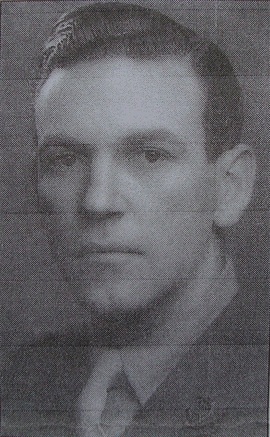

Raymond Ramsay MBE, FRCS.

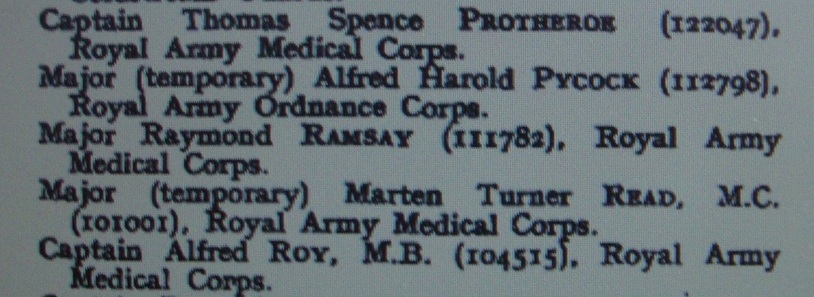

Major Raymond Ramsay, RAMC.

"If anyone had the means and knowledge to save your grandfather and the rest of those poor men, it would have been Raymond Ramsay."

The above is a quote from Dr. Bev Daily, and was taken from a telephone conversation I had with him in June this year (2012). It was during his early career as a GP that Bev first met and worked with Raymond. It is testimony to his clear and unwavering respect and confidence in Raymond Ramsay and his great skill as a doctor. Sadly, Major Ramsay did not have the opportunity of helping my grandfather in those crucial early weeks in Rangoon, as the Japanese Commandant of the jail had all officers and especially the medical officers kept in solitary confinement for up 6 weeks upon arrival at the prison. During this period many Chindits perished and many more became far too ill to ever have a chance of recovery from the trials of the exhausting campaign that year.

Major Raymond Ramsay was the senior medical officer in Wingate's Head Quarters Brigade. Admired and looked up to by many of the young officers in 1943, the Major, barely 30 years old himself, had clearly displayed his leadership qualities and after the expedition was deemed sufficiently to have proved Wingate's theories, he (Ramsay) was asked to lead one of the dispersal groups in an attempt to return to the safety of India.

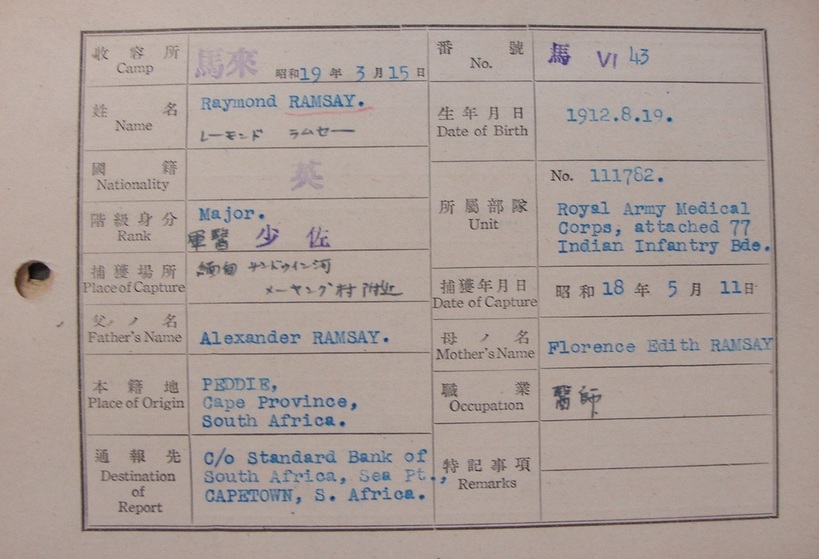

After several arduous days travelling west he and his companion Captain Arthur Moxham were taken prisoner by the Japanese on the 11th April and sent eventually to Rangoon Jail, where Major Ramsay became one of the senior medical officers and treated many of the sick and wounded POW's. He had been detained in the solitary confinement cells by the Japanese in Rangoon for several weeks, here is a quote from the memoirs of Lieutenant 'Willie' Wilding (also part of Wingate's HQ that year) on the subject:

"It was a disgrace that Major Ramsay was kept in solitary for so long, whilst our men were dying at a rate of at least one a day. Words cannot convey enough praise for his work, his devotion and his gentleness towards the men. Later they gave him an MBE just as if he had been a 'Beatle'. Never was a man's work so grossly undervalued by the top Brass, though he was never undervalued by us!"

The above is a quote from Dr. Bev Daily, and was taken from a telephone conversation I had with him in June this year (2012). It was during his early career as a GP that Bev first met and worked with Raymond. It is testimony to his clear and unwavering respect and confidence in Raymond Ramsay and his great skill as a doctor. Sadly, Major Ramsay did not have the opportunity of helping my grandfather in those crucial early weeks in Rangoon, as the Japanese Commandant of the jail had all officers and especially the medical officers kept in solitary confinement for up 6 weeks upon arrival at the prison. During this period many Chindits perished and many more became far too ill to ever have a chance of recovery from the trials of the exhausting campaign that year.

Major Raymond Ramsay was the senior medical officer in Wingate's Head Quarters Brigade. Admired and looked up to by many of the young officers in 1943, the Major, barely 30 years old himself, had clearly displayed his leadership qualities and after the expedition was deemed sufficiently to have proved Wingate's theories, he (Ramsay) was asked to lead one of the dispersal groups in an attempt to return to the safety of India.

After several arduous days travelling west he and his companion Captain Arthur Moxham were taken prisoner by the Japanese on the 11th April and sent eventually to Rangoon Jail, where Major Ramsay became one of the senior medical officers and treated many of the sick and wounded POW's. He had been detained in the solitary confinement cells by the Japanese in Rangoon for several weeks, here is a quote from the memoirs of Lieutenant 'Willie' Wilding (also part of Wingate's HQ that year) on the subject:

"It was a disgrace that Major Ramsay was kept in solitary for so long, whilst our men were dying at a rate of at least one a day. Words cannot convey enough praise for his work, his devotion and his gentleness towards the men. Later they gave him an MBE just as if he had been a 'Beatle'. Never was a man's work so grossly undervalued by the top Brass, though he was never undervalued by us!"

In late April 1945 the so called fit POW's from Rangoon were gathered together and marched out of the jail by their Japanese captors and headed north-east toward the road junction at Pegu. After several days hard marching the Japanese decided to leave the prisoners to their own devices and slipped quietly away in an attempt to reach the relative safety of the Siamese borders.

They had seemingly hoped to take the 400 or so Allied servicemen with them into Thailand, but the slow pace dictated by the long suffering POW's forced them to give up this plan and the two groups parted company on the outskirts of a small village called Waw. The Allied troops, including Raymond Ramsay were eventually liberated by a unit of the West Yorkshire Regiment two days later.

They had seemingly hoped to take the 400 or so Allied servicemen with them into Thailand, but the slow pace dictated by the long suffering POW's forced them to give up this plan and the two groups parted company on the outskirts of a small village called Waw. The Allied troops, including Raymond Ramsay were eventually liberated by a unit of the West Yorkshire Regiment two days later.

As I stated earlier, I am extremely fortunate to have spoken personally with Bev Daily, a retired GP and close family friend of Raymond Ramsay.

Bev lives in Burnham, Buckinghamshire and worked with Raymond for many years. He is the son of a South Wales coalminer and has written for well known medical journals here and in the USA. He is the author of several books and many articles including one about Raymond himself.

He told me how Raymond took him under his wing and helped him through his early years in the NHS and his general practice. Bev stated that Raymond had a fantastic bedside manner and was a wonderful surgeon. When Bev set up practice in Burnham he asked Raymond to help him with consultant domiciliary visits. These turned out to be a great help to Bev and of much advantage to his patients.

Early in the Spring of 2012 I had done a little detection work on the Internet and made contact with Dr. Tony Grewal and it was with his help that I eventually got to speak with Bev.

Firstly, here is what Tony had to say about Raymond Ramsay:

Dear Stephen,

Very glad your e-mail got to me, albeit by a rather circuitous route! I was Raymond Ramsay’s house surgeon in 1977, and hold him in great respect and some affection.

There is, I believe, a photograph of him on the Windsor Medical Society files, and I will forward this to you if I can find it.

In terms of his post war career, I know he ended up as a consultant general surgeon in East Berkshire, was President of the Windsor & District Medical Society and interviewed me for my first job after qualifying (even great men make mistakes). He has a son who is a surgeon, and another son in banking who lives abroad. I don’t have much more biographical detail, but will forward your e-mail to the retired senior partner at my wife’s practice, who had been a great friend of Raymond’s and will I am sure be able to help further.

In response to your question about him speaking about his time during the war-he never did! I only realised that his MBE was a military one, and heard about his time in the Far East, after his death. As you say, something that was common amongst his generation.

Regards Tony.

Bev lives in Burnham, Buckinghamshire and worked with Raymond for many years. He is the son of a South Wales coalminer and has written for well known medical journals here and in the USA. He is the author of several books and many articles including one about Raymond himself.

He told me how Raymond took him under his wing and helped him through his early years in the NHS and his general practice. Bev stated that Raymond had a fantastic bedside manner and was a wonderful surgeon. When Bev set up practice in Burnham he asked Raymond to help him with consultant domiciliary visits. These turned out to be a great help to Bev and of much advantage to his patients.

Early in the Spring of 2012 I had done a little detection work on the Internet and made contact with Dr. Tony Grewal and it was with his help that I eventually got to speak with Bev.

Firstly, here is what Tony had to say about Raymond Ramsay:

Dear Stephen,

Very glad your e-mail got to me, albeit by a rather circuitous route! I was Raymond Ramsay’s house surgeon in 1977, and hold him in great respect and some affection.

There is, I believe, a photograph of him on the Windsor Medical Society files, and I will forward this to you if I can find it.

In terms of his post war career, I know he ended up as a consultant general surgeon in East Berkshire, was President of the Windsor & District Medical Society and interviewed me for my first job after qualifying (even great men make mistakes). He has a son who is a surgeon, and another son in banking who lives abroad. I don’t have much more biographical detail, but will forward your e-mail to the retired senior partner at my wife’s practice, who had been a great friend of Raymond’s and will I am sure be able to help further.

In response to your question about him speaking about his time during the war-he never did! I only realised that his MBE was a military one, and heard about his time in the Far East, after his death. As you say, something that was common amongst his generation.

Regards Tony.

Raymond Ramsay, seen here in the 1960's.

Here are Bev Daily's memories of Raymond Ramsay:

I was privileged to be a personal friend of this wonderful, compassionate and delightful man. I was a GP in Burnham, Bucks where Raymond was our local consultant surgeon, and a great surgeon at that. I later became a medical journalist and wrote an article on Raymond for the, then, very popular magazine "World Medicine". I still have that article along with a copy of Raymond's obituary. Raymond used to come back to our pretty humble home after seeing a domiciliary patient and regail us with his stories about his time in Burma.

"An ambush Bev! Machine guns on every side .They hardly hit any of us. Very poor eyesight, of course. The Japanese all seem to wear glasses. I can't understand how they make such wonderful cameras! Mind you, the Japanese medical orderly who looked after my bullet wound was great. Dressed it beautifully. Then got me a ride on the back of an elephant. Sitting on the chains, bloody uncomfortable but better than walking."

It turned out that we were very privileged indeed, as he told these stories to virtually nobody else.

At Raymond's funeral I met some of his old soldier patients. They all said much the same things about him:

"Wonderful man, and didn't he give the old Japs the run around, and got away with it. They didn't seem to know how to cope with him. Put him in a cage, hit him, nothing much seemed to work, he did more to keep up our spirits than anything else."

Major Ramsay had often stood up to the cruel minded Japanese guards in Rangoon Jail, insisting on better treatment for the sick men he attempted to help in the ramshackle prison hospital block. He took several severe beatings from these guards, but this did not prevent him from continually asking for more drugs, or for his sick men to be excused tenko (the Japanese word for parade). In Rangoon, as elsewhere, if you were sick and could not work, then you were not entitled to be fed. Ramsay worked tirelessly to make sure that some food was smuggled into the hospital block for these unfortunate men.

Bev continued:

I remember that Raymond had no anti-Japanese feelings whatsoever, even though he had been badly treated at times in Rangoon Jail. He had been well treated initially on capture near the Chindwin River, although later on he would suffer a mock execution by a group of Japanese NCO's, who used the flat side of their swords to strike Raymond on the back of the neck. He was also made to stand out in the afternoon sun holding a brick in each of his outstretched hands, similar to a crucifixion stance.

Both Bev and Tony recounted the story of how Major Ramsay had unexpectedly received a bottle of sake (or whiskey) from a Japanese guard in Rangoon, a gift to the Doctor on the Emperor's birthday. Shocked at this kindly gesture, Ramsay went off to discuss with some senior officers in the jail what the bottle could be best used for. They pondered long and hard, should they use it to sterilise the hospital instruments, or as a comforting drink for the dying perhaps? In the end they decided to drink away their good fortune there and then. I doubt any of the sick men would have begrudged the Doctor his one night of alcoholic pleasure.

Bev's final thoughts about Raymond were:

Before Raymond offered up an opinion or announced a diagnosis he would take in a large and audible breath. It became his trademark address and we all seemed to wait for it.

He had the air of a British gentleman, which he was, and he was very compassionate towards his patients. All the horrors and atrocities he had seen in Burma, did not stop him treating the smallest complaint in civilian life with kindness and care.

I met some of the Chindit POW's held in Rangoon at Raymond's funeral, where as part of the service Tennyson's poem 'Crossing the Bar' was read. A poem with a sea faring and sailing metaphor for the passing from life over to death. Raymond was extremely passionate about sailing.

I was privileged to be a personal friend of this wonderful, compassionate and delightful man. I was a GP in Burnham, Bucks where Raymond was our local consultant surgeon, and a great surgeon at that. I later became a medical journalist and wrote an article on Raymond for the, then, very popular magazine "World Medicine". I still have that article along with a copy of Raymond's obituary. Raymond used to come back to our pretty humble home after seeing a domiciliary patient and regail us with his stories about his time in Burma.

"An ambush Bev! Machine guns on every side .They hardly hit any of us. Very poor eyesight, of course. The Japanese all seem to wear glasses. I can't understand how they make such wonderful cameras! Mind you, the Japanese medical orderly who looked after my bullet wound was great. Dressed it beautifully. Then got me a ride on the back of an elephant. Sitting on the chains, bloody uncomfortable but better than walking."

It turned out that we were very privileged indeed, as he told these stories to virtually nobody else.

At Raymond's funeral I met some of his old soldier patients. They all said much the same things about him:

"Wonderful man, and didn't he give the old Japs the run around, and got away with it. They didn't seem to know how to cope with him. Put him in a cage, hit him, nothing much seemed to work, he did more to keep up our spirits than anything else."

Major Ramsay had often stood up to the cruel minded Japanese guards in Rangoon Jail, insisting on better treatment for the sick men he attempted to help in the ramshackle prison hospital block. He took several severe beatings from these guards, but this did not prevent him from continually asking for more drugs, or for his sick men to be excused tenko (the Japanese word for parade). In Rangoon, as elsewhere, if you were sick and could not work, then you were not entitled to be fed. Ramsay worked tirelessly to make sure that some food was smuggled into the hospital block for these unfortunate men.

Bev continued:

I remember that Raymond had no anti-Japanese feelings whatsoever, even though he had been badly treated at times in Rangoon Jail. He had been well treated initially on capture near the Chindwin River, although later on he would suffer a mock execution by a group of Japanese NCO's, who used the flat side of their swords to strike Raymond on the back of the neck. He was also made to stand out in the afternoon sun holding a brick in each of his outstretched hands, similar to a crucifixion stance.

Both Bev and Tony recounted the story of how Major Ramsay had unexpectedly received a bottle of sake (or whiskey) from a Japanese guard in Rangoon, a gift to the Doctor on the Emperor's birthday. Shocked at this kindly gesture, Ramsay went off to discuss with some senior officers in the jail what the bottle could be best used for. They pondered long and hard, should they use it to sterilise the hospital instruments, or as a comforting drink for the dying perhaps? In the end they decided to drink away their good fortune there and then. I doubt any of the sick men would have begrudged the Doctor his one night of alcoholic pleasure.

Bev's final thoughts about Raymond were:

Before Raymond offered up an opinion or announced a diagnosis he would take in a large and audible breath. It became his trademark address and we all seemed to wait for it.

He had the air of a British gentleman, which he was, and he was very compassionate towards his patients. All the horrors and atrocities he had seen in Burma, did not stop him treating the smallest complaint in civilian life with kindness and care.

I met some of the Chindit POW's held in Rangoon at Raymond's funeral, where as part of the service Tennyson's poem 'Crossing the Bar' was read. A poem with a sea faring and sailing metaphor for the passing from life over to death. Raymond was extremely passionate about sailing.

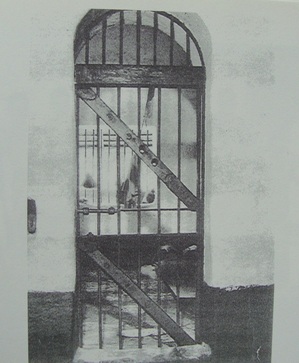

The ominous and foreboding Rangoon Central Jail, seen here well before WW2.

First seen in the medical periodical 'World Medicine' in October 1982, here is Bev Daily's account of his colleague and great friend, Raymond Ramsay.

'Not only a Surgeon, but a Gent'.

I couldn't quite see how she could get peritonitis from a carcinoma of the rectum. But there it was .........and she wasn't my patient either.

"It can't be," said the grey, shocked lady with the board-like abdomen, "I only saw the surgeon this morning and there was nothing wrong then."

A ruined evening.

What a way to start! I'd never done a proper surgical job, nor a medical one if it came to that. ENT (ear, nose and throat) and obstetrics. I'd had two junior house jobs and was now looking after 3,000 patients by myself. I'd joined as a junior partner only four weeks before, and my boss, the only other doctor in the practice, was off on a cruise to South Africa for six weeks. Definitely a situation to which the RCGP (Royal College of General Practitioners) had they existed then, would have reacted with screams of horror.

I phoned the surgeon whom this lady had privately consulted. It was Saturday evening. His wife answered: they were having a dinner party she told me. He came to the telephone. "It can't be," he said. "I only saw her this morning and she was perfectly all right then. You know the diagnosis?"

"Yes sir," I stammered. "Ca. rectum. You're operating on her next week, I believe....sir." My God! He did sound like a 'sir' too.

"This is very inconvenient," he said. I note this, because that was the first and only time in our 20 or more years of happy association that he ever suggested any reluctance to leap to my aid. "But I suppose I should come and have a look at her if that's what you think is wrong." I remained silent at this implied let-out. "From where are you speaking?"

I could see, rather than hear him suck his teeth, as I gave him an address some ten miles from where he was just about to pour the Nuit St. Georges. A ruined evening. I sat down beside the lady's bed and waited for this man whom I had never met.

When he arrived my worst fears were realised. Not only did he sound like a sir, he looked like one. The Bristol motor car, the beautifully cut suit, the silver hair, the walk-more on oiled rollers than feet, and the air of total mastery of the situation. He swept into the bedroom where he and the patient vigorously apologised to each other for the inconvenience caused.

As a gesture, the sheet was pulled down and an elegant hand placed on the abdomen. "By George", he said, "she has got peritonitis!"

The letter addressed to my surgery the next day began "Dear Beverly", (a name I had abandoned after a vigorous punch-up at my primary school) and ended "With kind regards, Yours sincerely, Raymond."

'Not only a Surgeon, but a Gent'.

I couldn't quite see how she could get peritonitis from a carcinoma of the rectum. But there it was .........and she wasn't my patient either.

"It can't be," said the grey, shocked lady with the board-like abdomen, "I only saw the surgeon this morning and there was nothing wrong then."

A ruined evening.

What a way to start! I'd never done a proper surgical job, nor a medical one if it came to that. ENT (ear, nose and throat) and obstetrics. I'd had two junior house jobs and was now looking after 3,000 patients by myself. I'd joined as a junior partner only four weeks before, and my boss, the only other doctor in the practice, was off on a cruise to South Africa for six weeks. Definitely a situation to which the RCGP (Royal College of General Practitioners) had they existed then, would have reacted with screams of horror.

I phoned the surgeon whom this lady had privately consulted. It was Saturday evening. His wife answered: they were having a dinner party she told me. He came to the telephone. "It can't be," he said. "I only saw her this morning and she was perfectly all right then. You know the diagnosis?"

"Yes sir," I stammered. "Ca. rectum. You're operating on her next week, I believe....sir." My God! He did sound like a 'sir' too.

"This is very inconvenient," he said. I note this, because that was the first and only time in our 20 or more years of happy association that he ever suggested any reluctance to leap to my aid. "But I suppose I should come and have a look at her if that's what you think is wrong." I remained silent at this implied let-out. "From where are you speaking?"

I could see, rather than hear him suck his teeth, as I gave him an address some ten miles from where he was just about to pour the Nuit St. Georges. A ruined evening. I sat down beside the lady's bed and waited for this man whom I had never met.

When he arrived my worst fears were realised. Not only did he sound like a sir, he looked like one. The Bristol motor car, the beautifully cut suit, the silver hair, the walk-more on oiled rollers than feet, and the air of total mastery of the situation. He swept into the bedroom where he and the patient vigorously apologised to each other for the inconvenience caused.

As a gesture, the sheet was pulled down and an elegant hand placed on the abdomen. "By George", he said, "she has got peritonitis!"

The letter addressed to my surgery the next day began "Dear Beverly", (a name I had abandoned after a vigorous punch-up at my primary school) and ended "With kind regards, Yours sincerely, Raymond."

A solitary confinement cell in Rangoon Jail.

Throughout my apprentice years of general practice, for in less than 12 months of this first meeting I was to be singlehanded, Raymond was always at my elbow whenever I ran into any trouble of a surgical nature. Always ready to do a domiciliary (home visit), always happy to give advice on the telephone or sort out a bed when none seemed available.

Often after a domiciliary he came to our modest home, stepping over the children, the playpen, the rack of drying nappies and the toys, to install himself in front of the fire, drink in hand and pontificate in the most reactionary fashion on every subject from Harold Wilson to the Beatles.

My wife and I would rock with laughter as he would solemnly dissect the trendy, each point emphasised with a raised eyebrow, a rhetorical question and a sniff. I bought a relatively humble stereo when, I admit, we were still almost sitting on orange boxes. He declared that, for himself, a small record player was more than sufficient. "What about that enormous car you drive about in? I asked, pointing to the Bristol's successor, an Alvis, parked in front of our living room window.

"Ah, well..........you see.......when I turn up in that, outside someone's house, they're halfway cured. They think, he must be a damned fine surgeon to afford a car like that."

I saw him lose his monumental calm only once. Many years back. An acute appendicitis, there was little doubt. I phoned the hospital on surgical take. The locum house surgeon told me that there were only two beds left and they were being kept for cases of real urgency. "But this is a case of acute appendicitis". The reply "I suggest you call the bed bureau". The phone went down.

Raymond came out. There was no doubt, of course. He rang the hospital and explained to the same houseman, in the most silky of tones, that he was consultant surgeon to the hospital and was sending in a case of acute appendicitis.

"No beds!" boomed the reply. "You'd better phone the bed bureau." The line went silent. At that moment Raymond was near to apoplexy.

Adapting to circumstance.

A patient of mine with a lifelong fear of carcinoma of the breast, from which her mother and sister had died at an early age, developed the disease herself. I made an urgent appointment for her to see Raymond at his clinic. She did not turn up, too afraid to face the awful truth. She went into acute depression.

I told Raymond about this situation and he suggested that he might drop in and see her. He spent an hour talking to her and the next week he did the mastectomy that has given her 15 years of perfect health thus far.

On another occasion, I remember he did two home visits on one day for me. One private, one NHS. The private lady was very arrogant and dismissive of the considerable medical care she had received. Raymond treated her with scathing politeness and left her in no doubt that the ailment from which she suffered most severely was self-centredness. "I hope you didn't mind", he said to me afterwards. I was delighted.

We then went round the corner to one of my most disreputable families, living in considerable squalor. The pleasant, somewhat battered, multi-parous lady of the house, with a non-resolving cholecystitis, he treated like a duchess.

I have continually referred to Raymond as was. He is still, of course very much is. Having now retired from the NHS, with more time to sail the Main (Raymond was an avid sailing enthusiast), he is still an active surgeon.

Often after a domiciliary he came to our modest home, stepping over the children, the playpen, the rack of drying nappies and the toys, to install himself in front of the fire, drink in hand and pontificate in the most reactionary fashion on every subject from Harold Wilson to the Beatles.

My wife and I would rock with laughter as he would solemnly dissect the trendy, each point emphasised with a raised eyebrow, a rhetorical question and a sniff. I bought a relatively humble stereo when, I admit, we were still almost sitting on orange boxes. He declared that, for himself, a small record player was more than sufficient. "What about that enormous car you drive about in? I asked, pointing to the Bristol's successor, an Alvis, parked in front of our living room window.

"Ah, well..........you see.......when I turn up in that, outside someone's house, they're halfway cured. They think, he must be a damned fine surgeon to afford a car like that."

I saw him lose his monumental calm only once. Many years back. An acute appendicitis, there was little doubt. I phoned the hospital on surgical take. The locum house surgeon told me that there were only two beds left and they were being kept for cases of real urgency. "But this is a case of acute appendicitis". The reply "I suggest you call the bed bureau". The phone went down.

Raymond came out. There was no doubt, of course. He rang the hospital and explained to the same houseman, in the most silky of tones, that he was consultant surgeon to the hospital and was sending in a case of acute appendicitis.

"No beds!" boomed the reply. "You'd better phone the bed bureau." The line went silent. At that moment Raymond was near to apoplexy.

Adapting to circumstance.

A patient of mine with a lifelong fear of carcinoma of the breast, from which her mother and sister had died at an early age, developed the disease herself. I made an urgent appointment for her to see Raymond at his clinic. She did not turn up, too afraid to face the awful truth. She went into acute depression.

I told Raymond about this situation and he suggested that he might drop in and see her. He spent an hour talking to her and the next week he did the mastectomy that has given her 15 years of perfect health thus far.

On another occasion, I remember he did two home visits on one day for me. One private, one NHS. The private lady was very arrogant and dismissive of the considerable medical care she had received. Raymond treated her with scathing politeness and left her in no doubt that the ailment from which she suffered most severely was self-centredness. "I hope you didn't mind", he said to me afterwards. I was delighted.

We then went round the corner to one of my most disreputable families, living in considerable squalor. The pleasant, somewhat battered, multi-parous lady of the house, with a non-resolving cholecystitis, he treated like a duchess.

I have continually referred to Raymond as was. He is still, of course very much is. Having now retired from the NHS, with more time to sail the Main (Raymond was an avid sailing enthusiast), he is still an active surgeon.

Bev Daily's article concludes:

Sense of humour.

The best of men are often seen only in the guise they present to the world. Beneath Raymond's urbane exterior lies the common touch; under the reactionary words, compassion; and under the veneer of solemnity a sense of humour and appreciation of the absurd.

My wife and I had the privilege of hearing about his experiences as a Japanese POW, when he was a medical officer at Rangoon Central Jail for two years, something of which at least 90% of those that work for him are unaware. There was one story that sticks in my mind more than any other......

"I had never been so surprised in my life, Bev......... this Japanese medical orderly, a sergeant , came in to see me. I suppose I'd been at Rangoon for 18 months then. He stood in front of me, in this shed, there were only the two of us, and threw me a huge salute. Amazing! Well...(breath sucked in)....he could have been shot just for that. Then, even more extraordinary, from behind his back he produced a bottle of Sake, handed it to me, saluted again and walked out."

Raymond spread his arms and shook his head in wonderment. "I was flabbergasted. I went straight to the senior British officer and his Adjutant to try and decide what should be done. Well, I mean...Sake! Just about the first thing you could broadly call medicine we had ever had." He paused.

"We discussed the matter far into the night. Should we give it in small sips to comfort the dying? Should we use it in a few large amounts to ease the pain of our crude attempts at surgery? Perhaps we should use it to sterilise the few rudimentary instruments we had managed to obtain?"

He hunched his shoulders and turned his palms towards me in the universal display of indecision. "What on earth did you do?" I asked with due solemnity.

"Drank the whole bottle between the three of us. We got absolutely plastered!"

Gentleman Surgeon. Honest, as always.

As a footnote to the above story, Bev did receive a letter from Raymond congratulating him on the article and admiring his gift for writing, something Raymond did not feel he possessed himself. What a great shame this would prove to be for those of us wishing to learn more about the man and his lifetimes experiences.

Sense of humour.

The best of men are often seen only in the guise they present to the world. Beneath Raymond's urbane exterior lies the common touch; under the reactionary words, compassion; and under the veneer of solemnity a sense of humour and appreciation of the absurd.

My wife and I had the privilege of hearing about his experiences as a Japanese POW, when he was a medical officer at Rangoon Central Jail for two years, something of which at least 90% of those that work for him are unaware. There was one story that sticks in my mind more than any other......

"I had never been so surprised in my life, Bev......... this Japanese medical orderly, a sergeant , came in to see me. I suppose I'd been at Rangoon for 18 months then. He stood in front of me, in this shed, there were only the two of us, and threw me a huge salute. Amazing! Well...(breath sucked in)....he could have been shot just for that. Then, even more extraordinary, from behind his back he produced a bottle of Sake, handed it to me, saluted again and walked out."

Raymond spread his arms and shook his head in wonderment. "I was flabbergasted. I went straight to the senior British officer and his Adjutant to try and decide what should be done. Well, I mean...Sake! Just about the first thing you could broadly call medicine we had ever had." He paused.

"We discussed the matter far into the night. Should we give it in small sips to comfort the dying? Should we use it in a few large amounts to ease the pain of our crude attempts at surgery? Perhaps we should use it to sterilise the few rudimentary instruments we had managed to obtain?"

He hunched his shoulders and turned his palms towards me in the universal display of indecision. "What on earth did you do?" I asked with due solemnity.

"Drank the whole bottle between the three of us. We got absolutely plastered!"

Gentleman Surgeon. Honest, as always.

As a footnote to the above story, Bev did receive a letter from Raymond congratulating him on the article and admiring his gift for writing, something Raymond did not feel he possessed himself. What a great shame this would prove to be for those of us wishing to learn more about the man and his lifetimes experiences.

Bev mentioned meeting officers and men from Rangoon Jail at Major Ramsay's funeral, written below is what some of them had to say about the much respected medical officer:

From Lieutenant 'Willie' Wilding's memoirs:

The "Hospital" was a bug-ridden building with a sort of greenhouse type staging on which the sick lay and, all too often, died. No beds or sick room equipment of any kind.

The drugs, etc, available to the M.O. were:

• For dysentery...creosote pills - which were mostly useless;

• For jungle sores...copper sulphate (bluestone) - which when applied was very painful;

• For malaria...a little (a very little) quinine and almost all of that pinched from the Japs;

• A few aspirin;

• A pair of dental forceps and an artery clamp (both stolen property).

With these our excellent M.O. Major Ramsay coped with dysentery, beri-beri, malaria, gunshot wounds, jungle sores, the aftermath of amputations, cholera, smallpox, pellagra, broken bones, toothache, two cases of leprosy, and probably a lot more I never knew about. If you required an "operation" you were expected to provide a razor blade - there was, of course, no sort of anaesthetic of any kind. If you had to have a tooth out, you bit with the sore tooth on a knife handle until the tooth felt numb, then the Major whipped it out as fast as he could.

Also from Wilding's memoir a mention of two men who helped run the hospital before and after Major Ramsay was released from solitary confinement:

Lieutenant Brian Horncastle of the Kings Regiment. A man who was always kind and helpful and always quiet about it. He was troubled about the danger of jungle sores (this before we had our doctor available) and experimented on his own with carbolic. His sores became gangrenous and he died in February 1944.

Sergeant Stanley Scruton also of the Kings Regiment. A bricklayer's labourer by trade. Before (and a little time after) Major Ramsay was let out of solitary, he ran the "Hospital" with much compassion and very little knowledge. He died early in 1944. He was a splendid chap. I am sure that his death was, at least in part, due to frustration, because he could do so little for the charges in his care.

From Charles Coubrough's book, 'Memories of a Perpetual Second Lieutenant':

"In early 1944 I found myself in the prison hospital being treated for suppurating sores on my backside. I had to lie on my front the whole time. Colonel MacKenzie diagnosed my condition as scabies. He sent me to see Raymond Ramsay who treated me with his now famous 'bluestones'. It was extremely painful, but I didn't mind one bit, as it it was so much better than the dreadful itching I was experiencing before. Major Ramsay was a real hero in Rangoon Jail."

From Kenneth MacKenzie's book 'Operation Rangoon Jail':

"There were several Indian doctors in Rangoon who helped me considerably in the early months of incarceration. Major Kilgour had died and this had left me alone as the sole British medic. Later we were joined by Major Raymond Ramsay, who did really splendid work, coming as he did, at a time when the rest of us were ill and exhausted."

Ramsay also helped MacKenzie in clearing an outbreak of cholera from the jail, treating the sick men himself and taking responsibility for the burning of the dead in order to eliminate the disease completely from the prison. He also treated some badly burnt American airmen who had been shot down over Rangoon towards the end of 1944 and ably assisted MacKenzie in an operation to save the life of the senior Chinese POW, General H. C. Chi. The General had been attacked by one of his own men in the jail and the resulting stab wound had punctured his bowel, after an operation lasting about an hour and using only rudimentary instruments and medicines, the British doctors had done all they could.

From Lieutenant 'Willie' Wilding's memoirs:

The "Hospital" was a bug-ridden building with a sort of greenhouse type staging on which the sick lay and, all too often, died. No beds or sick room equipment of any kind.

The drugs, etc, available to the M.O. were:

• For dysentery...creosote pills - which were mostly useless;

• For jungle sores...copper sulphate (bluestone) - which when applied was very painful;

• For malaria...a little (a very little) quinine and almost all of that pinched from the Japs;

• A few aspirin;

• A pair of dental forceps and an artery clamp (both stolen property).

With these our excellent M.O. Major Ramsay coped with dysentery, beri-beri, malaria, gunshot wounds, jungle sores, the aftermath of amputations, cholera, smallpox, pellagra, broken bones, toothache, two cases of leprosy, and probably a lot more I never knew about. If you required an "operation" you were expected to provide a razor blade - there was, of course, no sort of anaesthetic of any kind. If you had to have a tooth out, you bit with the sore tooth on a knife handle until the tooth felt numb, then the Major whipped it out as fast as he could.

Also from Wilding's memoir a mention of two men who helped run the hospital before and after Major Ramsay was released from solitary confinement:

Lieutenant Brian Horncastle of the Kings Regiment. A man who was always kind and helpful and always quiet about it. He was troubled about the danger of jungle sores (this before we had our doctor available) and experimented on his own with carbolic. His sores became gangrenous and he died in February 1944.

Sergeant Stanley Scruton also of the Kings Regiment. A bricklayer's labourer by trade. Before (and a little time after) Major Ramsay was let out of solitary, he ran the "Hospital" with much compassion and very little knowledge. He died early in 1944. He was a splendid chap. I am sure that his death was, at least in part, due to frustration, because he could do so little for the charges in his care.

From Charles Coubrough's book, 'Memories of a Perpetual Second Lieutenant':

"In early 1944 I found myself in the prison hospital being treated for suppurating sores on my backside. I had to lie on my front the whole time. Colonel MacKenzie diagnosed my condition as scabies. He sent me to see Raymond Ramsay who treated me with his now famous 'bluestones'. It was extremely painful, but I didn't mind one bit, as it it was so much better than the dreadful itching I was experiencing before. Major Ramsay was a real hero in Rangoon Jail."

From Kenneth MacKenzie's book 'Operation Rangoon Jail':

"There were several Indian doctors in Rangoon who helped me considerably in the early months of incarceration. Major Kilgour had died and this had left me alone as the sole British medic. Later we were joined by Major Raymond Ramsay, who did really splendid work, coming as he did, at a time when the rest of us were ill and exhausted."

Ramsay also helped MacKenzie in clearing an outbreak of cholera from the jail, treating the sick men himself and taking responsibility for the burning of the dead in order to eliminate the disease completely from the prison. He also treated some badly burnt American airmen who had been shot down over Rangoon towards the end of 1944 and ably assisted MacKenzie in an operation to save the life of the senior Chinese POW, General H. C. Chi. The General had been attacked by one of his own men in the jail and the resulting stab wound had punctured his bowel, after an operation lasting about an hour and using only rudimentary instruments and medicines, the British doctors had done all they could.

From Philip Stibbe's book 'Return via Rangoon':

"At last towards the end of the year, the Japanese released Major Raymond Ramsay from the solitary block. His arrival now filled us with optimism. He exuded an atmosphere of confidence and efficiency and the debt we survivors owe to him is inestimable. His arrival in Six block proved to be a turning point and slowly the death rate fell."

"Soon after Major Ramsay came to Six Block, the Japanese sent in two American airmen who had been shot down near Rangoon. They were terribly burnt and had been kept in solitary for sometime without having any treatment for their burns. Their wounds were a mass of maggots and the stench was so foul the medical orderlies had to work in relays, but the Major, with superb determination worked on them without stopping."

From Denis Gavin's book 'Quiet Jungle, Angry Sea':

"Jungle sores were a nightmare to many of us. I only had one and not for very long. There were two kinds, male and female, although I don't know if these names were meant literally. The male could burrow right in to the skin, sometimes reaching the bone, while the female spread out more across the skin to make a big wide hole.

I took my sore to the compound doctor, who scraped away the putrefied flesh which didn't seem to hurt that much. He then poured a liberal dose of some burning blue ointment onto my sore which sent me dancing and yelping around the ward. I had no more trouble, but probably would not have gone back if I had, as the cure was worse than the sore."

"At last towards the end of the year, the Japanese released Major Raymond Ramsay from the solitary block. His arrival now filled us with optimism. He exuded an atmosphere of confidence and efficiency and the debt we survivors owe to him is inestimable. His arrival in Six block proved to be a turning point and slowly the death rate fell."

"Soon after Major Ramsay came to Six Block, the Japanese sent in two American airmen who had been shot down near Rangoon. They were terribly burnt and had been kept in solitary for sometime without having any treatment for their burns. Their wounds were a mass of maggots and the stench was so foul the medical orderlies had to work in relays, but the Major, with superb determination worked on them without stopping."

From Denis Gavin's book 'Quiet Jungle, Angry Sea':

"Jungle sores were a nightmare to many of us. I only had one and not for very long. There were two kinds, male and female, although I don't know if these names were meant literally. The male could burrow right in to the skin, sometimes reaching the bone, while the female spread out more across the skin to make a big wide hole.

I took my sore to the compound doctor, who scraped away the putrefied flesh which didn't seem to hurt that much. He then poured a liberal dose of some burning blue ointment onto my sore which sent me dancing and yelping around the ward. I had no more trouble, but probably would not have gone back if I had, as the cure was worse than the sore."

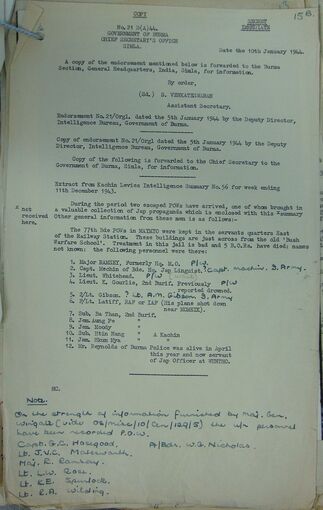

A document showing some POW's present at Maymyo..

So this is what we know of Major Raymond Ramsay and his time as a Chindit and POW in WW2 and as a surgeon after the war. The document shown to the left is a list of the Chindit officers known to be held at the Maymyo concentration camp. It was at Maymyo that the Japanese gathered all the captured Chindits from 1943, before transporting them all down to their final destination, Rangoon Jail. (Please click on the image to enlarge).

Raymond Ramsay died in April 1996 at the age of 79. Here is a transcription of his obituary published in either the Times or Telegraph newspaper that year:

Raymond Ramsay, who had died aged 79, displayed outstanding ingenuity as a medical officer and a POW in Rangoon Gaol. After the Second World War, he was one of the consultant surgeons who helped build the National Health Service. Certainly his deftness of approach in dealing with colleagues and his experience in medical practice owed a great deal to his wartime adventures.

Ramsay volunteered for active service at the outbreak of hostilities. As a recently qualified doctor, he was commissioned in to the Royal Army Medical Corps and posted to India. In 1941 he was due to take some leave, but a fractured arm prevented him from travelling to England. Instead, he was promoted to the rank of Major and was appointed Brigade Medical Officer to Wingate's first expedition into Burma.

Despite their fighting spirit in the jungle, the expedition was heavily outnumbered by the Japanese. After incurring heavy losses, Wingate ordered that they divide into several dispersal groups to get back to the British line. Ramsay took command of one. They were crossing a tributary of the Chindwin River, and were in sight of British troops when they were ambushed by the Japanese who opened fire at point blank range. Ramsay was shot in the heel, but was lucky enough to have his wound attended to by a benign Japanese orderly, who ordered up an elephant to transport him to captivity.

Ramsay arrived at Rangoon Gaol in 1943. As well as providing much needed medical skills, he did an enormous amount to increase morale. Comrades recall his characteristic style and suave demeanour that helped to give them "a great sense of confidence". Indeed Ramsay's hospital ward, known as 6th Block, became a rallying point for officers and men.

Most of them were too weak for the endless hard labour, and he orgainsed a rota of short stays in the ward to give the men a brief respite and build up their health. This required charm, wit and considerable diplomacy in negotiations with his captors. Ramsay had to be extremely inventive to secure any medical supplies. Men from work parties found some rocks which they called 'bluestone'. He discovered that these acted as an antidote for jungle sores when crushed and mixed with water.

Guards were bribed to bring in poppies which were fermented to produce a crude form of morphine which reduced the effects of cholera and dysentery. Old razor blades were used for primitive operations and splints were manufactured from old bamboo to heal broken limbs.

After over two years in captivity, with the war now ending, the Japanese prepared to evacuate the gaol. They gave Ramsay the unenviable task of dividing the men into those who could march and those who were too weak to make a journey. Fortunately those who stayed were spared, but those who marched out had a perilous journey amid the closing stages of battle as the Allied troops advanced. They were eventually rescued by an advancing battalion of the West Yorkshire Regiment.

Raymond Ramsay died in April 1996 at the age of 79. Here is a transcription of his obituary published in either the Times or Telegraph newspaper that year:

Raymond Ramsay, who had died aged 79, displayed outstanding ingenuity as a medical officer and a POW in Rangoon Gaol. After the Second World War, he was one of the consultant surgeons who helped build the National Health Service. Certainly his deftness of approach in dealing with colleagues and his experience in medical practice owed a great deal to his wartime adventures.

Ramsay volunteered for active service at the outbreak of hostilities. As a recently qualified doctor, he was commissioned in to the Royal Army Medical Corps and posted to India. In 1941 he was due to take some leave, but a fractured arm prevented him from travelling to England. Instead, he was promoted to the rank of Major and was appointed Brigade Medical Officer to Wingate's first expedition into Burma.

Despite their fighting spirit in the jungle, the expedition was heavily outnumbered by the Japanese. After incurring heavy losses, Wingate ordered that they divide into several dispersal groups to get back to the British line. Ramsay took command of one. They were crossing a tributary of the Chindwin River, and were in sight of British troops when they were ambushed by the Japanese who opened fire at point blank range. Ramsay was shot in the heel, but was lucky enough to have his wound attended to by a benign Japanese orderly, who ordered up an elephant to transport him to captivity.

Ramsay arrived at Rangoon Gaol in 1943. As well as providing much needed medical skills, he did an enormous amount to increase morale. Comrades recall his characteristic style and suave demeanour that helped to give them "a great sense of confidence". Indeed Ramsay's hospital ward, known as 6th Block, became a rallying point for officers and men.

Most of them were too weak for the endless hard labour, and he orgainsed a rota of short stays in the ward to give the men a brief respite and build up their health. This required charm, wit and considerable diplomacy in negotiations with his captors. Ramsay had to be extremely inventive to secure any medical supplies. Men from work parties found some rocks which they called 'bluestone'. He discovered that these acted as an antidote for jungle sores when crushed and mixed with water.

Guards were bribed to bring in poppies which were fermented to produce a crude form of morphine which reduced the effects of cholera and dysentery. Old razor blades were used for primitive operations and splints were manufactured from old bamboo to heal broken limbs.

After over two years in captivity, with the war now ending, the Japanese prepared to evacuate the gaol. They gave Ramsay the unenviable task of dividing the men into those who could march and those who were too weak to make a journey. Fortunately those who stayed were spared, but those who marched out had a perilous journey amid the closing stages of battle as the Allied troops advanced. They were eventually rescued by an advancing battalion of the West Yorkshire Regiment.

The obituary concludes:

Raymond Ramsay was born into an English family at Peddie, South Africa on August 19th 1916. They settled in London in the 1920's and Ramsay went to St. Marylebone Grammar School before going on to Barts Hospital in 1932. He qualified as a doctor six years later.

After his wartime troubles he recuperated in India. As the first medical officer to return from Japanese captivity he was summoned to Southampton to advise over the treatment of former POW's. A number of psychiatrists had been provided, but Ramsay insisted that they would not be needed. In the next door tent was the plastic surgeon Stewart Harrison, who was to become one of Ramsay's colleagues at Windsor.

He returned to Barts in 1946 to become Senior Demonstrator in Anatomy. A friend stopped him by the fountain to show him the evening paper with news of his appointment as MBE. Unknown to him, his future wife was also at the same hospital, training to be an almoner. They did not meet until five years later.

Ramsay then went to the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital, gained his FRCS (Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons) in 1949 and became Senior Surgical Registrar at the Bristol Royal Infirmary in 1951. Two years later he was appointed Consultant General Surgeon to the Windsor Group of Hospitals. His contribution to surgery was immense. An outstanding clinician with the ability to put his patients at ease, Ramsay helped to pioneer new surgical techniques in the provinces.

He was amongst the first to develop the use of X-ray during surgery to provide up-to-the-minute information on whether the procedure being undertaken was improving the patient's condition. As a result of his studies under Thomas Dunhill at Barts, he was also at the forefront of developments in thyroid surgery. Ramsay retained his good humour and easy charm in all circumstances, but was rarely happier than when on his beloved yacht, which he kept on the Isle of Wight. He was a long-term member of the Royal Solent Yacht Club. He married Lillian Bateman in 1952 and had three sons.

Subnote

Raymond's wife Lillian (also appointed MBE in 2007) devoted her life to helping the less privileged in our society, especially in regard to sick or disabled children. Here is a link to her own obituary, published in the Daily Telegraph and is in my view a fitting and deserved addition to this story:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/medicine-obituaries/7756804/Lillian-Ramsay.html

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Bev Daily, Tony Grewal and Raymond's grandson Will, for their fantastic help in compiling this story about one of the most heroic, yet selfless members of Wingate's expedition in 1943. As one final way of honouring the contribution made by Major Ramsay that year, here is the poem read out as part of the eulogy at his funeral, 'Crossing the Bar', by Alfred Lord Tennyson. Tennyson wrote this poem in 1889 and it has traditionally been used to conclude any collection of his works in the print form since then.

Raymond Ramsay was born into an English family at Peddie, South Africa on August 19th 1916. They settled in London in the 1920's and Ramsay went to St. Marylebone Grammar School before going on to Barts Hospital in 1932. He qualified as a doctor six years later.

After his wartime troubles he recuperated in India. As the first medical officer to return from Japanese captivity he was summoned to Southampton to advise over the treatment of former POW's. A number of psychiatrists had been provided, but Ramsay insisted that they would not be needed. In the next door tent was the plastic surgeon Stewart Harrison, who was to become one of Ramsay's colleagues at Windsor.

He returned to Barts in 1946 to become Senior Demonstrator in Anatomy. A friend stopped him by the fountain to show him the evening paper with news of his appointment as MBE. Unknown to him, his future wife was also at the same hospital, training to be an almoner. They did not meet until five years later.

Ramsay then went to the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital, gained his FRCS (Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons) in 1949 and became Senior Surgical Registrar at the Bristol Royal Infirmary in 1951. Two years later he was appointed Consultant General Surgeon to the Windsor Group of Hospitals. His contribution to surgery was immense. An outstanding clinician with the ability to put his patients at ease, Ramsay helped to pioneer new surgical techniques in the provinces.

He was amongst the first to develop the use of X-ray during surgery to provide up-to-the-minute information on whether the procedure being undertaken was improving the patient's condition. As a result of his studies under Thomas Dunhill at Barts, he was also at the forefront of developments in thyroid surgery. Ramsay retained his good humour and easy charm in all circumstances, but was rarely happier than when on his beloved yacht, which he kept on the Isle of Wight. He was a long-term member of the Royal Solent Yacht Club. He married Lillian Bateman in 1952 and had three sons.

Subnote

Raymond's wife Lillian (also appointed MBE in 2007) devoted her life to helping the less privileged in our society, especially in regard to sick or disabled children. Here is a link to her own obituary, published in the Daily Telegraph and is in my view a fitting and deserved addition to this story:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/medicine-obituaries/7756804/Lillian-Ramsay.html

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Bev Daily, Tony Grewal and Raymond's grandson Will, for their fantastic help in compiling this story about one of the most heroic, yet selfless members of Wingate's expedition in 1943. As one final way of honouring the contribution made by Major Ramsay that year, here is the poem read out as part of the eulogy at his funeral, 'Crossing the Bar', by Alfred Lord Tennyson. Tennyson wrote this poem in 1889 and it has traditionally been used to conclude any collection of his works in the print form since then.

The Crest and motto of the RAMC.

Crossing the Bar

Sunset and evening star,

And one clear call for me!

And may there be no moaning of the bar,

When I put out to sea,

But such a tide as moving seems asleep,

Too full for sound and foam,

When that which drew from out the boundless deep

Turns again home.

Twilight and evening bell,

And after that the dark!

And may there be no sadness or farewell,

When I embark;

For tho' from out our bourne of Time and Place

The flood may bear me far,

I hope to see my Pilot face to face

When I have crost the bar.

Sunset and evening star,

And one clear call for me!

And may there be no moaning of the bar,

When I put out to sea,

But such a tide as moving seems asleep,

Too full for sound and foam,

When that which drew from out the boundless deep

Turns again home.

Twilight and evening bell,

And after that the dark!

And may there be no sadness or farewell,

When I embark;

For tho' from out our bourne of Time and Place

The flood may bear me far,

I hope to see my Pilot face to face

When I have crost the bar.

Update 29/08/2013.

Another POW present in Rangoon Jail at the time, 2nd Lieutenant Kenneth Horner, a United States Airforce Officer and Navigator, had been asked to try and make eating utensils, plates and other metal work for use within the jail, he was encouraged to do this by Major Nigel Loring one of the senior British Officers in the prison.

Here is an extract from Kenneth Horner's book, entitled 'MIA' (Missing in Action), telling the story of how he helped manufacture a medical instrument for Raymond Ramsay:

"Major Ramsey asked us to make a troche cannula. First of all, we didn't know what a troche cannula was and besides that, we couldn't really make one with the tools available.

Major Ramsey explained to us that it was a medical device used to pierce body cavities. It consists of a small channel with a plunger through it. The plunger and the channel together have a three cornered point. If he had one he could help all the beri beri patients by draining the excess water from their testicles. "It doesn't have to be perfect" he said, "however it has to be small and extremely sharp so I can pierce the skin.

Ken Spurlock and I agreed to try. A tin can was the only metal we could think of that would be thin enough to make the channel and I hadn't seen one in over two years. We told the prison work parties to look out for one and in two days we had several cans to work with.

Fabricating the channel, as we designed it, required a blank with dimensions far beyond our ability to calculate. We envisioned a small diameter wire with the metal wrapped around it. The metal would meet in a butt joint so the finished channel would have a crack the length of the tube which was 2 inches long.

We cut several half inch wide pieces of metal and practised several ways to end up with a minimum space at the butt joint. After several attempts we succeeded in getting a tube through which a wire could slide rather tightly. Major Ramsey monitored our progress daily and insisted we hurry. His impatience convinced us that he believed the device would help alleviate the pain and discomfort of some of his patients.

Finally, the only thing that remained to complete the device was to make a handle on one end and a very sharp point on the other. To create the point we tried all sorts of abrasives: the concrete work floor, the brick wall between the compounds and the wall of the main building. Of course, it was slow and painstaking work, yet we succeeded in making a long sharp point that could easily puncture human skin and enter a body cavity. Dr Ramsey used it and said it was as effective as any he had used in his own private practice."

Definition of Trocar or Trois cannula:

A sharp, pointed rod that fits inside a tube. It is used to pierce the skin and the wall of a cavity or canal in the body to aspirate fluids, instill a medication or solution, or to guide the placement of a soft catheter. The trocar is usually removed, and the catheter, tube, or instrument is left in place. It can also be used to puncture the wall of a body cavity and withdraw fluid or gas. An especially large bore trocar and cannula is often used by veterinary surgeons in the treatment of bloat in cattle.

My thanks must go to Kenneth 'Jack' Horner and his daughter Connie for allowing me to quote from the book 'MIA' (Missing in Action). For more information about Jack's book, please click on the link below:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/MIA-Missing-survival-Emperor-Hirohito/dp/0615734022/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1377809055&sr=1-1&keywords=mia+horner

Another POW present in Rangoon Jail at the time, 2nd Lieutenant Kenneth Horner, a United States Airforce Officer and Navigator, had been asked to try and make eating utensils, plates and other metal work for use within the jail, he was encouraged to do this by Major Nigel Loring one of the senior British Officers in the prison.

Here is an extract from Kenneth Horner's book, entitled 'MIA' (Missing in Action), telling the story of how he helped manufacture a medical instrument for Raymond Ramsay:

"Major Ramsey asked us to make a troche cannula. First of all, we didn't know what a troche cannula was and besides that, we couldn't really make one with the tools available.

Major Ramsey explained to us that it was a medical device used to pierce body cavities. It consists of a small channel with a plunger through it. The plunger and the channel together have a three cornered point. If he had one he could help all the beri beri patients by draining the excess water from their testicles. "It doesn't have to be perfect" he said, "however it has to be small and extremely sharp so I can pierce the skin.

Ken Spurlock and I agreed to try. A tin can was the only metal we could think of that would be thin enough to make the channel and I hadn't seen one in over two years. We told the prison work parties to look out for one and in two days we had several cans to work with.

Fabricating the channel, as we designed it, required a blank with dimensions far beyond our ability to calculate. We envisioned a small diameter wire with the metal wrapped around it. The metal would meet in a butt joint so the finished channel would have a crack the length of the tube which was 2 inches long.

We cut several half inch wide pieces of metal and practised several ways to end up with a minimum space at the butt joint. After several attempts we succeeded in getting a tube through which a wire could slide rather tightly. Major Ramsey monitored our progress daily and insisted we hurry. His impatience convinced us that he believed the device would help alleviate the pain and discomfort of some of his patients.

Finally, the only thing that remained to complete the device was to make a handle on one end and a very sharp point on the other. To create the point we tried all sorts of abrasives: the concrete work floor, the brick wall between the compounds and the wall of the main building. Of course, it was slow and painstaking work, yet we succeeded in making a long sharp point that could easily puncture human skin and enter a body cavity. Dr Ramsey used it and said it was as effective as any he had used in his own private practice."

Definition of Trocar or Trois cannula:

A sharp, pointed rod that fits inside a tube. It is used to pierce the skin and the wall of a cavity or canal in the body to aspirate fluids, instill a medication or solution, or to guide the placement of a soft catheter. The trocar is usually removed, and the catheter, tube, or instrument is left in place. It can also be used to puncture the wall of a body cavity and withdraw fluid or gas. An especially large bore trocar and cannula is often used by veterinary surgeons in the treatment of bloat in cattle.

My thanks must go to Kenneth 'Jack' Horner and his daughter Connie for allowing me to quote from the book 'MIA' (Missing in Action). For more information about Jack's book, please click on the link below:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/MIA-Missing-survival-Emperor-Hirohito/dp/0615734022/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1377809055&sr=1-1&keywords=mia+horner

Sgt. Harold Palmer of 8 Column.

Sgt. Harold Palmer of 8 Column.

Update 14/03/2016.

Sergeant Harold Palmer was a member of 8 Column on Operation Longcloth. He was captured by the Japanese after his platoon was ambushed by the enemy at the Irrawaddy River in late April 1943. Harold spent the next two years of his life as a prisoner of war. Whilst inside Block 6 of Rangoon Jail he was heavily involved in tending the sick and wounded, including many of his Chindit comrades. With hardly any medical materials or drugs available, men such as Harold Palmer made a valiant effort to care for these men, until finally the Medical Officers were released from solitary confinement.

Raymond Ramsay's release from the solitary confinement cells was a momentous moment for the prisoners in Block 6, but sadly came just too late for many Chindit casualties. Harold Palmer remembered those terrible early days inside Rangoon Jail and wrote about them his diary; here is how he recalled the moment of Major Ramsay's liberation:

Every day death took another, sometimes two, even four one day and there was nothing we could do to prevent it. Medicine scarce, disinfectant almost nil with flies everywhere, sanitation was hopeless. The dark despair of those days is hard to put down on paper. Beri Beri was responsible for most deaths in those early days.

The diet of rice and a little vegetables did nothing to help. The Japs began to get concerned over the death rate and tried to cooperate, but they expected wonders to be done with the little medicines they gave us. A RAMC Colonel[1] in the other prison block was allowed to visit our compound about once a fortnight, but he was terrifically handicapped by lack of equipment. He gave us advice on the treatment of the various diseases, but still the death rate mounted.

Jungle sores of terrible sizes were seen everywhere. We had 68 cases out of the 160 people at one time. A small cut developed rapidly to a deadly one; very painful and the stench was terrible. The lads who volunteered for the job of orderlies were real heroes. The sights they saw, the filth that surrounded them, the lack of gauze, bandages and proper equipment would have broken the hearts of experienced orderlies. So is it strange how many of these voluntary orderlies died in the jail!

We got to know that our Medical Officer, Major Ramsey had been taken prisoner and we began to pray for the time when he came out of solitary confinement. The day he came out, he assumed a load of responsibility which would have crushed most men, but many men owe their lives to Major Ramsey’s skills and work.

Often he must have felt like throwing in the sponge, so little help was given by the Japs. But he stuck grimly to the task that would sicken most medicine men and by the beginning of 1945 he, in conjunction with Colonel McKenzie had disease to a minimum. They even fought a cholera outbreak when everyone feared the worst; 14 deaths in 2 days, and yet they stamped it out with the most primitive weapon with which to fight the dreaded plague.

They performed an arm amputation on an airman[2], with a penknife, cotton and needle. The difficulties under which they worked are known only to themselves, used as they were to the best equipment, but now reduced to surgery and medicine of hundreds of years ago.

[1] This was Colonel K.P. MacKenzie who had been captured in 1942 during the retreat from Burma.

[2] This was American Airman, Richard A. Montgomery of Riverside, California.

My thanks go to Claire McHenry, the granddaughter of Harold Palmer for permission to use the above extract from her grandfather's personal diary.

Sergeant Harold Palmer was a member of 8 Column on Operation Longcloth. He was captured by the Japanese after his platoon was ambushed by the enemy at the Irrawaddy River in late April 1943. Harold spent the next two years of his life as a prisoner of war. Whilst inside Block 6 of Rangoon Jail he was heavily involved in tending the sick and wounded, including many of his Chindit comrades. With hardly any medical materials or drugs available, men such as Harold Palmer made a valiant effort to care for these men, until finally the Medical Officers were released from solitary confinement.

Raymond Ramsay's release from the solitary confinement cells was a momentous moment for the prisoners in Block 6, but sadly came just too late for many Chindit casualties. Harold Palmer remembered those terrible early days inside Rangoon Jail and wrote about them his diary; here is how he recalled the moment of Major Ramsay's liberation:

Every day death took another, sometimes two, even four one day and there was nothing we could do to prevent it. Medicine scarce, disinfectant almost nil with flies everywhere, sanitation was hopeless. The dark despair of those days is hard to put down on paper. Beri Beri was responsible for most deaths in those early days.

The diet of rice and a little vegetables did nothing to help. The Japs began to get concerned over the death rate and tried to cooperate, but they expected wonders to be done with the little medicines they gave us. A RAMC Colonel[1] in the other prison block was allowed to visit our compound about once a fortnight, but he was terrifically handicapped by lack of equipment. He gave us advice on the treatment of the various diseases, but still the death rate mounted.

Jungle sores of terrible sizes were seen everywhere. We had 68 cases out of the 160 people at one time. A small cut developed rapidly to a deadly one; very painful and the stench was terrible. The lads who volunteered for the job of orderlies were real heroes. The sights they saw, the filth that surrounded them, the lack of gauze, bandages and proper equipment would have broken the hearts of experienced orderlies. So is it strange how many of these voluntary orderlies died in the jail!

We got to know that our Medical Officer, Major Ramsey had been taken prisoner and we began to pray for the time when he came out of solitary confinement. The day he came out, he assumed a load of responsibility which would have crushed most men, but many men owe their lives to Major Ramsey’s skills and work.

Often he must have felt like throwing in the sponge, so little help was given by the Japs. But he stuck grimly to the task that would sicken most medicine men and by the beginning of 1945 he, in conjunction with Colonel McKenzie had disease to a minimum. They even fought a cholera outbreak when everyone feared the worst; 14 deaths in 2 days, and yet they stamped it out with the most primitive weapon with which to fight the dreaded plague.

They performed an arm amputation on an airman[2], with a penknife, cotton and needle. The difficulties under which they worked are known only to themselves, used as they were to the best equipment, but now reduced to surgery and medicine of hundreds of years ago.

[1] This was Colonel K.P. MacKenzie who had been captured in 1942 during the retreat from Burma.

[2] This was American Airman, Richard A. Montgomery of Riverside, California.

My thanks go to Claire McHenry, the granddaughter of Harold Palmer for permission to use the above extract from her grandfather's personal diary.

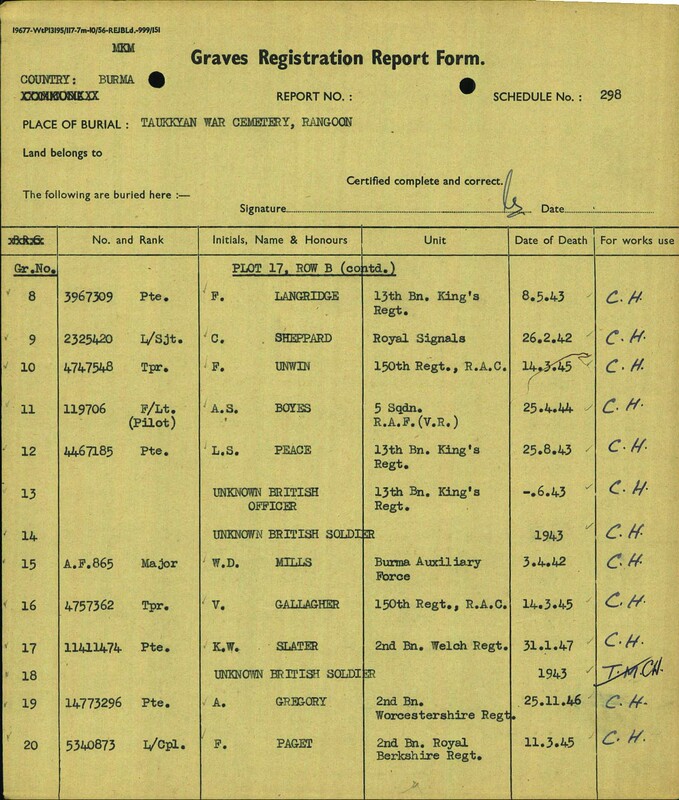

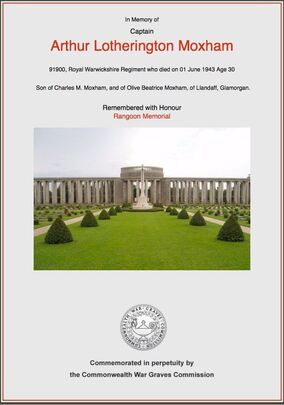

CWGC certificate for Arthur Moxham.

CWGC certificate for Arthur Moxham.

Update 06/12/2020.

Captain Arthur Lotherington Moxham

Captain Moxham (RIASC) was posted to us at Brigade Head Quarters during training and was the most organised chap I have ever known. There was no searching through pockets for him. If you had been bitten by a snake, a razor blade and potassium permanganate crystals were there, not usually but always. His jack-knife lurked in the dent of his bush hat, not usually, but always. Sadly he died on the expedition, I am not sure whether it was before or just after his party was put in the bag.

Quote from the written memoir of Lt. Willie Wilding, Brigade HQ Cipher Officer.

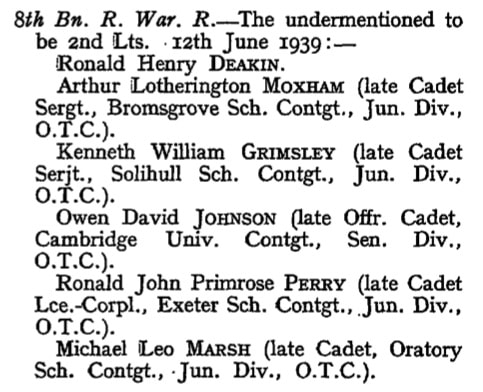

Arthur Lotherington Moxham was commissioned into the 8th Battalion of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment with the Army number 91900 on the 12th June 1939. He had previously held the rank of Sergeant at the Bromsgrove School (Worcestershire) Officer Cadet Contingent. A large draft of men from the 8th Warwick's had been used as reinforcements for the first Wingate expedition, arriving at the Saugor training camp in late September 1942. It is no known if Captain Moxham was originally part of this draft, or had been in India beforehand in his role with the Royal Indian Army Service Corps.

To read more about the 8th Warwick's and their pathway to serving on Operation Longcloth, please click on the following link: 8th Warwick's at Dunkirk

As mentioned in the main story on this page, Arthur Moxham served in Brigadier Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth and was part of the dispersal group led by Major Raymond Ramsay, when the Head Quarters broke up for the return journey to India in early April 1943. Almost nothing is known about Captain Moxham's fate after this point in time and no documentation has been found to offer any real answers or clues. We know that Major Ramsay was captured on the 11th April and after a period of travelling ended up serving just under two years as a prisoner of war inside Rangoon Jail.

The date of death registered for Arthur Moxham, the 1st June 1943 is an interesting one, as it represents a date shared by twenty other men from the first Wingate expedition, most of whom had been captured by the Japanese, but had never been recorded as such on any POW documentation. I believe the 1st June 1943 was an agreed date decided upon by the Army Investigation Bureau, which collected together all those who perished at the Maymyo Concentration Camp or the camps where Chindits had been held before that, such as Kalaw and Bhamo, but whose precise details had not been recorded and could not then be remembered by survivors after the war. It may also include those who left the Maymyo camp alive, but sadly were never to reach Rangoon Jail. To read more about these men and the Maymyo POW Camp, please click on the following link: More Cemeteries and Memorials

No grave for Captain Moxham was ever found, and for this reason he is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery. However, at Taukkyan War Cemetery, which is located on the northern outskirts of Rangoon, there is a grave marked to an unknown officer of the King's Regiment with the date of June 1943. It is possible, although we are likely never to know for sure, that this grave contains the remains of Arthur Moxham. This burial was moved to Taukkyan War Cemetery in 1951, alongside many others from the Mandalay Military Cemetery in order to concentrate the British graves located from all over northern Burma.

Other Chindits who had fallen into Japanese hands during Operation Longcloth and had perished as prisoners of war before reaching Rangoon Jail were buried at Mandalay, as this was the first main stop on the train journey from the Maymyo POW Camp to Rangoon. One such soldier was Frederick Langridge, who I know for sure was buried originally at Mandalay Military Cemetery, but then was re-interred at Taukkyan in 1951, at the same time as the remains from the grave of the unknown officer of the King's Regiment. The CWGC paperwork that shows the two graves were processed at the same time from the same location can be viewed in the gallery below. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Captain Arthur Lotherington Moxham

Captain Moxham (RIASC) was posted to us at Brigade Head Quarters during training and was the most organised chap I have ever known. There was no searching through pockets for him. If you had been bitten by a snake, a razor blade and potassium permanganate crystals were there, not usually but always. His jack-knife lurked in the dent of his bush hat, not usually, but always. Sadly he died on the expedition, I am not sure whether it was before or just after his party was put in the bag.

Quote from the written memoir of Lt. Willie Wilding, Brigade HQ Cipher Officer.

Arthur Lotherington Moxham was commissioned into the 8th Battalion of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment with the Army number 91900 on the 12th June 1939. He had previously held the rank of Sergeant at the Bromsgrove School (Worcestershire) Officer Cadet Contingent. A large draft of men from the 8th Warwick's had been used as reinforcements for the first Wingate expedition, arriving at the Saugor training camp in late September 1942. It is no known if Captain Moxham was originally part of this draft, or had been in India beforehand in his role with the Royal Indian Army Service Corps.