The Longcloth Roll Call

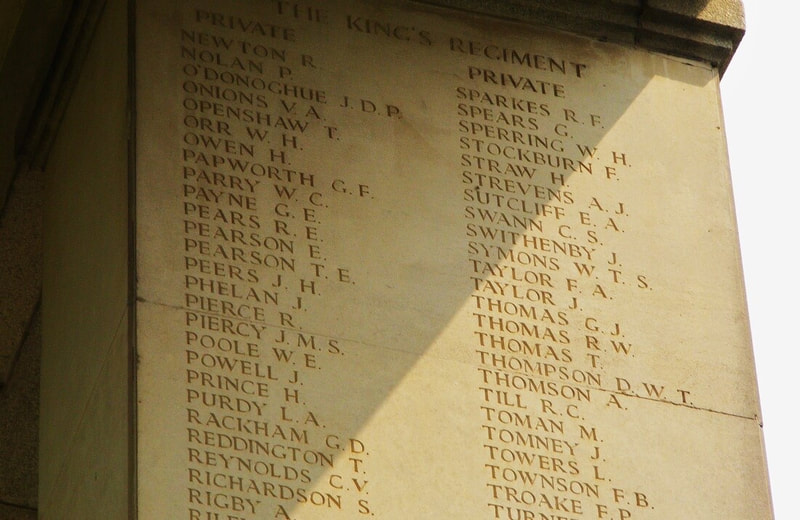

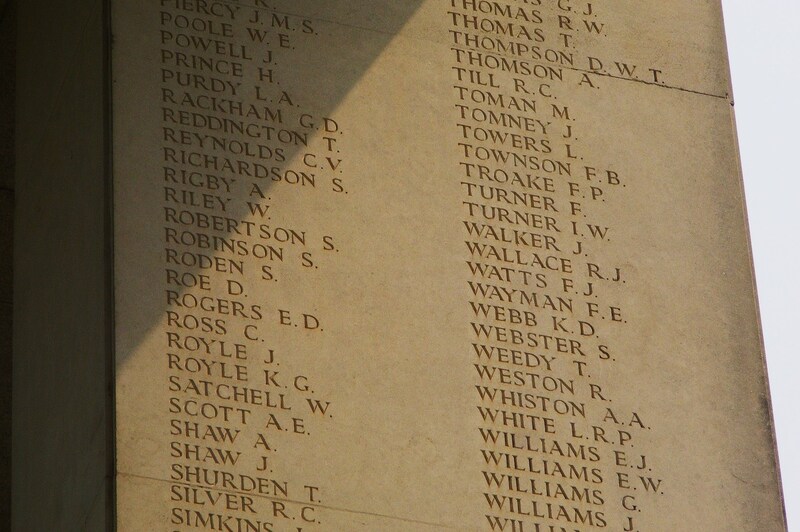

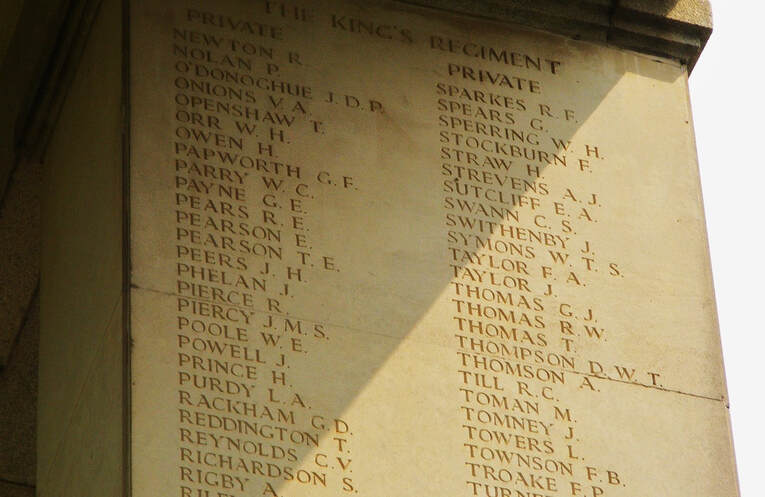

Surname P-T

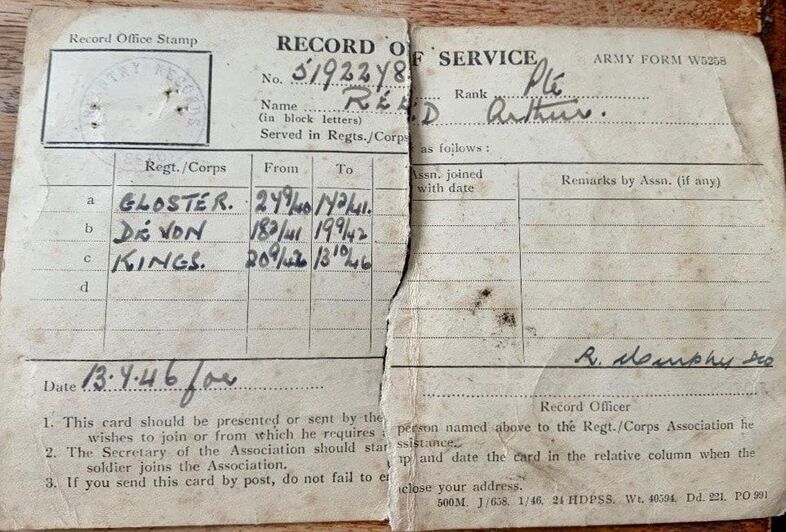

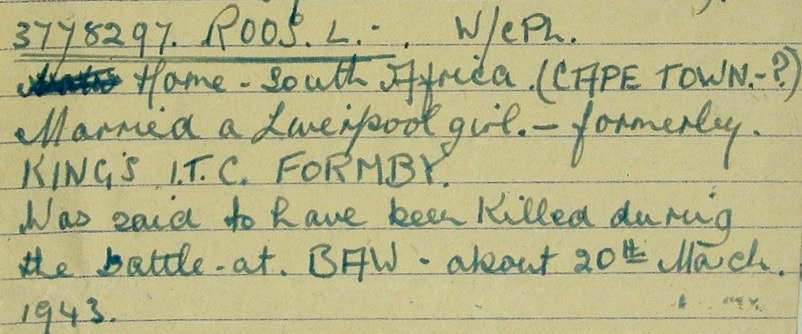

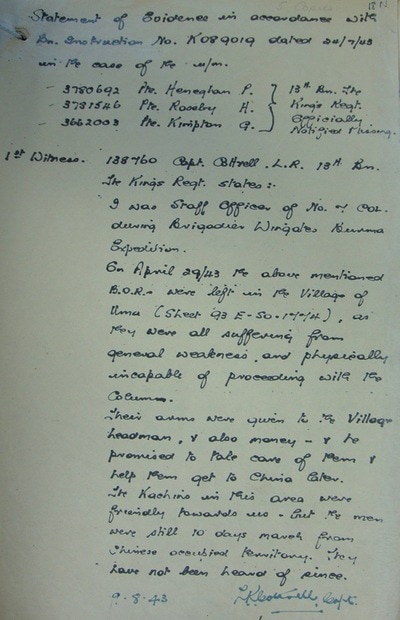

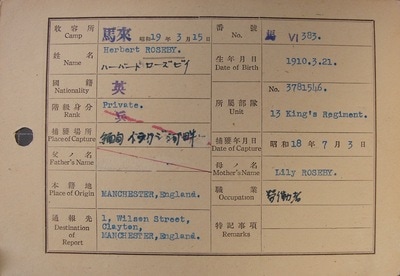

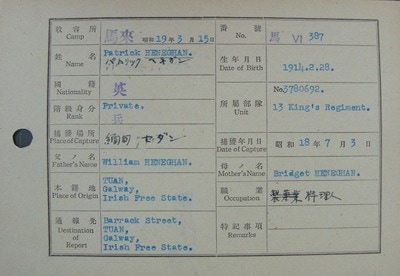

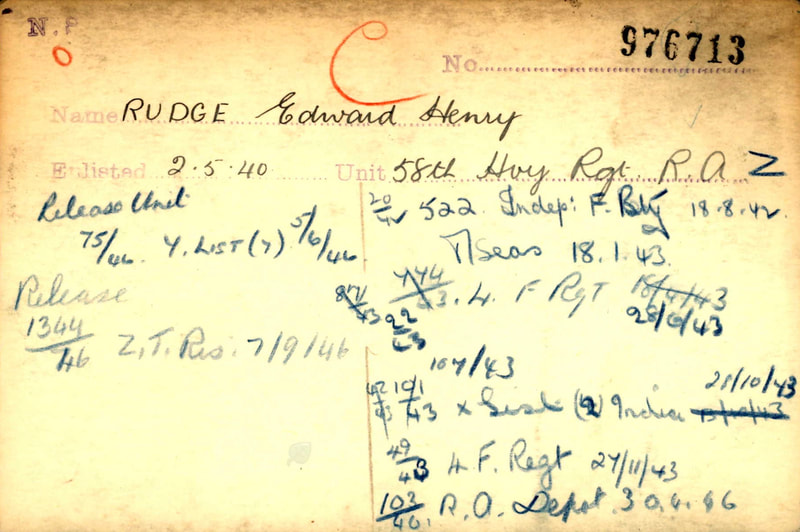

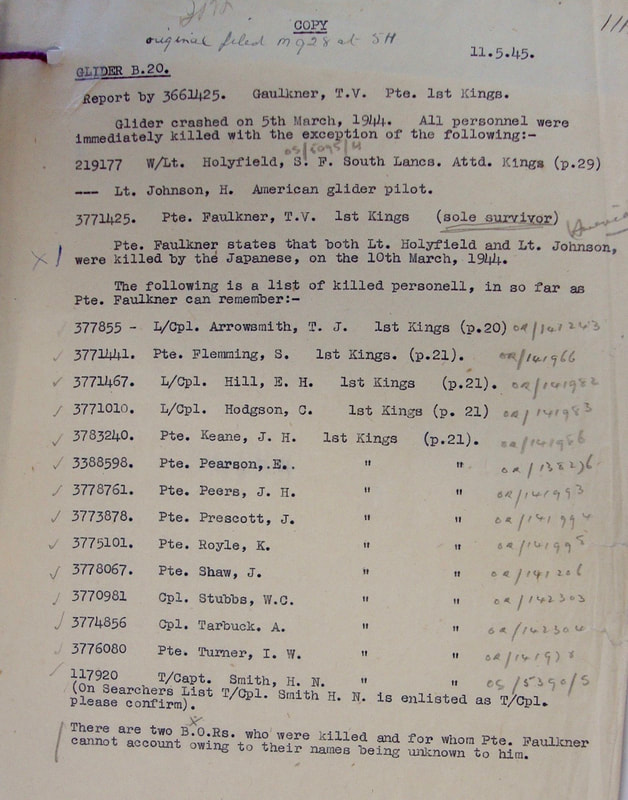

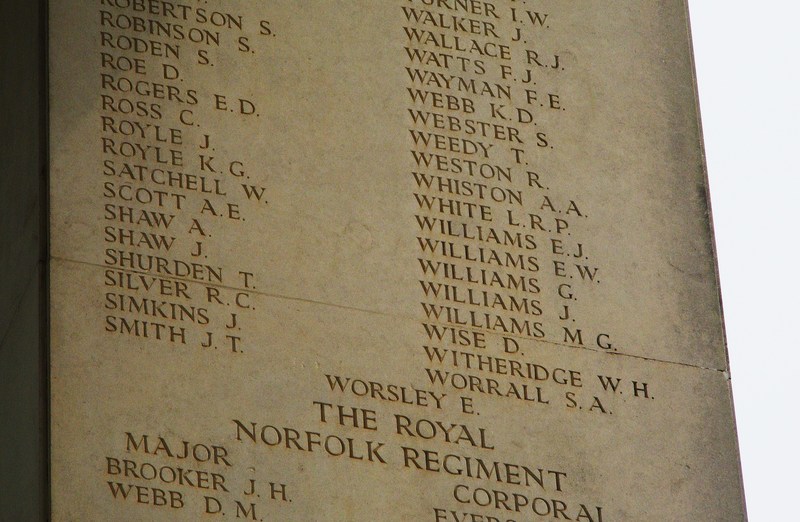

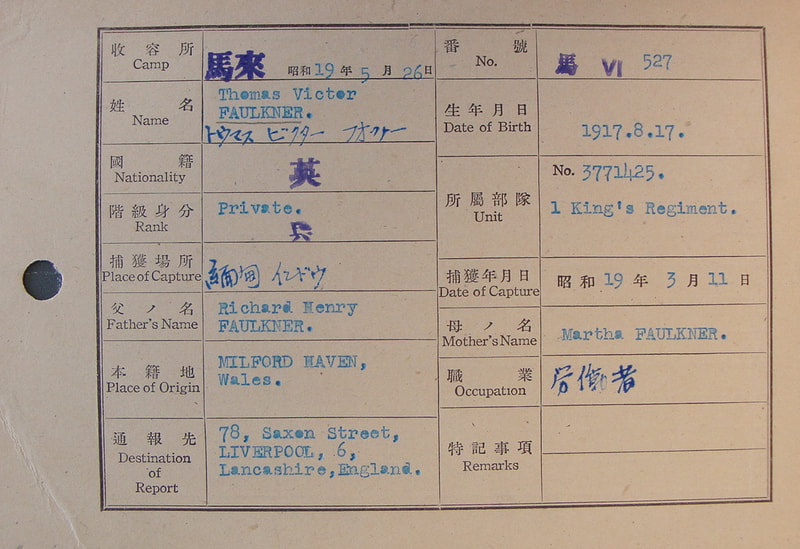

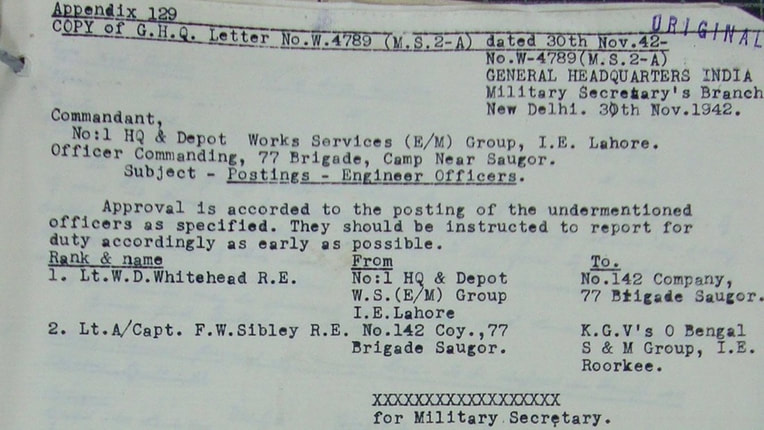

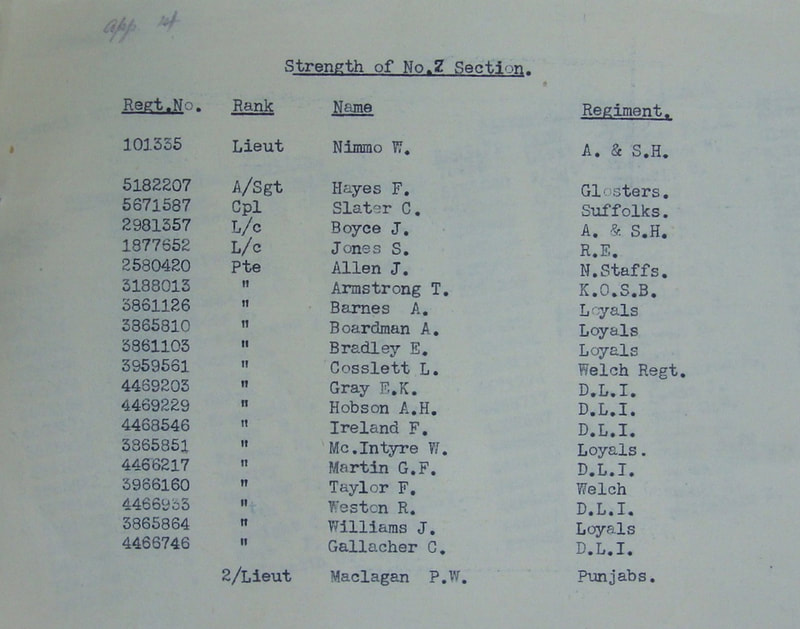

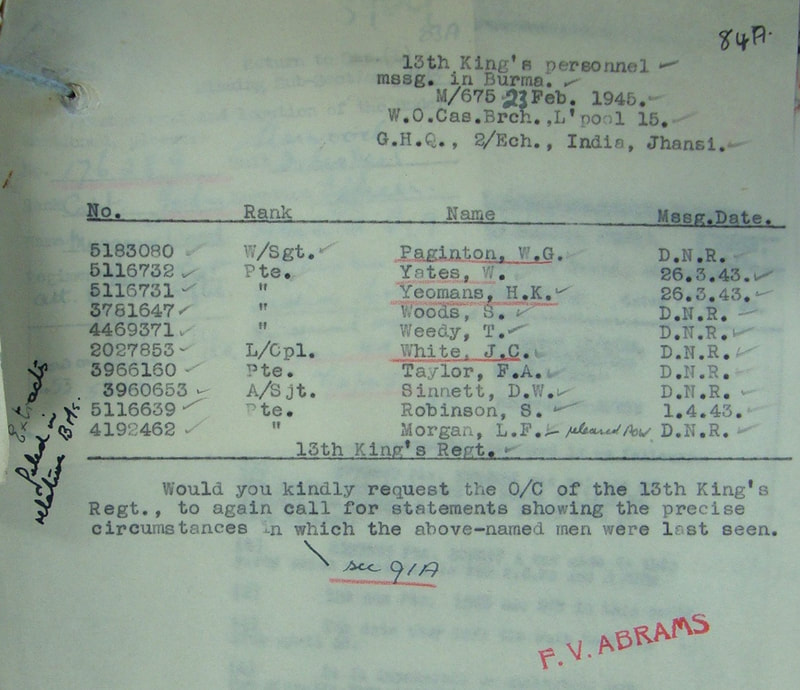

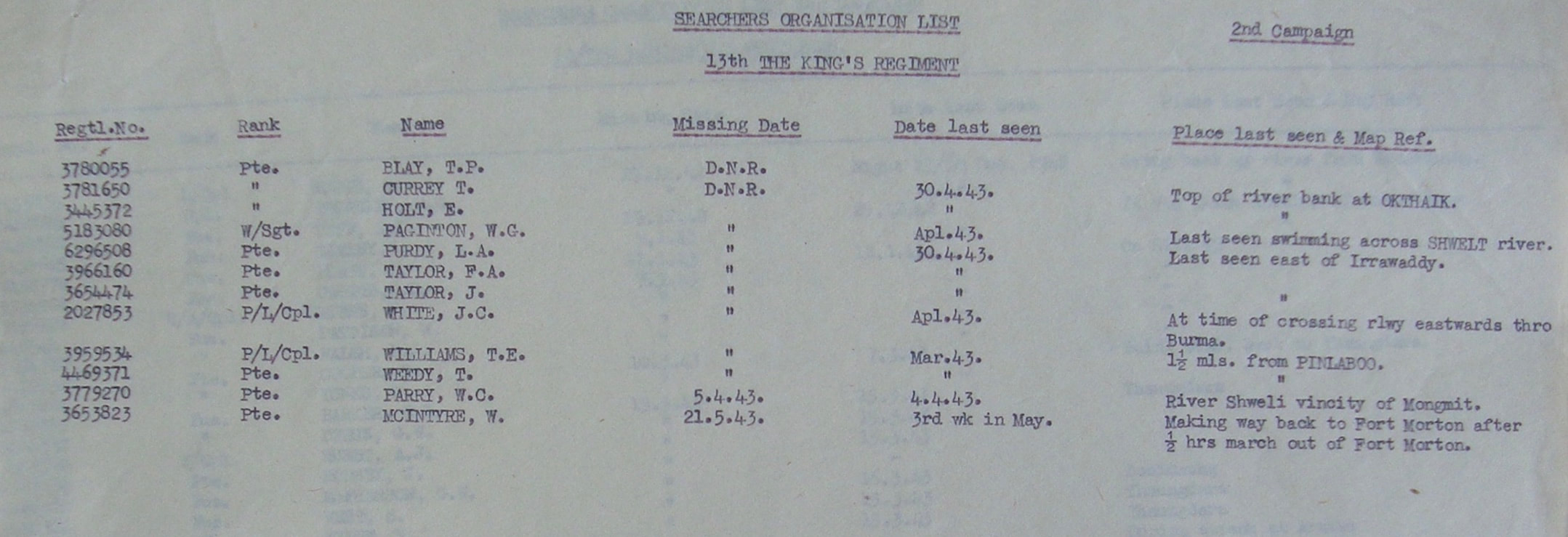

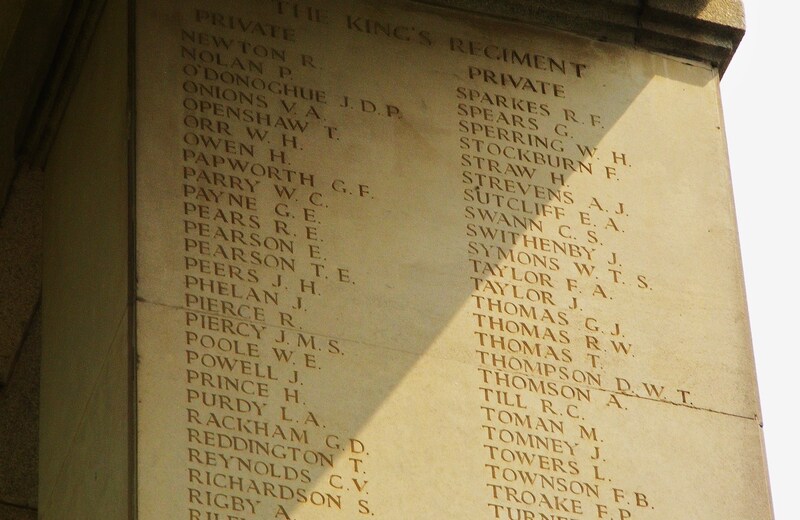

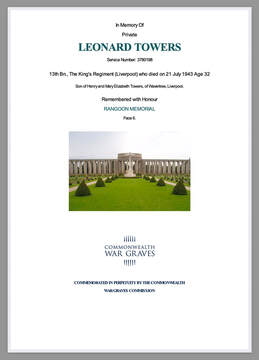

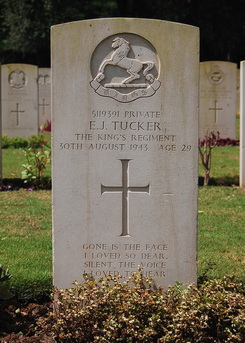

This section is an alphabetical roll of the men from Operation Longcloth. It takes its inspiration from other such formats available on the Internet, websites such as Special Forces Roll of Honour and of course the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC). The information shown comes from various different documents related to the first Chindit Operation in 1943. Apart from more obvious data, such as the serviceman's rank, number and regimental unit, other detail has been taken from associated war diaries, missing in action files and casualty witness statements. The vast majority of this type of information has been located at the National Archives and the relevant file references can be found in the section Sources and Knowledge on this website.

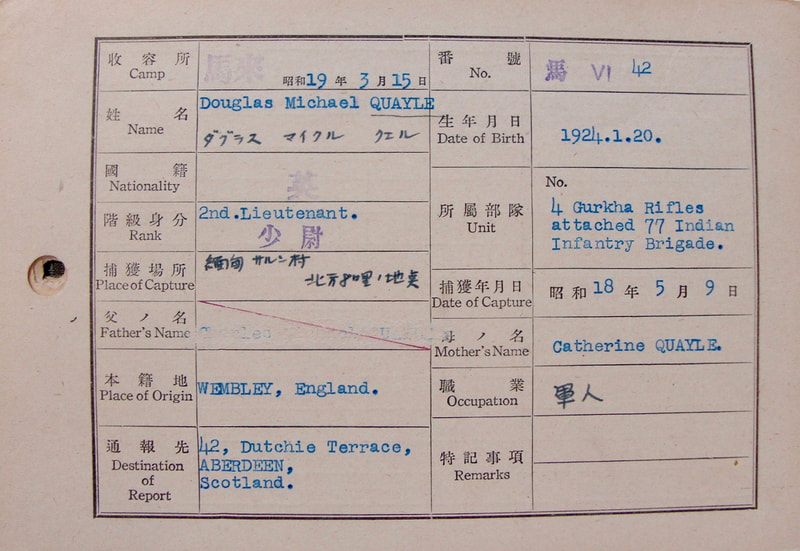

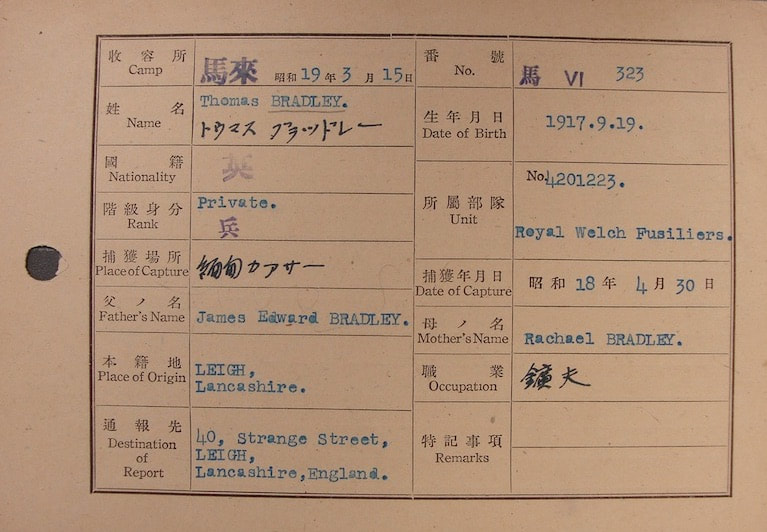

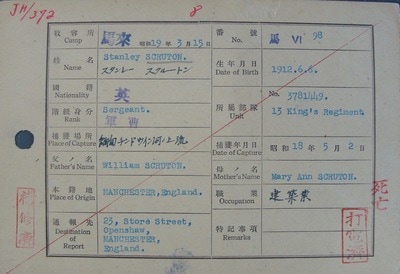

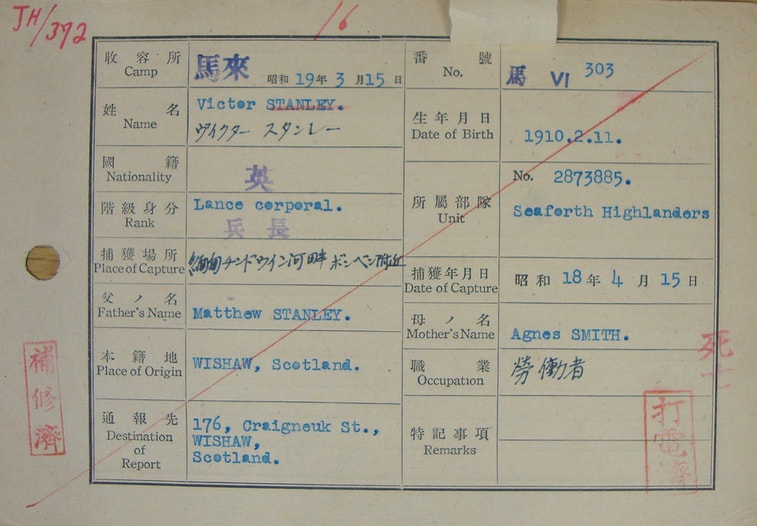

Sometimes, if the man in question became a prisoner of war more detail can be displayed showing his time whilst in Japanese hands. Other avenues for additional information are: books, personal diaries, veteran audio accounts and subsequent family input via letter, email and phone call.

The idea behind this page, is to include as many Longcloth participants as possible, even if there is only a small amount of information about their contribution to hand. Please click on any of the images to hopefully bring them forward on the page.

All information contained on this page is Copyright © Steve Fogden April 2014.

Sometimes, if the man in question became a prisoner of war more detail can be displayed showing his time whilst in Japanese hands. Other avenues for additional information are: books, personal diaries, veteran audio accounts and subsequent family input via letter, email and phone call.

The idea behind this page, is to include as many Longcloth participants as possible, even if there is only a small amount of information about their contribution to hand. Please click on any of the images to hopefully bring them forward on the page.

All information contained on this page is Copyright © Steve Fogden April 2014.

The Ford Motor Car Plant, Dagenham.

The Ford Motor Car Plant, Dagenham.

PALMER, EDWARD JOSEPH

Rank: Private

Service No: 3780709

Age: 30

Regiment/Service: 13th Bn. The King's Regiment (Liverpool)

Chindit Column: Northern Group Head Quarters.

Other details:

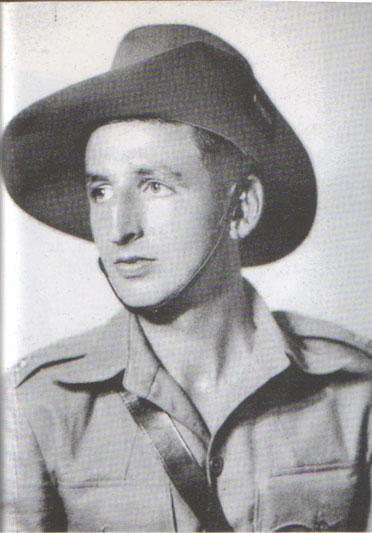

Edward Palmer was born on the 10th March 1913 and lived and worked in Dagenham, Essex. At the time of his service with the 13th King's he lived with his wife Isabella at 56 Vincent Road in Dagenham. He was a member of Northern Group Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth, which was the command centre for Columns 3, 4, 5, 7 and 8 within the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade and was led by Lieutenant-Colonel S.A. Cooke.

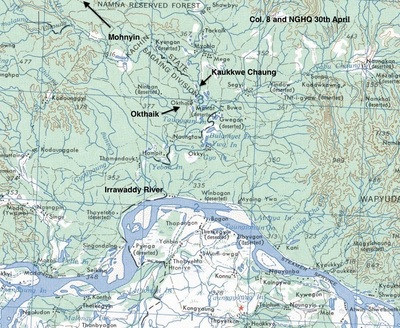

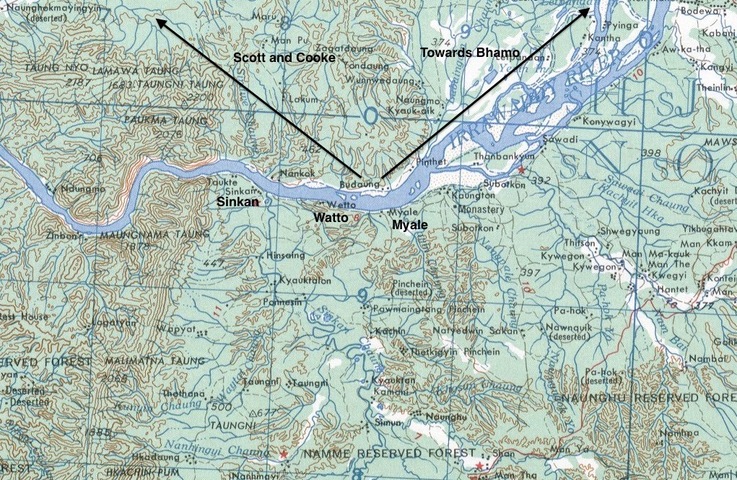

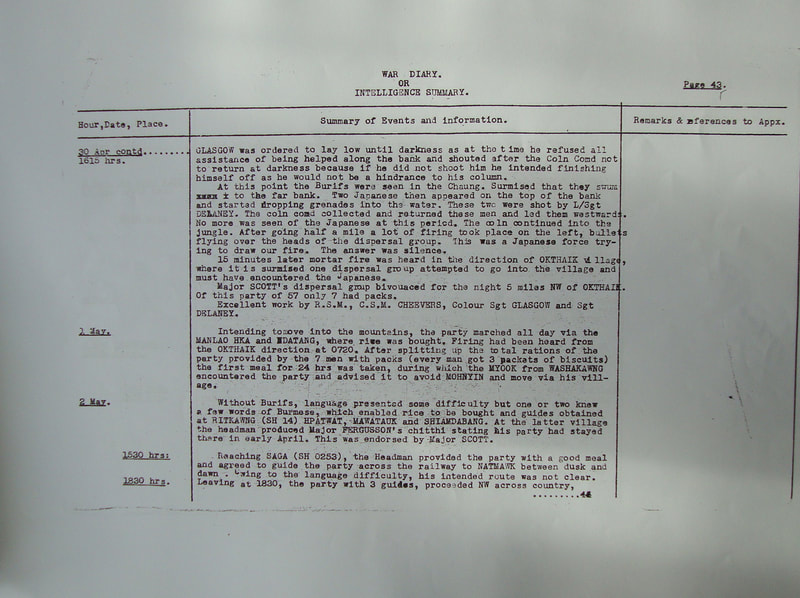

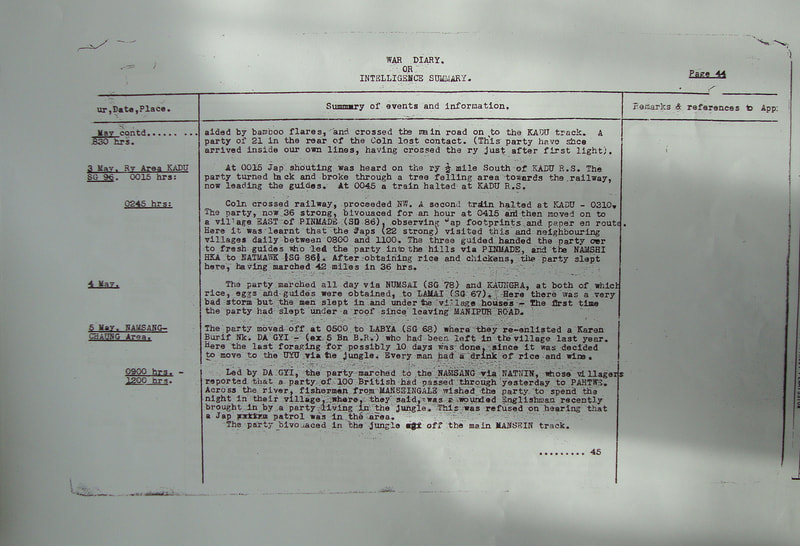

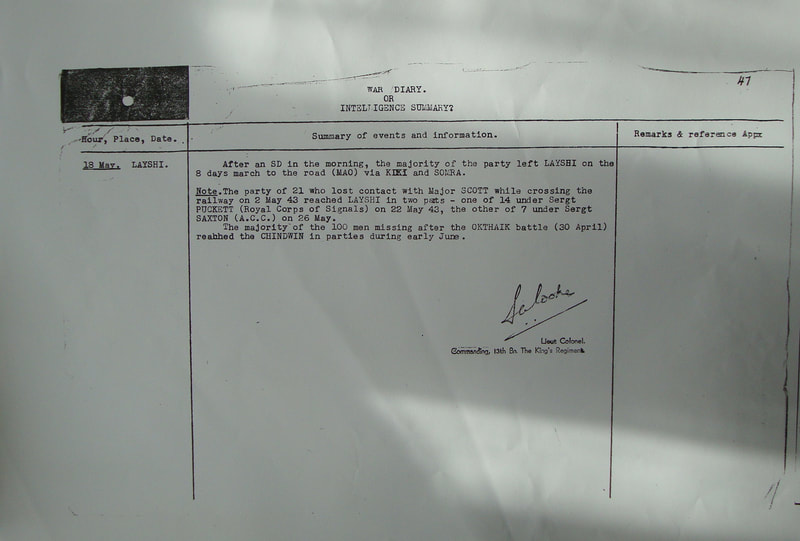

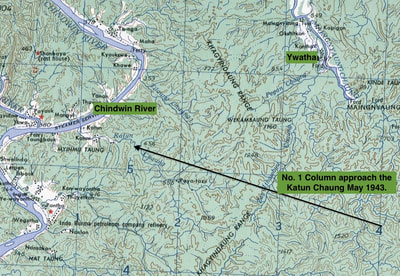

Northern Group HQ spent most of its time in Burma in close association with Column 8 commanded by Major Walter Purcell Scott of the King's Regiment. When the time came to return to India, Colonel Cooke decided to disperse with Column 8 and the two groups merged to form one large unit of approximately 400 personnel. By mid-April the decision was made to break the column up into smaller dispersal parties, this was organised and many of the groups separated at this point.

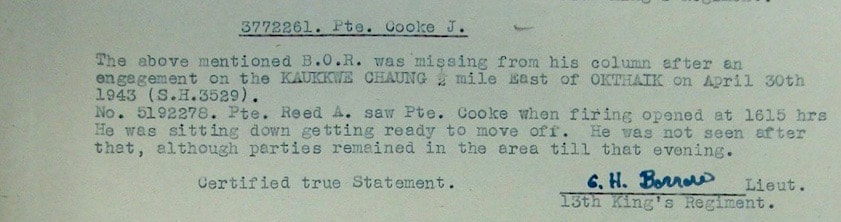

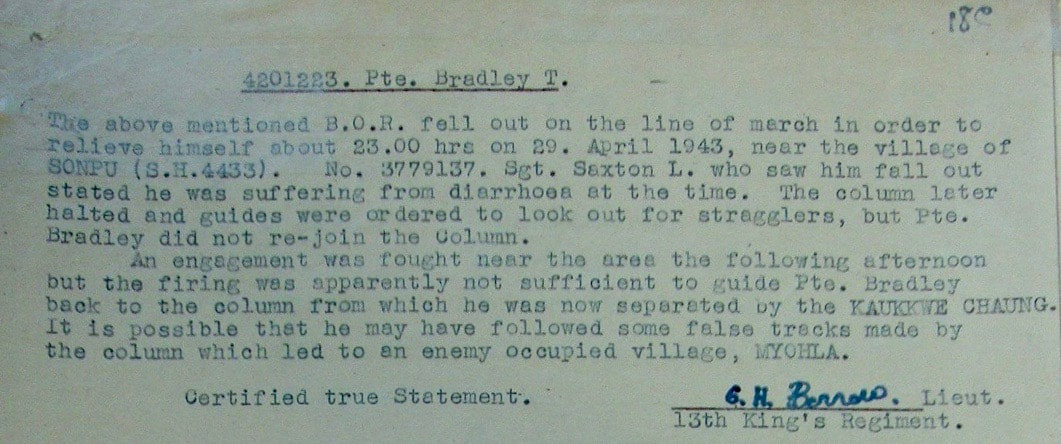

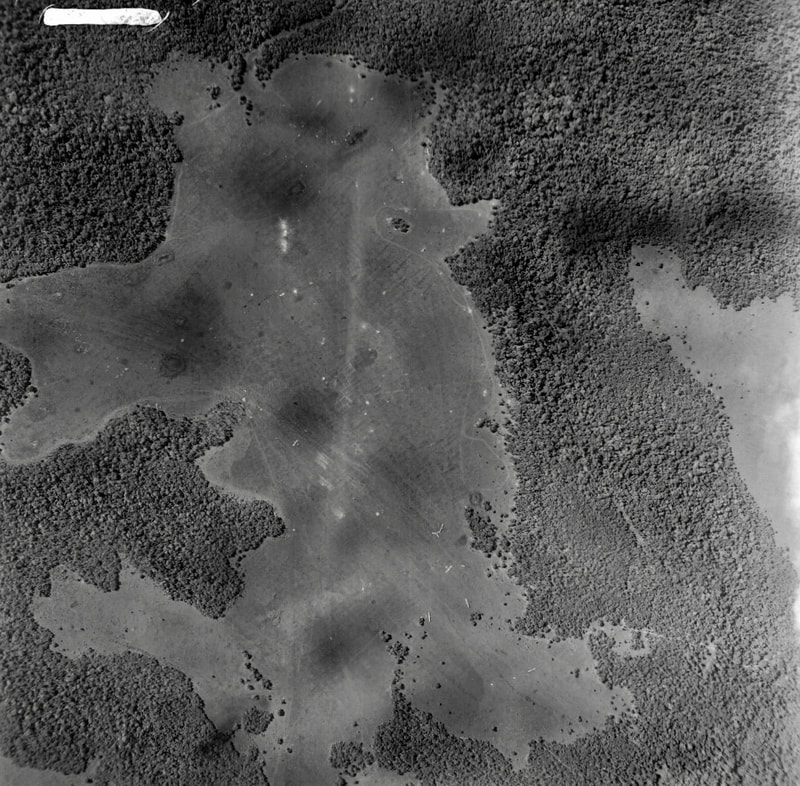

Scott and Cooke remained together and were in the area around the Kaukkwe Chaung when they were ambushed by the Japanese whilst crossing the narrow, but fast flowing river close to the village of Okthaik. Many men were killed and others wounded at Kaukkwe Chaung on the 30th April 1943, the survivors quickly formed up into small dispersal groups and headed off westwards. It is very possible that this is where Edward Palmer became detached from the main party of Column 8.

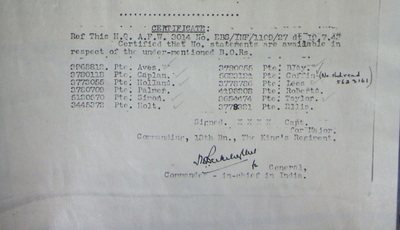

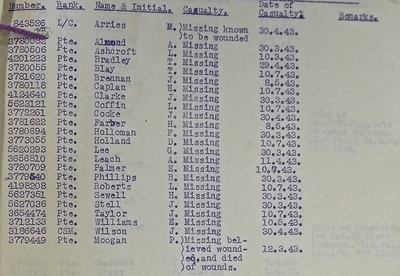

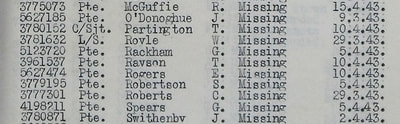

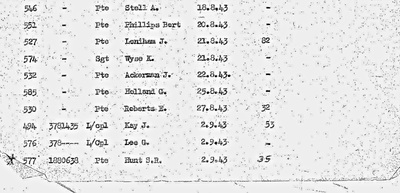

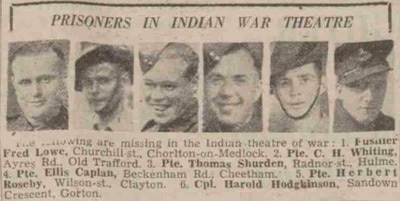

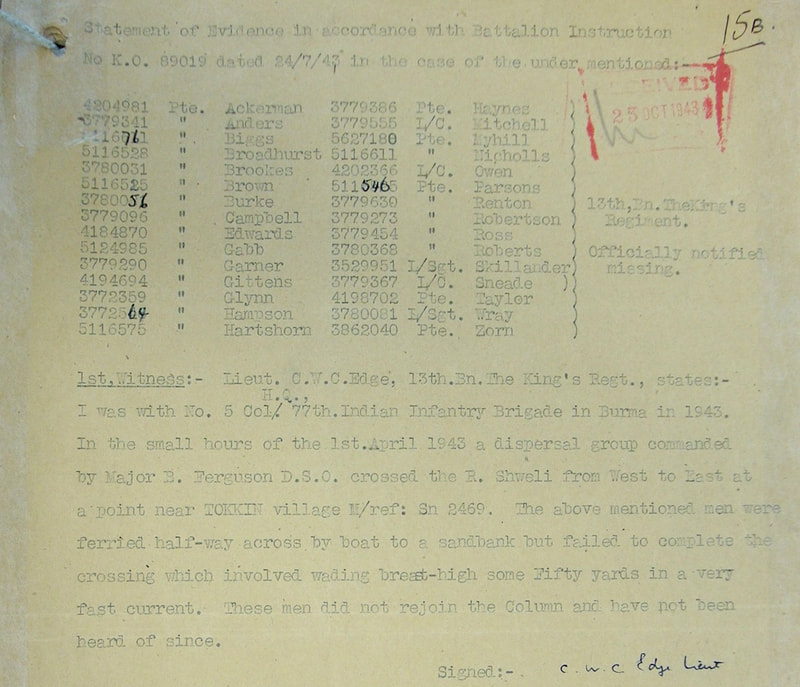

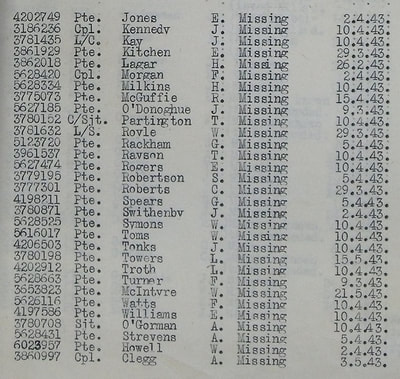

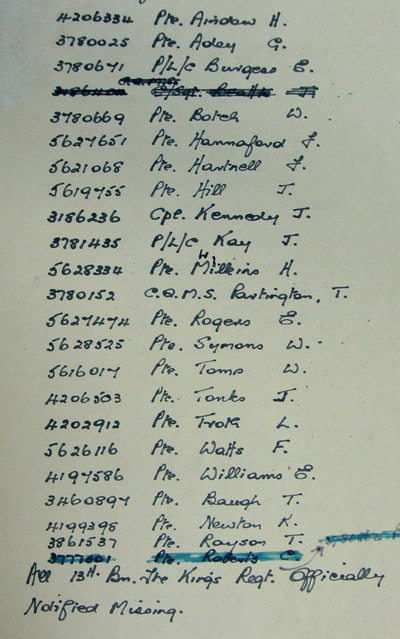

Nothing much is known about this period of time in regard to Pte. Palmer or the other men with him. However, in the missing in action lists for the 13th King's and more precisely, those for Northern Group HQ, it is possible to link together a group of 5/6 men. These men have the same missing date, 10/07/1943. This date was given to soldiers who were missing, but known to have later become prisoners of war. The date does not really relate to an exact time of capture for the individual, rather that he had become a POW and was now present at Rangoon Jail.

The men who may well have been with Edward at the point of dispersal after the action at the Kaukkwe Chaung are:

Pte. E. Caplan

Pte. L. Coffin

Pte. D. Holland

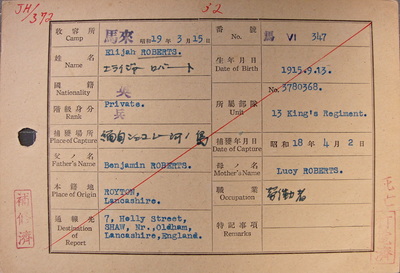

Pte. E. Roberts

Pte. J. Taylor

'Sid' Caplan, Leonard Coffin and Ted Palmer all survived their time as prisoners of war, Douglas Holland and Elias Roberts sadly perished inside Rangoon Jail and John Taylor was lost to the group somewhere close to the Irrawaddy River and was never seen again.

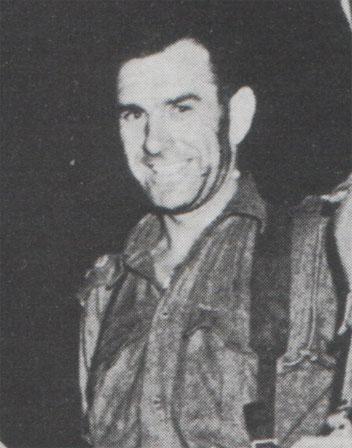

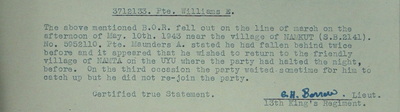

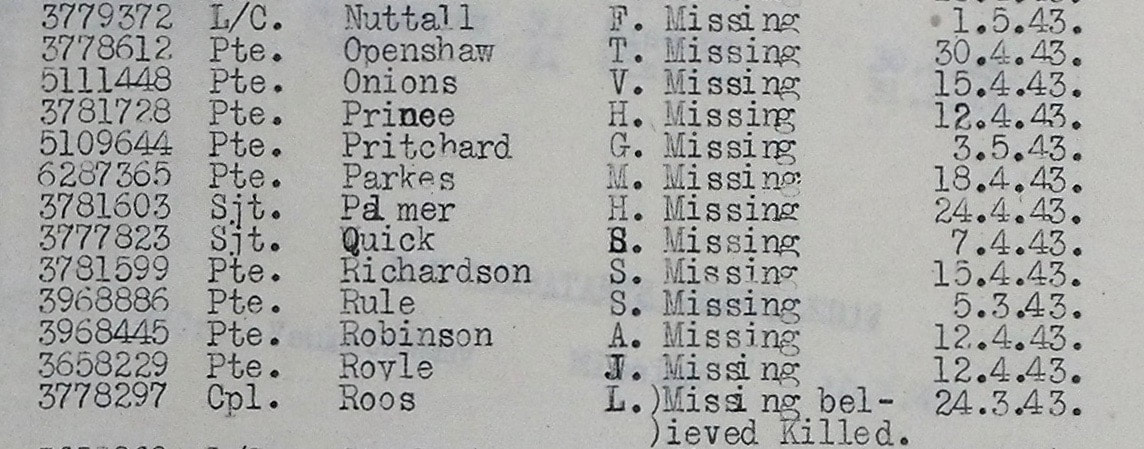

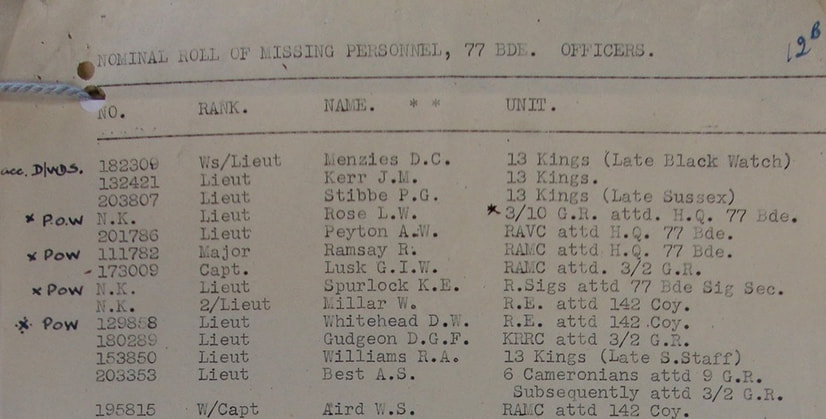

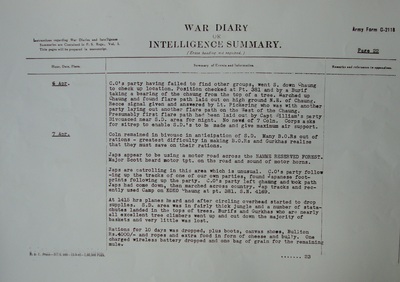

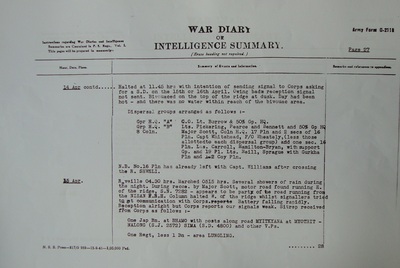

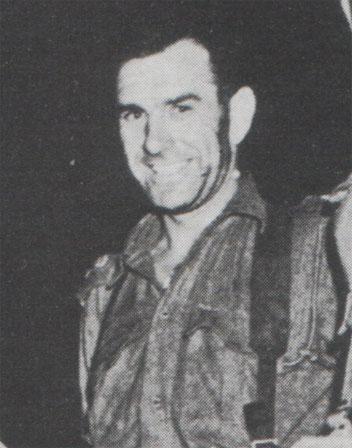

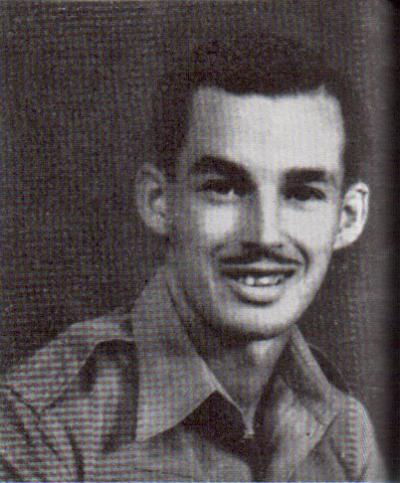

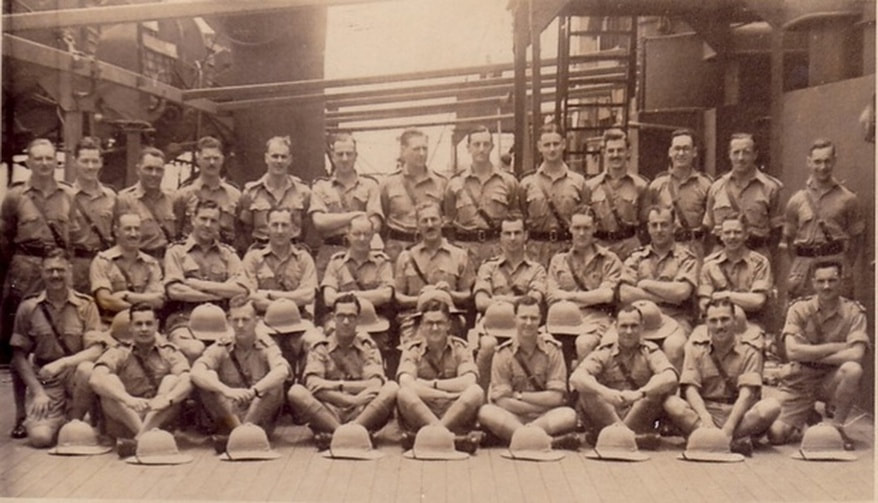

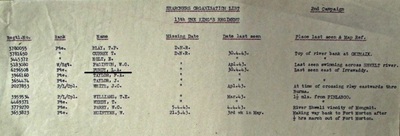

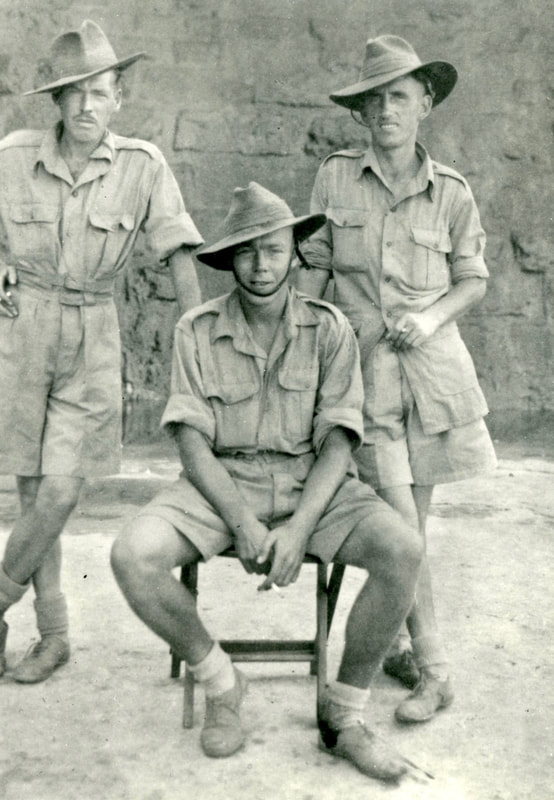

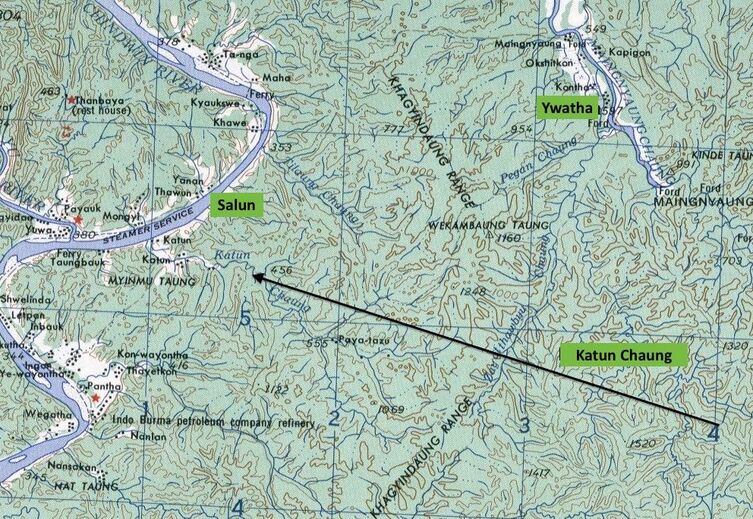

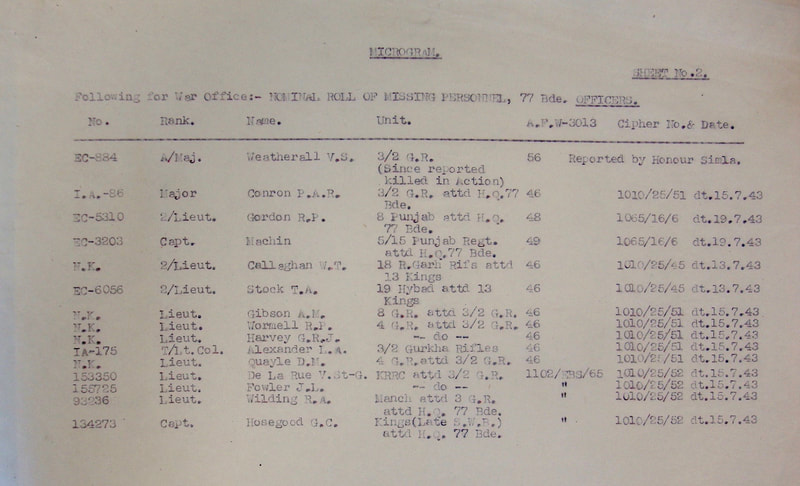

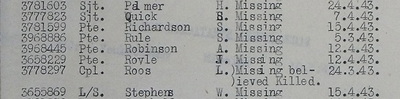

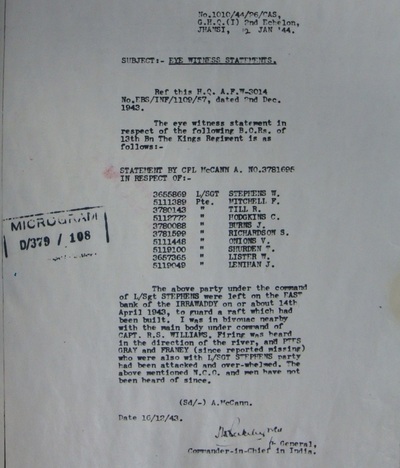

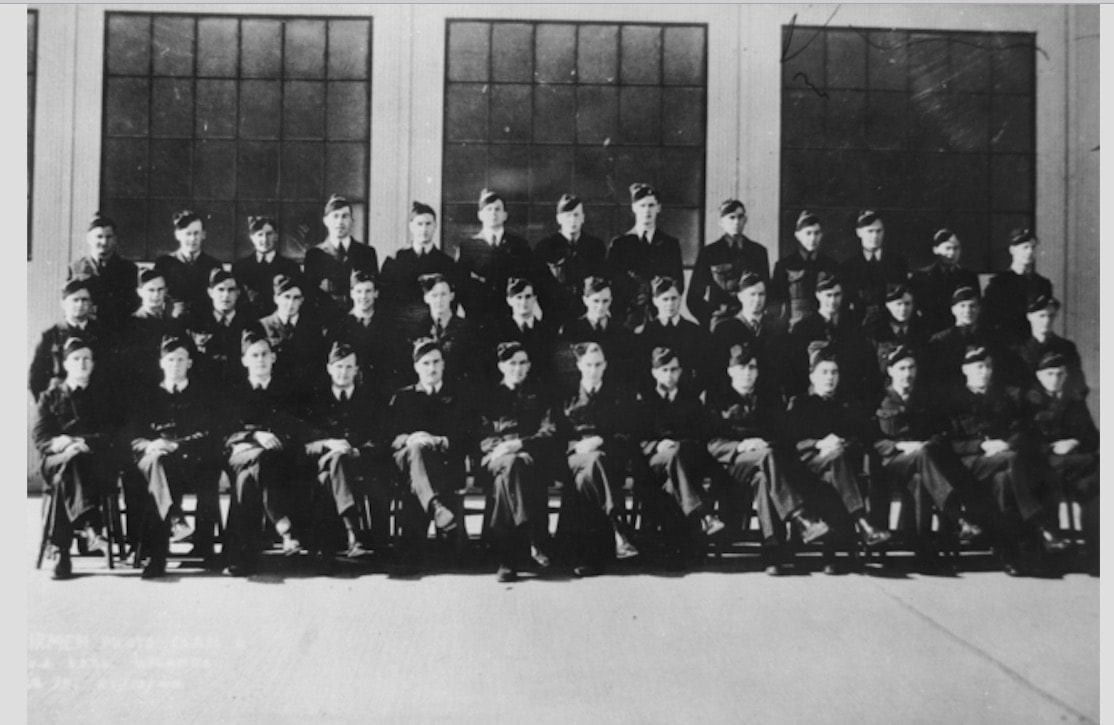

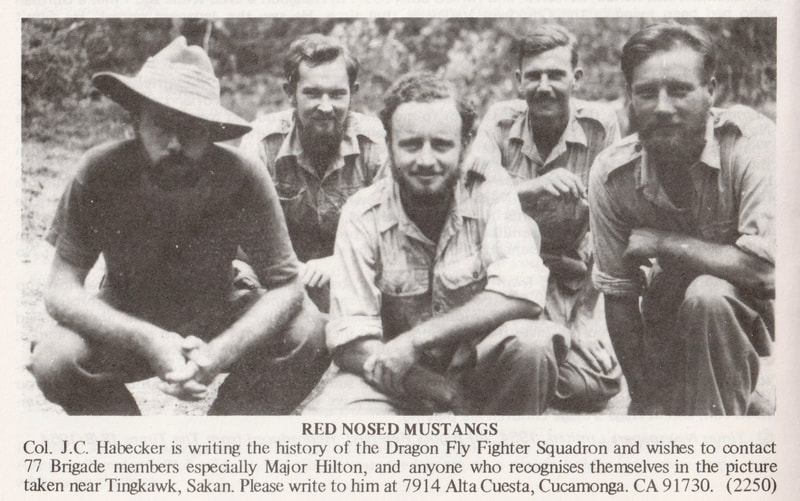

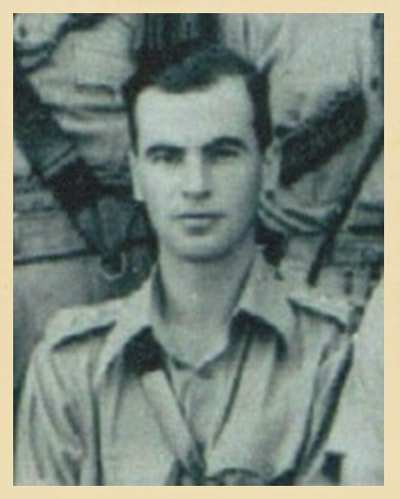

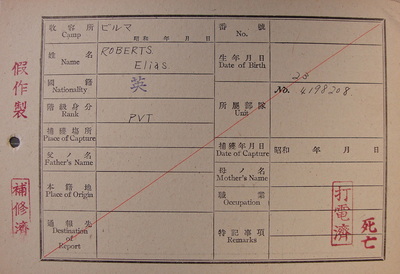

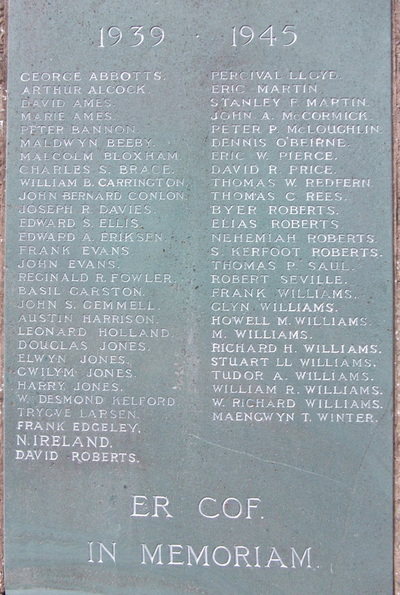

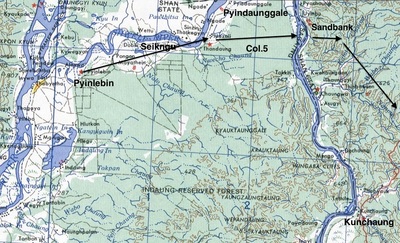

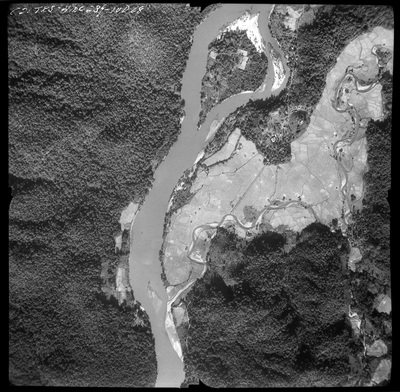

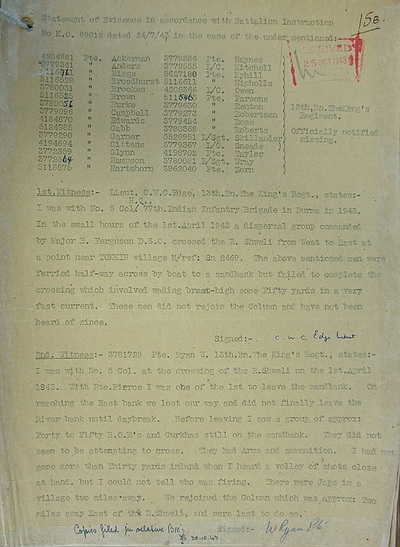

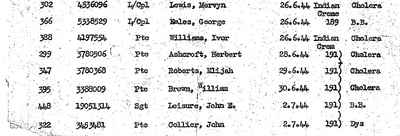

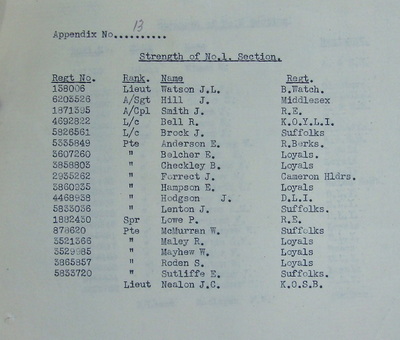

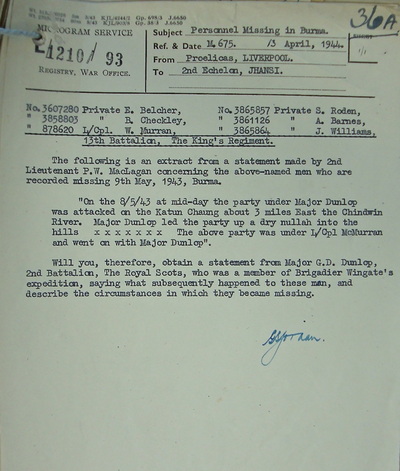

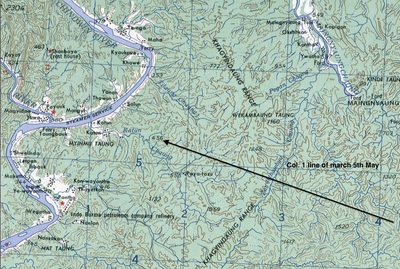

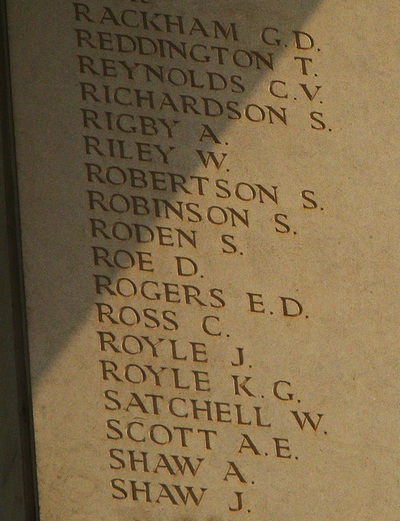

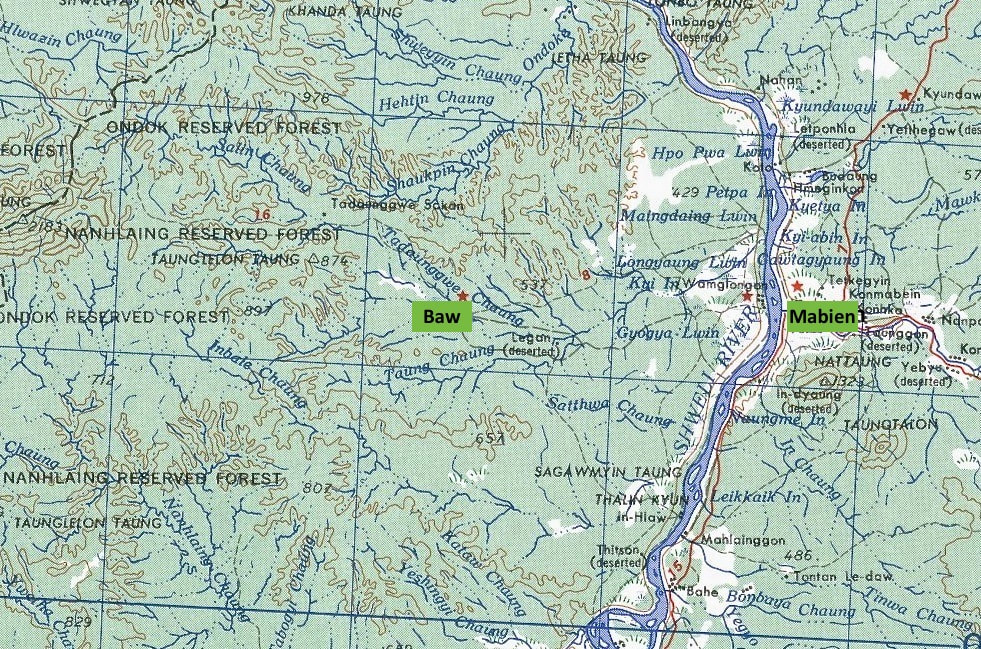

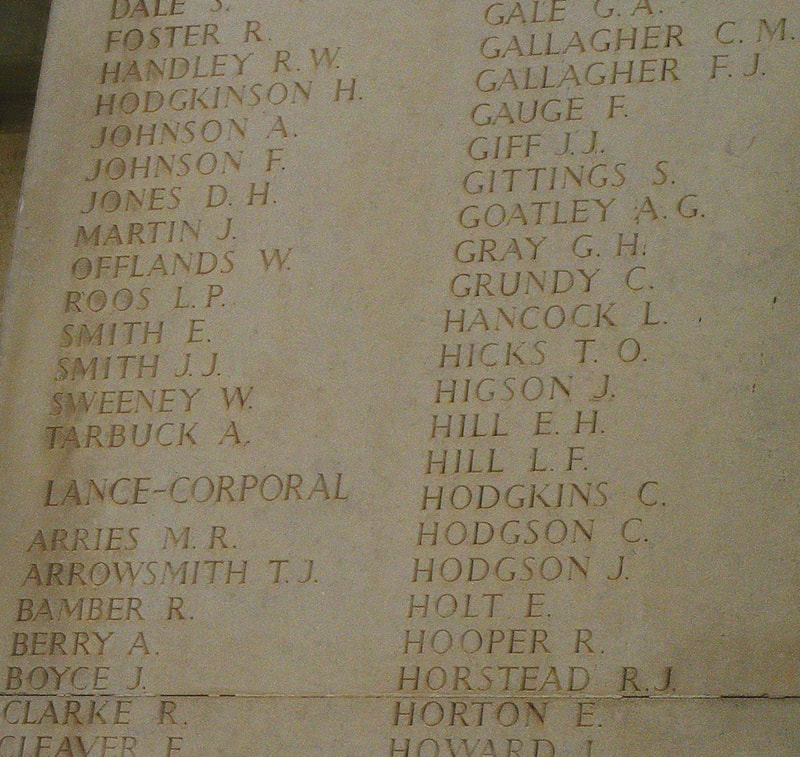

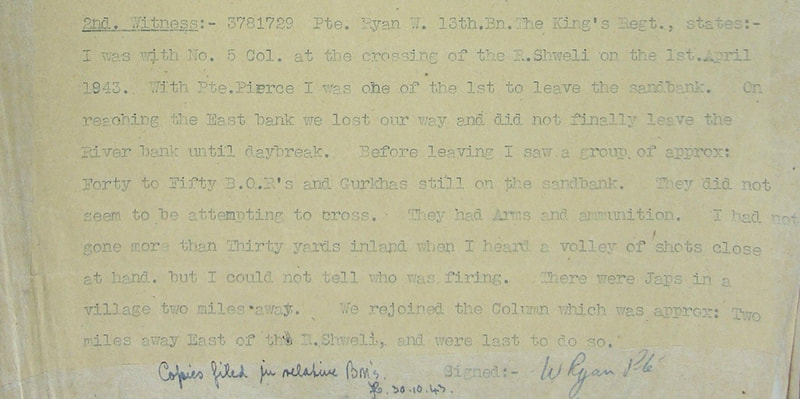

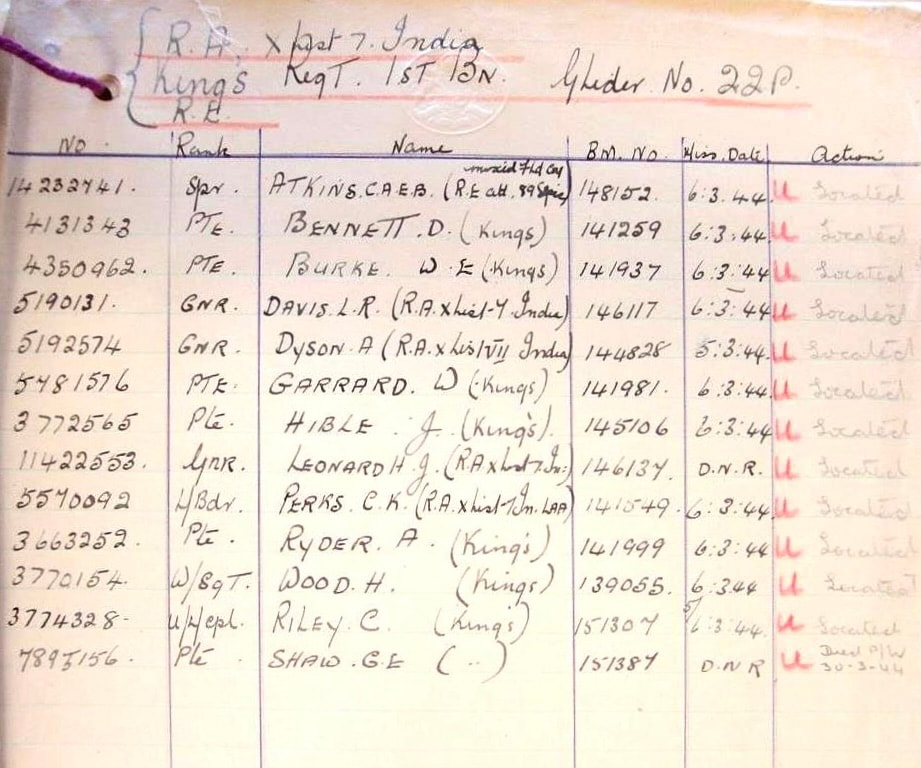

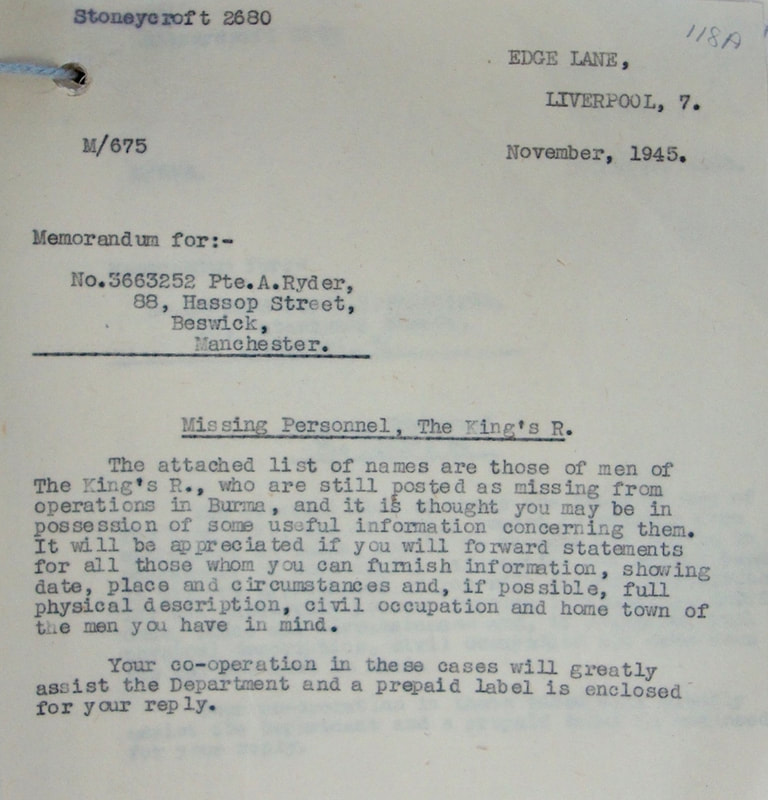

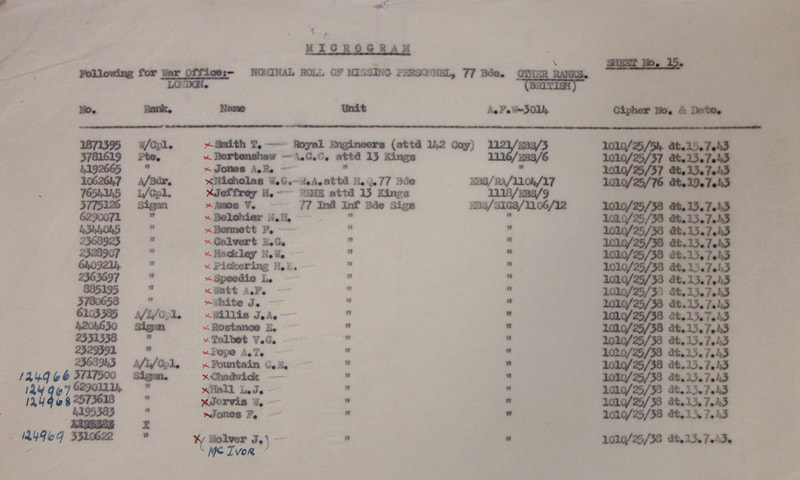

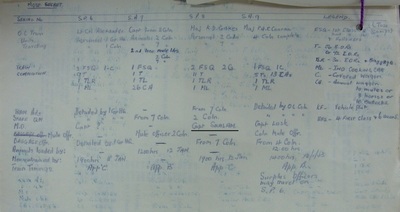

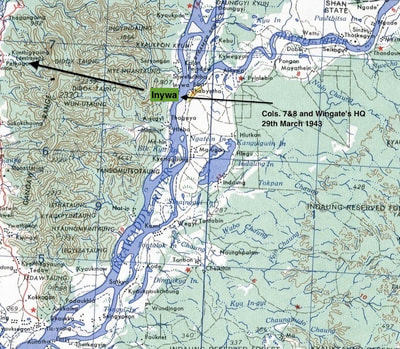

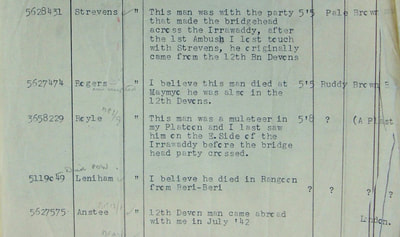

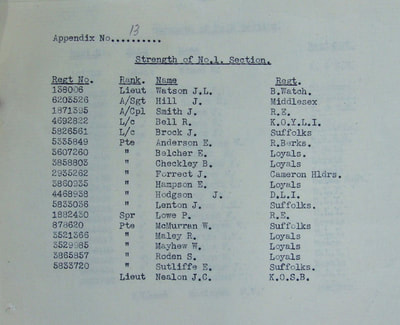

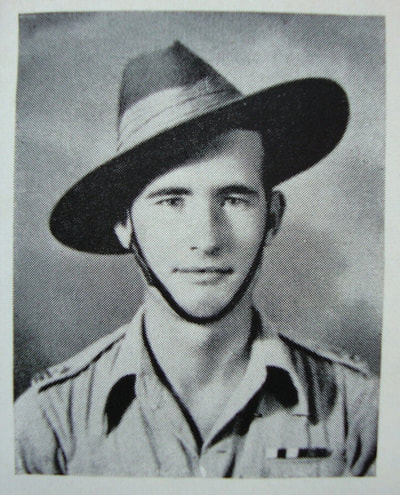

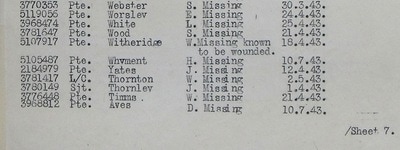

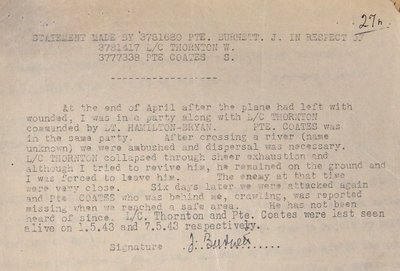

Seen below are four images, one is a map of the area around the Kaukkwe Chaung, which was the location of the action with the Japanese on the 30th April. The other is a list of men shown in the missing in action files for the 13th King's, including the men mentioned above. The fact that they are listed together could be significant, or, it could just be coincidental. Also shown are two photographs sent to me by Mike Coffin, the son of Pte. Leonard Coffin. Perhaps some of the other men mentioned in this story are present in the group image. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

NB. It is now known (May 2015), that Leonard Coffin was not with the group of men that crossed the Kaukkwe Chaung on the 30th April 1943 and instead had been part of Wingate's own Brigade Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth. To read more about his story please click on the following link: Pte. Leonard Coffin

Rank: Private

Service No: 3780709

Age: 30

Regiment/Service: 13th Bn. The King's Regiment (Liverpool)

Chindit Column: Northern Group Head Quarters.

Other details:

Edward Palmer was born on the 10th March 1913 and lived and worked in Dagenham, Essex. At the time of his service with the 13th King's he lived with his wife Isabella at 56 Vincent Road in Dagenham. He was a member of Northern Group Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth, which was the command centre for Columns 3, 4, 5, 7 and 8 within the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade and was led by Lieutenant-Colonel S.A. Cooke.

Northern Group HQ spent most of its time in Burma in close association with Column 8 commanded by Major Walter Purcell Scott of the King's Regiment. When the time came to return to India, Colonel Cooke decided to disperse with Column 8 and the two groups merged to form one large unit of approximately 400 personnel. By mid-April the decision was made to break the column up into smaller dispersal parties, this was organised and many of the groups separated at this point.

Scott and Cooke remained together and were in the area around the Kaukkwe Chaung when they were ambushed by the Japanese whilst crossing the narrow, but fast flowing river close to the village of Okthaik. Many men were killed and others wounded at Kaukkwe Chaung on the 30th April 1943, the survivors quickly formed up into small dispersal groups and headed off westwards. It is very possible that this is where Edward Palmer became detached from the main party of Column 8.

Nothing much is known about this period of time in regard to Pte. Palmer or the other men with him. However, in the missing in action lists for the 13th King's and more precisely, those for Northern Group HQ, it is possible to link together a group of 5/6 men. These men have the same missing date, 10/07/1943. This date was given to soldiers who were missing, but known to have later become prisoners of war. The date does not really relate to an exact time of capture for the individual, rather that he had become a POW and was now present at Rangoon Jail.

The men who may well have been with Edward at the point of dispersal after the action at the Kaukkwe Chaung are:

Pte. E. Caplan

Pte. L. Coffin

Pte. D. Holland

Pte. E. Roberts

Pte. J. Taylor

'Sid' Caplan, Leonard Coffin and Ted Palmer all survived their time as prisoners of war, Douglas Holland and Elias Roberts sadly perished inside Rangoon Jail and John Taylor was lost to the group somewhere close to the Irrawaddy River and was never seen again.

Seen below are four images, one is a map of the area around the Kaukkwe Chaung, which was the location of the action with the Japanese on the 30th April. The other is a list of men shown in the missing in action files for the 13th King's, including the men mentioned above. The fact that they are listed together could be significant, or, it could just be coincidental. Also shown are two photographs sent to me by Mike Coffin, the son of Pte. Leonard Coffin. Perhaps some of the other men mentioned in this story are present in the group image. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

NB. It is now known (May 2015), that Leonard Coffin was not with the group of men that crossed the Kaukkwe Chaung on the 30th April 1943 and instead had been part of Wingate's own Brigade Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth. To read more about his story please click on the following link: Pte. Leonard Coffin

For more information about the battle at Kaukkwe Chaung, please follow the link provided below:

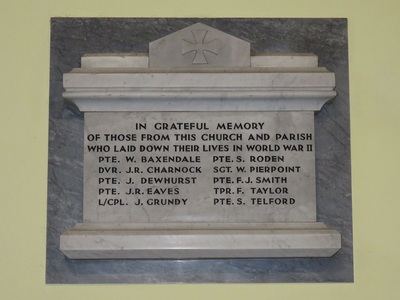

Frank Lea, Ellis Grundy and the Kaukkwe Chaung

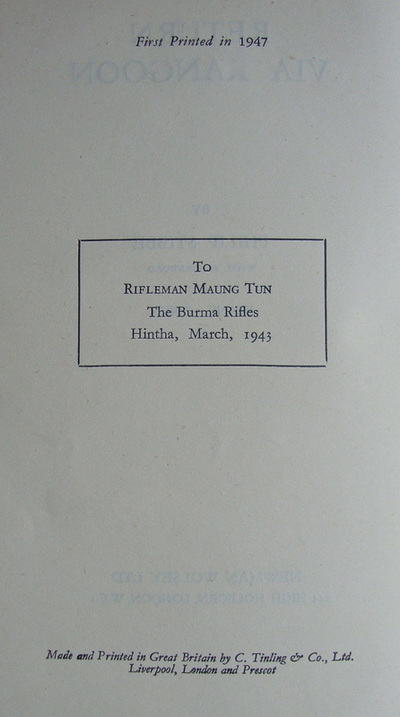

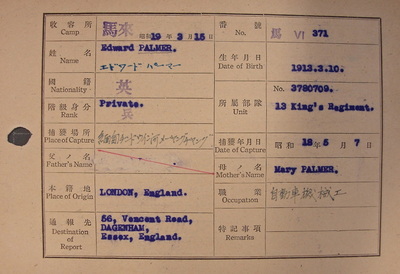

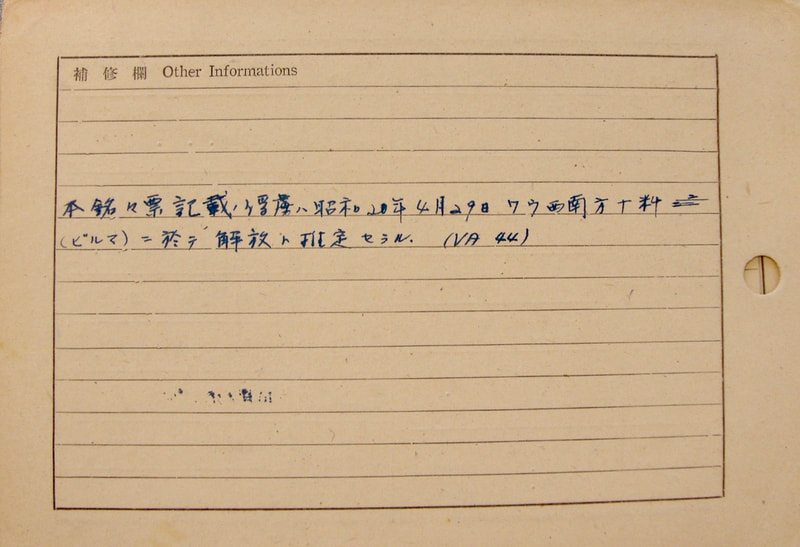

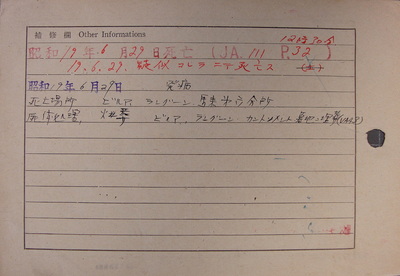

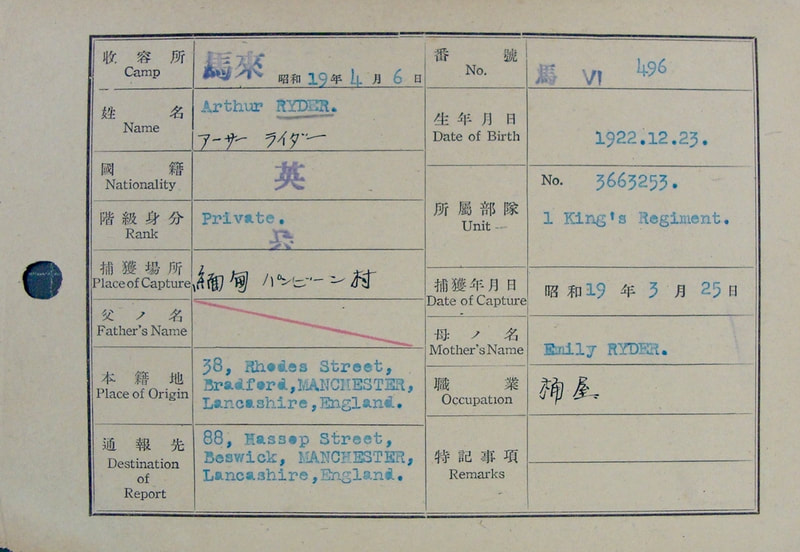

According to Edward's POW records in the form of his prisoner index card, he was captured on the 7th May 1943 close to the banks of the Chindwin River. This means he was at large in the Burmese Jungle for about a week after the action at Kaukkwe and presumably had moved steadily in a westward direction before being captured at this final hurdle. He was taken to the POW concentration camp at Maymyo, before being sent down to Rangoon Jail by train in late May or early June.

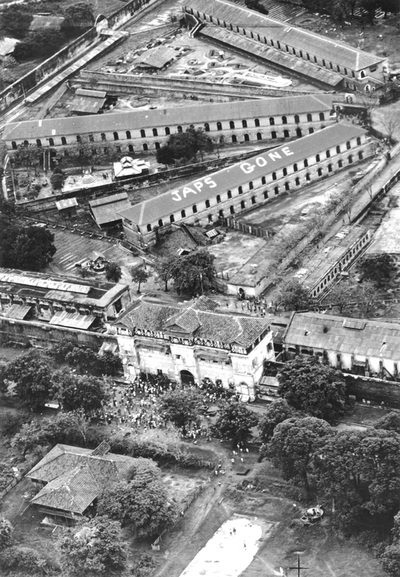

He received his own unique POW number of 371 when he arrived at Rangoon, he would learn how to recite this number in Japanese at tenko roll calls every morning and evening for the rest of his time as a prisoner of war. All the captured Chindits were initially held in Block 6 of the prison, suffering very cramped and insanitary conditions, some, already malnourished and exhausted from their tribulations in Burma perished almost immediately.

For more information about Rangoon Jail and Maymyo Camp, please follow the link below:

Chindit POW's

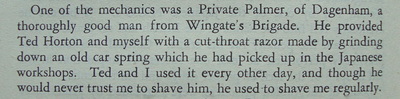

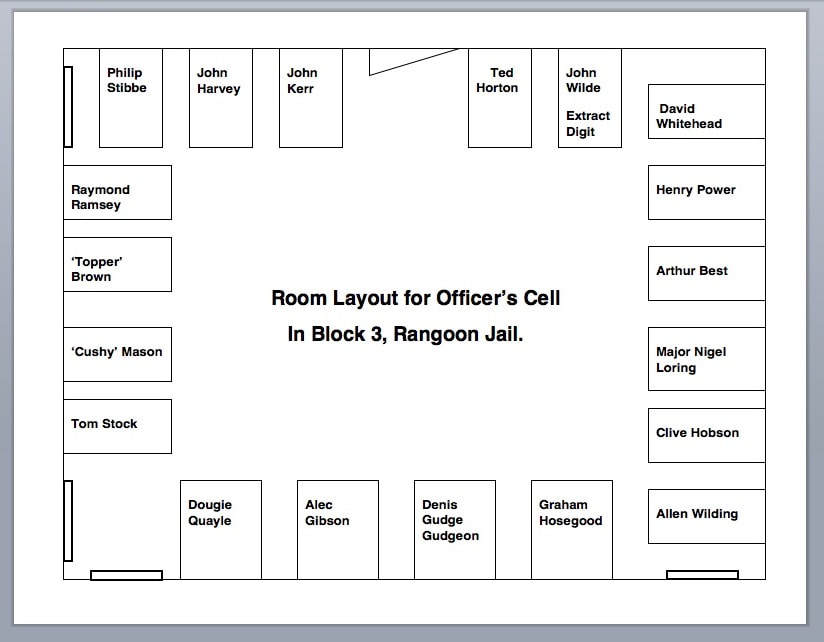

Ted Palmer was not destined to be one of these unfortunate men. He slowly settled down to prison life in Rangoon and is in fact mentioned in one of the books written by a surviving Chindit Officer from Operation Longcloth. Lieutenant Philip Stibbe, in his book entitled 'Return via Rangoon' remembered Pte. Palmer and more specifically his engineering expertise:

"All the men in three block with any mechanical ability were made to work in Japanese workshops some distance outside of Rangoon. They all lived in the same room in the block and formed what was known as the mechanics platoon.

Graham Hosegood was the officer in charge of them, but he fell ill at the end of 1944 and had to return to 6 Block. He had always been most solicitous for the welfare of the men and he was widely mourned when he died in early 1945; his patience and cheerful friendliness had made him universally popular. When Graham went over to 6 Block I was put in charge of the mechanics platoon or the 'scruffs' as they called themselves after I had lectured them about their personal appearance and reproved them for being 'scruffy'.

Sergeant Smeraldo became my platoon Sergeant and we made ourselves most unpopular for a week or two by carrying on a 'smartening up' campaign in the platoon. However, after a certain amount of unpleasantness the scruffs seemed to settle down to the new regime quite well.

One of the mechanics was a Private Palmer, of Dagenham, a thoroughly good man from Wingate's Brigade. He provided Ted Horton and myself with a cut-throat razor made by grinding down an old car spring which he had picked up in the Japanese workshops. Ted and I used it every other day, and though he would never trust me to shave him, he used to shave me regularly."

It should be understood that it is very unusual for a Private soldier to be mentioned in a book or diary written about those times, especially by an officer, so it would appear that Pte. Palmer's skill in fashioning the razor must have had a lasting effect on Lieutenant Stibbe during his time as a prisoner of war.

As the war began to go against the Japanese, Allied war planes in the skies over Rangoon became a morale boosting sight for the beleaguered POW's. However, this situation came at a cost. Here is another quote taken from Philip Stibbe's book;

"Eventually Allied bombing raids became more frequent and heavier, they seemed to be concentrated on the Japanese dumps and workshops on the outskirts of Rangoon and on Mingladon Airfield. We had a very good view of the massed daylight raids : sometimes nearly 150 Fortresses came over, but our exhilaration at the sight of so much destruction was often marred by the knowledge that the mechanics platoon were working in workshops in the middle of the target area."

So, as you can see Ted Palmer was in constant danger whilst performing his role with the Rangoon Jail mechanics and in actual fact the prison itself received a direct hit from 'friendly fire' in late November 1943 where several prisoners and some Japanese guards were killed.

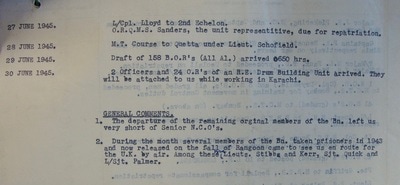

In the spring of 1945, as the the advancing 14th Army led by Bill Slim were closing in on Rangoon, an order was given for the occupying Japanese garrison to evacuate the city and the decision was made to take the fittest of the prisoners inside Rangoon Jail with them. Edward Palmer was amongst the 400 men chosen by the jail guards and the march commenced on the 25th April.

After four arduous days marching, the Japanese finally gave up the idea of trying to take the Allied POW's with them, as they attempted to exit Burma and cross the border into Siam. The 400 men were given their freedom on the 29th April at a village called Waw, near the town of Pegu. After an uncomfortable night spent in the scrub-jungle and some near misses with yet more 'friendly-fire', the men were liberated by a company of the West Yorkshire Regiment. Eventually Dakota planes were organised and the POW's were flown out to India and received hospital treatment for their various ailments and diseases. A period of rest and recuperation followed before the men were returned to their various Regimental units.

Pte. Edward Palmer would have returned to the 13th King's who by this time were garrisoned at Karachi. Eventually, he was repatriated back home to the United Kingdom.

Seen below are some photographs and images relating to the above story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page or simply click on the forward arrow to view the next image in the gallery.

Frank Lea, Ellis Grundy and the Kaukkwe Chaung

According to Edward's POW records in the form of his prisoner index card, he was captured on the 7th May 1943 close to the banks of the Chindwin River. This means he was at large in the Burmese Jungle for about a week after the action at Kaukkwe and presumably had moved steadily in a westward direction before being captured at this final hurdle. He was taken to the POW concentration camp at Maymyo, before being sent down to Rangoon Jail by train in late May or early June.

He received his own unique POW number of 371 when he arrived at Rangoon, he would learn how to recite this number in Japanese at tenko roll calls every morning and evening for the rest of his time as a prisoner of war. All the captured Chindits were initially held in Block 6 of the prison, suffering very cramped and insanitary conditions, some, already malnourished and exhausted from their tribulations in Burma perished almost immediately.

For more information about Rangoon Jail and Maymyo Camp, please follow the link below:

Chindit POW's

Ted Palmer was not destined to be one of these unfortunate men. He slowly settled down to prison life in Rangoon and is in fact mentioned in one of the books written by a surviving Chindit Officer from Operation Longcloth. Lieutenant Philip Stibbe, in his book entitled 'Return via Rangoon' remembered Pte. Palmer and more specifically his engineering expertise:

"All the men in three block with any mechanical ability were made to work in Japanese workshops some distance outside of Rangoon. They all lived in the same room in the block and formed what was known as the mechanics platoon.

Graham Hosegood was the officer in charge of them, but he fell ill at the end of 1944 and had to return to 6 Block. He had always been most solicitous for the welfare of the men and he was widely mourned when he died in early 1945; his patience and cheerful friendliness had made him universally popular. When Graham went over to 6 Block I was put in charge of the mechanics platoon or the 'scruffs' as they called themselves after I had lectured them about their personal appearance and reproved them for being 'scruffy'.

Sergeant Smeraldo became my platoon Sergeant and we made ourselves most unpopular for a week or two by carrying on a 'smartening up' campaign in the platoon. However, after a certain amount of unpleasantness the scruffs seemed to settle down to the new regime quite well.

One of the mechanics was a Private Palmer, of Dagenham, a thoroughly good man from Wingate's Brigade. He provided Ted Horton and myself with a cut-throat razor made by grinding down an old car spring which he had picked up in the Japanese workshops. Ted and I used it every other day, and though he would never trust me to shave him, he used to shave me regularly."

It should be understood that it is very unusual for a Private soldier to be mentioned in a book or diary written about those times, especially by an officer, so it would appear that Pte. Palmer's skill in fashioning the razor must have had a lasting effect on Lieutenant Stibbe during his time as a prisoner of war.

As the war began to go against the Japanese, Allied war planes in the skies over Rangoon became a morale boosting sight for the beleaguered POW's. However, this situation came at a cost. Here is another quote taken from Philip Stibbe's book;

"Eventually Allied bombing raids became more frequent and heavier, they seemed to be concentrated on the Japanese dumps and workshops on the outskirts of Rangoon and on Mingladon Airfield. We had a very good view of the massed daylight raids : sometimes nearly 150 Fortresses came over, but our exhilaration at the sight of so much destruction was often marred by the knowledge that the mechanics platoon were working in workshops in the middle of the target area."

So, as you can see Ted Palmer was in constant danger whilst performing his role with the Rangoon Jail mechanics and in actual fact the prison itself received a direct hit from 'friendly fire' in late November 1943 where several prisoners and some Japanese guards were killed.

In the spring of 1945, as the the advancing 14th Army led by Bill Slim were closing in on Rangoon, an order was given for the occupying Japanese garrison to evacuate the city and the decision was made to take the fittest of the prisoners inside Rangoon Jail with them. Edward Palmer was amongst the 400 men chosen by the jail guards and the march commenced on the 25th April.

After four arduous days marching, the Japanese finally gave up the idea of trying to take the Allied POW's with them, as they attempted to exit Burma and cross the border into Siam. The 400 men were given their freedom on the 29th April at a village called Waw, near the town of Pegu. After an uncomfortable night spent in the scrub-jungle and some near misses with yet more 'friendly-fire', the men were liberated by a company of the West Yorkshire Regiment. Eventually Dakota planes were organised and the POW's were flown out to India and received hospital treatment for their various ailments and diseases. A period of rest and recuperation followed before the men were returned to their various Regimental units.

Pte. Edward Palmer would have returned to the 13th King's who by this time were garrisoned at Karachi. Eventually, he was repatriated back home to the United Kingdom.

Seen below are some photographs and images relating to the above story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page or simply click on the forward arrow to view the next image in the gallery.

On the 3rd November 2013 I was fortunate to receive a contact email from Suzanne Bass, who is one of Ted Palmer's grandchildren. Here is what Suzanne had to say in her email correspondence:

Hello Steve,

My mother would dearly love to gather any information about her father Edward Joseph Palmer, of the 13th Kings Regiment who survived Burma and his time as a prisoner of war. Thanking you in advance for any information or guidance you might be able to give.

Later on Suzanne told me that:

Ted Palmer was a devoted husband and father to his three daughters, Doreen, June and my mum Sylvia. I am one of nine grandchildren and he was loved and still is loved by us all, he will always be in our hearts.

My Granddad was a private man and did not speak about the war very much, he and his wife, Isabella, my Nan, had a wonderful marriage, we were and still are a very close knit family and used to spend most of our weekends at my Nan and Granddads home. My Granddad worked at Ford Motors at Dagenham for forty years and to my knowledge never took a day off sick.

When I read the quote from the book you sent over, I thought how typical it was of Ted, grinding down an old car spring to make it into a cut throat razor, I feel very proud and privileged that my Granddad was so highly thought of. I showed a college friend of mine the POW paper work for Ted and he said he would try to get the Japanese translated for me, we were always under the impression the he was a prisoner of war for five years?

Eventually Suzanne shared all the new information with her mother, Sylvia and the rest of the family. She told me that:

Words cannot express my gratitude to you for finding the information on my beloved Grandfather that my mum and I have so desperately wanted over the years. We had the family over for lunch on Sunday, St Patrick's day, and we were very exited to share the news that we have gathered about Ted.

I'd like to take this opportunity to thank Suzanne and Sylvia, for all their help in bringing this story to these pages.

Copyright © Steve Fogden July 2014.

Hello Steve,

My mother would dearly love to gather any information about her father Edward Joseph Palmer, of the 13th Kings Regiment who survived Burma and his time as a prisoner of war. Thanking you in advance for any information or guidance you might be able to give.

Later on Suzanne told me that:

Ted Palmer was a devoted husband and father to his three daughters, Doreen, June and my mum Sylvia. I am one of nine grandchildren and he was loved and still is loved by us all, he will always be in our hearts.

My Granddad was a private man and did not speak about the war very much, he and his wife, Isabella, my Nan, had a wonderful marriage, we were and still are a very close knit family and used to spend most of our weekends at my Nan and Granddads home. My Granddad worked at Ford Motors at Dagenham for forty years and to my knowledge never took a day off sick.

When I read the quote from the book you sent over, I thought how typical it was of Ted, grinding down an old car spring to make it into a cut throat razor, I feel very proud and privileged that my Granddad was so highly thought of. I showed a college friend of mine the POW paper work for Ted and he said he would try to get the Japanese translated for me, we were always under the impression the he was a prisoner of war for five years?

Eventually Suzanne shared all the new information with her mother, Sylvia and the rest of the family. She told me that:

Words cannot express my gratitude to you for finding the information on my beloved Grandfather that my mum and I have so desperately wanted over the years. We had the family over for lunch on Sunday, St Patrick's day, and we were very exited to share the news that we have gathered about Ted.

I'd like to take this opportunity to thank Suzanne and Sylvia, for all their help in bringing this story to these pages.

Copyright © Steve Fogden July 2014.

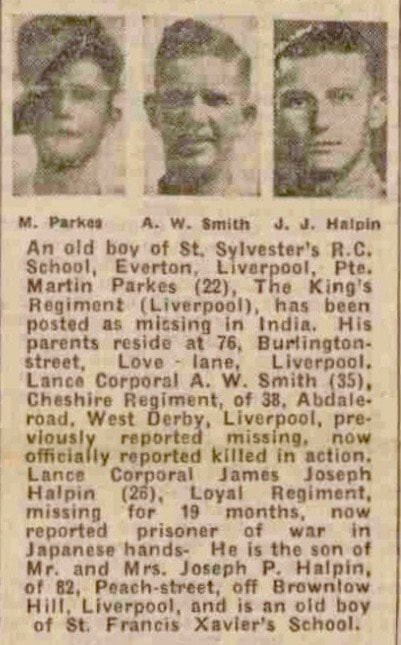

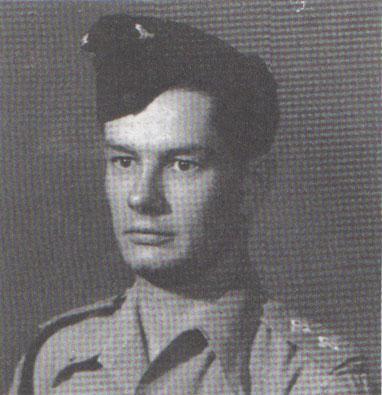

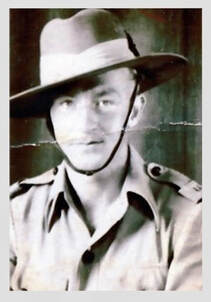

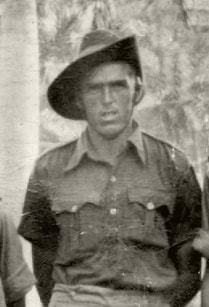

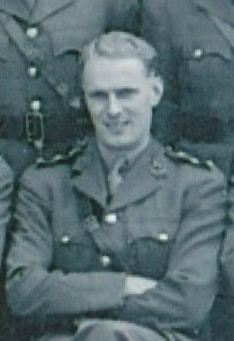

Pte. Martin Parkes.

Pte. Martin Parkes.

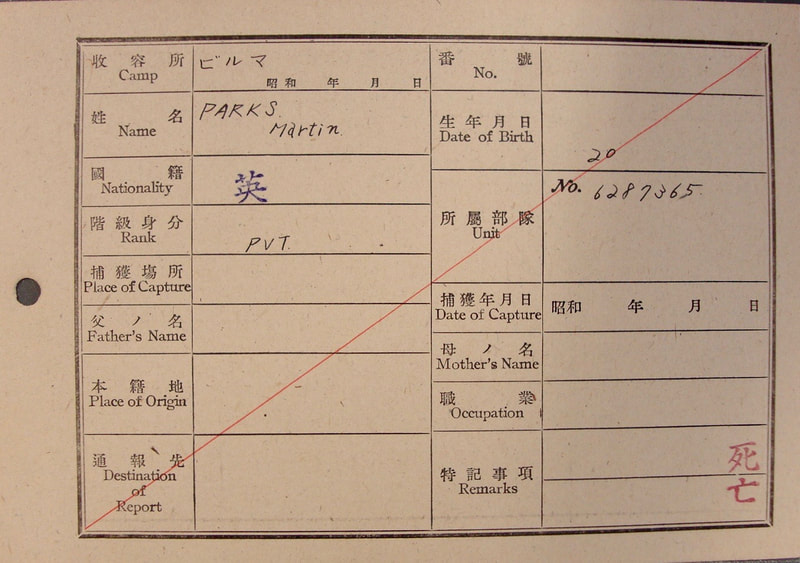

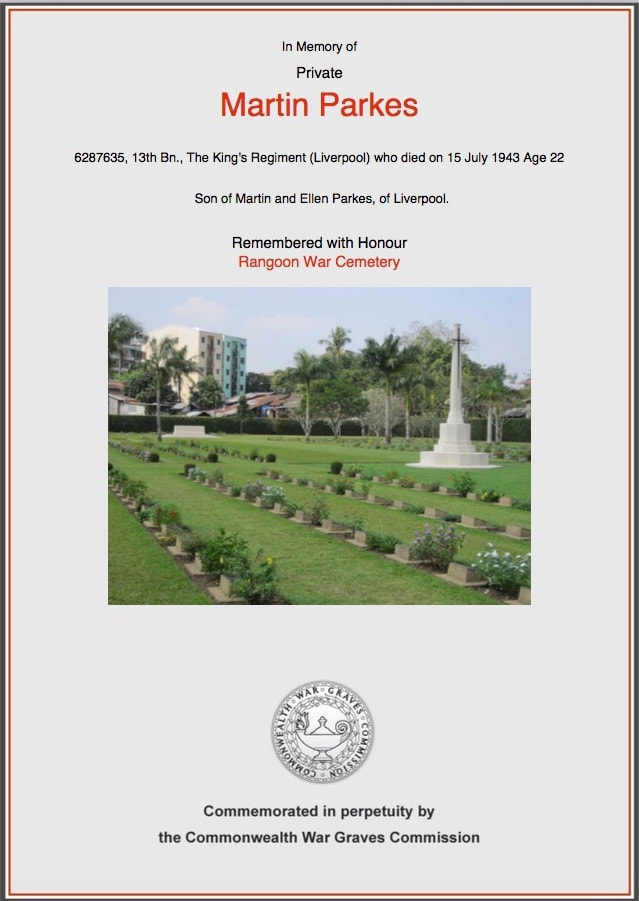

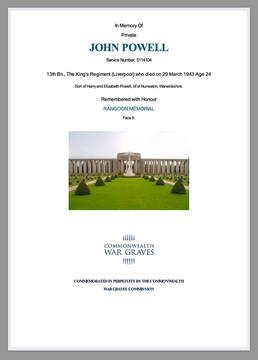

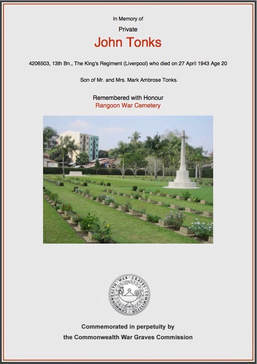

PARKES, MARTIN

Rank: Private

Service No: 6287635

Date of Death: 15/07/1943

Age: 22

Regiment/Service: 13th Bn. The King's Regiment (Liverpool)

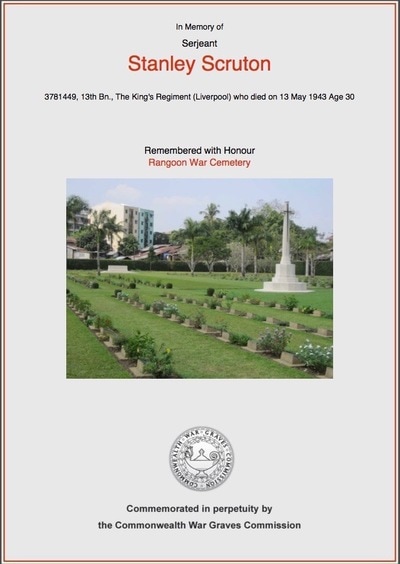

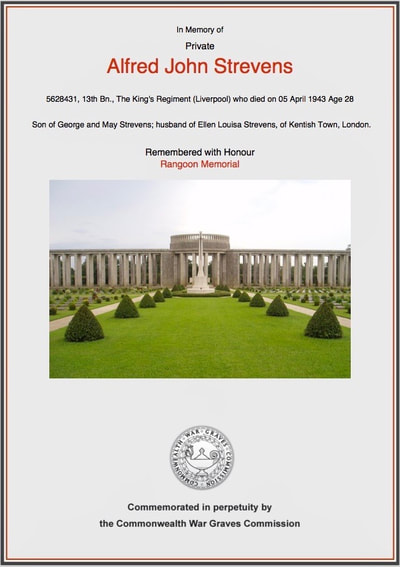

Memorial: Rangoon War Cemetery, Grave 9.B.12.

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2261059/parkes,-martin/

Chindit Column: 8

Other details:

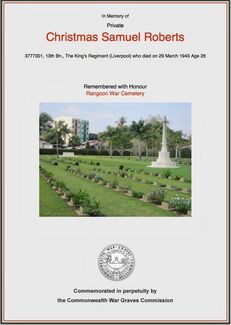

Martin Parkes was born in April 1912 and was the son of Martin (Senior) and Ellen Parkes from 76 Burlington Street in Liverpool. From his Army service number it can be ascertained that he had been originally posted to the Royal East Kent Regiment (known as the Buffs) during the earlier years of the war. By mid-1942 he had been sent overseas and transferred to the 13th Battalion of the King's (Liverpool) Regiment, who were training for the first Chindit expedition at Saugor in the Central Provinces of India. Pte. Parkes was allocated to No. 8 Column under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott.

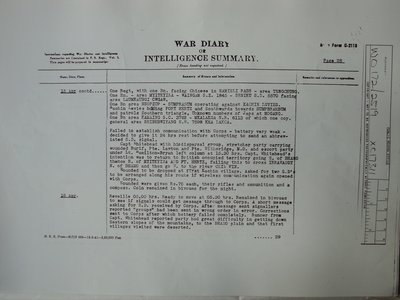

According to the official missing in action listings for No. 8 Column, Pte. Parkes was reported as last seen on the 18th April 1943. The column, alongside Northern Group Head Quarters had recently split up into smaller dispersal parties and were congregated close to the Irrawaddy River at a place called Myale. It is not known how Pte. Parkes became lost to his unit, or for how long he roamed alone in the jungle around the Irrawaddy. What is known, is that he was captured by the Japanese sometime afterwards and became a prisoner of war.

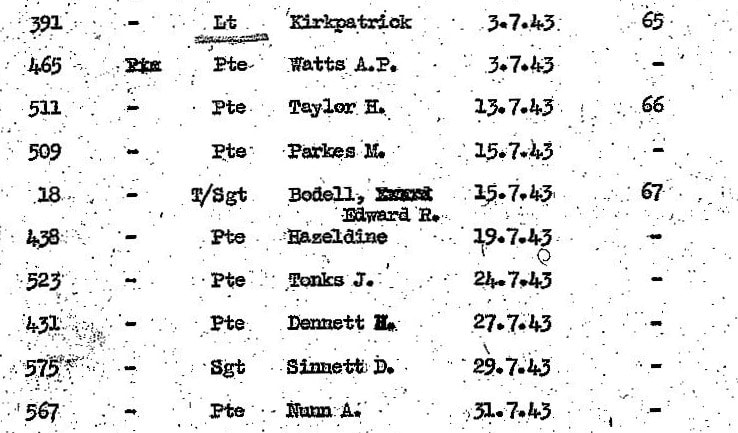

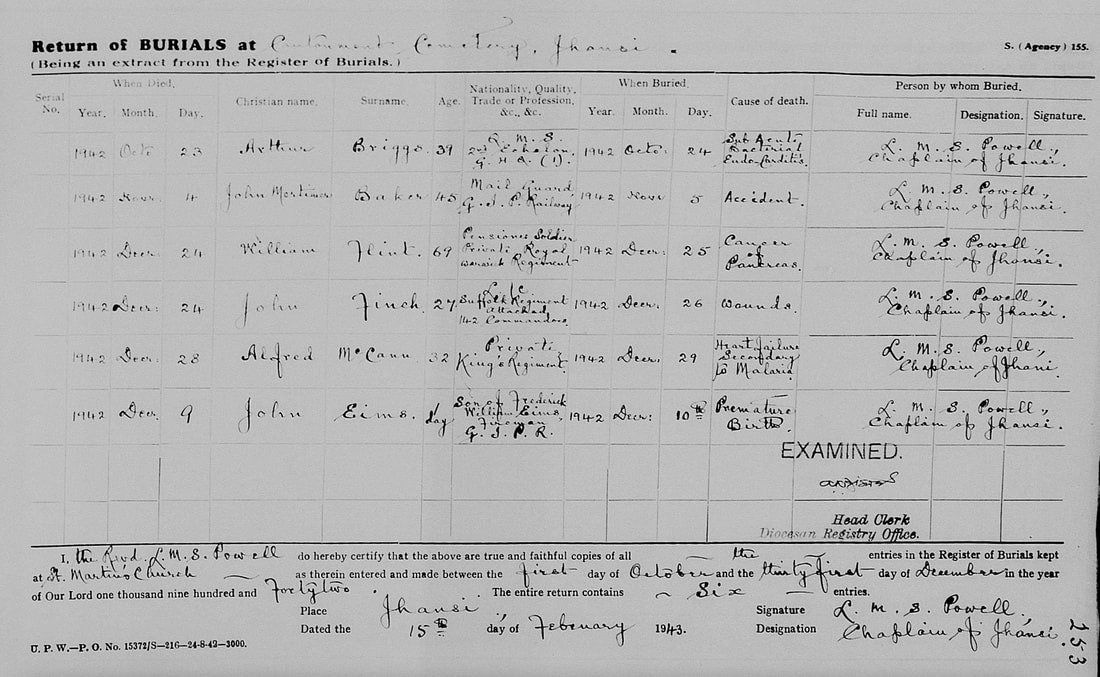

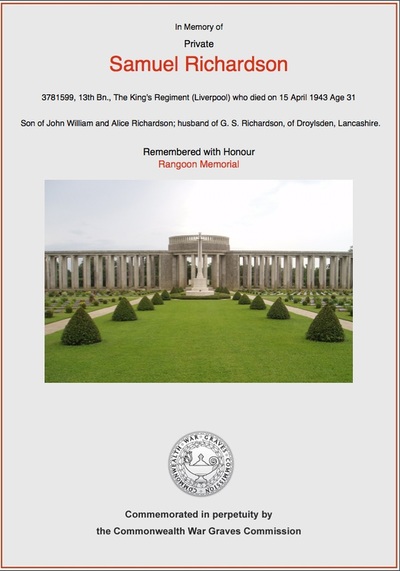

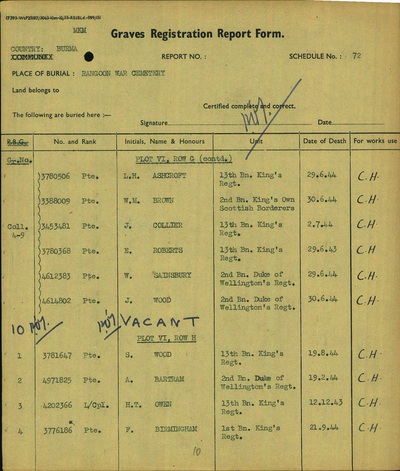

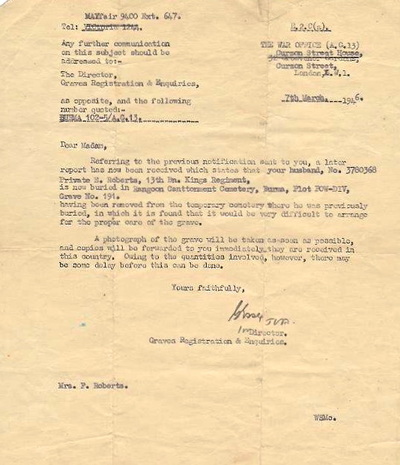

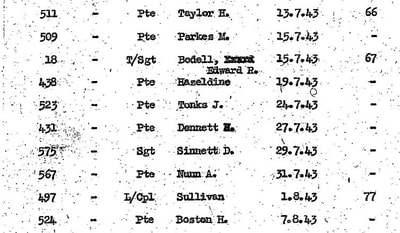

Eventually, all Chindit POWs were gathered together and sent down to Rangoon during the months of May and June 1943. It is not known when Martin Parkes arrived at Rangoon Central Jail, but sadly, we do know that he died in Block 6 of the prison on the 15th July. I would imagine that a combination of exhaustion and malnutrition suffered from the privations of the expedition and the fact that the Japanese did nothing to assist these men in any kind of recovery, were the main cause of his death at Rangoon. He had been allocated the POW number 509 in the jail and he was buried originally at the English Cantonment Cemetery in Grave no. 66, which shared with Pte. John Henry Taylor of No. 5 Column.

After the war was over, all burials at the English Cantonment Cemetery were moved across to the newly constructed Rangoon War Cemetery, located close to the city docks and this is where Martin Parkes lies today, alongside many of his Chindit comrades. To read more about the various Chindit related cemeteries and memorials, please click on the following link: Memorials and Cemeteries

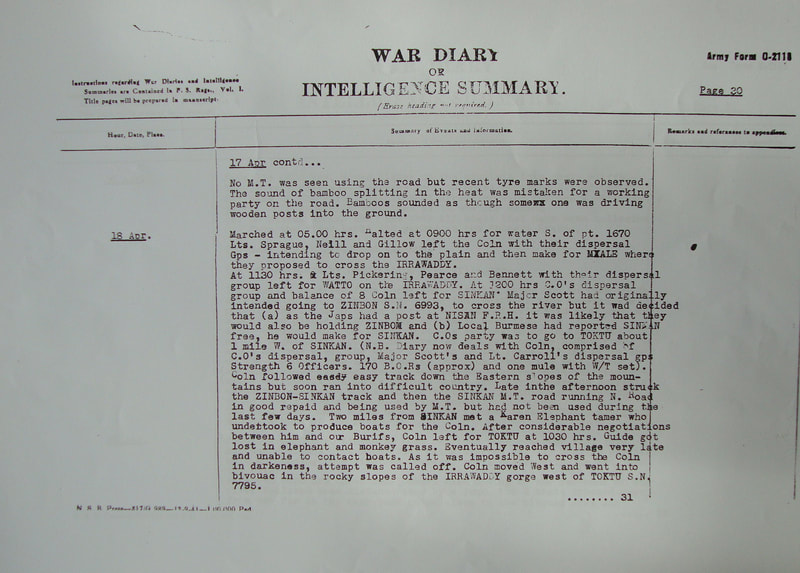

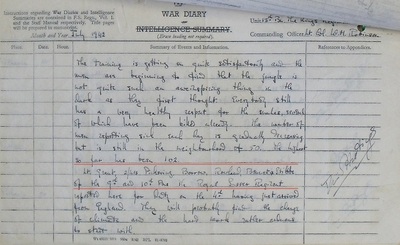

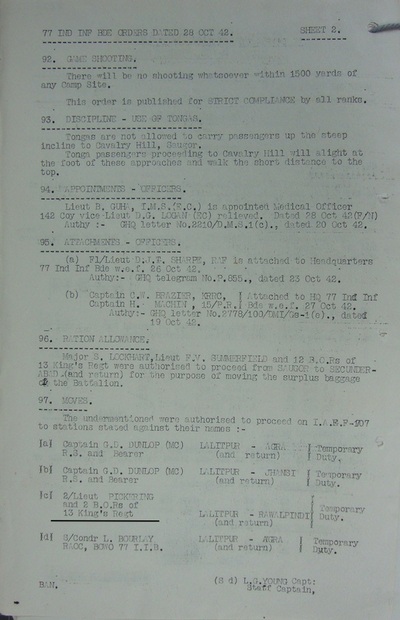

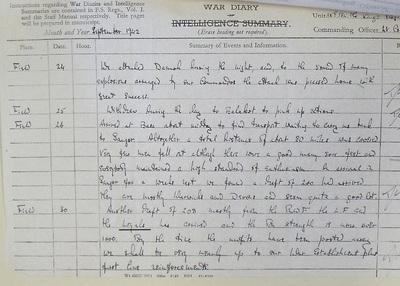

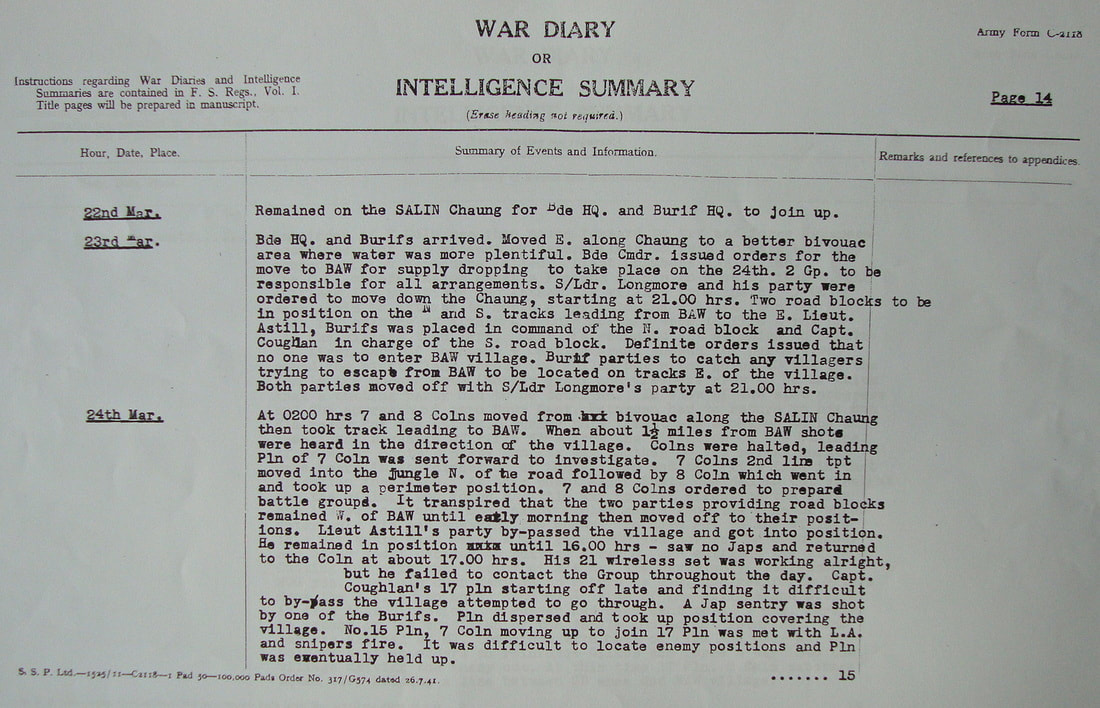

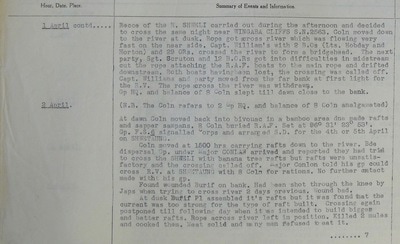

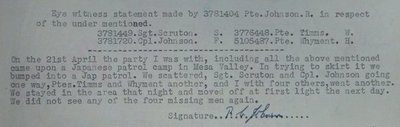

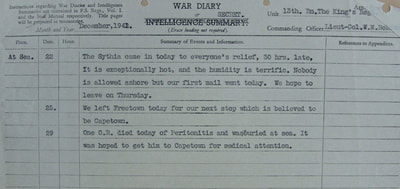

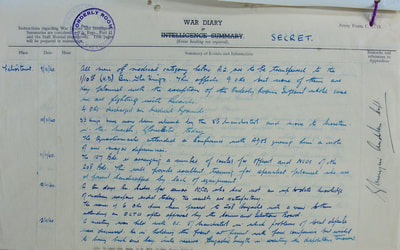

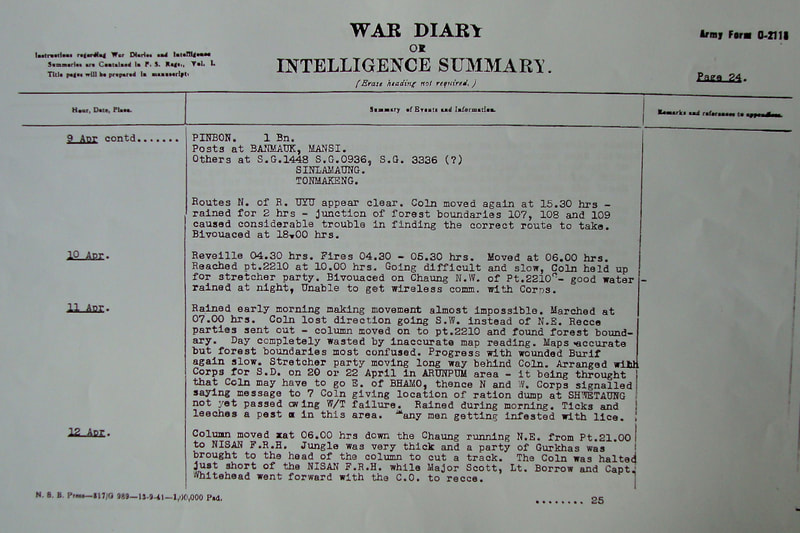

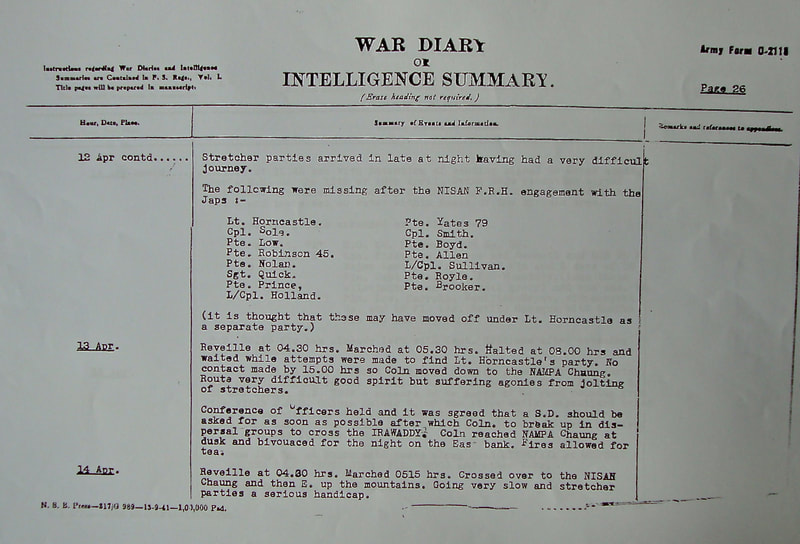

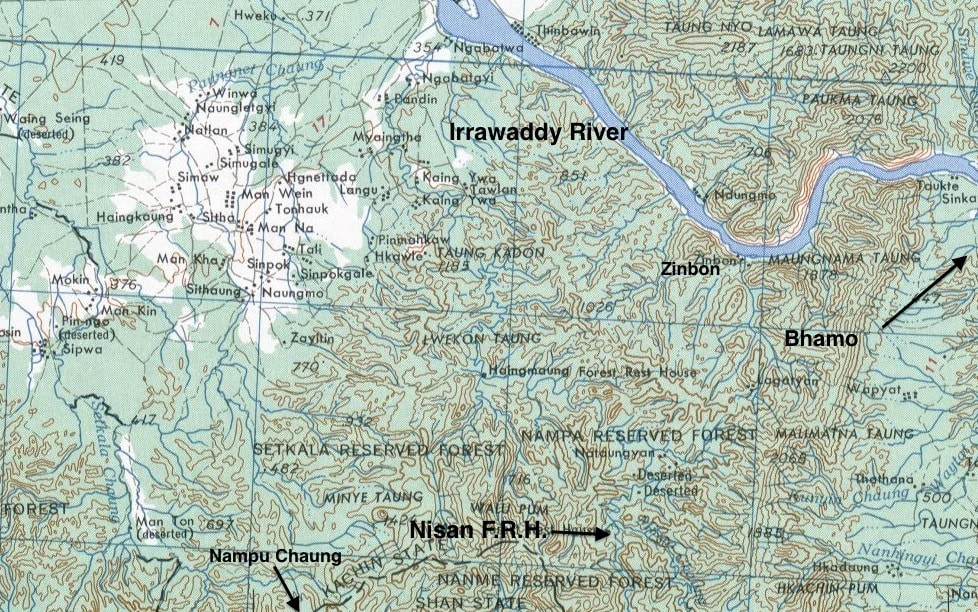

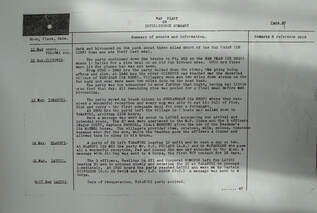

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story including an entry from the 8 Column war diary for the 18th April 1943. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Rank: Private

Service No: 6287635

Date of Death: 15/07/1943

Age: 22

Regiment/Service: 13th Bn. The King's Regiment (Liverpool)

Memorial: Rangoon War Cemetery, Grave 9.B.12.

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2261059/parkes,-martin/

Chindit Column: 8

Other details:

Martin Parkes was born in April 1912 and was the son of Martin (Senior) and Ellen Parkes from 76 Burlington Street in Liverpool. From his Army service number it can be ascertained that he had been originally posted to the Royal East Kent Regiment (known as the Buffs) during the earlier years of the war. By mid-1942 he had been sent overseas and transferred to the 13th Battalion of the King's (Liverpool) Regiment, who were training for the first Chindit expedition at Saugor in the Central Provinces of India. Pte. Parkes was allocated to No. 8 Column under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott.

According to the official missing in action listings for No. 8 Column, Pte. Parkes was reported as last seen on the 18th April 1943. The column, alongside Northern Group Head Quarters had recently split up into smaller dispersal parties and were congregated close to the Irrawaddy River at a place called Myale. It is not known how Pte. Parkes became lost to his unit, or for how long he roamed alone in the jungle around the Irrawaddy. What is known, is that he was captured by the Japanese sometime afterwards and became a prisoner of war.

Eventually, all Chindit POWs were gathered together and sent down to Rangoon during the months of May and June 1943. It is not known when Martin Parkes arrived at Rangoon Central Jail, but sadly, we do know that he died in Block 6 of the prison on the 15th July. I would imagine that a combination of exhaustion and malnutrition suffered from the privations of the expedition and the fact that the Japanese did nothing to assist these men in any kind of recovery, were the main cause of his death at Rangoon. He had been allocated the POW number 509 in the jail and he was buried originally at the English Cantonment Cemetery in Grave no. 66, which shared with Pte. John Henry Taylor of No. 5 Column.

After the war was over, all burials at the English Cantonment Cemetery were moved across to the newly constructed Rangoon War Cemetery, located close to the city docks and this is where Martin Parkes lies today, alongside many of his Chindit comrades. To read more about the various Chindit related cemeteries and memorials, please click on the following link: Memorials and Cemeteries

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story including an entry from the 8 Column war diary for the 18th April 1943. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

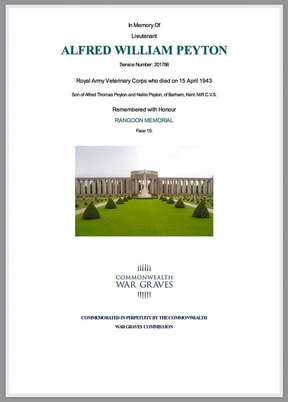

PEYTON, ALFRED WIILIAM

Rank: Lieutenant

Service No: 201786

Date of Death: 15/04/1943

Age: 25

Regiment/Service: Royal Army Veterinary Corps attached 13th Bn. The King's Regiment (Liverpool)

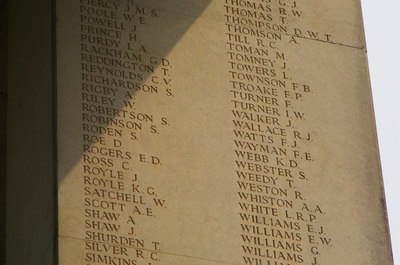

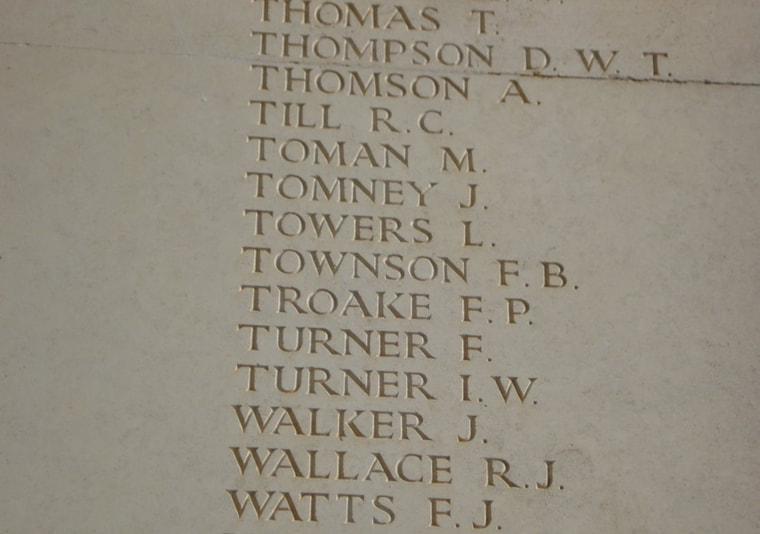

Memorial: Face 19 of the Rangoon Memorial

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2521442/alfred-william-peyton/

Chindit Column: Not known

Other details:

Alfred William Peyton was the son of Alfred and Nellie Peyton from Barham in Kent. He had graduated from the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (London) on the 17th December 1937 and began his carer as a vet in general practice. From the small amount of paperwork available in relation to his time with the Chindits, we do know that he posted to 77 Brigade Head Quarters in his capacity as a vet, but we cannot be certain that he went into Burma on Operation Longcloth with this section of the Brigade.

Alfred was lost on the 15th April 1943, during the early stages of 77 Brigade's return journey to India. The columns of Northern Section and Wingate's Brigade HQ had amassed on the banks of the Irrawaddy River at a place called Inywa on the 29th March with the view of crossing in one block. The Japanese appeared on the west bank and opened fire on the leading Chindit boats, resulting in the abandonment of the crossing. After this Wingate ordered the Brigade to break up into small dispersal parties and make their way back to Allied lines in this format. It is likely that Alfred was placed as an officer into one of these dispersal groups of around 25-30 personnel and began his journey back to India.

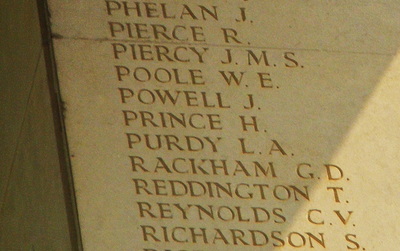

Sadly, nothing more is known about his time on Operation Longcloth or his death on the 15th April. After the war no grave was found for Lt. Peyton and for this reason he is remembered upon Face 19 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery. This monument is the centre-piece structure at the cemetery and displays the names of over 26,000 casualties from the Burma campaign who have no known grave. Alfred's estate was settled in May 1947, with all proceeds going to his father Alfred Peyton Senior, a builder by trade.

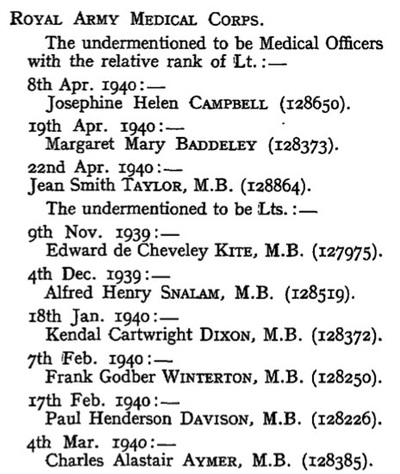

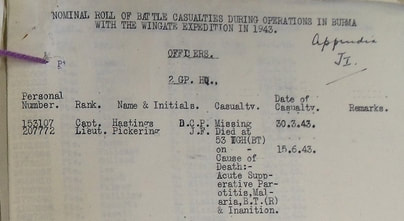

As a footnote to this story, the medals of Alfred Peyton were offered for sale on eBay in February 2017, selling in the end for just £110. Seen below is a part listing for officers lost on Operation Longcloth including Alfred Peyton. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

Rank: Lieutenant

Service No: 201786

Date of Death: 15/04/1943

Age: 25

Regiment/Service: Royal Army Veterinary Corps attached 13th Bn. The King's Regiment (Liverpool)

Memorial: Face 19 of the Rangoon Memorial

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2521442/alfred-william-peyton/

Chindit Column: Not known

Other details:

Alfred William Peyton was the son of Alfred and Nellie Peyton from Barham in Kent. He had graduated from the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (London) on the 17th December 1937 and began his carer as a vet in general practice. From the small amount of paperwork available in relation to his time with the Chindits, we do know that he posted to 77 Brigade Head Quarters in his capacity as a vet, but we cannot be certain that he went into Burma on Operation Longcloth with this section of the Brigade.

Alfred was lost on the 15th April 1943, during the early stages of 77 Brigade's return journey to India. The columns of Northern Section and Wingate's Brigade HQ had amassed on the banks of the Irrawaddy River at a place called Inywa on the 29th March with the view of crossing in one block. The Japanese appeared on the west bank and opened fire on the leading Chindit boats, resulting in the abandonment of the crossing. After this Wingate ordered the Brigade to break up into small dispersal parties and make their way back to Allied lines in this format. It is likely that Alfred was placed as an officer into one of these dispersal groups of around 25-30 personnel and began his journey back to India.

Sadly, nothing more is known about his time on Operation Longcloth or his death on the 15th April. After the war no grave was found for Lt. Peyton and for this reason he is remembered upon Face 19 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery. This monument is the centre-piece structure at the cemetery and displays the names of over 26,000 casualties from the Burma campaign who have no known grave. Alfred's estate was settled in May 1947, with all proceeds going to his father Alfred Peyton Senior, a builder by trade.

As a footnote to this story, the medals of Alfred Peyton were offered for sale on eBay in February 2017, selling in the end for just £110. Seen below is a part listing for officers lost on Operation Longcloth including Alfred Peyton. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

Casualty listings 13th King's Officers.

Casualty listings 13th King's Officers.

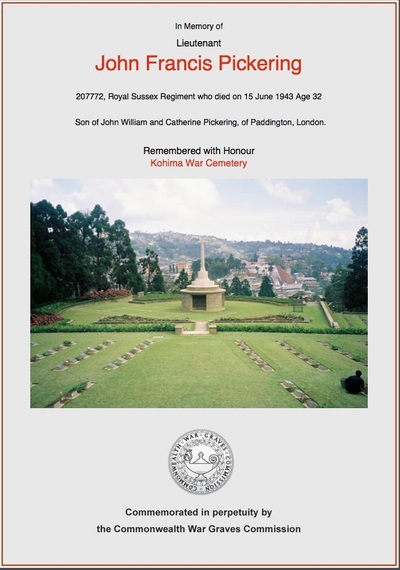

PICKERING, JOHN FRANCIS

Rank: Lieutenant

Service No: 207772

Date of Death: 15/06/1943

Age: 32

Regiment/Service: Royal Sussex/13th Bn. The King's Regiment (Liverpool)

Memorial: Kohima War Cemetery, Grave Reference 11.A.24.

CWGC link: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2601938/PICKERING,%20JOHN%20FRANCIS

Chindit Column: Northern Group Head Quarters.

Other details:

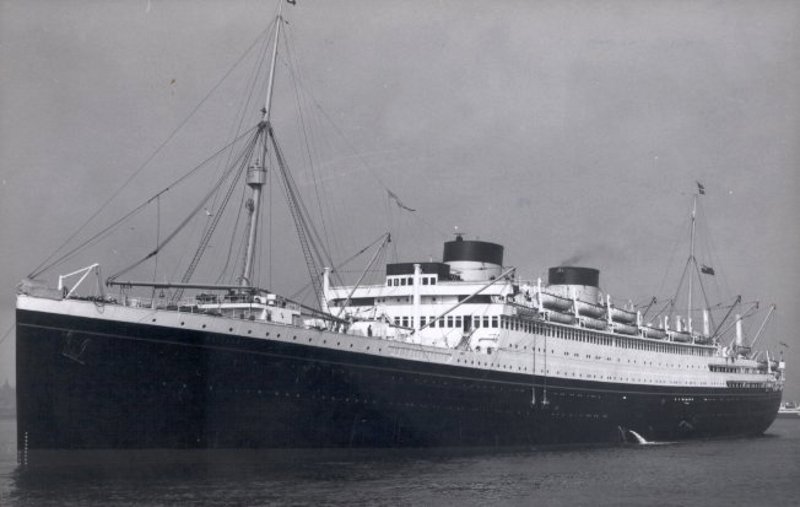

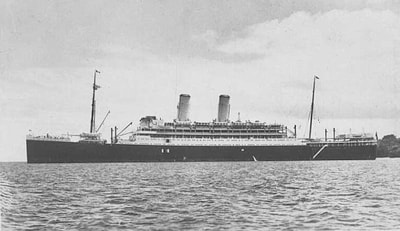

John Francis Pickering was the son of John William and Catherine Pickering, of Paddington, London. He had been brought up in the London borough and lived with his parents at 87 Nutbourne Street in Queens Park for most of the years leading up to the war. With the coming of war, John decided to enlist and was posted originally to the London Irish Rifles. Later, he was transferred to the Royal Sussex Regiment. In the spring of 1942 he found himself aboard the troopship 'Athlone Castle' with a small draft of fellow officers from the Royal Sussex Regiment and bound for the tropical shores of the sub-continent.

After disembarkation from the port of Bombay the young 2nd Lieutenants from the Sussex Regiment, namely, Pickering, Stibbe, Bennett, Rowlands and Borrow were taken up to the Chindit training area of Patharia in the Central Provinces of India. They arrived during the second week in July and were quickly assimilated into various Chindit units, with John being posted to the Northern Section's HQ.

Promotion to Lieutenant quickly followed for all the new recruits and John was then sent down to the Indian town of Rawalpindi for training courses related to the requirements and duties of a new special forces officer.

On the operation in Burma, Northern Group HQ commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel S.A. Cooke shadowed Brigadier Wingate's own Brigade HQ for the majority of the time. They also worked in close harmony with Column's 7 and 8. When the call to return to India was given in late March 1943, Cooke and Column 8 commander, Major Walter Purcell Scott decided they would attempt to head back together. Unfortunately, after several brushes with Japanese patrols over the next ten days or so, these plans had to be somewhat abandoned and the units were broken down into smaller dispersal parties.

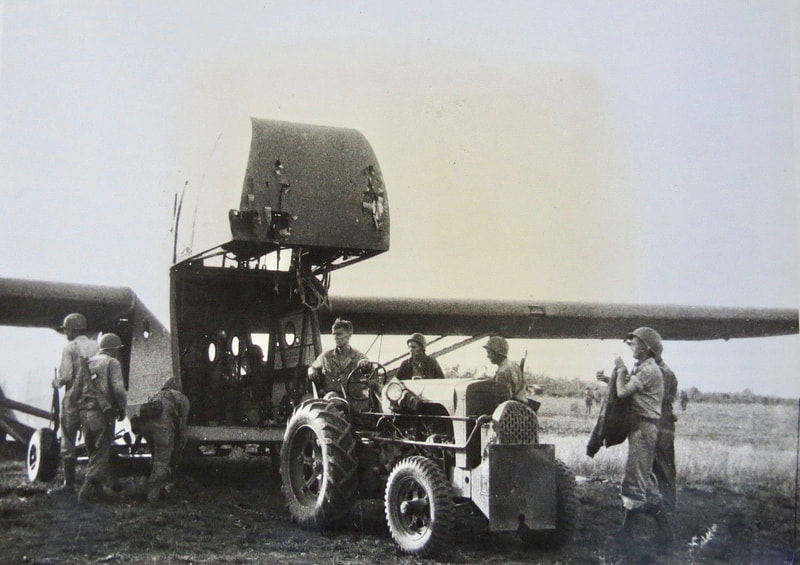

Amongst other duties within Northern Group HQ, Lieutenant Pickering had been given the task of preparing the supply drop locations in readiness for forthcoming air supply. This included choosing a suitable location, creating a sensible pathway for the supplies to land on and being responsible for illuminating the area in order for the aircraft to identify the supply drop zone or SD. In early April his HQ and Column 8 received one such supply drop from which the men not only restocked on much needed rations, but also took on new boots, uniforms, ammunition and most vitally of all, a new battery for the wireless set.

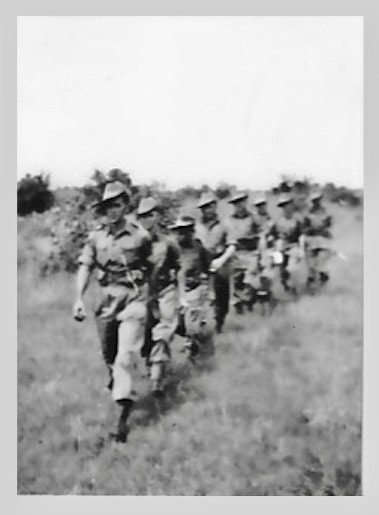

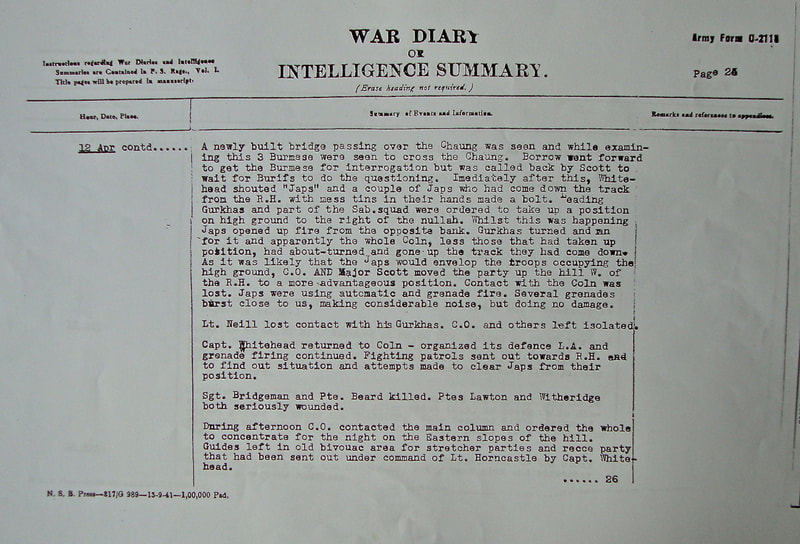

Approximately one week later, and after some minor engagements with the enemy, Scott and Colonel Cooke made the decision to break up their force into dispersal parties. From the book 'Wingate's Lost Brigade', author Phillip Chinnery describes events:

On 12th April, the front of the column was approaching a newly built bamboo bridge over a chaung when they bumped into a couple of Japs who turned and bolted back into the jungle. Intense firing broke out and Sergeant Bridgeman and Private Beard were killed, while Privates Lawton and Witheridge were both seriously wounded.

Most of the column turned around and disappeared along the track they had come down, leaving Major Scott and a small party isolated. It was not until the evening that the column reassembled and it was discovered that Lieutenant Horncastle and 14 others were missing. It was thought that they might have moved off as a separate party.

The column was up and moving at 0430 hours the next morning. The going was quite good but they now had three wounded on stretchers to carry with them. Major Scott and Lieutenant Colonel Cooke held an officers' conference and it was decided that they would request one last supply drop before breaking up into dispersal groups to cross the Irrawaddy.

The dispersal groups were arranged as follows:

Lieutenant Colonel Cooke, Lieutenant Borrow and half of Group Headquarters;

Lieutenants Pickering, Pearce and Bennett and the other half of Group Headquarters;

Major Scott with Column Headquarters, 17 Platoon and two sections of 16 Platoon;

Captain Whitehead and his Burma Rifles, less those already allocated to assist other dispersal groups, plus Flying Officer Wheatley and a section of 16 Platoon;

Lieutenants Carroll, Hamilton-Bryant with Support Group and 19 Platoon;

Lieutenants Neill and Sprague with the Gurkha Platoon and 142 Commando Platoon.

On 15th April, Captain Whitehead and his dispersal group, together with the stretcher party under Sergeant Parsons and the Medical Officer, Captain Heathcote, left the column. They planned to move to the east of Bhamo, thence north of Myitkyina to Fort Hertz. If this plan failed they would cross the Irrawaddy north of Bhamo and then go west towards the Chindwin. On the way they intended to leave the wounded at a friendly Kachin village.

Captain Whitehead's party had great difficulty getting down the eastern slopes of the mountains to the Bhamo Plain and the first villages they visited were deserted. The escort party under Lieutenant Hamilton-Bryant returned after a couple of days, anxious not to lose contact with the column. The decision of the Medical Officer to remain with Whitehead's group was rather controversial as it left the bulk of the column without a doctor. It was also a fateful decision as the party would be ambushed by the Japs on their journey out of Burma and many of the men were killed or taken prisoner.

Meanwhile the column received their supply drop on 17th April: four days' rations, corned beef and mutton, and another charged radio battery. The following day Lieutenants Neill, Sprague and Gillow left with their dispersal group, intending to drop on to the plain before heading for Myale where they proposed to cross the Irrawaddy.

Lieutenants Pickering, Pearce and Bennett and their group left for Watto on the Irrawaddy, and half an hour later Major Scott and the rest of the column continued on their journey to Sinkan. It had been decided that Lieutenant Colonel Cooke's dispersal group, together with that of Lieutenant Carroll, would remain with Scott for the time being, making a large party of six officers and 170 men, plus one mule with the wireless set.

Rank: Lieutenant

Service No: 207772

Date of Death: 15/06/1943

Age: 32

Regiment/Service: Royal Sussex/13th Bn. The King's Regiment (Liverpool)

Memorial: Kohima War Cemetery, Grave Reference 11.A.24.

CWGC link: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2601938/PICKERING,%20JOHN%20FRANCIS

Chindit Column: Northern Group Head Quarters.

Other details:

John Francis Pickering was the son of John William and Catherine Pickering, of Paddington, London. He had been brought up in the London borough and lived with his parents at 87 Nutbourne Street in Queens Park for most of the years leading up to the war. With the coming of war, John decided to enlist and was posted originally to the London Irish Rifles. Later, he was transferred to the Royal Sussex Regiment. In the spring of 1942 he found himself aboard the troopship 'Athlone Castle' with a small draft of fellow officers from the Royal Sussex Regiment and bound for the tropical shores of the sub-continent.

After disembarkation from the port of Bombay the young 2nd Lieutenants from the Sussex Regiment, namely, Pickering, Stibbe, Bennett, Rowlands and Borrow were taken up to the Chindit training area of Patharia in the Central Provinces of India. They arrived during the second week in July and were quickly assimilated into various Chindit units, with John being posted to the Northern Section's HQ.

Promotion to Lieutenant quickly followed for all the new recruits and John was then sent down to the Indian town of Rawalpindi for training courses related to the requirements and duties of a new special forces officer.

On the operation in Burma, Northern Group HQ commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel S.A. Cooke shadowed Brigadier Wingate's own Brigade HQ for the majority of the time. They also worked in close harmony with Column's 7 and 8. When the call to return to India was given in late March 1943, Cooke and Column 8 commander, Major Walter Purcell Scott decided they would attempt to head back together. Unfortunately, after several brushes with Japanese patrols over the next ten days or so, these plans had to be somewhat abandoned and the units were broken down into smaller dispersal parties.

Amongst other duties within Northern Group HQ, Lieutenant Pickering had been given the task of preparing the supply drop locations in readiness for forthcoming air supply. This included choosing a suitable location, creating a sensible pathway for the supplies to land on and being responsible for illuminating the area in order for the aircraft to identify the supply drop zone or SD. In early April his HQ and Column 8 received one such supply drop from which the men not only restocked on much needed rations, but also took on new boots, uniforms, ammunition and most vitally of all, a new battery for the wireless set.

Approximately one week later, and after some minor engagements with the enemy, Scott and Colonel Cooke made the decision to break up their force into dispersal parties. From the book 'Wingate's Lost Brigade', author Phillip Chinnery describes events:

On 12th April, the front of the column was approaching a newly built bamboo bridge over a chaung when they bumped into a couple of Japs who turned and bolted back into the jungle. Intense firing broke out and Sergeant Bridgeman and Private Beard were killed, while Privates Lawton and Witheridge were both seriously wounded.

Most of the column turned around and disappeared along the track they had come down, leaving Major Scott and a small party isolated. It was not until the evening that the column reassembled and it was discovered that Lieutenant Horncastle and 14 others were missing. It was thought that they might have moved off as a separate party.

The column was up and moving at 0430 hours the next morning. The going was quite good but they now had three wounded on stretchers to carry with them. Major Scott and Lieutenant Colonel Cooke held an officers' conference and it was decided that they would request one last supply drop before breaking up into dispersal groups to cross the Irrawaddy.

The dispersal groups were arranged as follows:

Lieutenant Colonel Cooke, Lieutenant Borrow and half of Group Headquarters;

Lieutenants Pickering, Pearce and Bennett and the other half of Group Headquarters;

Major Scott with Column Headquarters, 17 Platoon and two sections of 16 Platoon;

Captain Whitehead and his Burma Rifles, less those already allocated to assist other dispersal groups, plus Flying Officer Wheatley and a section of 16 Platoon;

Lieutenants Carroll, Hamilton-Bryant with Support Group and 19 Platoon;

Lieutenants Neill and Sprague with the Gurkha Platoon and 142 Commando Platoon.

On 15th April, Captain Whitehead and his dispersal group, together with the stretcher party under Sergeant Parsons and the Medical Officer, Captain Heathcote, left the column. They planned to move to the east of Bhamo, thence north of Myitkyina to Fort Hertz. If this plan failed they would cross the Irrawaddy north of Bhamo and then go west towards the Chindwin. On the way they intended to leave the wounded at a friendly Kachin village.

Captain Whitehead's party had great difficulty getting down the eastern slopes of the mountains to the Bhamo Plain and the first villages they visited were deserted. The escort party under Lieutenant Hamilton-Bryant returned after a couple of days, anxious not to lose contact with the column. The decision of the Medical Officer to remain with Whitehead's group was rather controversial as it left the bulk of the column without a doctor. It was also a fateful decision as the party would be ambushed by the Japs on their journey out of Burma and many of the men were killed or taken prisoner.

Meanwhile the column received their supply drop on 17th April: four days' rations, corned beef and mutton, and another charged radio battery. The following day Lieutenants Neill, Sprague and Gillow left with their dispersal group, intending to drop on to the plain before heading for Myale where they proposed to cross the Irrawaddy.

Lieutenants Pickering, Pearce and Bennett and their group left for Watto on the Irrawaddy, and half an hour later Major Scott and the rest of the column continued on their journey to Sinkan. It had been decided that Lieutenant Colonel Cooke's dispersal group, together with that of Lieutenant Carroll, would remain with Scott for the time being, making a large party of six officers and 170 men, plus one mule with the wireless set.

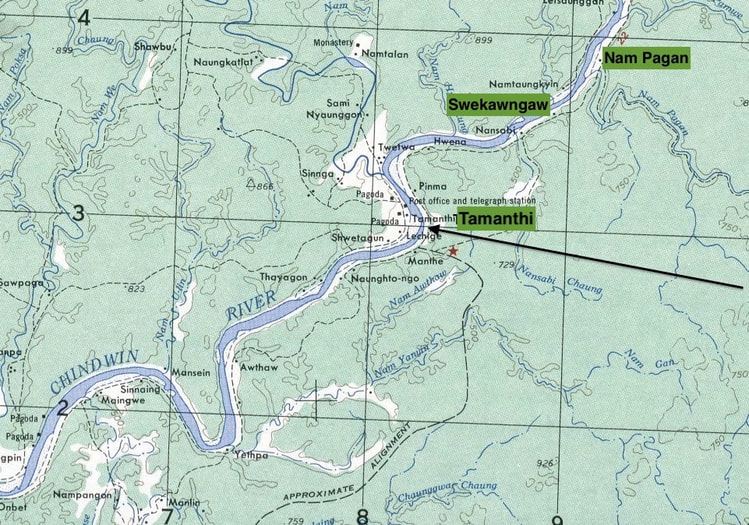

John Pickering must have gained some comfort to be paired with his former Royal Sussex comrade, Peter Bennett, in the dispersal group which would be led by Lieutenant H.S. Pearce. Not much has been written about the fate of this group in the books and diaries I have read, but, fortunately one member of the unit did put his experiences down on paper.

Lance Corporal George Bell throws some light on the story:

"After taking another supply drop, the decision was made to split up into smaller dispersal parties. Some headed for China, while others stayed together and marched due west. Our party under Lieutenant Pearce, about fifty strong, went north-north-west. Before splitting up we shook hands with all our pals in the other groups, several of them we would never see again. Our party included three officers and two Burmese who were in the Burma Rifles and could speak both English and Burmese. They saved our lives, as they were able to enter villages and obtain information about the whereabouts of the Japs. Apart from the one occasion when they got drunk as newts in one village on rice wine.

After leaving the other groups we made for a small village on the Irrawaddy, only to find as we arrived there that the village had been moved to the other bank a few years before. It was then that we realised that our maps had been drawn up in 1912 and were extremely out of date. We made off for another village further towards the north, but got bogged down in thick jungle and so decided to halt and sleep for a few hours. This turned out to be a stroke of good luck, as it transpired that a Jap patrol had spent the night in the village and had only just moved out. From that moment on I always felt that someone above was looking out for us.

As soon as it was dark we started to cross over in a boat with a villager rowing, the water came right up to the top of the sides, I couldn't swim and so was pleased to reach the other side still afloat. Throughout the night the boat crossed and re-crossed the river until everyone was over. By that time we had no way of contacting our air base and had to rely on local villages for food, boiled rice with no salt for breakfast, lunch and dinner! We had also become lousy and our clothes were disgusting. Leeches became a real problem, they got everywhere and I mean everywhere. We were told to use a lighted cigarette to burn them off, but this advice presumed we had cigarettes, which by then we did not. At one stage the heavy smokers amongst our group bought local tobacco from a village and used one of the lads bible for roll-up papers.

We marched sometimes 20 miles in a day, re-crossing the railway and two more minor rivers. One day we came across a Burmese man who could speak English, his story did not ring true to us and so we kept him with us under guard. After collecting more rice in the next village the headman warned us that this man had recently been in the company of a Jap patrol. It was decide that it was too dangerous to let him go and that he should be shot. My section took him away from the main group and one of the Burma Rifle soldiers shot him through the head. This left us with the feeling of being judge, jury and executioner.

We slogged on for a few more days, by which time our food supplies had completely run out. I brewed up with a tea bag that must have been used at least twenty times before. Around midday we were walking along a dried-up river bed when we saw some parachutes caught up in a group of trees. We approached them carefully concerned it might be a Jap ambush or booby trap, but it was a definite ration dropping, presumably for another of our parties. The packs gave us eight days rations per man, exactly eight days later we were in a small village when a British plane came over and spotted us on the ground. They dropped a message canister asking if we needed supplies, we answered them using cut parachute strips to mark out our numbers and needs. We waited for almost two days hoping they would return, but reluctantly we moved on, worried about the dangers of staying put in one place for too long.

Not long after that incident two of our lads whose feet were in an awful state needed time to rest and bathe their feet in a stream. The order was given to move off, but the two men said they wanted to remain for a short while longer and would attempt to catch us up later. They never returned to the main group and we heard later that they had been killed by the Japanese.

We pushed on again and eventually reached the Chindwin River. Some Burmese boatmen ferried us across near Tamanthi which was occupied by the enemy at that time. We marched quickly westward and came to an Assam Rifles outpost. Here we shaved off our beards which showed us how thin we had become, losing two or three stones in weight. After a few days rest in the camp we set off again, this time knowing we were safe.

Remarkably this seemed to make matters worse for some of the men. Our incentive to keep going was no longer there, physiologically we were in a poorer state and many of the lads health began to go down hill. Eventually we hit the road and were transported to the hospital at Kohima. It was here that Lieutenant Pickering and Private Sullivan sadly died, after all we had been through it was heartbreaking."

Lance Corporal George Bell throws some light on the story:

"After taking another supply drop, the decision was made to split up into smaller dispersal parties. Some headed for China, while others stayed together and marched due west. Our party under Lieutenant Pearce, about fifty strong, went north-north-west. Before splitting up we shook hands with all our pals in the other groups, several of them we would never see again. Our party included three officers and two Burmese who were in the Burma Rifles and could speak both English and Burmese. They saved our lives, as they were able to enter villages and obtain information about the whereabouts of the Japs. Apart from the one occasion when they got drunk as newts in one village on rice wine.

After leaving the other groups we made for a small village on the Irrawaddy, only to find as we arrived there that the village had been moved to the other bank a few years before. It was then that we realised that our maps had been drawn up in 1912 and were extremely out of date. We made off for another village further towards the north, but got bogged down in thick jungle and so decided to halt and sleep for a few hours. This turned out to be a stroke of good luck, as it transpired that a Jap patrol had spent the night in the village and had only just moved out. From that moment on I always felt that someone above was looking out for us.

As soon as it was dark we started to cross over in a boat with a villager rowing, the water came right up to the top of the sides, I couldn't swim and so was pleased to reach the other side still afloat. Throughout the night the boat crossed and re-crossed the river until everyone was over. By that time we had no way of contacting our air base and had to rely on local villages for food, boiled rice with no salt for breakfast, lunch and dinner! We had also become lousy and our clothes were disgusting. Leeches became a real problem, they got everywhere and I mean everywhere. We were told to use a lighted cigarette to burn them off, but this advice presumed we had cigarettes, which by then we did not. At one stage the heavy smokers amongst our group bought local tobacco from a village and used one of the lads bible for roll-up papers.

We marched sometimes 20 miles in a day, re-crossing the railway and two more minor rivers. One day we came across a Burmese man who could speak English, his story did not ring true to us and so we kept him with us under guard. After collecting more rice in the next village the headman warned us that this man had recently been in the company of a Jap patrol. It was decide that it was too dangerous to let him go and that he should be shot. My section took him away from the main group and one of the Burma Rifle soldiers shot him through the head. This left us with the feeling of being judge, jury and executioner.

We slogged on for a few more days, by which time our food supplies had completely run out. I brewed up with a tea bag that must have been used at least twenty times before. Around midday we were walking along a dried-up river bed when we saw some parachutes caught up in a group of trees. We approached them carefully concerned it might be a Jap ambush or booby trap, but it was a definite ration dropping, presumably for another of our parties. The packs gave us eight days rations per man, exactly eight days later we were in a small village when a British plane came over and spotted us on the ground. They dropped a message canister asking if we needed supplies, we answered them using cut parachute strips to mark out our numbers and needs. We waited for almost two days hoping they would return, but reluctantly we moved on, worried about the dangers of staying put in one place for too long.

Not long after that incident two of our lads whose feet were in an awful state needed time to rest and bathe their feet in a stream. The order was given to move off, but the two men said they wanted to remain for a short while longer and would attempt to catch us up later. They never returned to the main group and we heard later that they had been killed by the Japanese.

We pushed on again and eventually reached the Chindwin River. Some Burmese boatmen ferried us across near Tamanthi which was occupied by the enemy at that time. We marched quickly westward and came to an Assam Rifles outpost. Here we shaved off our beards which showed us how thin we had become, losing two or three stones in weight. After a few days rest in the camp we set off again, this time knowing we were safe.

Remarkably this seemed to make matters worse for some of the men. Our incentive to keep going was no longer there, physiologically we were in a poorer state and many of the lads health began to go down hill. Eventually we hit the road and were transported to the hospital at Kohima. It was here that Lieutenant Pickering and Private Sullivan sadly died, after all we had been through it was heartbreaking."

John Francis Pickering died on the 15th June 1943 in the Indian General Hospital at Kohima, on the informational listing for Longcloth casualties this is noted as 53 I.G.H. followed by the cause of death, in John's case; Acute Suppurative Parotitis, Malaria, B.T. (R) and Inanition.

Inanition is the exhausted condition that results from the lack of regular food and water, which can be no great surprise considering the privations most of the Chindits experienced that year.

Suppurative parotitis is an acute infection of the parotid gland which can be caused by a variety of bacteria and viruses. Acute bacterial suppurative parotitis is most commonly caused by severe debilitation, dehydration, and poor oral hygiene. The parotid glands are located on the sides of the face, anterior to the external auditory canal, superior to the angle of the mandible, and inferior to the zygomatic arch. The condition can be further aggravated by the loss of saliva production in the mouth, a symptom common during the dehydration process.

Once again we seem to witness a man's life or death struggle to survive the terrors and hardship of the first Chindit expedition and with a determination to escape Burma in one piece, only for his body to give out once he relaxes in the apparent safety of an Allied Hospital bed.

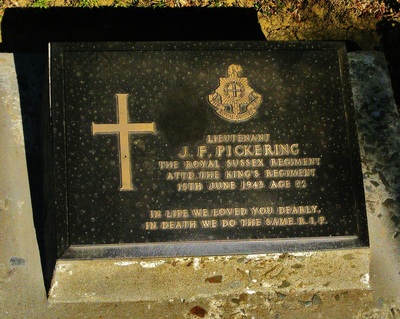

Lieutenant Pickering was buried at Kohima War Cemetery, he was joined there by Pte. George Sullivan a former member of Column 8 on Operation Longcloth, who had also died whilst in Kohima Hospital. George was suffering from exhaustion and fatigue like most others, but his cause of death was recorded as 'uraemic infection and kidney failure.'

In his official Army Will, John Pickering had decided to leave all his estate and personal effects to 'spinster', Kathleen Pickering, presumably his paternal Aunt.

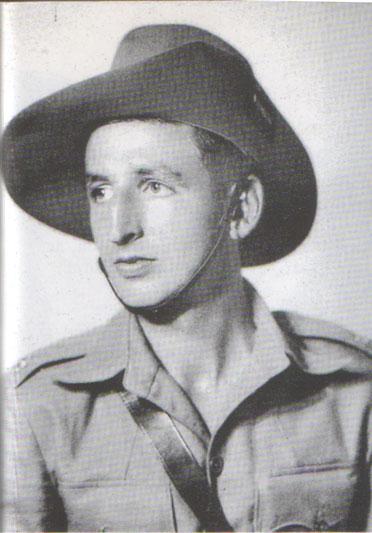

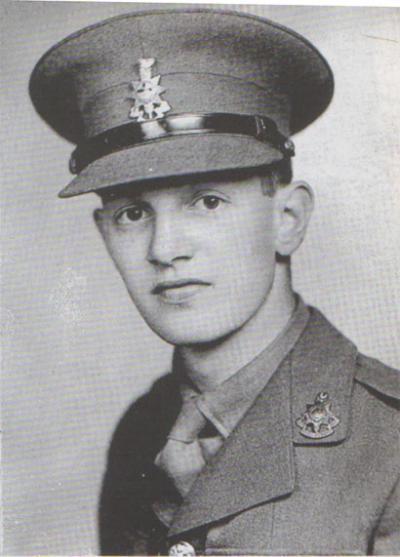

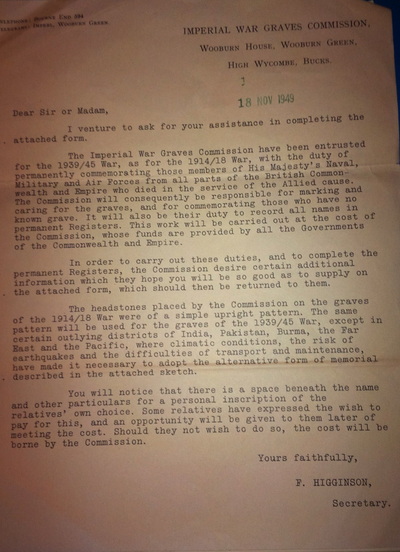

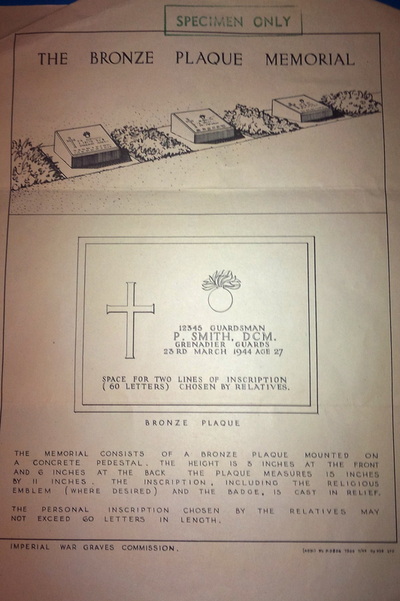

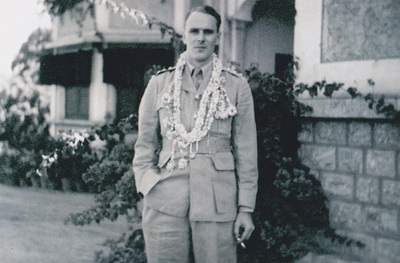

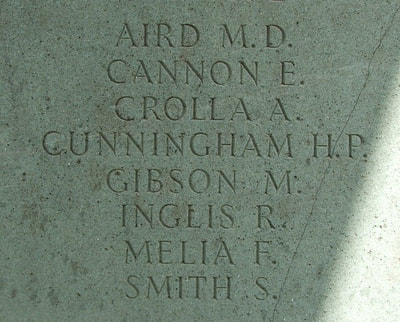

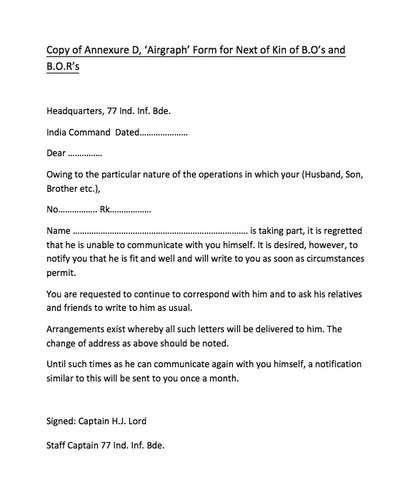

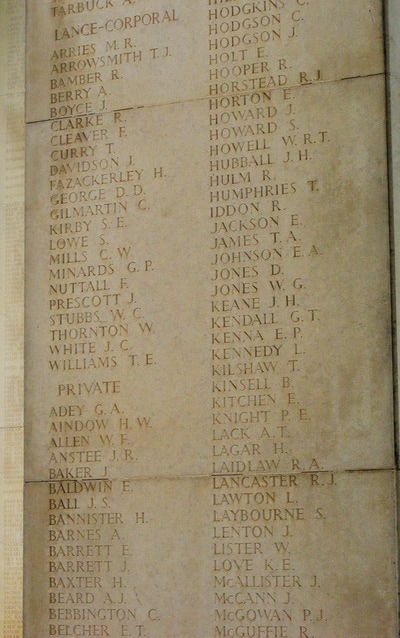

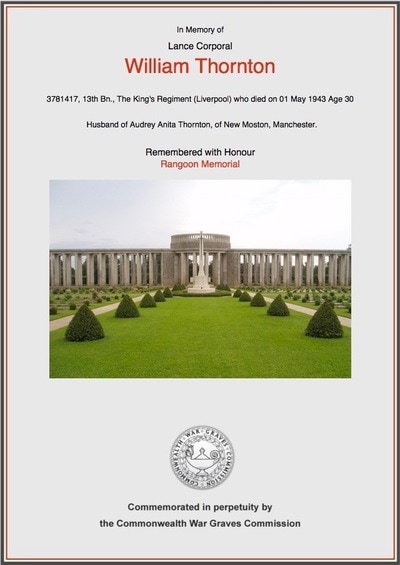

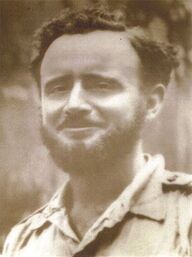

Seen below are a selection of images in relation to John Francis Pickering and his story, including some photographs of the men he served with during his time in India and Burma. There is also an official communique from the CWCG to all families of casualties from the Burma campaign, explaining why the style of memorial plaque was chosen. Please click on each image to bring them forward.

Inanition is the exhausted condition that results from the lack of regular food and water, which can be no great surprise considering the privations most of the Chindits experienced that year.

Suppurative parotitis is an acute infection of the parotid gland which can be caused by a variety of bacteria and viruses. Acute bacterial suppurative parotitis is most commonly caused by severe debilitation, dehydration, and poor oral hygiene. The parotid glands are located on the sides of the face, anterior to the external auditory canal, superior to the angle of the mandible, and inferior to the zygomatic arch. The condition can be further aggravated by the loss of saliva production in the mouth, a symptom common during the dehydration process.

Once again we seem to witness a man's life or death struggle to survive the terrors and hardship of the first Chindit expedition and with a determination to escape Burma in one piece, only for his body to give out once he relaxes in the apparent safety of an Allied Hospital bed.

Lieutenant Pickering was buried at Kohima War Cemetery, he was joined there by Pte. George Sullivan a former member of Column 8 on Operation Longcloth, who had also died whilst in Kohima Hospital. George was suffering from exhaustion and fatigue like most others, but his cause of death was recorded as 'uraemic infection and kidney failure.'

In his official Army Will, John Pickering had decided to leave all his estate and personal effects to 'spinster', Kathleen Pickering, presumably his paternal Aunt.

Seen below are a selection of images in relation to John Francis Pickering and his story, including some photographs of the men he served with during his time in India and Burma. There is also an official communique from the CWCG to all families of casualties from the Burma campaign, explaining why the style of memorial plaque was chosen. Please click on each image to bring them forward.

Copyright © Steve Fogden April 2014. With thanks to Phil Chinnery.

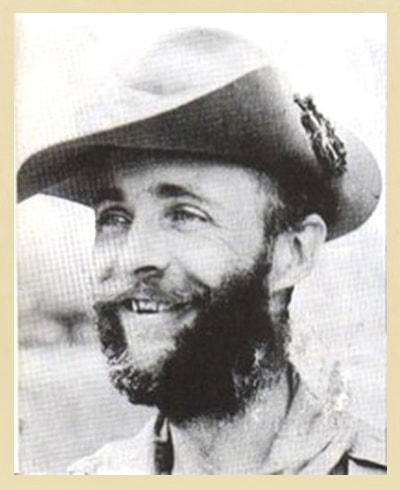

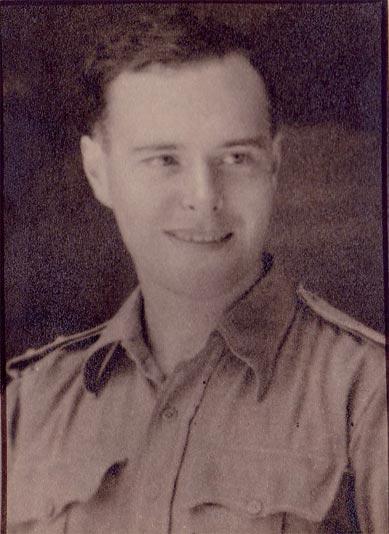

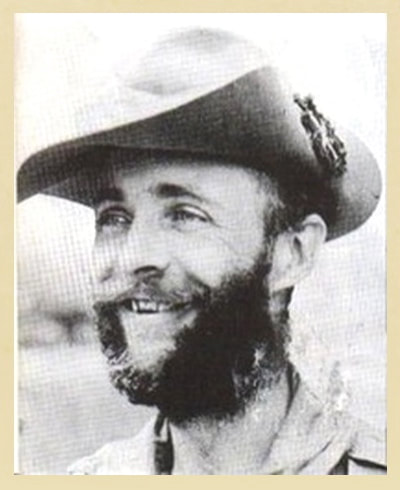

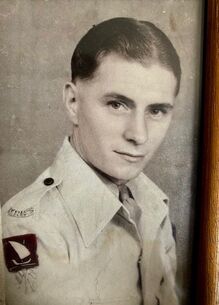

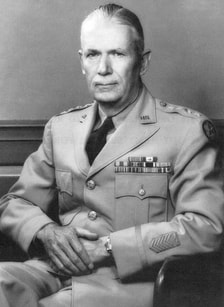

Captain John Swafer Pickering MC

Captain John Swafer Pickering MC

PICKERING, JOHN SWAFER

Rank: Captain

Service No: 135798

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Chindit Column: 7

Other details:

John Swafer Pickering, known as Jacksie to his Army comrades, joined the ranks of the 13th King's as a 2nd Lieutenant, on the 4th September 1940 whilst the battalion were stationed at Glasgow. He soon settled in to his new surroundings and was steadily promoted within the King's, eventually reaching the rank of Captain in late 1941, as the battalion were readying themselves for overseas duties.

John travelled with the King's aboard the troopship Oronsay, which took the unit to South Africa, arriving at Durban in early January 1942 for a five-day stop-over, before the battalion were transferred to another ship (RMS Andes) for the final leg of their voyage to India.

Captain Pickering was posted as second in command to Chindit Column No. 7, under the overall leadership of Major Kenneth Gilkes, formerly of the North Staffordshire Regiment. Towards the end of Operation Longcloth it was decided by Gilkes to take his column out of Burma via the Chinese borders. Captain Pickering took on the command of the column in early May 1943, as it marched northeast into Yunnan Province and was at the head of the column as it entered into Paoshan on the 4th June. Meanwhile, Major Gilkes and a small party of other officers had pushed on ahead to make contact with Chinese troops and arrange food and lodging for the rest of the column.

To read more about No. 7 Column's experiences in 1943, please click on the following link: Leslie Randle Cottrell

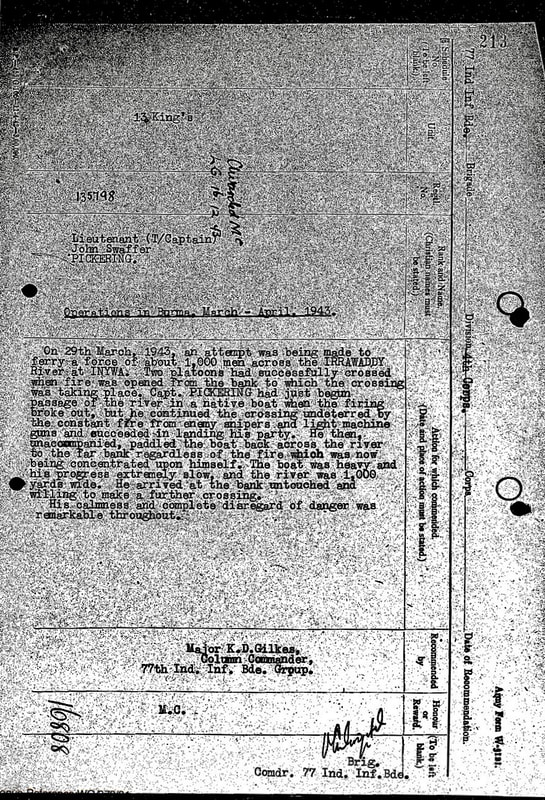

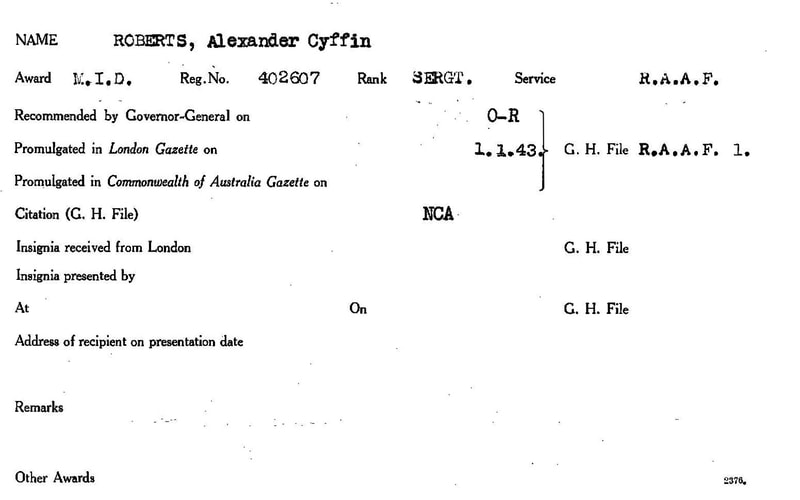

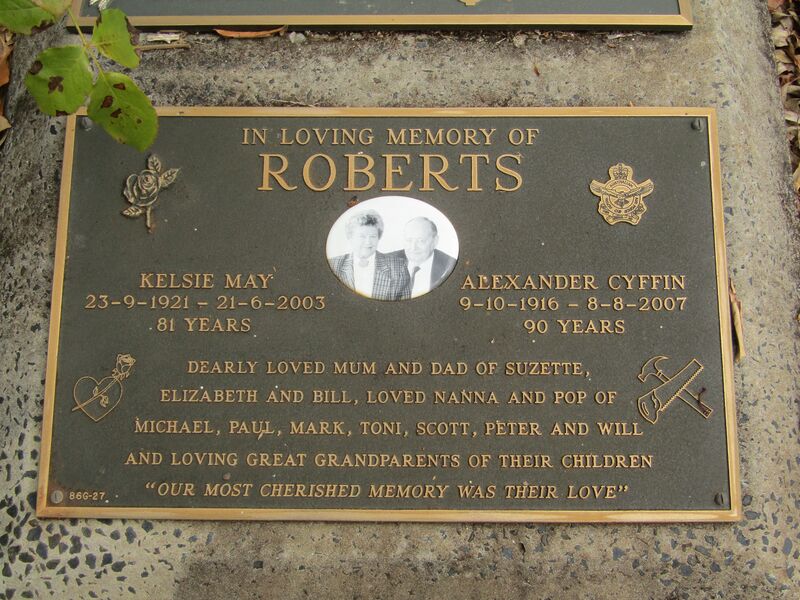

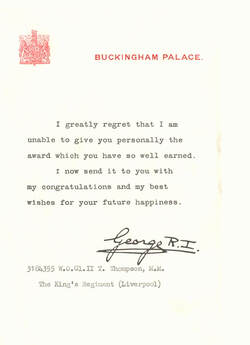

For his efforts on the first Wingate expedition, John Pickering was awarded the Military Cross:

Rank and Name: Captain 135798 John Swaffer Pickering

Action for which recommended:

Operations in Burma, March - April 1943

On 29th March 1943 an attempt was being made to ferry a force of about 1,000 men across the Irrawaddy River at Inywa. Two platoons had successfully crossed when fire was opened from the bank to which the crossing was taking place. Captain Pickering had just begun passage of the river in a native boat when the firing broke out, but he continued the crossing undeterred by the constant fire from enemy snipers and light machine guns and succeeded in landing his party.

He then, unaccompanied, paddled the boat back across the river to the far bank regardless of the fire which was now being concentrated upon himself. The boat was heavy and his progress extremely slow, and the river was 1,000 yards wide. He arrived at the bank untouched and willing to make a further crossing. His coolness and complete disregard of danger was remarkable throughout.

Award: Military Cross

Recommended By: Major K.D. Gilkes, Column Commander

77th Indian Infantry Brigade Group

Signed Off By: Brigadier O.C. Wingate, Commander, 77 Indian Infantry Brigade.

(London Gazette 16.12.1943).

News of John Pickering's award reached home immediately after the announcement in the London Gazette. In the Birmingham Mail the following day (17th December 1943) came the following short report:

MC medal for Birmingham Officer

The London Gazette announces the award of the Military Cross, to Birmingham born Captain J.S. Pickering of the King's Regiment. This is in recognition of his gallant and distinguished service during operations in Burma from February-May 1943. Captain Arthur Hill of Rugeley (Lincolnshire Regiment) has received the same award.

Rank: Captain

Service No: 135798

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Chindit Column: 7

Other details:

John Swafer Pickering, known as Jacksie to his Army comrades, joined the ranks of the 13th King's as a 2nd Lieutenant, on the 4th September 1940 whilst the battalion were stationed at Glasgow. He soon settled in to his new surroundings and was steadily promoted within the King's, eventually reaching the rank of Captain in late 1941, as the battalion were readying themselves for overseas duties.

John travelled with the King's aboard the troopship Oronsay, which took the unit to South Africa, arriving at Durban in early January 1942 for a five-day stop-over, before the battalion were transferred to another ship (RMS Andes) for the final leg of their voyage to India.

Captain Pickering was posted as second in command to Chindit Column No. 7, under the overall leadership of Major Kenneth Gilkes, formerly of the North Staffordshire Regiment. Towards the end of Operation Longcloth it was decided by Gilkes to take his column out of Burma via the Chinese borders. Captain Pickering took on the command of the column in early May 1943, as it marched northeast into Yunnan Province and was at the head of the column as it entered into Paoshan on the 4th June. Meanwhile, Major Gilkes and a small party of other officers had pushed on ahead to make contact with Chinese troops and arrange food and lodging for the rest of the column.

To read more about No. 7 Column's experiences in 1943, please click on the following link: Leslie Randle Cottrell

For his efforts on the first Wingate expedition, John Pickering was awarded the Military Cross:

Rank and Name: Captain 135798 John Swaffer Pickering

Action for which recommended:

Operations in Burma, March - April 1943

On 29th March 1943 an attempt was being made to ferry a force of about 1,000 men across the Irrawaddy River at Inywa. Two platoons had successfully crossed when fire was opened from the bank to which the crossing was taking place. Captain Pickering had just begun passage of the river in a native boat when the firing broke out, but he continued the crossing undeterred by the constant fire from enemy snipers and light machine guns and succeeded in landing his party.

He then, unaccompanied, paddled the boat back across the river to the far bank regardless of the fire which was now being concentrated upon himself. The boat was heavy and his progress extremely slow, and the river was 1,000 yards wide. He arrived at the bank untouched and willing to make a further crossing. His coolness and complete disregard of danger was remarkable throughout.

Award: Military Cross

Recommended By: Major K.D. Gilkes, Column Commander

77th Indian Infantry Brigade Group

Signed Off By: Brigadier O.C. Wingate, Commander, 77 Indian Infantry Brigade.

(London Gazette 16.12.1943).

News of John Pickering's award reached home immediately after the announcement in the London Gazette. In the Birmingham Mail the following day (17th December 1943) came the following short report:

MC medal for Birmingham Officer

The London Gazette announces the award of the Military Cross, to Birmingham born Captain J.S. Pickering of the King's Regiment. This is in recognition of his gallant and distinguished service during operations in Burma from February-May 1943. Captain Arthur Hill of Rugeley (Lincolnshire Regiment) has received the same award.

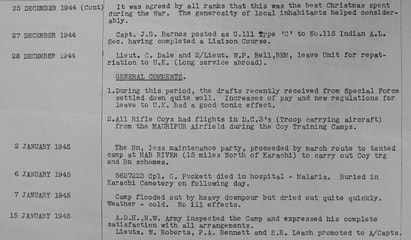

After Operation Longcloth concluded in June 1943, the surviving members of 13th King's were sent to various hospitals in India followed by a long period of rest and recuperation. The battalion was eventually reorganised and stationed for the rest of it's time in India, at the Napier Barracks in Karachi. As one of the more senior officers, Captain Pickering was tasked with various administrational duties. This included having to write to the families of the many soldiers who had not returned from Burma after the first Wingate expedition. Shown below is a letter (dated 2nd September 1943) written by Pickering to the mother of Lieutenant Thomas Arthur Stock, an officer serving with No. 7 Column who had been captured by the Japanese shortly after the aborted crossing of the Irrawaddy on the 29th March 1943.

Dear Mrs. Stock,

The powers that be have instructed me to look after your son's things, and on going through his box this morning I came across a couple of unsigned letters which I think you may like to have. I am also sending a list of his correspondence, which seems to give the names of people in whom he was interested. His actual kit is of no particular value, being mostly uniform of one sort or another. I have packed it up, and it will be sent off to the 2nd Echelon (Jhansi), who look after these things.

I should like to say how very sorry I was to hear that your son was missing. I know for a fact that he had joined up with other officers and men on the morning of the 29th March on the west banks of the Irrawaddy. I did not see him afterwards, as I had to rejoin the bulk of the column who were still on the eastern side of the river. It seems that Tom and one or two men got separated from their party a few days later, and I think it very likely that they may all be prisoners. I know that the Japanese hold quite a number of prisoners, and you must continue to hope that he is among them. I want you to know what a stout show Tom put up in Burma. As you know, he only joined us at the eleventh hour, and in consequence missed all the strenuous training. In spite of this disadvantage and it was a big handicap, as our activities were pretty searching both mentally and physically, he was settling down well, and becoming more useful every day.

Our column eventually landed in China, and we were flown home in an hour and three quarters! The Chinese and Americans couldn't do too much for us. Since then we have had a spell of anti-malaria treatment in hospital, a month's leave, and we are now shaking down again as a battalion. You may depend that I shall do what I can for your son's things, and if there is anything I can do for you please don't hesitate to ask.

Yours sincerely, J.S. Pickering.

As mentioned previously, the 13th King's remained at Karachi for the rest of war and on the 1st March 1945, the newly promoted Major Pickering assumed command of the battalion for a period of three weeks, while Lieutenant-Colonel A.J. Newall was away on other duties. The battalion was disbanded on the 5th December 1945, after all personnel had either been transferred to other units, or been repatriated to the United Kingdom. The battalion war diary stated that:

On the 10th July 1945: Majors J.S. Pickering (MC), J. Coughlan, H. Cotton and Lieutenant Quartermaster W. Livingstone, left for repatriation to the UK after long service with the battalion.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including the original citation for John Pickering's Military Cross, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

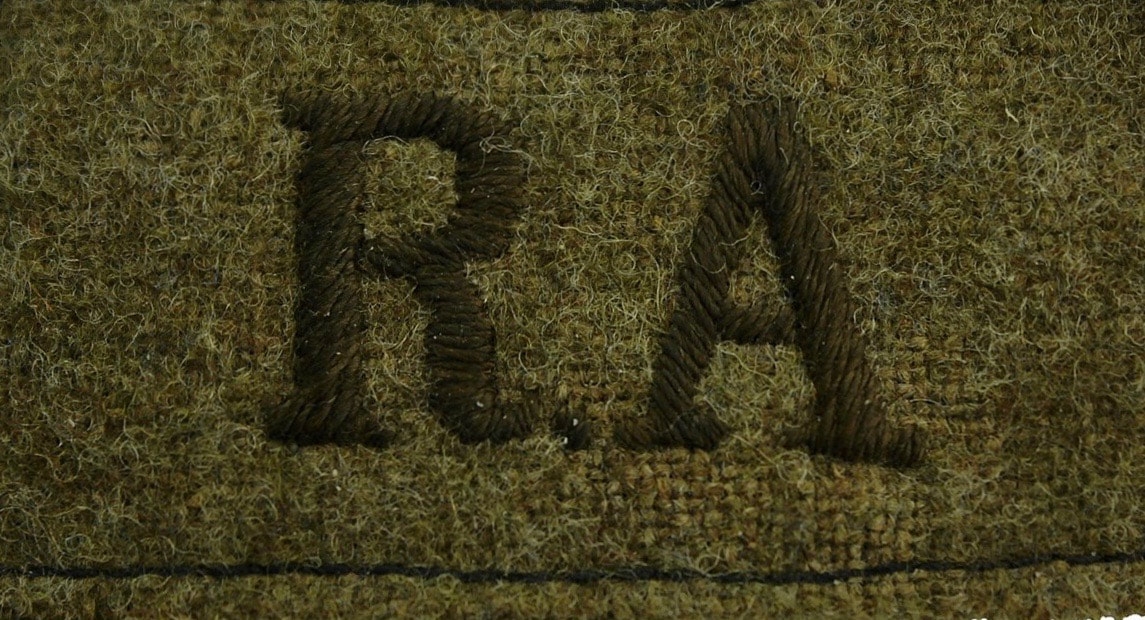

Cap badge of the Royal Engineers.

Cap badge of the Royal Engineers.

PIKE, RONALD

Rank: Corporal

Service No: 1873420

Regiment/Service: Royal Engineers att. The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Chindit Column: 5

Other details:

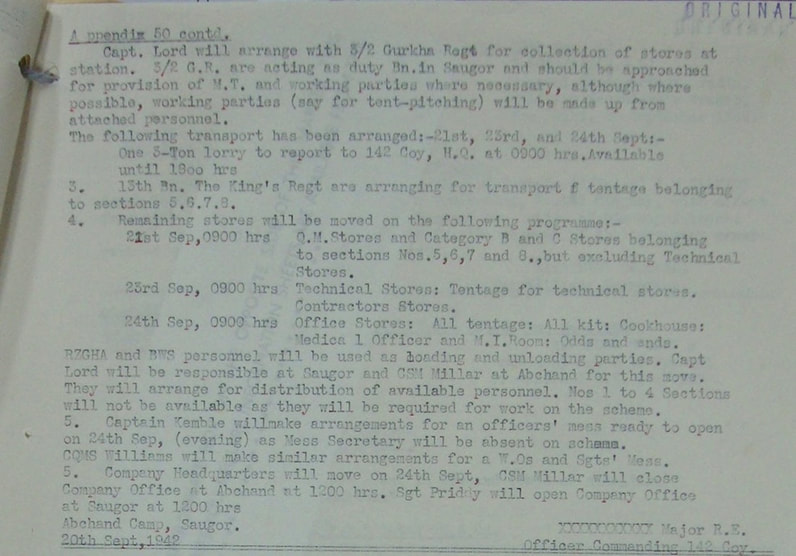

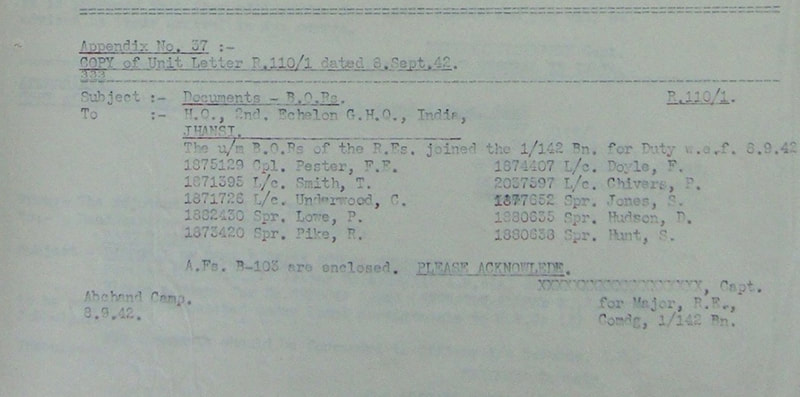

Ronald Pike was from Sidmouth in Devon and had served with the Royal Engineers during the early years of WW2, before being posted overseas. On the 8th September 1942, he joined the ranks of 142 Commando at their Abchand training camp in the Central Provinces of India and began his involvement with the Chindits.

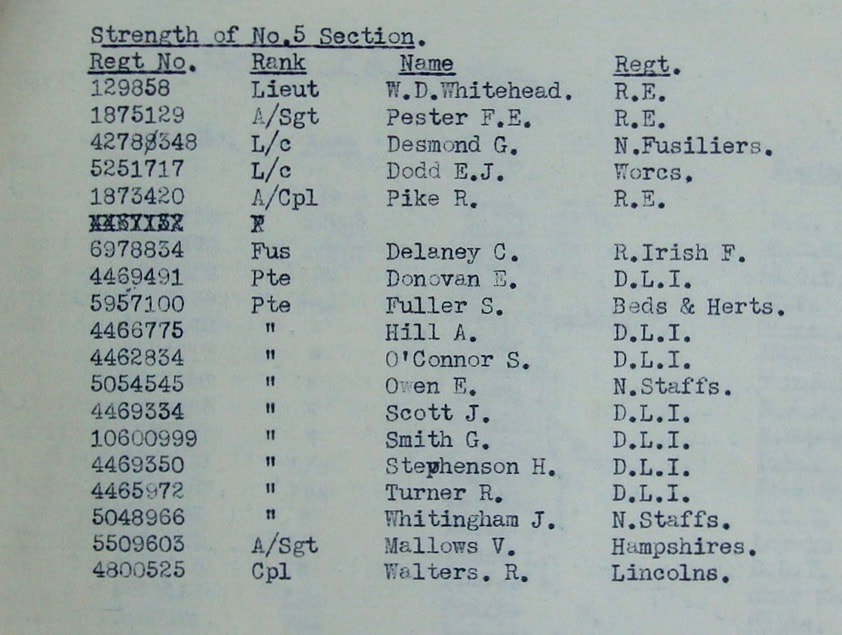

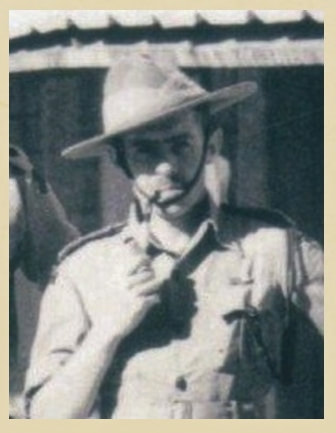

Ronald was posted to No. 5 Column Commando Platoon under the command, firstly of Lt. David Whitehead of the Royal Engineers and ultimately in Burma under the leadership of Captain Jim Harman of the Gloucestershire Regiment. No. 5 Column was commanded by Major Bernard Fergusson of the Black Watch, and it is from his book, Beyond the Chindwin, that we learn most about Corporal Pike's contribution on Operation Longcloth.

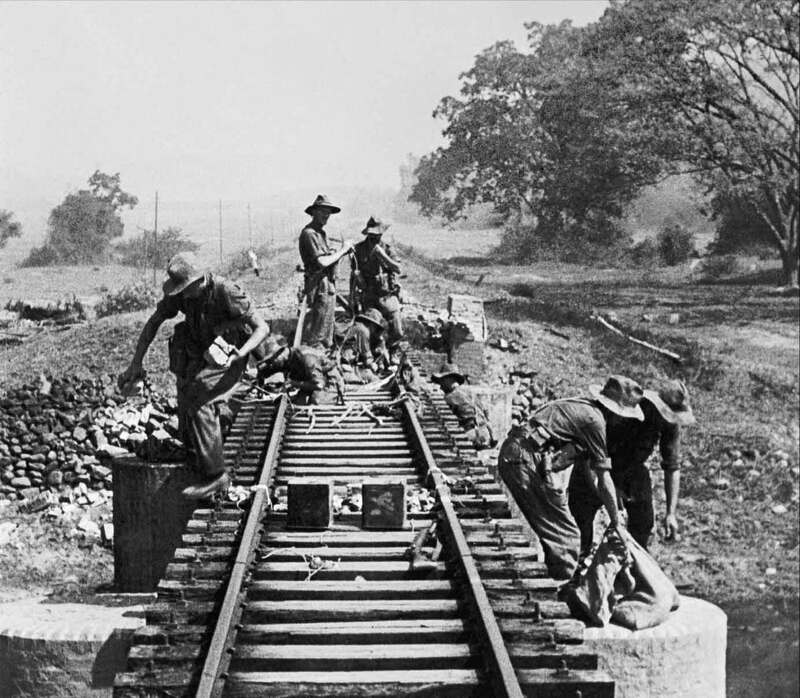

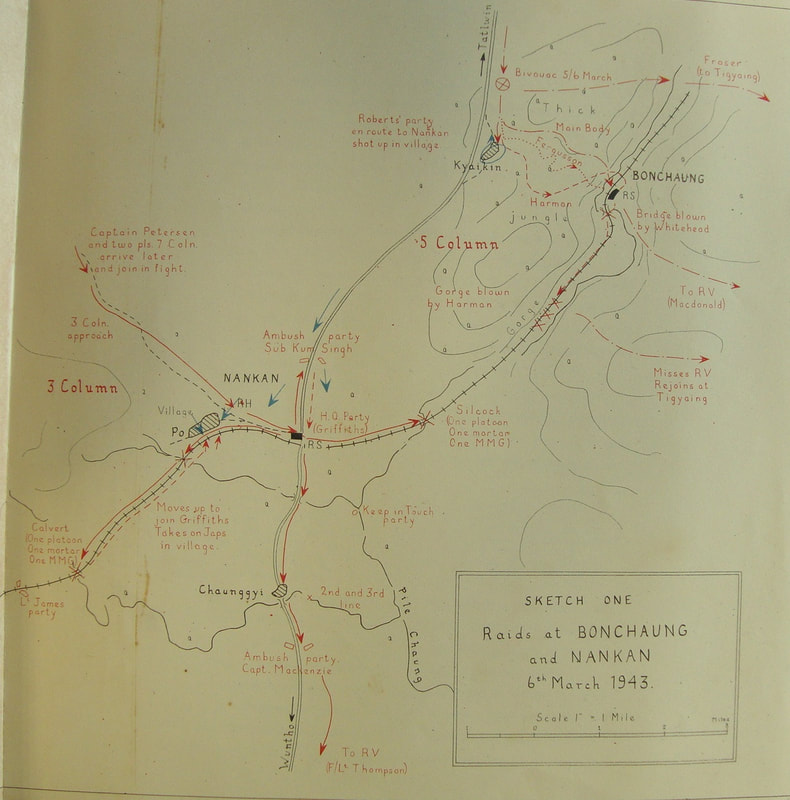

Fergusson's main task in 1943, was to organise the demolition of the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway line close to the village of Bonchaung. His commandos were set their objectives and went about their business in a methodical and professional manner. Fergusson recalled:

As time went on, I became more and more anxious to hurry to Bonchaung, and so I told Gerry (Roberts) to come on with men and animals as fast as he could, while I pushed on ahead with Peter Dorans. We got there just after five o'clock on the 6th March, to find everybody in position. David Whitehead, Corporal Pike, and various other sappers were sitting on the bridge with their legs swinging, working away like civvies.

I found Duncan Menzies, who told me that Jim Harman (and Sgt. Pester) had had a bad time in the jungle, and had turned up at Bonchaung half an hour before, having got hopelessly bushed: he had now set off down the railway line towards the gorge. David hoped to have the bridge ready for blowing at half-past eight or nine; he had already laid a "hasty" demolition, which we could blow if interrupted. Until he was ready there was nothing whatever to be done, bar have a cup of tea and I had several. Duncan had everybody ready to move at nine, mules loaded and all. David gave us five minutes warning, and told us that the big bang would be preceded by a little bang. The little bang duly went off, and there was a short delay; then ……..

The flash illumined the whole hillside. It showed the men standing tense and waiting, the muleteers with a good grip of their mules; and the brown of the path and the green of the trees preternaturally vivid. Then came the bang. The mules plunged and kicked, the hills for miles around rolled the noise of it about their hollows and flung it to their neighbours. Mike Calvert and John Fraser heard it away in their distant bivouacs; and all of us hoped that John Kerr and his little group of abandoned men, whose sacrifice at Kyaik-in had helped to make it possible, heard it also, and knew that we had accomplished that which we had come so far to do. Four miles farther on we met Alec MacDonald's guides; and just as we were going into bivouac we heard another great explosion, and knew that Jim Harman had blown the gorge.

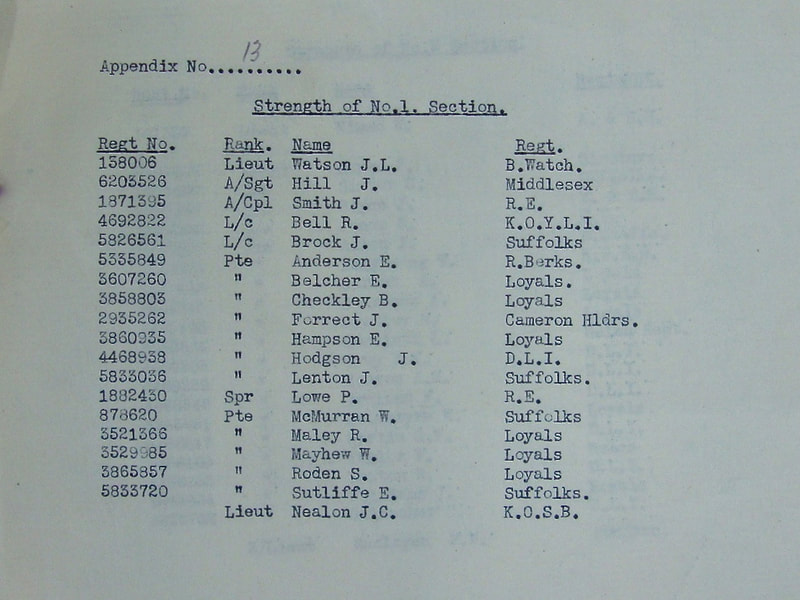

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the first part of the story, including the nominal roll for No. 5 Column's commando Platoon. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Rank: Corporal

Service No: 1873420

Regiment/Service: Royal Engineers att. The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Chindit Column: 5

Other details:

Ronald Pike was from Sidmouth in Devon and had served with the Royal Engineers during the early years of WW2, before being posted overseas. On the 8th September 1942, he joined the ranks of 142 Commando at their Abchand training camp in the Central Provinces of India and began his involvement with the Chindits.

Ronald was posted to No. 5 Column Commando Platoon under the command, firstly of Lt. David Whitehead of the Royal Engineers and ultimately in Burma under the leadership of Captain Jim Harman of the Gloucestershire Regiment. No. 5 Column was commanded by Major Bernard Fergusson of the Black Watch, and it is from his book, Beyond the Chindwin, that we learn most about Corporal Pike's contribution on Operation Longcloth.

Fergusson's main task in 1943, was to organise the demolition of the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway line close to the village of Bonchaung. His commandos were set their objectives and went about their business in a methodical and professional manner. Fergusson recalled:

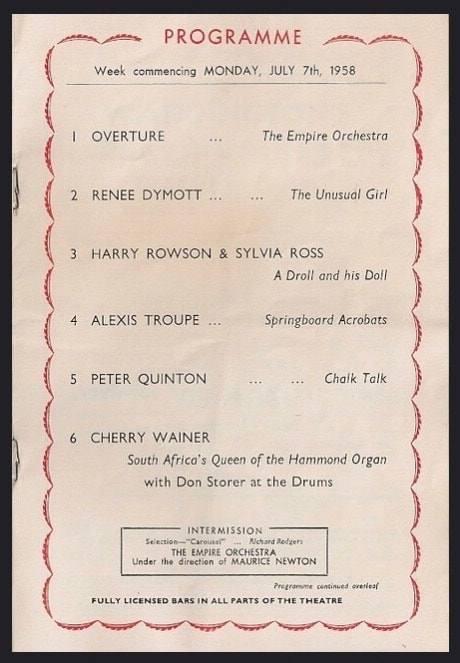

As time went on, I became more and more anxious to hurry to Bonchaung, and so I told Gerry (Roberts) to come on with men and animals as fast as he could, while I pushed on ahead with Peter Dorans. We got there just after five o'clock on the 6th March, to find everybody in position. David Whitehead, Corporal Pike, and various other sappers were sitting on the bridge with their legs swinging, working away like civvies.