Pte. Charles Aves

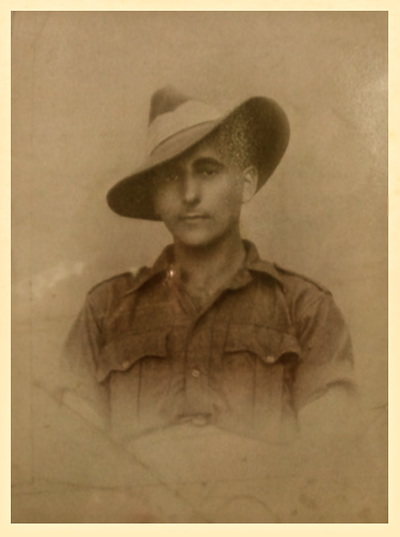

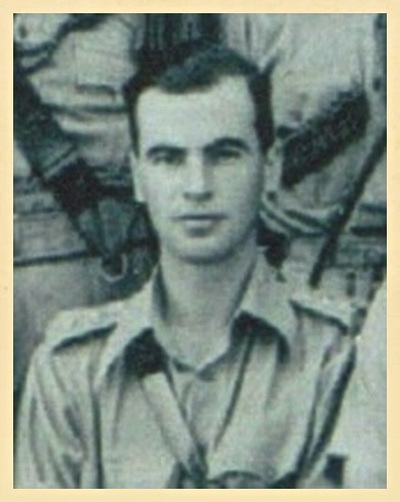

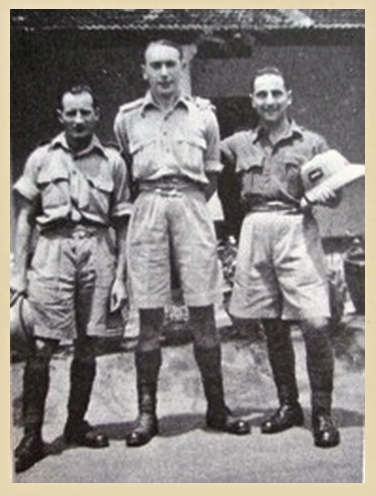

Charles Aves at Secunderabad in 1942.

Charles Aves at Secunderabad in 1942.

Charles Alfred William Aves was born in the London Borough of Southwark in the year 1919 and lived with his family in the streets adjacent to the Thames by Tower Bridge. He went to school north of the river in nearby Bethnal Green, leaving full-time education, as many working class children did in those days at the age of fourteen. Charles' father had been severely wounded during WW1 and had set himself up in business as a taylor. After finishing school, Charles went to work for his father, running errands and making deliveries from the family home.

The audio memoir of Charles Aves is available at the Imperial War Museum and it is from this recorded testimony, that most of the information written here is taken. Charles made great efforts throughout his post-war life to record, whether verbally, or indeed in writing, his thoughts and feelings in regards to his WW2 experience. His is an extremely valuable viewpoint, as it comes from a man who was conscripted to serve and had expressed his doubts about the validity of the war.

To listen to his full audio memoir, please click on the following link:

www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80015020

Charles recalled:

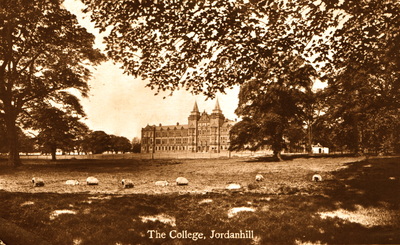

"In 1939 things were very confused at home and in the press and I was not sure whether we should be going to war, but I was conscripted into the Army in September 1940 and sent to Jordan Hill College Barracks up at Glasgow and joined 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment. I arrived by train at Glasgow on the 13th September, being dropped off on platform 13 and then being placed into Platoon 13 of the 13th King’s. 13 was to become my lucky number."

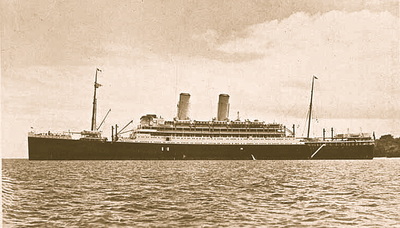

Over the following 12 months, Pte. Aves completed his initial infantry training at Glasgow and then joined the King's as they travelled down south to take up their new role, as a coastal defence battalion patrolling the coastline towns of Essex and Suffolk. In late 1941, the 13th King's were told to prepare for a posting overseas and journeyed up to Liverpool on the 6th December, with orders to board the troopship Oronsay which was anchored at the Alexandria Docks on the River Mersey. Unbeknown to the King's, they were bound for India and began an eight week voyage on the 8th December 1941, which would take them around the Cape of Good Hope.

There were over 3000 men aboard the troopship and conditions were very cramped for the Other ranks, who shared the hot and claustrophobic lower decks. As with all convoy experiences in WW2, sea-sickness was a severe problem for many of the men, especially in those early days of the voyage as the ships passed through the rougher north Atlantic waters. There was also enemy submarine activity in the early part of the journey and although the Oronsay herself was not affected, other ships were attacked.

Charles Aves remembered:

"Our voyage was ghastly, made worse by the over-crowded conditions along with sea-sickness and terrible food. We docked at Freetown to re-supply and re-fuel, but we were not allowed ashore. Later we docked at Durban in South Africa, where we did enjoy a few days leave. Then we changed ship and finished the journey to India aboard the HMS Andes. We arrived at Bombay on the 21st January 1942 and I was immediately struck by the poverty and the beggars; we certainly saw some awful sights."

The King's were posted to Secunderabad, arriving there by train on the 31st January and took up residence at the Gough Barracks in the old Cantonment section of the town. These barracks were to be the 13th King's home for several months, during which time they performed garrison and policing duties in the local area. According to the diaries of Pte. Leon Frank, a good friend of Charles Aves, the battalion also spent some time at the Meadows Barracks which also formed part of the Secunderabad Cantonment at that time.

Seen below are some photographs in relation to the first part of this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

The audio memoir of Charles Aves is available at the Imperial War Museum and it is from this recorded testimony, that most of the information written here is taken. Charles made great efforts throughout his post-war life to record, whether verbally, or indeed in writing, his thoughts and feelings in regards to his WW2 experience. His is an extremely valuable viewpoint, as it comes from a man who was conscripted to serve and had expressed his doubts about the validity of the war.

To listen to his full audio memoir, please click on the following link:

www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80015020

Charles recalled:

"In 1939 things were very confused at home and in the press and I was not sure whether we should be going to war, but I was conscripted into the Army in September 1940 and sent to Jordan Hill College Barracks up at Glasgow and joined 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment. I arrived by train at Glasgow on the 13th September, being dropped off on platform 13 and then being placed into Platoon 13 of the 13th King’s. 13 was to become my lucky number."

Over the following 12 months, Pte. Aves completed his initial infantry training at Glasgow and then joined the King's as they travelled down south to take up their new role, as a coastal defence battalion patrolling the coastline towns of Essex and Suffolk. In late 1941, the 13th King's were told to prepare for a posting overseas and journeyed up to Liverpool on the 6th December, with orders to board the troopship Oronsay which was anchored at the Alexandria Docks on the River Mersey. Unbeknown to the King's, they were bound for India and began an eight week voyage on the 8th December 1941, which would take them around the Cape of Good Hope.

There were over 3000 men aboard the troopship and conditions were very cramped for the Other ranks, who shared the hot and claustrophobic lower decks. As with all convoy experiences in WW2, sea-sickness was a severe problem for many of the men, especially in those early days of the voyage as the ships passed through the rougher north Atlantic waters. There was also enemy submarine activity in the early part of the journey and although the Oronsay herself was not affected, other ships were attacked.

Charles Aves remembered:

"Our voyage was ghastly, made worse by the over-crowded conditions along with sea-sickness and terrible food. We docked at Freetown to re-supply and re-fuel, but we were not allowed ashore. Later we docked at Durban in South Africa, where we did enjoy a few days leave. Then we changed ship and finished the journey to India aboard the HMS Andes. We arrived at Bombay on the 21st January 1942 and I was immediately struck by the poverty and the beggars; we certainly saw some awful sights."

The King's were posted to Secunderabad, arriving there by train on the 31st January and took up residence at the Gough Barracks in the old Cantonment section of the town. These barracks were to be the 13th King's home for several months, during which time they performed garrison and policing duties in the local area. According to the diaries of Pte. Leon Frank, a good friend of Charles Aves, the battalion also spent some time at the Meadows Barracks which also formed part of the Secunderabad Cantonment at that time.

Seen below are some photographs in relation to the first part of this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

During his time with the 13th King's at Secunderabad, Charles enjoyed performing with the Battalion Military Band. Apart from the obvious musical duties on state and military occasions, the band was an integral part of the battalion's social scene, playing at local dances and concerts. Charles benefitted from being a member of the band, where he played various musical instruments including the piano accordion. He acknowledged that he was treated rather well by officers because of his musical talents and often received extra privileges as a consequence, including time away from the garrison and of course access to better food and beverages.

By the beginning of May 1942, stories began to circulate throughout India, that a man they called Wingate of Abyssinia had been summoned by Commander in Chief Archibald Wavell to fashion a new and rather unique fighting force. Charles Aves remembered his first impressions of Wingate, after the realisation that the King's battalion were going to be heavily involved with this new and revolutionary innovation called Long Range Penetration.

"Wingate was an extraordinary man, with an aura of power. He realigned the perception of what was possible from ordinary soldiers like ourselves. I thought he was a great man. We took a train to Patharia in the Central Provinces, where the jungle was supposed to be similar to that of Burma. Training was severe, with long days of marching, camping out under the stars and many river crossings; and all this without adequate food. Then the monsoon began and we were never dry, night or day.”

To read more about Chindit training at Patharia, please click on the following link: Voyage and Training

Pte. Aves was placed into Chindit column No. 7 at Patharia under the overall command of Major Kenneth Gilkes. Charles, in his early twenties was one of the younger men in the King's battalion and so stood up much better to the rigours of jungle warfare training.

“It was quite exciting and I looked upon it all as a bit of an adventure, I seemed to be able to cope with the strains and the hardships, although I had not had a particularly tough upbringing back in London, however, I did fall foul to malaria in August 1942."

Around the time that Charles contracted malaria, the whole battalion was suffering badly from the exertions and trials of Chindit training and at one point over half the men were categorised as unfit to continue. There were also several casualties incurred, with incidents of men drowning in the swollen and treacherous rivers, other men succumbing to diseases such as malaria and dysentery and even accidents involving firearms and other weaponry. Charles Aves remembered one such incident in regards the death of Lt. Neville Saffer of the King's in early August 1942:

"We had the affair of an officer being shot by a private soldier during arms inspection. When you have an inspection you are supposed to clear the breach, presumably he forgot to instruct the men of this and the weapon was fired and he was killed. He was a Jewish officer named Saffer, a very nice man, he died in these circumstances without ever seeing the enemy. Things, as you can see could be very tough."

Another member of 7 Column, Charles' friend Pte. Leon Frank also remembered the day Lieutenant Saffer was killed:

"We trained in mud, we slept in mud and we ate mud. The training was very tough. We did river crossings, marching through the jungle, finding our way by the stars, it was part of the Commando training. We had one very sad thing that happened there. There was a Jewish Officer named Lt. Neville Nathan Saffer. My platoon was 13 Platoon and next to me was 14 Platoon, a few yards from each other, and we were each standing in a small circle for rifle inspection.

You bring your rifle to the up position, first ejecting all your shells, and the officer in charge of the inspection would come round and look down the rifle barrel to see if it was clean. We had almost completed our inspection when all of a sudden a shot rang out. We turned round at 14 Platoon. Lt. Saffer, the inspecting officer, had looked down the barrel of the rifle and the soldier concerned had left one shell in the breach. He pulled the trigger as the officer looked down the barrel and the bullet took him right through the cheek and out of the back of his head. He dropped like a stack. He was dead instantly.

That was our first casualty and we were very shocked. Everyone was shocked. I think the soldier who did it had to be put in hospital. It was an accident - carelessness yes, but nevertheless an accident. We buried him and we put a cross above his grave with a Star of David drawn on to signify his Jewish faith. That was a sad incident."

To read more about Lt. Saffer's death some of the other men who died during Chindit training, please click on the following link:

Men Who Died During Training

Charles Aves continues:

"My platoon commander was Captain David Hastings, a true officer and a gentleman, he was a very fine man and always treated us ordinary soldiers with respect. Not all of our officers were of the same calibre and many disliked Wingate and his theories immensely. After a short time in Patharia, those of us from the battalion who wholeheartedly embraced Wingate's doctrines began to call ourselves 'Pukka Kings.' Those who we felt were malingerers and attempted to get out of doing Chindit duties, we called 'Jossers.' I was quite surprised one day around Christmas time, to be approached by Wingate, who asked me if I would like to provide the musical accompaniment for an outdoor religious service he was conducting at our latest camp at Saugor. He must have heard about my playing of the piano accordion, which I was amazed to learn had been brought up to Saugor from our barracks at Secunderabad."

Seen below is another gallery of images, showing some of the men featured in this section of Charles Aves' story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

By the beginning of May 1942, stories began to circulate throughout India, that a man they called Wingate of Abyssinia had been summoned by Commander in Chief Archibald Wavell to fashion a new and rather unique fighting force. Charles Aves remembered his first impressions of Wingate, after the realisation that the King's battalion were going to be heavily involved with this new and revolutionary innovation called Long Range Penetration.

"Wingate was an extraordinary man, with an aura of power. He realigned the perception of what was possible from ordinary soldiers like ourselves. I thought he was a great man. We took a train to Patharia in the Central Provinces, where the jungle was supposed to be similar to that of Burma. Training was severe, with long days of marching, camping out under the stars and many river crossings; and all this without adequate food. Then the monsoon began and we were never dry, night or day.”

To read more about Chindit training at Patharia, please click on the following link: Voyage and Training

Pte. Aves was placed into Chindit column No. 7 at Patharia under the overall command of Major Kenneth Gilkes. Charles, in his early twenties was one of the younger men in the King's battalion and so stood up much better to the rigours of jungle warfare training.

“It was quite exciting and I looked upon it all as a bit of an adventure, I seemed to be able to cope with the strains and the hardships, although I had not had a particularly tough upbringing back in London, however, I did fall foul to malaria in August 1942."

Around the time that Charles contracted malaria, the whole battalion was suffering badly from the exertions and trials of Chindit training and at one point over half the men were categorised as unfit to continue. There were also several casualties incurred, with incidents of men drowning in the swollen and treacherous rivers, other men succumbing to diseases such as malaria and dysentery and even accidents involving firearms and other weaponry. Charles Aves remembered one such incident in regards the death of Lt. Neville Saffer of the King's in early August 1942:

"We had the affair of an officer being shot by a private soldier during arms inspection. When you have an inspection you are supposed to clear the breach, presumably he forgot to instruct the men of this and the weapon was fired and he was killed. He was a Jewish officer named Saffer, a very nice man, he died in these circumstances without ever seeing the enemy. Things, as you can see could be very tough."

Another member of 7 Column, Charles' friend Pte. Leon Frank also remembered the day Lieutenant Saffer was killed:

"We trained in mud, we slept in mud and we ate mud. The training was very tough. We did river crossings, marching through the jungle, finding our way by the stars, it was part of the Commando training. We had one very sad thing that happened there. There was a Jewish Officer named Lt. Neville Nathan Saffer. My platoon was 13 Platoon and next to me was 14 Platoon, a few yards from each other, and we were each standing in a small circle for rifle inspection.

You bring your rifle to the up position, first ejecting all your shells, and the officer in charge of the inspection would come round and look down the rifle barrel to see if it was clean. We had almost completed our inspection when all of a sudden a shot rang out. We turned round at 14 Platoon. Lt. Saffer, the inspecting officer, had looked down the barrel of the rifle and the soldier concerned had left one shell in the breach. He pulled the trigger as the officer looked down the barrel and the bullet took him right through the cheek and out of the back of his head. He dropped like a stack. He was dead instantly.

That was our first casualty and we were very shocked. Everyone was shocked. I think the soldier who did it had to be put in hospital. It was an accident - carelessness yes, but nevertheless an accident. We buried him and we put a cross above his grave with a Star of David drawn on to signify his Jewish faith. That was a sad incident."

To read more about Lt. Saffer's death some of the other men who died during Chindit training, please click on the following link:

Men Who Died During Training

Charles Aves continues:

"My platoon commander was Captain David Hastings, a true officer and a gentleman, he was a very fine man and always treated us ordinary soldiers with respect. Not all of our officers were of the same calibre and many disliked Wingate and his theories immensely. After a short time in Patharia, those of us from the battalion who wholeheartedly embraced Wingate's doctrines began to call ourselves 'Pukka Kings.' Those who we felt were malingerers and attempted to get out of doing Chindit duties, we called 'Jossers.' I was quite surprised one day around Christmas time, to be approached by Wingate, who asked me if I would like to provide the musical accompaniment for an outdoor religious service he was conducting at our latest camp at Saugor. He must have heard about my playing of the piano accordion, which I was amazed to learn had been brought up to Saugor from our barracks at Secunderabad."

Seen below is another gallery of images, showing some of the men featured in this section of Charles Aves' story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

In mid-January 1943, 77th Brigade moved up to Imphal in Assam and made their final preparations for the forthcoming expedition into Burma. Pte. Aves recalled:

"First we left Saugor by train to Comilla, then on to Dimapur. After this we marched at night to Kohima through the most beautiful scenery I have ever seen. We then camped at Imphal and awaited our final orders before marching down to the Chindwin River. My best pal, Stan Allnutt was one of the men sent on pre-operational reconnaissance into Burma in January. Stan had taken the time to learn some useful Burmese phrases and this was probably why he was chosen for this short trip over the Chindwin. After he came back he taught me many of these words and phrases. No one was afraid when we first went into Burma, it was all an adventure and we were confident we could deal with the jungle at least.

After a week or so Wingate made plans to attack a Japanese garrison at a place called Pinlebu, but this was called off. A while later, I remember Major Gilkes was chastised by Wingate for setting camp at the foot of a small hill instead of on top of it; Wingate explained that we would be vulnerable to enemy mortar fire if we camped in the lower ground. Not much more happened during the next few weeks. When I look back on those days now, I realise I was very fortunate to be one of the lucky men who avoided direct contact with the Japanese during the outward journey across Burma.

We finally arrived at the Irrawaddy and my own personal view was, if we crossed over now, we might as well be in Japan proper. But cross we did, just north of a town called Inywa. By this time fatigue had set in with some of our men, many were beginning to fall ill, including my friend Stan Allnutt. Fortunately, after a few days on the east side of the river, Brigadier Wingate decided it was time to return to India."

To begin the long journey home Wingate, along with columns 7 & 8 decided to return to the area around Inywa, with the view that the Japanese would not expect them to re-cross the river so close to where they had previously come over. In the early hours of the 29th March, two platoons from 7 Column were chosen to cross the river and to secure a bridgehead for the rest of the Brigade. Charles Aves found himself in the third boat to cross.

"First we left Saugor by train to Comilla, then on to Dimapur. After this we marched at night to Kohima through the most beautiful scenery I have ever seen. We then camped at Imphal and awaited our final orders before marching down to the Chindwin River. My best pal, Stan Allnutt was one of the men sent on pre-operational reconnaissance into Burma in January. Stan had taken the time to learn some useful Burmese phrases and this was probably why he was chosen for this short trip over the Chindwin. After he came back he taught me many of these words and phrases. No one was afraid when we first went into Burma, it was all an adventure and we were confident we could deal with the jungle at least.

After a week or so Wingate made plans to attack a Japanese garrison at a place called Pinlebu, but this was called off. A while later, I remember Major Gilkes was chastised by Wingate for setting camp at the foot of a small hill instead of on top of it; Wingate explained that we would be vulnerable to enemy mortar fire if we camped in the lower ground. Not much more happened during the next few weeks. When I look back on those days now, I realise I was very fortunate to be one of the lucky men who avoided direct contact with the Japanese during the outward journey across Burma.

We finally arrived at the Irrawaddy and my own personal view was, if we crossed over now, we might as well be in Japan proper. But cross we did, just north of a town called Inywa. By this time fatigue had set in with some of our men, many were beginning to fall ill, including my friend Stan Allnutt. Fortunately, after a few days on the east side of the river, Brigadier Wingate decided it was time to return to India."

To begin the long journey home Wingate, along with columns 7 & 8 decided to return to the area around Inywa, with the view that the Japanese would not expect them to re-cross the river so close to where they had previously come over. In the early hours of the 29th March, two platoons from 7 Column were chosen to cross the river and to secure a bridgehead for the rest of the Brigade. Charles Aves found himself in the third boat to cross.

Once again Pte. Aves takes up the story:

As quietly as possible, we made our way to the small boats at the bank of the river where boatmen had been paid to ferry us across. I think I was in the second or third boat. We proceeded across the river and it seemed ages getting across. I suppose there were eight or ten of us in the boat. Just as we and a couple of other boats reached the bank, the Japs opened up with mortar and automatic fire from a point some few hundred yards north of our landing. We couldn't see them, for they were well concealed in a copse.

We scrambled ashore to find the Lieutenant and a few men from the first boat standing around. I shall never forget the Lieutenant, he was eating cheese from a tin with a penknife, quite unconcerned about the firing which was directed on to the boats trying to get over, and also at our troops on the other side. Contrary to what has been written before, we were not under heavy fire on the west bank and the Japs did not have control of this area. I firmly believe that it must have been only a patrol of Japs with a mortar unit and automatic fire. Perhaps also with a sniper. I can vouch for the fact that we were not fired at on the bank.

For some reason the Lieutenant decided that I would attack the enemy position. He told me to make my way across an open paddy field to a point some two hundred yards away and direct some grenades on to the Japs wherever they were. I looked at him in disbelief. I couldn't see the enemy, I had never used a grenade launcher, I only had two grenades and no launcher attachment. I told him this, but he found a launcher and told me to just fix it on the end of the rifle.

I was completely in the open as I crossed this paddy field; had there been any Japs looking they could have mown me down easily. I made myself as small as possible and safely reached the point from whence the fire came. What was I to attack? I couldn't see anything. There was no firing at this time. Just a small forest of trees. I decided to return and ask for further instructions. When I got back to the main group I found them forming up to move off. Had the Japs been any stronger I am sure they could have attacked us.

The total number of men that formed up was sixty-five. There was Captain Oakes, Lieutenant Jelliss, the second Lieutenant who sent me to explore the Jap position, two or three Sergeants, some Corporals and about fifty other ranks. I asked what happened to Captain Hastings, who had been my platoon officer until he was promoted to Column Adjutant. I was told that the boat he was in had been hit and he was flung into the river and swept away.

In retrospect we could say that had we attacked the Jap unit it is possible that the rest of Wingate's force could have crossed reasonably safely, but I don't know what orders our senior officers had. I believe we had no means of signalling across the river and at this time most of the men were ill and short of food. The sixty-five of us who had crossed the river moved quickly away and a few miles later made camp in dense jungle. This was the rendezvous point for those who had crossed the river, but by the morning no one else had turned up. We waited another day and then our officers led us off towards the Chindwin.

NB. From looking through the 13th King's War diaries for 1943, it seems likely that the 2nd Lieutenant mentioned by Charles Aves, was John Thomas Kelly formerly of the Border Regiment.

Captain Oakes, our senior officer, had maps so we knew where we were going, but we were very short of food. It was decided to make for a village where we hoped to obtain some rice and a little rock salt. After a couple of days we came to a village, a friendly one we hoped, without any Jap troops nearby. We each obtained a wedge of cooked rice within a large banana leaf envelope. The rice was delicious. The Burmese have a way of presenting boiled rice like I have never tasted since. We ate half of this and went on our way.

A number of men were feeling pretty bad by now and a particular friend of mine, Freddy Raffo, said to me, I'm not going to make it, I can't go on any more.' I knew Fred wasn't married, but he had an elderly mother who lived alone in a small house in Salford. I said, 'You can't give up Freddy, it's all right for you, but what about your mother, all on her own waiting for you, you've got to make it for her sake.' We split up all his equipment and took his rifle and carried it all for him. I am glad to say Fred did get out and he thanked me later for saying what I did at the time.

We made our way slowly for another day and at about 1 p.m. the officers decided we would have a rest and a brew-up. We flung our weary limbs down in the dried bed of a river. Two men were posted as sentries and we took off our packs, laid down our rifles and made some tea. I was with Corporal Stan Hickman; I did not know him very well, but he was a good chap, who came from South London. We were relaxing and completely off guard when suddenly we heard the sound of footsteps running through the trees. Looking up we saw the two sentries running for their lives past us. They didn't say anything, but at the same time we heard shots being fired and shouts from some twenty yards away. I went to run, for everyone else had gone, but Corporal Hickman said 'No, don't go.' I stayed with him and then we saw them, about fifteen yards away, coming at us.

We moved like lightning, carrying only our rifles. We ran up the nullah and as we did so we both picked up a pack which had been left by others from our party. We broke the speed record and managed to climb up behind some rocks; there were a few of our party there and we poured rifle fire on where the Japs were coming from. After a while we ceased fire. We couldn't see the Japs, but we could hear them shouting to each other. I think they must have been looting all the packs we had left behind.

We withdrew up the hill and then sorted ourselves out. There was Lieutenant Jelliss, two Sergeants, Corporal Hickman and seven other men. Corporal Hickman and I looked into the two packs we had picked up; mine had belonged to Captain Oakes and contained all the maps for the route back to the Chindwin. In the other which belonged to the young Lieutenant was a quantity of silver rupees. We then found that we only had two water bottles between us. We went back to the site of the attack, but the Japs were still there, so we took off west as fast as we could without a stop for two hours."

Another man present at the time of the Japanese ambush, was Pte. Robert Hyner of 14 Platoon. For another perspective on the above incident and more information about Hyner's similar Chindit journey to that of Charles Aves, please click on the following link: Robert Valentine Hyner

Shown below is another Gallery of images in relation to this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

As quietly as possible, we made our way to the small boats at the bank of the river where boatmen had been paid to ferry us across. I think I was in the second or third boat. We proceeded across the river and it seemed ages getting across. I suppose there were eight or ten of us in the boat. Just as we and a couple of other boats reached the bank, the Japs opened up with mortar and automatic fire from a point some few hundred yards north of our landing. We couldn't see them, for they were well concealed in a copse.

We scrambled ashore to find the Lieutenant and a few men from the first boat standing around. I shall never forget the Lieutenant, he was eating cheese from a tin with a penknife, quite unconcerned about the firing which was directed on to the boats trying to get over, and also at our troops on the other side. Contrary to what has been written before, we were not under heavy fire on the west bank and the Japs did not have control of this area. I firmly believe that it must have been only a patrol of Japs with a mortar unit and automatic fire. Perhaps also with a sniper. I can vouch for the fact that we were not fired at on the bank.

For some reason the Lieutenant decided that I would attack the enemy position. He told me to make my way across an open paddy field to a point some two hundred yards away and direct some grenades on to the Japs wherever they were. I looked at him in disbelief. I couldn't see the enemy, I had never used a grenade launcher, I only had two grenades and no launcher attachment. I told him this, but he found a launcher and told me to just fix it on the end of the rifle.

I was completely in the open as I crossed this paddy field; had there been any Japs looking they could have mown me down easily. I made myself as small as possible and safely reached the point from whence the fire came. What was I to attack? I couldn't see anything. There was no firing at this time. Just a small forest of trees. I decided to return and ask for further instructions. When I got back to the main group I found them forming up to move off. Had the Japs been any stronger I am sure they could have attacked us.

The total number of men that formed up was sixty-five. There was Captain Oakes, Lieutenant Jelliss, the second Lieutenant who sent me to explore the Jap position, two or three Sergeants, some Corporals and about fifty other ranks. I asked what happened to Captain Hastings, who had been my platoon officer until he was promoted to Column Adjutant. I was told that the boat he was in had been hit and he was flung into the river and swept away.

In retrospect we could say that had we attacked the Jap unit it is possible that the rest of Wingate's force could have crossed reasonably safely, but I don't know what orders our senior officers had. I believe we had no means of signalling across the river and at this time most of the men were ill and short of food. The sixty-five of us who had crossed the river moved quickly away and a few miles later made camp in dense jungle. This was the rendezvous point for those who had crossed the river, but by the morning no one else had turned up. We waited another day and then our officers led us off towards the Chindwin.

NB. From looking through the 13th King's War diaries for 1943, it seems likely that the 2nd Lieutenant mentioned by Charles Aves, was John Thomas Kelly formerly of the Border Regiment.

Captain Oakes, our senior officer, had maps so we knew where we were going, but we were very short of food. It was decided to make for a village where we hoped to obtain some rice and a little rock salt. After a couple of days we came to a village, a friendly one we hoped, without any Jap troops nearby. We each obtained a wedge of cooked rice within a large banana leaf envelope. The rice was delicious. The Burmese have a way of presenting boiled rice like I have never tasted since. We ate half of this and went on our way.

A number of men were feeling pretty bad by now and a particular friend of mine, Freddy Raffo, said to me, I'm not going to make it, I can't go on any more.' I knew Fred wasn't married, but he had an elderly mother who lived alone in a small house in Salford. I said, 'You can't give up Freddy, it's all right for you, but what about your mother, all on her own waiting for you, you've got to make it for her sake.' We split up all his equipment and took his rifle and carried it all for him. I am glad to say Fred did get out and he thanked me later for saying what I did at the time.

We made our way slowly for another day and at about 1 p.m. the officers decided we would have a rest and a brew-up. We flung our weary limbs down in the dried bed of a river. Two men were posted as sentries and we took off our packs, laid down our rifles and made some tea. I was with Corporal Stan Hickman; I did not know him very well, but he was a good chap, who came from South London. We were relaxing and completely off guard when suddenly we heard the sound of footsteps running through the trees. Looking up we saw the two sentries running for their lives past us. They didn't say anything, but at the same time we heard shots being fired and shouts from some twenty yards away. I went to run, for everyone else had gone, but Corporal Hickman said 'No, don't go.' I stayed with him and then we saw them, about fifteen yards away, coming at us.

We moved like lightning, carrying only our rifles. We ran up the nullah and as we did so we both picked up a pack which had been left by others from our party. We broke the speed record and managed to climb up behind some rocks; there were a few of our party there and we poured rifle fire on where the Japs were coming from. After a while we ceased fire. We couldn't see the Japs, but we could hear them shouting to each other. I think they must have been looting all the packs we had left behind.

We withdrew up the hill and then sorted ourselves out. There was Lieutenant Jelliss, two Sergeants, Corporal Hickman and seven other men. Corporal Hickman and I looked into the two packs we had picked up; mine had belonged to Captain Oakes and contained all the maps for the route back to the Chindwin. In the other which belonged to the young Lieutenant was a quantity of silver rupees. We then found that we only had two water bottles between us. We went back to the site of the attack, but the Japs were still there, so we took off west as fast as we could without a stop for two hours."

Another man present at the time of the Japanese ambush, was Pte. Robert Hyner of 14 Platoon. For another perspective on the above incident and more information about Hyner's similar Chindit journey to that of Charles Aves, please click on the following link: Robert Valentine Hyner

Shown below is another Gallery of images in relation to this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Charles Aves' memoir concludes:

"As night fell, we took stock. We all had rifles, ammunition and grenades, but no food and little water. The Lieutenant (Jelliss) was a good officer who decided to involve us all in decisions if needed. We had another bonus, me, as I was the only one who could speak any Burmese, thanks to the teachings of Stan Allnutt. Anyone can make themselves understood in their quest for food, but I was able to ask the villagers for the Headman and for the position of the nearest Japanese. In the morning we decided to make for the nearest village. We learned a lot about ourselves during this period. We enjoyed being in the jungle, the thicker the better, here we felt safe. We could find paths among the undergrowth, however indistinct and we knew that they would eventually lead to water or a village. We were a good team all in all and got on fairly well.

The first village was quite near and I went in first with Lieutenant Jelliss, while the others kept a look out. The villagers were very friendly and helpful, all smiles and generosity. In fact our experience showed all the Burmese to be very helpful, with one exception; I can't recall the name of the village, but shall call it Maungde. We had travelled quite a few miles, probably about twenty each day, when came upon Maungde. We knew this village was different to all the others, we could tell straight away that there was something wrong. The Headman was uneasy; we always watched out to see whether anyone disappeared when we entered a village and it seemed to us one or two shifty characters had moved out of sight.

We didn't hesitate, we left straight away, no messing. We didn't give them a chance to call on any Japs, we shot through like lightning, and disappeared over the horizon with no casualties. It eventually transpired that some of the other men from our original group were betrayed when they went through the same village and a number of them were killed by enemy fire. We were eventually picked up by a patrol of Seaforth Highlanders at the Chindwin and taken by boat to the western banks and then on to Tamu. We were then taken to Imphal by lorry and into hospital. I immediately fell down with malaria. We were nursed back to health by Matron McGearey at Imphal and were even visited by the Brigadier. It took over three months for me to recover physically from Operation Longcloth. Shortly after leaving hospital I was asked if I would like to send a message home to my family, but not by letter, by film!"

NB. Charles is referring here to the Army Film initiative named Calling Blighty. Messages were recorded from men serving in India and Burma and then shown at cinemas back home. For more information and to view some of these film messages, please click on the following link:

www.nwfa.mmu.ac.uk/blighty/index.php

So what happened to the men that befriended Charles Aves during his time in India and Burma in 1942/43. Here are just a few of those soldiers mentioned in his story so far:

Pte. Stanley Allnutt was a top marksman with C' Company of the 13th King's during the years of WW2. He took the trouble to learn Burmese and was one of the other ranks chosen for the pre-operational reconnaissance patrol in January 1943, led by Captain D.C. Herring. Stanley got out of Burma in 1943 via the Chinese Yunnan Borders and returned to the 13th King's at their new base in Karachi.

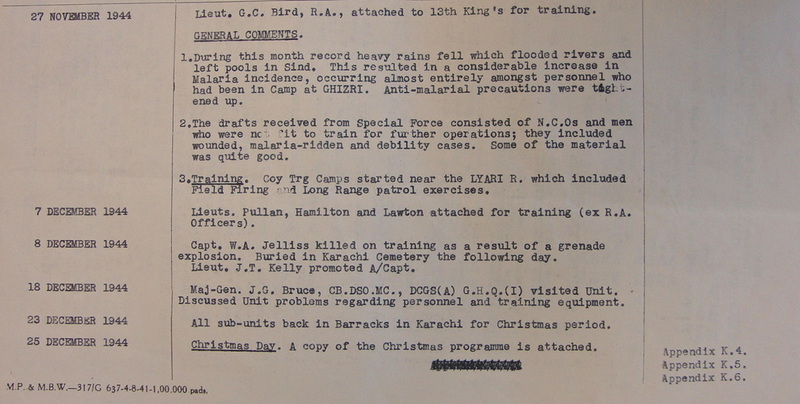

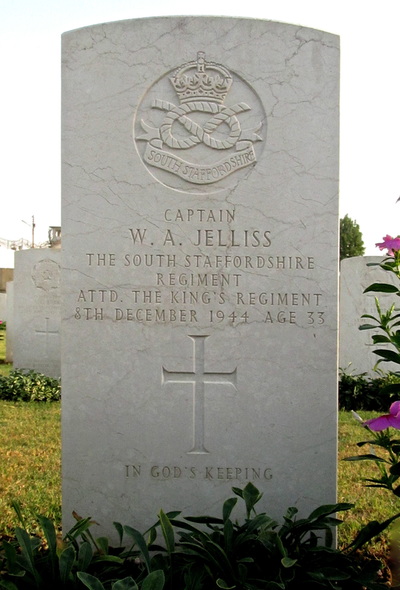

Captain 204373 William Alfred Jelliss formerly of the South Staffordshire Regiment. Joined the 13th King's on the 11th November 1942 at the Bharon Camp in the Central Provinces of India. Charles Aves recalled that Captain Jelliss seemed very distracted and unhappy immediately after Operation Longcloth and would not acknowledge the men he had led back to India. This seemed very strange to Charles, as he and William Jelliss had often talked about having a wonderful slap up meal once they had returned.

Sadly, it transpired that William's wife had sent him a Dear John letter, which was waiting for him at the Napier Barracks on his return from Burma. He was rather badly affected by the devastating news contained within the letter. Captain Jelliss was tragically killed on the 8th December 1944, as the result of an accident whilst handling a grenade during a training exercise. He was buried at Karachi War Cemetery.

To view William Jelliss' CWGC details, please click on the following link:

www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2178315/JELLISS,%20WILLIAM%20ALFRED

Pte. Richard Mannion of the 13th King's. This soldier was a very good friend of Charles Aves and introduced him to the joys of the operatic arias. Pte. Mannion also exited Burma via Yunnan Province in 1943.

Pte. Frederick Raffo, from Salford near Manchester, was a soldier with the 13th King's and a star in the Company football team in India. Back at the Secunderabad Cantonment in 1942, Fred was batman to Lt. Leslie Cottrell, an officer with the King's and Adjutant for 7 Column on Operation Longcloth.

"As night fell, we took stock. We all had rifles, ammunition and grenades, but no food and little water. The Lieutenant (Jelliss) was a good officer who decided to involve us all in decisions if needed. We had another bonus, me, as I was the only one who could speak any Burmese, thanks to the teachings of Stan Allnutt. Anyone can make themselves understood in their quest for food, but I was able to ask the villagers for the Headman and for the position of the nearest Japanese. In the morning we decided to make for the nearest village. We learned a lot about ourselves during this period. We enjoyed being in the jungle, the thicker the better, here we felt safe. We could find paths among the undergrowth, however indistinct and we knew that they would eventually lead to water or a village. We were a good team all in all and got on fairly well.

The first village was quite near and I went in first with Lieutenant Jelliss, while the others kept a look out. The villagers were very friendly and helpful, all smiles and generosity. In fact our experience showed all the Burmese to be very helpful, with one exception; I can't recall the name of the village, but shall call it Maungde. We had travelled quite a few miles, probably about twenty each day, when came upon Maungde. We knew this village was different to all the others, we could tell straight away that there was something wrong. The Headman was uneasy; we always watched out to see whether anyone disappeared when we entered a village and it seemed to us one or two shifty characters had moved out of sight.

We didn't hesitate, we left straight away, no messing. We didn't give them a chance to call on any Japs, we shot through like lightning, and disappeared over the horizon with no casualties. It eventually transpired that some of the other men from our original group were betrayed when they went through the same village and a number of them were killed by enemy fire. We were eventually picked up by a patrol of Seaforth Highlanders at the Chindwin and taken by boat to the western banks and then on to Tamu. We were then taken to Imphal by lorry and into hospital. I immediately fell down with malaria. We were nursed back to health by Matron McGearey at Imphal and were even visited by the Brigadier. It took over three months for me to recover physically from Operation Longcloth. Shortly after leaving hospital I was asked if I would like to send a message home to my family, but not by letter, by film!"

NB. Charles is referring here to the Army Film initiative named Calling Blighty. Messages were recorded from men serving in India and Burma and then shown at cinemas back home. For more information and to view some of these film messages, please click on the following link:

www.nwfa.mmu.ac.uk/blighty/index.php

So what happened to the men that befriended Charles Aves during his time in India and Burma in 1942/43. Here are just a few of those soldiers mentioned in his story so far:

Pte. Stanley Allnutt was a top marksman with C' Company of the 13th King's during the years of WW2. He took the trouble to learn Burmese and was one of the other ranks chosen for the pre-operational reconnaissance patrol in January 1943, led by Captain D.C. Herring. Stanley got out of Burma in 1943 via the Chinese Yunnan Borders and returned to the 13th King's at their new base in Karachi.

Captain 204373 William Alfred Jelliss formerly of the South Staffordshire Regiment. Joined the 13th King's on the 11th November 1942 at the Bharon Camp in the Central Provinces of India. Charles Aves recalled that Captain Jelliss seemed very distracted and unhappy immediately after Operation Longcloth and would not acknowledge the men he had led back to India. This seemed very strange to Charles, as he and William Jelliss had often talked about having a wonderful slap up meal once they had returned.

Sadly, it transpired that William's wife had sent him a Dear John letter, which was waiting for him at the Napier Barracks on his return from Burma. He was rather badly affected by the devastating news contained within the letter. Captain Jelliss was tragically killed on the 8th December 1944, as the result of an accident whilst handling a grenade during a training exercise. He was buried at Karachi War Cemetery.

To view William Jelliss' CWGC details, please click on the following link:

www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2178315/JELLISS,%20WILLIAM%20ALFRED

Pte. Richard Mannion of the 13th King's. This soldier was a very good friend of Charles Aves and introduced him to the joys of the operatic arias. Pte. Mannion also exited Burma via Yunnan Province in 1943.

Pte. Frederick Raffo, from Salford near Manchester, was a soldier with the 13th King's and a star in the Company football team in India. Back at the Secunderabad Cantonment in 1942, Fred was batman to Lt. Leslie Cottrell, an officer with the King's and Adjutant for 7 Column on Operation Longcloth.

After a lengthy period of recuperation, Charles Aves re-joined his comrades from the 13th Battalion, the King's Regiment at their new base within the Napier Barracks at Karachi. It was here in March 1944 that he heard the tragic news of Wingate’s death. He later recalled:

“As a private soldier who knew him, I was proud to be associated with him and his theories in war. He was fearless, unorthodox, brilliant and yet human. Our feelings on hearing of his death were of personal shock and grief. He was a great soldier."

With the invaluable experience he had gained in 1943, Charles was considered an ideal candidate for the second Chindit expedition and along with many other Longcloth veterans was interviewed by Colonel Scott. However, even with the promise of a promotion in the ranks, Charles decided not to volunteer again.

“I wasn’t a regular soldier, I was a conscript. I felt I had done everything that had been asked of me in 1943. I was not ashamed of anything that had happened, my training had served me well and I felt I had done my bit.”

In 1945, Pte. Aves was transferred to the Border Regiment and went into Burma for a second time. It was during this period that he learned to his great relief that the Atom Bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki had ended the war. It is clear from listening to his Imperial War audio, that Charles was rather upset and disappointed by the way that the 13th King's performance in 1943 has been portrayed as second rate, within the pages of the many books and histories written on the subject since the war.

Pte. Charles Aves, by giving his testimony in such an honest and frank way, has provided an important insight into the feelings and emotions of the ordinary private soldier, who was thrust into war against a formidable and ferocious enemy. The emotion in his voice is very apparent when he talks through the last few minutes of his audio memoir and recounts the men with whom he served in 1943:

"I would like to dedicate these memoirs; they are not complete, but I think there is sufficient there to state my own position. I would like to dedicate them to my friends from that time.

Dick Mannion, who introduced me to many of the great tenor operatic arias and shared the monsoons with me. Freddy Raffo, a great footballer, and the first northerner to offer me friendship. Stan Allnutt, who remained a friend all through and helped me with his (Burmese) linguistic skills. David Ogden, tenor saxophonist from Irlam and Cadishead, patient, tolerant, logical and deep thinking, I always hoped some of that rubbed off on me. David Hastings, Captain, killed in the Irrawaddy crossing, my first experience in meeting an officer and a gentleman.

Smudger Smith, an honourable private, a dustman in real life. One of the eleven who stayed and didn't run. Extremely religious and helped us each day with a verse from the bible. A very kind man. Corporal Bert Fitton, left-half company football team, helped Lt.-Colonel Cooke and the sick and the wounded into the only get out plane. Found himself locked in and about to take off, pleaded with the pilot to let him out. I wonder if his family ever knew about that? I was on patrol with him once, just he and I. He was too brave for me and I had tears when I heard of his death.

There are many more now I come to think of it. But we will finish with Corporal Stan Hickman, who stopped me running away when he said don't go. I've always been pleased that I did not run away, but it really wasn't my fault. Stan Hickman was good man to be with."

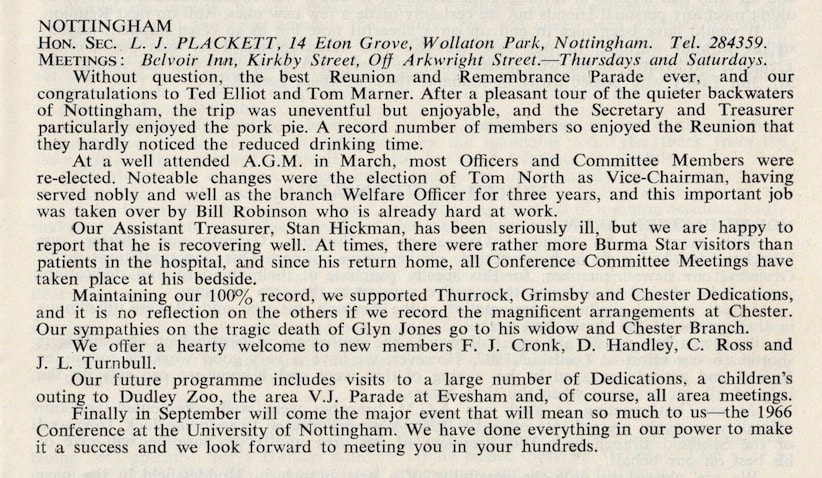

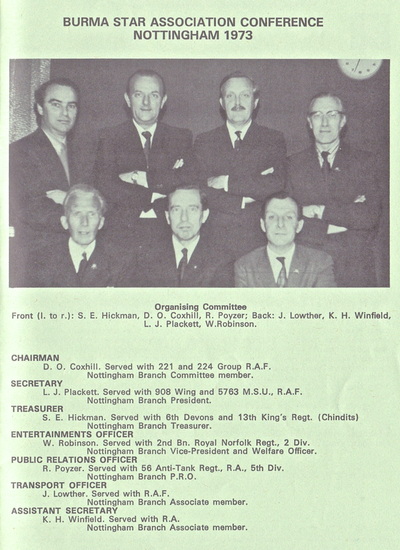

Stan Hickman's death was recorded in the Spring 1974 edition of the Burma Star Association magazine, Dekho. Alongside the entry for his passing was this short obituary:

Stan, who was the Treasurer of our Nottingham Branch and formerly a Chindit with the 13th Battalion, the King's (Liverpool) Regiment was one of our mainsprings, especially during the conferences of 1966 and 1973. In all of his work for the branch and the wider Association he was meticulous and inspiring.

One BSA official will not forget how, when lost in Nottingham on the occasion of the last conference, telephoned Stan for help and directions. An immensely cheerful character supplied the desired information and it was only at the end of the conversation that the caller realised that Stan was speaking from his sick-bed! We salute him for his continued support right to last and also thank his wife, Joan.

Shown below is a final gallery of images in relation to this story including a photograph of Charles Aves with his pals from the 13th King's, Leon Frank and Bert Jacobs. This photograph was probably taken whilst the battalion were stationed at Secunderabad in early 1942. According to Charles, the man behind the camera was Pte. Dick Mannion. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

“As a private soldier who knew him, I was proud to be associated with him and his theories in war. He was fearless, unorthodox, brilliant and yet human. Our feelings on hearing of his death were of personal shock and grief. He was a great soldier."

With the invaluable experience he had gained in 1943, Charles was considered an ideal candidate for the second Chindit expedition and along with many other Longcloth veterans was interviewed by Colonel Scott. However, even with the promise of a promotion in the ranks, Charles decided not to volunteer again.

“I wasn’t a regular soldier, I was a conscript. I felt I had done everything that had been asked of me in 1943. I was not ashamed of anything that had happened, my training had served me well and I felt I had done my bit.”

In 1945, Pte. Aves was transferred to the Border Regiment and went into Burma for a second time. It was during this period that he learned to his great relief that the Atom Bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki had ended the war. It is clear from listening to his Imperial War audio, that Charles was rather upset and disappointed by the way that the 13th King's performance in 1943 has been portrayed as second rate, within the pages of the many books and histories written on the subject since the war.

Pte. Charles Aves, by giving his testimony in such an honest and frank way, has provided an important insight into the feelings and emotions of the ordinary private soldier, who was thrust into war against a formidable and ferocious enemy. The emotion in his voice is very apparent when he talks through the last few minutes of his audio memoir and recounts the men with whom he served in 1943:

"I would like to dedicate these memoirs; they are not complete, but I think there is sufficient there to state my own position. I would like to dedicate them to my friends from that time.

Dick Mannion, who introduced me to many of the great tenor operatic arias and shared the monsoons with me. Freddy Raffo, a great footballer, and the first northerner to offer me friendship. Stan Allnutt, who remained a friend all through and helped me with his (Burmese) linguistic skills. David Ogden, tenor saxophonist from Irlam and Cadishead, patient, tolerant, logical and deep thinking, I always hoped some of that rubbed off on me. David Hastings, Captain, killed in the Irrawaddy crossing, my first experience in meeting an officer and a gentleman.

Smudger Smith, an honourable private, a dustman in real life. One of the eleven who stayed and didn't run. Extremely religious and helped us each day with a verse from the bible. A very kind man. Corporal Bert Fitton, left-half company football team, helped Lt.-Colonel Cooke and the sick and the wounded into the only get out plane. Found himself locked in and about to take off, pleaded with the pilot to let him out. I wonder if his family ever knew about that? I was on patrol with him once, just he and I. He was too brave for me and I had tears when I heard of his death.

There are many more now I come to think of it. But we will finish with Corporal Stan Hickman, who stopped me running away when he said don't go. I've always been pleased that I did not run away, but it really wasn't my fault. Stan Hickman was good man to be with."

Stan Hickman's death was recorded in the Spring 1974 edition of the Burma Star Association magazine, Dekho. Alongside the entry for his passing was this short obituary:

Stan, who was the Treasurer of our Nottingham Branch and formerly a Chindit with the 13th Battalion, the King's (Liverpool) Regiment was one of our mainsprings, especially during the conferences of 1966 and 1973. In all of his work for the branch and the wider Association he was meticulous and inspiring.

One BSA official will not forget how, when lost in Nottingham on the occasion of the last conference, telephoned Stan for help and directions. An immensely cheerful character supplied the desired information and it was only at the end of the conversation that the caller realised that Stan was speaking from his sick-bed! We salute him for his continued support right to last and also thank his wife, Joan.

Shown below is a final gallery of images in relation to this story including a photograph of Charles Aves with his pals from the 13th King's, Leon Frank and Bert Jacobs. This photograph was probably taken whilst the battalion were stationed at Secunderabad in early 1942. According to Charles, the man behind the camera was Pte. Dick Mannion. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Later in life, Charles Aves would write several short narratives on an array of subjects. Seen below is his viewpoint on water and what this natural element of life means to him:

Water

Water gives life, but it takes it too. It presents itself as both beautiful and benevolent and reflects these properties in the still calmness of lakes and ponds. But water is powerful and awesome when roused.

My thoughts of water always take me back many years and the war in Burma. Several hundred men without food, water and little sleep, worn out and dispirited having been behind Japanese lines for over two months. Now trapped between the broad and expansive Irrawaddy and the deceitful, fast-flowing Shweli rivers.

With the enemy closing in, the Irrawaddy had to be crossed. In the early hours of the morning we approached the village of Yantha, where we hoped to find boats. As the officers discussed terms with the Headman, who lucky for us was anti-Japanese, six boats were prepared for our crossing. My pal Stan (Hickman) was too ill with malaria to make the crossing and crawled into a nearby hut and collapsed in the dark of lonely exhaustion.

Captain David Hastings, my officer and my friend was a tower of strength. I had known him for over three years since the battalion was stationed at Felixstowe back in England. I admired him as an officer and the gentleman he was. He organised the boats and the first one set off to cross the mile-wide river.

There was a kind of unnatural silence as we made our way over the river. I was in the second or third boat and we seemed to make very slow progress over the water as the sun began to appear over the horizon. It seemed an age before the lead boat landed on the west bank and then suddenly the enemy opened up with their machine guns and mortars on our boats still out in the middle of the river. Our hearts were in our mouths as we grounded and scrambled ashore. The Burmese boatmen were jabbering in fear, but we felt safe behind the reeds on the edge of the bank which covered our bolt for the jungle. The enemy were about four hundred yards away, hidden in a small copse.

As I looked back across the river I saw our fourth boat about 600 yards or more from the bank. I swear I could see Captain Hastings in this boat and as I watched a mortar shell hit it destroying everything on board. The boat simply disappeared and I still feel sick at the thought of this incident today. Whenever I think of water, I think of that day on the Irrawaddy when this fine officer was blown to pieces alongside many more of my friends.

Water

Water gives life, but it takes it too. It presents itself as both beautiful and benevolent and reflects these properties in the still calmness of lakes and ponds. But water is powerful and awesome when roused.

My thoughts of water always take me back many years and the war in Burma. Several hundred men without food, water and little sleep, worn out and dispirited having been behind Japanese lines for over two months. Now trapped between the broad and expansive Irrawaddy and the deceitful, fast-flowing Shweli rivers.

With the enemy closing in, the Irrawaddy had to be crossed. In the early hours of the morning we approached the village of Yantha, where we hoped to find boats. As the officers discussed terms with the Headman, who lucky for us was anti-Japanese, six boats were prepared for our crossing. My pal Stan (Hickman) was too ill with malaria to make the crossing and crawled into a nearby hut and collapsed in the dark of lonely exhaustion.

Captain David Hastings, my officer and my friend was a tower of strength. I had known him for over three years since the battalion was stationed at Felixstowe back in England. I admired him as an officer and the gentleman he was. He organised the boats and the first one set off to cross the mile-wide river.

There was a kind of unnatural silence as we made our way over the river. I was in the second or third boat and we seemed to make very slow progress over the water as the sun began to appear over the horizon. It seemed an age before the lead boat landed on the west bank and then suddenly the enemy opened up with their machine guns and mortars on our boats still out in the middle of the river. Our hearts were in our mouths as we grounded and scrambled ashore. The Burmese boatmen were jabbering in fear, but we felt safe behind the reeds on the edge of the bank which covered our bolt for the jungle. The enemy were about four hundred yards away, hidden in a small copse.

As I looked back across the river I saw our fourth boat about 600 yards or more from the bank. I swear I could see Captain Hastings in this boat and as I watched a mortar shell hit it destroying everything on board. The boat simply disappeared and I still feel sick at the thought of this incident today. Whenever I think of water, I think of that day on the Irrawaddy when this fine officer was blown to pieces alongside many more of my friends.

And of the Japanese, Charles has this to say:

I can never really forgive the Japanese for what they did during the war. When I walk about London, around the Tower and other places of interest, I see the Korean and Japanese tourists, but I have no feelings for them as human beings, when I remember that some of their forefathers bayonetted my friends to death and just for the fun of it.

I can never really forgive the Japanese for what they did during the war. When I walk about London, around the Tower and other places of interest, I see the Korean and Japanese tourists, but I have no feelings for them as human beings, when I remember that some of their forefathers bayonetted my friends to death and just for the fun of it.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, December 2016.