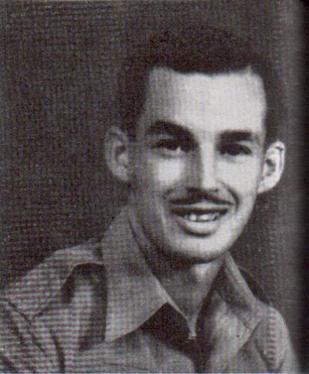

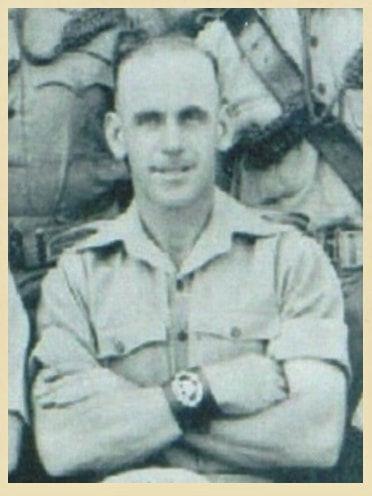

Company Quartermaster Sergeant Duncan Bett

CQMS. Duncan Bett, India 1942.

CQMS. Duncan Bett, India 1942.

3192342 Sergeant W.D.L. Bett had been in the Army for some years before he became an NCO in the 13th King's Liverpool. His Army service number suggests he was originally a soldier with the King's Own Scottish Borderers, quite a number of the NCO's from the Chindits of 1943 had come from this regiment.

Duncan had been placed into No. 6 Column during training at Saugor, but entered Burma in February 1943 with Northern Group Head Quarters under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel S.A. Cooke.

He recalled:

A lot of the original battalion fell out after the final training scheme at Jhansi and my column was unfortunately broken up to reinforce the other British columns. Our Column Commander, Major Anderson was appointed Brigade Major and I went over to No. 2 Group Headquarters together with Corporal George Bell.

Sergeant Bett was undoubtedly a fine leader of men and had always performed his duties to the highest standards, but, he was also a very compassionate and caring soldier, always concerned about the well being of the men under his command.

From my reading around the subject of the first Chindit operation, he stands out as a man who, although clearly courageous and spirited, was also very honest about his fears and anxieties. This is something he touched on when speaking about his time in Burma with Phil Chinnery, as the author prepared notes for his then forthcoming book 'March or Die'.

The following extract from the book tells of the time directly after the Dakota rescue of 17 wounded members of Column 8 on the 28th April 1943. Duncan Bett describes his feelings and fears, after realising that he and the rest of Column 8 and Northern Group HQ would now have to march back to India, as no other planes were going to return. My thanks to Phil Chinnery for permission to use this extract from his book.

We were all scared of being left behind. When we dropped down exhausted at night it was so dark under the jungle canopy that you could not see your hand at the end of your nose. It was like the tomb. I remember waking up suddenly once and I couldn't see a thing or hear a sound. No mules, no sentries, nothing. I thought I had been left behind when the column moved on before dawn. I scrabbled around in a panic, feeling for another body and the relief was indescribable when I felt someone else there on the ground. It seems hard to believe, but several men were left behind in the dark. Presumably they were so exhausted they didn't wake up and were not missed in the confusion when the column moved off.

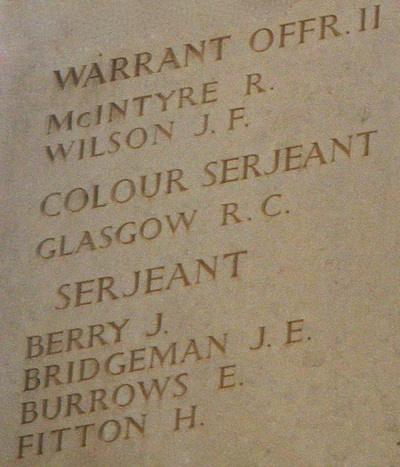

After the Dakota rescue we broke up into parties of forty or so, to make our way back to India. A day or so later we were bivouacked on the bend of a chaung when we were attacked by Japs who had crept up under the cover of a thunder-storm. As we retired to the river bank I passed another Colour Sergeant (CSM Robert Glasgow) who had been shot in the leg and was unable to walk. He asked me to shoot him as he knew the Japs would not bother to take him prisoner if he could not walk. I could not do it and had to abandon him to his fate. He was never heard of again.

On reaching the river bank, which was very high and steep, I sank over my knees in the mud with the weight of my pack, which weighed about seventy pounds. I was forced to slip it off and it rolled down the bank and disappeared in the muddy water with all my newly acquired food and gear. I was left with what I stood up in, a rifle and a bandolier of .303 ammunition.

As we neared the railway we picked up a Burmese who offered to lead us across the railway between Japanese posts. Although we were very suspicious he led us safely across at night and, just as dawn was breaking, to the entrance to a village. The Lieutenant in charge of our party placed a Sergeant and the men in some cover a short distance away while he, a warrant officer and myself leant against an earth bank outside the entrance to await the return of the Burmese guide.

Meanwhile a large covered bullock cart trundled past within touching distance, on its way to the paddy fields. After some time firing broke out where we had placed the rest of the men. The bullock cart had obviously been full of Japs and if we had tried to see what was in the cart we would not be here now. We ran into the village, which was deserted, and in the centre of an open area was a dugout with a sloping ramp and the Burmese was hiding inside. I tried to put a round up the spout of my rifle to shoot him, but it jammed. I did not have a bayonet or a grenade and as I was being fired on from the other side of the village I reluctantly had to leave him and run for cover.

I then got stuck in the tangled undergrowth, still being fired at, before breaking free and getting away from the village. From then on there were only the three of us. We had a map which was of little use, but we knew if we kept going west we would eventually reach India, which we did in about two months, picking up food in villages on the way.

We once went into a hut and obtained a chicken which had its neck wrung by the villager, who folded it over and bound it with some fine bamboo. It was deposited in a bamboo basket which I slung on my back before we went on our way in the brilliant moonlight. After a while we heard sounds of revelry in the distance and hastily dodged off the track and lay down behind a small bank in the dry paddy fields.

It was a number of villagers who had obviously been celebrating in the next village. Just as they drew level there was a tremendous fluttering from my pack. The chicken was not dead and it was making frantic efforts to escape. I got the pack off and tried to wring its neck, but instead pulled its head off and it ran around headless in circles making what seemed to us to be a tremendous noise until I managed to fall on it and quieten it. We could not believe we hadn't been noticed and they must have been very drunk on the local rice beer.

We successfully avoided any Jap patrols and crossed the Chindwin in a dugout canoe we found hidden at the river bank. After spending the night in a woodcutter's hut on the Indian side of the Chindwin we set off up a track towards Somra in the Naga Hills. After a time a voice shouted 'tairo' or halt in Urdu, as we had run into a machine-gun post manned by the Assam Rifles.

We were escorted to their headquarters several miles back and, after being fed and sleeping for about twenty-four hours, carried on towards Kohima. We were put in the Somra District Officers bungalow the following night, when suddenly shots rang out and we thought it was the Japanese, but it was the District Officer firing at rats with his revolver. We did not appreciate his efforts, but put it down to him being "round the bend" from being stuck in such a place for so many years.

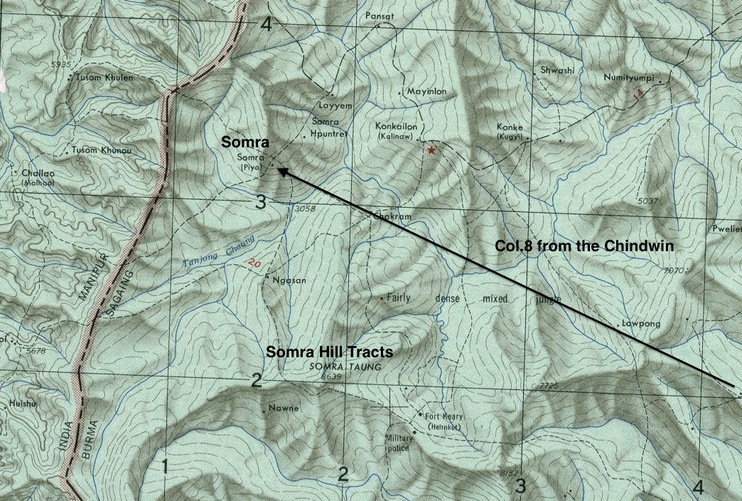

Seen below is a map of the area around Somra, where Duncan Bett and his two companions sheltered shortly after crossing the Chindwin River in late June 1943. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

Duncan had been placed into No. 6 Column during training at Saugor, but entered Burma in February 1943 with Northern Group Head Quarters under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel S.A. Cooke.

He recalled:

A lot of the original battalion fell out after the final training scheme at Jhansi and my column was unfortunately broken up to reinforce the other British columns. Our Column Commander, Major Anderson was appointed Brigade Major and I went over to No. 2 Group Headquarters together with Corporal George Bell.

Sergeant Bett was undoubtedly a fine leader of men and had always performed his duties to the highest standards, but, he was also a very compassionate and caring soldier, always concerned about the well being of the men under his command.

From my reading around the subject of the first Chindit operation, he stands out as a man who, although clearly courageous and spirited, was also very honest about his fears and anxieties. This is something he touched on when speaking about his time in Burma with Phil Chinnery, as the author prepared notes for his then forthcoming book 'March or Die'.

The following extract from the book tells of the time directly after the Dakota rescue of 17 wounded members of Column 8 on the 28th April 1943. Duncan Bett describes his feelings and fears, after realising that he and the rest of Column 8 and Northern Group HQ would now have to march back to India, as no other planes were going to return. My thanks to Phil Chinnery for permission to use this extract from his book.

We were all scared of being left behind. When we dropped down exhausted at night it was so dark under the jungle canopy that you could not see your hand at the end of your nose. It was like the tomb. I remember waking up suddenly once and I couldn't see a thing or hear a sound. No mules, no sentries, nothing. I thought I had been left behind when the column moved on before dawn. I scrabbled around in a panic, feeling for another body and the relief was indescribable when I felt someone else there on the ground. It seems hard to believe, but several men were left behind in the dark. Presumably they were so exhausted they didn't wake up and were not missed in the confusion when the column moved off.

After the Dakota rescue we broke up into parties of forty or so, to make our way back to India. A day or so later we were bivouacked on the bend of a chaung when we were attacked by Japs who had crept up under the cover of a thunder-storm. As we retired to the river bank I passed another Colour Sergeant (CSM Robert Glasgow) who had been shot in the leg and was unable to walk. He asked me to shoot him as he knew the Japs would not bother to take him prisoner if he could not walk. I could not do it and had to abandon him to his fate. He was never heard of again.

On reaching the river bank, which was very high and steep, I sank over my knees in the mud with the weight of my pack, which weighed about seventy pounds. I was forced to slip it off and it rolled down the bank and disappeared in the muddy water with all my newly acquired food and gear. I was left with what I stood up in, a rifle and a bandolier of .303 ammunition.

As we neared the railway we picked up a Burmese who offered to lead us across the railway between Japanese posts. Although we were very suspicious he led us safely across at night and, just as dawn was breaking, to the entrance to a village. The Lieutenant in charge of our party placed a Sergeant and the men in some cover a short distance away while he, a warrant officer and myself leant against an earth bank outside the entrance to await the return of the Burmese guide.

Meanwhile a large covered bullock cart trundled past within touching distance, on its way to the paddy fields. After some time firing broke out where we had placed the rest of the men. The bullock cart had obviously been full of Japs and if we had tried to see what was in the cart we would not be here now. We ran into the village, which was deserted, and in the centre of an open area was a dugout with a sloping ramp and the Burmese was hiding inside. I tried to put a round up the spout of my rifle to shoot him, but it jammed. I did not have a bayonet or a grenade and as I was being fired on from the other side of the village I reluctantly had to leave him and run for cover.

I then got stuck in the tangled undergrowth, still being fired at, before breaking free and getting away from the village. From then on there were only the three of us. We had a map which was of little use, but we knew if we kept going west we would eventually reach India, which we did in about two months, picking up food in villages on the way.

We once went into a hut and obtained a chicken which had its neck wrung by the villager, who folded it over and bound it with some fine bamboo. It was deposited in a bamboo basket which I slung on my back before we went on our way in the brilliant moonlight. After a while we heard sounds of revelry in the distance and hastily dodged off the track and lay down behind a small bank in the dry paddy fields.

It was a number of villagers who had obviously been celebrating in the next village. Just as they drew level there was a tremendous fluttering from my pack. The chicken was not dead and it was making frantic efforts to escape. I got the pack off and tried to wring its neck, but instead pulled its head off and it ran around headless in circles making what seemed to us to be a tremendous noise until I managed to fall on it and quieten it. We could not believe we hadn't been noticed and they must have been very drunk on the local rice beer.

We successfully avoided any Jap patrols and crossed the Chindwin in a dugout canoe we found hidden at the river bank. After spending the night in a woodcutter's hut on the Indian side of the Chindwin we set off up a track towards Somra in the Naga Hills. After a time a voice shouted 'tairo' or halt in Urdu, as we had run into a machine-gun post manned by the Assam Rifles.

We were escorted to their headquarters several miles back and, after being fed and sleeping for about twenty-four hours, carried on towards Kohima. We were put in the Somra District Officers bungalow the following night, when suddenly shots rang out and we thought it was the Japanese, but it was the District Officer firing at rats with his revolver. We did not appreciate his efforts, but put it down to him being "round the bend" from being stuck in such a place for so many years.

Seen below is a map of the area around Somra, where Duncan Bett and his two companions sheltered shortly after crossing the Chindwin River in late June 1943. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

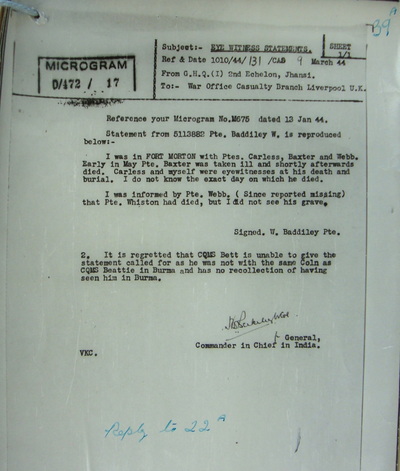

I mentioned earlier that Sergeant Bett had always tried to help out his Chindit comrades. After the operation was declared closed in July 1943, he was one of the many men who offered to assist in the compilation of the battalion's missing in action files. Sadly, only one of his statements (seen below) has survived and this referred to a group from Chindit Column 5 in 1943, about which Duncan knew nothing. There is no doubt that he would have given up all he knew about the fate of the lost men from 1943, men such as CSM Robert Glasgow for instance, who he mentions being wounded at the Kaukkwe Chaung.

On the 19th October 1943, whilst the battalion were settling in to their new home at the Napier Barracks in Karachi, the news came through that Duncan Bett was to be awarded the Royal Humane Society Testimonial for his attempted rescue in July 1942 of CSM George Bateman. After a flash flood at the Chindit training camp in Patharia, George Bateman and two other soldiers had been swept away by the then raging Sunwar River. Duncan, at great risk to his own life had tried in vain to save the life of his fellow NCO, but the current had been too strong and Bateman was washed away and sadly drowned.

For more information about this incident please click on the following link and scroll down to the relevant story: Men Who Died in Training

Seen below are some more images in relation to Company Quartermaster Sergeant Duncan Bett and his time with the 13th King's in 1942-43. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

On the 19th October 1943, whilst the battalion were settling in to their new home at the Napier Barracks in Karachi, the news came through that Duncan Bett was to be awarded the Royal Humane Society Testimonial for his attempted rescue in July 1942 of CSM George Bateman. After a flash flood at the Chindit training camp in Patharia, George Bateman and two other soldiers had been swept away by the then raging Sunwar River. Duncan, at great risk to his own life had tried in vain to save the life of his fellow NCO, but the current had been too strong and Bateman was washed away and sadly drowned.

For more information about this incident please click on the following link and scroll down to the relevant story: Men Who Died in Training

Seen below are some more images in relation to Company Quartermaster Sergeant Duncan Bett and his time with the 13th King's in 1942-43. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 29/07/2015.

I was extremely saddened to learn of Duncan's death via the obituaries section of the Burma Star Association magazine, Dekho. In the Summer 2015 edition, issue number 180, the simple one line entry reads: WDL Bett; 13th Bn. The King's (Liverpool) Regt; HQ.

I have added an image of the obituary into the gallery above.

Update 22/04/2017.

From the pages of the Hawick News dated Friday 16th July 1943 and under the headline, Hawick soldier in Wingate Expedition:

CQMS Bett, son of Mr. and Mrs. J.S. Bett of Rossarden in Weensland Road, who took part in the recent Wingate expedition against the Japanese, has some interesting comments to make in an airgraph received this week. CQMS Bett says: I have just returned from Burma with the Chindits, and am now safe and well in India. At present I am having ten days rest in hospital and being fed like a Lord on chicken and fruit etc. and a tin of milk and a bottle of beer every day. It is quite a change from rice, which was my only food for over a month on the way out, and I am now feeling very fit and will be going on five weeks leave very soon.

I did a few miles marching over there, and was well over the other side of the Irrawaddy before turning back. I re-crossed the Chindwin with two other men, and was very glad to see it! We had quite a few encounters with the Japs, and I was ambushed seven times in all by them, but got out O.K. each time, and am still in none piece. We gave them a real shaking-up, and they sent plenty of extra troops after us. On one occasion we were foraging for food in a village at night, and, unknown to us, they were doing the same thing at the other end of the village. We had to beat it quick and try elsewhere.

Last September (1942), this Hawick soldier was mentioned in orders by the G.O.C. India, for showing great gallantry and disregard for his own personal safety. The official description of the incident said: CQMS Bett plunged into a current to go to the rescue of another soldier who was in difficulties. He supported him for a distance of 350 yards over rocks and cataracts, when he was forced to relinquish his hold and only narrowly escaped with his own life.

Seen below is another gallery of images in relation to this story, including photographs of George Bell and Major Menzies-Anderson. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

I was extremely saddened to learn of Duncan's death via the obituaries section of the Burma Star Association magazine, Dekho. In the Summer 2015 edition, issue number 180, the simple one line entry reads: WDL Bett; 13th Bn. The King's (Liverpool) Regt; HQ.

I have added an image of the obituary into the gallery above.

Update 22/04/2017.

From the pages of the Hawick News dated Friday 16th July 1943 and under the headline, Hawick soldier in Wingate Expedition:

CQMS Bett, son of Mr. and Mrs. J.S. Bett of Rossarden in Weensland Road, who took part in the recent Wingate expedition against the Japanese, has some interesting comments to make in an airgraph received this week. CQMS Bett says: I have just returned from Burma with the Chindits, and am now safe and well in India. At present I am having ten days rest in hospital and being fed like a Lord on chicken and fruit etc. and a tin of milk and a bottle of beer every day. It is quite a change from rice, which was my only food for over a month on the way out, and I am now feeling very fit and will be going on five weeks leave very soon.

I did a few miles marching over there, and was well over the other side of the Irrawaddy before turning back. I re-crossed the Chindwin with two other men, and was very glad to see it! We had quite a few encounters with the Japs, and I was ambushed seven times in all by them, but got out O.K. each time, and am still in none piece. We gave them a real shaking-up, and they sent plenty of extra troops after us. On one occasion we were foraging for food in a village at night, and, unknown to us, they were doing the same thing at the other end of the village. We had to beat it quick and try elsewhere.

Last September (1942), this Hawick soldier was mentioned in orders by the G.O.C. India, for showing great gallantry and disregard for his own personal safety. The official description of the incident said: CQMS Bett plunged into a current to go to the rescue of another soldier who was in difficulties. He supported him for a distance of 350 yards over rocks and cataracts, when he was forced to relinquish his hold and only narrowly escaped with his own life.

Seen below is another gallery of images in relation to this story, including photographs of George Bell and Major Menzies-Anderson. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 30/10/2020.

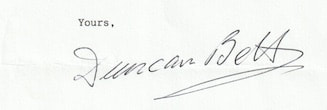

In preparation for his book, March or Die, author Phil Chinnery was in communication with Duncan Bett during the latter months of 1995. Amongst his recollections Duncan told him:

With reference to your letter of 29th October 1995 and our subsequent telephone conversation I do not know if any of my experiences will be of use to you as I seemed to spend most of my time in Burma just marching around. We were desperate for water on one occasion and had to resort to digging in the dried up bed of a stream at a bend where we thought there might be some water. All we got was more or less liquid mud which we strained through a piece of cloth. It was horrible but it was moist so we swallowed it. We did not receive many supply drops during the expedition and were delighted to receive fresh rations but less so when fodder for the mules was shoved out of the Dakota without warning, or a parachute. They landed on the dried up paddy fields with a tremendous thud and would have flattened anyone unfortunate to be beneath them. Miraculously no one was killed.

On the march in we had bullocks and chargers carrying ammunition and the idea was that when the ammunition was expended we would have fresh meat by eating the bullocks. On the only occasion I remember receiving any meat, we received a message that Japanese planes were about and we were forbidden to light cooking fires as the smoke hanging above the jungle canopy would have given our position away. I was left with a large chunk of bloody flesh and had the option of throwing it away or eating it raw. As I was starving I ate it raw and to this day cannot stand my beef or steak done rare.

As for the chargers which were supposed to carry any sick or wounded who could stay in the saddle. I saw one poor beast so exhausted that it could not put its foot down and stuck with it suspended in mid air before it eventually managed to move a few more steps. In the end it had to be shot and I think the liver was removed and eaten. A private soldier with severe dysentery was put on one charger but eventually fell off dead. His body was rolled to the side of the track and covered with teak leaves and the column moved on. It really was a case of march or die.

I contracted malaria late in expedition and rode a mule bareback for several days. I kept falling off and my comrades shoved me back on again on a number of occasions before I was able to stagger along on my own two feet. I count myself very lucky to be here today. After I got out of Burma I was in Karachi British Military Hospital seventeen times in a year with malaria and was eventually medically downgraded. On one occasion after I had walked from our barracks to the hospital because no transport was available I had a temperature of 106.4!

As I mentioned before, Corporal George Bell was with me in Burma. I remember on one occasion after we had began our return journey to India, marching up a chaung and saying to George that I thought we had passed this way before. We were supposed to be marching westward by compass bearing but had only achieved a very large circle over 24 hours. We were devastated when we realised.

In answer to your question about meeting up with my old Chindit comrades. I have never been to a reunion having spent most of my working life in the far east, but intend to fit it in this year (1996) between a salmon fishing expedition to Ireland and another week fishing on the Aberdeenshire Dee. At 23, George Bell and I were a bit younger than most of the men in the King's, whose average age was around 30. Despite everything I have been through I am reasonably fit and run five miles three times a week even at the age of 76. I am not up to it now, but ten years ago I finished the London marathon in 3 hours 46 minutes and was ninth in my age group, so I could not have sustained too much damage as a result of my exploits in Burma.

In preparation for his book, March or Die, author Phil Chinnery was in communication with Duncan Bett during the latter months of 1995. Amongst his recollections Duncan told him:

With reference to your letter of 29th October 1995 and our subsequent telephone conversation I do not know if any of my experiences will be of use to you as I seemed to spend most of my time in Burma just marching around. We were desperate for water on one occasion and had to resort to digging in the dried up bed of a stream at a bend where we thought there might be some water. All we got was more or less liquid mud which we strained through a piece of cloth. It was horrible but it was moist so we swallowed it. We did not receive many supply drops during the expedition and were delighted to receive fresh rations but less so when fodder for the mules was shoved out of the Dakota without warning, or a parachute. They landed on the dried up paddy fields with a tremendous thud and would have flattened anyone unfortunate to be beneath them. Miraculously no one was killed.

On the march in we had bullocks and chargers carrying ammunition and the idea was that when the ammunition was expended we would have fresh meat by eating the bullocks. On the only occasion I remember receiving any meat, we received a message that Japanese planes were about and we were forbidden to light cooking fires as the smoke hanging above the jungle canopy would have given our position away. I was left with a large chunk of bloody flesh and had the option of throwing it away or eating it raw. As I was starving I ate it raw and to this day cannot stand my beef or steak done rare.

As for the chargers which were supposed to carry any sick or wounded who could stay in the saddle. I saw one poor beast so exhausted that it could not put its foot down and stuck with it suspended in mid air before it eventually managed to move a few more steps. In the end it had to be shot and I think the liver was removed and eaten. A private soldier with severe dysentery was put on one charger but eventually fell off dead. His body was rolled to the side of the track and covered with teak leaves and the column moved on. It really was a case of march or die.

I contracted malaria late in expedition and rode a mule bareback for several days. I kept falling off and my comrades shoved me back on again on a number of occasions before I was able to stagger along on my own two feet. I count myself very lucky to be here today. After I got out of Burma I was in Karachi British Military Hospital seventeen times in a year with malaria and was eventually medically downgraded. On one occasion after I had walked from our barracks to the hospital because no transport was available I had a temperature of 106.4!

As I mentioned before, Corporal George Bell was with me in Burma. I remember on one occasion after we had began our return journey to India, marching up a chaung and saying to George that I thought we had passed this way before. We were supposed to be marching westward by compass bearing but had only achieved a very large circle over 24 hours. We were devastated when we realised.

In answer to your question about meeting up with my old Chindit comrades. I have never been to a reunion having spent most of my working life in the far east, but intend to fit it in this year (1996) between a salmon fishing expedition to Ireland and another week fishing on the Aberdeenshire Dee. At 23, George Bell and I were a bit younger than most of the men in the King's, whose average age was around 30. Despite everything I have been through I am reasonably fit and run five miles three times a week even at the age of 76. I am not up to it now, but ten years ago I finished the London marathon in 3 hours 46 minutes and was ninth in my age group, so I could not have sustained too much damage as a result of my exploits in Burma.

In June 1996, Duncan was finally able to attend the Chindit Old Comrades reunion dinner held in Walsall. He later recalled:

I was delighted to attend the reunion at Walsall which my wife and I thoroughly enjoyed, although I was slightly disappointed not to meet any of my old comrades and appeared to be the only one present from the 1943 expedition. However, I was very pleased to be introduced to Mrs. Georgina Livingstone, widow of CSM (later RSM) William Livingstone, who was one of the two other men with whom I marched out of Burma in April 1943. Unfortunately, he had passed away about fifteen years ago, but Mrs. Livingstone said she was pleased she would be able to tell her son that she had met someone who had been in Burma with his father.

I was delighted to attend the reunion at Walsall which my wife and I thoroughly enjoyed, although I was slightly disappointed not to meet any of my old comrades and appeared to be the only one present from the 1943 expedition. However, I was very pleased to be introduced to Mrs. Georgina Livingstone, widow of CSM (later RSM) William Livingstone, who was one of the two other men with whom I marched out of Burma in April 1943. Unfortunately, he had passed away about fifteen years ago, but Mrs. Livingstone said she was pleased she would be able to tell her son that she had met someone who had been in Burma with his father.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, October 2014.