Tom Worthington's Letter

Pte. Thomas Worthington.

Pte. Thomas Worthington.

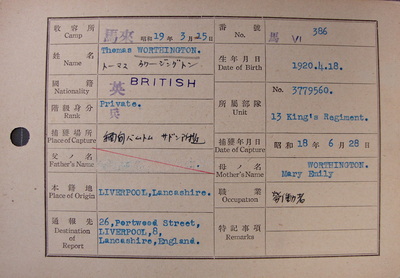

3779560 Pte. Thomas Worthington was born in Liverpool on the 18th April 1920. Before the war he lived with his mother Mary Emily Worthington at 26 Portwood Street in the Edge Hill district of Liverpool.

Thomas enlisted into the British Army and was posted to his home town Regiment, The King's Liverpool. He became part of the original 13th Battalion of the King's, taking up a place in C' Company at the Jordan Hill Barracks in Glasgow. In late December 1941 the battalion were selected for overseas duty and voyaged to India aboard the troopship 'Oronsay', leaving Liverpool Docks on the 8th of December.

In mid-June 1942 the battalion were given over to Brigadier Orde Wingate and began their Chindit training at the Saugor Camp in the Central Provinces of India. C' Company of the King's were re-designated as Chindit Column 7 under the overall command of Major Kenneth Daintry Gilkes. Kenneth Gilkes had joined the 13th King's in early 1941 from his original regiment, the North Staffordshire's.

Gilkes was a well liked and respected leader, who would never ask a man to perform a duty that he would not be willing to carry out himself. During the operation Column 7 was often split up into sub-units in order to perform various tasks required by Wingate as the operation unfolded. This often left senior officers, such as Leslie Cottrell and William Petersen in temporary charge of large groups of men and away from the comfort and security of the main column strength. Generally the column shadowed Wingate and his Brigade Head Quarters.

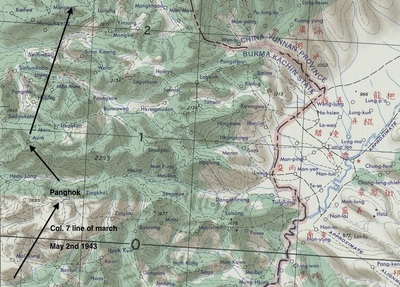

Once the order to disperse was called in late March, Gilkes decided to make for the Chinese borders and ultimately Fort Hertz, the most northerly town in Burma still in Allied hands. His column had been fully re-fitted with equipment in early April 1943 and had enjoyed a recent supply drop of food and ammunition shortly after crossing the Shweli River. He felt his men should have the means to make the longer, but hopefully safer journey out of Burma that year. The trip out into China and then hugging the borders until the grain of the country led them to Fort Hertz would take on average 4-6 weeks longer than marching out directly west toward India.

Gilkes had not reckoned on inheriting one hundred weary and exhausted men from Column 5, but this is exactly what happened when this group stumbled upon Column 7 as it prepared to cross the Shweli River on the 2nd April. Major Gilkes took in the lost souls from Column 5 and incorporated them into his pre-arranged dispersal parties. By the 15th April the long march through the Kachin Hills had begun.

Pte. Worthington had become ill around this time and was suffering from the effects of nearly ten weeks continuous marching through the tracks and jungles of Burma. Many men were beginning to drop out of the line of march, especially the already weakened soldiers from No. 5 Column. Tom Worthington and his comrade from Column 7, Arthur Clegg had managed to push their exhausted bodies onward for another few days, however, as the month of May arrived they were close to collapse.

Major Gilkes and his second in command, Leslie Cottrell decided that they must now leave some of the worst cases with the headmen of the local Kachin villages. This was a decision that all the commanders of Chindit Columns hoped they would never have to make. However, before the operation had even begun it had been accepted that any man who could no longer march with his unit would have to be left. Column 7 were within touching distance of the Chinese Yunnan Borders, this at least gave Gilkes the opportunity of leaving his ailing men with friendly and hopefully trustworthy tribesmen.

In a report written after the operation was over, Gilkes remembered:

Around early May, many of my men were worse for wear and had to be left in Kachin villages along the Sima-Sadon Road. We left them in the hands of Kachin Headmen, who promised to look after them. We paid the Kachins well from the remainder of our silver rupees.

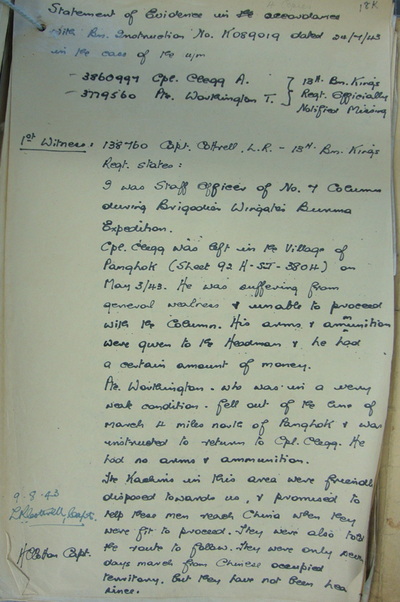

Another witness statement exists, which tells of the fate of Tom Worthington and Arthur Clegg. This was given by Captain Leslie Cottrell on the 24th July 1943:

138760 Captain Leslie R. Cottrell, 13th Battalion King's Regiment states:

I was Staff Officer of No. 7 Column during the Wingate Burma Expedition. Corporal Clegg was left in the village of Panghok on May 3rd 1943. He was suffering from general weakness and unable to proceed with the Column. His rifle and ammunition were given to the Headman, along with a certain amount of money.

Pte. Worthington, who was in a very weak condition, fell out of the line of march just four miles north of Panghok and was instructed to return to Corporal Clegg. He had no arms or ammunition. The Kachins in this area were friendly and disposed towards us and promised to help these men reach China when they were fit to proceed. They were also told the route to follow and were only seven days march from Chinese occupied territory. They have however, not been heard of since.

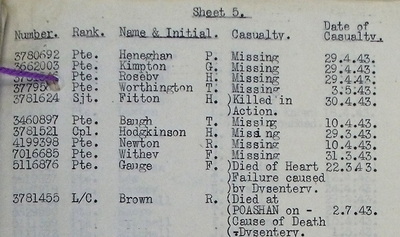

Worthington and Clegg were given the official missing in action date of the 3rd May 1943, this being the last time they had been seen by an officer from their unit, namely Captain Cottrell.

Seen below are some images in relation to the story of Tom Worthington and Arthur Clegg. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Thomas enlisted into the British Army and was posted to his home town Regiment, The King's Liverpool. He became part of the original 13th Battalion of the King's, taking up a place in C' Company at the Jordan Hill Barracks in Glasgow. In late December 1941 the battalion were selected for overseas duty and voyaged to India aboard the troopship 'Oronsay', leaving Liverpool Docks on the 8th of December.

In mid-June 1942 the battalion were given over to Brigadier Orde Wingate and began their Chindit training at the Saugor Camp in the Central Provinces of India. C' Company of the King's were re-designated as Chindit Column 7 under the overall command of Major Kenneth Daintry Gilkes. Kenneth Gilkes had joined the 13th King's in early 1941 from his original regiment, the North Staffordshire's.

Gilkes was a well liked and respected leader, who would never ask a man to perform a duty that he would not be willing to carry out himself. During the operation Column 7 was often split up into sub-units in order to perform various tasks required by Wingate as the operation unfolded. This often left senior officers, such as Leslie Cottrell and William Petersen in temporary charge of large groups of men and away from the comfort and security of the main column strength. Generally the column shadowed Wingate and his Brigade Head Quarters.

Once the order to disperse was called in late March, Gilkes decided to make for the Chinese borders and ultimately Fort Hertz, the most northerly town in Burma still in Allied hands. His column had been fully re-fitted with equipment in early April 1943 and had enjoyed a recent supply drop of food and ammunition shortly after crossing the Shweli River. He felt his men should have the means to make the longer, but hopefully safer journey out of Burma that year. The trip out into China and then hugging the borders until the grain of the country led them to Fort Hertz would take on average 4-6 weeks longer than marching out directly west toward India.

Gilkes had not reckoned on inheriting one hundred weary and exhausted men from Column 5, but this is exactly what happened when this group stumbled upon Column 7 as it prepared to cross the Shweli River on the 2nd April. Major Gilkes took in the lost souls from Column 5 and incorporated them into his pre-arranged dispersal parties. By the 15th April the long march through the Kachin Hills had begun.

Pte. Worthington had become ill around this time and was suffering from the effects of nearly ten weeks continuous marching through the tracks and jungles of Burma. Many men were beginning to drop out of the line of march, especially the already weakened soldiers from No. 5 Column. Tom Worthington and his comrade from Column 7, Arthur Clegg had managed to push their exhausted bodies onward for another few days, however, as the month of May arrived they were close to collapse.

Major Gilkes and his second in command, Leslie Cottrell decided that they must now leave some of the worst cases with the headmen of the local Kachin villages. This was a decision that all the commanders of Chindit Columns hoped they would never have to make. However, before the operation had even begun it had been accepted that any man who could no longer march with his unit would have to be left. Column 7 were within touching distance of the Chinese Yunnan Borders, this at least gave Gilkes the opportunity of leaving his ailing men with friendly and hopefully trustworthy tribesmen.

In a report written after the operation was over, Gilkes remembered:

Around early May, many of my men were worse for wear and had to be left in Kachin villages along the Sima-Sadon Road. We left them in the hands of Kachin Headmen, who promised to look after them. We paid the Kachins well from the remainder of our silver rupees.

Another witness statement exists, which tells of the fate of Tom Worthington and Arthur Clegg. This was given by Captain Leslie Cottrell on the 24th July 1943:

138760 Captain Leslie R. Cottrell, 13th Battalion King's Regiment states:

I was Staff Officer of No. 7 Column during the Wingate Burma Expedition. Corporal Clegg was left in the village of Panghok on May 3rd 1943. He was suffering from general weakness and unable to proceed with the Column. His rifle and ammunition were given to the Headman, along with a certain amount of money.

Pte. Worthington, who was in a very weak condition, fell out of the line of march just four miles north of Panghok and was instructed to return to Corporal Clegg. He had no arms or ammunition. The Kachins in this area were friendly and disposed towards us and promised to help these men reach China when they were fit to proceed. They were also told the route to follow and were only seven days march from Chinese occupied territory. They have however, not been heard of since.

Worthington and Clegg were given the official missing in action date of the 3rd May 1943, this being the last time they had been seen by an officer from their unit, namely Captain Cottrell.

Seen below are some images in relation to the story of Tom Worthington and Arthur Clegg. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

It is not known how long Tom and Arthur remained with the villagers of Panghok, but it is known that they became prisoners of war and were captured by the Japanese on the 28th June. One might imagine that they were in no fit state to move away from Panghok for several days, possibly even weeks. Many men were cared for by Kachin villages for short periods in 1943, some used these stopovers to rejuvenate their tired bodies before continuing the march out through Yunnan Province.

Two Chindits actually remained in a Kachin village for almost a year, living in a small shelter built for them by the Headman situated 800 yards from the village perimeter and well concealed in the jungle scrub. However, it must be remembered that harbouring these stricken men was an extremely dangerous and risky thing to do. If the Japanese were to discover that a village was helping and aiding the Chindit cause, the consequences would have been very grave indeed. In fact, there were cases of entire villages being burned to the ground and all the menfolk killed on discovery of continued loyalty towards the British.

Whether Pte. Worthington and Corporal Clegg were handed over to the Japanese by the village Headman, or they had recovered somewhat from their tribulations and had continued their march north, only then to be picked up by an enemy patrol, we will probably never know.

Around 240 Chindits were taken prisoner by the Japanese in 1943, many of these were taken to holding camps close to where they were first captured, before moving on to the larger concentration camp at Maymyo and then finally down to Rangoon Central Jail. Tom Worthington and Arthur Clegg were perhaps some of the last men to fall in to enemy hands that year. It is highly likely that they would have by-passed the experience of the Maymyo camp and been sent straight to Rangoon.

The Chindits from Operation Longcloth were held in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail and this is where Tom and Arthur would have been taken in the first instance. Conditions inside the jail were atrocious, with no proper sanitation or running water, many Chindits, totally exhausted and already suffering from tropical diseases such as dysentery and malaria, began to perish almost immediately. This is perhaps another pointer in relation to Pte. Worthington and Corporal Clegg's time before capture. Both men went on to survive their two years in Rangoon, suggesting that they had rebuilt their strength and vitality during their eight week stay in Kachin territory.

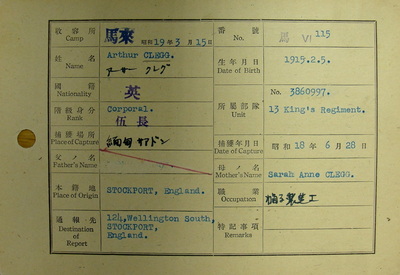

Tom Worthington's POW number inside Rangoon Jail was 386. Arthur Clegg was given the number, 115. This lower number is reference to his rank of Corporal, with him being the 115th such rank to be held at the jail since the Japanese occupation. As already mentioned, Worthington and Clegg were fortunate enough to survive their time as prisoners of the Japanese and were liberated in late April 1945, close to the Burmese town of Pegu. Most of the information about Tom and Arthur's time as prisoners of war comes from their POW index cards, which are shown in the gallery above.

For more information about Rangoon Jail and the liberation at Pegu, please read the information on the POW page linked here: Chindit POW's

After the POW's were recovered by Allied troops in early May 1945, they were all sent back to hospitals on the Indian mainland. Once they had been examined and treated for their ailments, most were sent on extended leave to rest and recuperate in the hill stations of Assam. It is unclear whether Tom Worthington or Arthur Clegg ever re-joined the 13th King's, who by this time were stationed at the Napier Barracks in Karachi. We know from documents held at the National Archives that Tom was back home in Liverpool by early November 1945, so it seems unlikely that he had returned to the battalion at any stage since being liberated from Rangoon.

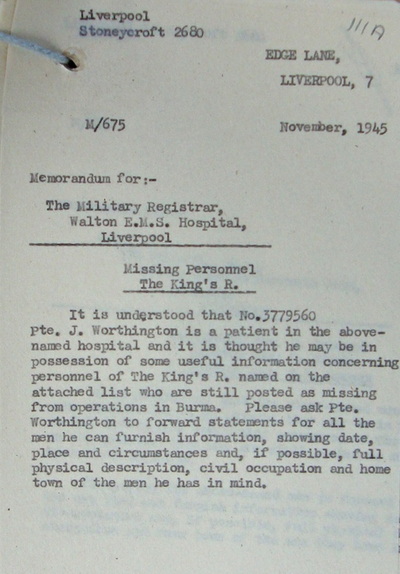

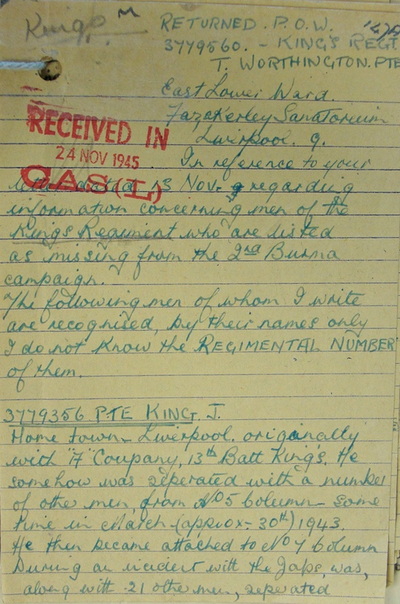

Tom's health was clearly still a concern even at this stage. In November 1945 he was a patient at the Fazakerley Sanatorium, close to his family home in Liverpool. It was from his bed in the Lower East Ward of the hospital, that he wrote a letter in response to a request from the Army Investigation Bureau. They were looking for information in relation to some of the other men from the 13th King's, that had either become prisoners of war in 1943, or had simply disappeared that year, never to be seen again.

Tom Worthington tried valiantly to remember the stories he had heard about his lost comrades and supply the Army Office with as much detail as he could. Here is a transcription of the letter he sent back. I have left the script almost entirely as it was written in 1945, only adding extra information where it seemed appropriate, or explaining some of the misspellings and so on.

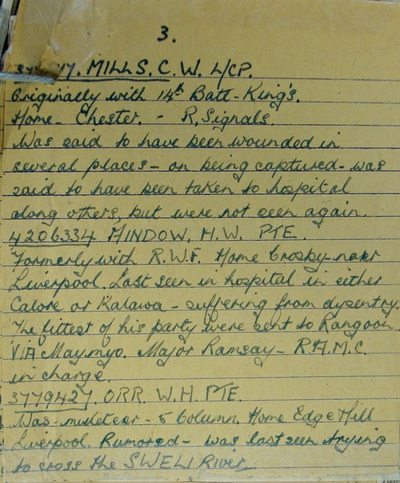

The six page letter of Pte. Thomas Worthington, written from his bed at the Fazakerley Sanatorium in November 1945.

In reference to your letter dated, 13th November, regarding information concerning men of the King’s Regiment who are listed as missing from the 2nd Burma Campaign.

The following men of whom I write are recognised by their names only, as I do not know the Regimental numbers.

NB. The service numbers are present in any case and seem to have been written by the same hand.

3779356-Pte. J. King

Hometown, Liverpool. Originally with A’ Company of the 13th Battalion, King’s Regiment. He was somehow separated with a number of other men from No. 5 Column, sometime in March (approx. 30th) 1943. He became attached to No. 7 Column. During an incident with the Japs, was, along with twenty-one other men, separated from the main body of No. 7 Column.

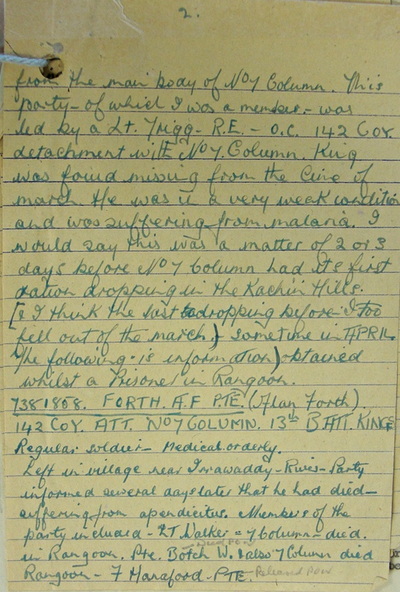

This party, of which I was a member, was led by Lieut. Trigg R.E. and officer commanding of 142 Commando detachment for No. 7 Column. King was found missing from the line of march. He was in a very weak condition and was suffering from malaria. I would say this was a matter of two or three days before No. 7 Column had its first ration dropping in the Kachin Hills. And I think, the last dropping before I too fell out from the line of march, sometime in April.

The following is information obtained whilst a prisoner in Rangoon:

7381858-Pte. A.F. Forth (Alan Forth).

142 Company, attached to No. 7 Column, 13th Battalion, King’s Regiment.

Regular soldier and medical orderly, was left in a village near the Irrawaddy River. His party were informed several days later that he had died, suffering from appendicitis. Members of the party included: Lt. Walker of No. 7 Column-died in Rangoon. Pte. W. Botch, also No. 7 Column and died Rangoon. Pte. F. Hanaford.

NB. For more information about this group of men, plus Pte. Aindow and Sgt. O' Gorman, please click on the following link:

Rex Walker and Dispersal Group 4

Lance Corporal C.W. Mills

Originally with the 14th Battalion, King’s Regiment. Attached Royal Signals.

Hometown was Chester. This man was said to have been wounded in several places on being captured. Was said to have been taken to hospital along with others, but was not seen again.

4206334-Pte. H.W. Aindow

Formerly with the Royal Welch Fusiliers. Hometown of Crosby, near Liverpool.

Last seen in hospital at either Calore or Kalawa, suffering from dysentery. The fittest of his party were sent to Rangoon via Maymyo. Major Ramsay R.A.M.C. in charge.

3779427-Pte. W.H. Orr

A muleteer with No. 5 Column. Hometown of Edge Hill, Liverpool.

Rumoured-last seen trying to cross the Shweli River to contact main party of No. 7 Column. He was complaining of a bad heart at the time.

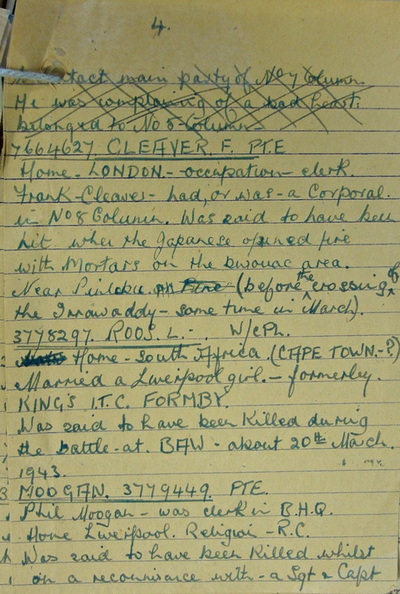

7664627-Pte. F. Cleaver

Hometown London. Occupation-clerk.

Frank Cleaver was a Corporal in No. 8 Column. Was said to have been hit when the Japanese opened up with mortars on the bivouac area. This was near Pinlebu, before the crossing of the Irrawaddy River, sometime in early March.

3778297-W/Corporal L. Roos

Home, South Africa (Cape Town?). Married a Liverpool girl. Formerly King’s I.T.C. at Formby.

Was said to have been killed at the battle of Baw, about the 20th March 1943.

3779449-Pte. P. Moogan

Phil Moogan was a clerk in B.H.Q. (Brigade Head Quarters). Hometown, Liverpool. Religion-Roman Catholic. Was said to have been killed whilst on a reconnaissance with a Sergeant and Captain Hastings, the Battalion Adjutant. This was a matter of two or three days before crossing the Irrawaddy going east.

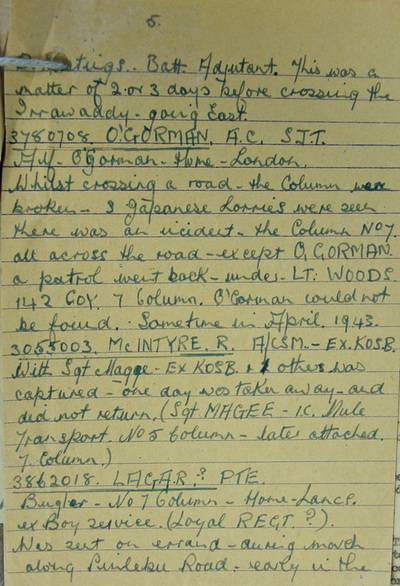

3780708-Sgt. A.C. O’Gorman

Alf Gorman. Home, London. Whilst crossing a road the Column was broken up by three Japanese Lorries and there was an incident. All of No. 7 Column were across, except O’Gorman. A patrol went back for him, led by Lt. Woods of 142 Company, No. 7 Column. O’Gorman could not be found. This was sometime in April 1943.

3055003-A/CSM Robert McIntyre

With Sgt. McGee (both ex-KOSB) and one other. Were captured, and then one day McIntyre was taken away and did not return. Sgt McGee was in charge of Mule Transport for No. 5 Column, later joined up with No. 7 Column.

3862018-Pte. H. Lagar

Bugler for No. 7 Column. Home, Lancashire, ex-Boy Service (Loyal Regiment).

Was sent on an errand during the march along the Pinlebu Road early in the campaign and did not return.

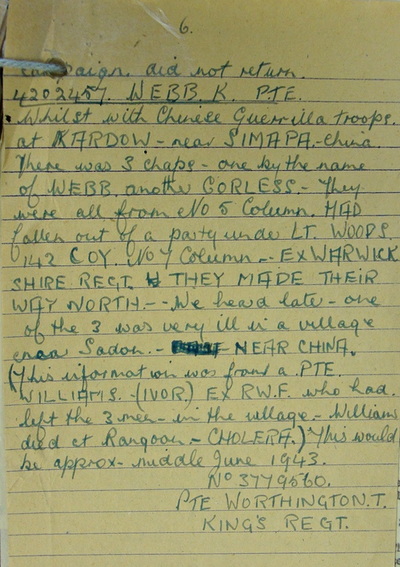

4202457-Pte. K. Webb

Whilst with the Chinese Guerrilla troops at Kardow near Sima-Pa in China. There were three chaps, one by the name of Webb, another called Corless (Carless) from No. 5 Column. They had fallen out of a party under Lt. Woods (Musgrave-Wood), of 142 Company, No. 7 Column. They made their way north. We heard later that one of the three was very ill in a village near Sadon.

This information was from Pte. Ivor Williams, ex-Royal Welch Fusiliers, who had been with the three men in the village. Williams died at Rangoon from Cholera. This would have been approximately the middle of June 1943.

NB. For more information about Pte. Webb, please click on the following link and scroll down to the story of Ernest Henderson:

Ernest Henderson

Letter signed. 3779560-Pte. T. Worthington, King’s Regiment.

Seen below is the actual letter, plus the original request for information sent by the Army Office. Coincidentally, the Army had set up an information centre in Liverpool which amongst other matters, dealt with investigations into men reported missing in action in Burma, this office was based at the Blue Coat School in Wavertree.

Two Chindits actually remained in a Kachin village for almost a year, living in a small shelter built for them by the Headman situated 800 yards from the village perimeter and well concealed in the jungle scrub. However, it must be remembered that harbouring these stricken men was an extremely dangerous and risky thing to do. If the Japanese were to discover that a village was helping and aiding the Chindit cause, the consequences would have been very grave indeed. In fact, there were cases of entire villages being burned to the ground and all the menfolk killed on discovery of continued loyalty towards the British.

Whether Pte. Worthington and Corporal Clegg were handed over to the Japanese by the village Headman, or they had recovered somewhat from their tribulations and had continued their march north, only then to be picked up by an enemy patrol, we will probably never know.

Around 240 Chindits were taken prisoner by the Japanese in 1943, many of these were taken to holding camps close to where they were first captured, before moving on to the larger concentration camp at Maymyo and then finally down to Rangoon Central Jail. Tom Worthington and Arthur Clegg were perhaps some of the last men to fall in to enemy hands that year. It is highly likely that they would have by-passed the experience of the Maymyo camp and been sent straight to Rangoon.

The Chindits from Operation Longcloth were held in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail and this is where Tom and Arthur would have been taken in the first instance. Conditions inside the jail were atrocious, with no proper sanitation or running water, many Chindits, totally exhausted and already suffering from tropical diseases such as dysentery and malaria, began to perish almost immediately. This is perhaps another pointer in relation to Pte. Worthington and Corporal Clegg's time before capture. Both men went on to survive their two years in Rangoon, suggesting that they had rebuilt their strength and vitality during their eight week stay in Kachin territory.

Tom Worthington's POW number inside Rangoon Jail was 386. Arthur Clegg was given the number, 115. This lower number is reference to his rank of Corporal, with him being the 115th such rank to be held at the jail since the Japanese occupation. As already mentioned, Worthington and Clegg were fortunate enough to survive their time as prisoners of the Japanese and were liberated in late April 1945, close to the Burmese town of Pegu. Most of the information about Tom and Arthur's time as prisoners of war comes from their POW index cards, which are shown in the gallery above.

For more information about Rangoon Jail and the liberation at Pegu, please read the information on the POW page linked here: Chindit POW's

After the POW's were recovered by Allied troops in early May 1945, they were all sent back to hospitals on the Indian mainland. Once they had been examined and treated for their ailments, most were sent on extended leave to rest and recuperate in the hill stations of Assam. It is unclear whether Tom Worthington or Arthur Clegg ever re-joined the 13th King's, who by this time were stationed at the Napier Barracks in Karachi. We know from documents held at the National Archives that Tom was back home in Liverpool by early November 1945, so it seems unlikely that he had returned to the battalion at any stage since being liberated from Rangoon.

Tom's health was clearly still a concern even at this stage. In November 1945 he was a patient at the Fazakerley Sanatorium, close to his family home in Liverpool. It was from his bed in the Lower East Ward of the hospital, that he wrote a letter in response to a request from the Army Investigation Bureau. They were looking for information in relation to some of the other men from the 13th King's, that had either become prisoners of war in 1943, or had simply disappeared that year, never to be seen again.

Tom Worthington tried valiantly to remember the stories he had heard about his lost comrades and supply the Army Office with as much detail as he could. Here is a transcription of the letter he sent back. I have left the script almost entirely as it was written in 1945, only adding extra information where it seemed appropriate, or explaining some of the misspellings and so on.

The six page letter of Pte. Thomas Worthington, written from his bed at the Fazakerley Sanatorium in November 1945.

In reference to your letter dated, 13th November, regarding information concerning men of the King’s Regiment who are listed as missing from the 2nd Burma Campaign.

The following men of whom I write are recognised by their names only, as I do not know the Regimental numbers.

NB. The service numbers are present in any case and seem to have been written by the same hand.

3779356-Pte. J. King

Hometown, Liverpool. Originally with A’ Company of the 13th Battalion, King’s Regiment. He was somehow separated with a number of other men from No. 5 Column, sometime in March (approx. 30th) 1943. He became attached to No. 7 Column. During an incident with the Japs, was, along with twenty-one other men, separated from the main body of No. 7 Column.

This party, of which I was a member, was led by Lieut. Trigg R.E. and officer commanding of 142 Commando detachment for No. 7 Column. King was found missing from the line of march. He was in a very weak condition and was suffering from malaria. I would say this was a matter of two or three days before No. 7 Column had its first ration dropping in the Kachin Hills. And I think, the last dropping before I too fell out from the line of march, sometime in April.

The following is information obtained whilst a prisoner in Rangoon:

7381858-Pte. A.F. Forth (Alan Forth).

142 Company, attached to No. 7 Column, 13th Battalion, King’s Regiment.

Regular soldier and medical orderly, was left in a village near the Irrawaddy River. His party were informed several days later that he had died, suffering from appendicitis. Members of the party included: Lt. Walker of No. 7 Column-died in Rangoon. Pte. W. Botch, also No. 7 Column and died Rangoon. Pte. F. Hanaford.

NB. For more information about this group of men, plus Pte. Aindow and Sgt. O' Gorman, please click on the following link:

Rex Walker and Dispersal Group 4

Lance Corporal C.W. Mills

Originally with the 14th Battalion, King’s Regiment. Attached Royal Signals.

Hometown was Chester. This man was said to have been wounded in several places on being captured. Was said to have been taken to hospital along with others, but was not seen again.

4206334-Pte. H.W. Aindow

Formerly with the Royal Welch Fusiliers. Hometown of Crosby, near Liverpool.

Last seen in hospital at either Calore or Kalawa, suffering from dysentery. The fittest of his party were sent to Rangoon via Maymyo. Major Ramsay R.A.M.C. in charge.

3779427-Pte. W.H. Orr

A muleteer with No. 5 Column. Hometown of Edge Hill, Liverpool.

Rumoured-last seen trying to cross the Shweli River to contact main party of No. 7 Column. He was complaining of a bad heart at the time.

7664627-Pte. F. Cleaver

Hometown London. Occupation-clerk.

Frank Cleaver was a Corporal in No. 8 Column. Was said to have been hit when the Japanese opened up with mortars on the bivouac area. This was near Pinlebu, before the crossing of the Irrawaddy River, sometime in early March.

3778297-W/Corporal L. Roos

Home, South Africa (Cape Town?). Married a Liverpool girl. Formerly King’s I.T.C. at Formby.

Was said to have been killed at the battle of Baw, about the 20th March 1943.

3779449-Pte. P. Moogan

Phil Moogan was a clerk in B.H.Q. (Brigade Head Quarters). Hometown, Liverpool. Religion-Roman Catholic. Was said to have been killed whilst on a reconnaissance with a Sergeant and Captain Hastings, the Battalion Adjutant. This was a matter of two or three days before crossing the Irrawaddy going east.

3780708-Sgt. A.C. O’Gorman

Alf Gorman. Home, London. Whilst crossing a road the Column was broken up by three Japanese Lorries and there was an incident. All of No. 7 Column were across, except O’Gorman. A patrol went back for him, led by Lt. Woods of 142 Company, No. 7 Column. O’Gorman could not be found. This was sometime in April 1943.

3055003-A/CSM Robert McIntyre

With Sgt. McGee (both ex-KOSB) and one other. Were captured, and then one day McIntyre was taken away and did not return. Sgt McGee was in charge of Mule Transport for No. 5 Column, later joined up with No. 7 Column.

3862018-Pte. H. Lagar

Bugler for No. 7 Column. Home, Lancashire, ex-Boy Service (Loyal Regiment).

Was sent on an errand during the march along the Pinlebu Road early in the campaign and did not return.

4202457-Pte. K. Webb

Whilst with the Chinese Guerrilla troops at Kardow near Sima-Pa in China. There were three chaps, one by the name of Webb, another called Corless (Carless) from No. 5 Column. They had fallen out of a party under Lt. Woods (Musgrave-Wood), of 142 Company, No. 7 Column. They made their way north. We heard later that one of the three was very ill in a village near Sadon.

This information was from Pte. Ivor Williams, ex-Royal Welch Fusiliers, who had been with the three men in the village. Williams died at Rangoon from Cholera. This would have been approximately the middle of June 1943.

NB. For more information about Pte. Webb, please click on the following link and scroll down to the story of Ernest Henderson:

Ernest Henderson

Letter signed. 3779560-Pte. T. Worthington, King’s Regiment.

Seen below is the actual letter, plus the original request for information sent by the Army Office. Coincidentally, the Army had set up an information centre in Liverpool which amongst other matters, dealt with investigations into men reported missing in action in Burma, this office was based at the Blue Coat School in Wavertree.

Update 21/05/2016.

Beginning on the 10th May 2016, I was delighted to receive a sequence of email contacts from Carol Worthington, who is Tom's niece.

Carol told me:

Thanks so much for this website. I have found out more about my Uncle "Tom" than ever before. We have some photographs of him from his time in India, if you would be interested I could send you these to upload on the website. I do not have very much information about his life, but I do know he worked for the Liverpool Corporation before the war.

My Grandmother was informed that he was missing - presumed dead in May 1943, only to receive a notification, two years later in 1945 that he had been found and liberated from Rangoon POW camp in Burma. One of the photos I can send, shows Tom with some other men, which we believe was taken during the liberation, and we have been told that a News of the World War Correspondent notified my Grandmother about the situation, his name was Arthur Halliwell. Although I cannot substantiate this last piece of information, the photograph is an official Army image and has Fleet Street addressed on the reverse.

Tom spoke very little of his experiences in Burma, like most of our heroes it seems. Sadly, he died in Fazakerley Hospital (Liverpool) from pneumonia on 6th March 1949. Unfortunately, I do not know the names of the men on the photo's with him, but maybe someone out there will know once you post some on-line. I hope this information helps and please let me know when you update your website. Thanks for your time and effort.

Best Wishes

Carol Worthington.

As you might imagine, it was wonderful to hear from Carol and learn that the information provided on this page about her Uncle Thomas was new and useful to the family. I have now sent Carol, all the papers and documents I posses about her uncle and she has sent over several photographs depicting his time in India and Burma. I was saddened to learn of Tom's death in 1949, barely three years after his return to the United Kingdom following repatriation. I wonder how much the effect of his two years imprisonment inside Rangoon Jail and the poor treatment handed out by the Japanese, contributed to his sorrowful demise in Fazakerley Hospitial.

Shown below is the image of the eight POW's which was taken shortly after their liberation at the village of Waw on the 29th April 1945. Tom Worthington is the tall man, seen third from the right as we look. In front of him (second right) is Tommy Byrne and I believe, although I cannot be 100% certain, that the man seen third from the left is Leon Frank. It would be fantastic if over the course of time, we could identify the rest of the group.

Beginning on the 10th May 2016, I was delighted to receive a sequence of email contacts from Carol Worthington, who is Tom's niece.

Carol told me:

Thanks so much for this website. I have found out more about my Uncle "Tom" than ever before. We have some photographs of him from his time in India, if you would be interested I could send you these to upload on the website. I do not have very much information about his life, but I do know he worked for the Liverpool Corporation before the war.

My Grandmother was informed that he was missing - presumed dead in May 1943, only to receive a notification, two years later in 1945 that he had been found and liberated from Rangoon POW camp in Burma. One of the photos I can send, shows Tom with some other men, which we believe was taken during the liberation, and we have been told that a News of the World War Correspondent notified my Grandmother about the situation, his name was Arthur Halliwell. Although I cannot substantiate this last piece of information, the photograph is an official Army image and has Fleet Street addressed on the reverse.

Tom spoke very little of his experiences in Burma, like most of our heroes it seems. Sadly, he died in Fazakerley Hospital (Liverpool) from pneumonia on 6th March 1949. Unfortunately, I do not know the names of the men on the photo's with him, but maybe someone out there will know once you post some on-line. I hope this information helps and please let me know when you update your website. Thanks for your time and effort.

Best Wishes

Carol Worthington.

As you might imagine, it was wonderful to hear from Carol and learn that the information provided on this page about her Uncle Thomas was new and useful to the family. I have now sent Carol, all the papers and documents I posses about her uncle and she has sent over several photographs depicting his time in India and Burma. I was saddened to learn of Tom's death in 1949, barely three years after his return to the United Kingdom following repatriation. I wonder how much the effect of his two years imprisonment inside Rangoon Jail and the poor treatment handed out by the Japanese, contributed to his sorrowful demise in Fazakerley Hospitial.

Shown below is the image of the eight POW's which was taken shortly after their liberation at the village of Waw on the 29th April 1945. Tom Worthington is the tall man, seen third from the right as we look. In front of him (second right) is Tommy Byrne and I believe, although I cannot be 100% certain, that the man seen third from the left is Leon Frank. It would be fantastic if over the course of time, we could identify the rest of the group.

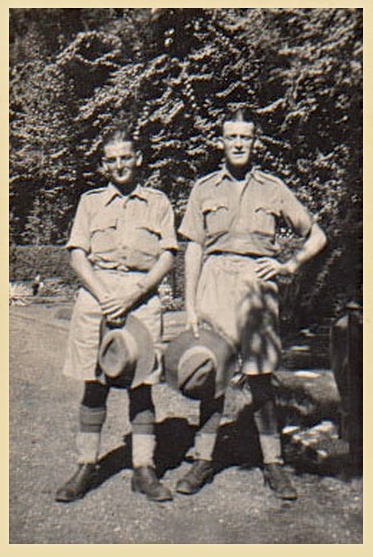

Seen below is a final gallery of photographs showing Tom Worthington; these are clearly from his time with the 13th King's in India during 1942 and possibly taken at the Secunderabad Cantonment and the Saugor Camp during Chindit training. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Carol for all her help and for allowing me to place these images on my website pages.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Carol for all her help and for allowing me to place these images on my website pages.

Update 16/04/2017.

From the pages of the Liverpool Evening Express dated Wednesday 18th April 1945 and under the headline, Birthday Greetings:

Tom Worthington. Greetings to my darling husband Tommy, on your 25th birthday and also our 4th wedding anniversary. Reported missing in May 1943 in Burma, probably a prisoner in Japanese hands. From his darling wife, Alice of 26 Portwood Street.

Night and day, you are the one.

Only you beneath the moon and tropical sun,

In the silence of my lonely little room I think of you,

Night and day, day and night.

Tom Worthington. Greetings for your 25th birthday and 4th anniversary Tommy darling. Missing in May 1943 with Wingate's Follies.

The roses weep, my tears keep falling, the gentle dove no longer coos.

Oh! can't you hear my sad heart calling, calling for you Tommy darling.

From your mother, Bert, Ronnie and all at 22 Dinorben Street.

Greetings Tommy on your 25th birthday and 4th anniversary. You are always in our hearts even though you are far away. From Nellie, Charlie and the children at 50 Harding Street.

From the pages of the Liverpool Evening Express dated Wednesday 18th April 1945 and under the headline, Birthday Greetings:

Tom Worthington. Greetings to my darling husband Tommy, on your 25th birthday and also our 4th wedding anniversary. Reported missing in May 1943 in Burma, probably a prisoner in Japanese hands. From his darling wife, Alice of 26 Portwood Street.

Night and day, you are the one.

Only you beneath the moon and tropical sun,

In the silence of my lonely little room I think of you,

Night and day, day and night.

Tom Worthington. Greetings for your 25th birthday and 4th anniversary Tommy darling. Missing in May 1943 with Wingate's Follies.

The roses weep, my tears keep falling, the gentle dove no longer coos.

Oh! can't you hear my sad heart calling, calling for you Tommy darling.

From your mother, Bert, Ronnie and all at 22 Dinorben Street.

Greetings Tommy on your 25th birthday and 4th anniversary. You are always in our hearts even though you are far away. From Nellie, Charlie and the children at 50 Harding Street.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, December 2014.