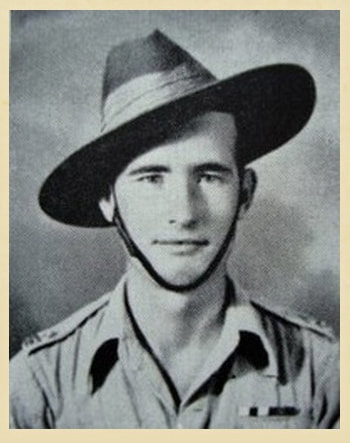

Lieutenant Robin Painter

Robin Painter's book, A Signal Honour.

Robin Painter's book, A Signal Honour.

Robin Peter Douglas Painter was born on the Isle of Wight in 1923. The son of a Naval Officer, he was sent to the mainland for his education, studying at University College School in Hampstead, London. As a young Chindit officer in 1943, Painter does not feature at all in any of the relevant war diaries or books on the first Wingate expedition. In fact the vast majority, if not all of the information relayed below comes directly from his own WW2 memoir, the book, A Signal Honour, which was first published by Leo Cooper in 1999.

Robin was studying and travelling in the South of France when war broke out in 1939. He immediately made his way back to England and served with his school's Officer Training Corps, reaching the rank of Sergeant and also volunteered for the Local Defence Volunteer Force on Hampstead Heath.

The following year, Pte. 3066386 R.P.D. Painter (Royal Scots) was posted to the Officer Cadet Training Centre, located at the Ramillies Barracks in Aldershot. In December 1941, he was chosen to train as an officer cadet for the Indian Army and voyaged from Greenock in Scotland aboard the troopship Stratheden, taking the usual route into the North Atlantic: a supply stop at Freetown, Sierra Leonne, followed by a weeks stop-over at Durban and then on to Bombay, arriving in India on the 3rd February 1942.

He began his service in the Indian Army as infantry officer at the Officer Training School in Bangalore, but soon transferred to the Royal Signals. An outstanding Officer Cadet, 2nd Lieutenant Painter trained at Mhow in Central India during 1942. He was then posted to join Special Force (111 Brigade) at Meerut, but circumstances intervened and in early February 1943, he was sent to Imphal to join 77th Indian Infantry Brigade at the last possible minute before Operation Longcloth.

From the book, A Signal Honour:

In due course I was cross-posted to 77 Brigade, a formation of Long Range Penetration troops which had been training in the Central Provinces. The Brigadier was Orde Wingate and they were about to set off into Burma on his first expedition. I finally caught up with them in mid-February 1943 near Imphal, where they were taking a short rest after marching from the railhead at Dimapur and before setting off again for Tamu and the River Chindwin.

I had been flown in by Dakota to Tulihal airstrip from Calcutta's Dum Dum Airport; a raw 2nd Lieutenant who had missed the specialist training in the Central Provinces and who, in retrospect, was far too young and inexperienced to participate in such a venture. But there I was, 19 years old, fit and overflowing with enthusiasm. I was soon to learn the hard way that what lay ahead was far from being a picnic and I could not help but feel we were putting our heads on the chopping block.

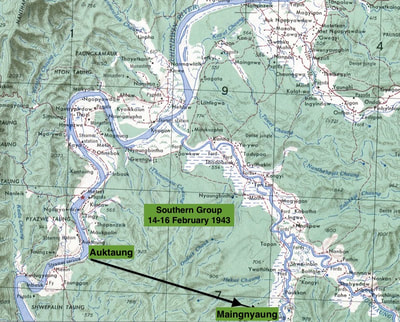

2nd Lieutenant Painter was allocated to Southern Group commanded by Lt-Colonel Alexander of 3/2 Gurkha Rifles and was explained the purpose for this section of Chindits, that being to be the decoy for the other Chindit columns of Northern Group. He remained with Alexander’s HQ (1 Column) assisting with signals, radio communications and other duties. Southern Group crossed the Chindwin at Auktaung on 14/15th February and pushed deep into enemy territory. Marching overtly along well-known jungle tracks and passing through numerous villages en route, the two Gurkha columns took their first supply drop shortly after crossing the river. Here Robin assisted the RAF Liaison officer, F/Lt. John Edmunds in preparing the drop zone and calling in the Hudson supply planes.

Southern Group had their first contact with the Japanese on the 18th February, at the village of Maingnyaung some 20 miles southeast of the Chindwin River. They then continued their march towards the Mu River and ultimately the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway at Kyaikthin. On the 3rd March, No. 1 Column, led by Major George Dunlop successfully blew up the railway bridge north of Kyaikthin and then marched on to the Irrawaddy at Tagaung. Trouble with radio communications meant that No. 1 Column alongside Brigade HQ, had been out of contact with No. 2 Column for several days and were not aware that this unit had been ambushed by the Japanese at the railway embankment close to Kyaikthin village. To read more about the ambush at Kyaikthin, please click on the following link: Lt. MacHorton and the battle of Kyaikthin

On the 8th March, No. 1 Column took another supply drop and at this juncture learned the fate of No. 2 Column when a group of survivors from the recent ambush caught up with them at the Irrawaddy. Once over the river Colonel Alexander and Major Dunlop’s group moved off east into the dense jungle and awaited further orders from Brigadier Wingate.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the first part of this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Robin was studying and travelling in the South of France when war broke out in 1939. He immediately made his way back to England and served with his school's Officer Training Corps, reaching the rank of Sergeant and also volunteered for the Local Defence Volunteer Force on Hampstead Heath.

The following year, Pte. 3066386 R.P.D. Painter (Royal Scots) was posted to the Officer Cadet Training Centre, located at the Ramillies Barracks in Aldershot. In December 1941, he was chosen to train as an officer cadet for the Indian Army and voyaged from Greenock in Scotland aboard the troopship Stratheden, taking the usual route into the North Atlantic: a supply stop at Freetown, Sierra Leonne, followed by a weeks stop-over at Durban and then on to Bombay, arriving in India on the 3rd February 1942.

He began his service in the Indian Army as infantry officer at the Officer Training School in Bangalore, but soon transferred to the Royal Signals. An outstanding Officer Cadet, 2nd Lieutenant Painter trained at Mhow in Central India during 1942. He was then posted to join Special Force (111 Brigade) at Meerut, but circumstances intervened and in early February 1943, he was sent to Imphal to join 77th Indian Infantry Brigade at the last possible minute before Operation Longcloth.

From the book, A Signal Honour:

In due course I was cross-posted to 77 Brigade, a formation of Long Range Penetration troops which had been training in the Central Provinces. The Brigadier was Orde Wingate and they were about to set off into Burma on his first expedition. I finally caught up with them in mid-February 1943 near Imphal, where they were taking a short rest after marching from the railhead at Dimapur and before setting off again for Tamu and the River Chindwin.

I had been flown in by Dakota to Tulihal airstrip from Calcutta's Dum Dum Airport; a raw 2nd Lieutenant who had missed the specialist training in the Central Provinces and who, in retrospect, was far too young and inexperienced to participate in such a venture. But there I was, 19 years old, fit and overflowing with enthusiasm. I was soon to learn the hard way that what lay ahead was far from being a picnic and I could not help but feel we were putting our heads on the chopping block.

2nd Lieutenant Painter was allocated to Southern Group commanded by Lt-Colonel Alexander of 3/2 Gurkha Rifles and was explained the purpose for this section of Chindits, that being to be the decoy for the other Chindit columns of Northern Group. He remained with Alexander’s HQ (1 Column) assisting with signals, radio communications and other duties. Southern Group crossed the Chindwin at Auktaung on 14/15th February and pushed deep into enemy territory. Marching overtly along well-known jungle tracks and passing through numerous villages en route, the two Gurkha columns took their first supply drop shortly after crossing the river. Here Robin assisted the RAF Liaison officer, F/Lt. John Edmunds in preparing the drop zone and calling in the Hudson supply planes.

Southern Group had their first contact with the Japanese on the 18th February, at the village of Maingnyaung some 20 miles southeast of the Chindwin River. They then continued their march towards the Mu River and ultimately the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway at Kyaikthin. On the 3rd March, No. 1 Column, led by Major George Dunlop successfully blew up the railway bridge north of Kyaikthin and then marched on to the Irrawaddy at Tagaung. Trouble with radio communications meant that No. 1 Column alongside Brigade HQ, had been out of contact with No. 2 Column for several days and were not aware that this unit had been ambushed by the Japanese at the railway embankment close to Kyaikthin village. To read more about the ambush at Kyaikthin, please click on the following link: Lt. MacHorton and the battle of Kyaikthin

On the 8th March, No. 1 Column took another supply drop and at this juncture learned the fate of No. 2 Column when a group of survivors from the recent ambush caught up with them at the Irrawaddy. Once over the river Colonel Alexander and Major Dunlop’s group moved off east into the dense jungle and awaited further orders from Brigadier Wingate.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the first part of this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

As with all the remaining Chindit columns, by the second week of March, No. 1 Column found themselves contained within the Irrawaddy/Shweli triangle and for a time went short of both water and supplies. The next supply drop was on the 14th March near the village of Hmaingdaing and shortly after this the column was given orders to move south-east towards Mogok and liaise with columns 3 & 5 as they themselves marched for the Gokteik Viaduct. On the 23rd March, Painter's column bumped No. 5 Column and were informed that Major Fergusson was no longer involved with the attack on the viaduct.

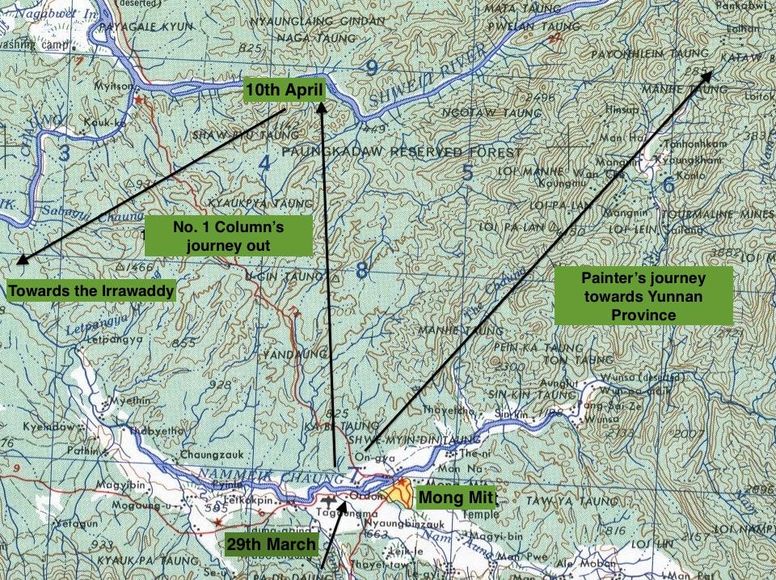

By now the enemy were closing in on the Chindit Brigade and No. 1 Column were ambushed by a Japanese patrol on 25th March, but thankfully few casualties were inflicted. On the 27th March, Alexander was informed that the attack on Gokteik had been cancelled and the order was given to return to India.

No. 1 Column were now the furthest Chindit unit from the relative safety of the Chindwin River. A supply drop was arranged for the 30th March and discussions were had between Alexander and Major Dunlop regarding which direction to exit Burma; west to the Irrawaddy and back the way they came or east into the Yunnan Province of China. Lt. Painter was sent out with a twelve man patrol to monitor the Mogok-Mong Mit Road and to advise on enemy numbers and movements. On his return he discovers that the column have moved away from the previous bivouac area after reports of a strong Japanese force in the vicinity.

Now alone and without radio contact, Painter and his men, including Havildar Aung Hla of the Burma Rifles and ten other Burma Riflemen and Gurkhas decide to make for the Chinese borders. Two of the Burma Riflemen were from fairly local Kachin tribes and their connections in the vicinity were vital in the group eventually exiting Burma via Yunnan Province.

From the book, A Signal Honour:

I had with me a Burrif Havildar (Sergeant) with whom I had worked on a number of previous patrols. His name was Aung Hla and in these circumstances I could not have asked for a better senior NCO. He was a Karen, considerably older than me at about 33 years old and a very experienced soldier who had come out of Burma during the retreat in 1942. He spoke good English and was completely loyal and supportive. I made the decision to head for the Yunnan Province of China after much discussion with Aung Hla. We considered all the possible options only after a very careful listing of our limited assets and supplies. The first thing I checked was the ration state. We were all in weak physical shape, but hopefully could still march through this difficult terrain.

The small party of Gurkhas with their Burrif guides moved into the Kodaung Hill Tracts, here they were helped by friendly Kachin villagers, offering food, information about the Japanese and supplying local guides to lead the Chindits on to the next village. Lieutenant Painter's health began to falter and apart from him weakening through hunger, he also suffered from bouts of malaria and dysentery. It was from this moment on, that Havildar Aung Hla effectively took command of the dispersal party and it was through his skill and good judgement over the next three weeks or so that the group finally reached the Chinese town of Paoshan and the safety of Allied held lines. From Paoshan, the Chindits were taken to a USAAF base and enjoyed the luxury of being flown back to India aboard Dakota aircraft.

On arrival at Dibrugarh in Assam, Robin Painter and his men became separated, with the Gurkhas and Burma Riflemen being sent on to a Field Hospital at Imphal. Lieutenant Painter remembered:

Sadly, I parted company with my companions, who had been loyal and devoted comrades in times of adversity. I tried to trace them later on, but without success. I also did my utmost to ensure Havildar Aung Hla received some form of recognition for all he had done, but I heard nothing more and fear my recommendation fell on deaf ears. One thing is for sure, without him, I doubt that we would have made it.

By now the enemy were closing in on the Chindit Brigade and No. 1 Column were ambushed by a Japanese patrol on 25th March, but thankfully few casualties were inflicted. On the 27th March, Alexander was informed that the attack on Gokteik had been cancelled and the order was given to return to India.

No. 1 Column were now the furthest Chindit unit from the relative safety of the Chindwin River. A supply drop was arranged for the 30th March and discussions were had between Alexander and Major Dunlop regarding which direction to exit Burma; west to the Irrawaddy and back the way they came or east into the Yunnan Province of China. Lt. Painter was sent out with a twelve man patrol to monitor the Mogok-Mong Mit Road and to advise on enemy numbers and movements. On his return he discovers that the column have moved away from the previous bivouac area after reports of a strong Japanese force in the vicinity.

Now alone and without radio contact, Painter and his men, including Havildar Aung Hla of the Burma Rifles and ten other Burma Riflemen and Gurkhas decide to make for the Chinese borders. Two of the Burma Riflemen were from fairly local Kachin tribes and their connections in the vicinity were vital in the group eventually exiting Burma via Yunnan Province.

From the book, A Signal Honour:

I had with me a Burrif Havildar (Sergeant) with whom I had worked on a number of previous patrols. His name was Aung Hla and in these circumstances I could not have asked for a better senior NCO. He was a Karen, considerably older than me at about 33 years old and a very experienced soldier who had come out of Burma during the retreat in 1942. He spoke good English and was completely loyal and supportive. I made the decision to head for the Yunnan Province of China after much discussion with Aung Hla. We considered all the possible options only after a very careful listing of our limited assets and supplies. The first thing I checked was the ration state. We were all in weak physical shape, but hopefully could still march through this difficult terrain.

The small party of Gurkhas with their Burrif guides moved into the Kodaung Hill Tracts, here they were helped by friendly Kachin villagers, offering food, information about the Japanese and supplying local guides to lead the Chindits on to the next village. Lieutenant Painter's health began to falter and apart from him weakening through hunger, he also suffered from bouts of malaria and dysentery. It was from this moment on, that Havildar Aung Hla effectively took command of the dispersal party and it was through his skill and good judgement over the next three weeks or so that the group finally reached the Chinese town of Paoshan and the safety of Allied held lines. From Paoshan, the Chindits were taken to a USAAF base and enjoyed the luxury of being flown back to India aboard Dakota aircraft.

On arrival at Dibrugarh in Assam, Robin Painter and his men became separated, with the Gurkhas and Burma Riflemen being sent on to a Field Hospital at Imphal. Lieutenant Painter remembered:

Sadly, I parted company with my companions, who had been loyal and devoted comrades in times of adversity. I tried to trace them later on, but without success. I also did my utmost to ensure Havildar Aung Hla received some form of recognition for all he had done, but I heard nothing more and fear my recommendation fell on deaf ears. One thing is for sure, without him, I doubt that we would have made it.

Lt. Painter spent six weeks in hospital at Ranchi. He was suffering from amoebic dysentery, jungle sores and jaundice and had lost over three stones in weight. He then took three weeks recuperation leave at Srinagar in Kashmir, before returning to take up his original posting with 111 Brigade's Signal Section who were now training for the second Wingate expedition at Ghatera. After struggling with his fitness during training, Lt. Painter fell ill again, this time suffering from acute appendicitis in July 1943. This health issue was to end his association with the Chindits.

After another period of convalescence in Kashmir, he was posted to the North West Frontier and joined the Waziristan District Signals, taking up the role of 2 I/C to Captain Paddy Roy at the Brigade Signal Section based at the Bannu Fortification. Here he learns the ropes in dealing with the North West Frontier tribesmen and their unpredictable ways and finds the more rigid Army discipline on the frontier very different to his previous experiences with the Chindits.

Robin Painter left the North West Frontier on 5th January 1944 and was posted via Calcutta to Comilla where he became second in command, 80th Brigade Signal Section within the 20th Indian Division. This unit was based at Tamu close to the Chindwin River in the Kabaw Valley. In March 1944 the Japanese advanced against Imphal and Kohima and 20 Division withdrew from Tamu and took up a defensive position at the Shenam Ridge on the Imphal Plain.

From the book, A Signal Honour:

The Shenam Ridge soon began to smell with the sweet, sickly, horrifying aroma of death. We all became filthy and very tired. Sleep could only be intermittent and our beds were the foxholes in the ground where we fought. We were never sure that we could hold our ground but realised that we must do so. This period of my service seemed endless, it was a frightening time, yet an extraordinary spirit developed among the British, Indian and Gurkha soldiers involved. No quarter was asked or given and a dogged determination grew to hold our positions at all costs. Both sides fought themselves to a standstill. Often the Japanese succeeded in breaking through, only to be eliminated by our counter-attacks and we came to believe that unless we ourselves were killed, the fighting would never end.

Thankfully, by July 1944 the 14th Army began to drive the Japanese back from Imphal and Kohima and 80 Brigade were withdrawn from the battle to rest and reform. The newly promoted Captain Painter was transferred to 62nd Brigade Signal Section, 19th Indian Infantry (Daggers) Division. His new Brigadier was none other than James Ronald 'Jumbo' Morris, who had served during the second Chindit expedition as commander of Morris Force. The 19th Indian Division were tasked to cross the Irrawaddy in early 1945 as part of the push towards Mandalay. After being involved in some heavy engagements with the Japanese, 62nd Brigade were eventually ordered to liberate the hill station of Maymyo. After several days march through little known tracks the Brigade reached the outskirts of Maymyo and on the 10th March 1945 in a surprise dawn attack captured the town from the Japanese.

62 Brigade were then ordered to march to Mandalay, which had just been taken by British forces. The tribulations of almost two months continuous marching resulted in the now exhausted Captain Painter falling ill once more. A combination of amoebic dysentery, jaundice and jungle sores, led to his evacuation from the field and hospitalisation at Calcutta. Several months later, whilst on leave at Srinagar he heard the news that the first atomic bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima and that the war with Japan was effectively over. In late 1945, he moved down to the British transitory camp at Deolali and prepared for repatriation to the United Kingdom, returning home aboard the Empress of Scotland in time for Christmas. In May 1946, Robin Painter married Minnie Lea at St. Matthew's Church in Bayswater and continued his service in the British Army, eventually retiring with the rank of Lt-Colonel in 1972.

Seen below is a final gallery of images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

After another period of convalescence in Kashmir, he was posted to the North West Frontier and joined the Waziristan District Signals, taking up the role of 2 I/C to Captain Paddy Roy at the Brigade Signal Section based at the Bannu Fortification. Here he learns the ropes in dealing with the North West Frontier tribesmen and their unpredictable ways and finds the more rigid Army discipline on the frontier very different to his previous experiences with the Chindits.

Robin Painter left the North West Frontier on 5th January 1944 and was posted via Calcutta to Comilla where he became second in command, 80th Brigade Signal Section within the 20th Indian Division. This unit was based at Tamu close to the Chindwin River in the Kabaw Valley. In March 1944 the Japanese advanced against Imphal and Kohima and 20 Division withdrew from Tamu and took up a defensive position at the Shenam Ridge on the Imphal Plain.

From the book, A Signal Honour:

The Shenam Ridge soon began to smell with the sweet, sickly, horrifying aroma of death. We all became filthy and very tired. Sleep could only be intermittent and our beds were the foxholes in the ground where we fought. We were never sure that we could hold our ground but realised that we must do so. This period of my service seemed endless, it was a frightening time, yet an extraordinary spirit developed among the British, Indian and Gurkha soldiers involved. No quarter was asked or given and a dogged determination grew to hold our positions at all costs. Both sides fought themselves to a standstill. Often the Japanese succeeded in breaking through, only to be eliminated by our counter-attacks and we came to believe that unless we ourselves were killed, the fighting would never end.

Thankfully, by July 1944 the 14th Army began to drive the Japanese back from Imphal and Kohima and 80 Brigade were withdrawn from the battle to rest and reform. The newly promoted Captain Painter was transferred to 62nd Brigade Signal Section, 19th Indian Infantry (Daggers) Division. His new Brigadier was none other than James Ronald 'Jumbo' Morris, who had served during the second Chindit expedition as commander of Morris Force. The 19th Indian Division were tasked to cross the Irrawaddy in early 1945 as part of the push towards Mandalay. After being involved in some heavy engagements with the Japanese, 62nd Brigade were eventually ordered to liberate the hill station of Maymyo. After several days march through little known tracks the Brigade reached the outskirts of Maymyo and on the 10th March 1945 in a surprise dawn attack captured the town from the Japanese.

62 Brigade were then ordered to march to Mandalay, which had just been taken by British forces. The tribulations of almost two months continuous marching resulted in the now exhausted Captain Painter falling ill once more. A combination of amoebic dysentery, jaundice and jungle sores, led to his evacuation from the field and hospitalisation at Calcutta. Several months later, whilst on leave at Srinagar he heard the news that the first atomic bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima and that the war with Japan was effectively over. In late 1945, he moved down to the British transitory camp at Deolali and prepared for repatriation to the United Kingdom, returning home aboard the Empress of Scotland in time for Christmas. In May 1946, Robin Painter married Minnie Lea at St. Matthew's Church in Bayswater and continued his service in the British Army, eventually retiring with the rank of Lt-Colonel in 1972.

Seen below is a final gallery of images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, September 2018.