Pte. Thomas Patrick Byrne

Thomas Patrick Byrne.

Thomas Patrick Byrne.

In the stories related to the exploits of Column 5 in 1943, the disappearance of Pte. Tommy Byrne stands out as one of the great mysteries of that year. He had always been a reliable and responsible member of the Column and had performed his duties well, both in training back in India and in the early weeks of the unit's activities in Burma.

His Platoon Commander Lieutenant Philip Stibbe described him in the following way:

"Pte. 3779403 Thomas Byrne was a larger than life character in my platoon, always seeing the funny side of most situations. The strongly built red-head had been a wrestler in his formative years back home in Liverpool, and his manual strength was a great plus for us in the jungle, especially when trying to deal with the many obstacles Burma had to throw at us.

With all his soldiering skills it has always been a mystery to me why he would end up getting lost from the platoon the way he did. But then in turn, there was no surprise, when I ended up entering the gates of Rangoon Jail, to see his beaming white freckled face looking back at me. He was probably the strongest personality amongst the men and I could usually gauge the mood of the rest of the platoon by his. Apart from a very occasional burst of temper, for which he always subsequently apologised, he was cheerful and a tremendous worker. I often thanked my lucky stars for him."

There are two different reasons stated for why Tommy left the column line on 18th March 1943. The official column diary refers to the incident thus:

"18 March 1943, 16.00 hours. Spotted by enemy recce plane circling at 1000 feet. Bivouaced on the north east slope of the Hmaingdaing Taung at 19.00 hours. Marching continued southward. Very little water, and necessary to dig water holes in the nearby chaungs and wait until the water seeped through. Lance Corporal Walmsley and Pte. Byrne are reported missing from the line of march."

The suggestion from the diary is that the two above mentioned men had gone off to search for more easily accessible water and that they had both become lost and could not find their way back to the column. From subsequent, and more first hand accounts, this turns out not to be the case at all. Firstly, here is what the Column 5 Commander Bernard Fergusson remembered about that particular time in March 1943. From his book 'Wild Green Earth' comes this quote:

"I lost three men altogether on the expedition, lost in the literal sense, that is on the line of march. The first was a private soldier (5627646 Pte. George Harry Gray) who was found to be missing after a midday halt: he was never heard of again. The second man (3780147 Lance Corporal Dennis Walmsley) was a man who walked out of the perimeter to fetch water from a waterhole a hundred yards away, and failed to return: he was probably lost, it was easy to lose your bearings even so close to the bivouac. The third (3779403 Pte. T.P. Byrne) I lost only one day later: he too nipped out of the column when it had moved only a short distance from the bivouac in search of some lost equipment, he never returned."

The author does not actually name the men in his book, but I have added their details to help identify who was who and what actually happened to them. Fergusson continues:

“Both the last two were lost in an area remote from villages and I am quite certain miles from any Japanese; yet both fell into enemy hands, the first after wandering for a day, the second after only 5 minutes. The first (Walmsley) died in Rangoon Jail, like most of the others; the second (Byrne) survived and it is from him that we know what happened.”

To read more about the fate of Lance Corporal Dennis Walmsley, please click on the link here: Dennis Walmsley (his is the fourth story on the page).

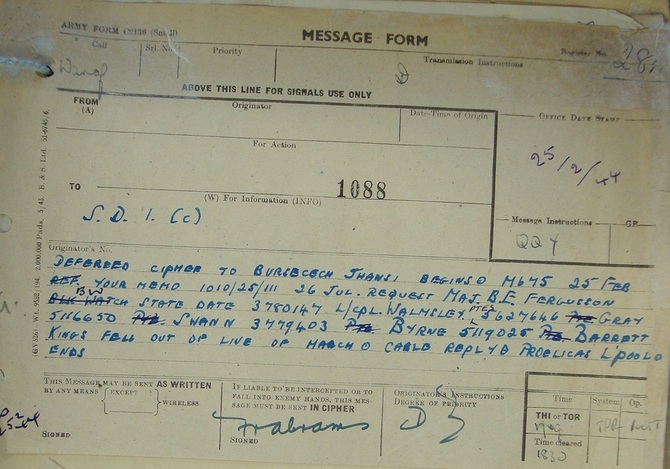

Below is a cipher message form, asking Major Fergusson to give a missing in action date for the undermentioned men and their disappearance from the line of march. It asks him to refer his reply to the investigation bureau that was set up at the Blue Coat School, ironically located in Liverpool. Ironic because the city, not surprisingly, was home for a very large number of the men who served on Operation Longcloth.

His Platoon Commander Lieutenant Philip Stibbe described him in the following way:

"Pte. 3779403 Thomas Byrne was a larger than life character in my platoon, always seeing the funny side of most situations. The strongly built red-head had been a wrestler in his formative years back home in Liverpool, and his manual strength was a great plus for us in the jungle, especially when trying to deal with the many obstacles Burma had to throw at us.

With all his soldiering skills it has always been a mystery to me why he would end up getting lost from the platoon the way he did. But then in turn, there was no surprise, when I ended up entering the gates of Rangoon Jail, to see his beaming white freckled face looking back at me. He was probably the strongest personality amongst the men and I could usually gauge the mood of the rest of the platoon by his. Apart from a very occasional burst of temper, for which he always subsequently apologised, he was cheerful and a tremendous worker. I often thanked my lucky stars for him."

There are two different reasons stated for why Tommy left the column line on 18th March 1943. The official column diary refers to the incident thus:

"18 March 1943, 16.00 hours. Spotted by enemy recce plane circling at 1000 feet. Bivouaced on the north east slope of the Hmaingdaing Taung at 19.00 hours. Marching continued southward. Very little water, and necessary to dig water holes in the nearby chaungs and wait until the water seeped through. Lance Corporal Walmsley and Pte. Byrne are reported missing from the line of march."

The suggestion from the diary is that the two above mentioned men had gone off to search for more easily accessible water and that they had both become lost and could not find their way back to the column. From subsequent, and more first hand accounts, this turns out not to be the case at all. Firstly, here is what the Column 5 Commander Bernard Fergusson remembered about that particular time in March 1943. From his book 'Wild Green Earth' comes this quote:

"I lost three men altogether on the expedition, lost in the literal sense, that is on the line of march. The first was a private soldier (5627646 Pte. George Harry Gray) who was found to be missing after a midday halt: he was never heard of again. The second man (3780147 Lance Corporal Dennis Walmsley) was a man who walked out of the perimeter to fetch water from a waterhole a hundred yards away, and failed to return: he was probably lost, it was easy to lose your bearings even so close to the bivouac. The third (3779403 Pte. T.P. Byrne) I lost only one day later: he too nipped out of the column when it had moved only a short distance from the bivouac in search of some lost equipment, he never returned."

The author does not actually name the men in his book, but I have added their details to help identify who was who and what actually happened to them. Fergusson continues:

“Both the last two were lost in an area remote from villages and I am quite certain miles from any Japanese; yet both fell into enemy hands, the first after wandering for a day, the second after only 5 minutes. The first (Walmsley) died in Rangoon Jail, like most of the others; the second (Byrne) survived and it is from him that we know what happened.”

To read more about the fate of Lance Corporal Dennis Walmsley, please click on the link here: Dennis Walmsley (his is the fourth story on the page).

Below is a cipher message form, asking Major Fergusson to give a missing in action date for the undermentioned men and their disappearance from the line of march. It asks him to refer his reply to the investigation bureau that was set up at the Blue Coat School, ironically located in Liverpool. Ironic because the city, not surprisingly, was home for a very large number of the men who served on Operation Longcloth.

Philip Stibbe recalls the loss of Pte. Byrne in his book 'Return via Rangoon', here is a paraphrased quote from the narrative:

"We were just setting out across the open paddy fields when a Jap plane appeared. We were caught right out in the open and it was obvious that the pilot had seen us by the way he circle round. Our only comfort was that when he saw us we looked as though we were heading east, whereas our real direction was south.

We did not find water that night and the next day there seemed little prospect of it. The country through which we marched consisted of rocky hills fairly thickly covered with teak trees. What little soil there was on top of the rocks was a curious red colour. The trees were not thick enough to protect us from the heat of the sun and our thirst was becoming acute by midday. We halted by a dry riverbed and, after digging several holes, managed to procure a little muddy water.

Occasions like this were a very good test of our water discipline; it demanded much self-control to wait the required period for the sterilising tablet to dissolve before taking a drink. The Burma Riflemen were extraordinarily skilful in finding the right place to dig for water. It was just one of the many things which we relied on them to do for us.

My platoon had acted as Perimeter platoon on the previous night so that we were marching at the back of the column. Shortly after setting off after the midday halt, a message came up to the front of the platoon to say that Private Byrne had gone back to the place where we had previously halted to collect some ammunition he had accidentally left there.

I sent Feeney (the platoon runner or messenger) back to Sergeant Thornborrow, who always marched in the rear of the platoon, with instructions to let me know as soon as Byrne had caught us up. He was one of my best men and he should have had no difficulty in following our trail, but somehow I felt uneasy about him. This feeling increased when he did not turn up at the first halt, and in the end I sent back Cpl. Berry and his section to look for him. We bivouaced that night by two small pools of water which just sufficed for the men and mules.

I reported to the Major and told him that Byrne was missing and that I had sent a section to look for him. He was justifiably angry with me for risking a whole section for the sake of one man, although he too had a very high opinion of Byrne. I told him that I felt sure that Cpl. Berry would find us again, but, as time proceeded, I became more and more gloomy.

By the time night was falling I was desperate and I was just setting out to look for Cpl. Berry myself when I met him leading his section into the bivouac. My joy at seeing him was tempered by the news that, although they had searched for several hours, they had failed to contact Pte. Byrne. Our wireless charging motor was running all that night and there was a faint chance that he might be guided to us by the sound of it, but when he had not appeared the next morning I gave up hope. He was alone, without map or compass, in a country where there was hardly any water and not a village of miles; I was not the only one who never expected to see him again."

In actual fact Thomas had been captured almost immediately on leaving the column line, it is possible that the Japanese had been tracking the unit for a number of days in an attempt to exact revenge for what the column had achieved at the Bonchaung Gorge.

Becoming a prisoner so early on in the campaign would mean that Thomas would have been held at most, if not all of the POW Camps frequented by the Chindits in 1943. Places like Bhamo, Kalaw and then the main concentration camp at Maymyo. He would also have been one of the first group of men to be sent to Rangoon Central Jail, which is where he was to meet Lieutenant Stibbe once more in late May. Judging by people's opinion of the man, it is not surprising that Thomas would be one of the very few Other ranked soldiers to survive his time as a POW in Rangoon. Sadly, the vast majority of the men captured on Operation Longcloth perished in Block 6 of the jail within the first few months, dying, mostly from a terrible mix of exhaustion, malnutrition and disease.

Pte. Byrne was captured on the 19th March 1943 and his official POW number in Rangoon Jail was 310. He was one of the 400 or so men chosen by the Japanese to be marched out of the jail in late April 1945. These men became known as the Pegu Marchers and had been selected by their captors to work on the famous 'Death Railway'. In actual fact the men never reached Siam and were freed by their Japanese guards in a small village called Waw situated near the Burmese town of Pegu. Not long after being officially released by the Japanese, they were picked up by the advancing 14th Army and their long period of suffering was now over.

Thomas, like so many of the other POW's found at Pegu, was flown out of Burma and sent for recuperation at one of the many British Military Hospitals located throughout India. Back home his family would have been waiting nervously for more news about their loved one. However, they had been more fortunate than most families at that time, having received the news that Thomas was possibly a prisoner of war from a newspaper article in the Liverpool Echo as early as 1944. Many of the Longcloth families, including my own Nan, did not receive any official notification of their man's whereabouts or fate until well after the war was over.

Here is a transcription of the short article found in the Liverpool Echo dated Saturday 21st October 1944:

"Private Thomas Patrick Byrne, aged 31 of 77 South Hill Road, Liverpool, who was reported in April last year as missing in the Indian theatre of war, is now posted as possibly a prisoner in Japanese hands. He has been in the Army since 1940 and was formerly employed by Crosville Motor Service Ltd."

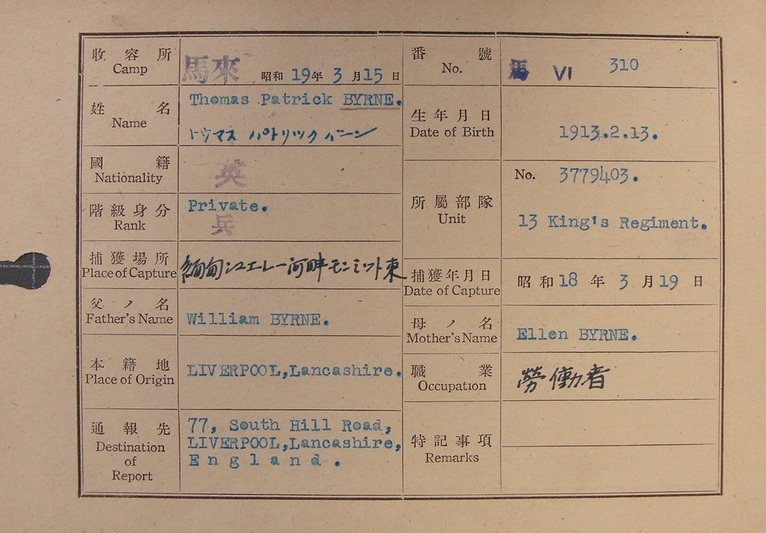

Seen below is the front face of Pte. Byrne's Japanese index card which collates details for his time as a prisoner of war. The card confirms amongst other information, his next of kin, their address, his place and date of capture and in the top right hand corner of the card, his official POW number, in Thomas's case 310. On the reverse of the card and written in Japanese characters there is usually more detailed information about the fate of the prisoner in question. On Byrne's card the single sentence relates to the Pegu Marchers and their eventual release at the village of Waw in early May 1945.

"We were just setting out across the open paddy fields when a Jap plane appeared. We were caught right out in the open and it was obvious that the pilot had seen us by the way he circle round. Our only comfort was that when he saw us we looked as though we were heading east, whereas our real direction was south.

We did not find water that night and the next day there seemed little prospect of it. The country through which we marched consisted of rocky hills fairly thickly covered with teak trees. What little soil there was on top of the rocks was a curious red colour. The trees were not thick enough to protect us from the heat of the sun and our thirst was becoming acute by midday. We halted by a dry riverbed and, after digging several holes, managed to procure a little muddy water.

Occasions like this were a very good test of our water discipline; it demanded much self-control to wait the required period for the sterilising tablet to dissolve before taking a drink. The Burma Riflemen were extraordinarily skilful in finding the right place to dig for water. It was just one of the many things which we relied on them to do for us.

My platoon had acted as Perimeter platoon on the previous night so that we were marching at the back of the column. Shortly after setting off after the midday halt, a message came up to the front of the platoon to say that Private Byrne had gone back to the place where we had previously halted to collect some ammunition he had accidentally left there.

I sent Feeney (the platoon runner or messenger) back to Sergeant Thornborrow, who always marched in the rear of the platoon, with instructions to let me know as soon as Byrne had caught us up. He was one of my best men and he should have had no difficulty in following our trail, but somehow I felt uneasy about him. This feeling increased when he did not turn up at the first halt, and in the end I sent back Cpl. Berry and his section to look for him. We bivouaced that night by two small pools of water which just sufficed for the men and mules.

I reported to the Major and told him that Byrne was missing and that I had sent a section to look for him. He was justifiably angry with me for risking a whole section for the sake of one man, although he too had a very high opinion of Byrne. I told him that I felt sure that Cpl. Berry would find us again, but, as time proceeded, I became more and more gloomy.

By the time night was falling I was desperate and I was just setting out to look for Cpl. Berry myself when I met him leading his section into the bivouac. My joy at seeing him was tempered by the news that, although they had searched for several hours, they had failed to contact Pte. Byrne. Our wireless charging motor was running all that night and there was a faint chance that he might be guided to us by the sound of it, but when he had not appeared the next morning I gave up hope. He was alone, without map or compass, in a country where there was hardly any water and not a village of miles; I was not the only one who never expected to see him again."

In actual fact Thomas had been captured almost immediately on leaving the column line, it is possible that the Japanese had been tracking the unit for a number of days in an attempt to exact revenge for what the column had achieved at the Bonchaung Gorge.

Becoming a prisoner so early on in the campaign would mean that Thomas would have been held at most, if not all of the POW Camps frequented by the Chindits in 1943. Places like Bhamo, Kalaw and then the main concentration camp at Maymyo. He would also have been one of the first group of men to be sent to Rangoon Central Jail, which is where he was to meet Lieutenant Stibbe once more in late May. Judging by people's opinion of the man, it is not surprising that Thomas would be one of the very few Other ranked soldiers to survive his time as a POW in Rangoon. Sadly, the vast majority of the men captured on Operation Longcloth perished in Block 6 of the jail within the first few months, dying, mostly from a terrible mix of exhaustion, malnutrition and disease.

Pte. Byrne was captured on the 19th March 1943 and his official POW number in Rangoon Jail was 310. He was one of the 400 or so men chosen by the Japanese to be marched out of the jail in late April 1945. These men became known as the Pegu Marchers and had been selected by their captors to work on the famous 'Death Railway'. In actual fact the men never reached Siam and were freed by their Japanese guards in a small village called Waw situated near the Burmese town of Pegu. Not long after being officially released by the Japanese, they were picked up by the advancing 14th Army and their long period of suffering was now over.

Thomas, like so many of the other POW's found at Pegu, was flown out of Burma and sent for recuperation at one of the many British Military Hospitals located throughout India. Back home his family would have been waiting nervously for more news about their loved one. However, they had been more fortunate than most families at that time, having received the news that Thomas was possibly a prisoner of war from a newspaper article in the Liverpool Echo as early as 1944. Many of the Longcloth families, including my own Nan, did not receive any official notification of their man's whereabouts or fate until well after the war was over.

Here is a transcription of the short article found in the Liverpool Echo dated Saturday 21st October 1944:

"Private Thomas Patrick Byrne, aged 31 of 77 South Hill Road, Liverpool, who was reported in April last year as missing in the Indian theatre of war, is now posted as possibly a prisoner in Japanese hands. He has been in the Army since 1940 and was formerly employed by Crosville Motor Service Ltd."

Seen below is the front face of Pte. Byrne's Japanese index card which collates details for his time as a prisoner of war. The card confirms amongst other information, his next of kin, their address, his place and date of capture and in the top right hand corner of the card, his official POW number, in Thomas's case 310. On the reverse of the card and written in Japanese characters there is usually more detailed information about the fate of the prisoner in question. On Byrne's card the single sentence relates to the Pegu Marchers and their eventual release at the village of Waw in early May 1945.

In the two accounts written by the officers commanding Thomas in 1943, it is suggested that he was a valuable source of information in relation to the fate of many of the men lost in one way or another on Operation Longcloth. He was certainly a great help in regard to those who had sadly perished in Rangoon Jail. This became apparent to me just recently (02/2013) when the daughter of another Chindit casualty (L/Cpl. James Ambrose) from 1943 told me this story:

"When you said that Paddy Byrne survived Rangoon Jail I began to see why my Mum had kept the newspaper cutting for so long. When I was about 5 or 6 years old, probably 1946/7, my Mum’s sister took me to the South End of Liverpool. All I can remember is going up some flights of stairs and into a flat. There was a man there in Army uniform who I didn’t know. Much later my Gran told me she had contacted his family after reading in the Echo that he was a prisoner of war. When he returned he wrote to her, hence the visit. He said he was a prisoner with my Dad and confirmed that he had died of malaria and malnutrition. Apparently when my Aunt met him she didn’t say who I was but when he saw me he said "She’s got to be Jim Ambrose’s daughter – she’s the image of him." My Mum never mentioned it to me and I never knew who he was."

From what we now know of Thomas Byrne and his helpful nature, it seems highly likely that he was the man in the flat, it seems even more probable, as both he and Lance Corporal Ambrose had been members of Column 5 in 1943.

My thanks go once more to Valerie Gornell, the daughter of James Ambrose, for the incredible help she has given me in regard to this story.

Update 09/03/2014

In mid-October last year (2013) I was thrilled to receive this email contact from Pete Curtis who lives in the United States:

Thanks for all of the obvious hard work you've put into this fascinating collection of information. Private Tommy Byrne, who you mention as being part of Lieutenant Stibbe's platoon, was my grandfather's only brother. He had no children of his own and therefore, his older brother's children and grandchildren looked upon their 'Uncle Tom' as almost a second dad or granddad.

The account given about his separation from the line and eventual capture contain a couple of variations from what Tom consistently shared with us until his death in 2000.

Firstly, when some ammunition was accidentally left at the site of the previous camp by a younger Private soldier, Tommy, as one of the more physically stronger members of a platoon, that was by now fatigued and short on water, was deemed the best candidate to head back, retrieve it, and then rejoin the line. Tommy did not leave the ammunition, but actually volunteered to go back for it.

Secondly, he was captured only after retrieving the ammo and beginning his return to the line. He spotted the Japanese closing in around him and attempted withdraw to safety, but was detected and eventually taken prisoner. From what Tom has always told us, he certainly wasn't captured five minutes after leaving the line. I hope this information will help clarify what really happened.

I hope to provide you with more information about Tom, but this may take a little time as I will need to do some digging around for pictures and so on. Thank you again.

The information given by Pete about his Great Uncle is exactly what this website is all about, that is, providing a place for families to add precise facts or details about their own Chindit soldier and his time in India and Burma.

Update 18/05/2016.

After receiving an email contact from the family of Tom Worthington, a new photograph of Tommy Byrne has come to light. Seen below is a photograph of eight POW's from Rangoon Jail, taken on the day they were liberated by the West Yorkshire Regiment, close to the Burmese town of Pegu. Tom Worthington is the tall man, seen third from the right as we look. In front of him (second right) is Tommy Byrne and I believe, although I cannot be 100% certain, that the man seen third from the left is Leon Frank.

"When you said that Paddy Byrne survived Rangoon Jail I began to see why my Mum had kept the newspaper cutting for so long. When I was about 5 or 6 years old, probably 1946/7, my Mum’s sister took me to the South End of Liverpool. All I can remember is going up some flights of stairs and into a flat. There was a man there in Army uniform who I didn’t know. Much later my Gran told me she had contacted his family after reading in the Echo that he was a prisoner of war. When he returned he wrote to her, hence the visit. He said he was a prisoner with my Dad and confirmed that he had died of malaria and malnutrition. Apparently when my Aunt met him she didn’t say who I was but when he saw me he said "She’s got to be Jim Ambrose’s daughter – she’s the image of him." My Mum never mentioned it to me and I never knew who he was."

From what we now know of Thomas Byrne and his helpful nature, it seems highly likely that he was the man in the flat, it seems even more probable, as both he and Lance Corporal Ambrose had been members of Column 5 in 1943.

My thanks go once more to Valerie Gornell, the daughter of James Ambrose, for the incredible help she has given me in regard to this story.

Update 09/03/2014

In mid-October last year (2013) I was thrilled to receive this email contact from Pete Curtis who lives in the United States:

Thanks for all of the obvious hard work you've put into this fascinating collection of information. Private Tommy Byrne, who you mention as being part of Lieutenant Stibbe's platoon, was my grandfather's only brother. He had no children of his own and therefore, his older brother's children and grandchildren looked upon their 'Uncle Tom' as almost a second dad or granddad.

The account given about his separation from the line and eventual capture contain a couple of variations from what Tom consistently shared with us until his death in 2000.

Firstly, when some ammunition was accidentally left at the site of the previous camp by a younger Private soldier, Tommy, as one of the more physically stronger members of a platoon, that was by now fatigued and short on water, was deemed the best candidate to head back, retrieve it, and then rejoin the line. Tommy did not leave the ammunition, but actually volunteered to go back for it.

Secondly, he was captured only after retrieving the ammo and beginning his return to the line. He spotted the Japanese closing in around him and attempted withdraw to safety, but was detected and eventually taken prisoner. From what Tom has always told us, he certainly wasn't captured five minutes after leaving the line. I hope this information will help clarify what really happened.

I hope to provide you with more information about Tom, but this may take a little time as I will need to do some digging around for pictures and so on. Thank you again.

The information given by Pete about his Great Uncle is exactly what this website is all about, that is, providing a place for families to add precise facts or details about their own Chindit soldier and his time in India and Burma.

Update 18/05/2016.

After receiving an email contact from the family of Tom Worthington, a new photograph of Tommy Byrne has come to light. Seen below is a photograph of eight POW's from Rangoon Jail, taken on the day they were liberated by the West Yorkshire Regiment, close to the Burmese town of Pegu. Tom Worthington is the tall man, seen third from the right as we look. In front of him (second right) is Tommy Byrne and I believe, although I cannot be 100% certain, that the man seen third from the left is Leon Frank.

Update 20/05/2016.

On receiving the above photograph I decided to re-contact Pete Curtis, the great-nephew of Tommy Byrne and alert him to the additional material now present on this page. Pete replied:

Thanks for the picture, Stephen. I have actually seen that shot before, but only on a poor photocopy of an old newspaper article. It was nice to see a clean copy of it. He was a real character, my Uncle Tom, who loved his family and loved life. He was such a part of the fabric of our family that it is still hard to believe he is no longer with us. He was a vibrant, sharp-minded character until the very end, when cancer finally took him from us in the year 2000.

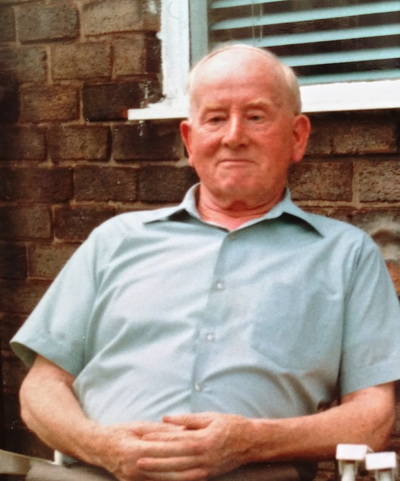

As I mentioned previously, I do not have any pictures of my Uncle Tom from his younger days. However, I have sent you two pictures from his later years. The first shows Tommy relaxing in the back garden of Mom and Dad's house in Liverpool and was taken in 1990. The other photograph is of me and Tommy, taken one Sunday afternoon in 1998.

I would like to thank Pete once again for his invaluable contributions to this story. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

On receiving the above photograph I decided to re-contact Pete Curtis, the great-nephew of Tommy Byrne and alert him to the additional material now present on this page. Pete replied:

Thanks for the picture, Stephen. I have actually seen that shot before, but only on a poor photocopy of an old newspaper article. It was nice to see a clean copy of it. He was a real character, my Uncle Tom, who loved his family and loved life. He was such a part of the fabric of our family that it is still hard to believe he is no longer with us. He was a vibrant, sharp-minded character until the very end, when cancer finally took him from us in the year 2000.

As I mentioned previously, I do not have any pictures of my Uncle Tom from his younger days. However, I have sent you two pictures from his later years. The first shows Tommy relaxing in the back garden of Mom and Dad's house in Liverpool and was taken in 1990. The other photograph is of me and Tommy, taken one Sunday afternoon in 1998.

I would like to thank Pete once again for his invaluable contributions to this story. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Copyright © Steve Fogden 2013/14.