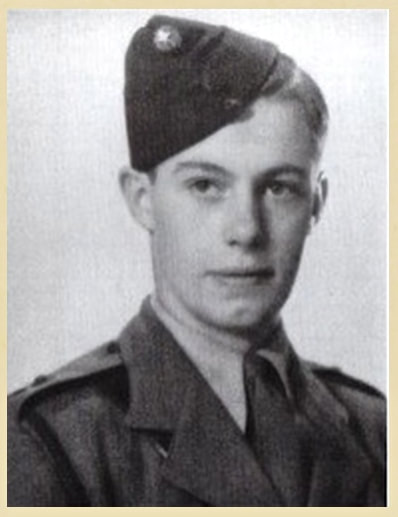

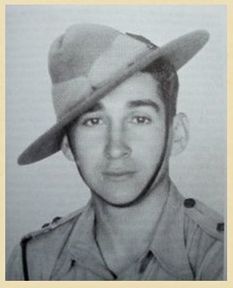

Lieutenant Harold James

Lt. Harold Douglas James.

Lt. Harold Douglas James.

You're going into Burma, have you made your wills?

Three young Subalterns of the 8th Gurkha Rifles joined the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade almost at the very last minute in January 1943. They had previously served with their original unit on the North West Frontier and were based at Quetta when they received their orders to travel across India to the Jhansi railhead junction.

On arrival at the Jhansi camp, all three were asked if they had made an Army will to cover any unforeseen eventuality, something that I imagine was rather disconcerting to hear and then allocated to join one of the Chindit Gurkha columns. The three soldiers were, 2nd Lieutenant Ian MacHorton who went to 2 Column, 2nd Lieutenant Alec Gibson, who went over to 3 Column, alongside his friend, 2nd Lieutenant Harold James.

Lt. James, who had been born (Bombay) and raised in India prior to the war, with his father serving in the Indian Army, was rather nonplussed by the Chindit ethos and in his book, Across the Threshold of Battle, suggests that he felt the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles were rather unprepared for the expedition they were about to undertake. Being a late arrival to the Column and the youngest officer within their ranks, Harold was landed with perhaps the worst of all jobs; to look after the pack bullocks and carts on the journey from Imphal to the Chindwin River.

His disappointment in this role was further aggravated by having to manage all these animals whilst riding his own charger, something that Harold found uncomfortable, being no horseman and which he soon gave up as a bad idea. In the early stages of the operation and in particular during the crossing of the Chindwin, Lt. James relied heavily upon his Gurkha Orderly, Rifleman Josbir Thapa. This young Gurkha proved to be a calming influence and supplied Lt. James with sound advice, often served up alongside a mug of piping hot tea.

Thankfully, not long into the expedition, 3 Column commander Major Mike Calvert, gave Lt. James a new role. Just prior to the first Brigade supply drop at a place called Tonmakeng, he was placed in charge of No. 13 Platoon and provided a bodyguard for Flight-Lieutenant Bobby Thompson of the RAF and his team, as they selected and prepared the drop zone location.

Alongside Harold James in 13 Platoon was Jemadar Andaram Gurung, a well-respected and capable Gurkha officer, who the British officers in 3 Column affectionately called Under Arm. As the expedition went on, Major Calvert was to rely on these two junior officers on many occasions, choosing them on several occasions for roles in defence of the column.

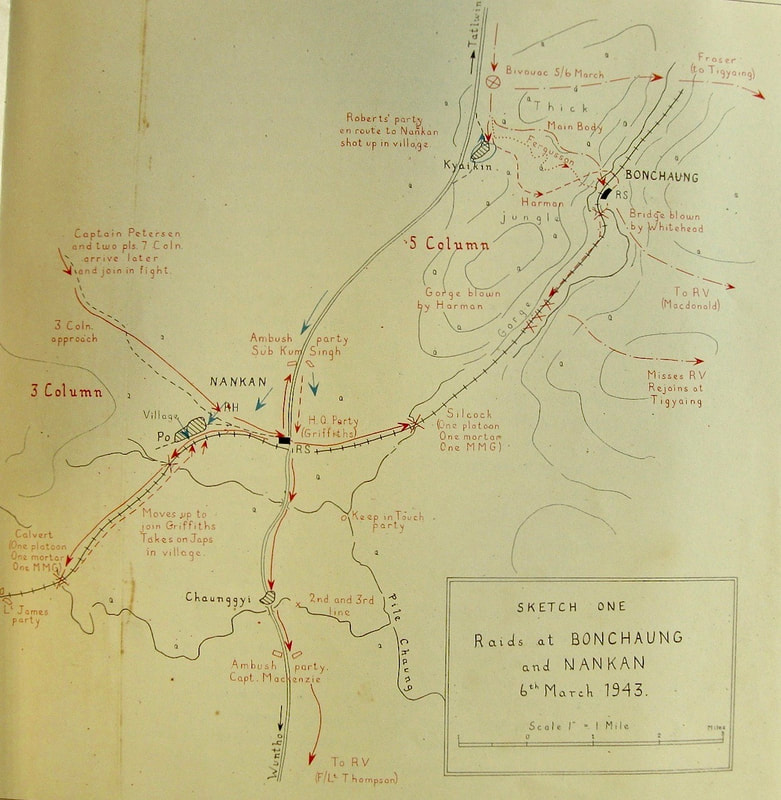

As the column approached Sinlamaung village in late February 1943, Lt. James joined Calvert in a stalking manoeuvre on a Japanese garrison known to be in the area. In the end this venture came to nought, but it highlighted Calvert’s trust in the young Subaltern. As 3 Column came close to their main objective on Operation Longcloth, the demolition of the railway line around Nankan, Lt. James was given the task of protecting the Royal Engineers as they went about their destructive business.

From the book, Wingate's Raiders, by Charles J. Rolo:

Nankan station was completely deserted when 3 Column arrived. All around were scattered teak logs and other debris from the 1942 retreat; magazine pouches, cans, smashed equipment and one rusty crippled jeep. On a siding stood trucks riddled with bullet-holes and a blown up locomotive rested grotesquely on its side. The station was situated in a small area of completely open ground. Two hundred yards north of it, surrounded by jungle palms, was a Burmese village. The Japanese were based in some strength at Indaw, twenty-five miles to the north and Wuntho, ten miles to the south. The new motor road from Indaw to Wuntho cut across the railway line just beside the station. Calvert fixed a rendezvous several miles to the south-east of the railway, then set his men to the demolitions.

Seen below is a gallery of image in relation to this first section of the story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Three young Subalterns of the 8th Gurkha Rifles joined the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade almost at the very last minute in January 1943. They had previously served with their original unit on the North West Frontier and were based at Quetta when they received their orders to travel across India to the Jhansi railhead junction.

On arrival at the Jhansi camp, all three were asked if they had made an Army will to cover any unforeseen eventuality, something that I imagine was rather disconcerting to hear and then allocated to join one of the Chindit Gurkha columns. The three soldiers were, 2nd Lieutenant Ian MacHorton who went to 2 Column, 2nd Lieutenant Alec Gibson, who went over to 3 Column, alongside his friend, 2nd Lieutenant Harold James.

Lt. James, who had been born (Bombay) and raised in India prior to the war, with his father serving in the Indian Army, was rather nonplussed by the Chindit ethos and in his book, Across the Threshold of Battle, suggests that he felt the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles were rather unprepared for the expedition they were about to undertake. Being a late arrival to the Column and the youngest officer within their ranks, Harold was landed with perhaps the worst of all jobs; to look after the pack bullocks and carts on the journey from Imphal to the Chindwin River.

His disappointment in this role was further aggravated by having to manage all these animals whilst riding his own charger, something that Harold found uncomfortable, being no horseman and which he soon gave up as a bad idea. In the early stages of the operation and in particular during the crossing of the Chindwin, Lt. James relied heavily upon his Gurkha Orderly, Rifleman Josbir Thapa. This young Gurkha proved to be a calming influence and supplied Lt. James with sound advice, often served up alongside a mug of piping hot tea.

Thankfully, not long into the expedition, 3 Column commander Major Mike Calvert, gave Lt. James a new role. Just prior to the first Brigade supply drop at a place called Tonmakeng, he was placed in charge of No. 13 Platoon and provided a bodyguard for Flight-Lieutenant Bobby Thompson of the RAF and his team, as they selected and prepared the drop zone location.

Alongside Harold James in 13 Platoon was Jemadar Andaram Gurung, a well-respected and capable Gurkha officer, who the British officers in 3 Column affectionately called Under Arm. As the expedition went on, Major Calvert was to rely on these two junior officers on many occasions, choosing them on several occasions for roles in defence of the column.

As the column approached Sinlamaung village in late February 1943, Lt. James joined Calvert in a stalking manoeuvre on a Japanese garrison known to be in the area. In the end this venture came to nought, but it highlighted Calvert’s trust in the young Subaltern. As 3 Column came close to their main objective on Operation Longcloth, the demolition of the railway line around Nankan, Lt. James was given the task of protecting the Royal Engineers as they went about their destructive business.

From the book, Wingate's Raiders, by Charles J. Rolo:

Nankan station was completely deserted when 3 Column arrived. All around were scattered teak logs and other debris from the 1942 retreat; magazine pouches, cans, smashed equipment and one rusty crippled jeep. On a siding stood trucks riddled with bullet-holes and a blown up locomotive rested grotesquely on its side. The station was situated in a small area of completely open ground. Two hundred yards north of it, surrounded by jungle palms, was a Burmese village. The Japanese were based in some strength at Indaw, twenty-five miles to the north and Wuntho, ten miles to the south. The new motor road from Indaw to Wuntho cut across the railway line just beside the station. Calvert fixed a rendezvous several miles to the south-east of the railway, then set his men to the demolitions.

Seen below is a gallery of image in relation to this first section of the story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

The Japanese eventually caught up with the column at Nankan and a fierce firefight ensued. This was admirably dealt with by the Gurkhas led with great courage and energy by Subedar-Major Kumba Sing Gurung. As the column moved away from Nankan, Harold James was asked to lead a recce group and find a safe route to the Irrawaddy.

As 3 Column approached an island close to the Irrawaddy River, Lt. James was once again given the role of rearguard, this time taking charge of No. 15 Platoon. As the column were fording a stream prior to reaching the actual river, a Japanese patrol latched on to its tail. Lt. James and his men, from the cover of some elephant grass, kept the enemy at bay with machine gun and eventually mortar fire. During the battle, Harold had to assist Bren Gunner Sherbahadur Ale in firing on the enemy after his own No. 2 Gunner was mortally wounded.

After checking that the enemy had been dealt with successfully, it fell to Lt. James to administer a lethal dose of morphine to the wounded Bren Gunner, now lying in agony on the sand. In his book he remembered:

I knew I could not let him continue in agony. I could not put off this moment which I had been dreading for so long. Reaching into my haversack I took out the capsules, and it felt as though I were holding red hot coals, wanting to drop them into the mud and destroy them. But another pitiful cry from the wounded man brought me to his side. The platoon Havildar took out the groundsheet from the Gurkha’s pack and gently covered his body. Major Calvert came by at that moment, and taking my arm told me I had done well and that the column were moving out.

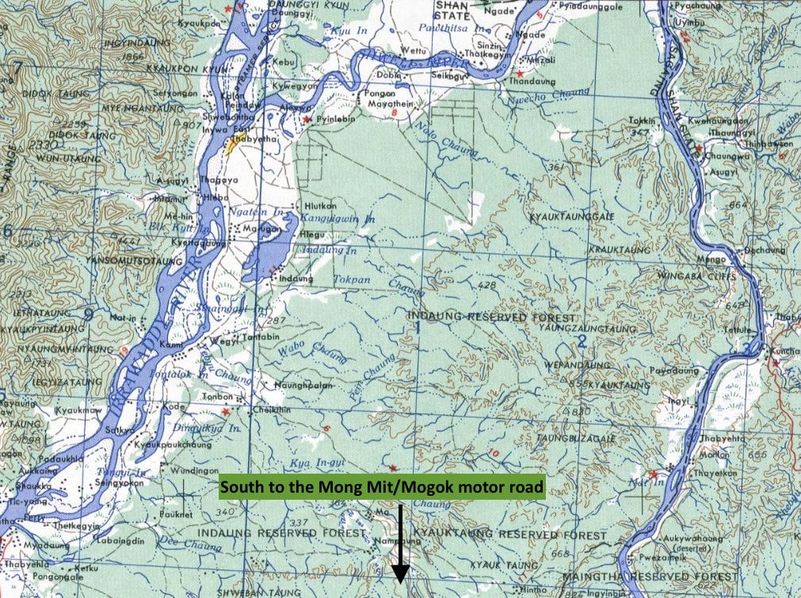

By the 18th March, all Chindit Columns still operational were over the Irrawaddy. 3 Column had received orders from Wingate to move southeast in an attempt to reach and destroy the Gokteik Viaduct. Just before this Lt. James bumped into his old friend Ian MacHorton who was now marching with No. 1 Column. After a brief catch up on each other’s activities, they discussed the validity of Wingate’s decision to take the Brigade over the river.

Harold James recalled:

Now all columns were concentrated within fifteen miles of each other and trapped in a box. The north and east sides of the box were formed by the Shweli River and the south by the roads running east-west between Mongmit and Mogok, The vast Irrawaddy was the lid, snapped shut behind the columns, padlocked by withdrawing as many boats as possible to the west and increasing patrol activity along east banks. The countryside was so hostile at this time of the year, with most of the chaungs dry and waterless, the forests trackless and surrounded by enemy controlled roads.

As 3 Column approached an island close to the Irrawaddy River, Lt. James was once again given the role of rearguard, this time taking charge of No. 15 Platoon. As the column were fording a stream prior to reaching the actual river, a Japanese patrol latched on to its tail. Lt. James and his men, from the cover of some elephant grass, kept the enemy at bay with machine gun and eventually mortar fire. During the battle, Harold had to assist Bren Gunner Sherbahadur Ale in firing on the enemy after his own No. 2 Gunner was mortally wounded.

After checking that the enemy had been dealt with successfully, it fell to Lt. James to administer a lethal dose of morphine to the wounded Bren Gunner, now lying in agony on the sand. In his book he remembered:

I knew I could not let him continue in agony. I could not put off this moment which I had been dreading for so long. Reaching into my haversack I took out the capsules, and it felt as though I were holding red hot coals, wanting to drop them into the mud and destroy them. But another pitiful cry from the wounded man brought me to his side. The platoon Havildar took out the groundsheet from the Gurkha’s pack and gently covered his body. Major Calvert came by at that moment, and taking my arm told me I had done well and that the column were moving out.

By the 18th March, all Chindit Columns still operational were over the Irrawaddy. 3 Column had received orders from Wingate to move southeast in an attempt to reach and destroy the Gokteik Viaduct. Just before this Lt. James bumped into his old friend Ian MacHorton who was now marching with No. 1 Column. After a brief catch up on each other’s activities, they discussed the validity of Wingate’s decision to take the Brigade over the river.

Harold James recalled:

Now all columns were concentrated within fifteen miles of each other and trapped in a box. The north and east sides of the box were formed by the Shweli River and the south by the roads running east-west between Mongmit and Mogok, The vast Irrawaddy was the lid, snapped shut behind the columns, padlocked by withdrawing as many boats as possible to the west and increasing patrol activity along east banks. The countryside was so hostile at this time of the year, with most of the chaungs dry and waterless, the forests trackless and surrounded by enemy controlled roads.

About four days after crossing the Irrawaddy, 3 Column reached the outskirts of a Burmese village called Pago. Here Lt. James was ordered to lead No. 14 Platoon alongside CSM Blain and some of his Commandos and set an ambush for the Japanese on the tracks outside the village.

From the book Wingate's Raiders:

On March 22nd, Calvert cached four days' paratroop rations for each man against an emergency and moved off eastward. To the north he kept hearing the sound of heavy gunfire; it was Wingate's force fighting almost continual battles with the Japs. That evening Calvert's column reached the Nammit Chaung, which ran across the line of march to their next target. At dawn twelve Burma Rifles under a British Lieutenant waded the stream and cautiously approached a village, Pago, one and a half miles from Calvert's bivouac. Natives warned them that a patrol of sixty Japs was in the village, and two runners were sent back to Calvert.

On the way back the runners bumped into an enemy scouting party of about twenty men. One of them made a dash for it with the message, the other dodged behind a tree and at point-blank range coolly aimed twelve shots at the Japanese. Two dropped a few yards away from him, and he hadn't time to count how many more he had hit. When he turned up at the bivouac he reported two Japanese killed. Later Calvert's men discovered seven bodies on the trail.

Another patrol meanwhile had captured Japanese operational orders from a battalion to one of its companies that was hunting for Wingate's men. This, amplified by information from the villagers, gave Calvert a very clear picture of what paths the Japs were using and where their main forces were concentrated.

Calvert ordered Second Lieutenant James with two Gurkha sections and a British Tommy-gun section to lay an ambush on one of the trails along which a Japanese patrol was advancing. The ambush party had not been in position for more than an hour when they saw thirty-six Japs marching down a dust road. When Lieutenant James gave the order to fire Sergeant-Major Blain yelled out to the front Tommy-gun-man, " There you are, my boy, there's a birthday present for you."

The Japanese were taken completely by surprise. This wasn't in their book of rules, and they lost their heads. Instead of scattering, they dropped to their knees on the road and started firing blindly into the jungle in all directions. They were a sitting target. The first volley killed twenty of them. The survivors did the only thing the Japanese know how to do when they're caught off guard. They fixed bayonets and charged straight to their death. James picked off five of them with his rifle. His Tommy-gunners wiped out the rest. Not a single one escaped.

Other Japanese patrols, however, heard the sound of firing and closed in, this time with greater caution. Back in bivouac Calvert suddenly heard a voice in the jungle close by, calling, " Sergeant-Major, come over here." He held his fire, thinking it might possibly be someone hunting for Sergeant-Major Blain, but whispered to the men to keep a sharp look-out. A moment later they spotted a Japanese uniform, and Calvert ordered one platoon to make a bayonet sweep from the flank. The Japs let out a frightful yell when the Chindits suddenly piled on top of them with machetes and bayonets.

The survivors dropped their equipment and ran. Calvert's casualties were three dead and two missing. Meanwhile Lieutenant James's party had engaged another Japanese patrol and Calvert's column mortar was lobbing shells just over the heads of James's men on to the advancing Japanese. At 4 P.M. Calvert, fearing that the enemy would bring up more troops and surround them after dark, ordered James to prepare to break off the action.

The Chindits loaded up the mules and moved back westward, laying booby traps on their trail. Calvert led them to the dump where they had cached the paratroop rations and there bivouacked for the night. All the next day the 3 Column made a wide detour to the south-west with the intention of shaking off the Japs before again attempting to cross the Nammit.

For several days it had been impossible to establish wireless contact with Brigade Headquarters because, as Calvert guessed, the Brigadier's group had been fighting a battle at and around Baw. At noon on March 25th, Calvert halted to see if he could get a report through to Wingate. Brigade Headquarters was contacted without difficulty, and Thompson picked up a message from the Brigadier. It was an order to withdraw from Burma.

Lt. James rejoined the main body of the column having lost three men killed including his Platoon Havildar, Tilbir Thapa. 3 Column as a whole had lost nine men. On receiving the message from Wingate to return to India, Major Calvert had lost the opportunity to blow up the Gokteik Viaduct for a second time. The first occasion being on the way out of Burma in mid-1942 during the infamous retreat. Calvert decided to exit the area immediately and attempt to cross the nearby Shweli River and then strike north for the Irrawaddy, hopefully crossing somewhere between Katha and Bhamo.

From the book Wingate's Raiders:

On March 22nd, Calvert cached four days' paratroop rations for each man against an emergency and moved off eastward. To the north he kept hearing the sound of heavy gunfire; it was Wingate's force fighting almost continual battles with the Japs. That evening Calvert's column reached the Nammit Chaung, which ran across the line of march to their next target. At dawn twelve Burma Rifles under a British Lieutenant waded the stream and cautiously approached a village, Pago, one and a half miles from Calvert's bivouac. Natives warned them that a patrol of sixty Japs was in the village, and two runners were sent back to Calvert.

On the way back the runners bumped into an enemy scouting party of about twenty men. One of them made a dash for it with the message, the other dodged behind a tree and at point-blank range coolly aimed twelve shots at the Japanese. Two dropped a few yards away from him, and he hadn't time to count how many more he had hit. When he turned up at the bivouac he reported two Japanese killed. Later Calvert's men discovered seven bodies on the trail.

Another patrol meanwhile had captured Japanese operational orders from a battalion to one of its companies that was hunting for Wingate's men. This, amplified by information from the villagers, gave Calvert a very clear picture of what paths the Japs were using and where their main forces were concentrated.

Calvert ordered Second Lieutenant James with two Gurkha sections and a British Tommy-gun section to lay an ambush on one of the trails along which a Japanese patrol was advancing. The ambush party had not been in position for more than an hour when they saw thirty-six Japs marching down a dust road. When Lieutenant James gave the order to fire Sergeant-Major Blain yelled out to the front Tommy-gun-man, " There you are, my boy, there's a birthday present for you."

The Japanese were taken completely by surprise. This wasn't in their book of rules, and they lost their heads. Instead of scattering, they dropped to their knees on the road and started firing blindly into the jungle in all directions. They were a sitting target. The first volley killed twenty of them. The survivors did the only thing the Japanese know how to do when they're caught off guard. They fixed bayonets and charged straight to their death. James picked off five of them with his rifle. His Tommy-gunners wiped out the rest. Not a single one escaped.

Other Japanese patrols, however, heard the sound of firing and closed in, this time with greater caution. Back in bivouac Calvert suddenly heard a voice in the jungle close by, calling, " Sergeant-Major, come over here." He held his fire, thinking it might possibly be someone hunting for Sergeant-Major Blain, but whispered to the men to keep a sharp look-out. A moment later they spotted a Japanese uniform, and Calvert ordered one platoon to make a bayonet sweep from the flank. The Japs let out a frightful yell when the Chindits suddenly piled on top of them with machetes and bayonets.

The survivors dropped their equipment and ran. Calvert's casualties were three dead and two missing. Meanwhile Lieutenant James's party had engaged another Japanese patrol and Calvert's column mortar was lobbing shells just over the heads of James's men on to the advancing Japanese. At 4 P.M. Calvert, fearing that the enemy would bring up more troops and surround them after dark, ordered James to prepare to break off the action.

The Chindits loaded up the mules and moved back westward, laying booby traps on their trail. Calvert led them to the dump where they had cached the paratroop rations and there bivouacked for the night. All the next day the 3 Column made a wide detour to the south-west with the intention of shaking off the Japs before again attempting to cross the Nammit.

For several days it had been impossible to establish wireless contact with Brigade Headquarters because, as Calvert guessed, the Brigadier's group had been fighting a battle at and around Baw. At noon on March 25th, Calvert halted to see if he could get a report through to Wingate. Brigade Headquarters was contacted without difficulty, and Thompson picked up a message from the Brigadier. It was an order to withdraw from Burma.

Lt. James rejoined the main body of the column having lost three men killed including his Platoon Havildar, Tilbir Thapa. 3 Column as a whole had lost nine men. On receiving the message from Wingate to return to India, Major Calvert had lost the opportunity to blow up the Gokteik Viaduct for a second time. The first occasion being on the way out of Burma in mid-1942 during the infamous retreat. Calvert decided to exit the area immediately and attempt to cross the nearby Shweli River and then strike north for the Irrawaddy, hopefully crossing somewhere between Katha and Bhamo.

After returning once more to the Salin Chaung to pick up the last of the stored rations, No. 3 Column pushed on towards the Shweli River. It was extremely tough going, through tight-set jungle and encountering nothing but dry streams along the way. Three days had passed, when the column bumped a large Japanese patrol near the river and two Gurkhas were killed. In the end, Calvert decided to abandon the Shweli route and turned his men west in a direct march for India.

By the 29th March and after a long consultation with his officers, Major Calvert very reluctantly agreed to break his column down into small dispersal parties. Harold James and No. 13 Platoon were paired with a Burma Rifles section led by Captain Taffy Griffiths. On the 30th March the column had one final supply drop and re-stocked for the long journey back to the Chindwin River. Major Calvert, breaking out the last rum bottle, toasted No. 3 Column and thanked his men for all their efforts, wishing them good luck in reaching India.

Lt. James and Taffy Griffiths decided to move away from the rest of the column by marching directly south-west for a time, hoping to drop out of the zone where the Japanese had the majority of their patrols. This took the thirty strong party into hot and waterless country where water discipline would be crucial. After several thirsty days the group finally struck the Dawma Chaung and were able to refill their water bottles, before moving along the chaung which ultimately flowed into the Irrawaddy.

One of Captain Griffiths' Karen Riflemen went off to seek out boats in which to cross the mile-wide river. He returned a few hours later with a local villager who promised to get the group over in double-quick time. The men then met an excited, but obviously frightened village Headman. He showed them a large sampan boat and alongside this were two more smaller dugout canoes. Jemadar Andaram Gurung concluded that the boats were enough to get the party over in two journeys and proceeded to organise the first group to cross. The Headman of Magyigon village told Taffy Griffiths that the Japanese motor launch which patrolled this section of the river had passed by around half hour previously and would not be back for several hours. The Chindits let loose their last remaining pack mule, boarded the boats and began a precarious but ultimately successful crossing of the Irrawaddy, paying the boatmen in silver rupees at the conclusion of their labour.

NB. Not long afterwards, Flight-Lieutenant Bobby Thompson and his dispersal party came across the same village and used the sampan to gain their own crossing of the Irrawaddy.

The next morning, Lt. James led his men away from the Irrawaddy, heading west towards the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway line, the next obstacle on the journey back to India. Almost immediately they bumped into Mike Calvert's dispersal party. Although pleased to meet up with his commander, Taffy Griffiths declined Calvert's invitation to travel back together, fearing that Calvert would want to create mischief along the way. His concern was fully justified the very next day when he heard loud explosions from a few miles away, as Calvert and his Sappers destroyed sections of the railway line for the second time just south of Nankan.

Two days later, Lt. James and his dispersal party approached the banks of the Mu River, with some relief they forded the shallow water way without interference. By now rations were becoming an issue and the group made up its mind to enter the next village in search of food, before they encountered the unpopulated Zibu Taungdan escarpment. It was at this point that they bumped Robert Thompson and his party for a second time. Thompson, by reputation a genius in map reading, had somehow got his group ahead of the other parties from No. 3 Column, but was now also looking for food to bolster his men's rations and fodder for Yankee, their last remaining mule.

Griffiths and Thompson agreed to join up for the final push to the Chindwin. On entering the next village on the trail, suspicions were raised when the Headman delayed unduly the collection of cooked rice and vegetables. The Chindits fearing treachery, grabbed what they could and exited the village. Within minutes shots were heard to the rear as a Japanese patrol attacked the tail of the column. Defence discipline was lost during the ambush and one Gurkha Section became separated. Lt. James was disappointed with the performance of his men, but by now understood that they were at the end of their tether, hungry and exhausted.

NB. The Gurkha Section lost at the ambush mentioned above, did manage to make their own way back to India.

By the 11th April, the group were struggling through tight-set bamboo jungle and making painfully slow progress. Added to this torment, the early onset monsoon rain showers were becoming more frequent, threatening to turn the presently slow-moving Chindwin into a raging torrent. The column Medical Officer, Dr. Rao, who had travelled with Bobby Thompson since dispersal was himself now in a very bad way. He was clearly exhausted and malnourished and his legs were continuously giving way as he marched. Harold James tasked two of his Riflemen to watch out for the Doctor and ensure his continued advance.

By the 29th March and after a long consultation with his officers, Major Calvert very reluctantly agreed to break his column down into small dispersal parties. Harold James and No. 13 Platoon were paired with a Burma Rifles section led by Captain Taffy Griffiths. On the 30th March the column had one final supply drop and re-stocked for the long journey back to the Chindwin River. Major Calvert, breaking out the last rum bottle, toasted No. 3 Column and thanked his men for all their efforts, wishing them good luck in reaching India.

Lt. James and Taffy Griffiths decided to move away from the rest of the column by marching directly south-west for a time, hoping to drop out of the zone where the Japanese had the majority of their patrols. This took the thirty strong party into hot and waterless country where water discipline would be crucial. After several thirsty days the group finally struck the Dawma Chaung and were able to refill their water bottles, before moving along the chaung which ultimately flowed into the Irrawaddy.

One of Captain Griffiths' Karen Riflemen went off to seek out boats in which to cross the mile-wide river. He returned a few hours later with a local villager who promised to get the group over in double-quick time. The men then met an excited, but obviously frightened village Headman. He showed them a large sampan boat and alongside this were two more smaller dugout canoes. Jemadar Andaram Gurung concluded that the boats were enough to get the party over in two journeys and proceeded to organise the first group to cross. The Headman of Magyigon village told Taffy Griffiths that the Japanese motor launch which patrolled this section of the river had passed by around half hour previously and would not be back for several hours. The Chindits let loose their last remaining pack mule, boarded the boats and began a precarious but ultimately successful crossing of the Irrawaddy, paying the boatmen in silver rupees at the conclusion of their labour.

NB. Not long afterwards, Flight-Lieutenant Bobby Thompson and his dispersal party came across the same village and used the sampan to gain their own crossing of the Irrawaddy.

The next morning, Lt. James led his men away from the Irrawaddy, heading west towards the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway line, the next obstacle on the journey back to India. Almost immediately they bumped into Mike Calvert's dispersal party. Although pleased to meet up with his commander, Taffy Griffiths declined Calvert's invitation to travel back together, fearing that Calvert would want to create mischief along the way. His concern was fully justified the very next day when he heard loud explosions from a few miles away, as Calvert and his Sappers destroyed sections of the railway line for the second time just south of Nankan.

Two days later, Lt. James and his dispersal party approached the banks of the Mu River, with some relief they forded the shallow water way without interference. By now rations were becoming an issue and the group made up its mind to enter the next village in search of food, before they encountered the unpopulated Zibu Taungdan escarpment. It was at this point that they bumped Robert Thompson and his party for a second time. Thompson, by reputation a genius in map reading, had somehow got his group ahead of the other parties from No. 3 Column, but was now also looking for food to bolster his men's rations and fodder for Yankee, their last remaining mule.

Griffiths and Thompson agreed to join up for the final push to the Chindwin. On entering the next village on the trail, suspicions were raised when the Headman delayed unduly the collection of cooked rice and vegetables. The Chindits fearing treachery, grabbed what they could and exited the village. Within minutes shots were heard to the rear as a Japanese patrol attacked the tail of the column. Defence discipline was lost during the ambush and one Gurkha Section became separated. Lt. James was disappointed with the performance of his men, but by now understood that they were at the end of their tether, hungry and exhausted.

NB. The Gurkha Section lost at the ambush mentioned above, did manage to make their own way back to India.

By the 11th April, the group were struggling through tight-set bamboo jungle and making painfully slow progress. Added to this torment, the early onset monsoon rain showers were becoming more frequent, threatening to turn the presently slow-moving Chindwin into a raging torrent. The column Medical Officer, Dr. Rao, who had travelled with Bobby Thompson since dispersal was himself now in a very bad way. He was clearly exhausted and malnourished and his legs were continuously giving way as he marched. Harold James tasked two of his Riflemen to watch out for the Doctor and ensure his continued advance.

A few days later, the group moved into the Chindwin Valley marching up down the jungle covered hills towards the river. Suddenly up ahead, Taffy Griffiths began to stumble and fell sideways against a tree. His face was covered in a red rash and he was clearly in a very bad way. The Doctor rushed forward and after a brief examination, went to his pack and produced a syringe, injecting Captain Griffiths with some sort of serum. He had suffered an allergic reaction from something or other, but recovered fairly quickly and continued to march within the hour.

On the 14th April, the party were met on the trail by a Burmese villager who told them that not very far away there was a platoon of British Indian troops. Cautiously, the Chindits followed this man, who as promised led them to some Sikh soldiers from the Patiala Regiment.

The commanding officer from the Patiala's organised boats to take the group over the Chindwin and then up into the hills beyond to their base camp. The Chindits were treated royally by the Indian troops and were given food and fresh water before settling down for the night. Later on, Lt. James, Taffy Griifiths, Bobby Thompson and their men were transported up to Imphal, where they were all admitted to Casualty Clearing Station No. 19, run by Matron Agnes McGearey.

Over time, many more Chindits started to arrive at the Casualty Clearing station, including Major Calvert and other soldiers from No. 3 Column. In the end over 200 personnel from Calvert's column returned out of the 360 or so that started the campaign in February 1943. Whilst in hospital, the Chindits suffered several Japanese dive bomber attacks. One of these raids successfully destroyed several ward buildings by setting them alight. Reacting to this, Major Calvert organised a mounted Bren gun to be set up to counter these enemy visits, ordering Harold James and Sergeant-Major Blain to man the weapon. Ironically, no more air raids took place from that moment on.

Soon it was time for the men to return to their respective regiments. On their last night at Imphal, the officers of No. 3 Column were sat together in a basha and toasted those who had not returned from Burma and had given their lives bravely during the expedition, they also drank to their own futures, fearing that the war with Japan would last for many years to come. Lt. James journeyed to Dehra Dun to the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles HQ and from there was ordered back to the 8th Gurkha HQ at Quetta where he met up with Ian MacHorton and learned that Alec Gibson had been taken prisoner by the Japanese. He left Quetta shortly afterwards for an extended leave period in Poona.

On the 14th April, the party were met on the trail by a Burmese villager who told them that not very far away there was a platoon of British Indian troops. Cautiously, the Chindits followed this man, who as promised led them to some Sikh soldiers from the Patiala Regiment.

The commanding officer from the Patiala's organised boats to take the group over the Chindwin and then up into the hills beyond to their base camp. The Chindits were treated royally by the Indian troops and were given food and fresh water before settling down for the night. Later on, Lt. James, Taffy Griifiths, Bobby Thompson and their men were transported up to Imphal, where they were all admitted to Casualty Clearing Station No. 19, run by Matron Agnes McGearey.

Over time, many more Chindits started to arrive at the Casualty Clearing station, including Major Calvert and other soldiers from No. 3 Column. In the end over 200 personnel from Calvert's column returned out of the 360 or so that started the campaign in February 1943. Whilst in hospital, the Chindits suffered several Japanese dive bomber attacks. One of these raids successfully destroyed several ward buildings by setting them alight. Reacting to this, Major Calvert organised a mounted Bren gun to be set up to counter these enemy visits, ordering Harold James and Sergeant-Major Blain to man the weapon. Ironically, no more air raids took place from that moment on.

Soon it was time for the men to return to their respective regiments. On their last night at Imphal, the officers of No. 3 Column were sat together in a basha and toasted those who had not returned from Burma and had given their lives bravely during the expedition, they also drank to their own futures, fearing that the war with Japan would last for many years to come. Lt. James journeyed to Dehra Dun to the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles HQ and from there was ordered back to the 8th Gurkha HQ at Quetta where he met up with Ian MacHorton and learned that Alec Gibson had been taken prisoner by the Japanese. He left Quetta shortly afterwards for an extended leave period in Poona.

For his efforts during Operation Longcloth, Harold James was awarded the Military Cross:

Second-Lieutenant Harold Douglas James

Action for which recommended:

Operations in Burma, March/April 1943.

At Nankan Railway Station on 6th March 1943, Lt. James showed coolness and self confidence in his first action when leading his platoon into the attack. On 23rd March 1943, during the crossing of the Irrawaddy, his platoon was sited in a position to prevent the enemy crossing a creek when the column was suddenly attacked by the enemy with small arms fire and mortars. He immediately attacked them inflicting heavy casualties and preventing them from crossing, personally walking round his platoon while under fire and placing his men in the best positions.

This officer showed great devotion to duty throughout the campaign and great gallantry on many occasions.

Military Cross recommended by- Major J.M.Calvert (No. 3 Column) 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

After the war, Harold James worked for a time with the Burma Armed Police, returning on occasions to some of the places where he had fought the Japanese in 1943.

Second-Lieutenant Harold Douglas James

Action for which recommended:

Operations in Burma, March/April 1943.

At Nankan Railway Station on 6th March 1943, Lt. James showed coolness and self confidence in his first action when leading his platoon into the attack. On 23rd March 1943, during the crossing of the Irrawaddy, his platoon was sited in a position to prevent the enemy crossing a creek when the column was suddenly attacked by the enemy with small arms fire and mortars. He immediately attacked them inflicting heavy casualties and preventing them from crossing, personally walking round his platoon while under fire and placing his men in the best positions.

This officer showed great devotion to duty throughout the campaign and great gallantry on many occasions.

Military Cross recommended by- Major J.M.Calvert (No. 3 Column) 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

After the war, Harold James worked for a time with the Burma Armed Police, returning on occasions to some of the places where he had fought the Japanese in 1943.

Cap badge of the 2nd GR.

Cap badge of the 2nd GR.

Their follows below, an account of what happened to some of the soldiers mentioned in Harold James' story.

Rifleman Josbir Thapa. Harold James describes his Gurkha Orderly as: a young Gurkha Rifleman, perhaps a year or so older than myself, well built, with a moon-shaped face and a cheerful manner which rarely changed. He was a constant support during the campaign, looking after me and keeping me fed, clothed and watered. He was especially good at making tea and was an important source of advice on the dispersal march back to India. Sadly, I never saw him again after I left the 3/2 Gurkhas at Dehra Dun in mid-1943.

It is presumed that Josbir went on to serve with the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles during the Arakan Campaign of 1944 and that he survived the war to return home to Nepal.

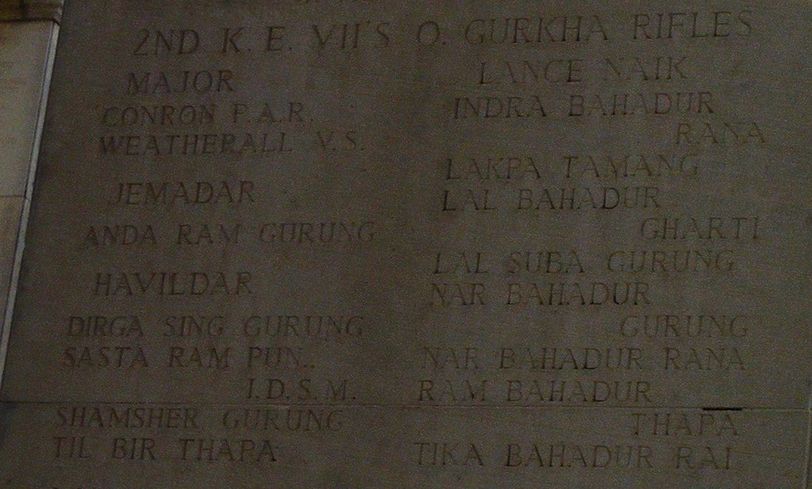

Jemadar Anda Ram Gurung. Anda Ram Gurung was the son of Dharam Sing and Sarkiseon, of Ghan Pokhra in Nepal. He was a junior platoon commander within the Gurkha Section of No. 3 Column led by Captain George Silcock. He took control of a section of men at the Nankan rail station engagement with the Japanese on the 6th March 1943. He led his men in support of Subedar Kumba Sing Gurung, as he attempted to deal with an enemy ambush on the northern outskirts of the town.

Harold James, fondly remembered the young and trustworthy Jemadar in his book, Across the Threshold of Battle:

I was glad to be given a decent job and also that 13 Platoon was to be in my charge. The platoon's Gurkha Officer was Jemadar Anda Ram Gurung. He was universally liked and affectionately called 'Under Arm' by us British officers. Slim, plucky and ugly, but with a transforming smile when he laughed, which was very often, he was a man I came to know well and could really trust.

Sadly, having successfully reached the safety of India in April 1943, Anda Ram Gurung later succumbed to a severe bout of malignant malaria whilst at home in Nepal and died on 24th June. Even though he died at home in Nepal, Anda Ram is also remembered upon Face 57 of the Rangoon Memorial, located as the centre piece of Taukkyan War Cemetery on the outskirts of Rangoon.

Subedar Kumba Sing Gurung. Kumba Sing was the senior Gurkha Officer in No. 3 Column. Harold James described him as: a short but broad-shouldered man, keen on smart appearance and self-discipline, he was a perfect soldier. He took me under his wing on Operation Longcloth, first testing my mettle and then trusting me to lead his men.

At the battle of Nankan on the 6th March 1943, Major Mike Calvert placed Kumba Sing in charge of blocking the main road into the rail station whilst the demolition squad went about their business. The Subedar succeeded in holding off a large patrol of Japanese for several hours and was rewarded for his endeavours with the Indian Distinguished Service Medal. After dispersal was called in late March, Calvert gave one of the column dispersal parties over to Kumba Sing, which he successfully led out of Burma via the Chinese Yunnan Borders and eventual safety. It is highly likely that Subedar Kumba Sing went on to serve with his battalion in the Arakan region of Burma in 1944 and that he survived the rest of the war.

Here is the recommendation for Kumba Sing Gurung's IDSM, as put forward by Major Calvert in August 1943:

On 6th March 1943, at Nankan Railway Station, Subedar Kumba Sing Gurung was detached with one section and an anti-tank rifle to guard a track while demolitions were being carried out on the railway. Two lorry loads of Japanese infantry arrived and drove straight into the ambush which he had laid. The majority were killed at the outset, but the remainder were reinforced. The Subedar continued to fight the enemy for two hours, gaining complete immunity from interruption for the parties engaged in demolishing the railway. He himself shot two of the enemy, on whom 15 casualties were inflicted without loss to our own troops. During the whole of the campaign as Senior Gurkha Officer with his column he maintained the morale and discipline of his men under trying circumstances and upheld the finest tradition of the Gurkha Officer.

IDSM recommended by: Major J.M.Calvert (No. 3 Column) 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

Lance Naik Sherbahadur Ale. A Bren gunner with No. 15 Platoon in 3 Column on Operation Longcloth, this man was described by Harold James as: an excellent soldier with a great sense of humour, who gave me vital support and assistance on the march out of Burma in April 1943. In 1944, Sherbahadur fought in the Arakan region of Burma with the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles and went on to become a Gurkha Major with the Regiment after the war.

For his efforts in 1943, he too was awarded the Indian Distinguished Service Medal:

7309 Lance Naik Sherbahadur Ale

Action for which recommended: Operations in Burma, March/April 1943:

At Pago on 25th March 1943 L/Nk. Sherbahadur Ale, under the orders of his Platoon Commander (Lieutenant James), led his section to the attack through the jungle, inflicted casualties on the enemy, got into position for the enemy counter attack, where more casualties were inflicted, and finally on orders withdrew, keeping his section under good order and in control. In other engagements he also did well.

IDSM recommended by: Major J.M.Calvert (No. 3 Column) 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

Havildar Til Bir Thapa. The son of Nar Bahadur and Ruki Thapa and the husband of Dementi Thapa from Hunga village in Nepal. Til Bir was the Havildar or Sergeant for No. 14 Platoon in 3 Column on Operation Longcloth. He was an extremely committed and thorough soldier who gave excellent service on the first Wingate expedition, but was sadly killed in action at the Pago engagement with the enemy on the 23rd March 1943.

Harold James described Til Bir as: a very brave Sergeant who assisted me greatly during the ambush setting at Pago. I have nightmares about this action and particularly in relation to Til Bir's death, whose involuntary scream I can still hear as the bayonet went in. I often hear that scream even fifty years later and cannot forgive myself for not leaving the area of the ambush sooner.

1909 Havildar Til Bir Thapa is remembered upon Face 57 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery, located on the northern outskirts of Rangoon. To view his CWGC details, please click on the following link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2527381/til-bir-thapa,-/

Captain D. Rao. Medical Officer for No. 3 Column on Operation Longcloth. Very little is known about Dr. Rao, apart from his very real devotion in keeping the Gurkha Rifles of 3 Column fit and well during the first Chindt expedition. He was part of Flight Officer Robert Thompson's dispersal group which finally exited Burma in mid-April 1943.

Harold James described the Indian doctor in his book, Across the Threshold of Battle: our medical officer from the Indian Medical Service was Captain Rao and came from Southern India, he was so thin that he looked as though he would snap in two at the slightest touch. In reality he was a very tough, good humoured and and excellent doctor.

It is not known whether Dr. Rao continued to serve with the Chindits after Operation Longcloth, or indeed if he survived the war and returned home to Southern India.

Rifleman Gaubahdur Gurung. This soldier served with No. 13 Platoon in 3 Column on Operation Longloth and then continued his war with the battalion in the Arakan in 1944. It is believed that Gaubahadur survived the war and returned home to Nepal.

Rifleman Josbir Thapa. Harold James describes his Gurkha Orderly as: a young Gurkha Rifleman, perhaps a year or so older than myself, well built, with a moon-shaped face and a cheerful manner which rarely changed. He was a constant support during the campaign, looking after me and keeping me fed, clothed and watered. He was especially good at making tea and was an important source of advice on the dispersal march back to India. Sadly, I never saw him again after I left the 3/2 Gurkhas at Dehra Dun in mid-1943.

It is presumed that Josbir went on to serve with the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles during the Arakan Campaign of 1944 and that he survived the war to return home to Nepal.

Jemadar Anda Ram Gurung. Anda Ram Gurung was the son of Dharam Sing and Sarkiseon, of Ghan Pokhra in Nepal. He was a junior platoon commander within the Gurkha Section of No. 3 Column led by Captain George Silcock. He took control of a section of men at the Nankan rail station engagement with the Japanese on the 6th March 1943. He led his men in support of Subedar Kumba Sing Gurung, as he attempted to deal with an enemy ambush on the northern outskirts of the town.

Harold James, fondly remembered the young and trustworthy Jemadar in his book, Across the Threshold of Battle:

I was glad to be given a decent job and also that 13 Platoon was to be in my charge. The platoon's Gurkha Officer was Jemadar Anda Ram Gurung. He was universally liked and affectionately called 'Under Arm' by us British officers. Slim, plucky and ugly, but with a transforming smile when he laughed, which was very often, he was a man I came to know well and could really trust.

Sadly, having successfully reached the safety of India in April 1943, Anda Ram Gurung later succumbed to a severe bout of malignant malaria whilst at home in Nepal and died on 24th June. Even though he died at home in Nepal, Anda Ram is also remembered upon Face 57 of the Rangoon Memorial, located as the centre piece of Taukkyan War Cemetery on the outskirts of Rangoon.

Subedar Kumba Sing Gurung. Kumba Sing was the senior Gurkha Officer in No. 3 Column. Harold James described him as: a short but broad-shouldered man, keen on smart appearance and self-discipline, he was a perfect soldier. He took me under his wing on Operation Longcloth, first testing my mettle and then trusting me to lead his men.

At the battle of Nankan on the 6th March 1943, Major Mike Calvert placed Kumba Sing in charge of blocking the main road into the rail station whilst the demolition squad went about their business. The Subedar succeeded in holding off a large patrol of Japanese for several hours and was rewarded for his endeavours with the Indian Distinguished Service Medal. After dispersal was called in late March, Calvert gave one of the column dispersal parties over to Kumba Sing, which he successfully led out of Burma via the Chinese Yunnan Borders and eventual safety. It is highly likely that Subedar Kumba Sing went on to serve with his battalion in the Arakan region of Burma in 1944 and that he survived the rest of the war.

Here is the recommendation for Kumba Sing Gurung's IDSM, as put forward by Major Calvert in August 1943:

On 6th March 1943, at Nankan Railway Station, Subedar Kumba Sing Gurung was detached with one section and an anti-tank rifle to guard a track while demolitions were being carried out on the railway. Two lorry loads of Japanese infantry arrived and drove straight into the ambush which he had laid. The majority were killed at the outset, but the remainder were reinforced. The Subedar continued to fight the enemy for two hours, gaining complete immunity from interruption for the parties engaged in demolishing the railway. He himself shot two of the enemy, on whom 15 casualties were inflicted without loss to our own troops. During the whole of the campaign as Senior Gurkha Officer with his column he maintained the morale and discipline of his men under trying circumstances and upheld the finest tradition of the Gurkha Officer.

IDSM recommended by: Major J.M.Calvert (No. 3 Column) 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

Lance Naik Sherbahadur Ale. A Bren gunner with No. 15 Platoon in 3 Column on Operation Longcloth, this man was described by Harold James as: an excellent soldier with a great sense of humour, who gave me vital support and assistance on the march out of Burma in April 1943. In 1944, Sherbahadur fought in the Arakan region of Burma with the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles and went on to become a Gurkha Major with the Regiment after the war.

For his efforts in 1943, he too was awarded the Indian Distinguished Service Medal:

7309 Lance Naik Sherbahadur Ale

Action for which recommended: Operations in Burma, March/April 1943:

At Pago on 25th March 1943 L/Nk. Sherbahadur Ale, under the orders of his Platoon Commander (Lieutenant James), led his section to the attack through the jungle, inflicted casualties on the enemy, got into position for the enemy counter attack, where more casualties were inflicted, and finally on orders withdrew, keeping his section under good order and in control. In other engagements he also did well.

IDSM recommended by: Major J.M.Calvert (No. 3 Column) 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

Havildar Til Bir Thapa. The son of Nar Bahadur and Ruki Thapa and the husband of Dementi Thapa from Hunga village in Nepal. Til Bir was the Havildar or Sergeant for No. 14 Platoon in 3 Column on Operation Longcloth. He was an extremely committed and thorough soldier who gave excellent service on the first Wingate expedition, but was sadly killed in action at the Pago engagement with the enemy on the 23rd March 1943.

Harold James described Til Bir as: a very brave Sergeant who assisted me greatly during the ambush setting at Pago. I have nightmares about this action and particularly in relation to Til Bir's death, whose involuntary scream I can still hear as the bayonet went in. I often hear that scream even fifty years later and cannot forgive myself for not leaving the area of the ambush sooner.

1909 Havildar Til Bir Thapa is remembered upon Face 57 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery, located on the northern outskirts of Rangoon. To view his CWGC details, please click on the following link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2527381/til-bir-thapa,-/

Captain D. Rao. Medical Officer for No. 3 Column on Operation Longcloth. Very little is known about Dr. Rao, apart from his very real devotion in keeping the Gurkha Rifles of 3 Column fit and well during the first Chindt expedition. He was part of Flight Officer Robert Thompson's dispersal group which finally exited Burma in mid-April 1943.

Harold James described the Indian doctor in his book, Across the Threshold of Battle: our medical officer from the Indian Medical Service was Captain Rao and came from Southern India, he was so thin that he looked as though he would snap in two at the slightest touch. In reality he was a very tough, good humoured and and excellent doctor.

It is not known whether Dr. Rao continued to serve with the Chindits after Operation Longcloth, or indeed if he survived the war and returned home to Southern India.

Rifleman Gaubahdur Gurung. This soldier served with No. 13 Platoon in 3 Column on Operation Longloth and then continued his war with the battalion in the Arakan in 1944. It is believed that Gaubahadur survived the war and returned home to Nepal.

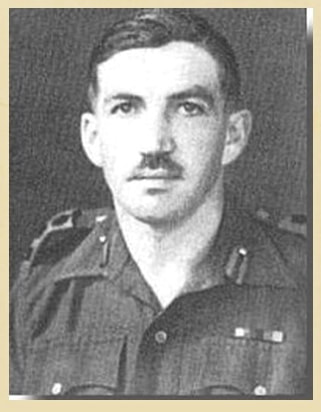

Captain Taffy Griffiths.

Captain Taffy Griffiths.

Captain William Douglas Griffiths

William Douglas Griffiths was born on the 23rd April 1916. He had worked with the Forestry Commission in Burma before the war.

He was commissioned as 2nd Lieutenant, service number (ABRO 83) on the 10th November 1939 and attached to the 1st Battalion, the Burma Rifles. He served as a Company Commander with the 13th Shan States Battalion (Burma Territorial Force) during 1940, before acting as Quartermaster and returning to the 1st Battalion of the Burma Rifles in early 1941. He was promoted to full Lieutenant on the 12th November 1941.

In April 1942, having become sick or wounded, Taffy, as he was affectionatle known to his friends and comrades had been evacuated to Bhamo on the Irrawaddy. From here, he was escorted with other military and civilian evacuees to Myitkhina in readiness to leave Burma for India. On the 5th May, in the company of fellow officer, Major Edward Hewitt Cooke (9th Burma Rifles), William found himself on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy opposite Myitkhina. Major Cooke remembered that: Griffiths was unable to walk well owing to leg injuries, but still refused to go ahead and seek a seat on one of the planes leaving Myitkhina. Later that same day, Cooke and Griffiths were sitting in a Ford V8 car as it was being transported over the river on a raft. A storm had broken as they were crossing and the car rolled off the raft and into the river.

Thankfully, both men were hauled out of the submerged vehicle and dragged to the safety of the eastern bank, however, others in the car could not get out in time and were drowned. Taffy Griffiths had lost all his possessions in the Irrawaddy, including his vitally needed glasses. This must have hampered him on the long trek out of Burma through the Hukawng Valley to India.

In Harold James' book, Across the Threshold of Battle, the author recalled:

On our crossing of the Irrawaddy River in April 1943, about half-way across I noticed that Taffy had become very agitated. I could tell he was terrified. He proceeded to tell me that during the retreat the previous year, he had been sitting in the cab of a truck while crossing the Irrawaddy and it had sunk. Not been able to swim, he had been trapped and taken down into the depths of the river and it was only the presence of a strong swimmer and a Burmese boatman that had saved him from drowning that day.

William was promoted to Temporary Captain on the 1st October 1942 and joined the 2nd Battalion, the Burma Rifles at the Saugor training camp, as the battalion prepared for the first Wingate expedition, Operation Longcloth. As we already know, William was posted to lead the Burma Rifles Section in No. 3 Column under the command of Major Mike Calvert. He had also taken part in a pre-operational reconnaissance of the area just east of the Chindwin River in early January 1943, to seek out suitable locations for supply drops for the forthcoming expedition and to ascertain the demeanour of the local Burmese towards any British re-invasion of this territory. In fact Griffiths was the first Chindt to draw blood in 1943, when on the 10th January he killed two Japanese scouts on the outskirts of Paungbyin village.

For his efforts in 1943, Captain Griffiths was awarded the Military Cross (London Gazette 16th December 1943).

ABRO 83 Lieutenant (temporary Captain) William Douglas Griffiths

Brigade-77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

Corps-4th Corps

Unit-Army in Burma Reserve of Officers attached, 2nd Battalion, The Burma Rifles

Action for which recommended:

On 6th March 1943, at Nankan railway station, this officer was left with a small party consisting of one section of Gurkhas and a few Burma Riflemen to guard a track which afterwards proved to be the main Indaw Road, while the Column carried out demolitions on the railway. Two lorry loads of enemy troops arrived and were successfully ambushed. Captain Griffiths continued to fight the enemy for two hours while the demolition work continued, until the enemy was reinforced, when he eventually withdrew without casualties, having destroyed three Japanese lorries and counted fourteen enemy corpses.

Throughout the campaign this officer showed great coolness and soundness of judgement. Thanks to his foresight and his capable leadership, the platoon of Burma Rifles under his command furnished completely reliable information of the enemy, and enabled his Column to move through enemy country unmolested save on one occasion. His handling of his men in action was excellent.

Recommended by-Major J.M.Calvert, R.E. Column Commander-77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

Signed by-Brigadier O.C. Wingate. Commander 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

It is known that William served again on the second Chindit expedition in 1944 (Operation Thursday). Once again he teamed up with Mike Calvert in 77 Brigade, but it is not clear which column he was posted to that year.

From the book, To Blazes with Glory, by Joe Milner (82 Column in 1944):

At that moment, Major Taffy Griffiths strolled over to brief my platoon on our approach to Henu (White City). He was instantly recognisable by his bushy moustache. Most Chindit officers need no introduction, their reputations, eccentricities and exploits travelled well before them. Taffy, a former Burma forestry officer was one these men. He had been through Wingate's campaign the previous year and his jungle lore had become legendary, and he was a trusted confidante of the Kachin tribal leaders.

William Griffiths died aged 65, in the winter of 1981 whilst living in the London Borough of Westminister.

I would like to thank Steve Rothwell, for all his help in bringing together the above information in regards to Captain William Griffiths MC and his wartime service.

William Douglas Griffiths was born on the 23rd April 1916. He had worked with the Forestry Commission in Burma before the war.

He was commissioned as 2nd Lieutenant, service number (ABRO 83) on the 10th November 1939 and attached to the 1st Battalion, the Burma Rifles. He served as a Company Commander with the 13th Shan States Battalion (Burma Territorial Force) during 1940, before acting as Quartermaster and returning to the 1st Battalion of the Burma Rifles in early 1941. He was promoted to full Lieutenant on the 12th November 1941.

In April 1942, having become sick or wounded, Taffy, as he was affectionatle known to his friends and comrades had been evacuated to Bhamo on the Irrawaddy. From here, he was escorted with other military and civilian evacuees to Myitkhina in readiness to leave Burma for India. On the 5th May, in the company of fellow officer, Major Edward Hewitt Cooke (9th Burma Rifles), William found himself on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy opposite Myitkhina. Major Cooke remembered that: Griffiths was unable to walk well owing to leg injuries, but still refused to go ahead and seek a seat on one of the planes leaving Myitkhina. Later that same day, Cooke and Griffiths were sitting in a Ford V8 car as it was being transported over the river on a raft. A storm had broken as they were crossing and the car rolled off the raft and into the river.

Thankfully, both men were hauled out of the submerged vehicle and dragged to the safety of the eastern bank, however, others in the car could not get out in time and were drowned. Taffy Griffiths had lost all his possessions in the Irrawaddy, including his vitally needed glasses. This must have hampered him on the long trek out of Burma through the Hukawng Valley to India.

In Harold James' book, Across the Threshold of Battle, the author recalled:

On our crossing of the Irrawaddy River in April 1943, about half-way across I noticed that Taffy had become very agitated. I could tell he was terrified. He proceeded to tell me that during the retreat the previous year, he had been sitting in the cab of a truck while crossing the Irrawaddy and it had sunk. Not been able to swim, he had been trapped and taken down into the depths of the river and it was only the presence of a strong swimmer and a Burmese boatman that had saved him from drowning that day.

William was promoted to Temporary Captain on the 1st October 1942 and joined the 2nd Battalion, the Burma Rifles at the Saugor training camp, as the battalion prepared for the first Wingate expedition, Operation Longcloth. As we already know, William was posted to lead the Burma Rifles Section in No. 3 Column under the command of Major Mike Calvert. He had also taken part in a pre-operational reconnaissance of the area just east of the Chindwin River in early January 1943, to seek out suitable locations for supply drops for the forthcoming expedition and to ascertain the demeanour of the local Burmese towards any British re-invasion of this territory. In fact Griffiths was the first Chindt to draw blood in 1943, when on the 10th January he killed two Japanese scouts on the outskirts of Paungbyin village.

For his efforts in 1943, Captain Griffiths was awarded the Military Cross (London Gazette 16th December 1943).

ABRO 83 Lieutenant (temporary Captain) William Douglas Griffiths

Brigade-77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

Corps-4th Corps

Unit-Army in Burma Reserve of Officers attached, 2nd Battalion, The Burma Rifles

Action for which recommended:

On 6th March 1943, at Nankan railway station, this officer was left with a small party consisting of one section of Gurkhas and a few Burma Riflemen to guard a track which afterwards proved to be the main Indaw Road, while the Column carried out demolitions on the railway. Two lorry loads of enemy troops arrived and were successfully ambushed. Captain Griffiths continued to fight the enemy for two hours while the demolition work continued, until the enemy was reinforced, when he eventually withdrew without casualties, having destroyed three Japanese lorries and counted fourteen enemy corpses.

Throughout the campaign this officer showed great coolness and soundness of judgement. Thanks to his foresight and his capable leadership, the platoon of Burma Rifles under his command furnished completely reliable information of the enemy, and enabled his Column to move through enemy country unmolested save on one occasion. His handling of his men in action was excellent.

Recommended by-Major J.M.Calvert, R.E. Column Commander-77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

Signed by-Brigadier O.C. Wingate. Commander 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

It is known that William served again on the second Chindit expedition in 1944 (Operation Thursday). Once again he teamed up with Mike Calvert in 77 Brigade, but it is not clear which column he was posted to that year.

From the book, To Blazes with Glory, by Joe Milner (82 Column in 1944):

At that moment, Major Taffy Griffiths strolled over to brief my platoon on our approach to Henu (White City). He was instantly recognisable by his bushy moustache. Most Chindit officers need no introduction, their reputations, eccentricities and exploits travelled well before them. Taffy, a former Burma forestry officer was one these men. He had been through Wingate's campaign the previous year and his jungle lore had become legendary, and he was a trusted confidante of the Kachin tribal leaders.

William Griffiths died aged 65, in the winter of 1981 whilst living in the London Borough of Westminister.

I would like to thank Steve Rothwell, for all his help in bringing together the above information in regards to Captain William Griffiths MC and his wartime service.

Returning once more to the life of Harold James. Harold lived for a while in Hartney Whitney, a village in the Hart district of Hampshire and worked as Press Officer for the Automobile Association. He has written several books, mostly on the subject of his beloved Gurkha Rifles and some of these with fellow Gurkha officer, Denis Sheil-Small.

Some of his titles include:

The Gurkhas, published in 1965

A Pride of Gurkhas, first published in 1975

Across the Threshold of Battle in 1993

A House in Kathmandu in 1997

The Scorpion Trap (a novel) in 2010.

On the 22nd January 1992, Harold was invited by the Imperial War Museum to record an audio narrative about his experiences in WW2. This interview can be listened to online, by clicking the following link: www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80012137

In the early 1990's, Harold began to entertain the idea of moving to Nepal to live and building a house in the capital, Kathmandu. This he achieved in late 1995, when the house, which he named Tamjam was blessed by a group of Tibetan lamas from the Samtenling Monastry. To my knowledge, Harold was still living out in Nepal in 2014.

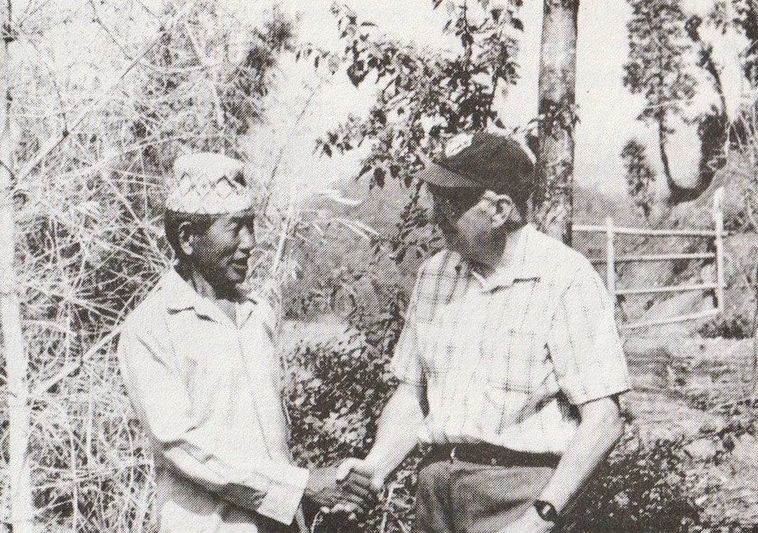

In 1992, after a conversation with fellow Chindit veteran, Dominic Neill, Harold arranged a meeting in Nepal with Sherbahadur Ale, his old comrade and former Bren gunner from No. 3 Column on Operation Longcloth.

From the pages of Across the Threshold of Battle:

The person I most wanted to meet again was Sherbahadur Ale, just to talk of that day we shared the Bren-gun on the Irrawaddy. Of course I had completely lost touch with him. But Nick Neill (8 Column Transport Officer in 1943) said triumphantly, I have his address in Nepal. Later on he became my Gurkha Major and he is an old friend. In fact when Margaret and I were in Nepal in the 1970's we visited him. Since then I have sent him a Christmas card every year. I don't hear from him of course, but I think he must still be alive.

I sensed that there was a reasonable chance of making my wish come true. I had recently returned from a holiday in Nepal, if only I had known then. But there was a possibility that I would be returning in 1992; so I took down the address excitedly. I asked my excellent Nepali guide, Karna Bahadur Tamang, to write to Sherbahadur. There was no reply to his first letter. He wrote again, by registered post, but still without success, and my hopes began to fade. Then I met Alastair Langlands (former 8th Gurkha Rifles and Gurkha Welfare) in the Spring of 1991, when he was in England on leave from Nepal. He pointed out that if Sherbahadur was still alive he would have to collect his army pension regularly from the British Gurkha Depot in Pokhara. And as Alastair lived at the depot he promised to make enquiries.

At last Sherbahadur visited Alastair at the depot, and said that he would be quite willing to meet me. Although, apparently, he could not quite put a face to my name. Karna then made a personal trip to meet Sherbahadur and arrange a rendezvous; being regaled for several hours with tales of Army days with the Gurkhas, Sherbahadur was still not able to put a face to my name. The actual incidents on the Irrawaddy and on the return journey he had not forgotten.

So it was arranged, and I must confess to being excited and anxious at meeting Sherbahadur. He would now be seventy-four, although Karna told me he was very good for his age. Coming face to face with someone after fifty years, especially as we had once shared a very dangerous episode in our lives, is a weird experience. Seeing Sherbahadur in his traditional Nepali clothes and so much older was, for that moment, like meeting a complete stranger. But quite suddenly as he grasped my hands in his, the years seemed to rush back and his face took on that somewhat cheeky look I remembered so well, and in particular I could recall the eyes, crinkling up at the sides.

I know you now, Sahib, he exclaimed with delight. The very young officer from the 8th Gurkha Rifles. Short like a Gurkha, strong, always moving quickly, very fit. Giving us lots of shabash (praise). Well done! Well done! Much slimmer than you are now, Sahib.

So we talked as old friends will, although he did most of the talking as we relived those desperate moments in the jungle. He was most graphic in his descriptions; the sound of a machine-gun punctuated his words. Behind us were serrated lines of hills, beyond which towered the white Himalayan mountain tops of the Annapurna range, and the most beautiful Machhapuchhre, the Fish Tail Mountain: a vastly different background to our last meeting in tropical jungle. He had picked up a delightful characteristic from some British officer of the past. After every passage of narrative he would say, in English and in a much deeper voice, Is it not correct, Sahib? Yes, it is correct. His recollections of the Chindits and the actions of No. 3 Column were almost the same as mine.

It seemed as if the impression made on our minds had been equally strong. A passage of time quite impossible to erase, even if sometimes the wish to do so was quite keen. Calvert was somebody he had not forgotten, could not forget. He spoke of Calvert in glowing terms, still remembering how well he had led the column. There were sad moments too when we spoke of those who had died. And eventually the all too sad moment when we finally had to say goodbye.

He grasped my hands fiercely again, You must come back next year to see me Sahib.

Will you still he here? I asked.

Why not, Sahib, I am seventy-four but very fit. And you look very fit, not as much as in those days but all right, I think.

I promised to come back.

It has been clear to me, as I have read through the many books written by ex-Gurkha officers who served with the first Wingate expedition, just how much they respect and indeed adore the Gurkha Riflemen they have commanded. To conclude this narrative, here is another quote from Harold James' book, Across the Threshold of Battle, in which he recounts another conversation he had with his old friend and Chindit comrade, Dominic Neill.

Nick Neill informed me that at the end of the war, his Orderly had told him that when a Gurkha soldier returns home to his village in Nepal, all the children would come out from their houses and hail the returning man with the cry, Lahure ayo! Lahure ayo! A soldier has come! A soldier has come!

Nick told me how much this story saddened him, when he remembered all the men from his time in Burma who were never able to enjoy such a welcome. This then made me sad to think of Havildar Til Bir Thapa and so many Gurkhas from my first command, who had died in the elephant grass at the Irrawaddy and fighting so bravely during the ambush at Pago, and who would also never return home to the cries of Lahure ayo!

Update 11/12/2023.

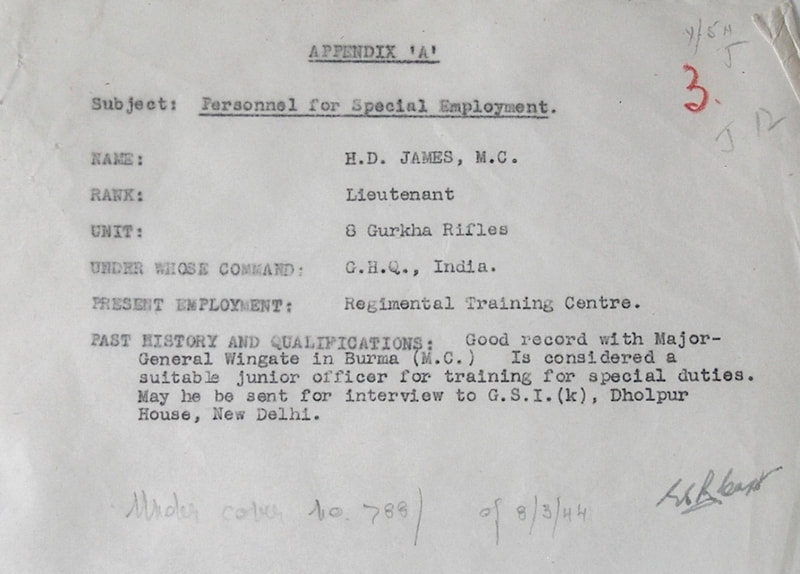

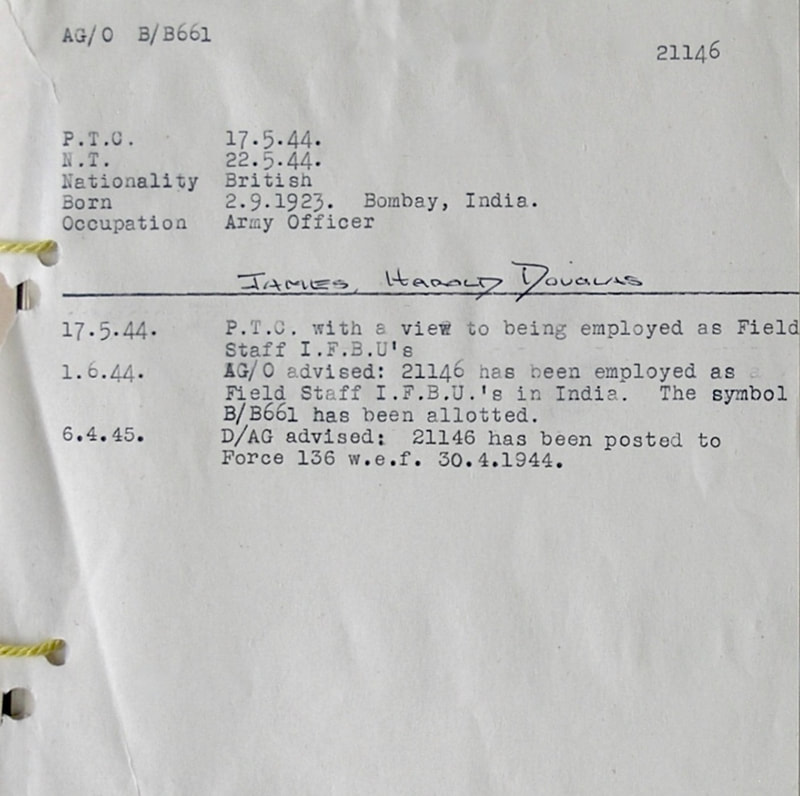

The Special Operative Executive (SOE) file for Harold Douglas James was recently (October 2023) declassified, on the 100th year anniversary since his birth on the 2nd September 1923. Many thanks to Steven Kippax and Richard Duckett for the actual delivery of the document into the website author's hands.

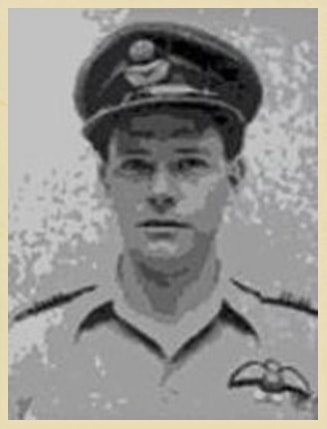

Temporary Captain, (10610) Harold D. James of the 8th Gurkha Rifles was interviewed for a role with Force 136 at New Delhi in March 1944, originally with a view to him working in the FBU (Field Broadcasting Unit). This opportunity had arisen after his well recognised performance on Operation Longcloth with 3/2 Gurkha Rifles and the award of the Military Cross for his efforts in Burma in 1943. After a short period training with the 3/6 Gurkha Rifles (77 Indian Infantry Brigade) in late 1943 and in preparation for the second Wingate expedition, Harold returned once more to the 8th Gurkhas in January 1944.

It was from here that he applied and successfully joined Force 136, where he worked as a Patrol Captain with No. 3 FPU (Field Photographic Unit), leading Indian troops in the Arakan region of Burma. His valuable knowledge of both Urdu and Ghurkali made him a natural and competent leader of Indian troops in this new role of disinformation and propaganda. He remained with Force 136 until the end of the war. Seen below are two documents in relation to his time with Force 136. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

The Special Operative Executive (SOE) file for Harold Douglas James was recently (October 2023) declassified, on the 100th year anniversary since his birth on the 2nd September 1923. Many thanks to Steven Kippax and Richard Duckett for the actual delivery of the document into the website author's hands.

Temporary Captain, (10610) Harold D. James of the 8th Gurkha Rifles was interviewed for a role with Force 136 at New Delhi in March 1944, originally with a view to him working in the FBU (Field Broadcasting Unit). This opportunity had arisen after his well recognised performance on Operation Longcloth with 3/2 Gurkha Rifles and the award of the Military Cross for his efforts in Burma in 1943. After a short period training with the 3/6 Gurkha Rifles (77 Indian Infantry Brigade) in late 1943 and in preparation for the second Wingate expedition, Harold returned once more to the 8th Gurkhas in January 1944.

It was from here that he applied and successfully joined Force 136, where he worked as a Patrol Captain with No. 3 FPU (Field Photographic Unit), leading Indian troops in the Arakan region of Burma. His valuable knowledge of both Urdu and Ghurkali made him a natural and competent leader of Indian troops in this new role of disinformation and propaganda. He remained with Force 136 until the end of the war. Seen below are two documents in relation to his time with Force 136. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, December 2018.