Lieutenant Thomas Arthur Stock

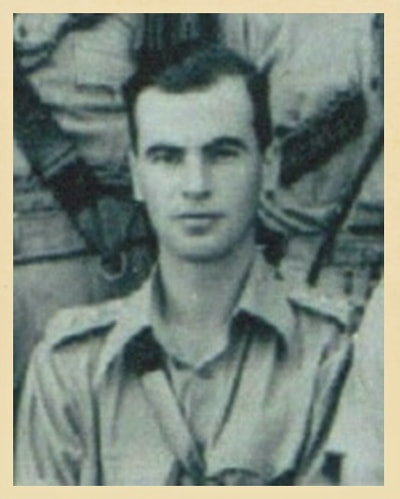

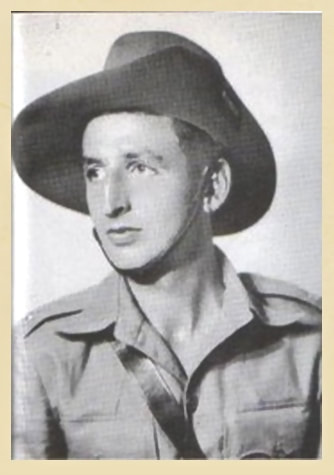

Thomas Arthur Stock at Agra (India) in 1945.

Thomas Arthur Stock at Agra (India) in 1945.

From an email received in September 2014:

My father was Lt.Thomas Arthur Stock. He was such a wonderful, humane, erudite and communicative man, who combined his immense depth of knowledge with a warmth and readiness to share.

He was friends after the war with Philip Stibbe and is mentioned a few times in Stibbe's book, Return via Rangoon. I understand he was in the 19th Hyderabad Regiment when he volunteered for the first Chindit operation. I have just started researching a letter from his tutor (before the war) at Oxford sent to Trimulgherry hospital in May 1945, where the tutor expresses his delight to hear Tom is still alive. The letter is all the more interesting given that the writer is one C.S. Lewis.

I imagine you get a lot of queries regarding your website, but if you have any additional information on my father I would be most grateful to hear from you. He passed away over ten years ago, but lived a happy life continuing, amongst many other interests to read and study the Japanese language until shortly before he died.

Kind regards, Rosamund Stock.

Tom Stock was born in Gloucester on the 3rd December 1921, the only son of a local baker. Sadly, his father died when Tom was still a teenager, leaving his mother, Edith to run the family home. Tom attended the Crypt School in Podsmead Road, Gloucester and proved to be an excellent scholar, confident debater and talented actor in many of the school's drama productions. His achievements at school led to him taking up a scholarship, choosing to study English under the famous novelist, C.S. Lewis at Magdelen College, Oxford.

Daughter Rosamund recalled:

Tom's first year at Oxford was a halcyon period. Oxford suited him admirably, the academic excellence, the wide range of clubs and societies, the courtesy with which students were treated. He would recall the college Head Porter taking pride in his staff only asking a student his name once and thereafter members of the college were all known and remembered. At Oxford the Inklings were a literary group of like-minded friends centred around Tolkien, Charles Williams and Tom’s tutor, C.S. Lewis. As a student, the stimulus of time spent with this select circle of writers was meat and drink to my father.

Unfortunately, the heady days at Oxford would be short-lived as the storm clouds of war began to gather over Europe. Tom joined the Officer's Training Corps at Magdelen College in October 1940 and most of his time was taken up with Army training and fire watching duties, so much so, that he and many of his contemporaries failed their initial exams at University. As with so many young men in 1940, Tom felt it was more important to do his bit and serve his country, than to worry about his education or academic studies. During his early months of training at the OTC, his tutor, C.S. Lewis attempted to persuade Tom that the RAF might be a better option than the Army. However, on the 8th December 1941 at Salisbury, Cadet 6477762 Thomas Arthur Stock (Territorial Army) was interviewed for a place in the Indian Army.

In mid-February 1942, Tom left British shores bound for India and disembarked at Bombay (Gateway to India) on the 8th April. He spent the first few weeks of his time on the sub-continent at the Officer's Training School, Bangalore and settled well into Army life, which included him learning the Indian language of Urdu. He was given the Army number EC-6056 and commissioned into the 19th Hyderabad Regiment in mid-August 1942, with his appointment as 2nd Lieutenant being Gazetted on the 25th December that same year. Within a few weeks of taking up his commission with the 19th Hyderabad's, Tom volunteered for a secret mission and was posted to Jhansi to join the recently formed 77th Indian Infantry Brigade. He and several other young officers from Indian Regiments were allocated to the various Chindit columns just before Christmas, with Tom sent to bolster No. 7 Column under the command of Major Kenneth Gilkes of the King's Regiment.

During Operation Longcloth, Tom served as 7 Column's Intelligence Officer and travelled with Major Gilkes and his Head Quarters. It is said that he crossed the Chindwin riding his horse and wearing only his slouch hat and a belt of grenades. Generally speaking, 7 Column were used as protection for Brigadier Wingate and his own Brigade Head Quarters and only took part in one or two skirmishes with the Japanese in 1943. The Chindits had troubled the Japanese lines of communication in February and March 1943, demolishing various pieces of the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway. In late March, with the enemy now closing in, Wingate called an officers conference and with the added advice of India General Command, decided to call it a day and return back across the Chindwin.

On the 29th March, Brigade HQ, in the company of Columns 7 and 8 arrived at the Irrawaddy River, close to the village of Inywa. Wingate ordered Captain David Hastings to lead a bridgehead party across the river in the small Burmese country boats they had discovered hidden on the eastern shoreline. As the men prepared to cross some enemy activity was seen on the far bank. Wingate and his commanders felt that the Japanese posed little threat in their present numbers, and so pressed on with the crossing. Some of the lead boats did manage to get over, but others came under heavy mortar and machine gun fire and began to get into difficulties.

The crossing at Inywa was duly abandoned, the remaining columns and Wingate's HQ melted back into the jungle on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy. The three units agreed there and then to split up and make their own way back to Allied held territory individually. 7 Column retraced their steps east and set off toward the Chinese Yunnan borders. 8 Column under Major Scott eventually crossed the Irrawaddy further to the north two weeks later with the help of some more native boats, while Wingate held back in the jungles around Inywa for almost a week, hoping that the Japanese activity in the area would die down and their progress to India could resume unmolested.

Meanwhile, on the west bank of the Irrawaddy, opposite the village of Inywa, some thirty Chindit soldiers who had followed Captain Hastings over the river found themselves isolated and alone. One of these now desolate fellows was Lt. Thomas Arthur Stock.

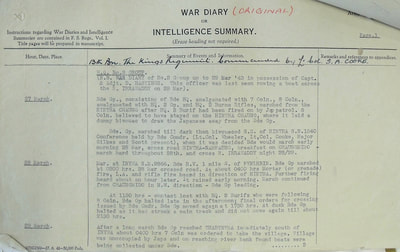

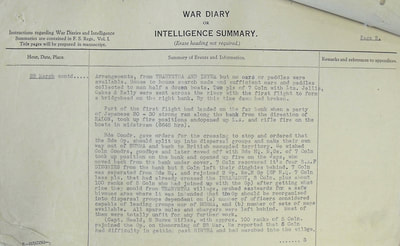

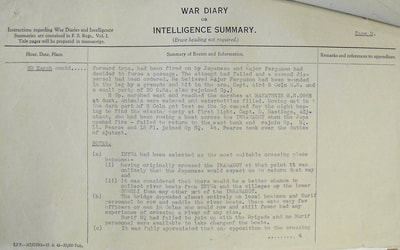

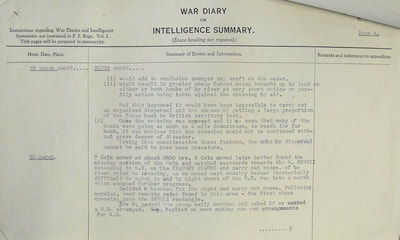

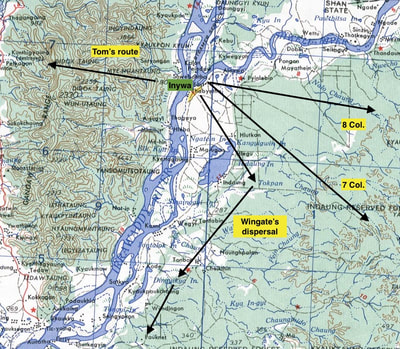

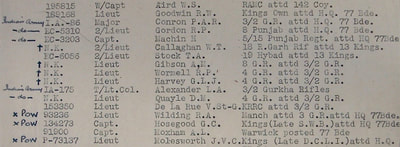

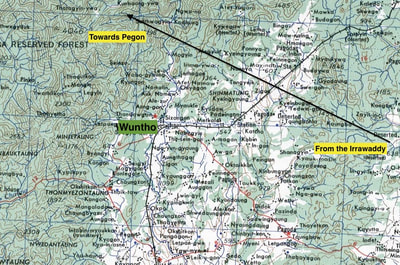

Seen below is a gallery of images, consisting of four pages from the 13th King's War diary for 1943, recording the events leading up to and during the failed crossing of the Irrawaddy River at Inywa on March 29th. Also shown is a map of the area around Inywa and the various column dispersal routes thereafter. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

My father was Lt.Thomas Arthur Stock. He was such a wonderful, humane, erudite and communicative man, who combined his immense depth of knowledge with a warmth and readiness to share.

He was friends after the war with Philip Stibbe and is mentioned a few times in Stibbe's book, Return via Rangoon. I understand he was in the 19th Hyderabad Regiment when he volunteered for the first Chindit operation. I have just started researching a letter from his tutor (before the war) at Oxford sent to Trimulgherry hospital in May 1945, where the tutor expresses his delight to hear Tom is still alive. The letter is all the more interesting given that the writer is one C.S. Lewis.

I imagine you get a lot of queries regarding your website, but if you have any additional information on my father I would be most grateful to hear from you. He passed away over ten years ago, but lived a happy life continuing, amongst many other interests to read and study the Japanese language until shortly before he died.

Kind regards, Rosamund Stock.

Tom Stock was born in Gloucester on the 3rd December 1921, the only son of a local baker. Sadly, his father died when Tom was still a teenager, leaving his mother, Edith to run the family home. Tom attended the Crypt School in Podsmead Road, Gloucester and proved to be an excellent scholar, confident debater and talented actor in many of the school's drama productions. His achievements at school led to him taking up a scholarship, choosing to study English under the famous novelist, C.S. Lewis at Magdelen College, Oxford.

Daughter Rosamund recalled:

Tom's first year at Oxford was a halcyon period. Oxford suited him admirably, the academic excellence, the wide range of clubs and societies, the courtesy with which students were treated. He would recall the college Head Porter taking pride in his staff only asking a student his name once and thereafter members of the college were all known and remembered. At Oxford the Inklings were a literary group of like-minded friends centred around Tolkien, Charles Williams and Tom’s tutor, C.S. Lewis. As a student, the stimulus of time spent with this select circle of writers was meat and drink to my father.

Unfortunately, the heady days at Oxford would be short-lived as the storm clouds of war began to gather over Europe. Tom joined the Officer's Training Corps at Magdelen College in October 1940 and most of his time was taken up with Army training and fire watching duties, so much so, that he and many of his contemporaries failed their initial exams at University. As with so many young men in 1940, Tom felt it was more important to do his bit and serve his country, than to worry about his education or academic studies. During his early months of training at the OTC, his tutor, C.S. Lewis attempted to persuade Tom that the RAF might be a better option than the Army. However, on the 8th December 1941 at Salisbury, Cadet 6477762 Thomas Arthur Stock (Territorial Army) was interviewed for a place in the Indian Army.

In mid-February 1942, Tom left British shores bound for India and disembarked at Bombay (Gateway to India) on the 8th April. He spent the first few weeks of his time on the sub-continent at the Officer's Training School, Bangalore and settled well into Army life, which included him learning the Indian language of Urdu. He was given the Army number EC-6056 and commissioned into the 19th Hyderabad Regiment in mid-August 1942, with his appointment as 2nd Lieutenant being Gazetted on the 25th December that same year. Within a few weeks of taking up his commission with the 19th Hyderabad's, Tom volunteered for a secret mission and was posted to Jhansi to join the recently formed 77th Indian Infantry Brigade. He and several other young officers from Indian Regiments were allocated to the various Chindit columns just before Christmas, with Tom sent to bolster No. 7 Column under the command of Major Kenneth Gilkes of the King's Regiment.

During Operation Longcloth, Tom served as 7 Column's Intelligence Officer and travelled with Major Gilkes and his Head Quarters. It is said that he crossed the Chindwin riding his horse and wearing only his slouch hat and a belt of grenades. Generally speaking, 7 Column were used as protection for Brigadier Wingate and his own Brigade Head Quarters and only took part in one or two skirmishes with the Japanese in 1943. The Chindits had troubled the Japanese lines of communication in February and March 1943, demolishing various pieces of the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway. In late March, with the enemy now closing in, Wingate called an officers conference and with the added advice of India General Command, decided to call it a day and return back across the Chindwin.

On the 29th March, Brigade HQ, in the company of Columns 7 and 8 arrived at the Irrawaddy River, close to the village of Inywa. Wingate ordered Captain David Hastings to lead a bridgehead party across the river in the small Burmese country boats they had discovered hidden on the eastern shoreline. As the men prepared to cross some enemy activity was seen on the far bank. Wingate and his commanders felt that the Japanese posed little threat in their present numbers, and so pressed on with the crossing. Some of the lead boats did manage to get over, but others came under heavy mortar and machine gun fire and began to get into difficulties.

The crossing at Inywa was duly abandoned, the remaining columns and Wingate's HQ melted back into the jungle on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy. The three units agreed there and then to split up and make their own way back to Allied held territory individually. 7 Column retraced their steps east and set off toward the Chinese Yunnan borders. 8 Column under Major Scott eventually crossed the Irrawaddy further to the north two weeks later with the help of some more native boats, while Wingate held back in the jungles around Inywa for almost a week, hoping that the Japanese activity in the area would die down and their progress to India could resume unmolested.

Meanwhile, on the west bank of the Irrawaddy, opposite the village of Inywa, some thirty Chindit soldiers who had followed Captain Hastings over the river found themselves isolated and alone. One of these now desolate fellows was Lt. Thomas Arthur Stock.

Seen below is a gallery of images, consisting of four pages from the 13th King's War diary for 1943, recording the events leading up to and during the failed crossing of the Irrawaddy River at Inywa on March 29th. Also shown is a map of the area around Inywa and the various column dispersal routes thereafter. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

From the book Wingate's Lost Brigade:

Corporal Fred Morgan, a Bren gunner with 7 Column was another of the men who managed to get over the Irrawaddy on the 29th March, but was taken prisoner fairly quickly afterwards. Here is what he told the author:

As soon as we landed on the far bank a decision was made to move off in small groups as quickly as possible, since we did not want to attract too much attention to ourselves. After all, we had no idea as to the strength of the Jap patrol. The small group I was with was led by Lieutenant Stock. We had paused for a while, resting our heads on our packs, when all of a sudden a number of Japs came tearing up the hillside towards us. Needless to say we beat a hasty retreat up the hill. Somehow the Bren gun was left behind and I handed my rifle to someone and went back for it. I grabbed it, but found the magazine was empty and therefore useless.

On the way back I started to strip the gun and began throwing the pieces to the four winds. I finally caught up with Lieutenant Stock and found he was in possession of a revolver, but no ammunition. I think we had words with one another over that omission. We eventually lost contact with each other, but I met up with him again in Rangoon Jail. Now I was all by myself. I was alone, tired and frightened. I found myself climbing a very large hill and when I reached the top I started down the other side and began to cross a paddy field. No sooner had I got to the centre of the field when I heard shouting and what appeared to be animal noises. I stopped and turned around to see three Japanese running towards me. One of them had a sword and the other two had fixed bayonets and they started to prod me in the stomach. The Jap with the sword slapped my face and then knocked me to the ground.

To read more about this Chindit soldier, please click on the following link: Corporal Fred Morgan

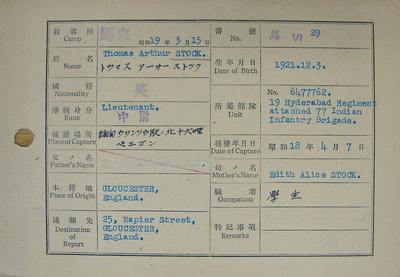

According to both his own notebook diary and his official POW index card, Tom was captured after being ambushed by a Japanese search party on the 7th April, near the village of Pegon, located some sixteen miles north of the rail station town of Wuntho. It is not known whether he was alone at this point, or with a small dispersal group. In his notebook he also records the 11th May as the date on which he reached Block 6 of Rangoon Jail.

In our email discussions, Tom's daughter, Rosamund recalled the following in relation to her father's capture:

Steve, I can't help wondering, although silly and insignificant compared to his and others tribulations at the time, whether Dad still had his glasses at this point, as he was very short-sighted. I also wonder where and when he was injured. He told me that after he was captured he was put on a stretcher next to a Japanese soldier who said to him in very broken English "it is not our lucky day." This soldier also taught Dad the Japanese for water and going to the toilet.

Back home in Gloucester, Tom's family knew nothing of his predicament. They had been informed that he was currently serving on a special operation and that although he could receive letters from them, he was unable to write back. On the 18th July 1943, Edith Stock received the letter that all mother's dreaded during WW2:

India Command (18th July 1943).

Dear Mrs. Stock,

It is with the deepest regret that I write to inform you that your son is missing. It is quite possible that he is a prisoner of war but we have no evidence that this is the case. When I last saw him he was his usual cheerful self and doing his utmost to help in any way he could. Our commanding officer has asked me to convey to you his most sincere sympathy in your great worry and to assure you that should we receive any further news we will at once communicate with you.

Six weeks later, the family received a second letter. This time from Captain John Swafer Pickering of the 13th King's Regiment and a fellow officer with No. 7 Column on Operation Longcloth:

Dear Mrs. Stock,

The powers that be have instructed me to look after your son's things, and on going through his box this morning I came across a couple of unsigned letters which I think you may like to have. I am also sending a list of his correspondence, which seems to give the names of people in whom he was interested. His actual kit is of no particular value, being mostly uniform of one sort or another. I have packed it up, and it will be sent off to the 2nd Echelon (Jhansi), who look after these things.

I should like to say how very sorry I was to hear that your son was missing. I know for a fact that he had joined up with other officers and men on the morning of the 29th March on the west banks of the Irrawaddy. I did not see him afterwards, as I had to rejoin the bulk of the column who were still on the eastern side of the river. It seems that Tom and one or two men got separated from their party a few days later, and I think it very likely that they may all be prisoners. I know that the Japanese hold quite a number of prisoners, and you must continue to hope that he is among them. I want you to know what a stout show Tom put up in Burma. As you know, he only joined us at the eleventh hour, and in consequence missed all the strenuous training. In spite of this disadvantage and it was a big handicap, as our activities were pretty searching both mentally and physically, he was settling down well, and becoming more useful every day.

Our column eventually landed in China, and we were flown home in an hour and three quarters! The Chinese and Americans couldn't do too much for us. Since then we have had a spell of anti-malaria treatment in hospital, a month's leave, and we are now shaking down again as a battalion. You may depend that I shall do what I can for your son's things, and if there is anything I can do for you please don't hesitate to ask.

Yours sincerely, J.S. Pickering.

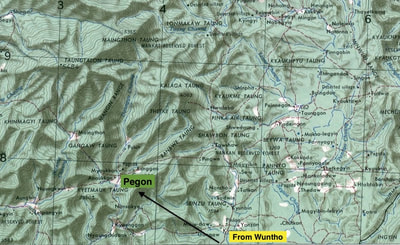

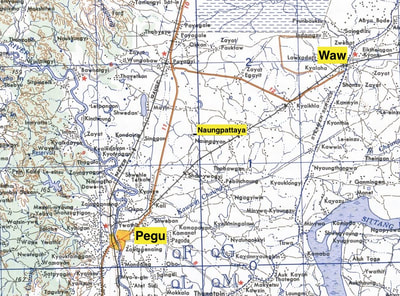

Seen below is another gallery of images in relation to this section of Tom's story, including a map showing the actual location of his capture near the village of Pegon. He had done fairly well to reach this far in the seven days since crossing the Irrawaddy and was attempting it seems, to retrace the route that 7 Column had taken when entering Burma eight weeks previously. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Corporal Fred Morgan, a Bren gunner with 7 Column was another of the men who managed to get over the Irrawaddy on the 29th March, but was taken prisoner fairly quickly afterwards. Here is what he told the author:

As soon as we landed on the far bank a decision was made to move off in small groups as quickly as possible, since we did not want to attract too much attention to ourselves. After all, we had no idea as to the strength of the Jap patrol. The small group I was with was led by Lieutenant Stock. We had paused for a while, resting our heads on our packs, when all of a sudden a number of Japs came tearing up the hillside towards us. Needless to say we beat a hasty retreat up the hill. Somehow the Bren gun was left behind and I handed my rifle to someone and went back for it. I grabbed it, but found the magazine was empty and therefore useless.

On the way back I started to strip the gun and began throwing the pieces to the four winds. I finally caught up with Lieutenant Stock and found he was in possession of a revolver, but no ammunition. I think we had words with one another over that omission. We eventually lost contact with each other, but I met up with him again in Rangoon Jail. Now I was all by myself. I was alone, tired and frightened. I found myself climbing a very large hill and when I reached the top I started down the other side and began to cross a paddy field. No sooner had I got to the centre of the field when I heard shouting and what appeared to be animal noises. I stopped and turned around to see three Japanese running towards me. One of them had a sword and the other two had fixed bayonets and they started to prod me in the stomach. The Jap with the sword slapped my face and then knocked me to the ground.

To read more about this Chindit soldier, please click on the following link: Corporal Fred Morgan

According to both his own notebook diary and his official POW index card, Tom was captured after being ambushed by a Japanese search party on the 7th April, near the village of Pegon, located some sixteen miles north of the rail station town of Wuntho. It is not known whether he was alone at this point, or with a small dispersal group. In his notebook he also records the 11th May as the date on which he reached Block 6 of Rangoon Jail.

In our email discussions, Tom's daughter, Rosamund recalled the following in relation to her father's capture:

Steve, I can't help wondering, although silly and insignificant compared to his and others tribulations at the time, whether Dad still had his glasses at this point, as he was very short-sighted. I also wonder where and when he was injured. He told me that after he was captured he was put on a stretcher next to a Japanese soldier who said to him in very broken English "it is not our lucky day." This soldier also taught Dad the Japanese for water and going to the toilet.

Back home in Gloucester, Tom's family knew nothing of his predicament. They had been informed that he was currently serving on a special operation and that although he could receive letters from them, he was unable to write back. On the 18th July 1943, Edith Stock received the letter that all mother's dreaded during WW2:

India Command (18th July 1943).

Dear Mrs. Stock,

It is with the deepest regret that I write to inform you that your son is missing. It is quite possible that he is a prisoner of war but we have no evidence that this is the case. When I last saw him he was his usual cheerful self and doing his utmost to help in any way he could. Our commanding officer has asked me to convey to you his most sincere sympathy in your great worry and to assure you that should we receive any further news we will at once communicate with you.

Six weeks later, the family received a second letter. This time from Captain John Swafer Pickering of the 13th King's Regiment and a fellow officer with No. 7 Column on Operation Longcloth:

Dear Mrs. Stock,

The powers that be have instructed me to look after your son's things, and on going through his box this morning I came across a couple of unsigned letters which I think you may like to have. I am also sending a list of his correspondence, which seems to give the names of people in whom he was interested. His actual kit is of no particular value, being mostly uniform of one sort or another. I have packed it up, and it will be sent off to the 2nd Echelon (Jhansi), who look after these things.

I should like to say how very sorry I was to hear that your son was missing. I know for a fact that he had joined up with other officers and men on the morning of the 29th March on the west banks of the Irrawaddy. I did not see him afterwards, as I had to rejoin the bulk of the column who were still on the eastern side of the river. It seems that Tom and one or two men got separated from their party a few days later, and I think it very likely that they may all be prisoners. I know that the Japanese hold quite a number of prisoners, and you must continue to hope that he is among them. I want you to know what a stout show Tom put up in Burma. As you know, he only joined us at the eleventh hour, and in consequence missed all the strenuous training. In spite of this disadvantage and it was a big handicap, as our activities were pretty searching both mentally and physically, he was settling down well, and becoming more useful every day.

Our column eventually landed in China, and we were flown home in an hour and three quarters! The Chinese and Americans couldn't do too much for us. Since then we have had a spell of anti-malaria treatment in hospital, a month's leave, and we are now shaking down again as a battalion. You may depend that I shall do what I can for your son's things, and if there is anything I can do for you please don't hesitate to ask.

Yours sincerely, J.S. Pickering.

Seen below is another gallery of images in relation to this section of Tom's story, including a map showing the actual location of his capture near the village of Pegon. He had done fairly well to reach this far in the seven days since crossing the Irrawaddy and was attempting it seems, to retrace the route that 7 Column had taken when entering Burma eight weeks previously. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Another subject of discussion between Rosamund and myself during our email communications, centred around the men present with Tom from the 29th March, up until his capture on the 7th April 1943. After searching through the 13th King's missing in action documents in my own research files, I found three men who were probably with Tom and Corporal Morgan after the crossing of the Irrawaddy River on the 29th March.

Morgan was the subject of a witness statement, given by a Sgt. A. Allan of the King's Regiment, which also mentioned three other men: Edgar John Fosh, William Howell and James Swithenby, who according to the statement all died in the jungle on the 2nd April just after crossing the Meza River and railway. Here is Sgt. Allan's statement:

Statement of evidence, dated 24th July 1943, in the case of:

3780681 Pte. E. Fosh

6028957 Pte. W. Howell

5628420 Cpl. F. Morgan

3780871 Pte. J. Swithenby

3185636 Sgt. A. Allan of the 13th King's states: I was the Sergeant in charge of Animal Transport in No. 7 Column during Brigadier Wingate's Burma Expedition. At the beginning of April, I was a member of a dispersal group led by Lt. Jelliss, making our way out of Burma towards the Chindwin River. On April 2nd 1943, at about 11.00 hours we were halted in a nullah about half a mile west of the Mesa River and a few miles east of the Katha-Mandalay Railway.

We were attacked by a party of Japanese and a skirmish ensued. Our party split up into smaller groups, then dispersed and continued the march out of Burma independently. The above-mentioned British Other Rank's did not attach themselves to any group and have not been heard of since. Corporal Morgan had a Bren Gun, but it is not known whether the others had retained their arms and ammunition when surprised by the Japanese. They had some rice and were reasonably fit. They were at least 14 days march from the Chindwin.

After his liberation in May 1945, Fred Morgan was asked for his help in regards to the fate of the men with him at the Irrawaddy and those who had subsequently become prisoners of war. He then wrote a letter to the Army Investigation Bureau in late 1945, listing some of the men with him on the western banks of the Irrawaddy on the 29th March 1943. Included on this list were Pte. Edward Kitchen and Pte. Alfred Strevens, both of whom were killed or wounded by enemy fire at the Irrawaddy. He also gave further information about William Howell.

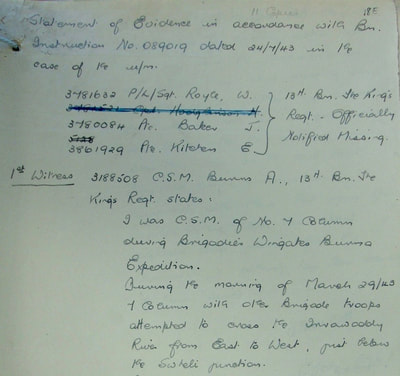

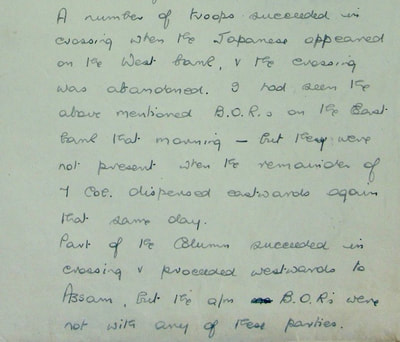

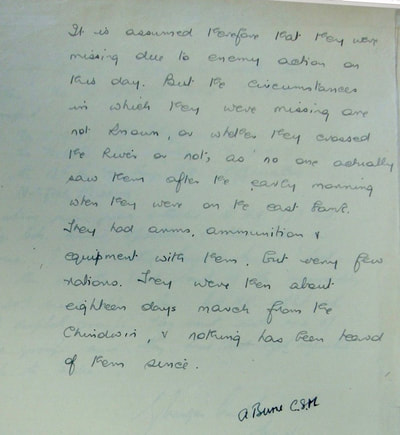

The information about Edward Kitchen led me to another witness statement given by a CSM 3188508 Andrew Burns, who described the crossing of the Irrawaddy and Pte. Kitchen's involvement; also included in Burns' statement were Sgt. William Royle and Pte. James Baker who were both killed during the ill-fated crossing. It could be that the above-mentioned soldiers all formed part of the group led by Tom Stock on the 29th March 1943 at the Irrawaddy River, or became part of his group during the confused period after landing on the west banks. We shall probably never really know for sure.

Here is what we do know about each man:

Pte. 3780681 Edgar John Fosh, was a soldier with 7 Column on Operation Longcloth and was presumed killed in action on the 2nd April 1943, whilst lost in the Meza Valley, a half-mile from the Meza River and close to the Mandalay-Myitkhina Railway. Edgar has no known grave and so is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial, located in the grounds of Taukkyan War Cemetery which is situated in the northern outskirts of the capital city.

Pte. 6023957 William Robert Thomas Howell was the son of Robert and Ethel Howell from Shoreditch in London. William was also a soldier with 7 Column on Operation Longcloth and was also presumed killed in action on the 2nd April 1943 at the Meza River ambush. He has no known grave and so is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial alongside his comrade Edgar Fosh.

Pte. 37800871 James Swithenby was the son of Nehemiah and Lily Swithenby and the husband of Edith Hannah Swithenby from Leigh in Lancashire. James has exactly the same details recorded to his name as both Edgar Fosh and William Howell, apart from the fact that due to the alphabetical nature of his surname, he is remembered upon Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan.

Pte. 3861929 Edward Kitchen was the son of Francis and Elizabeth Kitchen and husband of Mary Kitchen. Edward was a member of 7 Column and was lost when his boat was washed downstream during the ill-fated crossing of the Irrawaddy River on the 29th March 1943. Edward's boat contained Captain David Hastings along with Sergeant William Royle, Corporal Harold Hodgkinson and Ptes. James Baker. The boat was struggling to make the western bank and was continuously under heavy fire from the Japanese positions. He is also remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial.

Pte. 5628431 Alfred John Strevens was a Londoner from Kentish Town and a member of 7 Column in 1943. This former 12th Devon crossed the Irrawaddy on the 29th March, but was wounded at the river by an enemy mortar bomb and died later. Alfred is remembered upon Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial.

Shown below is another gallery of images, including the witness statement given by CSM Andrew Burns on the 24th July 1943. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. To read more about Sgt. William Royle and Pte. James Baker, please click on the following link and scroll down to the relevant story: Sgt. William Royle

Morgan was the subject of a witness statement, given by a Sgt. A. Allan of the King's Regiment, which also mentioned three other men: Edgar John Fosh, William Howell and James Swithenby, who according to the statement all died in the jungle on the 2nd April just after crossing the Meza River and railway. Here is Sgt. Allan's statement:

Statement of evidence, dated 24th July 1943, in the case of:

3780681 Pte. E. Fosh

6028957 Pte. W. Howell

5628420 Cpl. F. Morgan

3780871 Pte. J. Swithenby

3185636 Sgt. A. Allan of the 13th King's states: I was the Sergeant in charge of Animal Transport in No. 7 Column during Brigadier Wingate's Burma Expedition. At the beginning of April, I was a member of a dispersal group led by Lt. Jelliss, making our way out of Burma towards the Chindwin River. On April 2nd 1943, at about 11.00 hours we were halted in a nullah about half a mile west of the Mesa River and a few miles east of the Katha-Mandalay Railway.

We were attacked by a party of Japanese and a skirmish ensued. Our party split up into smaller groups, then dispersed and continued the march out of Burma independently. The above-mentioned British Other Rank's did not attach themselves to any group and have not been heard of since. Corporal Morgan had a Bren Gun, but it is not known whether the others had retained their arms and ammunition when surprised by the Japanese. They had some rice and were reasonably fit. They were at least 14 days march from the Chindwin.

After his liberation in May 1945, Fred Morgan was asked for his help in regards to the fate of the men with him at the Irrawaddy and those who had subsequently become prisoners of war. He then wrote a letter to the Army Investigation Bureau in late 1945, listing some of the men with him on the western banks of the Irrawaddy on the 29th March 1943. Included on this list were Pte. Edward Kitchen and Pte. Alfred Strevens, both of whom were killed or wounded by enemy fire at the Irrawaddy. He also gave further information about William Howell.

The information about Edward Kitchen led me to another witness statement given by a CSM 3188508 Andrew Burns, who described the crossing of the Irrawaddy and Pte. Kitchen's involvement; also included in Burns' statement were Sgt. William Royle and Pte. James Baker who were both killed during the ill-fated crossing. It could be that the above-mentioned soldiers all formed part of the group led by Tom Stock on the 29th March 1943 at the Irrawaddy River, or became part of his group during the confused period after landing on the west banks. We shall probably never really know for sure.

Here is what we do know about each man:

Pte. 3780681 Edgar John Fosh, was a soldier with 7 Column on Operation Longcloth and was presumed killed in action on the 2nd April 1943, whilst lost in the Meza Valley, a half-mile from the Meza River and close to the Mandalay-Myitkhina Railway. Edgar has no known grave and so is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial, located in the grounds of Taukkyan War Cemetery which is situated in the northern outskirts of the capital city.

Pte. 6023957 William Robert Thomas Howell was the son of Robert and Ethel Howell from Shoreditch in London. William was also a soldier with 7 Column on Operation Longcloth and was also presumed killed in action on the 2nd April 1943 at the Meza River ambush. He has no known grave and so is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial alongside his comrade Edgar Fosh.

Pte. 37800871 James Swithenby was the son of Nehemiah and Lily Swithenby and the husband of Edith Hannah Swithenby from Leigh in Lancashire. James has exactly the same details recorded to his name as both Edgar Fosh and William Howell, apart from the fact that due to the alphabetical nature of his surname, he is remembered upon Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan.

Pte. 3861929 Edward Kitchen was the son of Francis and Elizabeth Kitchen and husband of Mary Kitchen. Edward was a member of 7 Column and was lost when his boat was washed downstream during the ill-fated crossing of the Irrawaddy River on the 29th March 1943. Edward's boat contained Captain David Hastings along with Sergeant William Royle, Corporal Harold Hodgkinson and Ptes. James Baker. The boat was struggling to make the western bank and was continuously under heavy fire from the Japanese positions. He is also remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial.

Pte. 5628431 Alfred John Strevens was a Londoner from Kentish Town and a member of 7 Column in 1943. This former 12th Devon crossed the Irrawaddy on the 29th March, but was wounded at the river by an enemy mortar bomb and died later. Alfred is remembered upon Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial.

Shown below is another gallery of images, including the witness statement given by CSM Andrew Burns on the 24th July 1943. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. To read more about Sgt. William Royle and Pte. James Baker, please click on the following link and scroll down to the relevant story: Sgt. William Royle

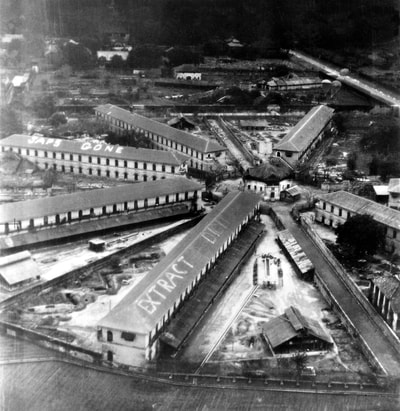

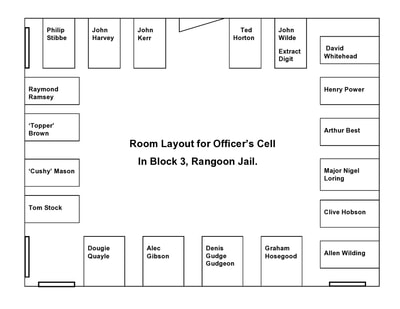

Life as a prisoner of war in Rangoon Jail

As mentioned earlier, an entry in Tom's notebook states that he entered Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on the 11th May 1943. Both Lt. Philip Stibbe and Corporal Fred Morgan arrived at the jail around much the same time, having previously been held at a concentration camp located in the hill station town of Maymyo. The fact that both men recall in their writings meeting up with Tom again at Rangoon, suggests that he was not held at Maymyo and had been incarcerated elsewhere before journeying to Rangoon.

Lt. Stibbe and Tom had not seen eye to eye on their first meeting as Chindit soldiers. Tom had been placed in charge of a large ration dump on the road from Tamu to the Chindwin River and had been over-protective in the amount of supplies he was willing to hand out when Stibbe came to collect for his men. The same thing occurred at the first supply drop inside Burma at a place called Tonmakeng on the 24th February 1943.

In his book, Return via Rangoon, Stibbe recalled:

At Rangoon I met Stock, the officer with whom I had differences of opinion at Tonmakeng and earlier. This time we discovered we had much in common and I shall always be thankful that I spent my years of captivity with a man of such amazingly comprehensive knowledge. Strangely enough, although we first met in Burma, we had both been at Oxford at the same time, he at Magdelen under C.S. Lewis and I at Merton under Edmund Blunden. He was captured between the Irrawaddy and the Chindwin about a week after I was captured. To my amusement he told me that one of the first questions to be put to him by his captors was, "Do you know an officer called Stibbe?" When he hesitated, they added by way of description, "He has a very large nose." This made him laugh so much that he could no longer pretend not to know me.

The close friendship forged between Tom and Philip Stibbe at Rangoon would last for many years to come. Many of the captured Chindit officers shared a cell in Rangoon Jail, with up to 30 men in each room. Officers tended to be placed up on the first floor of each cell block and slept on the bare boards, whilst Other Ranks were accommodated below, where they slept on the cold and extremely hard concrete floor. Tom was given the POW number 29 at Rangoon. This basically meant that he was the 29th officer to be held at the jail since it was first used by the Japanese in March 1942.

As already mentioned by Philip Stibbe, Tom became well known in Rangoon for his knowledge and intellect. He gave many lectures on various subjects as a way of passing the time during his two years in Japanese hands. Tom, affectionately known as Stocko at Rangoon, was admired for knowing the Christian funeral service off by heart and I wonder how many times he was called upon to recite these words, as more and more of his Chindit comrades perished within the jail. To read more about life as a prisoner of war inside Rangoon Jail, please click on the following link: Chindit POW's

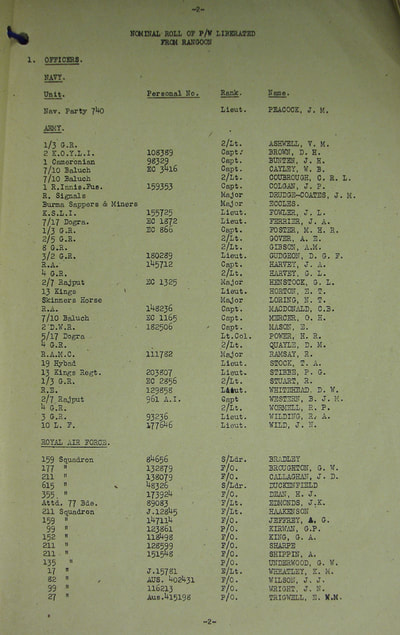

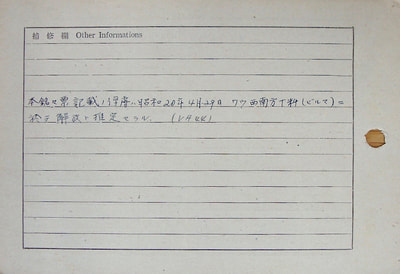

On the reverse side of Tom's POW index card (file series WO345 at the National Archives), there is a single sentence written in Japanese Kanji characters. Translated, it roughly reads: The Prisoner of War recorded on this document was estimated to have been released on Showa 20, (20th year of Hirohito's reign, equates to 1945) April 29, 100 meters southwest of Waw village (Burma).

On the 24th April 1945, the Japanese began evacuating their forces from Rangoon in the face of the rapidly advancing British 14th Army. The Commandant of the jail decided to take with him around 400 of the POW's, to act as a human shield should his party encounter Allied forces along the way. Their aim was to cross over into Thailand, which was still held by the Japanese and then use the prisoners as slave labour for any project that came to mind.

In his notebook, Tom refers to this period and describes the five days from the 24th until the 29th April. He remarks how he, along with several other of the prisoners marched along in their bare feet. He also refers to the almost continuous worry of being attacked by Allied aircraft which were now patrolling the skies above Rangoon and surrounding areas. On the 28th April the party reached a river bridge on the outskirts of Pegu and were barely over before some Japanese engineers blew it up. That evening the POW's settled down at a village called Naungpattaya. The following morning, just before dawn, the Japanese Commandant announced that he and his men were moving off and that he was granting all the prisoners their freedom. The almost unbelieving POW's, excited by this news, attempted to make contact with Allied aircraft by placing a Union Jack and signal on the ground, made up of clothing, sheets and other garments.

The 400 plus men from Rangoon Jail were liberated shortly afterwards by a section of troops from the 1st West Yorkshire Regiment. They were given new uniforms, boots and had a grand feed of hot stew, bread, cheese, peaches and of course lashings of tea with sugar and milk. The next day Tom and many of his comrades were flown back to India aboard Dakota aircraft and straight into hospital. After visiting several other medical establishments over the coming days and weeks, including No. 134 Indian General Hospital at Trimulgherry, on the 4th July 1945, Tom formerly rejoined the 19th Hyderabad Regiment at its base in the Indian city of Agra.

During his time as a prisoner of war, Tom had received no mail from his family back home in England. On the 12th May 1945, he was able to send a letter home to his mother informing her that he was once again a free man and recounting all that had befallen him since February 1943. He then asked his mother to tell him all the news from Gloucestershire, as he was eager to catch up on the local scene and the family and friends he loved. In a subsequent letter dated 3rd August, he informed his mother Edith that he expected to arrive home on leave within a couple of weeks. Within three days of writing this letter, the two atom bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki effectively ending the war.

Seen below is another gallery of images in relation to this section of the story, including Tom Stock's POW index card. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

As mentioned earlier, an entry in Tom's notebook states that he entered Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on the 11th May 1943. Both Lt. Philip Stibbe and Corporal Fred Morgan arrived at the jail around much the same time, having previously been held at a concentration camp located in the hill station town of Maymyo. The fact that both men recall in their writings meeting up with Tom again at Rangoon, suggests that he was not held at Maymyo and had been incarcerated elsewhere before journeying to Rangoon.

Lt. Stibbe and Tom had not seen eye to eye on their first meeting as Chindit soldiers. Tom had been placed in charge of a large ration dump on the road from Tamu to the Chindwin River and had been over-protective in the amount of supplies he was willing to hand out when Stibbe came to collect for his men. The same thing occurred at the first supply drop inside Burma at a place called Tonmakeng on the 24th February 1943.

In his book, Return via Rangoon, Stibbe recalled:

At Rangoon I met Stock, the officer with whom I had differences of opinion at Tonmakeng and earlier. This time we discovered we had much in common and I shall always be thankful that I spent my years of captivity with a man of such amazingly comprehensive knowledge. Strangely enough, although we first met in Burma, we had both been at Oxford at the same time, he at Magdelen under C.S. Lewis and I at Merton under Edmund Blunden. He was captured between the Irrawaddy and the Chindwin about a week after I was captured. To my amusement he told me that one of the first questions to be put to him by his captors was, "Do you know an officer called Stibbe?" When he hesitated, they added by way of description, "He has a very large nose." This made him laugh so much that he could no longer pretend not to know me.

The close friendship forged between Tom and Philip Stibbe at Rangoon would last for many years to come. Many of the captured Chindit officers shared a cell in Rangoon Jail, with up to 30 men in each room. Officers tended to be placed up on the first floor of each cell block and slept on the bare boards, whilst Other Ranks were accommodated below, where they slept on the cold and extremely hard concrete floor. Tom was given the POW number 29 at Rangoon. This basically meant that he was the 29th officer to be held at the jail since it was first used by the Japanese in March 1942.

As already mentioned by Philip Stibbe, Tom became well known in Rangoon for his knowledge and intellect. He gave many lectures on various subjects as a way of passing the time during his two years in Japanese hands. Tom, affectionately known as Stocko at Rangoon, was admired for knowing the Christian funeral service off by heart and I wonder how many times he was called upon to recite these words, as more and more of his Chindit comrades perished within the jail. To read more about life as a prisoner of war inside Rangoon Jail, please click on the following link: Chindit POW's

On the reverse side of Tom's POW index card (file series WO345 at the National Archives), there is a single sentence written in Japanese Kanji characters. Translated, it roughly reads: The Prisoner of War recorded on this document was estimated to have been released on Showa 20, (20th year of Hirohito's reign, equates to 1945) April 29, 100 meters southwest of Waw village (Burma).

On the 24th April 1945, the Japanese began evacuating their forces from Rangoon in the face of the rapidly advancing British 14th Army. The Commandant of the jail decided to take with him around 400 of the POW's, to act as a human shield should his party encounter Allied forces along the way. Their aim was to cross over into Thailand, which was still held by the Japanese and then use the prisoners as slave labour for any project that came to mind.

In his notebook, Tom refers to this period and describes the five days from the 24th until the 29th April. He remarks how he, along with several other of the prisoners marched along in their bare feet. He also refers to the almost continuous worry of being attacked by Allied aircraft which were now patrolling the skies above Rangoon and surrounding areas. On the 28th April the party reached a river bridge on the outskirts of Pegu and were barely over before some Japanese engineers blew it up. That evening the POW's settled down at a village called Naungpattaya. The following morning, just before dawn, the Japanese Commandant announced that he and his men were moving off and that he was granting all the prisoners their freedom. The almost unbelieving POW's, excited by this news, attempted to make contact with Allied aircraft by placing a Union Jack and signal on the ground, made up of clothing, sheets and other garments.

The 400 plus men from Rangoon Jail were liberated shortly afterwards by a section of troops from the 1st West Yorkshire Regiment. They were given new uniforms, boots and had a grand feed of hot stew, bread, cheese, peaches and of course lashings of tea with sugar and milk. The next day Tom and many of his comrades were flown back to India aboard Dakota aircraft and straight into hospital. After visiting several other medical establishments over the coming days and weeks, including No. 134 Indian General Hospital at Trimulgherry, on the 4th July 1945, Tom formerly rejoined the 19th Hyderabad Regiment at its base in the Indian city of Agra.

During his time as a prisoner of war, Tom had received no mail from his family back home in England. On the 12th May 1945, he was able to send a letter home to his mother informing her that he was once again a free man and recounting all that had befallen him since February 1943. He then asked his mother to tell him all the news from Gloucestershire, as he was eager to catch up on the local scene and the family and friends he loved. In a subsequent letter dated 3rd August, he informed his mother Edith that he expected to arrive home on leave within a couple of weeks. Within three days of writing this letter, the two atom bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki effectively ending the war.

Seen below is another gallery of images in relation to this section of the story, including Tom Stock's POW index card. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

In late August 1945, Tom arrived home in Gloucester. During his extended leave period he was asked to speak at a meeting arranged by the International Red Cross, the aim of which was to reassure and support families who still had loved-ones held as prisoners of war in the Far East.

From the Gloucester Citizen newspaper, dated Thursday September 13th 1945:

POW's Talk to Relatives

A special meeting arranged by Mrs. Nicholls of the Red Cross and Eric Fowler of the Prisoner of War Relatives Association, was held at the Winston Hall, Gloucester, for relatives of POW's still in the Far East. Chairman Mrs. Fowler, welcomed all present and particularly T. A. Stock, one of Wingate's Chindits captured in 1943 and lately repatriated from Burma and the Reverend Owen Griffiths, interned for nearly four years and repatriated from Manilla in April.

The Chairman congratulated Mrs. Leach of 21 Herbert Street, who had received a wire from her son from Melbourne. He had been a POW for over four years. Mrs. Nicholls spoke of the difficulties the Red Cross had experienced in regard to prisoners in the Far East. Lt. Stock told the relatives that it was three months since he left Delhi by air and it would be a comfort to relatives to know how splendidly India had prepared for the reception of over 150,000 prisoners. He explained that there were four very large and fully equipped hospitals waiting and the medical service was excellent. He asked relatives not to despair if they had no news, as many men had gone into hiding. His own camp at Rangoon had not been one of worst ones, but the food was certainly very poor and they received no letters or mail.

The Reverend Griffiths gave an account of his experiences in a civilian internment camp, where the internees had undergone very great hardships. He spoke of the endurance and high morale of his fellow internees and paid particular tribute to the splendid courage of some men from the Merchant Service who were also in his camp. After a vote of thanks was expressed to all at the meeting, tea was served.

From the Gloucester Citizen newspaper, dated Thursday September 13th 1945:

POW's Talk to Relatives

A special meeting arranged by Mrs. Nicholls of the Red Cross and Eric Fowler of the Prisoner of War Relatives Association, was held at the Winston Hall, Gloucester, for relatives of POW's still in the Far East. Chairman Mrs. Fowler, welcomed all present and particularly T. A. Stock, one of Wingate's Chindits captured in 1943 and lately repatriated from Burma and the Reverend Owen Griffiths, interned for nearly four years and repatriated from Manilla in April.

The Chairman congratulated Mrs. Leach of 21 Herbert Street, who had received a wire from her son from Melbourne. He had been a POW for over four years. Mrs. Nicholls spoke of the difficulties the Red Cross had experienced in regard to prisoners in the Far East. Lt. Stock told the relatives that it was three months since he left Delhi by air and it would be a comfort to relatives to know how splendidly India had prepared for the reception of over 150,000 prisoners. He explained that there were four very large and fully equipped hospitals waiting and the medical service was excellent. He asked relatives not to despair if they had no news, as many men had gone into hiding. His own camp at Rangoon had not been one of worst ones, but the food was certainly very poor and they received no letters or mail.

The Reverend Griffiths gave an account of his experiences in a civilian internment camp, where the internees had undergone very great hardships. He spoke of the endurance and high morale of his fellow internees and paid particular tribute to the splendid courage of some men from the Merchant Service who were also in his camp. After a vote of thanks was expressed to all at the meeting, tea was served.

Tom's daughter, Rosamund wrote in her father's eulogy:

Captivity and the war had a profound effect on Dad and took a great deal from him including a good part of his youth. Still very unwell, he returned directly to Oxford after the war, but found it a very different place. Whilst managing to complete his degree, he felt he had let himself down on this front. The post-war trauma and disillusionment led to a temporary withdrawal from his friends and a retreat from Oxford which might otherwise have provided a very natural home for him.

However Tom’s gift for exploring and sharing knowledge took him first to do post-graduate studies in phonetics at the University of London and would soon take him much further afield. He taught English at Legon University in Ghana throughout the 1950’s and was responsible for buying books for the new library there, a role he relished. He thoroughly enjoyed his time in Africa, equipping people with his love of learning, so much so, that some of his students are now professors teaching in his stead.

Tom married my mother Judy, at St. Margaret Pattens Church in East London on the 22nd August 1964 and had three children, myself and my two sisters. We all grew up in the small village of Wendens Ambo in Cambridgeshire where Tom enjoyed village life immensely, whilst continually adding to his ever-impressive library of books. In 1977, he underwent major heart surgery at Papworth Hospital under Surgeon Sir Terence English. This surgery was successful and we were all blessed to have Dad around for another twenty-six years.

Tom retired in 1987 and had an extremely enjoyable retirement, particularly after the move to Ledbury, Herefordshire in 1999. Tom and Judy both spoke very warmly of their life there with their new friends and the many activities. He saw a great deal of his grandchildren and was always fascinated watching their personalities emerge. He could frequently be found reading stories to them, something we all remember clearly and with great affection from our own childhood.

Rosamund also told me that:

Tom was a member of the Burma Star Association, but rarely spoke about his wartime experiences with his family, although he did open up a little more after the 40th Anniversary of VJ Day in 1985. Throughout his life after the war he bore no ill-will towards the Japanese and continued to study their language for many years.

Tom Stock passed away in November 2003.

Captivity and the war had a profound effect on Dad and took a great deal from him including a good part of his youth. Still very unwell, he returned directly to Oxford after the war, but found it a very different place. Whilst managing to complete his degree, he felt he had let himself down on this front. The post-war trauma and disillusionment led to a temporary withdrawal from his friends and a retreat from Oxford which might otherwise have provided a very natural home for him.

However Tom’s gift for exploring and sharing knowledge took him first to do post-graduate studies in phonetics at the University of London and would soon take him much further afield. He taught English at Legon University in Ghana throughout the 1950’s and was responsible for buying books for the new library there, a role he relished. He thoroughly enjoyed his time in Africa, equipping people with his love of learning, so much so, that some of his students are now professors teaching in his stead.

Tom married my mother Judy, at St. Margaret Pattens Church in East London on the 22nd August 1964 and had three children, myself and my two sisters. We all grew up in the small village of Wendens Ambo in Cambridgeshire where Tom enjoyed village life immensely, whilst continually adding to his ever-impressive library of books. In 1977, he underwent major heart surgery at Papworth Hospital under Surgeon Sir Terence English. This surgery was successful and we were all blessed to have Dad around for another twenty-six years.

Tom retired in 1987 and had an extremely enjoyable retirement, particularly after the move to Ledbury, Herefordshire in 1999. Tom and Judy both spoke very warmly of their life there with their new friends and the many activities. He saw a great deal of his grandchildren and was always fascinated watching their personalities emerge. He could frequently be found reading stories to them, something we all remember clearly and with great affection from our own childhood.

Rosamund also told me that:

Tom was a member of the Burma Star Association, but rarely spoke about his wartime experiences with his family, although he did open up a little more after the 40th Anniversary of VJ Day in 1985. Throughout his life after the war he bore no ill-will towards the Japanese and continued to study their language for many years.

Tom Stock passed away in November 2003.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, May 2018.