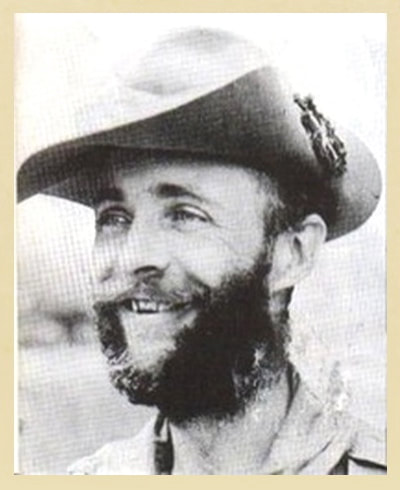

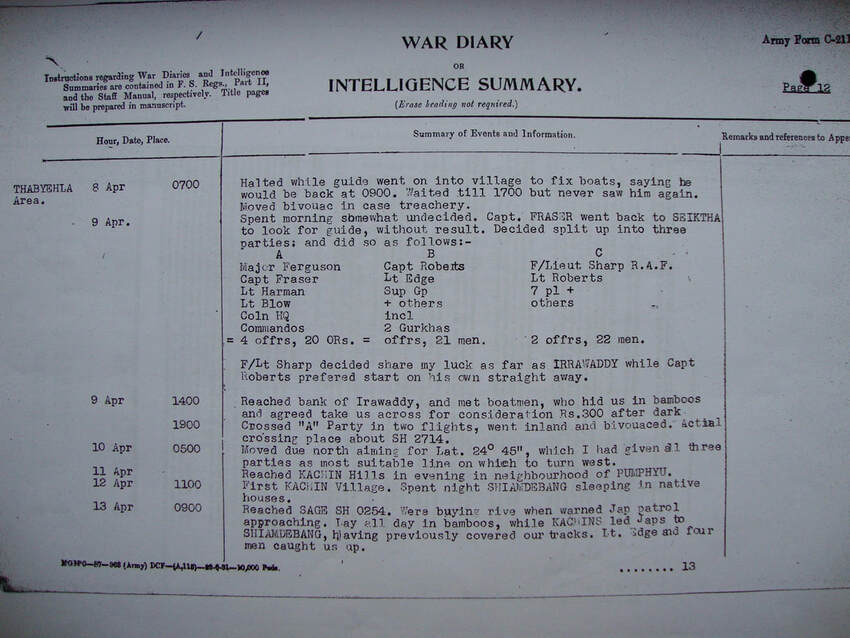

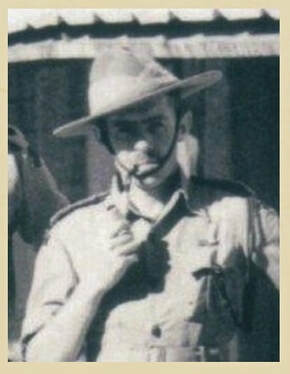

Lieutenant James B. Harman

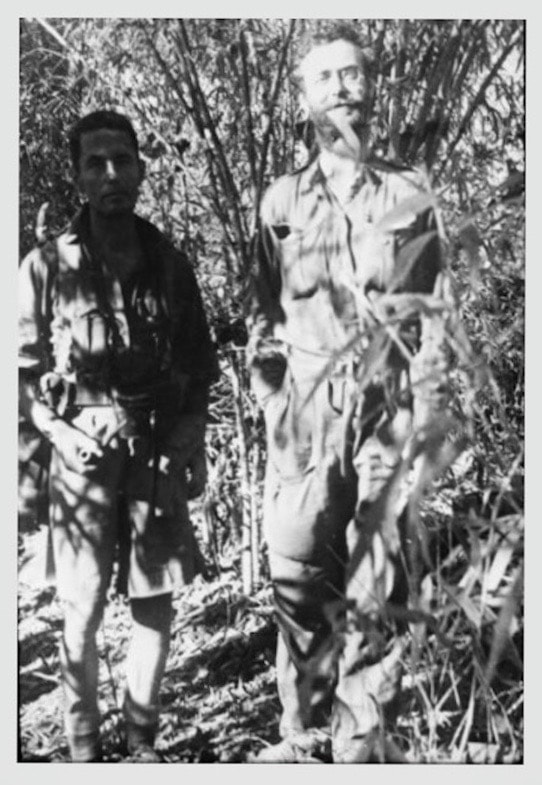

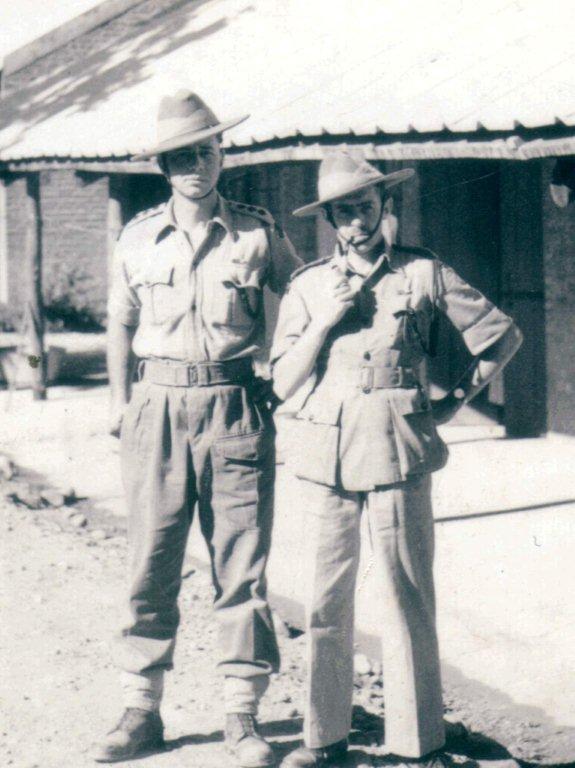

Jim Harman in India, 1944.

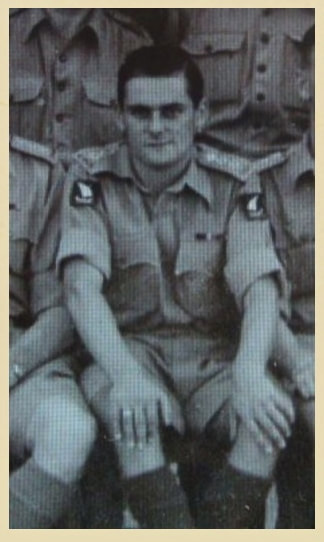

Jim Harman in India, 1944.

James Harman had been in India and Burma for several years before the first Chindit Brigade was formed in July 1942. Originally with the Gloucestershire Regiment, he had become involved with the more clandestine ways of the Army in late 1941, when he joined the Bush Warfare School at Maymyo, commanded and organised at the time by Mike Calvert. It cannot be confirmed, but there is anecdotal evidence to suggest that Lt. Harman had also served in China with 204 Mission, fighting against the Japanese in an unofficial collaboration between Allied Forces and the Chinese Army.

His skills, experience and credentials were clearly suited to Wingate's newly formed Brigade and Harman volunteered for the operation after seeing an advert for commandos on a noticeboard at the Secunderabad cantonment. He commenced his Chindit training with 142 Commando at their Saugor camp in the Central Provinces of India. He was then allocated to lead the Commando Platoon for No. 5 Column in late December 1942, joining Major Fergusson and his team at Jhansi in time for the Christmas celebrations.

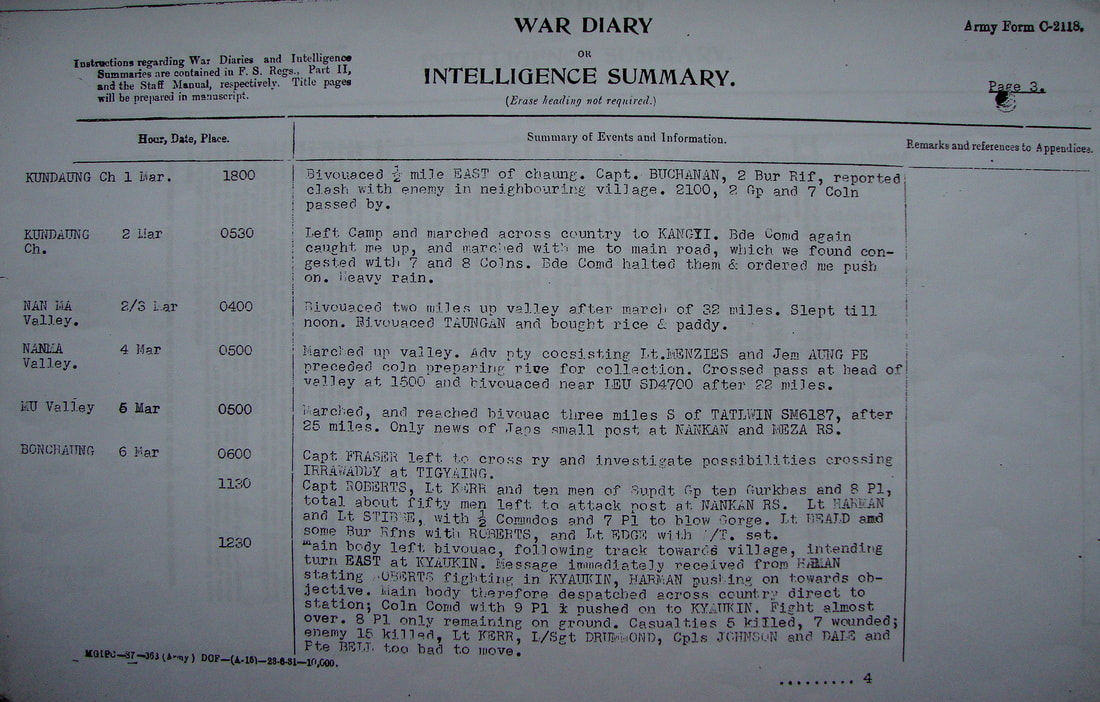

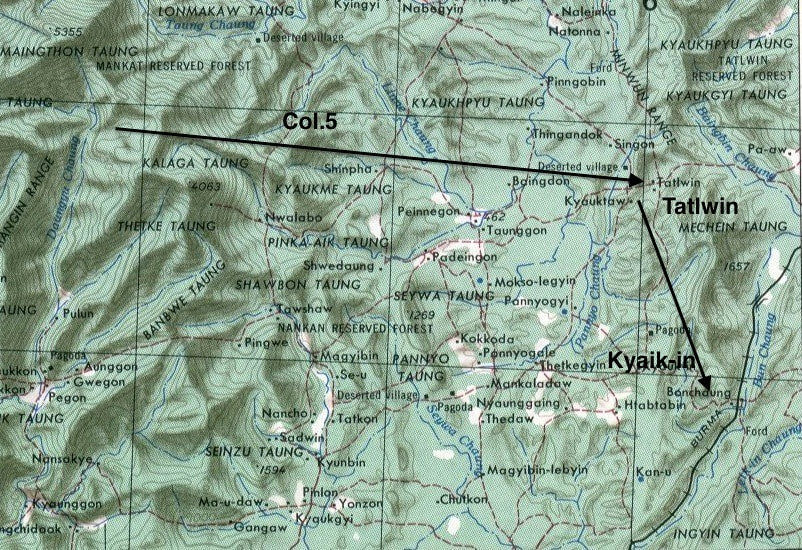

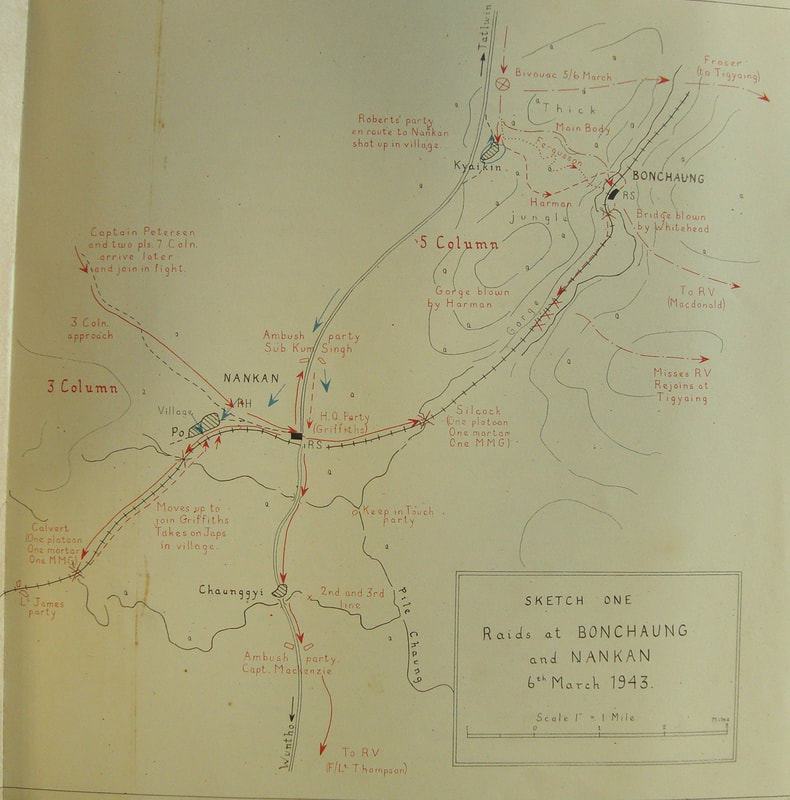

No. 5 Column were given one specific task by Orde Wingate in 1943, this was to destroy the railway bridge and tracks at the village of Bonchaung. Jim Harman's role was to blow the gorge a few miles from the village assisted by Sgt. Pester of the Royal Engineers. Unfortunately, Bernard Fergusson's column were ambushed by the enemy just a few miles north of Bonchaung on the 6th March 1943.

To help set the scene, here is how Bernard Fergusson remembered that day:

On the morning of the 6th of March, everybody got off to time; but before I had marched four hundred yards along the road, Fitzpatrick, Tommy Roberts's groom, came up at a gallop, somewhat flustered. He had been up and down the road for fifteen minutes, unable to spot the point in the jungle where our bivouac had been. (I never bivouacked within five hundred yards of a track).

Tommy was engaged in Kyaik-in village with some Japanese; he had sent Jim Harman back and round to go straight for the gorge, and was fighting it out himself. I asked Fitzpatrick (in civil life a buttons in a Liverpool hotel) for details, but all he knew was that there was a lot of shooting going on, and a lot of bangs, and Tommy had sent him back to warn me. I hastily decided to send the main body straight off across country to Bonchaung. I sent the remaining rifle platoon, now commanded by Gerry Roberts, down the motor-road to the village as fast as it could go, to back up Tommy, while I gave Alec and Duncan their orders. When I had finished, I took Peter Dorans, and followed Gerry.

As I drew near the village, I could hear light machine-guns in action, and the occasional burst of a grenade. The jungle was continuous on the right of the road, but there was a small strip of disused paddy, with some scrubby bushes, on the left; and by the time I arrived (for it took a minute or two to give out the orders to the main body) Gerry's leading Bren section was already in position, and had fired on a small party of Japs. Obsessed with the importance of avoiding a fight with our own troops, I begged him to be careful, and to work gradually along the track. I saw two men of the original party in the bushes on the right, one of whom was Bill Edge's servant, who had been with Tommy: he told me that Bill Edge had been hit, had gone off with Bill Aird to get his wound dressed, and told him to stay by his pack.

By this time all was quiet, except for one light machine-gun firing at us from the south-eastern end of the paddy; but its fire soon ceased, and somebody found the gunner dead by his gun half an hour later. I pushed gingerly forward with a section, and found a fork in the road; one branch, which seemed to be the main road, ran over the hill, and the other went into the village. In the point of the wood at the fork, I saw Private Fairhurst, who called to me that John Kerr was there, wounded. I crossed the road, noticing as I did so two dead Japs, and found John with a painful wound in the calf of the leg, right in the muscle. Beside him were half a dozen Japanese dead and two or three other British dead or wounded: among them was poor Lancaster, the boy who had been one of my swimming instructors, unconscious and almost out.

I offered John some morphia, but he refused it until he had told me his story, in case his brain got muddled, very typical of his devotion to duty. They had walked head-on into a lorry-load of Japs standing in the village: he thought they had just climbed into it after cross-examining the villagers. They had killed several of them at once, but the driver had driven off immediately, with at least two bodies in the back, to the south. They thought they had killed everybody, for the loss of two killed and Bill Edge and one or two others wounded; and Tommy Roberts had gone on. John was waiting only to collect his platoon, when suddenly a new light machine-gun had opened up, and hit him and several more.

While he was telling me this, there was a sudden report just beside my ear, and I spun round to find Peter Doran with a smoking rifle, and one of the two "dead" Japs in the road writhing. He had suddenly flung himself up on his elbow and pointed his rifle at me. Peter shot him again and finally dispatched him.

Bernard Fergusson continues:

What to do with the wounded ? The problem we had all so long dreaded had at last arisen. There were five of them unfit to move, and by bad luck they included not only John but his platoon serjeant and two of his section commanders: they had all been together at the fatal moment. The truck had got away, and there was no knowing when the Japs would come back on us.

We hoisted three of them on to mules, and bore them down to the village a hundred yards away; and there we left them with their packs, and earthen jugs of water, in the shade under one of the houses. One of them said, "Thank God, no more walking for a bit"; one, Corporal Dale, said, "See and make a good job of that bridge;" and John Kerr said, "Don't you worry about us, sir, we'll be all right." The other two were too sick to move, and we had to be content with telling John Kerr where we had left them.

Sixteen dead Japanese were counted in and around the village. It was thought that the one who got away in the lorry was the only survivor. One Gurkha Naik, by the name of Jhuriman Rai, one of six whom I had sent with Tommy as a change from muleteering, killed no less than five of them, three with his rifle and two with his kukri. Five bullet-holes were found in his clothing and equipment afterwards. With Gerry Roberts's platoon, and with the much saddened platoon of John Kerr, I sought the track to Bonchaung, but could find no trace of it. To the south we heard various explosions; we knew it could not be Jim Harman already, and rightly guessed it was Mike Calvert celebrating his thirtieth birthday on the railway.

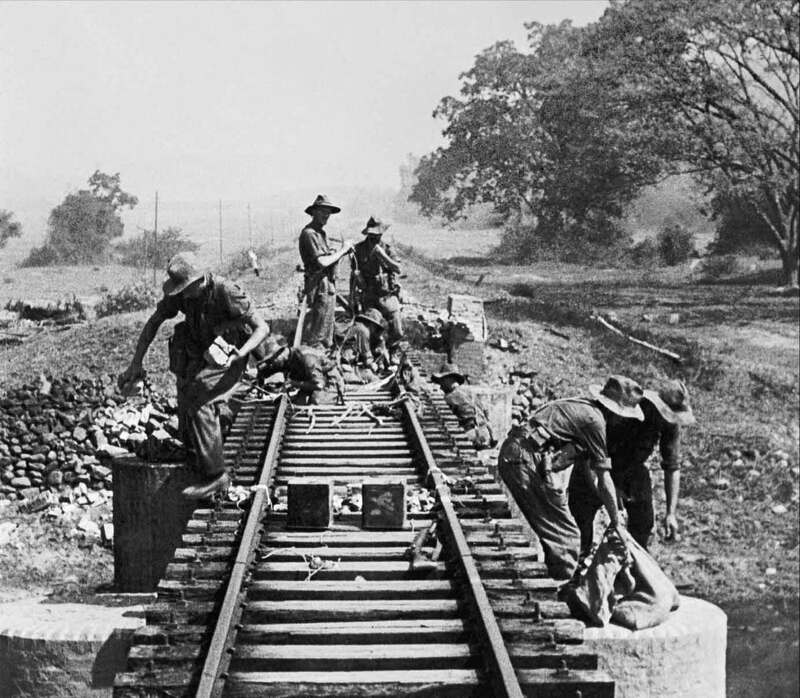

I became more and more anxious to hurry to Bonchaung, and so I told Gerry to come on with men and animals as fast as he could, while I pushed on ahead with Peter Dorans. We got there just after five o'clock, to find everybody in position. David Whitehead, Corporal Pike, and various other sappers were sitting on the bridge with their legs swinging, working away like civvies.

I found Duncan Menzies, who told me that Jim Harman had had a bad time in the jungle, and had turned up at Bonchaung half an hour before, having got hopelessly bushed: he had now set off down the railway line towards the gorge. David hoped to have the bridge ready for blowing at half-past eight or nine; he had already laid a "hasty" demolition, which we could blow if interrupted. Until he was ready there was nothing whatever to be done, bar have a cup of tea. I had several.

Duncan had everybody ready to move at nine, mules loaded and all. David gave us five minutes warning, and told us that the big bang would be preceded by a little bang. The little bang duly went off, and there was a short delay; then ……..

The flash illumined the whole hillside. It showed the men standing tense and waiting, the muleteers with a good grip of their mules; and the brown of the path and the green of the trees preternaturally vivid. Then came the bang. The mules plunged and kicked, the hills for miles around rolled the noise of it about their hollows and flung it to their neighbours. Mike Calvert and John Fraser heard it away in their distant bivouacs; and all of us hoped that John Kerr and his little group of abandoned men, whose sacrifice had helped to make it possible, heard it also, and knew that we had accomplished that which we had come so far to do.

Four miles farther on we met Alec MacDonald's guides; and just as we were going into bivouac we heard another great explosion, and knew that Jim Harman had blown the gorge.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this part of the story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

His skills, experience and credentials were clearly suited to Wingate's newly formed Brigade and Harman volunteered for the operation after seeing an advert for commandos on a noticeboard at the Secunderabad cantonment. He commenced his Chindit training with 142 Commando at their Saugor camp in the Central Provinces of India. He was then allocated to lead the Commando Platoon for No. 5 Column in late December 1942, joining Major Fergusson and his team at Jhansi in time for the Christmas celebrations.

No. 5 Column were given one specific task by Orde Wingate in 1943, this was to destroy the railway bridge and tracks at the village of Bonchaung. Jim Harman's role was to blow the gorge a few miles from the village assisted by Sgt. Pester of the Royal Engineers. Unfortunately, Bernard Fergusson's column were ambushed by the enemy just a few miles north of Bonchaung on the 6th March 1943.

To help set the scene, here is how Bernard Fergusson remembered that day:

On the morning of the 6th of March, everybody got off to time; but before I had marched four hundred yards along the road, Fitzpatrick, Tommy Roberts's groom, came up at a gallop, somewhat flustered. He had been up and down the road for fifteen minutes, unable to spot the point in the jungle where our bivouac had been. (I never bivouacked within five hundred yards of a track).

Tommy was engaged in Kyaik-in village with some Japanese; he had sent Jim Harman back and round to go straight for the gorge, and was fighting it out himself. I asked Fitzpatrick (in civil life a buttons in a Liverpool hotel) for details, but all he knew was that there was a lot of shooting going on, and a lot of bangs, and Tommy had sent him back to warn me. I hastily decided to send the main body straight off across country to Bonchaung. I sent the remaining rifle platoon, now commanded by Gerry Roberts, down the motor-road to the village as fast as it could go, to back up Tommy, while I gave Alec and Duncan their orders. When I had finished, I took Peter Dorans, and followed Gerry.

As I drew near the village, I could hear light machine-guns in action, and the occasional burst of a grenade. The jungle was continuous on the right of the road, but there was a small strip of disused paddy, with some scrubby bushes, on the left; and by the time I arrived (for it took a minute or two to give out the orders to the main body) Gerry's leading Bren section was already in position, and had fired on a small party of Japs. Obsessed with the importance of avoiding a fight with our own troops, I begged him to be careful, and to work gradually along the track. I saw two men of the original party in the bushes on the right, one of whom was Bill Edge's servant, who had been with Tommy: he told me that Bill Edge had been hit, had gone off with Bill Aird to get his wound dressed, and told him to stay by his pack.

By this time all was quiet, except for one light machine-gun firing at us from the south-eastern end of the paddy; but its fire soon ceased, and somebody found the gunner dead by his gun half an hour later. I pushed gingerly forward with a section, and found a fork in the road; one branch, which seemed to be the main road, ran over the hill, and the other went into the village. In the point of the wood at the fork, I saw Private Fairhurst, who called to me that John Kerr was there, wounded. I crossed the road, noticing as I did so two dead Japs, and found John with a painful wound in the calf of the leg, right in the muscle. Beside him were half a dozen Japanese dead and two or three other British dead or wounded: among them was poor Lancaster, the boy who had been one of my swimming instructors, unconscious and almost out.

I offered John some morphia, but he refused it until he had told me his story, in case his brain got muddled, very typical of his devotion to duty. They had walked head-on into a lorry-load of Japs standing in the village: he thought they had just climbed into it after cross-examining the villagers. They had killed several of them at once, but the driver had driven off immediately, with at least two bodies in the back, to the south. They thought they had killed everybody, for the loss of two killed and Bill Edge and one or two others wounded; and Tommy Roberts had gone on. John was waiting only to collect his platoon, when suddenly a new light machine-gun had opened up, and hit him and several more.

While he was telling me this, there was a sudden report just beside my ear, and I spun round to find Peter Doran with a smoking rifle, and one of the two "dead" Japs in the road writhing. He had suddenly flung himself up on his elbow and pointed his rifle at me. Peter shot him again and finally dispatched him.

Bernard Fergusson continues:

What to do with the wounded ? The problem we had all so long dreaded had at last arisen. There were five of them unfit to move, and by bad luck they included not only John but his platoon serjeant and two of his section commanders: they had all been together at the fatal moment. The truck had got away, and there was no knowing when the Japs would come back on us.

We hoisted three of them on to mules, and bore them down to the village a hundred yards away; and there we left them with their packs, and earthen jugs of water, in the shade under one of the houses. One of them said, "Thank God, no more walking for a bit"; one, Corporal Dale, said, "See and make a good job of that bridge;" and John Kerr said, "Don't you worry about us, sir, we'll be all right." The other two were too sick to move, and we had to be content with telling John Kerr where we had left them.

Sixteen dead Japanese were counted in and around the village. It was thought that the one who got away in the lorry was the only survivor. One Gurkha Naik, by the name of Jhuriman Rai, one of six whom I had sent with Tommy as a change from muleteering, killed no less than five of them, three with his rifle and two with his kukri. Five bullet-holes were found in his clothing and equipment afterwards. With Gerry Roberts's platoon, and with the much saddened platoon of John Kerr, I sought the track to Bonchaung, but could find no trace of it. To the south we heard various explosions; we knew it could not be Jim Harman already, and rightly guessed it was Mike Calvert celebrating his thirtieth birthday on the railway.

I became more and more anxious to hurry to Bonchaung, and so I told Gerry to come on with men and animals as fast as he could, while I pushed on ahead with Peter Dorans. We got there just after five o'clock, to find everybody in position. David Whitehead, Corporal Pike, and various other sappers were sitting on the bridge with their legs swinging, working away like civvies.

I found Duncan Menzies, who told me that Jim Harman had had a bad time in the jungle, and had turned up at Bonchaung half an hour before, having got hopelessly bushed: he had now set off down the railway line towards the gorge. David hoped to have the bridge ready for blowing at half-past eight or nine; he had already laid a "hasty" demolition, which we could blow if interrupted. Until he was ready there was nothing whatever to be done, bar have a cup of tea. I had several.

Duncan had everybody ready to move at nine, mules loaded and all. David gave us five minutes warning, and told us that the big bang would be preceded by a little bang. The little bang duly went off, and there was a short delay; then ……..

The flash illumined the whole hillside. It showed the men standing tense and waiting, the muleteers with a good grip of their mules; and the brown of the path and the green of the trees preternaturally vivid. Then came the bang. The mules plunged and kicked, the hills for miles around rolled the noise of it about their hollows and flung it to their neighbours. Mike Calvert and John Fraser heard it away in their distant bivouacs; and all of us hoped that John Kerr and his little group of abandoned men, whose sacrifice had helped to make it possible, heard it also, and knew that we had accomplished that which we had come so far to do.

Four miles farther on we met Alec MacDonald's guides; and just as we were going into bivouac we heard another great explosion, and knew that Jim Harman had blown the gorge.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this part of the story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Immediately after the demolition work at Bonchaung had been concluded, the various sections of 5 Column moved away to the southeast. Jim Harman and his commando section became separated from the main body of the column for several days and did not catch up with Major Fergusson until the 10th March. The following day the Chindits reached the outskirts of Tigyaing village on the Irrawaddy and began their preparations to cross the river at this point. Harman and his men in conjunction with Lt. Stibbe and his platoon and Lt. John Fraser of the Burma Rifles, threw a protective cordon around the village in readiness against any Japanese attack.

Over the next few hours, Fergusson's men re-stocked their food supplies from the helpful and willing villagers and secured enough boats to get the 350 Chindits across the mile-wide river. Lt. Harman and his platoon were first across to secure the east bank and form a bridgehead, into which the rest of the column safely passed having negotiated the river without interference from the enemy.

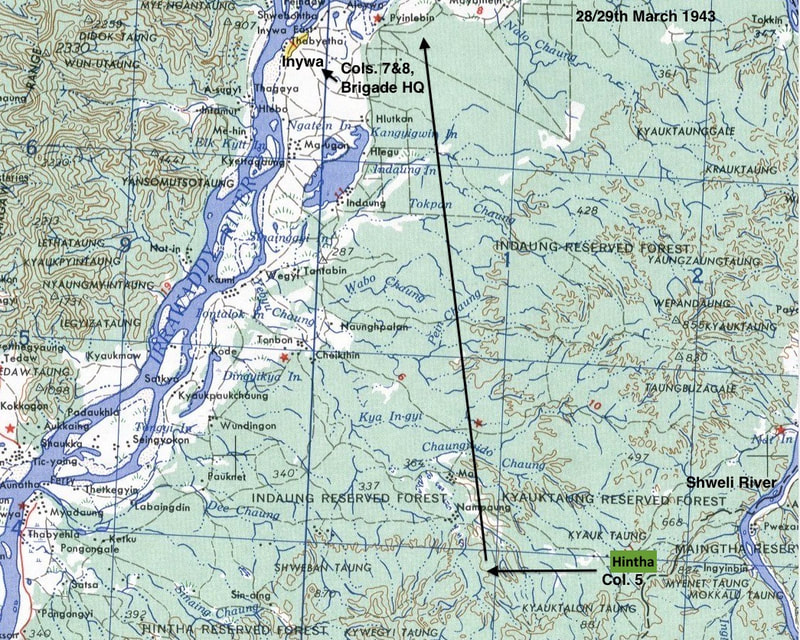

After two weeks of marching and counter-marching to little effect, 5 Column were given orders to create a diversion for the rest of the Chindit Brigade, which was now trapped in a three-sided bag between the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers to the west and north and the Mongmit-Myitson motor road to the south. Brigadier Wingate had instructed Fergusson to "trail his coat" and lead any Japanese pursuers away from the general direction of the Irrawaddy and in particular the area around the town of Inywa, where Wingate and the rest of his columns had hoped to re-cross.

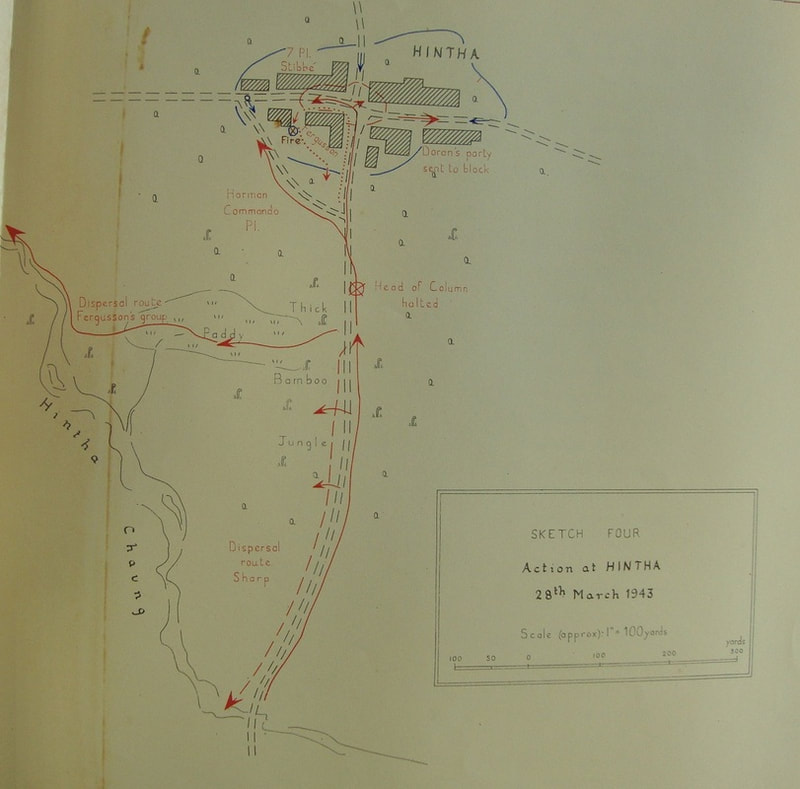

By March 28th, No. 5 Column had reached the village of Hintha which was situated in an area of thick and tight-set bamboo scrub. Any attempt to navigate around the settlement proved impossible, reluctantly, Fergusson decided to enter the village by the main track and check for the presence of any enemy patrols. He unluckily stumbled upon such a patrol and a fire-fight ensued.

Fighting platoons led by Lieutenant Stibbe and Jim Harman entered the village in an attempt to clear the road of Japanese. These were met in full force by the enemy and several casualties were taken on both sides. Stibbe, himself now wounded, returned to the base position of the column and reported to the Major that the situation was getting very hot and that the enemy were making any forward movement by his platoon extremely difficult.

From his own book, Return via Rangoon, Lieutenant Philip Stibbe remembered the 28th March 1943:

We did not have to wait many seconds before machine-gun fire started from somewhere down the left fork of the T junction; the Major told me to take my platoon in with the bayonet. My platoon were in threes behind me, facing down the the track in the direction of the firing. It was impossible to see much in the dark, but there was no time to waste, so I shouted "Bayonets" and told Corporal Litherland and the left-hand section to deal with anything on the left of the track and Corporal Handley and Corporal Berry with the right-hand section to deal with anything on the right. Corporal Dunn was in the centre immediately behind me with his section and I the told him to follow me and deal with anything immediately in front. All this took only a moment; the Major shouted "Good luck", I gave the word and we doubled forward.

It is difficult to realise what is happening in the heat of battle and even more difficult to give a coherent account of it the afterwards, but I remember seeing something move under a house on our left as we went forward and firing at it with my revolver. Then machine-gun fire seemed to come from several directions in front of us and I hurled a grenade at the nearest gun and we got down while it went off. I was standing up to go forward again when something knocked me down and I felt a pain in my left shoulder-blade. The platoon rushed on past me. What was happening in the darkness ahead I could not tell but there was a confused medley of shots, screams, shouts and explosions.

Stibbe was seriously wounded at Hintha, so much so, that within a few short hours he realised he could not continue to march and had to be left by the column in the scrub jungle close to the village. He later became a prisoner of war, surviving almost two years in Rangoon Jail before he was liberated in late April 1945. He recalled:

The firing continued intermittently and the Major sent Jim Harman and the Commando Platoon to try to attack the Japs down the little track we had seen leading off to the left. Alec Macdonald went with them. While this was being done, the Major came over to speak to Corporal Litherland and me but he had hardly begun when a Jap grenade landed beside us.

The Major only just had time to throw himself on the ground before it went off; he was on his feet again in a moment and I did not know till long afterwards that he had been hit in the hip by a fragment. Corporal Litherland was wounded in the head and arm but not as badly as a nearby private soldier who had a terrible head wound and started begging me to shoot him to put him out of his agony.

Fortunately Doc Aird came up with some morphia. By some miracle, although the grenade had landed scarcely an arm's length from me, I was untouched. By this time I was so covered in blood that the Major was convinced I had been hit again. Meanwhile the Commandos had put in their attack down the little track and we were all stunned when the word came back that Alec Macdonald, who had led them in, had been killed with Private Fuller. Jim Harman, who was with him, had been hit in the head and arm but he and Sergeant Pester went on with their men and cleared the track.

The firing now flared up again in our direction, but my platoon, who had remained calm and steady throughout, only fired when they saw a definite target. It was during the burst of firing that Doc Aird came up with one of his orderlies and dressed my wound. Shots were whistling just over their heads and I offered to move under cover while they did it, but they carried on where they were as calmly as if they had been in a hospital ward.

The bullet had gone in through my chest just below my left collar bone, leaving only a very small hole which I had not noticed; the hole at the back where it came out was considerably larger and it was from this that I was losing all the blood.

We were safe at the T junction as long as it was dark, but it would have been an exposed position by daylight and dawn was breaking. We did not know how many Japs we had killed but it was obvious that their casualties had been far heavier than ours. I was not able to check up on my platoon's casualties but I discovered afterwards that we had lost Corporal Handley, Corporal Berry, Lance-Corporal Dunn and Private Cobb, while Corporal Litherland and one or two others had been wounded. The news then came that a way had been found through the jungle at the side of the track, so the Major ordered Brookes to blow the second dispersal call on his bugle. This was the signal for the column to split up into groups which were then to make for the pre-arranged rendezvous.

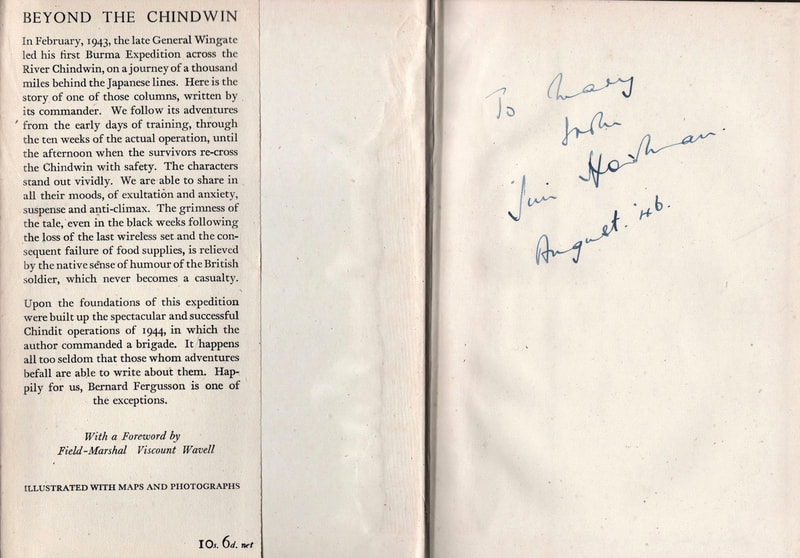

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this part of the story, including two maps of the area around Hintha village. Also shown is a copy of Beyond the Chindwin signed by Jim Harman in 1946, as a present to someone named Mary. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Over the next few hours, Fergusson's men re-stocked their food supplies from the helpful and willing villagers and secured enough boats to get the 350 Chindits across the mile-wide river. Lt. Harman and his platoon were first across to secure the east bank and form a bridgehead, into which the rest of the column safely passed having negotiated the river without interference from the enemy.

After two weeks of marching and counter-marching to little effect, 5 Column were given orders to create a diversion for the rest of the Chindit Brigade, which was now trapped in a three-sided bag between the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers to the west and north and the Mongmit-Myitson motor road to the south. Brigadier Wingate had instructed Fergusson to "trail his coat" and lead any Japanese pursuers away from the general direction of the Irrawaddy and in particular the area around the town of Inywa, where Wingate and the rest of his columns had hoped to re-cross.

By March 28th, No. 5 Column had reached the village of Hintha which was situated in an area of thick and tight-set bamboo scrub. Any attempt to navigate around the settlement proved impossible, reluctantly, Fergusson decided to enter the village by the main track and check for the presence of any enemy patrols. He unluckily stumbled upon such a patrol and a fire-fight ensued.

Fighting platoons led by Lieutenant Stibbe and Jim Harman entered the village in an attempt to clear the road of Japanese. These were met in full force by the enemy and several casualties were taken on both sides. Stibbe, himself now wounded, returned to the base position of the column and reported to the Major that the situation was getting very hot and that the enemy were making any forward movement by his platoon extremely difficult.

From his own book, Return via Rangoon, Lieutenant Philip Stibbe remembered the 28th March 1943:

We did not have to wait many seconds before machine-gun fire started from somewhere down the left fork of the T junction; the Major told me to take my platoon in with the bayonet. My platoon were in threes behind me, facing down the the track in the direction of the firing. It was impossible to see much in the dark, but there was no time to waste, so I shouted "Bayonets" and told Corporal Litherland and the left-hand section to deal with anything on the left of the track and Corporal Handley and Corporal Berry with the right-hand section to deal with anything on the right. Corporal Dunn was in the centre immediately behind me with his section and I the told him to follow me and deal with anything immediately in front. All this took only a moment; the Major shouted "Good luck", I gave the word and we doubled forward.

It is difficult to realise what is happening in the heat of battle and even more difficult to give a coherent account of it the afterwards, but I remember seeing something move under a house on our left as we went forward and firing at it with my revolver. Then machine-gun fire seemed to come from several directions in front of us and I hurled a grenade at the nearest gun and we got down while it went off. I was standing up to go forward again when something knocked me down and I felt a pain in my left shoulder-blade. The platoon rushed on past me. What was happening in the darkness ahead I could not tell but there was a confused medley of shots, screams, shouts and explosions.

Stibbe was seriously wounded at Hintha, so much so, that within a few short hours he realised he could not continue to march and had to be left by the column in the scrub jungle close to the village. He later became a prisoner of war, surviving almost two years in Rangoon Jail before he was liberated in late April 1945. He recalled:

The firing continued intermittently and the Major sent Jim Harman and the Commando Platoon to try to attack the Japs down the little track we had seen leading off to the left. Alec Macdonald went with them. While this was being done, the Major came over to speak to Corporal Litherland and me but he had hardly begun when a Jap grenade landed beside us.

The Major only just had time to throw himself on the ground before it went off; he was on his feet again in a moment and I did not know till long afterwards that he had been hit in the hip by a fragment. Corporal Litherland was wounded in the head and arm but not as badly as a nearby private soldier who had a terrible head wound and started begging me to shoot him to put him out of his agony.

Fortunately Doc Aird came up with some morphia. By some miracle, although the grenade had landed scarcely an arm's length from me, I was untouched. By this time I was so covered in blood that the Major was convinced I had been hit again. Meanwhile the Commandos had put in their attack down the little track and we were all stunned when the word came back that Alec Macdonald, who had led them in, had been killed with Private Fuller. Jim Harman, who was with him, had been hit in the head and arm but he and Sergeant Pester went on with their men and cleared the track.

The firing now flared up again in our direction, but my platoon, who had remained calm and steady throughout, only fired when they saw a definite target. It was during the burst of firing that Doc Aird came up with one of his orderlies and dressed my wound. Shots were whistling just over their heads and I offered to move under cover while they did it, but they carried on where they were as calmly as if they had been in a hospital ward.

The bullet had gone in through my chest just below my left collar bone, leaving only a very small hole which I had not noticed; the hole at the back where it came out was considerably larger and it was from this that I was losing all the blood.

We were safe at the T junction as long as it was dark, but it would have been an exposed position by daylight and dawn was breaking. We did not know how many Japs we had killed but it was obvious that their casualties had been far heavier than ours. I was not able to check up on my platoon's casualties but I discovered afterwards that we had lost Corporal Handley, Corporal Berry, Lance-Corporal Dunn and Private Cobb, while Corporal Litherland and one or two others had been wounded. The news then came that a way had been found through the jungle at the side of the track, so the Major ordered Brookes to blow the second dispersal call on his bugle. This was the signal for the column to split up into groups which were then to make for the pre-arranged rendezvous.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this part of the story, including two maps of the area around Hintha village. Also shown is a copy of Beyond the Chindwin signed by Jim Harman in 1946, as a present to someone named Mary. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

No. 5 Column suffered a second ambush by the Japanese about two miles outside of Hintha. Over 100 Chindits became separated from the main body of the column on the night of the 29th March 1943. Jim Harman, Sgt. Pester and their group were lost for a time, but eventually made the rendezvous in the company of Flight-Lieutenant Denny Sharp of the RAF Liaison section. On the 8th April, Major Fergusson decided to split his column up into three dispersal groups: one commanded by himself, one by flight Lieutenant Denny Sharp and the last, by Captain Tommy Roberts.

Lt. Harman was chosen to form part of Major Fergusson's party, and as previously described, had been wounded in the head and arm during the action against the Japanese at Hintha. He was now being tended and comforted on a continuous basis by Corporal Pike, one of his commandos from the Royal Engineers. The corporal was concerned about Harman and feared that he would not make the journey back to the Chindwin in his current exhausted state.

From the pages of Beyond the Chindwin, by Bernard Fergusson:

About a mile outside of Seiktha, we all sat down in a wooded area and cooked our rice. Corporal Pike, a broad-shouldered and thickset Devonian, asked me how long I thought it would take to reach the Chindwin. Pike had made himself responsible for the well-being of Jim Harman, and looked after him day and night. Jim was making no complaint, but he was looking even more drawn than most and was obviously suffering a good deal. Pike cooked for him, carried most of the contents of his pack and eased him along in a jolly Devonshire fashion like an indulgent Nanny. Even so, Pike still managed to perform his own duties as a NCO, and woe betide any shirker from the commando platoon, if the rough eye of Corporal Pike should fall upon him.

At one stage on the march back to the Chindwin, Major Fergusson feared that he might have to leave Lt. Harman behind. On the 16th April, the dispersal party had reached the Burmese village of Pinmadi and negotiations were underway with the Headman to see if he would take on Fergusson's wounded and infirm. In the end it was decided to keep the group together and fortunately the four or five worrying cases began to steadily regain their strength. On the 24th April, Major Fergusson and his dispersal party re-crossed the Chindwin River close to the village of Sahpe; he and all his men were quickly moved up to the 19th Casualty Clearing Station at Imphal, where they were all hospitalised under the watchful eye of Matron Agnes McGearey.

Lt. Harman was chosen to form part of Major Fergusson's party, and as previously described, had been wounded in the head and arm during the action against the Japanese at Hintha. He was now being tended and comforted on a continuous basis by Corporal Pike, one of his commandos from the Royal Engineers. The corporal was concerned about Harman and feared that he would not make the journey back to the Chindwin in his current exhausted state.

From the pages of Beyond the Chindwin, by Bernard Fergusson:

About a mile outside of Seiktha, we all sat down in a wooded area and cooked our rice. Corporal Pike, a broad-shouldered and thickset Devonian, asked me how long I thought it would take to reach the Chindwin. Pike had made himself responsible for the well-being of Jim Harman, and looked after him day and night. Jim was making no complaint, but he was looking even more drawn than most and was obviously suffering a good deal. Pike cooked for him, carried most of the contents of his pack and eased him along in a jolly Devonshire fashion like an indulgent Nanny. Even so, Pike still managed to perform his own duties as a NCO, and woe betide any shirker from the commando platoon, if the rough eye of Corporal Pike should fall upon him.

At one stage on the march back to the Chindwin, Major Fergusson feared that he might have to leave Lt. Harman behind. On the 16th April, the dispersal party had reached the Burmese village of Pinmadi and negotiations were underway with the Headman to see if he would take on Fergusson's wounded and infirm. In the end it was decided to keep the group together and fortunately the four or five worrying cases began to steadily regain their strength. On the 24th April, Major Fergusson and his dispersal party re-crossed the Chindwin River close to the village of Sahpe; he and all his men were quickly moved up to the 19th Casualty Clearing Station at Imphal, where they were all hospitalised under the watchful eye of Matron Agnes McGearey.

Most returning Chindits remained in hospital for two or three weeks after Operation Longcloth closed, before enjoying another lengthy spell of rest and recuperation in the northern hill stations of India. Jim Harman then returned to Chindit training in preparation for the second Wingate expedition, Operation Thursday, which began in February 1944. Bernard Fergusson, now promoted to Brigadier led one of the six Chindit Brigades in 1944. His 16th British Infantry Brigade was the only Chindit unit to march into Burma that year, beginning their journey on the 5th February at a place called Namyung Hka on the Ledo Road.

Fergusson did not call on Jim Harman to march with his Brigade at the outset of Operation Thursday, preferring instead to use Harman's commando platoon as an attack force, flown into action ahead of the main columns to deal with small pockets of the enemy causing nuisance to the Chindit Brigades. On one such occasion, Harman alongside a platoon from the 2nd Black Watch and Lt. Peter Bennett (another veteran from the year before), landed in gliders close to the village of Hkamti, where they ruthlessly removed a Japanese garrison who had been stationed at the village for several weeks.

From Fergusson's book, Wild Green Earth:

Because Jim had had three holes knocked into him the previous year and had walked three hundred and fifty miles to safety despite of them, I was loathed to bring him in again, doubting his ability to stay the course. In the end we compromised on putting him with the light planes and gliders and using him for short excursions only. Jim was also used at my Aberdeen stronghold, where he remained for many days, often keeping my columns in fresh water by driving to and fro in an American supplied jeep and trailer to our activities outside of Indaw. Jim, who was always thirsting for adventure, completed his final task for me, when he landed on a freshly cut landing strip near Indawgyi Lake. I had wanted a diversion on a Jap-frequented road in order to show them our capabilities and ubiquitous nature and he duly obliged when his group took care of an enemy patrol using their tommy guns and grenades.

Seen below is a final gallery of images in relation to this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. It is thought, but not confirmed that Jim Harman was killed in a road traffic accident in Johannesburg, South Africa during the late 1950's.

Fergusson did not call on Jim Harman to march with his Brigade at the outset of Operation Thursday, preferring instead to use Harman's commando platoon as an attack force, flown into action ahead of the main columns to deal with small pockets of the enemy causing nuisance to the Chindit Brigades. On one such occasion, Harman alongside a platoon from the 2nd Black Watch and Lt. Peter Bennett (another veteran from the year before), landed in gliders close to the village of Hkamti, where they ruthlessly removed a Japanese garrison who had been stationed at the village for several weeks.

From Fergusson's book, Wild Green Earth:

Because Jim had had three holes knocked into him the previous year and had walked three hundred and fifty miles to safety despite of them, I was loathed to bring him in again, doubting his ability to stay the course. In the end we compromised on putting him with the light planes and gliders and using him for short excursions only. Jim was also used at my Aberdeen stronghold, where he remained for many days, often keeping my columns in fresh water by driving to and fro in an American supplied jeep and trailer to our activities outside of Indaw. Jim, who was always thirsting for adventure, completed his final task for me, when he landed on a freshly cut landing strip near Indawgyi Lake. I had wanted a diversion on a Jap-frequented road in order to show them our capabilities and ubiquitous nature and he duly obliged when his group took care of an enemy patrol using their tommy guns and grenades.

Seen below is a final gallery of images in relation to this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. It is thought, but not confirmed that Jim Harman was killed in a road traffic accident in Johannesburg, South Africa during the late 1950's.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, February 2019.