Petersen, the Fighting Dane

Major Willy Børge Erik Petersen.

Major Willy Børge Erik Petersen.

"Willy Børge Erik Petersen, with his drooping wheat-coloured moustache and cornflower blue eyes, looks like a story book picture of a Dane. Like the Vikings of old he's a dour fighter and "Fighting Dane" inscribed in red letters on his shoulders describes him well.

He left his village near Copenhagen when he was 25 and went to Malaya, to manage a rubber plantation in Johore. With his naive smile and his pleasant slow speech, he was quickly popular with the rest of the planters. He joined the Malayan Volunteer Forces three days after he arrived.

In May 1940 the Germans invaded Denmark. The next day Petersen enlisted in the regular British Army. He hoped to get back to fight the Germans in Europe, but he was kept in Malaya. Three days before the Japs attacked Singapore he was sent to Burma to join the Scandinavian Commando School training at Lashio under the red-bearded Swedish giant, George Saudebaum. Two months later he went up the Burma Road into China and continued training at Kweiyang and Kunming.

Petersen began to think the war would be over before he had a chance to fire a shot, or blow a demolition charge. Little did he know how wrong he was to be."

This is a quote from Wilfred Burchett's book, 'Wingate's Phantom Army' and I think aptly describes the almost legendary Captain W.B.E. Petersen of Chindit fame in 1943.

Much has been written about this man and his exploits on Operation Longcloth, in fact there is no book or diary I have read that does not mention him. Petersen, there can be no doubt, is one of the true characters from Operation Longcloth and were there ever to be a feature film portraying Wingate's first expedition, his part would be much sort after by Hollywood's leading actors.

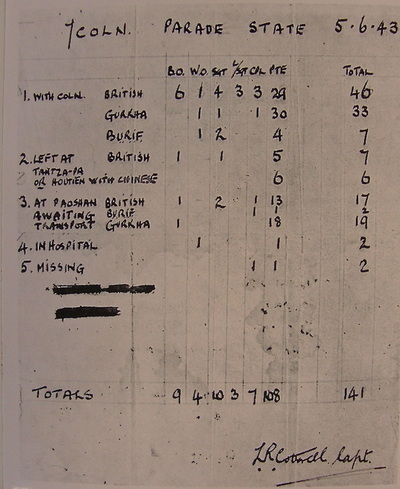

Captain Petersen was attached to Column 7 in 1943, under the overall command of Major Ken Gilkes the Dane took leadership of Platoon 15 and was often at the forefront of any actions against the Japanese. But, let us not get too far ahead with this story.

In 1998, Danish author Knud Rasmussen published the book, 'Burma Peter' his account of the life of Erik Petersen. The book is written of course in the Danish language and no English translation exists, but thanks to a contact of mine who translated it for me and who also made contact with the author on my behalf, I am able to use the book as the basis for this article.

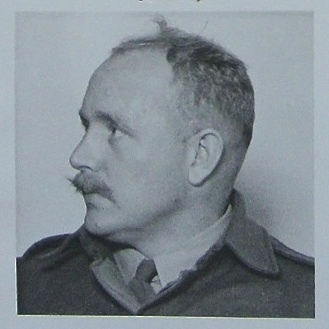

Knud Rasmussen first met Petersen in 1950, when the author himself was a serving NCO in the Danish Forces. This is how he remembered Major Petersen from those times:

"The Major made a good impression on us young NCO’s. We looked up to him not only because of his many medals from his active war service in the Far East, where he fought under the legendary General Orde Wingate in his famous “Ghost Army”, but first and foremost because of Major Petersen's fine human qualities.

His kindness and helpfulness towards those he commanded was greatly appreciated by all. But one should not be mistaken and think he belonged to those officers who who adorned themselves with the popularity hunter "grey jacket". He was able to keep a proper distance from his surroundings when he found it necessary, however, when this is said, the following three words some up his character most appropriately: modesty, humor and heartwarming."

Of the medals mentioned, one was the British Military Cross, awarded to Petersen for his actions on Operation Longcloth with the men from Platoon 15. He received his award from King George no less, at a ceremony held at Buckingham Palace.

Here is the citation for his award:

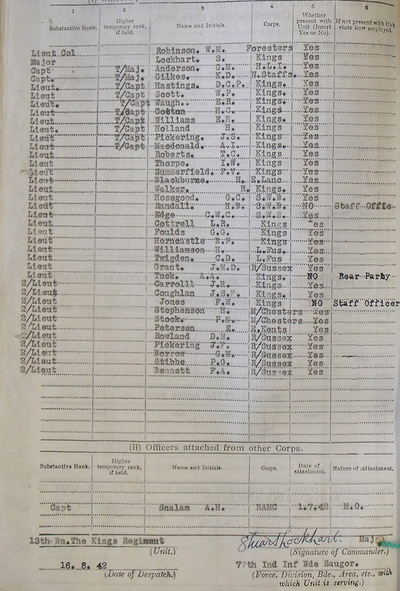

Brigade- 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

Recipients Unit- The Buffs (Royal East Kent Regiment) attached 13th Bn. The King's Regiment.

Lieutenant (temporary Captain) Willy Børge Erik Petersen (Free Dane).

Regimental No.- 221724

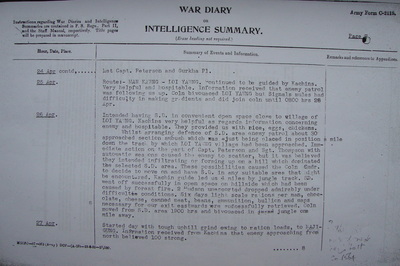

Action for which recommended :- OPERATIONS IN BURMA - MARCH 1943

On 6th March 1943, Captain Petersen was in command of two British Infantry Platoons which were returning from an independent mission. On the way towards their column they met a detachment of a Gurkha Column which was about to attack a village named Nankan. Although Captain Petersen's men had been without food for three days and were extremely weary, he immediately placed himself and his detachment under the command of Major Calvert, the Gurkha Column Commander, who allotted him a role in the attack. In the course of the fighting, having surprised the enemy on his front, he captured his objective and beat off the subsequent counter-attack, inflicting heavy casualties on the enemy and destroying valuable motor transport, without loss to himself. The vigour and dash displayed by his tired and hungry troops in this spirited action was largely due to Captain Petersen's own example. Subsequently, marching to rejoin his own column, he met and attacked an enemy patrol and again inflicted casualties.

On 24th March at Baw, this officer again played a leading part in the protection of a vital area against enemy attack, although seriously wounded in the head. The devotion and affection which he had inspired in all ranks was demonstrated by the attention with which they now cared for him. Unable to sit on his horse without help, he was supported in the saddle by relays of men for a march of several hundred miles, until he was sufficiently recovered once more to walk and fight, and ultimately to reach CHINA.

Recommended By- Brigadier O.C. Wingate, DSO.

Commander 77th Indian Infantry Brigade Group

Honour or Reward- Military Cross (Immediate)

Signed By-Brigadier O.C. Wingate-Commander 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

General Auchinleck-Commander-in-Chief India

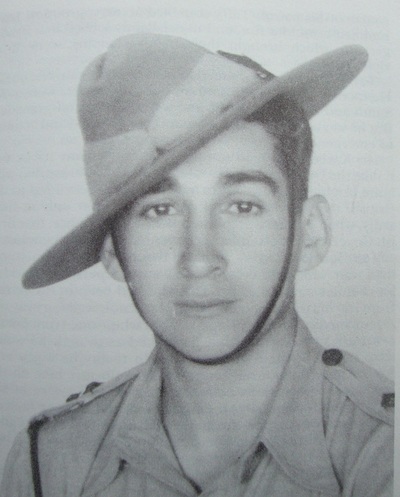

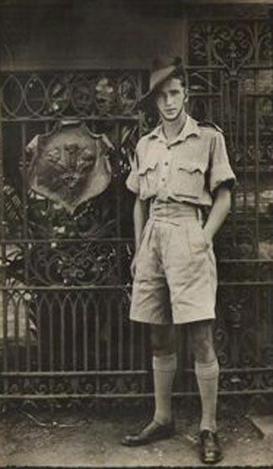

A young Petersen in 1933.

A young Petersen in 1933.

Erik Petersen was born on the 18th December 1912 in Sakskoebing, Denmark. He was the son of John Carl and Marie Petersen, his father being a practising pharmacist and later a business man manufacturing soap and mineral water.

Young Erik did well at school and it was always hoped that he would eventually help run his father's business, but a strong sense of 'wanderlust' would make this impossible to achieve. He attended Agricultural School in 1934 and looked forward to a career in farming. Erik had always enjoyed the outdoor life and was never happier than when out riding on horseback.

Everything he set his mind to he usually excelled at and this included his first few positions in the agricultural industry. Erik had been called up to perform his National Service in the summer of 1933, he was posted to the 10th Battalion of the 7th Danish Regiment, where he proved to be an enthusiastic and talented soldier.

Aged 25, he trained as an officer in the Coastal Defence Reserve, passing out as 'Coastal Lieutenant, Second Class' in October 1937. In December that year a dream came true for the young farmer, when he was hired as an Assistant Planter by the East Asiatic Company and sailed aboard the MS. Lalandia for Singapore.

He was to take up a position at the Mount Austin Rubber Estate in Johore State, Malaya. The plantation was approximately 12,000 acres and was divided into six sections, each of which was managed by a Danish planter. It employed about 400 workers per section, comprising of mainly Indians and Javanese. Petersen was helped greatly by his mentor at Johore, Henry Clausen and after his apprenticeship was over took on his own section of the plantation.

Almost immediately on arrival in Malaya, he joined the British Territorial Army in the form of the Johore Volunteer Engineers or J.V.E. His previous military experiences were well recognised and he became an important part of the unit and the European community in general.

There was much socializing in the European colony, and it was during this time that he first met Ethel Wilkinson Lamont. She was the daughter of Doctor George Francis McCutcheon Lamont from Newark, New Jersey in the USA. They became engaged and were married in Singapore on the 2nd September 1939. After war had broken out, it was decided that Ethel and their newly born daughter, Ingelise, would be safer travelling back home to the United States and this was achieved only a few short weeks before Singapore fell to the Japanese.

Petersen offered up his service to the Allied cause, hoping to travel back to Europe and help his own countries fight against Nazi Germany. This was not to be. Petersen was recruited by a man named Hans Tofte and posted to the Chinese Oriental Mission, a special forces organisation working with Chang-Kai-Shek and his Chinese guerillas. Erik was a little disappointed not to be going home to fight the Germans until he received this notification from Tofte:

"The Danish Recruiting Officer, Captain Iversen, lets W. B. E. Petersen know that his services will be just as valuable to the Free Danes in the East as they would elsewhere".

Petersen went to the special forces school in Malaya and was taught by such men as Major Spencer Chapman. He passed out with flying colours in December 1941, just a few days before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Young Erik did well at school and it was always hoped that he would eventually help run his father's business, but a strong sense of 'wanderlust' would make this impossible to achieve. He attended Agricultural School in 1934 and looked forward to a career in farming. Erik had always enjoyed the outdoor life and was never happier than when out riding on horseback.

Everything he set his mind to he usually excelled at and this included his first few positions in the agricultural industry. Erik had been called up to perform his National Service in the summer of 1933, he was posted to the 10th Battalion of the 7th Danish Regiment, where he proved to be an enthusiastic and talented soldier.

Aged 25, he trained as an officer in the Coastal Defence Reserve, passing out as 'Coastal Lieutenant, Second Class' in October 1937. In December that year a dream came true for the young farmer, when he was hired as an Assistant Planter by the East Asiatic Company and sailed aboard the MS. Lalandia for Singapore.

He was to take up a position at the Mount Austin Rubber Estate in Johore State, Malaya. The plantation was approximately 12,000 acres and was divided into six sections, each of which was managed by a Danish planter. It employed about 400 workers per section, comprising of mainly Indians and Javanese. Petersen was helped greatly by his mentor at Johore, Henry Clausen and after his apprenticeship was over took on his own section of the plantation.

Almost immediately on arrival in Malaya, he joined the British Territorial Army in the form of the Johore Volunteer Engineers or J.V.E. His previous military experiences were well recognised and he became an important part of the unit and the European community in general.

There was much socializing in the European colony, and it was during this time that he first met Ethel Wilkinson Lamont. She was the daughter of Doctor George Francis McCutcheon Lamont from Newark, New Jersey in the USA. They became engaged and were married in Singapore on the 2nd September 1939. After war had broken out, it was decided that Ethel and their newly born daughter, Ingelise, would be safer travelling back home to the United States and this was achieved only a few short weeks before Singapore fell to the Japanese.

Petersen offered up his service to the Allied cause, hoping to travel back to Europe and help his own countries fight against Nazi Germany. This was not to be. Petersen was recruited by a man named Hans Tofte and posted to the Chinese Oriental Mission, a special forces organisation working with Chang-Kai-Shek and his Chinese guerillas. Erik was a little disappointed not to be going home to fight the Germans until he received this notification from Tofte:

"The Danish Recruiting Officer, Captain Iversen, lets W. B. E. Petersen know that his services will be just as valuable to the Free Danes in the East as they would elsewhere".

Petersen went to the special forces school in Malaya and was taught by such men as Major Spencer Chapman. He passed out with flying colours in December 1941, just a few days before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

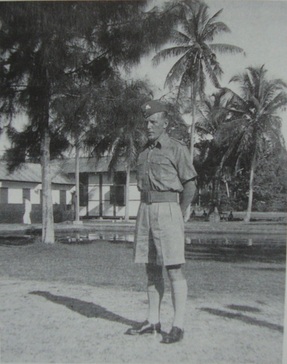

Petersen in 1939 as a Johore Volunteer Reservist.

Petersen in 1939 as a Johore Volunteer Reservist.

Erik Petersen travelled at first to Rangoon, but before long was at the Bush Warfare School at Lashio close to the Chinese borders. It was here that Erik worked with men such as William Hatton and the Swede, George Söderbom.

His first command was a platoon of Gurkha Rifles, leading them in Commando training, but it was not long before Erik found himself working with the famous A.V.G. or 'Flying Tigers', an American Volunteer unit of pilots serving Chang-Kai-Shek under the command of General Claire Chennault.

Later, whilst working in Chungking, Petersen received his commission into the Buffs Regiment (Royal East Kents), where he was immediately promoted to full Lieutenant. The regiment had maintained a strong link with the Danes as it was once named the Prince George of Denmark Regiment back in 1708. Most, if not all Danish soldiers were attached to the regiment during their service in WW2.

In April 1942, Chang-Kai-Shek ordered the 'Oriental Mission' to leave China and Erik made his way to India via Kunming. He asked to be attached to a British Infantry battalion on the Burmese border, but instead was posted to the 13th King's Liverpool (another British Regiment with strong ties to Denmark) at Secunderabad. It was at this time that he became known as 'Erik', especially by Major Gilkes and the officers of B Company where he became a platoon leader.

One month after arriving at Secunderabad the battalion was moved up to Saugor in the Central Provinces of India and began their Chindit training. Petersen was promoted to Captain and was instrumental in teaching his men about jungle tactics and how to be self-reliant in this environment. Major Gilkes recognising his worth made him deputy tactical commander of the newly formed Chindit Column 7.

By Christmas 1942 the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade was preparing to move down to Imphal and make the final arrangements for their entry into Burma. At one point it looked as though the operation would be cancelled, as other parts of the plan, including commitments from Chang-Kai-Shek fell through. However, Wingate persuaded General Wavell that Longcloth should still go ahead as planned. He (Wingate) desperately wanted to test his own theories of long range penetration and felt that the men were at their peak and would never be able to reach this state of readiness again.

Column 7 were paired with Major Scott's Column 8 for most of the time that these units were operating in Burma, they also shadowed Brigadier Wingate's Brigade HQ on many occasions. Petersen and his platoon crossed over the Chindwin River at a place called Tonhe on the 17th/18th February, it took over 24 hours for the men of Northern Section to achieve the crossing, but fortunately there were no Japanese in sight.

After several days march this large group of Chindits including Column 7 took its first supply drop at a village called Tonmakeng. The air drop was a complete success and the spirit amongst the men was high. Not long afterwards Petersen was asked to command a force from Column 7 and try and intercept a Japanese unit at a place called Sinlamaung.

He remembered:

"When we left Tonmakeng I was ordered with two light platoons and a Pioneer group to be the rear guard of the Brigade, which started to march towards the town of Pinlebu. We were hoping to lure the enemy into an ambush when he came out of his garrison approximately 30 km from where we were. I was ordered to establish a road block in a suitable place to prevent the enemy force escaping when our troops attacked Pinlebu.

I was supposed to meet the Brigade the next day in the jungle in a place that I got shown on the map. According to the map a larger path crossed a river here, so the site should be easy to find. The Pioneer Squad prepared the roadblock, and I put my three platoons in appropriate positions in the terrain around it. We waited all night, for something to happen. We heard quite a violent fusillade from Pinlebu, but nothing happened in our area. Next morning we saw what we thought was a Japanese patrol far away in a field, but the patrol was out of range.

I had orders to withdraw the road block in the middle of the next morning, which I did and we marched along the said path. After some time the path disappeared, having become completely overgrown by jungle, this caused us to miss the agreed rendezvous with brigade."

Erik's group was now adrift from Northern Section, he informed his men that they would continue marching in the general direction of the brigade which was due east. For reasons of morale he named the new sub-unit, 'Victory Force'. They marched for several days, all the while eating into their precious rations and having no possible way of calling for more to be sent to them by air. Petersen was worried, but tried hard not to show his concern openly to his men.

As they passed through Burmese villages they often received news of the other columns activities, it seemed likely to them that they would sooner or later bump into another group of Chindits and this proved to be correct as they approached the railway line near Nankan. In the near distance the sound of the demolitons could clearly be heard, this was the work of Mike Calvert's Column 3 as they set about destroying the railway and bridge at Nankan.

It was the 6th March and whilst the men of 142 Commando were setting their explosives at the railway, a large Japanese patrol were approaching the town from one of the roads leading up to the rail station. Calvert and some of his Gurkhas had set a roadblock and waited for the first of the enemy trucks to arrive. A fierce firefight ensued, with the Gurkhas doing their commander proud.

Calvert recalled:

”At that moment, Captain Petersen, a flamboyant Dane with a grudge against the Japanese, arrived unexpectedly near the station and went straight into action”.

Although this was the platoon's first taste of action, they performed well, using all Petersen's pre-arranged assault tactics. The Japanese suffered significant losses, whilst British casualties were few. Petersen and his second in command, Lieutenant Pearce were well satisfied with their days work.

That evening Major Calvert was happy to feed the men from Column 7 and then radioed HQ Brigade to inform them of Captain Petersen's present location. Wingate ordered Petersen back to re-join Northern Section who were some 70km at that time. It took 'Victory Force' another three days to finally catch up with Northern Section, by which time the men were again running dangerously low on food and fresh water.

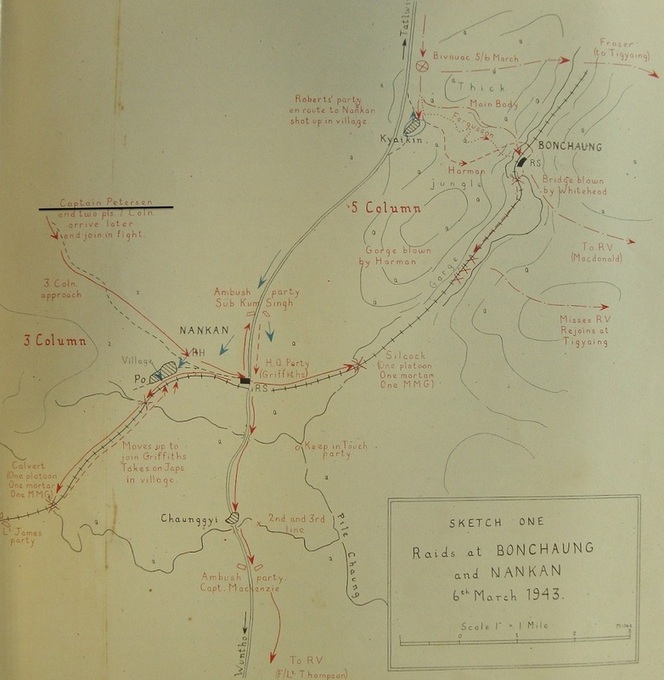

Below is a sketch map of Bonchaung and Nankan railway stations. These were the two towns pinpointed for attack by Column 5 and Column 3 respectively on the 6th March 1943. Please click on the image to bring it forward.

His first command was a platoon of Gurkha Rifles, leading them in Commando training, but it was not long before Erik found himself working with the famous A.V.G. or 'Flying Tigers', an American Volunteer unit of pilots serving Chang-Kai-Shek under the command of General Claire Chennault.

Later, whilst working in Chungking, Petersen received his commission into the Buffs Regiment (Royal East Kents), where he was immediately promoted to full Lieutenant. The regiment had maintained a strong link with the Danes as it was once named the Prince George of Denmark Regiment back in 1708. Most, if not all Danish soldiers were attached to the regiment during their service in WW2.

In April 1942, Chang-Kai-Shek ordered the 'Oriental Mission' to leave China and Erik made his way to India via Kunming. He asked to be attached to a British Infantry battalion on the Burmese border, but instead was posted to the 13th King's Liverpool (another British Regiment with strong ties to Denmark) at Secunderabad. It was at this time that he became known as 'Erik', especially by Major Gilkes and the officers of B Company where he became a platoon leader.

One month after arriving at Secunderabad the battalion was moved up to Saugor in the Central Provinces of India and began their Chindit training. Petersen was promoted to Captain and was instrumental in teaching his men about jungle tactics and how to be self-reliant in this environment. Major Gilkes recognising his worth made him deputy tactical commander of the newly formed Chindit Column 7.

By Christmas 1942 the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade was preparing to move down to Imphal and make the final arrangements for their entry into Burma. At one point it looked as though the operation would be cancelled, as other parts of the plan, including commitments from Chang-Kai-Shek fell through. However, Wingate persuaded General Wavell that Longcloth should still go ahead as planned. He (Wingate) desperately wanted to test his own theories of long range penetration and felt that the men were at their peak and would never be able to reach this state of readiness again.

Column 7 were paired with Major Scott's Column 8 for most of the time that these units were operating in Burma, they also shadowed Brigadier Wingate's Brigade HQ on many occasions. Petersen and his platoon crossed over the Chindwin River at a place called Tonhe on the 17th/18th February, it took over 24 hours for the men of Northern Section to achieve the crossing, but fortunately there were no Japanese in sight.

After several days march this large group of Chindits including Column 7 took its first supply drop at a village called Tonmakeng. The air drop was a complete success and the spirit amongst the men was high. Not long afterwards Petersen was asked to command a force from Column 7 and try and intercept a Japanese unit at a place called Sinlamaung.

He remembered:

"When we left Tonmakeng I was ordered with two light platoons and a Pioneer group to be the rear guard of the Brigade, which started to march towards the town of Pinlebu. We were hoping to lure the enemy into an ambush when he came out of his garrison approximately 30 km from where we were. I was ordered to establish a road block in a suitable place to prevent the enemy force escaping when our troops attacked Pinlebu.

I was supposed to meet the Brigade the next day in the jungle in a place that I got shown on the map. According to the map a larger path crossed a river here, so the site should be easy to find. The Pioneer Squad prepared the roadblock, and I put my three platoons in appropriate positions in the terrain around it. We waited all night, for something to happen. We heard quite a violent fusillade from Pinlebu, but nothing happened in our area. Next morning we saw what we thought was a Japanese patrol far away in a field, but the patrol was out of range.

I had orders to withdraw the road block in the middle of the next morning, which I did and we marched along the said path. After some time the path disappeared, having become completely overgrown by jungle, this caused us to miss the agreed rendezvous with brigade."

Erik's group was now adrift from Northern Section, he informed his men that they would continue marching in the general direction of the brigade which was due east. For reasons of morale he named the new sub-unit, 'Victory Force'. They marched for several days, all the while eating into their precious rations and having no possible way of calling for more to be sent to them by air. Petersen was worried, but tried hard not to show his concern openly to his men.

As they passed through Burmese villages they often received news of the other columns activities, it seemed likely to them that they would sooner or later bump into another group of Chindits and this proved to be correct as they approached the railway line near Nankan. In the near distance the sound of the demolitons could clearly be heard, this was the work of Mike Calvert's Column 3 as they set about destroying the railway and bridge at Nankan.

It was the 6th March and whilst the men of 142 Commando were setting their explosives at the railway, a large Japanese patrol were approaching the town from one of the roads leading up to the rail station. Calvert and some of his Gurkhas had set a roadblock and waited for the first of the enemy trucks to arrive. A fierce firefight ensued, with the Gurkhas doing their commander proud.

Calvert recalled:

”At that moment, Captain Petersen, a flamboyant Dane with a grudge against the Japanese, arrived unexpectedly near the station and went straight into action”.

Although this was the platoon's first taste of action, they performed well, using all Petersen's pre-arranged assault tactics. The Japanese suffered significant losses, whilst British casualties were few. Petersen and his second in command, Lieutenant Pearce were well satisfied with their days work.

That evening Major Calvert was happy to feed the men from Column 7 and then radioed HQ Brigade to inform them of Captain Petersen's present location. Wingate ordered Petersen back to re-join Northern Section who were some 70km at that time. It took 'Victory Force' another three days to finally catch up with Northern Section, by which time the men were again running dangerously low on food and fresh water.

Below is a sketch map of Bonchaung and Nankan railway stations. These were the two towns pinpointed for attack by Column 5 and Column 3 respectively on the 6th March 1943. Please click on the image to bring it forward.

Someone else who met Captain Petersen that day at Nankan was the young Gurkha Subaltern, Harold James. From his book, 'Across the Threshold of Battle', he recalls:

"My platoon and Calvert hurried back towards the station, the sound of firing growing louder as we approached. Suddenly, as we reached the path which we had used earlier from our bivouac, I looked up and stared into a bearded face. There was a brief pause as I tried to adjust my mind to this unexpected appearance, then the man said quickly and anxiously in a Scandanavian accent, 'Don't shoot! Longcloth! Longcloth!' Behind him I could see a long line of more figures, all with beards. 'I believe it is Petersen,' said Calvert.

It was Captain Erik Petersen and two platoons who had been separated from 7 Column and had been following our tracks in the hope of catching us up. 'You're just in time for a bit of action, if you wish,' said Calvert, never one to lose an opportunity. 'Sounds as though that village is full of Japs.'

'I think we would like that,' said the Dane, also a man always ready for a fight. And there was a murmur of agreement back down the line from his men.

They tagged on behind us, and now, as we neared the station and village, bullets whined high overhead. But most of the rattle of fire was in the village where Taffy Griffiths and Kumba Sing were gradually extricating themselves from their tricky position. We came by the ruins of the old station and took up positions along the railway line to open fire into the village. The Japs were caught by surprise and suffered heavy punishment before switching their attack onto us, but much of their fire went wide.

An armoured car appeared out of the trees, accompanied by infantry, but retreated hastily in the face of a fierce attack launched by Petersen and his King's platoons. Not to be outdone, Calvert, as delighted as a schoolboy, said, 'We'll give them a taste of mortar.' The Gurkha Support Group's 3-inch mortar coughed and there was a flash of flame, an explosion and a fountain of earth.

'Up fifty,' I suggested.

'I think you're right,' Calvert agreed."

After settling back down in Column 7 Petersen was often given the task of covering the outer perimeter during supply drops. Wingate and Gilkes had been impressed by the Danes abilities, especially keeping his group together during the days of separation leading up to the engagement at Nankan. At the Brigade's outward crossing of the Irrawaddy River, Petersen was once again chosen to be first over and to form a protective bridgehead on the eastern banks as protection against any enemy interference. The Chindits assembled on the banks of the 1000m wide river just south of Katha, by the 18th March they were all over and Captain Petersen closed his defensive position.

Many commentators have professed that Wingate made a very large error of judgement by taking his men across to the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy. To his credit, Brigadier Wingate also expressed this view (with hindsight) in his debrief for Operation Longcloth later in 1943. The Brigadier had hoped to gain the support of the local Kachin tribes in the area east of the river, who could protect and assist his Chindits as they continued to harass the Japanese, before they eventually marched out of Burma through the Chinese border provinces.

Once over the Irrawaddy, the Chindits found themselves in fairly dry and waterless country, they were also in a natural 'bag', contained on three sides by the rivers Irrawaddy and Shweli and to their south the Mongmit-Myitson Road, which the Japanese used as their main method of transportation and communication in that area. The men were effectively hemmed in from all sides.

On the 22nd of March Wingate called the various columns in to bivouac on a hillside to the west of a village called Baw. It was decided to call rear base and order the largest supply drop yet. A plan was laid down to secure the local paths and tracks against enemy interference, especially the road to the east of the village which led to the town of Mabein, where the Japanese had a large garrison.

Wingate gave the task of securing the Mabien Road to Captain Coughlan of Column 8, whilst platoons from Column 7 including Petersen's were placed to secure the drop zone area. Unfortunately, having to move through more dense jungle than anticipated, Coughlan's party failed to secure the road before morning and stumbled into a Japanese patrol. The enemy opened fire on the ailing platoon and they were forced back to the north.

Petersen and Gilkes men soon came under enemy fire themselves and the supply drop zone seemed compromised and would surely have to be abandoned. Captain Petersen drove his men forward and cleared the Japanese from his sector, he then saw Captain Coughlan who had been slightly wounded. Coughlan explained that his platoon were tied down by strong enemy fire and could not disengage from the area without suffering heavy casualties. Petersen decided on a plan of attack which he relayed to Coughlan, who then went back to his men.

Petersen used his mortar section to cover his advance and employed a flanking manoeuvre led by Lieutenant Jelliss on the Japanese positions, he had his Bren gun team concentrate on the tree tops where enemy snipers were positioned, eventually Captain Coughlan's platoon managed to escape their predicament and came through Petersen's position to safety. To read more about Captain Coughlan's Platoon and their involvement at Baw, please follow the link below:

Arthur Birch and Platoon 17

Lieutenant-Colonel Cooke, the senior officer in Northern Group and Major Gilkes then approached Petersen and told him that the enemy must be thrown out of Baw so that the supply drop could take place. Petersen told them that a much larger force than the one he commanded would be required to achieve this aim. Major Scott was given orders to assist Petersen and the two groups moved in to position. The men from Column 8 attacked the eastern flank of the enemy whilst Petersen and his men moved head on against the Japanese.

The Chindits fought bravely and after some fierce and bitter battles, drove the Japanese out of the area. Scott and his men had performed valiantly, but had suffered heavy casualties. Lieutenant Pearce and Sergeant Lamb from Petersen's Platoon had done excellent work with their respective Bren guns and grenade launchers.

Towards the end of the engagement Captain Petersen was seriously wounded, he had been shot in the head by a Japanese sniper. He had managed to stem the flow of blood with a field dressing, but then fell unconscious onto the ground. Lieutenant Dennis Russell Chambers of Column 7 was sadly killed during the action at Baw that day. Chambers was commander of Petersen's Reserve Platoon and was out on a recce patrol shortly before the final assault on the enemy. As he stood watching the Japanese positions, he too was shot by an enemy sniper and was killed instantly.

Lieutenant Chambers, originally from Durban, South Africa, had been commissioned into the 3rd Gurkha Rifles in India in late 1942, previously during the war he had fought in the Allied rearguard action on the island of Crete. For more details about Dennis Chambers, please follow the link below to view his CWGC details:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2506861/CHAMBERS,%20DENNIS%20RUSSELL

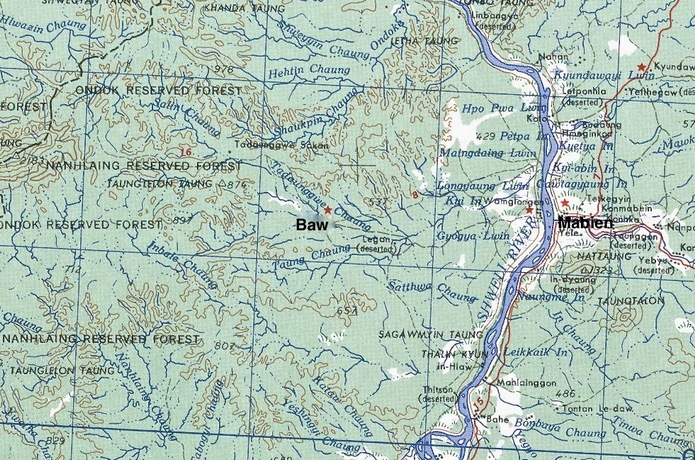

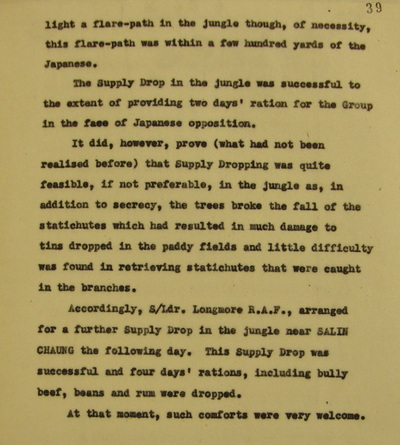

Seen below is a map of the area around the village of Baw, showing the general terrain and the Japanese garrison town of Mabien on the banks of the Shweli River. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

"My platoon and Calvert hurried back towards the station, the sound of firing growing louder as we approached. Suddenly, as we reached the path which we had used earlier from our bivouac, I looked up and stared into a bearded face. There was a brief pause as I tried to adjust my mind to this unexpected appearance, then the man said quickly and anxiously in a Scandanavian accent, 'Don't shoot! Longcloth! Longcloth!' Behind him I could see a long line of more figures, all with beards. 'I believe it is Petersen,' said Calvert.

It was Captain Erik Petersen and two platoons who had been separated from 7 Column and had been following our tracks in the hope of catching us up. 'You're just in time for a bit of action, if you wish,' said Calvert, never one to lose an opportunity. 'Sounds as though that village is full of Japs.'

'I think we would like that,' said the Dane, also a man always ready for a fight. And there was a murmur of agreement back down the line from his men.

They tagged on behind us, and now, as we neared the station and village, bullets whined high overhead. But most of the rattle of fire was in the village where Taffy Griffiths and Kumba Sing were gradually extricating themselves from their tricky position. We came by the ruins of the old station and took up positions along the railway line to open fire into the village. The Japs were caught by surprise and suffered heavy punishment before switching their attack onto us, but much of their fire went wide.

An armoured car appeared out of the trees, accompanied by infantry, but retreated hastily in the face of a fierce attack launched by Petersen and his King's platoons. Not to be outdone, Calvert, as delighted as a schoolboy, said, 'We'll give them a taste of mortar.' The Gurkha Support Group's 3-inch mortar coughed and there was a flash of flame, an explosion and a fountain of earth.

'Up fifty,' I suggested.

'I think you're right,' Calvert agreed."

After settling back down in Column 7 Petersen was often given the task of covering the outer perimeter during supply drops. Wingate and Gilkes had been impressed by the Danes abilities, especially keeping his group together during the days of separation leading up to the engagement at Nankan. At the Brigade's outward crossing of the Irrawaddy River, Petersen was once again chosen to be first over and to form a protective bridgehead on the eastern banks as protection against any enemy interference. The Chindits assembled on the banks of the 1000m wide river just south of Katha, by the 18th March they were all over and Captain Petersen closed his defensive position.

Many commentators have professed that Wingate made a very large error of judgement by taking his men across to the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy. To his credit, Brigadier Wingate also expressed this view (with hindsight) in his debrief for Operation Longcloth later in 1943. The Brigadier had hoped to gain the support of the local Kachin tribes in the area east of the river, who could protect and assist his Chindits as they continued to harass the Japanese, before they eventually marched out of Burma through the Chinese border provinces.

Once over the Irrawaddy, the Chindits found themselves in fairly dry and waterless country, they were also in a natural 'bag', contained on three sides by the rivers Irrawaddy and Shweli and to their south the Mongmit-Myitson Road, which the Japanese used as their main method of transportation and communication in that area. The men were effectively hemmed in from all sides.

On the 22nd of March Wingate called the various columns in to bivouac on a hillside to the west of a village called Baw. It was decided to call rear base and order the largest supply drop yet. A plan was laid down to secure the local paths and tracks against enemy interference, especially the road to the east of the village which led to the town of Mabein, where the Japanese had a large garrison.

Wingate gave the task of securing the Mabien Road to Captain Coughlan of Column 8, whilst platoons from Column 7 including Petersen's were placed to secure the drop zone area. Unfortunately, having to move through more dense jungle than anticipated, Coughlan's party failed to secure the road before morning and stumbled into a Japanese patrol. The enemy opened fire on the ailing platoon and they were forced back to the north.

Petersen and Gilkes men soon came under enemy fire themselves and the supply drop zone seemed compromised and would surely have to be abandoned. Captain Petersen drove his men forward and cleared the Japanese from his sector, he then saw Captain Coughlan who had been slightly wounded. Coughlan explained that his platoon were tied down by strong enemy fire and could not disengage from the area without suffering heavy casualties. Petersen decided on a plan of attack which he relayed to Coughlan, who then went back to his men.

Petersen used his mortar section to cover his advance and employed a flanking manoeuvre led by Lieutenant Jelliss on the Japanese positions, he had his Bren gun team concentrate on the tree tops where enemy snipers were positioned, eventually Captain Coughlan's platoon managed to escape their predicament and came through Petersen's position to safety. To read more about Captain Coughlan's Platoon and their involvement at Baw, please follow the link below:

Arthur Birch and Platoon 17

Lieutenant-Colonel Cooke, the senior officer in Northern Group and Major Gilkes then approached Petersen and told him that the enemy must be thrown out of Baw so that the supply drop could take place. Petersen told them that a much larger force than the one he commanded would be required to achieve this aim. Major Scott was given orders to assist Petersen and the two groups moved in to position. The men from Column 8 attacked the eastern flank of the enemy whilst Petersen and his men moved head on against the Japanese.

The Chindits fought bravely and after some fierce and bitter battles, drove the Japanese out of the area. Scott and his men had performed valiantly, but had suffered heavy casualties. Lieutenant Pearce and Sergeant Lamb from Petersen's Platoon had done excellent work with their respective Bren guns and grenade launchers.

Towards the end of the engagement Captain Petersen was seriously wounded, he had been shot in the head by a Japanese sniper. He had managed to stem the flow of blood with a field dressing, but then fell unconscious onto the ground. Lieutenant Dennis Russell Chambers of Column 7 was sadly killed during the action at Baw that day. Chambers was commander of Petersen's Reserve Platoon and was out on a recce patrol shortly before the final assault on the enemy. As he stood watching the Japanese positions, he too was shot by an enemy sniper and was killed instantly.

Lieutenant Chambers, originally from Durban, South Africa, had been commissioned into the 3rd Gurkha Rifles in India in late 1942, previously during the war he had fought in the Allied rearguard action on the island of Crete. For more details about Dennis Chambers, please follow the link below to view his CWGC details:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2506861/CHAMBERS,%20DENNIS%20RUSSELL

Seen below is a map of the area around the village of Baw, showing the general terrain and the Japanese garrison town of Mabien on the banks of the Shweli River. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

The men from Platoon 15 took it turns to hold the wounded Petersen as he swayed back and forth and in and out of consciousness aboard his trusted horse. Captain Petersen remembers this time in his diary:

"My wounds were so serious that I could not march. My service horse, which had often been carrying the sick and wounded during the expedition, now carried me. Thanks to my horse and my trusty Batman, Harry Harding, who worked tirelessly at my side and helped me in every way, I managed to follow the Column as it continued east. When we later reached the mountains of the Chinese border, I began to feel better and slowly I could begin to march once more.

After the expedition was over I gave Harding a silver cigarette case with the inscription; "To Harry Harding from Captain W.B.E. Petersen-India-Burma-China 1942-43, as a thank you."

On the 18th April, the Medical Officer from Column 7, Captain A.H. Snalam received new medical supplies from the latest air drop and looked to examine Erik Petersen's wound more closely. To his amazement, he found that although the Japanese bullet had ploughed a deep furrow along the side of his skull, it had not actually penetrated it. Bolstered by this news, good rations and his own strong sense of determination Captain Petersen was soon back on his own two feet.

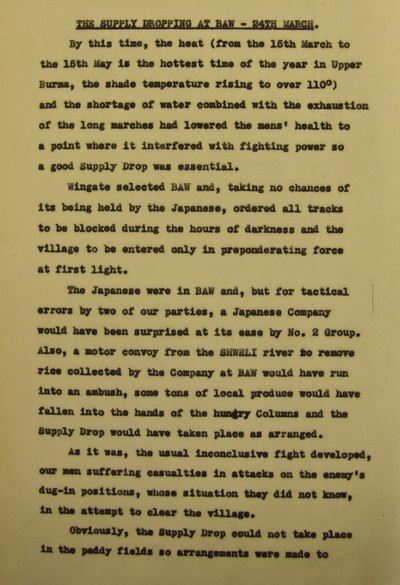

Seen below are two pages from the Operation Longcloth Debrief giving some explanation for the choice of Baw as the supply drop location on March 22nd 1943. Please click on the image to enlarge.

"My wounds were so serious that I could not march. My service horse, which had often been carrying the sick and wounded during the expedition, now carried me. Thanks to my horse and my trusty Batman, Harry Harding, who worked tirelessly at my side and helped me in every way, I managed to follow the Column as it continued east. When we later reached the mountains of the Chinese border, I began to feel better and slowly I could begin to march once more.

After the expedition was over I gave Harding a silver cigarette case with the inscription; "To Harry Harding from Captain W.B.E. Petersen-India-Burma-China 1942-43, as a thank you."

On the 18th April, the Medical Officer from Column 7, Captain A.H. Snalam received new medical supplies from the latest air drop and looked to examine Erik Petersen's wound more closely. To his amazement, he found that although the Japanese bullet had ploughed a deep furrow along the side of his skull, it had not actually penetrated it. Bolstered by this news, good rations and his own strong sense of determination Captain Petersen was soon back on his own two feet.

Seen below are two pages from the Operation Longcloth Debrief giving some explanation for the choice of Baw as the supply drop location on March 22nd 1943. Please click on the image to enlarge.

Shortly after the supply dropping at Baw, the Chindits were ordered back to India. Wingate, in company with Columns 7 and 8 attempted to re-cross the Irrawaddy close to where they had first traversed the river just a few weeks earlier. This crossing had to be abandoned when the leading boats were attacked by enemy mortar and machine gun fire. The Columns decided to split up and then turned east once again.

Major Gilkes had always favoured exiting Burma via the Chinese borders of Yunnan Province. Captain Petersen and Gilkes had discussed this idea at great length just before the expedition began and had gone as far as bringing with them the correct maps for such a venture. Of course Petersen had experience of Yunnan Province from his time with the Lashio Bush Warfare School and understood the conditions and terrain that the exhausted Chindits were likely to face.

The column marched to the Shweli River and after several failed attempts at crossing the fast flowing waters, eventually made the eastern banks with the help of a kindly Burmese headman and his native boats. Gilkes then turned north-east and into Kachin tribal country, the Chindits were now out of range for any possibility of a supply drop and had to really on what food they could obtain from these pro-British villages.

Petersen and his platoon were given the task of Column rear-guard and at the village of Loi Yawng had to engage a strong Japanese patrol that had been tracking the Chindits for several days. With the invaluable help of another local headman, Petersen and Sergeant Fred Thompson were able to ambush the enemy inflicting many casualties on the unsuspecting Japanese.

Column 7 were treated very well by the Chinese troops they encountered on their journey through Yunnan Province. After some arduous marches over very difficult terrain, they finally reached the town of Paoshan, where the local Chinese Commander offered them a sumptuous feast and a welcome change of clothing. After a few days rest the men were loaded on to trucks and driven to a nearby USAAF airfield at Kunming and on the 26th June 1943 they were flown back to Assam.

Major Gilkes and Petersen were admitted in to the hospital at Shillong where he was treated for, amongst other ailments, the wound to his head. For several years Erik Petersen suffered many side effects from this wound, including amnesia, partial blindness and constant dizziness. In 1956 it was discovered that he had sustained internal complications from the gunshot wound and this was corrected by neurosurgery in Copenhagen that year.

Back in India, Petersen left the 13th King's and took up a post in SOE (Special Operations Executive). He was offered a role back in China at a training school in Kunming, but this fell through. He then had some involvement with the initial reconnaissance for the second Chindit Operation in early 1944. Finally, he secured a position in Force 136, where he recruited and trained local partisan groups from the territories of Northern Burma and conducted clandestine operations against the Japanese.

On hearing the news of Wingate's death on 24th March 1944, Petersen was quoted as saying;

"We who had the good fortune to come to serve under him, will never forget him or what he taught us, he was an excellent teacher and commander. We remember him with gratitude and respect."

By late 1944, Petersen, now promoted to Major was working for Force 136 at 14th Army HQ in Comilla, Assam. He performed the role of Intelligence Officer, providing General Slim with informational reports from field operatives inside occupied Burma. In January 1945 and having served over seven years in the Far East, Major Petersen was sent back to England and joined the S.O.E. Scandinavian Department in London. He began work on 'Operation Viking' a combined exercise between the 2nd Canadian Army and the Danish Resistance in Jutland, but the end of hostilities came before the operation could be launched.

After a brief trip to New york to visit his family, Erik Petersen accepted the role as assistant to the then Danish Military Attaché in London, Count Wilhelm Reich Sponneck. His job was to help relocate and find work for the many displaced Danish nationals who now wished to return home. In February 1946 Erik Petersen was dismissed from his service in the British Army with the honorary rank of Major. After returning to Denmark he joined the Danish Life Regiment, with whom he remained until his retirement in 1963. For a short period between 1958 and 1960, Erik worked for N.A.T.O.

On several occasions after the war Erik returned to England to attend various Chindit reunions and once again enjoy the company of his former comrades from Column 7.

Major W.B.E. Petersen received the nickname 'Burma Peter' whilst serving with the Danish Life Regiment after the war. He immediately gained the respect of all those with whom he served, just as he had done back in the jungles of Burma. Erik never spent too much time dwelling on past glories and rarely spoke about his WW2 service. At his farewell dinner on leaving the regiment he presented the commander with a framed copy of Wingate's 'Order of the Day' from 1943. Petersen stated that he often read this order when he was going through troubled or difficult times.

In later years Erik Petersen suffered from Parkinson's disease, but never let this condition dominate his life and typical of any old soldier, met this new foe with stoical resilience. Erik passed away on the 14th July 1999 in the town of Odder, near Aarhus in his beloved Denmark. He was then, as he had always been, 'Petersen, the Fighting Dane'.

Seen below are some images and photographs that further illustrate the story of Erik Petersen, please click on any image to enlarge.

Major Gilkes had always favoured exiting Burma via the Chinese borders of Yunnan Province. Captain Petersen and Gilkes had discussed this idea at great length just before the expedition began and had gone as far as bringing with them the correct maps for such a venture. Of course Petersen had experience of Yunnan Province from his time with the Lashio Bush Warfare School and understood the conditions and terrain that the exhausted Chindits were likely to face.

The column marched to the Shweli River and after several failed attempts at crossing the fast flowing waters, eventually made the eastern banks with the help of a kindly Burmese headman and his native boats. Gilkes then turned north-east and into Kachin tribal country, the Chindits were now out of range for any possibility of a supply drop and had to really on what food they could obtain from these pro-British villages.

Petersen and his platoon were given the task of Column rear-guard and at the village of Loi Yawng had to engage a strong Japanese patrol that had been tracking the Chindits for several days. With the invaluable help of another local headman, Petersen and Sergeant Fred Thompson were able to ambush the enemy inflicting many casualties on the unsuspecting Japanese.

Column 7 were treated very well by the Chinese troops they encountered on their journey through Yunnan Province. After some arduous marches over very difficult terrain, they finally reached the town of Paoshan, where the local Chinese Commander offered them a sumptuous feast and a welcome change of clothing. After a few days rest the men were loaded on to trucks and driven to a nearby USAAF airfield at Kunming and on the 26th June 1943 they were flown back to Assam.

Major Gilkes and Petersen were admitted in to the hospital at Shillong where he was treated for, amongst other ailments, the wound to his head. For several years Erik Petersen suffered many side effects from this wound, including amnesia, partial blindness and constant dizziness. In 1956 it was discovered that he had sustained internal complications from the gunshot wound and this was corrected by neurosurgery in Copenhagen that year.

Back in India, Petersen left the 13th King's and took up a post in SOE (Special Operations Executive). He was offered a role back in China at a training school in Kunming, but this fell through. He then had some involvement with the initial reconnaissance for the second Chindit Operation in early 1944. Finally, he secured a position in Force 136, where he recruited and trained local partisan groups from the territories of Northern Burma and conducted clandestine operations against the Japanese.

On hearing the news of Wingate's death on 24th March 1944, Petersen was quoted as saying;

"We who had the good fortune to come to serve under him, will never forget him or what he taught us, he was an excellent teacher and commander. We remember him with gratitude and respect."

By late 1944, Petersen, now promoted to Major was working for Force 136 at 14th Army HQ in Comilla, Assam. He performed the role of Intelligence Officer, providing General Slim with informational reports from field operatives inside occupied Burma. In January 1945 and having served over seven years in the Far East, Major Petersen was sent back to England and joined the S.O.E. Scandinavian Department in London. He began work on 'Operation Viking' a combined exercise between the 2nd Canadian Army and the Danish Resistance in Jutland, but the end of hostilities came before the operation could be launched.

After a brief trip to New york to visit his family, Erik Petersen accepted the role as assistant to the then Danish Military Attaché in London, Count Wilhelm Reich Sponneck. His job was to help relocate and find work for the many displaced Danish nationals who now wished to return home. In February 1946 Erik Petersen was dismissed from his service in the British Army with the honorary rank of Major. After returning to Denmark he joined the Danish Life Regiment, with whom he remained until his retirement in 1963. For a short period between 1958 and 1960, Erik worked for N.A.T.O.

On several occasions after the war Erik returned to England to attend various Chindit reunions and once again enjoy the company of his former comrades from Column 7.

Major W.B.E. Petersen received the nickname 'Burma Peter' whilst serving with the Danish Life Regiment after the war. He immediately gained the respect of all those with whom he served, just as he had done back in the jungles of Burma. Erik never spent too much time dwelling on past glories and rarely spoke about his WW2 service. At his farewell dinner on leaving the regiment he presented the commander with a framed copy of Wingate's 'Order of the Day' from 1943. Petersen stated that he often read this order when he was going through troubled or difficult times.

In later years Erik Petersen suffered from Parkinson's disease, but never let this condition dominate his life and typical of any old soldier, met this new foe with stoical resilience. Erik passed away on the 14th July 1999 in the town of Odder, near Aarhus in his beloved Denmark. He was then, as he had always been, 'Petersen, the Fighting Dane'.

Seen below are some images and photographs that further illustrate the story of Erik Petersen, please click on any image to enlarge.

This story could not have been written without the invaluable assistance of the following people:

Tom Andersen, for his help with translation and contact with Knud Rasmussen.

Knud Rasmussen, for allowing the use of information from his book 'Burma Peter'.

Bjoern Koch Klausen, for great help with Petersen's military career and medal identification.

Here is a link to Bjoern's superb website:http://www.danes-at-war.dk

Lars Ahlkvist, for his continuing support with this and other pages on my website.

Phil Chinnery, for allowing me to use material from his books.

Tom Andersen, for his help with translation and contact with Knud Rasmussen.

Knud Rasmussen, for allowing the use of information from his book 'Burma Peter'.

Bjoern Koch Klausen, for great help with Petersen's military career and medal identification.

Here is a link to Bjoern's superb website:http://www.danes-at-war.dk

Lars Ahlkvist, for his continuing support with this and other pages on my website.

Phil Chinnery, for allowing me to use material from his books.

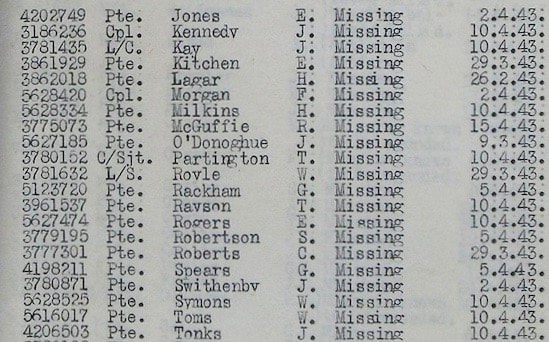

What happened to the men of Petersen's Platoon 15 and the other soldiers from 'Viking Force.'

Lieutenant H.S. Pearce parted company with Petersen and the rest of Column 7 at the failed Irrawaddy crossing on 29th March. He became HQ Brigade's Adjutant after the death of Captain Hastings and eventually led his own dispersal group back to India in late May 1943.

Pte. Harry Harding, nothing more is known about Petersen's batman, who presumably travelled with his Captain through the Chinese Borders and flew out of Kunming courtesy of the USAAF.

Sergeant Fred Thompson. Fred continued to serve with the 13th King's after recovering from Operation Longcloth. In February 1945, the remaining men from the King's became the 15th (King's) Parachute Battalion, Fred did not volunteer for this new unit and soon qualified for repatriation, sailing home in November 1945.

Pte. John D.P. O’Donoghue. Petersen's Platoon had joined up with Column 3 at the rail station in Nankan, where they engaged a large group of Japanese, whilst Mike Calvert and his demolition engineers destroyed the rail bridge and infrastructure. O’Donoghue was lost on 9th March with another Chindit called Fred Turner. Both men had been acting as rearguard for the platoon and failed to return to the unit at the agreed rendezvous.

Lance Corporal Fred Turner. Lance Corporal Turner was lost from Lieutenant Petersen’s unit on the 9th March 1943 at Nankan rail station along with Pte. O’Donoghue. Nothing more was seen or heard of these two men, Turner was from Kenton in Devon.

Pte. William McIntyre. William served with Captain Petersen for the majority of the expedition in 1943. After being part of the bridgehead unit at the Shweli River, it is not known with whom he dispersed. Unfortunately, William did not make it out of China in 1943, a fellow Chindit, Pte. J. Greavey gave this witness report in regard to Pte. McIntyre and his last known movements:

“I was a member of 15 Platoon, 7 Column, in Brigadier Wingate’s expedition into Burma from January to June 1943.

About the third week in May I was a member of a small party of about six men marching North-east towards the China border. Pte. McCartney was in charge of the party and we eventually arrived at Fort Morton.

There we saw Pte. McIntyre; he had been ill for two days, and during this period he had been cared for by Chinese villagers. Our party stayed at Fort Morton for one night and set out on our journey the next morning. Pte. McIntyre, who was feeling a little better stated that he thought he was capable of continuing the journey with us; however after about a half hour’s march he took ill again, and set out on his own to Fort Morton.

That was the last we saw of him on approximately 20/05/43. He had neither arms or equipment, but I think he was in possession of about 30 rupees in money".

Sadly, William McIntyre died the following day.

Pte. J. Greavey. As seen from the above witness statement, Pte. Greavey succeeded in exiting China in June 1943 and continued to serve with the 13th King's after recovering from the trials of the expedition.

Sergeant J. Lamb. The expert grande-launcher at the battle of Baw. Lamb survived Operation Longcloth and was instrumental in providing witness statements for many of the men who did not return, these included, Fred Turner and John O'Donoghue.

Corporal Arthur Clegg. Corporal Clegg, a resident of Stockport, was left in a friendly Kachin village suffering from exhaustion on 3rd May 1943. According to his POW index card he was captured on 28th June. Arthur survived his time in Japanese hands and was liberated from Rangoon Jail in late April 1945.

Other Members of 'Viking Force' in March 1943

Pte. Leon Frank. Leon was a member of Platoon 13, Column 7, but found himself with Captain Petersen at Nankan railway station in March 1943. Leon eventually dispersed with Captain Musgrave-Wood's party, which included my own grandfather. He was captured on the 21st May and spent two years in Rangoon Jail, the only survivor from the group that was separated from Musgrave-Wood in April 1943. To read more about Leon Frank, please follow the link below:

Pte. Leon Frank

Pte. H. Griffin. Pte. Griffin survived the expedition in 1943 and had been a member of "Viking Force' at Nankan. At the Shweli River rendezvous he was placed into Lieutenant Wilkinson' dispersal group. In early April he and some other men became separated from the main group near a village called Senan. After reaching the safety of India, Griffin gave witness statements for some of the other previous members of 'Viking Force.'

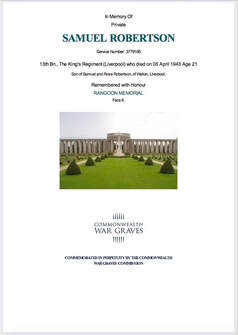

Pte. Samuel Robertson. According to Pte. Griffin, Samuel suffered a gun shot wound to his back on April 5th, he was left in a nearby village, but was already near death. To read more about Samuel Robertson, please see the update at the foot of this page.

Pte. Thomas Humphries. Not long after Samuel Robertson was killed, Thomas and another soldier, Pte. George Spears decided to go there own way and set off in the opposite direction to the rest of the dispersal group. They were never seen again.

Pte. George Spears. George decided to leave the dispersal party with Thomas Humphries, they were just nine miles from the relative safety of the Chindwin River. George and Thomas were never heard of again.

Pte. W. Elliots. Pte. Elliots also left witness statements in regards to Humphries, Spears and Robertson, confirming the information given by Pte. Griffin.

Seen below, photographs of Fred Thompson and William McIntyre. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Lieutenant H.S. Pearce parted company with Petersen and the rest of Column 7 at the failed Irrawaddy crossing on 29th March. He became HQ Brigade's Adjutant after the death of Captain Hastings and eventually led his own dispersal group back to India in late May 1943.

Pte. Harry Harding, nothing more is known about Petersen's batman, who presumably travelled with his Captain through the Chinese Borders and flew out of Kunming courtesy of the USAAF.

Sergeant Fred Thompson. Fred continued to serve with the 13th King's after recovering from Operation Longcloth. In February 1945, the remaining men from the King's became the 15th (King's) Parachute Battalion, Fred did not volunteer for this new unit and soon qualified for repatriation, sailing home in November 1945.

Pte. John D.P. O’Donoghue. Petersen's Platoon had joined up with Column 3 at the rail station in Nankan, where they engaged a large group of Japanese, whilst Mike Calvert and his demolition engineers destroyed the rail bridge and infrastructure. O’Donoghue was lost on 9th March with another Chindit called Fred Turner. Both men had been acting as rearguard for the platoon and failed to return to the unit at the agreed rendezvous.

Lance Corporal Fred Turner. Lance Corporal Turner was lost from Lieutenant Petersen’s unit on the 9th March 1943 at Nankan rail station along with Pte. O’Donoghue. Nothing more was seen or heard of these two men, Turner was from Kenton in Devon.

Pte. William McIntyre. William served with Captain Petersen for the majority of the expedition in 1943. After being part of the bridgehead unit at the Shweli River, it is not known with whom he dispersed. Unfortunately, William did not make it out of China in 1943, a fellow Chindit, Pte. J. Greavey gave this witness report in regard to Pte. McIntyre and his last known movements:

“I was a member of 15 Platoon, 7 Column, in Brigadier Wingate’s expedition into Burma from January to June 1943.

About the third week in May I was a member of a small party of about six men marching North-east towards the China border. Pte. McCartney was in charge of the party and we eventually arrived at Fort Morton.

There we saw Pte. McIntyre; he had been ill for two days, and during this period he had been cared for by Chinese villagers. Our party stayed at Fort Morton for one night and set out on our journey the next morning. Pte. McIntyre, who was feeling a little better stated that he thought he was capable of continuing the journey with us; however after about a half hour’s march he took ill again, and set out on his own to Fort Morton.

That was the last we saw of him on approximately 20/05/43. He had neither arms or equipment, but I think he was in possession of about 30 rupees in money".

Sadly, William McIntyre died the following day.

Pte. J. Greavey. As seen from the above witness statement, Pte. Greavey succeeded in exiting China in June 1943 and continued to serve with the 13th King's after recovering from the trials of the expedition.

Sergeant J. Lamb. The expert grande-launcher at the battle of Baw. Lamb survived Operation Longcloth and was instrumental in providing witness statements for many of the men who did not return, these included, Fred Turner and John O'Donoghue.

Corporal Arthur Clegg. Corporal Clegg, a resident of Stockport, was left in a friendly Kachin village suffering from exhaustion on 3rd May 1943. According to his POW index card he was captured on 28th June. Arthur survived his time in Japanese hands and was liberated from Rangoon Jail in late April 1945.

Other Members of 'Viking Force' in March 1943

Pte. Leon Frank. Leon was a member of Platoon 13, Column 7, but found himself with Captain Petersen at Nankan railway station in March 1943. Leon eventually dispersed with Captain Musgrave-Wood's party, which included my own grandfather. He was captured on the 21st May and spent two years in Rangoon Jail, the only survivor from the group that was separated from Musgrave-Wood in April 1943. To read more about Leon Frank, please follow the link below:

Pte. Leon Frank

Pte. H. Griffin. Pte. Griffin survived the expedition in 1943 and had been a member of "Viking Force' at Nankan. At the Shweli River rendezvous he was placed into Lieutenant Wilkinson' dispersal group. In early April he and some other men became separated from the main group near a village called Senan. After reaching the safety of India, Griffin gave witness statements for some of the other previous members of 'Viking Force.'

Pte. Samuel Robertson. According to Pte. Griffin, Samuel suffered a gun shot wound to his back on April 5th, he was left in a nearby village, but was already near death. To read more about Samuel Robertson, please see the update at the foot of this page.

Pte. Thomas Humphries. Not long after Samuel Robertson was killed, Thomas and another soldier, Pte. George Spears decided to go there own way and set off in the opposite direction to the rest of the dispersal group. They were never seen again.

Pte. George Spears. George decided to leave the dispersal party with Thomas Humphries, they were just nine miles from the relative safety of the Chindwin River. George and Thomas were never heard of again.

Pte. W. Elliots. Pte. Elliots also left witness statements in regards to Humphries, Spears and Robertson, confirming the information given by Pte. Griffin.

Seen below, photographs of Fred Thompson and William McIntyre. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 09/08/2021.

Samuel Robertson

I was delighted to receive the following email contact from Nicola Eaton, the great niece of Samuel Robertson:

Dear Steve, thank you so much for establishing this website, where I have been able to find information about my great uncle Pte. 3779195 Samuel Robertson. Through your pages on Lt. Robert Wilkinson and Major Petersen I was able to read about how Samuel died. My great grandmother who I was very close to never knew what happened to Sam, who was her eldest child, she was only told he died in Burma and worked on the railways. She would have been so proud to hear of him being a Chindit. She told me several times of how she was so cross when he "took the King's shilling" as he was underage, but she remembered he was so excited about joining the Army.

My Dad and I always hoped that Sam never ended up in a Japanese prison and although it was very sad to read of how he died, at least we now know that he didn't end up as a prisoner of war. Sam was born and bred in Liverpool and had five siblings and many of his family, including my parents still live in the Liverpool area. Sam's younger brother Bobby has just turned 90 and although communication with him is difficult, my Dad told him about the information we had found and he said that he didn't know about any of it. I would be very grateful if you could give me any further information in relation to Sam and once again many thanks, knowing that Sam was a Chindit made myself, my brother, my Dad and my own two children very proud. I have been in touch with my auntie to ask if she has a photograph of Samuel or if she knows who would. As he was one of six and it was so long ago, I don't know who might have inherited Samuel's effects, but if we find any I will certainly send these on to you.

It is strange that Samuel was part of the 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment as many of the men were much older than he was. I have found it very interesting to read how this unlikely battalion ended up as Chindits and what they experienced in Burma. My Dad remembers a photograph of Samuel from before the war and thinks he was quite short in stature, but he was obviously very tough to survive the jungle training, never mind the awful conditions they experienced in Burma. Very best wishes, Nicola Eaton.

I replied:

Dear Nicola,

Thank you for your email contact via my website in relation to Samuel Robertson. I was very touched to receive your message about him and the sad effect his loss had on your family. Obviously, if you have read about my own grandfather on the website, you will know that my family shared a similar experience in 1943. I do have some papers and other items for you in regards to Samuel and I will collect these together and send them over in the next couple of days.

As you will have read, Samuel was a member of No. 7 Column on Operation Longcloth and had re-crossed the Irrawaddy on the return journey to India in 1943. The main information in regards to Samuel's eventual fate was found in a witness statement written by Pte. H. Griffin on his return to India after the expedition:

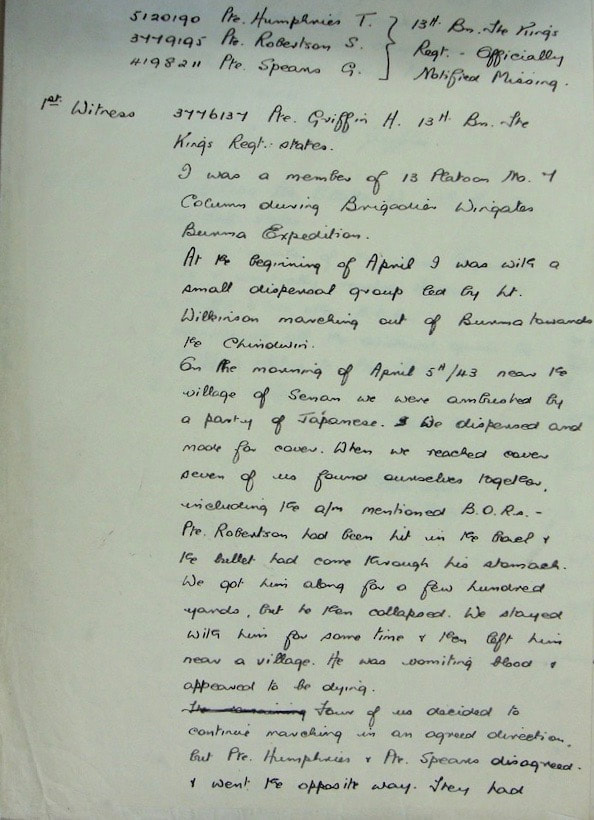

Pte. 3776137 H. Griffin 13th Battalion, the King’s Regiment witness statement dated 24th July 1943:

In the case of Pte. T. Humphries, Pte. S. Robertson and Pte. G. Spears.

I was a member of 13 Platoon, No. 7 Column during Brigadier Wingate’s Burma expedition. At the beginning of April, I was with a small dispersal group led by Lt. Wilkinson marching out of Burma towards the Chindwin River. On the morning of April 5th, near the village of Senan we were ambushed by a party of Japanese. We dispersed and made for cover. When we reached cover, seven of us found ourselves together including the above mentioned British Other Ranks.

Pte. Robertson had been hit in the back and the bullet had come through his stomach. We got him along for a few hundred yards, but he then collapsed. We stayed with him for some time and then left him near a village. He was vomiting blood and appeared to be dying. Four of us decided to continue marching in an agreed direction, but Humphries and Spears disagreed and went the opposite way. They had no arms or ammunition with them, having lost them in the skirmish. They had no food or equipment, but a certain amount of money. They were about nine-days march from the Chindwin, but they have not been heard of since.

Pte. Griffin’s statement is then confirmed by a second witness, Pte. 4915134 W. Elliots, who states:

I was a member of the above dispersal group and eventually reached Assam with Pte. Griffin and two other men. I corroborate all the evidence given by Pte. Griffin relating to Ptes. Robertson, Humphries and Spears.

The witness statement was then signed off by Captain Henry Cotton of No. 7 Column.

Samuel Robertson

I was delighted to receive the following email contact from Nicola Eaton, the great niece of Samuel Robertson:

Dear Steve, thank you so much for establishing this website, where I have been able to find information about my great uncle Pte. 3779195 Samuel Robertson. Through your pages on Lt. Robert Wilkinson and Major Petersen I was able to read about how Samuel died. My great grandmother who I was very close to never knew what happened to Sam, who was her eldest child, she was only told he died in Burma and worked on the railways. She would have been so proud to hear of him being a Chindit. She told me several times of how she was so cross when he "took the King's shilling" as he was underage, but she remembered he was so excited about joining the Army.

My Dad and I always hoped that Sam never ended up in a Japanese prison and although it was very sad to read of how he died, at least we now know that he didn't end up as a prisoner of war. Sam was born and bred in Liverpool and had five siblings and many of his family, including my parents still live in the Liverpool area. Sam's younger brother Bobby has just turned 90 and although communication with him is difficult, my Dad told him about the information we had found and he said that he didn't know about any of it. I would be very grateful if you could give me any further information in relation to Sam and once again many thanks, knowing that Sam was a Chindit made myself, my brother, my Dad and my own two children very proud. I have been in touch with my auntie to ask if she has a photograph of Samuel or if she knows who would. As he was one of six and it was so long ago, I don't know who might have inherited Samuel's effects, but if we find any I will certainly send these on to you.

It is strange that Samuel was part of the 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment as many of the men were much older than he was. I have found it very interesting to read how this unlikely battalion ended up as Chindits and what they experienced in Burma. My Dad remembers a photograph of Samuel from before the war and thinks he was quite short in stature, but he was obviously very tough to survive the jungle training, never mind the awful conditions they experienced in Burma. Very best wishes, Nicola Eaton.

I replied:

Dear Nicola,

Thank you for your email contact via my website in relation to Samuel Robertson. I was very touched to receive your message about him and the sad effect his loss had on your family. Obviously, if you have read about my own grandfather on the website, you will know that my family shared a similar experience in 1943. I do have some papers and other items for you in regards to Samuel and I will collect these together and send them over in the next couple of days.

As you will have read, Samuel was a member of No. 7 Column on Operation Longcloth and had re-crossed the Irrawaddy on the return journey to India in 1943. The main information in regards to Samuel's eventual fate was found in a witness statement written by Pte. H. Griffin on his return to India after the expedition:

Pte. 3776137 H. Griffin 13th Battalion, the King’s Regiment witness statement dated 24th July 1943:

In the case of Pte. T. Humphries, Pte. S. Robertson and Pte. G. Spears.

I was a member of 13 Platoon, No. 7 Column during Brigadier Wingate’s Burma expedition. At the beginning of April, I was with a small dispersal group led by Lt. Wilkinson marching out of Burma towards the Chindwin River. On the morning of April 5th, near the village of Senan we were ambushed by a party of Japanese. We dispersed and made for cover. When we reached cover, seven of us found ourselves together including the above mentioned British Other Ranks.

Pte. Robertson had been hit in the back and the bullet had come through his stomach. We got him along for a few hundred yards, but he then collapsed. We stayed with him for some time and then left him near a village. He was vomiting blood and appeared to be dying. Four of us decided to continue marching in an agreed direction, but Humphries and Spears disagreed and went the opposite way. They had no arms or ammunition with them, having lost them in the skirmish. They had no food or equipment, but a certain amount of money. They were about nine-days march from the Chindwin, but they have not been heard of since.

Pte. Griffin’s statement is then confirmed by a second witness, Pte. 4915134 W. Elliots, who states:

I was a member of the above dispersal group and eventually reached Assam with Pte. Griffin and two other men. I corroborate all the evidence given by Pte. Griffin relating to Ptes. Robertson, Humphries and Spears.

The witness statement was then signed off by Captain Henry Cotton of No. 7 Column.

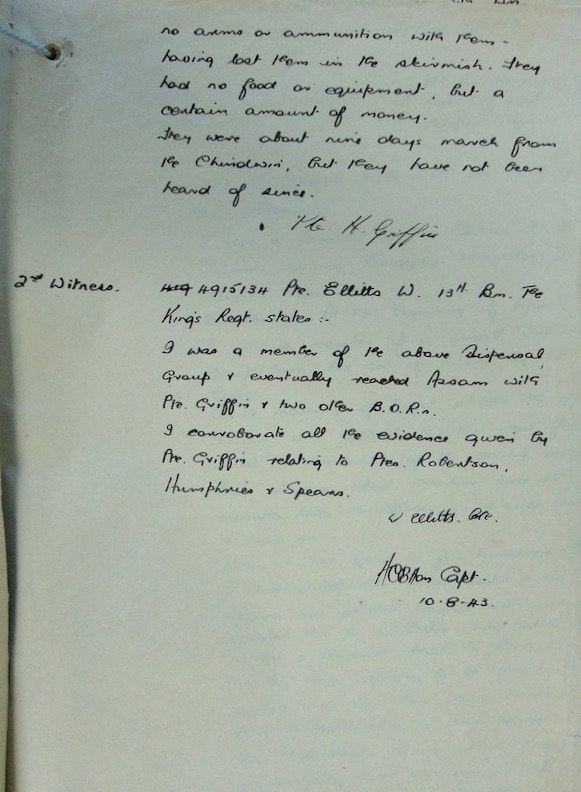

I have located the village of Senan from some maps of Burma (see gallery below) and it shows the village location to be close to Didauk, which was one of the villages that No. 7 Column passed through on the way into Burma in February 1943. So, it would suggest the Lt. Wilkinson and the other men were retracing their steps in an attempt to reach the Chindwin and that Samuel was only a few days march from safety when he died.

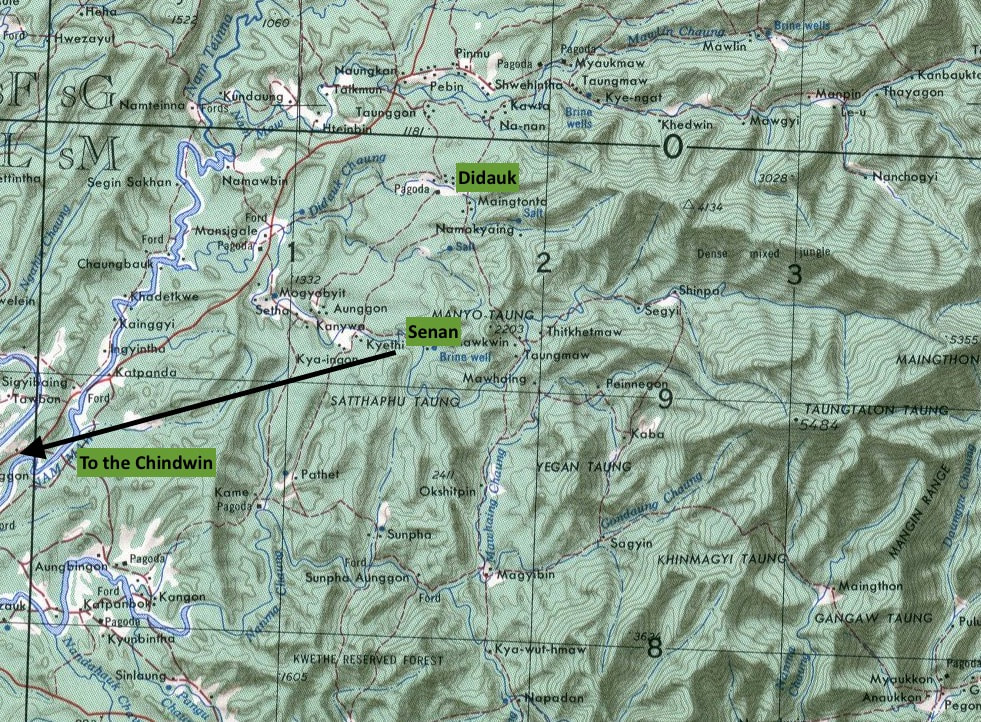

Samuel is remembered upon the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery located on the northern outskirts of Yangon. Sadly, the fact that he is featured on this memorial, means that his actual grave was never found after the war, although every effort was made to locate lost soldiers and their final resting places. Finally, I was able to access Samuel's Army will from the MOD which he arranged in March 1942 and where he left all his worldly possessions to his mother, Rose.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this short update, including Pte. Griffin's original witness statement given in July 1943. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. NB. After receiving further information from Nicola, we now know that Samuel began his WW2 service with the 8th Battalion (Irish) of the Liverpool Regiment and had performed coastal defence duties in south-eastern England before being posted overseas.

Samuel is remembered upon the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery located on the northern outskirts of Yangon. Sadly, the fact that he is featured on this memorial, means that his actual grave was never found after the war, although every effort was made to locate lost soldiers and their final resting places. Finally, I was able to access Samuel's Army will from the MOD which he arranged in March 1942 and where he left all his worldly possessions to his mother, Rose.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this short update, including Pte. Griffin's original witness statement given in July 1943. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. NB. After receiving further information from Nicola, we now know that Samuel began his WW2 service with the 8th Battalion (Irish) of the Liverpool Regiment and had performed coastal defence duties in south-eastern England before being posted overseas.