Sergeant Jack Berry, a Chindit Twice Over

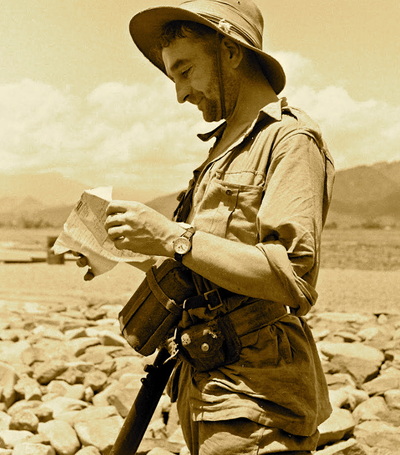

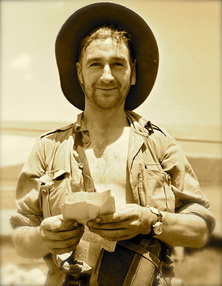

Sgt. Jack Berry, April 1943.

Sgt. Jack Berry, April 1943.

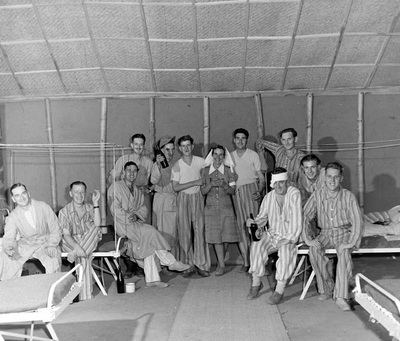

At 11.00 hours on the 28th April 1943 a C47 Dakota aircraft landed in a jungle clearing a few miles west of the Irrawaddy township of Bhamo. Eighteen sick and wounded men from 8 Column boarded the plane and flew out to the safety of India. This incident and the associated photographs has become one of the most recognisable and iconic stories to come out of the first Chindit operation.

Of the eighteen men airlifted to safety that day, only one, 3780480 Sgt. Jack Berry made a full enough recovery to take part in the second Wingate expedition the following year. Jack had served with Northern Group Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth, this unit was led by Lt. Colonel S.A. Cooke the most senior officer with the 13th King's in 1943. Sgt. Berry would have been the senior NCO in one of the Head Quarters platoons, second in command to the platoon officer, most probably a Lieutenant.

The story of the Dakota rescue plane has been featured many times on the pages of this website and is covered in enough detail elsewhere, so as not to need repeating here. To read more about the incident, please click on the following link: The Piccadilly Incident

After landing back in Assam, the casualties from the Dakota were transferred by road to the 19th Casualty Clearing Station at Imphal, which was run at that time by Matron Agnes McGearey. Most of the men with Sgt. Berry were either suffering from a wound of some kind, inflicted upon them by previous skirmishes with the Japanese, or were debilitated by one of the tropical diseases prevalent in the Burmese jungle at that time. It is not known precisely why Jack was included in the party to board the plane, my guess is that he too had contracted one of the common afflictions of the day; malaria, dysentery or perhaps severe jungle sores.

Whatever the reason, he clearly made a full recovery and went into Burma again in 1944 on the second Chindit operation. Jack remained with King's Regiment, serving this time with the 1st Battalion under the command of Lt. Colonel Walter Purcell Scott who had been in charge of 8 Column the previous year and had been responsible for calling in the rescue plane. I believe Jack was a member of 82 Column, part of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade in 1944. 82 Column was commanded by Major Richard Gaitley of the King's Regiment. The two King's columns (81 and 82) flew into Burma on the 5th March 1944 in a series of glider landings, with orders to form a secure base in a jungle clearing which became known as Broadway.

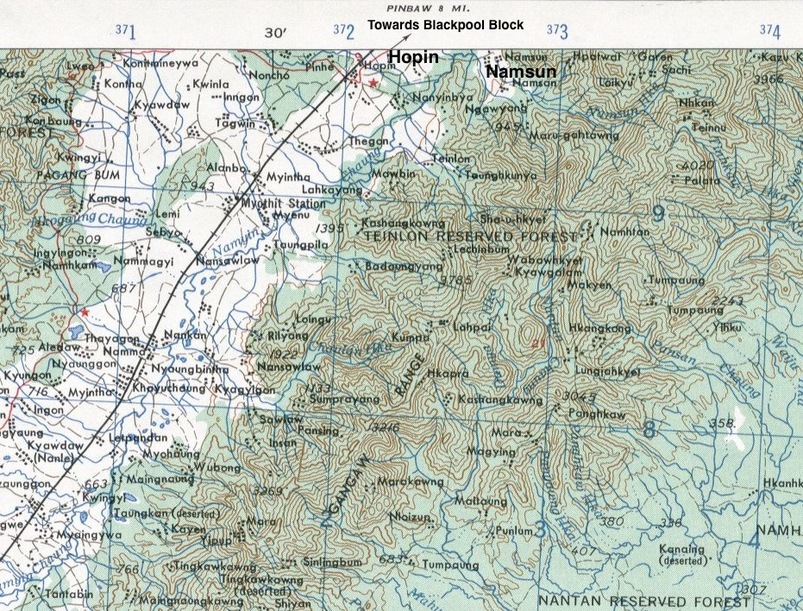

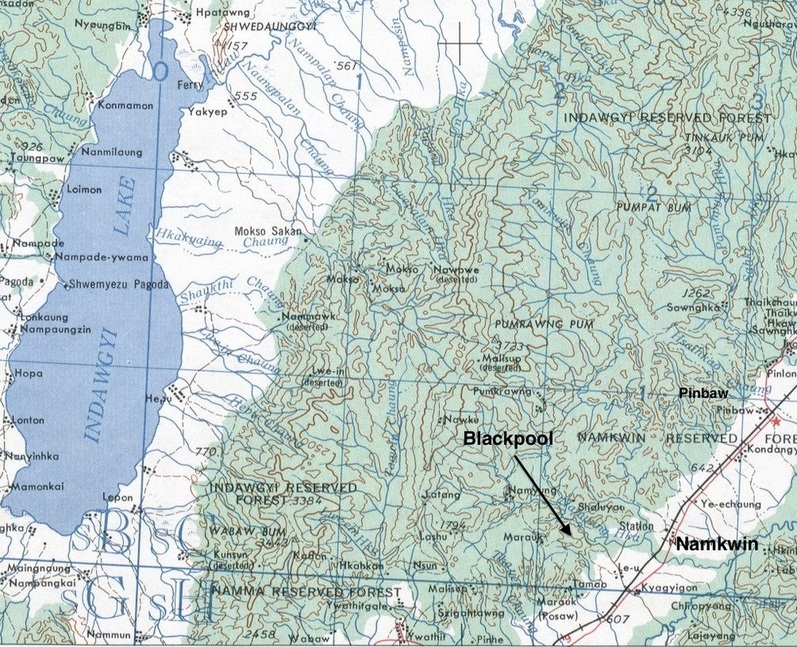

The King's were ordered to secure the perimeter of the new Chindit stronghold and put up a defensive shield around the jungle clearing. This they achieved with great efficiency and valour. In mid-May, Columns 81 and 82 were ordered to head out of Broadway and travel north to join up with another Chindit unit, the 111th Indian Infantry Brigade at their own base codenamed Blackpool. After a few days travelling, the King's were ambushed by a Japanese patrol on the 19th May as they were crossing the Hopin-Pinbaw Road near a village called Namsun. This attack by the enemy caused a split in the column file, resulting in the separation of around 100 men. As the leading section of the King's (mostly from 81 Column) pushed on towards Blackpool, the rear of the column was attacked again by the Japanese on the the 21st May.

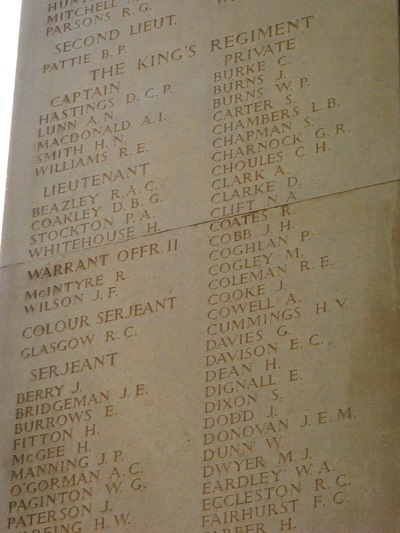

It was somewhere close to the village of Namsun that Sgt. Jack Berry was killed. He was one of around 25-30 casualties suffered by the King's over the period 19-21st May 1944.

Of the eighteen men airlifted to safety that day, only one, 3780480 Sgt. Jack Berry made a full enough recovery to take part in the second Wingate expedition the following year. Jack had served with Northern Group Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth, this unit was led by Lt. Colonel S.A. Cooke the most senior officer with the 13th King's in 1943. Sgt. Berry would have been the senior NCO in one of the Head Quarters platoons, second in command to the platoon officer, most probably a Lieutenant.

The story of the Dakota rescue plane has been featured many times on the pages of this website and is covered in enough detail elsewhere, so as not to need repeating here. To read more about the incident, please click on the following link: The Piccadilly Incident

After landing back in Assam, the casualties from the Dakota were transferred by road to the 19th Casualty Clearing Station at Imphal, which was run at that time by Matron Agnes McGearey. Most of the men with Sgt. Berry were either suffering from a wound of some kind, inflicted upon them by previous skirmishes with the Japanese, or were debilitated by one of the tropical diseases prevalent in the Burmese jungle at that time. It is not known precisely why Jack was included in the party to board the plane, my guess is that he too had contracted one of the common afflictions of the day; malaria, dysentery or perhaps severe jungle sores.

Whatever the reason, he clearly made a full recovery and went into Burma again in 1944 on the second Chindit operation. Jack remained with King's Regiment, serving this time with the 1st Battalion under the command of Lt. Colonel Walter Purcell Scott who had been in charge of 8 Column the previous year and had been responsible for calling in the rescue plane. I believe Jack was a member of 82 Column, part of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade in 1944. 82 Column was commanded by Major Richard Gaitley of the King's Regiment. The two King's columns (81 and 82) flew into Burma on the 5th March 1944 in a series of glider landings, with orders to form a secure base in a jungle clearing which became known as Broadway.

The King's were ordered to secure the perimeter of the new Chindit stronghold and put up a defensive shield around the jungle clearing. This they achieved with great efficiency and valour. In mid-May, Columns 81 and 82 were ordered to head out of Broadway and travel north to join up with another Chindit unit, the 111th Indian Infantry Brigade at their own base codenamed Blackpool. After a few days travelling, the King's were ambushed by a Japanese patrol on the 19th May as they were crossing the Hopin-Pinbaw Road near a village called Namsun. This attack by the enemy caused a split in the column file, resulting in the separation of around 100 men. As the leading section of the King's (mostly from 81 Column) pushed on towards Blackpool, the rear of the column was attacked again by the Japanese on the the 21st May.

It was somewhere close to the village of Namsun that Sgt. Jack Berry was killed. He was one of around 25-30 casualties suffered by the King's over the period 19-21st May 1944.

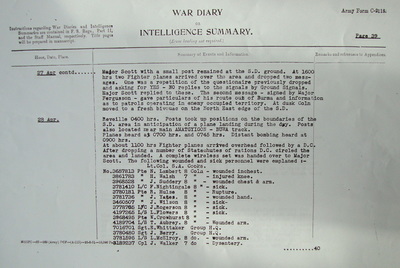

Several witness statements exist in regards to the ambush at Namsun, which explain what happened to many of the soldiers lost when 82 Column inadvertently bumped into the Japanese patrol whilst crossing the motor road. For example, Major O.A. Evans, an officer with the column had this to report about his colleague, Sgt. Paterson of the King's Regiment:

On the night of the 19/20th May 1944, it was the intention of 82 Column to march from their bivouac near Namsun to Blackpool. At 1900 hours, the Column halted at Namsun until dark. Paterson's Section was marching in front of the Machine Gun Section. At about 2300 hours, whilst the Column was crossing the road near milestone 35, between Pinbaw and Hopin, a Japanese convoy bumped into the Column. An engagement took place in the dark and I last saw this NCO (Paterson) in the twilight at Namsun. His Section had not crossed the road at the time of the engagement. When I checked up on the personnel who were near me at the time, Paterson was missing. He did not appear at the rendezvous the next day.

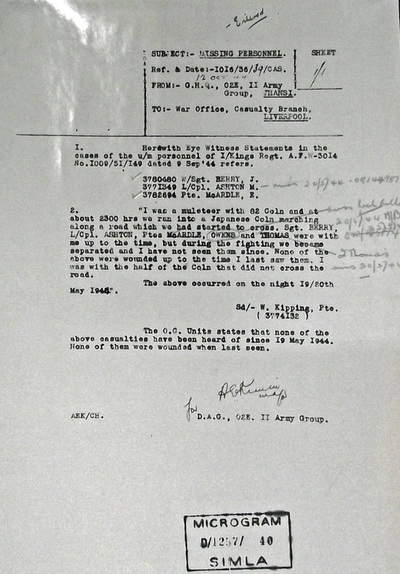

In the case of Sgt. Jack Berry; on the 9th September 1944, Pte. 3774132 W. Kipping produced the following witness statement for the Army Investigation Bureau, who were piecing together the last known whereabouts of the men missing from the King's Regiment on Operation Thursday:

Herewith, are eye witness statements in the cases of the undermentioned personnel of the 1st King's Regiment:

3780480 W/Sgt. J. Berry

3771349 L/Cpl. M. Ashton

3782694 Pte. E. McArdle

I was a muleteer with 82 Column and at about 2300 hours we ran into a Japanese Column marching along a road which we had started to cross. Sgt. Berry, L/Cpl. Ashton and Ptes. McArdle, Owens and Thomas were with me up to that time, but during the fighting we became separated and I have not seen them since. None of the above were wounded up to the time I last saw them. I was with the half of the column that did not cross the road. The above occurred on the night of the 19/20th May 1944.

A sub-note to Kipping's account reiterates that: The O.C. Units states that none of the above mentioned casualties have been heard of since 19th May 1944. None of them were wounded when last seen.

In Pte. Kipping's report, he states that he was with the section of the column that did not cross the road that evening. The 100 or so men that did not cross the road, diverted away from the march towards Blackpool and instead took up the option of another pre-arranged rendezvous set roughly north-east. Eventually, this group met up with Brigadier Mike Calvert and later took part in the battle for Mogaung in June 1944.

Another soldier serving with the 1st Battalion of The King's Regiment in 1944, was Ken Davenport. He spoke with Philip Chinnery in the course of the research for the author's book, March or Die, which was first published in 1997. During these discussions Ken recalled the night of the 19th May:

It was dark when our column reached the road. We took up our positions and let the ponies with the sick and wounded and the mules cross. Then, as our section waited as the rest of the column passed through, we heard the sound of marching feet only a few yards away. Our Sergeant-Major shouted "Halt" three times and then all hell broke loose. Part of the column went back into the jungle with the Japs on their heels, the rest, including Corporal Bibby and myself, crossed the road safely and continued on to Blackpool. He was later killed by a mortar bomb; he was from Blackpool and he lost his life in the battle of Blackpool.

Rightly or wrongly, Major Gaitley was held accountable for the disaster at Namsun and he was removed from the column and flown out to India. The 1st King's stay at Blackpool was fairly short-lived and after some of the most brutal fighting in absolutely atrocious weather conditions, the Blackpool Stronghold was abandoned on the 25th May 1944.

On the night of the 19/20th May 1944, it was the intention of 82 Column to march from their bivouac near Namsun to Blackpool. At 1900 hours, the Column halted at Namsun until dark. Paterson's Section was marching in front of the Machine Gun Section. At about 2300 hours, whilst the Column was crossing the road near milestone 35, between Pinbaw and Hopin, a Japanese convoy bumped into the Column. An engagement took place in the dark and I last saw this NCO (Paterson) in the twilight at Namsun. His Section had not crossed the road at the time of the engagement. When I checked up on the personnel who were near me at the time, Paterson was missing. He did not appear at the rendezvous the next day.

In the case of Sgt. Jack Berry; on the 9th September 1944, Pte. 3774132 W. Kipping produced the following witness statement for the Army Investigation Bureau, who were piecing together the last known whereabouts of the men missing from the King's Regiment on Operation Thursday:

Herewith, are eye witness statements in the cases of the undermentioned personnel of the 1st King's Regiment:

3780480 W/Sgt. J. Berry

3771349 L/Cpl. M. Ashton

3782694 Pte. E. McArdle

I was a muleteer with 82 Column and at about 2300 hours we ran into a Japanese Column marching along a road which we had started to cross. Sgt. Berry, L/Cpl. Ashton and Ptes. McArdle, Owens and Thomas were with me up to that time, but during the fighting we became separated and I have not seen them since. None of the above were wounded up to the time I last saw them. I was with the half of the column that did not cross the road. The above occurred on the night of the 19/20th May 1944.

A sub-note to Kipping's account reiterates that: The O.C. Units states that none of the above mentioned casualties have been heard of since 19th May 1944. None of them were wounded when last seen.

In Pte. Kipping's report, he states that he was with the section of the column that did not cross the road that evening. The 100 or so men that did not cross the road, diverted away from the march towards Blackpool and instead took up the option of another pre-arranged rendezvous set roughly north-east. Eventually, this group met up with Brigadier Mike Calvert and later took part in the battle for Mogaung in June 1944.

Another soldier serving with the 1st Battalion of The King's Regiment in 1944, was Ken Davenport. He spoke with Philip Chinnery in the course of the research for the author's book, March or Die, which was first published in 1997. During these discussions Ken recalled the night of the 19th May:

It was dark when our column reached the road. We took up our positions and let the ponies with the sick and wounded and the mules cross. Then, as our section waited as the rest of the column passed through, we heard the sound of marching feet only a few yards away. Our Sergeant-Major shouted "Halt" three times and then all hell broke loose. Part of the column went back into the jungle with the Japs on their heels, the rest, including Corporal Bibby and myself, crossed the road safely and continued on to Blackpool. He was later killed by a mortar bomb; he was from Blackpool and he lost his life in the battle of Blackpool.

Rightly or wrongly, Major Gaitley was held accountable for the disaster at Namsun and he was removed from the column and flown out to India. The 1st King's stay at Blackpool was fairly short-lived and after some of the most brutal fighting in absolutely atrocious weather conditions, the Blackpool Stronghold was abandoned on the 25th May 1944.

In early August 2016, I was delighted to receive an email contact from John Berry, the nephew of Sgt. Jack Berry of the King's Regiment:

I was interested to see the photograph of Sgt. Jack Berry on your website. He was my uncle, but was sadly killed in action in Burma. Any information you could provide would be most appreciated.

After exchanging several emails with John, I was able to pass on all the photographs, paperwork and documentation I possessed in relation to Jack and his time with the Chindits. In return, John sent me some photographs of Jack from before the war. He also told me:

Jack was born in Salford and lived at 73, Stapleton Street, Irlams O'th' Height. He was one of eleven children a number of whom served in the forces during WW2. I don't know a great amount about Jack, as he was killed before I was born. My sister who is 83 may have some more information, so I'll speak to her. I do have a very delicate press cutting from the Picture Post of Jack which I will scan and send over to you, plus any other photographs I may have.

Thank you so much for the images you have sent. Our family can't thank you enough, as the story of Jack always brought heartache to his siblings. The story of our family is one of absolute commonality, but is also extraordinary in a way that's hard to comprehend. I feel humbled and privileged to have shared these stories. Once again, many thanks.

To complete this story, seen below are some of the photographs and other images mentioned in the above narrative. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

I was interested to see the photograph of Sgt. Jack Berry on your website. He was my uncle, but was sadly killed in action in Burma. Any information you could provide would be most appreciated.

After exchanging several emails with John, I was able to pass on all the photographs, paperwork and documentation I possessed in relation to Jack and his time with the Chindits. In return, John sent me some photographs of Jack from before the war. He also told me:

Jack was born in Salford and lived at 73, Stapleton Street, Irlams O'th' Height. He was one of eleven children a number of whom served in the forces during WW2. I don't know a great amount about Jack, as he was killed before I was born. My sister who is 83 may have some more information, so I'll speak to her. I do have a very delicate press cutting from the Picture Post of Jack which I will scan and send over to you, plus any other photographs I may have.

Thank you so much for the images you have sent. Our family can't thank you enough, as the story of Jack always brought heartache to his siblings. The story of our family is one of absolute commonality, but is also extraordinary in a way that's hard to comprehend. I feel humbled and privileged to have shared these stories. Once again, many thanks.

To complete this story, seen below are some of the photographs and other images mentioned in the above narrative. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank John Berry for his help in bringing the story of his Uncle Jack to these website pages. Whilst constructing this narrative, it certainly occurred to me, that although we do not know exactly what happened to Sgt. Berry in May 1944 or how he died; what we do possess is a wonderful photographic account of his time in Burma during the years of WW2. My thanks also go to Simon Jervis, who has a keen interest in the Burma Campaign and assisted me greatly with tracking down some of the documents shown above.

During one of our email conversations in regards to Sgt. Berry, Simon expressed a sentiment which I will share here, as a fitting epitaph for one of few Kingsmen to serve on both Chindit expeditions:

I have the highest admiration for men like Jack Berry who, having taken part on Longcloth could have bowed out gracefully having done their bit, but these were not ordinary men. I doubt that men such as these, could have looked themselves in the mirror if they had sat out Operation Thursday when their mates were fighting and dying. Brave, brave men.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, September 2016.

During one of our email conversations in regards to Sgt. Berry, Simon expressed a sentiment which I will share here, as a fitting epitaph for one of few Kingsmen to serve on both Chindit expeditions:

I have the highest admiration for men like Jack Berry who, having taken part on Longcloth could have bowed out gracefully having done their bit, but these were not ordinary men. I doubt that men such as these, could have looked themselves in the mirror if they had sat out Operation Thursday when their mates were fighting and dying. Brave, brave men.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, September 2016.