Sergeant Bert Fitton

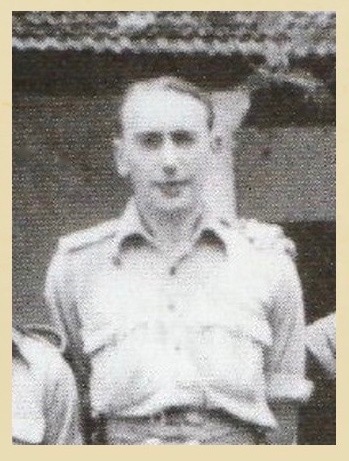

Bert Fitton, India 1942.

Bert Fitton, India 1942.

Sergeant 3781624 Herbert Fitton was the son of Thomas and Agnes Fitton from Newton Heath in Manchester. Bert married Annie Greaves in the summer of 1939 and they lived at 34 Park Street in Prestwich, Lancashire.

Sgt. Fitton was an original member of the 13th Battalion, the King's Liverpool Regiment and one of the men who voyaged to India aboard the troopship 'Oronsay', leaving Liverpool Docks on the 8th December 1941. Bert was part of C' Company within the 13th Battalion and as such became part of Chindit Column 7 during the training for Operation Longcloth in the summer of 1942. 7 Column was led by Major Kenneth Gilkes, also of the King's Regiment.

Early in the operation, 7 Column shadowed Wingate and his Brigade Head Quarters and Sgt. Fitton remained with Gilkes' unit up until the orders were received to return to India. On the 29th March 1943, Wingate's HQ, Chindit Columns 7 and 8 and Northern Group's Head Quarters were all gathered on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River close to the Burmese village of Inywa.

A bridgehead party was formed and began crossing the mile wide river in hired country boats, which were manned and piloted by local Burmese villagers. A Japanese patrol on the western banks opened up on the leading boats with machine gun and mortar fire and many casualties were inflicted on the Chindits attempting to cross the river. Wingate and his column commanders decided to abandon the crossing and moved back in to the scrub jungle close to the riverside. Eventually, the orders were given for the various columns to split up and Wingate sent Scott and Gilkes away from the area around Inywa.

At some point during the confusion at Inywa, Sergeant Fitton was separated from 7 Column and joined up with Northern Group Head Quarters and 8 Column who had decided to amalgamate their number for the return journey to India. By the 3rd April and with the help of RAF dinghies dropped to the men from the supply planes of 31 Squadron, the large force led by Major Scott was over the Shweli River and once again heading for banks of the Irrawaddy, but this time much further to the north.

Over the next few weeks the Chindits investigated many possible crossing points, but were always foiled in some way or another in acquiring the means to traverse the mile wide watery obstacle. The Japanese, now completely aware of the Chindits intentions had removed all boats from the banks of the river and now patrolled the waters in motor launches between the villages of Zinbon and Myale. Tony Aubrey, in his book 'With Wingate in Burma', summed up those desperate days:

"We saw and heard nothing of the enemy. But, always on our left, lurking like some inescapable monster, lay the implacable Irrawaddy. It had begun to be almost an obsession with us now, this river. There it lay, flowing calmly and serenely southwards. But, however much water flowed down, there was always enough left to act as a seemingly impassible barrier between ourselves and home. It had assumed a personality. I was surprised that I didn't dream about it at night."

Then, on the 20th April, Major Scott noticed a Burmese junk making its way down river close to where the Chindits were lying up. He seized his chance and with the assistance of Lieutenant George Borrow and Havildar Lanval of the Burma Rifles, hijacked the boat. Paying the junks owner handsomely in silver rupees, the column were over the river in just less than ninety minutes. Hurriedly, the Chindits melted away into the scrub jungle on the far bank and headed north-west.

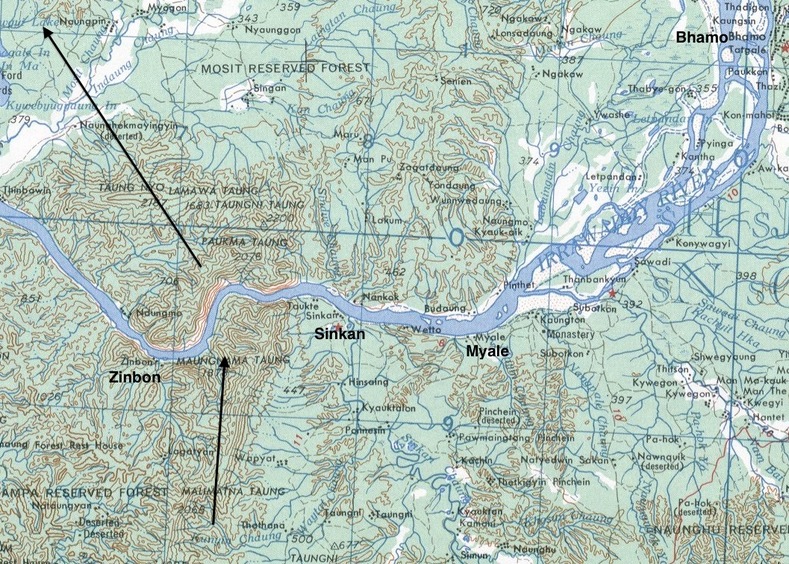

Seen below is a map of the Irrawaddy around the area of Zinbon, the crossing point for 8 Column and Northern Group HQ on the 20th April 1943. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Sgt. Fitton was an original member of the 13th Battalion, the King's Liverpool Regiment and one of the men who voyaged to India aboard the troopship 'Oronsay', leaving Liverpool Docks on the 8th December 1941. Bert was part of C' Company within the 13th Battalion and as such became part of Chindit Column 7 during the training for Operation Longcloth in the summer of 1942. 7 Column was led by Major Kenneth Gilkes, also of the King's Regiment.

Early in the operation, 7 Column shadowed Wingate and his Brigade Head Quarters and Sgt. Fitton remained with Gilkes' unit up until the orders were received to return to India. On the 29th March 1943, Wingate's HQ, Chindit Columns 7 and 8 and Northern Group's Head Quarters were all gathered on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River close to the Burmese village of Inywa.

A bridgehead party was formed and began crossing the mile wide river in hired country boats, which were manned and piloted by local Burmese villagers. A Japanese patrol on the western banks opened up on the leading boats with machine gun and mortar fire and many casualties were inflicted on the Chindits attempting to cross the river. Wingate and his column commanders decided to abandon the crossing and moved back in to the scrub jungle close to the riverside. Eventually, the orders were given for the various columns to split up and Wingate sent Scott and Gilkes away from the area around Inywa.

At some point during the confusion at Inywa, Sergeant Fitton was separated from 7 Column and joined up with Northern Group Head Quarters and 8 Column who had decided to amalgamate their number for the return journey to India. By the 3rd April and with the help of RAF dinghies dropped to the men from the supply planes of 31 Squadron, the large force led by Major Scott was over the Shweli River and once again heading for banks of the Irrawaddy, but this time much further to the north.

Over the next few weeks the Chindits investigated many possible crossing points, but were always foiled in some way or another in acquiring the means to traverse the mile wide watery obstacle. The Japanese, now completely aware of the Chindits intentions had removed all boats from the banks of the river and now patrolled the waters in motor launches between the villages of Zinbon and Myale. Tony Aubrey, in his book 'With Wingate in Burma', summed up those desperate days:

"We saw and heard nothing of the enemy. But, always on our left, lurking like some inescapable monster, lay the implacable Irrawaddy. It had begun to be almost an obsession with us now, this river. There it lay, flowing calmly and serenely southwards. But, however much water flowed down, there was always enough left to act as a seemingly impassible barrier between ourselves and home. It had assumed a personality. I was surprised that I didn't dream about it at night."

Then, on the 20th April, Major Scott noticed a Burmese junk making its way down river close to where the Chindits were lying up. He seized his chance and with the assistance of Lieutenant George Borrow and Havildar Lanval of the Burma Rifles, hijacked the boat. Paying the junks owner handsomely in silver rupees, the column were over the river in just less than ninety minutes. Hurriedly, the Chindits melted away into the scrub jungle on the far bank and headed north-west.

Seen below is a map of the Irrawaddy around the area of Zinbon, the crossing point for 8 Column and Northern Group HQ on the 20th April 1943. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Being across the river was not the end of 8 Column's troubles. It had been roughly eight weeks since the Chindits first entered enemy territory and the trials of the operation were now beginning to take their toll on the exhausted and hungry men. Over the following few days, Major Scott's group marched in a north-westerly direction towards the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway line. Some soldiers were now running on empty and began to drop out of the line of march. Worried comrades tried in vain to persuade their mates to keep going, but for many this was the end of the road and they lay down on the trackside and drifted into their last long sleep.

On the 25th April the Chindits luck changed for the better. Close to the Burmese village of Sonpu they stumbled across a large open meadow, which by good fortune was the very spot Major Scott had chosen two days previously to take his next supply drop.

Once again Tony Aubrey takes up the story:

That evening, we were drawing near the place which Major Scott had given as the place for the dropping from the air. The jungle was thick here, and it looked as though we might have difficulty, first, in contacting the plane, and second, in retrieving what they dropped. It looked as though the spot chosen without knowledge of the country and only from our maps which were not perfect, was to turn out to be by no means an ideal one.

However, the luck of the Scott's held good. About 6.30, we suddenly emerged from thick jungle to find ourselves on the edge of a clearing. It was like coming out of the densest wood on to the middle of an English meadow. There was not even scrub growing in this clearing, just short grass. There was one thought in all our minds. Tommy Vann, as usual, put it into words. "Bring on the ruddy Air Force!" he said. It was hard to believe that this open space had not been made by hands. It was in the shape of an enormous T. We were standing at the foot of the upright, which was 400 yards wide and 1200 yards long. The stroke was 300 yards wide and 800 yards long. It was a perfect natural aerodrome.

After two days of communication with the RAF, a Dakota rescue plane landed on the jungle clearing and it was during this incident that Sgt. Bert Fitton came to prominence. To read in more detail about the rescue and the men who were saved by the bravery of the RAF Pilot who landed the Dakota, please click on the following link: Lance Corporal Fred Nightingale

Major Scott decided that the sick and wounded should be flown out first. After consulting the Pilot, Flying Officer Michael Vlasto on how many men could be transported on the first flight back to India, Scott selected eighteen men, including Lieutenant-Colonel S.A. Cooke who was suffering from dysentery and some acute and festering jungle sores. Bert Fitton had been helping the men board the plane when suddenly the cargo doors were slammed shut and the engines began to roar in preparation for take off.

Sgt. Fitton pleaded with the crew members in the hold to stop the plane and let him out. Back on the ground he told Major Scott, 'I came in on my feet and I'd like to go out the same way.' Scott smiled, 'Good man,' he said, and Fitton re-joined the column. As the crew scrambled into the plane the Chindits waved their hats three times and cheered silently through closed lips. The motors hummed and the door slammed to.

Michael Vlasto gripped the control column as the end of the field rushed towards his plane. The runway looked as though it was going to be too short and they were overloaded. With knuckles white and his face dripping with sweat, he pulled back on the stick and the plane staggered into the air, gently brushing the treetops as it climbed. 'God bless number eighteen,' he said, in reference to the man who had just asked to leave the plane.

Sadly No. 18, the incredibly brave and fine man that was Sergeant Bert Fitton, never made it out of Burma in 1943, he was lost just a few days later, killed in action during an ambush by a Japanese patrol at the Kaukkwe Chaung. It is in fact incorrect to nominate Bert Fitton as number eighteen in regards to the rescue plane incident at Sonpu; according to the personnel listing for those evacuated by the Dakota, there were 16 British soldiers aboard, together with one Gurkha Rifleman and one Burma Rifleman. So Sgt. Fitton would have actually been No. 19.

Many books written about the first Chindit Operation have recounted the incident at the Kaukkwe Chaung. Here is one such description from the book, 'Wingate's Lost Brigade', written by Phil Chinnery:

The next day, 30th April, was a fateful day for 8 Column. They reached the Kaukkwe Chaung, halting a mile south-east of the village of Okthaik. The men began crossing on two rafts that had been constructed out of lifebelts. The Burma Riflemen were across first and Havildar Lan Val went into Okthaik and arranged for the headman to guide them on to Pumhpyu. The bridgehead expanded as more men crossed the river and a heavy thunderstorm began as the column started to form up.

Unknown to the drenched Chindits, a strong enemy force had crept up under cover of the storm and heavy firing suddenly broke out around them. CQMS Duncan Bett was one of the men who retired to the cover of the river bank:

"On reaching the river bank, which was very high and steep, I sank over my knees in the mud with the weight of my pack, which weighed about seventy pounds. I was forced to slip it off and it rolled down the bank and disappeared in the muddy water with all my newly acquired food and gear. I was left with what I stood up in, a rifle and a bandolier of .303 ammunition."

Company Sergeant Major Cheevers reported to Major Scott that he had knocked out two Japanese machine-gun positions on the west side of the perimeter and the RSM was ordered to lead the dispersal groups off in that direction, keeping to the lower banks of the chaung. While this was taking place the Japanese put in a bayonet charge from the south, but they were driven back by 17 Platoon's Bren gun.

Lieutenant Rowland was hit in the chest and was last seen crawling towards the river bank. As Major Scott collected up the stragglers in the area he came across Colour Sergeant Robert Glasgow who had had his knee shattered. He refused all offers of help and asked Scott and others in the area to shoot him as he knew the Japanese would not bother to take him prisoner if he was unable to walk.

Scott told him to lie low until darkness, but Glasgow told the Column Commander not to bother coming back for him as he intended finishing himself off. He was never seen again. At this point the Burma Rifles were seen in the chaung, trying to swim back to the far bank. Two Japanese then appeared on the top of the bank and began dropping grenades into the water. These two were shot by Sergeant Delaney before he too joined the Major and the rest of the column and they melted away into the jungle.

The firing died away but flared up again fifteen minutes later from the direction of Okthaik village where some of the scattered Chindits had made contact with the Japs again. In the meantime Major Scott and his party put five miles of jungle between themselves and the chaung and then bivouacked for the night. They discovered that out of the fifty-seven men in the party, only seven had kept their packs. The bulk of the supplies dropped to the column a day or two earlier at Sonpu had been lost during the fighting.

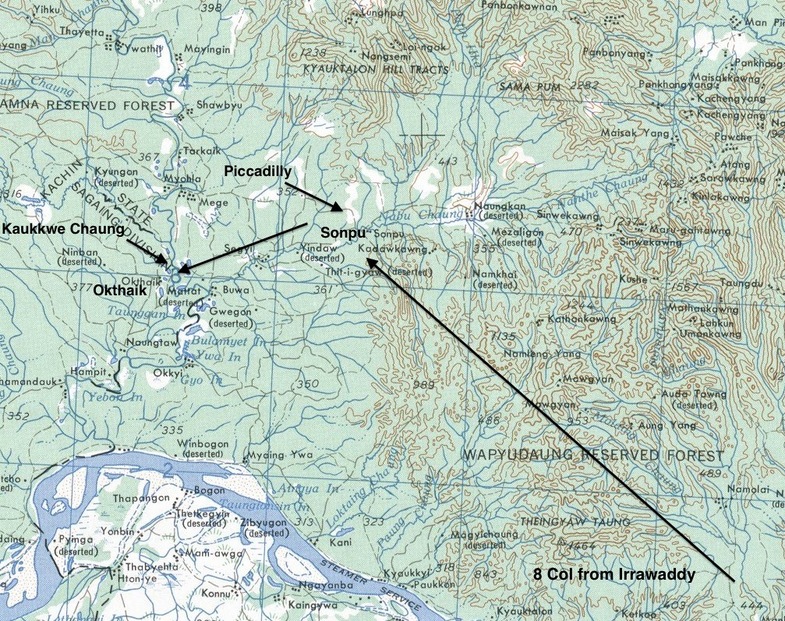

Seen below is a map of the area firstly, around the village of Sonpu showing the position of the large jungle clearing (later to be nicknamed Piccadilly) and then the location of the Kaukkwe Chaung situated close to the village of Okthaik.

On the 25th April the Chindits luck changed for the better. Close to the Burmese village of Sonpu they stumbled across a large open meadow, which by good fortune was the very spot Major Scott had chosen two days previously to take his next supply drop.

Once again Tony Aubrey takes up the story:

That evening, we were drawing near the place which Major Scott had given as the place for the dropping from the air. The jungle was thick here, and it looked as though we might have difficulty, first, in contacting the plane, and second, in retrieving what they dropped. It looked as though the spot chosen without knowledge of the country and only from our maps which were not perfect, was to turn out to be by no means an ideal one.

However, the luck of the Scott's held good. About 6.30, we suddenly emerged from thick jungle to find ourselves on the edge of a clearing. It was like coming out of the densest wood on to the middle of an English meadow. There was not even scrub growing in this clearing, just short grass. There was one thought in all our minds. Tommy Vann, as usual, put it into words. "Bring on the ruddy Air Force!" he said. It was hard to believe that this open space had not been made by hands. It was in the shape of an enormous T. We were standing at the foot of the upright, which was 400 yards wide and 1200 yards long. The stroke was 300 yards wide and 800 yards long. It was a perfect natural aerodrome.

After two days of communication with the RAF, a Dakota rescue plane landed on the jungle clearing and it was during this incident that Sgt. Bert Fitton came to prominence. To read in more detail about the rescue and the men who were saved by the bravery of the RAF Pilot who landed the Dakota, please click on the following link: Lance Corporal Fred Nightingale

Major Scott decided that the sick and wounded should be flown out first. After consulting the Pilot, Flying Officer Michael Vlasto on how many men could be transported on the first flight back to India, Scott selected eighteen men, including Lieutenant-Colonel S.A. Cooke who was suffering from dysentery and some acute and festering jungle sores. Bert Fitton had been helping the men board the plane when suddenly the cargo doors were slammed shut and the engines began to roar in preparation for take off.

Sgt. Fitton pleaded with the crew members in the hold to stop the plane and let him out. Back on the ground he told Major Scott, 'I came in on my feet and I'd like to go out the same way.' Scott smiled, 'Good man,' he said, and Fitton re-joined the column. As the crew scrambled into the plane the Chindits waved their hats three times and cheered silently through closed lips. The motors hummed and the door slammed to.

Michael Vlasto gripped the control column as the end of the field rushed towards his plane. The runway looked as though it was going to be too short and they were overloaded. With knuckles white and his face dripping with sweat, he pulled back on the stick and the plane staggered into the air, gently brushing the treetops as it climbed. 'God bless number eighteen,' he said, in reference to the man who had just asked to leave the plane.

Sadly No. 18, the incredibly brave and fine man that was Sergeant Bert Fitton, never made it out of Burma in 1943, he was lost just a few days later, killed in action during an ambush by a Japanese patrol at the Kaukkwe Chaung. It is in fact incorrect to nominate Bert Fitton as number eighteen in regards to the rescue plane incident at Sonpu; according to the personnel listing for those evacuated by the Dakota, there were 16 British soldiers aboard, together with one Gurkha Rifleman and one Burma Rifleman. So Sgt. Fitton would have actually been No. 19.

Many books written about the first Chindit Operation have recounted the incident at the Kaukkwe Chaung. Here is one such description from the book, 'Wingate's Lost Brigade', written by Phil Chinnery:

The next day, 30th April, was a fateful day for 8 Column. They reached the Kaukkwe Chaung, halting a mile south-east of the village of Okthaik. The men began crossing on two rafts that had been constructed out of lifebelts. The Burma Riflemen were across first and Havildar Lan Val went into Okthaik and arranged for the headman to guide them on to Pumhpyu. The bridgehead expanded as more men crossed the river and a heavy thunderstorm began as the column started to form up.

Unknown to the drenched Chindits, a strong enemy force had crept up under cover of the storm and heavy firing suddenly broke out around them. CQMS Duncan Bett was one of the men who retired to the cover of the river bank:

"On reaching the river bank, which was very high and steep, I sank over my knees in the mud with the weight of my pack, which weighed about seventy pounds. I was forced to slip it off and it rolled down the bank and disappeared in the muddy water with all my newly acquired food and gear. I was left with what I stood up in, a rifle and a bandolier of .303 ammunition."

Company Sergeant Major Cheevers reported to Major Scott that he had knocked out two Japanese machine-gun positions on the west side of the perimeter and the RSM was ordered to lead the dispersal groups off in that direction, keeping to the lower banks of the chaung. While this was taking place the Japanese put in a bayonet charge from the south, but they were driven back by 17 Platoon's Bren gun.

Lieutenant Rowland was hit in the chest and was last seen crawling towards the river bank. As Major Scott collected up the stragglers in the area he came across Colour Sergeant Robert Glasgow who had had his knee shattered. He refused all offers of help and asked Scott and others in the area to shoot him as he knew the Japanese would not bother to take him prisoner if he was unable to walk.

Scott told him to lie low until darkness, but Glasgow told the Column Commander not to bother coming back for him as he intended finishing himself off. He was never seen again. At this point the Burma Rifles were seen in the chaung, trying to swim back to the far bank. Two Japanese then appeared on the top of the bank and began dropping grenades into the water. These two were shot by Sergeant Delaney before he too joined the Major and the rest of the column and they melted away into the jungle.

The firing died away but flared up again fifteen minutes later from the direction of Okthaik village where some of the scattered Chindits had made contact with the Japs again. In the meantime Major Scott and his party put five miles of jungle between themselves and the chaung and then bivouacked for the night. They discovered that out of the fifty-seven men in the party, only seven had kept their packs. The bulk of the supplies dropped to the column a day or two earlier at Sonpu had been lost during the fighting.

Seen below is a map of the area firstly, around the village of Sonpu showing the position of the large jungle clearing (later to be nicknamed Piccadilly) and then the location of the Kaukkwe Chaung situated close to the village of Okthaik.

In the Missing in Action listings for 7 Column, Sgt. Fitton's entry reads simply: 'Killed in action-30/04/1943'. There are two surviving witness statements that describe the death of Bert Fitton; one from Corporal T. Walsh of 8 Column and the other from Pte. W. Greenhalgh, also of 8 Column in 1943.

Corporal 3781734 Walsh stated:

I was a member of 8 Column during Wingate's Burma expedition. On May 1st at Okthaik we were attacked in the afternoon by the Japanese during our march out of Burma. At about 1830 hours, after the battle was over I was leading a party of men out of the area, when I came across Sgt. Fitton lying against a tree on the river bank. He had been hit in the chest and had been bleeding from the mouth. I am quite sure he was dead.

Pte. 3776236 W. Greenhalgh stated on the 24th July 1943:

I was a member of the Support Platoon of No. 8 Column during Brigadier Wingate's Burma Expedition. On May 1st 1943 we were attacked by the Japanese. I was near to Sgt. Fitton in a firing position and at about 1600 hours I saw the Sergeant hit in the chest and he went down. I was wounded in the arm and moved out of the area. Later in the afternoon, at about 1730 hours I passed by the same way and saw Sgt. Fitton still in the same position; I am sure that he was dead.

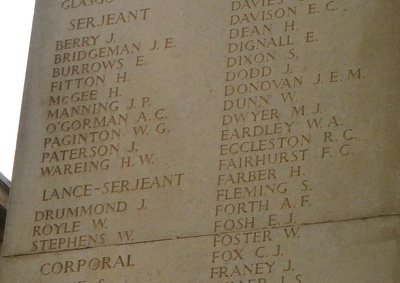

Sadly, Bert's body was never recovered after the war and for this reason he is remembered upon the Rangoon Memorial, located at Taukkyan War Cemetery. This memorial is the centre piece structure of the entire cemetery grounds and contains the names of some 27,000 casualties from the Burma campaign who have 'no known grave'. To view Bert Fitton's CWGC details, please click on the link below:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/1292591/FITTON,%20HERBERT

Former 7 Column soldier, Pte. Charles Aves remembered his good friend Bert Fitton, as part of his audio memoir, which he recorded at the Imperial War Museum in June 1995. Charles, who was one of the few men from 7 Column to gain the western banks of the Irrawaddy during the contested crossing at Inywa on the 29th March 1943 and then make it back to India.

He spoke fondly about his comrade during the final part of his recording:

"Corporal Bert Fitton, left half C' Company football team. Helped Lieutenant-Colonel Cooke and the sick and the wounded on to the only get out plane. Found himself locked in and about to take off. Pleaded with the pilot to let him out, he was killed a short time later. I wonder if his family ever knew about the Dakota incident and that he might of escaped back to India? I was on patrol with him once in the jungle, just he and I. He was just too brave for me and I had tears when I heard of his death."

Seen below is a final gallery of images in relation to the story of Sgt. Bert Fitton, including his inscription upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Corporal 3781734 Walsh stated:

I was a member of 8 Column during Wingate's Burma expedition. On May 1st at Okthaik we were attacked in the afternoon by the Japanese during our march out of Burma. At about 1830 hours, after the battle was over I was leading a party of men out of the area, when I came across Sgt. Fitton lying against a tree on the river bank. He had been hit in the chest and had been bleeding from the mouth. I am quite sure he was dead.

Pte. 3776236 W. Greenhalgh stated on the 24th July 1943:

I was a member of the Support Platoon of No. 8 Column during Brigadier Wingate's Burma Expedition. On May 1st 1943 we were attacked by the Japanese. I was near to Sgt. Fitton in a firing position and at about 1600 hours I saw the Sergeant hit in the chest and he went down. I was wounded in the arm and moved out of the area. Later in the afternoon, at about 1730 hours I passed by the same way and saw Sgt. Fitton still in the same position; I am sure that he was dead.

Sadly, Bert's body was never recovered after the war and for this reason he is remembered upon the Rangoon Memorial, located at Taukkyan War Cemetery. This memorial is the centre piece structure of the entire cemetery grounds and contains the names of some 27,000 casualties from the Burma campaign who have 'no known grave'. To view Bert Fitton's CWGC details, please click on the link below:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/1292591/FITTON,%20HERBERT

Former 7 Column soldier, Pte. Charles Aves remembered his good friend Bert Fitton, as part of his audio memoir, which he recorded at the Imperial War Museum in June 1995. Charles, who was one of the few men from 7 Column to gain the western banks of the Irrawaddy during the contested crossing at Inywa on the 29th March 1943 and then make it back to India.

He spoke fondly about his comrade during the final part of his recording:

"Corporal Bert Fitton, left half C' Company football team. Helped Lieutenant-Colonel Cooke and the sick and the wounded on to the only get out plane. Found himself locked in and about to take off. Pleaded with the pilot to let him out, he was killed a short time later. I wonder if his family ever knew about the Dakota incident and that he might of escaped back to India? I was on patrol with him once in the jungle, just he and I. He was just too brave for me and I had tears when I heard of his death."

Seen below is a final gallery of images in relation to the story of Sgt. Bert Fitton, including his inscription upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, December 2015. Dedicated to one of the bravest soldiers from the story of Operation Longcloth.