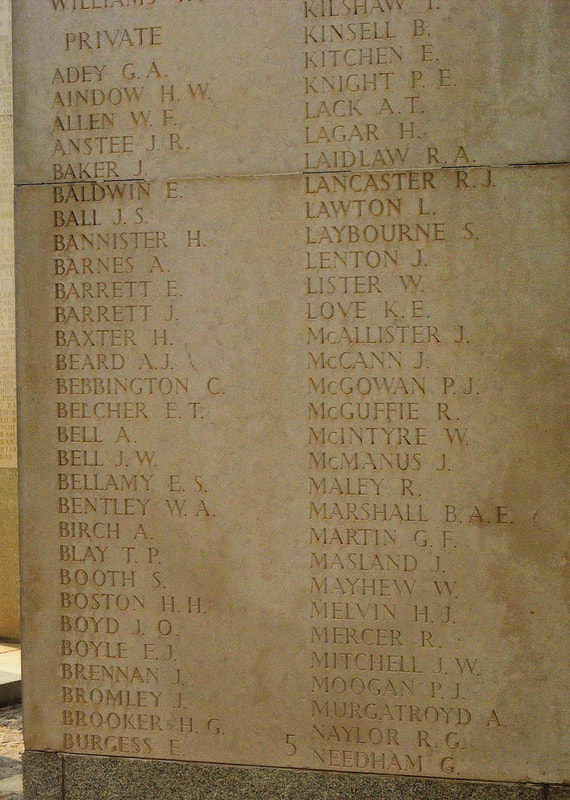

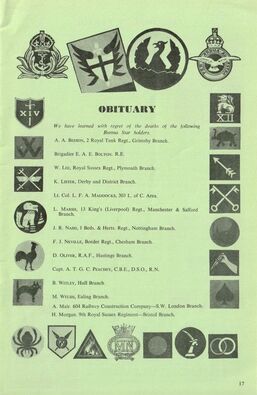

The Longcloth Roll Call

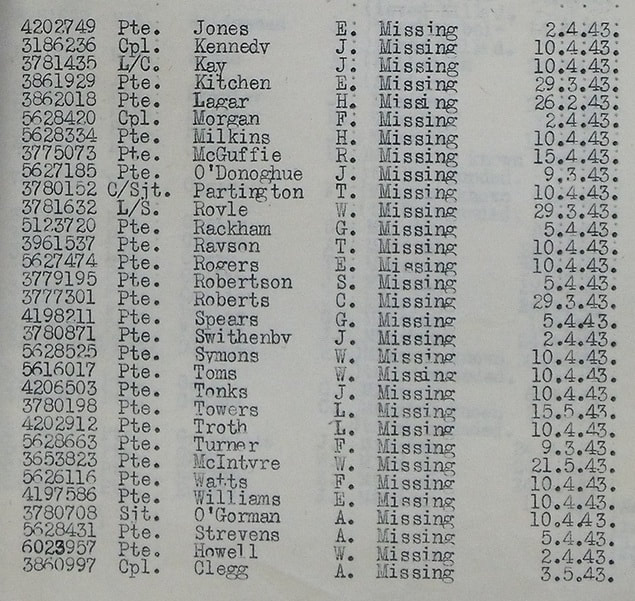

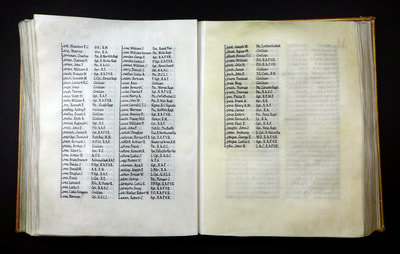

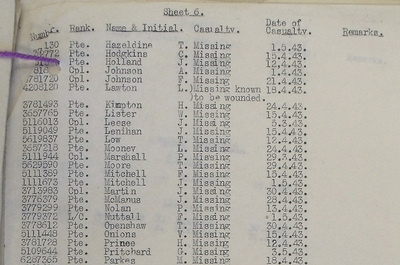

Surname K-O

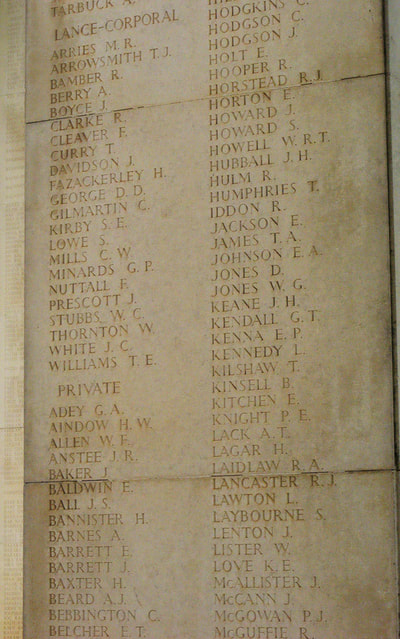

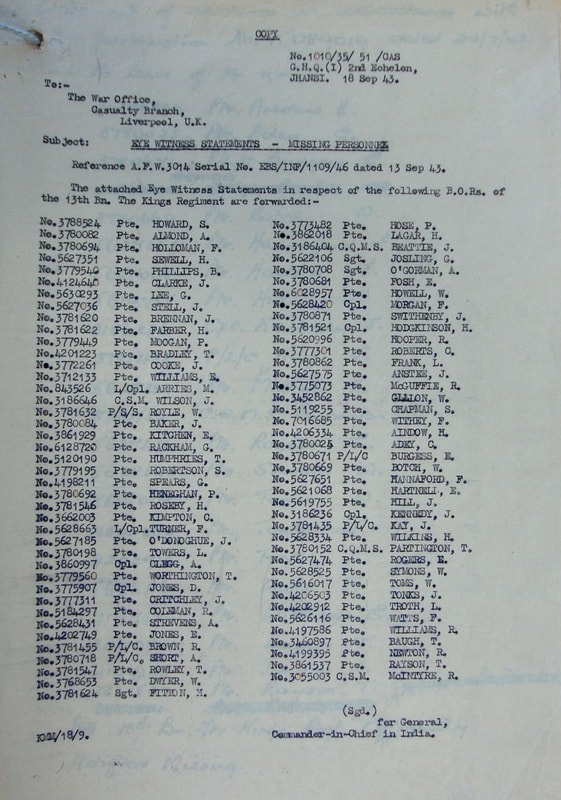

This section is an alphabetical roll of the men from Operation Longcloth. It takes its inspiration from other such formats available on the Internet, websites such as Special Forces Roll of Honour and of course the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC). The information shown comes from various different documents related to the first Chindit Operation in 1943. Apart from more obvious data, such as the serviceman's rank, number and regimental unit, other detail has been taken from associated war diaries, missing in action files and casualty witness statements. The vast majority of this type of information has been located at the National Archives and the relevant file references can be found in the section Sources and Knowledge on this website.

Sometimes, if the man in question became a prisoner of war more detail can be displayed showing his time whilst in Japanese hands. Other avenues for additional information are: books, personal diaries, veteran audio accounts and subsequent family input via letter, email and phone call.

The idea behind this page, is to include as many Longcloth participants as possible, even if there is only a small amount of information about their contribution to hand. Please click on any of the images to hopefully bring them forward on the page.

All information contained on this page is Copyright © Steve Fogden April 2014.

Sometimes, if the man in question became a prisoner of war more detail can be displayed showing his time whilst in Japanese hands. Other avenues for additional information are: books, personal diaries, veteran audio accounts and subsequent family input via letter, email and phone call.

The idea behind this page, is to include as many Longcloth participants as possible, even if there is only a small amount of information about their contribution to hand. Please click on any of the images to hopefully bring them forward on the page.

All information contained on this page is Copyright © Steve Fogden April 2014.

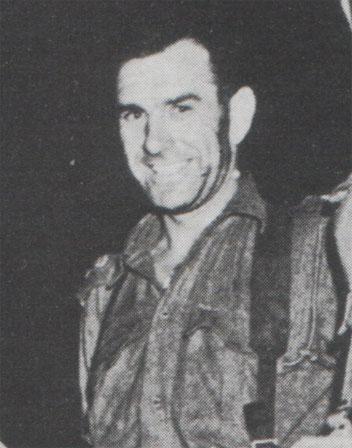

Joseph Kay.

Joseph Kay.

KAY, JOSEPH

Rank: Lance Corporal

Service No: 3781435

Date of Death: 02/09/1943

Age: 31

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

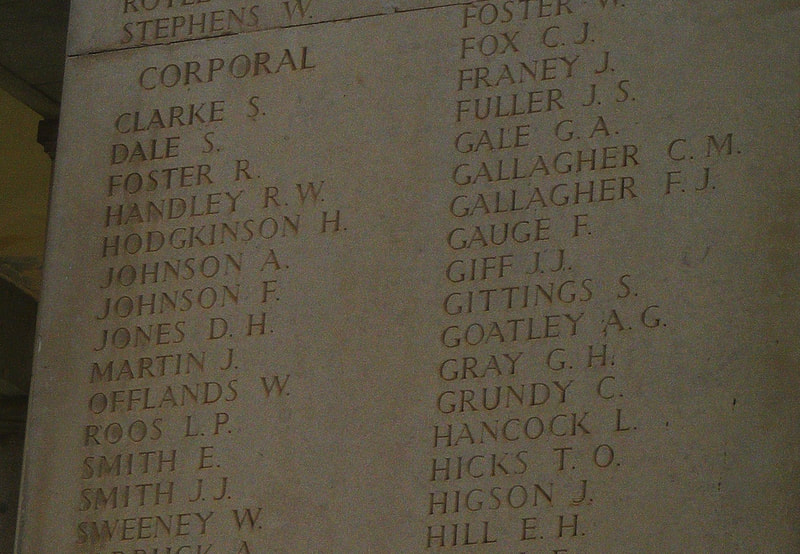

Memorial: Rangoon War Cemetery Grave: 6.B.7.

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2260190/kay,-joseph/

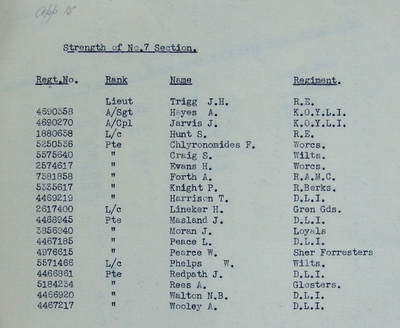

Chindit Column: 7

Other details:

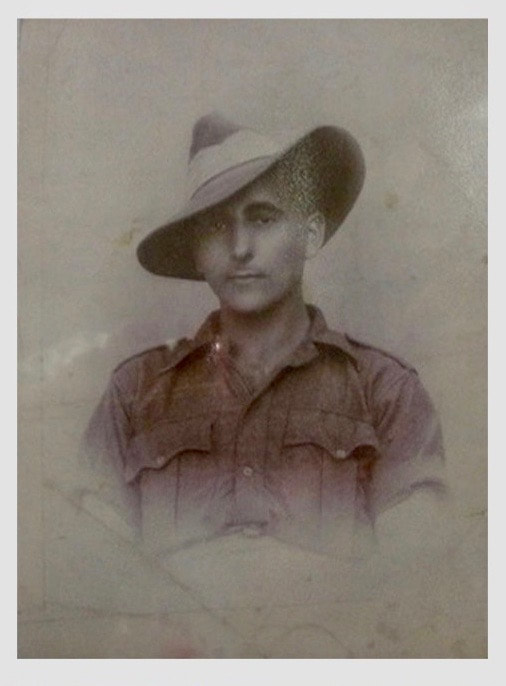

Joseph Kay was born on the 16th July 1912 and was the son of James Gilbert and Sarah Ann Kay from Ancoats, Manchester. James Kay worked as a printer and according to the 1939 Register, Joseph was still living with his parents at 5 Chaucer Street, Manchester and was working as a clothing salesman.

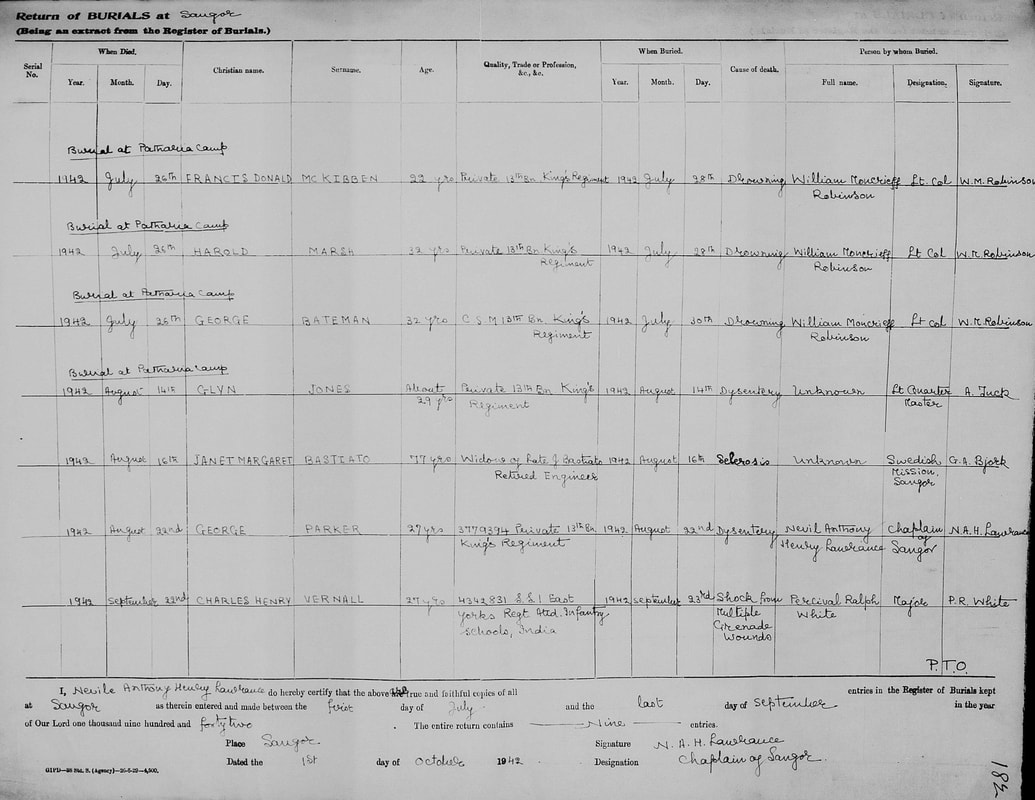

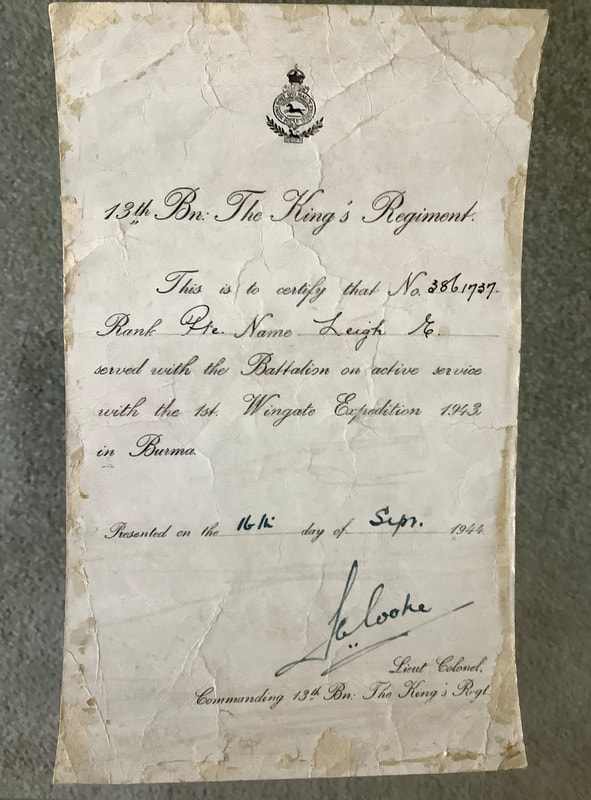

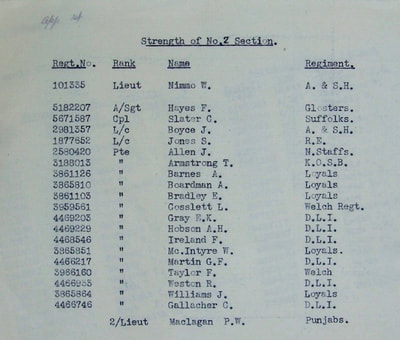

From Joseph's Army service number, 3781435, it seems highly likely that he was an original member of the 13th Battalion, the King's Regiment that voyaged overseas aboard the troopship, Oronsay on the 8th December 1941. After the battalion was given over to Brigadier Wingate in June 1942, Joseph was allocated to No. 7 Column and began his jungle warfare training at the Saugor camp in the Central Provinces of India. On Operation Longcloth, Joseph served as a section commander in one of the column's Rifle Platoons.

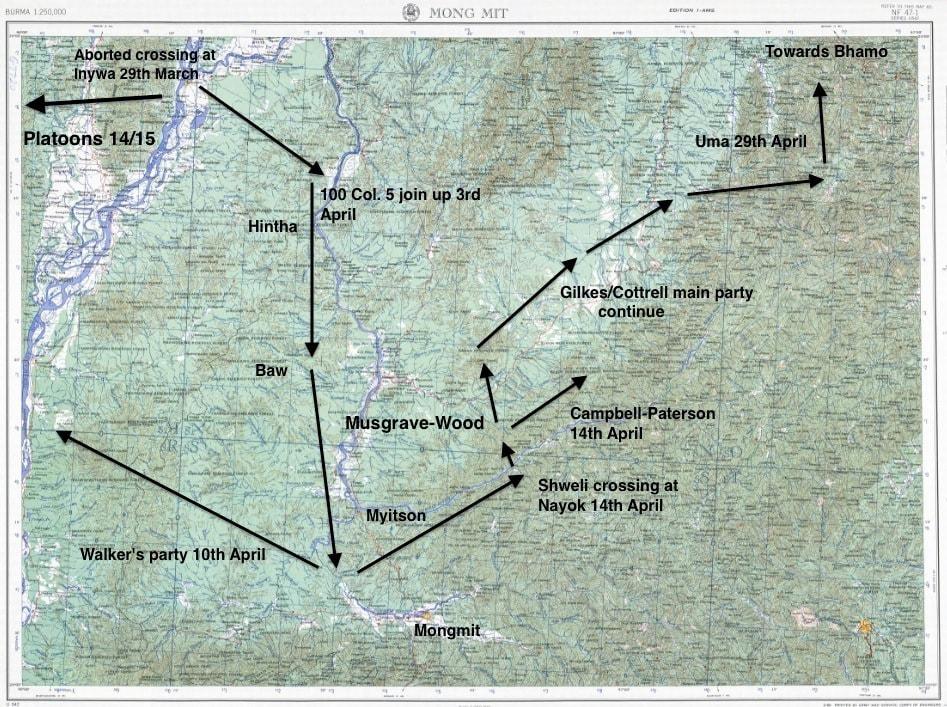

After dispersal was called around the 24/25th March 1943, Joseph was placed into the party commanded by Lt. Rex Walker. This was a group comprising soldiers who were already sick with disease or suffering from some sort of injury or wound. While the main body of No. 7 Column headed east in order to exit Burma via the Chinese Borders, Lt. Walker's dispersal party, due to the physical condition of its men, headed directly west in order to take the shortest possible route back to Allied held territory.

To read in more depth about Lt. Rex Walker's group, please click on the following link: Rex Walker's Dispersal Group 4

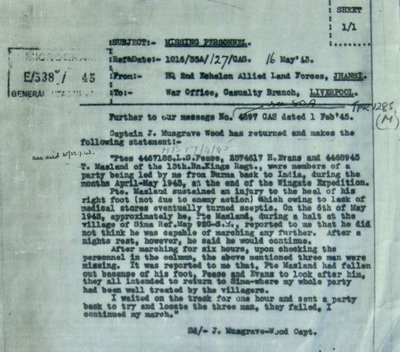

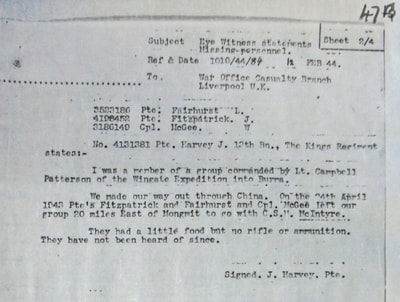

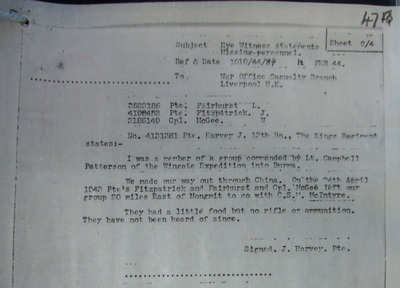

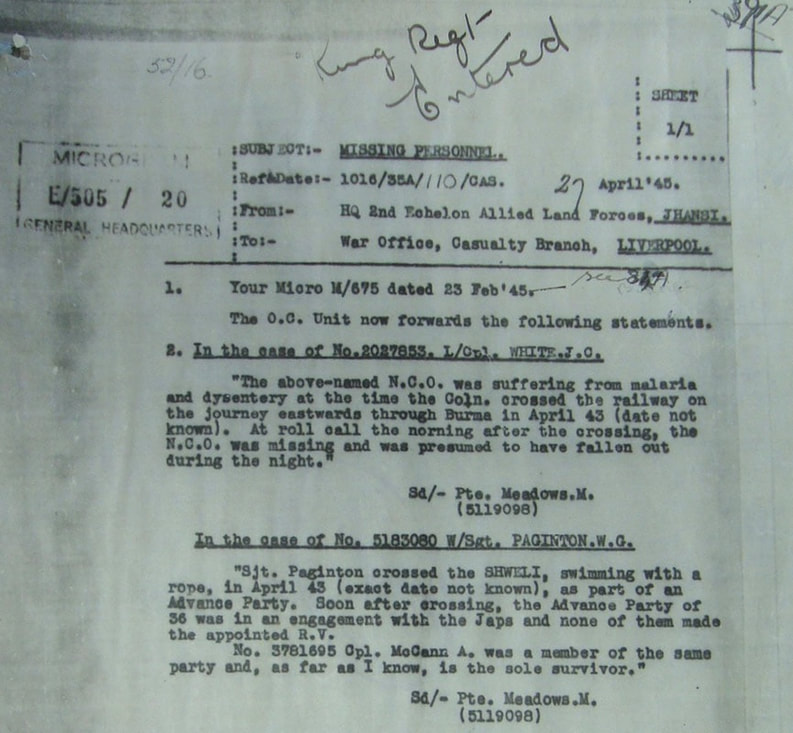

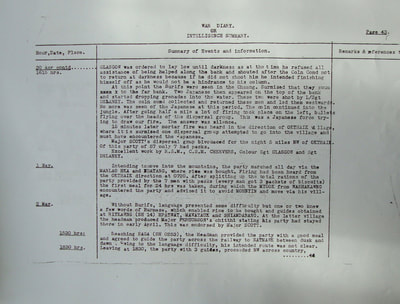

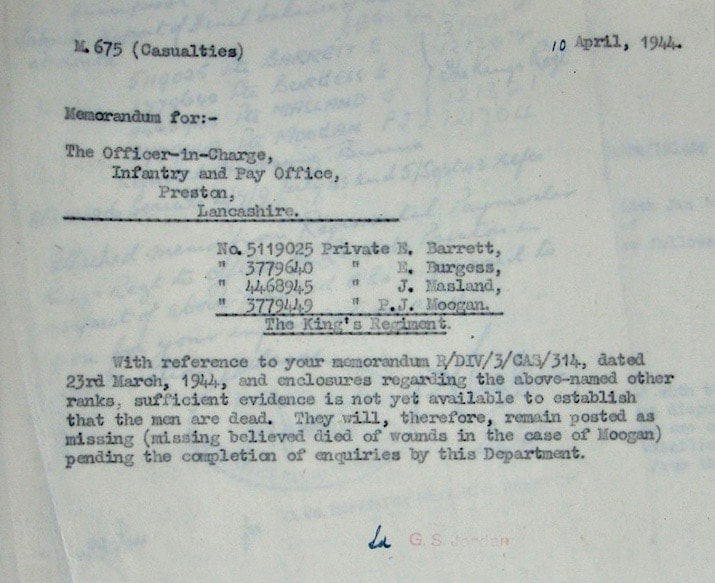

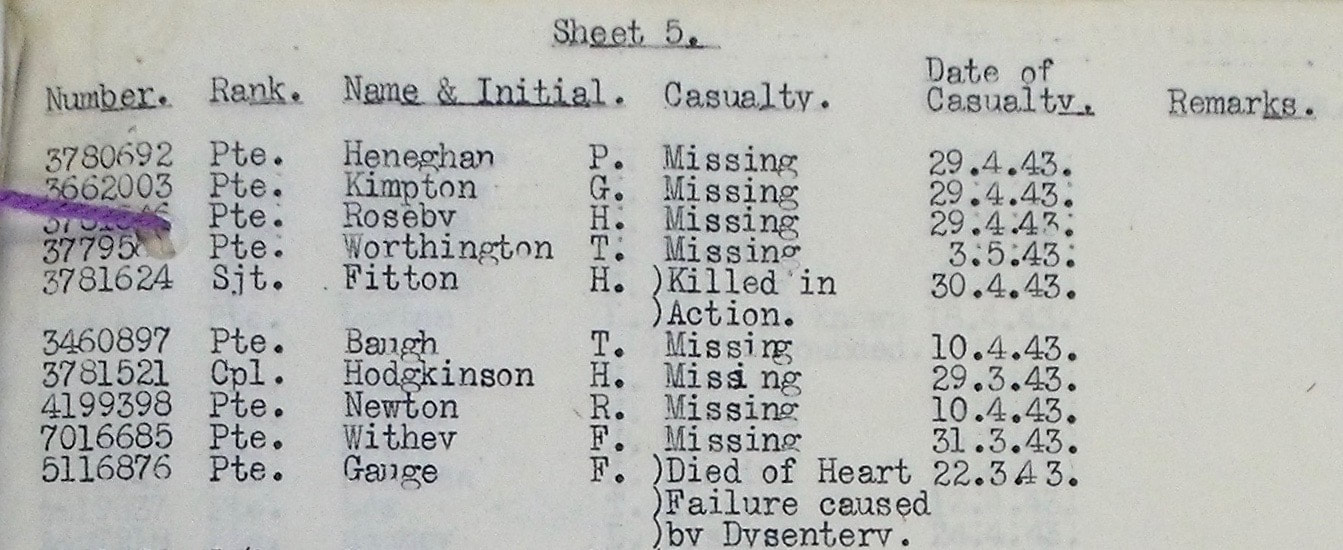

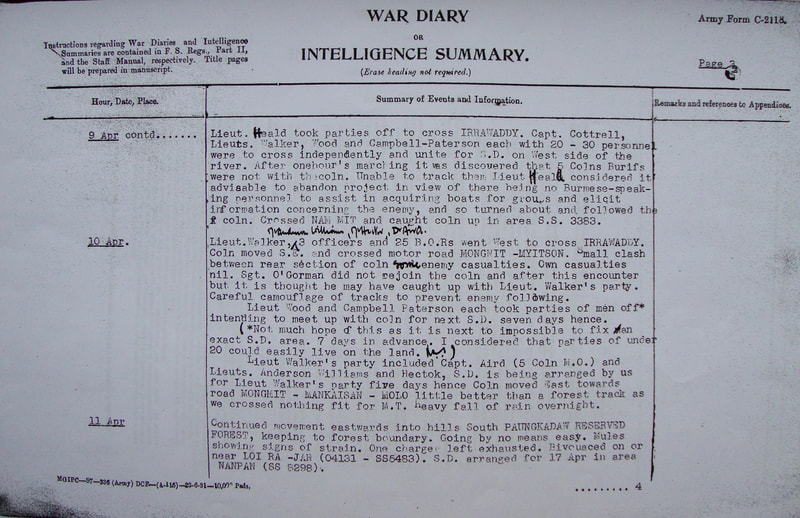

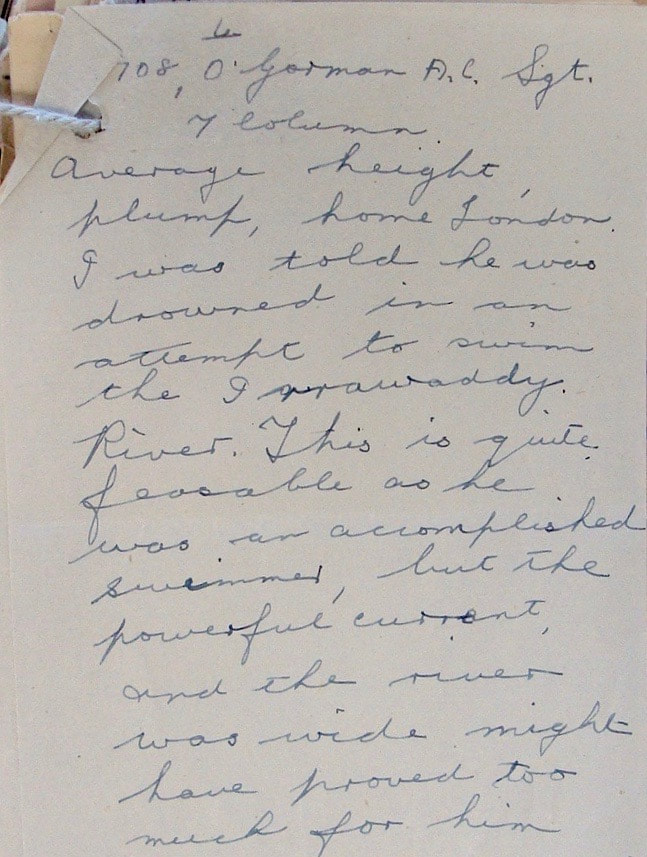

Joseph Kay was officially reported as missing in action on the 10th April 1943, while his dispersal group were preparing to make a crossing of the Irrawaddy River. A witness statement, given by No. 7 Column Adjutant, Captain Leslie Cottrell after the operation throws some light on the situation:

On April 10th we were on the Mongmit-Myitson Road, Lieutenant Walker was ordered to take charge of a party of 3 officers and 25 BOR's. He was told to head westward toward the Irrawaddy and make for India by the most direct route. The group were armed and had ammunition, also they had two days hard scale rations per man. The officers had both maps and compasses. An air supply dropping was arranged for them just west of the Irrawaddy, but the party failed to make the rendezvous. The Japanese were known to be fairly active in the area, but nothing has been heard of the group since.

It seems very likely that the group were attacked almost straight away after splitting from the other dispersal groups from No. 7 Column. It was also reported from other witness statements, that two of the men were murdered by Burmese villagers on the 10th April. This suggests to me that the vulnerable condition of the group had encouraged local villagers to attempt to capture the men in order to gain favour and financial reward from the Japanese in the area.

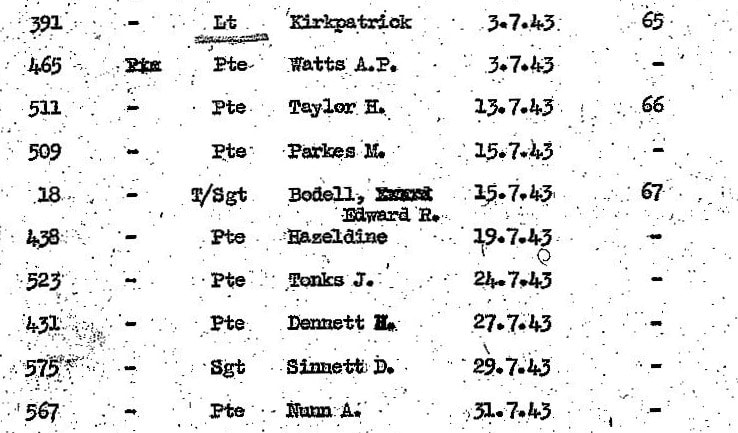

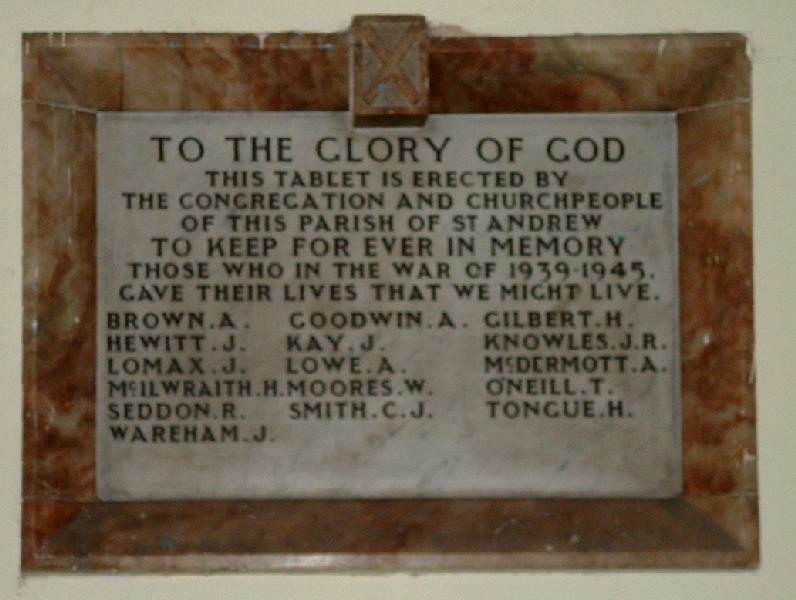

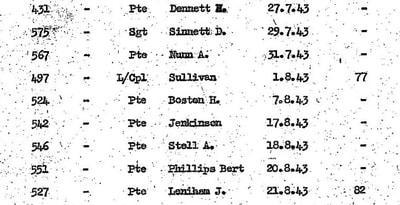

According to the testimony of Chindit, Pte. Norman Fowler, explained in the pages of his POW liberation questionnaire in July 1945, he and Joseph Kay, alongside another soldier, Pte. Herbert Boston attempted an escape from captivity in early May 1943, close to the Burmese village of Kunchaung. However, it seems most probable to me that Joseph had been captured much earlier than this and most likely close to the scene of Lt. Walker's dispersal party's demise at the Irrawaddy. In any case, although the three men's attempts to escape involved hand to hand fighting with their captors, it all ended in failure.

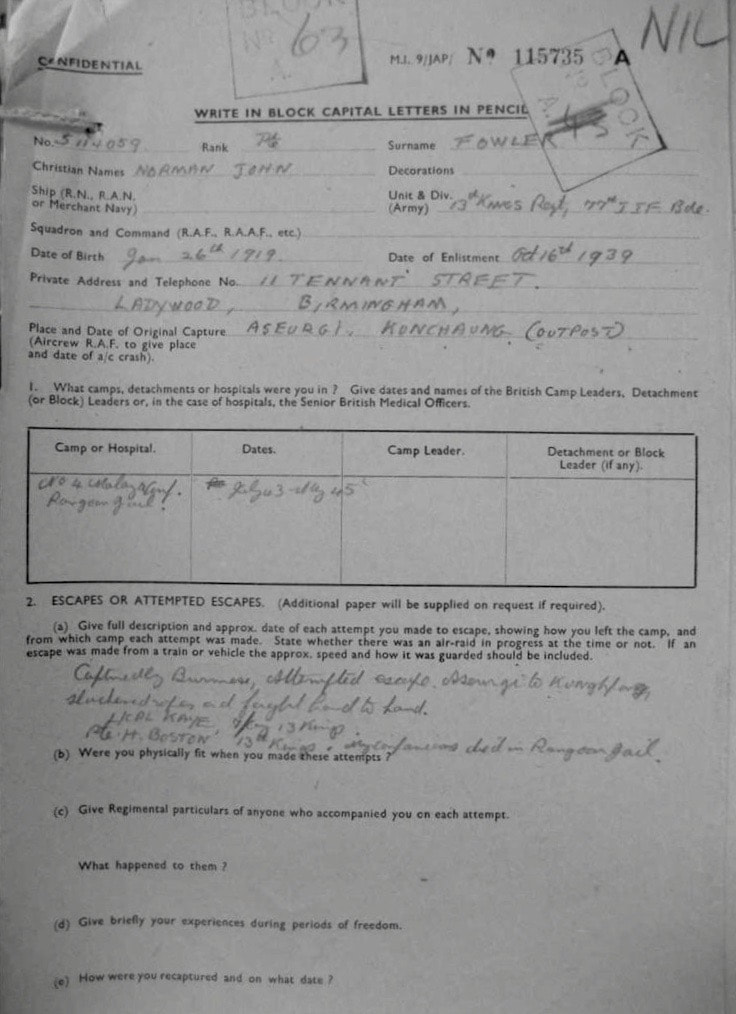

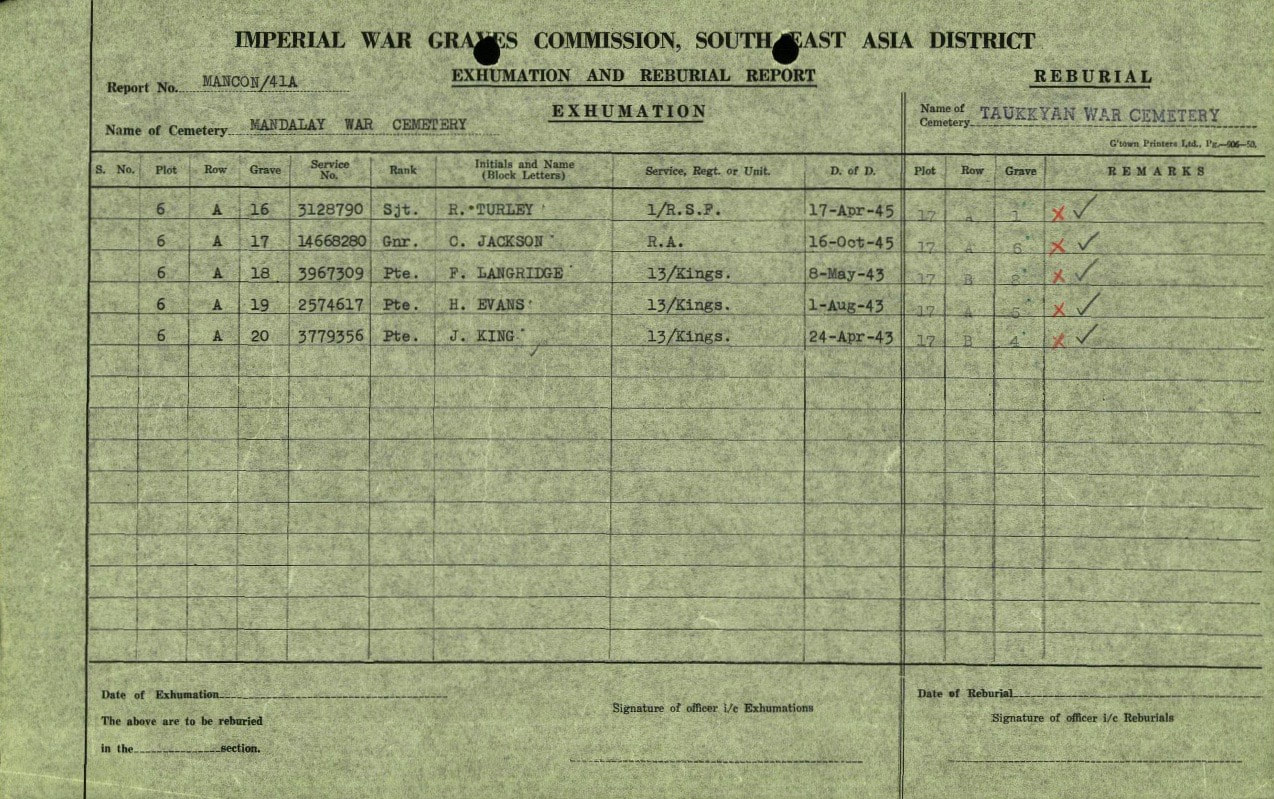

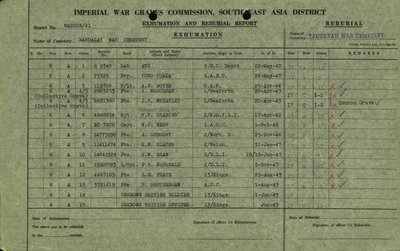

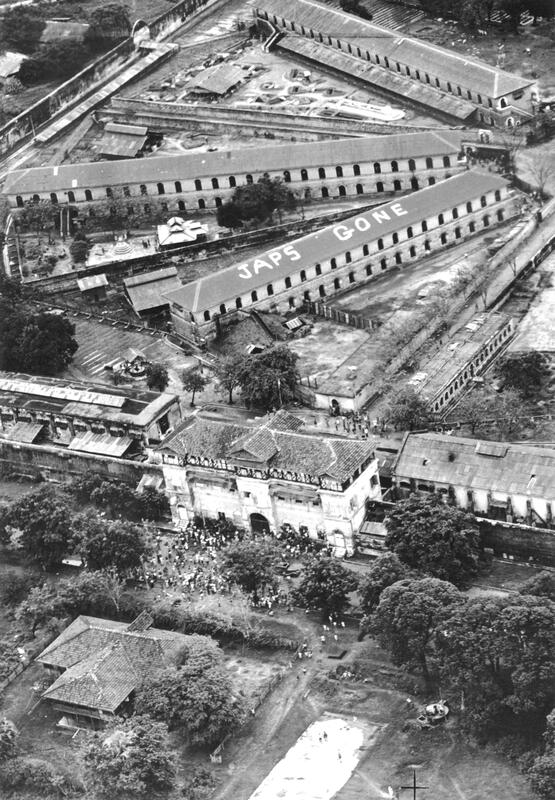

All captured Chindits were eventually taken down to Rangoon by train and placed into Block 6 of the city jail. Sadly, this is where Joseph Kay perished on the 2nd September 1943. According to paperwork discovered at the Imperial War Museum archives, he was given the POW number, 494 at Rangoon and was buried originally, in grave no. 51 at the English Cantonment Cemetery, located in the eastern sector of the city near the Royal Lakes. After the war was over, all burials from this cemetery were re-interred at the newly constructed Rangoon War Cemetery, with Joseph's remains moving over on the 14th June 1946.

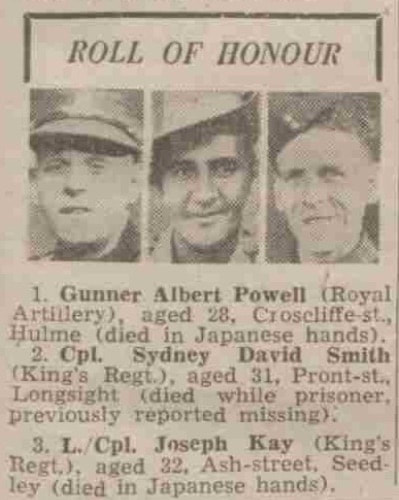

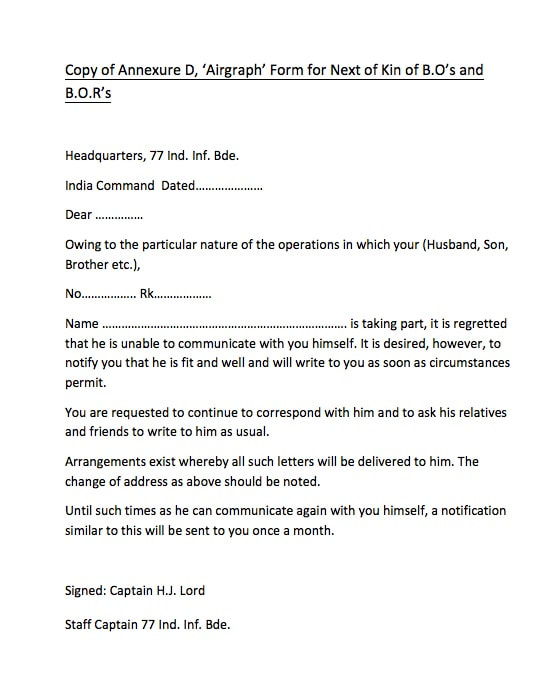

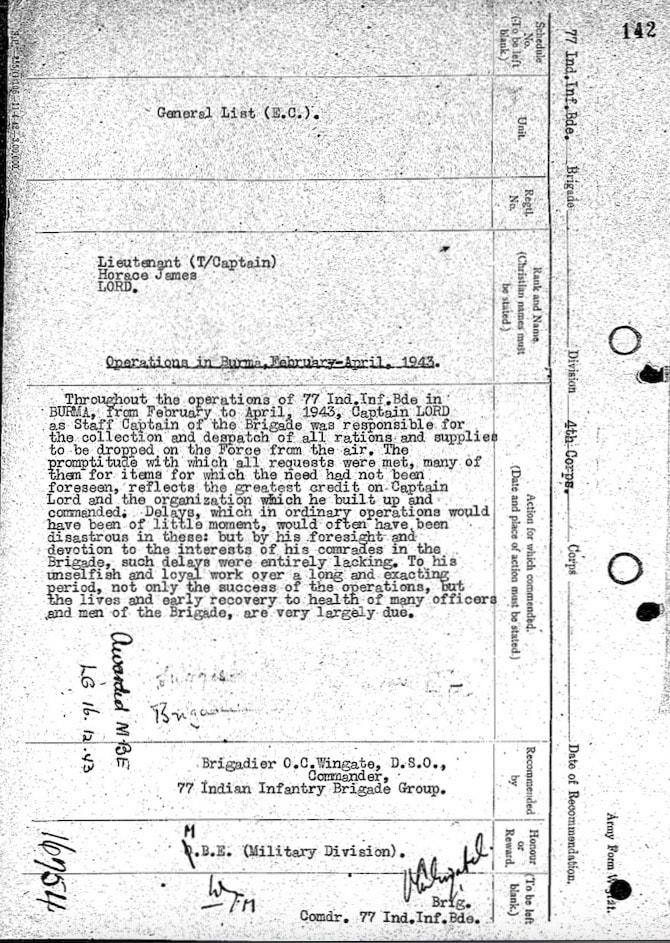

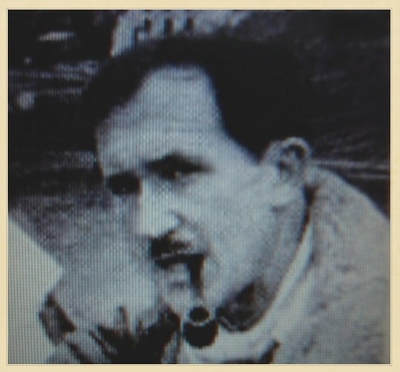

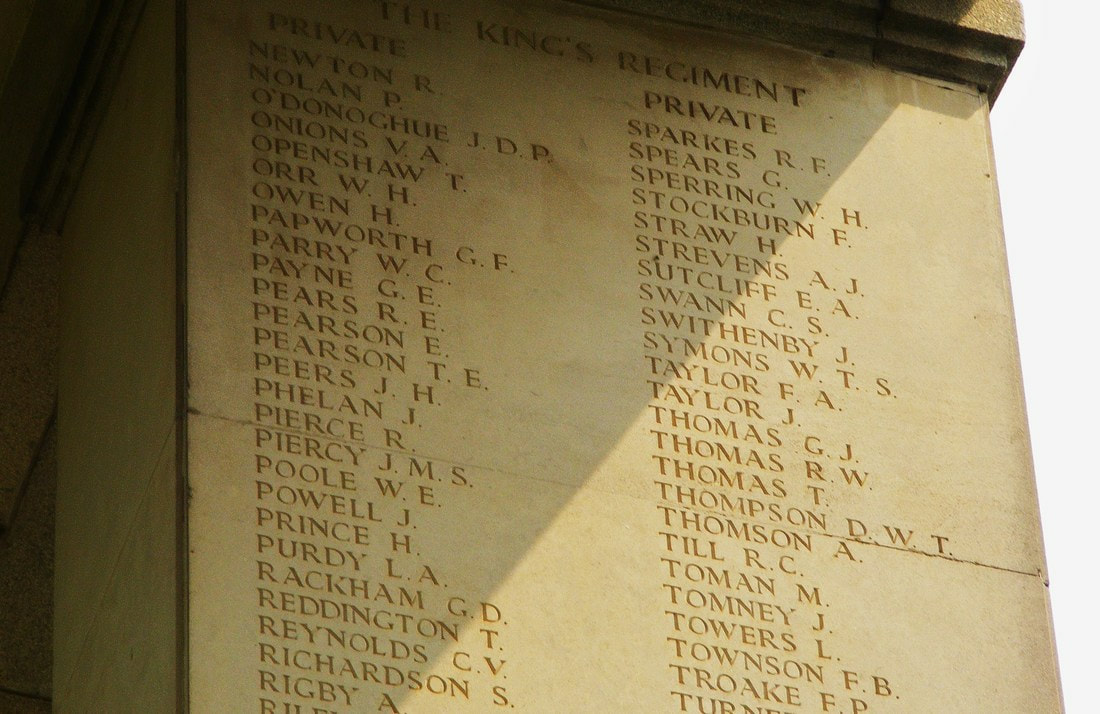

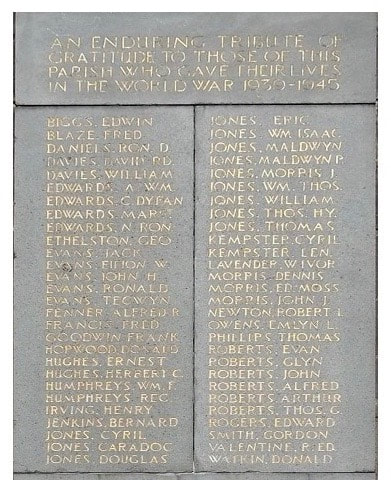

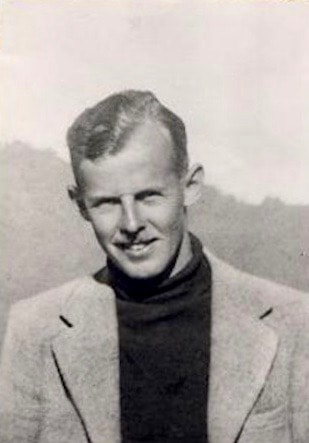

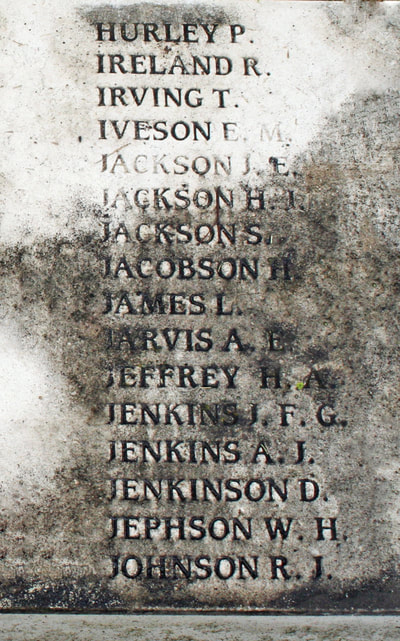

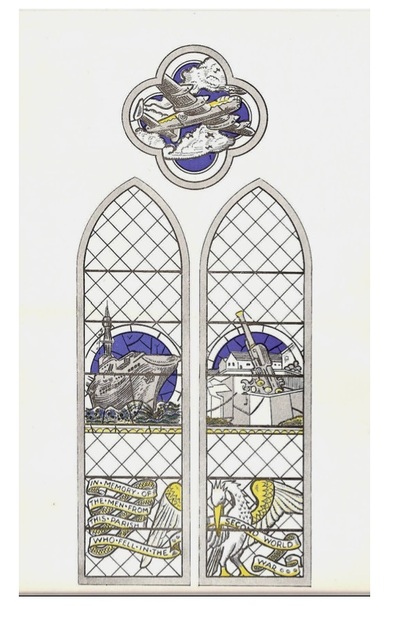

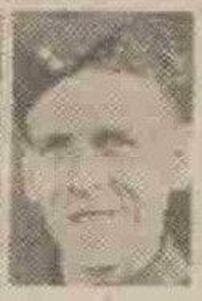

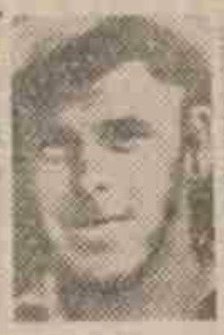

Although his family knew that Joseph was missing after the first Chindit expedition in 1943, they did not know that he was definitely a prisoner or war, or that he had died on the 2nd September that same year. They were given this sad news not long after Rangoon Jail was liberated in early May 1945 and the Manchester Evening News carried a short piece about Joseph's demise in Burma in their edition dated, 8th June 1945. This short two line notification also included the photograph of Joseph used at the beginning of this story. Later on, Joseph's name was included on the WW2 Memorial plaque at St. Andrew's Church, Ancoats, the same church in which he was baptised.

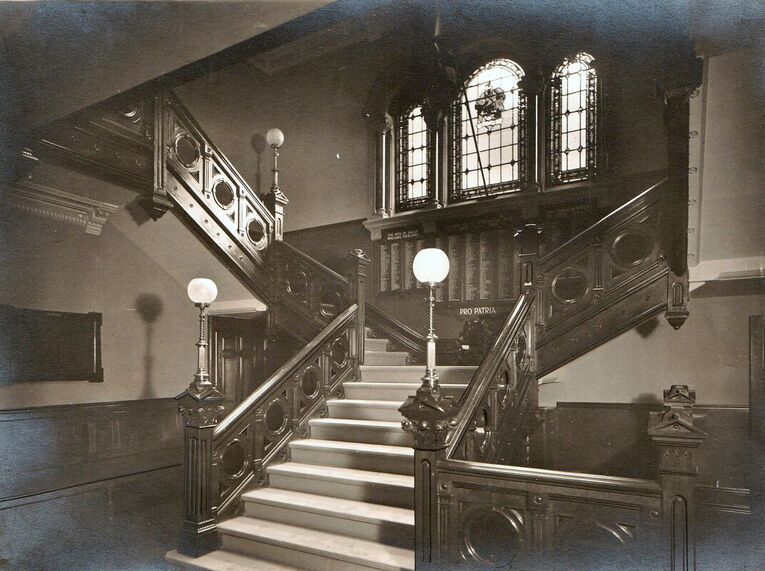

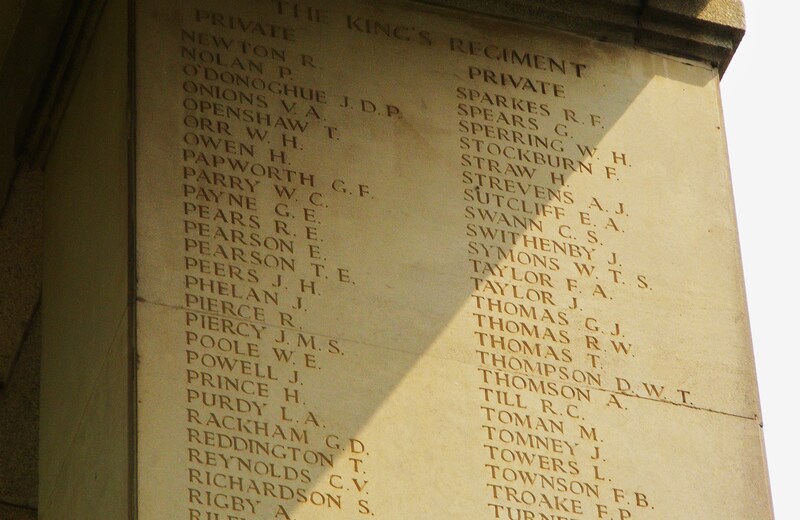

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including the memorial plaque at St. Andrews Church. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Rank: Lance Corporal

Service No: 3781435

Date of Death: 02/09/1943

Age: 31

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Rangoon War Cemetery Grave: 6.B.7.

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2260190/kay,-joseph/

Chindit Column: 7

Other details:

Joseph Kay was born on the 16th July 1912 and was the son of James Gilbert and Sarah Ann Kay from Ancoats, Manchester. James Kay worked as a printer and according to the 1939 Register, Joseph was still living with his parents at 5 Chaucer Street, Manchester and was working as a clothing salesman.

From Joseph's Army service number, 3781435, it seems highly likely that he was an original member of the 13th Battalion, the King's Regiment that voyaged overseas aboard the troopship, Oronsay on the 8th December 1941. After the battalion was given over to Brigadier Wingate in June 1942, Joseph was allocated to No. 7 Column and began his jungle warfare training at the Saugor camp in the Central Provinces of India. On Operation Longcloth, Joseph served as a section commander in one of the column's Rifle Platoons.

After dispersal was called around the 24/25th March 1943, Joseph was placed into the party commanded by Lt. Rex Walker. This was a group comprising soldiers who were already sick with disease or suffering from some sort of injury or wound. While the main body of No. 7 Column headed east in order to exit Burma via the Chinese Borders, Lt. Walker's dispersal party, due to the physical condition of its men, headed directly west in order to take the shortest possible route back to Allied held territory.

To read in more depth about Lt. Rex Walker's group, please click on the following link: Rex Walker's Dispersal Group 4

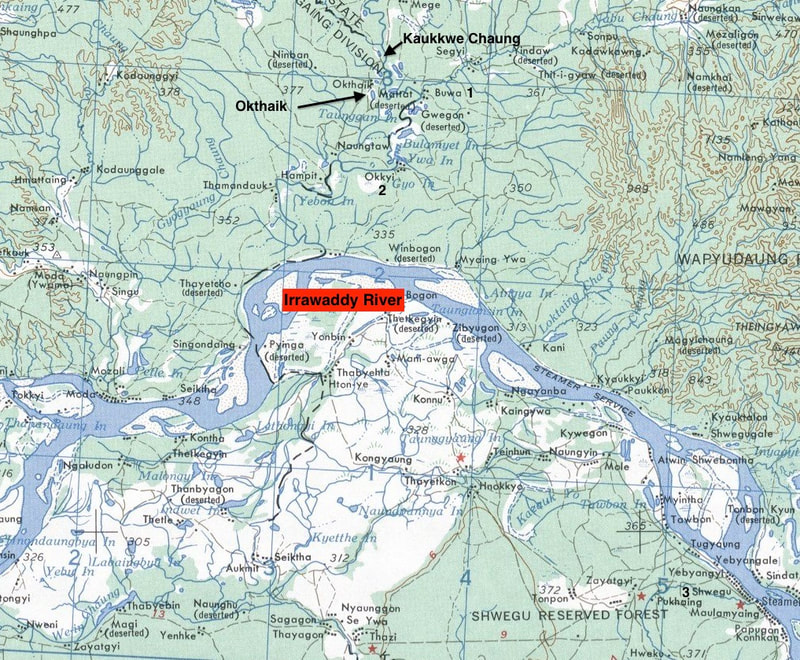

Joseph Kay was officially reported as missing in action on the 10th April 1943, while his dispersal group were preparing to make a crossing of the Irrawaddy River. A witness statement, given by No. 7 Column Adjutant, Captain Leslie Cottrell after the operation throws some light on the situation:

On April 10th we were on the Mongmit-Myitson Road, Lieutenant Walker was ordered to take charge of a party of 3 officers and 25 BOR's. He was told to head westward toward the Irrawaddy and make for India by the most direct route. The group were armed and had ammunition, also they had two days hard scale rations per man. The officers had both maps and compasses. An air supply dropping was arranged for them just west of the Irrawaddy, but the party failed to make the rendezvous. The Japanese were known to be fairly active in the area, but nothing has been heard of the group since.

It seems very likely that the group were attacked almost straight away after splitting from the other dispersal groups from No. 7 Column. It was also reported from other witness statements, that two of the men were murdered by Burmese villagers on the 10th April. This suggests to me that the vulnerable condition of the group had encouraged local villagers to attempt to capture the men in order to gain favour and financial reward from the Japanese in the area.

According to the testimony of Chindit, Pte. Norman Fowler, explained in the pages of his POW liberation questionnaire in July 1945, he and Joseph Kay, alongside another soldier, Pte. Herbert Boston attempted an escape from captivity in early May 1943, close to the Burmese village of Kunchaung. However, it seems most probable to me that Joseph had been captured much earlier than this and most likely close to the scene of Lt. Walker's dispersal party's demise at the Irrawaddy. In any case, although the three men's attempts to escape involved hand to hand fighting with their captors, it all ended in failure.

All captured Chindits were eventually taken down to Rangoon by train and placed into Block 6 of the city jail. Sadly, this is where Joseph Kay perished on the 2nd September 1943. According to paperwork discovered at the Imperial War Museum archives, he was given the POW number, 494 at Rangoon and was buried originally, in grave no. 51 at the English Cantonment Cemetery, located in the eastern sector of the city near the Royal Lakes. After the war was over, all burials from this cemetery were re-interred at the newly constructed Rangoon War Cemetery, with Joseph's remains moving over on the 14th June 1946.

Although his family knew that Joseph was missing after the first Chindit expedition in 1943, they did not know that he was definitely a prisoner or war, or that he had died on the 2nd September that same year. They were given this sad news not long after Rangoon Jail was liberated in early May 1945 and the Manchester Evening News carried a short piece about Joseph's demise in Burma in their edition dated, 8th June 1945. This short two line notification also included the photograph of Joseph used at the beginning of this story. Later on, Joseph's name was included on the WW2 Memorial plaque at St. Andrew's Church, Ancoats, the same church in which he was baptised.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including the memorial plaque at St. Andrews Church. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Cap badge of the King's Regiment.

Cap badge of the King's Regiment.

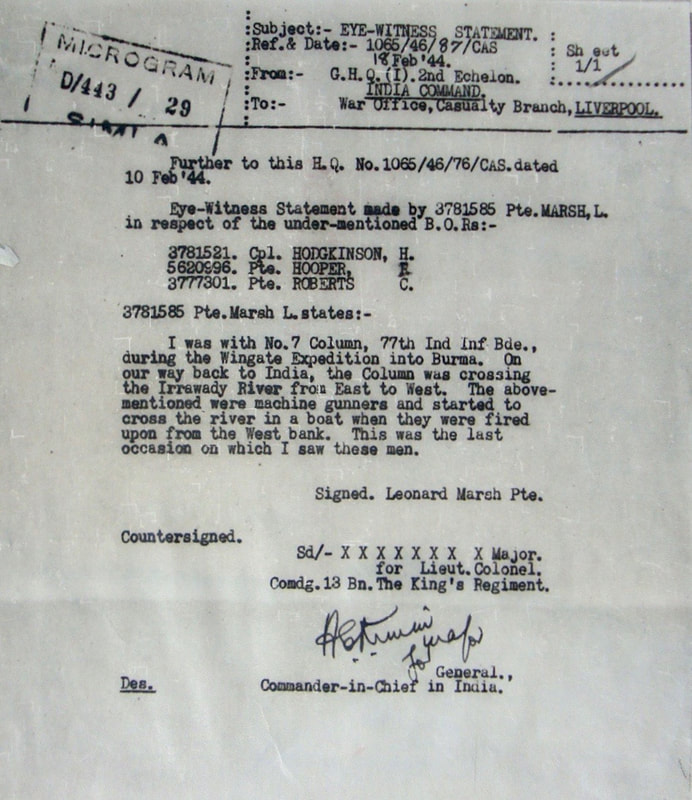

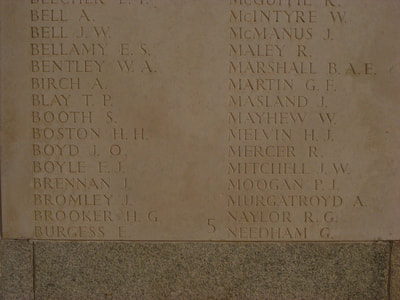

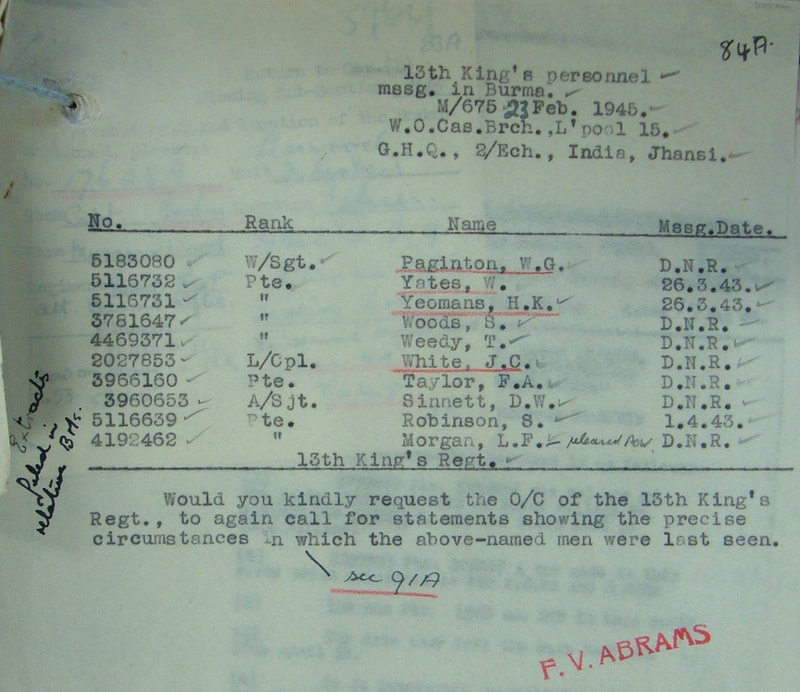

KELLY, J.

Rank: Pte.

Service No: 3779327

Age: Not known

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Chindit Column: 5

Other details:

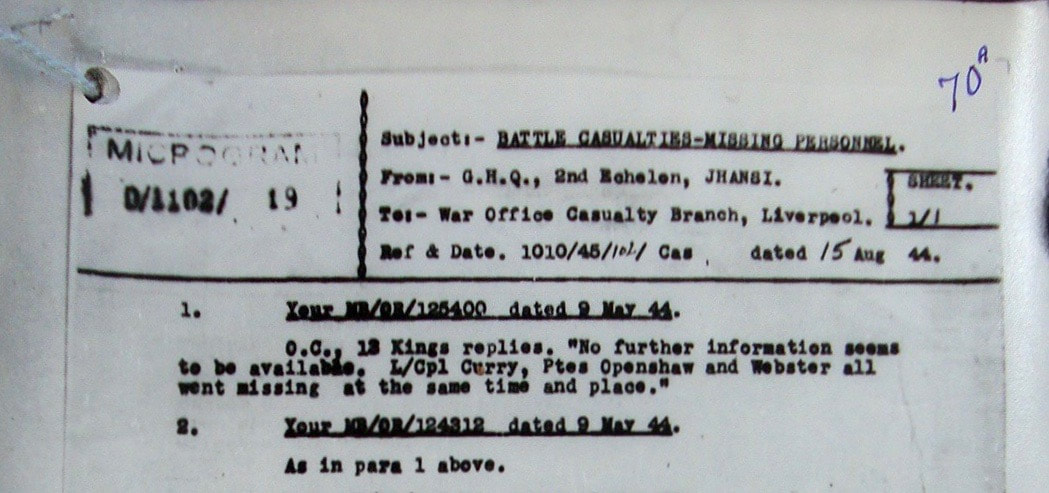

Pte. J. Kelly was an original member of the 13th Battalion, the King's Regiment, that travelled to India aboard the troopship Oronsay on the 8th December 1941. The only information we really have about this soldier, is that he gave a witness statement after his return from Operation Longcloth in regards to Pte. William Dunn and Pte. David Clarke and there last known whereabouts on the first Wingate expedition.

The statement reads as follows:

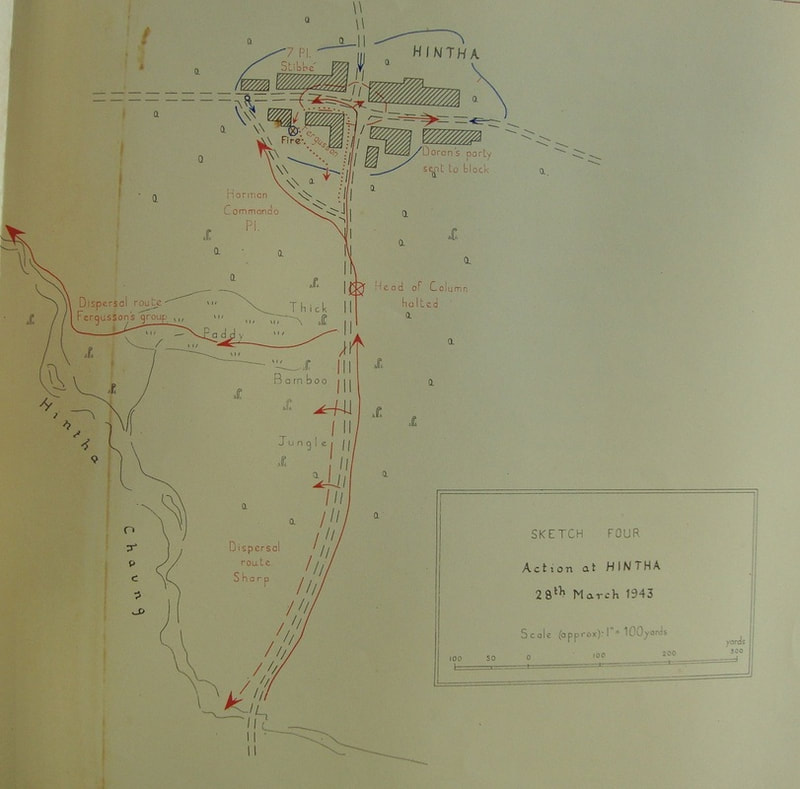

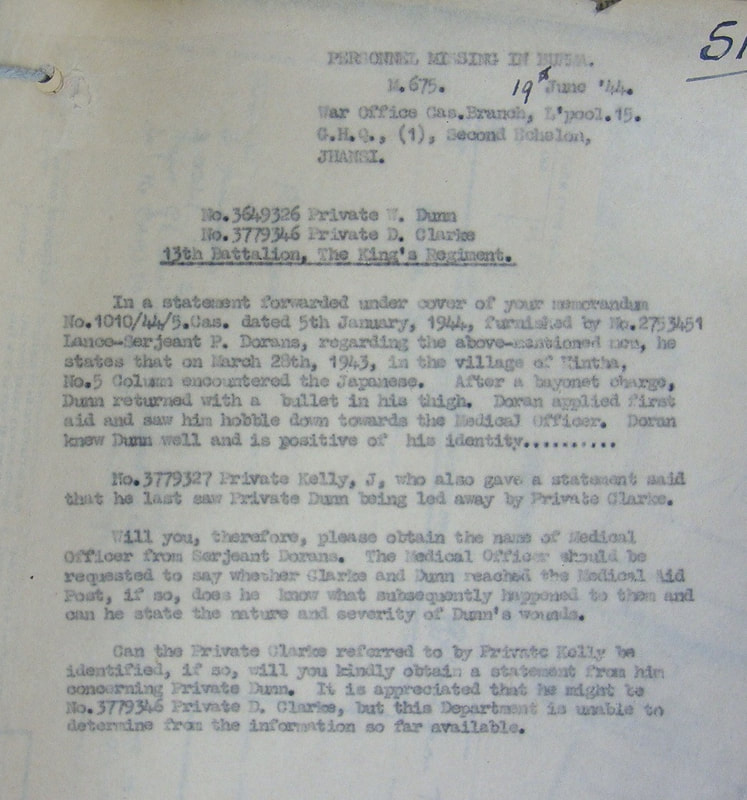

In a statement forwarded on 5th January 1944 furnished by Lance-Sergeant P. Dorans and regarding the above mentioned men, he states that on the 28th March 1943, in the village of Hintha No. 5 Column encountered the Japanese. After a bayonet charge, Pte. Dunn returned with a bullet wound to his thigh. Dorans applied first-aid and then saw him hobble down to the Medical Officer. Dorans knew Dunn well and is positive of his identity that day.

No. 3779327 Pte. J. Kelly who also gave a statement, said that he last saw Dunn being led away from the same village by Pte. Clarke. Can we obtain the name of the Medical Officer from Sergeant Dorans and whether he can confirm that Dunn and Clarke did indeed reach the Medical Aid Post, and if so, does he know what subsequently happened to the two men. Also, can the Pte. Clarke referred to by Pte. Kelly be identified and a statement obtained?

Sadly, neither the Medical Officer that day, Captain William Service Aird, or Ptes. D. Clarke and W. Dunn survived their time in Burma. William Aird was captured by the Japanese in early April 1943 and perished suffering from both malaria and dysentery as the Chindit POWs were being transported by train to Rangoon on the 10th May.

To read more about William Aird, please click on the following link: Rex Walker's Dispersal Group 4

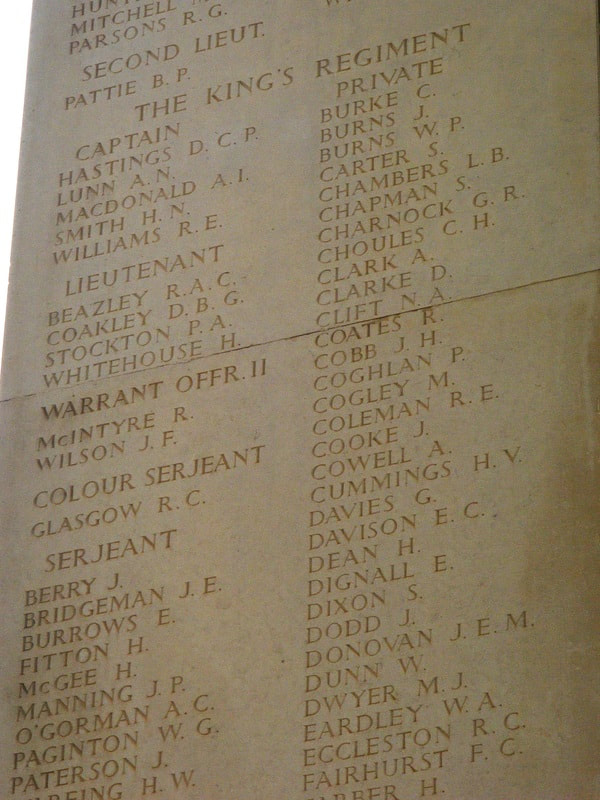

Pte. 3649326 William Dunn was wounded during No. 5 Column's engagement with the Japanese at Hintha. Sadly, he died from his wounds that very same day (28th March 1943). He had volunteered to be Lt. Stibbe's batman during the training period in Malthone, India and Lt. Stibbe remembered him in his book, Return via Rangoon:

“I decided to try Dunn as my batman, he had been a leather worker from Warrington. He was dark and well built, a good swimmer and, although had always lived in a town, he had liked country pursuits. He looked after me admirably and kept me amused with his witty and sometimes caustic comments on life. Often he gave me very sound advice when asked, and occasionally, very respectfully, when not asked."

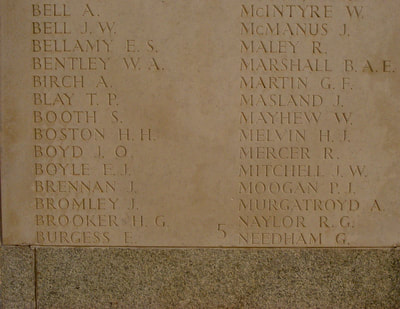

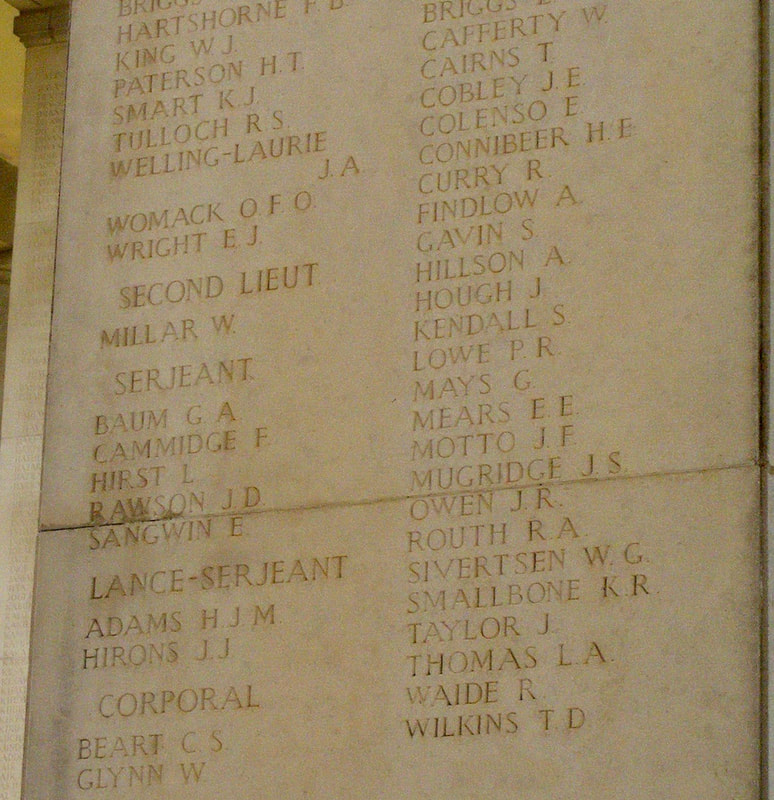

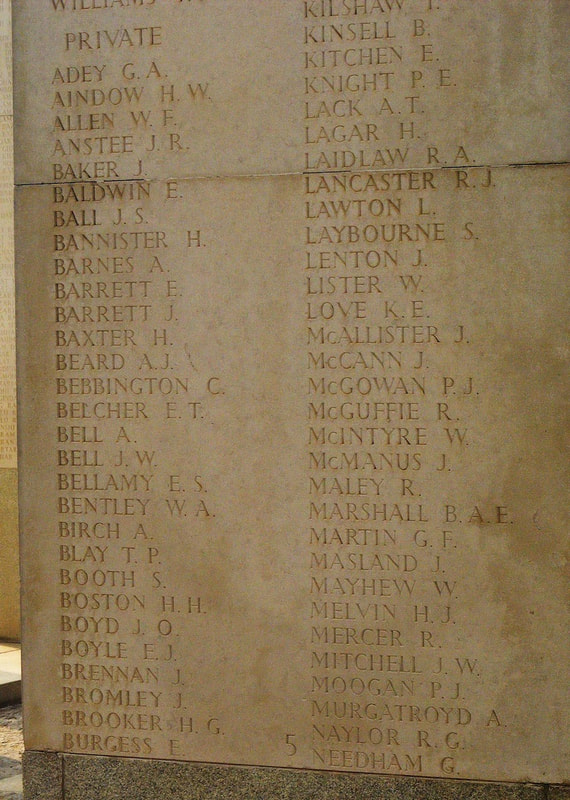

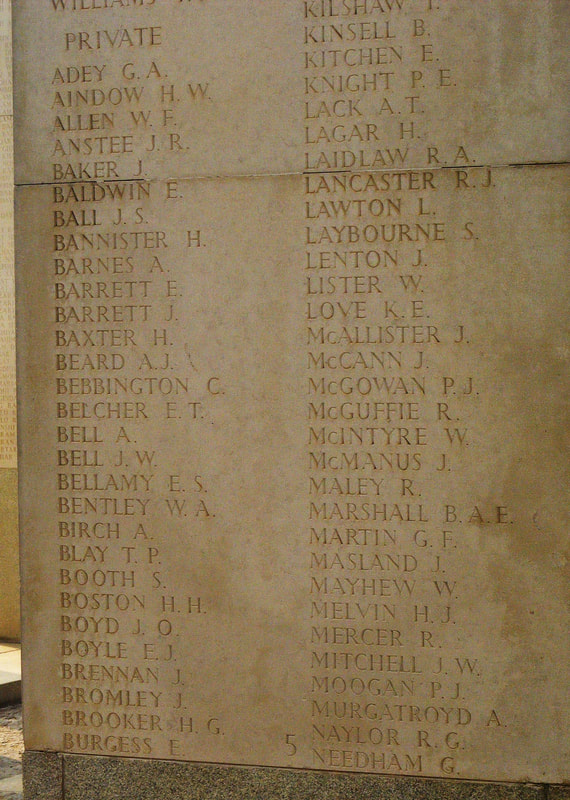

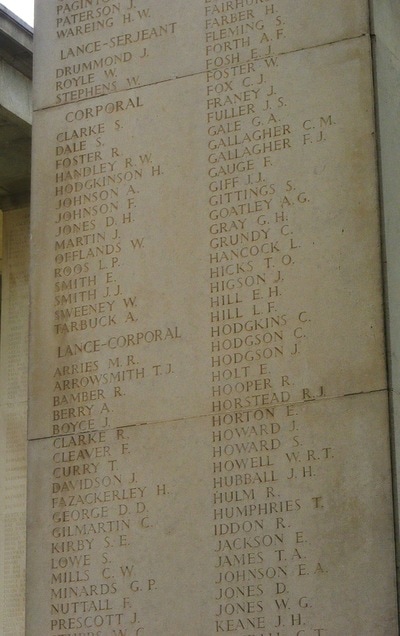

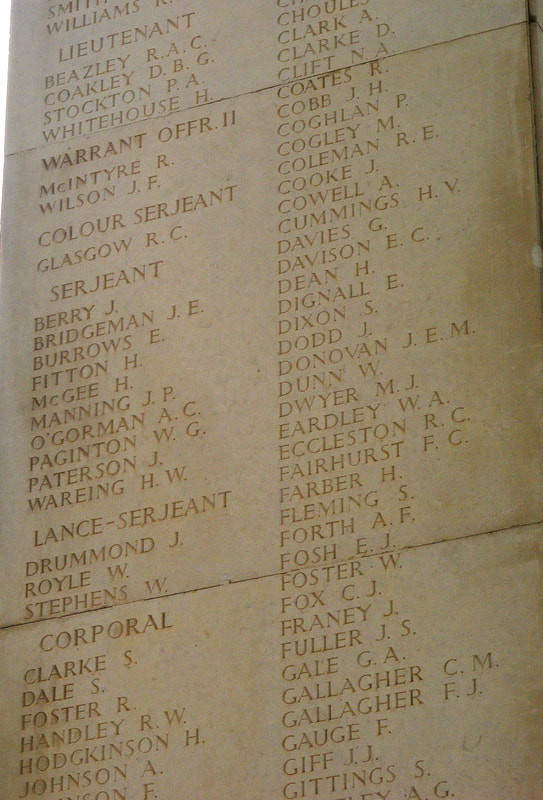

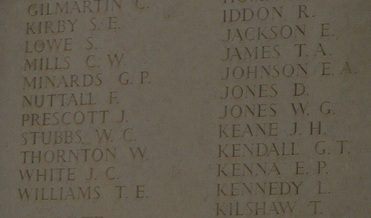

William's body was never recovered after the war and for this reason he is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery. To read his CWGC details, please click on the following link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/1291967/dunn,-william/

Pte. 3779346 David Clarke managed to disperse with his column after the battle of Hintha, but became separated from his unit during a secondary ambush by the enemy the next day. He and around 100 other men from 5 Column were fortunate to bump into No. 7 Column a few days later close to the Shweli River, where Major Gilkes took all the new arrivals under his wing and allocated them to his own pre-arranged dispersal groups. The party into which David Clarke was placed marched north east into the Kachin Hills, but sadly, on the 26th April David, by now utterly exhausted, fell out of the line of march as the group were preparing to cross a small river. He was never seen or heard of again.

Much like William Dunn, David's body was never found after the war and so he is also remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery. This memorial was constructed to honour the 26,000 Commonwealth Service personnel who perished during the Burma Campaign, but who have no known grave.

To read David's CWGC details, please click on the following link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2507559/clarke,-david/

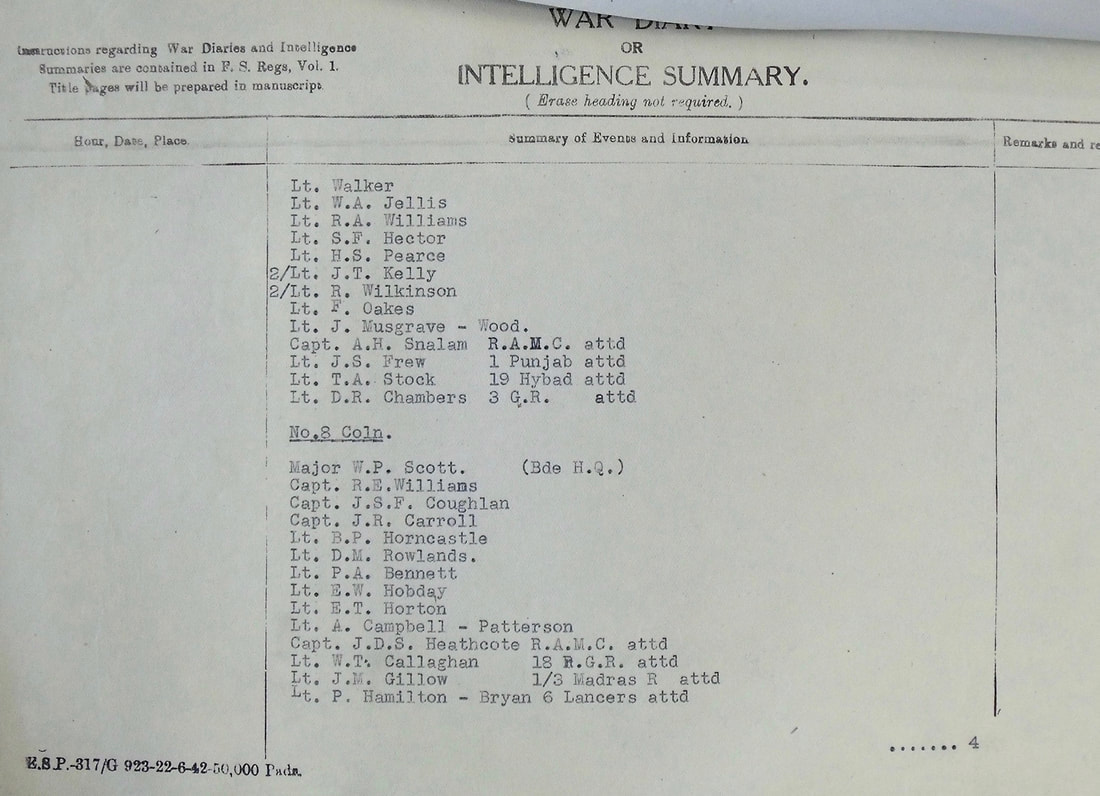

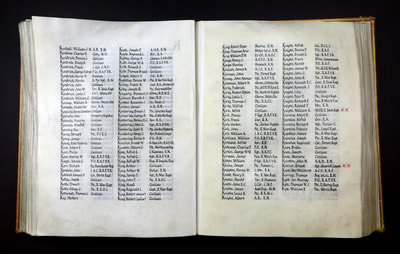

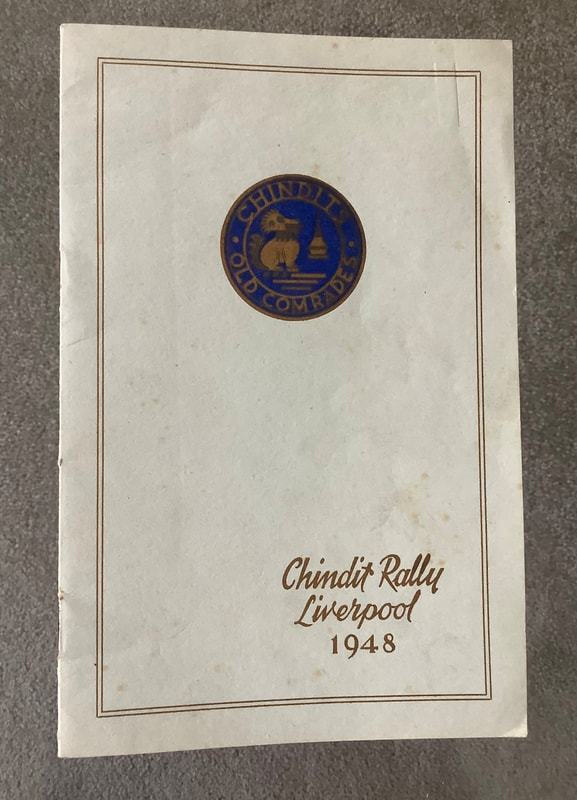

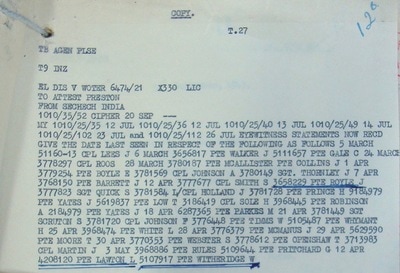

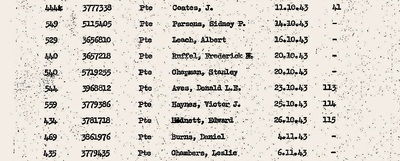

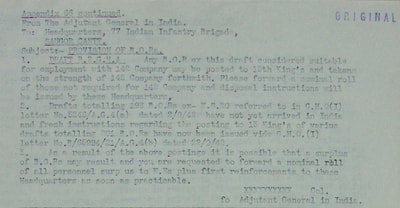

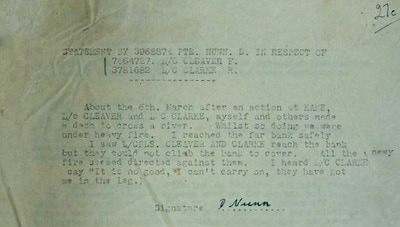

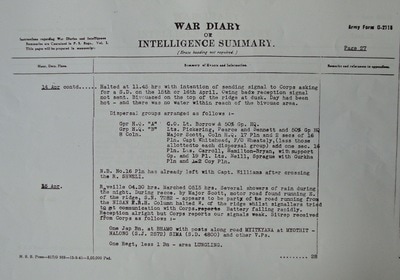

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this short narrative, including the combined witness statement covering Pte. J. Kelly's information. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Rank: Pte.

Service No: 3779327

Age: Not known

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Chindit Column: 5

Other details:

Pte. J. Kelly was an original member of the 13th Battalion, the King's Regiment, that travelled to India aboard the troopship Oronsay on the 8th December 1941. The only information we really have about this soldier, is that he gave a witness statement after his return from Operation Longcloth in regards to Pte. William Dunn and Pte. David Clarke and there last known whereabouts on the first Wingate expedition.

The statement reads as follows:

In a statement forwarded on 5th January 1944 furnished by Lance-Sergeant P. Dorans and regarding the above mentioned men, he states that on the 28th March 1943, in the village of Hintha No. 5 Column encountered the Japanese. After a bayonet charge, Pte. Dunn returned with a bullet wound to his thigh. Dorans applied first-aid and then saw him hobble down to the Medical Officer. Dorans knew Dunn well and is positive of his identity that day.

No. 3779327 Pte. J. Kelly who also gave a statement, said that he last saw Dunn being led away from the same village by Pte. Clarke. Can we obtain the name of the Medical Officer from Sergeant Dorans and whether he can confirm that Dunn and Clarke did indeed reach the Medical Aid Post, and if so, does he know what subsequently happened to the two men. Also, can the Pte. Clarke referred to by Pte. Kelly be identified and a statement obtained?

Sadly, neither the Medical Officer that day, Captain William Service Aird, or Ptes. D. Clarke and W. Dunn survived their time in Burma. William Aird was captured by the Japanese in early April 1943 and perished suffering from both malaria and dysentery as the Chindit POWs were being transported by train to Rangoon on the 10th May.

To read more about William Aird, please click on the following link: Rex Walker's Dispersal Group 4

Pte. 3649326 William Dunn was wounded during No. 5 Column's engagement with the Japanese at Hintha. Sadly, he died from his wounds that very same day (28th March 1943). He had volunteered to be Lt. Stibbe's batman during the training period in Malthone, India and Lt. Stibbe remembered him in his book, Return via Rangoon:

“I decided to try Dunn as my batman, he had been a leather worker from Warrington. He was dark and well built, a good swimmer and, although had always lived in a town, he had liked country pursuits. He looked after me admirably and kept me amused with his witty and sometimes caustic comments on life. Often he gave me very sound advice when asked, and occasionally, very respectfully, when not asked."

William's body was never recovered after the war and for this reason he is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery. To read his CWGC details, please click on the following link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/1291967/dunn,-william/

Pte. 3779346 David Clarke managed to disperse with his column after the battle of Hintha, but became separated from his unit during a secondary ambush by the enemy the next day. He and around 100 other men from 5 Column were fortunate to bump into No. 7 Column a few days later close to the Shweli River, where Major Gilkes took all the new arrivals under his wing and allocated them to his own pre-arranged dispersal groups. The party into which David Clarke was placed marched north east into the Kachin Hills, but sadly, on the 26th April David, by now utterly exhausted, fell out of the line of march as the group were preparing to cross a small river. He was never seen or heard of again.

Much like William Dunn, David's body was never found after the war and so he is also remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery. This memorial was constructed to honour the 26,000 Commonwealth Service personnel who perished during the Burma Campaign, but who have no known grave.

To read David's CWGC details, please click on the following link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2507559/clarke,-david/

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this short narrative, including the combined witness statement covering Pte. J. Kelly's information. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

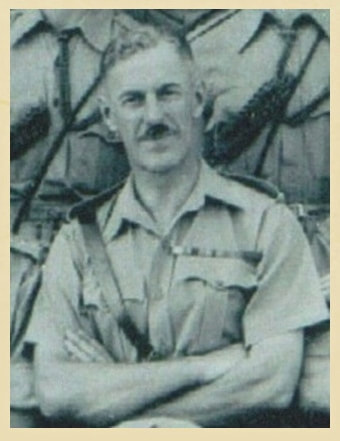

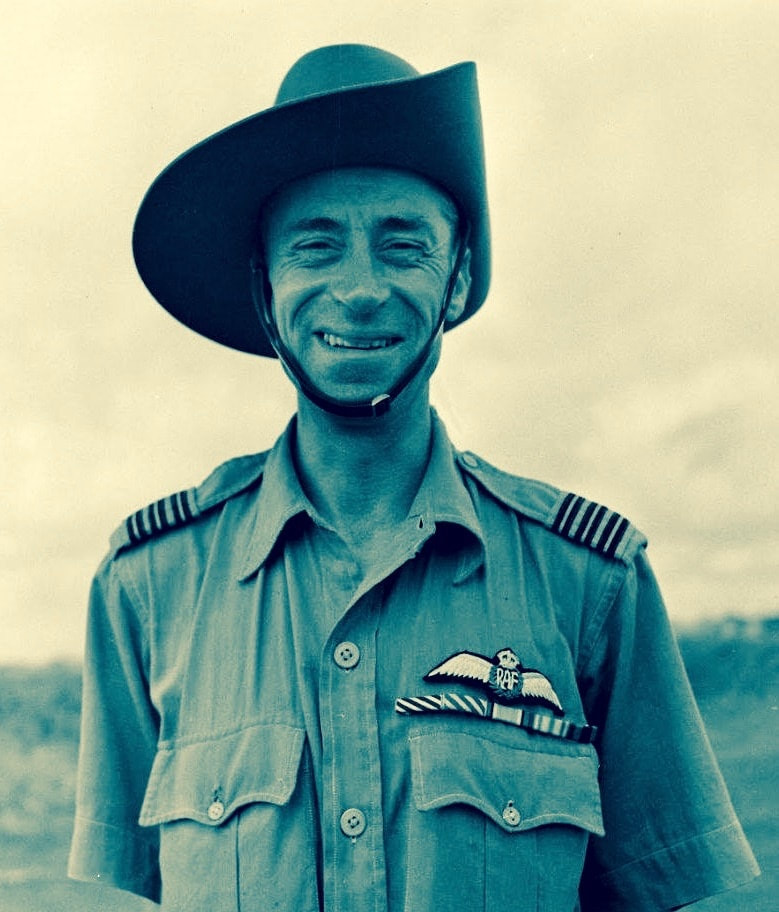

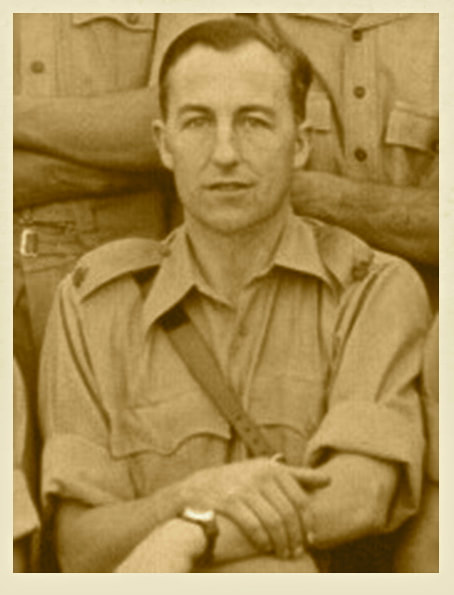

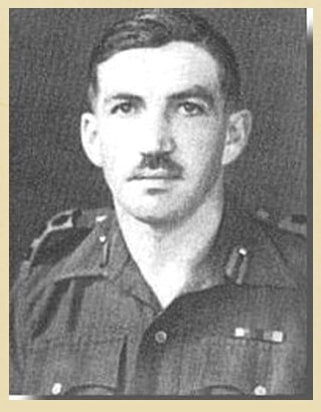

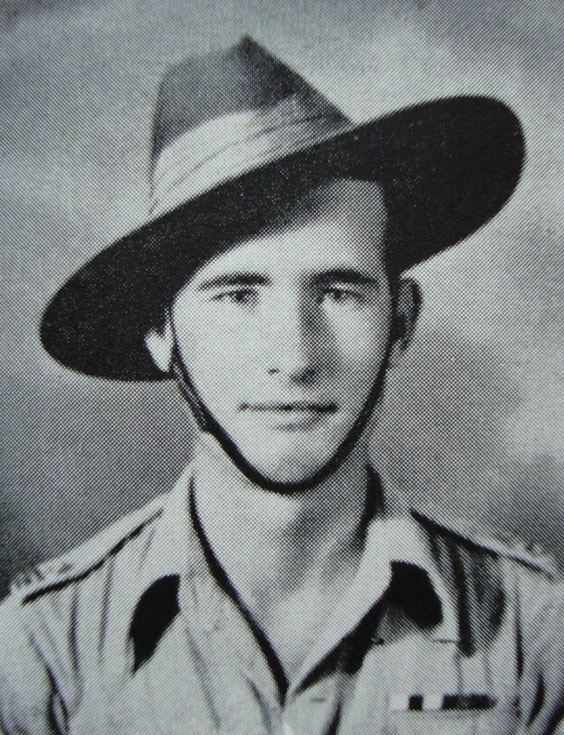

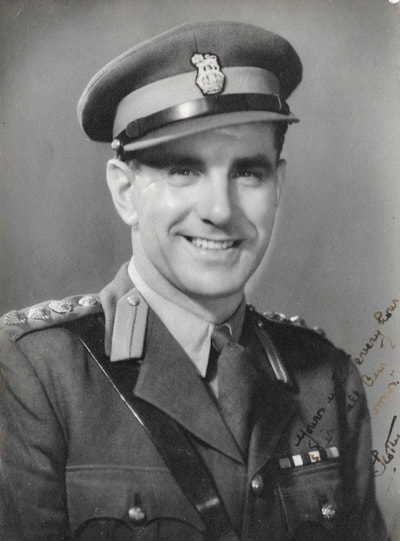

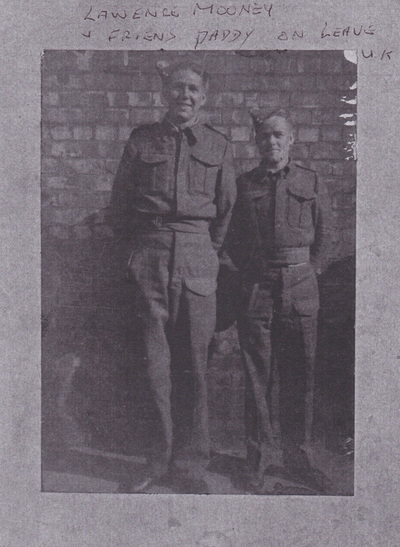

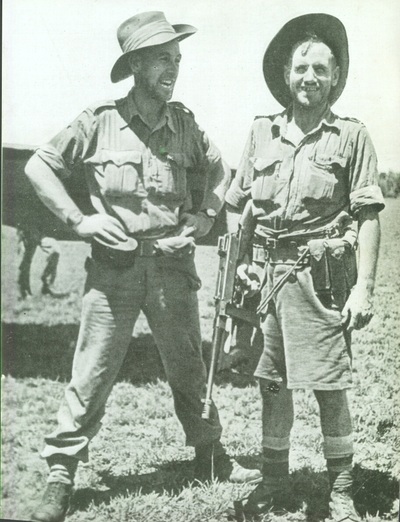

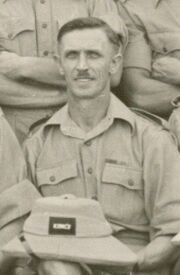

RSM Kelly (India 1942).

RSM Kelly (India 1942).

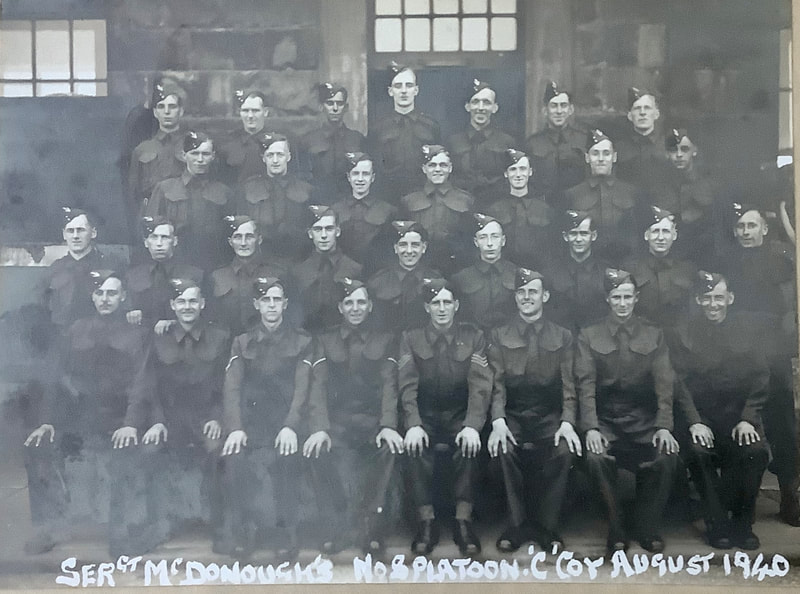

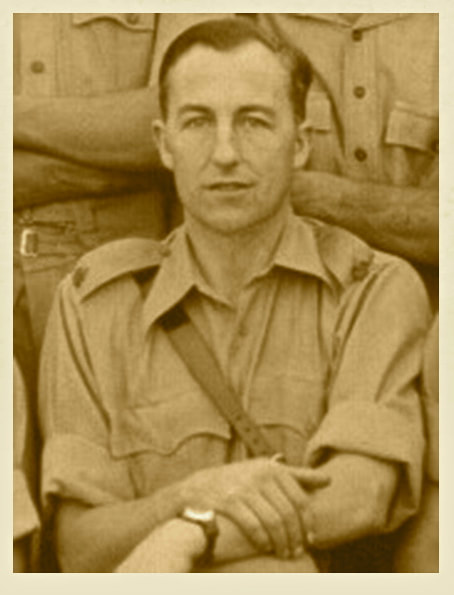

KELLY, RSM

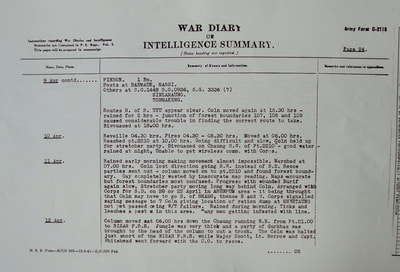

RSM Kelly was the 13th King's original Regimental Sergeant Major and had been with the battalion since the middle of 1940, when the unit had been based at the Jordan Hill Barracks in Glasgow. He was a popular man with officers and Other Ranks alike, having previously been the senior Warrant Officer at the Liverpool College Officers Training Corps. Lt. Leslie Cottrell remembered Kelly, as a : kindly man who would watch over you when giving out orders or instructing new officers in regards duties such as mounting the guard.

Kelly continued in his role after the 13th King's had travelled overseas to India and led the battalion during its time in Secunderabad, where it performed garrison and internal security duties. Unfortunately, after the battalion had been given over to Brigadier Wingate in June 1942, Kelly, along with many other men from the 13th King's, struggled to cope with the arduous nature of jungle warfare training.

Once again, Lt. Cottrell remembered:

After several weeks in the camp at Saugor our sick parades began to feature over 400 men, which was over half the battalion. The men were suffering mostly from mild dysentery and jungle sores which had turned septic and require immediate treatment. RSM Kelly had contracted impetigo which covered his face, but which the new drug MB693 cleared up completely in just five days.

As October turned to November in 1942, the decision was made to bring in reinforcements to replace the original members of the battalion, who were clearly not suited for a jungle warfare role, or were considered simply too old to take part in the forthcoming operations in Burma. In the end it was decided that both RSM Kelly and the battalion's commanding officer, Lt-Colonel W.M. Robinson fell into this category and it was with regret that Wingate informed both men that they would be taking no further part in proceedings. RSM Kelly was replaced by William James Livingstone, who had been with the 13th King's since July 1940.

Leslie Cottrell recalled:

In January 1943 the 13th King's and the other units of 77 Brigade moved by train to Dimapur in Assam; but not all the officers and men who had made up the 13th King's at Patharia still constituted that regiment at Dimapur. Several had been 'weeded out' as it was perhaps unkindly put and reinforcements brought in. Some officers and Warrant Officers, including the Commanding Officer and RSM Kelly were considered too old to take part in the forthcoming campaign and some others were of too low a medical category.

It is not known for sure what role RSM Kelly performed after leaving the 13th King's in late 1942? It must be assumed that a man of his experience and knowledge would have been given an important position, perhaps in the matters of regimental training or internal security for which he would have been an ideal candidate.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this short story, comprising photographs of the officers mentioned in the above narrative. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

RSM Kelly was the 13th King's original Regimental Sergeant Major and had been with the battalion since the middle of 1940, when the unit had been based at the Jordan Hill Barracks in Glasgow. He was a popular man with officers and Other Ranks alike, having previously been the senior Warrant Officer at the Liverpool College Officers Training Corps. Lt. Leslie Cottrell remembered Kelly, as a : kindly man who would watch over you when giving out orders or instructing new officers in regards duties such as mounting the guard.

Kelly continued in his role after the 13th King's had travelled overseas to India and led the battalion during its time in Secunderabad, where it performed garrison and internal security duties. Unfortunately, after the battalion had been given over to Brigadier Wingate in June 1942, Kelly, along with many other men from the 13th King's, struggled to cope with the arduous nature of jungle warfare training.

Once again, Lt. Cottrell remembered:

After several weeks in the camp at Saugor our sick parades began to feature over 400 men, which was over half the battalion. The men were suffering mostly from mild dysentery and jungle sores which had turned septic and require immediate treatment. RSM Kelly had contracted impetigo which covered his face, but which the new drug MB693 cleared up completely in just five days.

As October turned to November in 1942, the decision was made to bring in reinforcements to replace the original members of the battalion, who were clearly not suited for a jungle warfare role, or were considered simply too old to take part in the forthcoming operations in Burma. In the end it was decided that both RSM Kelly and the battalion's commanding officer, Lt-Colonel W.M. Robinson fell into this category and it was with regret that Wingate informed both men that they would be taking no further part in proceedings. RSM Kelly was replaced by William James Livingstone, who had been with the 13th King's since July 1940.

Leslie Cottrell recalled:

In January 1943 the 13th King's and the other units of 77 Brigade moved by train to Dimapur in Assam; but not all the officers and men who had made up the 13th King's at Patharia still constituted that regiment at Dimapur. Several had been 'weeded out' as it was perhaps unkindly put and reinforcements brought in. Some officers and Warrant Officers, including the Commanding Officer and RSM Kelly were considered too old to take part in the forthcoming campaign and some others were of too low a medical category.

It is not known for sure what role RSM Kelly performed after leaving the 13th King's in late 1942? It must be assumed that a man of his experience and knowledge would have been given an important position, perhaps in the matters of regimental training or internal security for which he would have been an ideal candidate.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this short story, comprising photographs of the officers mentioned in the above narrative. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

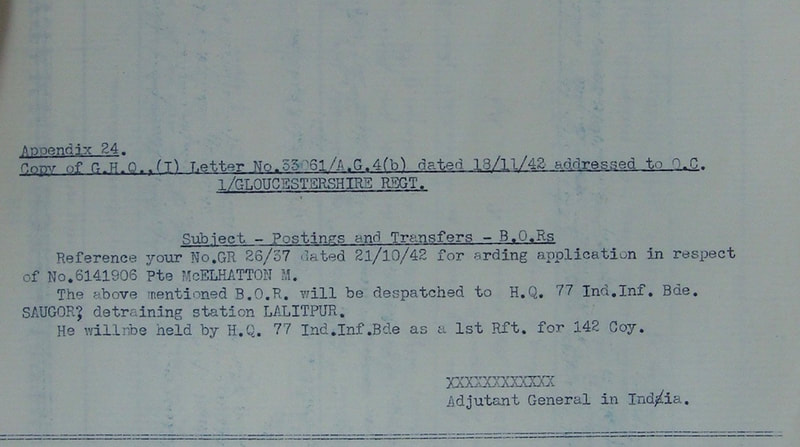

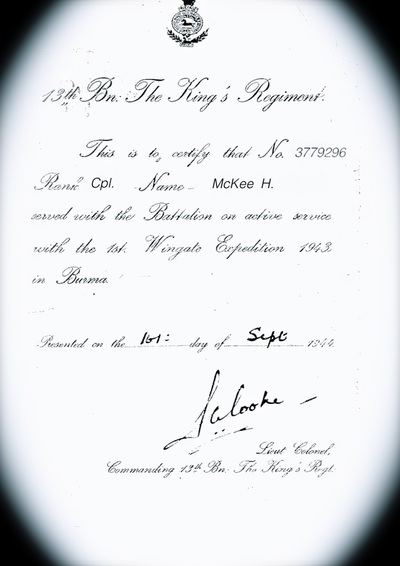

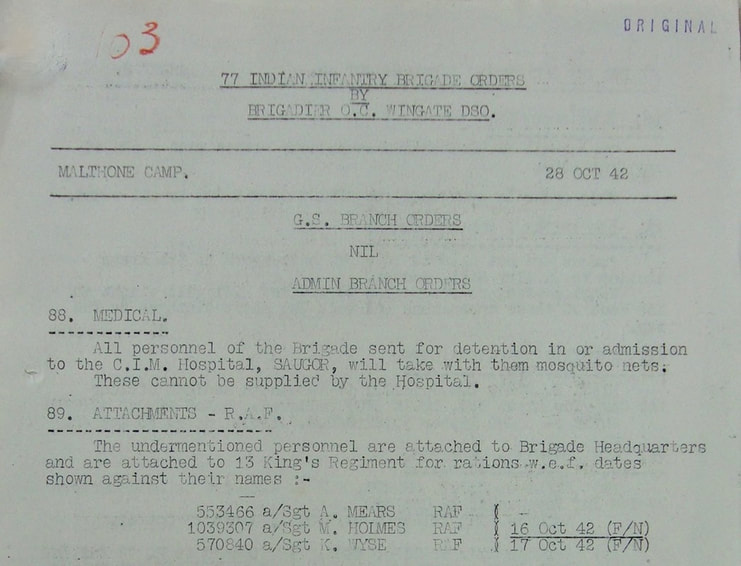

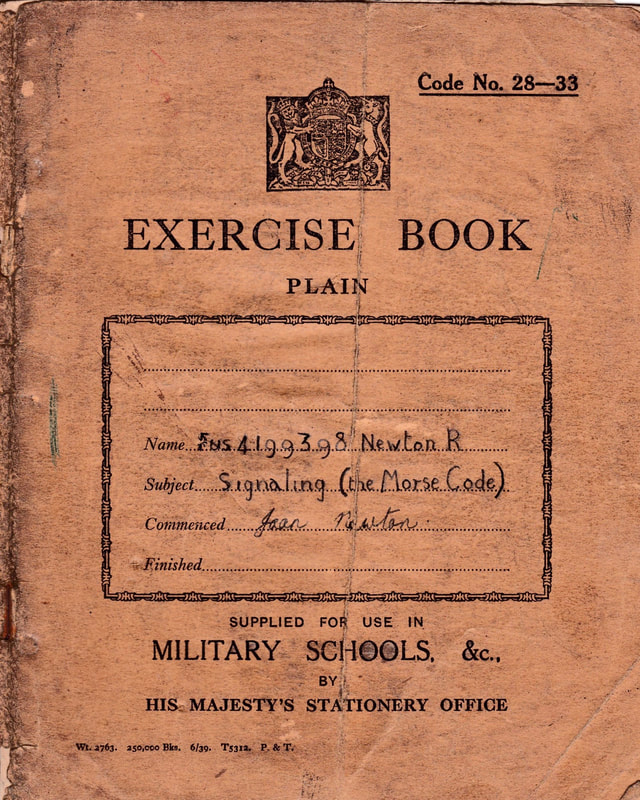

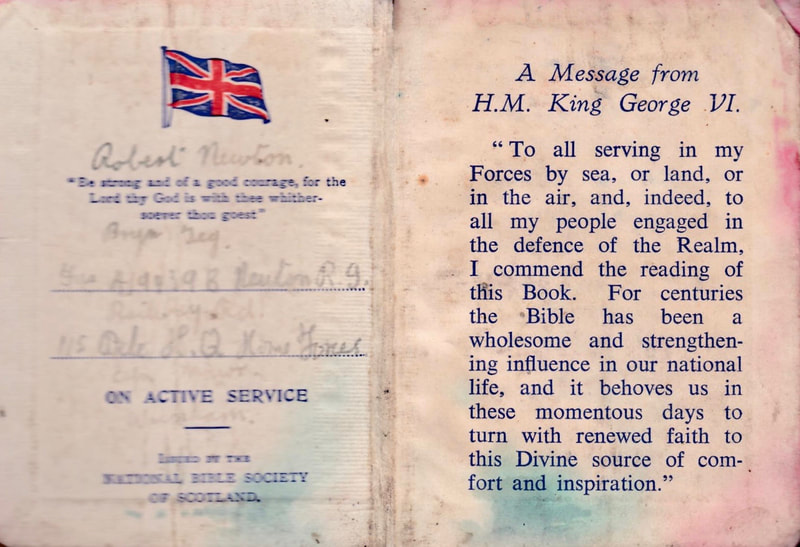

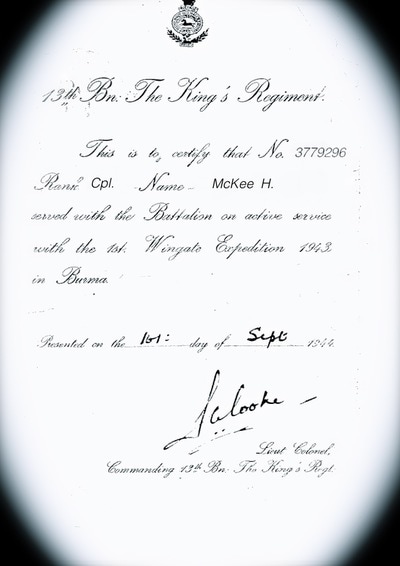

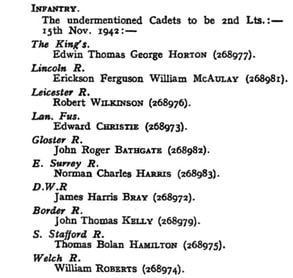

Commission on 15th November 1942.

Commission on 15th November 1942.

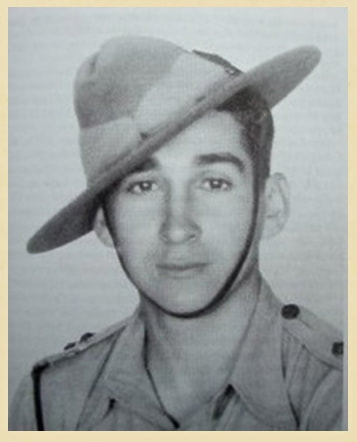

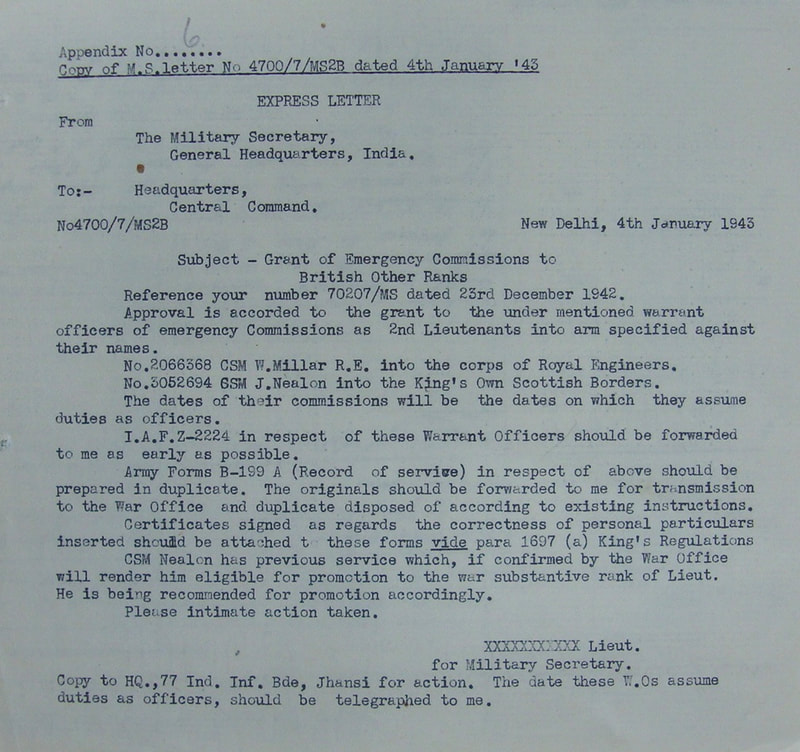

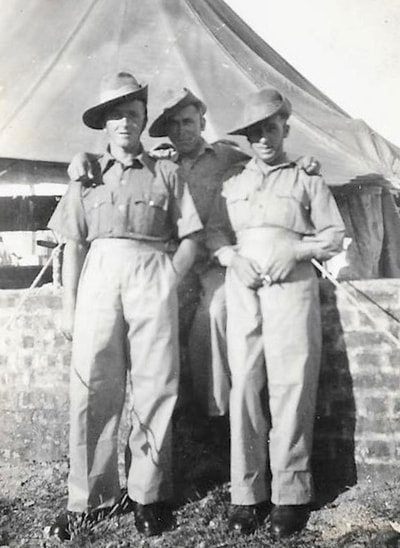

KELLY, JOHN THOMAS

Rank: 2nd Lieutenant

Service No: 268979

Age: 22

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Previous Regiment: The Border Regiment.

Chindit Column: 7

Other details:

2nd Lieutenant John Thomas Kelly arrived at the Chindit training camp in Jhansi on the 22nd December 1942. He had only recently received his commission, gazetted on the 7th May 1943, whilst serving with the Border Regiment. Alongside him on the 22nd December were three other young officers: Ted Horton, formerly of the Lincoln's, Robert Wilkinson of the Leicester Regiment and Gerry Roberts from the Welch Regiment.

Gerry Roberts recalled this moment in his memoirs:

Bob Wilkinson, Jack Kelly, Ted Horton and I were detailed to go to Jhansi to be interviewed by the Brigadier. We had no option and others with less experience I know had been refused. We arrived at Jhansi on the 22nd December 1942, then interviewed on the 23rd and were told we would be attached for operations. All the necessary kit was drawn up and we were tested by compass marching, map reading etc. This went well and we then spent four days training in the jungle with the other columns. These columns already had six months continuous jungle training, yet we had to go in with just a few days under our belts and had do the same work as the other officers. However, we were young and game and had no real worries.

By January 1943, the four men had been split up into the various Chindit columns, with Gerry Roberts going to No. 5 Column, Edwin Horton to No. 8 Column and Robert Wilkinson and John Kelly joining No. 7 Column under the command of Major Kenneth Gilkes of the King's Regiment. It was with No. 7 Column that John Kelly crossed the Chindwin River on the 15th February 1943 and began his period behind enemy lines.

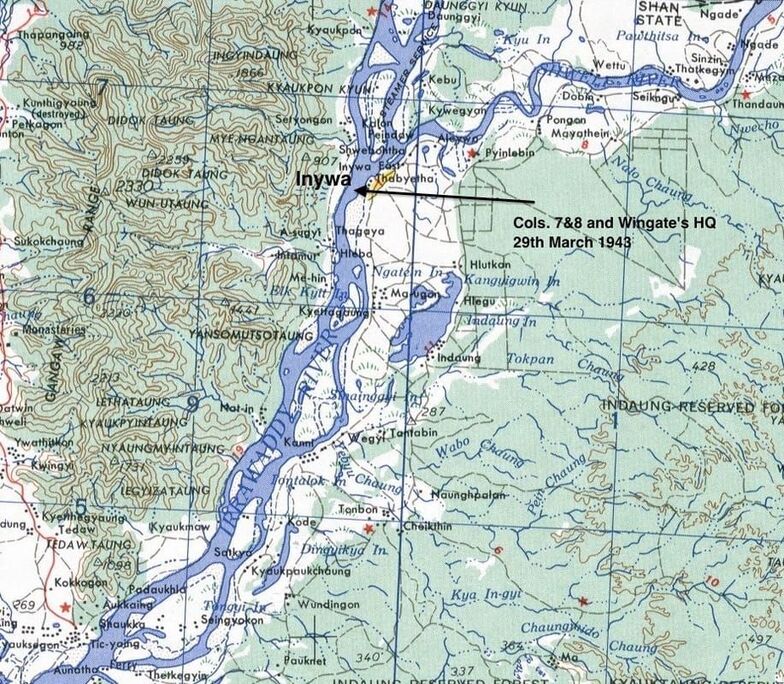

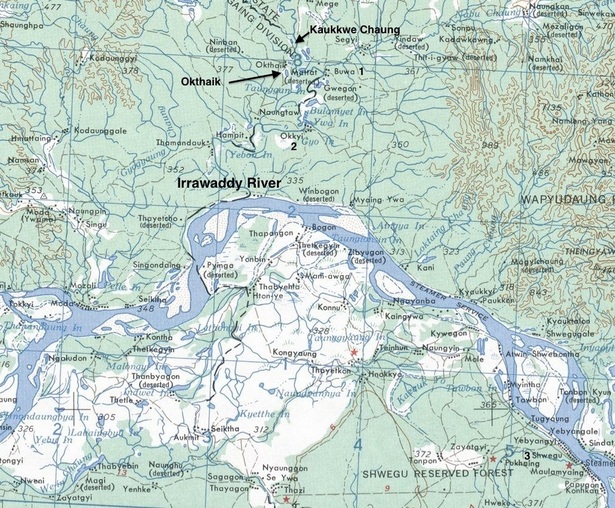

In late March 1943, Wingate called a halt to the operation in Burma, after being instructed by the Army HQ in India to get as many of his now knowledgeable and experienced Chindit Brigade back safely to Allied territory. Wingate's own Brigade HQ had been shielded by Columns 7 and 8 for most of the operation in 1943 and it was these three groups that found themselves on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River on the 29th March, close to the village of Inywa.

Several platoons from No. 7 Column were ordered to cross the river using local country boats in order to secure a bridgehead on the west bank. It is known that Lt. Kelly led his platoon across at this point. Unfortunately, the Japanese were waiting on the far bank and began firing at the Chindit parties as they crossed; heavy mortar and machine gun fire took a heavy toll on the men from 7 Column, but a group of around 40 men including John Kelly did make it ashore and dispersed quickly into the jungle adjacent to the river. The rest of the crossing was duly abandoned and the remainder of No. 7 Column turned tail from Inywa and marched east for the Shweli River. Major Gilkes eventually exited Burma via Yunnan Province (China), a march that would last for over six weeks.

After many days march and with several skirmishes with Japanese patrols along the way, Lt. Kelly and the group of Chindits he was with reached the safety of the Chindwin River. To read more about his return journey to India, please click on the following link: Captain William Alfred Jelliss

Rank: 2nd Lieutenant

Service No: 268979

Age: 22

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Previous Regiment: The Border Regiment.

Chindit Column: 7

Other details:

2nd Lieutenant John Thomas Kelly arrived at the Chindit training camp in Jhansi on the 22nd December 1942. He had only recently received his commission, gazetted on the 7th May 1943, whilst serving with the Border Regiment. Alongside him on the 22nd December were three other young officers: Ted Horton, formerly of the Lincoln's, Robert Wilkinson of the Leicester Regiment and Gerry Roberts from the Welch Regiment.

Gerry Roberts recalled this moment in his memoirs:

Bob Wilkinson, Jack Kelly, Ted Horton and I were detailed to go to Jhansi to be interviewed by the Brigadier. We had no option and others with less experience I know had been refused. We arrived at Jhansi on the 22nd December 1942, then interviewed on the 23rd and were told we would be attached for operations. All the necessary kit was drawn up and we were tested by compass marching, map reading etc. This went well and we then spent four days training in the jungle with the other columns. These columns already had six months continuous jungle training, yet we had to go in with just a few days under our belts and had do the same work as the other officers. However, we were young and game and had no real worries.

By January 1943, the four men had been split up into the various Chindit columns, with Gerry Roberts going to No. 5 Column, Edwin Horton to No. 8 Column and Robert Wilkinson and John Kelly joining No. 7 Column under the command of Major Kenneth Gilkes of the King's Regiment. It was with No. 7 Column that John Kelly crossed the Chindwin River on the 15th February 1943 and began his period behind enemy lines.

In late March 1943, Wingate called a halt to the operation in Burma, after being instructed by the Army HQ in India to get as many of his now knowledgeable and experienced Chindit Brigade back safely to Allied territory. Wingate's own Brigade HQ had been shielded by Columns 7 and 8 for most of the operation in 1943 and it was these three groups that found themselves on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River on the 29th March, close to the village of Inywa.

Several platoons from No. 7 Column were ordered to cross the river using local country boats in order to secure a bridgehead on the west bank. It is known that Lt. Kelly led his platoon across at this point. Unfortunately, the Japanese were waiting on the far bank and began firing at the Chindit parties as they crossed; heavy mortar and machine gun fire took a heavy toll on the men from 7 Column, but a group of around 40 men including John Kelly did make it ashore and dispersed quickly into the jungle adjacent to the river. The rest of the crossing was duly abandoned and the remainder of No. 7 Column turned tail from Inywa and marched east for the Shweli River. Major Gilkes eventually exited Burma via Yunnan Province (China), a march that would last for over six weeks.

After many days march and with several skirmishes with Japanese patrols along the way, Lt. Kelly and the group of Chindits he was with reached the safety of the Chindwin River. To read more about his return journey to India, please click on the following link: Captain William Alfred Jelliss

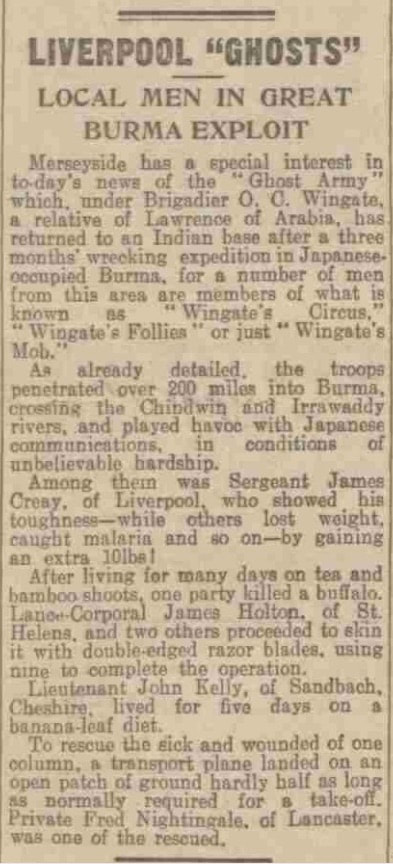

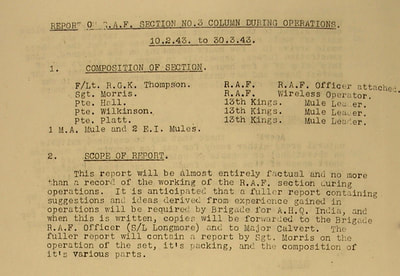

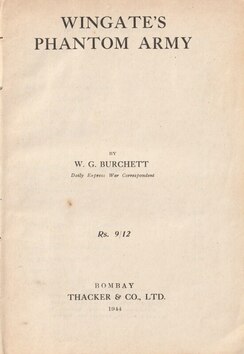

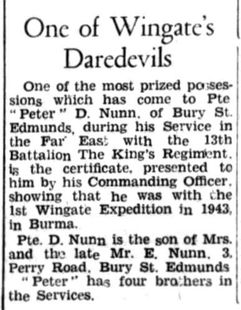

The exploits of the Chindits in 1943 was used quite extensively by Winston Churchill in raising the morale of the Allied troops in India and the British public back home.

An example of this comes from the pages of the Liverpool Echo dated 21st May 1943, in the form of an interesting short story about four men from the local area (including John Kelly) and their experiences during the first Wingate expedition.

Liverpool Ghosts: Local Men in Great Burma Exploit

Merseyside has a special interest in today's news of the Ghost Army which, under Brigadier Orde Charles Wingate, a relative of Lawrence of Arabia, has now returned to an Indian base after a three month wrecking expedition in Japanese occupied Burma. For a number of men from this area are members of what if commonly known as Wingate's Circus. As already detailed, the troops penetrated over 200 miles into Burma, crossing the Chindwin and Irrawaddy Rivers, and played havoc with Japanese communications in conditions of unbelievable hardship.

Among them was Sergeant James Creasy of Liverpool, who showed his toughness, while others lost weight, caught malaria and so on, by gaining himself an extra 10lbs! After living for many days on tea and bamboo shoots, one party killed a buffalo. Lance Corporal James Holton of St. Helens and two other men proceeded to skin the animal with double-edged razor blades, using nine blades to complete the operation. Lieutenant John Kelly of Sandbach in Cheshire, lived for five days on a banana leaf diet. To rescue the sick and wounded of one column, a transport plane landed on an open patch of ground half the length normally required for a take-off. Private Fred Nightingale of Lancaster was among the men rescued.

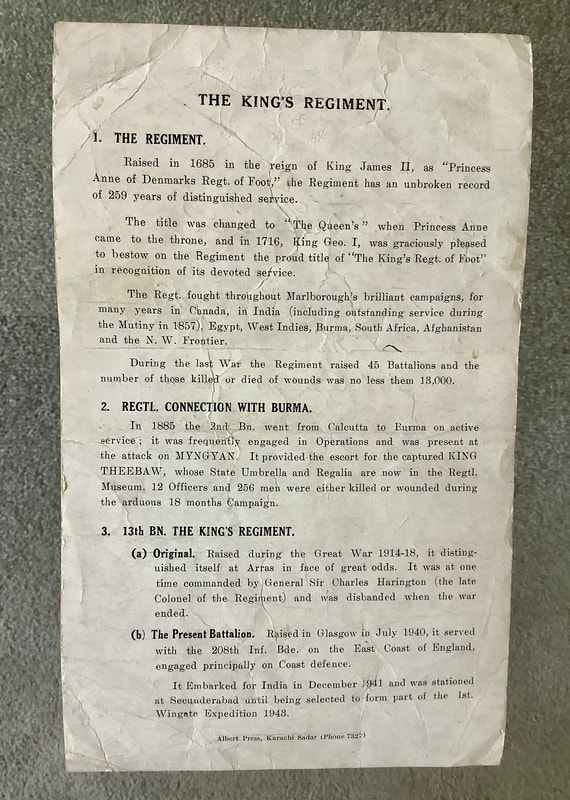

After returning from Burma in 1943, John Kelly and the other survivors from Operation Longcloth enjoyed a long period of rest and recuperation in the hill stations of northern India. Eventually they all rejoined the 13th King's at their new base, the Napier Barracks located at Karachi. John Kelly spent the rest of his service with the King's at Karachi employed for the most part in internal security and garrison duties and was promoted to Captain on the 8th December 1944. From the summer of 1945, many of the Longcloth men still present with the battalion began to be repatriated to the United Kingdom as their overseas service period expired. It is not known exactly when John returned to the UK but the battalion was disbanded on the 5th December 1945, with any remaining Other Ranks being sent over to bolster the strength of the 1st Battalion of the King's now stationed at Dehra Dun.

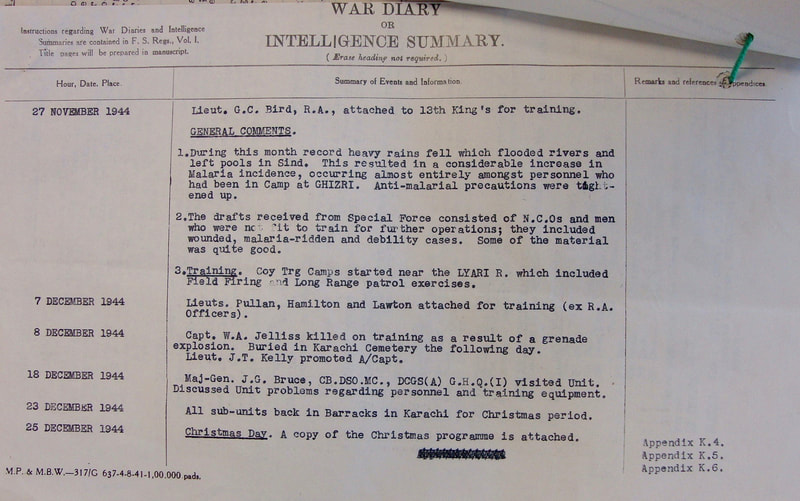

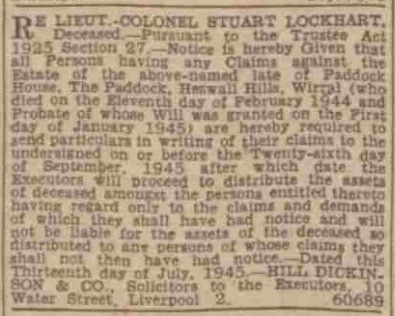

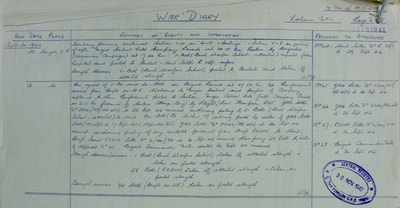

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including notification of John Kelly's promotion to Captain from the 13th King's War diary. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

An example of this comes from the pages of the Liverpool Echo dated 21st May 1943, in the form of an interesting short story about four men from the local area (including John Kelly) and their experiences during the first Wingate expedition.

Liverpool Ghosts: Local Men in Great Burma Exploit

Merseyside has a special interest in today's news of the Ghost Army which, under Brigadier Orde Charles Wingate, a relative of Lawrence of Arabia, has now returned to an Indian base after a three month wrecking expedition in Japanese occupied Burma. For a number of men from this area are members of what if commonly known as Wingate's Circus. As already detailed, the troops penetrated over 200 miles into Burma, crossing the Chindwin and Irrawaddy Rivers, and played havoc with Japanese communications in conditions of unbelievable hardship.

Among them was Sergeant James Creasy of Liverpool, who showed his toughness, while others lost weight, caught malaria and so on, by gaining himself an extra 10lbs! After living for many days on tea and bamboo shoots, one party killed a buffalo. Lance Corporal James Holton of St. Helens and two other men proceeded to skin the animal with double-edged razor blades, using nine blades to complete the operation. Lieutenant John Kelly of Sandbach in Cheshire, lived for five days on a banana leaf diet. To rescue the sick and wounded of one column, a transport plane landed on an open patch of ground half the length normally required for a take-off. Private Fred Nightingale of Lancaster was among the men rescued.

After returning from Burma in 1943, John Kelly and the other survivors from Operation Longcloth enjoyed a long period of rest and recuperation in the hill stations of northern India. Eventually they all rejoined the 13th King's at their new base, the Napier Barracks located at Karachi. John Kelly spent the rest of his service with the King's at Karachi employed for the most part in internal security and garrison duties and was promoted to Captain on the 8th December 1944. From the summer of 1945, many of the Longcloth men still present with the battalion began to be repatriated to the United Kingdom as their overseas service period expired. It is not known exactly when John returned to the UK but the battalion was disbanded on the 5th December 1945, with any remaining Other Ranks being sent over to bolster the strength of the 1st Battalion of the King's now stationed at Dehra Dun.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including notification of John Kelly's promotion to Captain from the 13th King's War diary. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

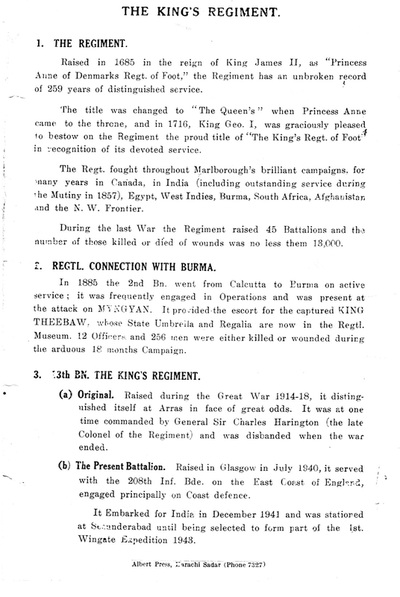

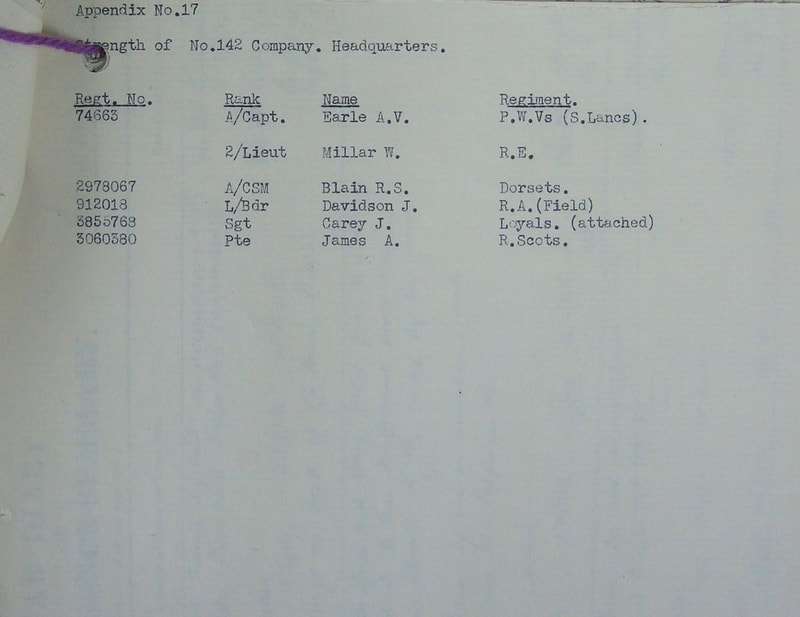

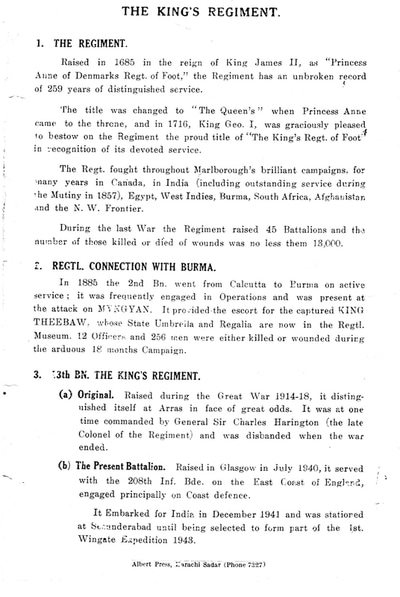

142 Commando insignia.

142 Commando insignia.

KEMBLE, (Captain)

Rank: Captain

Service No: Unknown

Age: Unknown

Regiment/Service: 142 Commando attached The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Previous Regiment: Unknown

Chindit Column: Rear Base (Saugor)

Other details:

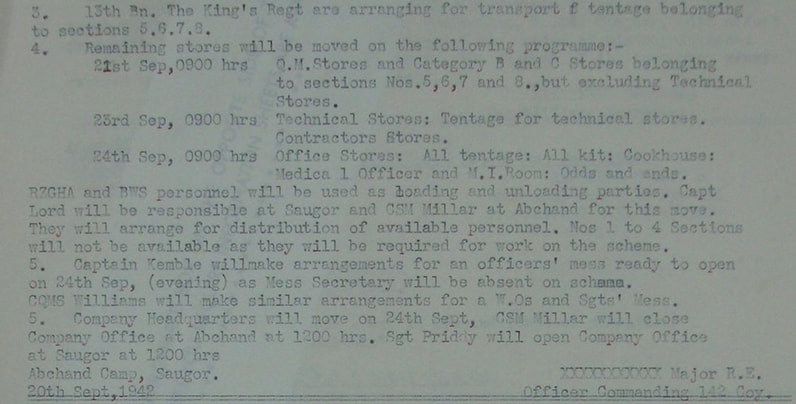

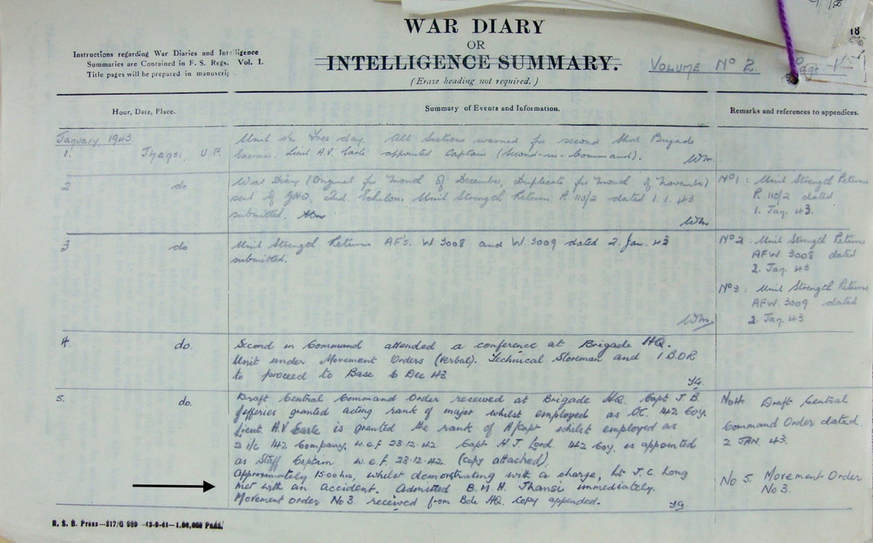

There is only one reference for Captain Kemble from the diaries and writings in relation to the first Chindit expedition in 1943. From the war diary of 142 Commando section, 77 Brigade, we learn that Kemble was the Mess Officer at Saugor and that he was to have the mess room ready and operational by the 24th September 1942. It is not known whether Kemble took part on Operation Longcloth, or remained behind to undertake his catering duties back at the Saugor Camp. Please click on the image below to bring it forward on the page.

Rank: Captain

Service No: Unknown

Age: Unknown

Regiment/Service: 142 Commando attached The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Previous Regiment: Unknown

Chindit Column: Rear Base (Saugor)

Other details:

There is only one reference for Captain Kemble from the diaries and writings in relation to the first Chindit expedition in 1943. From the war diary of 142 Commando section, 77 Brigade, we learn that Kemble was the Mess Officer at Saugor and that he was to have the mess room ready and operational by the 24th September 1942. It is not known whether Kemble took part on Operation Longcloth, or remained behind to undertake his catering duties back at the Saugor Camp. Please click on the image below to bring it forward on the page.

Cap badge of the King's Own Scottish Borderer's.

Cap badge of the King's Own Scottish Borderer's.

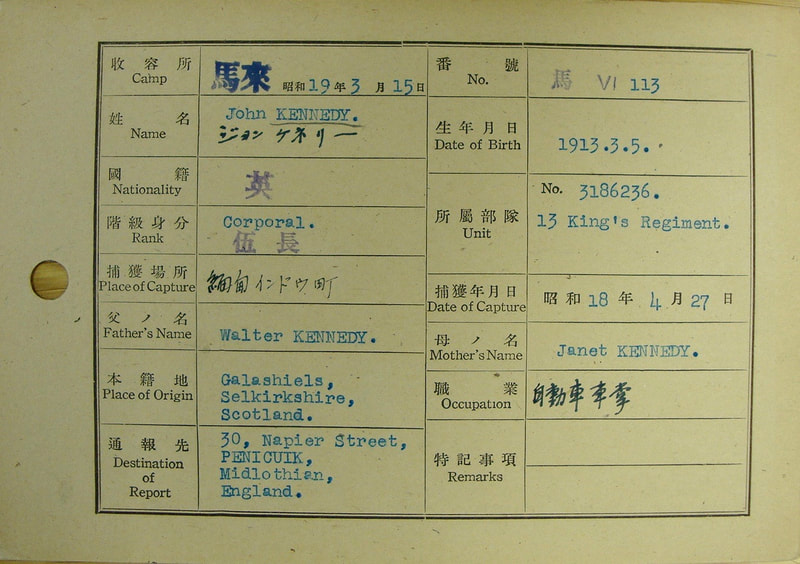

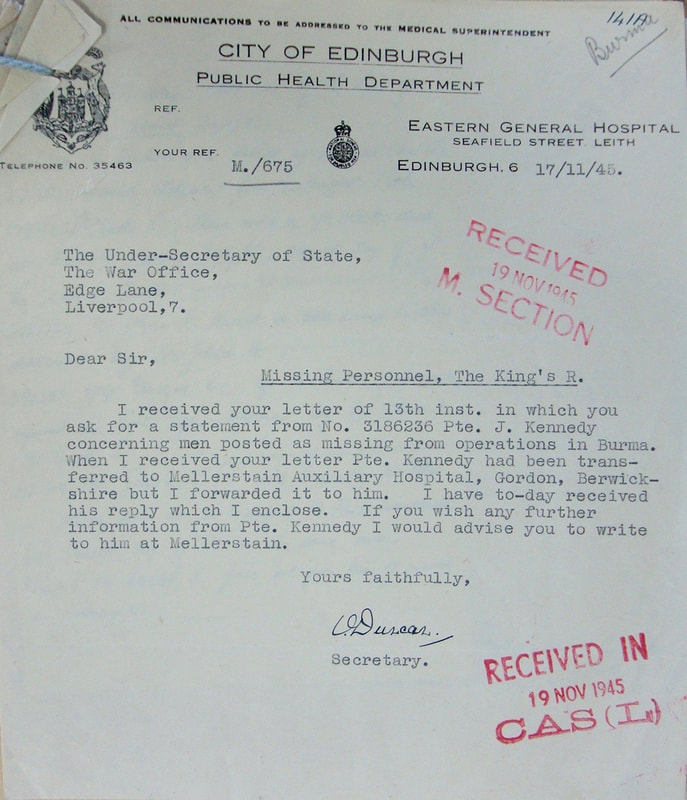

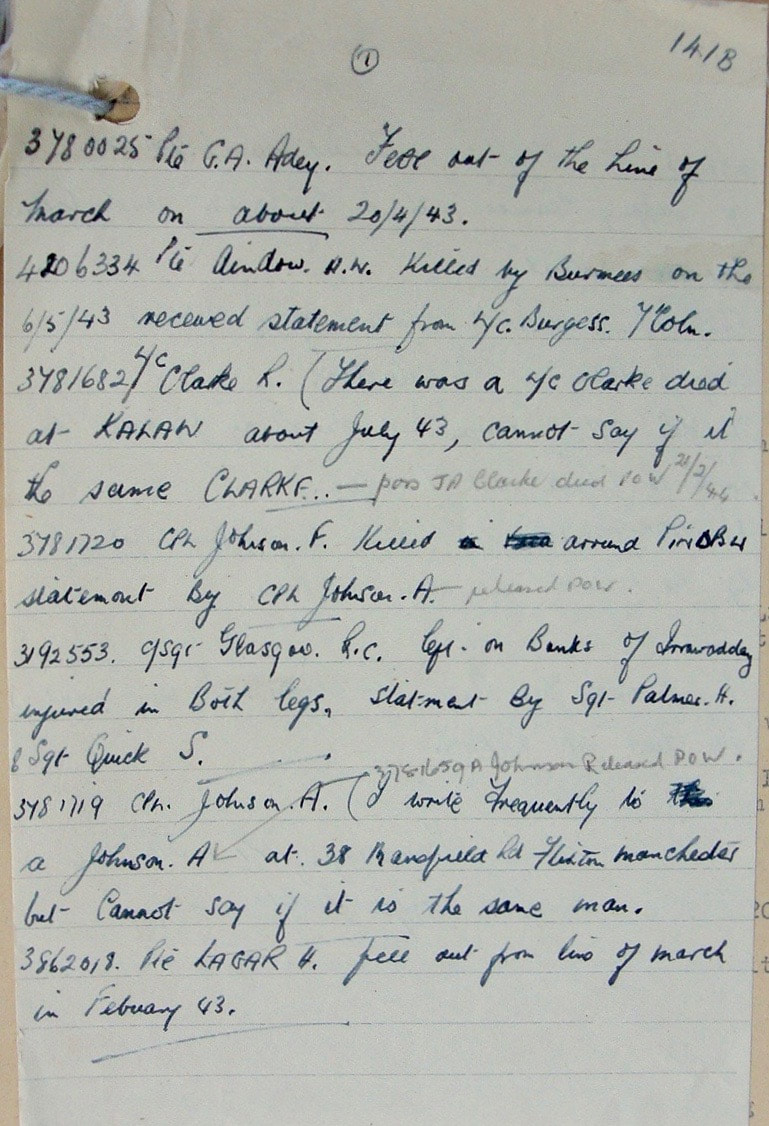

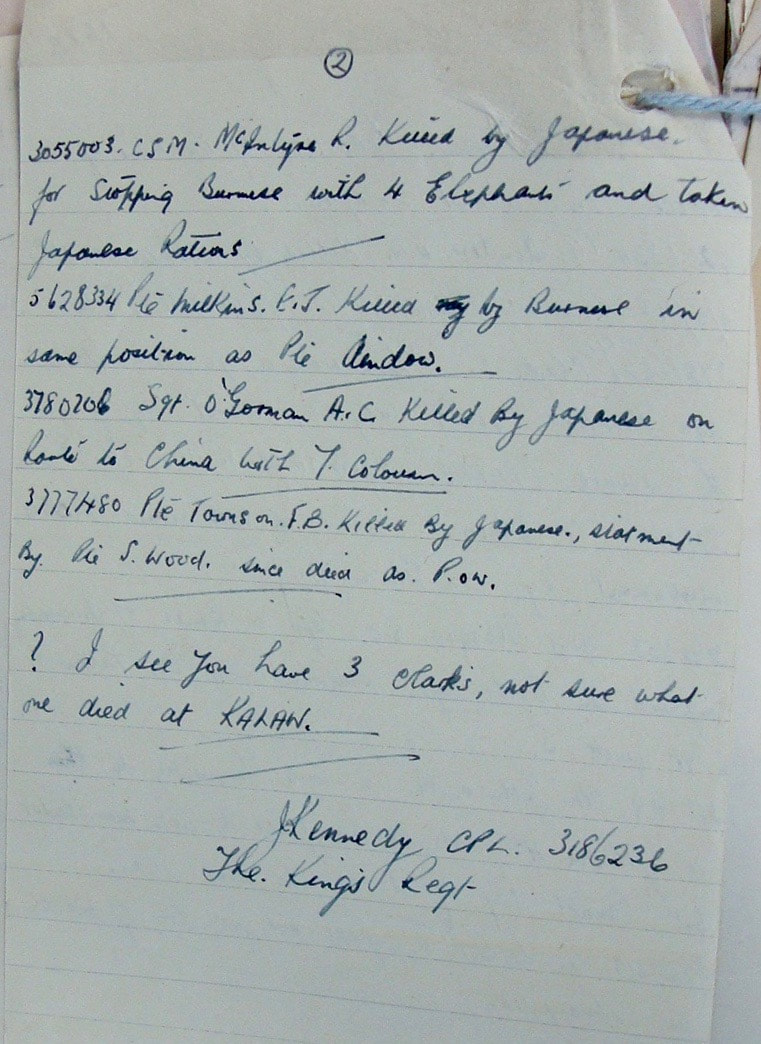

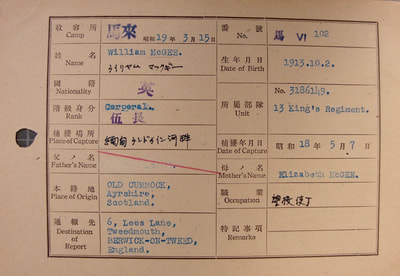

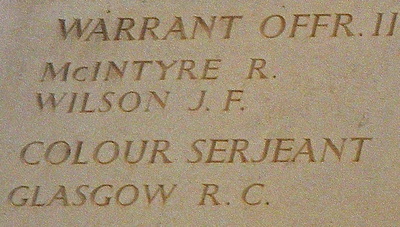

KENNEDY, JOHN

Rank: Corporal

Service No: 3186236

Age: 30

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Previous Regiment: King's Own Scottish Borderer's

Chindit Column: 7

Other details:

John Kennedy was born on the 5th March 1913 and was the son of Walter and Janet Kennedy from Galashiels in Selkirkshire, Scotland. John had enlisted into the Army on the 14th March 1931 and had been transferred to the 13th King's in 1940 as part of a small draft of NCO's originally from the King's Own Scottish Borderer's. He joined the 13th King's at the Jordan Hill Barracks in Glasgow and was posted to C' Company within the battalion.

After performing defence duties with the King's along the south eastern coastline of England, in December 1941, he voyaged with the 13th Battalion to India aboard the troopship Oronsay. The original intention was for the battalion to serve as garrison troops in Secunderabad, looking after internal security and policing the streets of the area and dealing with the increasing civil unrest amongst the Indian population. This all changed in June 1942, when the battalion was unexpectedly given over to Orde Wingate and became the British Infantry element of his newly formed 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

John was allocated to No. 7 Column at the Saugor training camp in the Central Provinces of India and became a Section Commander in one of the column's Rifle Platoons. No. 7 Column was led by Major Kenneth Gilkes also of the King's Regiment, who John would have known from his earlier service with the regiment back in the United Kingdom.

For most of the the journey through the jungles of Burma in 1943, No. 7 Column had kept close to Wingate's own Brigade Head Quarters, protecting and shadowing their leader wherever he went. By late March 1943, many of the men from No. 7 Column were suffering from severe exhaustion, starvation and numerous other afflictions common to the jungles of Burma at that time. After a failed attempt to cross the Irrawaddy River as one body on the 29th March 1943, the Brigade split up into individual dispersal groups.

A group of Chindits, already very ill with diseases such as dysentery and malaria were placed under the leadership of Lieutenant Rex Walker, a young officer from 7 Column. He was given the task by Major Gilkes of taking these men back to India when the column split up into it's dispersal parties. Major Gilkes and the majority of his column then turned eastwards and crossed the Shweli River with the view of exiting Burma via the Kachin Hills and then into the Chinese border province of Yunnan.

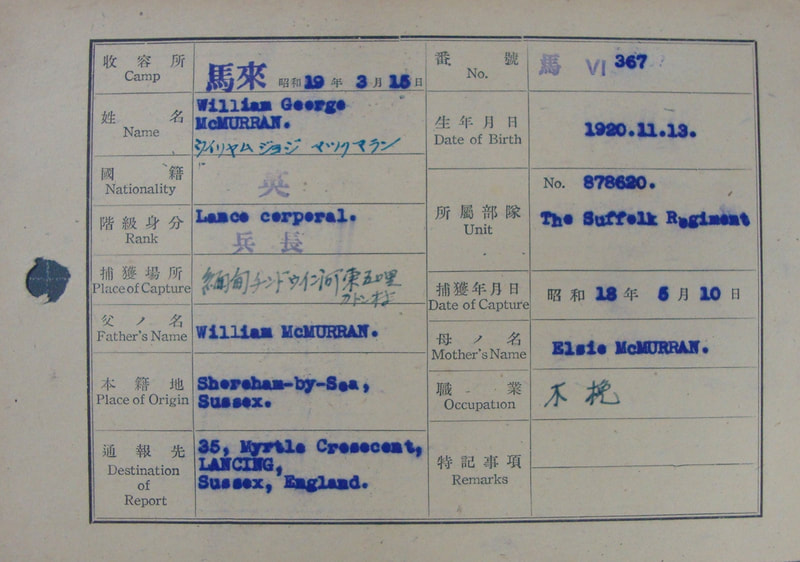

To read the full story of this group, please click on the following link: Rex Walker's Dispersal Group 4

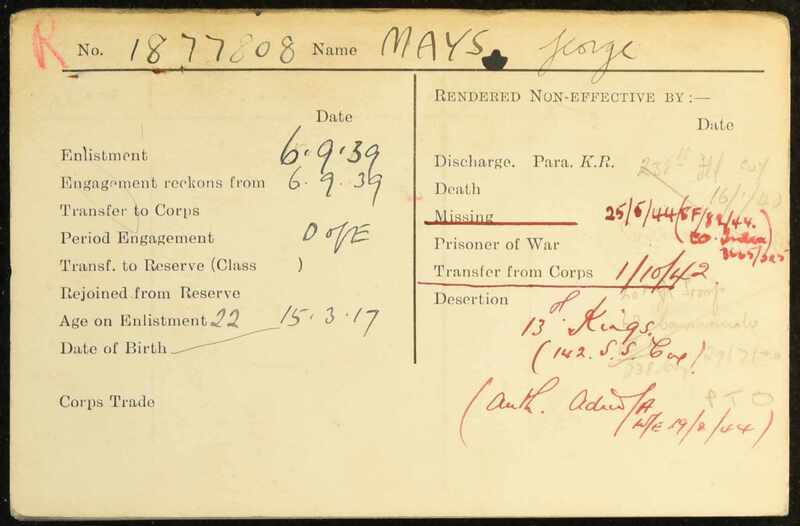

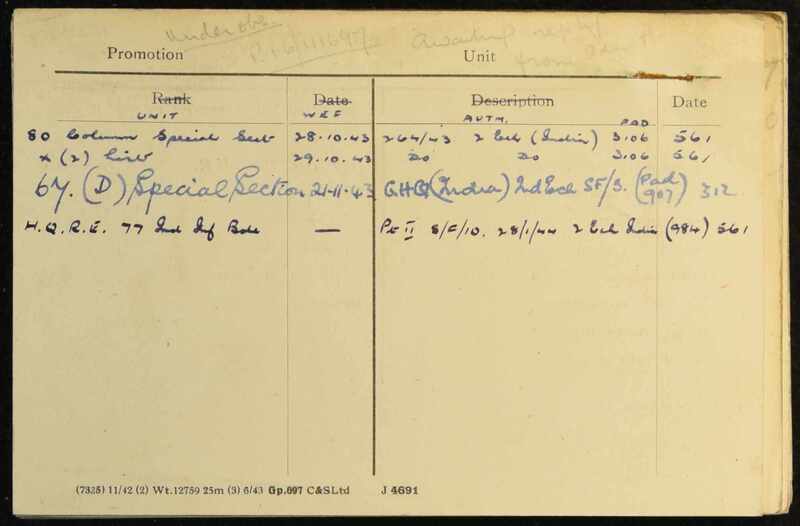

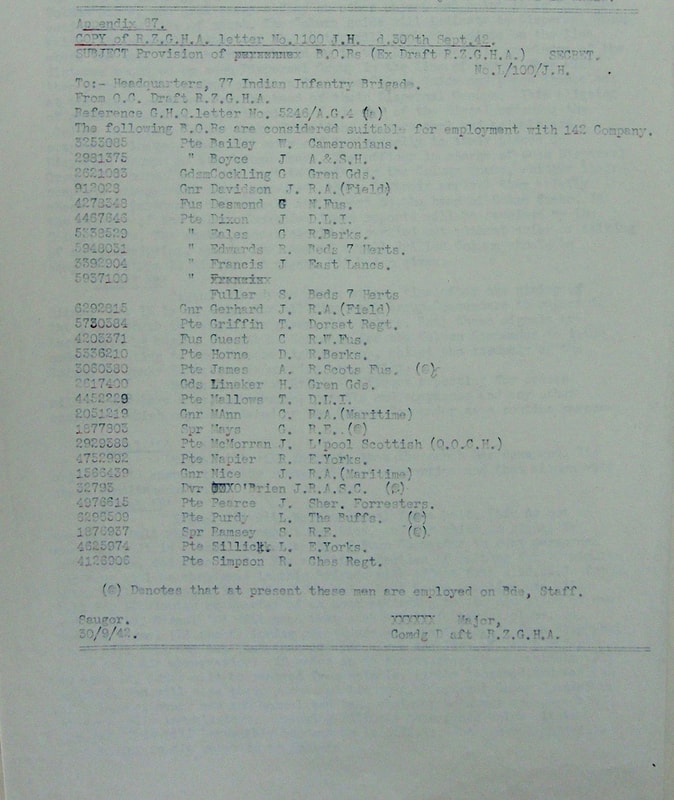

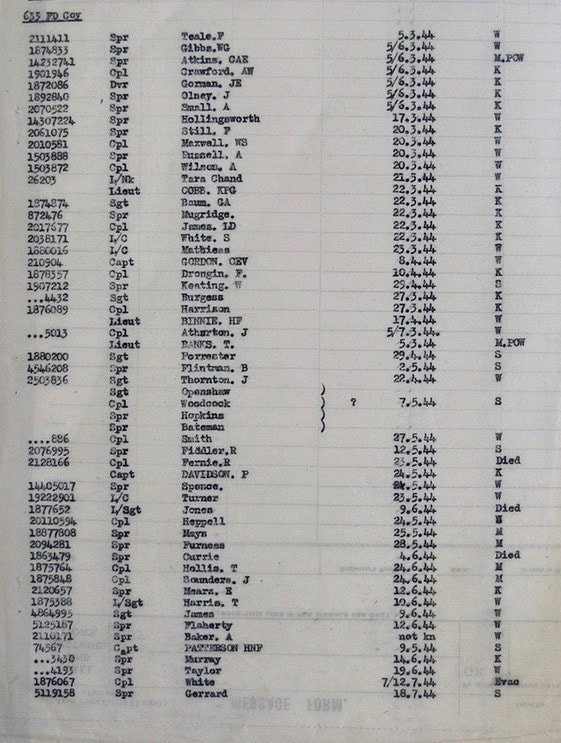

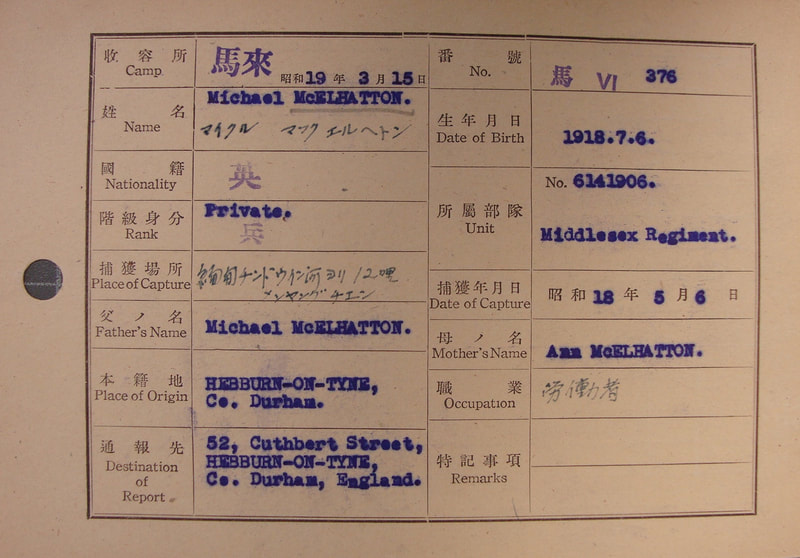

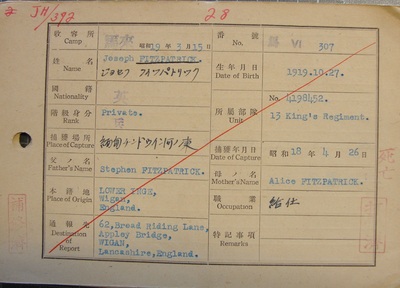

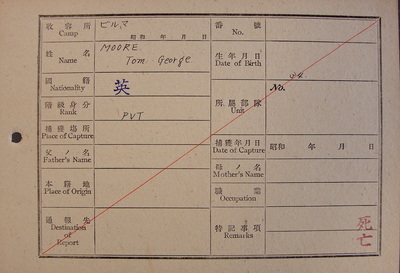

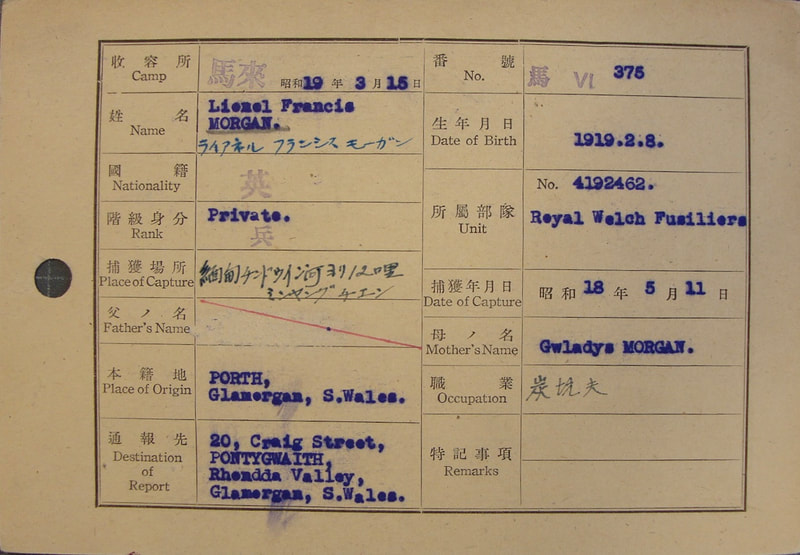

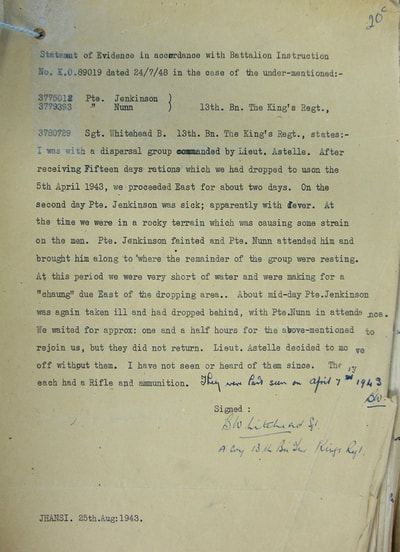

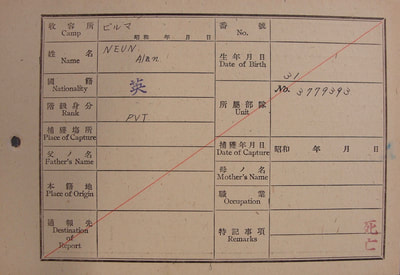

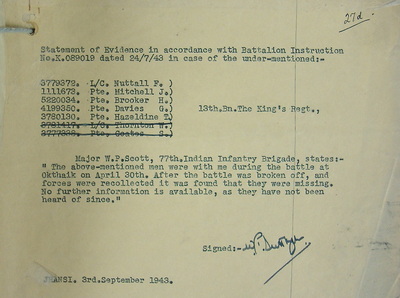

Lt. Walker's party, which included Corporal Kennedy, were now heading due west and attempted to cross the Irrawaddy River on the 10th April 1943; sadly none of the men from this dispersal party ever got over the river. Many were killed during a Japanese ambush, whilst others were taken prisoner. John Kennedy was reported as missing in action as of the 10th April 1943, but according to his POW index card (seen in the gallery below) was actually captured by the Japanese on the 27th April. So it would seem that he and possibly others from the group made an initial escape from the enemy after the engagement at the Irrawaddy. With no access to food other than what he could obtain from local villages, it is to John's great credit that he survived in the Burmese jungle for as long as he did.

Rank: Corporal

Service No: 3186236

Age: 30

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Previous Regiment: King's Own Scottish Borderer's

Chindit Column: 7

Other details:

John Kennedy was born on the 5th March 1913 and was the son of Walter and Janet Kennedy from Galashiels in Selkirkshire, Scotland. John had enlisted into the Army on the 14th March 1931 and had been transferred to the 13th King's in 1940 as part of a small draft of NCO's originally from the King's Own Scottish Borderer's. He joined the 13th King's at the Jordan Hill Barracks in Glasgow and was posted to C' Company within the battalion.

After performing defence duties with the King's along the south eastern coastline of England, in December 1941, he voyaged with the 13th Battalion to India aboard the troopship Oronsay. The original intention was for the battalion to serve as garrison troops in Secunderabad, looking after internal security and policing the streets of the area and dealing with the increasing civil unrest amongst the Indian population. This all changed in June 1942, when the battalion was unexpectedly given over to Orde Wingate and became the British Infantry element of his newly formed 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

John was allocated to No. 7 Column at the Saugor training camp in the Central Provinces of India and became a Section Commander in one of the column's Rifle Platoons. No. 7 Column was led by Major Kenneth Gilkes also of the King's Regiment, who John would have known from his earlier service with the regiment back in the United Kingdom.

For most of the the journey through the jungles of Burma in 1943, No. 7 Column had kept close to Wingate's own Brigade Head Quarters, protecting and shadowing their leader wherever he went. By late March 1943, many of the men from No. 7 Column were suffering from severe exhaustion, starvation and numerous other afflictions common to the jungles of Burma at that time. After a failed attempt to cross the Irrawaddy River as one body on the 29th March 1943, the Brigade split up into individual dispersal groups.

A group of Chindits, already very ill with diseases such as dysentery and malaria were placed under the leadership of Lieutenant Rex Walker, a young officer from 7 Column. He was given the task by Major Gilkes of taking these men back to India when the column split up into it's dispersal parties. Major Gilkes and the majority of his column then turned eastwards and crossed the Shweli River with the view of exiting Burma via the Kachin Hills and then into the Chinese border province of Yunnan.

To read the full story of this group, please click on the following link: Rex Walker's Dispersal Group 4

Lt. Walker's party, which included Corporal Kennedy, were now heading due west and attempted to cross the Irrawaddy River on the 10th April 1943; sadly none of the men from this dispersal party ever got over the river. Many were killed during a Japanese ambush, whilst others were taken prisoner. John Kennedy was reported as missing in action as of the 10th April 1943, but according to his POW index card (seen in the gallery below) was actually captured by the Japanese on the 27th April. So it would seem that he and possibly others from the group made an initial escape from the enemy after the engagement at the Irrawaddy. With no access to food other than what he could obtain from local villages, it is to John's great credit that he survived in the Burmese jungle for as long as he did.

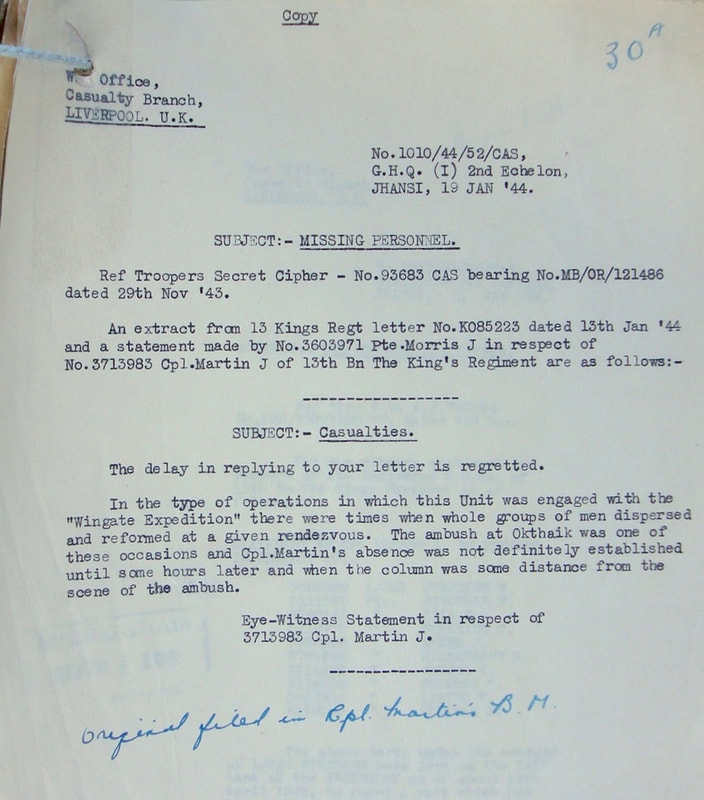

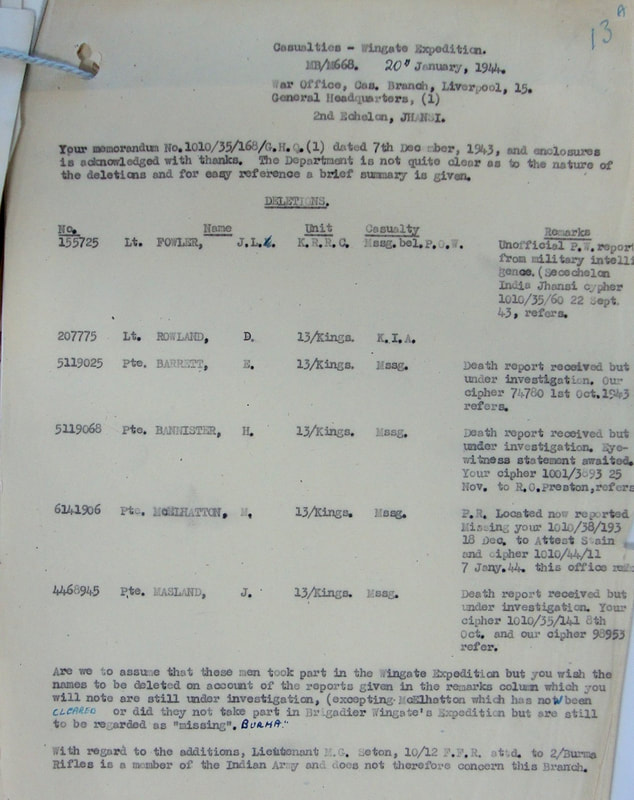

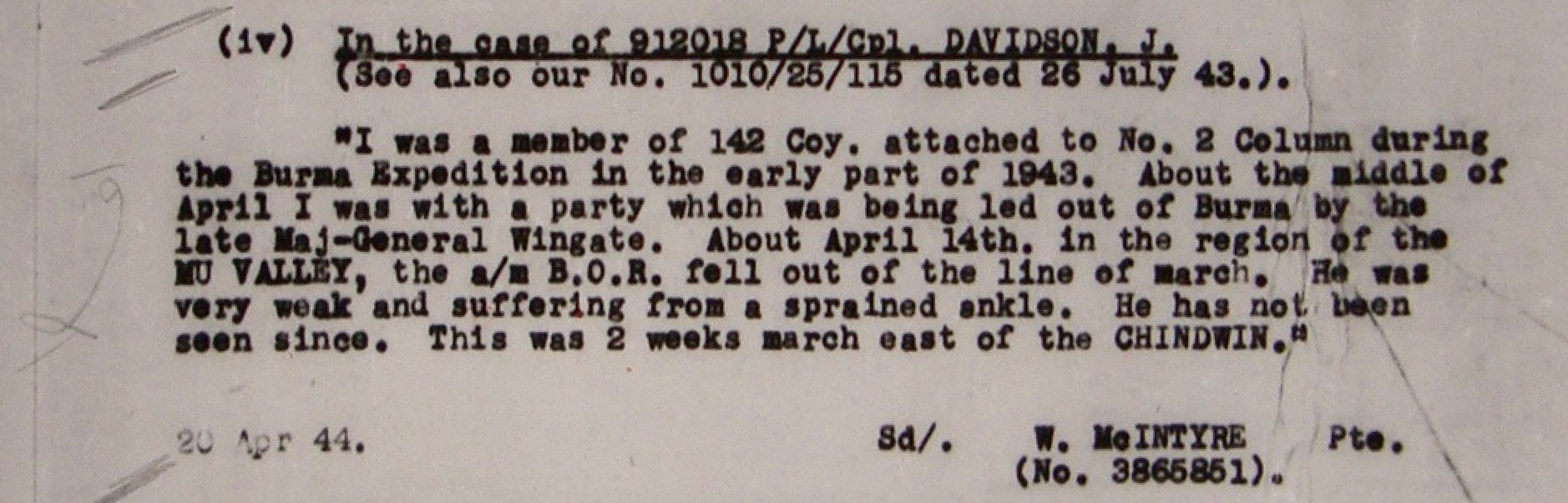

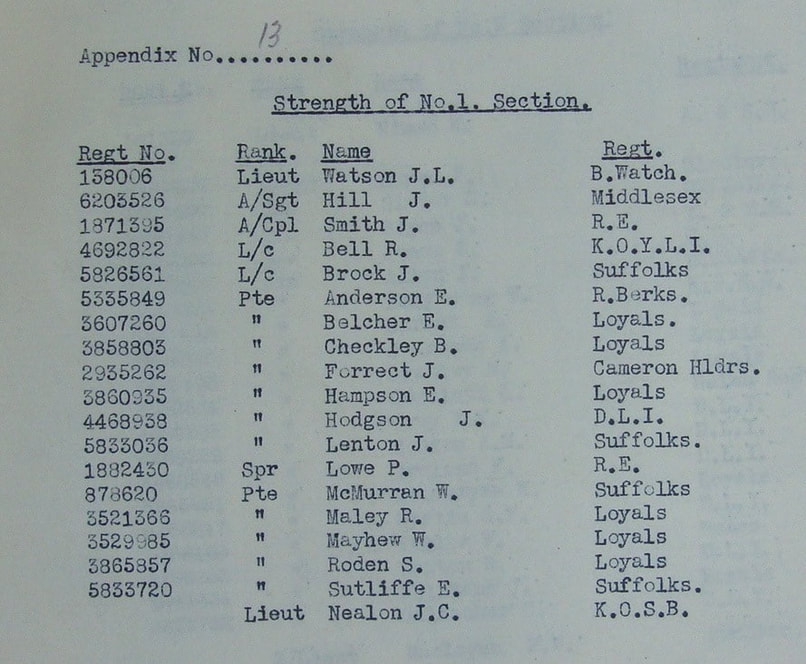

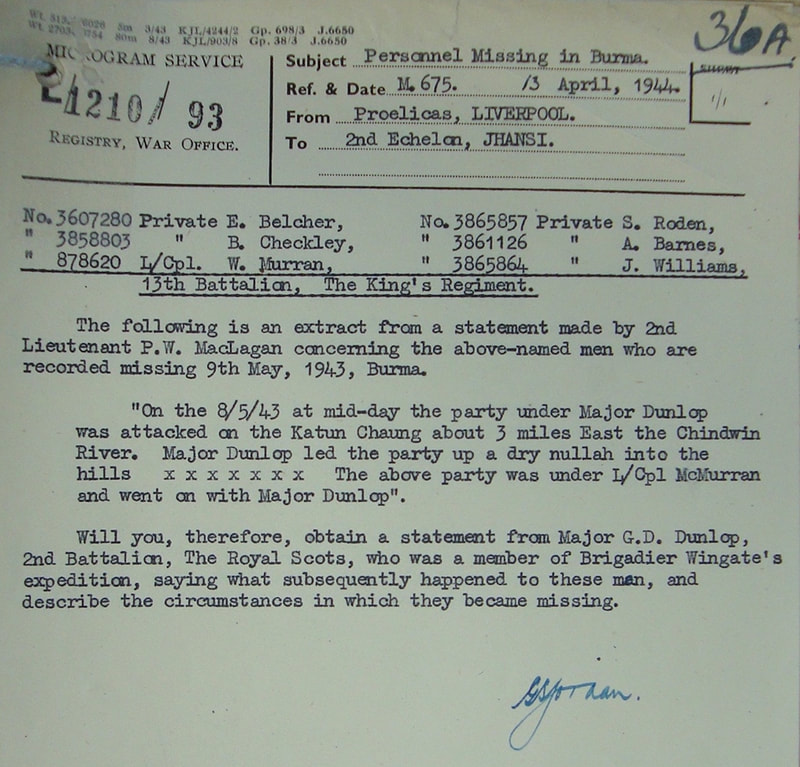

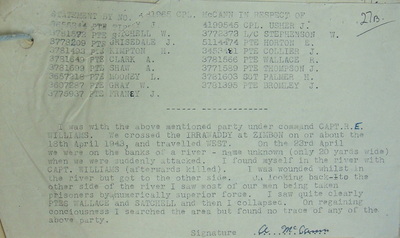

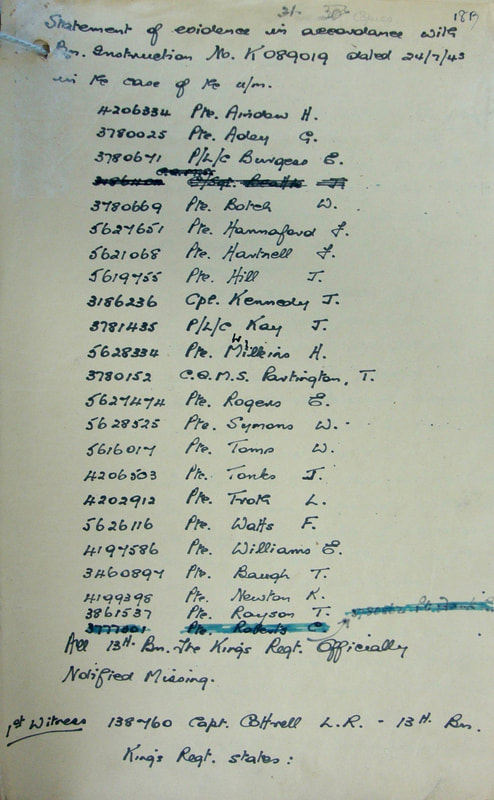

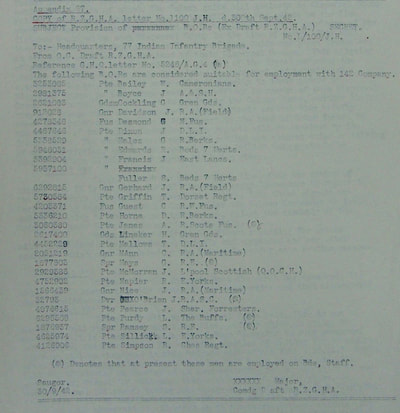

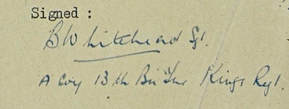

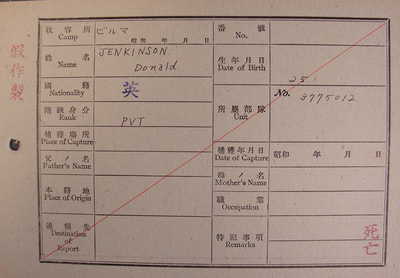

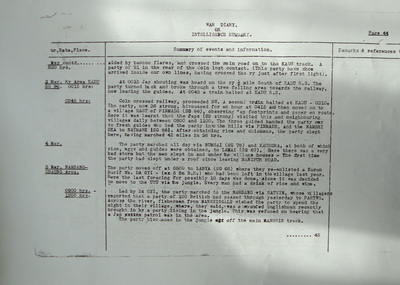

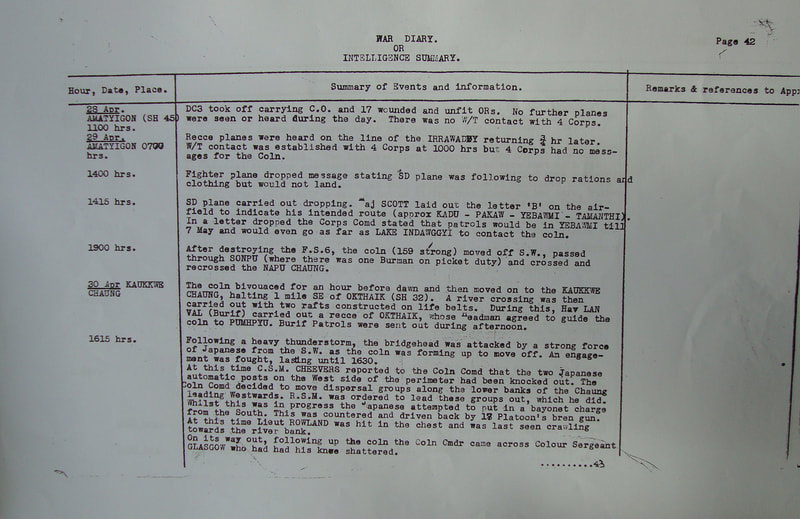

As mentioned earlier, John's dispersal group were last seen on or about the 10th April. Here is a transcription of a report made by Captain Leslie Cottrell, who was 7 Column Adjutant on Operation Longcloth:

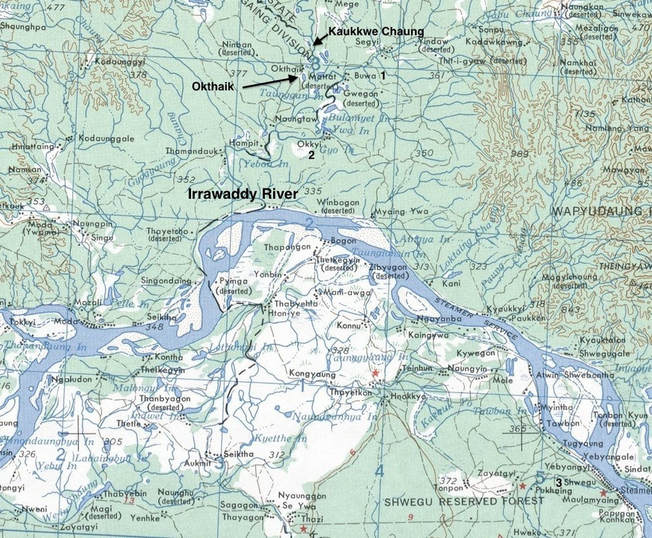

Statement of evidence as of 24th of July 1943.

Witness. 138760 Capt. L.R. Cottrell.

"I was Staff Officer of number seven Column, during Brigadier Wingate's Burma expedition. On April 10th, 1943, the Column Commander (Gilkes) decided for various tactical and administrative reasons to split his column. This was mid-way between the Mongmit and the Myitson Road.

Lieutenant Walker was ordered to take charge of a party which consisted of three other officers and 25 British Other Ranks. His orders were to march approximately westward, re-cross the Irrawaddy and return to Assam by the most direct route. The British Other Ranks were not considered by the Column Commander or by the Medical Officer as physically capable of marching the long way out via China, as the main body intended to do.

They were all equipped with arms and ammunition and had two days hard scale rations each, the officers had maps and compasses. An Air Supply drop was arranged for them just west of the Irrawaddy, but, the party failed to make the rendezvous and the aircraft concerned did not locate them. The Japanese were fairly active in this area. Nothing has been heard of any of these Officers or men since."

Signed. Leslie Cottrell, Captain.

Counter-signed. H. Cotton, Captain.

Of the 29 men who made up Lieutenant Walker's dispersal party, only five survived the war and returned home to the UK. The majority were taken prisoner by the Japanese at various times after the 11th April. Some died in POW transit camps, possibly in places like Kalaw and Maymyo, others made the final journey down to Rangoon, only to perish in Block 6 of the jail, succumbing to dreadful diseases such as dysentery and beri beri.

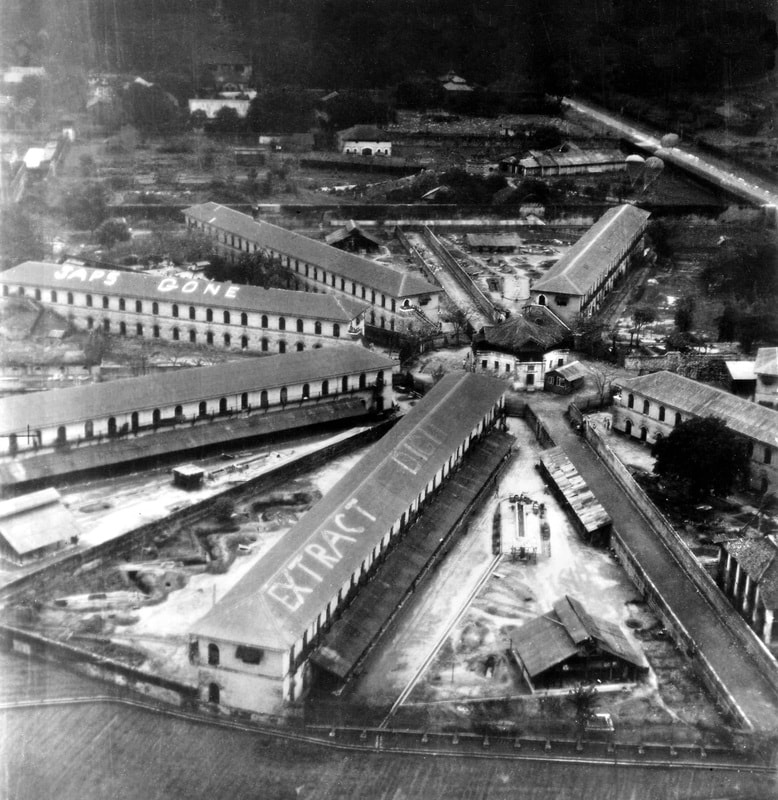

According to John Kennedy's POW records, he was held originally at the transitory prisoner of war camp in Kalaw and was then transferred, along with many of his Chindit comrades to Rangoon Central Jail. Inside the prison, he was given the POW no. 113 and was made to recite this number in Japanese, ichi-ichi-san, at every morning and evening roll-call. John worked as a labourer for the Japanese during his two years as a POW, often unloading cargo from ships down at the city docks.

To read more about the Chindits who became prisoners of war, please click on the following link: Chindit POW's

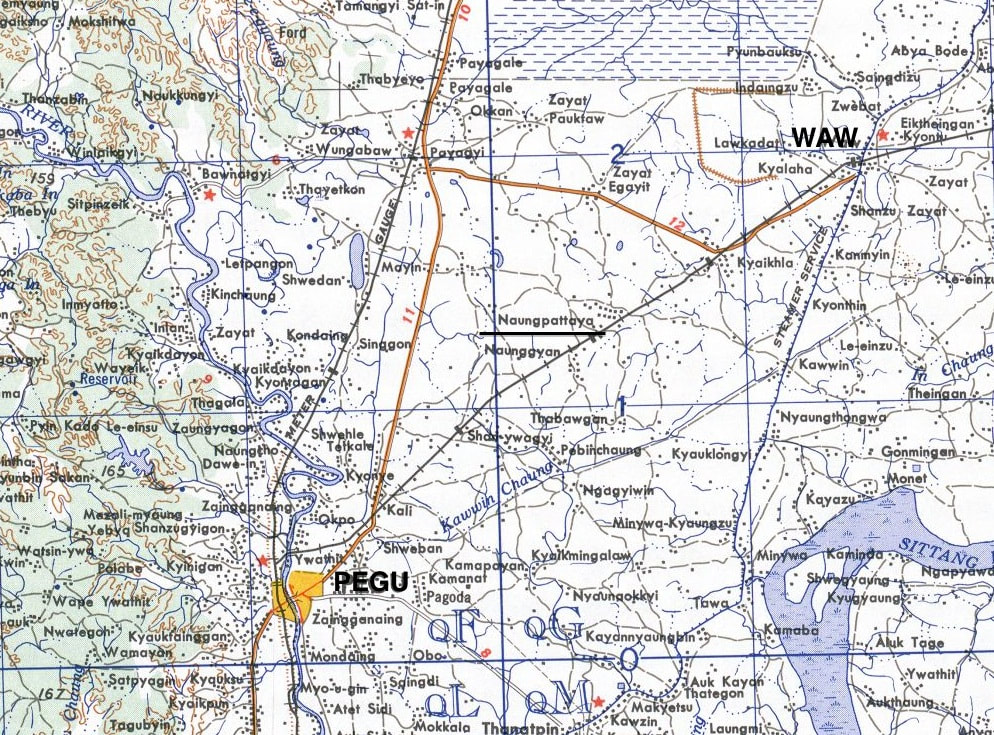

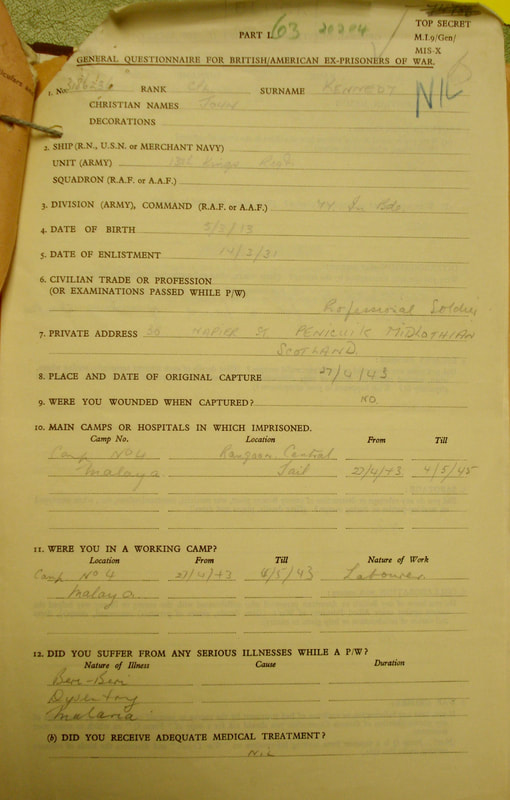

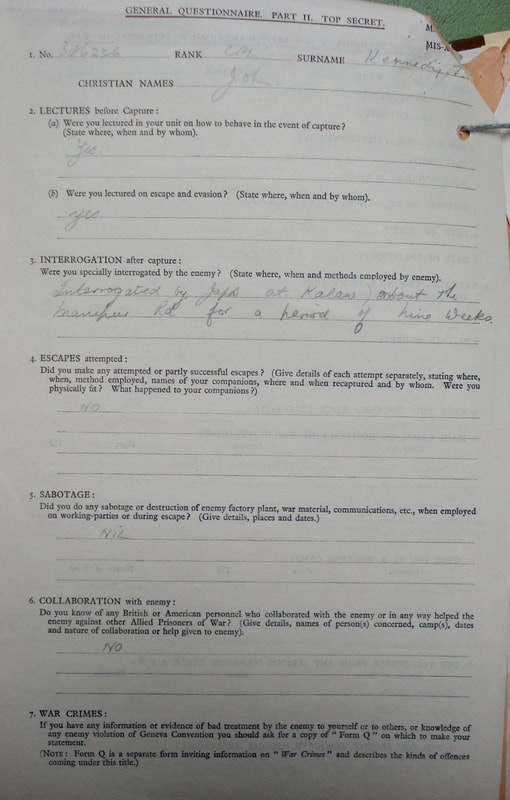

John was liberated as a prisoner of war in late April 1945, whilst marching with some 400 other POW's on the Pegu Road, just north of Rangoon. After returning to India by a Dakota aeroplane and a period in hospital at Calcutta, where he was treated for malaria, dysentery and beri beri, on the 6th June, John agreed to complete what has become known as a Liberation Questionnaire.

This document recorded the history of the prisoner in question, stating the camps he had been held at, the work he had been asked to do and how he had been treated by the Japanese he encountered. After the war, John also gave a series of witness statements in relation to some of the men he had served with on Operation Longcloth and then as a prisoner of war. Later in 1945, probably around October or November, John would have been repatriated to the UK. According to his POW records he was admitted to the Mellerstain Auxiliary Hospital, located at Gordon in Berwickshire.

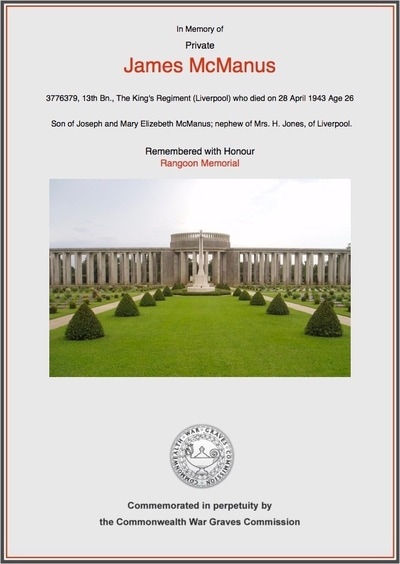

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this narrative, including some of the witness statements mentioned above. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Statement of evidence as of 24th of July 1943.

Witness. 138760 Capt. L.R. Cottrell.

"I was Staff Officer of number seven Column, during Brigadier Wingate's Burma expedition. On April 10th, 1943, the Column Commander (Gilkes) decided for various tactical and administrative reasons to split his column. This was mid-way between the Mongmit and the Myitson Road.

Lieutenant Walker was ordered to take charge of a party which consisted of three other officers and 25 British Other Ranks. His orders were to march approximately westward, re-cross the Irrawaddy and return to Assam by the most direct route. The British Other Ranks were not considered by the Column Commander or by the Medical Officer as physically capable of marching the long way out via China, as the main body intended to do.

They were all equipped with arms and ammunition and had two days hard scale rations each, the officers had maps and compasses. An Air Supply drop was arranged for them just west of the Irrawaddy, but, the party failed to make the rendezvous and the aircraft concerned did not locate them. The Japanese were fairly active in this area. Nothing has been heard of any of these Officers or men since."

Signed. Leslie Cottrell, Captain.

Counter-signed. H. Cotton, Captain.

Of the 29 men who made up Lieutenant Walker's dispersal party, only five survived the war and returned home to the UK. The majority were taken prisoner by the Japanese at various times after the 11th April. Some died in POW transit camps, possibly in places like Kalaw and Maymyo, others made the final journey down to Rangoon, only to perish in Block 6 of the jail, succumbing to dreadful diseases such as dysentery and beri beri.

According to John Kennedy's POW records, he was held originally at the transitory prisoner of war camp in Kalaw and was then transferred, along with many of his Chindit comrades to Rangoon Central Jail. Inside the prison, he was given the POW no. 113 and was made to recite this number in Japanese, ichi-ichi-san, at every morning and evening roll-call. John worked as a labourer for the Japanese during his two years as a POW, often unloading cargo from ships down at the city docks.

To read more about the Chindits who became prisoners of war, please click on the following link: Chindit POW's

John was liberated as a prisoner of war in late April 1945, whilst marching with some 400 other POW's on the Pegu Road, just north of Rangoon. After returning to India by a Dakota aeroplane and a period in hospital at Calcutta, where he was treated for malaria, dysentery and beri beri, on the 6th June, John agreed to complete what has become known as a Liberation Questionnaire.

This document recorded the history of the prisoner in question, stating the camps he had been held at, the work he had been asked to do and how he had been treated by the Japanese he encountered. After the war, John also gave a series of witness statements in relation to some of the men he had served with on Operation Longcloth and then as a prisoner of war. Later in 1945, probably around October or November, John would have been repatriated to the UK. According to his POW records he was admitted to the Mellerstain Auxiliary Hospital, located at Gordon in Berwickshire.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this narrative, including some of the witness statements mentioned above. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Cap badge of the King's Regiment.

Cap badge of the King's Regiment.

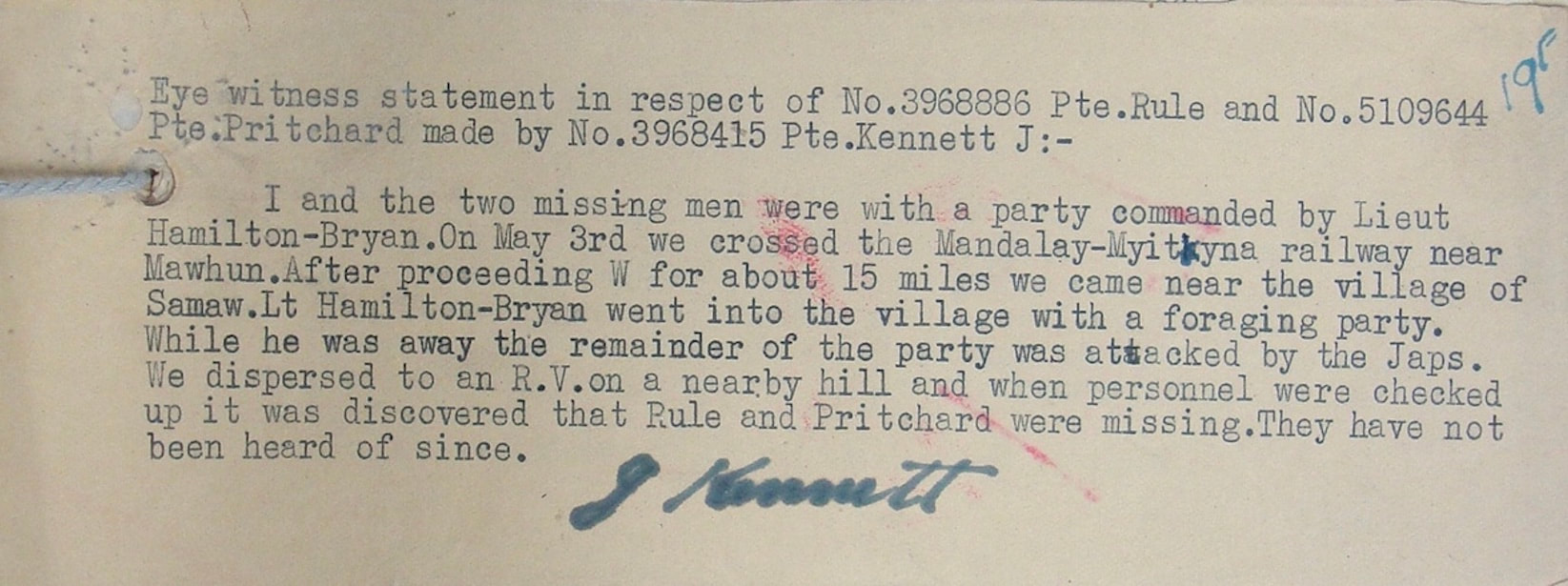

KENNETT, J.

Rank: Private

Service No: 3968415

Age: Unknown

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Chindit Column: 8

Other details:

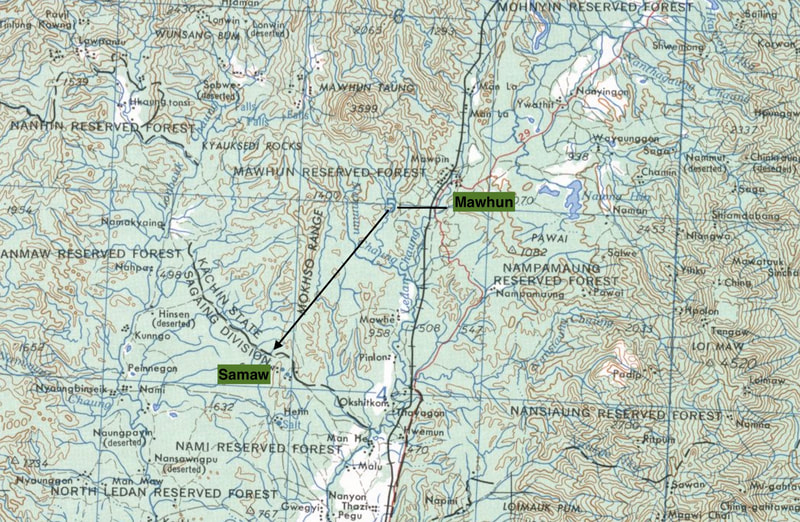

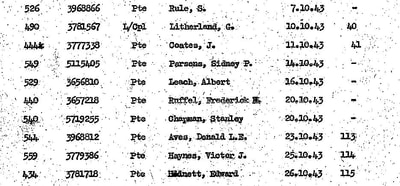

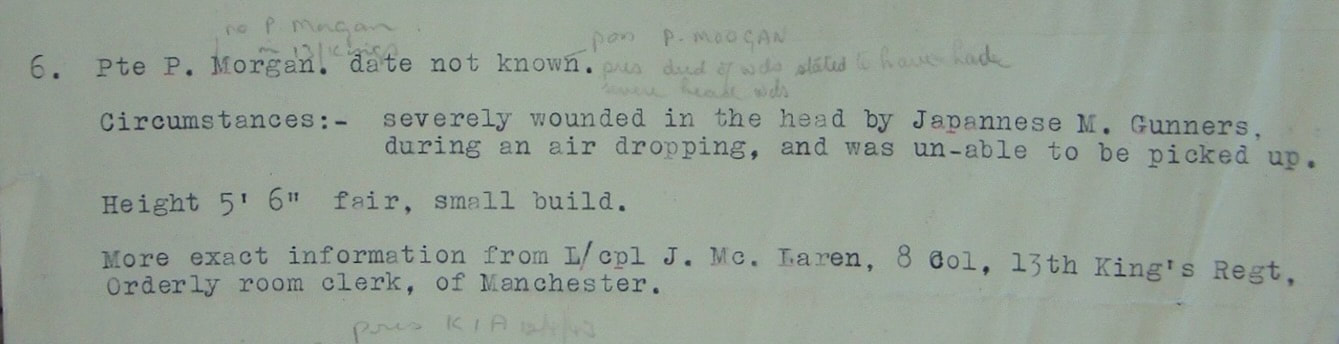

Pte. Kennett (christian name unknown), formerly of the Welch Regiment was posted to the 13th King's in the autumn of 1942 during the training period for Operation Longcloth at Saugor in the Central Provinces of India. At Saugor, Kennett was allocated to No. 8 Column, commanded by Major Walter Purcell Scott. After the expedition was over, Kennett gave a witness statement in relation to two of the men he was with on dispersal in April/May 1943: Pte. 5109644 George Pritchard and Pte. 3968886 Stanley Herbert Rule:

I and the two missing men were with a party commanded by Lieutenant Hamilton-Bryan. On May 3rd, we crossed the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway near Mawhun. After proceeding west for about 15 miles we came near the village of Samaw. Lt. Hamilton-Byran went into the village with a foraging party. While he was away the remainder of the party was attacked by the Japanese. We dispersed to a RV (rendezvous point) on a nearby hill and when personnel were checked up on, it was discovered that Rule and Pritchard were missing. They have not been heard of since.

On the 14th April 1943, Major Scott had decided to split his column up for the dispersal journey back to India. The responsibility for a group of previously wounded men, mostly stretcher cases was given to Lt. Hamilton-Bryan and the column medical officer, Captain Heathcote. Their orders were to find a friendly Burmese village in which to handover the sick and wounded men and then rejoin the main body of the column at an agreed rendezvous position near the Irrawaddy River. It is likely that Kennett, Rule and Pritchard had been seconded to this party as stretcher-bearers.

Rank: Private

Service No: 3968415

Age: Unknown

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Chindit Column: 8

Other details:

Pte. Kennett (christian name unknown), formerly of the Welch Regiment was posted to the 13th King's in the autumn of 1942 during the training period for Operation Longcloth at Saugor in the Central Provinces of India. At Saugor, Kennett was allocated to No. 8 Column, commanded by Major Walter Purcell Scott. After the expedition was over, Kennett gave a witness statement in relation to two of the men he was with on dispersal in April/May 1943: Pte. 5109644 George Pritchard and Pte. 3968886 Stanley Herbert Rule:

I and the two missing men were with a party commanded by Lieutenant Hamilton-Bryan. On May 3rd, we crossed the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway near Mawhun. After proceeding west for about 15 miles we came near the village of Samaw. Lt. Hamilton-Byran went into the village with a foraging party. While he was away the remainder of the party was attacked by the Japanese. We dispersed to a RV (rendezvous point) on a nearby hill and when personnel were checked up on, it was discovered that Rule and Pritchard were missing. They have not been heard of since.

On the 14th April 1943, Major Scott had decided to split his column up for the dispersal journey back to India. The responsibility for a group of previously wounded men, mostly stretcher cases was given to Lt. Hamilton-Bryan and the column medical officer, Captain Heathcote. Their orders were to find a friendly Burmese village in which to handover the sick and wounded men and then rejoin the main body of the column at an agreed rendezvous position near the Irrawaddy River. It is likely that Kennett, Rule and Pritchard had been seconded to this party as stretcher-bearers.

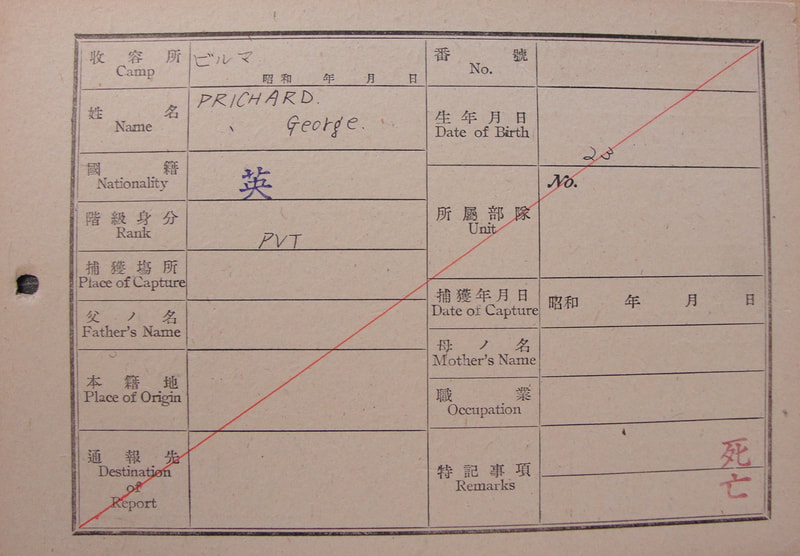

George Pritchard was the son of George (senior) and Violet Pritchard from Aston, a suburb of the city of Birmingham. He had started his war service with the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, before being posted to the 13th King's in India during September 1942. As mentioned by Pte. Kennett, George Pritchard went missing at the village of Samaw on the 3rd May 1943.

We know from prisoner of war records that he was captured the very same day and was taken eventually to Rangoon Central Jail, where he sadly perished in Block 6 of the prison on the 22nd June. He had been allocated the POW no. 423 at Rangoon and was originally buried at the English Cantonment Cemetery (grave no. 58) in the eastern sector of the city near the Royal Lakes. After the war, all burials from the Cantonment Cemetery were moved over to Rangoon War Cemetery and this is where George lies today. George Pritchard is also remembered in the Birmingham Book of Remembrance for WW2. The photograph seen left, is taken from the Prisoner of War newspaper and was kindly sent to me by WW2 researcher, Tony Honeyman.

CWGC details for George Pritchard: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2261097/george-pritchard/

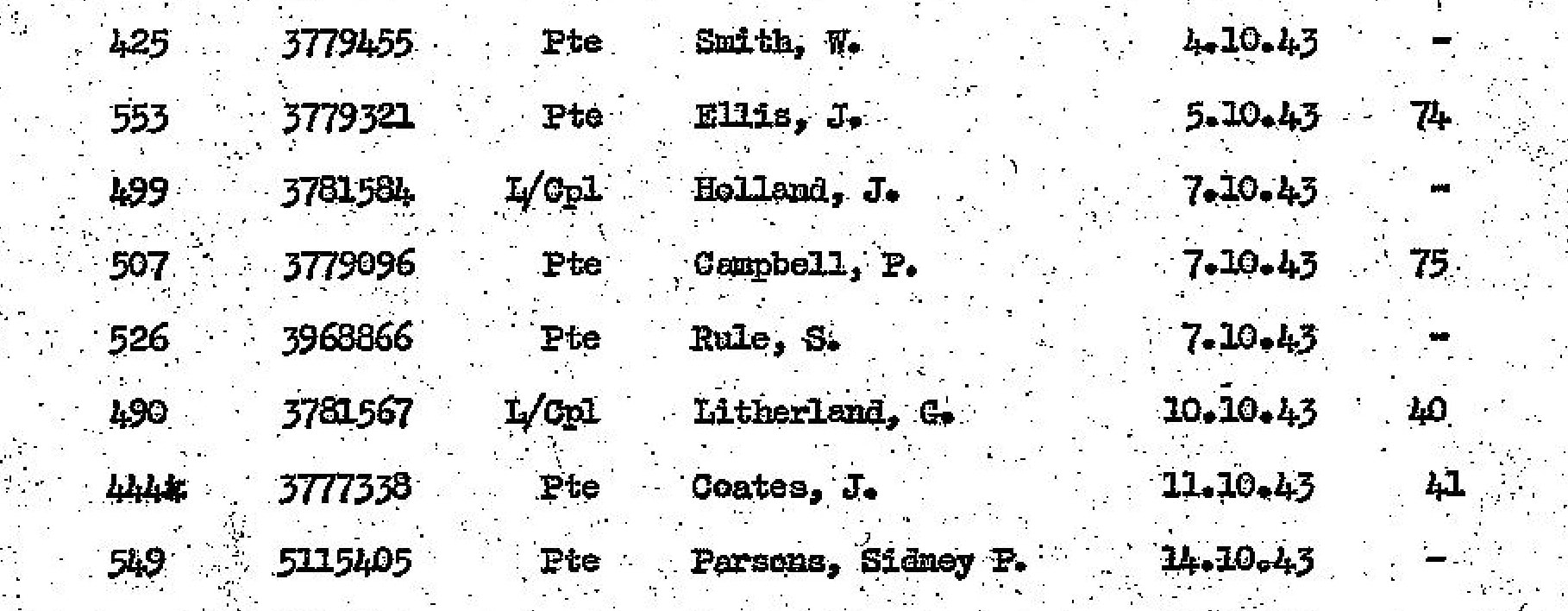

Stanley Herbert Rule was the son of Herbert John and Blanche Rule and the husband of Kathleen Rule from Cambridge in England. He had started his war service with the Welch Regiment before his transfer to the 13th King's in India. It is possible that he and Pte. Kennett had both served together with the Welch Regiment before their arrival at the Chindit training camp of Saugor and may have been friends.

Stanley Rule was captured at the same time as George Pritchard and was also sent down to Rangoon Jail. He was allocated the POW no. 526 and survived just a few short months longer than Pritchard, eventually perishing in Block 6 of the prison on the 7th October 1943. He too was buried in the first instance at the English Cantonment Cemetery (grave no. 75), before being moved across to Rangoon War Cemetery after the war.

CWGC details for Stanley Herbert Rule: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2261163/stanley-herbert-rule/

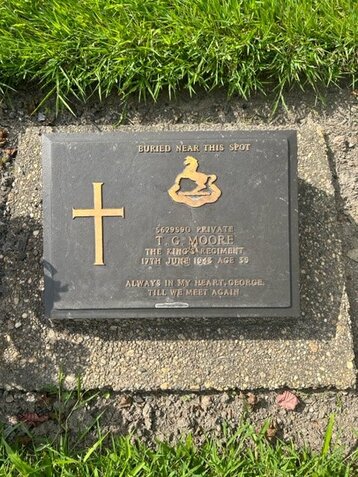

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including Pte. Kennett's witness statement and a photograph of George Pritchard's grave plaque at Rangoon War Cemetery. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

We know from prisoner of war records that he was captured the very same day and was taken eventually to Rangoon Central Jail, where he sadly perished in Block 6 of the prison on the 22nd June. He had been allocated the POW no. 423 at Rangoon and was originally buried at the English Cantonment Cemetery (grave no. 58) in the eastern sector of the city near the Royal Lakes. After the war, all burials from the Cantonment Cemetery were moved over to Rangoon War Cemetery and this is where George lies today. George Pritchard is also remembered in the Birmingham Book of Remembrance for WW2. The photograph seen left, is taken from the Prisoner of War newspaper and was kindly sent to me by WW2 researcher, Tony Honeyman.

CWGC details for George Pritchard: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2261097/george-pritchard/

Stanley Herbert Rule was the son of Herbert John and Blanche Rule and the husband of Kathleen Rule from Cambridge in England. He had started his war service with the Welch Regiment before his transfer to the 13th King's in India. It is possible that he and Pte. Kennett had both served together with the Welch Regiment before their arrival at the Chindit training camp of Saugor and may have been friends.

Stanley Rule was captured at the same time as George Pritchard and was also sent down to Rangoon Jail. He was allocated the POW no. 526 and survived just a few short months longer than Pritchard, eventually perishing in Block 6 of the prison on the 7th October 1943. He too was buried in the first instance at the English Cantonment Cemetery (grave no. 75), before being moved across to Rangoon War Cemetery after the war.

CWGC details for Stanley Herbert Rule: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2261163/stanley-herbert-rule/

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including Pte. Kennett's witness statement and a photograph of George Pritchard's grave plaque at Rangoon War Cemetery. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

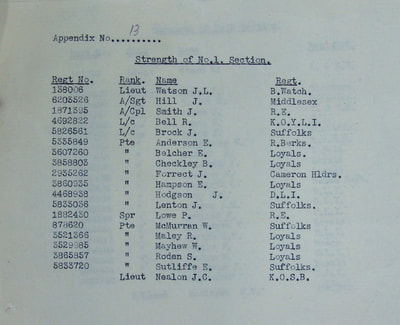

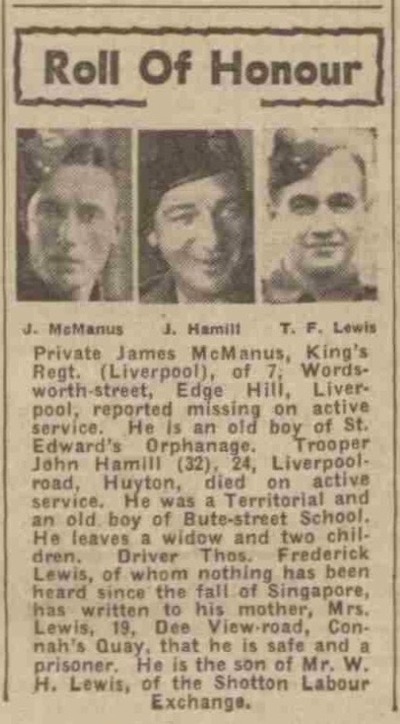

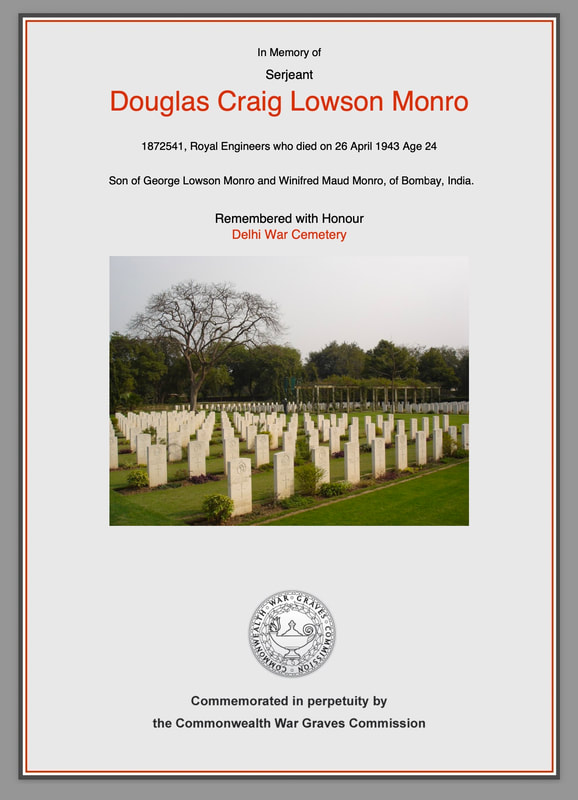

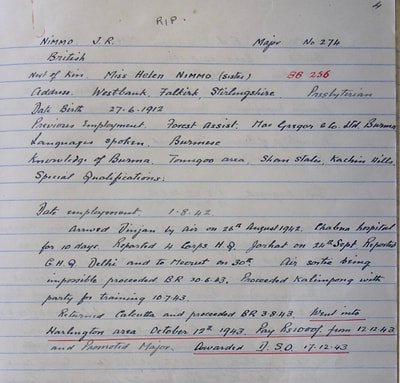

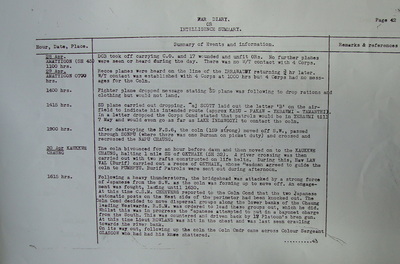

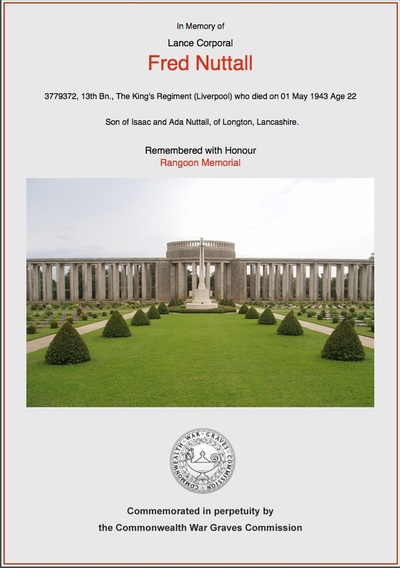

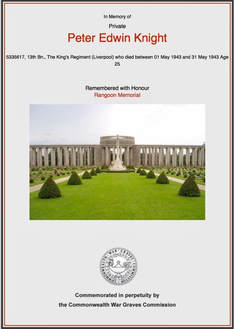

CWGC certificate for Peter Edwin Knight.

CWGC certificate for Peter Edwin Knight.

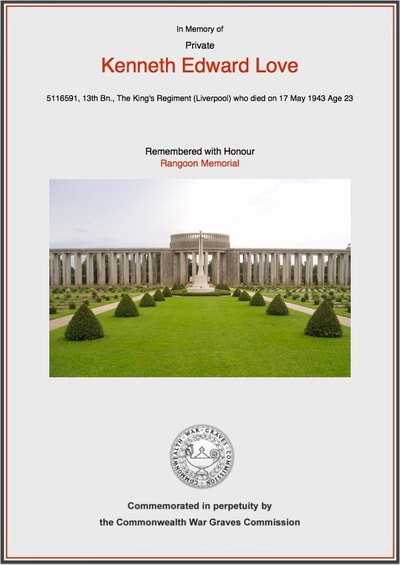

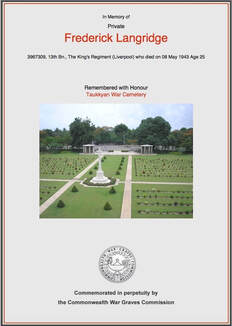

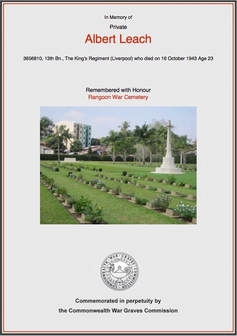

KNIGHT, PETER EDWIN

Rank: Private

Service No: 5335617

Date of Death: 01/05/1943

Age: 25

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial, Taukkyan War Cemetery.

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2514707/knight,-peter-edwin/

Chindit Column: 7

Other details:

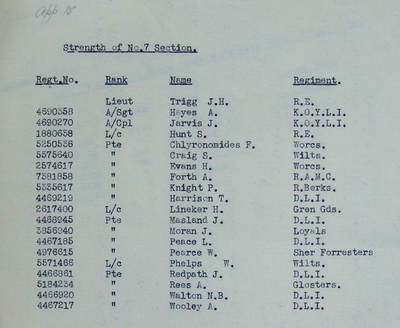

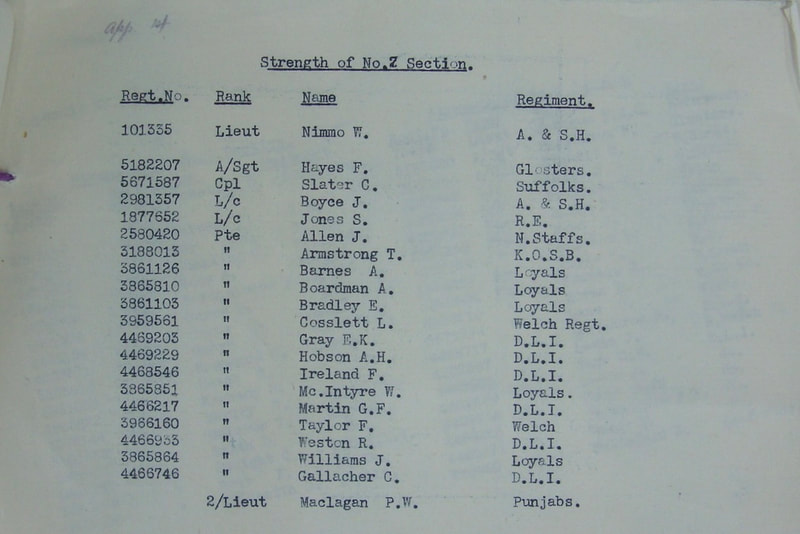

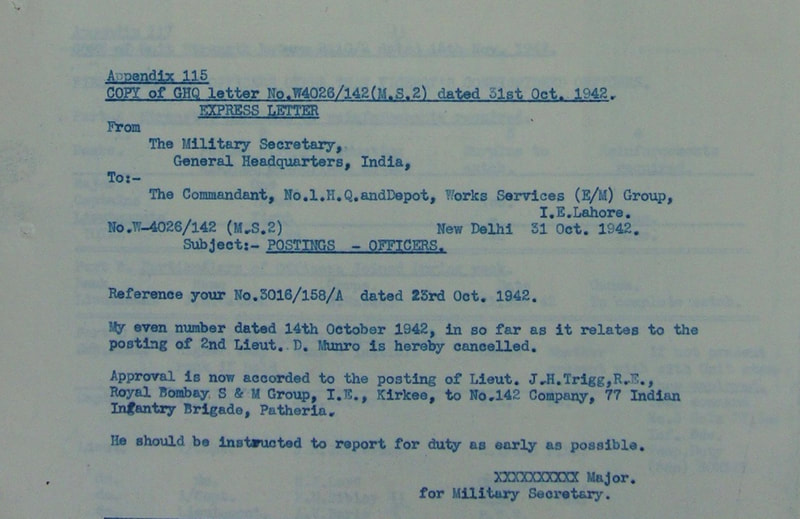

Pte. Peter Edwin Knight originally enlisted into the Royal Berkshire Regiment at the outset of WW2. He was transferred to the 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment in the autumn of 1942 and was posted to the 142 Commando section of the King's based at Saugor in the Central Provinces of India. After safely negotiating commando training, he became part of the commando platoon allocated to No. 7 Column under the command of Lt. John Hubert Trigg of the Royal Engineers.

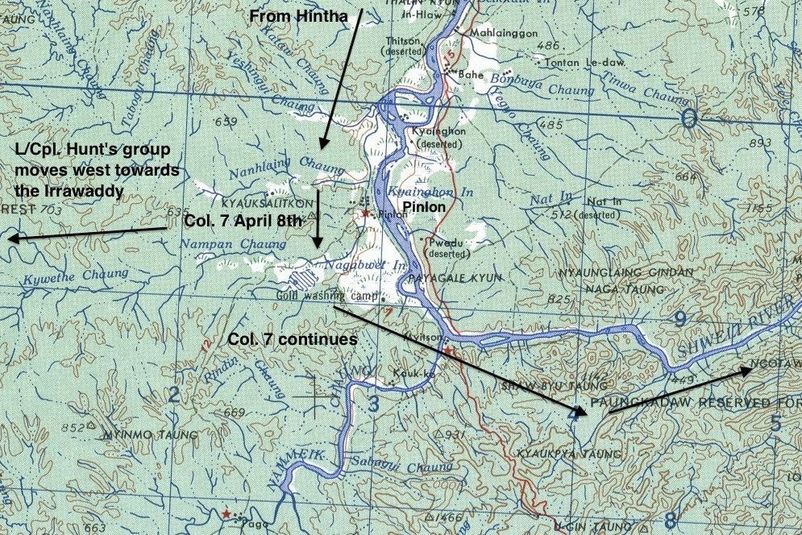

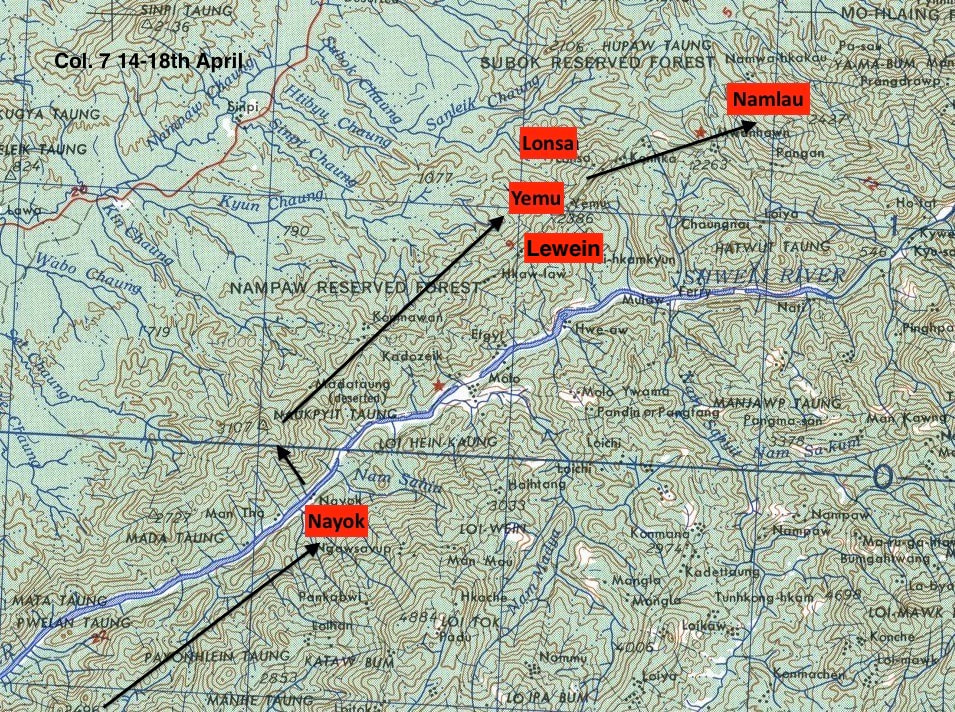

Unlike some of the other commando platoons on the first Chindit expedition, Trigg's men had no definite objective or pre-arranged target. They were used to lay booby-traps at locations judged to be frequented by the enemy and often scouted ahead of the main body of the column. When the order to return to India was given by Brigadier Wingate in late March 1943, Major Gilkes, the commander of 7 Column, ordered Lt. Trigg to lead one of the main dispersal parties. This group was made up of Trigg's commando platoon, plus some members of 5 Column who had become separated from their own unit after a battle with the Japanese at a place called Hintha and had met up with 7 Column at the Shweli River.

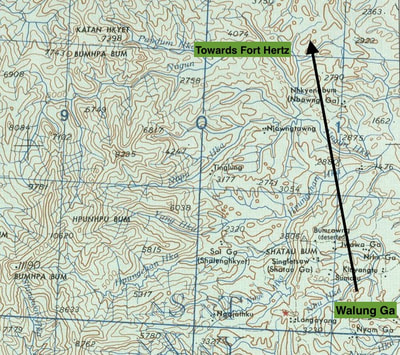

Major Gilkes had always had it in his mind, that if the Chindit Brigade ventured across the Irrawaddy River during the operation in 1943, that he and his column would exit Burma on dispersal via the Kachin Hills and into the Yunnan Province of China. Lt. Trigg and his dispersal party accompanied Gilkes for the vast majority of this journey. Once again, Trigg and his men were asked to blaze a trail and move ahead of the column, often reaching villages and arranging local guides and much needed food supplies for the ailing and exhausted soldiers behind.

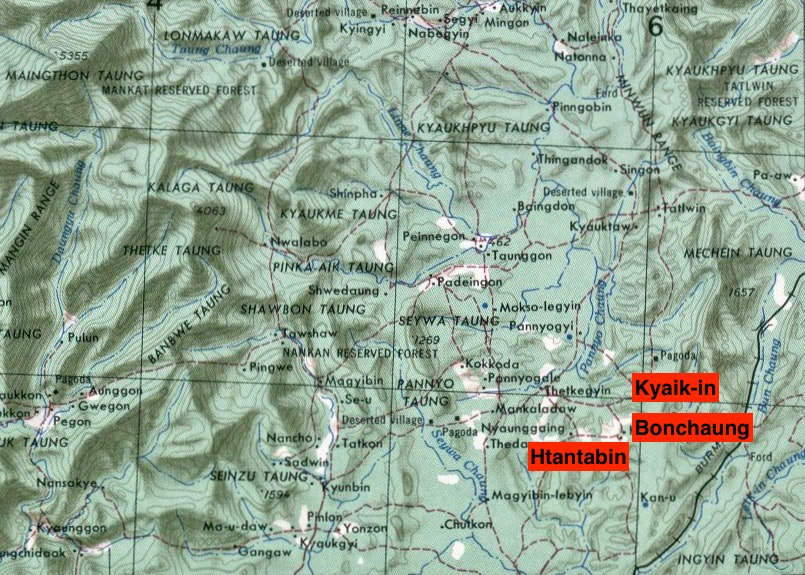

Lt. Trigg was successful in getting the majority of his men out of Burma in 1943, eventually leading his party to safety via Yunnan Province and then having the luxury of being flown back to India in United States Air Force Dakotas on the 7th June. There was however, one incident that took place on the 8th April, which must have played on his mind as he began his well-earned period of rest and recuperation.

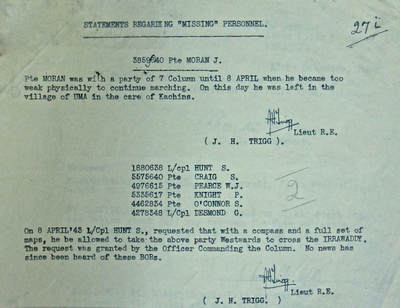

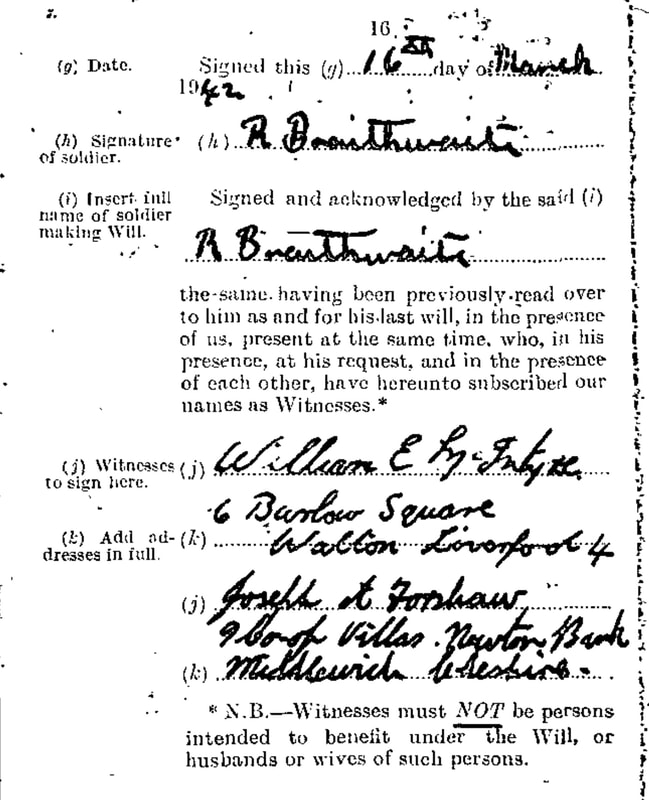

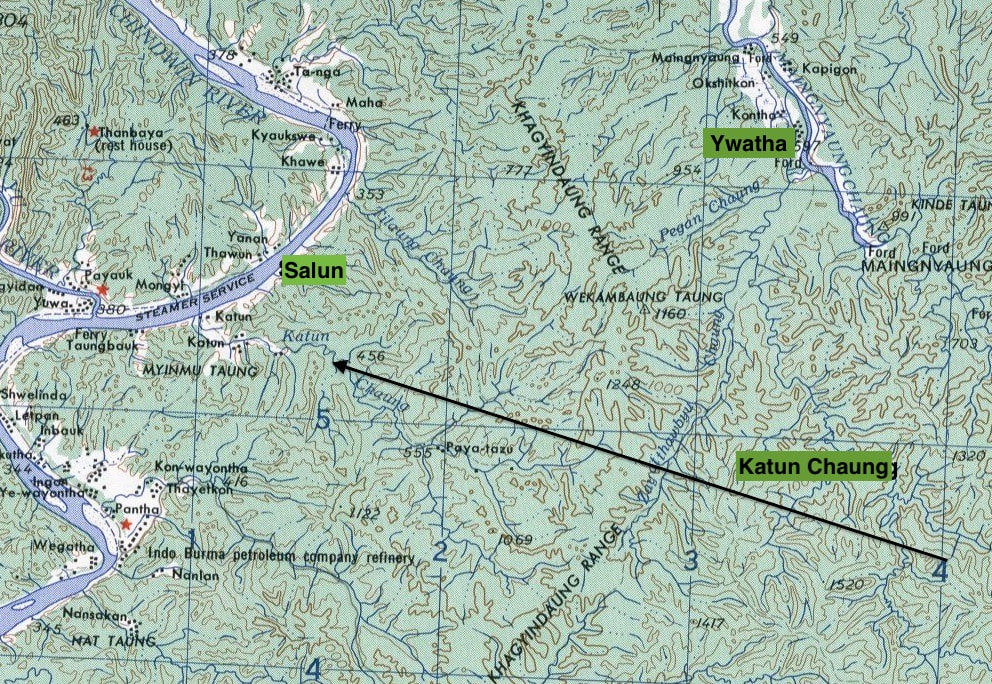

From a witness statement given by Lt. Trigg after Operation Longcloth:

On the 8th April 1943, L/Cpl. S. Hunt requested that with a compass and a full set of maps, he be allowed to take the following men westwards to cross the Irrawaddy. L/Cpl. Desmond (5 Col. Commando), Pte. Samuel Craig (7 Col. Commando), Pte. William Pearce (7 Col. Commando), Pte. Peter Knight (7 Col. Commando) and Pte. Stephen O’Connor (5 Col. Commando). The request was granted by the Officer commanding the Column. No news has since been heard of these British Other Ranks.

The group had all been wounded to one extent or another and were also suffering badly from the monotonous diet of rice. They felt that the longer route out via Yunnan Province was now beyond them and their only hope was to turn west and head back towards the Chindwin. Sadly, none of these six men made it back to India in 1943. All six were captured by the Japanese over the coming days and weeks. Peter Knight died at the temporary POW Camp at Kalaw, Sidney Hunt and William Pearce survived a little longer, but eventually perished inside Rangoon Jail. Only Gerald Desmond, Samuel Craig and Stephen O'Connor survived their ordeal as prisoners of war and were liberated on the 29th April 1945.

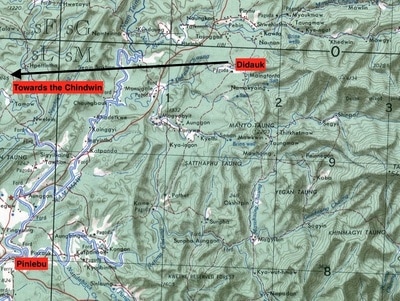

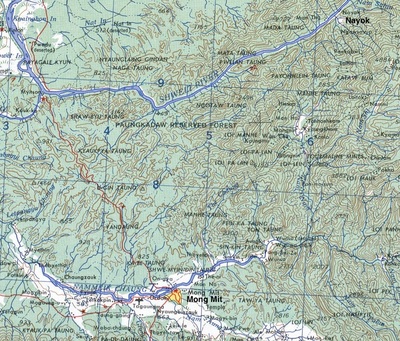

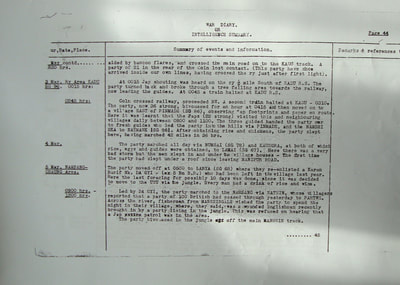

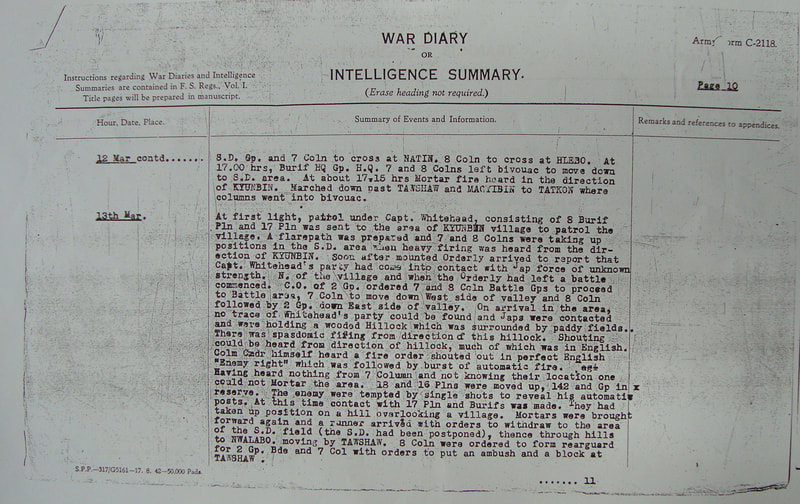

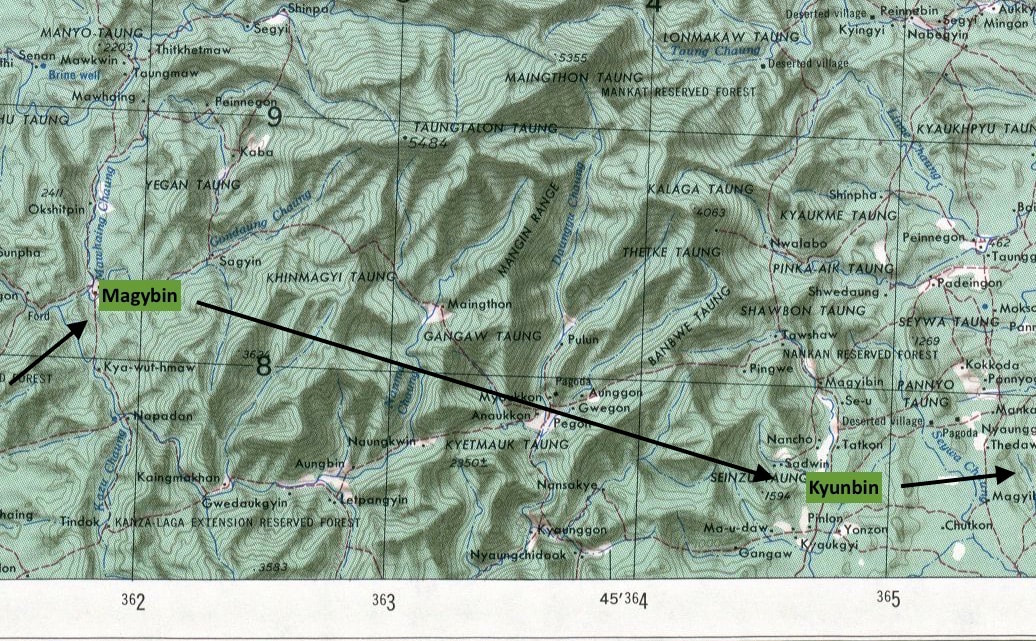

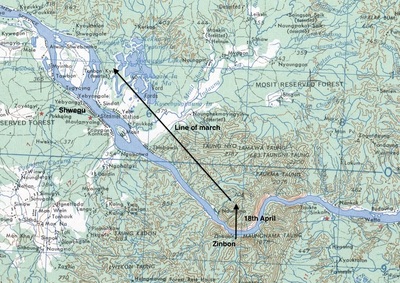

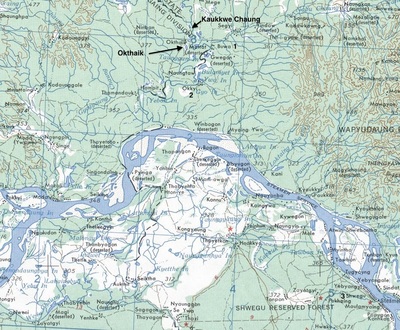

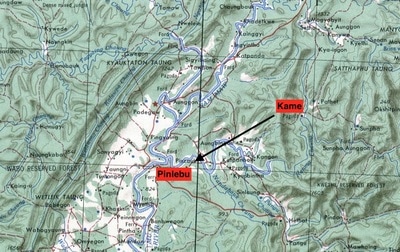

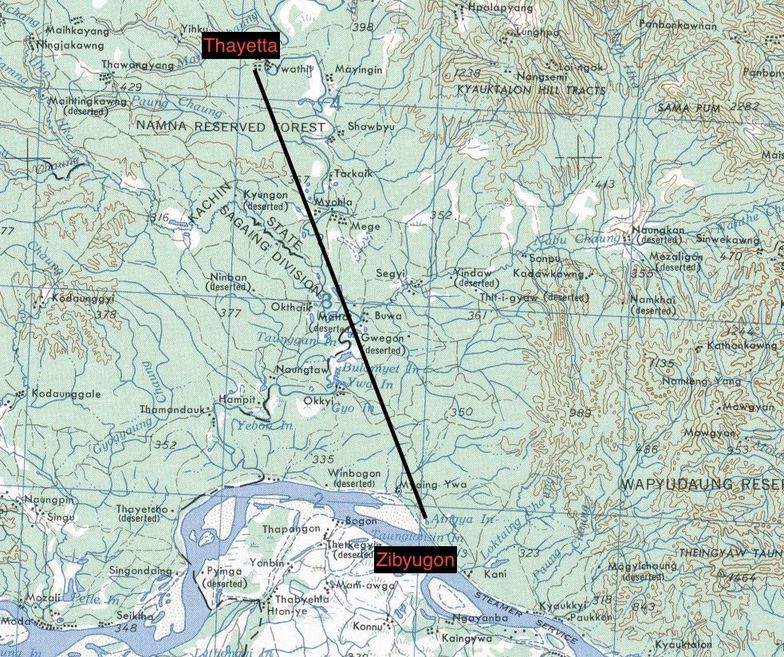

Seen below is a map of the area around the village of Pinlon, located on the western banks of the Shweli River and close to the Nanhlaing Chaung, the scene of L/Cpl. Hunt's request to leave the main body of 7 Column and move west towards the Irrawaddy.

Rank: Private

Service No: 5335617

Date of Death: 01/05/1943

Age: 25

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial, Taukkyan War Cemetery.

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2514707/knight,-peter-edwin/

Chindit Column: 7

Other details:

Pte. Peter Edwin Knight originally enlisted into the Royal Berkshire Regiment at the outset of WW2. He was transferred to the 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment in the autumn of 1942 and was posted to the 142 Commando section of the King's based at Saugor in the Central Provinces of India. After safely negotiating commando training, he became part of the commando platoon allocated to No. 7 Column under the command of Lt. John Hubert Trigg of the Royal Engineers.

Unlike some of the other commando platoons on the first Chindit expedition, Trigg's men had no definite objective or pre-arranged target. They were used to lay booby-traps at locations judged to be frequented by the enemy and often scouted ahead of the main body of the column. When the order to return to India was given by Brigadier Wingate in late March 1943, Major Gilkes, the commander of 7 Column, ordered Lt. Trigg to lead one of the main dispersal parties. This group was made up of Trigg's commando platoon, plus some members of 5 Column who had become separated from their own unit after a battle with the Japanese at a place called Hintha and had met up with 7 Column at the Shweli River.

Major Gilkes had always had it in his mind, that if the Chindit Brigade ventured across the Irrawaddy River during the operation in 1943, that he and his column would exit Burma on dispersal via the Kachin Hills and into the Yunnan Province of China. Lt. Trigg and his dispersal party accompanied Gilkes for the vast majority of this journey. Once again, Trigg and his men were asked to blaze a trail and move ahead of the column, often reaching villages and arranging local guides and much needed food supplies for the ailing and exhausted soldiers behind.

Lt. Trigg was successful in getting the majority of his men out of Burma in 1943, eventually leading his party to safety via Yunnan Province and then having the luxury of being flown back to India in United States Air Force Dakotas on the 7th June. There was however, one incident that took place on the 8th April, which must have played on his mind as he began his well-earned period of rest and recuperation.

From a witness statement given by Lt. Trigg after Operation Longcloth:

On the 8th April 1943, L/Cpl. S. Hunt requested that with a compass and a full set of maps, he be allowed to take the following men westwards to cross the Irrawaddy. L/Cpl. Desmond (5 Col. Commando), Pte. Samuel Craig (7 Col. Commando), Pte. William Pearce (7 Col. Commando), Pte. Peter Knight (7 Col. Commando) and Pte. Stephen O’Connor (5 Col. Commando). The request was granted by the Officer commanding the Column. No news has since been heard of these British Other Ranks.

The group had all been wounded to one extent or another and were also suffering badly from the monotonous diet of rice. They felt that the longer route out via Yunnan Province was now beyond them and their only hope was to turn west and head back towards the Chindwin. Sadly, none of these six men made it back to India in 1943. All six were captured by the Japanese over the coming days and weeks. Peter Knight died at the temporary POW Camp at Kalaw, Sidney Hunt and William Pearce survived a little longer, but eventually perished inside Rangoon Jail. Only Gerald Desmond, Samuel Craig and Stephen O'Connor survived their ordeal as prisoners of war and were liberated on the 29th April 1945.

Seen below is a map of the area around the village of Pinlon, located on the western banks of the Shweli River and close to the Nanhlaing Chaung, the scene of L/Cpl. Hunt's request to leave the main body of 7 Column and move west towards the Irrawaddy.

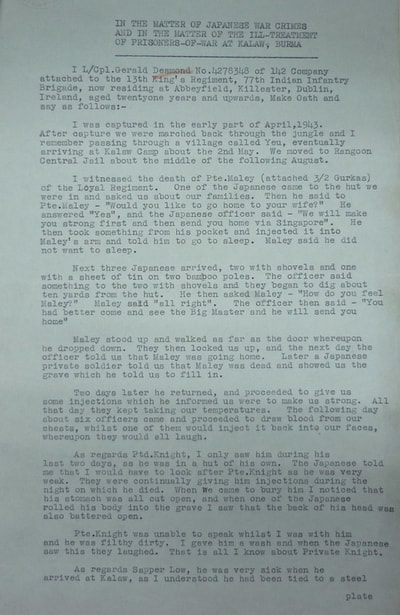

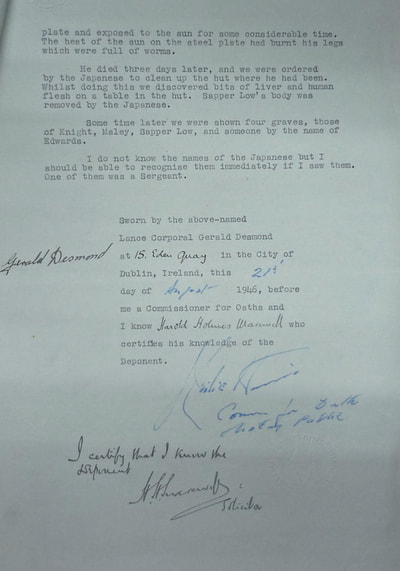

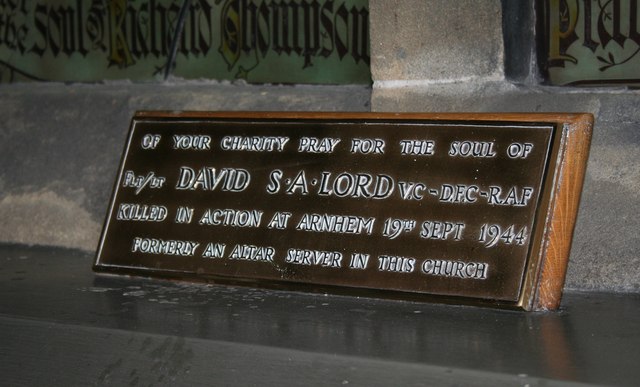

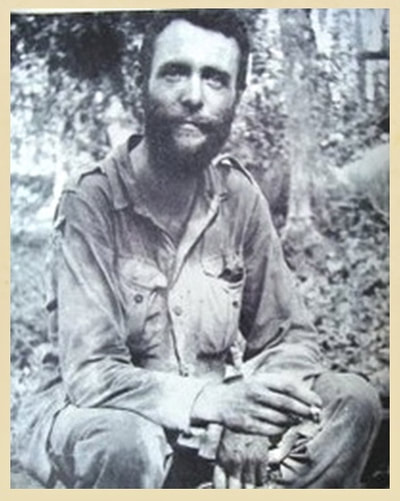

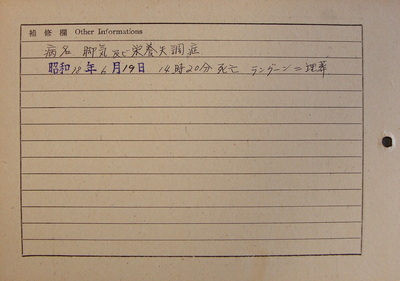

The family of Peter Knight, known to his Chindit comrades as Rocky, had to wait until after the war was over before they learned of his fate in Burma whilst in the hands of the Japanese. It was from a witness statement given by fellow commando Gerald Desmond in August 1946, that awful truth became known.

While in the Kalaw Camp, Gerald witnessed the Japanese conduct horrendous atrocities upon several POW’s, including medical experiments on both himself and his fellow prisoners. The Japanese administered injections to all the prisoners during their time at Kalaw; these injections were most likely different strains of malaria and dengue fever which they were testing. Gerald told his son, that they would stab him in the chest with the needle when giving the injection and when taking blood samples they would squirt some blood in his face from the syringe, which the Japanese found very amusing.

In relation to Rocky Knight, Gerald Desmond remembered:

As regards Pte. Knight, I only saw him during his last two days, as he was in a hut of his own. The Japanese told me I would have to look after Pte. Knight as he was very weak. They were continually giving him injections during the night on which he died. When we came to bury him I noticed that his stomach was all cut open, and when one of the Japanese rolled his body into the grave I saw that the back of his head was also battered open.

On rare occasions back home in Ireland, Gerald Desmond would recount how he had done everything he could to care for Pte. Knight during his last few days of life and also mentioned that similar experiments were probably taken out on Lance Corporal Sidney Hunt, who died a few months later in Rangoon Jail. To read more about Gerald Desmond and his time on Operation Longcloth and as a prisoner or war, please click on the following link: Lance Corporal Gerald Desmond

After the war, the Army Graves Registration Unit could not locate the remains of any of the Chindit POW's held at Kalaw, and for this reason Pte. Peter Edwin Knight is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial, alongside all the other casualties from the Burma campaign that have no known grave. Seen in the gallery below are some more images in relation this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

While in the Kalaw Camp, Gerald witnessed the Japanese conduct horrendous atrocities upon several POW’s, including medical experiments on both himself and his fellow prisoners. The Japanese administered injections to all the prisoners during their time at Kalaw; these injections were most likely different strains of malaria and dengue fever which they were testing. Gerald told his son, that they would stab him in the chest with the needle when giving the injection and when taking blood samples they would squirt some blood in his face from the syringe, which the Japanese found very amusing.

In relation to Rocky Knight, Gerald Desmond remembered:

As regards Pte. Knight, I only saw him during his last two days, as he was in a hut of his own. The Japanese told me I would have to look after Pte. Knight as he was very weak. They were continually giving him injections during the night on which he died. When we came to bury him I noticed that his stomach was all cut open, and when one of the Japanese rolled his body into the grave I saw that the back of his head was also battered open.

On rare occasions back home in Ireland, Gerald Desmond would recount how he had done everything he could to care for Pte. Knight during his last few days of life and also mentioned that similar experiments were probably taken out on Lance Corporal Sidney Hunt, who died a few months later in Rangoon Jail. To read more about Gerald Desmond and his time on Operation Longcloth and as a prisoner or war, please click on the following link: Lance Corporal Gerald Desmond

After the war, the Army Graves Registration Unit could not locate the remains of any of the Chindit POW's held at Kalaw, and for this reason Pte. Peter Edwin Knight is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial, alongside all the other casualties from the Burma campaign that have no known grave. Seen in the gallery below are some more images in relation this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

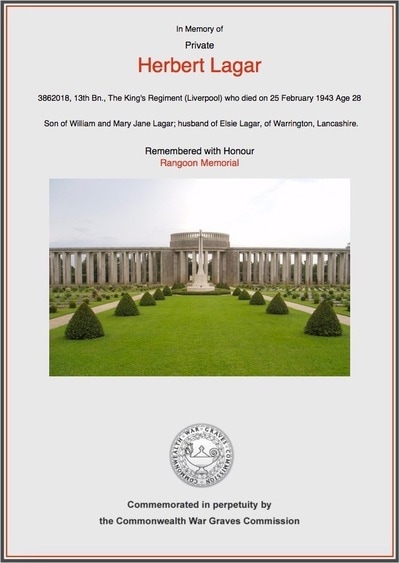

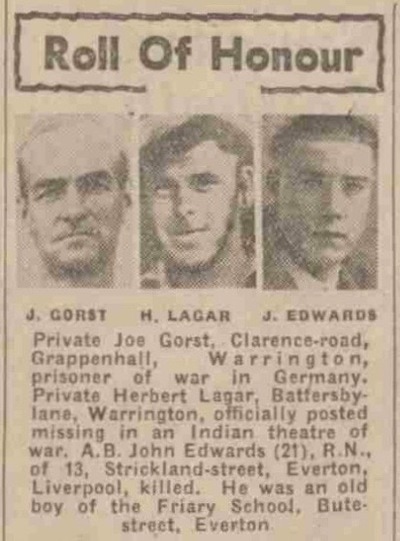

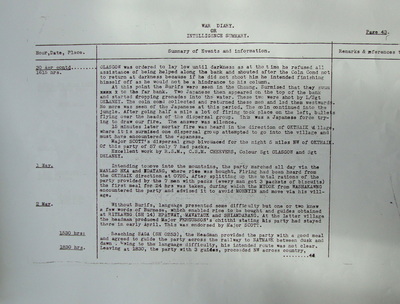

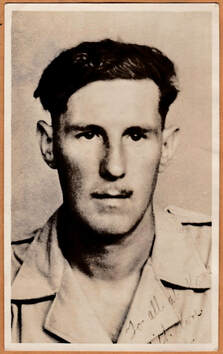

Pte. Herbert Lagar.

Pte. Herbert Lagar.

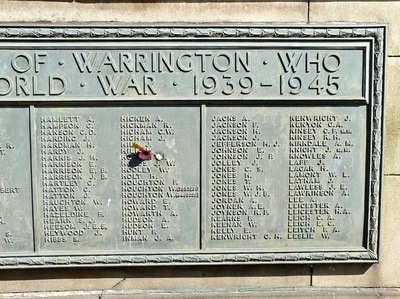

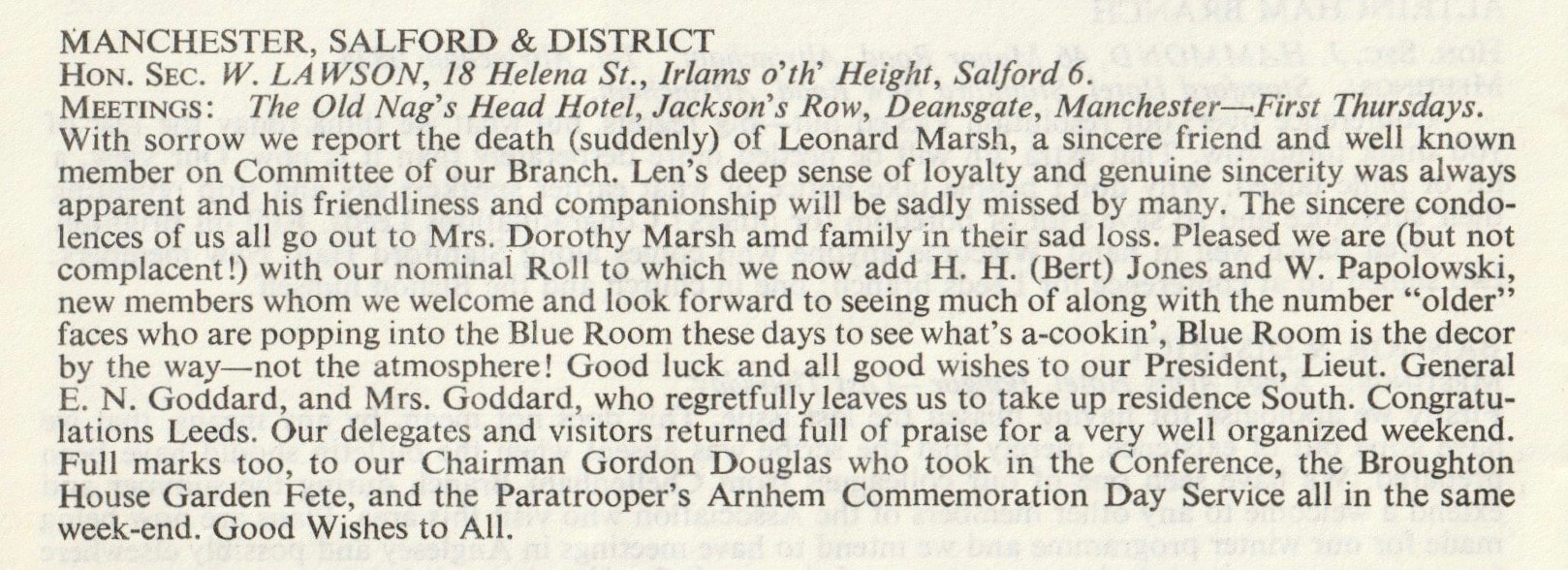

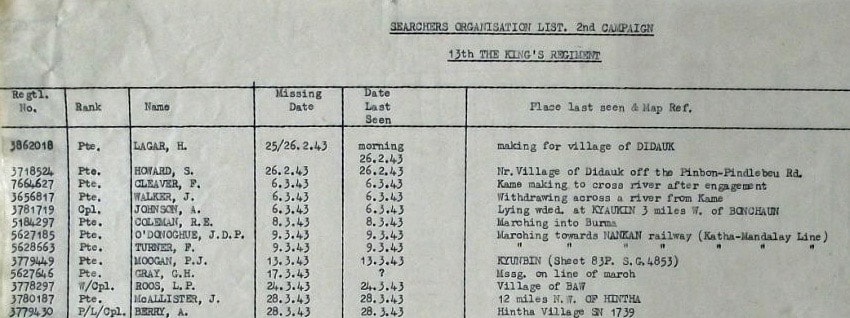

LAGAR, HERBERT

Rank: Private

Service No: 3862018

Date of Death: 25/02/1943

Age: 28

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial, Taukkyan War Cemetery.

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2515387/LAGAR,%20HERBERT

Chindit Column: 7

Other details:

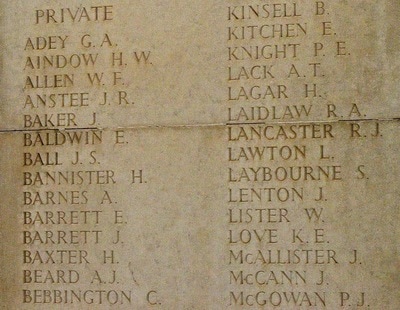

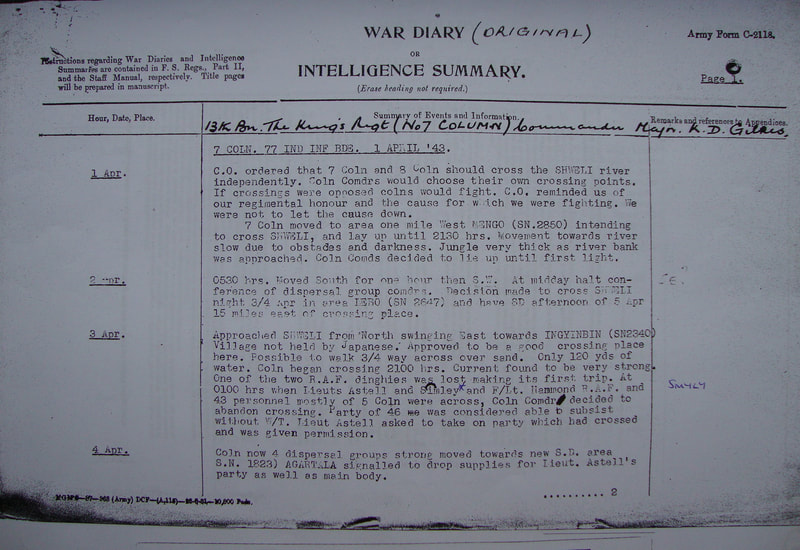

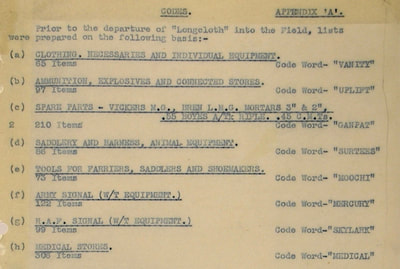

Herbert Lagar was the son of William and Mary Jane Lagar and husband of Elsie Lagar from Battersby Lane in Warrington, Lancashire. Originally a soldier with the Loyal Regiment, Herbert was posted to the King's Regiment and commenced Chindit training at the Saugor Camp on the 30th September 1942. Pte. Lagar was allocated to 7 Column under the command of Major Kenneth Gilkes and anecdotal evidence suggests that he became the column Bugler.

Herbert Lagar became one of the very first casualties on Operation Longcloth, when he went missing from his column on the morning of the 25th February 1943. Around this time, 7 Column along with Wingate's Brigade HQ were preparing to push deeper into Burma after taking a large supply dropping at a village called Tonmakeng on the 24th February. According to one set of the official missing in action listings for 77th Brigade, Pte. Lagar was: last seen making for the village of Didauk on the morning of the 25th February 1943.

Another soldier with 7 Column, Corporal John Kennedy, who had been taken prisoner on Operation Longcloth, gave a one line witness report in relation to Herbert Lagar, after his own liberation from Rangoon Jail in April 1945. He simply stated that: Herbert Lagar, fell out from the line of march in late February 1943.

Perhaps the most conclusive evidence regarding the fate of Herbert Lagar, came from another returning POW, Pte. Thomas Worthington. In a letter addressed to the Army Investigation Bureau dated November 1945, he stated that:

Pte. Lagar was the bugler with No. 7 Column. His home was in Lancashire and he had been a boy soldier with the Loyal Regiment. He was sent out on an errand during the march along the Pinlebu Road early in the campaign and did not return.

Sadly, we will probably never know what actually happened to Herbert on the 25th February 1943, it seems likely that he became lost in the first instance and may have been wandering alone for a time before either being taken prisoner, or killed trying to evade the same fate. Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. To read more from the letter written by Thomas Worthington, please click on the following link: Tom Worthington's Letter

Rank: Private

Service No: 3862018

Date of Death: 25/02/1943

Age: 28

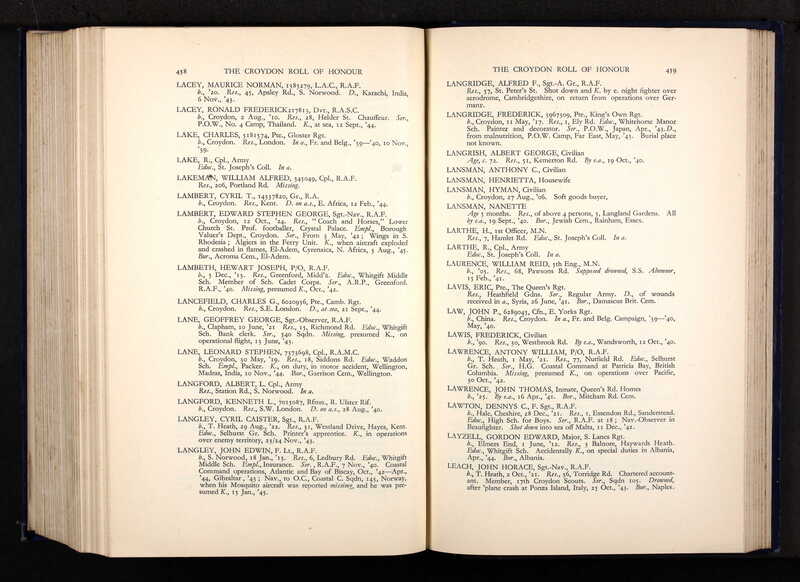

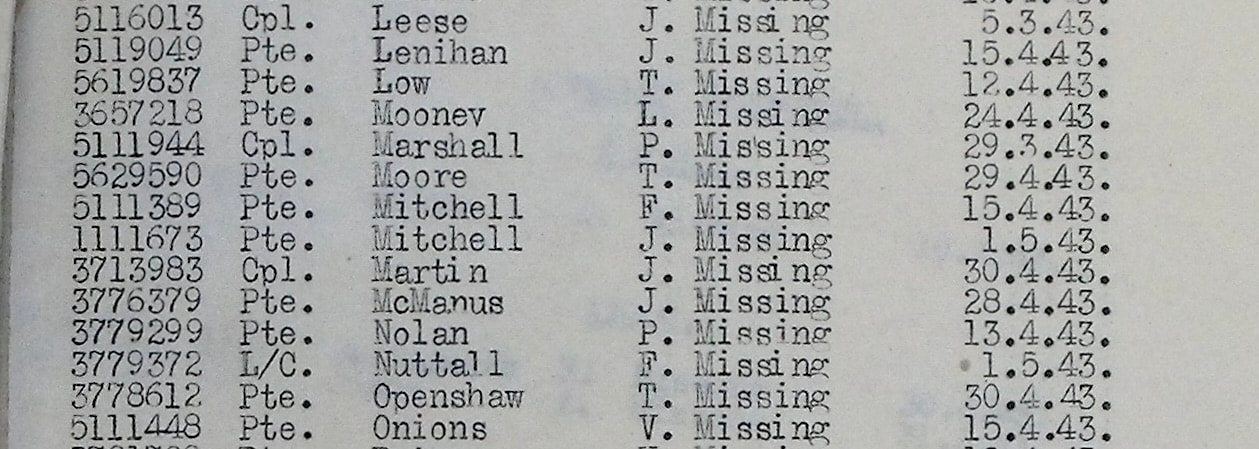

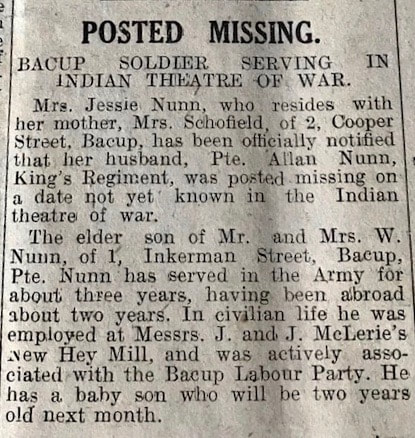

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.