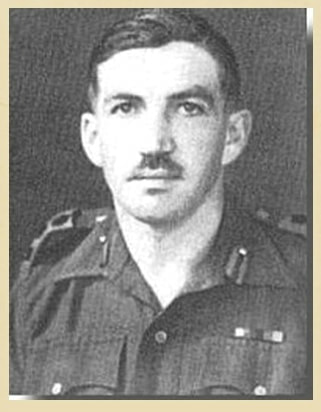

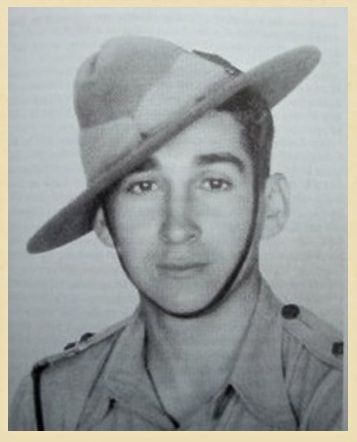

Sergeant-Major Robert Blain

Cap badge of the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders.

Cap badge of the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders.

In March 1944, five gliders loaded with a patrol of Chindits landed at night in an area north of Mandalay. The patrol was led by a young Scottish Major who had risen from the ranks. He had been a favourite of Wingate's from the year before. He looked like a playboy and was a great entertainer who played piano and loved to sing songs, especially the regimental reels of the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders. In action, he was one of the toughest men you will ever see.

Robert Strachan Blain was born during the years of the Great War in the Scottish village of Luss, situated on the western banks of Loch Lomond. Robert had enlisted into the Argyll's at the start of WW2 and had progressed rapidly through the ranks. He was part of the BEF in 1940 and was fortunate to be lifted from the beaches of Dunkirk that same summer, he later became a commando and served in operations against the German Army in both France and Norway.

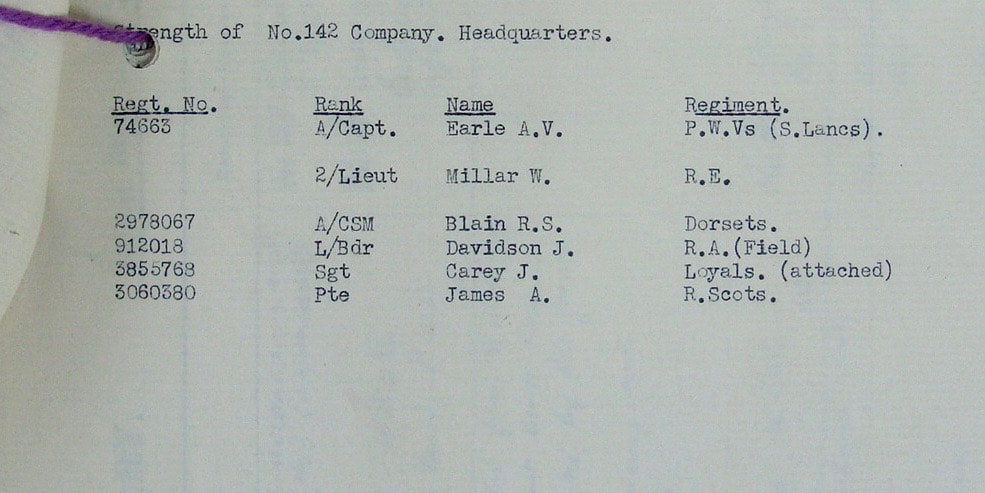

In 1942 he was attached to the Dorset Regiment holding the rank of Sergeant and posted to India. He arrived at the Saugor training camp and was sent over to the ranks of 142 Commando now under the command of Major Mike Calvert of the Royal Engineers. He settled down with his new unit working with and training men in the art of demolitions and the laying of booby-traps. On the 6th January 1943, Robert was promoted to Sergeant-Major (WOII) and took charge of training at the company Head Quarters.

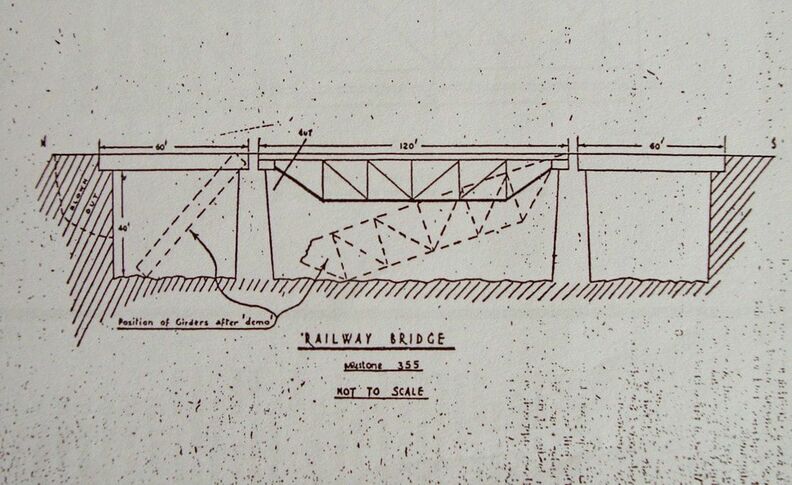

For the purposes of Operation Longcloth, CSM Blain was co-opted to the Commando Platoon of No. 3 Column under the command of Lt. Jeffrey Lockett formerly of the Seaforth Highlanders. Here he led the demolition squad and was responsible for the destruction of the railway bridge at the village of Nankan, No. 3 Column's main target during the first Wingate expedition.

From the book, Wingate's Raiders, written by Charles J. Rolo:

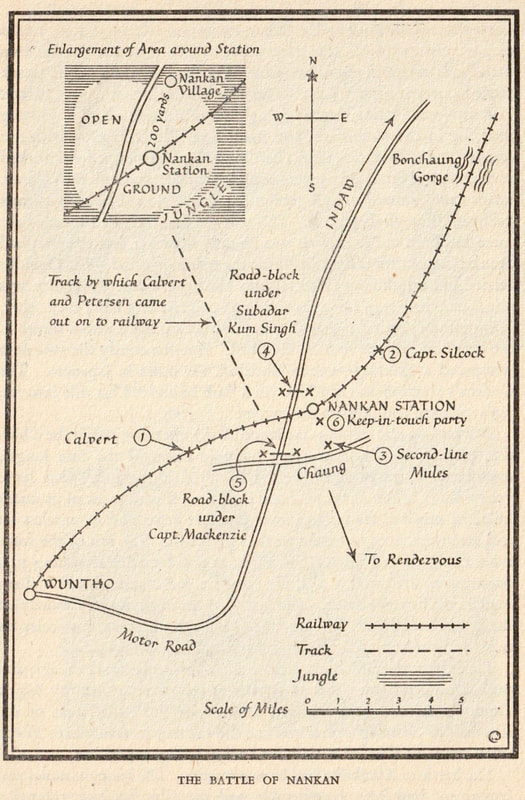

Nankan station was completely deserted when 3 Column arrived. All around were scattered teak logs and other debris from the 1942 retreat; magazine pouches, cans, smashed equipment and one rusty crippled jeep. On a siding stood trucks riddled with bullet-holes and a blown up locomotive rested grotesquely on its side. The station was situated in a small area of completely open ground. Two hundred yards north of it, surrounded by jungle palms, was a Burmese village. The Japanese were based in some strength at Indaw, twenty-five miles to the north and Wuntho, ten miles to the south. The new motor road from Indaw to Wuntho cut across the railway line just beside the station. Calvert fixed a rendezvous several miles to the south-east of the railway, then set his men to the demolitions.

The main task of blowing the bridge at Nankan was given to CSM Robert Blain. He was a wit and a philosopher, but suffered from a slight stammer. By way of compensation, nature had given him a wonderful singing voice, which he employed at any given opportunity, with Schubert's Ave Maira being his favourite piece. He had an uncanny ear for the tread of Japanese patrols and would deal with these poor wretches with murderous fire from his Tommy gun. He had a low opinion of the enemy and their talents for shooting, he recalled: "One day in 1943 I was moving through the jungle when all of a sudden two Japanese appeared on the track just ten yards in front of me. They opened fire, but all their bullets fell some five yards short. It was the most terrible display of shooting I have ever seen, if any of my chaps shot like that, I would put them under arrest."

Food was the Chindits only recreation in 1943. They ate rice in every possible way, mixed with dates, with raisins, with chocolate and with cheese. Of the British troops Sergeant-Major Blain and Sergeant-Major Chivers, a veteran of the siege of Tobruk, were the most enterprising cooks. Their favourite concoction was chocolate pudding, this was chocolate and digestive biscuits ground up into a mess tin with powdered milk and a little water added. After one supply drop in which they received some curry powder, they made a porridge of biscuits and cheese and then curried it.

There was no doubting the passion with which Robert Blain carried out his Chindit duties. As the Chindit columns prepared to cross the Chindwin River in mid-February 1943, Brigadier Wingate had released his Order of the Day. Lieutenant Jeffrey Lockett, the officer in charge of No. 3 Column Commando recalled this moment in his personal memoir for Operation Longcloth:

The day after we had crossed the Chindwin, I saw for the first time Orde Wingate's order of the day. I passed it round the Commando Section, and as I only had one copy, they each read in turn. Finally, I handed it to Sergeant-Major Blain. He read it and burst into tears. Why, I don't know. Blain was a regular soldier about 37 years old and had been court-martialled five times in his career, and here he was crying!

Robert Strachan Blain was born during the years of the Great War in the Scottish village of Luss, situated on the western banks of Loch Lomond. Robert had enlisted into the Argyll's at the start of WW2 and had progressed rapidly through the ranks. He was part of the BEF in 1940 and was fortunate to be lifted from the beaches of Dunkirk that same summer, he later became a commando and served in operations against the German Army in both France and Norway.

In 1942 he was attached to the Dorset Regiment holding the rank of Sergeant and posted to India. He arrived at the Saugor training camp and was sent over to the ranks of 142 Commando now under the command of Major Mike Calvert of the Royal Engineers. He settled down with his new unit working with and training men in the art of demolitions and the laying of booby-traps. On the 6th January 1943, Robert was promoted to Sergeant-Major (WOII) and took charge of training at the company Head Quarters.

For the purposes of Operation Longcloth, CSM Blain was co-opted to the Commando Platoon of No. 3 Column under the command of Lt. Jeffrey Lockett formerly of the Seaforth Highlanders. Here he led the demolition squad and was responsible for the destruction of the railway bridge at the village of Nankan, No. 3 Column's main target during the first Wingate expedition.

From the book, Wingate's Raiders, written by Charles J. Rolo:

Nankan station was completely deserted when 3 Column arrived. All around were scattered teak logs and other debris from the 1942 retreat; magazine pouches, cans, smashed equipment and one rusty crippled jeep. On a siding stood trucks riddled with bullet-holes and a blown up locomotive rested grotesquely on its side. The station was situated in a small area of completely open ground. Two hundred yards north of it, surrounded by jungle palms, was a Burmese village. The Japanese were based in some strength at Indaw, twenty-five miles to the north and Wuntho, ten miles to the south. The new motor road from Indaw to Wuntho cut across the railway line just beside the station. Calvert fixed a rendezvous several miles to the south-east of the railway, then set his men to the demolitions.

The main task of blowing the bridge at Nankan was given to CSM Robert Blain. He was a wit and a philosopher, but suffered from a slight stammer. By way of compensation, nature had given him a wonderful singing voice, which he employed at any given opportunity, with Schubert's Ave Maira being his favourite piece. He had an uncanny ear for the tread of Japanese patrols and would deal with these poor wretches with murderous fire from his Tommy gun. He had a low opinion of the enemy and their talents for shooting, he recalled: "One day in 1943 I was moving through the jungle when all of a sudden two Japanese appeared on the track just ten yards in front of me. They opened fire, but all their bullets fell some five yards short. It was the most terrible display of shooting I have ever seen, if any of my chaps shot like that, I would put them under arrest."

Food was the Chindits only recreation in 1943. They ate rice in every possible way, mixed with dates, with raisins, with chocolate and with cheese. Of the British troops Sergeant-Major Blain and Sergeant-Major Chivers, a veteran of the siege of Tobruk, were the most enterprising cooks. Their favourite concoction was chocolate pudding, this was chocolate and digestive biscuits ground up into a mess tin with powdered milk and a little water added. After one supply drop in which they received some curry powder, they made a porridge of biscuits and cheese and then curried it.

There was no doubting the passion with which Robert Blain carried out his Chindit duties. As the Chindit columns prepared to cross the Chindwin River in mid-February 1943, Brigadier Wingate had released his Order of the Day. Lieutenant Jeffrey Lockett, the officer in charge of No. 3 Column Commando recalled this moment in his personal memoir for Operation Longcloth:

The day after we had crossed the Chindwin, I saw for the first time Orde Wingate's order of the day. I passed it round the Commando Section, and as I only had one copy, they each read in turn. Finally, I handed it to Sergeant-Major Blain. He read it and burst into tears. Why, I don't know. Blain was a regular soldier about 37 years old and had been court-martialled five times in his career, and here he was crying!

Later on during the expedition, No. 3 Column crossed the Irrawaddy and continued their march eastwards in search of more adventure. About four days after crossing the river they reached the outskirts of a Burmese village called Pago. Here Lt. Harold James was ordered to lead his Gurkhas alongside CSM Blain and some of his Commandos and set an ambush for the Japanese on the tracks outside the village.

From the book Wingate's Raiders:

On March 22nd, Calvert cached four days' paratroop rations for each man against an emergency and moved off eastward. To the north he kept hearing the sound of heavy gunfire; it was Wingate's force fighting almost continual battles with the Japs. That evening Calvert's column reached the Nammit Chaung, which ran across the line of march to their next target. At dawn twelve Burma Rifles under a British Lieutenant waded the stream and cautiously approached a village, Pago, one and a half miles from Calvert's bivouac. Natives warned them that a patrol of sixty Japs was in the village, and two runners were sent back to Calvert.

On the way back the runners bumped into an enemy scouting party of about twenty men. One of them made a dash for it with the message, the other dodged behind a tree and at point-blank range coolly aimed twelve shots at the Japanese. Two dropped a few yards away from him, and he hadn't time to count how many more he had hit. When he turned up at the bivouac he reported two Japanese killed. Later Calvert's men discovered seven bodies on the trail.

Another patrol meanwhile had captured Japanese operational orders from a battalion to one of its companies that was hunting for Wingate's men. This, amplified by information from the villagers, gave Calvert a very clear picture of what paths the Japs were using and where their main forces were concentrated.

Calvert ordered Second Lieutenant James with two Gurkha sections and a British Tommy-gun section to lay an ambush on one of the trails along which a Japanese patrol was advancing. The ambush party had not been in position for more than an hour when they saw thirty-six Japs marching down a dust road. When Lieutenant James gave the order to fire Sergeant-Major Blain yelled out to the front Tommy-gun-man, " There you are, my boy, there's a birthday present for you."

The Japanese were taken completely by surprise. This wasn't in their book of rules, and they lost their heads. Instead of scattering, they dropped to their knees on the road and started firing blindly into the jungle in all directions. They were a sitting target. The first volley killed twenty of them. The survivors did the only thing the Japanese know how to do when they're caught off guard. They fixed bayonets and charged straight to their death. James picked off five of them with his rifle. His Tommy-gunners wiped out the rest. Not a single one escaped.

Other Japanese patrols, however, heard the sound of firing and closed in, this time with greater caution. Back in bivouac Calvert suddenly heard a voice in the jungle close by, calling, " Sergeant-Major, come over here." He held his fire, thinking it might possibly be someone hunting for Sergeant-Major Blain, but whispered to the men to keep a sharp look-out. A moment later they spotted a Japanese uniform, and Calvert ordered one platoon to make a bayonet sweep from the flank. The Japs let out a frightful yell when the Chindits suddenly piled on top of them with machetes and bayonets. The survivors dropped their equipment and ran.

At the close of Operation Longcloth, Lt. Lockett, commander of the Commando Platoon had this to say about his men:

I would like to record that throughout the Campaign the men worked very well as a team; their morale was always very high. They gained valuable experience and learnt many lessons in jungle warfare, besides learning the methods of fighting used by the Japanese, which will prove of great benefit when they go in again.

I should like to mention the following men: Company Sergeant-Major Blain, Sgt. Chivers and Lance Corporal Cockling, who all did excellent work and showed real initiative and leadership throughout. Corporal Day, who showed great coolness and courage in blowing a bridge whilst under fire on the 6th March and Pte. Guest, who in the action at the Irrawaddy on the 14th March, went back and rescued several mules and other valuable equipment.

From the book Wingate's Raiders:

On March 22nd, Calvert cached four days' paratroop rations for each man against an emergency and moved off eastward. To the north he kept hearing the sound of heavy gunfire; it was Wingate's force fighting almost continual battles with the Japs. That evening Calvert's column reached the Nammit Chaung, which ran across the line of march to their next target. At dawn twelve Burma Rifles under a British Lieutenant waded the stream and cautiously approached a village, Pago, one and a half miles from Calvert's bivouac. Natives warned them that a patrol of sixty Japs was in the village, and two runners were sent back to Calvert.

On the way back the runners bumped into an enemy scouting party of about twenty men. One of them made a dash for it with the message, the other dodged behind a tree and at point-blank range coolly aimed twelve shots at the Japanese. Two dropped a few yards away from him, and he hadn't time to count how many more he had hit. When he turned up at the bivouac he reported two Japanese killed. Later Calvert's men discovered seven bodies on the trail.

Another patrol meanwhile had captured Japanese operational orders from a battalion to one of its companies that was hunting for Wingate's men. This, amplified by information from the villagers, gave Calvert a very clear picture of what paths the Japs were using and where their main forces were concentrated.

Calvert ordered Second Lieutenant James with two Gurkha sections and a British Tommy-gun section to lay an ambush on one of the trails along which a Japanese patrol was advancing. The ambush party had not been in position for more than an hour when they saw thirty-six Japs marching down a dust road. When Lieutenant James gave the order to fire Sergeant-Major Blain yelled out to the front Tommy-gun-man, " There you are, my boy, there's a birthday present for you."

The Japanese were taken completely by surprise. This wasn't in their book of rules, and they lost their heads. Instead of scattering, they dropped to their knees on the road and started firing blindly into the jungle in all directions. They were a sitting target. The first volley killed twenty of them. The survivors did the only thing the Japanese know how to do when they're caught off guard. They fixed bayonets and charged straight to their death. James picked off five of them with his rifle. His Tommy-gunners wiped out the rest. Not a single one escaped.

Other Japanese patrols, however, heard the sound of firing and closed in, this time with greater caution. Back in bivouac Calvert suddenly heard a voice in the jungle close by, calling, " Sergeant-Major, come over here." He held his fire, thinking it might possibly be someone hunting for Sergeant-Major Blain, but whispered to the men to keep a sharp look-out. A moment later they spotted a Japanese uniform, and Calvert ordered one platoon to make a bayonet sweep from the flank. The Japs let out a frightful yell when the Chindits suddenly piled on top of them with machetes and bayonets. The survivors dropped their equipment and ran.

At the close of Operation Longcloth, Lt. Lockett, commander of the Commando Platoon had this to say about his men:

I would like to record that throughout the Campaign the men worked very well as a team; their morale was always very high. They gained valuable experience and learnt many lessons in jungle warfare, besides learning the methods of fighting used by the Japanese, which will prove of great benefit when they go in again.

I should like to mention the following men: Company Sergeant-Major Blain, Sgt. Chivers and Lance Corporal Cockling, who all did excellent work and showed real initiative and leadership throughout. Corporal Day, who showed great coolness and courage in blowing a bridge whilst under fire on the 6th March and Pte. Guest, who in the action at the Irrawaddy on the 14th March, went back and rescued several mules and other valuable equipment.

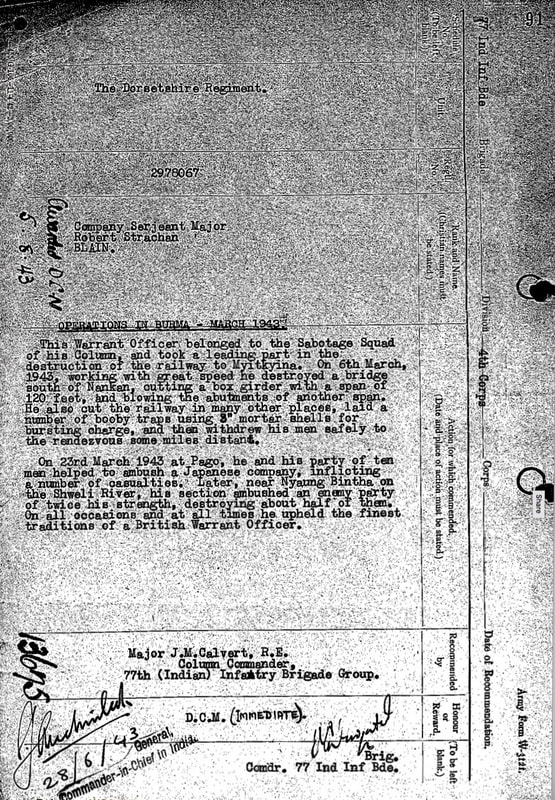

For his efforts during the first Wingate expedition, Robert Blain was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal:

Brigade-77th Indian Infantry Brigade

Corps-4th Corps

Unit-The Dorset Regiment attached 13th Battalion, the King's (Liverpool)

Regimental number-2978067

Rank and Name-Company Sergeant-Major Robert Strachan Blain

Action for which recommended :-

OPERATIONS IN BURMA - MARCH 1943

This Warrant Officer belonged to the Sabotage Squad of his Column, and took a leading part in the destruction of the railway to Myitkhina. On 6th March, 1943, working with great speed he destroyed a bridge south of Nankan, cutting a box girder with a span of 120 feet, and blowing the abutments of another span. He also cut the railway in many other places, laid a number of booby traps using 3" mortar shells for bursting charge, and then withdrew his men safely to rendezvous some miles distant.

On 23rd March 1943 at Pago, he and his party of ten men helped to ambush a Japanese company, inflicting a number of casualties. Later, near Nyaungbintha on the Shweli River, his section ambushed an enemy party of twice his strength, destroying about half of them. On all occasions and at all times he upheld the finest traditions of a British Warrant Officer.

Recommended By: Major J.M. Calvert, R.E.

Column Commander, 77th (Indian) Infantry Brigade Group

Honour or Reward-D.C.M. (Immediate).

Signed By-Brigadier O.C. Wingate, Commander 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

(London Gazette 05.08.1943).

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this section of the story. Please click on any images to bring it forward on the page.

Brigade-77th Indian Infantry Brigade

Corps-4th Corps

Unit-The Dorset Regiment attached 13th Battalion, the King's (Liverpool)

Regimental number-2978067

Rank and Name-Company Sergeant-Major Robert Strachan Blain

Action for which recommended :-

OPERATIONS IN BURMA - MARCH 1943

This Warrant Officer belonged to the Sabotage Squad of his Column, and took a leading part in the destruction of the railway to Myitkhina. On 6th March, 1943, working with great speed he destroyed a bridge south of Nankan, cutting a box girder with a span of 120 feet, and blowing the abutments of another span. He also cut the railway in many other places, laid a number of booby traps using 3" mortar shells for bursting charge, and then withdrew his men safely to rendezvous some miles distant.

On 23rd March 1943 at Pago, he and his party of ten men helped to ambush a Japanese company, inflicting a number of casualties. Later, near Nyaungbintha on the Shweli River, his section ambushed an enemy party of twice his strength, destroying about half of them. On all occasions and at all times he upheld the finest traditions of a British Warrant Officer.

Recommended By: Major J.M. Calvert, R.E.

Column Commander, 77th (Indian) Infantry Brigade Group

Honour or Reward-D.C.M. (Immediate).

Signed By-Brigadier O.C. Wingate, Commander 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

(London Gazette 05.08.1943).

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this section of the story. Please click on any images to bring it forward on the page.

Sergeant-Major Blain's performance on Operation Longcloth did not go unnoticed. In 1944, he was given command of a special squad of Royal Engineers and commandos codenamed Bladet Force. This comprised five officers and sixty men and was to be used for duties such as sabotage and reconnaissance wherever they were deemed necessary. The unit's one and only action during the second Wingate expedition (Operation Thursday) came on the 19th March, when it was landed at night west of the Irrawaddy River in five Waco Gliders.

From the book, March or Die, by Phil Chinnery:

The detachment’s first and only action began in the third week of March, when it landed on a paddy field landing strip hastily prepared by some Gurkhas from 111th Brigade. Lt. Stewart Binnie, Major Blain’s second in command recalled:

The landing was a successful shambles. The gliders were piloted by Americans from Cochran's Air Commandos. The first glider with Blain and myself in it overshot the strip and tore into the jungle, shedding its wings and splitting open through the length of the fuselage. The troops within were able to step out of the wreckage, alarmed but relatively unharmed. The remaining gliders performed with equal acrobatic flair and the one carrying the mules actually looped the loop very near the ground, pancake-landed and the mules walked daintily out over the wreckage and calmly started to graze.

The unit bivouacked for the night in nearby jungle, the bivouac including the American pilots who were to be flown out by light plane at first light. They were very unused to jungle and I don't think they slept much, seeing lions, tigers and Japs everywhere. During the night, Blain realised that he had been injured in the glider crash and was incapable of undertaking a long march in enemy territory. He was therefore to go back with the American pilots and I, by chance the senior Lieutenant, took over command. This was, initially quite a shock, as apart from CSM Chivers and a couple of engineers, the remainder of the detachment were new to action and it had been anticipated that Blain's experience would be essential to the success of the operation. I was fortunate in having CSM Chivers to lean on throughout the patrol, as he had been with Blain in the first expedition and was an excellent Wingate-type soldier.

Anyway, the troops were of good quality and my fellow officers were keen and enthusiastic. We set about our objective to reach a bridge over the railway near Kawlin on the Mandalay—Myitkhina line, blow it up, make a mess of the railway line and throughout the patrol give the impression to native Burmese — knowing that the information would be passed to the Japs — that there was a biggish Chindit force this far south.

The operation took about six weeks and was a success. We blew the bridge and a nearby pumping station and cut the railway line in several places. During the patrol the mule carrying the wireless set went over a cliff, falling about 200 feet, and we were incommunicado for most of the patrol. Eventually the wireless was resuscitated enough to permit contact with India and we arranged one supply drop without which we would probably have perished. We were congratulated by Wingate just before his untimely death and told to move on to Aberdeen, one of the Chindit landing strip strongholds. This was quite a hike and we became very exhausted and hungry. A period of marching through a dry belt very nearly caused madness due to thirst and one got to the stage of planning the murder of one's best friend for the sake of the small residue he might have in his water bottle.

At one stage we got lost and hunger and thirst were so affecting us that it was proposed by CSM Chivers that we should take a free vote as to whether we should go on looking for Aberdeen, or allow small groups to go it alone and head back over the Chindwin for India. I think that Chivers felt that having done it himself before, he could do it again. Fortunately the problem was solved by the sudden appearance of two Gurkha soldiers at the fringe of the jungle. Our saviours were in bivouac about a quarter of a mile away in the form of, Tim Brennan's Cameronians, the King's Own and a couple of columns of Gurkhas. We were made very welcome, fed with bully beef and peaches and cream until we were sick, and allowed to sleep the sleep of the just.

Tim Brennan got a message that we were to move on, when ready, to Aberdeen and be flown out as we were too exhausted to participate in any further action. A day's rest and we were on our way. We were ambushed by some excitable Japs a short distance away from the bivouac, but they were as anxious as we were and we escaped with one engineer shot through the kneecap and John Urquhart, my second-in-command, with a bullet burn right across his left breast, lucky fellow, shaken but intact. Two days of tough marching saw us in Aberdeen, happy but very, very exhausted.

We eventually arrived in Shillong, in Assam, where we were to recuperate. Within twenty-four hours every single member of the unit was in hospital, after an enormous celebratory binge and suffering from malaria or dysentery. I was unconscious for three days with malignant tertian malaria. I thought the initial symptoms were merely those of a gigantic hangover. This extraordinary medical situation was of great interest to me after the war when I trained to become a general practitioner, and it wasn't understood until the discovery of cortisone how, in desperate states, our adrenal glands produce masses of it in an endeavour to keep infection at bay and maintain necessary bodily functions.

Bladet Force was disbanded at this stage and individuals returned to their parent units when their health was restored. I then had the dubious pleasure of being trained to command a small detachment of twelve man-pack flame throwers and soon took them into Mogaung to be used by Brigadier Calvert. We were used, I believe rather unskilfully, in a night attack on a village near Mogaung. However, although the tactics were discredited, their use was such a shock to the Japs that the village fell into Calvert's hands with minimal casualties to our attacking force. In this action I lost the sight of my right eye to shrapnel from a Jap grenade, one soldier was killed and the remaining ten soldiers were all wounded to some degree.

From the book, March or Die, by Phil Chinnery:

The detachment’s first and only action began in the third week of March, when it landed on a paddy field landing strip hastily prepared by some Gurkhas from 111th Brigade. Lt. Stewart Binnie, Major Blain’s second in command recalled:

The landing was a successful shambles. The gliders were piloted by Americans from Cochran's Air Commandos. The first glider with Blain and myself in it overshot the strip and tore into the jungle, shedding its wings and splitting open through the length of the fuselage. The troops within were able to step out of the wreckage, alarmed but relatively unharmed. The remaining gliders performed with equal acrobatic flair and the one carrying the mules actually looped the loop very near the ground, pancake-landed and the mules walked daintily out over the wreckage and calmly started to graze.

The unit bivouacked for the night in nearby jungle, the bivouac including the American pilots who were to be flown out by light plane at first light. They were very unused to jungle and I don't think they slept much, seeing lions, tigers and Japs everywhere. During the night, Blain realised that he had been injured in the glider crash and was incapable of undertaking a long march in enemy territory. He was therefore to go back with the American pilots and I, by chance the senior Lieutenant, took over command. This was, initially quite a shock, as apart from CSM Chivers and a couple of engineers, the remainder of the detachment were new to action and it had been anticipated that Blain's experience would be essential to the success of the operation. I was fortunate in having CSM Chivers to lean on throughout the patrol, as he had been with Blain in the first expedition and was an excellent Wingate-type soldier.

Anyway, the troops were of good quality and my fellow officers were keen and enthusiastic. We set about our objective to reach a bridge over the railway near Kawlin on the Mandalay—Myitkhina line, blow it up, make a mess of the railway line and throughout the patrol give the impression to native Burmese — knowing that the information would be passed to the Japs — that there was a biggish Chindit force this far south.

The operation took about six weeks and was a success. We blew the bridge and a nearby pumping station and cut the railway line in several places. During the patrol the mule carrying the wireless set went over a cliff, falling about 200 feet, and we were incommunicado for most of the patrol. Eventually the wireless was resuscitated enough to permit contact with India and we arranged one supply drop without which we would probably have perished. We were congratulated by Wingate just before his untimely death and told to move on to Aberdeen, one of the Chindit landing strip strongholds. This was quite a hike and we became very exhausted and hungry. A period of marching through a dry belt very nearly caused madness due to thirst and one got to the stage of planning the murder of one's best friend for the sake of the small residue he might have in his water bottle.

At one stage we got lost and hunger and thirst were so affecting us that it was proposed by CSM Chivers that we should take a free vote as to whether we should go on looking for Aberdeen, or allow small groups to go it alone and head back over the Chindwin for India. I think that Chivers felt that having done it himself before, he could do it again. Fortunately the problem was solved by the sudden appearance of two Gurkha soldiers at the fringe of the jungle. Our saviours were in bivouac about a quarter of a mile away in the form of, Tim Brennan's Cameronians, the King's Own and a couple of columns of Gurkhas. We were made very welcome, fed with bully beef and peaches and cream until we were sick, and allowed to sleep the sleep of the just.

Tim Brennan got a message that we were to move on, when ready, to Aberdeen and be flown out as we were too exhausted to participate in any further action. A day's rest and we were on our way. We were ambushed by some excitable Japs a short distance away from the bivouac, but they were as anxious as we were and we escaped with one engineer shot through the kneecap and John Urquhart, my second-in-command, with a bullet burn right across his left breast, lucky fellow, shaken but intact. Two days of tough marching saw us in Aberdeen, happy but very, very exhausted.

We eventually arrived in Shillong, in Assam, where we were to recuperate. Within twenty-four hours every single member of the unit was in hospital, after an enormous celebratory binge and suffering from malaria or dysentery. I was unconscious for three days with malignant tertian malaria. I thought the initial symptoms were merely those of a gigantic hangover. This extraordinary medical situation was of great interest to me after the war when I trained to become a general practitioner, and it wasn't understood until the discovery of cortisone how, in desperate states, our adrenal glands produce masses of it in an endeavour to keep infection at bay and maintain necessary bodily functions.

Bladet Force was disbanded at this stage and individuals returned to their parent units when their health was restored. I then had the dubious pleasure of being trained to command a small detachment of twelve man-pack flame throwers and soon took them into Mogaung to be used by Brigadier Calvert. We were used, I believe rather unskilfully, in a night attack on a village near Mogaung. However, although the tactics were discredited, their use was such a shock to the Japs that the village fell into Calvert's hands with minimal casualties to our attacking force. In this action I lost the sight of my right eye to shrapnel from a Jap grenade, one soldier was killed and the remaining ten soldiers were all wounded to some degree.

After the war Robert Blain returned to Scotland and looked to take up his old employment as a Tram Conductor for the Glasgow Transport Corporation. From the pages of the Glasgow Sunday Post dated 20th January 1946, comes this rather interesting article:

But He's A Major!

Major Blain DCM, was demobbed three months ago, after going right through the Burma campaign. He applied to Glasgow Corporation transport for a job. He was given his old one back, that of a tram conductor. Couldn't he get something better, something with prospects? he asked. No, he was told. He would have to start at the bottom. Fair enough, he agreed. He did not want preferential treatment because he'd been a Major.

Perhaps if he took his old job as a tram conductor, it might pave the way for a try-out in another field of Corporation activity. But nothing happened and a conductor he remained. So he began applying for jobs with prospects. He got interviews, but wherever he went he got the same reception: What! an ex-Major, sorry nothing for you here. He told them that all he wanted was a chance and that he would start at the bottom and was not afraid of hard work. But it was no use, owners of businesses made it clear they had nothing for ex-Majors.

Major Blain has now taken his fate into his own hands. He has bought a couple of cars and gone into the motor hire business in Airdrie. He will drive one car and his wife the other. Between them they will have a go at earning a decent living. There are a dozen other young men in Glasgow who were in the Burma show with the Major and all did well in the Army, but they are in the same boat today, nobody will give them a chance.

"We could all get decent jobs abroad in the police if we cared to, said Blain, but that sort of life only appeals to a few."

Major Blain joined the Army as a private in 1938 and was a Sergeant when war broke out. He won his commission in the field in Burma and reached the rank of Major just fourteen months later. The Sunday Post would be glad to hear from other ex-servicemen and learn of their difficulties in making a fresh start in Civvy Street. Their experiences can be of real service to others in the same boat and any letters used will be paid for. Write to: The Sunday Post, 144 Port Dundas Road, Glasgow.

But He's A Major!

Major Blain DCM, was demobbed three months ago, after going right through the Burma campaign. He applied to Glasgow Corporation transport for a job. He was given his old one back, that of a tram conductor. Couldn't he get something better, something with prospects? he asked. No, he was told. He would have to start at the bottom. Fair enough, he agreed. He did not want preferential treatment because he'd been a Major.

Perhaps if he took his old job as a tram conductor, it might pave the way for a try-out in another field of Corporation activity. But nothing happened and a conductor he remained. So he began applying for jobs with prospects. He got interviews, but wherever he went he got the same reception: What! an ex-Major, sorry nothing for you here. He told them that all he wanted was a chance and that he would start at the bottom and was not afraid of hard work. But it was no use, owners of businesses made it clear they had nothing for ex-Majors.

Major Blain has now taken his fate into his own hands. He has bought a couple of cars and gone into the motor hire business in Airdrie. He will drive one car and his wife the other. Between them they will have a go at earning a decent living. There are a dozen other young men in Glasgow who were in the Burma show with the Major and all did well in the Army, but they are in the same boat today, nobody will give them a chance.

"We could all get decent jobs abroad in the police if we cared to, said Blain, but that sort of life only appeals to a few."

Major Blain joined the Army as a private in 1938 and was a Sergeant when war broke out. He won his commission in the field in Burma and reached the rank of Major just fourteen months later. The Sunday Post would be glad to hear from other ex-servicemen and learn of their difficulties in making a fresh start in Civvy Street. Their experiences can be of real service to others in the same boat and any letters used will be paid for. Write to: The Sunday Post, 144 Port Dundas Road, Glasgow.

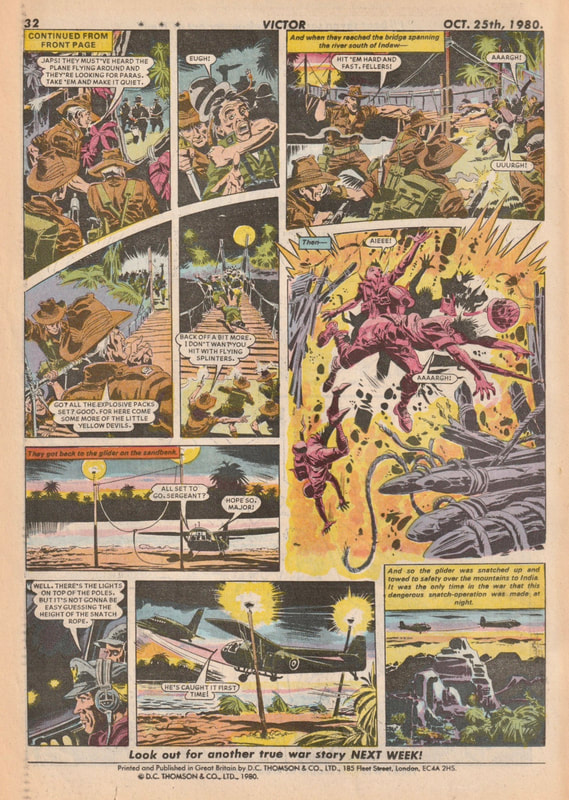

On the 25th October 1980, the writers of the comic, Victor, decided to use the wartime adventures of Major Robert Strachan Blain as part of their regular feature, A True Story of Men at War. Please click on the two images below to see and read their depiction of his time during the second Chindit expedition in 1944.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, February 2019.