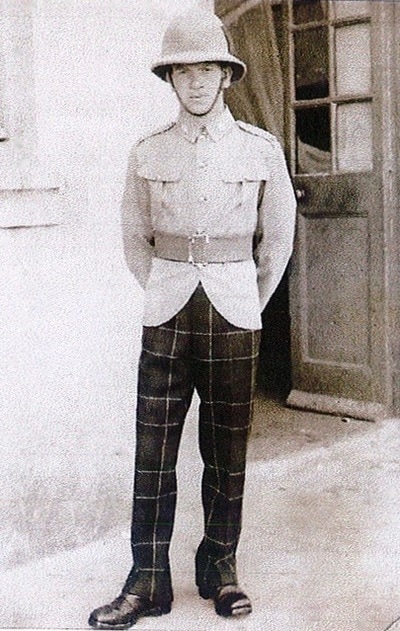

Piercy, Hardy and Litherland, after the ambush at Hintha

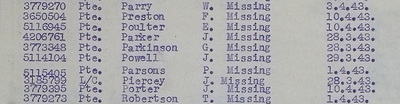

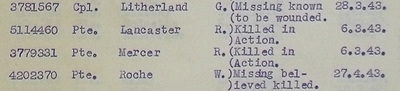

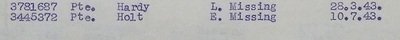

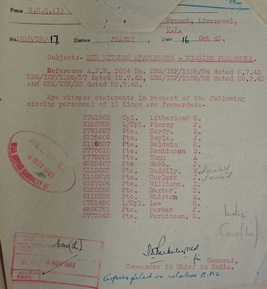

List of personnel lost at the Hintha ambush.

List of personnel lost at the Hintha ambush.

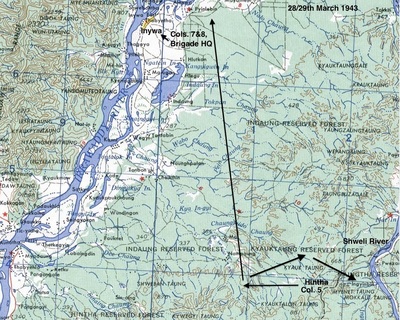

During the third week of March 1943, 5 Column had been given orders to create a diversion for the rest of the Chindit Brigade, which was now trapped in a three-sided bag between the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers to the west and north, and the Mongmit-Myitson motor road to the south. Brigadier Wingate had instructed Fergusson to "trail his coat" and lead the Japanese pursuers away from the general direction of the Irrawaddy and in particular the area around the town of Inywa, where Wingate was hoping to cross the river with the majority of his Brigade as they began their return journey to India.

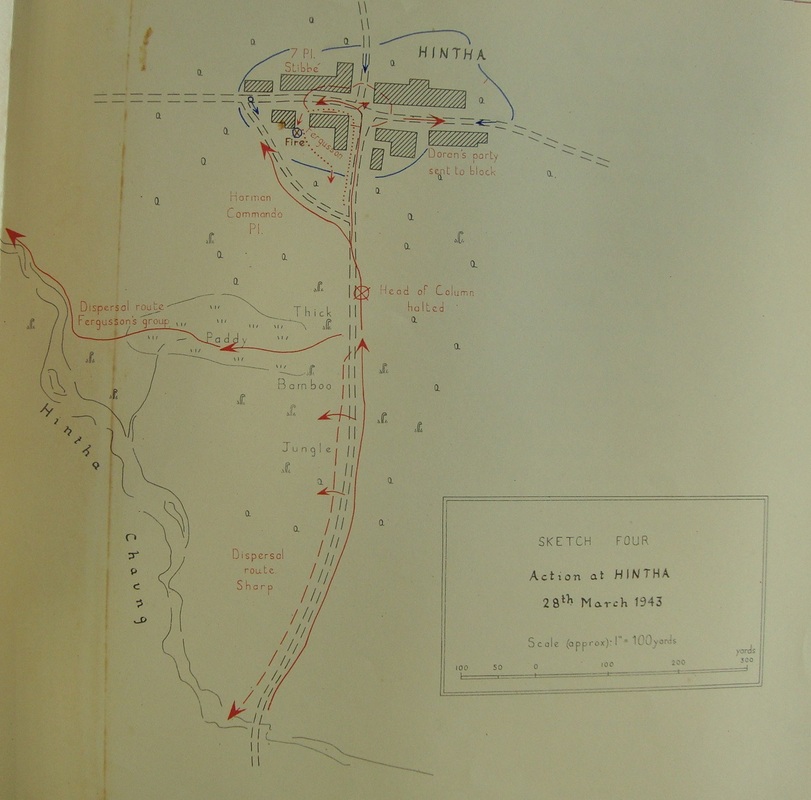

By March 28th, 5 Column had reached the village of Hintha which was situated in an area of thick and tight-set bamboo scrub. Any attempt to navigate around the settlement proved impossible. Rather reluctantly, Major Fergusson decided to enter the village by the main track and check for the presence of any enemy patrols. He unluckily stumbled upon such a patrol and a fire-fight ensued. Hintha became 5 Column's Waterloo and they suffered many casualties in their struggle to extricate themselves from the village. On their travels away from Hintha and whilst attempting to rejoin the rest of the Brigade, 5 Column were attacked by the Japanese for a second time about 3 miles north-east of Hintha, causing a split in the column and the separation of around one hundred men.

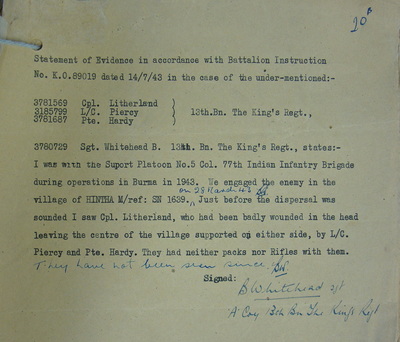

This short account describes the eventual fate of three men, Corporal George Litherland, Pte. Leslie Hardy and Pte. James Miller Stuart Piercy, who were all thrown together by their misfortune at Hintha on the 28th March 1943. Their story is centred around one single witness statement given by Sgt. B. Whitehead of the 13th Battalion, The King's Regiment on the 14th July 1943:

3780729 Sgt. B. Whitehead states- I was with the Support Platoon No.5 Column, 77th Indian Infantry Brigade during the operations in Burma in 1943. We engaged the enemy in the village of Hintha, map reference: SN 1639 on the 28th March 1943. Just before the dispersal was sounded, I saw Cpl. Litherland, who had been badly wounded in the head leaving the centre of the village supported on either side by L/Cpl. Piercy and Pte. Hardy. They had neither packs nor rifles with them. They have not been seen since.

NB. As you might already have noticed, the identification of rank for the three soldiers in question does differ somewhat, either in regards to the recollection on any witness statement, or as written down on some official Army listings or nominal rolls. Many men were promoted in the field during Operation Longcloth and many again inside Rangoon Jail whilst prisoners of war. This may account for the discrepancies in rank as the following story unfolds.

Pte. 3185799 James Miller Stuart Piercy, was born on the 26th June 1914 in the Northumbrian town of Berwick, he was the son of William and Christina Piercy from Kelso, in the Scottish County of Roxburghshire. James had originally enlisted in to the King's Own Scottish Borderers, before eventually being posted to the 13th King's and travelling to India in 1942. He was sadly the first of the three soldiers to perish on Operation Longcloth and is recorded as having been lost on the 28th March 1943, almost certainly as a consequence of the enemy ambush just outside the village of Hintha. An official document listing the last known whereabouts of those men missing from the first Wingate expedition, states that L/Cpl. Piercy was last seen: On the 28th March 1943, leaving the village of Hintha. Map reference SN 1639.

We already know from Sgt. Whitehead's witness statement, that James was helping his wounded comrade, George Litherland, as the column moved away from the village of Hintha. It seems likely that he was somewhere towards the middle of the column when the Japanese ambush took place some hours later, and that he was fatally wounded at the scene or killed outright during the engagement with the enemy.

Another soldier formerly with the King's Own Scottish Borderers, Company Quartermaster Sergeant Ernest Henderson, also gave a witness statement after Operation Longcloth in relation to the ambush on the 28th March 1943. Ernest recalled:

I was with number five Column of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, during operations in Burma in 1943. The above-mentioned British Other Ranks were in my dispersal group all the way through the campaign until we made contact with the enemy in a village in Burma called Hintha.

After the action in that village was over, the above-mentioned soldiers were still in my dispersal group, which was then commanded by Flight Lieutenant Sharp of the RAF. We halted and unsaddled our mules so we could go ahead much quicker. After starting off from that halt, which was approximately 2 miles from Hintha, we were attacked by a Japanese patrol. This caused a gap in the column, but we kept marching for approximately another 4 miles and then stopped, we waited for these people to catch up, but they must have gone wrong way, because they did not rejoin us again. I saw all the above-mentioned men for the last time approximately two and a half miles north east of Hintha. They were all alive, and last seen on 28th March 1943.

NB. It should be noted, that the men listed by Sgt. Henderson did not include Cpl. Litherland, Pte. Hardy or James Piercy.

In late June 2016, I was fortunate to receive an email enquiry from Richard Piercy:

I would like to know if you have anymore information on 3185799 Pte James Piercy (died 28/03/43), who is my great uncle. I only found out he was a Chindit when I researched the Chindits on the British Army's Jungle Warfare Course. I was then serving as an officer in the Royal Artillery. I knew he died in the far east in WW2 as my Grandma told me that: "he went into the jungle and never came out." It seems from your website that he may have been with Lt. Stibbe's platoon.

After exchanging several emails, Richard also told me:

Steve,

Thank you so much for the information you sent me. I have shared the detail you provided with my Dad and in his words you have helped clarify the family myth of what happened to James. My Dad was born in 1951 and so only ever knew the story as told by his grandparents and his own father (James’ younger brother). Given the lack of clarity around the death at the time, it was accepted by the family that James died in the Far East, but no search for anymore information ever took place. Dad is now going to reach out to his cousins to see if there is a photograph of James, or a way to get more information and if the family still have any letters or similar items. They are also going to see if they can confirm the next of kin, to allow the family to request his Army Service records.

Many thanks again, Richard.

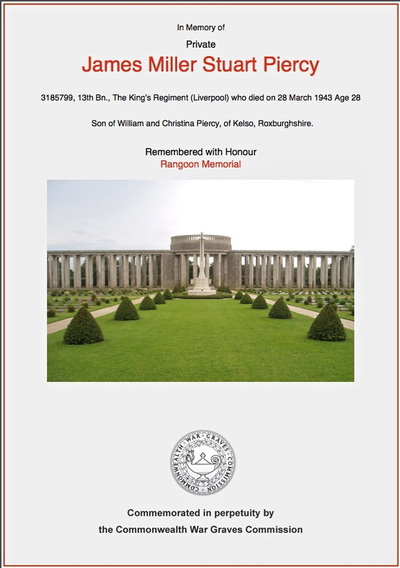

After the war, Pte. Piercy's body was never recovered and no grave was ever found. For this reason he is remembered upon the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery which is located on the northern outskirts of the capital city. Seen below are some images in relation to this part of the story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

By March 28th, 5 Column had reached the village of Hintha which was situated in an area of thick and tight-set bamboo scrub. Any attempt to navigate around the settlement proved impossible. Rather reluctantly, Major Fergusson decided to enter the village by the main track and check for the presence of any enemy patrols. He unluckily stumbled upon such a patrol and a fire-fight ensued. Hintha became 5 Column's Waterloo and they suffered many casualties in their struggle to extricate themselves from the village. On their travels away from Hintha and whilst attempting to rejoin the rest of the Brigade, 5 Column were attacked by the Japanese for a second time about 3 miles north-east of Hintha, causing a split in the column and the separation of around one hundred men.

This short account describes the eventual fate of three men, Corporal George Litherland, Pte. Leslie Hardy and Pte. James Miller Stuart Piercy, who were all thrown together by their misfortune at Hintha on the 28th March 1943. Their story is centred around one single witness statement given by Sgt. B. Whitehead of the 13th Battalion, The King's Regiment on the 14th July 1943:

3780729 Sgt. B. Whitehead states- I was with the Support Platoon No.5 Column, 77th Indian Infantry Brigade during the operations in Burma in 1943. We engaged the enemy in the village of Hintha, map reference: SN 1639 on the 28th March 1943. Just before the dispersal was sounded, I saw Cpl. Litherland, who had been badly wounded in the head leaving the centre of the village supported on either side by L/Cpl. Piercy and Pte. Hardy. They had neither packs nor rifles with them. They have not been seen since.

NB. As you might already have noticed, the identification of rank for the three soldiers in question does differ somewhat, either in regards to the recollection on any witness statement, or as written down on some official Army listings or nominal rolls. Many men were promoted in the field during Operation Longcloth and many again inside Rangoon Jail whilst prisoners of war. This may account for the discrepancies in rank as the following story unfolds.

Pte. 3185799 James Miller Stuart Piercy, was born on the 26th June 1914 in the Northumbrian town of Berwick, he was the son of William and Christina Piercy from Kelso, in the Scottish County of Roxburghshire. James had originally enlisted in to the King's Own Scottish Borderers, before eventually being posted to the 13th King's and travelling to India in 1942. He was sadly the first of the three soldiers to perish on Operation Longcloth and is recorded as having been lost on the 28th March 1943, almost certainly as a consequence of the enemy ambush just outside the village of Hintha. An official document listing the last known whereabouts of those men missing from the first Wingate expedition, states that L/Cpl. Piercy was last seen: On the 28th March 1943, leaving the village of Hintha. Map reference SN 1639.

We already know from Sgt. Whitehead's witness statement, that James was helping his wounded comrade, George Litherland, as the column moved away from the village of Hintha. It seems likely that he was somewhere towards the middle of the column when the Japanese ambush took place some hours later, and that he was fatally wounded at the scene or killed outright during the engagement with the enemy.

Another soldier formerly with the King's Own Scottish Borderers, Company Quartermaster Sergeant Ernest Henderson, also gave a witness statement after Operation Longcloth in relation to the ambush on the 28th March 1943. Ernest recalled:

I was with number five Column of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, during operations in Burma in 1943. The above-mentioned British Other Ranks were in my dispersal group all the way through the campaign until we made contact with the enemy in a village in Burma called Hintha.

After the action in that village was over, the above-mentioned soldiers were still in my dispersal group, which was then commanded by Flight Lieutenant Sharp of the RAF. We halted and unsaddled our mules so we could go ahead much quicker. After starting off from that halt, which was approximately 2 miles from Hintha, we were attacked by a Japanese patrol. This caused a gap in the column, but we kept marching for approximately another 4 miles and then stopped, we waited for these people to catch up, but they must have gone wrong way, because they did not rejoin us again. I saw all the above-mentioned men for the last time approximately two and a half miles north east of Hintha. They were all alive, and last seen on 28th March 1943.

NB. It should be noted, that the men listed by Sgt. Henderson did not include Cpl. Litherland, Pte. Hardy or James Piercy.

In late June 2016, I was fortunate to receive an email enquiry from Richard Piercy:

I would like to know if you have anymore information on 3185799 Pte James Piercy (died 28/03/43), who is my great uncle. I only found out he was a Chindit when I researched the Chindits on the British Army's Jungle Warfare Course. I was then serving as an officer in the Royal Artillery. I knew he died in the far east in WW2 as my Grandma told me that: "he went into the jungle and never came out." It seems from your website that he may have been with Lt. Stibbe's platoon.

After exchanging several emails, Richard also told me:

Steve,

Thank you so much for the information you sent me. I have shared the detail you provided with my Dad and in his words you have helped clarify the family myth of what happened to James. My Dad was born in 1951 and so only ever knew the story as told by his grandparents and his own father (James’ younger brother). Given the lack of clarity around the death at the time, it was accepted by the family that James died in the Far East, but no search for anymore information ever took place. Dad is now going to reach out to his cousins to see if there is a photograph of James, or a way to get more information and if the family still have any letters or similar items. They are also going to see if they can confirm the next of kin, to allow the family to request his Army Service records.

Many thanks again, Richard.

After the war, Pte. Piercy's body was never recovered and no grave was ever found. For this reason he is remembered upon the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery which is located on the northern outskirts of the capital city. Seen below are some images in relation to this part of the story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

3781567 Corporal George Litherland was the son of John and Sarah Litherland and the husband of Letitia Litherland, from Crumpsall in Lancashire. He travelled to India with the original 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment aboard the troopship 'Oronsay' in December 1941. George was posted to 5 Column in July 1942 and became a Section Commander in 7 Rifle Platoon under the overall command of Lieutenant Philip Stibbe.

George was a barber in civilian life and gave many a haircut to his comrades in 5 Column during their time in India and Burma. Major Fergusson called upon Litherland's beard trimming skills just after the column had made their outward crossing of the Irrawaddy River in early March 1943. From his book, Beyond the Chindwin:

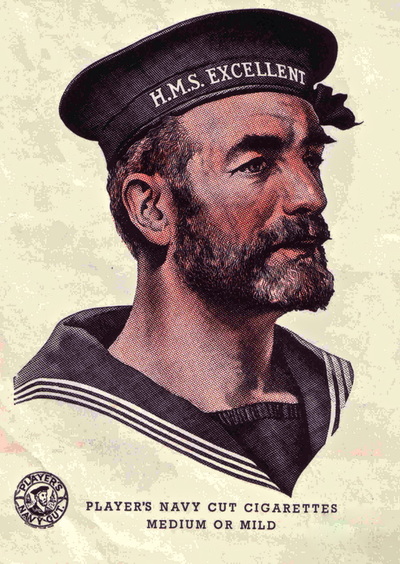

We observed the next morning as somewhat of a holiday. I spent a portion of the day having my hair cut and my beard trimmed by Corporal Litherland, an ex-barber; I told him to take as his model, the sailor on the Player's Cigarette packet and the effect was much admired by my more sycophantic colleagues.

Platoon Commander Philip Stibbe remembered his first impression of George Litherland, which is recorded in his own book entitled, Return via Rangoon:

My Section Commanders were, Corporal Litherland, Corporal Berry and another Lance-Corporal whom I later replaced. I am afraid these men must have found me very hard to please and it must sometimes have seemed as if I expended all my surplus spleen upon them. However, in spite of several stormy periods during training in India, they never let me down in Burma. Their conduct in action exceeded my wildest hopes and the same may be said of all my platoon.

Later on in his excellent book, Philip Stibbe describes his platoon's involvement in 5 Column's battle at the village of Hintha:

We did not have to wait many seconds before machine-gun fire started from somewhere down the left fork of the "T" junction; the Major told me to take my platoon in with the bayonet. My platoon were in threes behind me, facing down the the track in the direction of the firing. It was impossible to see much in the dark, but there was no time to waste, so I shouted "Bayonets" and told Corporal Litherland and the left-hand section to deal with anything on the left of the track and Corporal Handley and Corporal Berry with the right-hand section to deal with anything on the right.

Corporal Dunn was in the centre immediately behind me with his section and I the told him to follow me and deal with anything immediately in front. All this took only a moment; the Major shouted "Good luck", I gave the word and we doubled forward. It is difficult to realise what is happening in the heat of battle and even more difficult to give a coherent account of it the afterwards, but I remember seeing something move under a house on our left as we went forward and firing at it with my revolver. Then machine-gun fire seemed to come from several directions in front of us and I hurled a grenade at the nearest gun and we got down while it went off.

I was standing up to go forward again when something knocked me down and I felt a pain in my left shoulder-blade. The platoon rushed on past me. What was happening in the darkness ahead I could not tell but there was a confused medley of shots, screams, shouts and explosions.

The firing continued intermittently and the Major sent Jim Harman and the Commando Platoon to try to attack the Japs down the little track we had seen leading off to the left. Alec Macdonald went with them. While this was being done, the Major came over to speak to Corporal Litherland and me but he had hardly begun when a Jap grenade landed beside us. The Major only just had time to throw himself on the ground before it went off; he was on his feet again in a moment and I did not know till long afterwards that he had been hit in the hip by a fragment. Corporal Litherland was wounded in the head and arm but not as badly as a nearby private soldier who had a terrible head wound and started begging me to shoot him to put him out of his agony.

Fortunately Doc Aird came up with some morphia. By some miracle, although the grenade had landed scarcely an arm's length from me, I was untouched. By this time I was so covered in blood that the Major was convinced I had been hit again. Meanwhile the Commandos had put in their attack down the little track and we were all stunned when the word came back that Alec Macdonald, who had led them in, had been killed with Private Fuller. Jim Harman, who was with him, had been hit in the head and arm but he and Sergeant Pester went on with their men and cleared the track.

The firing now flared up again in our direction, but my platoon, who had remained calm and steady throughout, only fired when they saw a definite target. It was during the burst of firing that Doc Aird came up with one of his orderlies and dressed my wound. Shots were whistling just over their heads and I offered to move under cover while they did it, but they carried on where they were as calmly as if they had been in a hospital ward. The bullet had gone in through my chest just below my left collar bone, leaving only a very small hole which I had not noticed; the hole at the back where it came out was considerably larger and it was from this that I was losing all the blood.

We were safe at the "T" junction as long as it was dark, but it would have been an exposed position by daylight and dawn was breaking. We did not know how many Japs we had killed but it was obvious that their casualties had been far heavier than ours. I was not able to check up on my platoon's casualties but I discovered afterwards that we had lost Corporal Handley, Corporal Berry, Lance-Corporal Dunn and Private Cobb, while Corporal Litherland and one or two others had been wounded. The news then came that a way had been found through the jungle at the side of the track, so the Major ordered Brookes to blow the second dispersal call on his bugle. This was the signal for the column to split up into groups which were then to make for the pre-arranged rendezvous.

George was a barber in civilian life and gave many a haircut to his comrades in 5 Column during their time in India and Burma. Major Fergusson called upon Litherland's beard trimming skills just after the column had made their outward crossing of the Irrawaddy River in early March 1943. From his book, Beyond the Chindwin:

We observed the next morning as somewhat of a holiday. I spent a portion of the day having my hair cut and my beard trimmed by Corporal Litherland, an ex-barber; I told him to take as his model, the sailor on the Player's Cigarette packet and the effect was much admired by my more sycophantic colleagues.

Platoon Commander Philip Stibbe remembered his first impression of George Litherland, which is recorded in his own book entitled, Return via Rangoon:

My Section Commanders were, Corporal Litherland, Corporal Berry and another Lance-Corporal whom I later replaced. I am afraid these men must have found me very hard to please and it must sometimes have seemed as if I expended all my surplus spleen upon them. However, in spite of several stormy periods during training in India, they never let me down in Burma. Their conduct in action exceeded my wildest hopes and the same may be said of all my platoon.

Later on in his excellent book, Philip Stibbe describes his platoon's involvement in 5 Column's battle at the village of Hintha:

We did not have to wait many seconds before machine-gun fire started from somewhere down the left fork of the "T" junction; the Major told me to take my platoon in with the bayonet. My platoon were in threes behind me, facing down the the track in the direction of the firing. It was impossible to see much in the dark, but there was no time to waste, so I shouted "Bayonets" and told Corporal Litherland and the left-hand section to deal with anything on the left of the track and Corporal Handley and Corporal Berry with the right-hand section to deal with anything on the right.

Corporal Dunn was in the centre immediately behind me with his section and I the told him to follow me and deal with anything immediately in front. All this took only a moment; the Major shouted "Good luck", I gave the word and we doubled forward. It is difficult to realise what is happening in the heat of battle and even more difficult to give a coherent account of it the afterwards, but I remember seeing something move under a house on our left as we went forward and firing at it with my revolver. Then machine-gun fire seemed to come from several directions in front of us and I hurled a grenade at the nearest gun and we got down while it went off.

I was standing up to go forward again when something knocked me down and I felt a pain in my left shoulder-blade. The platoon rushed on past me. What was happening in the darkness ahead I could not tell but there was a confused medley of shots, screams, shouts and explosions.

The firing continued intermittently and the Major sent Jim Harman and the Commando Platoon to try to attack the Japs down the little track we had seen leading off to the left. Alec Macdonald went with them. While this was being done, the Major came over to speak to Corporal Litherland and me but he had hardly begun when a Jap grenade landed beside us. The Major only just had time to throw himself on the ground before it went off; he was on his feet again in a moment and I did not know till long afterwards that he had been hit in the hip by a fragment. Corporal Litherland was wounded in the head and arm but not as badly as a nearby private soldier who had a terrible head wound and started begging me to shoot him to put him out of his agony.

Fortunately Doc Aird came up with some morphia. By some miracle, although the grenade had landed scarcely an arm's length from me, I was untouched. By this time I was so covered in blood that the Major was convinced I had been hit again. Meanwhile the Commandos had put in their attack down the little track and we were all stunned when the word came back that Alec Macdonald, who had led them in, had been killed with Private Fuller. Jim Harman, who was with him, had been hit in the head and arm but he and Sergeant Pester went on with their men and cleared the track.

The firing now flared up again in our direction, but my platoon, who had remained calm and steady throughout, only fired when they saw a definite target. It was during the burst of firing that Doc Aird came up with one of his orderlies and dressed my wound. Shots were whistling just over their heads and I offered to move under cover while they did it, but they carried on where they were as calmly as if they had been in a hospital ward. The bullet had gone in through my chest just below my left collar bone, leaving only a very small hole which I had not noticed; the hole at the back where it came out was considerably larger and it was from this that I was losing all the blood.

We were safe at the "T" junction as long as it was dark, but it would have been an exposed position by daylight and dawn was breaking. We did not know how many Japs we had killed but it was obvious that their casualties had been far heavier than ours. I was not able to check up on my platoon's casualties but I discovered afterwards that we had lost Corporal Handley, Corporal Berry, Lance-Corporal Dunn and Private Cobb, while Corporal Litherland and one or two others had been wounded. The news then came that a way had been found through the jungle at the side of the track, so the Major ordered Brookes to blow the second dispersal call on his bugle. This was the signal for the column to split up into groups which were then to make for the pre-arranged rendezvous.

We know already from Sgt. Whitehead's witness statement, that Corporal Litherland was led away from Hintha village by James Piercy and Leslie Hardy. However, before we move on with the story, here is how Major Fergusson remembered those final few minutes at Hintha, just before he himself was wounded by a Japanese grenade:

Philippe (Stibbe) was hit in the shoulder; not badly, but he had lost a good deal of blood. I was talking to him and Corporal Litherland, who had also been hit: the two of them were at the foot of a tree on the right of the track up which we had come, just at the junction. Suddenly there was a rush of Japs up the track from the right, where Peter Dorans was, and two or three grenades came flaming through the air: the Japs have a glowing fuse on their grenades, very useful in a night action to those at whom they are thrown.

One rolled to within a few yards of me, and I flung myself down behind a dark shadow which I took to be a fold in the ground; I realised only too clearly as soon as I was down that it was nothing more substantial than the shadow of a tree in the moonlight. The thing went off, and I felt a hot, sharp pain in the bone of my hip. At that moment there was a series of loud explosions: Peter, from the ditch where he was lying, had rolled half a dozen grenades among the Japs. Where I had seen them dimly in the moonlight and shadows, there was now a heap of writhing bodies, into which Peter was emptying his rifle. There was no further attack from that side.

I hopped to my feet and was overjoyed to find I was all right and able to walk. But poor Philippe had been hit again, this time in the small of the back; so had Corporal Litherland, and a third man who had been groaning and was now dead. Philippe could still walk, and I told him to go back out of the way down the column. He walked a couple of yards, then said- "Blast, I've forgotten my pack," picked it up and went off. This was the last time I saw him. Litherland also, with some help, was able to walk away down the track.

George Litherland was listed as missing in action on the 28th March 1943, with an additional note that he was known to be wounded. It seems likely, that he was captured sometime (perhaps a few days) after the ambush on the outskirts of Hintha. I say this simply because I do not think that the Japanese would have taken any prisoners during the actual engagement on the 28th March, as this was certainly not their usual behaviour in the course of battle, especially with men who were already wounded or injured. The majority of the men separated from the main body of 5 Column during the ambush had turned around and headed east towards the Shweli River. Many of these bumped into Major Gilkes and the soldiers of 7 Column on the 3rd April close to the village of Ingyinbin. I doubt that Corporal Litherland was amongst these men.

The Japanese had by now gathered together a fair number of Chindit prisoners of war and were slowly moving these men from their various places of capture to more central collection points. In his book, Return via Rangoon, Philip Stibbe, himself now a prisoner, recalls meeting up with a large number of men from 5 Column including George Litherland at one such location close to the Shweli River. Not long after this meeting the entire group of POW's, together with Lt. Stibbe were assembled at the old jail in the Burmese town of Bhamo. After a short stay at Bhamo, the men were sent next to a larger concentration camp in the hill station town of Maymyo, before eventually being sent down by rail to Rangoon Central Jail. To read more about the experiences of Chindit POW's, please click on the following link: Chindit POW's

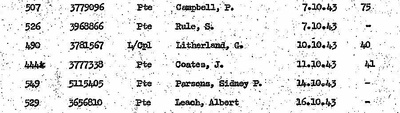

George Litherland died inside Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on the 10th October 1943, it is not known how or why he perished. Whilst a prisoner of war, George had been given the POW number 490. He was originally buried in grave no. 40 at the English Cantonment Cemetery, located in the eastern sector of the city, close to the Royal Lakes. After the war, all the British POW graves in the Cantonment Cemetery were re-interred at the newly constructed Rangoon War Cemetery, situated closer to the city docks.

Seen below are some images in regards to the story of Corporal George Litherland. Please click on any image to bring forward on the page.

Philippe (Stibbe) was hit in the shoulder; not badly, but he had lost a good deal of blood. I was talking to him and Corporal Litherland, who had also been hit: the two of them were at the foot of a tree on the right of the track up which we had come, just at the junction. Suddenly there was a rush of Japs up the track from the right, where Peter Dorans was, and two or three grenades came flaming through the air: the Japs have a glowing fuse on their grenades, very useful in a night action to those at whom they are thrown.

One rolled to within a few yards of me, and I flung myself down behind a dark shadow which I took to be a fold in the ground; I realised only too clearly as soon as I was down that it was nothing more substantial than the shadow of a tree in the moonlight. The thing went off, and I felt a hot, sharp pain in the bone of my hip. At that moment there was a series of loud explosions: Peter, from the ditch where he was lying, had rolled half a dozen grenades among the Japs. Where I had seen them dimly in the moonlight and shadows, there was now a heap of writhing bodies, into which Peter was emptying his rifle. There was no further attack from that side.

I hopped to my feet and was overjoyed to find I was all right and able to walk. But poor Philippe had been hit again, this time in the small of the back; so had Corporal Litherland, and a third man who had been groaning and was now dead. Philippe could still walk, and I told him to go back out of the way down the column. He walked a couple of yards, then said- "Blast, I've forgotten my pack," picked it up and went off. This was the last time I saw him. Litherland also, with some help, was able to walk away down the track.

George Litherland was listed as missing in action on the 28th March 1943, with an additional note that he was known to be wounded. It seems likely, that he was captured sometime (perhaps a few days) after the ambush on the outskirts of Hintha. I say this simply because I do not think that the Japanese would have taken any prisoners during the actual engagement on the 28th March, as this was certainly not their usual behaviour in the course of battle, especially with men who were already wounded or injured. The majority of the men separated from the main body of 5 Column during the ambush had turned around and headed east towards the Shweli River. Many of these bumped into Major Gilkes and the soldiers of 7 Column on the 3rd April close to the village of Ingyinbin. I doubt that Corporal Litherland was amongst these men.

The Japanese had by now gathered together a fair number of Chindit prisoners of war and were slowly moving these men from their various places of capture to more central collection points. In his book, Return via Rangoon, Philip Stibbe, himself now a prisoner, recalls meeting up with a large number of men from 5 Column including George Litherland at one such location close to the Shweli River. Not long after this meeting the entire group of POW's, together with Lt. Stibbe were assembled at the old jail in the Burmese town of Bhamo. After a short stay at Bhamo, the men were sent next to a larger concentration camp in the hill station town of Maymyo, before eventually being sent down by rail to Rangoon Central Jail. To read more about the experiences of Chindit POW's, please click on the following link: Chindit POW's

George Litherland died inside Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on the 10th October 1943, it is not known how or why he perished. Whilst a prisoner of war, George had been given the POW number 490. He was originally buried in grave no. 40 at the English Cantonment Cemetery, located in the eastern sector of the city, close to the Royal Lakes. After the war, all the British POW graves in the Cantonment Cemetery were re-interred at the newly constructed Rangoon War Cemetery, situated closer to the city docks.

Seen below are some images in regards to the story of Corporal George Litherland. Please click on any image to bring forward on the page.

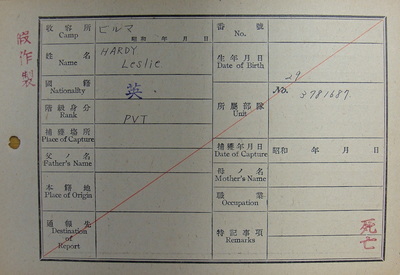

Pte. 3781687 Leslie Hardy travelled to India with the original 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment aboard the troopship 'Oronsay' in December 1941. He was posted to 5 Column and began Chindit training in late July 1942. Once again, we already know that Leslie Hardy was with Pte. Piercy and Corporal Litherland after the engagement at Hintha village and that he too was reported missing in action the same day, the 28th March 1943. It is known that Pte. Hardy also fell into Japanese hands shortly after the ambush on the outskirts of the village, but, much like George Litherland, it is not known how or where he was captured.

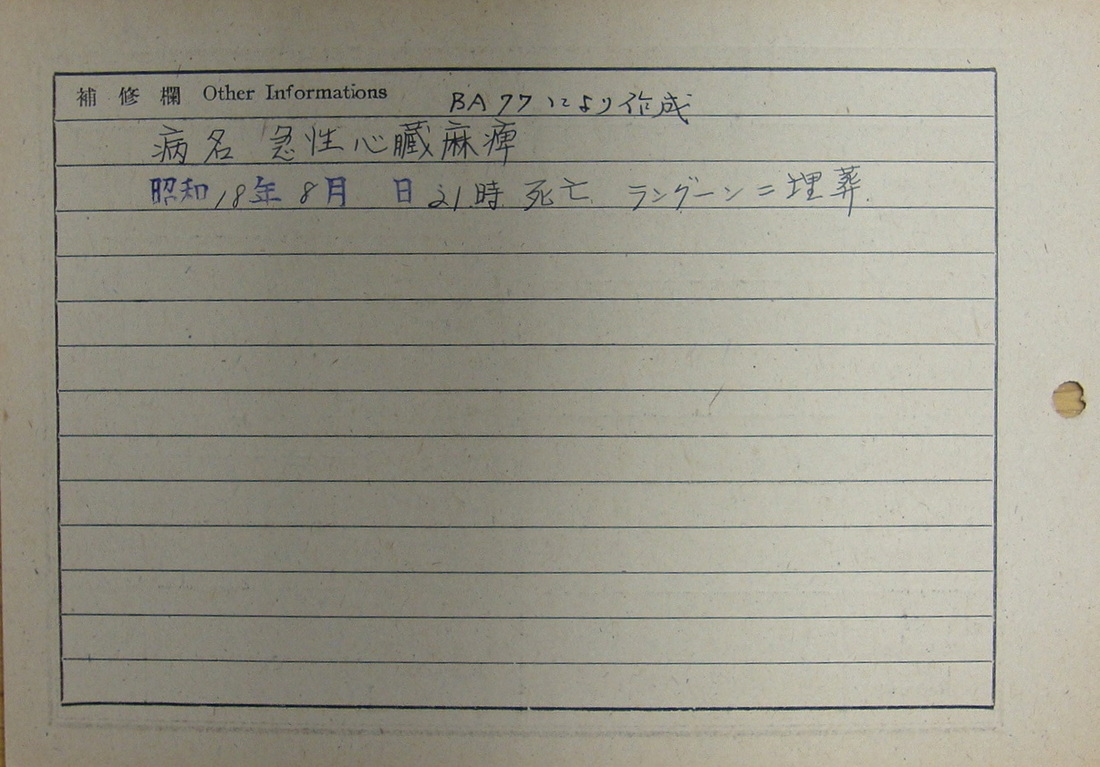

The story of what happened to Leslie Hardy is both troubling and intriguing and centres around a discrepancy regarding his recorded date of death. I believe we can be fairly confident that Leslie perished whilst a prisoner of war inside the confines of Rangoon Jail, but how he died and on what date remains unclear. He does not feature on the extensive listings for those men who died inside the jail during the years of Japanese occupation (1942-45). The only piece of documentary evidence for his time as a prisoner of war is his POW index card and this is extremely scant in information. The explanation entered in Japanese Kanji characters on the reverse side of his card, reads that Pte. Hardy died from heart failure in August 1943 and that he was buried in Rangoon.

The confusion in regards to Leslie Hardy's correct date of death, centres around his particulars as documented by the CWGC on their website and presumably in their official records at Maidenhead. They show his date of death as 30th April 1945. This to me is an unusual date in relation to the narrative for men held at Rangoon Jail, as by the date in question all POW's from the jail were no longer in Japanese hands. It is of course quite possible that Pte. Hardy did perish around this time, but in my experience in researching these men this seems unlikely.

So, what did happen to Pte. Hardy in Rangoon Jail? Sadly, all the available evidence points to a rather sinister and tragic end for this particular Chindit. Once again we return to the book, Return via Rangoon, written by 5 Column officer Philip Stibbe:

One incident in our first few months at Rangoon was particularly tragic. The Japanese Medical Officer at Maymyo had been using some of our men as human guinea pigs, injecting germs into them to see the results. One party of prisoners arrived from Maymyo in a terrible state. They told us that they had been injected with malaria germs, nearly all of them died soon after arrival. One of them went delirious and the following day he went missing at morning roll-call.

We managed to conceal his absence from the Japs, but, when a thorough search of the compound failed to reveal any trace of him, we thought it was obviously better to tell the Japs that he had gone rather than let them discover it for themselves. Somehow in his delirium, the man had got out of the compound and out of the jail. Nobody ever found out how he did this. For a white man to try to escape from Rangoon was sheer madness. The Burmans in that area were mostly so frightened of the Japs that, even if they did not betray him, they would certainly not assist him; besides, the nearest Allied territory was thousands of miles away.

As soon as the Japs were told that the man was missing they took drastic action. Our senior officer, a New Zealand Flight Lieutenant, was sick at that time, but the acting senior officer and various men who the Japs quite wrongly suspected of assisting the escape were clapped into solitary confinement. The rest of us were locked in our rooms and spent the time wondering what was going to happen. On the evening of the second day the cooks were allowed to prepare a meal for us; the following morning we were paraded in the compound in front of the Japanese Commandant.

The escaped man was brought in; the poor fellow had obviously no idea what was happening. The Commandant announced that he had been brought back to the jail by Burmans and that he would receive the severest punishment. He was then led out and none of us ever saw him again. As for the rest of us, the Commandant said that he would be lenient and that we would carry on as usual provided that we promised not to try to escape. We were all required to sign a document to this effect and, after some discussion amongst ourselves, we did so. We felt that, after all, a promise extracted by force by one's enemies is not binding and the chance of a good opportunity of escape presenting itself seemed very remote.

After a few days, those who had been sent to solitary confinement came back, considerably shaken by their ordeal. The Japanese guard commander who had failed to notice that there was a man missing at morning roll call was severely punished and he, in his turn, retaliated on the British officer who had been in charge that day. The officer came back from the cells with terrible bruises on his face where he had been beaten up. He was never the same after this incident and, many months afterwards, he died of heart trouble. During the days when we had been locked up, the sick POW's received no medical attention and this probably hastened the end in many cases.

Lt. Stibbe was not the only man to remark upon this terrible incident from his days inside Rangoon Jail, with the episode verified by at least five other Chindits. I have also been told this story from a first-hand witness to the incident, although it was agreed by the officers and men at the time, never to relay such information back to any of the casualties families in order to protect them from hearing such unpalatable and disturbing truths. The stated cause of death on Pte. Hardy's POW card (heart failure), I believe is a continuation of this promise made by the men of Rangoon Jail not to unduly upset any next of kin.

To read more about the ill-treatment of Chindit prisoners of war, please click on the following link: Japanese Experimentation on POW's

The story of what happened to Leslie Hardy is both troubling and intriguing and centres around a discrepancy regarding his recorded date of death. I believe we can be fairly confident that Leslie perished whilst a prisoner of war inside the confines of Rangoon Jail, but how he died and on what date remains unclear. He does not feature on the extensive listings for those men who died inside the jail during the years of Japanese occupation (1942-45). The only piece of documentary evidence for his time as a prisoner of war is his POW index card and this is extremely scant in information. The explanation entered in Japanese Kanji characters on the reverse side of his card, reads that Pte. Hardy died from heart failure in August 1943 and that he was buried in Rangoon.

The confusion in regards to Leslie Hardy's correct date of death, centres around his particulars as documented by the CWGC on their website and presumably in their official records at Maidenhead. They show his date of death as 30th April 1945. This to me is an unusual date in relation to the narrative for men held at Rangoon Jail, as by the date in question all POW's from the jail were no longer in Japanese hands. It is of course quite possible that Pte. Hardy did perish around this time, but in my experience in researching these men this seems unlikely.

So, what did happen to Pte. Hardy in Rangoon Jail? Sadly, all the available evidence points to a rather sinister and tragic end for this particular Chindit. Once again we return to the book, Return via Rangoon, written by 5 Column officer Philip Stibbe:

One incident in our first few months at Rangoon was particularly tragic. The Japanese Medical Officer at Maymyo had been using some of our men as human guinea pigs, injecting germs into them to see the results. One party of prisoners arrived from Maymyo in a terrible state. They told us that they had been injected with malaria germs, nearly all of them died soon after arrival. One of them went delirious and the following day he went missing at morning roll-call.

We managed to conceal his absence from the Japs, but, when a thorough search of the compound failed to reveal any trace of him, we thought it was obviously better to tell the Japs that he had gone rather than let them discover it for themselves. Somehow in his delirium, the man had got out of the compound and out of the jail. Nobody ever found out how he did this. For a white man to try to escape from Rangoon was sheer madness. The Burmans in that area were mostly so frightened of the Japs that, even if they did not betray him, they would certainly not assist him; besides, the nearest Allied territory was thousands of miles away.

As soon as the Japs were told that the man was missing they took drastic action. Our senior officer, a New Zealand Flight Lieutenant, was sick at that time, but the acting senior officer and various men who the Japs quite wrongly suspected of assisting the escape were clapped into solitary confinement. The rest of us were locked in our rooms and spent the time wondering what was going to happen. On the evening of the second day the cooks were allowed to prepare a meal for us; the following morning we were paraded in the compound in front of the Japanese Commandant.

The escaped man was brought in; the poor fellow had obviously no idea what was happening. The Commandant announced that he had been brought back to the jail by Burmans and that he would receive the severest punishment. He was then led out and none of us ever saw him again. As for the rest of us, the Commandant said that he would be lenient and that we would carry on as usual provided that we promised not to try to escape. We were all required to sign a document to this effect and, after some discussion amongst ourselves, we did so. We felt that, after all, a promise extracted by force by one's enemies is not binding and the chance of a good opportunity of escape presenting itself seemed very remote.

After a few days, those who had been sent to solitary confinement came back, considerably shaken by their ordeal. The Japanese guard commander who had failed to notice that there was a man missing at morning roll call was severely punished and he, in his turn, retaliated on the British officer who had been in charge that day. The officer came back from the cells with terrible bruises on his face where he had been beaten up. He was never the same after this incident and, many months afterwards, he died of heart trouble. During the days when we had been locked up, the sick POW's received no medical attention and this probably hastened the end in many cases.

Lt. Stibbe was not the only man to remark upon this terrible incident from his days inside Rangoon Jail, with the episode verified by at least five other Chindits. I have also been told this story from a first-hand witness to the incident, although it was agreed by the officers and men at the time, never to relay such information back to any of the casualties families in order to protect them from hearing such unpalatable and disturbing truths. The stated cause of death on Pte. Hardy's POW card (heart failure), I believe is a continuation of this promise made by the men of Rangoon Jail not to unduly upset any next of kin.

To read more about the ill-treatment of Chindit prisoners of war, please click on the following link: Japanese Experimentation on POW's

After the prisoners held at Rangoon Jail were officially liberated in early May 1945, they were interrogated by a team of Army and RAF investigators who took down witness statements from the men in relation to the death of fellow POW's and the treatment they had received from their Japanese captors. When questioned about attempted escapes from the jail, several men recounted the story of Leslie Hardy. Here is how the investigation team noted these accounts in their final report (AIR38/80):

Instances of escape at Rangoon.

There is only one example of the escape of a white POW from the jail and this was the case of a British Other Rank who had been sick with malaria, and who, it is believed was delirious. Some time in June or July 1943 he walked out at night with his night clothes on and no kit. There is a prevalent belief that he had been used as a 'guinea pig' by Japanese doctors at Maymyo and that he had been subjected to a series of injections and observations, which had left him a chronic victim of malaria. There is however, no direct evidence of this.

The escaper was re-captured some 36 hours later, some twelve miles from the jail and brought back. Reprisals were taken against the POW Block Commander, against the POW sleeping next to the escaper and against prisoners in general. Reprisals in the first instance took the form of beatings. The Japanese authorities placed the escaper in solitary confinement with its attendant privations and stated that he would suffer the highest punishment. He was removed after a time and was never seen subsequently, although there is one report that the Japanese stated he had died of malaria.

The prisoners were given little water for a time, with the resultant deaths referred to elsewhere in this report. They were also warned that if such a thing happened again, very serious measures would be taken against them.

There can be no doubt that the report relates to Leslie Hardy, although no names are ever used within the investigation document, especially when referring to uncorroborated evidence or statements given by third parties.

According to his POW index card, Leslie Hardy was buried in Rangoon, presumably this refers in the first instance to the English Cantonment Cemetery located near the Royal Lakes. After the war, all the British POW graves in the Cantonment Cemetery were re-interred at the newly constructed Rangoon War Cemetery, situated closer to the city docks. At Rangoon War Cemetery, Leslie has one of the graves (9.A.9) that forms part of a Special Memorial. These graves have the words 'buried near this spot' written on the memorial plaque, which refers to more than sixty casualties whose graves could not be precisely located or identified when the re-burials took place.

To conclude this story, seen below are some more images in relation to Leslie Hardy and his time in Burma. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Instances of escape at Rangoon.

There is only one example of the escape of a white POW from the jail and this was the case of a British Other Rank who had been sick with malaria, and who, it is believed was delirious. Some time in June or July 1943 he walked out at night with his night clothes on and no kit. There is a prevalent belief that he had been used as a 'guinea pig' by Japanese doctors at Maymyo and that he had been subjected to a series of injections and observations, which had left him a chronic victim of malaria. There is however, no direct evidence of this.

The escaper was re-captured some 36 hours later, some twelve miles from the jail and brought back. Reprisals were taken against the POW Block Commander, against the POW sleeping next to the escaper and against prisoners in general. Reprisals in the first instance took the form of beatings. The Japanese authorities placed the escaper in solitary confinement with its attendant privations and stated that he would suffer the highest punishment. He was removed after a time and was never seen subsequently, although there is one report that the Japanese stated he had died of malaria.

The prisoners were given little water for a time, with the resultant deaths referred to elsewhere in this report. They were also warned that if such a thing happened again, very serious measures would be taken against them.

There can be no doubt that the report relates to Leslie Hardy, although no names are ever used within the investigation document, especially when referring to uncorroborated evidence or statements given by third parties.

According to his POW index card, Leslie Hardy was buried in Rangoon, presumably this refers in the first instance to the English Cantonment Cemetery located near the Royal Lakes. After the war, all the British POW graves in the Cantonment Cemetery were re-interred at the newly constructed Rangoon War Cemetery, situated closer to the city docks. At Rangoon War Cemetery, Leslie has one of the graves (9.A.9) that forms part of a Special Memorial. These graves have the words 'buried near this spot' written on the memorial plaque, which refers to more than sixty casualties whose graves could not be precisely located or identified when the re-burials took place.

To conclude this story, seen below are some more images in relation to Leslie Hardy and his time in Burma. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, September 2016.