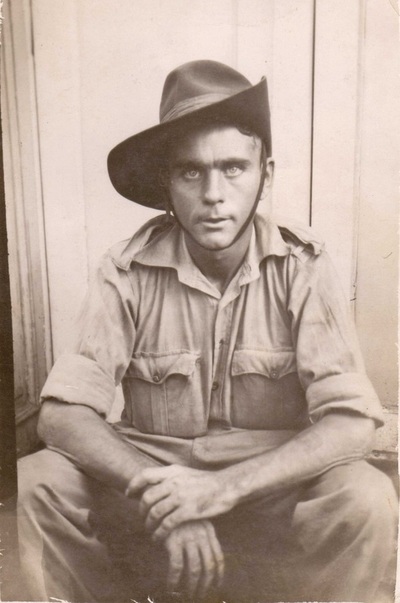

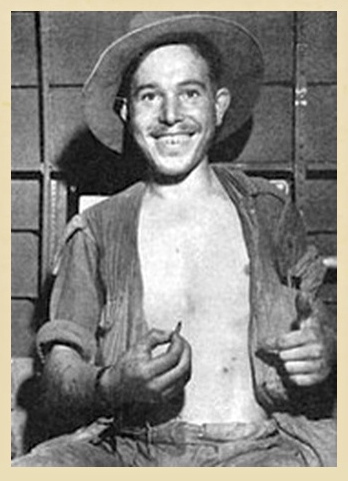

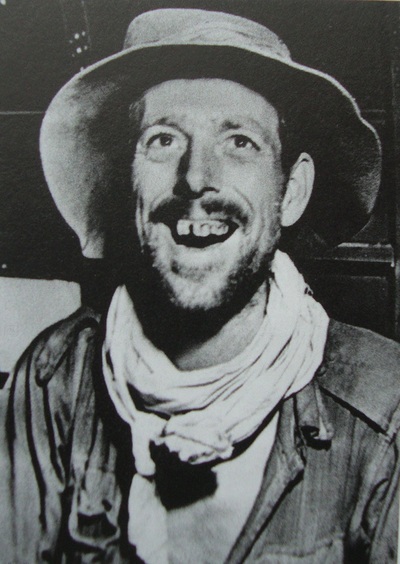

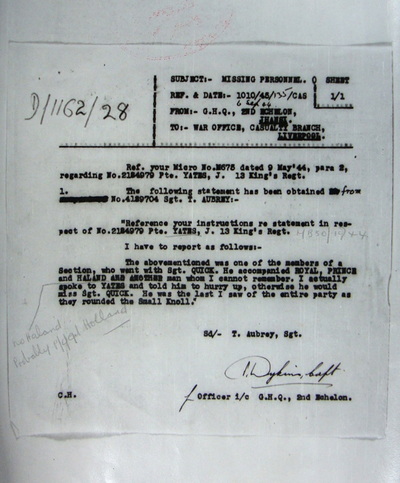

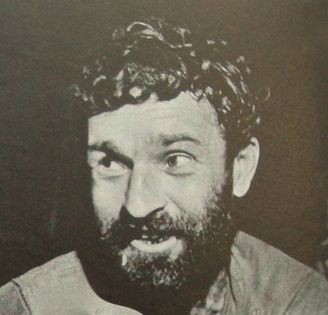

Lance Sergeant Tony Aubrey

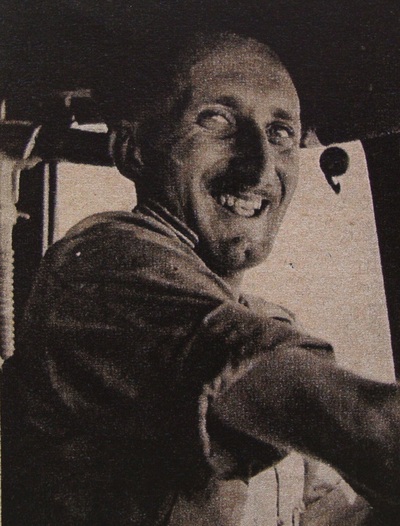

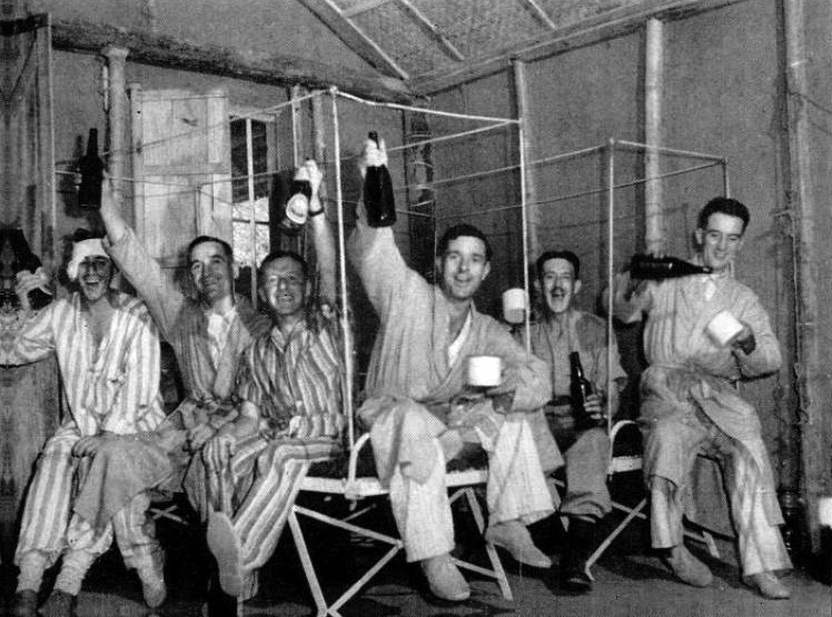

Tony Aubrey aboard the escape Dakota, 28th April 1943.

Tony Aubrey aboard the escape Dakota, 28th April 1943.

Tony Aubrey is undoubtedly one of the brightest and most well-loved characters to come out of the writings for Operation Longcloth. He features in several of the war diaries for the 13th King's and had his own experiences on the first Chindit expedition immortalised for posterity in the book 'With Wingate in Burma' written by David Halley.

In his formative years, young Tony's destiny was pre-planned by his father, who was a well respected doctor, and like so many in the profession for the serving of their fellow man, hoped for his son to follow willingly in his footsteps. However, like so many such sons, Tony was not of the same mind.

"My father and I had words", Tony recalled. After which he left home and went to stay with his paternal Aunt in York. After a while, and again with pressure from his father, Tony's Aunt told him he could no longer stay with her and her husband. Still determined not to fall in with his father's wishes, Tony travelled to the city of Liverpool and began waitering aboard the various ships working out of that great port. His first job in this regard saw him sailing back and forth from Liverpool to Llandudno and sometimes across the Menai Straits to Anglesey. Not the stuff of dreams or sizeable adventure, but he soon fell on his feet.

After a short period at the bottom of the pile, Tony made it to the status of Head Waiter, which included working in some of Europe's top hotels. He worked all over, in Magdeburg, Germany, in Barcelona during the period of the Fascist War and then in Hong Kong and Shanghai. It was whilst working in China that Tony first came across the expansionist nature of the Japanese, illustrated perfectly by their illegal occupation of Manchuria in the early 1930's. As the war clouds gathered over Europe, he decided to return home and enlist into the Armed Forces. He left his job in Shanghai and sailed home to England, by September 1939 Tony had been posted to the Royal Welch Fusiliers and was given the Army service number 4189704.

Tony remembered: "I saw service in the BEF in France and put in nine long months winning the war in Iceland." By June 1942 he was stationed in Dorset and it was from here that he learned of his impending posting overseas. Three months later he was at the British Base Reinforcement Camp at Deolali in India, from where he was transferred, by now as a Sergeant to the King's Liverpool Regiment. Tony arrived at the King's training camp at Saugor in late September 1942 and he was placed into Chindit Column 6, commanded by Major Gilmour Menzies Anderson. He soon acclimatised to the training regime at Saugor and performed so well that he was chosen for a pre-operational reconnaissance mission which was to take place just after the Christmas holidays.

Also chosen to join this reconnaissance party which was to be led by Captain Denis Clive Herring, known unsurprisingly as 'Fish' to his comrades, were, Lance Corporal Tommy Vann, a stoically reliable soldier with witty sense of humour, and Pte. Stanley Allnutt, chosen one would imagine for his knowledge of the Burmese language, an unusual attribute for a British soldier at that time.

The group moved quickly across from the training centre at Saugor to the town of Imphal, they were then transported by an old three-ton Bedford truck along the tortuous and twisting hillside roads to Tamu, which lies close to the official land border with Burma. I will let Tony Aubrey take up the story at this point:

Our numbers were now much smaller than the original party, as Lieutenant Bruce had left us to strike out on his own at Imphal, taking with him all the Burmese, except for six. But we had been reinforced by the addition of two mules and their Punjabi Mussulmen muleteers. Our first halt was at Tamu, seventeen miles farther up the track.

This had been, in the days of peace, an elephant station belonging to the company of which Captain Herring had been an employee. He was the ideal man for the sort of job we had in hand, for he had been in Burma for a good many years, spoke the language like a native, and knew intimately the country through which we would travel. Also, he had been a Territorial Officer in the Burma Rifles, and had fought against the Japanese in the retreat. He didn't like them at all, but he did love the Burmese.

He was as pleased as a child with a new toy at having been given this chance of getting a bit of his own back. I don't actually know, of course, what orders he had been given about this reconnaissance, but I imagine they had simply said to him, "Get across the Chindwin River and find out all you can. Oh, and by the way, be back by the first of January, will you?"

That date was the limit set on the duration of our trip. An old friend of Captain Herring's named Mr.Thomas, was in charge of the elephant station at Tamu. The Japs had paid him a visit but had done him no physical harm, as they used him as an intermediary between themselves and the Burmese. But he had had in his charge fifty of the Company's elephants, and the Japanese tried to take away every one of these.

However, the few mahouts (elephant drivers) and their wives who had disdained to run away on the approach of the enemy, followed them when they had gone, and succeeded in regaining possession of seventeen of their animals. These seventeen were still in the station, and when we went ahead the next day we took one of them, and his mahout, Nandaw, with us in place of the two mules, which were returned with their drivers to Imphal.

So when we left on the final stage of our march to the Chindwin our party was ten strong, Captain Herring, myself, Vann and Allnutt, and the six men of the Burmese Rifles, and with us went Nandaw and his elephant. The path was now very narrow, and passed through jungle denser than any I had ever seen before. Visibility was sometimes practically nil, and I was lost in amazement at the silent progress of the elephant, which manoeuvred its colossal bulk through the scrub with less fuss and commotion than that made by any of us.

I marvelled, too, at the speed and skill Nandaw showed in clearing overhanging branches out of his way with one sweep of his dha, and without ever checking the elephant's progress. Every now and again, along the edges of this ill-omened path, we came on traces of the retreat from Burma. Now, it would be a single corpse, or two or three together in a melancholy huddle. Now, it would be an old-fashioned motor bus, lonely and incongruous in its tropical surroundings; now, a motor car or a lorry, overturned and defeated by the narrowness of the way, some heaps of bones around it showing that its occupants had also given up the unequal struggle.

The distance from Tamu to the Chindwin River is forty-seven miles as the crow flies, but we took three days to cover it. While Nandaw and his elephant kept straight ahead down the path without escort, as we had had reliable information that there were none of the enemy this side of the river, the remainder of us made continual casts in parties to north and south of us, gathering information about water for animals, and places suitable for the resting and concealment of bodies of troops.

Sometimes when making these casts we came across old hutments, and then, in spite of our information, we approached them with every precaution, for the Jap is a crafty animal, and we were always on the lookout for booby traps and other pieces of devilment. We arrived at a spot three miles from the river on the evening of the third day, and here Captain Herring decided we should camp, for straight ahead of us on the river itself lay a large village, and he did not feel inclined to let our presence be known there until he had found out how the land lay.

The group led by Captain Herring moved across the Chindwin without incident and spent several days penetrating through the jungles on the eastern side of the river. They pushed on for several miles taking their time to check on the morale and demeanour of the Burmese in the vicinity and evaluating whether these villagers might be prepared to assist Wingate's new force over the forthcoming weeks. After gathering this intelligence the party returned to Chindit HQ to report their findings. While they had been away, 6 Column had been disbanded, this was due to the amount of illness and misfortune the unit had suffered at Saugor, leaving barely 50 men still fit enough to continue their time with 77th Brigade.

Tony Aubrey and Tommy Vann were transferred over to 8 Column, commanded by Major Walter Scott, whilst Stan Allnutt was sent to 7 Column led by Major Gilkes. Seen below is a map of the area around the Burmese town of Tonmakeng, one of the settlements visited by Captain Herring's recce party in January 1943. Tonmakeng was eventually chosen to be the location for Northern Group's first supply drop during Operation Longcloth which took place on the 26th February.

In his formative years, young Tony's destiny was pre-planned by his father, who was a well respected doctor, and like so many in the profession for the serving of their fellow man, hoped for his son to follow willingly in his footsteps. However, like so many such sons, Tony was not of the same mind.

"My father and I had words", Tony recalled. After which he left home and went to stay with his paternal Aunt in York. After a while, and again with pressure from his father, Tony's Aunt told him he could no longer stay with her and her husband. Still determined not to fall in with his father's wishes, Tony travelled to the city of Liverpool and began waitering aboard the various ships working out of that great port. His first job in this regard saw him sailing back and forth from Liverpool to Llandudno and sometimes across the Menai Straits to Anglesey. Not the stuff of dreams or sizeable adventure, but he soon fell on his feet.

After a short period at the bottom of the pile, Tony made it to the status of Head Waiter, which included working in some of Europe's top hotels. He worked all over, in Magdeburg, Germany, in Barcelona during the period of the Fascist War and then in Hong Kong and Shanghai. It was whilst working in China that Tony first came across the expansionist nature of the Japanese, illustrated perfectly by their illegal occupation of Manchuria in the early 1930's. As the war clouds gathered over Europe, he decided to return home and enlist into the Armed Forces. He left his job in Shanghai and sailed home to England, by September 1939 Tony had been posted to the Royal Welch Fusiliers and was given the Army service number 4189704.

Tony remembered: "I saw service in the BEF in France and put in nine long months winning the war in Iceland." By June 1942 he was stationed in Dorset and it was from here that he learned of his impending posting overseas. Three months later he was at the British Base Reinforcement Camp at Deolali in India, from where he was transferred, by now as a Sergeant to the King's Liverpool Regiment. Tony arrived at the King's training camp at Saugor in late September 1942 and he was placed into Chindit Column 6, commanded by Major Gilmour Menzies Anderson. He soon acclimatised to the training regime at Saugor and performed so well that he was chosen for a pre-operational reconnaissance mission which was to take place just after the Christmas holidays.

Also chosen to join this reconnaissance party which was to be led by Captain Denis Clive Herring, known unsurprisingly as 'Fish' to his comrades, were, Lance Corporal Tommy Vann, a stoically reliable soldier with witty sense of humour, and Pte. Stanley Allnutt, chosen one would imagine for his knowledge of the Burmese language, an unusual attribute for a British soldier at that time.

The group moved quickly across from the training centre at Saugor to the town of Imphal, they were then transported by an old three-ton Bedford truck along the tortuous and twisting hillside roads to Tamu, which lies close to the official land border with Burma. I will let Tony Aubrey take up the story at this point:

Our numbers were now much smaller than the original party, as Lieutenant Bruce had left us to strike out on his own at Imphal, taking with him all the Burmese, except for six. But we had been reinforced by the addition of two mules and their Punjabi Mussulmen muleteers. Our first halt was at Tamu, seventeen miles farther up the track.

This had been, in the days of peace, an elephant station belonging to the company of which Captain Herring had been an employee. He was the ideal man for the sort of job we had in hand, for he had been in Burma for a good many years, spoke the language like a native, and knew intimately the country through which we would travel. Also, he had been a Territorial Officer in the Burma Rifles, and had fought against the Japanese in the retreat. He didn't like them at all, but he did love the Burmese.

He was as pleased as a child with a new toy at having been given this chance of getting a bit of his own back. I don't actually know, of course, what orders he had been given about this reconnaissance, but I imagine they had simply said to him, "Get across the Chindwin River and find out all you can. Oh, and by the way, be back by the first of January, will you?"

That date was the limit set on the duration of our trip. An old friend of Captain Herring's named Mr.Thomas, was in charge of the elephant station at Tamu. The Japs had paid him a visit but had done him no physical harm, as they used him as an intermediary between themselves and the Burmese. But he had had in his charge fifty of the Company's elephants, and the Japanese tried to take away every one of these.

However, the few mahouts (elephant drivers) and their wives who had disdained to run away on the approach of the enemy, followed them when they had gone, and succeeded in regaining possession of seventeen of their animals. These seventeen were still in the station, and when we went ahead the next day we took one of them, and his mahout, Nandaw, with us in place of the two mules, which were returned with their drivers to Imphal.

So when we left on the final stage of our march to the Chindwin our party was ten strong, Captain Herring, myself, Vann and Allnutt, and the six men of the Burmese Rifles, and with us went Nandaw and his elephant. The path was now very narrow, and passed through jungle denser than any I had ever seen before. Visibility was sometimes practically nil, and I was lost in amazement at the silent progress of the elephant, which manoeuvred its colossal bulk through the scrub with less fuss and commotion than that made by any of us.

I marvelled, too, at the speed and skill Nandaw showed in clearing overhanging branches out of his way with one sweep of his dha, and without ever checking the elephant's progress. Every now and again, along the edges of this ill-omened path, we came on traces of the retreat from Burma. Now, it would be a single corpse, or two or three together in a melancholy huddle. Now, it would be an old-fashioned motor bus, lonely and incongruous in its tropical surroundings; now, a motor car or a lorry, overturned and defeated by the narrowness of the way, some heaps of bones around it showing that its occupants had also given up the unequal struggle.

The distance from Tamu to the Chindwin River is forty-seven miles as the crow flies, but we took three days to cover it. While Nandaw and his elephant kept straight ahead down the path without escort, as we had had reliable information that there were none of the enemy this side of the river, the remainder of us made continual casts in parties to north and south of us, gathering information about water for animals, and places suitable for the resting and concealment of bodies of troops.

Sometimes when making these casts we came across old hutments, and then, in spite of our information, we approached them with every precaution, for the Jap is a crafty animal, and we were always on the lookout for booby traps and other pieces of devilment. We arrived at a spot three miles from the river on the evening of the third day, and here Captain Herring decided we should camp, for straight ahead of us on the river itself lay a large village, and he did not feel inclined to let our presence be known there until he had found out how the land lay.

The group led by Captain Herring moved across the Chindwin without incident and spent several days penetrating through the jungles on the eastern side of the river. They pushed on for several miles taking their time to check on the morale and demeanour of the Burmese in the vicinity and evaluating whether these villagers might be prepared to assist Wingate's new force over the forthcoming weeks. After gathering this intelligence the party returned to Chindit HQ to report their findings. While they had been away, 6 Column had been disbanded, this was due to the amount of illness and misfortune the unit had suffered at Saugor, leaving barely 50 men still fit enough to continue their time with 77th Brigade.

Tony Aubrey and Tommy Vann were transferred over to 8 Column, commanded by Major Walter Scott, whilst Stan Allnutt was sent to 7 Column led by Major Gilkes. Seen below is a map of the area around the Burmese town of Tonmakeng, one of the settlements visited by Captain Herring's recce party in January 1943. Tonmakeng was eventually chosen to be the location for Northern Group's first supply drop during Operation Longcloth which took place on the 26th February.

During Operation Longcloth, Sgt. Aubrey served with Platoon 17 commanded by Captain Joseph Coughlan longstanding of the King's Regiment. As mentioned earlier 8 Column were commanded by Major Walter Purcell Scott, also an original officer with the 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment. Scott was an incredibly popular leader and was adored by all his men.

Here is how Sergeant Tony Aubrey remembers his commander: "There is only one word to use about Major Scott, he was a smasher. He had personality, courage, foresight, and the greatest of all qualities in a leader, luck. He had been a Lance Corporal during the battle of France and so he knew the mens point of view. He had as much time for the thoughts and ideas of the humble private, as he had for his second in command. He respected his men and they would follow him anywhere."

Platoon 17 was made up of many fine characters, mostly from the north of England, but with a couple of Londoners thrown in for good measure. Here is how Tony remembered those first few weeks inside Burma and the men he came to rely on:

"The platoon slowly began to get to know each other. On the long night time halts in bivouac there was nothing else to do other than talk about our families, previous experiences and our hopes and fears about what might lie ahead in the coming days.

Our platoon Sergeant was Tom Quick, a genial type of chap from Manchester. He was the last sort of fellow you would ever had thought likely to get himself mixed up in a war. Poor Tommy only ever wanted to get back home to his family whom he clearly loved dearly. Then there was Corporal Walsh, who was also from Manchester. He was a ginger headed lad, but his nature belied the colour of his hair, as a cooler customer you could never wish to meet.

Norman Lambert was from Middlesborough and always seemed to be with his great buddy Arthur Birch. Lambert was a great hand on the piano and Birch was a comical little fellow always ready with a gag. They would have made a great double act in the music halls back home, as they did on the Bren gun in Burma. Another comic in Platoon 17 was Jim Suddery from Islington, London. He was always ready with a crack and his quick-fire Cockney wit contrasted hilariously with the more placid humour of Birch. Jim was number one on another Bren and nothing ever separated him from his beloved gun, it was flesh of his flesh. All in all we were a happy family and got along very well."

On the 16th February 1943, 8 Column reached the village of Tonhe on the western banks of the Chindwin River and crossed over into enemy held territory. After crossing the Chindwin, 8 Column travelled around Burma during the early weeks of the operation in close proximity to Wingate's own Brigade Head Quarters, often protecting their leader against possible enemy attacks. Their first skirmish with the enemy was at Pinlebu, where the Japanese supposedly had a large garrison. The town was attacked by the Chindits, but no enemy were to be found, although some clashes did take place on the main track east of the town with some resulting casualties amongst Scott's men.

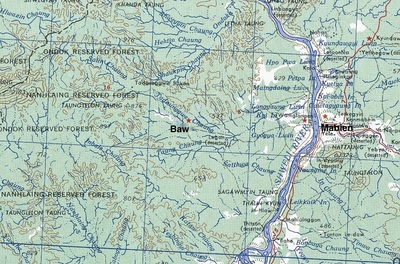

While Fergusson and Calvert's columns set about their destructive work upon the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway, 8 Column moved around the locality creating diversions and generally taking up the attention of the Japanese. After several weeks inside Burma and having recently crossed over the Irrawaddy River, Wingate and his Brigade had planned to receive an extremely large supply drop close to the Burmese village of Baw. Unfortunately, it was whilst preparing for this supply drop that things went horribly wrong for Sgt. Aubrey's platoon.

The supply drop at Baw was planned for the 23/24 of March and was to be an extremely large affair, re-supplying around 1300 men from Northern Section. Wingate and his column commanders surveyed maps of the area and chose the drop zone (a succession of dry paddy fields on the outskirts of the village), orders were given for two units to secure the main road leading in and out of the village, one of the road blocks was to be manned by Platoon 17.

The platoon set off to secure the tracks to the east of the village and were supposed to be in place before first light the following morning. The men encountered some dense bamboo jungle during their journey to the agreed location and in the end Captain Coughlan called a halt to proceedings and told the men to bed down for a few hours until there was enough light to complete the march in comfort. This was to prove his unit's undoing and would cost the Captain his rank and his place in Column 8.

At first light the platoon pushed on, but immediately ran into Japanese sentries, a Burma Rifleman shot one of the enemy, disastrously this brought out the entire Japanese garrison from the village and all element of surprise was lost. Platoon 17 were soon pinned down by Japanese mortar fire and snipers in the nearby trees took pot shots at the men as they scrambled for cover. It was during these early exchanges that Pte. Arthur Birch was killed.

Here is how Tony Aubrey remembers the action at Baw on 23rd March 1943:

"We took up a defensive position on the crest of a small rise on the edge of the woodland. Visibility was barely 10 yards forwards as the enemy opened fire on us. Our unit soon suffered casualties, Pte. Birch was killed, with no fewer than 17 bullets finding him out. Lambert was shot in the chest, Yates in the hand and shoulder and Suddery received a bullet which went through his right bicep, punctured his ribs and exited through his stomach. In spite of his wounds Suddery continued to fire his Bren from the hip as we attempted to retreat into the woods."

To read more about the death of Pte. Birch and the action at Baw, please click on the following link: Arthur Birch and Platoon 17

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the first part of this story, including a map of the area around the Burmese village of Baw. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Here is how Sergeant Tony Aubrey remembers his commander: "There is only one word to use about Major Scott, he was a smasher. He had personality, courage, foresight, and the greatest of all qualities in a leader, luck. He had been a Lance Corporal during the battle of France and so he knew the mens point of view. He had as much time for the thoughts and ideas of the humble private, as he had for his second in command. He respected his men and they would follow him anywhere."

Platoon 17 was made up of many fine characters, mostly from the north of England, but with a couple of Londoners thrown in for good measure. Here is how Tony remembered those first few weeks inside Burma and the men he came to rely on:

"The platoon slowly began to get to know each other. On the long night time halts in bivouac there was nothing else to do other than talk about our families, previous experiences and our hopes and fears about what might lie ahead in the coming days.

Our platoon Sergeant was Tom Quick, a genial type of chap from Manchester. He was the last sort of fellow you would ever had thought likely to get himself mixed up in a war. Poor Tommy only ever wanted to get back home to his family whom he clearly loved dearly. Then there was Corporal Walsh, who was also from Manchester. He was a ginger headed lad, but his nature belied the colour of his hair, as a cooler customer you could never wish to meet.

Norman Lambert was from Middlesborough and always seemed to be with his great buddy Arthur Birch. Lambert was a great hand on the piano and Birch was a comical little fellow always ready with a gag. They would have made a great double act in the music halls back home, as they did on the Bren gun in Burma. Another comic in Platoon 17 was Jim Suddery from Islington, London. He was always ready with a crack and his quick-fire Cockney wit contrasted hilariously with the more placid humour of Birch. Jim was number one on another Bren and nothing ever separated him from his beloved gun, it was flesh of his flesh. All in all we were a happy family and got along very well."

On the 16th February 1943, 8 Column reached the village of Tonhe on the western banks of the Chindwin River and crossed over into enemy held territory. After crossing the Chindwin, 8 Column travelled around Burma during the early weeks of the operation in close proximity to Wingate's own Brigade Head Quarters, often protecting their leader against possible enemy attacks. Their first skirmish with the enemy was at Pinlebu, where the Japanese supposedly had a large garrison. The town was attacked by the Chindits, but no enemy were to be found, although some clashes did take place on the main track east of the town with some resulting casualties amongst Scott's men.

While Fergusson and Calvert's columns set about their destructive work upon the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway, 8 Column moved around the locality creating diversions and generally taking up the attention of the Japanese. After several weeks inside Burma and having recently crossed over the Irrawaddy River, Wingate and his Brigade had planned to receive an extremely large supply drop close to the Burmese village of Baw. Unfortunately, it was whilst preparing for this supply drop that things went horribly wrong for Sgt. Aubrey's platoon.

The supply drop at Baw was planned for the 23/24 of March and was to be an extremely large affair, re-supplying around 1300 men from Northern Section. Wingate and his column commanders surveyed maps of the area and chose the drop zone (a succession of dry paddy fields on the outskirts of the village), orders were given for two units to secure the main road leading in and out of the village, one of the road blocks was to be manned by Platoon 17.

The platoon set off to secure the tracks to the east of the village and were supposed to be in place before first light the following morning. The men encountered some dense bamboo jungle during their journey to the agreed location and in the end Captain Coughlan called a halt to proceedings and told the men to bed down for a few hours until there was enough light to complete the march in comfort. This was to prove his unit's undoing and would cost the Captain his rank and his place in Column 8.

At first light the platoon pushed on, but immediately ran into Japanese sentries, a Burma Rifleman shot one of the enemy, disastrously this brought out the entire Japanese garrison from the village and all element of surprise was lost. Platoon 17 were soon pinned down by Japanese mortar fire and snipers in the nearby trees took pot shots at the men as they scrambled for cover. It was during these early exchanges that Pte. Arthur Birch was killed.

Here is how Tony Aubrey remembers the action at Baw on 23rd March 1943:

"We took up a defensive position on the crest of a small rise on the edge of the woodland. Visibility was barely 10 yards forwards as the enemy opened fire on us. Our unit soon suffered casualties, Pte. Birch was killed, with no fewer than 17 bullets finding him out. Lambert was shot in the chest, Yates in the hand and shoulder and Suddery received a bullet which went through his right bicep, punctured his ribs and exited through his stomach. In spite of his wounds Suddery continued to fire his Bren from the hip as we attempted to retreat into the woods."

To read more about the death of Pte. Birch and the action at Baw, please click on the following link: Arthur Birch and Platoon 17

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the first part of this story, including a map of the area around the Burmese village of Baw. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Not long after the engagement at Baw, Wingate called a halt to the operation in Burma, after being instructed by the Army HQ in India to get as many of his now knowledgeable and experienced Chindit Brigade back safely to Allied held territory. Wingate's own Brigade HQ had been shielded by Columns 7 and 8 for most of the operation in 1943 and it was these three groups that found themselves on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River on the 29th March, close to the village of Inywa.

As the men prepared to cross some enemy activity was seen on the far bank. Wingate and his commanders felt that the Japanese posed little threat in their present numbers, and so pressed on with the crossing. Some lead boats did manage to get over, but others came under heavy mortar and machine gun fire and began to get into difficulties.

The crossing at Inywa was duly abandoned, the remaining columns and Wingate's HQ melted back into the jungle on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy. The three units agreed there and then to split up and make their own way back to Allied held territory individually. Column 7 retraced their steps and set off toward the Chinese Yunnan borders. Column 8 under Major Scott headed east towards the Shweli River, while Wingate held back in the jungle at Inywa for over a week, hoping that the Japanese activity in the area would die down and their progress to India could resume unmolested.

Tony Aubrey and 8 Column first attempted to cross the Shweli on the 1st April. Here is how Major Scott recalled this moment in the column's war diary:

Entry dated 1st April 1943:

"Recce of the River Shweli carried out this afternoon, decided to attempt a crossing tonight at point 2563, Wingba Cliffs. Column moved down to the riverbanks at dusk. Rope was got across the fast flowing near side. Captain Williams, Lieutenants Hobday and Horton and 29 Other Ranks crossed to form a protective bridgehead."

The next group led by Sergeant Scruton immediately got into difficulties mid-stream and had to cut the rope away from the main line. This boat drifted away downstream. The crossing was subsequently called off. Captain Williams’s party was ordered to move off west under his leadership."

Sgt. Aubrey remembered the same moment with slightly more candour:

"We reached the River Shweli shortly after nightfall, and received orders to have a meal and rest for a couple of hours before attempting a crossing at moonrise. The Shweli at this point was about 180 yards across. The first fifty yards of water from the southern bank are very deep and flow at about four knots. Then comes a sandbank which stands several feet clear of the water.

We first needed someone to swim the river in order to set the power ropes on the far bank, this way all the party could make their way over by pulling the RAF dinghies hand over hand across the water. Captain Williams was given the honour of taking his platoon across first. At moonrise the first twelve with the Captain included, took their places in the dinghies and the crossing began. At first all went well………………….."

To read more detail about this period and the catastrophe at the Shweli, please click on the following link: The Lost Boat on the Shweli

Leaving Captain Williams to get his group home under his own steam, Major Scott moved the rest of his column away from the banks of the river.

The next day he radioed rear base and ordered the dropping of some RAF dinghies, these duly arrived on the 3rd April and within a matter of hours the rest of 8 Column were over their first watery obstacle. It was shortly after crossing the Shweli that Scott realised that some of his men were in a very bad way, some pained by wounds incurred during the recent battles with the enemy and others suffering from jungle maladies of one sort or another. He pondered long and hard about what he should do with these men.

It was decided that a break-away party would be arranged, led by the column Medical Officer, Captain J.D.S. Heathcote, who would attempt to find a friendly Burmese village in which to leave these ailing soldiers. On the 15th April this dispersal group, which included senior Burma Rifles Officer, Captain Nigel Whitehead and Sgt. Aubrey, headed away from the main body of 8 Column in search of a suitable Kachin village for the purpose of depositing their wounded and sick.

Tony Aubrey describes that moment:

"Another decision was also arrived at now, and this the hardest that anyone could be called upon to make. We had carried with us since the action of the previous day three wounded men whose hurts were so serious that they could not walk. Two of these were British and one Burmese. We had no proper stretchers to carry them on, and had improvised litters for them out of bamboo.

The jungle which now lay before us was to all intents and purposes virgin. To make our way through it unburdened would be a task of the utmost difficulty. To carry litters through it would be a virtual impossibility. The discomfort to which the wounded men themselves would be put on such a journey would be horrible, and would in all probability aggravate their injuries to a fatal extent. Both they themselves and the remainder of the column would stand a better chance of survival if they were left behind. The situation was put to them, and they at once agreed, like the men they were."

Finding a suitable village proved much more difficult than was first thought. Many of the hamlets suggested on the maps held by the Chindits no longer existed, having moved to pastures new after exhausting the land on which they originally stood. Heathcote's party never re-joined the rest of the column and it is not really known what befell the afflicted soldiers in his care, although the Medical Officer himself did survive. Sgt. Aubrey had been sent back to find Major Scott in order to inform him of the Medical Officer's struggles to find solace for his men. Tony found himself alone in the jungle for many hours during this short period and the experience was not a pleasant one for the isolated Sergeant.

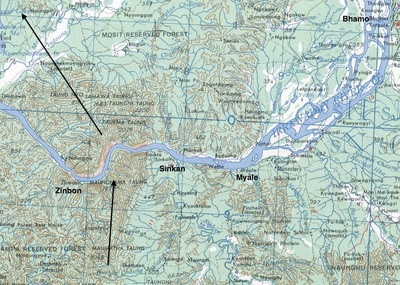

In the meantime, Major Scott and the rest of Column 8 now found themselves up against their next great obstacle, the Irrawaddy River. The Japanese, now completely aware of the Chindits intentions had removed all boats from the banks of the river and now patrolled the waters in motor launches between the villages of Zinbon and Myale. Tony Aubrey expressed the views of the men:

"We saw and heard nothing of the enemy. But, always on our left, lurking like some inescapable monster, lay the implacable Irrawaddy. It had begun to be almost an obsession with us now, this river. There it lay, flowing calmly and serenely southwards. But, however much water flowed down, there was always enough left to act as a seemingly impassible barrier between ourselves and home. It had assumed a personality. I was surprised that I didn't dream about it at night."

Suddenly, on the 20th April, Scott noticed a Burmese junk making its way down river close to where the Chindits were lying up. He seized his chance and with the assistance of Lieutenant George Borrow and Havildar Lanval of the Burma Rifles, hijacked the boat. Paying the junks owner handsomely in silver rupees, the column were over the river in just less than ninety minutes. Hurriedly, the Chindits melted away into the scrub jungle on the far bank and headed roughly north-west.

Seen below is a map of the Irrawaddy around the area of Zinbon, the crossing point for 8 Column on the 20th April 1943. Also shown is a photograph of the river at this point taken in 2013. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

As the men prepared to cross some enemy activity was seen on the far bank. Wingate and his commanders felt that the Japanese posed little threat in their present numbers, and so pressed on with the crossing. Some lead boats did manage to get over, but others came under heavy mortar and machine gun fire and began to get into difficulties.

The crossing at Inywa was duly abandoned, the remaining columns and Wingate's HQ melted back into the jungle on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy. The three units agreed there and then to split up and make their own way back to Allied held territory individually. Column 7 retraced their steps and set off toward the Chinese Yunnan borders. Column 8 under Major Scott headed east towards the Shweli River, while Wingate held back in the jungle at Inywa for over a week, hoping that the Japanese activity in the area would die down and their progress to India could resume unmolested.

Tony Aubrey and 8 Column first attempted to cross the Shweli on the 1st April. Here is how Major Scott recalled this moment in the column's war diary:

Entry dated 1st April 1943:

"Recce of the River Shweli carried out this afternoon, decided to attempt a crossing tonight at point 2563, Wingba Cliffs. Column moved down to the riverbanks at dusk. Rope was got across the fast flowing near side. Captain Williams, Lieutenants Hobday and Horton and 29 Other Ranks crossed to form a protective bridgehead."

The next group led by Sergeant Scruton immediately got into difficulties mid-stream and had to cut the rope away from the main line. This boat drifted away downstream. The crossing was subsequently called off. Captain Williams’s party was ordered to move off west under his leadership."

Sgt. Aubrey remembered the same moment with slightly more candour:

"We reached the River Shweli shortly after nightfall, and received orders to have a meal and rest for a couple of hours before attempting a crossing at moonrise. The Shweli at this point was about 180 yards across. The first fifty yards of water from the southern bank are very deep and flow at about four knots. Then comes a sandbank which stands several feet clear of the water.

We first needed someone to swim the river in order to set the power ropes on the far bank, this way all the party could make their way over by pulling the RAF dinghies hand over hand across the water. Captain Williams was given the honour of taking his platoon across first. At moonrise the first twelve with the Captain included, took their places in the dinghies and the crossing began. At first all went well………………….."

To read more detail about this period and the catastrophe at the Shweli, please click on the following link: The Lost Boat on the Shweli

Leaving Captain Williams to get his group home under his own steam, Major Scott moved the rest of his column away from the banks of the river.

The next day he radioed rear base and ordered the dropping of some RAF dinghies, these duly arrived on the 3rd April and within a matter of hours the rest of 8 Column were over their first watery obstacle. It was shortly after crossing the Shweli that Scott realised that some of his men were in a very bad way, some pained by wounds incurred during the recent battles with the enemy and others suffering from jungle maladies of one sort or another. He pondered long and hard about what he should do with these men.

It was decided that a break-away party would be arranged, led by the column Medical Officer, Captain J.D.S. Heathcote, who would attempt to find a friendly Burmese village in which to leave these ailing soldiers. On the 15th April this dispersal group, which included senior Burma Rifles Officer, Captain Nigel Whitehead and Sgt. Aubrey, headed away from the main body of 8 Column in search of a suitable Kachin village for the purpose of depositing their wounded and sick.

Tony Aubrey describes that moment:

"Another decision was also arrived at now, and this the hardest that anyone could be called upon to make. We had carried with us since the action of the previous day three wounded men whose hurts were so serious that they could not walk. Two of these were British and one Burmese. We had no proper stretchers to carry them on, and had improvised litters for them out of bamboo.

The jungle which now lay before us was to all intents and purposes virgin. To make our way through it unburdened would be a task of the utmost difficulty. To carry litters through it would be a virtual impossibility. The discomfort to which the wounded men themselves would be put on such a journey would be horrible, and would in all probability aggravate their injuries to a fatal extent. Both they themselves and the remainder of the column would stand a better chance of survival if they were left behind. The situation was put to them, and they at once agreed, like the men they were."

Finding a suitable village proved much more difficult than was first thought. Many of the hamlets suggested on the maps held by the Chindits no longer existed, having moved to pastures new after exhausting the land on which they originally stood. Heathcote's party never re-joined the rest of the column and it is not really known what befell the afflicted soldiers in his care, although the Medical Officer himself did survive. Sgt. Aubrey had been sent back to find Major Scott in order to inform him of the Medical Officer's struggles to find solace for his men. Tony found himself alone in the jungle for many hours during this short period and the experience was not a pleasant one for the isolated Sergeant.

In the meantime, Major Scott and the rest of Column 8 now found themselves up against their next great obstacle, the Irrawaddy River. The Japanese, now completely aware of the Chindits intentions had removed all boats from the banks of the river and now patrolled the waters in motor launches between the villages of Zinbon and Myale. Tony Aubrey expressed the views of the men:

"We saw and heard nothing of the enemy. But, always on our left, lurking like some inescapable monster, lay the implacable Irrawaddy. It had begun to be almost an obsession with us now, this river. There it lay, flowing calmly and serenely southwards. But, however much water flowed down, there was always enough left to act as a seemingly impassible barrier between ourselves and home. It had assumed a personality. I was surprised that I didn't dream about it at night."

Suddenly, on the 20th April, Scott noticed a Burmese junk making its way down river close to where the Chindits were lying up. He seized his chance and with the assistance of Lieutenant George Borrow and Havildar Lanval of the Burma Rifles, hijacked the boat. Paying the junks owner handsomely in silver rupees, the column were over the river in just less than ninety minutes. Hurriedly, the Chindits melted away into the scrub jungle on the far bank and headed roughly north-west.

Seen below is a map of the Irrawaddy around the area of Zinbon, the crossing point for 8 Column on the 20th April 1943. Also shown is a photograph of the river at this point taken in 2013. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Being across the river was not the end of 8 Column's troubles. It had been roughly eight weeks since the Chindits first entered enemy territory and the trials of the operation were now beginning to take their toll. Tony Aubrey remembered:

Long marches, scanty and irregular food, lack of water, heat, fever, mosquitos, short rations of sleep, and, by far the worst of all, the constant uncertainty of life in an enemy country, had taken their toll. It was all we could do to force ourselves along, and the very thought of any extra burden was utterly intolerable.

The Bren guns, which in early days had been carried by one man for four and five hours at a stretch, could now be seen changing hands every ten or fifteen minutes. That night one man (Corporal Edward Worsley), whose feet were in a very bad state, made up his mind he could go no further. He lay down. His mates, worn out as they were, tried to carry him. But he wouldn't allow them to. All he wanted was to be left alone with as many hand grenades as we could spare. So we gave him the grenades and left him. There wasn't anything else to do.

Another man (Pte. Robert Hulse), the same night, took a false step, and fell over the thud (banking or precipice). He didn't fall far, but he landed awkwardly, and ruptured himself. We had no M.O. (Captain Heathcote) with us now, he having gone on with Captain Whitehead and the stretcher cases, but we bandaged his hernia up as well as we could with a shell dressing, and he marched on. He was soon at the rear of the column. Sometimes he was ten yards behind us, sometimes a hundred, sometimes he was lost to view altogether. At first we worried about him. "How's so-and-so making out?" we asked each other. But after a time we forgot him, he was just another bit of the landscape. This must sound like a case of man's inhumanity to man, but it wasn't you know. We were just too tired to care.

Not long after this unhappy incident, 8 Column's luck changed and for some men a life-saving miracle would see them being back safely in India within the next 48 hours. Firstly, I will let Sgt. Aubrey describe the scene, after which I will leave the entries in the column war diary narrate what followed next:

That evening, we were drawing near the place which Major Scott had given as the place for the dropping from the air. The jungle was thick here, and it looked as though we might have difficulty, first, in contacting the plane, and second, in retrieving what they dropped. It looked as though the spot chosen without knowledge of the country and only from our maps which were not perfect, was to turn out to be by no means an ideal one.

However, the luck of the Scott's held good. About 6.30, we suddenly emerged from thick jungle to find ourselves on the edge of a clearing. It was like coming out of the densest wood on to the middle of an English meadow. There was not even scrub growing in this clearing, just short grass. There was one thought in all our minds. Tommy Vann, as usual, put it into words. "Bring on the ruddy Air Force!" he said. It was hard to believe that this open space had not been made by hands. It was in the shape of an enormous "T." We were standing at the foot of the upright, which was 400 yards wide and 1200 yards long. The stroke was 300 yards wide and 800 yards long. It was a perfect natural aerodrome.

We all thought, if only a flight of passenger planes could suddenly appear, sweep down to a landing and carry off the whole shooting match of us back to India. I wouldn't have cared even if they had been Harrows (Handley Page Harrow, a large and ungainly bomber aircraft). Scottie had done it again. There shouldn't be any trouble about the dropping tomorrow. On that comforting thought we lay down, and went to sleep.

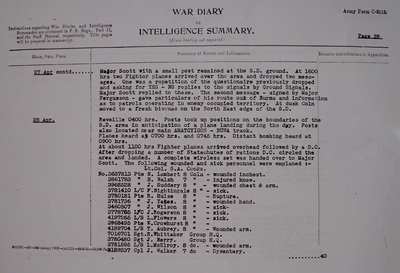

From the 8 Column war diary, covering the dates 24-28th April 1943:

During march Cpl. Walker who had dysentery for 14 days and 3 Gurkhas, fell out from exhaustion. Cpl. Walker was left in Mezaligon village and told to catch up at the S.D. ground if he could make it. Major Scott took foraging party into the village while C.O. took rest of Column through the village to a R.V. on the track North of the village. Foraging party succeeded in getting 3 x chickens and sufficient rice to give each man enough for two meals. Gurkhas were given a very much larger share. Burma Rifles had managed to get cooked rice and some vegetables and date sugar.

Villagers reported that Japs had visited the village a month earlier, had taken rice, pigs, fowls and eggs. The headman of the village had gone to Shwego by order of the Japs - presumably about taxes and rations supply. Japs said to patrol in parties of 20/30 with bullock carts and elephants. They did not go into the jungle or mountains but kept to tracks. It was noted that most of the money in circulation was Japanese paper issue. After issuing the rice the column moved along the Sonpu track crossing the Patin Hka, a good running stream, intending to make as near as possible to the line of flight to be used by planes for the supply drop at 1500 hrs.

About 1 mile west of the Patin Hka we found a large open space running North, so dispersed off the track on to the maidan and thence along the jungle on the eastern edge. At 1200 hours lit fires and cooked rice and made tea. At 1300 hrs prepared Supply Drop ground and put out defences. A message "COULD PLANE LAND HERE" was put out in maps, as it was thought possible a plane could land on this particular area. Supply plane arrived at 1445 hrs - earlier than expected - and dropped 5 days rations, Tommy Guns, waterproof capes, bully, cheese and chocolate. Plane lowered undercarriage and tried to land but failed. It then made off to the west in a great hurry. Shortly afterwards a thunderstorm burst, hail stones the size of marbles fell and all the troops started collecting them to eat.

Only half our demands had been dropped to us. It was thought that the remaining supplies would be dropped later in the day, but no planes arrived. Decided to go into bivouac for the night and wait to see if a plane would come the next day. Four fighters had accompanied the Dakota, but had left in a great hurry presumably to avoid the storm. Troops warned not to eat up their rations untill a second drop had been made.

Reveille 0430 hrs. Major Scott and party moved to drop zone area. At 0600 hrs a plane was heard and further Supply drop carried out. Another five day's rations dropped including more bully, cheese, mail, papers, oil, atrebrin, medical stores, charged battery and waterproof capes. No clothing dropped, message dated 25 April from Officer Commanding RAF Transport Squadron dropped, asking for particulars to be sent by wireless regarding possibility of a landing ground. Unable to reply to message as the wireless had already been jettisoned. Message put out on ground saying "No W/T" but it was thought that the plane had gone before message had been completed.

Rations sorted out and issued, as a result many men had ten days rations, two tins of bully, one tin cheese, and a portion of rice, sufficient to carry him on for three weeks if necessary without having to live on the country. Moved back into bivouac for the night leaving a post on the supply drop ground in case a recce plane was sent over the next day.

It had been hoped particularly that a new shirt and pair of trousers would be dropped for each man. The clothing of the column is now just dropping to pieces. Many have no sleeves to their shirts, no seats to their trousers and many pairs of trousers have had to be cut down as shorts - with the result that at night men are pestered by mosquitoes. At least 90% of the clothing is lice infested, for the past ten days it has been a regular proceeding for men to take shirts and trousers off during halts to remove lice, a never ending task.

During the next afternoon all troops sent down to the stream close to the bivouac to bathe. Remained in the same bivouac for the night. Major Scott with a small group remained at the supply drop ground. At 1600 hrs two fighter planes arrived over the area and dropped two messages. One was a repetition of the questionnaire previously dropped and asking for YES - NO replies to the signals. Major Scott replied to these. The second message - signed by Major Fergusson - gave particulars of his route out of Burma and informed as to patrols operating in enemy occupied territory. At dusk the column moved to a fresh bivouac on the North East edge of the drop zone.

28th April: Reveille 0400 hrs. Posts took up positions on the boundaries of S.D. area in anticipation of a plane landing during the day. Posts also located near main Amatgyigon-Buwa track. Planes heard at 0700 and 0745 hrs. Distant bombing heard at 0900 hrs. At about 1100 hrs fighter planes arrived overhead followed by a Dakota. After dropping a number of statachutes of rations, the Dakota circled the area and landed. A complete wireless set was handed over to Major Scott.

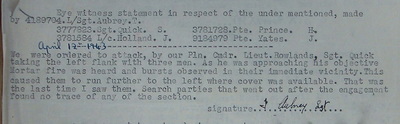

The following wounded and sick personnel were emplaned.

Lieutenant-Colonel S.A. Cooke.

3657813 Pte. N. Lambert 8 Coln. - wounded in chest.

3861783 Pte. H. Walsh 7 Coln. - injured knee.

3968528 Pte. J. Suddery 8 Coln. - wounded chest & arm.

3781410 L/C. F. Nightingale 8 Coln. - sick.

3780181 Pte. R. Hulse 8 Coln.- Rupture.

3781736 Pte. J. Yates. 8 Coln. - wounded hand.

3460507 Pte. J. Wilson 8 Coln. - sick.

3778705 L/C. J. Rogerson 8 Coln. - sick.

4197265 L/S. L. Flowers 8 Coln. - sick.

3968495 Pte. W. Crowhurst 8 Coln.

4189704 L/S. T. Aubrey. 8 Coln. - Wounded arm.

7016701 Sgt. E.Whittaker Group H.Q.

3780480 Sgt. J. Berry. Group H.Q.

3781595 L/S. L. McElroy. 8 Coln.- wounded arm.

3189237 Cpl. J. Walker 7 Coln.- dysentery.

3823 Rfm.Tun Tin. 2nd Burma Rifles - Malaria.

10468 Rfm. Kalabahadur 3/2 Gurkha Rifles

NB. In regard to the above mentioned soldiers. Some men from Northern Group Head Quarters commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Cooke and 7 Column had joined up with Scott's unit at the aborted crossing of the Irrawaddy on the 29th March.

Back at the landing ground eight Fighters circled overhead while the Dakota was collecting its new cargo. As soon as the party had emplaned, the Dakota taxied to the end of the straight and took off. Two Fighters escorted it to Imphal where the wounded and sick men were taken to the 19th Casualty Clearing Station for treatment. The Commander of 4 Corps, after receiving reports from Colonel Cooke and the pilot of the Dakota (Flight Officer Vlasto) decided that it was not possible to evacuate all Major Scott's party by air. He was now satisfied that Scott had been relieved of all sick and wounded personnel, that owing to the shortage of transport planes no undue risks could be undertaken and that Major Scott's party was adequately rationed for the march out.

On the 29th April Fighter planes were sent to drop a message to this effect to Major Scott; this was followed by a Dakota which dropped more clothing, cardigans, medical comforts and a number of up to date maps for the column. Further instructions regarding the suggested route out of Burma were also dropped.

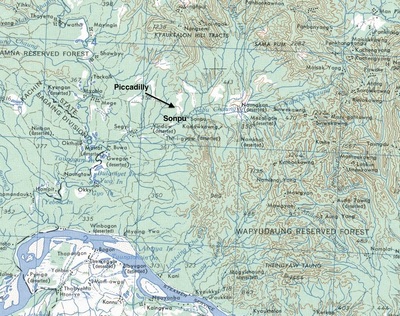

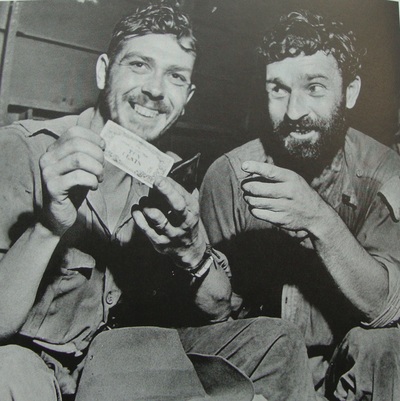

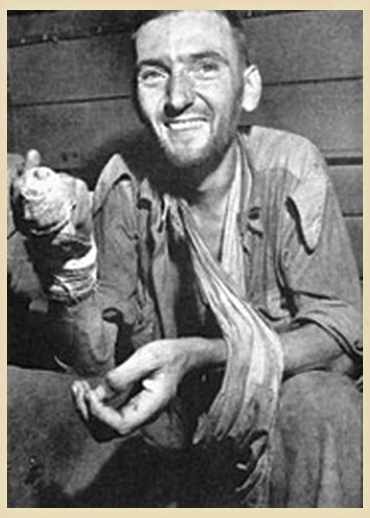

Seen below is a famous photograph showing Tony Aubrey (left) chatting to Pte. Robert Hulse, the soldier who had ruptured himself when he stumbled over on the jungle track just before 8 Column reached the drop zone clearing. They are pictured aboard the Dakota aircraft which flew the fortunate few back to India. The jungle clearing was earmarked to be used again the following year, to land part of Wingate's invasion force spearheading the second Chindit operation. It was codenamed 'Piccadilly' but, as fate would have it, the clearing was never used. Even so, it has become part of Chindit folklore.

Long marches, scanty and irregular food, lack of water, heat, fever, mosquitos, short rations of sleep, and, by far the worst of all, the constant uncertainty of life in an enemy country, had taken their toll. It was all we could do to force ourselves along, and the very thought of any extra burden was utterly intolerable.

The Bren guns, which in early days had been carried by one man for four and five hours at a stretch, could now be seen changing hands every ten or fifteen minutes. That night one man (Corporal Edward Worsley), whose feet were in a very bad state, made up his mind he could go no further. He lay down. His mates, worn out as they were, tried to carry him. But he wouldn't allow them to. All he wanted was to be left alone with as many hand grenades as we could spare. So we gave him the grenades and left him. There wasn't anything else to do.

Another man (Pte. Robert Hulse), the same night, took a false step, and fell over the thud (banking or precipice). He didn't fall far, but he landed awkwardly, and ruptured himself. We had no M.O. (Captain Heathcote) with us now, he having gone on with Captain Whitehead and the stretcher cases, but we bandaged his hernia up as well as we could with a shell dressing, and he marched on. He was soon at the rear of the column. Sometimes he was ten yards behind us, sometimes a hundred, sometimes he was lost to view altogether. At first we worried about him. "How's so-and-so making out?" we asked each other. But after a time we forgot him, he was just another bit of the landscape. This must sound like a case of man's inhumanity to man, but it wasn't you know. We were just too tired to care.

Not long after this unhappy incident, 8 Column's luck changed and for some men a life-saving miracle would see them being back safely in India within the next 48 hours. Firstly, I will let Sgt. Aubrey describe the scene, after which I will leave the entries in the column war diary narrate what followed next:

That evening, we were drawing near the place which Major Scott had given as the place for the dropping from the air. The jungle was thick here, and it looked as though we might have difficulty, first, in contacting the plane, and second, in retrieving what they dropped. It looked as though the spot chosen without knowledge of the country and only from our maps which were not perfect, was to turn out to be by no means an ideal one.

However, the luck of the Scott's held good. About 6.30, we suddenly emerged from thick jungle to find ourselves on the edge of a clearing. It was like coming out of the densest wood on to the middle of an English meadow. There was not even scrub growing in this clearing, just short grass. There was one thought in all our minds. Tommy Vann, as usual, put it into words. "Bring on the ruddy Air Force!" he said. It was hard to believe that this open space had not been made by hands. It was in the shape of an enormous "T." We were standing at the foot of the upright, which was 400 yards wide and 1200 yards long. The stroke was 300 yards wide and 800 yards long. It was a perfect natural aerodrome.

We all thought, if only a flight of passenger planes could suddenly appear, sweep down to a landing and carry off the whole shooting match of us back to India. I wouldn't have cared even if they had been Harrows (Handley Page Harrow, a large and ungainly bomber aircraft). Scottie had done it again. There shouldn't be any trouble about the dropping tomorrow. On that comforting thought we lay down, and went to sleep.

From the 8 Column war diary, covering the dates 24-28th April 1943:

During march Cpl. Walker who had dysentery for 14 days and 3 Gurkhas, fell out from exhaustion. Cpl. Walker was left in Mezaligon village and told to catch up at the S.D. ground if he could make it. Major Scott took foraging party into the village while C.O. took rest of Column through the village to a R.V. on the track North of the village. Foraging party succeeded in getting 3 x chickens and sufficient rice to give each man enough for two meals. Gurkhas were given a very much larger share. Burma Rifles had managed to get cooked rice and some vegetables and date sugar.

Villagers reported that Japs had visited the village a month earlier, had taken rice, pigs, fowls and eggs. The headman of the village had gone to Shwego by order of the Japs - presumably about taxes and rations supply. Japs said to patrol in parties of 20/30 with bullock carts and elephants. They did not go into the jungle or mountains but kept to tracks. It was noted that most of the money in circulation was Japanese paper issue. After issuing the rice the column moved along the Sonpu track crossing the Patin Hka, a good running stream, intending to make as near as possible to the line of flight to be used by planes for the supply drop at 1500 hrs.

About 1 mile west of the Patin Hka we found a large open space running North, so dispersed off the track on to the maidan and thence along the jungle on the eastern edge. At 1200 hours lit fires and cooked rice and made tea. At 1300 hrs prepared Supply Drop ground and put out defences. A message "COULD PLANE LAND HERE" was put out in maps, as it was thought possible a plane could land on this particular area. Supply plane arrived at 1445 hrs - earlier than expected - and dropped 5 days rations, Tommy Guns, waterproof capes, bully, cheese and chocolate. Plane lowered undercarriage and tried to land but failed. It then made off to the west in a great hurry. Shortly afterwards a thunderstorm burst, hail stones the size of marbles fell and all the troops started collecting them to eat.

Only half our demands had been dropped to us. It was thought that the remaining supplies would be dropped later in the day, but no planes arrived. Decided to go into bivouac for the night and wait to see if a plane would come the next day. Four fighters had accompanied the Dakota, but had left in a great hurry presumably to avoid the storm. Troops warned not to eat up their rations untill a second drop had been made.

Reveille 0430 hrs. Major Scott and party moved to drop zone area. At 0600 hrs a plane was heard and further Supply drop carried out. Another five day's rations dropped including more bully, cheese, mail, papers, oil, atrebrin, medical stores, charged battery and waterproof capes. No clothing dropped, message dated 25 April from Officer Commanding RAF Transport Squadron dropped, asking for particulars to be sent by wireless regarding possibility of a landing ground. Unable to reply to message as the wireless had already been jettisoned. Message put out on ground saying "No W/T" but it was thought that the plane had gone before message had been completed.

Rations sorted out and issued, as a result many men had ten days rations, two tins of bully, one tin cheese, and a portion of rice, sufficient to carry him on for three weeks if necessary without having to live on the country. Moved back into bivouac for the night leaving a post on the supply drop ground in case a recce plane was sent over the next day.

It had been hoped particularly that a new shirt and pair of trousers would be dropped for each man. The clothing of the column is now just dropping to pieces. Many have no sleeves to their shirts, no seats to their trousers and many pairs of trousers have had to be cut down as shorts - with the result that at night men are pestered by mosquitoes. At least 90% of the clothing is lice infested, for the past ten days it has been a regular proceeding for men to take shirts and trousers off during halts to remove lice, a never ending task.

During the next afternoon all troops sent down to the stream close to the bivouac to bathe. Remained in the same bivouac for the night. Major Scott with a small group remained at the supply drop ground. At 1600 hrs two fighter planes arrived over the area and dropped two messages. One was a repetition of the questionnaire previously dropped and asking for YES - NO replies to the signals. Major Scott replied to these. The second message - signed by Major Fergusson - gave particulars of his route out of Burma and informed as to patrols operating in enemy occupied territory. At dusk the column moved to a fresh bivouac on the North East edge of the drop zone.

28th April: Reveille 0400 hrs. Posts took up positions on the boundaries of S.D. area in anticipation of a plane landing during the day. Posts also located near main Amatgyigon-Buwa track. Planes heard at 0700 and 0745 hrs. Distant bombing heard at 0900 hrs. At about 1100 hrs fighter planes arrived overhead followed by a Dakota. After dropping a number of statachutes of rations, the Dakota circled the area and landed. A complete wireless set was handed over to Major Scott.

The following wounded and sick personnel were emplaned.

Lieutenant-Colonel S.A. Cooke.

3657813 Pte. N. Lambert 8 Coln. - wounded in chest.

3861783 Pte. H. Walsh 7 Coln. - injured knee.

3968528 Pte. J. Suddery 8 Coln. - wounded chest & arm.

3781410 L/C. F. Nightingale 8 Coln. - sick.

3780181 Pte. R. Hulse 8 Coln.- Rupture.

3781736 Pte. J. Yates. 8 Coln. - wounded hand.

3460507 Pte. J. Wilson 8 Coln. - sick.

3778705 L/C. J. Rogerson 8 Coln. - sick.

4197265 L/S. L. Flowers 8 Coln. - sick.

3968495 Pte. W. Crowhurst 8 Coln.

4189704 L/S. T. Aubrey. 8 Coln. - Wounded arm.

7016701 Sgt. E.Whittaker Group H.Q.

3780480 Sgt. J. Berry. Group H.Q.

3781595 L/S. L. McElroy. 8 Coln.- wounded arm.

3189237 Cpl. J. Walker 7 Coln.- dysentery.

3823 Rfm.Tun Tin. 2nd Burma Rifles - Malaria.

10468 Rfm. Kalabahadur 3/2 Gurkha Rifles

NB. In regard to the above mentioned soldiers. Some men from Northern Group Head Quarters commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Cooke and 7 Column had joined up with Scott's unit at the aborted crossing of the Irrawaddy on the 29th March.

Back at the landing ground eight Fighters circled overhead while the Dakota was collecting its new cargo. As soon as the party had emplaned, the Dakota taxied to the end of the straight and took off. Two Fighters escorted it to Imphal where the wounded and sick men were taken to the 19th Casualty Clearing Station for treatment. The Commander of 4 Corps, after receiving reports from Colonel Cooke and the pilot of the Dakota (Flight Officer Vlasto) decided that it was not possible to evacuate all Major Scott's party by air. He was now satisfied that Scott had been relieved of all sick and wounded personnel, that owing to the shortage of transport planes no undue risks could be undertaken and that Major Scott's party was adequately rationed for the march out.

On the 29th April Fighter planes were sent to drop a message to this effect to Major Scott; this was followed by a Dakota which dropped more clothing, cardigans, medical comforts and a number of up to date maps for the column. Further instructions regarding the suggested route out of Burma were also dropped.

Seen below is a famous photograph showing Tony Aubrey (left) chatting to Pte. Robert Hulse, the soldier who had ruptured himself when he stumbled over on the jungle track just before 8 Column reached the drop zone clearing. They are pictured aboard the Dakota aircraft which flew the fortunate few back to India. The jungle clearing was earmarked to be used again the following year, to land part of Wingate's invasion force spearheading the second Chindit operation. It was codenamed 'Piccadilly' but, as fate would have it, the clearing was never used. Even so, it has become part of Chindit folklore.

For more information about the men rescued by the Dakota landing at 'Piccadilly', please click on the following link:

Lance Corporal Fred Nightingale

The story of the 'Piccadilly' landing has been recounted in many books concerning the Chindits, it has also been mentioned on these website pages on several occasions. In his book 'Wingate's Raiders', author, Charles J. Rolo described the events of the 24-28th April 1943, as told to him by some of the survivors from 8 Column:

The rendezvous for the dropping was a clearing near Bhamo, a large town one hundred and fifty miles behind the Japanese lines and not far from the China frontier. On the way to the rendezvous they ran out of rations.

They dared not venture into the villages as the whole area was now heavily patrolled by the enemy. With nothing to eat but bamboo shoots and jungle palms, they began to drop like flies from hunger and disease. Marching along through dark jungle shuttered from the sky with creepers, Major Scott noticed that the track ahead of him was growing lighter, as though he were nearing the end of a tunnel. Quite suddenly he was standing on the edge of the jungle, looking out on to what was probably the only large patch of grassland in Northern Burma. This was the rendezvous.

Next day, with luck, the R.A.F. would drop them food and new equipment. There remained the problem of the sick and wounded. Sheer guts had carried them this far, but Scott knew that not one of them could ever make the long trek to Blighty.

There was Colonel Cooke, one of Wingate's senior officers, weakened with dysentery and covered with deep, festering jungle sores; Corporal Jimmy Walker, who had dropped out of line two days before with dysentery and an infected hip, and had somehow dragged himself along behind them and Lance-Corporal Fred Nightingale, worn to a skeleton by ulcers. Private Robert Hulse had ruptured himself carrying a machine-gun through the hills, and every few hours was seized with violent fits of vomiting. Private Jim Suddery had been shot in the back, and the bullet had gone right through him, leaving a purplish hole in his abdomen, somehow he was still marching. A Burma Rifleman was shivering and sweating with malignant malaria.

These and a dozen others had fought long and well. They must not be left to Japanese bayonets. Scott knew they had only one hope, rescue from the air. He stared out at the clearing. It was bumpy and badly pitted, but a good pilot would have a sporting chance of landing.

He sent for the Sergeant-Major. "Tell the men to tear some parachutes into strips and spell out the words 'PLANE LAND HERE.' Eventually the planes came over and dropped supplies. Circling low, they picked out the message, and one of them pointed its nose to the ground. It skimmed the jagged field and roared up again. The Chindits watched, breathless. Inside the plane Flying Officer Lummie Lord yelled at the crew, "Hold tight, boys, we'll try again." Teeth clenched, drenched with sweat, he put the plane down. The field jumped up at them, rough turf scarred with pot-holes flashed past the windows. Flying Officer Lord (David Lord DFC, VC) cursed savagely into the roar of the engines. Not a hope. He swung his machine into a wide arc and headed for home.

Back at base he reported to Wing Commander Burbury : "It can be done if they mark out a runway." Off went another plane with a message to the Chindits. "Mark out a 200 yard landing-ground to hold a 12-ton transport."

On Tuesday at dawn the rescue plane took off, rocketing into the rising sun with Flying Officer Michael Vlasto at the controls. Before it left the supply officer handed each crew member a pair of army boots. "You may need these," he explained cheerily, "to walk home in." The crew was a mixed lot, catapulted by war from the corners of Empire into a late model American aircraft just out of a California factory.

Vlasto, dark, going bald, hatchet-faced had sandwiched twelve hundred hours flying time between civilian life in Calcutta's jute mills and this April morning. His second, Pilot-Sergeant Frank Murray, had left high school in Kingston Jamaica, to be trained as a flier in the New World. The Empire Air Training Scheme had given him his wings, and chance had picked him out of thousands for duty on the India-Burma front. Vlasto's radio operator, Sergeant Jack Reeves, hailed from Bradford, Ontario. There was no sounder man in the squadron. His mates called him " Happy." They'd never seen him smile. The flight rigger, Sergeant Charles Alfred May, was a mechanic in a garage in Leeds when Hitler invaded Poland. He had worked his way to India by way of the Libyan desert, but close contact with Stukas had not jarred his good humour.

The huge plane picked up fighter escort and stabbed into Burma, cruising easily at 160 m.p.h. "She's a hot crate," Vlasto thought. "But she can't be too hot for this job." Smoke fires pointed the way to the clearing. Vlasto dipped and spotted a white line across the field. Dropping low, he read the message : "Land on white line. Ground there V.G."

First the plane circled, releasing more supplies for the column. Then Vlasto skimmed the landing strip, weighing his chances. It was about eight hundred yards long, four hundred yards too short for comfort. A strong wind was blowing up the runway towards the tall teak forest, two hundred yards beyond where the white line ended. Vlasto knew that if anything went wrong they'd be past needing those boots. "What about it ? he asked the co-pilot." Here's hoping," Murray said fervently. "Plane landing" Vlasto yelled to the crew, and they braced themselves in the rear.

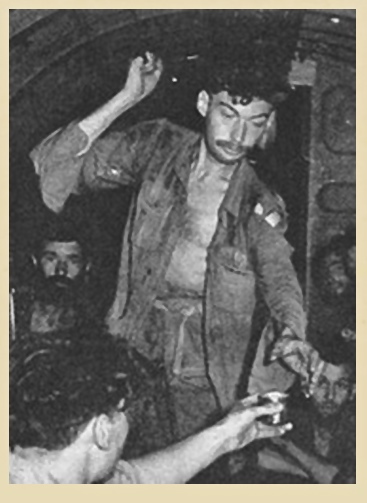

The big transport hit ground and touched down easily. Vlasto braked hard. They pulled up just at the end of the strip and taxied back slowly. A band of hill-billy assassins tumbled out of the jungle and crowded happily around the plane. Mortar and Bren-gun crews remained at their posts. The Japs might attack any minute, it was a miracle they had not discovered the landing-ground days ago. The eighteen sick and wounded filed out from under cover and hobbled towards the plane. Some had to be supported, but they all wore their packs. For every one of them it was a reprieve from certain death.

At the steps of the plane the eighteenth man halted and turned to Major Scott. "I'm all right, sir. I came in on my feet, and I'd like to go out the same way." Scott smiled. "Good man," he said, and No. 18 joined the group posing for a farewell picture. As the crew scrambled into the plane the Chindits waved their hats three times and cheered silently through closed lips. The motors hummed and the door slammed to. Twelve minutes after landing the plane took off with seventeen walking hospital cases.

She lifted slowly, labouring heavily. In the cockpit Vlasto and Murray sat, dead white, with their eyes glued on the teak-trees rushing towards the windshield. The runway was too short and the plane overloaded. Sweat poured down their faces, they were heading straight into the top branches. Vlasto was listening for the crash when the plane heaved and bounced upward. A frantic lift and over she went. Tree-tops flashed below the wing-tips. Murray grinned at Vlasto, "Six inches to spare." Vlasto brushed the sweat off his forehead, "God bless No. 18" he replied.

NB. Sadly No 18, the incredibly brave and fine man that was Sergeant Bert Fitton, never made it out of Burma in 1943, he was lost just a few days later, killed in action during an ambush by a Japanese patrol. It is in fact incorrect to nominate Bert Fitton as number eighteen, according to the personnel listing shown below, there were 16 British soldiers air lifted to India aboard the Dakota, together with one Gurkha Rifleman and one Burma Rifleman. So Sgt. Fitton was actually No. 19.

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/1292591/FITTON,%20HERBERT

Seen below is another group of images in relation to Tony Aubrey's story and in particular, the 'Piccadilly' incident. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Lance Corporal Fred Nightingale

The story of the 'Piccadilly' landing has been recounted in many books concerning the Chindits, it has also been mentioned on these website pages on several occasions. In his book 'Wingate's Raiders', author, Charles J. Rolo described the events of the 24-28th April 1943, as told to him by some of the survivors from 8 Column:

The rendezvous for the dropping was a clearing near Bhamo, a large town one hundred and fifty miles behind the Japanese lines and not far from the China frontier. On the way to the rendezvous they ran out of rations.

They dared not venture into the villages as the whole area was now heavily patrolled by the enemy. With nothing to eat but bamboo shoots and jungle palms, they began to drop like flies from hunger and disease. Marching along through dark jungle shuttered from the sky with creepers, Major Scott noticed that the track ahead of him was growing lighter, as though he were nearing the end of a tunnel. Quite suddenly he was standing on the edge of the jungle, looking out on to what was probably the only large patch of grassland in Northern Burma. This was the rendezvous.

Next day, with luck, the R.A.F. would drop them food and new equipment. There remained the problem of the sick and wounded. Sheer guts had carried them this far, but Scott knew that not one of them could ever make the long trek to Blighty.

There was Colonel Cooke, one of Wingate's senior officers, weakened with dysentery and covered with deep, festering jungle sores; Corporal Jimmy Walker, who had dropped out of line two days before with dysentery and an infected hip, and had somehow dragged himself along behind them and Lance-Corporal Fred Nightingale, worn to a skeleton by ulcers. Private Robert Hulse had ruptured himself carrying a machine-gun through the hills, and every few hours was seized with violent fits of vomiting. Private Jim Suddery had been shot in the back, and the bullet had gone right through him, leaving a purplish hole in his abdomen, somehow he was still marching. A Burma Rifleman was shivering and sweating with malignant malaria.

These and a dozen others had fought long and well. They must not be left to Japanese bayonets. Scott knew they had only one hope, rescue from the air. He stared out at the clearing. It was bumpy and badly pitted, but a good pilot would have a sporting chance of landing.

He sent for the Sergeant-Major. "Tell the men to tear some parachutes into strips and spell out the words 'PLANE LAND HERE.' Eventually the planes came over and dropped supplies. Circling low, they picked out the message, and one of them pointed its nose to the ground. It skimmed the jagged field and roared up again. The Chindits watched, breathless. Inside the plane Flying Officer Lummie Lord yelled at the crew, "Hold tight, boys, we'll try again." Teeth clenched, drenched with sweat, he put the plane down. The field jumped up at them, rough turf scarred with pot-holes flashed past the windows. Flying Officer Lord (David Lord DFC, VC) cursed savagely into the roar of the engines. Not a hope. He swung his machine into a wide arc and headed for home.

Back at base he reported to Wing Commander Burbury : "It can be done if they mark out a runway." Off went another plane with a message to the Chindits. "Mark out a 200 yard landing-ground to hold a 12-ton transport."