Lt. MacHorton and the Battle of Kyaikthin

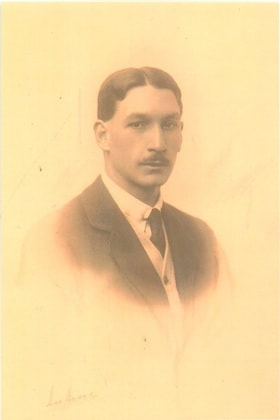

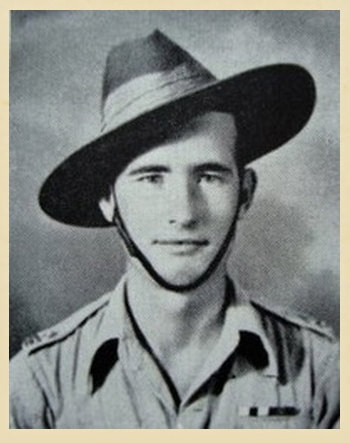

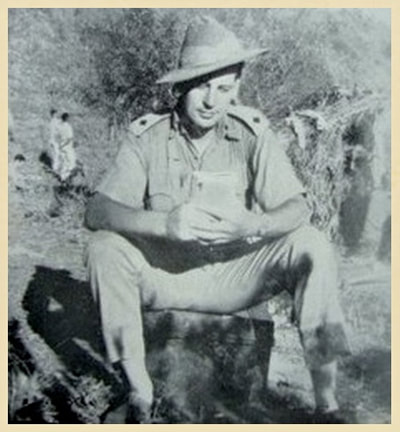

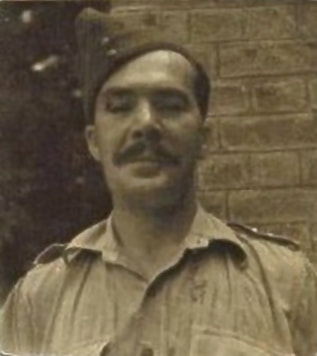

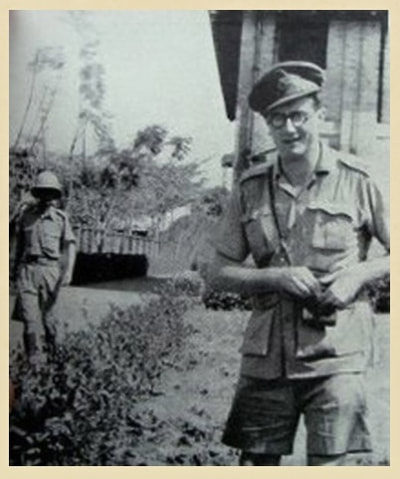

2nd Lieutenant Ian MacHorton.

2nd Lieutenant Ian MacHorton.

Glinting in the shadowy undergrowth beside my wounded leg, my .38 Colt revolver seemed to offer the answer to my unspoken question. Should I shoot myself, or wait until the Japs came to take me? I gazed at it lying at the foot of the little grassy bank against which I was propped. It would all be so easy. I only had to cock the gun, hold it with hand on my chest so that the black-rimmed snout was between my teeth; count, one, two, three and that would be all.

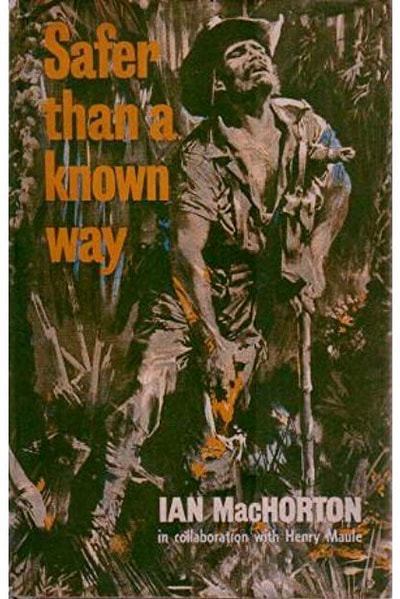

This was the soul-searching predicament that faced the wounded Lt. Ian MacHorton around the first week in April 1943, now unable to walk and left by his Chindit comrades in the hills above the Burmese town of Mong Mit. Thankfully, the young officer with great fortitude of purpose, decided against taking his own life that day and to place his fate with God. From this moment on his incredible story reads like that of an 1950's Boy's Own annual. It would be impossible for me to produce a worthy account of his adventures here, so please after reading this web page, search out and read for yourself MacHorton's book, Safer Than a Known Way.

Earlier in the war, a sixteen year old MacHorton had assisted his father in rescuing British soldiers from the beaches of Dunkirk, returning these exhausted men to the ports of Weymouth and Poole in Dorset. Sent overseas himself two years later, he attends the Officers Training Centre at Bangalore in his quest for a commission into the Indian Army. He then becomes a last minute recruit to Operation Longcloth, joining 77th Brigade in January 1943 alongside fellow Subalterns from 8th Gurkha Rifles, Alec Gibson and Harold James.

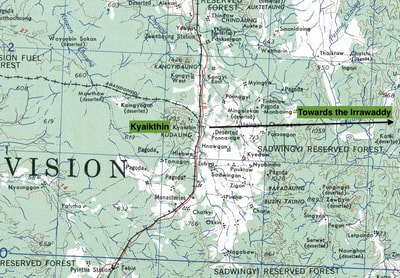

His two friends were allocated to No. 3 Column, led by Major Mike Calvert. Lt. MacHorton was posted to Southern Group and placed as Support Platoon commander into No. 2 Column, commanded by Major Arthur Emmett, a former tea-planter from Assam. No. 2 Column were tasked to be a decoy for the other Chindit columns on Operation Longcloth. Having performed this role with dutiful efficiency, the column became the first victims of a Japanese ambush on the night of the 2nd March on the outskirts of the railway town of Kyaikthin (phonetically Chaik-sin). It is from this point in MacHorton's book that we take up the story:

Before reaching Kyaikthin we travelled through some desperate country. Parched bushes and elephant grass offered such bitter opposition, that we decided to march instead along a river bed, up to our knees in water. Hands were torn and blistered and feet cracked and split because the constant immersion in water softened and crinkled them to the consistency of white bloodless pulp. Every day and all the time we sweated so that our clothing and equipment was black and stinking and becoming rotten with it, half the time our eyes were blinded with sweat. Every day our muscles ached and our bones almost groaned aloud in the agony of our exertions. Every day our filthy and sodden clothing became more and more torn, ripped and ragged until most of us looked like walking scarecrows.

On the 2nd March Columns 1 and 2 had reached the outskirts of Kyaikthin, Major Dunlop the commander of No. 1 Column, was given the order to blow up the railway bridge a few miles to the north, while No. 2 Column marched on towards the railway station close to the village. What neither group realised was that the Japanese had by now closed in on the unsuspecting Chindits and lay in wait just a short way up the tracks. To make matters worse, a problem with No. 1 Column's radio set now meant that the two units could no longer contact each other. Major Emmett's men, in the black of night stumbled into the enemy ambush which straddled both sides of the railway line embankment.

MacHorton recalled:

We shuffled to a halt as the guides probed forward. There came the sound of just one bang up front, then an inferno of noise engulfed the world around me. There came the high-pitched staccato scream of a machine gun, then overwhelmingly many others joined in, the crash and ping of rifle bullets, the banging of grenades as the battle reached a fearful crescendo. Men and mules were lying, twisted and contorted, twitching and writhing, others were still erect, stark in the moonlight, heaving and jerking in the midst of this chaos. Then a sinister scuffling noise made by men of all kinds in close combat. The close combat of bayonet and kukri, the fanatical, personal slaughter with blood-dripping cold steel.

From the book Wingate's Raiders, by Charles Rollo:

On the night of March 2nd, Major Arthur Emmett's column and Major Jefferies' party formed up at the foot of a hill in thin jungle three miles from Kyaikthin, a village situated on the railway forty miles south of Nankan. They planned to blow up the line at midnight. At 22:30 just as they were moving off, the enemy put in a surprise attack with two train-loads of troops sent down from Wuntho. It was a model attack carried out with great dash. The Japs closed in with mortars and machine-guns blazing, grenades exploding, and tracer bullets guiding their fire in the pitch dark. and made a terrific hullabaloo with fire crackers and wild battle-cries. The column mules stampeded, knocked over men, and broke up parties assembled for the attack on the railway. Loads came unhooked and equipment was scattered as the animals galloped off in all directions.

This was the first time that most of the force had been under fire. It was an ugly situation, but one that had been rehearsed time and again during the training period. The Chindits carried out a lightning dispersal into battle positions. Visibility was nil. Some parties of Chindits and Japs lay a few feet from each other, firing blind at sound. One Gurkha trooper bumped into a figure in the dark and gripped him by the hand. Simultaneously the two men whispered a greeting—one in Gurkhali, the other in Japanese. The Gurkha's reaction was quicker. In a flash he shoved his rifle into the Jap's stomach and pressed the trigger.

Skirmishing and sniping continued all the next day, while the Chindits, making the most of every scrap of cover in the thin jungle, assembled the mules and collected scattered equipment. One large group under Major Emmett found itself cut off with most of its mules killed or missing, the bulk of its equipment gone, and its wireless set lost, and was forced to retreat to the Chindwin. The rest of the force crept down to the railway that night in small parties according to a pre-arranged drill. At 03:00 hours the Japanese commander heard a sharp explosion followed by two more. The first glimmer of daylight revealed that the British had blown up the railway in three places right under his nose, and had vanished, leaving no tracks, into pathless jungle. The raiders assembled at a rendezvous a few miles from the line and pushed on eastward.

Several days later they were joined by Major Dunlop's column at a forward rendezvous ten miles west of the Irrawaddy. Dunlop's men had cut the railway in two places fifteen miles north of Kyaikthin without encountering any opposition. The battle of Kyaikthin had been a reverse. The losses in mules and equipment had been considerable and the Chindits had suffered a number of casualties. One sizeable party had been forced out of the campaign. Nevertheless, the two southern columns had so far achieved all their tactical objectives. They had succeeded in drawing the main Japanese concentrations away from the northern group. They had blown up the railway at five points according to plan. They remained a fighting body, and continued to advance towards the Irrawaddy.

2nd Lieutenant MacHorton and his small party of Gurkha Riflemen had survived the carnage at Kyaikthin and met up with some more of the battered and scattered soldiers from No. 2 Column the very next morning close to the railway embankment. Included in this group were MacHorton's friend, Lt. Arthur Best and RAF Liaison Officer, Flight Lieutenant John Edmonds. After a short discussion, the decision was made to continue on eastward to the pre-arranged rendezvous, in an attempt to join up with Major Dunlop and Colonel Alexander at the Irrawaddy.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including a map of the area around the Burmese village of Kyaikthin. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

This was the soul-searching predicament that faced the wounded Lt. Ian MacHorton around the first week in April 1943, now unable to walk and left by his Chindit comrades in the hills above the Burmese town of Mong Mit. Thankfully, the young officer with great fortitude of purpose, decided against taking his own life that day and to place his fate with God. From this moment on his incredible story reads like that of an 1950's Boy's Own annual. It would be impossible for me to produce a worthy account of his adventures here, so please after reading this web page, search out and read for yourself MacHorton's book, Safer Than a Known Way.

Earlier in the war, a sixteen year old MacHorton had assisted his father in rescuing British soldiers from the beaches of Dunkirk, returning these exhausted men to the ports of Weymouth and Poole in Dorset. Sent overseas himself two years later, he attends the Officers Training Centre at Bangalore in his quest for a commission into the Indian Army. He then becomes a last minute recruit to Operation Longcloth, joining 77th Brigade in January 1943 alongside fellow Subalterns from 8th Gurkha Rifles, Alec Gibson and Harold James.

His two friends were allocated to No. 3 Column, led by Major Mike Calvert. Lt. MacHorton was posted to Southern Group and placed as Support Platoon commander into No. 2 Column, commanded by Major Arthur Emmett, a former tea-planter from Assam. No. 2 Column were tasked to be a decoy for the other Chindit columns on Operation Longcloth. Having performed this role with dutiful efficiency, the column became the first victims of a Japanese ambush on the night of the 2nd March on the outskirts of the railway town of Kyaikthin (phonetically Chaik-sin). It is from this point in MacHorton's book that we take up the story:

Before reaching Kyaikthin we travelled through some desperate country. Parched bushes and elephant grass offered such bitter opposition, that we decided to march instead along a river bed, up to our knees in water. Hands were torn and blistered and feet cracked and split because the constant immersion in water softened and crinkled them to the consistency of white bloodless pulp. Every day and all the time we sweated so that our clothing and equipment was black and stinking and becoming rotten with it, half the time our eyes were blinded with sweat. Every day our muscles ached and our bones almost groaned aloud in the agony of our exertions. Every day our filthy and sodden clothing became more and more torn, ripped and ragged until most of us looked like walking scarecrows.

On the 2nd March Columns 1 and 2 had reached the outskirts of Kyaikthin, Major Dunlop the commander of No. 1 Column, was given the order to blow up the railway bridge a few miles to the north, while No. 2 Column marched on towards the railway station close to the village. What neither group realised was that the Japanese had by now closed in on the unsuspecting Chindits and lay in wait just a short way up the tracks. To make matters worse, a problem with No. 1 Column's radio set now meant that the two units could no longer contact each other. Major Emmett's men, in the black of night stumbled into the enemy ambush which straddled both sides of the railway line embankment.

MacHorton recalled:

We shuffled to a halt as the guides probed forward. There came the sound of just one bang up front, then an inferno of noise engulfed the world around me. There came the high-pitched staccato scream of a machine gun, then overwhelmingly many others joined in, the crash and ping of rifle bullets, the banging of grenades as the battle reached a fearful crescendo. Men and mules were lying, twisted and contorted, twitching and writhing, others were still erect, stark in the moonlight, heaving and jerking in the midst of this chaos. Then a sinister scuffling noise made by men of all kinds in close combat. The close combat of bayonet and kukri, the fanatical, personal slaughter with blood-dripping cold steel.

From the book Wingate's Raiders, by Charles Rollo:

On the night of March 2nd, Major Arthur Emmett's column and Major Jefferies' party formed up at the foot of a hill in thin jungle three miles from Kyaikthin, a village situated on the railway forty miles south of Nankan. They planned to blow up the line at midnight. At 22:30 just as they were moving off, the enemy put in a surprise attack with two train-loads of troops sent down from Wuntho. It was a model attack carried out with great dash. The Japs closed in with mortars and machine-guns blazing, grenades exploding, and tracer bullets guiding their fire in the pitch dark. and made a terrific hullabaloo with fire crackers and wild battle-cries. The column mules stampeded, knocked over men, and broke up parties assembled for the attack on the railway. Loads came unhooked and equipment was scattered as the animals galloped off in all directions.

This was the first time that most of the force had been under fire. It was an ugly situation, but one that had been rehearsed time and again during the training period. The Chindits carried out a lightning dispersal into battle positions. Visibility was nil. Some parties of Chindits and Japs lay a few feet from each other, firing blind at sound. One Gurkha trooper bumped into a figure in the dark and gripped him by the hand. Simultaneously the two men whispered a greeting—one in Gurkhali, the other in Japanese. The Gurkha's reaction was quicker. In a flash he shoved his rifle into the Jap's stomach and pressed the trigger.

Skirmishing and sniping continued all the next day, while the Chindits, making the most of every scrap of cover in the thin jungle, assembled the mules and collected scattered equipment. One large group under Major Emmett found itself cut off with most of its mules killed or missing, the bulk of its equipment gone, and its wireless set lost, and was forced to retreat to the Chindwin. The rest of the force crept down to the railway that night in small parties according to a pre-arranged drill. At 03:00 hours the Japanese commander heard a sharp explosion followed by two more. The first glimmer of daylight revealed that the British had blown up the railway in three places right under his nose, and had vanished, leaving no tracks, into pathless jungle. The raiders assembled at a rendezvous a few miles from the line and pushed on eastward.

Several days later they were joined by Major Dunlop's column at a forward rendezvous ten miles west of the Irrawaddy. Dunlop's men had cut the railway in two places fifteen miles north of Kyaikthin without encountering any opposition. The battle of Kyaikthin had been a reverse. The losses in mules and equipment had been considerable and the Chindits had suffered a number of casualties. One sizeable party had been forced out of the campaign. Nevertheless, the two southern columns had so far achieved all their tactical objectives. They had succeeded in drawing the main Japanese concentrations away from the northern group. They had blown up the railway at five points according to plan. They remained a fighting body, and continued to advance towards the Irrawaddy.

2nd Lieutenant MacHorton and his small party of Gurkha Riflemen had survived the carnage at Kyaikthin and met up with some more of the battered and scattered soldiers from No. 2 Column the very next morning close to the railway embankment. Included in this group were MacHorton's friend, Lt. Arthur Best and RAF Liaison Officer, Flight Lieutenant John Edmonds. After a short discussion, the decision was made to continue on eastward to the pre-arranged rendezvous, in an attempt to join up with Major Dunlop and Colonel Alexander at the Irrawaddy.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including a map of the area around the Burmese village of Kyaikthin. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

On the 7th March, the survivors from No. 2 Column met up with Colonel Alexander and Major Dunlop at the Irrawaddy. The amalgamated group crossed the river at Tagaung and then moved directly into the jungle on the eastern shoreline. After receiving orders from Brigade Head Quarters, they moved off in a south-easterly direction towards the town of Mogok. Here they were supposed to liaise with Major D.C. Herring and his Kachin Levies, but their advance was hampered by thick-set bamboo jungle and the meeting was missed.

Southern Group now found themselves the most easterly placed Chindit unit and by that very nature the furthest from the safety of India. All remaining Chindit columns were now over the Irrawaddy and placed in a natural box contained on three sides by the Shweli and Irrawaddy Rivers, with the Mogok-Mong Mit motor road to the south; the force had become unexpectedly trapped and slowly the Japanese began to close in.

Back in India, 4 Corps HQ suggested to Wingate that he return his Brigade to Allied held territory and the dispersal signal was given to all columns in late March. Alexander had a very clear vision in his mind at this point; to return his group back to India in one piece and as one unit. However, after several days attempting to avoid contact with the Japanese around Mong Mit, the Colonel reluctantly agreed to jettison the majority of his mules and all of the heavy arms and equipment. The men again met with disaster on April 6th, when they arrived late at a supply drop location, but in time to see the planes heading home still fully laden. Alexander held an officers conference, where the decision was made to disperse either into the Chinese Province of Yunnan, or north to Fort Hertz.

A few days later in the foothills around Loi Sau, the rear of Southern Group were ambushed by the Japanese and incurred several battle casualties. One of these was Lt. MacHorton who had been struck in the upper leg by mortar bomb shrapnel. The column Medical Officer, Dr. Norman Stocks tended and dressed his wound, but could not extract the shrapnel fragment from his leg.

Southern Group now found themselves the most easterly placed Chindit unit and by that very nature the furthest from the safety of India. All remaining Chindit columns were now over the Irrawaddy and placed in a natural box contained on three sides by the Shweli and Irrawaddy Rivers, with the Mogok-Mong Mit motor road to the south; the force had become unexpectedly trapped and slowly the Japanese began to close in.

Back in India, 4 Corps HQ suggested to Wingate that he return his Brigade to Allied held territory and the dispersal signal was given to all columns in late March. Alexander had a very clear vision in his mind at this point; to return his group back to India in one piece and as one unit. However, after several days attempting to avoid contact with the Japanese around Mong Mit, the Colonel reluctantly agreed to jettison the majority of his mules and all of the heavy arms and equipment. The men again met with disaster on April 6th, when they arrived late at a supply drop location, but in time to see the planes heading home still fully laden. Alexander held an officers conference, where the decision was made to disperse either into the Chinese Province of Yunnan, or north to Fort Hertz.

A few days later in the foothills around Loi Sau, the rear of Southern Group were ambushed by the Japanese and incurred several battle casualties. One of these was Lt. MacHorton who had been struck in the upper leg by mortar bomb shrapnel. The column Medical Officer, Dr. Norman Stocks tended and dressed his wound, but could not extract the shrapnel fragment from his leg.

Now unable to walk, MacHorton knew that he would have to be left there in the jungle in the hills above Mong Mit. All Chindits had been told before the expedition, that if they could no longer keep up with their column, then they would have to be left at best in the hands of the Headman of a friendly Kachin village. Colonel Alexander came to speak with the stricken 2nd Lieutenant and made the difficult decision to leave him behind. In the first instance, MacHorton's Gurkha Orderly, Kulbahadur Thapa was set to remain and keep his officer company. However, MacHorton would have none of this and bravely sent his Gurkha comrade on his way to re-join the rest of the column.

It is from this point in his book, Safer Than a Known Way, that MacHorton's Longcloth adventures truly begin. After coming to terms with being left in the jungle, the young Subaltern falls into a delirious sleep which lasts for several hours. He is awoken by the sound of a motor vehicle and to his horror realises that a Japanese search patrol are moving along the track just a few yards from where he is concealed. He is within a whisker of being discovered, when for some unknown reason the Japanese patrol suddenly move away from the area.

After another period of semi-consciousness, MacHorton decides that he must move from his present position and ignoring the excruciating pain from his leg forces himself to his feet. Creating an improvised crutch from a stout bamboo cane he begins his slow and painful journey east towards the Chinese Borders. After two days stumbling along the hill tracks and leaning heavily on his makeshift crutch, he collapses with exhaustion and drifts into near delirium. Incredibly he is found by two Shan woodcutters and taken to a village where the Headman is an ex-Gurkha Rifleman. He remains in the village for around two weeks, gradually re-building his strength and allowing his wounded leg to heal. He reluctantly has to leave the sanctity of the village when a Japanese patrol returns to the area. He is given a guide by the village Headman, who leads him away north-west towards the Irrawaddy River, where hopefully he might have the a chance of re-joining his Chindit column.

After several days march, MacHorton and his guide stumble across a fresh trail likely to be that of No. 1 Column in their advance to the Irrawaddy. The guide leaves him at this point and he chases after his comrades across a succession of waterless arid plains and elephant grass.

NB. During the period recuperating at the village, No. 1 Column had suffered several setbacks in their journey east towards Yunnan Province. These included two further skirmishes with the enemy and a failed attempt to cross the Shweli River. In the end, Colonel Alexander and Major Dunlop were forced to abandon their original plans and turned west once more and made for India.

It was this change of direction by No. 1 Column that gave MacHorton the chance of an unlikely reunion and by amazing coincidence he finds his Chindit colleagues just about to re-cross the Irrawaddy at Tagaung (Sinhnyat) and joins the final two country boats alongside Doc Lusk, No. 2 Column's Medical Officer, as they begin to cross the river. Disastrously, these boats are ambushed just as they are about to come ashore on the west bank. Many of the men are killed, but MacHorton escapes the carnage alongside a British Corporal and they continue their march out of Burma.

Not long after the incident at the Irrawaddy, MacHorton collects up another group of Chindits, led at that time by Sgt. Hayes, No. 1 Column's RAF Liaison Sergeant. Many of the men in this extended group of around fourteen are wounded or suffering from malnutrition or disease. The party continue a forced march westward, directed by MacHorton's compass and the unnamed Corporal's escape map. One by one the exhausted Chindits fall by the wayside, until by good fortune they stumble upon a friendly village and receive much needed rest, food and medical attention.

MacHorton's group then cross the railway line and the very next day bump into the remnants of No. 1 Column once again, this time at a village just east of the Mu River. MacHorton reacquaints himself with Arthur Best, Colonel Alexander and Major Dunlop. The column are ambushed again as they try to ford the waist deep river. Many are killed in the water including the Corporal and MacHorton is shot in the leg and falls unconscious into the jungle scrub just beyond the river. When he awakes he realises to his utter dismay, that he has become a prisoner of war and spends the next few days in a semi-conscious state, being driven eastwards in a truck towards the town of Kalewa.

After recovering his wits, he takes the opportunity to escape his captors during an evening stopover at a village and disappears quickly into the surrounding jungle. Striking roughly north-west he travels through the escarpment leading to the Chindwin Valley and after several arduous days marching, picks up a tributary of the river and incredibly after following this for a few hours, meets Major Dunlop and some of the other column officers once more. Included amongst these men is RAF Sergeant Hayes, who sadly is now dying from the effects of his wounds and the disease beri beri. After another clash, this time with members of the Burma Traitor Army, the group are split for a third time and MacHorton, now all alone, finally swims across the 800 yard wide Chindwin River.

Once over he strikes out for the Yu River which he knows will eventually lead him to Tamu and most likely British Forces. Weak with hunger and exhaustion he stumbles on for several days, often in near delirium and living only on what he can find in the jungle. He is picked up by a patrol from the Maharatta Regiment on the 15th May 1943 and is taken by truck to the 19th Casualty Clearing Station at Imphal, where he is tended by Matron Agnes McGearey. After a six week period of rest and recuperation, he returns to Dehra Dun and the 2nd Gurkha Rifles Regimental Centre, where he is re-united with his Orderly Kulbahadur Thapa and many of the other survivors from Operation Longcloth.

Seen below is another gallery of images in relation to this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

It is from this point in his book, Safer Than a Known Way, that MacHorton's Longcloth adventures truly begin. After coming to terms with being left in the jungle, the young Subaltern falls into a delirious sleep which lasts for several hours. He is awoken by the sound of a motor vehicle and to his horror realises that a Japanese search patrol are moving along the track just a few yards from where he is concealed. He is within a whisker of being discovered, when for some unknown reason the Japanese patrol suddenly move away from the area.

After another period of semi-consciousness, MacHorton decides that he must move from his present position and ignoring the excruciating pain from his leg forces himself to his feet. Creating an improvised crutch from a stout bamboo cane he begins his slow and painful journey east towards the Chinese Borders. After two days stumbling along the hill tracks and leaning heavily on his makeshift crutch, he collapses with exhaustion and drifts into near delirium. Incredibly he is found by two Shan woodcutters and taken to a village where the Headman is an ex-Gurkha Rifleman. He remains in the village for around two weeks, gradually re-building his strength and allowing his wounded leg to heal. He reluctantly has to leave the sanctity of the village when a Japanese patrol returns to the area. He is given a guide by the village Headman, who leads him away north-west towards the Irrawaddy River, where hopefully he might have the a chance of re-joining his Chindit column.

After several days march, MacHorton and his guide stumble across a fresh trail likely to be that of No. 1 Column in their advance to the Irrawaddy. The guide leaves him at this point and he chases after his comrades across a succession of waterless arid plains and elephant grass.

NB. During the period recuperating at the village, No. 1 Column had suffered several setbacks in their journey east towards Yunnan Province. These included two further skirmishes with the enemy and a failed attempt to cross the Shweli River. In the end, Colonel Alexander and Major Dunlop were forced to abandon their original plans and turned west once more and made for India.

It was this change of direction by No. 1 Column that gave MacHorton the chance of an unlikely reunion and by amazing coincidence he finds his Chindit colleagues just about to re-cross the Irrawaddy at Tagaung (Sinhnyat) and joins the final two country boats alongside Doc Lusk, No. 2 Column's Medical Officer, as they begin to cross the river. Disastrously, these boats are ambushed just as they are about to come ashore on the west bank. Many of the men are killed, but MacHorton escapes the carnage alongside a British Corporal and they continue their march out of Burma.

Not long after the incident at the Irrawaddy, MacHorton collects up another group of Chindits, led at that time by Sgt. Hayes, No. 1 Column's RAF Liaison Sergeant. Many of the men in this extended group of around fourteen are wounded or suffering from malnutrition or disease. The party continue a forced march westward, directed by MacHorton's compass and the unnamed Corporal's escape map. One by one the exhausted Chindits fall by the wayside, until by good fortune they stumble upon a friendly village and receive much needed rest, food and medical attention.

MacHorton's group then cross the railway line and the very next day bump into the remnants of No. 1 Column once again, this time at a village just east of the Mu River. MacHorton reacquaints himself with Arthur Best, Colonel Alexander and Major Dunlop. The column are ambushed again as they try to ford the waist deep river. Many are killed in the water including the Corporal and MacHorton is shot in the leg and falls unconscious into the jungle scrub just beyond the river. When he awakes he realises to his utter dismay, that he has become a prisoner of war and spends the next few days in a semi-conscious state, being driven eastwards in a truck towards the town of Kalewa.

After recovering his wits, he takes the opportunity to escape his captors during an evening stopover at a village and disappears quickly into the surrounding jungle. Striking roughly north-west he travels through the escarpment leading to the Chindwin Valley and after several arduous days marching, picks up a tributary of the river and incredibly after following this for a few hours, meets Major Dunlop and some of the other column officers once more. Included amongst these men is RAF Sergeant Hayes, who sadly is now dying from the effects of his wounds and the disease beri beri. After another clash, this time with members of the Burma Traitor Army, the group are split for a third time and MacHorton, now all alone, finally swims across the 800 yard wide Chindwin River.

Once over he strikes out for the Yu River which he knows will eventually lead him to Tamu and most likely British Forces. Weak with hunger and exhaustion he stumbles on for several days, often in near delirium and living only on what he can find in the jungle. He is picked up by a patrol from the Maharatta Regiment on the 15th May 1943 and is taken by truck to the 19th Casualty Clearing Station at Imphal, where he is tended by Matron Agnes McGearey. After a six week period of rest and recuperation, he returns to Dehra Dun and the 2nd Gurkha Rifles Regimental Centre, where he is re-united with his Orderly Kulbahadur Thapa and many of the other survivors from Operation Longcloth.

Seen below is another gallery of images in relation to this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

From the pages of Safer Than a Known Way:

I watched the first grey streaks of dawn steal through the towering black mass of the teak trees around us. As I watched their foliage merged almost imperceptibly from black to deep purple and then from purple through lessening darkness until finally they were green. Once more jungle night was becoming jungle day. But this was a day different from all the others. As far as I could see there was myself, my six Gurkhas and the badly wounded Premsingh Gurung, and the Havildar and his five Gurkhas. Were we the sole survivors of the whole of No. 2 Column?

I thought it would be fitting, to end this narrative with a Roll of Honour made up from the Gurkhas who served alongside Lt. MacHorton at the battle of Kyaikthin and in some cases beyond. Three of the soldiers, Naik Premsingh Gurung, Havildar Lalbahadur Thapa and Rifleman Lal Bahadur Thapa are already mentioned on other pages of this website.

To read more about these three brave men, please click on the following link: 3/2 Gurkha Roll Call

MacHorton's Gurkhas

Naik Premsingh Gurung. A Bren gun operative in No. 2 Column's Support Platoon. This soldier was wounded at Kyaikthin and had to be left behind by his comrades, close to the railway line on the 3rd March 1943. This brave Gurkha chose to take his own life with a single bullet from his rifle, rather than be taken prisoner by the Japanese.

Rfm. Lal Bahadur Thapa. This soldier was killed in action during the battle at Kyaikthin on the 2nd March 1943. According to the pages of Safer Than a Known Way, Lal Bahadur was positioned directly to Lt. MacHorton's left hand side on the railway embankment when he was killed.

Havildar Lalbahadur Thapa. This Gurkha Sergeant had led a small section of Gurkhas away from the battle at Kyaikthin and met up with Lt. MacHorton later that same evening. He was sadly killed in action during the engagement at Loi Sau in April 1943, where he was involved in rescuing the now wounded MacHorton from a vulnerable position in front of the enemy.

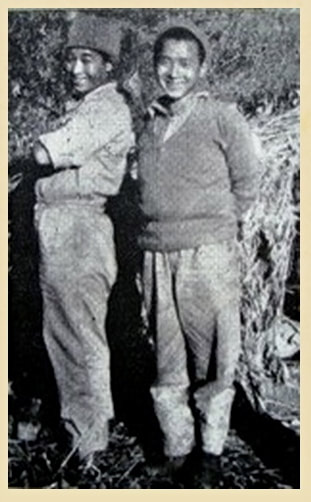

Rfm. Kalu Rana and Rfm. Lachiman Pun. Known affectionately by their comrades as the Heavenly Twins because they were inseparable during the operation in 1943. Both these Gurkhas survived the action at Kyaikthin and were used as scouts during the remainder of the expedition. It is known that Kalu Rana was wounded during the battle at Loi Sau in early April, but it is not clear whether he or Lachiman Pun managed to return safely to India.

Rfm. Karnabar Thapa. This soldier was lost to line of march after the outward crossing of the Irrawaddy. He was never seen or heard of again.

Rfm. Tartabsingh Thapa. This Gurkha was lost not long after Karnabar Thapa, when he failed to answer a morning roll call in mid-March 1943, after the column made a hasty departure from an overnight bivouac. He was never heard of again.

Rfm. Gore Pun. Collapsed through exhaustion whilst the column were marching north-east through the Shan Hills.

Rfm. (Orderly) Kulbahadur Thapa. This Gurkha soldier was chosen as MacHorton's orderly on Operation Longcloth and had shadowed him faithfully during the early weeks inside Burma. He was by the young officer's side during the engagement at Kyaikthin, and again at the battle of Loi Sau where MacHorton was wounded.

Lt. MacHorton remembers:

Kulbahadur was cutting away the undergrowth to create a space for me to lie up and hopefully regain my strength. I noticed he was clearing quite a large area and told him to stop. He answered that the space was not just for one man, but two and that he intended to remain with me. I was astounded by this action and fell silent for a minute. Kulbahadur went on to elaborate, saying that as my orderly it was his duty to stay with me. The magnificence of his loyalty touched me deeply. The rush of relief to hear that I would not be alone, soon turned to the sad realisation that I could not ask him to give up his freedom and probably his life, by remaining with me in that lonely jungle copse. Digging deep I found the resolve to ask and then order Kulbahadur to leave me where I lay and rejoin the column. Just before he went on his way Kulbahadur announced that we would certainly meet again some day, of this he felt sure, then there was a rustle of leaves and he was gone.

This story is dedicated to the memory of Rifleman Kulbahadur Thapa, a soldier of integrity and great devotion to duty.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, August 2018.

I watched the first grey streaks of dawn steal through the towering black mass of the teak trees around us. As I watched their foliage merged almost imperceptibly from black to deep purple and then from purple through lessening darkness until finally they were green. Once more jungle night was becoming jungle day. But this was a day different from all the others. As far as I could see there was myself, my six Gurkhas and the badly wounded Premsingh Gurung, and the Havildar and his five Gurkhas. Were we the sole survivors of the whole of No. 2 Column?

I thought it would be fitting, to end this narrative with a Roll of Honour made up from the Gurkhas who served alongside Lt. MacHorton at the battle of Kyaikthin and in some cases beyond. Three of the soldiers, Naik Premsingh Gurung, Havildar Lalbahadur Thapa and Rifleman Lal Bahadur Thapa are already mentioned on other pages of this website.

To read more about these three brave men, please click on the following link: 3/2 Gurkha Roll Call

MacHorton's Gurkhas

Naik Premsingh Gurung. A Bren gun operative in No. 2 Column's Support Platoon. This soldier was wounded at Kyaikthin and had to be left behind by his comrades, close to the railway line on the 3rd March 1943. This brave Gurkha chose to take his own life with a single bullet from his rifle, rather than be taken prisoner by the Japanese.

Rfm. Lal Bahadur Thapa. This soldier was killed in action during the battle at Kyaikthin on the 2nd March 1943. According to the pages of Safer Than a Known Way, Lal Bahadur was positioned directly to Lt. MacHorton's left hand side on the railway embankment when he was killed.

Havildar Lalbahadur Thapa. This Gurkha Sergeant had led a small section of Gurkhas away from the battle at Kyaikthin and met up with Lt. MacHorton later that same evening. He was sadly killed in action during the engagement at Loi Sau in April 1943, where he was involved in rescuing the now wounded MacHorton from a vulnerable position in front of the enemy.

Rfm. Kalu Rana and Rfm. Lachiman Pun. Known affectionately by their comrades as the Heavenly Twins because they were inseparable during the operation in 1943. Both these Gurkhas survived the action at Kyaikthin and were used as scouts during the remainder of the expedition. It is known that Kalu Rana was wounded during the battle at Loi Sau in early April, but it is not clear whether he or Lachiman Pun managed to return safely to India.

Rfm. Karnabar Thapa. This soldier was lost to line of march after the outward crossing of the Irrawaddy. He was never seen or heard of again.

Rfm. Tartabsingh Thapa. This Gurkha was lost not long after Karnabar Thapa, when he failed to answer a morning roll call in mid-March 1943, after the column made a hasty departure from an overnight bivouac. He was never heard of again.

Rfm. Gore Pun. Collapsed through exhaustion whilst the column were marching north-east through the Shan Hills.

Rfm. (Orderly) Kulbahadur Thapa. This Gurkha soldier was chosen as MacHorton's orderly on Operation Longcloth and had shadowed him faithfully during the early weeks inside Burma. He was by the young officer's side during the engagement at Kyaikthin, and again at the battle of Loi Sau where MacHorton was wounded.

Lt. MacHorton remembers:

Kulbahadur was cutting away the undergrowth to create a space for me to lie up and hopefully regain my strength. I noticed he was clearing quite a large area and told him to stop. He answered that the space was not just for one man, but two and that he intended to remain with me. I was astounded by this action and fell silent for a minute. Kulbahadur went on to elaborate, saying that as my orderly it was his duty to stay with me. The magnificence of his loyalty touched me deeply. The rush of relief to hear that I would not be alone, soon turned to the sad realisation that I could not ask him to give up his freedom and probably his life, by remaining with me in that lonely jungle copse. Digging deep I found the resolve to ask and then order Kulbahadur to leave me where I lay and rejoin the column. Just before he went on his way Kulbahadur announced that we would certainly meet again some day, of this he felt sure, then there was a rustle of leaves and he was gone.

This story is dedicated to the memory of Rifleman Kulbahadur Thapa, a soldier of integrity and great devotion to duty.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, August 2018.

Update 06/06/2024.

On the 17th April 2024, I was delighted to receive the following email:

Hi Steve,

Firstly I'd like to commend you on the website - clearly a lot of time and dedication has gone into its construction. My grandmother gave me a copy of Safer Than a Known Way when I was in my 20's and I thought it was excellent. Having just re-read it at 42 years old, I still think it's an incredible story well worthy of re-print. Thanks to your website (which wasn't around when I first read the book), I have now been able to see the faces of Kulbahadur, Premsingh Gurung and Arthur Best. Many thanks again - this brings a whole new and fresh perspective to the book.

I have a Virtual Reality headset attached to a gaming PC and with it I use Google Earth to fly around the world in 3D (from the safety of my house) looking at and landing on various parts of the world I've read about in books. Using the headset I had identified what I thought to be Old Baldy and thanks to the maps on your website I can see that I was now correct. In the software I can see the view that Ian Machorton and the Chindits would have been able to see from the top of the mountain. I also looked down onto the Kyaikthin railway ambush site from the nearby hills thanks to your map (I could not identify where this was originally). I was wondering - where do you think the village that Ian Machorton was looked after by the former Gurkha Headman is located? Could it be Lwal Wein village do you think? I feel like it fits the description in the book in many ways but might be well off. I would be interested in hearing your views.

Kind regards, Ben Duckham

I replied:

Dear Ben,

Thank you for your email contact via my website in relation to Ian Machorton and his experiences on Operation Longcloth. I was extremely interested to hear about your Google Earth adventures and impressed that you have visited (so to speak) some of the places featured within MacHorton's story and that my maps were of some use to you in doing so. I have never considered where the Gurkha Headman's village might be located and so cannot give any real input in answering that question. I did wonder however, if there was a way of capturing usable images from your virtual journeys to Old Baldy and Kyaikthin, which I might be able to add to MacHorton's web page. Thanks again for making contact and for your kind words in relation to my work.

Ben has now done some fantastic work for me in producing the following gallery of images in relation to Ian MacHorton and his Longcloth pathway in 1943. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Ben then went on to produce a narrative, which he has supported by further Google Earth images, in mapping out Lt. MacHorton's potential journey from the point he was left by his comrades after being wounded in early April 1943 and which ultimately led to his stay at the friendly Burmese village presided over by the former Gurkha Rifleman.

Ben explains:

And so to the route and village that seems to tick a number of the boxes described by MacHorton in the immediate aftermath of his injury on Old Baldy. Of course that village may no longer exist and what I illustrate within this narrative may be pure coincidence, so you'll have to indulge me on this one. Lwal Wein village is the one I mentioned in my initial email to you for a few reasons, some of which form part of MacHorton's description in his book:

"As we reached the roadway the rest of the column overtook us, threading their way down from the hilltop where we had fought the Japs. Slowly and painfully we crossed to the far side of the road.......they carried me up the steep slope which was the beginning of the jungle and sat me down in a small basin overlooking the road. Then they too were gone in the wake of the column, marching fast up a winding track which climbed with the ridge of an undulating jungle-clad spur directly opposite the one which we had struggled down from our mountain top."

If indeed the track described by MacHorton is the one illustrated in the attached images, the track has clearly now been enlarged into a dirt road (possibly because the village now houses a Monastery). It looks like there is an anomaly in the book where the authors describe the Japanese trucks arriving directly below MacHorton on the motor road - "the noise of the engines grew louder, approaching from the right, the direction of Mong Mit." Given that MacHorton had crossed the road by this point, if the truck came from the right it would have been coming from Mogok. A small point, but I noted it given that I was trying to understand his exact positioning by this point in time.

By now MacHorton is alone in the jungle, but there are then more hints in the book, as to the location of the village:

"The jungle track of dirt and rock which I was climbing up was some six feet wide, and was quite even underfoot. For stretches it rose very steeply and as I shuffled painfully onwards and upwards it became increasingly apparent that I was spiralling up the side of a mountain."

Also......

"These tracks of pursued and pursuers disappeared into the green depths of jungle, where the left-forking path rounded a thickly forested spur. Not unnaturally I chose the right-fork. I followed it until the steep slope dropping away on its right suddenly became gradual enough for me to slither down. And with an ease and lack of painful jolting which was an agreeable surprise, I slid down on my back to emerge almost gracefully through some undergrowth into the seclusion of a miniature well-hidden little valley."

If you remember from the book Steve, this valley is where MacHorton was disturbed by a Doe (female deer) in the middle of his first night alone. As mentioned, clearly the left forking track around a spur would now be the dirt road.

Seen below is a gallery of images in support of Ben's detailed narrative so far. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

The Village Location:

"It nestled at the top of a long sloping valley, and straight up behind it rose two towering thickly forested mountains sloping steeply down to each other to intersect immediately behind the village."

Maybe some poetic licence here from MacHorton regarding the two mountains, but the tops of the two ridges of the valley that frame the hamlet today, do look like they sit behind the village, albeit not perfectly.

"Along the full length of the valley on each side of it an almost vertical strip had been cleared of forest and carved beautifully into terraces."

If Lwal Wein is the village MacHorton describes it has reduced in size and no longer has these terraces, but that being said, it looks like that there might have been a clearing down on both sides of the valley. For instance, on the left or south side of the valley it has much smaller growth (as opposed to trees) which could indicate that it had been cleared in the past and shrubs are now taking over. I doubt it takes the jungle very long to reclaim any previously cultivated land.

The Village itself:

"From where I lay on the Thugyi's cooly-shaded veranda I could gaze down on nearly the whole of the village. His house was built at the foot of the Pagoda hill and, as befitted the headman of the community, it commanded the most magnificent view of the community."

If you search for Lwal Wein village Monastery in Google you can locate a number of photos of the village - including one that shows an old building with a veranda which was possibly the Headman's with a Pagoda in the background (see map in the gallery below). It looks like the newer bigger building to the right might be where they've built the Monastery.

"The glistening emerald undulations of tens of thousands of acres of forests and jungle dropped away gently to merge into the blue, shimmering heat-haze that lay along the lower foothills of the next range of blue-green mountains. Beyond them rose fantastically the snow-covered peaks of the Yunnan range."

The photographic view from the village (see the last image in the gallery below) is in the correct orientation for the above description and looks directly to the North-East in the direction of China. In the end, perhaps my imagination is running away with me, however I felt there were some compelling indicators to suggest that Lwal Wein might well be the village mentioned in the book. We will likely never learn the truth, but either way I've enjoyed putting it all together and hope that it has been of some interest to you Steve and to those that might read it in the future.

Seen below is a second gallery of images provided by Ben and that illustrate his narrative above. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. I would like to take this opportunity to thank Ben for his great efforts in bringing this unusual and rather intriguing account of Lt. MacHorton's potential pathway to the temporary sanctuary of Lwal Wein village.

"It nestled at the top of a long sloping valley, and straight up behind it rose two towering thickly forested mountains sloping steeply down to each other to intersect immediately behind the village."

Maybe some poetic licence here from MacHorton regarding the two mountains, but the tops of the two ridges of the valley that frame the hamlet today, do look like they sit behind the village, albeit not perfectly.

"Along the full length of the valley on each side of it an almost vertical strip had been cleared of forest and carved beautifully into terraces."

If Lwal Wein is the village MacHorton describes it has reduced in size and no longer has these terraces, but that being said, it looks like that there might have been a clearing down on both sides of the valley. For instance, on the left or south side of the valley it has much smaller growth (as opposed to trees) which could indicate that it had been cleared in the past and shrubs are now taking over. I doubt it takes the jungle very long to reclaim any previously cultivated land.

The Village itself:

"From where I lay on the Thugyi's cooly-shaded veranda I could gaze down on nearly the whole of the village. His house was built at the foot of the Pagoda hill and, as befitted the headman of the community, it commanded the most magnificent view of the community."

If you search for Lwal Wein village Monastery in Google you can locate a number of photos of the village - including one that shows an old building with a veranda which was possibly the Headman's with a Pagoda in the background (see map in the gallery below). It looks like the newer bigger building to the right might be where they've built the Monastery.

"The glistening emerald undulations of tens of thousands of acres of forests and jungle dropped away gently to merge into the blue, shimmering heat-haze that lay along the lower foothills of the next range of blue-green mountains. Beyond them rose fantastically the snow-covered peaks of the Yunnan range."

The photographic view from the village (see the last image in the gallery below) is in the correct orientation for the above description and looks directly to the North-East in the direction of China. In the end, perhaps my imagination is running away with me, however I felt there were some compelling indicators to suggest that Lwal Wein might well be the village mentioned in the book. We will likely never learn the truth, but either way I've enjoyed putting it all together and hope that it has been of some interest to you Steve and to those that might read it in the future.

Seen below is a second gallery of images provided by Ben and that illustrate his narrative above. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. I would like to take this opportunity to thank Ben for his great efforts in bringing this unusual and rather intriguing account of Lt. MacHorton's potential pathway to the temporary sanctuary of Lwal Wein village.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and Ben Duckham, June 2024.