Captain William Alfred Jelliss

The cap badge of the South Staffordshire Regiment.

The cap badge of the South Staffordshire Regiment.

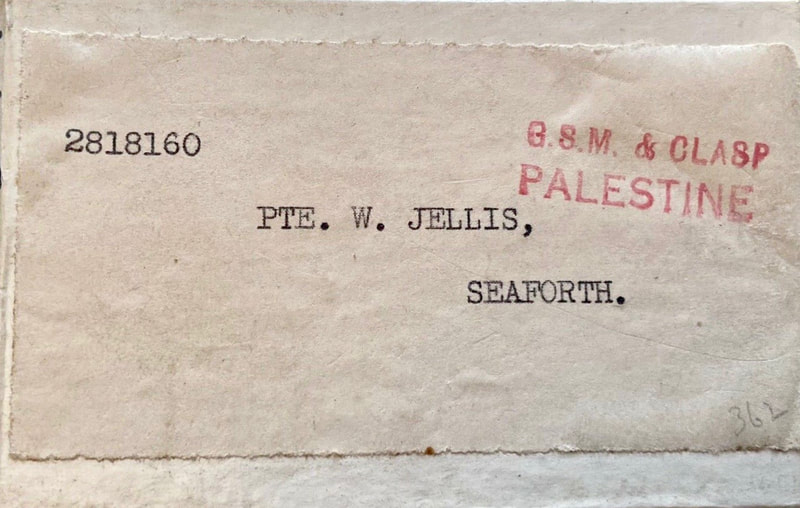

William Alfred Jelliss was born on the 6th December 1911 in the west Midlands city of Coventry. He enlisted into the British Army with the service number 2818160 and was posted to the Seaforth Highlanders, with whom he eventually attained the rank of Company Quartermaster Sergeant. On the outbreak of WW2, he was called up as a reservist, presumably still with the Seaforths and was part of the British Expeditionary Force that was sent to France.

After survivng the debacle at Dunkirk, William was sent to Sandhurst Officer Training Centre. He succefully passed out from Sandhurst, taking a commission as 2nd Lieutenant in the South Staffordshire Regiment with his new Army number 204373. In February 1941, William married Irene Attenbury at St. Paulinus Church in Crayford, a small town located on the London/Kent borders. The couple began their married life in Crayford, before William, now promoted to full Lieutenant was posted overseas to India.

It is most likely that Lt. Jelliss voyaged to India in mid-1942, as part of the many large convoys that travelled to the East via the Cape of Good Hope in order to avoid U-Boat activity in the North Atlantic and the enemy domiated Mediterranean Sea. It is known that William arrived at the Chindit training camp located at Bharon in the Central Provinces of India on the 11th November 1942. He was placed into the ranks of Chindit Column No. 7 under the overall command of Major Kenneth Gilkes of the King's Regiment and was eventually given charge of Rifle Platoon No. 14. The columns were by now making their final adjustments in personnel and numbers and the Brigade was about to undertake its first full air supply practice in combination with the RAF.

During the operation 7 Column tended to shadow Brigadier Wingate and his Brigade Head Quarters, but on occasions the column did split up into sub-units in order to perform various tasks required by Wingate as the expedition unfolded. This often left senior officers, such as Leslie Cottrell and Willliam Jelliss, in temporary charge of large groups of men and away from the comfort and security of the main column strength.

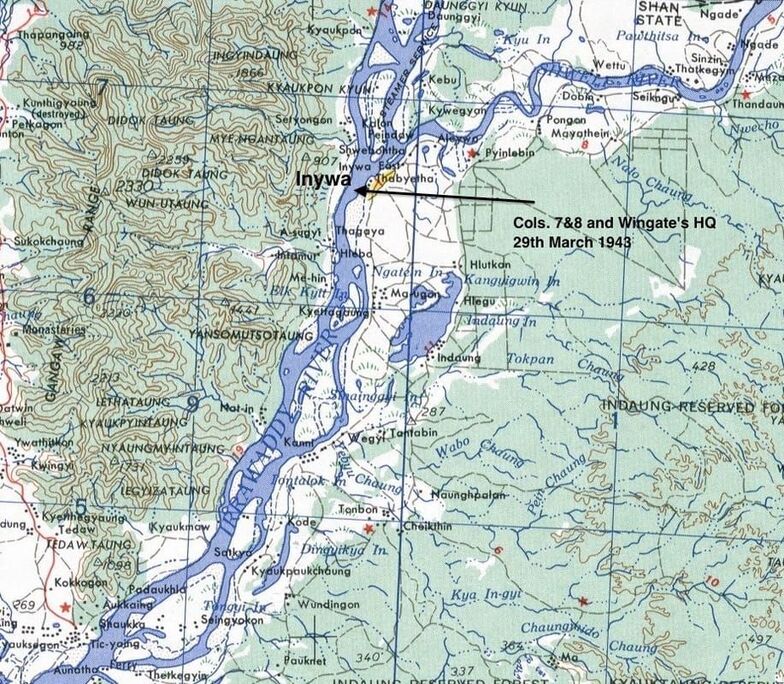

After six weeks behind enemy lines, it was decided to end the operation and head back to India. On the 29th March 1943, Wingate's HQ, Chindit Columns 7 and 8 and Northern Group Head Quarters were all gathered on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River close to the Burmese village of Inywa.

A bridgehead party was formed and began crossing the mile wide river in hired country boats, which were manned and piloted by local Burmese villagers. Lt. Jelliss and his platoon were chosen to form part of the advance group and he and his men crossed in the second boat. Unfortunately, a Japanese patrol on the western bank opened up on the leading boats with machine gun and mortar fire and many casualties were inflicted on the Chindits attempting to cross the river. On witnessing these events, Wingate and his column commanders decided to abandon the crossing and moved back in to the scrub jungle close to the riverside. Eventually, it was decided that the remainder of the Brigade would split up and Wingate sent Scott and Gilkes' columns away from the area heading roughly south-east.

Another soldier involved in the advance crossing of the Irrawaddy was Pte. Charles Aves, a member of No. 15 Rifle platoon from within 7 Column. He remembered:

"As quietly as possible, we made our way to the small boats at the bank of the river, where a Burmese boatman had been paid to ferry us across. I think I was in the second or third boat. We proceeded across the river and it seemed like ages getting across. I suppose there were eight or ten of us in each boat. Just as we and a couple of other boats reached the bank, the Japs opened up with mortar and automatic machine-gun fire from a point some few hundred yards north of our landing area. We couldn't see them, for they were well concealed in a jungle copse and we scrambled ashore.

The total number of men that formed up (on the west bank) was sixty-five. There was Captain Oakes, Lieutenant Jelliss, a second Lieutenant, two or three Sergeants, some Corporals and about fifty other ranks. I asked what happened to Captain Hastings, who had been my platoon officer until he was promoted to Column Adjutant. I was told that the boat he was in had been hit and he was flung into the river and swept away.

In retrospect, we could say that had we attacked the Jap unit it is possible that the rest of Wingate's force could have crossed reasonably safely, but I don't know what orders our senior officers had. I believe we had no means of signalling across the river and at this time most of the men were ill and short of food. The sixty-five of us who had crossed the river moved quickly away and a few miles later made camp in dense jungle. This was the rendezvous point for those who had crossed the river, but by the morning no one else had turned up. We waited another day and then our officers led us off towards the Chindwin."

NB. From looking through the 13th King's War diaries for 1943, it seems likely that the 2nd Lieutenant mentioned by Charles Aves, was John Thomas Kelly formerly of the Border Regiment.

After survivng the debacle at Dunkirk, William was sent to Sandhurst Officer Training Centre. He succefully passed out from Sandhurst, taking a commission as 2nd Lieutenant in the South Staffordshire Regiment with his new Army number 204373. In February 1941, William married Irene Attenbury at St. Paulinus Church in Crayford, a small town located on the London/Kent borders. The couple began their married life in Crayford, before William, now promoted to full Lieutenant was posted overseas to India.

It is most likely that Lt. Jelliss voyaged to India in mid-1942, as part of the many large convoys that travelled to the East via the Cape of Good Hope in order to avoid U-Boat activity in the North Atlantic and the enemy domiated Mediterranean Sea. It is known that William arrived at the Chindit training camp located at Bharon in the Central Provinces of India on the 11th November 1942. He was placed into the ranks of Chindit Column No. 7 under the overall command of Major Kenneth Gilkes of the King's Regiment and was eventually given charge of Rifle Platoon No. 14. The columns were by now making their final adjustments in personnel and numbers and the Brigade was about to undertake its first full air supply practice in combination with the RAF.

During the operation 7 Column tended to shadow Brigadier Wingate and his Brigade Head Quarters, but on occasions the column did split up into sub-units in order to perform various tasks required by Wingate as the expedition unfolded. This often left senior officers, such as Leslie Cottrell and Willliam Jelliss, in temporary charge of large groups of men and away from the comfort and security of the main column strength.

After six weeks behind enemy lines, it was decided to end the operation and head back to India. On the 29th March 1943, Wingate's HQ, Chindit Columns 7 and 8 and Northern Group Head Quarters were all gathered on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River close to the Burmese village of Inywa.

A bridgehead party was formed and began crossing the mile wide river in hired country boats, which were manned and piloted by local Burmese villagers. Lt. Jelliss and his platoon were chosen to form part of the advance group and he and his men crossed in the second boat. Unfortunately, a Japanese patrol on the western bank opened up on the leading boats with machine gun and mortar fire and many casualties were inflicted on the Chindits attempting to cross the river. On witnessing these events, Wingate and his column commanders decided to abandon the crossing and moved back in to the scrub jungle close to the riverside. Eventually, it was decided that the remainder of the Brigade would split up and Wingate sent Scott and Gilkes' columns away from the area heading roughly south-east.

Another soldier involved in the advance crossing of the Irrawaddy was Pte. Charles Aves, a member of No. 15 Rifle platoon from within 7 Column. He remembered:

"As quietly as possible, we made our way to the small boats at the bank of the river, where a Burmese boatman had been paid to ferry us across. I think I was in the second or third boat. We proceeded across the river and it seemed like ages getting across. I suppose there were eight or ten of us in each boat. Just as we and a couple of other boats reached the bank, the Japs opened up with mortar and automatic machine-gun fire from a point some few hundred yards north of our landing area. We couldn't see them, for they were well concealed in a jungle copse and we scrambled ashore.

The total number of men that formed up (on the west bank) was sixty-five. There was Captain Oakes, Lieutenant Jelliss, a second Lieutenant, two or three Sergeants, some Corporals and about fifty other ranks. I asked what happened to Captain Hastings, who had been my platoon officer until he was promoted to Column Adjutant. I was told that the boat he was in had been hit and he was flung into the river and swept away.

In retrospect, we could say that had we attacked the Jap unit it is possible that the rest of Wingate's force could have crossed reasonably safely, but I don't know what orders our senior officers had. I believe we had no means of signalling across the river and at this time most of the men were ill and short of food. The sixty-five of us who had crossed the river moved quickly away and a few miles later made camp in dense jungle. This was the rendezvous point for those who had crossed the river, but by the morning no one else had turned up. We waited another day and then our officers led us off towards the Chindwin."

NB. From looking through the 13th King's War diaries for 1943, it seems likely that the 2nd Lieutenant mentioned by Charles Aves, was John Thomas Kelly formerly of the Border Regiment.

Another soldier present on the west bank of the Irrawaddy that day, was Pte. Robert Hyner of 14 Rifle Platoon. He recalled:

"About a day after we had left the riverside and whilst resting in a jungle glade, our group was caught out by a Japanese patrol. We had paid the penalty for not placing sentries around the perimeter of the rest camp and in a mad panic some of the men ran away to escape the oncoming Japanese."

Robert Hyner became separated from his best pal, Bill, and even more disastrously many of the men had left behind their precious packs and rifles. This was the last time Lieutenant Jelliss led 14 Platoon and Pte. Hyner found himself in a group of about 25 men, with Captain Oakes in command. After all the confusion of the ambush had died down, William Jelliss collected together a party of men which included Pte. Charles Aves:

"Cpl. Hickman and I moved like lightning, carrying only our rifles. We ran up the nullah and as we did so we both picked up a pack which had been left by others from our party. We broke the speed record and managed to climb up behind some rocks; there were a few of our party there and we poured rifle fire on where the Japs were coming from. After a while we ceased fire. We couldn't see the Japs, but we could hear them shouting to each other. I think they must have been looting all the packs we had left behind.

We withdrew up the hill and then sorted ourselves out. There was Lieutenant Jelliss, two Sergeants, Corporal Hickman and seven other men. Corporal Hickman and I looked into the two packs we had picked up; mine had belonged to Captain Oakes and contained all the maps for the route back to the Chindwin. In the other which belonged to the young 2nd Lieutenant was a quantity of silver rupees. We then found that we only had two water bottles between us. We went back to the site of the attack, but the Japs were still there, so we took off west as fast as we could without a stop for two hours.

As night fell, we took stock. We all had rifles, ammunition and grenades, but no food and little water. The Lieutenant (Jelliss) was a good officer who decided to involve us all in decisions if needed. We had another bonus, me, as I was the only one who could speak any Burmese, thanks to the teachings of my pal Stan Allnutt. Anyone can make themselves understood in their quest for food, but I was able to ask the villagers for the Headman and for the position of the nearest Japanese. In the morning we decided to make for the nearest village. We learned a lot about ourselves during this period. We enjoyed being in the jungle, the thicker the better, here we felt safe. We could find paths among the undergrowth, however indistinct and we knew that they would eventually lead to water or a village. We were a good team all in all and got on fairly well.

The first village was quite near and I went in first with Lieutenant Jelliss, while the others kept a look out. The villagers were very friendly and helpful, all smiles and generosity. In fact our experience showed all the Burmese to be very helpful, with one exception; I can't recall the name of the village, but shall call it Maungde. We had travelled quite a few miles, probably about twenty each day, when came upon Maungde. We knew this village was different to all the others, we could tell straight away that there was something wrong. The Headman was uneasy; we always watched out to see whether anyone disappeared when we entered a village and it seemed to us one or two shifty characters had moved out of sight.

We didn't hesitate, we left straight away, no messing. We didn't give them a chance to call on any Japs, we shot through like lightning, and disappeared over the horizon with no casualties. It eventually transpired that some of the other men from our original group were betrayed when they went through the same village and a number of them were killed by enemy fire. We were eventually picked up by a patrol of Seaforth Highlander's at the Chindwin and taken by boat to the western banks and then on to Tamu. We were then taken to Imphal by lorry and into hospital. I immediately fell down with malaria. We were nursed back to health by Matron McGearey at Imphal and were even visited by the Brigadier."

Lt. Jelliss did not spend too long in hospital recuperating from his time on the expedition. He is recorded within the pages of the 7 Column War diary, as being the officer responsible for meeting the rest of the column, who had taken several more weeks to exit Burma via the Chinese Yunnan Province and for arranging all their dietry and accomodation requirements at Dibrugarh in India.

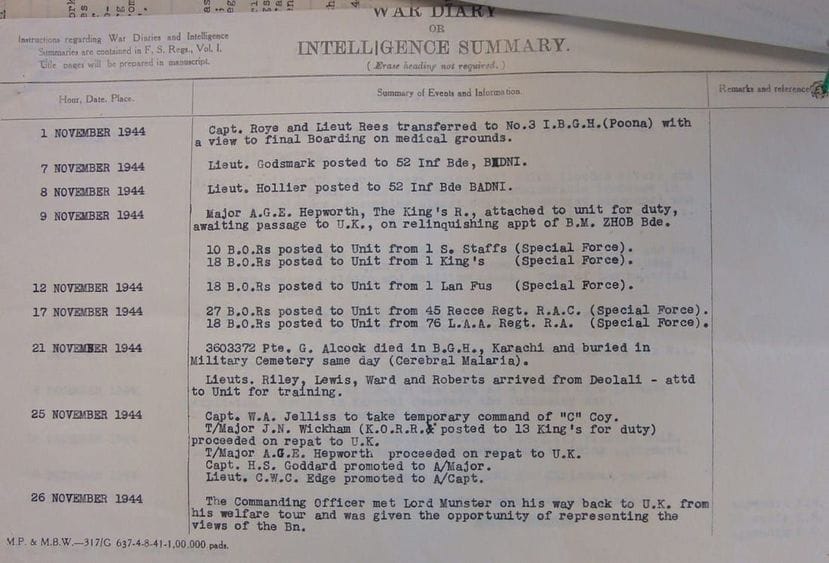

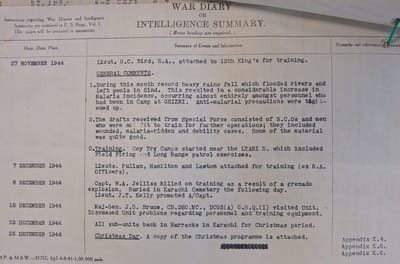

After recovering from the hardships experienced during the first Wingate expedition, the surviving soldiers from the 13th King's were posted to the Napier Barracks in Karachi, where the battalion performed local garrison and policing duties. By November 1944, William Jelliss had been promoted to Captain and was the officer in charge of C' Company, which was a direct amalgamation of the soldiers that had formed 7 Column in 1943, including both Nos. 14 & 15 Rifle Platoons.

"About a day after we had left the riverside and whilst resting in a jungle glade, our group was caught out by a Japanese patrol. We had paid the penalty for not placing sentries around the perimeter of the rest camp and in a mad panic some of the men ran away to escape the oncoming Japanese."

Robert Hyner became separated from his best pal, Bill, and even more disastrously many of the men had left behind their precious packs and rifles. This was the last time Lieutenant Jelliss led 14 Platoon and Pte. Hyner found himself in a group of about 25 men, with Captain Oakes in command. After all the confusion of the ambush had died down, William Jelliss collected together a party of men which included Pte. Charles Aves:

"Cpl. Hickman and I moved like lightning, carrying only our rifles. We ran up the nullah and as we did so we both picked up a pack which had been left by others from our party. We broke the speed record and managed to climb up behind some rocks; there were a few of our party there and we poured rifle fire on where the Japs were coming from. After a while we ceased fire. We couldn't see the Japs, but we could hear them shouting to each other. I think they must have been looting all the packs we had left behind.

We withdrew up the hill and then sorted ourselves out. There was Lieutenant Jelliss, two Sergeants, Corporal Hickman and seven other men. Corporal Hickman and I looked into the two packs we had picked up; mine had belonged to Captain Oakes and contained all the maps for the route back to the Chindwin. In the other which belonged to the young 2nd Lieutenant was a quantity of silver rupees. We then found that we only had two water bottles between us. We went back to the site of the attack, but the Japs were still there, so we took off west as fast as we could without a stop for two hours.

As night fell, we took stock. We all had rifles, ammunition and grenades, but no food and little water. The Lieutenant (Jelliss) was a good officer who decided to involve us all in decisions if needed. We had another bonus, me, as I was the only one who could speak any Burmese, thanks to the teachings of my pal Stan Allnutt. Anyone can make themselves understood in their quest for food, but I was able to ask the villagers for the Headman and for the position of the nearest Japanese. In the morning we decided to make for the nearest village. We learned a lot about ourselves during this period. We enjoyed being in the jungle, the thicker the better, here we felt safe. We could find paths among the undergrowth, however indistinct and we knew that they would eventually lead to water or a village. We were a good team all in all and got on fairly well.

The first village was quite near and I went in first with Lieutenant Jelliss, while the others kept a look out. The villagers were very friendly and helpful, all smiles and generosity. In fact our experience showed all the Burmese to be very helpful, with one exception; I can't recall the name of the village, but shall call it Maungde. We had travelled quite a few miles, probably about twenty each day, when came upon Maungde. We knew this village was different to all the others, we could tell straight away that there was something wrong. The Headman was uneasy; we always watched out to see whether anyone disappeared when we entered a village and it seemed to us one or two shifty characters had moved out of sight.

We didn't hesitate, we left straight away, no messing. We didn't give them a chance to call on any Japs, we shot through like lightning, and disappeared over the horizon with no casualties. It eventually transpired that some of the other men from our original group were betrayed when they went through the same village and a number of them were killed by enemy fire. We were eventually picked up by a patrol of Seaforth Highlander's at the Chindwin and taken by boat to the western banks and then on to Tamu. We were then taken to Imphal by lorry and into hospital. I immediately fell down with malaria. We were nursed back to health by Matron McGearey at Imphal and were even visited by the Brigadier."

Lt. Jelliss did not spend too long in hospital recuperating from his time on the expedition. He is recorded within the pages of the 7 Column War diary, as being the officer responsible for meeting the rest of the column, who had taken several more weeks to exit Burma via the Chinese Yunnan Province and for arranging all their dietry and accomodation requirements at Dibrugarh in India.

After recovering from the hardships experienced during the first Wingate expedition, the surviving soldiers from the 13th King's were posted to the Napier Barracks in Karachi, where the battalion performed local garrison and policing duties. By November 1944, William Jelliss had been promoted to Captain and was the officer in charge of C' Company, which was a direct amalgamation of the soldiers that had formed 7 Column in 1943, including both Nos. 14 & 15 Rifle Platoons.

In the early days at the Napier Barracks, Charles Aves, who had spent long periods in the company of Captain Jelliss on the journey out from Burma in 1943, began to notice a change in the officer's demeanour. Aves recalled that William seemed very distracted and unhappy and would no longer speak to or acknowledge the men he had led back to India. This seemed very strange to Pte. Aves, as he and Captain Jelliss had gotten to know each other quite well during those difficult weeks and had even arranged to have a "slap up meal" once they had returned safely across the Chindwin.

Charles Aves remembered:

"Most of my friends were lucky and survived the expedition. The officer who came out with us and with whom we were going to have this great meal, seemed very unhappy and he didn't acknowledge any of us after a while. I couldn't understand this as we had been so close, but he just wouldn't speak to us anymore. Anyway, it turned out that he had received a message; you see we had all got our accumulated post after we had got back to Imphal and I'm afraid that his wife had written to him to say that she had fallen in love with somebody else. Sadly, later on he was killed as the result of an accident, whilst handling a plastic grenade during a training exercise. For a good while he seemed so miserable, we all felt so sorry for him and we were very sorry when he died."

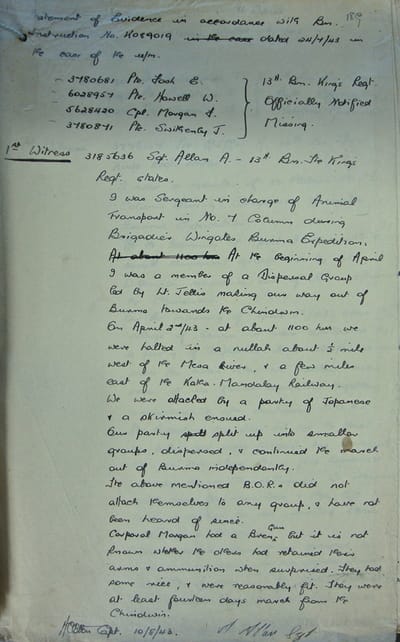

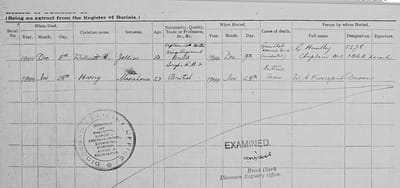

There are three pieces of documentary evidence in relation to William Jelliss' sad demise. Two of these: the battalion war diary entry (seen in the Gallery below) and of course, Charles Aves' testimony suggest that it was the result of a training accident involving a plastic grenade. In the Indian Office records for deaths in 1944, the information given for this incident is "gunshot wound, accidental." I feel that the former explanation is probably the most accurate, given that the first-hand witness account of Pt. Aves and the Adjutant's entry into battalion War diary, are sources from men who were actually present within the 13th King's at the time.

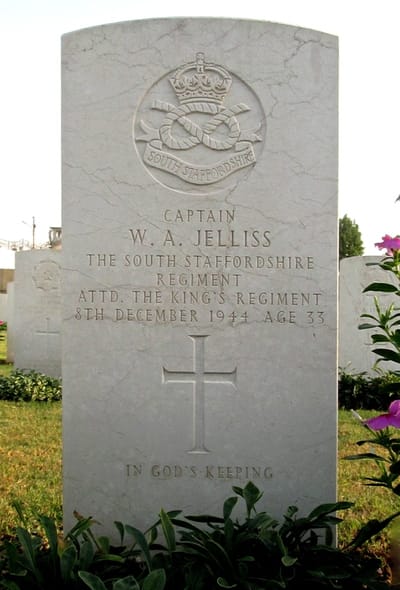

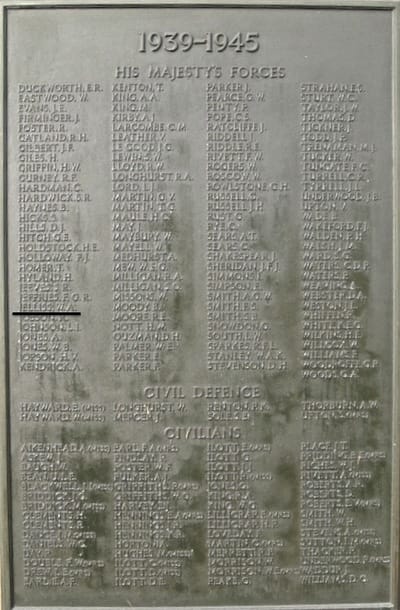

Captain William Alfred Jelliss died at the Indian General Hospital in Karachi on the 8th December 1944 and was buried the following day at Karachi War Cemetery, with his funeral being conducted by the Chaplain from the hospital, Mr. G. Huntley. After due process, all William's possessions and effects were sent home to his wife, Irene.

To view William's CWGC details. please click on the following link:

www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2178315/JELLISS,%20WILLIAM%20ALFRED

Seen below is a final Gallery of images in relation to this rather sad story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Charles Aves remembered:

"Most of my friends were lucky and survived the expedition. The officer who came out with us and with whom we were going to have this great meal, seemed very unhappy and he didn't acknowledge any of us after a while. I couldn't understand this as we had been so close, but he just wouldn't speak to us anymore. Anyway, it turned out that he had received a message; you see we had all got our accumulated post after we had got back to Imphal and I'm afraid that his wife had written to him to say that she had fallen in love with somebody else. Sadly, later on he was killed as the result of an accident, whilst handling a plastic grenade during a training exercise. For a good while he seemed so miserable, we all felt so sorry for him and we were very sorry when he died."

There are three pieces of documentary evidence in relation to William Jelliss' sad demise. Two of these: the battalion war diary entry (seen in the Gallery below) and of course, Charles Aves' testimony suggest that it was the result of a training accident involving a plastic grenade. In the Indian Office records for deaths in 1944, the information given for this incident is "gunshot wound, accidental." I feel that the former explanation is probably the most accurate, given that the first-hand witness account of Pt. Aves and the Adjutant's entry into battalion War diary, are sources from men who were actually present within the 13th King's at the time.

Captain William Alfred Jelliss died at the Indian General Hospital in Karachi on the 8th December 1944 and was buried the following day at Karachi War Cemetery, with his funeral being conducted by the Chaplain from the hospital, Mr. G. Huntley. After due process, all William's possessions and effects were sent home to his wife, Irene.

To view William's CWGC details. please click on the following link:

www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2178315/JELLISS,%20WILLIAM%20ALFRED

Seen below is a final Gallery of images in relation to this rather sad story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

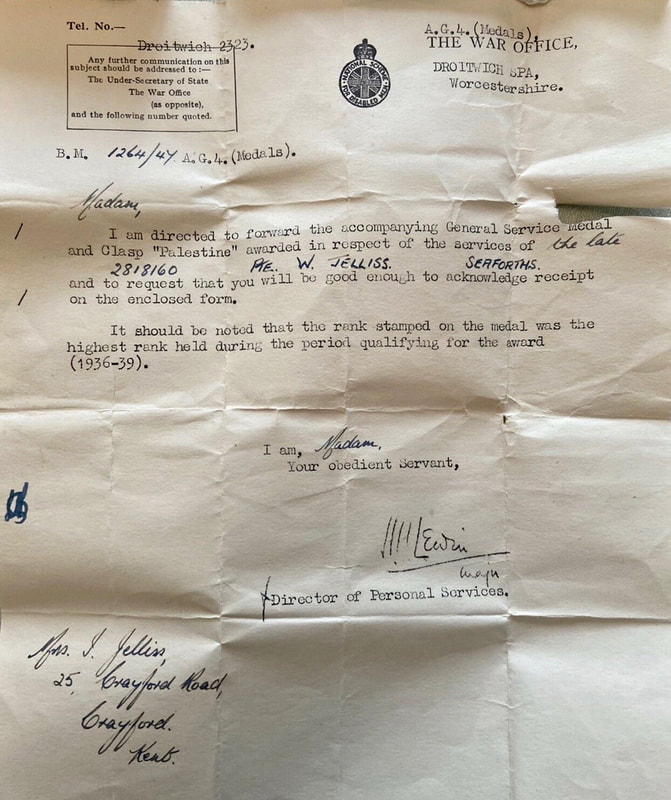

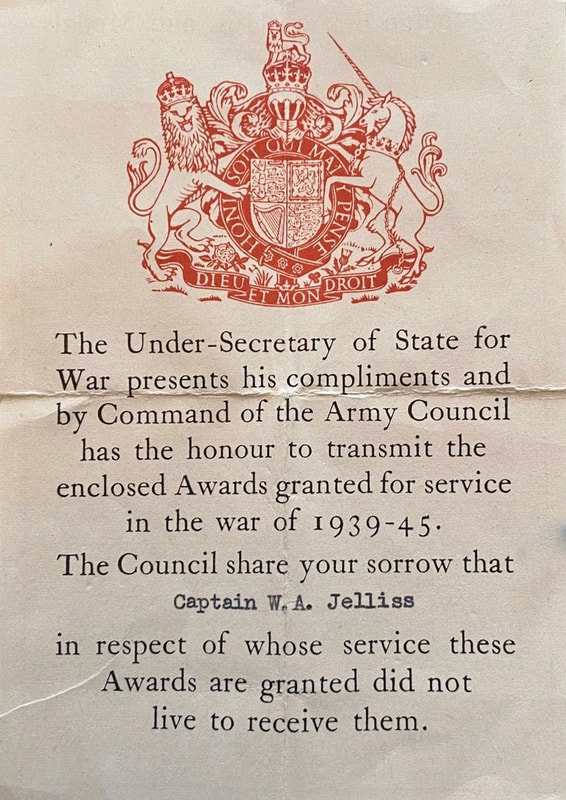

Update 30/08/2021.

The medals of William Jelliss and other related paperwork were put up for sale on eBay in late July 2021 and sold for £569. The auction had included much of the information found on this website which must have affected and influenced the high price achieved. Seen below are some of the images used in the sale to illustrate the auction item. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

The medals of William Jelliss and other related paperwork were put up for sale on eBay in late July 2021 and sold for £569. The auction had included much of the information found on this website which must have affected and influenced the high price achieved. Seen below are some of the images used in the sale to illustrate the auction item. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, December 2016.