequate, but as I have lost a dear friend I would like to add them. There are many who will feel the same, and in her passing the Corps has lost a most vital member. Whilst tributes are sad, and I know they must be, I felt proud to read the obituary notice in the The Times, written by someone who admired her life and work as much as many of us have done.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, July 2016.