Captain Robert McCrea MBE

Robert McCrea was commissioned into the Royal Army Veterinary Corps as a Lieutenant on the 24th of November 1942. His lifetime love and understanding of animals had meant this was a natural choice of service for the young officer in World War 2.

I had anecdotal evidence of his possible participation on Longcloth in the form my conversations with Denis Gudgeon, a former Gurkha Rifle officer in column three, and heavily involved with the animal transport of that unit in 1943. He had often mentioned his friend Roy MacKenzie the ATO (Animal Transport Officer) of column three and I think it was during this time that he listed several other men, all related in some way to mules or veterinary training. Robert McCrea was one of these men.

Denis certainly did mention the chief veterinary officer in their final training area of Jhansi in 1942, that being Colonel Stewart of the Royal Army Veterinary Corps. Stewart had been involved in the technique of 'de-braying' mules for use behind enemy lines, which of course was of great interest to Wingate as he prepared for his first expedition into Burma. Another important member of the Chindit veterinary team was Captain Carey-Foster, who was the leading equestrian expert on the operation and would have been involved with training the young ATO's and vets in 1942.

My recollection of these conversations had placed Robert with No. 2 Column on Operation Longcloth and therefore serving with Gurkha Riflemen as his muleteers in that unit. Late on in 2011 a post was placed onto the Burma Star forum by Robert's daughter Anne, and we have shared correspondence since then that has allowed me to build this story about her father's participation in 1943 and his continued service in WW2.

I had anecdotal evidence of his possible participation on Longcloth in the form my conversations with Denis Gudgeon, a former Gurkha Rifle officer in column three, and heavily involved with the animal transport of that unit in 1943. He had often mentioned his friend Roy MacKenzie the ATO (Animal Transport Officer) of column three and I think it was during this time that he listed several other men, all related in some way to mules or veterinary training. Robert McCrea was one of these men.

Denis certainly did mention the chief veterinary officer in their final training area of Jhansi in 1942, that being Colonel Stewart of the Royal Army Veterinary Corps. Stewart had been involved in the technique of 'de-braying' mules for use behind enemy lines, which of course was of great interest to Wingate as he prepared for his first expedition into Burma. Another important member of the Chindit veterinary team was Captain Carey-Foster, who was the leading equestrian expert on the operation and would have been involved with training the young ATO's and vets in 1942.

My recollection of these conversations had placed Robert with No. 2 Column on Operation Longcloth and therefore serving with Gurkha Riflemen as his muleteers in that unit. Late on in 2011 a post was placed onto the Burma Star forum by Robert's daughter Anne, and we have shared correspondence since then that has allowed me to build this story about her father's participation in 1943 and his continued service in WW2.

As a member of 2 Column in 1943 Robert would have found himself part of Wingate's decoy group, with the express orders to make themselves known in the local area and to openly march along the village tracks and pathways.

The plan here was to fool the Japanese about the operations intentions, numbers and the objectives. The ultimate aim of Columns 1 and 2 (Southern Group) was to make for the rail station at Kyaikthin, destroy the rail tracks in that location and then turn northeast toward the Irrawaddy River and attempt to rejoin the main section at an agreed rendezvous point.

No. 2 Column never made this rendezvous and was ambushed at Kyaikthin by a large force of Japanese on the 2nd March. In the confusion the dispersal drill was misunderstood by the column and some men went forward as previously agreed, but the majority of the unit was either destroyed or headed back west to the safety of India.

The column commander Major Arthur Emmett was part of the group which decided to return home, and as most of the mules and other animal transport were destroyed at Kyaikthin, my guess would be that Lieutenant McCrea was probably with this party. Major Emmett's actions were heavily criticised by Wingate after the operation was over, especially the decision to march quite literally up the rail tracks when closing in on the village of Kyaikthin. However, given that the columns orders previously had been to make itself known in the local area, I feel this criticism is a little unfair.

The photograph seen to the right is from the family archive of Anne McCrea and shows the close relationship between Chindit and his mule. The bond built up between the muleteers and handlers and their charges was immensely strong, making the loss of any animal very difficult to bear. For No. 2 Column this pain was to manifest itself when their mules were killed or maimed at the Kyaikthin ambush, but for mule handlers in other columns the distress was to come later in operation, when seeing their animals killed in order to feed their starving Chindit comrades.

To read more about No. 2 Column and their experiences at Kyaikthin, please click on the following link:

Lt. MacHorton and the battle of Kyaikthin

The plan here was to fool the Japanese about the operations intentions, numbers and the objectives. The ultimate aim of Columns 1 and 2 (Southern Group) was to make for the rail station at Kyaikthin, destroy the rail tracks in that location and then turn northeast toward the Irrawaddy River and attempt to rejoin the main section at an agreed rendezvous point.

No. 2 Column never made this rendezvous and was ambushed at Kyaikthin by a large force of Japanese on the 2nd March. In the confusion the dispersal drill was misunderstood by the column and some men went forward as previously agreed, but the majority of the unit was either destroyed or headed back west to the safety of India.

The column commander Major Arthur Emmett was part of the group which decided to return home, and as most of the mules and other animal transport were destroyed at Kyaikthin, my guess would be that Lieutenant McCrea was probably with this party. Major Emmett's actions were heavily criticised by Wingate after the operation was over, especially the decision to march quite literally up the rail tracks when closing in on the village of Kyaikthin. However, given that the columns orders previously had been to make itself known in the local area, I feel this criticism is a little unfair.

The photograph seen to the right is from the family archive of Anne McCrea and shows the close relationship between Chindit and his mule. The bond built up between the muleteers and handlers and their charges was immensely strong, making the loss of any animal very difficult to bear. For No. 2 Column this pain was to manifest itself when their mules were killed or maimed at the Kyaikthin ambush, but for mule handlers in other columns the distress was to come later in operation, when seeing their animals killed in order to feed their starving Chindit comrades.

To read more about No. 2 Column and their experiences at Kyaikthin, please click on the following link:

Lt. MacHorton and the battle of Kyaikthin

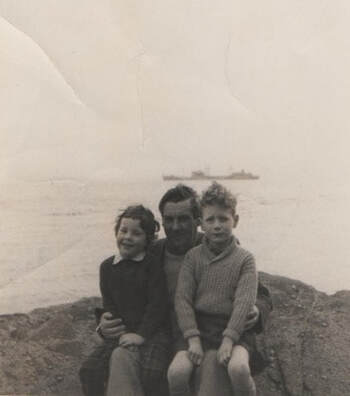

As mentioned earlier, I have been in contact with Captain McCrea's daughter Anne. She has kindly written a short biography about her father and his time in India and Burma. Anne has also given me permission to use some of the wonderful photographs which help to illustrate her father's story. Seen pictured left is Anne, her father and her older brother Ian, on holiday in Donegal. I have taken the liberty of including this particular photograph, simply because it emphasizes the strong family theme which is central to this website.

Here is Anne's contribution:

Captain Robert McCrea 1916-1976

Robert McCrea was the eldest child of a family of three. He grew up on the family farm in a townland near Bready, Strabane, Northern Ireland, receiving his secondary education at Foyle College Londonderry, where he was a keen rugby player.

It was decided that his brother John should farm and that he would study Veterinary at the Royal Dick, Edinburgh (the Royal School of Veterinary Studies, named after it’s founder William Dick). He was enrolled as a student there from 1934-1939.

Many of the stories about my father and the war come from my mother and she relates that as soon as war was declared he immediately decided to join up. It is also said that during his time in the Army, the only news his mother had of him was an official postcard, each time with the few words, “Your son is well.”

My father served in India and Burma with the Chindits - that much we know for certain, although there are stories, reliable or not, of him being in Italy, Africa and Egypt. More certain is the fact that he became unwell with various illnesses: dysentery, smallpox (he had pock marked skin) and malaria. The story goes that when ill with malaria he was taken up into the cool of the hills and looked after by a native woman, but was not expected to live. Again my mother told the story that in the case of malaria he cured himself with the drugs used to treat the animals.

One of his chief jobs whilst in Burma was to devoice mules, which were used behind enemy lines. He was in the Royal Army Veterinary Corps. Thanks to Steve we have been able to find his location and Company in 1943 as Column 2 on Operation Longcloth. In 1944 he was with the 23rd Division Infantry Division HQ at Imphal and Kohima.

After the war my father returned to Ireland, set up practice in Strabane, got married and he and my mother had two children, myself and my older brother Ian. In the early days he still played rugby and had a horse named Sam. As children we were surrounded by animals and were encouraged to ride and always to get back up on the pony after a fall. He had quite a few young assistants, mentoring them on their way to a career in veterinary. In the mid-seventies he joined with two other vets in Strabane to form a Group Practice.

As a father I remember him as being always busy, but taking the time to introduce me to life’s mysteries and often by doing rather than talking. Sadly he died in 1976 after a battle with cancer, but I look back on a life so filled and so eventful, with awe, respect and of course love.

Anne had previously placed a short account of her father's war time experiences on the BBC's 'WW2 People's War' archive:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/15/a4241215.shtml

Copyright © for both these family accounts remains with the author, Anne McCrea.

Here is Anne's contribution:

Captain Robert McCrea 1916-1976

Robert McCrea was the eldest child of a family of three. He grew up on the family farm in a townland near Bready, Strabane, Northern Ireland, receiving his secondary education at Foyle College Londonderry, where he was a keen rugby player.

It was decided that his brother John should farm and that he would study Veterinary at the Royal Dick, Edinburgh (the Royal School of Veterinary Studies, named after it’s founder William Dick). He was enrolled as a student there from 1934-1939.

Many of the stories about my father and the war come from my mother and she relates that as soon as war was declared he immediately decided to join up. It is also said that during his time in the Army, the only news his mother had of him was an official postcard, each time with the few words, “Your son is well.”

My father served in India and Burma with the Chindits - that much we know for certain, although there are stories, reliable or not, of him being in Italy, Africa and Egypt. More certain is the fact that he became unwell with various illnesses: dysentery, smallpox (he had pock marked skin) and malaria. The story goes that when ill with malaria he was taken up into the cool of the hills and looked after by a native woman, but was not expected to live. Again my mother told the story that in the case of malaria he cured himself with the drugs used to treat the animals.

One of his chief jobs whilst in Burma was to devoice mules, which were used behind enemy lines. He was in the Royal Army Veterinary Corps. Thanks to Steve we have been able to find his location and Company in 1943 as Column 2 on Operation Longcloth. In 1944 he was with the 23rd Division Infantry Division HQ at Imphal and Kohima.

After the war my father returned to Ireland, set up practice in Strabane, got married and he and my mother had two children, myself and my older brother Ian. In the early days he still played rugby and had a horse named Sam. As children we were surrounded by animals and were encouraged to ride and always to get back up on the pony after a fall. He had quite a few young assistants, mentoring them on their way to a career in veterinary. In the mid-seventies he joined with two other vets in Strabane to form a Group Practice.

As a father I remember him as being always busy, but taking the time to introduce me to life’s mysteries and often by doing rather than talking. Sadly he died in 1976 after a battle with cancer, but I look back on a life so filled and so eventful, with awe, respect and of course love.

Anne had previously placed a short account of her father's war time experiences on the BBC's 'WW2 People's War' archive:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/15/a4241215.shtml

Copyright © for both these family accounts remains with the author, Anne McCrea.

The photograph pictured to the right shows Captain McCrea (without hat, furthest left) working on a mule during his service with the RAVC. As mentioned earlier he was involved in the medical practice for 'de-voicing' mules, which would then be used by the Chindit troops in 1944.

There is a very good article written by A.J. Moffett called 'The Silent Chindit Mules'. This describes how the medical technique for de-braying mules was perfected and who primarily was responsible for the early stages of testing this operation. The BMJ (British Medical Journal) would not allow me to reproduce the article here on these pages, which of course is their prerogative, so, here is the link to the article as I first found it:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1550202/pdf/bmjcred00586-0046.pdf

In 1944 Robert became part of 23rd British Infantry Brigade, which was earmarked by Wingate for duties in the second Chindit campaign code named Operation Thursday. As part of No. 32 Column, which comprised of the Brigade Head Quarters, Robert was to keep the crucial mule transport in good order during the miles of arduous marching and counter marching over very difficult terrain. The original plan was for 23rd Brigade to be involved in cutting the supply lines of the Japanese 31st Division as it prepared for the invasion of India. In the end the unit commanded by Brigadier L.E. Perowne was removed from Chindit duties by General Slim and kept in reserve for potential use against the enemy in Assam. The Brigade was eventually used in the Imphal and Kohima areas to harass and disrupt the Japanese rear supply lines.

Perowne recounted: For nearly four months the Brigade was in almost continuous action against both the enemy and nature, it enjoyed neither rest nor relief. In that time it has contributed to the major defeat of the Japanese Army, by killing or taking prisoner nearly 1000 of their number.

There is a very good article written by A.J. Moffett called 'The Silent Chindit Mules'. This describes how the medical technique for de-braying mules was perfected and who primarily was responsible for the early stages of testing this operation. The BMJ (British Medical Journal) would not allow me to reproduce the article here on these pages, which of course is their prerogative, so, here is the link to the article as I first found it:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1550202/pdf/bmjcred00586-0046.pdf

In 1944 Robert became part of 23rd British Infantry Brigade, which was earmarked by Wingate for duties in the second Chindit campaign code named Operation Thursday. As part of No. 32 Column, which comprised of the Brigade Head Quarters, Robert was to keep the crucial mule transport in good order during the miles of arduous marching and counter marching over very difficult terrain. The original plan was for 23rd Brigade to be involved in cutting the supply lines of the Japanese 31st Division as it prepared for the invasion of India. In the end the unit commanded by Brigadier L.E. Perowne was removed from Chindit duties by General Slim and kept in reserve for potential use against the enemy in Assam. The Brigade was eventually used in the Imphal and Kohima areas to harass and disrupt the Japanese rear supply lines.

Perowne recounted: For nearly four months the Brigade was in almost continuous action against both the enemy and nature, it enjoyed neither rest nor relief. In that time it has contributed to the major defeat of the Japanese Army, by killing or taking prisoner nearly 1000 of their number.

In recognition of Captain McCrea's contribution to this victory, Brigadier Perowne (pictured left) recommended him be Mentioned in Despatches on 26th April 1945, however, on consideration the award was superseded a few weeks later and upgraded to an MBE. Here is a transcription of the recommendation for the award:

252799 T/Captain Robert McCrea RAVC.

As Brigade Veterinary Officer he has displayed a ceaseless and untiring devotion to duty throughout the difficult period of converting to Animal Transport a formation previously mechanised. His determination and enthusiasm have been an inspiration to all, and the very high standard of animal management prevailing throughout the Brigade, and which now enables the Columns successfully to operate in an almost trackless mountainous country, is due no less to his unfailing cheerfulness than to his exceptionally skillful guidance of personnel who, a few months ago, had little or no experience of animals.

Recommended by Brigadier L.E.C.M. Perowne, Commander 23rd British Infantry Brigade and countersigned by Major-General W.D.A. Lentaigne, Commander Special Force.

Robert eventually left the Army with the rank of Honorary Major and returned home to Ireland to set up his own veterinary practice in Strabane.

My great thanks must go to Anne McCrea for all the help she has given me in compiling this short account of her father's time as a Chindit in WW2. The final photograph shown below is of a group of muleteers and their charges about to attempt a crossing of the great Irrawaddy River in 1943. Which column is depicted here I'm afraid I do not know.

252799 T/Captain Robert McCrea RAVC.

As Brigade Veterinary Officer he has displayed a ceaseless and untiring devotion to duty throughout the difficult period of converting to Animal Transport a formation previously mechanised. His determination and enthusiasm have been an inspiration to all, and the very high standard of animal management prevailing throughout the Brigade, and which now enables the Columns successfully to operate in an almost trackless mountainous country, is due no less to his unfailing cheerfulness than to his exceptionally skillful guidance of personnel who, a few months ago, had little or no experience of animals.

Recommended by Brigadier L.E.C.M. Perowne, Commander 23rd British Infantry Brigade and countersigned by Major-General W.D.A. Lentaigne, Commander Special Force.

Robert eventually left the Army with the rank of Honorary Major and returned home to Ireland to set up his own veterinary practice in Strabane.

My great thanks must go to Anne McCrea for all the help she has given me in compiling this short account of her father's time as a Chindit in WW2. The final photograph shown below is of a group of muleteers and their charges about to attempt a crossing of the great Irrawaddy River in 1943. Which column is depicted here I'm afraid I do not know.

Update 06/03/2021.

From the Daily Telegraph obituary (30th November 2002) of Major Douglas Witherington, Royal Army Veterinary Corps:

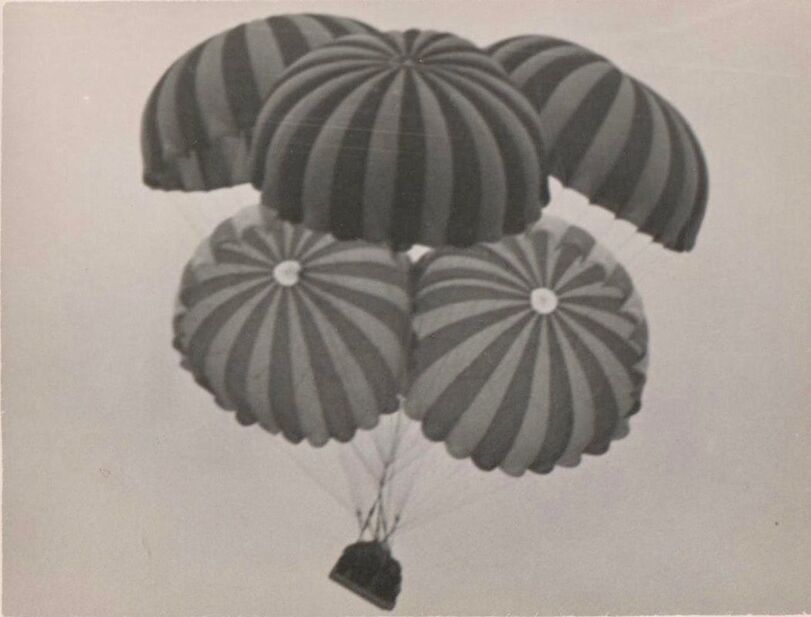

Douglas Witherington, who has died aged 82, played an important role in devising a humane way of parachuting mules to the Chindits behind Japanese lines in Burma. The Americans had conducted experiments earlier in the Second World War by attaching parachutes to the animals, then pushing them out of an aircraft. Unfortunately, the first six beasts were fatally injured when the jerk of the opening parachute ruptured the mesentery artery, which feeds blood to the intestines. The remaining mules wisely resisted all efforts to make them follow.

Major Witherington and Lt-Colonel Ken Barlow, Royal Army Veterinary Corps, felt they could do better. They adapted a small inflatable assault dinghy, measuring 6.5 ft by 4 ft, into which a mule, heavily sedated with chloral-hydrate could be placed, with special padding to protect its private parts. Inside the plane a launching track was made, to ensure the smooth departure of the mule in its "raft" supported with six parachutes, which then floated down from about 600 ft. In the course of six experimental drops, they had one fatality, when a mule became caught up in a cluster of parachutes at the tail of the aircraft, broke free and made a precipitate descent, with the result that it sustained a spinal fracture and had to be destroyed in the dropping zone. The other five experiments, however, were successful. When the animals had their straps released after landing they got up showing some signs of sweating and stiffness, but no real distress and they were ready to carry heavy wireless equipment, ammunition and other weapons such as mortars and flame throwers.

On the first Chindit expedition behind Japanese lines in 1943, their mules had alerted the enemy to their positions by braying; so, when Witherington volunteered for the second expedition as part of 14 Brigade, he was given the task of muting the Brigade's beasts by removing their vocal cords under general anaesthetic.

In the field the Japanese recognised that mules were more important targets than men, since they carried the radio equipment on which operations depended for instructions. They proved more resilient than ponies and were indifferent to shells, though nervous of small arms fire.

The drivers became so fond of their animals that they sometimes named them after Grand National winners and even their girlfriends and wives. However exhausting the day's march turned out, Witherington noted both mule drivers and accompanying troops would immediately start cutting grass for the animals after carefully unloading their cargo. He himself was shaken and upset when his own mule, carrying veterinary equipment, was killed after a Japanese patrol suddenly fired on them.

During his six months behind the lines, Witherington kept up his spirits by writing to his wife in letters scribbled with a sharpened bamboo, using gentian violet as ink. He eventually contracted typhus, and was left with a Sergeant in a jungle clearing, expected to die. But an American pilot flying overhead in a single-seater plane spotted them and arranged for them to be picked up and taken to hospital back in India. It was while recuperating on a houseboat in Srinigar that he wrote a full account of his experiences, which recognised the vital importance of being able to replace injured mules from the air. As a result he and Colonel Barlow began their experiments in anticipation of a third Chindit attack behind the lines; but it proved unnecessary after the Americans dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

After the war, Witherington became a veterinary officer at Kuala Lumpur and then chief veterinary officer for Singapore, where he and his wife worked together to develop an animal infirmary. They returned to Britain in 1951, briefly to run a small practice at Whitley Bay, before the National Hunt Committee appointed Witherington as its veterinary officer; his duties were soon extended to include flat racing. When the Jockey Club became concerned in the early 1960s about the increase in the incidence of doping racehorses, Witherington began to collaborate with the Animal Health Trust (AHT), using the forensic laboratory at Soham House in Newmarket.

He published a booklet on the markings of horses, which was an invaluable aid at an international meeting of racing authorities held in Paris in 1972. In the mid-1970s there were a number of incidents involving top-quality thoroughbreds, which performed unexpectedly badly during races. With the aid of research workers at Bristol veterinary school, Witherington developed a heart monitor that recorded an electro-cardiogram, which could then be transmitted from the racecourse to a receiver in Bristol, thus enabling rapid diagnosis of any previously unknown health conditions.

Witherington also worked closely with Michael Scott at the AHT's blood typing laboratory to ensure that horses' markings could be cross-checked, thus guaranteeing the accuracy of the Weatherby's general stud book. Retiring from the Jockey Club aged 65, Witherington worked for Tattersalls until 1999, ensuring that horses entered for sale could be identified accurately through medical records and checks. Having successfully led a team of vets in Cheshire during the 1967 outbreak of foot and mouth, he was greatly disturbed by the unnecessary slaughter of healthy animals during the 2001 epidemic. Douglas Witherington was awarded the Dalrymple Champneys Medal by the British Veterinary Association in 1981 and appointed OBE in 1985. He is survived by his wife Christina, whom he married in 1943, and their daughter.

From the Daily Telegraph obituary (30th November 2002) of Major Douglas Witherington, Royal Army Veterinary Corps:

Douglas Witherington, who has died aged 82, played an important role in devising a humane way of parachuting mules to the Chindits behind Japanese lines in Burma. The Americans had conducted experiments earlier in the Second World War by attaching parachutes to the animals, then pushing them out of an aircraft. Unfortunately, the first six beasts were fatally injured when the jerk of the opening parachute ruptured the mesentery artery, which feeds blood to the intestines. The remaining mules wisely resisted all efforts to make them follow.

Major Witherington and Lt-Colonel Ken Barlow, Royal Army Veterinary Corps, felt they could do better. They adapted a small inflatable assault dinghy, measuring 6.5 ft by 4 ft, into which a mule, heavily sedated with chloral-hydrate could be placed, with special padding to protect its private parts. Inside the plane a launching track was made, to ensure the smooth departure of the mule in its "raft" supported with six parachutes, which then floated down from about 600 ft. In the course of six experimental drops, they had one fatality, when a mule became caught up in a cluster of parachutes at the tail of the aircraft, broke free and made a precipitate descent, with the result that it sustained a spinal fracture and had to be destroyed in the dropping zone. The other five experiments, however, were successful. When the animals had their straps released after landing they got up showing some signs of sweating and stiffness, but no real distress and they were ready to carry heavy wireless equipment, ammunition and other weapons such as mortars and flame throwers.

On the first Chindit expedition behind Japanese lines in 1943, their mules had alerted the enemy to their positions by braying; so, when Witherington volunteered for the second expedition as part of 14 Brigade, he was given the task of muting the Brigade's beasts by removing their vocal cords under general anaesthetic.

In the field the Japanese recognised that mules were more important targets than men, since they carried the radio equipment on which operations depended for instructions. They proved more resilient than ponies and were indifferent to shells, though nervous of small arms fire.

The drivers became so fond of their animals that they sometimes named them after Grand National winners and even their girlfriends and wives. However exhausting the day's march turned out, Witherington noted both mule drivers and accompanying troops would immediately start cutting grass for the animals after carefully unloading their cargo. He himself was shaken and upset when his own mule, carrying veterinary equipment, was killed after a Japanese patrol suddenly fired on them.

During his six months behind the lines, Witherington kept up his spirits by writing to his wife in letters scribbled with a sharpened bamboo, using gentian violet as ink. He eventually contracted typhus, and was left with a Sergeant in a jungle clearing, expected to die. But an American pilot flying overhead in a single-seater plane spotted them and arranged for them to be picked up and taken to hospital back in India. It was while recuperating on a houseboat in Srinigar that he wrote a full account of his experiences, which recognised the vital importance of being able to replace injured mules from the air. As a result he and Colonel Barlow began their experiments in anticipation of a third Chindit attack behind the lines; but it proved unnecessary after the Americans dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

After the war, Witherington became a veterinary officer at Kuala Lumpur and then chief veterinary officer for Singapore, where he and his wife worked together to develop an animal infirmary. They returned to Britain in 1951, briefly to run a small practice at Whitley Bay, before the National Hunt Committee appointed Witherington as its veterinary officer; his duties were soon extended to include flat racing. When the Jockey Club became concerned in the early 1960s about the increase in the incidence of doping racehorses, Witherington began to collaborate with the Animal Health Trust (AHT), using the forensic laboratory at Soham House in Newmarket.

He published a booklet on the markings of horses, which was an invaluable aid at an international meeting of racing authorities held in Paris in 1972. In the mid-1970s there were a number of incidents involving top-quality thoroughbreds, which performed unexpectedly badly during races. With the aid of research workers at Bristol veterinary school, Witherington developed a heart monitor that recorded an electro-cardiogram, which could then be transmitted from the racecourse to a receiver in Bristol, thus enabling rapid diagnosis of any previously unknown health conditions.

Witherington also worked closely with Michael Scott at the AHT's blood typing laboratory to ensure that horses' markings could be cross-checked, thus guaranteeing the accuracy of the Weatherby's general stud book. Retiring from the Jockey Club aged 65, Witherington worked for Tattersalls until 1999, ensuring that horses entered for sale could be identified accurately through medical records and checks. Having successfully led a team of vets in Cheshire during the 1967 outbreak of foot and mouth, he was greatly disturbed by the unnecessary slaughter of healthy animals during the 2001 epidemic. Douglas Witherington was awarded the Dalrymple Champneys Medal by the British Veterinary Association in 1981 and appointed OBE in 1985. He is survived by his wife Christina, whom he married in 1943, and their daughter.

The main reason for including the above obituary to Robert McCrea's story, apart from the obvious veterinary connection between himself and Douglas Witherington, was a single photograph that Anne McCrea sent to me back in 2012. Seen below is an image of an enclosed container supported by at least five parachutes. Previously to reading Witherington's obituary, I had no idea what this image represented and did not include it as part of the original narrative. I now believe it to be a mule being dropped into Burma or India, safe inside it's pre-prepared raft as described by Douglas Witherington.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and Anne McCrea, April 2012.