The Six Sussex New Boys

The cap badge of the Royal Sussex Regiment.

The cap badge of the Royal Sussex Regiment.

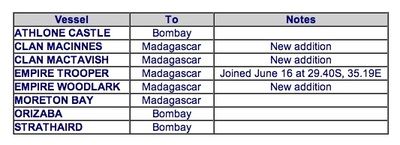

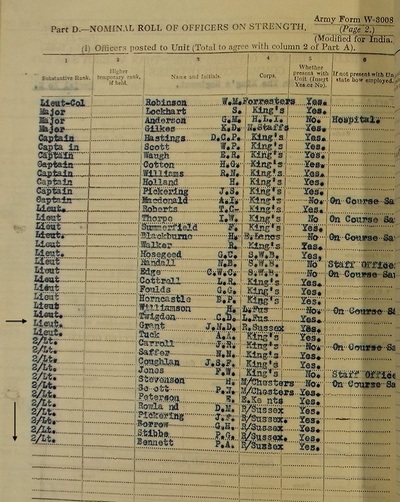

On the 4th July 1942 a small draft of six officers from the Royal Sussex Regiment arrived at the Chindit training camp in Patharia. The 13th King's War diary, kept by the battalion Adjutant, Captain David Hastings, recorded their arrival that day:

Lt. Grant and 2/Lts. Pickering, Borrow, Rowland, Bennett and Stibbe of the 9th and 10th Royal Sussex Regiment, reported here for duty on the 4th, having just arrived from England. They will probably find the climate and the hard work rather arduous to start with.

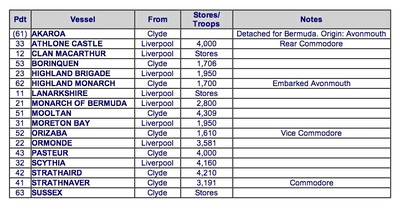

The half dozen men had begun their journey to the sub-continent from the waters of the River Mersey on the 10th May, travelling as part of the troopship convoy WS 19. One of the young 2nd Lieutenants, Philip Stibbe remembered the voyage in the pages of his book, 'Return via Rangoon':

The damp blanket of sea mist that enveloped us, the strident calls of seagulls, fog horns, and ships' sirens, all melancholy, formed a fitting background to my mood as I leant over the rails watching the water slide by the ship's side. For a few moments the mist lifted to reveal a glimpse of Scottish coastline, steep grey cliffs below and brown bracken slopes above, with patches of vivid green pasture where some very bedraggled sheep grazed.

Lucky sheep, I thought; at least you can stay in your own land with your own flock instead of being herded on to a boat with a crowd of strangers, and not only sent abroad, but sent to India, the last place on earth anyone in their senses would want to visit. The mist closed in again and the ship slid on, carrying me and my alternating sorrow and resentment out into the Atlantic.

We were a mixed convoy. There were ships from nearly all the Allied nations. Ships of every size, shape and age, but all wearing the same grey war paint. We were escorted by a cruiser and several destroyers, some British and some Lend-Lease American. Over the horizon, we were told, lurked one of our battleships and an aircraft carrier.

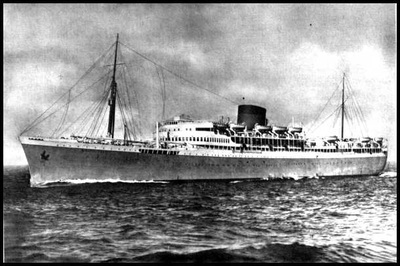

Our own ship was the Athlone Castle, one of the newest vessels of the Union Castle Line. She had been converted into a troop carrier and now carried about five times her peacetime complement of passengers. Forty-eight of our draft of officers were given bunks in a room rather less than half the size of a Nissen hut. The bunks were arranged in tiers so that we were no more able to sit up in our bunks than a corpse can sit up in its coffin. The rest of the officers slept four to a cabin.

We felt far too crowded for comfort, but we were waited on by peacetime stewards and served with peacetime food in the dining saloons. Those of us who visited the men on the lower deck, where the rations were meagre and the atmosphere stifling, realised that no officer had any cause for complaint. Down there the overcrowding was indescribable; nobody suffering from claustrophobia could have survived.

The Athlone Castle and the rest of the convoy made its way out into the Atlantic Ocean, before turning on a more southerly course eventually hugging the west coast of Africa. Almost all the convoys of the time, moving troops and equipment to the sub-continent and beyond plied the same route, with a stop-over at Freetown in Sierra Leone for supplies and then on to either Cape Town of Durban for a longer stay of 5-10 days.

Seen below are some images in relation to this story, with information about Convoy WS19 and entries from the 13th King's War diary for 1942, showing the arrival of the men from the Sussex Regiment. Please click on any image to bring to forward on the page.

For more information about the WS Convoys or Winston's Specials as they were colloquially known, please follow the link provided:

http://www.convoyweb.org.uk/ws/index.html

Lt. Grant and 2/Lts. Pickering, Borrow, Rowland, Bennett and Stibbe of the 9th and 10th Royal Sussex Regiment, reported here for duty on the 4th, having just arrived from England. They will probably find the climate and the hard work rather arduous to start with.

The half dozen men had begun their journey to the sub-continent from the waters of the River Mersey on the 10th May, travelling as part of the troopship convoy WS 19. One of the young 2nd Lieutenants, Philip Stibbe remembered the voyage in the pages of his book, 'Return via Rangoon':

The damp blanket of sea mist that enveloped us, the strident calls of seagulls, fog horns, and ships' sirens, all melancholy, formed a fitting background to my mood as I leant over the rails watching the water slide by the ship's side. For a few moments the mist lifted to reveal a glimpse of Scottish coastline, steep grey cliffs below and brown bracken slopes above, with patches of vivid green pasture where some very bedraggled sheep grazed.

Lucky sheep, I thought; at least you can stay in your own land with your own flock instead of being herded on to a boat with a crowd of strangers, and not only sent abroad, but sent to India, the last place on earth anyone in their senses would want to visit. The mist closed in again and the ship slid on, carrying me and my alternating sorrow and resentment out into the Atlantic.

We were a mixed convoy. There were ships from nearly all the Allied nations. Ships of every size, shape and age, but all wearing the same grey war paint. We were escorted by a cruiser and several destroyers, some British and some Lend-Lease American. Over the horizon, we were told, lurked one of our battleships and an aircraft carrier.

Our own ship was the Athlone Castle, one of the newest vessels of the Union Castle Line. She had been converted into a troop carrier and now carried about five times her peacetime complement of passengers. Forty-eight of our draft of officers were given bunks in a room rather less than half the size of a Nissen hut. The bunks were arranged in tiers so that we were no more able to sit up in our bunks than a corpse can sit up in its coffin. The rest of the officers slept four to a cabin.

We felt far too crowded for comfort, but we were waited on by peacetime stewards and served with peacetime food in the dining saloons. Those of us who visited the men on the lower deck, where the rations were meagre and the atmosphere stifling, realised that no officer had any cause for complaint. Down there the overcrowding was indescribable; nobody suffering from claustrophobia could have survived.

The Athlone Castle and the rest of the convoy made its way out into the Atlantic Ocean, before turning on a more southerly course eventually hugging the west coast of Africa. Almost all the convoys of the time, moving troops and equipment to the sub-continent and beyond plied the same route, with a stop-over at Freetown in Sierra Leone for supplies and then on to either Cape Town of Durban for a longer stay of 5-10 days.

Seen below are some images in relation to this story, with information about Convoy WS19 and entries from the 13th King's War diary for 1942, showing the arrival of the men from the Sussex Regiment. Please click on any image to bring to forward on the page.

For more information about the WS Convoys or Winston's Specials as they were colloquially known, please follow the link provided:

http://www.convoyweb.org.uk/ws/index.html

The Athlone Castle was to positioned towards the rear of the convoy during the North Atlantic section of the voyage. German U-Boat activity had been reported in this area, but fortunately none were to worry the vessels of Convoy WS19. The ships docked outside Freetown for four days whilst new supplies were taken aboard, no military personnel were allowed shore leave at this stopping point apart from those requiring medical attention.

The officers of the Sussex Regiment then enjoyed the hospitality of the good people of Cape Town, where, like many men before them, they were treated like royalty for the duration of their stay. Eventually, the convoy reconvened and after mustering close to the port of Durban on the 15th June, moved off once more and into the Indian Ocean. On the 27th June the Athlone Castle, the Orizaba and the Strathaird were escorted by the Cruiser, H.M.S. Devonshire to their final destination, the Indian port of Bombay.

The six officers disembarked from the Athlone Castle on the 1st July and unusually for the Army at that time, were sent immediately to the Chindit training camp at Patharia. In normal circumstances, new drafts of men were sent to large holding camps, such as Deolali, where they were kept, sometimes for several weeks before being processed and finally posted to their new unit.

The train journey from Bombay to Saugor took the best part of three days and during this time the young officers slowly became accustomed to the sights, sounds and smells of India. After alighting from the train and a short and uncomfortable journey by truck, the men finally arrived at the Chindit camp and were met by the commanding officer of the 13th King's, Colonel Robinson and his Adjutant, David Hastings.

After a short period of acclimatisation the new additions were allocated to a Chindit Column and began their jungle warfare training. George Borrow, David Rowland and Peter Bennett were posted to Column 8, Philip Stibbe to Column 5 and John Francis Pickering took up his place with Northern Group Head Quarters. NB. George Borrow was originally selected to serve with Column 5, but was seconded to Column 8 later on during training.

It is not clear where Lieutenant J.M.D. Grant, the most senior officer from the draft sent by the Sussex Regiment, was posted. He appears in the list for Officer returns (13th King's) for the last time on the 31st August 1942. At this time he was still present with the battalion at the Abchand training camp in Patharia. Some of the other officers from the King's Regiment were posted to other units across India at this time, many of these men were given administrative roles to perform, a decision made for the most part because of their age. The month of August was also one of the worst periods for men dropping out of Chindit training due to sickness and disease. It is my belief that Lieutenant Grant did not take any further part in Chindit training after August 1942 and did not serve on Operation Longcloth.

And so, what became of the five young subalterns that did cross the Chindwin River in February 1943?

212134 2nd Lieutenant Peter A. Bennett was a member of Platoon 16 in Major Walter Purcell Scott's No. 8 Column on Operation Longcloth. He served with the column from the time they crossed the Chindwin at the village of Tonhe on the 16th February, until dispersal was called and the column split up into several breakaway parties on April 14th.

Peter Bennett excelled on Operation Longcloth, especially when it came to scouting the way ahead and reconnaissance for Column 8, as they marched through the jungles of Burma in 1943. He and his platoon were used as scouts and guides, probing forward in advance of the column and then returning to guide them along the thickly covered tracks and trails, successfully avoiding enemy garrisons and patrols. Peter Bennett did some of his best work around the beginning of March when the column were sent to block a road near the Burmese town of Pinlebu.

More minor clashes with the Japanese were incurred late on 5th March, the column moved to the agreed rendezvous on the Pinlebu-Kame Road. The party halted one mile north of Kame and settled down for the night. Their position was chosen by Major Scott and units were deployed to prevent any Japanese movement toward Pinlebu from this direction.

At first light on the 6th March, the Sabotage Squad led by Lieutenant Sprague and 16 Platoon including Peter Bennett, set out towards Kame in order to secure the road block. At about 11:00 hours Sprague’s men were attacked by the Japanese from all sides, he called dispersal in an attempt to extract his men from the area. Lieutenant Bennett was crucial in leading the surrounded Chindits through the enemy positions and away from danger.

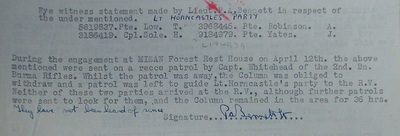

Peter became a trusted and well respected officer on Operation Longcloth, apart from his obvious talent for reconnaissance, he also had a caring nature and concern for the well-being of his men. This aspect of his character would shine through as his dispersal party struggled to exit Burma in April 1943. He also showed great responsibility and compassion after the operation was over, by giving several witness statements to the investigation bureau in relation to men lost in Burma that year.

In August 1943 he wrote to the wife of one of his Platoon Sergeants, John Thornley, who had gone missing shortly after column dispersal on the 14th April.

Dear Mrs. Thornley,

It is with the deepest regret that I write to inform you that your husband is missing. It is quite possible that he may be a prisoner of war, but we have no evidence that this is the case.

Our Commanding Officer and all ranks of the Battalion wish me to convey our most sincere sympathy in your great anxiety and to assure you that should we get any further news of your husband, we will at once let you know.

Yours sincerely P.A. Bennett on behalf of Officer Commanding 8 Column.

It is suggested that Peter went on to serve on the second Chindit operation in 1944, but I have no evidence that this is the case. I do know however, that by early 1945 he held the rank of Captain and was the Intelligence Officer for the 13th King's now stationed at the Napier Barracks in Karachi.

228394 2nd Lieutenant George Henry Borrow MC. This young subaltern served as Intelligence Officer for both Column 8 and Northern Group Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth. Born in the town of Broome in south Norfolk, the son of Edward Borrow D.S.O. who had received his own gallantry award whilst serving with the 13th Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry in WW1, it seemed almost inevitable that George would excel in his own service for King and country.

Fellow Chindit officer, Philip Stibbe described his new comrade at arms in his book, 'Return via Rangoon':

In George Borrow, another officer of my battalion of the Royal Sussex Regiment, I found a kindred spirit. An East Anglian, like his famous forebear, George was slightly built, quiet and studious, with a face like a baby owl. At first sight definitely not the kind of person one would expect to feel at home in the Army; an academic, I decided, and not a man of action. I soon discovered my mistake.

There was about George a remarkable integrity and sincerity and a wonderful gift of being able to devote himself entirely to what he was doing. This, combined with a phenomenal amount of determination, enabled him to endure far more than most of those who appeared to be better equipped for warfare. He was also one of the gentlest and least selfish men I have met. Everyone who met him came to like and admire him. Before joining the Army he had spent a year at Cambridge and, as I had spent the same period at Oxford, we had much in common.

George Borrow was suffering from jaundice in early 1943, but insisted that he could still take up his place in Chindit Column 8 and cross the Chindwin with 77 Brigade. Although weakened by his illness, he did not waver in the performance of his duties that year. He was rewarded for his efforts in 1943 with a Military Cross, recommended by the commander of Northern Group, Lieutenant-Colonel S.A. Cooke.

The recommendation read:

Throughout the operations in Burma from mid-February to mid-May 1943, Lieutenant Borrow acted as Intelligence Officer to H.Q. No. 2 Group. He insisted on accompanying the expedition [Wingate’s first Chindit operation] despite the fact he was suffering from jaundice. The continued privations and hardships of the campaign prevented him from ever recovering his health in the course of it, and in the latter stages he suffered intensely from internal disorders, general weakness and a malady which attacked his legs and made marching extremely difficult and painful.

Despite the effects of these serious inroads upon a state of health already poor, he showed throughout the campaign a superb example of doggedness and courage which aroused the admiration of every officer and man who saw him, and inspired them all to emulate his magnificent endurance.

His work as Intelligence Officer not only did not suffer from his bad state of health, but would have been remarkable for its thoroughness and efficiency in ordinary circumstances; while his behaviour under fire was exemplary. His high spirit helped immeasurably to carry the party with which he was travelling through the most arduous trials until the British lines were reached, when, after an example of steadfastness and endurance which cannot often have been surpassed, he finally collapsed.

After recovering from his tribulations on Operation Longcloth, George Borrow re-joined Chindit training in November 1943. He was then promoted to Staff Captain at Special Force Head Quarters, before Wingate made him his A.D.C. (personal assistant in the field) in time for the second Chindit expedition in March 1944.

George was constantly at Major-General Wingate's side during the early weeks of the operation, as the Chindit leader visited his brigades inside Burma. On the 24th March, they flew in to the Chindit stronghold codenamed 'Broadway', in order to congratulate Brigadier Mike Calvert on his recent successes against the Japanese. Wingate then flew on to several other Chindit positions, before heading back to his head quarters at Sylhet in India.

Tragically, the B-25 Mitchell Bomber in which he was travelling never made the return journey that day, crashing in to the jungle-covered hills of Manipur State and killing all on board. Wingate, George Borrow and the other casualties present in the plane were all buried close to the scene of the accident, near a village called Thuilon. In 1947, at the request of the United States Government all the remains from this burial were exhumed and re-interred at the Arlington National Cemetery in the State of Virginia.

To view George Borrow's CWGC details, please click on the following link:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2720064/BORROW,%20GEORGE%20HENRY

To view the original memorial plaque for the burial at Bishenpur held by the Imperial War Museum, please click on the following link:

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/30081698

Seen below are some images in relation to both Peter Bennett and George Borrow, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

The officers of the Sussex Regiment then enjoyed the hospitality of the good people of Cape Town, where, like many men before them, they were treated like royalty for the duration of their stay. Eventually, the convoy reconvened and after mustering close to the port of Durban on the 15th June, moved off once more and into the Indian Ocean. On the 27th June the Athlone Castle, the Orizaba and the Strathaird were escorted by the Cruiser, H.M.S. Devonshire to their final destination, the Indian port of Bombay.

The six officers disembarked from the Athlone Castle on the 1st July and unusually for the Army at that time, were sent immediately to the Chindit training camp at Patharia. In normal circumstances, new drafts of men were sent to large holding camps, such as Deolali, where they were kept, sometimes for several weeks before being processed and finally posted to their new unit.

The train journey from Bombay to Saugor took the best part of three days and during this time the young officers slowly became accustomed to the sights, sounds and smells of India. After alighting from the train and a short and uncomfortable journey by truck, the men finally arrived at the Chindit camp and were met by the commanding officer of the 13th King's, Colonel Robinson and his Adjutant, David Hastings.

After a short period of acclimatisation the new additions were allocated to a Chindit Column and began their jungle warfare training. George Borrow, David Rowland and Peter Bennett were posted to Column 8, Philip Stibbe to Column 5 and John Francis Pickering took up his place with Northern Group Head Quarters. NB. George Borrow was originally selected to serve with Column 5, but was seconded to Column 8 later on during training.

It is not clear where Lieutenant J.M.D. Grant, the most senior officer from the draft sent by the Sussex Regiment, was posted. He appears in the list for Officer returns (13th King's) for the last time on the 31st August 1942. At this time he was still present with the battalion at the Abchand training camp in Patharia. Some of the other officers from the King's Regiment were posted to other units across India at this time, many of these men were given administrative roles to perform, a decision made for the most part because of their age. The month of August was also one of the worst periods for men dropping out of Chindit training due to sickness and disease. It is my belief that Lieutenant Grant did not take any further part in Chindit training after August 1942 and did not serve on Operation Longcloth.

And so, what became of the five young subalterns that did cross the Chindwin River in February 1943?

212134 2nd Lieutenant Peter A. Bennett was a member of Platoon 16 in Major Walter Purcell Scott's No. 8 Column on Operation Longcloth. He served with the column from the time they crossed the Chindwin at the village of Tonhe on the 16th February, until dispersal was called and the column split up into several breakaway parties on April 14th.

Peter Bennett excelled on Operation Longcloth, especially when it came to scouting the way ahead and reconnaissance for Column 8, as they marched through the jungles of Burma in 1943. He and his platoon were used as scouts and guides, probing forward in advance of the column and then returning to guide them along the thickly covered tracks and trails, successfully avoiding enemy garrisons and patrols. Peter Bennett did some of his best work around the beginning of March when the column were sent to block a road near the Burmese town of Pinlebu.

More minor clashes with the Japanese were incurred late on 5th March, the column moved to the agreed rendezvous on the Pinlebu-Kame Road. The party halted one mile north of Kame and settled down for the night. Their position was chosen by Major Scott and units were deployed to prevent any Japanese movement toward Pinlebu from this direction.

At first light on the 6th March, the Sabotage Squad led by Lieutenant Sprague and 16 Platoon including Peter Bennett, set out towards Kame in order to secure the road block. At about 11:00 hours Sprague’s men were attacked by the Japanese from all sides, he called dispersal in an attempt to extract his men from the area. Lieutenant Bennett was crucial in leading the surrounded Chindits through the enemy positions and away from danger.

Peter became a trusted and well respected officer on Operation Longcloth, apart from his obvious talent for reconnaissance, he also had a caring nature and concern for the well-being of his men. This aspect of his character would shine through as his dispersal party struggled to exit Burma in April 1943. He also showed great responsibility and compassion after the operation was over, by giving several witness statements to the investigation bureau in relation to men lost in Burma that year.

In August 1943 he wrote to the wife of one of his Platoon Sergeants, John Thornley, who had gone missing shortly after column dispersal on the 14th April.

Dear Mrs. Thornley,

It is with the deepest regret that I write to inform you that your husband is missing. It is quite possible that he may be a prisoner of war, but we have no evidence that this is the case.

Our Commanding Officer and all ranks of the Battalion wish me to convey our most sincere sympathy in your great anxiety and to assure you that should we get any further news of your husband, we will at once let you know.

Yours sincerely P.A. Bennett on behalf of Officer Commanding 8 Column.

It is suggested that Peter went on to serve on the second Chindit operation in 1944, but I have no evidence that this is the case. I do know however, that by early 1945 he held the rank of Captain and was the Intelligence Officer for the 13th King's now stationed at the Napier Barracks in Karachi.

228394 2nd Lieutenant George Henry Borrow MC. This young subaltern served as Intelligence Officer for both Column 8 and Northern Group Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth. Born in the town of Broome in south Norfolk, the son of Edward Borrow D.S.O. who had received his own gallantry award whilst serving with the 13th Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry in WW1, it seemed almost inevitable that George would excel in his own service for King and country.

Fellow Chindit officer, Philip Stibbe described his new comrade at arms in his book, 'Return via Rangoon':

In George Borrow, another officer of my battalion of the Royal Sussex Regiment, I found a kindred spirit. An East Anglian, like his famous forebear, George was slightly built, quiet and studious, with a face like a baby owl. At first sight definitely not the kind of person one would expect to feel at home in the Army; an academic, I decided, and not a man of action. I soon discovered my mistake.

There was about George a remarkable integrity and sincerity and a wonderful gift of being able to devote himself entirely to what he was doing. This, combined with a phenomenal amount of determination, enabled him to endure far more than most of those who appeared to be better equipped for warfare. He was also one of the gentlest and least selfish men I have met. Everyone who met him came to like and admire him. Before joining the Army he had spent a year at Cambridge and, as I had spent the same period at Oxford, we had much in common.

George Borrow was suffering from jaundice in early 1943, but insisted that he could still take up his place in Chindit Column 8 and cross the Chindwin with 77 Brigade. Although weakened by his illness, he did not waver in the performance of his duties that year. He was rewarded for his efforts in 1943 with a Military Cross, recommended by the commander of Northern Group, Lieutenant-Colonel S.A. Cooke.

The recommendation read:

Throughout the operations in Burma from mid-February to mid-May 1943, Lieutenant Borrow acted as Intelligence Officer to H.Q. No. 2 Group. He insisted on accompanying the expedition [Wingate’s first Chindit operation] despite the fact he was suffering from jaundice. The continued privations and hardships of the campaign prevented him from ever recovering his health in the course of it, and in the latter stages he suffered intensely from internal disorders, general weakness and a malady which attacked his legs and made marching extremely difficult and painful.

Despite the effects of these serious inroads upon a state of health already poor, he showed throughout the campaign a superb example of doggedness and courage which aroused the admiration of every officer and man who saw him, and inspired them all to emulate his magnificent endurance.

His work as Intelligence Officer not only did not suffer from his bad state of health, but would have been remarkable for its thoroughness and efficiency in ordinary circumstances; while his behaviour under fire was exemplary. His high spirit helped immeasurably to carry the party with which he was travelling through the most arduous trials until the British lines were reached, when, after an example of steadfastness and endurance which cannot often have been surpassed, he finally collapsed.

After recovering from his tribulations on Operation Longcloth, George Borrow re-joined Chindit training in November 1943. He was then promoted to Staff Captain at Special Force Head Quarters, before Wingate made him his A.D.C. (personal assistant in the field) in time for the second Chindit expedition in March 1944.

George was constantly at Major-General Wingate's side during the early weeks of the operation, as the Chindit leader visited his brigades inside Burma. On the 24th March, they flew in to the Chindit stronghold codenamed 'Broadway', in order to congratulate Brigadier Mike Calvert on his recent successes against the Japanese. Wingate then flew on to several other Chindit positions, before heading back to his head quarters at Sylhet in India.

Tragically, the B-25 Mitchell Bomber in which he was travelling never made the return journey that day, crashing in to the jungle-covered hills of Manipur State and killing all on board. Wingate, George Borrow and the other casualties present in the plane were all buried close to the scene of the accident, near a village called Thuilon. In 1947, at the request of the United States Government all the remains from this burial were exhumed and re-interred at the Arlington National Cemetery in the State of Virginia.

To view George Borrow's CWGC details, please click on the following link:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2720064/BORROW,%20GEORGE%20HENRY

To view the original memorial plaque for the burial at Bishenpur held by the Imperial War Museum, please click on the following link:

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/30081698

Seen below are some images in relation to both Peter Bennett and George Borrow, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

207772 2nd Lieutenant John Francis Pickering was the son of John William and Catherine Pickering, of Paddington, London. He had been brought up in the London Borough of Westminister and lived with his parents at 87 Nutbourne Street in Queens Park for most of the years leading up to the war. With the coming of war, John decided to enlist and was posted originally to the London Irish Rifles and then into the Royal Sussex Regiment.

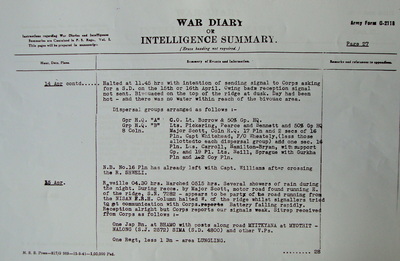

On Operation Longcloth, John Pickering worked in Northern Group Head Quarters, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel S.A. Cooke. This unit shadowed Brigadier Wingate's own Brigade HQ for the majority of the time inside Burma, but they also worked in close harmony with Column's 7 and 8.

Amongst other duties within Northern Group HQ, Lieutenant Pickering had been given the task of preparing the supply drop locations in readiness for forthcoming air supply. This included choosing a suitable location, creating a sensible pathway for the supplies to land on and being responsible for illuminating the area in order for the aircraft to identify the supply drop zone or SD. In early April his HQ and Column 8 received one such supply drop from which the men not only restocked on much needed rations, but also took on new boots, uniforms, ammunition and most vitally of all, a new battery for the wireless set.

On the 14th April 1943, John was placed into the same dispersal group as Peter Bennett and between them they led half the men of Northern Group Head Quarters back to India. On that day Lieutenants Pickering, Pearce and Bennett and their dispersal group headed for Watto, a small village on the banks of the Irrawaddy River. I have always thought that John must have gained a degree of comfort from being paired with his former Royal Sussex comrade, on the return journey to India.

After many weeks of arduous marching and the crossing of several formidable Burmese rivers, the vast majority of John Pickering's dispersal party reached the Assam Borders. The exhausted Chindits from his party were immediately sent to hospital and treated for their various ailments.

Sadly, John Francis Pickering died on the 15th June 1943 at the Indian General Hospital in Kohima, his cause of death; Acute Suppurative Parotitis, Malaria, B.T. (R) and Inanition.

Inanition is the exhausted condition that results from the lack of regular food and water, which can be no great surprise considering the privations most of the Chindits experienced that year. Suppurative parotitis is an acute infection of the parotid gland which can be caused by a variety of bacteria and viruses. Acute bacterial suppurative parotitis is most commonly caused by severe debilitation, dehydration, and poor oral hygiene. The condition can be further aggravated by the loss of saliva production in the mouth, a symptom commonly experienced by the stricken Chindits as they marched long distances in great heat and with little water.

One man who was with John during the long march back to India in 1943, was Lance Corporal George Bell. He remembered those final few days, as the group closed in on the Assam Borders:

We marched sometimes 20 miles in a day, re-crossing the railway and two more minor rivers. We slogged on for a few more days, by which time our food supplies had completely run out. I brewed up with a tea bag that must have been used at least twenty times before. Eventually we reached the Chindwin River, some Burmese boatmen ferried us across near Tamanthi which was occupied by the enemy at that time. We marched quickly westward and came to an Assam Rifles outpost. Here we shaved off our beards which showed us how thin we had become, losing two or three stones in weight. After a few days rest in the camp we set off again, this time knowing we were safe.

Remarkably this seemed to make matters worse for some of the men. Our incentive to keep going was no longer there, physiologically we were in a poorer state and many of the lads health began to go down hill. Eventually we hit the road and were transported to the hospital at Kohima. It was here that Lieutenant Pickering and Private Sullivan sadly died, after all we had been through it was heartbreaking.

Lieutenant John Francis Pickering was buried at Kohima War Cemetery. To view his CWGC details, please click on the following link:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2601938/PICKERING,%20JOHN%20FRANCIS

To read more about John Francis Pickering, please click on the following link and scroll down to his story:

Roll Call P-T

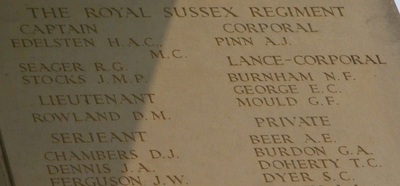

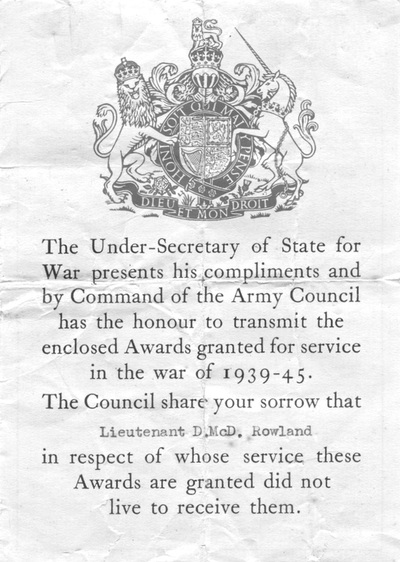

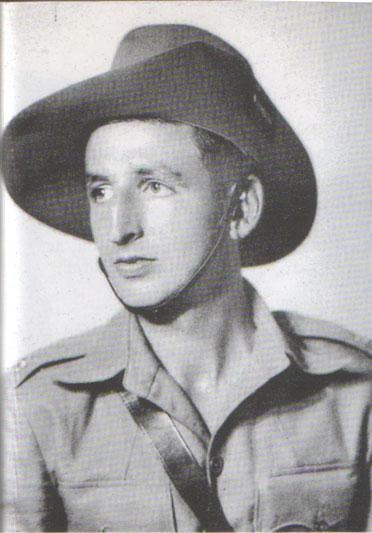

207775 2nd Lieutenant David MacDonald Rowland was the son of Frank and Flora Rowland from Horsham in Sussex. David was posted to Chindit Column 8 and served with this unit throughout Operation Longcloth. The young Lieutenant always seemed to be at the forefront of Column activities, volunteering for difficult and often dangerous duties. In early March 1943, he became the go-between officer for Column 8, taking messages and fresh orders to other Chindit columns in the area around Pinlebu.

After the fiercely contested supply drop at the village of Baw on the 24th March, David Rowland was asked by Major Scott to remain in the locality and await the arrival of Column 5. The drop zone had been compromised by a Japanese patrol and a long and drawn out action had been fought on the east side of the village. Column 5 were several miles away at that time and would have lost their chance of much needed food rations and supplies, were it not for the bravery of Lieutenant Rowland and his platoon. Lt. Rowland was also asked by Major Scott to inform Bernard Fergusson that the order had been given by General Command for the Chindits to now return to India.

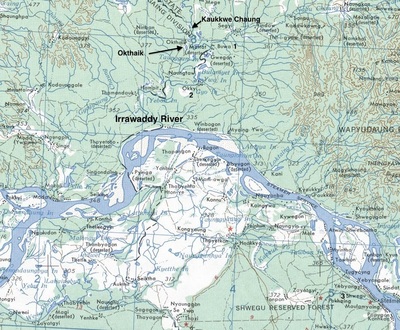

By the end of April 1943, Column 8 had moved across the Irrawaddy River and were heading roughly northwest towards the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway. They reached the village of Okthaik on the 30th April and avoiding local trails, began to cross the narrow, but fast flowing Kaukkwe Chaung. Major Scott sent a section across to form the usual protective bridgehead, then began to ferry over the non-swimmers and equipment.

Suddenly from amongst the teak trees, a Japanese patrol opened fire upon the Chindits on the nearside bank. Many of the officers and NCO's of the column had remained on this bank as rearguard, they returned fire against the Japanese with all that they had. One man present on that day was Sgt. Tony Aubrey, he remembered:

Our rifles were leaning, with our packs, against adjacent and convenient trees. We were trying as best we could to make believe to ourselves that such a thing as marching on again that afternoon simply didn't exist. Down the bed of the stream, from north to south, a trickle of water flowed gently and peacefully.

The jungle silence was broken only by the occasional ring of a utensil against a mess-tin, and the subdued murmur of men's voices. Suddenly, from the bed of the stream fifty yards south of us, where it took a bend, came a withering burst of machine-gun fire. Small arms spoke from the woods to south and west of us, and mortar bombs started to drop into our section areas.

We had made our one and only error, and it looked as though we must pay dearly for it. The continual reports of "no sign of enemy" had bred over-confidence, we had allowed our vigilance to relax that fatal night, and now we were for it. A wild scramble took place.

Men whose rifles were immediately to hand, grabbed them, took cover, and made a fighting withdrawal to north or east, whichever seemed easier. Those whose weapons were a little farther away, leaped for them. Some reached them, some didn't. Others simply had no chance at all of getting near either their rifles or their packs. It would have been certain death to attempt it.

Mr. Rowlands, lying in cover on the edge of the stream, and doing great execution on the advancing Japs with his rifle, was shot through the head. Major Scott succeeded in drawing off a party about forty strong to the east. The remainder of the officers and senior N.C.O.s rallied to them as many men as they could. And all the column withdrew as it could, crawling from cover to cover, now managing to get in a couple of shots, now unable to see any target to fire at, but always hearing the chatter of the Jap machine guns, and the bullets passing above their heads.

Many brave men perished at the Kaukkwe Chaung that day protecting their comrades as they struggled to cross the river. Some other reports, including the Column 8 War diary, suggest that Lieutenant Rowland was killed from a gunshot to the chest and not the head as Sgt. Aubrey states.

To view David Rowland's CWGC details, please click on the following link:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2523806/ROWLAND,%20DAVID%20MACDONALD

Seen below are some images in relation to the men mentioned in this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

On Operation Longcloth, John Pickering worked in Northern Group Head Quarters, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel S.A. Cooke. This unit shadowed Brigadier Wingate's own Brigade HQ for the majority of the time inside Burma, but they also worked in close harmony with Column's 7 and 8.

Amongst other duties within Northern Group HQ, Lieutenant Pickering had been given the task of preparing the supply drop locations in readiness for forthcoming air supply. This included choosing a suitable location, creating a sensible pathway for the supplies to land on and being responsible for illuminating the area in order for the aircraft to identify the supply drop zone or SD. In early April his HQ and Column 8 received one such supply drop from which the men not only restocked on much needed rations, but also took on new boots, uniforms, ammunition and most vitally of all, a new battery for the wireless set.

On the 14th April 1943, John was placed into the same dispersal group as Peter Bennett and between them they led half the men of Northern Group Head Quarters back to India. On that day Lieutenants Pickering, Pearce and Bennett and their dispersal group headed for Watto, a small village on the banks of the Irrawaddy River. I have always thought that John must have gained a degree of comfort from being paired with his former Royal Sussex comrade, on the return journey to India.

After many weeks of arduous marching and the crossing of several formidable Burmese rivers, the vast majority of John Pickering's dispersal party reached the Assam Borders. The exhausted Chindits from his party were immediately sent to hospital and treated for their various ailments.

Sadly, John Francis Pickering died on the 15th June 1943 at the Indian General Hospital in Kohima, his cause of death; Acute Suppurative Parotitis, Malaria, B.T. (R) and Inanition.

Inanition is the exhausted condition that results from the lack of regular food and water, which can be no great surprise considering the privations most of the Chindits experienced that year. Suppurative parotitis is an acute infection of the parotid gland which can be caused by a variety of bacteria and viruses. Acute bacterial suppurative parotitis is most commonly caused by severe debilitation, dehydration, and poor oral hygiene. The condition can be further aggravated by the loss of saliva production in the mouth, a symptom commonly experienced by the stricken Chindits as they marched long distances in great heat and with little water.

One man who was with John during the long march back to India in 1943, was Lance Corporal George Bell. He remembered those final few days, as the group closed in on the Assam Borders:

We marched sometimes 20 miles in a day, re-crossing the railway and two more minor rivers. We slogged on for a few more days, by which time our food supplies had completely run out. I brewed up with a tea bag that must have been used at least twenty times before. Eventually we reached the Chindwin River, some Burmese boatmen ferried us across near Tamanthi which was occupied by the enemy at that time. We marched quickly westward and came to an Assam Rifles outpost. Here we shaved off our beards which showed us how thin we had become, losing two or three stones in weight. After a few days rest in the camp we set off again, this time knowing we were safe.

Remarkably this seemed to make matters worse for some of the men. Our incentive to keep going was no longer there, physiologically we were in a poorer state and many of the lads health began to go down hill. Eventually we hit the road and were transported to the hospital at Kohima. It was here that Lieutenant Pickering and Private Sullivan sadly died, after all we had been through it was heartbreaking.

Lieutenant John Francis Pickering was buried at Kohima War Cemetery. To view his CWGC details, please click on the following link:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2601938/PICKERING,%20JOHN%20FRANCIS

To read more about John Francis Pickering, please click on the following link and scroll down to his story:

Roll Call P-T

207775 2nd Lieutenant David MacDonald Rowland was the son of Frank and Flora Rowland from Horsham in Sussex. David was posted to Chindit Column 8 and served with this unit throughout Operation Longcloth. The young Lieutenant always seemed to be at the forefront of Column activities, volunteering for difficult and often dangerous duties. In early March 1943, he became the go-between officer for Column 8, taking messages and fresh orders to other Chindit columns in the area around Pinlebu.

After the fiercely contested supply drop at the village of Baw on the 24th March, David Rowland was asked by Major Scott to remain in the locality and await the arrival of Column 5. The drop zone had been compromised by a Japanese patrol and a long and drawn out action had been fought on the east side of the village. Column 5 were several miles away at that time and would have lost their chance of much needed food rations and supplies, were it not for the bravery of Lieutenant Rowland and his platoon. Lt. Rowland was also asked by Major Scott to inform Bernard Fergusson that the order had been given by General Command for the Chindits to now return to India.

By the end of April 1943, Column 8 had moved across the Irrawaddy River and were heading roughly northwest towards the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway. They reached the village of Okthaik on the 30th April and avoiding local trails, began to cross the narrow, but fast flowing Kaukkwe Chaung. Major Scott sent a section across to form the usual protective bridgehead, then began to ferry over the non-swimmers and equipment.

Suddenly from amongst the teak trees, a Japanese patrol opened fire upon the Chindits on the nearside bank. Many of the officers and NCO's of the column had remained on this bank as rearguard, they returned fire against the Japanese with all that they had. One man present on that day was Sgt. Tony Aubrey, he remembered:

Our rifles were leaning, with our packs, against adjacent and convenient trees. We were trying as best we could to make believe to ourselves that such a thing as marching on again that afternoon simply didn't exist. Down the bed of the stream, from north to south, a trickle of water flowed gently and peacefully.

The jungle silence was broken only by the occasional ring of a utensil against a mess-tin, and the subdued murmur of men's voices. Suddenly, from the bed of the stream fifty yards south of us, where it took a bend, came a withering burst of machine-gun fire. Small arms spoke from the woods to south and west of us, and mortar bombs started to drop into our section areas.

We had made our one and only error, and it looked as though we must pay dearly for it. The continual reports of "no sign of enemy" had bred over-confidence, we had allowed our vigilance to relax that fatal night, and now we were for it. A wild scramble took place.

Men whose rifles were immediately to hand, grabbed them, took cover, and made a fighting withdrawal to north or east, whichever seemed easier. Those whose weapons were a little farther away, leaped for them. Some reached them, some didn't. Others simply had no chance at all of getting near either their rifles or their packs. It would have been certain death to attempt it.

Mr. Rowlands, lying in cover on the edge of the stream, and doing great execution on the advancing Japs with his rifle, was shot through the head. Major Scott succeeded in drawing off a party about forty strong to the east. The remainder of the officers and senior N.C.O.s rallied to them as many men as they could. And all the column withdrew as it could, crawling from cover to cover, now managing to get in a couple of shots, now unable to see any target to fire at, but always hearing the chatter of the Jap machine guns, and the bullets passing above their heads.

Many brave men perished at the Kaukkwe Chaung that day protecting their comrades as they struggled to cross the river. Some other reports, including the Column 8 War diary, suggest that Lieutenant Rowland was killed from a gunshot to the chest and not the head as Sgt. Aubrey states.

To view David Rowland's CWGC details, please click on the following link:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2523806/ROWLAND,%20DAVID%20MACDONALD

Seen below are some images in relation to the men mentioned in this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

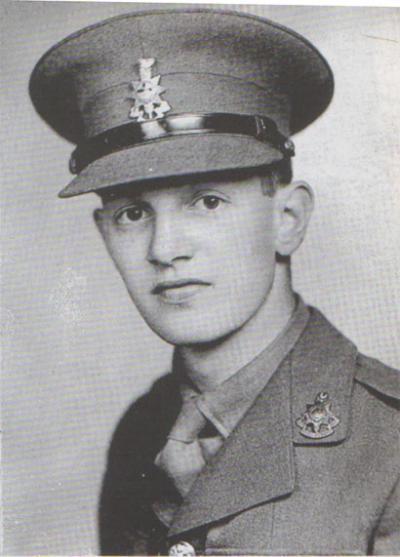

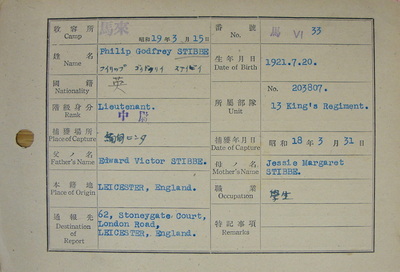

203507 2nd Lieutenant Philip Godfrey Stibbe was born in Leicester in 1921 and had attended Merton College, Oxford, just before WW2 broke out. He enlisted into the Army straight from college in the summer of 1940. Philip was placed into Chindit Column 5, under the original command of Captain Ted Waugh and his training commenced. By his own admission he had a fairly smooth time whilst training, but did rely heavily on his superb team of NCO's.

From his book about his time in Burma, 'Return via Rangoon', it is clear that he was a popular officer who took time out to learn the background and foibles of his men. He often listened to them chatting whilst in bivouac, in an attempt to understand how they were feeling and what made them tick as a unit of soldiers.

Philip Stibbe was wounded during the action in the village of Hintha in late March 1943, it was here that Column 5 lost it's cohesion as a working unit and fragmented into smaller dispersal groups. A young Burma Rifleman, Maung Tun offered to remain with the badly wounded Lieutenant near the village (Hintha), in the hope that with some rest the officer might be able to recover and continue the march out of Burma. Sadly, this was not to be the case and Maung Tun was captured by the Japanese whilst out searching for food and water. Refusing to divulge Stibbe's whereabouts, cost this brave soldier his life and is the reason why Philip Stibbe dedicates his book to the memory of the Rifleman.

Stibbe himself is captured on the 31st of March and begins his long period as a prisoner of war. He makes the journey down to Rangoon Jail, having passed through all the usual POW camps on the way, places like Bhamo Jail and the Chindit concentration camp at Maymyo. Given the POW number 33 in Rangoon, he settles down to prison life in Block 3 after enduring a short period in solitary confinement.

In April 1945 he is selected as one of the 'fit' prisoners from within the jail and is marched out by the now retreating Japanese toward the Siam borders. A few days later, realising that remaining with these slow moving prisoners is in fact compromising their own escape, the Japanese abandon the POW's close to the Burmese town of Pegu. It is at this point that Philip Stibbe's time as a prisoner of war comes to an end.

After the war Philip Stibbe pursued a career in teaching, culminating in his Headmastership at Norwich Independent School in 1975. Philip sadly died in 1997, whilst still residing in the city of Norwich.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, January 2015.

From his book about his time in Burma, 'Return via Rangoon', it is clear that he was a popular officer who took time out to learn the background and foibles of his men. He often listened to them chatting whilst in bivouac, in an attempt to understand how they were feeling and what made them tick as a unit of soldiers.

Philip Stibbe was wounded during the action in the village of Hintha in late March 1943, it was here that Column 5 lost it's cohesion as a working unit and fragmented into smaller dispersal groups. A young Burma Rifleman, Maung Tun offered to remain with the badly wounded Lieutenant near the village (Hintha), in the hope that with some rest the officer might be able to recover and continue the march out of Burma. Sadly, this was not to be the case and Maung Tun was captured by the Japanese whilst out searching for food and water. Refusing to divulge Stibbe's whereabouts, cost this brave soldier his life and is the reason why Philip Stibbe dedicates his book to the memory of the Rifleman.

Stibbe himself is captured on the 31st of March and begins his long period as a prisoner of war. He makes the journey down to Rangoon Jail, having passed through all the usual POW camps on the way, places like Bhamo Jail and the Chindit concentration camp at Maymyo. Given the POW number 33 in Rangoon, he settles down to prison life in Block 3 after enduring a short period in solitary confinement.

In April 1945 he is selected as one of the 'fit' prisoners from within the jail and is marched out by the now retreating Japanese toward the Siam borders. A few days later, realising that remaining with these slow moving prisoners is in fact compromising their own escape, the Japanese abandon the POW's close to the Burmese town of Pegu. It is at this point that Philip Stibbe's time as a prisoner of war comes to an end.

After the war Philip Stibbe pursued a career in teaching, culminating in his Headmastership at Norwich Independent School in 1975. Philip sadly died in 1997, whilst still residing in the city of Norwich.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, January 2015.