The Memorials of Captain Alexander Inglis MacDonald

Alexander Inglis MacDonald circa 1941.

Alexander Inglis MacDonald circa 1941.

From the book, Return via Rangoon, by Philip Stibbe:

The officers of of No. 5 Column were extremely friendly, especially Alec MacDonald. Alec was a Liverpool medical student, tall, freckled, with a pleasant lazy smile and an amazing capacity for doing things without apparent effort.

Alexander Inglis MacDonald was the son of Dr. Alexander Tulloh Inglis MacDonald and Lucy Kate MacDonald and came from the town of Bootle in Merseyside, Lancashire. He attended the Merchant Taylors Boys School in Crosby, Liverpool, looking to eventually follow in his father's footsteps in the medical profession.

By the time war was declared Alexander was already studying medicine, but he decided to enlist in to the Army as an officer, eventually joining the 13th King's Liverpool on the 18th December 1940, whilst the battalion were based at Felixstowe in Suffolk and performing coastal defence duties.

After moving base several times during the following twelve month period the battalion were given orders to prepare for overseas duties in late November 1941. The unit moved up to Liverpool by train and by the 8th of December were aboard the troopship 'Oronsay' and bound for India.

The photograph seen to the left was taken aboard the 'Oronsay' in late 1941, the image was then posted home to some of the officers families when the ship was docked at Durban, South Africa. For more detailed information about the battalion's voyage to India and their activities during Chindit training, please follow this link: Voyage and Training

The officers of of No. 5 Column were extremely friendly, especially Alec MacDonald. Alec was a Liverpool medical student, tall, freckled, with a pleasant lazy smile and an amazing capacity for doing things without apparent effort.

Alexander Inglis MacDonald was the son of Dr. Alexander Tulloh Inglis MacDonald and Lucy Kate MacDonald and came from the town of Bootle in Merseyside, Lancashire. He attended the Merchant Taylors Boys School in Crosby, Liverpool, looking to eventually follow in his father's footsteps in the medical profession.

By the time war was declared Alexander was already studying medicine, but he decided to enlist in to the Army as an officer, eventually joining the 13th King's Liverpool on the 18th December 1940, whilst the battalion were based at Felixstowe in Suffolk and performing coastal defence duties.

After moving base several times during the following twelve month period the battalion were given orders to prepare for overseas duties in late November 1941. The unit moved up to Liverpool by train and by the 8th of December were aboard the troopship 'Oronsay' and bound for India.

The photograph seen to the left was taken aboard the 'Oronsay' in late 1941, the image was then posted home to some of the officers families when the ship was docked at Durban, South Africa. For more detailed information about the battalion's voyage to India and their activities during Chindit training, please follow this link: Voyage and Training

Lieutenant William Smyly.

Lieutenant William Smyly.

All officers from the 13th King's were promoted twice during this period, once aboard the 'Oronsay' as she crossed the equator heading south towards South Africa, and then again in 1942 towards the end of their training for Operation Longcloth.

Alexander was attached to Chindit Column 5 under the leadership of Major Bernard Fergusson, formerly of the Black Watch Regiment. Fergusson gave Alexander the job of Administrative Officer within the column and he performed well in this roll and became a firm favourite with the Major.

Soon it was time for the freshly trained Chindits to move out of their training camp at Saugor and up to the railway junction town of Jhansi. Here they took part in one more training exercise before being organised into large groups for the train journey to Dimapur in Assam.

On this train journey Alexander travelled with Animal Transport Officer, Bill Smyly (pictured right) and the Gurkha Officer's beloved mules. On the subject of equine animals; Bernard Fergusson, in his book about the operation in 1943 entitled, 'Beyond the Chindwin', described Alexander's riding ability as "determined rather than skilled."

Captain MacDonald had chosen as his batman, Lance Corporal Gilmartin. The two men had grown close during training and on the operation proper and respected each other's abilities in soldiering. According to Bernard Fergusson, Charles Gilmartin had been absolutely inconsolable after Captain MacDonald's death in late March 1943. He (Fergusson) believed that this sadness of heart contributed to Gilmartin's own death just a few days later in the village of Zibyugin, where the Lance Corporal had accompanied Lieutenant Duncan Campbell Menzies in an ill-fated search for food and supplies.

Here are Charles Gilmartin's CWGC details: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/3069802/GILMARTIN,%20CHARLES

To read more about Lance Corporal Gilmartin, please click on the following link and scroll down alphabetically: Roll Call F-J

During his time behind enemy lines in Burma, Alexander MacDonald was given a great deal of responsibility by Major Fergusson. On one occasion whilst the demolition personnel were busying themselves at Bonchaung Rail Station, MacDonald took full charge of the remainder of the column, leading them off to establish the next rendezvous point and bivouac. On another occasion he was in charge of the signals and communications for the column on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River, this was during the columns outward journey across the river at the village of Tigyaing.

Alexander was attached to Chindit Column 5 under the leadership of Major Bernard Fergusson, formerly of the Black Watch Regiment. Fergusson gave Alexander the job of Administrative Officer within the column and he performed well in this roll and became a firm favourite with the Major.

Soon it was time for the freshly trained Chindits to move out of their training camp at Saugor and up to the railway junction town of Jhansi. Here they took part in one more training exercise before being organised into large groups for the train journey to Dimapur in Assam.

On this train journey Alexander travelled with Animal Transport Officer, Bill Smyly (pictured right) and the Gurkha Officer's beloved mules. On the subject of equine animals; Bernard Fergusson, in his book about the operation in 1943 entitled, 'Beyond the Chindwin', described Alexander's riding ability as "determined rather than skilled."

Captain MacDonald had chosen as his batman, Lance Corporal Gilmartin. The two men had grown close during training and on the operation proper and respected each other's abilities in soldiering. According to Bernard Fergusson, Charles Gilmartin had been absolutely inconsolable after Captain MacDonald's death in late March 1943. He (Fergusson) believed that this sadness of heart contributed to Gilmartin's own death just a few days later in the village of Zibyugin, where the Lance Corporal had accompanied Lieutenant Duncan Campbell Menzies in an ill-fated search for food and supplies.

Here are Charles Gilmartin's CWGC details: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/3069802/GILMARTIN,%20CHARLES

To read more about Lance Corporal Gilmartin, please click on the following link and scroll down alphabetically: Roll Call F-J

During his time behind enemy lines in Burma, Alexander MacDonald was given a great deal of responsibility by Major Fergusson. On one occasion whilst the demolition personnel were busying themselves at Bonchaung Rail Station, MacDonald took full charge of the remainder of the column, leading them off to establish the next rendezvous point and bivouac. On another occasion he was in charge of the signals and communications for the column on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River, this was during the columns outward journey across the river at the village of Tigyaing.

As mentioned earlier, Alexander MacDonald was well liked by all in Column 5 and especially by his commander, Major Fergusson. Taken from Fergusson's book, 'Beyond the Chindwin', here is an excerpt which aptly describes the author's memories of Captain A.I. MacDonald. To offer up a little context here, the column had recently received a supply drop which included some letters and newspapers from back home.

Bernard Fergusson remembered:

"That afternoon we spent reading and re-reading our precious mail; graduating thereafter to the newspapers, and thence to the local papers. I have remarked during this war what an enormous proportion, fully 90 per cent, of the newspapers received from home by the troops are local papers.

Personally, I get more pleasure out of a local paper of a district I have never known, than out of a so-called national newspaper some two or three months old: the local ones are ageless. I read with delight the Galloway Gazettes produced by Sergeant-Major Cairns, and discussed with him and Peter, (Peter Dorans) the blackface prices of every sheep-farm in Galloway; and having disposed of them, I read Alec MacDonald's Bootle Times.

Alec was Scots-bred and Bootle-raised, but, like so many of his kind, indignantly denied any affinity with England: so much so, that Duncan Menzies and I used to taunt him with verses of a poem to which we were for ever adding new lines:

"How the pipes will skirl and tootle

When Macdonald comes to Bootle,

When he dons a tartan plaid instead of a jersey;

They will drink hot toddy daily

And will hold a special ceilidh

When Alec's boat is signalled in the Mersey."

"Teasing Alec was like pulling the ears of a spaniel: he used to pretend to get furious, but cheerfulness kept breaking through. The argument usually ended in a rough and tumble, in which Alec was in the awkward position of having to disdain, for reasons of pride, offers of help by the English present, and having at the same time to submit to severe pummellings by the Scots."

Bernard Fergusson remembered:

"That afternoon we spent reading and re-reading our precious mail; graduating thereafter to the newspapers, and thence to the local papers. I have remarked during this war what an enormous proportion, fully 90 per cent, of the newspapers received from home by the troops are local papers.

Personally, I get more pleasure out of a local paper of a district I have never known, than out of a so-called national newspaper some two or three months old: the local ones are ageless. I read with delight the Galloway Gazettes produced by Sergeant-Major Cairns, and discussed with him and Peter, (Peter Dorans) the blackface prices of every sheep-farm in Galloway; and having disposed of them, I read Alec MacDonald's Bootle Times.

Alec was Scots-bred and Bootle-raised, but, like so many of his kind, indignantly denied any affinity with England: so much so, that Duncan Menzies and I used to taunt him with verses of a poem to which we were for ever adding new lines:

"How the pipes will skirl and tootle

When Macdonald comes to Bootle,

When he dons a tartan plaid instead of a jersey;

They will drink hot toddy daily

And will hold a special ceilidh

When Alec's boat is signalled in the Mersey."

"Teasing Alec was like pulling the ears of a spaniel: he used to pretend to get furious, but cheerfulness kept breaking through. The argument usually ended in a rough and tumble, in which Alec was in the awkward position of having to disdain, for reasons of pride, offers of help by the English present, and having at the same time to submit to severe pummellings by the Scots."

During the third week of March 1943, Column 5 had been given orders to create a diversion for the rest of the Chindit Brigade, which was now trapped in a three-sided bag between the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers and the Mongmit-Myitson motor road to the south. Brigadier Wingate had instructed Fergusson to "trail his coat" and lead the Japanese pursuers away from the general direction of the Irrawaddy and in particular the area around the town of Inywa, where Wingate had hoped to cross.

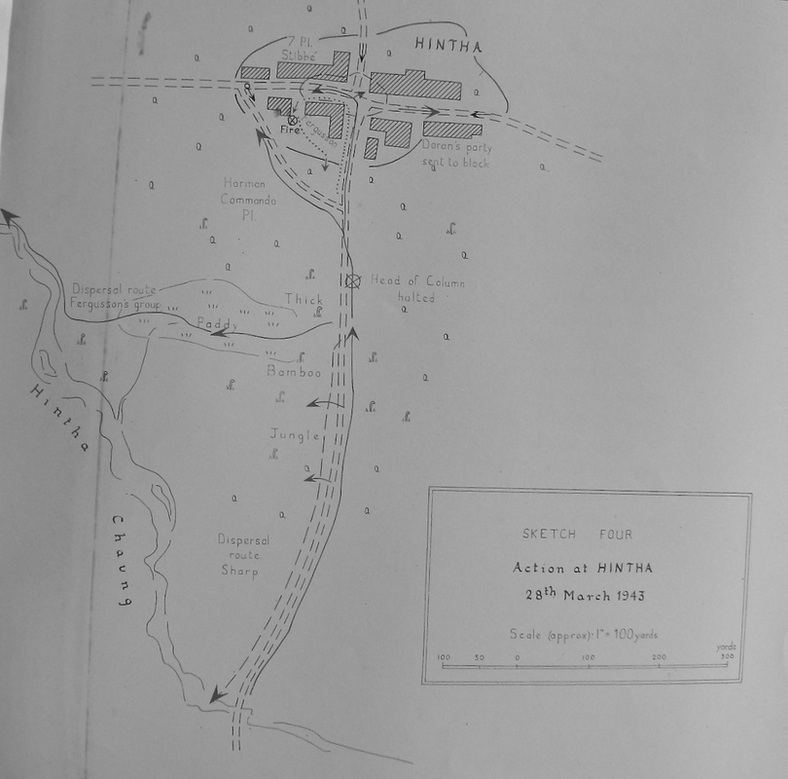

By March 28th the column had reached the village of Hintha which was situated in an area of thick and tight-set bamboo scrub. Any attempt to navigate around the settlement proved impossible, reluctantly, Fergusson decided to enter the village by the main track and check for the presence of any enemy patrols. He unluckily stumbled upon such a patrol and a fire-fight ensued.

Fighting platoons led by Lieutenant Stibbe and Jim Harman entered Hintha in an attempt to clear the road of Japanese. These were met in full force by the enemy and several casualties were taken on both sides. Stibbe, himself now wounded, returned to the base position of the column and reported to the Major that the situation was getting very hot and that the Japanese were making any forward movement extremely difficult.

Bernard Fergusson takes up the story:

"Alec Macdonald was beside me, and immediately said: "I'll have a look. Come on," and disappeared up the track. I had a feeling that, having failed on Peter Dorans' flank, the Japs would try and come in on the right, somewhere down the column; so I passed the word back to try and work a small flank guard into the jungle on that side if possible.

Then I went back to the T-junction, and made arrangements to attract all the attention we could, so as to give Alec a free run. I seemed to spend the whole action trotting up and down that seventy yards of track.

There came another burst of fire from the little track, a mixture of light machine gun, tommy-guns and grenades. The Commando Platoon alone in the column had tommy-guns, which was one of the reasons I had selected them for the role. Their cheerful rattle, however, meant that the little track was no longer clear. I hurried back to the fork, and there found Denny Sharp.

"This is going to be no good," I said. "Denny, take all the animals you can find, go back to the chaung and see if you can get down it. We'll go on playing about here to keep their attention fixed; I'll try and join you farther down the chaung, but if I don't then you know the next rendezvous point. Keep away from Chaungmido, as we don't want to get Brigade muddled up in this."

Back to the T-junction I went, and found on the right of the track the Burma Rifles platoon. They had taken two or three casualties, Jameson had one in the shoulder, and so did another splendid N.C.O., Nay Dun, whose name always made me think of a trout fly. I told John Fraser to take them back, but he must have sent them under Pam Heald, because he himself still remained with me at the end of the action.

Another casualty was Abdul the Damned. Somehow he had wandered up into the battle leading Duncan's horse: armouring being at a discount, Duncan had made him into his syce (Indian word for groom), and jolly good he had become. Abdul had a nasty wound in the shoulder and was weeping bitterly, howling like a child: the horse had also been hit in the shoulder, and could barely walk: Duncan shot it there and then.

The sound of shooting opened up where I had expected it; away back down the column, the flank attack was coming in. It was audibly beaten off, and I sent another message down the column warning them to look out for a repeat performance still farther down the line. Then a messenger arrived, and said: "Captain MacDonald's killed, sir."

"Nonsense," I said. "How do you know?" "Mr. Harman's back, sir. And he's badly wounded."

I went back to the fork. Jim was there, with blood streaming from a wound in his head, and his left arm held in his right hand. Alec had led the way down the track, with Jim following; then Sergeant Pester and then Pte. Fuller. They had met two light machine guns, new ones, which had opened up. Alec had fallen instantly, calling out, "Go on in, Jim!" Jim had been hit in the head and shoulder, Pester was unhurt, Fuller killed.

Jim and Pte. Pester between them had knocked out both guns, and the track was again clear. They had had a look at Alec on the way back, and he was dead.

I reckoned we had killed a good many Japs, one way and another, but it was nearly six o'clock and would soon be light; and what I dreaded more than anything else was the possibility of being caught in daylight on the track, with the little, lithe Japs, unencumbered by packs or weariness, able to crawl under the bushes at ground level and snipe the guts out of us. There was no sign of any animals; Denny seemed to have got them back all right, but what, if any luck he was having at the chaung I didn't know."

Captain Alexander Inglis MacDonald was killed in action on the 28th March 1943 at what had become Chindit Column 5's very own 'Waterloo'. There had been no time for the retreating column to recover any of their dead and so Captain MacDonald's body was left at Hintha and was never located after the war was over. Here are his CWGC details: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2516147/MACDONALD,%20ALEXANDER%20INGLIS

As you can see from his CWGC details, Alexander is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery, Burma. This memorial contains the names of over 26,000 service personnel from the Burma Campaign whose bodies were never recovered after the war and so have no known grave.

Alexander is also remembered on the Bootle War Memorial, where his name is listed along with all the other WW2 casualties from his home town. He is honoured by his old school, Merchant Taylors at Crosby, in their book of remembrance for alumni who fell in the two World Wars. Finally, Alexander is remembered in the Holy Trinity Churchyard at Amberley in Gloucestershire, alongside his mother and father and upon a special plaque on the family gravestone.

To end this poignant story, please find below several images of Captain MacDonald's many memorials and also some other images pertinent to his story. Please click on any frame to enlarge.

By March 28th the column had reached the village of Hintha which was situated in an area of thick and tight-set bamboo scrub. Any attempt to navigate around the settlement proved impossible, reluctantly, Fergusson decided to enter the village by the main track and check for the presence of any enemy patrols. He unluckily stumbled upon such a patrol and a fire-fight ensued.

Fighting platoons led by Lieutenant Stibbe and Jim Harman entered Hintha in an attempt to clear the road of Japanese. These were met in full force by the enemy and several casualties were taken on both sides. Stibbe, himself now wounded, returned to the base position of the column and reported to the Major that the situation was getting very hot and that the Japanese were making any forward movement extremely difficult.

Bernard Fergusson takes up the story:

"Alec Macdonald was beside me, and immediately said: "I'll have a look. Come on," and disappeared up the track. I had a feeling that, having failed on Peter Dorans' flank, the Japs would try and come in on the right, somewhere down the column; so I passed the word back to try and work a small flank guard into the jungle on that side if possible.

Then I went back to the T-junction, and made arrangements to attract all the attention we could, so as to give Alec a free run. I seemed to spend the whole action trotting up and down that seventy yards of track.

There came another burst of fire from the little track, a mixture of light machine gun, tommy-guns and grenades. The Commando Platoon alone in the column had tommy-guns, which was one of the reasons I had selected them for the role. Their cheerful rattle, however, meant that the little track was no longer clear. I hurried back to the fork, and there found Denny Sharp.

"This is going to be no good," I said. "Denny, take all the animals you can find, go back to the chaung and see if you can get down it. We'll go on playing about here to keep their attention fixed; I'll try and join you farther down the chaung, but if I don't then you know the next rendezvous point. Keep away from Chaungmido, as we don't want to get Brigade muddled up in this."

Back to the T-junction I went, and found on the right of the track the Burma Rifles platoon. They had taken two or three casualties, Jameson had one in the shoulder, and so did another splendid N.C.O., Nay Dun, whose name always made me think of a trout fly. I told John Fraser to take them back, but he must have sent them under Pam Heald, because he himself still remained with me at the end of the action.

Another casualty was Abdul the Damned. Somehow he had wandered up into the battle leading Duncan's horse: armouring being at a discount, Duncan had made him into his syce (Indian word for groom), and jolly good he had become. Abdul had a nasty wound in the shoulder and was weeping bitterly, howling like a child: the horse had also been hit in the shoulder, and could barely walk: Duncan shot it there and then.

The sound of shooting opened up where I had expected it; away back down the column, the flank attack was coming in. It was audibly beaten off, and I sent another message down the column warning them to look out for a repeat performance still farther down the line. Then a messenger arrived, and said: "Captain MacDonald's killed, sir."

"Nonsense," I said. "How do you know?" "Mr. Harman's back, sir. And he's badly wounded."

I went back to the fork. Jim was there, with blood streaming from a wound in his head, and his left arm held in his right hand. Alec had led the way down the track, with Jim following; then Sergeant Pester and then Pte. Fuller. They had met two light machine guns, new ones, which had opened up. Alec had fallen instantly, calling out, "Go on in, Jim!" Jim had been hit in the head and shoulder, Pester was unhurt, Fuller killed.

Jim and Pte. Pester between them had knocked out both guns, and the track was again clear. They had had a look at Alec on the way back, and he was dead.

I reckoned we had killed a good many Japs, one way and another, but it was nearly six o'clock and would soon be light; and what I dreaded more than anything else was the possibility of being caught in daylight on the track, with the little, lithe Japs, unencumbered by packs or weariness, able to crawl under the bushes at ground level and snipe the guts out of us. There was no sign of any animals; Denny seemed to have got them back all right, but what, if any luck he was having at the chaung I didn't know."

Captain Alexander Inglis MacDonald was killed in action on the 28th March 1943 at what had become Chindit Column 5's very own 'Waterloo'. There had been no time for the retreating column to recover any of their dead and so Captain MacDonald's body was left at Hintha and was never located after the war was over. Here are his CWGC details: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2516147/MACDONALD,%20ALEXANDER%20INGLIS

As you can see from his CWGC details, Alexander is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery, Burma. This memorial contains the names of over 26,000 service personnel from the Burma Campaign whose bodies were never recovered after the war and so have no known grave.

Alexander is also remembered on the Bootle War Memorial, where his name is listed along with all the other WW2 casualties from his home town. He is honoured by his old school, Merchant Taylors at Crosby, in their book of remembrance for alumni who fell in the two World Wars. Finally, Alexander is remembered in the Holy Trinity Churchyard at Amberley in Gloucestershire, alongside his mother and father and upon a special plaque on the family gravestone.

To end this poignant story, please find below several images of Captain MacDonald's many memorials and also some other images pertinent to his story. Please click on any frame to enlarge.

Update 01/11/2020.

In April this year (2020), I was pleased to receive the following email communication from Philip Bell:

Dear Steve,

Thank you for what you have done with your website, it is an amazing tribute. My uncle (my mother's brother) was Captain Alexander Inglis MacDonald, who was killed in action on the 28th March 1943. I have some letters he wrote home to my mother Alison, up until his death in Burma. I would be delighted to share the letters with you, and for you to use them as you see fit. I also have more photographs of him as a child and will share those with you too. It might be a while until I get to a scanning facility, so let’s keep in touch. Thank you again, kind regards, Phil.

I replied:

Dear Philip,

Thank you for your email contact via my website. I am extremely pleased that you came across the website and my article about your uncle. Alexander was clearly a very brave man and also well liked amongst his fellow Chindits. I would very much like to add the items you mention to his story, especially the letters and another photograph of him. As you can see the only image I have of him is from the photograph of the officers on the troopship in early 1942 and it is very grainy. Once again, thank you for your contact and I hope to hear from you again in time. Please take care during these challenging times.

Seen below is a second photograph taken aboard the troopship Oronsay in January 1942. Alexander MacDonald can be seen seated in the centre of the second row, flanked on his right side by Captain Coughlan and on his left by Major Scott.

In April this year (2020), I was pleased to receive the following email communication from Philip Bell:

Dear Steve,

Thank you for what you have done with your website, it is an amazing tribute. My uncle (my mother's brother) was Captain Alexander Inglis MacDonald, who was killed in action on the 28th March 1943. I have some letters he wrote home to my mother Alison, up until his death in Burma. I would be delighted to share the letters with you, and for you to use them as you see fit. I also have more photographs of him as a child and will share those with you too. It might be a while until I get to a scanning facility, so let’s keep in touch. Thank you again, kind regards, Phil.

I replied:

Dear Philip,

Thank you for your email contact via my website. I am extremely pleased that you came across the website and my article about your uncle. Alexander was clearly a very brave man and also well liked amongst his fellow Chindits. I would very much like to add the items you mention to his story, especially the letters and another photograph of him. As you can see the only image I have of him is from the photograph of the officers on the troopship in early 1942 and it is very grainy. Once again, thank you for your contact and I hope to hear from you again in time. Please take care during these challenging times.

Seen below is a second photograph taken aboard the troopship Oronsay in January 1942. Alexander MacDonald can be seen seated in the centre of the second row, flanked on his right side by Captain Coughlan and on his left by Major Scott.

Copyright © Steve Fogden April 2014.