Pte. William Snape

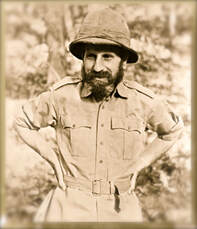

William Snape in India.

William Snape in India.

In May 2020, I was delighted to receive an email enquiry from Chris and Cecilia Lloyd in relation to Cecilia's father William Snape.

My father William Snape, Bill to his friends, didn't talk much about his war. On Sunday lunchtimes we would get little snippets about the jungle. He'd talk about columns of ants that would march right over your legs and Japanese soldiers who would call out 'Hey Jonny' in the hope of acquiring a target. Once my mother suggested he write down an account of what he'd been through and he got out a blank sheet of paper, but he then got upset and never tried again. I do remember he used to wear his bush hat when gardening and had a machete which he kept under the bed. Sadly, both of these have been lost now but I do have a small pen knife and his prayer book that were with him in the jungle. He once marked out his journey through India and Burma on my brother Paul's Philips Modern School Atlas and this was as much as we knew about where he travelled.

William Snape was born on the 22nd September 1912 in Liverpool. At the time of his enlistment into the British Army he was working as a manager at a grocer’s shop in the city. Bill was posted to the 13th King’s at the Jordan Hill barracks in Glasgow in July 1940 and was still with the battalion as they prepared for overseas service in India, leaving Liverpool Docks in early December 1941.

The King’s travelled aboard the troopship Oronsay which formed part of the convoy codenamed WS-14. The soldiers slept in hammocks in the lower decks and for the first few days the weather was rough with most men suffering from seasickness, with waves of 50-60 feet in height. One day a German plane was spotted and fired upon and later, on 17th December the Royal Navy destroyers dropped depth charges against a U-Boat in the area. The soldiers had little to do aboard the ship, but had a few diversions including PT exercises, swimming on some ships, tug of war competitions and even Monopoly. The convoy stopped at Freetown (Sierra Leone) on 21st December for fuel and supplies, but no shore leave was allowed although the locals came alongside to sell oranges and other fruit. On 8th January 1942 they docked at Durban where shore leave was granted and the soldiers visited cafes, bars and shops or went to see a film at the local cinemas.

On the 30th January 1942, the King’s disembarked at Bombay and travelled by train to Secunderabad where they took residence at the Gough Barracks in the city. At Secunderabad the 13th King’s were tasked with carrying out local policing and garrison duties. Whilst there Bill had a number of photographs taken, some of which he sent back to Muriel, his future wife, who he had met in Liverpool just before enlisting into the Army. During his time at Secunderabad, Bill sat down and wrote a poem about his time with the 13th King's up until their voyage to India:

My father William Snape, Bill to his friends, didn't talk much about his war. On Sunday lunchtimes we would get little snippets about the jungle. He'd talk about columns of ants that would march right over your legs and Japanese soldiers who would call out 'Hey Jonny' in the hope of acquiring a target. Once my mother suggested he write down an account of what he'd been through and he got out a blank sheet of paper, but he then got upset and never tried again. I do remember he used to wear his bush hat when gardening and had a machete which he kept under the bed. Sadly, both of these have been lost now but I do have a small pen knife and his prayer book that were with him in the jungle. He once marked out his journey through India and Burma on my brother Paul's Philips Modern School Atlas and this was as much as we knew about where he travelled.

William Snape was born on the 22nd September 1912 in Liverpool. At the time of his enlistment into the British Army he was working as a manager at a grocer’s shop in the city. Bill was posted to the 13th King’s at the Jordan Hill barracks in Glasgow in July 1940 and was still with the battalion as they prepared for overseas service in India, leaving Liverpool Docks in early December 1941.

The King’s travelled aboard the troopship Oronsay which formed part of the convoy codenamed WS-14. The soldiers slept in hammocks in the lower decks and for the first few days the weather was rough with most men suffering from seasickness, with waves of 50-60 feet in height. One day a German plane was spotted and fired upon and later, on 17th December the Royal Navy destroyers dropped depth charges against a U-Boat in the area. The soldiers had little to do aboard the ship, but had a few diversions including PT exercises, swimming on some ships, tug of war competitions and even Monopoly. The convoy stopped at Freetown (Sierra Leone) on 21st December for fuel and supplies, but no shore leave was allowed although the locals came alongside to sell oranges and other fruit. On 8th January 1942 they docked at Durban where shore leave was granted and the soldiers visited cafes, bars and shops or went to see a film at the local cinemas.

On the 30th January 1942, the King’s disembarked at Bombay and travelled by train to Secunderabad where they took residence at the Gough Barracks in the city. At Secunderabad the 13th King’s were tasked with carrying out local policing and garrison duties. Whilst there Bill had a number of photographs taken, some of which he sent back to Muriel, his future wife, who he had met in Liverpool just before enlisting into the Army. During his time at Secunderabad, Bill sat down and wrote a poem about his time with the 13th King's up until their voyage to India:

|

I was called up in the Army

In the month of warm July You see there was a war on Yes that's the reason why. They sent me up to Glasgow to a place called Jordon Hill Although the life was tough at first I wish I was up there still. From there I went to Felixstowe The East Coast was my home Just three months with the Sussex Folk and then we had to roam. So we took a trip to Clacton You know Clacton by the Sea Some folk said the place was dead but it was sticking out for me. The next call was to Colchester They still had us on the run when out we went on duty bent to a place called Abberton. To Mersea Isle for a little while then back to Abberton this village small no folk at all oh boy we had some fun. |

And then from there to Oxfordshire

I'll bet this place is good but lack a lass it came to pass we landed in Burford. This place was full of undergrads highbrow's and stiff wigs to Stow-in-the-Wold we went for gold in other words cigs. The rumour spread around one day we were for overseas K.D shirts and shorts we got and Topees if you please. Overseas someone remarked and with that he roared he shook his head wisely this mod won't go abroad. When embarkation leave began with everybody on it the lad looked bad he said that's bad I think we've gone and done it. In Burford, days just turned to weeks then more rumours came forth and whispers over plates of stew what's that we're moving North. |

At last there came that joyful day

and bundled in a truck we saw old Burford fade away I couldn't believe my luck. We arrived in Blackburn late that night we'd travelled miles & miles but even though the train was slow my face was wreathed in smiles. So here's a toast to Blackburn the Regent and the Plough to homeward trips and fish and chips I wish I was back there now. For when we take our minds back of all the good times we've had of Leicester Glasgow Blackburn and now Secunderabad. So just sit back and smile don't worry any more for a fortune teller told me we'll be home in '44. Bill Snape, Secunderabad, India 1942. |

By July 1942 the battalion was busy training for the first Wingate expedition at Saugor in the Central Provinces of India. Bill was allocated to No. 7 Column under the command of Major Kenneth Gilkes. Bill was a Vickers machine gunner and a member of the column’s Support Group Platoon. On the 13th February 1943, No. 7 Column crossed the Chindwin River and entered Japanese held territory in the company of No. 8 Column and Wingate’s Brigade Head Quarters. No. 7 Column remained with Wingate’s HQ for the vast majority of the expedition in Burma and experienced their first taste of action at the village of Kyunbin on the 13th March.

To read a more detailed account of No. 7 Column's journey on Operation Longcloth, please click on the following link: Leslie Randle Cottrell

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including several photographs of Bill and his comrades from the 13th King's in India. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

To read a more detailed account of No. 7 Column's journey on Operation Longcloth, please click on the following link: Leslie Randle Cottrell

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including several photographs of Bill and his comrades from the 13th King's in India. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

After several weeks marching in Burma, Bill’s Vickers gun came into serious action on the 29th March, covering the attempted crossing of he Irrawaddy as Wingate and the other Chindit columns looked to regain the river on their return journey to India. After deciding to break up the columns at the Irrawaddy, Wingate gave out orders to his commanders and Major Gilkes chose to take his men away to the east and exit Burma via the Chinese borders. After several days trying to find a suitable crossing point at the fast flowing Shweli River, Gilkes inherited around 100 men from No. 5 Column, who had become separated from their unit after an enemy ambush at a village called Hintha. Gilkes allocated these stragglers into his own pre-arranged dispersal groups and set off into the Kachin Hills. On his own map, drawn on the school Atlas, Bill suggests that he exited Burma via Fort Hertz. Two groups succeeded in making this trek from No. 7 Column’s dispersal parties, led by Lt. Astell and Lt. Musgrave-Wood respectively.

Whichever path Bill followed, at some point he lost contact with his comrades and found himself alone in the jungle. His service record shows him being posted as missing in Burma on 12th July 1943, but this was probably because Operation Longcloth was officially closed in July and a reconciliation of troops who had returned and those still missing was carried out. Bill eventually reported to British held territory on 23rd July 1943 some four months after the order to return to India was given and much later than Brigadier Wingate who reached Imphal on 3rd May.

After spending time in various hospitals in India, Bill re-joined the 13th King’s on the 14th August at the Napier Barracks in Karachi. He had suffered badly from recurring bouts of malaria which had kept him in hospital for a total of 83 days. Bill was presented with a certificate of participation for his service on Operation Longcloth, signed by Lt-Colonel S.A. Cooke the battalion commander during the first Wingate expedition.

The 13th King’s continued to perform garrison and internal security duties in Karachi for the rest of the war and until the men began to be sent for repatriation to the United Kingdom. Bill was processed at the Homeward Bound Troop Depot at Deolali on the 26th June 1945 and was back in the UK by the 24th July. Bill was released to the Royal Army Reserve Class Z (T) on 17th April 1946, discharged from the Territorial Army and allocated to the General Army Reserve on 11th February 1954, and on reaching the age 45 on 22nd September 1957 his liability for recall to the Army ceased.

Bill's conduct in the Army was recorded as: Exemplary. The officer present wrote the following short testimonial for Pte. W. Snape:

A smart and well spoken man who has been employed as a clerk and proved himself efficient and capable in his duties. He is clean and smart in appearance and respectful to those over him.

Seen below is a second gallery of images in relation to this narrative, including the school atlas map, Bill's Longcloth participation certificate and his Army Release Book. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Whichever path Bill followed, at some point he lost contact with his comrades and found himself alone in the jungle. His service record shows him being posted as missing in Burma on 12th July 1943, but this was probably because Operation Longcloth was officially closed in July and a reconciliation of troops who had returned and those still missing was carried out. Bill eventually reported to British held territory on 23rd July 1943 some four months after the order to return to India was given and much later than Brigadier Wingate who reached Imphal on 3rd May.

After spending time in various hospitals in India, Bill re-joined the 13th King’s on the 14th August at the Napier Barracks in Karachi. He had suffered badly from recurring bouts of malaria which had kept him in hospital for a total of 83 days. Bill was presented with a certificate of participation for his service on Operation Longcloth, signed by Lt-Colonel S.A. Cooke the battalion commander during the first Wingate expedition.

The 13th King’s continued to perform garrison and internal security duties in Karachi for the rest of the war and until the men began to be sent for repatriation to the United Kingdom. Bill was processed at the Homeward Bound Troop Depot at Deolali on the 26th June 1945 and was back in the UK by the 24th July. Bill was released to the Royal Army Reserve Class Z (T) on 17th April 1946, discharged from the Territorial Army and allocated to the General Army Reserve on 11th February 1954, and on reaching the age 45 on 22nd September 1957 his liability for recall to the Army ceased.

Bill's conduct in the Army was recorded as: Exemplary. The officer present wrote the following short testimonial for Pte. W. Snape:

A smart and well spoken man who has been employed as a clerk and proved himself efficient and capable in his duties. He is clean and smart in appearance and respectful to those over him.

Seen below is a second gallery of images in relation to this narrative, including the school atlas map, Bill's Longcloth participation certificate and his Army Release Book. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

When Bill returned home from India, Muriel was waiting for him and they married in 1946. Shortly after Bill's return his family received some more good news, as they heard that his sister Cecilia, who was a nun and had been taken into captivity by the Japanese in late 1941 when they invaded Borneo, had been liberated and would be journeying home to England soon.

In later life, Bill became a member of the Burma Star and Chindits Old Comrades Associations and in 1982, contributed to an appreciation of General Wingate, put together by the Chindits Old Comrades Association as a retort to criticism of their former leader in books and in the press around that time. Bill recounted:

In later life, Bill became a member of the Burma Star and Chindits Old Comrades Associations and in 1982, contributed to an appreciation of General Wingate, put together by the Chindits Old Comrades Association as a retort to criticism of their former leader in books and in the press around that time. Bill recounted:

Major-General Orde Wingate.

Major-General Orde Wingate.

I was a member of the 13th King's Regiment which took part in the first Wingate Campaign. We moved from Secunderabad, to the Central Provinces of India, to start our training which began in terrible monsoon weather. Here we came face to face with General Wingate who explained all details of the campaign to us. We had a good idea of the hazards ahead and knew that he would face them with us. He inspired us and all had great confidence in his ideas and ideals. In this first campaign, we were not meant to beat the Japanese and recapture Burma, but to harass their lines of communication. In spite of the monsoon rains, morale was always very high. All we wanted was to get into Burma and make a success of the campaign.

At the end of training, we faced a 200-mile exercise finishing at Jhansi, with day and night marching which would have broken many men's spirits under such conditions. But, as always, we had great faith in Orde Wingate's leadership. Here, we spent Christmas and had a short rest before leaving for Burma. At the end of his final speech, he gave every one the opportunity to withdraw from the campaign. Only one man took up the offer, which proves the outstanding confidence and trust we had in him. We knew that this was an adventure never attempted before, and we always were given to understand that the "hierarchy” did not approve of this venture. These things did not deter the men from following Orde Wingate. When halfway across Burma, the various columns met and Wingate spoke to us. The authorities, who said that half the men would be dead of disease, had already been proved wrong for we only had one man sick with dysentery out of the three columns.

There is no doubt that he was a fine leader and inspired his men with great confidence. My own view is that he was a man who suffered as much as his men did. He never gave up or wavered from his objective, and always the thought of his men was uppermost. If he had lived, what great heights would he have attained. It is a thousand pities this great man did not live to see victory. His sudden death was a terrible blow. It seems tragic that this brave warrior did not live to prove to the world what he was capable of.

Looking back, after all these years, to my wartime Burma experiences in the jungle, I feel most strongly that General Orde Wingate should be remembered as one of the great heroes of the war for his unflinching tenacity, for his bravery and for his tremendous driving force which won for us the war in Burma.

At the end of training, we faced a 200-mile exercise finishing at Jhansi, with day and night marching which would have broken many men's spirits under such conditions. But, as always, we had great faith in Orde Wingate's leadership. Here, we spent Christmas and had a short rest before leaving for Burma. At the end of his final speech, he gave every one the opportunity to withdraw from the campaign. Only one man took up the offer, which proves the outstanding confidence and trust we had in him. We knew that this was an adventure never attempted before, and we always were given to understand that the "hierarchy” did not approve of this venture. These things did not deter the men from following Orde Wingate. When halfway across Burma, the various columns met and Wingate spoke to us. The authorities, who said that half the men would be dead of disease, had already been proved wrong for we only had one man sick with dysentery out of the three columns.

There is no doubt that he was a fine leader and inspired his men with great confidence. My own view is that he was a man who suffered as much as his men did. He never gave up or wavered from his objective, and always the thought of his men was uppermost. If he had lived, what great heights would he have attained. It is a thousand pities this great man did not live to see victory. His sudden death was a terrible blow. It seems tragic that this brave warrior did not live to prove to the world what he was capable of.

Looking back, after all these years, to my wartime Burma experiences in the jungle, I feel most strongly that General Orde Wingate should be remembered as one of the great heroes of the war for his unflinching tenacity, for his bravery and for his tremendous driving force which won for us the war in Burma.

Sadly, Bill Snape passed away aged 87 on the 24th July 2000. I would like to take this opportunity to thank Chris and Cecilia Lloyd for allowing me to feature Bill's story on these website pages and for providing the wonderful photographs shown in the galleries above.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and the Lloyd/Snape family, January 2021.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and the Lloyd/Snape family, January 2021.